User login

Western Pygmy Rattlesnake Envenomation and Bite Management

There are 375 species of poisonous snakes, with approximately 20,000 deaths worldwide each year due to snakebites, mostly in Asia and Africa.1 The death rate in the United States is 14 to 20 cases per year. In the United States, a variety of rattlesnakes are poisonous. There are 2 genera of rattlesnakes: Sistrurus (3 species) and Crotalus (23 species). The pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Sistrurus miliarius species that is divided into 3 subspecies: the Carolina pigmy rattlesnake (S miliarius miliarius), the western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri), and the dusky pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius barbouri).2

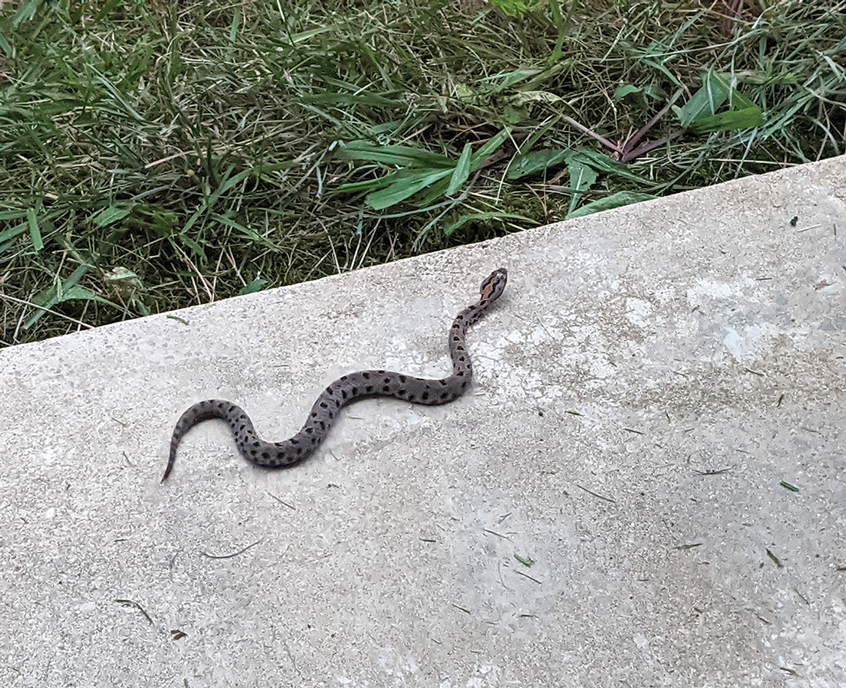

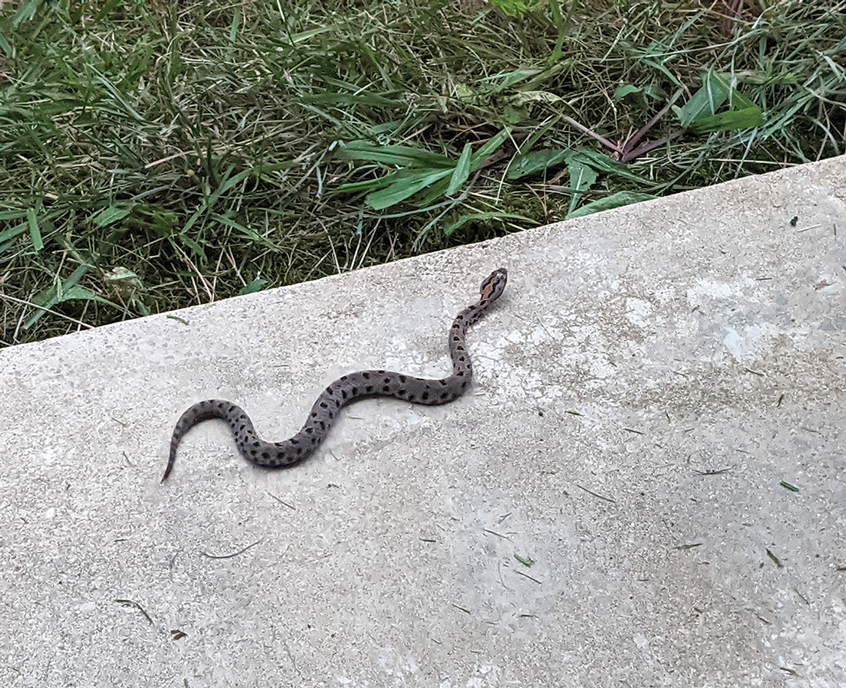

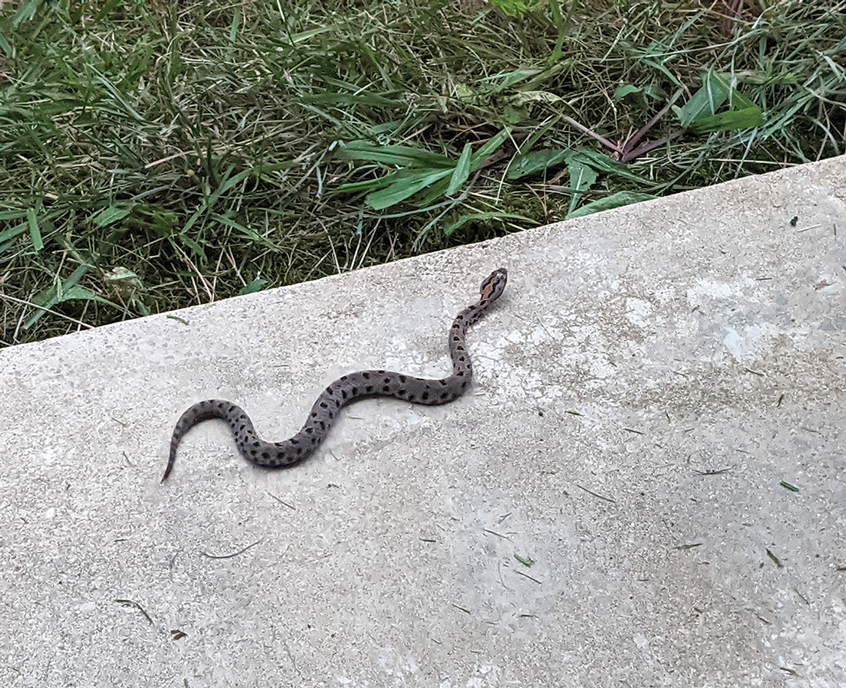

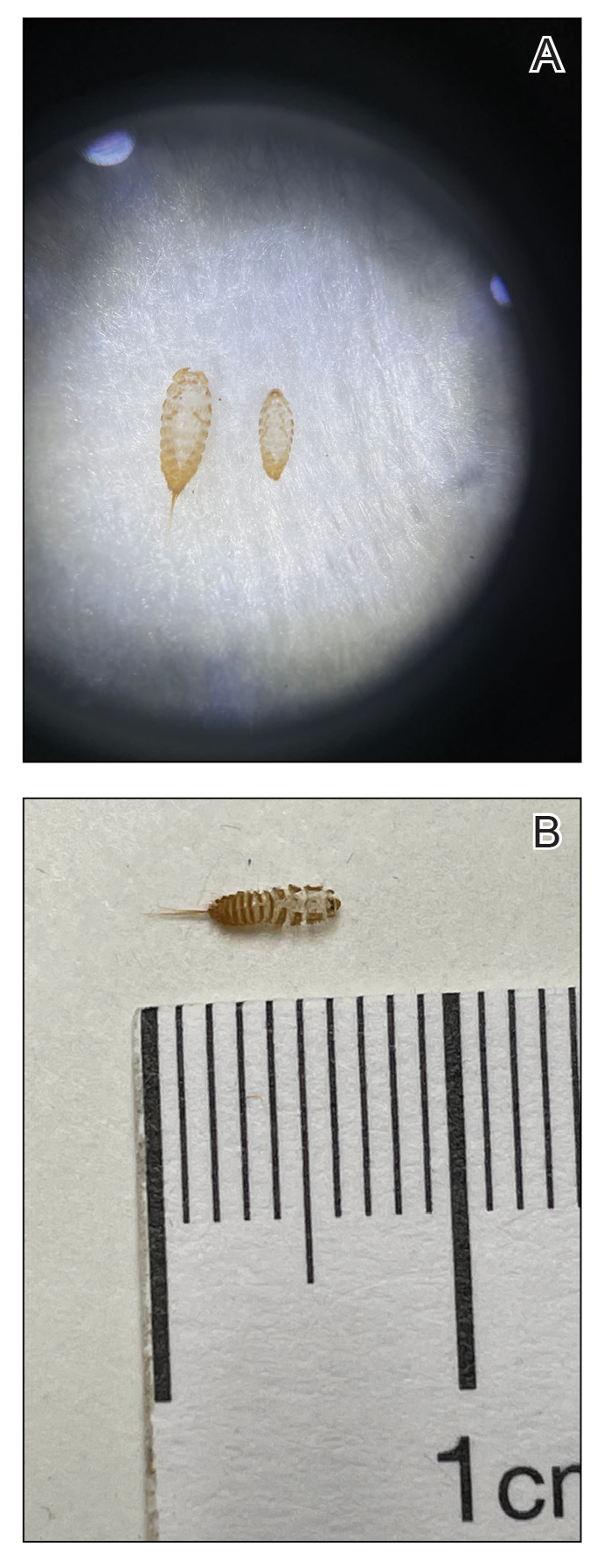

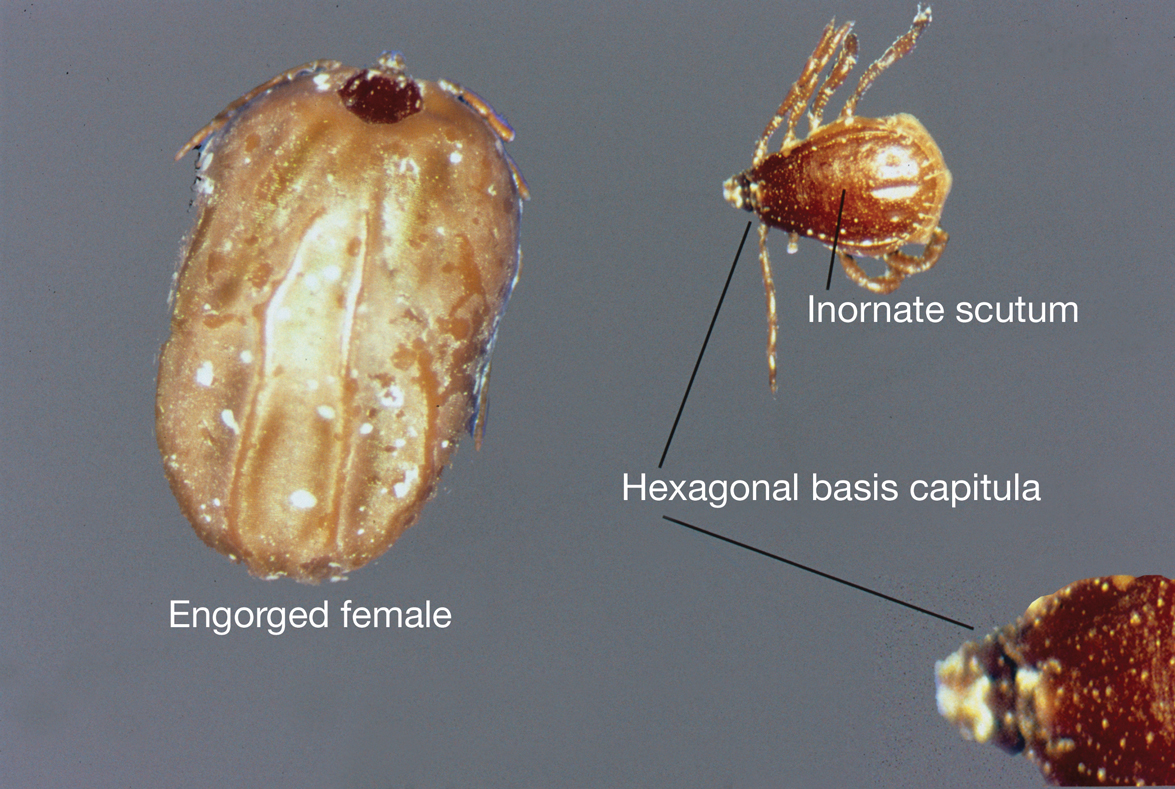

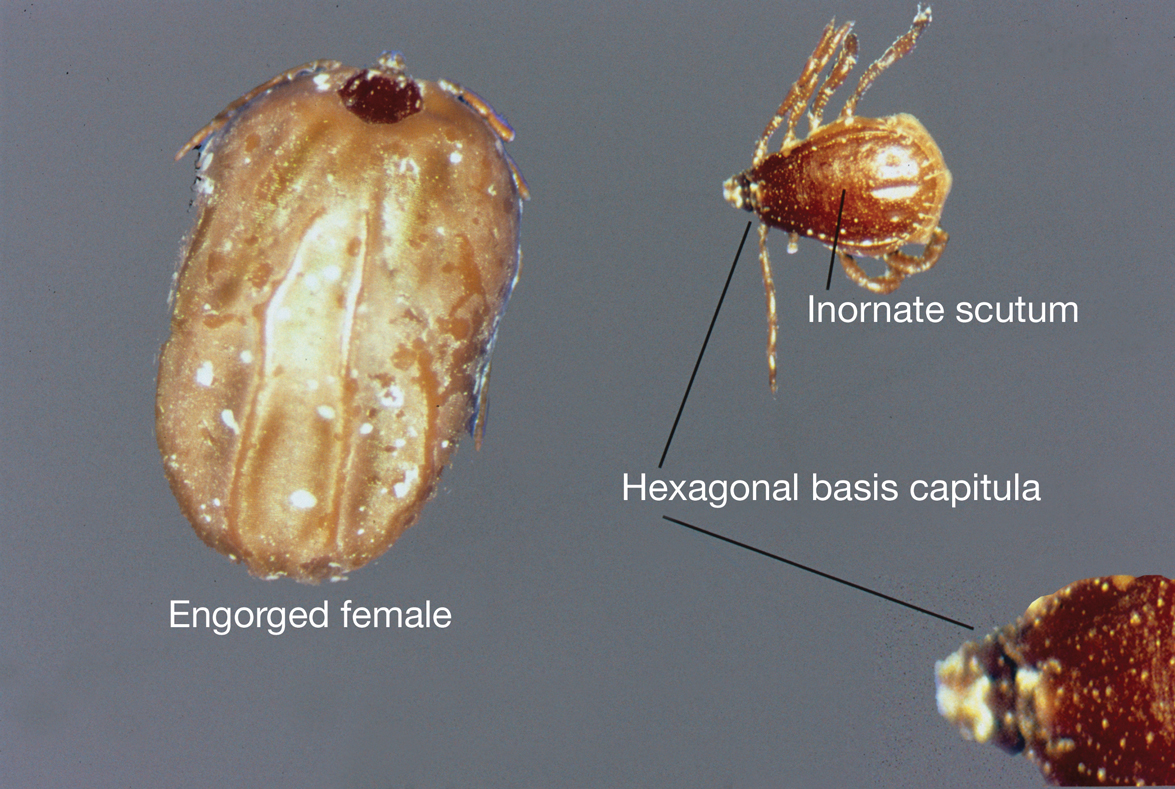

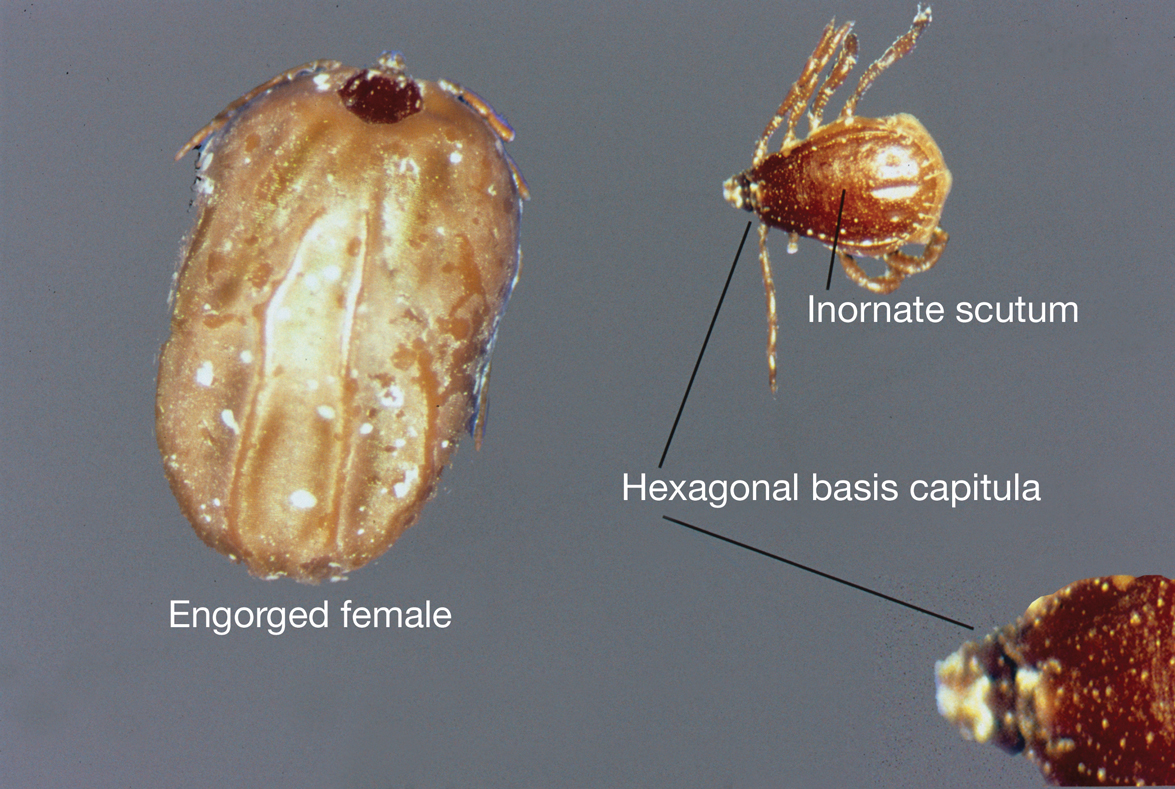

The western pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Crotalidae family. The rattlesnakes in this family also are known as pit vipers. All pit vipers have common characteristics for identification: triangular head, fangs, elliptical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit between the eyes. The western pygmy rattlesnake is found in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Tennessee.1 It is small bodied (15–20 inches)3 and grayish-brown, with a brown dorsal stripe with black blotches on its back. It is found in glades, second-growth forests near rock ledges, and areas where powerlines cut through dense forest.3 Its venom is hemorrhagic, causing tissue damage, but does not contain neurotoxins.4 Bites from the western pygmy rattlesnake often do not lead to death, but the venom, which contains numerous proteins and enzymes, does cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration at the site of envenomation and possible loss of digit.5,6

We present a case of a man who was bitten on the right third digit by a western pygmy rattlesnake. We describe the clinical course and treatment.

Case Report

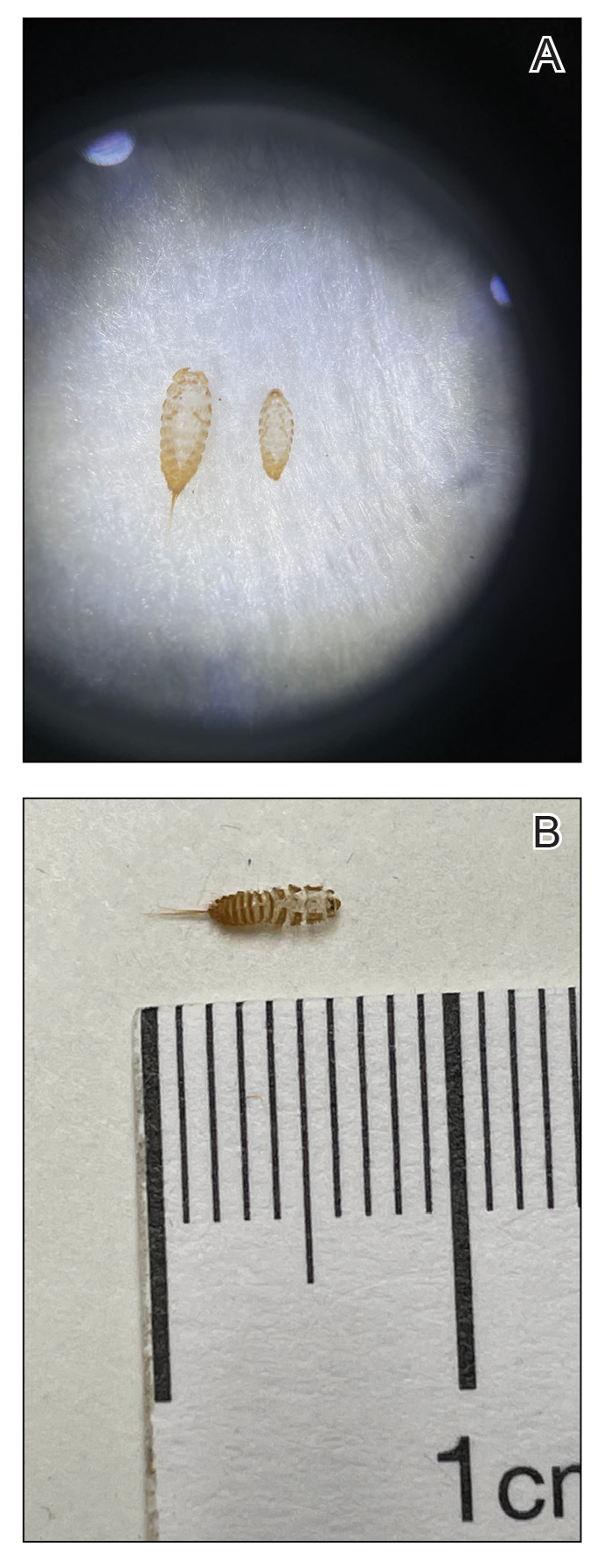

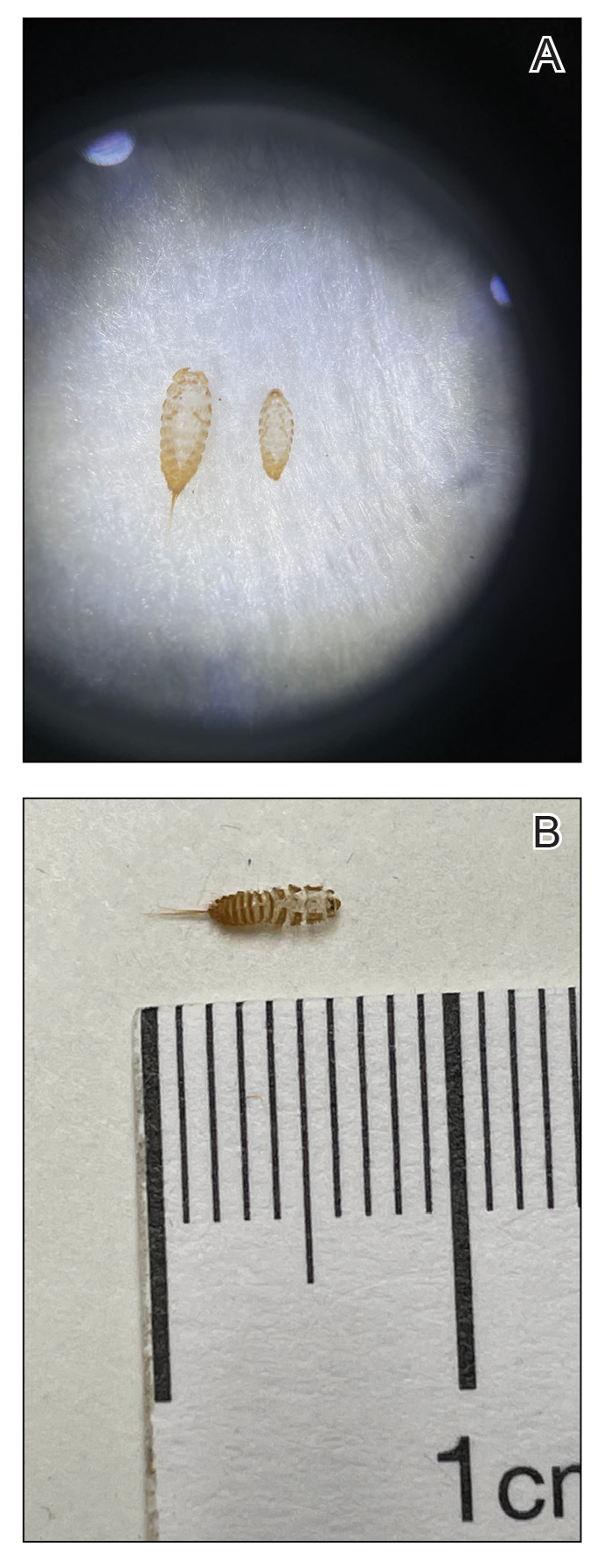

