User login

Daily Ebola update: 50 monitored; 9 high risk

It’s been 5 days since a 42-year old Liberian man became the first patient to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States, and the main message that health officials stress daily is this: take the travel history and communicate it with your staff.

The travel history for Ebola is very specific and currently is limited to Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria.

“We’ve produced checklists and flowcharts and we encourage hospitals to use them,” said Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a news conference Oct. 4.

Public health officials have so far assessed 114 individuals in Texas who may have had contact with the patient, Thomas Eric Duncan. They have ruled out about half of them, and are now monitoring 50 individuals, 9 of whom had definite contact with Mr. Duncan.

Among the 9 are 4 individuals who were in the same apartment as Mr. Duncan. On Friday, they were moved to an undisclosed location provided by a member of their faith community, Texas officials said.

All 50 individuals will be monitored for 21 days since the day they potentially came in contact with Mr. Duncan after he became ill and infectious. No one has reported a fever so far. Mr. Duncan remains in serious condition.

Dr. Frieden said that tracing those who may have had contact with Mr. Duncan, monitoring them, and isolating them if they become symptomatic are the core of public health practice and that’s “why we’re confident that we’ll stop this in its tracks in Texas.”

Questions, however, remain as to why Mr. Duncan was initially sent home from his first visit to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital’s emergency department.

Hospital officials added to the confusion late on Oct. 3, when they retracted an earlier statement, which had pointed to a flaw in the electronic health records as the culprit.

In a clarification, officials said, “As a standard part of the nursing process, the patient’s travel history was documented and available to the full care team in the electronic health record (EHR), including within the physician’s workflow. There was no flaw in the EHR in the way the physician and nursing portions interacted related to this event.”

Officials didn’t provide an explanation for the change in the hospital’s statement and said that the broader point is communicating the travel history with all staff.

CDC has received more than 100 Ebola-related inquiries so far and all the specimen have been negative except for Mr. Duncan’s case.

“We expect more rumors about possible cases, but until there’s a positive result, they are just rumors and concerns,” Dr. Frieden said. More than a dozen laboratories around the nation are equipped to conduct high quality testing for Ebola. The test takes a few hours, but with the added shipping time, the process can take up to 24 hours.

Meanwhile, trained CDC staff are screening individuals who are boarding planes from the affected countries and so far 77 people have been prevented from boarding the plane although it’s not clear if they had Ebola.

There are also quarantine stations at all major U.S. airport, but no suspected Ebola cases have been referred to them so far, Dr. Frieden said.

“We’re all connected,” he said. “And we’re not going to get to zero risk until we can control the outbreak in Africa. It’s going to be a long, hard road.”

nmiller@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @naseemmiller

It’s been 5 days since a 42-year old Liberian man became the first patient to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States, and the main message that health officials stress daily is this: take the travel history and communicate it with your staff.

The travel history for Ebola is very specific and currently is limited to Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria.

“We’ve produced checklists and flowcharts and we encourage hospitals to use them,” said Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a news conference Oct. 4.

Public health officials have so far assessed 114 individuals in Texas who may have had contact with the patient, Thomas Eric Duncan. They have ruled out about half of them, and are now monitoring 50 individuals, 9 of whom had definite contact with Mr. Duncan.

Among the 9 are 4 individuals who were in the same apartment as Mr. Duncan. On Friday, they were moved to an undisclosed location provided by a member of their faith community, Texas officials said.

All 50 individuals will be monitored for 21 days since the day they potentially came in contact with Mr. Duncan after he became ill and infectious. No one has reported a fever so far. Mr. Duncan remains in serious condition.

Dr. Frieden said that tracing those who may have had contact with Mr. Duncan, monitoring them, and isolating them if they become symptomatic are the core of public health practice and that’s “why we’re confident that we’ll stop this in its tracks in Texas.”

Questions, however, remain as to why Mr. Duncan was initially sent home from his first visit to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital’s emergency department.

Hospital officials added to the confusion late on Oct. 3, when they retracted an earlier statement, which had pointed to a flaw in the electronic health records as the culprit.

In a clarification, officials said, “As a standard part of the nursing process, the patient’s travel history was documented and available to the full care team in the electronic health record (EHR), including within the physician’s workflow. There was no flaw in the EHR in the way the physician and nursing portions interacted related to this event.”

Officials didn’t provide an explanation for the change in the hospital’s statement and said that the broader point is communicating the travel history with all staff.

CDC has received more than 100 Ebola-related inquiries so far and all the specimen have been negative except for Mr. Duncan’s case.

“We expect more rumors about possible cases, but until there’s a positive result, they are just rumors and concerns,” Dr. Frieden said. More than a dozen laboratories around the nation are equipped to conduct high quality testing for Ebola. The test takes a few hours, but with the added shipping time, the process can take up to 24 hours.

Meanwhile, trained CDC staff are screening individuals who are boarding planes from the affected countries and so far 77 people have been prevented from boarding the plane although it’s not clear if they had Ebola.

There are also quarantine stations at all major U.S. airport, but no suspected Ebola cases have been referred to them so far, Dr. Frieden said.

“We’re all connected,” he said. “And we’re not going to get to zero risk until we can control the outbreak in Africa. It’s going to be a long, hard road.”

nmiller@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @naseemmiller

It’s been 5 days since a 42-year old Liberian man became the first patient to be diagnosed with Ebola in the United States, and the main message that health officials stress daily is this: take the travel history and communicate it with your staff.

The travel history for Ebola is very specific and currently is limited to Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria.

“We’ve produced checklists and flowcharts and we encourage hospitals to use them,” said Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in a news conference Oct. 4.

Public health officials have so far assessed 114 individuals in Texas who may have had contact with the patient, Thomas Eric Duncan. They have ruled out about half of them, and are now monitoring 50 individuals, 9 of whom had definite contact with Mr. Duncan.

Among the 9 are 4 individuals who were in the same apartment as Mr. Duncan. On Friday, they were moved to an undisclosed location provided by a member of their faith community, Texas officials said.

All 50 individuals will be monitored for 21 days since the day they potentially came in contact with Mr. Duncan after he became ill and infectious. No one has reported a fever so far. Mr. Duncan remains in serious condition.

Dr. Frieden said that tracing those who may have had contact with Mr. Duncan, monitoring them, and isolating them if they become symptomatic are the core of public health practice and that’s “why we’re confident that we’ll stop this in its tracks in Texas.”

Questions, however, remain as to why Mr. Duncan was initially sent home from his first visit to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital’s emergency department.

Hospital officials added to the confusion late on Oct. 3, when they retracted an earlier statement, which had pointed to a flaw in the electronic health records as the culprit.

In a clarification, officials said, “As a standard part of the nursing process, the patient’s travel history was documented and available to the full care team in the electronic health record (EHR), including within the physician’s workflow. There was no flaw in the EHR in the way the physician and nursing portions interacted related to this event.”

Officials didn’t provide an explanation for the change in the hospital’s statement and said that the broader point is communicating the travel history with all staff.

CDC has received more than 100 Ebola-related inquiries so far and all the specimen have been negative except for Mr. Duncan’s case.

“We expect more rumors about possible cases, but until there’s a positive result, they are just rumors and concerns,” Dr. Frieden said. More than a dozen laboratories around the nation are equipped to conduct high quality testing for Ebola. The test takes a few hours, but with the added shipping time, the process can take up to 24 hours.

Meanwhile, trained CDC staff are screening individuals who are boarding planes from the affected countries and so far 77 people have been prevented from boarding the plane although it’s not clear if they had Ebola.

There are also quarantine stations at all major U.S. airport, but no suspected Ebola cases have been referred to them so far, Dr. Frieden said.

