User login

Precocious puberty – how early is too soon?

A 6-year-old girl presents with breast development. Her medical history is unremarkable. The parents are of average height, and the mother reports her thelarche was age 11 years. The girl is at the 97th percentile for her height and 90th percentile for her weight. She has Tanner stage 3 breast development and Tanner stage 2 pubic hair development. She has grown slightly more than 3 inches over the past year. How should she be evaluated and managed (N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2366-77)?

The premature onset of puberty, i.e., precocious puberty (PP), can be an emotionally traumatic event for the child and parents. Over the past century, improvements in public health and nutrition, and, more recently, increased obesity, have been associated with earlier puberty and the dominant factor has been attributed to genetics (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25[1]:49-54). This month’s article will focus on understanding what is considered “early” puberty, evaluating for causes, and managing precocious puberty.

More commonly seen in girls than boys, PP is defined as the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before age 7.5 years in Black and Hispanic girls, and prior to 8 years in White girls, which is 2-2.5 standard deviations below the average age of pubertal onset in healthy children (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455-9). As a comparison, PP is diagnosed with onset before age 9 years in boys. For White compared with Black girls, the average timing of thelarche is age 10 vs. 9.5 years, peak growth velocity is age 11.5, menarche is age 12.5 vs. 12, while completion of puberty is near age 14.5 vs. 13.5, respectively (J Pediatr. 1985;107:317). Fortunately, most girls with PP have common variants rather than serious pathology.

Classification: Central (CPP) vs. peripheral (PPP)

CPP is gonadotropin dependent, meaning the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPO) is prematurely activated resulting in the normal progression of puberty.

PPP is gonadotropin independent, caused by sex steroid secretion from any source – ovaries, adrenal gland, exogenous or ectopic production, e.g., germ-cell tumor. This results in a disordered progression of pubertal milestones.

Whereas CPP is typically isosexual development, i.e., consistent with the child’s gender, PPP can be isosexual or contrasexual, e.g., virilization of girls. A third classification is “benign or nonprogressive pubertal variants” manifesting as isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche.