A 56-year-old right-handed man presented to the emergency department with a rapidly swelling, painful hand following a snakebite to the dorsal aspect of the right third digit (Figure 1). He was able to capture a photograph of the snake at the time of injury, which helped identify it as a western pygmy rattlesnake (Figure 2). He also photographed the hand immediately after the bite occurred (Figure 3). Vitals on presentation included an elevated blood pressure of 161/100 mm Hg; no fever (temperature, 36.4 °C); and normal pulse oximetry of 98%, pulse of 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

After the snakebite, the patient’s family called the Missouri Poison Center immediately. The family identified the snake species and shared this information with the poison center. Poison control recommended calling the nearest hospitals to determine if antivenom was available and make notification of arrival.

The patient’s tetanus toxoid immunization was updated immediately upon arrival. The hand was marked to monitor swelling. Initial laboratory test results revealed the following values: sodium, 133 mmol/L (reference range, 136–145 mmol/L); potassium, 3.4 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L); lactic acid, 2.4 mmol/L (0.5–2.2 mmol/L); creatine kinase, 425 U/L (55–170 U/L); platelet count, 68/µL (150,000–450,000/µL); fibrinogen, 169 mg/dL (185–410 mg/dL); and glucose, 121 mg/dL (74–106 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood cell count and metabolic panel was unremarkable. Radiographs of the hand did not show any fractures, dislocations, or foreign bodies. Missouri Poison Center was consulted. Given the patient’s severe pain, edema beyond 40 cm, and developing ecchymosis on the inner arm, the bite was graded as a 3 on the traditional snakebite severity scale. Poison control recommended 4 to 6 vials of antivenom over 60 minutes. Six vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom were given.

The patient’s complete blood cell count remained unremarkable throughout his admission. His metabolic panel returned to normal at 6 hours postadmission: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L. His lactate and creatinine kinase were not rechecked. His fibrinogen was trending upward. Serial laboratory test results revealed fibrinogen levels of 153, 158, 161, 159, 173, and 216 mg/dL at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours, respectively. Other laboratory test results including prothrombin time (11.0 s) and international normalized ratio (0.98) remained within reference range (11–13 s and 0.80–1.39, respectively) during serial monitoring.