“We’re all connected,” he said. “And we’re not going to get to zero risk until we can control the outbreak in Africa. It’s going to be a long, hard road.”

nmiller@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @naseemmiller

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

Daily Ebola Update: 50 people followed daily; 10 high risk

After casting a wide net to assess 100 people who may have come in contact with the man who has Ebola, federal and Texas state officials have narrowed down the number to 50 people, 10 of whom are considered high risk, including the patient’s four family members who are quarantined in their apartment.

The patient, 42-year-old Thomas Eric Duncan, remains in serious but stable condition. Among the 50 are a number of at-risk hospital workers and staff. All individuals are doing well and have reported no symptoms so far, Texas health officials reported during an afternoon news conference Oct. 3.

Late in the day on Oct. 2, CDC issued an updated advisory for health care professionals on evaluating patients for Ebola, asking them to increase their vigilance in taking travel history; to isolate patients who fit the precautionary criteria for Ebola; and to immediately notify local and state health departments.

“We’ve been redoubling out efforts to sensitize health care providers on how to correctly identify and safely deal with Ebola patients,” said Dr. Beth P. Bell, director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Meanwhile, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, which initially sent Mr. Duncan home with antibiotics, released more details about that encounter.

In an Oct. 2 statement, the hospital noted that physician and nursing workflows were separate in the electronic health records, such that “the travel history would not automatically appear in the physician’s standard workflow.”

On his first visit to the emergency department, Mr. Duncan presented with a temperature of 100.1° F, abdominal pain for 2 days, a sharp headache, and decreased urination, although no symptoms were severe, the hospital reported. He reported no nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Mr. Duncan also said that he had not been around any sick individuals and that he had been in Africa.

The hospital said that the travel history documentation has now been relocated “to a portion of the EHR that is part of both [nursing and physician] workflows. It also has been modified to specifically reference Ebola-endemic regions in Africa.”

Dr. Kristi L. Koenig, director of Center for Disaster Medical Sciences at University of California, Irvine, said that its important for physicians to be aware of infectious diseases worldwide. She urged her peers to be up to date and pay attention to credible authorities, so that they can rapidly identify and isolate potentially infected patients.

"You have to be prepared regardless of health care setting," Dr. Koenig, a national spokesperson for the American College of Emergency Physicians, said in an interview.

In a paper, Dr. Koenig and colleagues list several actions that emergency physicians should take when treating febrile travelers and remind their peers that several factors, including the globalization of health care, climate change, and rapid international travel "means that microbial threat to the population have increased."

The number of Ebola cases in West Africa continues to grow, according to the latest information from the World Health Organization. A total of 7,470 confirmed cases and 3,431 deaths have been reported in in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, according to the World Health Organization.

Dr. Bell of the CDC said that a couple of Ebola vaccines are in early phases of human trials. “We’re working very hard to accelerate this, but we need to be sure that the vaccines are safe and effective. But this is a very high priority for us.”

Helpful Links:

Information for health-care workers

Latest outbreak information in West Africa

World Health Organization Ebola page

Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy

American College of Emergency Physicians

On Twitter @naseemmiller

After casting a wide net to assess 100 people who may have come in contact with the man who has Ebola, federal and Texas state officials have narrowed down the number to 50 people, 10 of whom are considered high risk, including the patient’s four family members who are quarantined in their apartment.

The patient, 42-year-old Thomas Eric Duncan, remains in serious but stable condition. Among the 50 are a number of at-risk hospital workers and staff. All individuals are doing well and have reported no symptoms so far, Texas health officials reported during an afternoon news conference Oct. 3.

Late in the day on Oct. 2, CDC issued an updated advisory for health care professionals on evaluating patients for Ebola, asking them to increase their vigilance in taking travel history; to isolate patients who fit the precautionary criteria for Ebola; and to immediately notify local and state health departments.

“We’ve been redoubling out efforts to sensitize health care providers on how to correctly identify and safely deal with Ebola patients,” said Dr. Beth P. Bell, director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Meanwhile, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, which initially sent Mr. Duncan home with antibiotics, released more details about that encounter.

In an Oct. 2 statement, the hospital noted that physician and nursing workflows were separate in the electronic health records, such that “the travel history would not automatically appear in the physician’s standard workflow.”

On his first visit to the emergency department, Mr. Duncan presented with a temperature of 100.1° F, abdominal pain for 2 days, a sharp headache, and decreased urination, although no symptoms were severe, the hospital reported. He reported no nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Mr. Duncan also said that he had not been around any sick individuals and that he had been in Africa.

The hospital said that the travel history documentation has now been relocated “to a portion of the EHR that is part of both [nursing and physician] workflows. It also has been modified to specifically reference Ebola-endemic regions in Africa.”

Dr. Kristi L. Koenig, director of Center for Disaster Medical Sciences at University of California, Irvine, said that its important for physicians to be aware of infectious diseases worldwide. She urged her peers to be up to date and pay attention to credible authorities, so that they can rapidly identify and isolate potentially infected patients.

"You have to be prepared regardless of health care setting," Dr. Koenig, a national spokesperson for the American College of Emergency Physicians, said in an interview.

In a paper, Dr. Koenig and colleagues list several actions that emergency physicians should take when treating febrile travelers and remind their peers that several factors, including the globalization of health care, climate change, and rapid international travel "means that microbial threat to the population have increased."

The number of Ebola cases in West Africa continues to grow, according to the latest information from the World Health Organization. A total of 7,470 confirmed cases and 3,431 deaths have been reported in in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, according to the World Health Organization.

Dr. Bell of the CDC said that a couple of Ebola vaccines are in early phases of human trials. “We’re working very hard to accelerate this, but we need to be sure that the vaccines are safe and effective. But this is a very high priority for us.”

Helpful Links:

Information for health-care workers

Latest outbreak information in West Africa

World Health Organization Ebola page

Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy

American College of Emergency Physicians

On Twitter @naseemmiller

After casting a wide net to assess 100 people who may have come in contact with the man who has Ebola, federal and Texas state officials have narrowed down the number to 50 people, 10 of whom are considered high risk, including the patient’s four family members who are quarantined in their apartment.

The patient, 42-year-old Thomas Eric Duncan, remains in serious but stable condition. Among the 50 are a number of at-risk hospital workers and staff. All individuals are doing well and have reported no symptoms so far, Texas health officials reported during an afternoon news conference Oct. 3.

Late in the day on Oct. 2, CDC issued an updated advisory for health care professionals on evaluating patients for Ebola, asking them to increase their vigilance in taking travel history; to isolate patients who fit the precautionary criteria for Ebola; and to immediately notify local and state health departments.

“We’ve been redoubling out efforts to sensitize health care providers on how to correctly identify and safely deal with Ebola patients,” said Dr. Beth P. Bell, director of the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Meanwhile, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, which initially sent Mr. Duncan home with antibiotics, released more details about that encounter.

In an Oct. 2 statement, the hospital noted that physician and nursing workflows were separate in the electronic health records, such that “the travel history would not automatically appear in the physician’s standard workflow.”

On his first visit to the emergency department, Mr. Duncan presented with a temperature of 100.1° F, abdominal pain for 2 days, a sharp headache, and decreased urination, although no symptoms were severe, the hospital reported. He reported no nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Mr. Duncan also said that he had not been around any sick individuals and that he had been in Africa.

The hospital said that the travel history documentation has now been relocated “to a portion of the EHR that is part of both [nursing and physician] workflows. It also has been modified to specifically reference Ebola-endemic regions in Africa.”