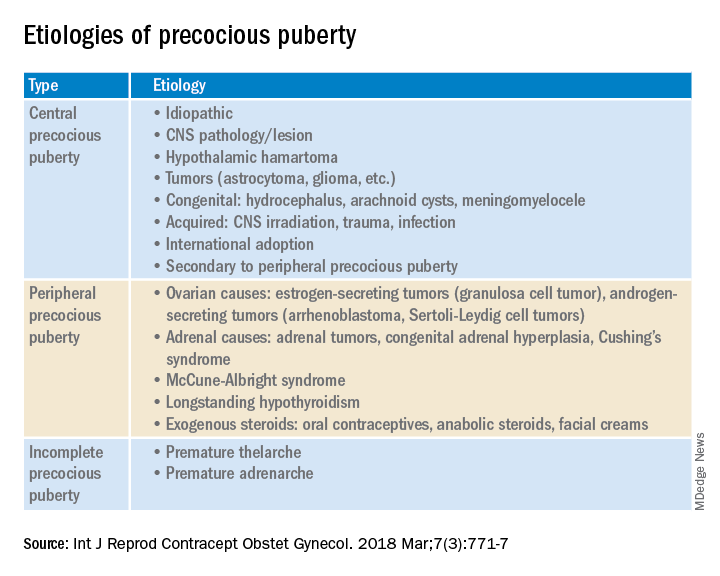

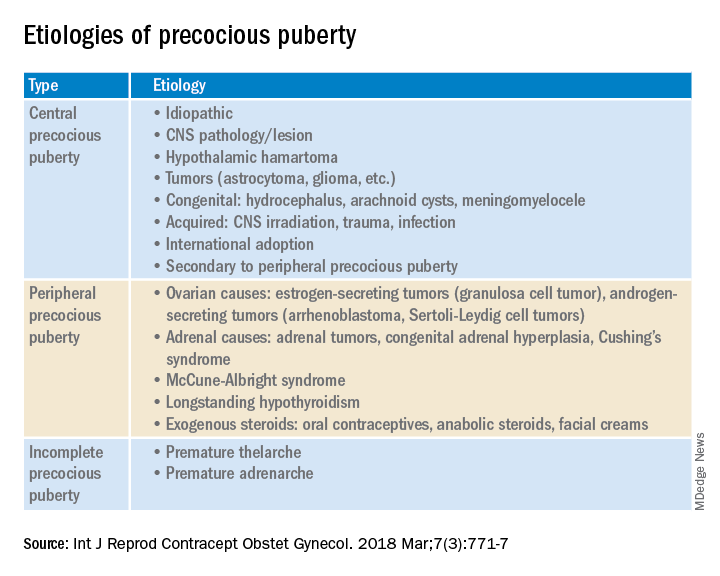

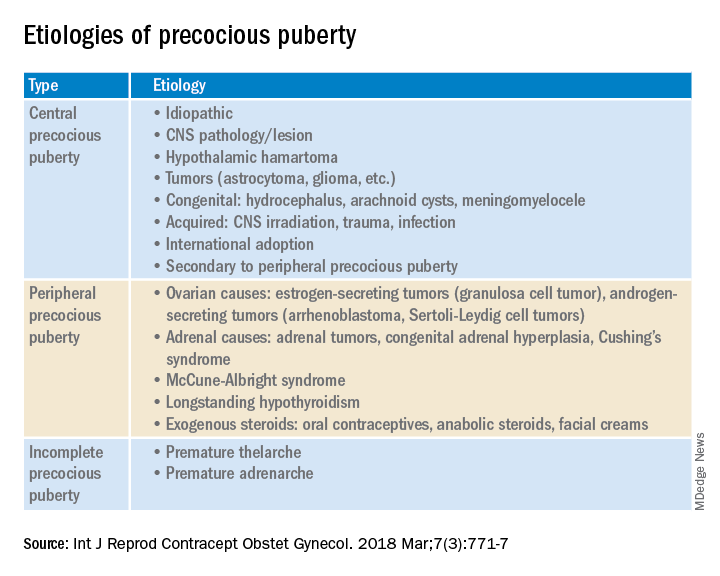

Causes (see table)

CPP. Idiopathic causes account for 80%-90% of presentations in girls and 25%-80% in boys. Remarkably, international and domestic adoption, as well as a family history of PP increases the likelihood of CPP in girls. Other etiologies include CNS lesions, e.g., hamartomas, which are the most common cause of PP in young children. MRI with contrast has been the traditional mode of diagnosis for CNS tumors, yet the yield is dubious in girls above age 6. Genetic causes are found in only a small percentage of PP cases. Rarely, CPP can result from gonadotropin-secreting tumors because of elevated luteinizing hormone levels.

PPP. As a result of sex steroid secretion, peripheral causes of PPP include ovarian cysts and ovarian tumors that increase circulating estradiol, such as granulosa cell tumors, which would cause isosexual PPP and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors that secrete testosterone, which can result in contrasexual PPP. Mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia can result in PPP with virilization (contrasexual) and markedly advanced bone age.

McCune-Albright syndrome is rare and presents with the classic triad of PPP, skin pigmentation called café-au-lait, and fibrous dysplasia of bone. The pathophysiology of McCune-Albright syndrome is autoactivation of the G-protein leading to activation of ovarian tissue that results in formation of large ovarian cysts and extreme elevations in serum estradiol as well as the potential production of other hormones, e.g., thyrotoxicosis, excess growth hormone (acromegaly), and Cushing syndrome.

Premature thelarche. Premature thelarche typically occurs in girls between the ages of 1 and 3 years and is limited to breast enlargement. While no cause has been determined, the plausible explanations include partial activation of the HPO axis, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or a genetic origin. A small percentage of these girls progress to CPP.

EDCs have been considered as potential influencers of early puberty, but no consensus has been established. (Examples of EDCs in the environment include air, soil, or water supply along with food sources, personal care products, and manufactured products that can affect the endocrine system.)

Premature adenarche. Premature adrenarche presents with adult body odor and/or body hair (pubic and/or axillary) in girls who have an elevated body mass index, most commonly at the ages of 6-7 years. The presumed mechanism is normal maturation of the adrenal gland with resultant elevation of circulating androgens. Bone age may be mildly accelerated and DHEAS is prematurely elevated for age. These girls appear to be at increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome.

Evaluation

The initial step in the evaluation of PP is to determine whether the cause is CPP or PPP; the latter includes distinguishing isosexual from contrasexual development. A thorough history (growth, headaches, behavior or visual change, seizures, abdominal pain), physical exam, including Tanner staging, and bone age is required. However, with isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche, a bone age may not be necessary, as initial close clinical observation for pubertal progression is likely sufficient.

For CPP, the diagnosis is based on serum LH, whether random levels or elevations follow GnRH stimulation. Puberty milestones progress normally although adrenarche is not consistently apparent. For girls younger than age 6, a brain MRI is recommended but not in asymptomatic older girls with CPP. LH and FSH along with estradiol or testosterone, the latter especially in boys, are the first line of serum testing. Serum TSH is recommended for suspicion of primary hypothyroidism. In girls with premature adrenarche, a bone age, testosterone, DHEAS, and 17-OHP to rule out adrenal hyperplasia should be obtained. Pelvic ultrasound may be a useful adjunct to assess uterine volume and/or ovarian cysts/tumors.