The patient was hospitalized for 40 hours while waiting for his fibrinogen level to normalize. The local skin necrosis worsened acutely in this 40-hour window (Figure 4). Intravenous antibiotics were not administered during the hospital stay. Before discharge, the patient was evaluated by the surgery service, who did not recommend debridement.

Following discharge, the patient consulted a wound care expert. The area of necrosis was unroofed and debrided in the outpatient setting (Figure 5). The patient was started on oral cefalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and instructed to perform twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. A hand surgeon was consulted for consideration of a reverse cross-finger flap, which was not recommended. Twice-daily dressing changes for the wound—consisting of application of silver sulfadiazine cream 1% directly to the wound followed by gauze, self-adhesive soft-rolled gauze, and elastic bandages—were performed for 2 weeks.

After 2 weeks, the wound was left open to the air and cleaned with soap and water as needed. At 6 weeks, the wound was completely healed via secondary intention, except for some minor remaining ulceration at the location of the fang entry point (Figure 6). The patient had no loss of finger function or sensation.

Surgical Management of Snakebites

The surgeon’s role in managing snakebites is controversial. Snakebites were once perceived as a surgical emergency due to symptoms mimicking compartment syndrome; however, snakebites rarely cause a true compartment syndrome.7 Prophylactic bite excision and fasciotomies are not recommended. Incision and suction of the fang marks may be beneficial if performed within 15 to 30 minutes from the time of the bite.8 With access to a surgeon in this short time period being nearly impossible, incision and suctioning of fang marks generally is not recommended.9 Retained snake fangs are a possibility, and the infection could spread to a nearby joint, causing septic arthritis,10 which would be an indication for surgical intervention. Bites to the finger often cause major swelling, and the benefits of dermotomy are documented.11 Generally, early administration of antivenom will decrease local tissue reaction and prevent additional tissue loss.12 In our patient, the decision to perform dermotomy was made when the area of necrosis had declared itself and the skin reached its elastic limit. Bozkurt et al13 described the neurovascular bundles within the digit as functioning as small compartments. When the skin of the digit reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure, and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. Our case highlights the benefit of dermotomy as well as the functional and cosmetic results that can be achieved.

Wound Care for Snakebites

There is little published on the treatment of snakebites after patients are stabilized medically for hospital discharge. Venomous snakes inject toxins that predominantly consist of enzymes (eg, phospholipase A2, phosphodiesterase, hyaluronidase, peptidase, metalloproteinase) that cause tissue destruction through diverse mechanisms.14 The venom of western pygmy rattlesnakes is hemotoxic and can cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration,4 as was the case in our patient.

Silver sulfadiazine commonly is used to prevent infection in burn patients. Given the large surface area of exposed dermis after debridement and concern for infection, silver sulfadiazine was chosen in our patient for local wound care treatment. Silver sulfadiazine is a widely available and low-cost drug.15 Its antibacterial effects are due to the silver ions, which only act superficially and therefore limit systemic absorption.16 Application should be performed in a clean manner with minimal trauma to the tissue. This technique is best achieved by using sterile gloves and applying the medication manually. A 0.0625-inch layer should be applied to entirely cover the cleaned debrided area.17 When performing application with tongue blades or cotton swabs, it is important to never “double dip.” Patient education on proper administration is imperative to a successful outcome.

Final Thoughts

Our case demonstrates the safe use of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom for the treatment of western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri) envenomation. Early administration of antivenom following pit viper rattlesnake envenomations is important to mitigate systemic effects and the extent of soft tissue damage. There are few studies on local wound care treatment after rattlesnake envenomation. This case highlights the role of dermotomy and wound care with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

- Biggers B. Management of Missouri snake bites. Mo Med. 2017;114:254-257.

- Stamm R. Sistrurus miliarius pigmy rattlesnake. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sistrurus_miliarius/

- Missouri Department of Conservation. Western pygmy rattlesnake. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/western-pygmy-rattlesnake

- AnimalSake. Facts about the pigmy rattlesnake that are sure to surprise you. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://animalsake.com/pygmy-rattlesnake

- King AM, Crim WS, Menke NB, et al. Pygmy rattlesnake envenomation treated with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom. Toxicon. 2012;60:1287-1289.

- Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1375.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:726-735.

- Cribari C. Management of poisonous snakebite. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004. https://www.hartcountyga.gov/documents/PoisonousSnakebiteTreatment.pdf

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:470-474.

- Gelman D, Bates T, Nuelle JAV. Septic arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint after rattlesnake bite. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:484.e1-484.e4.

- Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J. 1985;78:694-699.

- Corneille MG, Larson S, Stewart RM, et al. A large single-center experience with treatment of patients with crotalid envenomations: outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:848-852.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Zor F, et al. The management of pit viper envenomation of the hand. Hand (NY). 2008;3:324-331.

- Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, et al. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:641-648.

- Hummel RP, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Topical and systemic antibacterial agents in the treatment of burns. Ann Surg. 1970;172:370-384.

- Modak SM, Sampath L, Fox CL. Combined topical use of silver sulfadiazine and antibiotics as a possible solution to bacterial resistance in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:359-363.

- Oaks RJ, Cindass R. Silver sulfadiazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated January 22, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556054/

There are 375 species of poisonous snakes, with approximately 20,000 deaths worldwide each year due to snakebites, mostly in Asia and Africa.1 The death rate in the United States is 14 to 20 cases per year. In the United States, a variety of rattlesnakes are poisonous. There are 2 genera of rattlesnakes: Sistrurus (3 species) and Crotalus (23 species). The pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Sistrurus miliarius species that is divided into 3 subspecies: the Carolina pigmy rattlesnake (S miliarius miliarius), the western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri), and the dusky pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius barbouri).2

The western pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Crotalidae family. The rattlesnakes in this family also are known as pit vipers. All pit vipers have common characteristics for identification: triangular head, fangs, elliptical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit between the eyes. The western pygmy rattlesnake is found in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Tennessee.1 It is small bodied (15–20 inches)3 and grayish-brown, with a brown dorsal stripe with black blotches on its back. It is found in glades, second-growth forests near rock ledges, and areas where powerlines cut through dense forest.3 Its venom is hemorrhagic, causing tissue damage, but does not contain neurotoxins.4 Bites from the western pygmy rattlesnake often do not lead to death, but the venom, which contains numerous proteins and enzymes, does cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration at the site of envenomation and possible loss of digit.5,6

We present a case of a man who was bitten on the right third digit by a western pygmy rattlesnake. We describe the clinical course and treatment.

Case Report

A 56-year-old right-handed man presented to the emergency department with a rapidly swelling, painful hand following a snakebite to the dorsal aspect of the right third digit (Figure 1). He was able to capture a photograph of the snake at the time of injury, which helped identify it as a western pygmy rattlesnake (Figure 2). He also photographed the hand immediately after the bite occurred (Figure 3). Vitals on presentation included an elevated blood pressure of 161/100 mm Hg; no fever (temperature, 36.4 °C); and normal pulse oximetry of 98%, pulse of 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

After the snakebite, the patient’s family called the Missouri Poison Center immediately. The family identified the snake species and shared this information with the poison center. Poison control recommended calling the nearest hospitals to determine if antivenom was available and make notification of arrival.

The patient’s tetanus toxoid immunization was updated immediately upon arrival. The hand was marked to monitor swelling. Initial laboratory test results revealed the following values: sodium, 133 mmol/L (reference range, 136–145 mmol/L); potassium, 3.4 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L); lactic acid, 2.4 mmol/L (0.5–2.2 mmol/L); creatine kinase, 425 U/L (55–170 U/L); platelet count, 68/µL (150,000–450,000/µL); fibrinogen, 169 mg/dL (185–410 mg/dL); and glucose, 121 mg/dL (74–106 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood cell count and metabolic panel was unremarkable. Radiographs of the hand did not show any fractures, dislocations, or foreign bodies. Missouri Poison Center was consulted. Given the patient’s severe pain, edema beyond 40 cm, and developing ecchymosis on the inner arm, the bite was graded as a 3 on the traditional snakebite severity scale. Poison control recommended 4 to 6 vials of antivenom over 60 minutes. Six vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom were given.

The patient’s complete blood cell count remained unremarkable throughout his admission. His metabolic panel returned to normal at 6 hours postadmission: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L. His lactate and creatinine kinase were not rechecked. His fibrinogen was trending upward. Serial laboratory test results revealed fibrinogen levels of 153, 158, 161, 159, 173, and 216 mg/dL at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours, respectively. Other laboratory test results including prothrombin time (11.0 s) and international normalized ratio (0.98) remained within reference range (11–13 s and 0.80–1.39, respectively) during serial monitoring.

The patient was hospitalized for 40 hours while waiting for his fibrinogen level to normalize. The local skin necrosis worsened acutely in this 40-hour window (Figure 4). Intravenous antibiotics were not administered during the hospital stay. Before discharge, the patient was evaluated by the surgery service, who did not recommend debridement.

Following discharge, the patient consulted a wound care expert. The area of necrosis was unroofed and debrided in the outpatient setting (Figure 5). The patient was started on oral cefalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and instructed to perform twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. A hand surgeon was consulted for consideration of a reverse cross-finger flap, which was not recommended. Twice-daily dressing changes for the wound—consisting of application of silver sulfadiazine cream 1% directly to the wound followed by gauze, self-adhesive soft-rolled gauze, and elastic bandages—were performed for 2 weeks.

After 2 weeks, the wound was left open to the air and cleaned with soap and water as needed. At 6 weeks, the wound was completely healed via secondary intention, except for some minor remaining ulceration at the location of the fang entry point (Figure 6). The patient had no loss of finger function or sensation.

Surgical Management of Snakebites

The surgeon’s role in managing snakebites is controversial. Snakebites were once perceived as a surgical emergency due to symptoms mimicking compartment syndrome; however, snakebites rarely cause a true compartment syndrome.7 Prophylactic bite excision and fasciotomies are not recommended. Incision and suction of the fang marks may be beneficial if performed within 15 to 30 minutes from the time of the bite.8 With access to a surgeon in this short time period being nearly impossible, incision and suctioning of fang marks generally is not recommended.9 Retained snake fangs are a possibility, and the infection could spread to a nearby joint, causing septic arthritis,10 which would be an indication for surgical intervention. Bites to the finger often cause major swelling, and the benefits of dermotomy are documented.11 Generally, early administration of antivenom will decrease local tissue reaction and prevent additional tissue loss.12 In our patient, the decision to perform dermotomy was made when the area of necrosis had declared itself and the skin reached its elastic limit. Bozkurt et al13 described the neurovascular bundles within the digit as functioning as small compartments. When the skin of the digit reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure, and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. Our case highlights the benefit of dermotomy as well as the functional and cosmetic results that can be achieved.

Wound Care for Snakebites

There is little published on the treatment of snakebites after patients are stabilized medically for hospital discharge. Venomous snakes inject toxins that predominantly consist of enzymes (eg, phospholipase A2, phosphodiesterase, hyaluronidase, peptidase, metalloproteinase) that cause tissue destruction through diverse mechanisms.14 The venom of western pygmy rattlesnakes is hemotoxic and can cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration,4 as was the case in our patient.

Silver sulfadiazine commonly is used to prevent infection in burn patients. Given the large surface area of exposed dermis after debridement and concern for infection, silver sulfadiazine was chosen in our patient for local wound care treatment. Silver sulfadiazine is a widely available and low-cost drug.15 Its antibacterial effects are due to the silver ions, which only act superficially and therefore limit systemic absorption.16 Application should be performed in a clean manner with minimal trauma to the tissue. This technique is best achieved by using sterile gloves and applying the medication manually. A 0.0625-inch layer should be applied to entirely cover the cleaned debrided area.17 When performing application with tongue blades or cotton swabs, it is important to never “double dip.” Patient education on proper administration is imperative to a successful outcome.

Final Thoughts

Our case demonstrates the safe use of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom for the treatment of western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri) envenomation. Early administration of antivenom following pit viper rattlesnake envenomations is important to mitigate systemic effects and the extent of soft tissue damage. There are few studies on local wound care treatment after rattlesnake envenomation. This case highlights the role of dermotomy and wound care with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

There are 375 species of poisonous snakes, with approximately 20,000 deaths worldwide each year due to snakebites, mostly in Asia and Africa.1 The death rate in the United States is 14 to 20 cases per year. In the United States, a variety of rattlesnakes are poisonous. There are 2 genera of rattlesnakes: Sistrurus (3 species) and Crotalus (23 species). The pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Sistrurus miliarius species that is divided into 3 subspecies: the Carolina pigmy rattlesnake (S miliarius miliarius), the western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri), and the dusky pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius barbouri).2

The western pygmy rattlesnake belongs to the Crotalidae family. The rattlesnakes in this family also are known as pit vipers. All pit vipers have common characteristics for identification: triangular head, fangs, elliptical pupils, and a heat-sensing pit between the eyes. The western pygmy rattlesnake is found in Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Tennessee.1 It is small bodied (15–20 inches)3 and grayish-brown, with a brown dorsal stripe with black blotches on its back. It is found in glades, second-growth forests near rock ledges, and areas where powerlines cut through dense forest.3 Its venom is hemorrhagic, causing tissue damage, but does not contain neurotoxins.4 Bites from the western pygmy rattlesnake often do not lead to death, but the venom, which contains numerous proteins and enzymes, does cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration at the site of envenomation and possible loss of digit.5,6

We present a case of a man who was bitten on the right third digit by a western pygmy rattlesnake. We describe the clinical course and treatment.

Case Report

A 56-year-old right-handed man presented to the emergency department with a rapidly swelling, painful hand following a snakebite to the dorsal aspect of the right third digit (Figure 1). He was able to capture a photograph of the snake at the time of injury, which helped identify it as a western pygmy rattlesnake (Figure 2). He also photographed the hand immediately after the bite occurred (Figure 3). Vitals on presentation included an elevated blood pressure of 161/100 mm Hg; no fever (temperature, 36.4 °C); and normal pulse oximetry of 98%, pulse of 86 beats per minute, and respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute.