Dr. Kristi L. Koenig, director of Center for Disaster Medical Sciences at University of California, Irvine, said that its important for physicians to be aware of infectious diseases worldwide. She urged her peers to be up to date and pay attention to credible authorities, so that they can rapidly identify and isolate potentially infected patients.

"You have to be prepared regardless of health care setting," Dr. Koenig, a national spokesperson for the American College of Emergency Physicians, said in an interview.

In a paper, Dr. Koenig and colleagues list several actions that emergency physicians should take when treating febrile travelers and remind their peers that several factors, including the globalization of health care, climate change, and rapid international travel "means that microbial threat to the population have increased."

The number of Ebola cases in West Africa continues to grow, according to the latest information from the World Health Organization. A total of 7,470 confirmed cases and 3,431 deaths have been reported in in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, according to the World Health Organization.

Dr. Bell of the CDC said that a couple of Ebola vaccines are in early phases of human trials. “We’re working very hard to accelerate this, but we need to be sure that the vaccines are safe and effective. But this is a very high priority for us.”

Helpful Links:

Information for health-care workers

Latest outbreak information in West Africa

World Health Organization Ebola page

Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy

American College of Emergency Physicians

On Twitter @naseemmiller

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

IHS Hiring More Veterans

The IHS has launched a Veterans Hiring Initiative with the goal of increasing veteran new hires from 6% to 9% over the next 2 years for an overall boost of 50%.

In addition to developing a public service announcement campaign, IHS is collaborating with other agencies to promote the effort. One partnership will be with the VA to sponsor federal recruitment events aimed at veterans. IHS will also partner with DoD to recruit separating active-duty service members through the Transition Assistance Program and marketing and media outreach campaigns. Finally, IHS will work with tribes in outreach efforts targeting tribal members who are active-duty or veterans.

IHS will be interviewing veterans who have successfully transitioned from the military to the IHS or tribal positions and will post those stories on the IHS and partners’ websites.

The IHS has launched a Veterans Hiring Initiative with the goal of increasing veteran new hires from 6% to 9% over the next 2 years for an overall boost of 50%.

In addition to developing a public service announcement campaign, IHS is collaborating with other agencies to promote the effort. One partnership will be with the VA to sponsor federal recruitment events aimed at veterans. IHS will also partner with DoD to recruit separating active-duty service members through the Transition Assistance Program and marketing and media outreach campaigns. Finally, IHS will work with tribes in outreach efforts targeting tribal members who are active-duty or veterans.

IHS will be interviewing veterans who have successfully transitioned from the military to the IHS or tribal positions and will post those stories on the IHS and partners’ websites.

The IHS has launched a Veterans Hiring Initiative with the goal of increasing veteran new hires from 6% to 9% over the next 2 years for an overall boost of 50%.

In addition to developing a public service announcement campaign, IHS is collaborating with other agencies to promote the effort. One partnership will be with the VA to sponsor federal recruitment events aimed at veterans. IHS will also partner with DoD to recruit separating active-duty service members through the Transition Assistance Program and marketing and media outreach campaigns. Finally, IHS will work with tribes in outreach efforts targeting tribal members who are active-duty or veterans.

IHS will be interviewing veterans who have successfully transitioned from the military to the IHS or tribal positions and will post those stories on the IHS and partners’ websites.

Daily Ebola update: 100 assessed; 4 quarantined

Since Sept. 29, when a man in Texas tested positive for Ebola, federal and state officials have identified more than 100 people who may have come in direct or indirect contact with him. They are being monitored for fever, and four individuals are quarantined for 21 days in an apartment for a more controlled monitoring. None have symptoms so far.

“We remain confident that we can contain the spread of Ebola in the U.S.,” Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said during a press briefing. “There could be additional cases, and if that occurs, there are systems in place to prevent the spread.”

The sick man, who has been identified in the media as Thomas Eric Duncan, first visited the emergency department at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Sept. 26, a week after he left Liberia. He was sent home, only to be brought back 2 days later by an ambulance. He is still in serious condition and remains the only case of Ebola to be diagnosed in the United States.

Texas officials said they are investigating why he was sent home at his first visit.

“The lesson from all of this for the hospitals across the nation is that they really have to take the travel history,” Dr. Frieden said. “Ask if they’ve been in these areas where there’s Ebola, and if so, they have to put Ebola on the differential diagnosis.” He stressed the importance of hospitals working and collaborating with public health officials.

“Any hospital in the country can safely take care of Ebola patients,” he said, as long as they have a room with its own bathroom. “But you need rigorous, meticulous training, and you need to make sure that the care is done well.”

There are currently 12 laboratories around the nation prepared to test for the Ebola virus, according to officials. As of Oct. 2, there have been 100 inquiries from hospitals in 34 states about the possibility of having a patient infected with Ebola. So far 15 cases have been tested for Ebola, and the only positive case so far is the man in Texas.

Staff trained by the CDC took the Texas patient’s temperature when he was boarding the plane in Liberia, which is the current protocol, and his temperature was 97.3° F, officials said. The status of his exposure in Liberia is now being investigated.

“The broader issue is, can we make the risk zero,” Dr. Frieden said. “And the bottom line, the plain truth, is that we can’t make the risk zero until the outbreak is controlled in West Africa.” Until then, officials will do what they can to minimize the risk of spread, he said. “It’s not impossible that we’ll have other individuals coming to the country that have Ebola.”

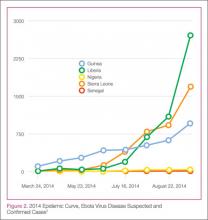

Based on the most recent data, there have been more than 6,500 cases of Ebola in West Africa, and more than 3,000 of those patients have died. Liberia has had the highest number of Ebola cases, followed by Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria. There has been one travel-reported case in Senegal.

Whether the affected countries should be isolated is a tough question, Dr. Frieden said, because isolating the countries will make it more difficult to deliver help, which in turn will enable the disease to spread more widely.

“The best way is not to seal off those countries, but to provide the services needed” and identify any [infected] individual who may be leaving those countries.

Ebola outbreaks have been recorded since 1976, but none has been as large as the current epidemic in West Africa, which was first identified on March 23 as an outbreak in Guinea.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on Sept. 23, the World Health Organization Ebola Response Team predicted that by Nov. 2, 2014, the cumulative reported numbers of confirmed and probable cases in the affected West African countries will exceed 20,000 in total.

“These data indicate that without drastic improvements in control measures, the numbers of cases of and deaths from [Ebola virus disease] are expected to continue increasing from hundreds to thousands per week in the coming months,” the team wrote.

Helpful links

Hospital checklist: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/hospital-checklist-ebola-preparedness.pdf

Information for health care workers: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/index.html

Latest outbreak information in West Africa:

http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/index.html

History of Ebola outbreaks: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/distribution-map.html

On Twitter @naseemmiller

Since Sept. 29, when a man in Texas tested positive for Ebola, federal and state officials have identified more than 100 people who may have come in direct or indirect contact with him. They are being monitored for fever, and four individuals are quarantined for 21 days in an apartment for a more controlled monitoring. None have symptoms so far.

“We remain confident that we can contain the spread of Ebola in the U.S.,” Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said during a press briefing. “There could be additional cases, and if that occurs, there are systems in place to prevent the spread.”

The sick man, who has been identified in the media as Thomas Eric Duncan, first visited the emergency department at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Sept. 26, a week after he left Liberia. He was sent home, only to be brought back 2 days later by an ambulance. He is still in serious condition and remains the only case of Ebola to be diagnosed in the United States.

Texas officials said they are investigating why he was sent home at his first visit.

“The lesson from all of this for the hospitals across the nation is that they really have to take the travel history,” Dr. Frieden said. “Ask if they’ve been in these areas where there’s Ebola, and if so, they have to put Ebola on the differential diagnosis.” He stressed the importance of hospitals working and collaborating with public health officials.