Rapidity of onset can also lead the evaluation since a normal growth chart and skeletal maturation suggests a benign pubertal variant whereas a more rapid rate can signal CPP or PPP. Of note, health care providers should ensure prescription, over-the-counter oral or topical sources of hormones, and EDCs are ruled out.

Consequences

An association between childhood sexual abuse and earlier pubertal onset has been cited. These girls may be at increased risk for psychosocial difficulties, menstrual and fertility problems, and even reproductive cancers because of prolonged exposure to sex hormones (J Adolesc Health. 2016;60[1]:65-71).

Treatment

The mainstay of CPP treatment is maximizing adult height, typically through the use of a GnRH agonist for HPO suppression from pituitary downregulation. For girls above age 8 years, attempts at improving adult height have not shown a benefit.

In girls with PPP, treatment is directed at the prevailing pathology. Interestingly, early PPP can activate the HPO axis thereby converting to “secondary” CPP. In PPP, McCune-Albright syndrome treatment targets reducing circulating estrogens through letrozole or tamoxifen as well as addressing other autoactivated hormone production. Ovarian and adrenal tumors, albeit rare, can cause PP; therefore, surgical excision is the goal of treatment.

PP should be approached with equal concerns about the physical and emotional effects while including the family to help them understand the pathophysiology and psychosocial risks.

Dr. Mark P. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

A 6-year-old girl presents with breast development. Her medical history is unremarkable. The parents are of average height, and the mother reports her thelarche was age 11 years. The girl is at the 97th percentile for her height and 90th percentile for her weight. She has Tanner stage 3 breast development and Tanner stage 2 pubic hair development. She has grown slightly more than 3 inches over the past year. How should she be evaluated and managed (N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2366-77)?

The premature onset of puberty, i.e., precocious puberty (PP), can be an emotionally traumatic event for the child and parents. Over the past century, improvements in public health and nutrition, and, more recently, increased obesity, have been associated with earlier puberty and the dominant factor has been attributed to genetics (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25[1]:49-54). This month’s article will focus on understanding what is considered “early” puberty, evaluating for causes, and managing precocious puberty.

More commonly seen in girls than boys, PP is defined as the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before age 7.5 years in Black and Hispanic girls, and prior to 8 years in White girls, which is 2-2.5 standard deviations below the average age of pubertal onset in healthy children (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455-9). As a comparison, PP is diagnosed with onset before age 9 years in boys. For White compared with Black girls, the average timing of thelarche is age 10 vs. 9.5 years, peak growth velocity is age 11.5, menarche is age 12.5 vs. 12, while completion of puberty is near age 14.5 vs. 13.5, respectively (J Pediatr. 1985;107:317). Fortunately, most girls with PP have common variants rather than serious pathology.

Classification: Central (CPP) vs. peripheral (PPP)

CPP is gonadotropin dependent, meaning the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPO) is prematurely activated resulting in the normal progression of puberty.

PPP is gonadotropin independent, caused by sex steroid secretion from any source – ovaries, adrenal gland, exogenous or ectopic production, e.g., germ-cell tumor. This results in a disordered progression of pubertal milestones.

Whereas CPP is typically isosexual development, i.e., consistent with the child’s gender, PPP can be isosexual or contrasexual, e.g., virilization of girls. A third classification is “benign or nonprogressive pubertal variants” manifesting as isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche.

Causes (see table)

CPP. Idiopathic causes account for 80%-90% of presentations in girls and 25%-80% in boys. Remarkably, international and domestic adoption, as well as a family history of PP increases the likelihood of CPP in girls. Other etiologies include CNS lesions, e.g., hamartomas, which are the most common cause of PP in young children. MRI with contrast has been the traditional mode of diagnosis for CNS tumors, yet the yield is dubious in girls above age 6. Genetic causes are found in only a small percentage of PP cases. Rarely, CPP can result from gonadotropin-secreting tumors because of elevated luteinizing hormone levels.

PPP. As a result of sex steroid secretion, peripheral causes of PPP include ovarian cysts and ovarian tumors that increase circulating estradiol, such as granulosa cell tumors, which would cause isosexual PPP and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors that secrete testosterone, which can result in contrasexual PPP. Mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia can result in PPP with virilization (contrasexual) and markedly advanced bone age.

McCune-Albright syndrome is rare and presents with the classic triad of PPP, skin pigmentation called café-au-lait, and fibrous dysplasia of bone. The pathophysiology of McCune-Albright syndrome is autoactivation of the G-protein leading to activation of ovarian tissue that results in formation of large ovarian cysts and extreme elevations in serum estradiol as well as the potential production of other hormones, e.g., thyrotoxicosis, excess growth hormone (acromegaly), and Cushing syndrome.

Premature thelarche. Premature thelarche typically occurs in girls between the ages of 1 and 3 years and is limited to breast enlargement. While no cause has been determined, the plausible explanations include partial activation of the HPO axis, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or a genetic origin. A small percentage of these girls progress to CPP.