After the snakebite, the patient’s family called the Missouri Poison Center immediately. The family identified the snake species and shared this information with the poison center. Poison control recommended calling the nearest hospitals to determine if antivenom was available and make notification of arrival.

The patient’s tetanus toxoid immunization was updated immediately upon arrival. The hand was marked to monitor swelling. Initial laboratory test results revealed the following values: sodium, 133 mmol/L (reference range, 136–145 mmol/L); potassium, 3.4 mmol/L (3.6–5.2 mmol/L); lactic acid, 2.4 mmol/L (0.5–2.2 mmol/L); creatine kinase, 425 U/L (55–170 U/L); platelet count, 68/µL (150,000–450,000/µL); fibrinogen, 169 mg/dL (185–410 mg/dL); and glucose, 121 mg/dL (74–106 mg/dL). The remainder of the complete blood cell count and metabolic panel was unremarkable. Radiographs of the hand did not show any fractures, dislocations, or foreign bodies. Missouri Poison Center was consulted. Given the patient’s severe pain, edema beyond 40 cm, and developing ecchymosis on the inner arm, the bite was graded as a 3 on the traditional snakebite severity scale. Poison control recommended 4 to 6 vials of antivenom over 60 minutes. Six vials of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom were given.

The patient’s complete blood cell count remained unremarkable throughout his admission. His metabolic panel returned to normal at 6 hours postadmission: sodium, 139 mmol/L; potassium, 4.0 mmol/L. His lactate and creatinine kinase were not rechecked. His fibrinogen was trending upward. Serial laboratory test results revealed fibrinogen levels of 153, 158, 161, 159, 173, and 216 mg/dL at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 hours, respectively. Other laboratory test results including prothrombin time (11.0 s) and international normalized ratio (0.98) remained within reference range (11–13 s and 0.80–1.39, respectively) during serial monitoring.

The patient was hospitalized for 40 hours while waiting for his fibrinogen level to normalize. The local skin necrosis worsened acutely in this 40-hour window (Figure 4). Intravenous antibiotics were not administered during the hospital stay. Before discharge, the patient was evaluated by the surgery service, who did not recommend debridement.

Following discharge, the patient consulted a wound care expert. The area of necrosis was unroofed and debrided in the outpatient setting (Figure 5). The patient was started on oral cefalexin 500 mg twice daily for 10 days and instructed to perform twice-daily dressing changes with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%. A hand surgeon was consulted for consideration of a reverse cross-finger flap, which was not recommended. Twice-daily dressing changes for the wound—consisting of application of silver sulfadiazine cream 1% directly to the wound followed by gauze, self-adhesive soft-rolled gauze, and elastic bandages—were performed for 2 weeks.

After 2 weeks, the wound was left open to the air and cleaned with soap and water as needed. At 6 weeks, the wound was completely healed via secondary intention, except for some minor remaining ulceration at the location of the fang entry point (Figure 6). The patient had no loss of finger function or sensation.

Surgical Management of Snakebites

The surgeon’s role in managing snakebites is controversial. Snakebites were once perceived as a surgical emergency due to symptoms mimicking compartment syndrome; however, snakebites rarely cause a true compartment syndrome.7 Prophylactic bite excision and fasciotomies are not recommended. Incision and suction of the fang marks may be beneficial if performed within 15 to 30 minutes from the time of the bite.8 With access to a surgeon in this short time period being nearly impossible, incision and suctioning of fang marks generally is not recommended.9 Retained snake fangs are a possibility, and the infection could spread to a nearby joint, causing septic arthritis,10 which would be an indication for surgical intervention. Bites to the finger often cause major swelling, and the benefits of dermotomy are documented.11 Generally, early administration of antivenom will decrease local tissue reaction and prevent additional tissue loss.12 In our patient, the decision to perform dermotomy was made when the area of necrosis had declared itself and the skin reached its elastic limit. Bozkurt et al13 described the neurovascular bundles within the digit as functioning as small compartments. When the skin of the digit reaches its elastic limit, pressure within the compartment may exceed the capillary closing pressure, and the integrity of small vessels and nerves may be compromised. Our case highlights the benefit of dermotomy as well as the functional and cosmetic results that can be achieved.

Wound Care for Snakebites

There is little published on the treatment of snakebites after patients are stabilized medically for hospital discharge. Venomous snakes inject toxins that predominantly consist of enzymes (eg, phospholipase A2, phosphodiesterase, hyaluronidase, peptidase, metalloproteinase) that cause tissue destruction through diverse mechanisms.14 The venom of western pygmy rattlesnakes is hemotoxic and can cause necrotic hemorrhagic ulceration,4 as was the case in our patient.

Silver sulfadiazine commonly is used to prevent infection in burn patients. Given the large surface area of exposed dermis after debridement and concern for infection, silver sulfadiazine was chosen in our patient for local wound care treatment. Silver sulfadiazine is a widely available and low-cost drug.15 Its antibacterial effects are due to the silver ions, which only act superficially and therefore limit systemic absorption.16 Application should be performed in a clean manner with minimal trauma to the tissue. This technique is best achieved by using sterile gloves and applying the medication manually. A 0.0625-inch layer should be applied to entirely cover the cleaned debrided area.17 When performing application with tongue blades or cotton swabs, it is important to never “double dip.” Patient education on proper administration is imperative to a successful outcome.

Final Thoughts

Our case demonstrates the safe use of Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom for the treatment of western pygmy rattlesnake (S miliarius streckeri) envenomation. Early administration of antivenom following pit viper rattlesnake envenomations is important to mitigate systemic effects and the extent of soft tissue damage. There are few studies on local wound care treatment after rattlesnake envenomation. This case highlights the role of dermotomy and wound care with silver sulfadiazine cream 1%.

- Biggers B. Management of Missouri snake bites. Mo Med. 2017;114:254-257.

- Stamm R. Sistrurus miliarius pigmy rattlesnake. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sistrurus_miliarius/

- Missouri Department of Conservation. Western pygmy rattlesnake. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/western-pygmy-rattlesnake

- AnimalSake. Facts about the pigmy rattlesnake that are sure to surprise you. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://animalsake.com/pygmy-rattlesnake

- King AM, Crim WS, Menke NB, et al. Pygmy rattlesnake envenomation treated with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom. Toxicon. 2012;60:1287-1289.

- Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1375.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:726-735.

- Cribari C. Management of poisonous snakebite. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004. https://www.hartcountyga.gov/documents/PoisonousSnakebiteTreatment.pdf

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:470-474.

- Gelman D, Bates T, Nuelle JAV. Septic arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint after rattlesnake bite. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:484.e1-484.e4.

- Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J. 1985;78:694-699.

- Corneille MG, Larson S, Stewart RM, et al. A large single-center experience with treatment of patients with crotalid envenomations: outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:848-852.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Zor F, et al. The management of pit viper envenomation of the hand. Hand (NY). 2008;3:324-331.

- Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, et al. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:641-648.

- Hummel RP, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Topical and systemic antibacterial agents in the treatment of burns. Ann Surg. 1970;172:370-384.

- Modak SM, Sampath L, Fox CL. Combined topical use of silver sulfadiazine and antibiotics as a possible solution to bacterial resistance in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:359-363.

- Oaks RJ, Cindass R. Silver sulfadiazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated January 22, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556054/

- Biggers B. Management of Missouri snake bites. Mo Med. 2017;114:254-257.

- Stamm R. Sistrurus miliarius pigmy rattlesnake. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Sistrurus_miliarius/

- Missouri Department of Conservation. Western pygmy rattlesnake. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://mdc.mo.gov/discover-nature/field-guide/western-pygmy-rattlesnake

- AnimalSake. Facts about the pigmy rattlesnake that are sure to surprise you. Accessed September 18, 2024. https://animalsake.com/pygmy-rattlesnake

- King AM, Crim WS, Menke NB, et al. Pygmy rattlesnake envenomation treated with crotalidae polyvalent immune fab antivenom. Toxicon. 2012;60:1287-1289.

- Juckett G, Hancox JG. Venomous snakebites in the United States: management review and update. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:1367-1375.

- Toschlog EA, Bauer CR, Hall EL, et al. Surgical considerations in the management of pit viper snake envenomation. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:726-735.

- Cribari C. Management of poisonous snakebite. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2004. https://www.hartcountyga.gov/documents/PoisonousSnakebiteTreatment.pdf

- Walker JP, Morrison RL. Current management of copperhead snakebite. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:470-474.

- Gelman D, Bates T, Nuelle JAV. Septic arthritis of the proximal interphalangeal joint after rattlesnake bite. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:484.e1-484.e4.

- Watt CH Jr. Treatment of poisonous snakebite with emphasis on digit dermotomy. South Med J. 1985;78:694-699.

- Corneille MG, Larson S, Stewart RM, et al. A large single-center experience with treatment of patients with crotalid envenomations: outcomes with and evolution of antivenin therapy. Am J Surg. 2006;192:848-852.

- Bozkurt M, Kulahci Y, Zor F, et al. The management of pit viper envenomation of the hand. Hand (NY). 2008;3:324-331.

- Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, et al. The current concepts in management of animal (dog, cat, snake, scorpion) and human bite wounds. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:641-648.

- Hummel RP, MacMillan BG, Altemeier WA. Topical and systemic antibacterial agents in the treatment of burns. Ann Surg. 1970;172:370-384.

- Modak SM, Sampath L, Fox CL. Combined topical use of silver sulfadiazine and antibiotics as a possible solution to bacterial resistance in burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9:359-363.

- Oaks RJ, Cindass R. Silver sulfadiazine. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated January 22, 2023. Accessed September 23, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556054/

Practice Points

- Patients should seek medical attention immediately for western pygmy rattlesnake bites for early initiation of antivenom treatment.

- Contact the closest emergency department to confirm they are equipped to treat rattlesnake bites and notify them of a pending arrival.

- Consider dermotomy or local debridement of bites involving the digits.

- Monitor the wound in the days and weeks following the bite to ensure adequate healing.

Reflectance Confocal Microscopy as a Diagnostic Aid in Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Mango Sap

The mango tree (Mangifera indica) produces nutrient-dense fruit—known colloquially as the “king of fruits”—that is widely consumed across the world. Native to southern Asia, the mango tree is a member of the Anacardiaceae family, a large family of flowering, fruit-bearing plants.1 Many members of the Anacardiaceae family, which includes poison ivy and poison oak, are known to produce urushiol, a skin irritant associated with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2 Interestingly, despite its widespread consumption and categorization in the Anacardiaceae family, allergic reactions to mango are comparatively rare; they occur as either immediate type I hypersensitivity reactions manifesting with rapid-onset symptoms such as urticaria, wheezing, and angioedema, or delayed type IV hypersensitivity reactions manifesting as ACD.3 Although exposure to components of the mango tree has been most characteristically linked to type IV hypersensitivity reactions, there remain fewer than 40 reported cases of mango-induced ACD since it was first described in 1939.4

Evaluation of ACD most commonly includes a thorough clinical assessment with diagnostic support from patch testing and histopathologic review following skin biopsy. In recent years, reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) has shown promising potential to join the repertoire of diagnostic tools for ACD by enabling dynamic and high-resolution imaging of contact dermatitis in vivo.5-10 Reflectance confocal microscopy is a noninvasive optical imaging technique that uses a low-energy diode laser to penetrate the layers of the skin. The resulting reflected light generates images that facilitate visualization of cutaneous structures to the depth of the papillary dermis.11 While it is most commonly used in skin cancer diagnostics, preliminary studies also have shown an emerging role for RCM in the evaluation of eczematous and inflammatory skin disease, including contact dermatitis.5-10 Herein, we present a unique case of mango sap–induced ACD imaged and diagnosed in real time via RCM.

Case Report

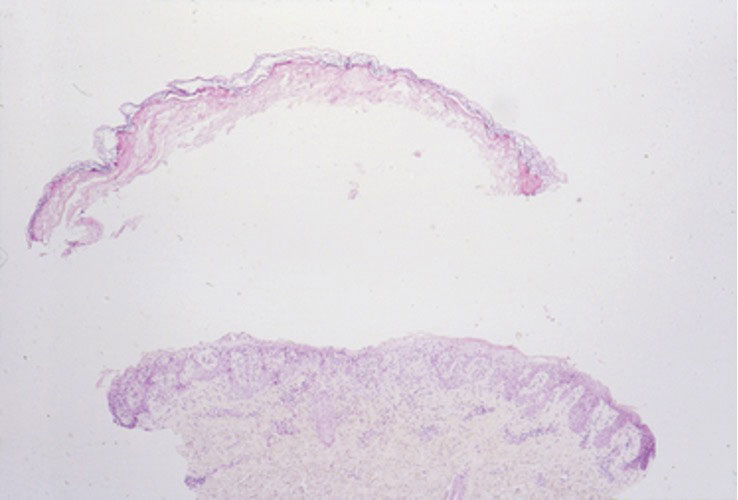

A 39-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a pruritic vesicular eruption on the right leg of 2 weeks’ duration that initially had developed within 7 days of exposure to mango tree sap (Figure 1). The patient reported having experienced similar pruritic eruptions in the past following contact with mango sap while eating mangos but denied any history of reactions from ingestion of the fruit. She also reported a history of robust reactions to poison ivy; however, a timeline specifying the order of first exposure to these irritants was unknown. She denied any personal or family history of atopic conditions.