“Any hospital in the country can safely take care of Ebola patients,” he said, as long as they have a room with its own bathroom. “But you need rigorous, meticulous training, and you need to make sure that the care is done well.”

There are currently 12 laboratories around the nation prepared to test for the Ebola virus, according to officials. As of Oct. 2, there have been 100 inquiries from hospitals in 34 states about the possibility of having a patient infected with Ebola. So far 15 cases have been tested for Ebola, and the only positive case so far is the man in Texas.

Staff trained by the CDC took the Texas patient’s temperature when he was boarding the plane in Liberia, which is the current protocol, and his temperature was 97.3° F, officials said. The status of his exposure in Liberia is now being investigated.

“The broader issue is, can we make the risk zero,” Dr. Frieden said. “And the bottom line, the plain truth, is that we can’t make the risk zero until the outbreak is controlled in West Africa.” Until then, officials will do what they can to minimize the risk of spread, he said. “It’s not impossible that we’ll have other individuals coming to the country that have Ebola.”

Based on the most recent data, there have been more than 6,500 cases of Ebola in West Africa, and more than 3,000 of those patients have died. Liberia has had the highest number of Ebola cases, followed by Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria. There has been one travel-reported case in Senegal.

Whether the affected countries should be isolated is a tough question, Dr. Frieden said, because isolating the countries will make it more difficult to deliver help, which in turn will enable the disease to spread more widely.

“The best way is not to seal off those countries, but to provide the services needed” and identify any [infected] individual who may be leaving those countries.

Ebola outbreaks have been recorded since 1976, but none has been as large as the current epidemic in West Africa, which was first identified on March 23 as an outbreak in Guinea.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on Sept. 23, the World Health Organization Ebola Response Team predicted that by Nov. 2, 2014, the cumulative reported numbers of confirmed and probable cases in the affected West African countries will exceed 20,000 in total.

“These data indicate that without drastic improvements in control measures, the numbers of cases of and deaths from [Ebola virus disease] are expected to continue increasing from hundreds to thousands per week in the coming months,” the team wrote.

Helpful links

Hospital checklist: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/hospital-checklist-ebola-preparedness.pdf

Information for health care workers: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/index.html

Latest outbreak information in West Africa:

http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/index.html

History of Ebola outbreaks: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/distribution-map.html

On Twitter @naseemmiller

Since Sept. 29, when a man in Texas tested positive for Ebola, federal and state officials have identified more than 100 people who may have come in direct or indirect contact with him. They are being monitored for fever, and four individuals are quarantined for 21 days in an apartment for a more controlled monitoring. None have symptoms so far.

“We remain confident that we can contain the spread of Ebola in the U.S.,” Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said during a press briefing. “There could be additional cases, and if that occurs, there are systems in place to prevent the spread.”

The sick man, who has been identified in the media as Thomas Eric Duncan, first visited the emergency department at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Sept. 26, a week after he left Liberia. He was sent home, only to be brought back 2 days later by an ambulance. He is still in serious condition and remains the only case of Ebola to be diagnosed in the United States.

Texas officials said they are investigating why he was sent home at his first visit.

“The lesson from all of this for the hospitals across the nation is that they really have to take the travel history,” Dr. Frieden said. “Ask if they’ve been in these areas where there’s Ebola, and if so, they have to put Ebola on the differential diagnosis.” He stressed the importance of hospitals working and collaborating with public health officials.

“Any hospital in the country can safely take care of Ebola patients,” he said, as long as they have a room with its own bathroom. “But you need rigorous, meticulous training, and you need to make sure that the care is done well.”

There are currently 12 laboratories around the nation prepared to test for the Ebola virus, according to officials. As of Oct. 2, there have been 100 inquiries from hospitals in 34 states about the possibility of having a patient infected with Ebola. So far 15 cases have been tested for Ebola, and the only positive case so far is the man in Texas.

Staff trained by the CDC took the Texas patient’s temperature when he was boarding the plane in Liberia, which is the current protocol, and his temperature was 97.3° F, officials said. The status of his exposure in Liberia is now being investigated.

“The broader issue is, can we make the risk zero,” Dr. Frieden said. “And the bottom line, the plain truth, is that we can’t make the risk zero until the outbreak is controlled in West Africa.” Until then, officials will do what they can to minimize the risk of spread, he said. “It’s not impossible that we’ll have other individuals coming to the country that have Ebola.”

Based on the most recent data, there have been more than 6,500 cases of Ebola in West Africa, and more than 3,000 of those patients have died. Liberia has had the highest number of Ebola cases, followed by Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Nigeria. There has been one travel-reported case in Senegal.

Whether the affected countries should be isolated is a tough question, Dr. Frieden said, because isolating the countries will make it more difficult to deliver help, which in turn will enable the disease to spread more widely.

“The best way is not to seal off those countries, but to provide the services needed” and identify any [infected] individual who may be leaving those countries.

Ebola outbreaks have been recorded since 1976, but none has been as large as the current epidemic in West Africa, which was first identified on March 23 as an outbreak in Guinea.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine on Sept. 23, the World Health Organization Ebola Response Team predicted that by Nov. 2, 2014, the cumulative reported numbers of confirmed and probable cases in the affected West African countries will exceed 20,000 in total.

“These data indicate that without drastic improvements in control measures, the numbers of cases of and deaths from [Ebola virus disease] are expected to continue increasing from hundreds to thousands per week in the coming months,” the team wrote.

Helpful links

Hospital checklist: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/hospital-checklist-ebola-preparedness.pdf

Information for health care workers: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/hcp/index.html

Latest outbreak information in West Africa:

http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/index.html

History of Ebola outbreaks: http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/history/distribution-map.html

On Twitter @naseemmiller

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

FDA finalizes medical device cybersecurity guidance

The Food and Drug Administration is calling on device manufacturers that have network-connected devices to consider cybersecurity risks as part of product design.

The agency finalized guidance recommending that manufacturers submit documentation to the FDA about identified risks and the controls in place to mitigate the risks, as well as about how manufacturers plan to update software as risks are discovered.

“There is no such thing as a threat-proof medical device,” Suzanne Schwartz, director of emergency preparedness/operations and medical countermeasures at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement. “It is important for medical device manufacturers to remain vigilant about cybersecurity and to appropriately protect patients from those risks.”

While directed at manufacturers, the guidance notes that medical device security “is a shared responsibility” across all stakeholders, including health care facilities, physicians, patients, and manufacturers.

FDA will host a 2-day workshop on Oct. 21-22, 2014, to discuss the guidance and collaborative approaches to medical device cybersecurity.

The Food and Drug Administration is calling on device manufacturers that have network-connected devices to consider cybersecurity risks as part of product design.

The agency finalized guidance recommending that manufacturers submit documentation to the FDA about identified risks and the controls in place to mitigate the risks, as well as about how manufacturers plan to update software as risks are discovered.

“There is no such thing as a threat-proof medical device,” Suzanne Schwartz, director of emergency preparedness/operations and medical countermeasures at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement. “It is important for medical device manufacturers to remain vigilant about cybersecurity and to appropriately protect patients from those risks.”

While directed at manufacturers, the guidance notes that medical device security “is a shared responsibility” across all stakeholders, including health care facilities, physicians, patients, and manufacturers.

FDA will host a 2-day workshop on Oct. 21-22, 2014, to discuss the guidance and collaborative approaches to medical device cybersecurity.

The Food and Drug Administration is calling on device manufacturers that have network-connected devices to consider cybersecurity risks as part of product design.