EDCs have been considered as potential influencers of early puberty, but no consensus has been established. (Examples of EDCs in the environment include air, soil, or water supply along with food sources, personal care products, and manufactured products that can affect the endocrine system.)

Premature adenarche. Premature adrenarche presents with adult body odor and/or body hair (pubic and/or axillary) in girls who have an elevated body mass index, most commonly at the ages of 6-7 years. The presumed mechanism is normal maturation of the adrenal gland with resultant elevation of circulating androgens. Bone age may be mildly accelerated and DHEAS is prematurely elevated for age. These girls appear to be at increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome.

Evaluation

The initial step in the evaluation of PP is to determine whether the cause is CPP or PPP; the latter includes distinguishing isosexual from contrasexual development. A thorough history (growth, headaches, behavior or visual change, seizures, abdominal pain), physical exam, including Tanner staging, and bone age is required. However, with isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche, a bone age may not be necessary, as initial close clinical observation for pubertal progression is likely sufficient.

For CPP, the diagnosis is based on serum LH, whether random levels or elevations follow GnRH stimulation. Puberty milestones progress normally although adrenarche is not consistently apparent. For girls younger than age 6, a brain MRI is recommended but not in asymptomatic older girls with CPP. LH and FSH along with estradiol or testosterone, the latter especially in boys, are the first line of serum testing. Serum TSH is recommended for suspicion of primary hypothyroidism. In girls with premature adrenarche, a bone age, testosterone, DHEAS, and 17-OHP to rule out adrenal hyperplasia should be obtained. Pelvic ultrasound may be a useful adjunct to assess uterine volume and/or ovarian cysts/tumors.

Rapidity of onset can also lead the evaluation since a normal growth chart and skeletal maturation suggests a benign pubertal variant whereas a more rapid rate can signal CPP or PPP. Of note, health care providers should ensure prescription, over-the-counter oral or topical sources of hormones, and EDCs are ruled out.

Consequences

An association between childhood sexual abuse and earlier pubertal onset has been cited. These girls may be at increased risk for psychosocial difficulties, menstrual and fertility problems, and even reproductive cancers because of prolonged exposure to sex hormones (J Adolesc Health. 2016;60[1]:65-71).

Treatment

The mainstay of CPP treatment is maximizing adult height, typically through the use of a GnRH agonist for HPO suppression from pituitary downregulation. For girls above age 8 years, attempts at improving adult height have not shown a benefit.

In girls with PPP, treatment is directed at the prevailing pathology. Interestingly, early PPP can activate the HPO axis thereby converting to “secondary” CPP. In PPP, McCune-Albright syndrome treatment targets reducing circulating estrogens through letrozole or tamoxifen as well as addressing other autoactivated hormone production. Ovarian and adrenal tumors, albeit rare, can cause PP; therefore, surgical excision is the goal of treatment.

PP should be approached with equal concerns about the physical and emotional effects while including the family to help them understand the pathophysiology and psychosocial risks.

Dr. Mark P. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

A 6-year-old girl presents with breast development. Her medical history is unremarkable. The parents are of average height, and the mother reports her thelarche was age 11 years. The girl is at the 97th percentile for her height and 90th percentile for her weight. She has Tanner stage 3 breast development and Tanner stage 2 pubic hair development. She has grown slightly more than 3 inches over the past year. How should she be evaluated and managed (N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2366-77)?

The premature onset of puberty, i.e., precocious puberty (PP), can be an emotionally traumatic event for the child and parents. Over the past century, improvements in public health and nutrition, and, more recently, increased obesity, have been associated with earlier puberty and the dominant factor has been attributed to genetics (Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25[1]:49-54). This month’s article will focus on understanding what is considered “early” puberty, evaluating for causes, and managing precocious puberty.

More commonly seen in girls than boys, PP is defined as the onset of secondary sexual characteristics before age 7.5 years in Black and Hispanic girls, and prior to 8 years in White girls, which is 2-2.5 standard deviations below the average age of pubertal onset in healthy children (J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455-9). As a comparison, PP is diagnosed with onset before age 9 years in boys. For White compared with Black girls, the average timing of thelarche is age 10 vs. 9.5 years, peak growth velocity is age 11.5, menarche is age 12.5 vs. 12, while completion of puberty is near age 14.5 vs. 13.5, respectively (J Pediatr. 1985;107:317). Fortunately, most girls with PP have common variants rather than serious pathology.

Classification: Central (CPP) vs. peripheral (PPP)

CPP is gonadotropin dependent, meaning the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (HPO) is prematurely activated resulting in the normal progression of puberty.

PPP is gonadotropin independent, caused by sex steroid secretion from any source – ovaries, adrenal gland, exogenous or ectopic production, e.g., germ-cell tumor. This results in a disordered progression of pubertal milestones.