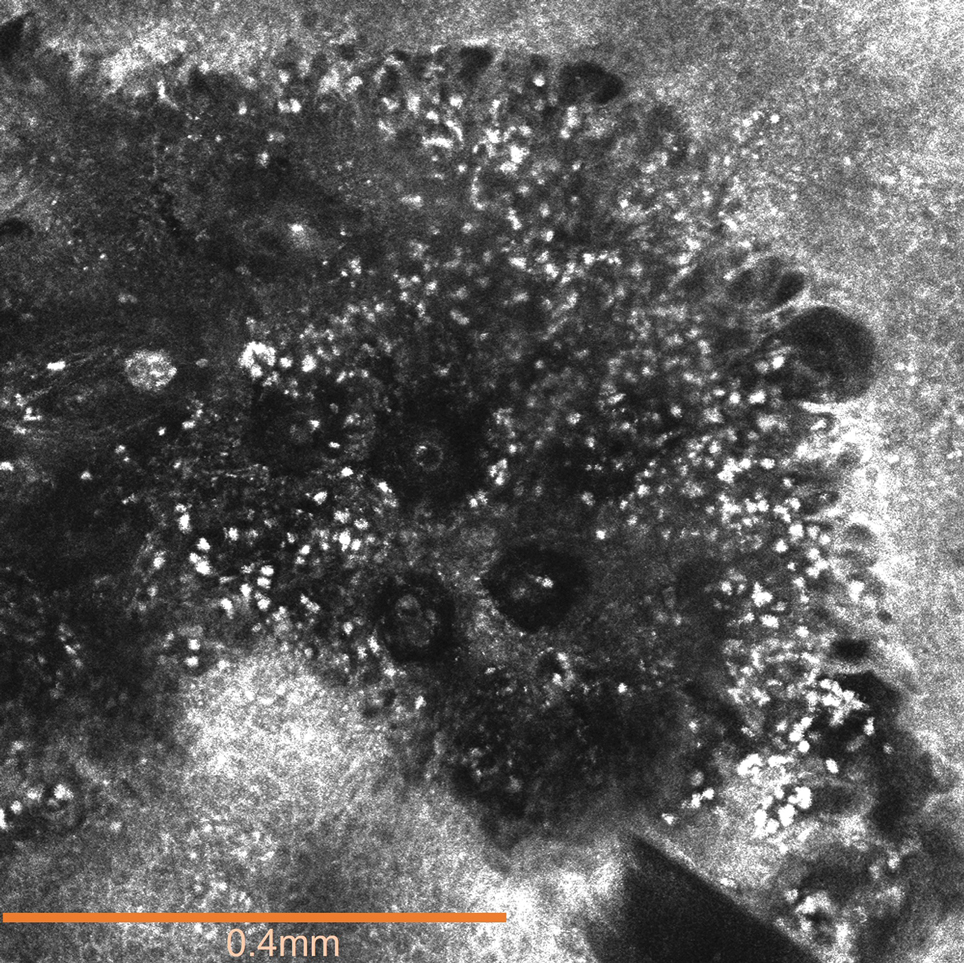

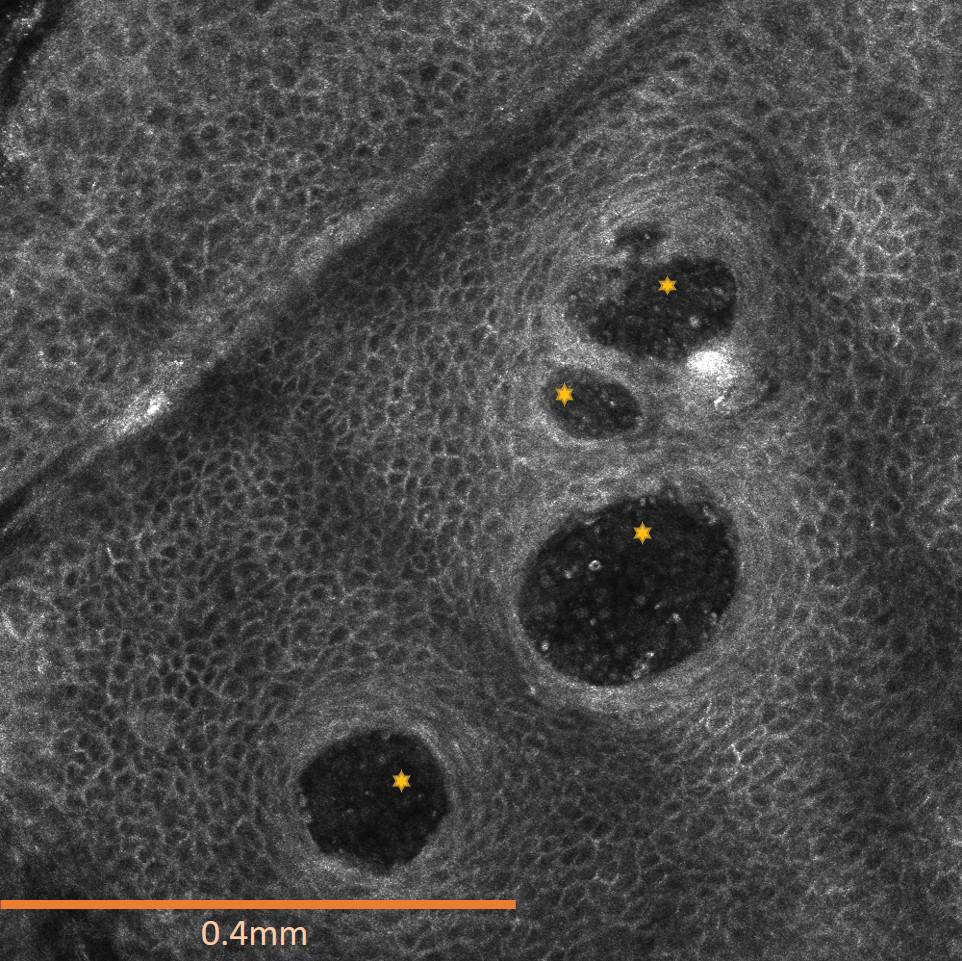

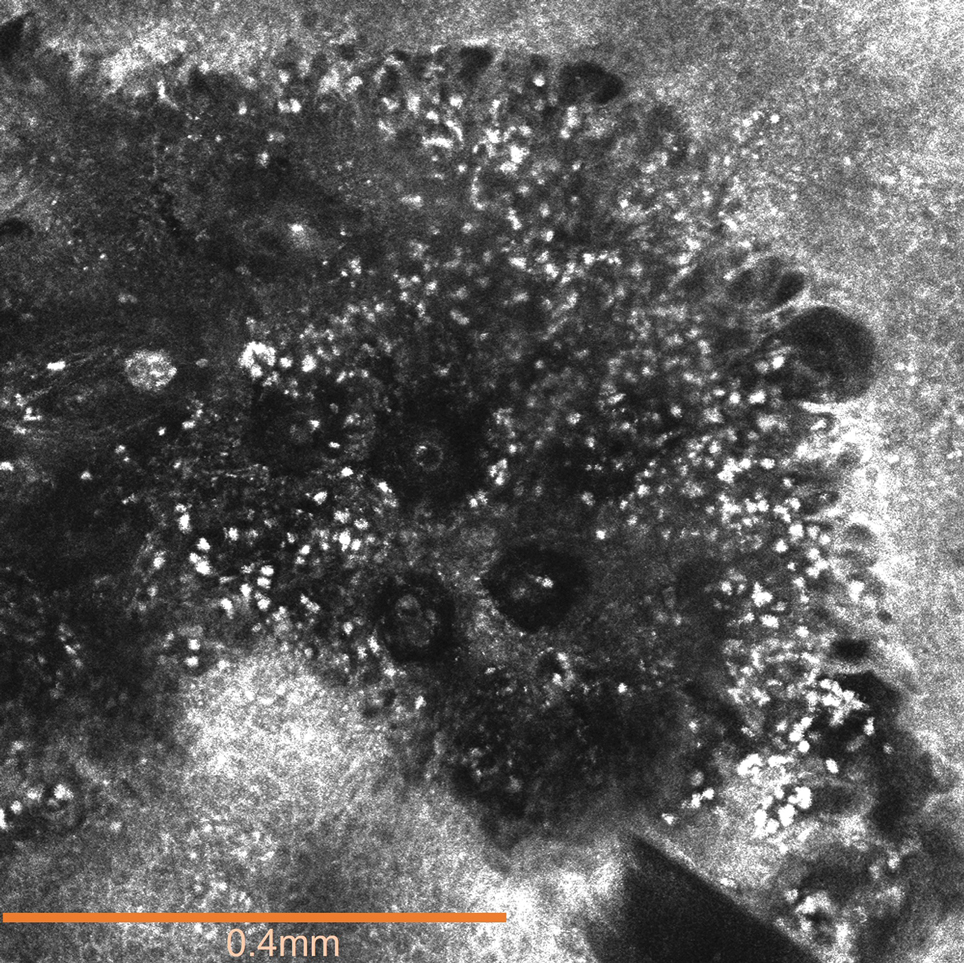

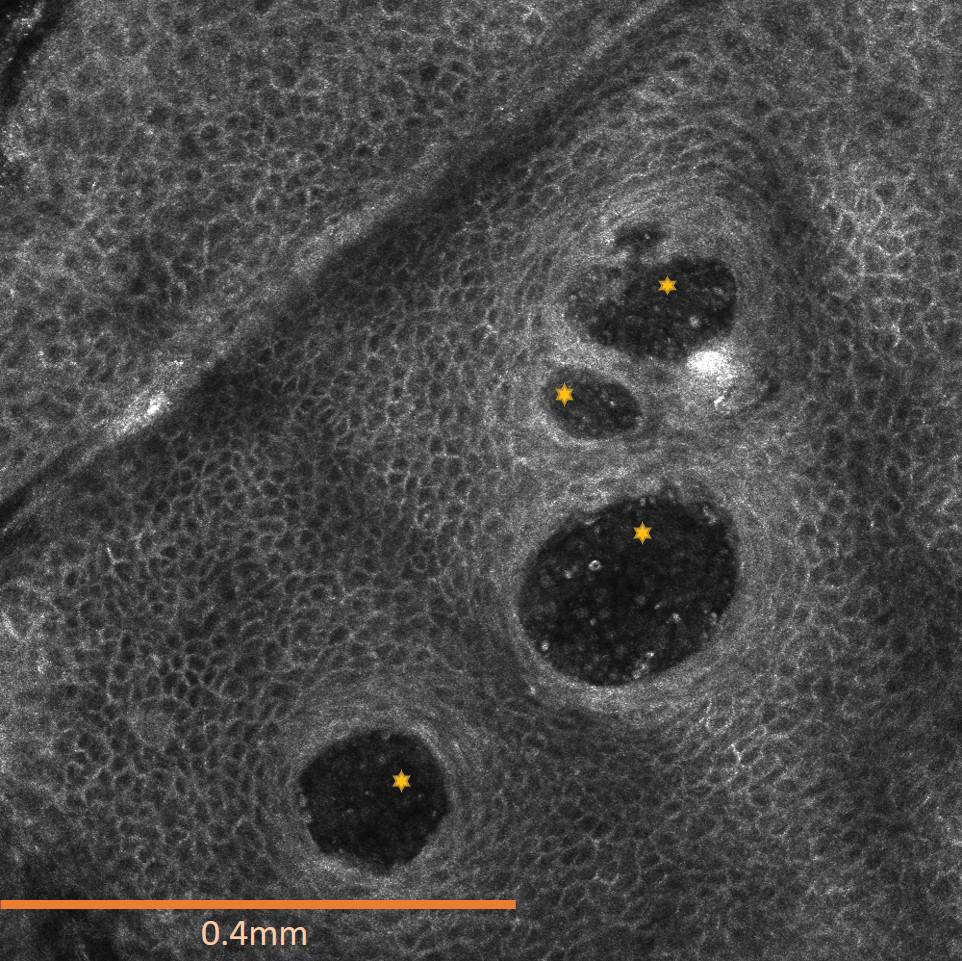

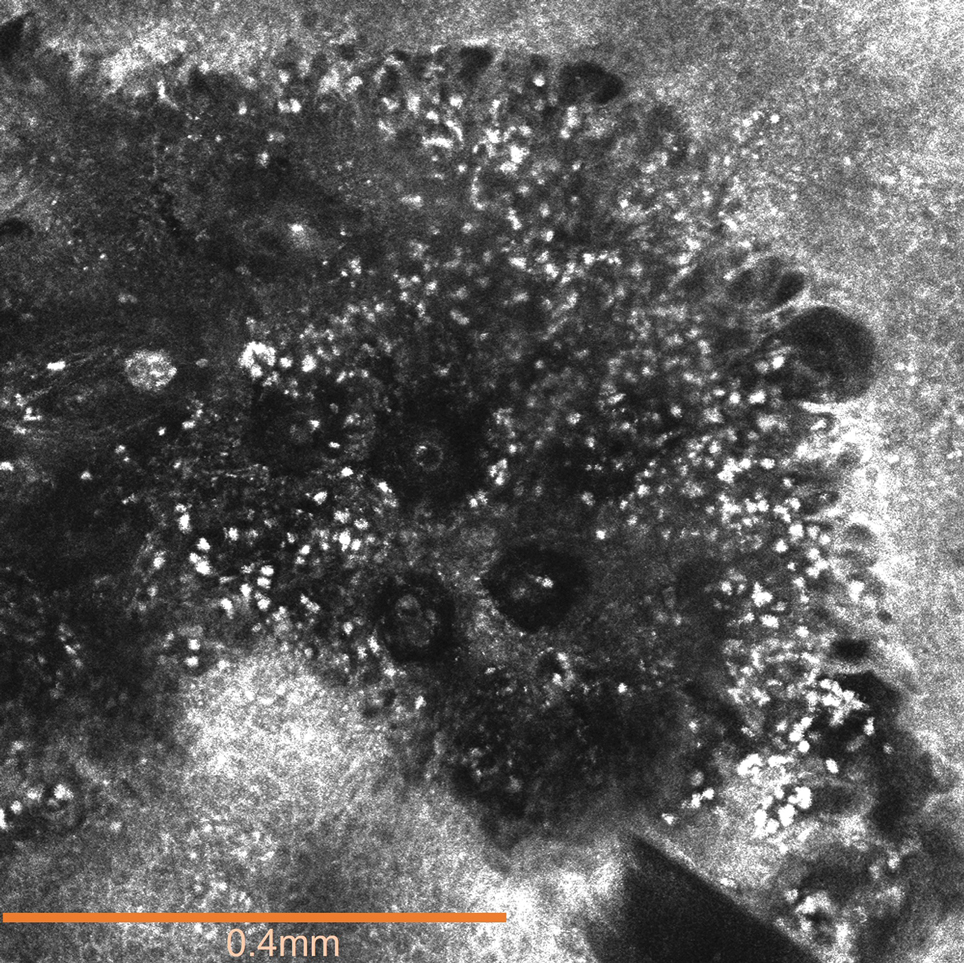

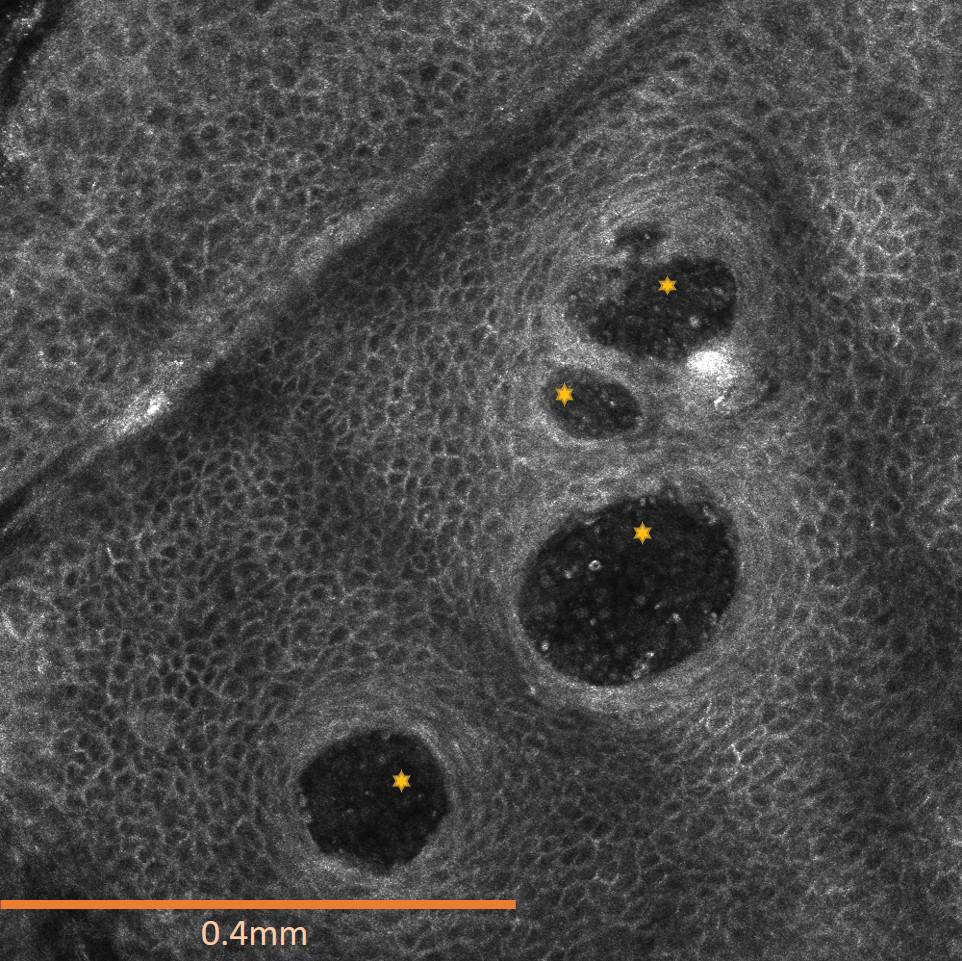

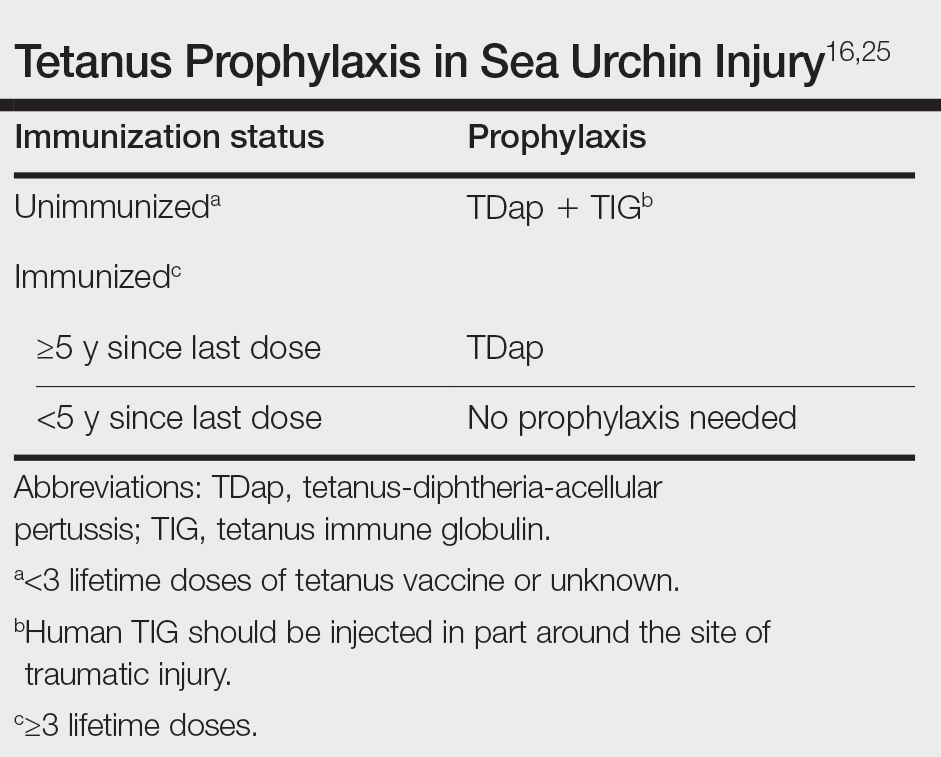

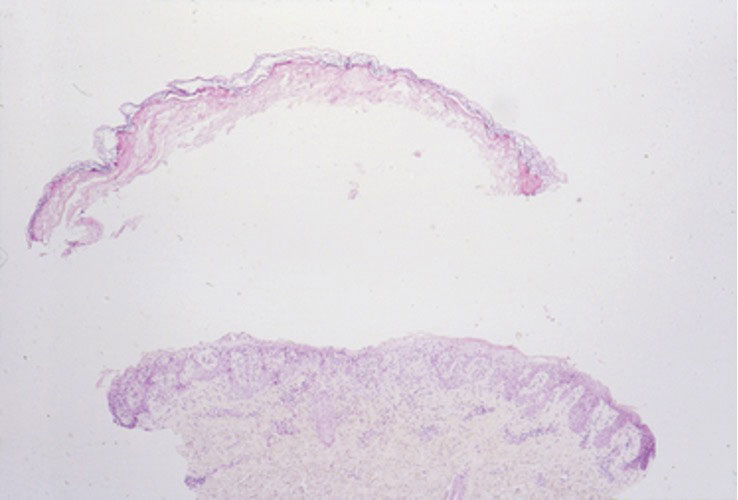

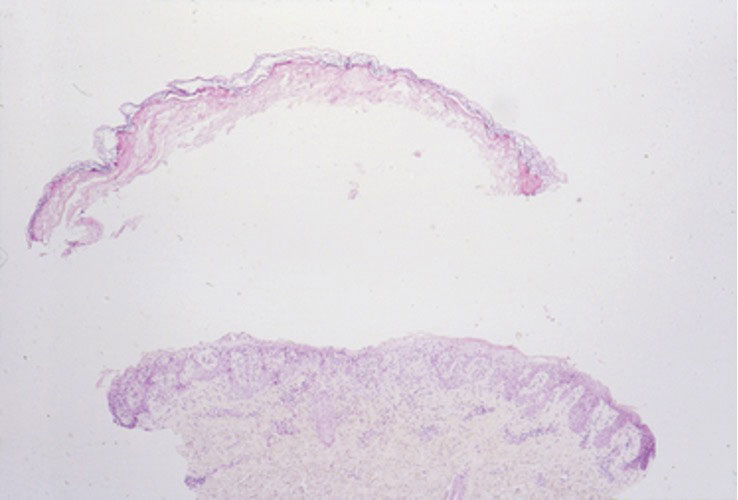

The affected skin was imaged in real time during clinic using RCM, which showed an inflammatory infiltrate represented by dark spongiotic vesicles containing bright cells (Figure 2). Additional RCM imaging at the level of the stratum spinosum showed dark spongiotic areas with bright inflammatory cells infiltrating the vesicles, which were surrounded by normal skin showing a typical epidermal honeycomb pattern (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of ACD secondary to exposure to mango sap. The patient was advised to apply clobetasol cream 0.05% to the affected area. Notable improvement of the rash was noted within 10 days of treatment.

Comment

Exposure to the mango tree and its fruit is a rare cause of ACD, with few reported cases in the literature. The majority of known instances have occurred in non–mango-cultivating countries, largely the United States, although cases also have been reported in Canada, Australia, France, Japan, and Thailand.3,12 Mango-induced contact allergy follows a roughly equal distribution between males and females and most often occurs in young adults during the third and fourth decades of life.4,12-21 Importantly, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to mango can manifest as either localized or systemic ACD. Localized ACD can be induced via direct contact with the mango tree and its components or ingestion of the fruit.3,12,22 Conversely, systemic ACD is primarily stimulated by ingestion of the fruit. In our case, the patient had no history of allergy following mango ingestion, and her ACD was prompted by isolated contact with mango sap. The time from exposure to symptom onset of known instances of mango ACD varies widely, ranging from less than 24 hours to as long as 9 days.3,12 Diagnosis of mango-induced ACD largely is guided by clinical findings. Presenting symptoms often include an eczematous, vesicular, pruritic rash on affected areas of the skin, frequently the head, neck, and extremities. Patients also commonly present with linear papulovesicular lesions and periorbital or perioral edema.

The suspected allergens responsible for mango-induced ACD are derived from resorcinol—specifically heptadecadienyl resorcinol, heptadecenyl resorcinol, and pentadecyl resorcinol, which are collectively known as mango allergens.23 These allergens can be found within the pulp and skin of the mango fruit as well as in the bark and leaves of the mango tree, which may explain observed allergic reactions to components of both the mango fruit and tree.12 Similar to these resorcinol derivatives, the urushiol resin found in poison ivy and poison oak is a catechol derivative.2 Importantly, both resorcinols and catechols are isomers of the same aromatic phenol—dihydroxybenzene. Because