The agency finalized guidance recommending that manufacturers submit documentation to the FDA about identified risks and the controls in place to mitigate the risks, as well as about how manufacturers plan to update software as risks are discovered.

“There is no such thing as a threat-proof medical device,” Suzanne Schwartz, director of emergency preparedness/operations and medical countermeasures at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement. “It is important for medical device manufacturers to remain vigilant about cybersecurity and to appropriately protect patients from those risks.”

While directed at manufacturers, the guidance notes that medical device security “is a shared responsibility” across all stakeholders, including health care facilities, physicians, patients, and manufacturers.

FDA will host a 2-day workshop on Oct. 21-22, 2014, to discuss the guidance and collaborative approaches to medical device cybersecurity.

Opioid-poisoning deaths rose fastest in 55- to 64-year-olds

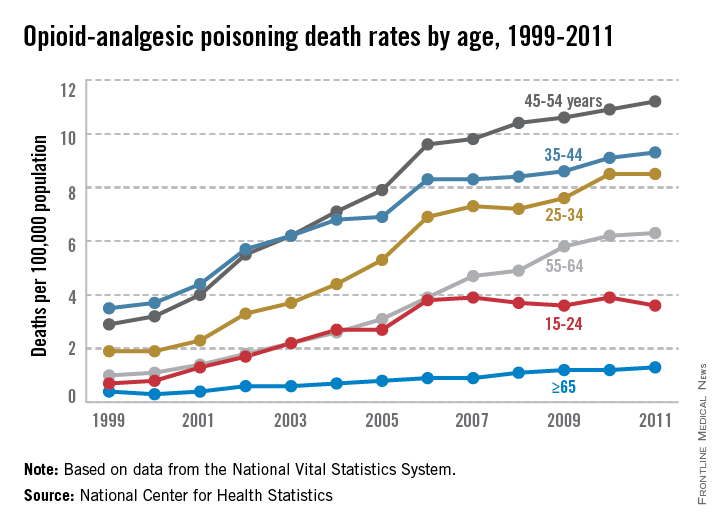

People aged 45-54 years had the highest rate of opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths in the United States in 2011, while people aged 55-64 years experienced the largest rise in deaths from opioid analgesics from 1999 to 2011, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 1999, the death rate for opioid analgesics was 1 per 100,000 people for adults aged 55-64 years. By 2011, this rate had increased to 6.3 per 100,000 people. This was the fourth-highest rate overall among reported age groups, with adults aged 45-54, 35-44, and 25-34 having higher rates, and people aged 15-24 and 65 and older having lower rates. The rate of increase slowed for all groups after 2006, except for people aged 15-24, whose death rate from opioid analgesics did not change significantly from 2006 to 2011, the NCHS reported.

Non-Hispanic white adults had the largest increase in the rate of opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths among measured ethnicities, rising from 1.6 per 100,000 in 1999 to 7.3 in 2011. The death rate for non-Hispanic black adults increased from 0.9 per 100,000 in 1999 to 2.3 in 2011. Hispanic adults did not see a large rate increase, with 1.7 per 100,000 deaths in 1999 and 2 per 100,000 deaths in 2011 attributed to opioid-analgesic poisoning, according to data from the National Vital Statistics System.

People aged 45-54 years had the highest rate of opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths in the United States in 2011, while people aged 55-64 years experienced the largest rise in deaths from opioid analgesics from 1999 to 2011, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 1999, the death rate for opioid analgesics was 1 per 100,000 people for adults aged 55-64 years. By 2011, this rate had increased to 6.3 per 100,000 people. This was the fourth-highest rate overall among reported age groups, with adults aged 45-54, 35-44, and 25-34 having higher rates, and people aged 15-24 and 65 and older having lower rates. The rate of increase slowed for all groups after 2006, except for people aged 15-24, whose death rate from opioid analgesics did not change significantly from 2006 to 2011, the NCHS reported.

Non-Hispanic white adults had the largest increase in the rate of opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths among measured ethnicities, rising from 1.6 per 100,000 in 1999 to 7.3 in 2011. The death rate for non-Hispanic black adults increased from 0.9 per 100,000 in 1999 to 2.3 in 2011. Hispanic adults did not see a large rate increase, with 1.7 per 100,000 deaths in 1999 and 2 per 100,000 deaths in 2011 attributed to opioid-analgesic poisoning, according to data from the National Vital Statistics System.

People aged 45-54 years had the highest rate of opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths in the United States in 2011, while people aged 55-64 years experienced the largest rise in deaths from opioid analgesics from 1999 to 2011, according to a report from the National Center for Health Statistics.

In 1999, the death rate for opioid analgesics was 1 per 100,000 people for adults aged 55-64 years. By 2011, this rate had increased to 6.3 per 100,000 people. This was the fourth-highest rate overall among reported age groups, with adults aged 45-54, 35-44, and 25-34 having higher rates, and people aged 15-24 and 65 and older having lower rates. The rate of increase slowed for all groups after 2006, except for people aged 15-24, whose death rate from opioid analgesics did not change significantly from 2006 to 2011, the NCHS reported.

Non-Hispanic white adults had the largest increase in the rate of opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths among measured ethnicities, rising from 1.6 per 100,000 in 1999 to 7.3 in 2011. The death rate for non-Hispanic black adults increased from 0.9 per 100,000 in 1999 to 2.3 in 2011. Hispanic adults did not see a large rate increase, with 1.7 per 100,000 deaths in 1999 and 2 per 100,000 deaths in 2011 attributed to opioid-analgesic poisoning, according to data from the National Vital Statistics System.

Top health officials say isolation is key Ebola strategy

Isolating patients, more than a rollout of vaccines or any change in treatment strategy, is the cornerstone of the international effort to contain the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, say officials leading the response.

Steve Monroe, Ph.D., deputy director of the National Center for Emerging and Infectious diseases at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, summarized the state of the outbreak and the international response in a news conference Sept. 30, hours before the agency revealed the first imported case of Ebola documented in the United States in a traveler returning from Liberia.

In the two worst-affected countries, Sierra Leone and Liberia, cases are doubling approximately every 3 weeks. “One of the things CDC modeling data show is that we must get cases into isolation and treatment,” Dr. Monroe said. “We know how to control these outbreaks: Get patients into isolation so they don’t infect other people, and then follow their contacts.”

To stem the outbreak “we need to get, at a minimum, 70% of cases into effective isolation,” he said, and though increasing the number and location of Ebola treatment units was key to this effort, “all strategies should be considered,” including community centers, he said. “We can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Every delay results in an increasing number of people impacted by this disease.”

In Senegal and Nigeria, Dr. Monroe noted, no new cases have been reported in the past 21 days, suggesting that containment efforts have proven effective in these countries and demonstrating that outbreaks “can be brought under control” through rigorous isolation, notification of contacts, and breaking the chain of transmission. Both countries would “recognize if there is another importation and respond quickly,” he said.

Sophie Delaunay, executive director of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), also speaking at the news conference, characterized her organization as feeling “desperate and powerless” in the most affected countries but ready to respond to any sign of outbreak in neighboring countries thanks to extensive preparation work.

Ms. Delaunay added that MSF is also prioritizing isolation and safe burial of patients who have died from Ebola. “In an ideal situation, a safe and effective vaccine would be the best potential game changer … but this is not likely to be available until several months from now. In the meantime, we absolutely need to increase the [capacity for] isolation.”