Whereas CPP is typically isosexual development, i.e., consistent with the child’s gender, PPP can be isosexual or contrasexual, e.g., virilization of girls. A third classification is “benign or nonprogressive pubertal variants” manifesting as isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche.

Causes (see table)

CPP. Idiopathic causes account for 80%-90% of presentations in girls and 25%-80% in boys. Remarkably, international and domestic adoption, as well as a family history of PP increases the likelihood of CPP in girls. Other etiologies include CNS lesions, e.g., hamartomas, which are the most common cause of PP in young children. MRI with contrast has been the traditional mode of diagnosis for CNS tumors, yet the yield is dubious in girls above age 6. Genetic causes are found in only a small percentage of PP cases. Rarely, CPP can result from gonadotropin-secreting tumors because of elevated luteinizing hormone levels.

PPP. As a result of sex steroid secretion, peripheral causes of PPP include ovarian cysts and ovarian tumors that increase circulating estradiol, such as granulosa cell tumors, which would cause isosexual PPP and Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors that secrete testosterone, which can result in contrasexual PPP. Mild congenital adrenal hyperplasia can result in PPP with virilization (contrasexual) and markedly advanced bone age.

McCune-Albright syndrome is rare and presents with the classic triad of PPP, skin pigmentation called café-au-lait, and fibrous dysplasia of bone. The pathophysiology of McCune-Albright syndrome is autoactivation of the G-protein leading to activation of ovarian tissue that results in formation of large ovarian cysts and extreme elevations in serum estradiol as well as the potential production of other hormones, e.g., thyrotoxicosis, excess growth hormone (acromegaly), and Cushing syndrome.

Premature thelarche. Premature thelarche typically occurs in girls between the ages of 1 and 3 years and is limited to breast enlargement. While no cause has been determined, the plausible explanations include partial activation of the HPO axis, endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), or a genetic origin. A small percentage of these girls progress to CPP.

EDCs have been considered as potential influencers of early puberty, but no consensus has been established. (Examples of EDCs in the environment include air, soil, or water supply along with food sources, personal care products, and manufactured products that can affect the endocrine system.)

Premature adenarche. Premature adrenarche presents with adult body odor and/or body hair (pubic and/or axillary) in girls who have an elevated body mass index, most commonly at the ages of 6-7 years. The presumed mechanism is normal maturation of the adrenal gland with resultant elevation of circulating androgens. Bone age may be mildly accelerated and DHEAS is prematurely elevated for age. These girls appear to be at increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome.

Evaluation

The initial step in the evaluation of PP is to determine whether the cause is CPP or PPP; the latter includes distinguishing isosexual from contrasexual development. A thorough history (growth, headaches, behavior or visual change, seizures, abdominal pain), physical exam, including Tanner staging, and bone age is required. However, with isolated premature thelarche or adrenarche, a bone age may not be necessary, as initial close clinical observation for pubertal progression is likely sufficient.

For CPP, the diagnosis is based on serum LH, whether random levels or elevations follow GnRH stimulation. Puberty milestones progress normally although adrenarche is not consistently apparent. For girls younger than age 6, a brain MRI is recommended but not in asymptomatic older girls with CPP. LH and FSH along with estradiol or testosterone, the latter especially in boys, are the first line of serum testing. Serum TSH is recommended for suspicion of primary hypothyroidism. In girls with premature adrenarche, a bone age, testosterone, DHEAS, and 17-OHP to rule out adrenal hyperplasia should be obtained. Pelvic ultrasound may be a useful adjunct to assess uterine volume and/or ovarian cysts/tumors.

Rapidity of onset can also lead the evaluation since a normal growth chart and skeletal maturation suggests a benign pubertal variant whereas a more rapid rate can signal CPP or PPP. Of note, health care providers should ensure prescription, over-the-counter oral or topical sources of hormones, and EDCs are ruled out.

Consequences

An association between childhood sexual abuse and earlier pubertal onset has been cited. These girls may be at increased risk for psychosocial difficulties, menstrual and fertility problems, and even reproductive cancers because of prolonged exposure to sex hormones (J Adolesc Health. 2016;60[1]:65-71).

Treatment

The mainstay of CPP treatment is maximizing adult height, typically through the use of a GnRH agonist for HPO suppression from pituitary downregulation. For girls above age 8 years, attempts at improving adult height have not shown a benefit.

In girls with PPP, treatment is directed at the prevailing pathology. Interestingly, early PPP can activate the HPO axis thereby converting to “secondary” CPP. In PPP, McCune-Albright syndrome treatment targets reducing circulating estrogens through letrozole or tamoxifen as well as addressing other autoactivated hormone production. Ovarian and adrenal tumors, albeit rare, can cause PP; therefore, surgical excision is the goal of treatment.