of these similarities, it is thought that the allergens in mangos may cross-react with urushiol in poison ivy or poison oak.23 Alongside their shared categorization in the Anacardiaceae family, it is hypothesized that this cross-reactivity underlies the sensitization that has been noted between mango and poison ivy or poison oak exposure.12,23,24 Thus, ACD often can occur on initial contact with the mango tree or its components, as a prior exposure to poison ivy or poison oak may serve as the inciting factor for hypersensitization. The majority of reported cases in the literature also occurred in countries where exposure to poison ivy and poison oak are common, further supporting the notion that these compounds may provide a sensitizing trigger for a future mango contact allergy.12

A detailed clinical history combined with adjunctive diagnostic support from patch testing and histopathology of biopsied skin lesions classically are used in the diagnosis of mango-induced ACD. Due to its ability to provide quick and noninvasive in vivo imaging of cutaneous lesions, RCM's applications have expanded to include evaluation of inflammatory skin diseases such as contact dermatitis. Many features of contact dermatitis identified via RCM are common between ACD and irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and include disruption of the stratum corneum, parakeratosis, vesiculation, spongiosis, and exocytosis.6,10,25 Studies also have described features shown via RCM that are unique to ACD, including vasodilation and intercellular edema, compared to more distinct targetoid keratinocytes and detached corneocytes seen in ICD.6,10,25 Studies by Astner et al5,6 demonstrated a wide range of sensitivity from 52% to 96% and a high specificity of RCM greater than 95% for many of the aforementioned features of contact dermatitis, including disruption of the stratum corneum, parakeratosis, spongiosis, and exocytosis. Additional studies have further strengthened these findings, demonstrating sensitivity and specificity values of 83% and 92% for contact dermatitis under RCM, respectively.26 Importantly, given the similarities and potentially large overlap of features between ACD and ICD identified via RCM as well as findings seen on physical examination and histopathology, an emphasis on clinical correlation is essential when differentiating between these 2 variants of contact dermatitis. Thus, taken in consideration with clinical contexts, RCM has shown potent diagnostic accuracy and great potential to support the evaluation of ACD alongside patch testing and histopathology.

Final Thoughts

Contact allergy to the mango tree and its components is uncommon. We report a unique case of mango sap–induced ACD evaluated and diagnosed via dynamic visualization under RCM. As a noninvasive and reproducible imaging technique with resolutions comparable to histopathologic analysis, RCM is a promising tool that can be used to support the diagnostic evaluation of ACD.

- Shah KA, Patel MB, Patel RJ, et al. Mangifera indica (mango). Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:42-48.

- Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron toxicity. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 16, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866

- Sareen R, Shah A. Hypersensitivity manifestations to the fruit mango. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:43-49.

- Zakon SJ. Contact dermatitis due to mango. JAMA. 1939;113:1808.

- Astner S, Gonzalez E, Cheung A, et al. Pilot study on the sensitivity and specificity of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:986-992.

- Astner S, Gonzalez S, Gonzalez E. Noninvasive evaluation of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Dermatitis. 2006;17:182-191.

- Csuka EA, Ward SC, Ekelem C, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and multiphoton microscopy in inflammatory skin disease diagnosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2021;53:776-797.

- Guichard A, Fanian F, Girardin P, et al. Allergic patch test and contact dermatitis by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2014;141:805-807.

- Sakanashi EN, Matsumura M, Kikuchi K, et al. A comparative study of allergic contact dermatitis by patch test versus reflectance confocal laser microscopy, with nickel and cobalt. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:705-711.

- Swindells K, Burnett N, Rius-Diaz F, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy may differentiate acute allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:220-228.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels JM, Rabinovitz H, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy: principles, basic terminology, clinical indications, limitations, and practical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1-14.

- Berghea EC, Craiu M, Ali S, et al. Contact allergy induced by mango (Mangifera indica): a relevant topic? Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:1240.

- O’Hern K, Zhang F, Zug KA, et al. “Mango slice” dermatitis: pediatric allergic contact dermatitis to mango pulp and skin. Dermatitis. 2022;33:E46-E47.

- Raison-Peyron N, Aljaber F, Al Ali OA, et al. Mango dermatitis: an unusual cause of eyelid dermatitis in France. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:599-600.

- Alipour Tehrany Y, Coulombe J. Mango allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:241-242.

- Yoo MJ, Carius BM. Mango dermatitis after urushiol sensitization. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:361-363.

- Miyazawa H, Nishie W, Hata H, et al. A severe case of mango dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E160-E161.

- Trehan I, Meuli GJ. Mango contact allergy. J Travel Med. 2010;17:284.

- Wiwanitkit V. Mango dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:158.

- Weinstein S, Bassiri-Tehrani S, Cohen DE. Allergic contact dermatitis to mango flesh. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:195-196.

- Calvert ML, Robertson I, Samaratunga H. Mango dermatitis: allergic contact dermatitis to Mangifera indica. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:59-60.

- Thoo CH, Freeman S. Hypersensitivity reaction to the ingestion of mango flesh. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:116-119.

- Oka K, Saito F, Yasuhara T, et al. A study of cross-reactions between mango contact allergens and urushiol. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:292-296.

- Keil H, Wasserman D, Dawson CR. Mango dermatitis and its relationship to poison ivy hypersensitivity. Ann Allergy. 1946;4: 268-281.

- Maarouf M, Costello CM, Gonzalez S, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: emerging role in noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of eczematous dermatoses. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:626-636.

- Koller S, Gerger A, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of erythematosquamous skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:536-540.

The mango tree (Mangifera indica) produces nutrient-dense fruit—known colloquially as the “king of fruits”—that is widely consumed across the world. Native to southern Asia, the mango tree is a member of the Anacardiaceae family, a large family of flowering, fruit-bearing plants.1 Many members of the Anacardiaceae family, which includes poison ivy and poison oak, are known to produce urushiol, a skin irritant associated with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2 Interestingly, despite its widespread consumption and categorization in the Anacardiaceae family, allergic reactions to mango are comparatively rare; they occur as either immediate type I hypersensitivity reactions manifesting with rapid-onset symptoms such as urticaria, wheezing, and angioedema, or delayed type IV hypersensitivity reactions manifesting as ACD.3 Although exposure to components of the mango tree has been most characteristically linked to type IV hypersensitivity reactions, there remain fewer than 40 reported cases of mango-induced ACD since it was first described in 1939.4

Evaluation of ACD most commonly includes a thorough clinical assessment with diagnostic support from patch testing and histopathologic review following skin biopsy. In recent years, reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) has shown promising potential to join the repertoire of diagnostic tools for ACD by enabling dynamic and high-resolution imaging of contact dermatitis in vivo.5-10 Reflectance confocal microscopy is a noninvasive optical imaging technique that uses a low-energy diode laser to penetrate the layers of the skin. The resulting reflected light generates images that facilitate visualization of cutaneous structures to the depth of the papillary dermis.11 While it is most commonly used in skin cancer diagnostics, preliminary studies also have shown an emerging role for RCM in the evaluation of eczematous and inflammatory skin disease, including contact dermatitis.5-10 Herein, we present a unique case of mango sap–induced ACD imaged and diagnosed in real time via RCM.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a pruritic vesicular eruption on the right leg of 2 weeks’ duration that initially had developed within 7 days of exposure to mango tree sap (Figure 1). The patient reported having experienced similar pruritic eruptions in the past following contact with mango sap while eating mangos but denied any history of reactions from ingestion of the fruit. She also reported a history of robust reactions to poison ivy; however, a timeline specifying the order of first exposure to these irritants was unknown. She denied any personal or family history of atopic conditions.

The affected skin was imaged in real time during clinic using RCM, which showed an inflammatory infiltrate represented by dark spongiotic vesicles containing bright cells (Figure 2). Additional RCM imaging at the level of the stratum spinosum showed dark spongiotic areas with bright inflammatory cells infiltrating the vesicles, which were surrounded by normal skin showing a typical epidermal honeycomb pattern (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of ACD secondary to exposure to mango sap. The patient was advised to apply clobetasol cream 0.05% to the affected area. Notable improvement of the rash was noted within 10 days of treatment.

Comment

Exposure to the mango tree and its fruit is a rare cause of ACD, with few reported cases in the literature. The majority of known instances have occurred in non–mango-cultivating countries, largely the United States, although cases also have been reported in Canada, Australia, France, Japan, and Thailand.3,12 Mango-induced contact allergy follows a roughly equal distribution between males and females and most often occurs in young adults during the third and fourth decades of life.4,12-21 Importantly, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to mango can manifest as either localized or systemic ACD. Localized ACD can be induced via direct contact with the mango tree and its components or ingestion of the fruit.3,12,22 Conversely, systemic ACD is primarily stimulated by ingestion of the fruit. In our case, the patient had no history of allergy following mango ingestion, and her ACD was prompted by isolated contact with mango sap. The time from exposure to symptom onset of known instances of mango ACD varies widely, ranging from less than 24 hours to as long as 9 days.3,12 Diagnosis of mango-induced ACD largely is guided by clinical findings. Presenting symptoms often include an eczematous, vesicular, pruritic rash on affected areas of the skin, frequently the head, neck, and extremities. Patients also commonly present with linear papulovesicular lesions and periorbital or perioral edema.

The suspected allergens responsible for mango-induced ACD are derived from resorcinol—specifically heptadecadienyl resorcinol, heptadecenyl resorcinol, and pentadecyl resorcinol, which are collectively known as mango allergens.23 These allergens can be found within the pulp and skin of the mango fruit as well as in the bark and leaves of the mango tree, which may explain observed allergic reactions to components of both the mango fruit and tree.12 Similar to these resorcinol derivatives, the urushiol resin found in poison ivy and poison oak is a catechol derivative.2 Importantly, both resorcinols and catechols are isomers of the same aromatic phenol—dihydroxybenzene. Because of these similarities, it is thought that the allergens in mangos may cross-react with urushiol in poison ivy or poison oak.23 Alongside their shared categorization in the Anacardiaceae family, it is hypothesized that this cross-reactivity underlies the sensitization that has been noted between mango and poison ivy or poison oak exposure.12,23,24 Thus, ACD often can occur on initial contact with the mango tree or its components, as a prior exposure to poison ivy or poison oak may serve as the inciting factor for hypersensitization. The majority of reported cases in the literature also occurred in countries where exposure to poison ivy and poison oak are common, further supporting the notion that these compounds may provide a sensitizing trigger for a future mango contact allergy.12

A detailed clinical history combined with adjunctive diagnostic support from patch testing and histopathology of biopsied skin lesions classically are used in the diagnosis of mango-induced ACD. Due to its ability to provide quick and noninvasive in vivo imaging of cutaneous lesions, RCM's applications have expanded to include evaluation of inflammatory skin diseases such as contact dermatitis. Many features of contact dermatitis identified via RCM are common between ACD and irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and include disruption of the stratum corneum, parakeratosis, vesiculation, spongiosis, and exocytosis.6,10,25 Studies also have described features shown via RCM that are unique to ACD, including vasodilation and intercellular edema, compared to more distinct targetoid keratinocytes and detached corneocytes seen in ICD.6,10,25 Studies by Astner et al5,6 demonstrated a wide range of sensitivity from 52% to 96% and a high specificity of RCM greater than 95% for many of the aforementioned features of contact dermatitis, including disruption of the stratum corneum, parakeratosis, spongiosis, and exocytosis. Additional studies have further strengthened these findings, demonstrating sensitivity and specificity values of 83% and 92% for contact dermatitis under RCM, respectively.26 Importantly, given the similarities and potentially large overlap of features between ACD and ICD identified via RCM as well as findings seen on physical examination and histopathology, an emphasis on clinical correlation is essential when differentiating between these 2 variants of contact dermatitis. Thus, taken in consideration with clinical contexts, RCM has shown potent diagnostic accuracy and great potential to support the evaluation of ACD alongside patch testing and histopathology.

Final Thoughts

Contact allergy to the mango tree and its components is uncommon. We report a unique case of mango sap–induced ACD evaluated and diagnosed via dynamic visualization under RCM. As a noninvasive and reproducible imaging technique with resolutions comparable to histopathologic analysis, RCM is a promising tool that can be used to support the diagnostic evaluation of ACD.

The mango tree (Mangifera indica) produces nutrient-dense fruit—known colloquially as the “king of fruits”—that is widely consumed across the world. Native to southern Asia, the mango tree is a member of the Anacardiaceae family, a large family of flowering, fruit-bearing plants.1 Many members of the Anacardiaceae family, which includes poison ivy and poison oak, are known to produce urushiol, a skin irritant associated with allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2 Interestingly, despite its widespread consumption and categorization in the Anacardiaceae family, allergic reactions to mango are comparatively rare; they occur as either immediate type I hypersensitivity reactions manifesting with rapid-onset symptoms such as urticaria, wheezing, and angioedema, or delayed type IV hypersensitivity reactions manifesting as ACD.3 Although exposure to components of the mango tree has been most characteristically linked to type IV hypersensitivity reactions, there remain fewer than 40 reported cases of mango-induced ACD since it was first described in 1939.4

Evaluation of ACD most commonly includes a thorough clinical assessment with diagnostic support from patch testing and histopathologic review following skin biopsy. In recent years, reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) has shown promising potential to join the repertoire of diagnostic tools for ACD by enabling dynamic and high-resolution imaging of contact dermatitis in vivo.5-10 Reflectance confocal microscopy is a noninvasive optical imaging technique that uses a low-energy diode laser to penetrate the layers of the skin. The resulting reflected light generates images that facilitate visualization of cutaneous structures to the depth of the papillary dermis.11 While it is most commonly used in skin cancer diagnostics, preliminary studies also have shown an emerging role for RCM in the evaluation of eczematous and inflammatory skin disease, including contact dermatitis.5-10 Herein, we present a unique case of mango sap–induced ACD imaged and diagnosed in real time via RCM.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a pruritic vesicular eruption on the right leg of 2 weeks’ duration that initially had developed within 7 days of exposure to mango tree sap (Figure 1). The patient reported having experienced similar pruritic eruptions in the past following contact with mango sap while eating mangos but denied any history of reactions from ingestion of the fruit. She also reported a history of robust reactions to poison ivy; however, a timeline specifying the order of first exposure to these irritants was unknown. She denied any personal or family history of atopic conditions.

The affected skin was imaged in real time during clinic using RCM, which showed an inflammatory infiltrate represented by dark spongiotic vesicles containing bright cells (Figure 2). Additional RCM imaging at the level of the stratum spinosum showed dark spongiotic areas with bright inflammatory cells infiltrating the vesicles, which were surrounded by normal skin showing a typical epidermal honeycomb pattern (Figure 3). These findings were diagnostic of ACD secondary to exposure to mango sap. The patient was advised to apply clobetasol cream 0.05% to the affected area. Notable improvement of the rash was noted within 10 days of treatment.

Comment

Exposure to the mango tree and its fruit is a rare cause of ACD, with few reported cases in the literature. The majority of known instances have occurred in non–mango-cultivating countries, largely the United States, although cases also have been reported in Canada, Australia, France, Japan, and Thailand.3,12 Mango-induced contact allergy follows a roughly equal distribution between males and females and most often occurs in young adults during the third and fourth decades of life.4,12-21 Importantly, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to mango can manifest as either localized or systemic ACD. Localized ACD can be induced via direct contact with the mango tree and its components or ingestion of the fruit.3,12,22 Conversely, systemic ACD is primarily stimulated by ingestion of the fruit. In our case, the patient had no history of allergy following mango ingestion, and her ACD was prompted by isolated contact with mango sap. The time from exposure to symptom onset of known instances of mango ACD varies widely, ranging from less than 24 hours to as long as 9 days.3,12 Diagnosis of mango-induced ACD largely is guided by clinical findings. Presenting symptoms often include an eczematous, vesicular, pruritic rash on affected areas of the skin, frequently the head, neck, and extremities. Patients also commonly present with linear papulovesicular lesions and periorbital or perioral edema.