Dr. Monroe noted that data indicate there has been very little evidence of community transmission related to public transportation or other settings of casual contact, with most cases attributable to direct patient care or funeral practices. “Those are the main drivers of transmission,” he said during the conference, sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The U.S. government has, to date, pledged $175 million for the Ebola response, with a little more than half the total already committed, with some $58 million marked for vaccine and antiviral drug development. Two vaccines are sponsored for clinical trials and likely to go into phase 2 testing during the course of the current outbreak, Dr. Monroe said. The U.S. Department of Defense has an additional $500 million to $1 billion in supplemental war funding that can be used to fight Ebola in West Africa, though it is unknown how much of this will be committed to Ebola.

Ms. Delaunay said that MSF has received pledges of $120 million, much of it from private donors, of which about half has been received.

The organization is preparing medical staff weekly in Belgium before they deploy to West Africa, she said, adding that, while getting more treatment units on the ground is a key priority, the quality of the response is dependent on how rigorous and disciplined the treatment of patients is. “You need to have strong discipline and chain of command,” she said.

Isolating patients, more than a rollout of vaccines or any change in treatment strategy, is the cornerstone of the international effort to contain the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, say officials leading the response.

Steve Monroe, Ph.D., deputy director of the National Center for Emerging and Infectious diseases at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, summarized the state of the outbreak and the international response in a news conference Sept. 30, hours before the agency revealed the first imported case of Ebola documented in the United States in a traveler returning from Liberia.

In the two worst-affected countries, Sierra Leone and Liberia, cases are doubling approximately every 3 weeks. “One of the things CDC modeling data show is that we must get cases into isolation and treatment,” Dr. Monroe said. “We know how to control these outbreaks: Get patients into isolation so they don’t infect other people, and then follow their contacts.”

To stem the outbreak “we need to get, at a minimum, 70% of cases into effective isolation,” he said, and though increasing the number and location of Ebola treatment units was key to this effort, “all strategies should be considered,” including community centers, he said. “We can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Every delay results in an increasing number of people impacted by this disease.”

In Senegal and Nigeria, Dr. Monroe noted, no new cases have been reported in the past 21 days, suggesting that containment efforts have proven effective in these countries and demonstrating that outbreaks “can be brought under control” through rigorous isolation, notification of contacts, and breaking the chain of transmission. Both countries would “recognize if there is another importation and respond quickly,” he said.

Sophie Delaunay, executive director of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), also speaking at the news conference, characterized her organization as feeling “desperate and powerless” in the most affected countries but ready to respond to any sign of outbreak in neighboring countries thanks to extensive preparation work.

Ms. Delaunay added that MSF is also prioritizing isolation and safe burial of patients who have died from Ebola. “In an ideal situation, a safe and effective vaccine would be the best potential game changer … but this is not likely to be available until several months from now. In the meantime, we absolutely need to increase the [capacity for] isolation.”

Dr. Monroe noted that data indicate there has been very little evidence of community transmission related to public transportation or other settings of casual contact, with most cases attributable to direct patient care or funeral practices. “Those are the main drivers of transmission,” he said during the conference, sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The U.S. government has, to date, pledged $175 million for the Ebola response, with a little more than half the total already committed, with some $58 million marked for vaccine and antiviral drug development. Two vaccines are sponsored for clinical trials and likely to go into phase 2 testing during the course of the current outbreak, Dr. Monroe said. The U.S. Department of Defense has an additional $500 million to $1 billion in supplemental war funding that can be used to fight Ebola in West Africa, though it is unknown how much of this will be committed to Ebola.

Ms. Delaunay said that MSF has received pledges of $120 million, much of it from private donors, of which about half has been received.

The organization is preparing medical staff weekly in Belgium before they deploy to West Africa, she said, adding that, while getting more treatment units on the ground is a key priority, the quality of the response is dependent on how rigorous and disciplined the treatment of patients is. “You need to have strong discipline and chain of command,” she said.

Isolating patients, more than a rollout of vaccines or any change in treatment strategy, is the cornerstone of the international effort to contain the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, say officials leading the response.

Steve Monroe, Ph.D., deputy director of the National Center for Emerging and Infectious diseases at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, summarized the state of the outbreak and the international response in a news conference Sept. 30, hours before the agency revealed the first imported case of Ebola documented in the United States in a traveler returning from Liberia.

In the two worst-affected countries, Sierra Leone and Liberia, cases are doubling approximately every 3 weeks. “One of the things CDC modeling data show is that we must get cases into isolation and treatment,” Dr. Monroe said. “We know how to control these outbreaks: Get patients into isolation so they don’t infect other people, and then follow their contacts.”

To stem the outbreak “we need to get, at a minimum, 70% of cases into effective isolation,” he said, and though increasing the number and location of Ebola treatment units was key to this effort, “all strategies should be considered,” including community centers, he said. “We can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Every delay results in an increasing number of people impacted by this disease.”

In Senegal and Nigeria, Dr. Monroe noted, no new cases have been reported in the past 21 days, suggesting that containment efforts have proven effective in these countries and demonstrating that outbreaks “can be brought under control” through rigorous isolation, notification of contacts, and breaking the chain of transmission. Both countries would “recognize if there is another importation and respond quickly,” he said.

Sophie Delaunay, executive director of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), also speaking at the news conference, characterized her organization as feeling “desperate and powerless” in the most affected countries but ready to respond to any sign of outbreak in neighboring countries thanks to extensive preparation work.

Ms. Delaunay added that MSF is also prioritizing isolation and safe burial of patients who have died from Ebola. “In an ideal situation, a safe and effective vaccine would be the best potential game changer … but this is not likely to be available until several months from now. In the meantime, we absolutely need to increase the [capacity for] isolation.”

Dr. Monroe noted that data indicate there has been very little evidence of community transmission related to public transportation or other settings of casual contact, with most cases attributable to direct patient care or funeral practices. “Those are the main drivers of transmission,” he said during the conference, sponsored by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The U.S. government has, to date, pledged $175 million for the Ebola response, with a little more than half the total already committed, with some $58 million marked for vaccine and antiviral drug development. Two vaccines are sponsored for clinical trials and likely to go into phase 2 testing during the course of the current outbreak, Dr. Monroe said. The U.S. Department of Defense has an additional $500 million to $1 billion in supplemental war funding that can be used to fight Ebola in West Africa, though it is unknown how much of this will be committed to Ebola.

Ms. Delaunay said that MSF has received pledges of $120 million, much of it from private donors, of which about half has been received.

The organization is preparing medical staff weekly in Belgium before they deploy to West Africa, she said, adding that, while getting more treatment units on the ground is a key priority, the quality of the response is dependent on how rigorous and disciplined the treatment of patients is. “You need to have strong discipline and chain of command,” she said.

Global Ebola—Are We Prepared?

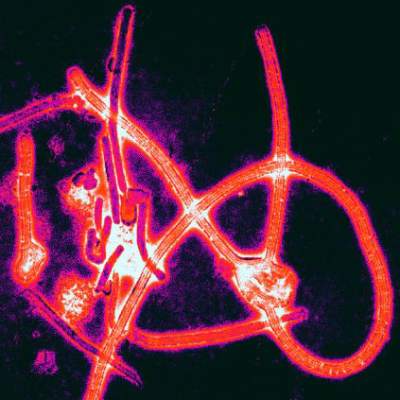

In this age of globalization, just a few hours of air travel separates even the most remote places in our world. Given this reality, the recent epidemic of Ebola virus disease (EVD) in West Africa (Figure 1) has arrived on the doorstep of Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. Ill and potentially infected US healthcare workers and missionaries brought home for treatment and quarantine, plus the travel of the general population through the affected countries of Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, and Nigeria, require all acute-care providers to be cognizant that this deadly disease may present in any community ED in the United States. Awareness and knowledge of the appropriate steps to manage care safely and effectively, while mindfully preventing the potential for viral transmission, is paramount.