PP should be approached with equal concerns about the physical and emotional effects while including the family to help them understand the pathophysiology and psychosocial risks.

Dr. Mark P. Trolice is director of The IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando.

Book Review: Quality improvement in mental health care

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

Sunil Khushalani and Antonio DePaolo,

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare”

(London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2022)

Since the publication of our book, “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story” (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2014) almost a decade ago, “Transforming Mental Healthcare” is the first major book published about the use of a system for quality improvement across the health care continuum. That it has taken this long is probably surprising to those of us who have spent careers on trying to improve what is universally described as a system that is “broken” and in need of a major overhaul.

Every news cycle that reports mass violence typically spends a good bit of time talking about the failures of the mental health care system. One important lesson I learned when taking over the beleaguered Kings County (N.Y.) psychiatry service in 2009 (a department that has made extraordinary improvements over the years and is now exclaimed by the U.S. Department of Justice as “a model program”), is that the employees on the front line are often erroneously blamed for such failures.

The failure is systemic and usually starts at the top of the table of organization, not at the bottom. Dr. Khushalani and Dr. DePaolo have produced an excellent volume that should be purchased by every mental health care CEO and given “with thanks” to the local leaders overseeing the direct care of some of our nation’s most vulnerable patient populations.

The first part of “Transforming Mental Healthcare” provides an excellent overview of the current state of our mental health care system and its too numerous to name problems. This section could be a primer for all our legislators so their eyes can be opened to the failures on the ground that require their help in correcting. Many of the “failures” of our mental health care are societal failures – lack of affordable housing, access to care, reimbursement for care, gun access, etc. – and cannot be “fixed” by providers of care. Such problems are societal problems that call for societal and governmental solutions, and not only at the local level but from coast to coast.

The remainder of this easy to read and follow text provides many rich resources for the deliverers of mental health care. (e.g., plan-do-act, standard work, and A3 thinking).

The closing section focuses on leadership and culture – often overlooked to the detriment of any organization that doesn’t pay close attention to supporting both. Culture is cultivated and nourished by the organization’s leaders. Culture empowers staff to become problem solvers and agents of improvement. Empowered staff support and enrich their culture. Together a workplace that brings out the best of all its people is created, and burnout is held at bay.

“Transforming Mental Healthcare: Applying Performance Improvement Methods to Mental Healthcare” is a welcome and essential addition to the current morass, which is our mental health care delivery system, an oasis in the desert from which perhaps the lotus flower can emerge.

Dr. Merlino is emeritus professor of psychiatry, SUNY Downstate College of Medicine, Rhinebeck, N.Y., and formerly director of psychiatry at Kings County Hospital Center, Brooklyn, NY. He is the coauthor of “Lean Behavioral Health: The Kings County Hospital Story.” .

What is palliative care and what’s new in practicing this type of medicine?

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.”1

The common misperception is that palliative care is only for those at end of life or only in the advanced stages of their illness. However, palliative care is ideally most helpful following individuals from diagnosis through their illness trajectory. Another misperception is that palliative care and hospice are the same thing. Though all hospice is palliative care, all palliative care is not hospice. Both palliative care and hospice provide care for individuals facing a serious illness and focus on the same philosophy of care, but palliative care can be initiated at any stage of illness, even if the goal is to pursue curative and life-prolonging therapies/interventions.

In contrast, hospice is considered for those who are at the end of life and are usually not pursuing life-prolonging therapies or interventions, instead focusing on comfort, symptom management, and optimization of quality of life.

Though there is a growing need for palliative care, there is a shortage of specialist palliative care providers. Much of the palliative care needs can be met by all providers who can offer basic symptom management, identification surrounding goals of care and discussions of advance care planning, and understanding of illness/prognosis and treatment options, which is called primary palliative care.2 In fact, two-thirds of patients with a serious illness other than cancer prefer discussion of end-of-life care or advance care planning with their primary care providers.3

Referral to specialty palliative care should be considered when there are more complexities to symptom/pain management and goals of care/end of life, transition to hospice, or complex communication dynamics.4

Though specialty palliative care was shown to be more comprehensive, both primary palliative care and specialty palliative care have led to improvements in the quality of life in individuals living with serious illness.5 Early integration of palliative care into routine care has been shown to improve symptom burden, mood, quality of life, survival, and health care costs.6

Updates in alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care

There are several alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care, including cannabis and psychedelics. These therapies are becoming or may become a familiar part of medical therapies that are listed in a patient’s history as part of their medical regimen, especially as more states continue to legalize and/or decriminalize the use of these alternative therapies for recreational or medicinal use.

Both cannabis and psychedelics have a longstanding history of therapeutic and holistic use. Cannabis has been used to manage symptoms such as pain since the 16th and 17th century.7 In palliative care, more patients may turn to various forms of cannabis as a source of relief from symptoms and suffering as their focus shifts more to quality of life.