The suspected allergens responsible for mango-induced ACD are derived from resorcinol—specifically heptadecadienyl resorcinol, heptadecenyl resorcinol, and pentadecyl resorcinol, which are collectively known as mango allergens.23 These allergens can be found within the pulp and skin of the mango fruit as well as in the bark and leaves of the mango tree, which may explain observed allergic reactions to components of both the mango fruit and tree.12 Similar to these resorcinol derivatives, the urushiol resin found in poison ivy and poison oak is a catechol derivative.2 Importantly, both resorcinols and catechols are isomers of the same aromatic phenol—dihydroxybenzene. Because of these similarities, it is thought that the allergens in mangos may cross-react with urushiol in poison ivy or poison oak.23 Alongside their shared categorization in the Anacardiaceae family, it is hypothesized that this cross-reactivity underlies the sensitization that has been noted between mango and poison ivy or poison oak exposure.12,23,24 Thus, ACD often can occur on initial contact with the mango tree or its components, as a prior exposure to poison ivy or poison oak may serve as the inciting factor for hypersensitization. The majority of reported cases in the literature also occurred in countries where exposure to poison ivy and poison oak are common, further supporting the notion that these compounds may provide a sensitizing trigger for a future mango contact allergy.12

A detailed clinical history combined with adjunctive diagnostic support from patch testing and histopathology of biopsied skin lesions classically are used in the diagnosis of mango-induced ACD. Due to its ability to provide quick and noninvasive in vivo imaging of cutaneous lesions, RCM's applications have expanded to include evaluation of inflammatory skin diseases such as contact dermatitis. Many features of contact dermatitis identified via RCM are common between ACD and irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) and include disruption of the stratum corneum, parakeratosis, vesiculation, spongiosis, and exocytosis.6,10,25 Studies also have described features shown via RCM that are unique to ACD, including vasodilation and intercellular edema, compared to more distinct targetoid keratinocytes and detached corneocytes seen in ICD.6,10,25 Studies by Astner et al5,6 demonstrated a wide range of sensitivity from 52% to 96% and a high specificity of RCM greater than 95% for many of the aforementioned features of contact dermatitis, including disruption of the stratum corneum, parakeratosis, spongiosis, and exocytosis. Additional studies have further strengthened these findings, demonstrating sensitivity and specificity values of 83% and 92% for contact dermatitis under RCM, respectively.26 Importantly, given the similarities and potentially large overlap of features between ACD and ICD identified via RCM as well as findings seen on physical examination and histopathology, an emphasis on clinical correlation is essential when differentiating between these 2 variants of contact dermatitis. Thus, taken in consideration with clinical contexts, RCM has shown potent diagnostic accuracy and great potential to support the evaluation of ACD alongside patch testing and histopathology.

Final Thoughts

Contact allergy to the mango tree and its components is uncommon. We report a unique case of mango sap–induced ACD evaluated and diagnosed via dynamic visualization under RCM. As a noninvasive and reproducible imaging technique with resolutions comparable to histopathologic analysis, RCM is a promising tool that can be used to support the diagnostic evaluation of ACD.

- Shah KA, Patel MB, Patel RJ, et al. Mangifera indica (mango). Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:42-48.

- Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron toxicity. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 16, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866

- Sareen R, Shah A. Hypersensitivity manifestations to the fruit mango. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:43-49.

- Zakon SJ. Contact dermatitis due to mango. JAMA. 1939;113:1808.

- Astner S, Gonzalez E, Cheung A, et al. Pilot study on the sensitivity and specificity of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:986-992.

- Astner S, Gonzalez S, Gonzalez E. Noninvasive evaluation of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Dermatitis. 2006;17:182-191.

- Csuka EA, Ward SC, Ekelem C, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and multiphoton microscopy in inflammatory skin disease diagnosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2021;53:776-797.

- Guichard A, Fanian F, Girardin P, et al. Allergic patch test and contact dermatitis by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2014;141:805-807.

- Sakanashi EN, Matsumura M, Kikuchi K, et al. A comparative study of allergic contact dermatitis by patch test versus reflectance confocal laser microscopy, with nickel and cobalt. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:705-711.

- Swindells K, Burnett N, Rius-Diaz F, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy may differentiate acute allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:220-228.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels JM, Rabinovitz H, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy: principles, basic terminology, clinical indications, limitations, and practical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1-14.

- Berghea EC, Craiu M, Ali S, et al. Contact allergy induced by mango (Mangifera indica): a relevant topic? Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:1240.

- O’Hern K, Zhang F, Zug KA, et al. “Mango slice” dermatitis: pediatric allergic contact dermatitis to mango pulp and skin. Dermatitis. 2022;33:E46-E47.

- Raison-Peyron N, Aljaber F, Al Ali OA, et al. Mango dermatitis: an unusual cause of eyelid dermatitis in France. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:599-600.

- Alipour Tehrany Y, Coulombe J. Mango allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:241-242.

- Yoo MJ, Carius BM. Mango dermatitis after urushiol sensitization. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:361-363.

- Miyazawa H, Nishie W, Hata H, et al. A severe case of mango dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E160-E161.

- Trehan I, Meuli GJ. Mango contact allergy. J Travel Med. 2010;17:284.

- Wiwanitkit V. Mango dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:158.

- Weinstein S, Bassiri-Tehrani S, Cohen DE. Allergic contact dermatitis to mango flesh. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:195-196.

- Calvert ML, Robertson I, Samaratunga H. Mango dermatitis: allergic contact dermatitis to Mangifera indica. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:59-60.

- Thoo CH, Freeman S. Hypersensitivity reaction to the ingestion of mango flesh. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:116-119.

- Oka K, Saito F, Yasuhara T, et al. A study of cross-reactions between mango contact allergens and urushiol. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:292-296.

- Keil H, Wasserman D, Dawson CR. Mango dermatitis and its relationship to poison ivy hypersensitivity. Ann Allergy. 1946;4: 268-281.

- Maarouf M, Costello CM, Gonzalez S, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: emerging role in noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of eczematous dermatoses. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:626-636.

- Koller S, Gerger A, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of erythematosquamous skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:536-540.

- Shah KA, Patel MB, Patel RJ, et al. Mangifera indica (mango). Pharmacogn Rev. 2010;4:42-48.

- Lofgran T, Mahabal GD. Toxicodendron toxicity. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated May 16, 2023. Accessed September 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557866

- Sareen R, Shah A. Hypersensitivity manifestations to the fruit mango. Asia Pac Allergy. 2011;1:43-49.

- Zakon SJ. Contact dermatitis due to mango. JAMA. 1939;113:1808.

- Astner S, Gonzalez E, Cheung A, et al. Pilot study on the sensitivity and specificity of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:986-992.

- Astner S, Gonzalez S, Gonzalez E. Noninvasive evaluation of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Dermatitis. 2006;17:182-191.

- Csuka EA, Ward SC, Ekelem C, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and multiphoton microscopy in inflammatory skin disease diagnosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2021;53:776-797.

- Guichard A, Fanian F, Girardin P, et al. Allergic patch test and contact dermatitis by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2014;141:805-807.

- Sakanashi EN, Matsumura M, Kikuchi K, et al. A comparative study of allergic contact dermatitis by patch test versus reflectance confocal laser microscopy, with nickel and cobalt. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:705-711.

- Swindells K, Burnett N, Rius-Diaz F, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy may differentiate acute allergic and irritant contact dermatitis in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:220-228.

- Shahriari N, Grant-Kels JM, Rabinovitz H, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy: principles, basic terminology, clinical indications, limitations, and practical considerations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1-14.

- Berghea EC, Craiu M, Ali S, et al. Contact allergy induced by mango (Mangifera indica): a relevant topic? Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:1240.

- O’Hern K, Zhang F, Zug KA, et al. “Mango slice” dermatitis: pediatric allergic contact dermatitis to mango pulp and skin. Dermatitis. 2022;33:E46-E47.

- Raison-Peyron N, Aljaber F, Al Ali OA, et al. Mango dermatitis: an unusual cause of eyelid dermatitis in France. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:599-600.

- Alipour Tehrany Y, Coulombe J. Mango allergic contact dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2021;85:241-242.

- Yoo MJ, Carius BM. Mango dermatitis after urushiol sensitization. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:361-363.

- Miyazawa H, Nishie W, Hata H, et al. A severe case of mango dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E160-E161.

- Trehan I, Meuli GJ. Mango contact allergy. J Travel Med. 2010;17:284.

- Wiwanitkit V. Mango dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:158.

- Weinstein S, Bassiri-Tehrani S, Cohen DE. Allergic contact dermatitis to mango flesh. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:195-196.

- Calvert ML, Robertson I, Samaratunga H. Mango dermatitis: allergic contact dermatitis to Mangifera indica. Australas J Dermatol. 1996;37:59-60.

- Thoo CH, Freeman S. Hypersensitivity reaction to the ingestion of mango flesh. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:116-119.

- Oka K, Saito F, Yasuhara T, et al. A study of cross-reactions between mango contact allergens and urushiol. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:292-296.

- Keil H, Wasserman D, Dawson CR. Mango dermatitis and its relationship to poison ivy hypersensitivity. Ann Allergy. 1946;4: 268-281.

- Maarouf M, Costello CM, Gonzalez S, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy: emerging role in noninvasive diagnosis and monitoring of eczematous dermatoses. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:626-636.

- Koller S, Gerger A, Ahlgrimm-Siess V, et al. In vivo reflectance confocal microscopy of erythematosquamous skin diseases. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:536-540.

Practice Points

- Contact with mango tree sap can induce allergic contact dermatitis.

- Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) is a noninvasive imaging technique that can provide real-time in vivo visualization of affected skin in contact dermatitis.

- Predominant findings of contact dermatitis under RCM include disruption of the stratum corneum; parakeratosis; vesiculation; spongiosis; and exocytosis, vasodilation, and intercellular edema more specific to the allergic subtype.

Erythema Nodosum Triggered by a Bite From a Copperhead Snake

The clinical manifestations of snakebites vary based on the species of snake, bite location, and amount and strength of the venom injected. Locally acting toxins in snake venom predominantly consist of enzymes, such as phospholipase A2, that cause local tissue destruction and can result in pain, swelling, blistering, ecchymosis, and tissue necrosis at the site of the bite within hours to days after the bite.1 Systemically acting toxins can target a wide variety of tissues and cause severe systemic complications including paralysis, rhabdomyolysis secondary to muscle damage, coagulopathy, sepsis, and cardiorespiratory failure.2

Although pain and swelling following snakebites typically resolve by 1 month after envenomation, copperhead snakes—a type of pit viper—may cause residual symptoms of pain and swelling lasting for a year or more.3 Additional cutaneous manifestations of copperhead snakebites include wound infections at the bite site, such as cellulitis and necrotizing fasciitis. More devastating complications that have been described following snake envenomation include tissue injury of an entire extremity and development of compartment syndrome, which requires urgent fasciotomy to prevent potential loss of the affected limb.4

Physicians should be aware of the potential complications of snakebites to properly manage and counsel their patients. We describe a 42-year-old woman with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules persisting for 4 months following a copperhead snakebite. A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of snakebite-associated erythema nodosum (EN).

Case Report

A 42-year-old woman presented to our clinic with progressive tender, pruritic, deep-seated, erythematous nodules in multiple locations on the legs after sustaining a bite by a copperhead snake on the left foot 4 months prior. The lesions tended to fluctuate in intensity. In the days following the bite, she initially developed painful red bumps on the left foot just proximal to the bite site with associated pain and swelling extending up to just below the left knee. She reported no other notable symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, fatigue, or gastrointestinal tract symptoms. Physical examination revealed bilateral pitting edema, which was worse in the left leg, along with multiple deep, palpable, tender subcutaneous nodules with erythematous surface change (Figure 1).

Workup performed by an outside provider over the previous month included 2 venous duplex ultrasounds of the left leg, which showed no signs of deep vein thrombosis. Additionally, the patient underwent lateral and anteroposterior radiographs of the left foot, tibia, and fibula, which showed no evidence of fracture.

Given the morphology and distribution of the lesions (Figure 2), EN was strongly favored as the cause of the symptoms, and a biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. All immunohistochemical stains including auramine-rhodamine for acid-fast bacilli, Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver for fungal organisms, and Brown and Brenn were negative. Given the waxing and waning course of the lesions, which suggested an active neutrophilic rather than purely chronic granulomatous phase of EN, the patient was treated with colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily for 1 month.

Causes of EN and Clinical Manifestations

Erythema nodosum is a common form of septal panniculitis that can be precipitated by inflammatory conditions, infection, or medications (commonly oral contraceptive pills) but often is idiopathic.5 The acute phase is neutrophilic, with evolution over time to a granulomatous phase. Common etiologies include sarcoidosis; inflammatory bowel disease; and bacterial or fungal infections such as Streptococcus (especially common in children), histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis. The patient was otherwise healthy and was not taking any medications that are known triggers of EN. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE in the English-language literature using the terms copperhead snake bite, erythema nodosum snake, and copperhead snake erythema nodosum revealed no reports of EN following a bite from a copperhead snake; however, in one case, an adder bite led to erysipelas, likely due to disturbed blood and lymphatic flow, which then triggered EN.6 Additionally, EN has been reported as a delayed reaction to jellyfish stings.7

Clinical features of EN include the development of tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules and plaques most frequently over the pretibial region. Lesions typically evolve from raised, deep-seated nodules into flat indurated plaques over a span of weeks. Occasionally, there is a slight prodromal phase marked by nonspecific symptoms such as fever and arthralgia lasting for 3 to 6 days. Erythema nodosum typically results in spontaneous resolution after 4 to 8 weeks, and management involves treatment of any underlying condition with symptomatic care. Interestingly, our patient experienced persistent symptoms over the course of 4 months, with development of new nodular lesions throughout this time period. The most frequently used drugs for the management of symptomatic EN include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, and potassium iodide.8 A characteristic histologic finding of the granulomatous phase is the Miescher radial granuloma, which is a septal collection of histiocytes surrounding a cleft.9

Snakebite Reactions