Hemorrhagic Fevers

Viral hemorrhagic fevers are manifestations of four distinct families of RNA viruses: arenaviruses, bunyaviruses, flaviviruses, and filoviruses. All of these families of viruses depend on a natural insect or animal (nonhuman) host and are thus restricted geographically to the regions where the endemic hosts reside. The viruses can only infect a human when one comes into direct contact with an infected host; this human becomes an infectious host when symptoms of disease develop and subsequently, the possibility of transmission to other close direct human contacts exists.

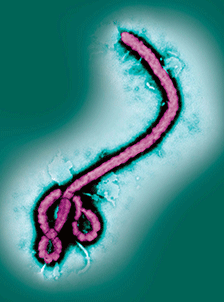

Ebola Virus Species

The family within which the Ebola virus species are classified is the filoviruses. Five species of Ebola filovirus have been isolated to date: Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus), Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus), Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus), and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), has caused disease in nonhuman primates, but not in humans. This epidemic has been attributed to a variant of the Zaire species.2 Transmission through direct contact with body fluids of febrile live infected patients and the postmortem period continues in communities and healthcare sites, as lack of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and meticulous environmental hygiene remains a challenge in many of these settings.

Clinical Presentation

In EVD, the onset of symptoms typically occurs abruptly at an average of 8 to 10 days postexposure and includes fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise; in some patients, an erythematous maculopapular rash involving the face, neck, trunk, and arms erupts by days 5 to 7.1 The nonspecific nature of these early signs and symptoms warrants caution in any patient known to have traveled in an endemic country with potential exposure to body fluids of infected patients—underscoring the importance of both obtaining a complete travel history to determine the potential for disease exposure in patients presenting with infectious-disease symptoms and effectively communicating this information to all ED staff.

In addition, such caution includes healthcare mission workers caring for Ebola patients, those involved in butchering infected animals for meat, and persons participating in traditional funeral rituals for those deceased from Ebola without the use of adequate PPE and/or environmental hygiene. Other more common infectious diseases with shared features of EVD must also be considered at this stage and include malaria, meningococcemia, measles, and typhoid fever, among others.

After the first 5 days of exposure, progression of symptoms may include severe watery diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, shortness of breath, chest pain, headache, and/or confusion. Conjunctival injection may also develop. Not all patients will have signs of hemorrhagic fever with bleeding from the mouth, eyes, ears, in stool, or from internal organs, but petechiae, ecchymosis, and oozing from venipuncture sites may develop. Those at the highest risk of death show signs of sepsis, such as shock and multiorgan system failure, which may include hemorrhagic manifestations, early in the course of their illness. Patients with these complications typically expire between days 6 to16.1 Survivors of the disease tend to have fever with less severe symptoms for a period of several more days, and then begin to improve clinically between days 6 to 11 after onset of symptoms1 (Figure 3).

Ecology

A zoonotic filovirus transmissible from animal populations to humans causes EVD. Research strongly suggests that fruit bats are the reservoir and hosts for this filovirus. Direct human contact with bats or with wild animals that have been infected by bats initiates the human-to-human transmission of EVD.3

Pathogenesis

Through direct contact with mucous membranes, a break in the skin, or parenterally, Ebola enters and infects multiple cell types. Incubation periods appear shorter in infections acquired through direct injection (6 days) than for contact transmission (10 days).1 Emesis, urine, stool, sweat, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, and saliva are actively capable of viral transmission. From point of entry, the virus migrates to the lymph nodes, then to liver, spleen, and adrenal glands. Hepatocellular necrosis leads to clotting-factor derangement and dysfunction resulting in coagulopathy and bleeding and potential liver failure. Necrosis of adrenal tissue may be present and results in impaired steroid synthesis and hypotension. The presence of the virus appears to incite a cytokine inflammatory storm causing microvascular leakage, with the end effect of multiorgan system failure, shock, coagulopathy, and lymphocytopenia from cellular apoptosis.1 With cellular death, immune system function is further disabled, more viral particles are released into the infected host, and body fluids remain infectious postmortem.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings in viral hemorrhagic fevers can vary depending on the exact viral cause and the stage in the disease process. Leukocyte counts in early stages can reveal leukopenia and specifically lymphopenia, while in later stages leukocytosis with a left shift of neutrophils can predominate. Hemoglobin and hematocrit can show relative hemoconcentration, especially if renal manifestations of the disease occur. Thrombocytopenia also develops with viral hemorrhagic fevers, although in late stages thrombocytosis has been seen. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr) levels will rise with the occurrence of acute renal failure in late stages of the disease. Liver function studies, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in particular, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) have been found to rise in severe disease and in late stages due to multifocal hepatic necrosis, with AST typically greater than ALT. An association between elevated AST (~900 IU/L), BUN, Cr, albumin levels, and mortality has been statistically confirmed by McElroy et al4 in the Ebola outbreak in Uganda in 2000 to 2001; findings previously confirmed in the same geographic and temporal outbreak by Rollin et al.5 Survivors did not have nearly the same degree of elevation in liver enzymes, with AST levels averaging ~150 IU/L.5 The authors suggested that normalizing AST levels was perhaps indicative of acute recovery, but some patients still succumbed to complications of the illness.5

Coagulation studies, including prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, d-dimer, and fibrin split products will reflect disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in those patients who develop hemorrhagic manifestations, which is common in late stages of the disease. Direct infection of vascular endothelial cells with damage to these cells has been shown to occur in the course of infection, yet nonhuman primate experimental studies and pathology examinations of Ebola victims have implied that DIC plays an important part in the hemorrhagic disease leading to the fatal shock syndrome seen in the most severe cases.6 Observed in 2000 during the care of Sudan species EVD patients in Uganda reported by Rollin et al,5 a distinct difference has been noted in quantitative d-dimer levels between survivors and fatal cases. Case fatalities showed a 4-fold increase in quantitative d-dimer levels (140,000 ng/mL) compared with survivors (44,000 ng/mL) during the acute phase of infection 6 to 8 days postsymptom onset.5

Acute phase reactants, high nitric oxide levels, cytokines, and higher viral loads have also been associated with fatal outcomes.4 McElroy et al4 measured the common acute phase reactant biomarker ferritin in patients of the 2000 Uganda outbreak and found levels to be higher in samples from patients who died and from patients with hemorrhagic complications and higher viral loads. Thus, these authors postulate ferritin is a potential marker for EVD severity.4

Commercially available assays for detection of viral particles are still in development and no point-of-care rapid detection testing is available. No test can reliably be used to diagnose viral hemorrhagic fever prior to symptom onset.7 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of viral particles or tissue cell cultures are available only through the CDC, and are the current most reliable methods to confirm the diagnosis of viral hemorrhagic fevers, including Ebola.