Even with the increasing popularity of the use of cannabis among seriously ill patients, there is still a lack of evidence of the benefits of medical cannabis use in palliative care, and there is a lack of standardization of type of cannabis used and state regulations regarding their use.7

A recent systematic review found that despite the reported positive treatment effects of cannabis in palliative care, the results of the studies were conflicting. This highlights the need for further high-quality research to determine whether cannabis products are an effective treatment in palliative care patients.8

One limitation to note is that the majority of the included studies focused on cannabis use in patients with cancer for cancer-related symptoms. Few studies included patients with other serious conditions.

Psychedelics

There is evidence that psychedelic assisted therapy (PAT) is a safe and effective treatment for individuals with refractory depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder.9 Plus, there have been ample studies providing support that PAT improves symptoms such as refractory anxiety/depression, demoralization, and existential distress in seriously ill patients, thus improving their quality of life and overall well-being.9

Nine U.S. cities and the State of Oregon have decriminalized or legalized the psychedelic psilocybin, based on the medical benefits patients have experienced evidenced from using it.10

In light of the increasing interest in PAT, Dr. Ira Byock provided the following points on what “all clinicians should know as they enter this uncharted territory”:

- Psychedelics have been around for a long time.

- Psychedelic-assisted therapies’ therapeutic effects are experiential.

- There are a variety of terms for specific categories of psychedelic compounds.

- Some palliative care teams are already caring for patients who undergo psychedelic experiences.

- Use of psychedelics should be well-observed by a skilled clinician with expertise.

I am hoping this provides a general refresher on palliative care and an overview of updates to alternative and complementary therapies for patients living with serious illness.9

Dr. Kang is a geriatrician and palliative care provider at the University of Washington, Seattle in the division of geriatrics and gerontology. She has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2020 Aug 5..

2. Weissman DE and Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting a consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

3. Sherry D et al. Is primary care physician involvement associated with earlier advance care planning? A study of patients in an academic primary care setting. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(1):75-80.

4. Quill TE and Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173-75.

5. Ernecoff NC et al. Comparing specialty and primary palliative care interventions: Analysis of a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(3):389-96.

6. Temmel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;363:733-42.

7. Kogan M and Sexton M. Medical cannabis: A new old tool for palliative care. J Altern Complement Med . 2020 Sep;26(9):776-8.

8. Doppen M et al. Cannabis in palliative care: A systematic review of the current evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022 Jun 12;S0885-3924(22)00760-6.

9. Byock I. Psychedelics for serious illness: Five things clinicians need to know. The Center to Advance Palliative Care. Psychedelics for Serious Illness, Palliative in Practice, Center to Advance Palliative Care (capc.org). June 13, 2022.

10. Marks M. A strategy for rescheduling psilocybin. Scientific American. Oct. 11, 2021.

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.”1

The common misperception is that palliative care is only for those at end of life or only in the advanced stages of their illness. However, palliative care is ideally most helpful following individuals from diagnosis through their illness trajectory. Another misperception is that palliative care and hospice are the same thing. Though all hospice is palliative care, all palliative care is not hospice. Both palliative care and hospice provide care for individuals facing a serious illness and focus on the same philosophy of care, but palliative care can be initiated at any stage of illness, even if the goal is to pursue curative and life-prolonging therapies/interventions.

In contrast, hospice is considered for those who are at the end of life and are usually not pursuing life-prolonging therapies or interventions, instead focusing on comfort, symptom management, and optimization of quality of life.

Though there is a growing need for palliative care, there is a shortage of specialist palliative care providers. Much of the palliative care needs can be met by all providers who can offer basic symptom management, identification surrounding goals of care and discussions of advance care planning, and understanding of illness/prognosis and treatment options, which is called primary palliative care.2 In fact, two-thirds of patients with a serious illness other than cancer prefer discussion of end-of-life care or advance care planning with their primary care providers.3

Referral to specialty palliative care should be considered when there are more complexities to symptom/pain management and goals of care/end of life, transition to hospice, or complex communication dynamics.4

Though specialty palliative care was shown to be more comprehensive, both primary palliative care and specialty palliative care have led to improvements in the quality of life in individuals living with serious illness.5 Early integration of palliative care into routine care has been shown to improve symptom burden, mood, quality of life, survival, and health care costs.6

Updates in alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care

There are several alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care, including cannabis and psychedelics. These therapies are becoming or may become a familiar part of medical therapies that are listed in a patient’s history as part of their medical regimen, especially as more states continue to legalize and/or decriminalize the use of these alternative therapies for recreational or medicinal use.