Patient Management in the ED

Standard infection-control procedures in place in US hospitals, when meticulously practiced, should be adequate to prevent transmission of EVD. As Ebola virus is only transmitted through direct contact with infected body fluids and secretions, PPE including mask, gloves, gown, shoe covers, and eye protection (goggles or face shield), should be appropriate. In donning PPE, remember that gloves should be the last item to pull in place and to pull off, turning the gown and gloves inside out. One’s hands should be washed before removing the mask and face shield/goggles, and they should be rewashed after completion of PPE removal. A tight fit of the glove over the elastic wristband of the gown is preferable and can ensure a better barrier to any biohazard. Meticulous hand hygiene after removal and proper disposal of PPE is paramount to successful contact protection. Diligent care should be taken in any procedure that might expose a healthcare provider to body fluids, such as blood draws, central line insertion, lumbar puncture and other invasive procedures. Standard contact isolation methods with the patient in a single room with the door closed is sufficient. Appropriate use of standard hospital disinfectants, including bleach solutions or hospital grade ammonium cleaners are already standard practice and easily implemented. It is recommended that procedures that produce aerosol particles should be avoided in patients with suspected infection; yet in some circumstances, the course of care may require such procedures. In this case, to minimize potential airborne spread, airborne and droplet precautions should also be initiated by placing the patient in a negative pressure room and implementing the use of properly fitted N-95 respirators for all present in the room.8

The mainstay of treatment for viral hemorrhagic fevers in the ED begins with initiation of contact isolation of the patient to prevent spread to the healthy. Supportive care involving aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation to maintain blood pressure, oxygen support as needed, blood products as indicated for DIC, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, including dialysis for renal failure, is the only treatment widely available at this time. In patients who exhibit generalized edema as a result of hypoproteinemia from liver damage and third spacing, serum protein monitoring and replacement is indicated.9

An experimental treatment, ZMapp, which is a monoclonal antibody that is derived from mice and blocks Ebola from entering cells, has recently been used in combination with supportive treatment in six individuals infected with Ebola. However, ZMapp is still in early stages of development and testing is not widely available. No clinical trials have begun, but are planned. Two individuals treated with ZMapp have recovered in the United States; three healthcare workers are recovering in West Africa10,11; and one patient has died. It is not clear whether this medication is responsible wholly or in part for their recovery.

According to Dr Bruce Ribner, Director of Emory University Hospital’s Infectious Disease unit in an interview with Scientific American’s Dina Fine Maron on August 27, 2014, the two patients cared for at Emory have developed immunity to Zaire Ebolavirus.11 Continued outpatient monitoring is allowing study to help understand immunity to Ebola, and may lead to further treatment and vaccination development. Thus far, cross-protection against other Ebola viral strains for these recovered individuals is not as robust, indicating that this family of viruses are different enough that recovery from infection with one species may not be enough to confer immunity to a different species exposure. Blood transfusions from recovered patients have been described, but there is no clinical evidence to support any benefit from this therapy at this time.9

Personal protective equipment is a mainstay in the collection of specimens for viral-specific testing by the CDC, including full-face shield or goggles, masks to cover nose and mouth, gowns, and gloves. For routine laboratory testing and patient care, all of the above PPE is recommended, along with use of a biosafety cabinet or plexiglass splash guard, which is in accordance with Occupational Safety and Health Administration bloodborne pathogens standards.12

Specimens should be collected for Ebola testing only after the onset of symptoms, such as fever (see Table for supplemental information). In patients suspected of having viral exposure, it may take up to 3 days for the virus to reach detectable levels with RT-PCR. Consultation per hospital procedure with the local and/or state health department prior to specimen transport for testing to the CDC is mandatory. Public health officials will help ensure appropriate patient selection and proper procedures for specimen collection, and make arrangements for testing, which is only available through the CDC. The CDC will not accept any specimen without appropriate local/state health department consultation.

Ideally, preferred specimens for Ebola testing include 4 mL of whole blood properly preserved with EDTA, clot activator, sodium polyanethol sulfonate, or citrate in plastic collection tubes stored at 4˚C or frozen.12 Specimens should be placed in a durable, leak-proof container for transport within a facility; pneumatic tube systems should be avoided due to concerns for glass breakage or leaks. Hospitals should follow state or local health department policies and procedures for Ebola testing prior to notifying the CDC and initiating sample transportation.

The Dallas Index Case

Deplaning a flight from Liberia in Dallas, Texas on September 20, this index patient had no outward signs of illness, and thus no reason to cause any health concern. Joining in the community with friends and family, it was not until 4 days later that he reportedly developed a fever. Yet 2 more days passed before this patient initially sought ambulatory care at Dallas Health Presbyterian Hospital Emergency Department, during which time additional close contacts were exposed to infection. After evaluation, antibiotics were prescribed and the patient was released. Though this case is under investigation, according to a CNN report,13 the patient did inform a member of the ED nursing staff of his travel history, but this information was not communicated to the rest of the healthcare team. The presence and recognition of this patient’s travel history with disease symptoms heightens the level of suspicion for the possibility of EVD, and is the cornerstone of patient selection for Ebola testing.14

After the patient was discharged, another 2 days passed, during which time his condition deteriorated at home. Emergency medical services (EMS) transport was summoned to take the patient back to the hospital, expanding exposure to first responders, who appropriately utilized masks and gloves during transport. During this ED visit, his travel history was obtained and communicated, and he was appropriately isolated, supported, and admitted. These are early reported details of the case, and local public health officials continue to work with a team from the CDC to trace, isolate, and monitor all contacts with this patient (including the transporting emergency medical technicians) for evidence of further cases.15

This index case illustrates valuable lessons for all emergency care workers going forward. Ebola virus disease is now global, in the sense that it has proven its ability to present in a community far from its endemic home. Infectious diseases in their early stages present in nonspecific constellations of symptoms, and the key to rapid identification of EVD lies in careful attention to the recent travel history and exposure potential. Since patients may not offer this information for various reasons (eg, degree of symptoms, language barriers, fear, denial), it must be sought out lest more index patients be released into the public. As CDC Director Thomas Frieden related to CNN, “If someone’s been in West Africa within 21 days and they’ve got a fever, immediately isolate them and get them tested for Ebola.”13

Concerning the EMS transport of this patient, the ambulance used was disinfected per standard local protocols and remained in service for 2 days after this patient was transported. Though local officials are confident in the disinfection technique, it was pulled from service after the diagnosis was confirmed to ensure its full sterilization from Ebola virus16 before returning to full service. The rapid and robust public health response in progress will undoubtedly reveal further information over the coming days to weeks. To quote Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, “We are going to see more cases show up around the world.”15

In addition to the index patient, it is important to keep in mind that secondary cases may present. If this occurs, the travel question must be altered to reflect the possibility that a secondary patient may not have been the traveler but rather one who was in close contact with an ill person who was in contact with him or her. Such a scenario would have a huge impact if that traveler did not seek treatment and would in turn require ED personnel to seek-out the information and report it to local public health officials.

Quelling the Panic

Even though Ebola is only spread through direct contact with infected bodily secretions, there is still significant public fear of the disease due to the high mortality rate and the graphic nature of symptoms in late stages of the disease. Daily monitoring of contacts of symptomatic Ebola patients for evidence of disease development—mainly fever—is sensible. Asymptomatic persons need not be confined or hospitalized unless fever develops, in which case contact isolation should occur until formal Ebola testing can rule-out the disease. Personal protective equipment, standardized hospital cleaning protocols with meticulous adherence, as well as quickly burying the deceased with adequate contact precautions, can all limit potential exposure and spread of the disease. Public health discussion and education about the virus and methods of transmission are needed so that individuals are not denied proper treatment or scared away from medical centers.

Importantly, communication by public health and medical experts on local and national levels should be with news media that embrace honest and careful reporting to avoid sensationalism and foster appropriate concern—ensuring that content is fundamental to curtailing panic and undue public fear.

For Internationally Traveling Clinicians

At present, the area endemic for Ebola remains confined to sub-Saharan Africa and West Africa. Clinicians should remain alert when traveling or treating patients in these areas. However, with the ease of international air travel, the potential for the spread of disease is recognized with many bordering nations now screening passengers from affected countries and some closing their borders to travelers from endemic areas. If a clinician encounters febrile patients in endemic areas, the differential diagnosis for any febrile illness must include Ebola, as well as malaria and other more common infectious agents. A thorough history about recent travel, ill contacts, and possible exposures should be sufficient in categorizing the risk of Ebola, but a high index of suspicion is necessary for prompt and proper treatment of those affected and to curtail spread of disease.