Both cannabis and psychedelics have a longstanding history of therapeutic and holistic use. Cannabis has been used to manage symptoms such as pain since the 16th and 17th century.7 In palliative care, more patients may turn to various forms of cannabis as a source of relief from symptoms and suffering as their focus shifts more to quality of life.

Even with the increasing popularity of the use of cannabis among seriously ill patients, there is still a lack of evidence of the benefits of medical cannabis use in palliative care, and there is a lack of standardization of type of cannabis used and state regulations regarding their use.7

A recent systematic review found that despite the reported positive treatment effects of cannabis in palliative care, the results of the studies were conflicting. This highlights the need for further high-quality research to determine whether cannabis products are an effective treatment in palliative care patients.8

One limitation to note is that the majority of the included studies focused on cannabis use in patients with cancer for cancer-related symptoms. Few studies included patients with other serious conditions.

Psychedelics

There is evidence that psychedelic assisted therapy (PAT) is a safe and effective treatment for individuals with refractory depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder.9 Plus, there have been ample studies providing support that PAT improves symptoms such as refractory anxiety/depression, demoralization, and existential distress in seriously ill patients, thus improving their quality of life and overall well-being.9

Nine U.S. cities and the State of Oregon have decriminalized or legalized the psychedelic psilocybin, based on the medical benefits patients have experienced evidenced from using it.10

In light of the increasing interest in PAT, Dr. Ira Byock provided the following points on what “all clinicians should know as they enter this uncharted territory”:

- Psychedelics have been around for a long time.

- Psychedelic-assisted therapies’ therapeutic effects are experiential.

- There are a variety of terms for specific categories of psychedelic compounds.

- Some palliative care teams are already caring for patients who undergo psychedelic experiences.

- Use of psychedelics should be well-observed by a skilled clinician with expertise.

I am hoping this provides a general refresher on palliative care and an overview of updates to alternative and complementary therapies for patients living with serious illness.9

Dr. Kang is a geriatrician and palliative care provider at the University of Washington, Seattle in the division of geriatrics and gerontology. She has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2020 Aug 5..

2. Weissman DE and Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting a consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

3. Sherry D et al. Is primary care physician involvement associated with earlier advance care planning? A study of patients in an academic primary care setting. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(1):75-80.

4. Quill TE and Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173-75.

5. Ernecoff NC et al. Comparing specialty and primary palliative care interventions: Analysis of a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(3):389-96.

6. Temmel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;363:733-42.

7. Kogan M and Sexton M. Medical cannabis: A new old tool for palliative care. J Altern Complement Med . 2020 Sep;26(9):776-8.

8. Doppen M et al. Cannabis in palliative care: A systematic review of the current evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022 Jun 12;S0885-3924(22)00760-6.

9. Byock I. Psychedelics for serious illness: Five things clinicians need to know. The Center to Advance Palliative Care. Psychedelics for Serious Illness, Palliative in Practice, Center to Advance Palliative Care (capc.org). June 13, 2022.

10. Marks M. A strategy for rescheduling psilocybin. Scientific American. Oct. 11, 2021.

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual.”1

The common misperception is that palliative care is only for those at end of life or only in the advanced stages of their illness. However, palliative care is ideally most helpful following individuals from diagnosis through their illness trajectory. Another misperception is that palliative care and hospice are the same thing. Though all hospice is palliative care, all palliative care is not hospice. Both palliative care and hospice provide care for individuals facing a serious illness and focus on the same philosophy of care, but palliative care can be initiated at any stage of illness, even if the goal is to pursue curative and life-prolonging therapies/interventions.

In contrast, hospice is considered for those who are at the end of life and are usually not pursuing life-prolonging therapies or interventions, instead focusing on comfort, symptom management, and optimization of quality of life.

Though there is a growing need for palliative care, there is a shortage of specialist palliative care providers. Much of the palliative care needs can be met by all providers who can offer basic symptom management, identification surrounding goals of care and discussions of advance care planning, and understanding of illness/prognosis and treatment options, which is called primary palliative care.2 In fact, two-thirds of patients with a serious illness other than cancer prefer discussion of end-of-life care or advance care planning with their primary care providers.3

Referral to specialty palliative care should be considered when there are more complexities to symptom/pain management and goals of care/end of life, transition to hospice, or complex communication dynamics.4

Though specialty palliative care was shown to be more comprehensive, both primary palliative care and specialty palliative care have led to improvements in the quality of life in individuals living with serious illness.5 Early integration of palliative care into routine care has been shown to improve symptom burden, mood, quality of life, survival, and health care costs.6

Updates in alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care

There are several alternative and complementary therapies to palliative care, including cannabis and psychedelics. These therapies are becoming or may become a familiar part of medical therapies that are listed in a patient’s history as part of their medical regimen, especially as more states continue to legalize and/or decriminalize the use of these alternative therapies for recreational or medicinal use.

Both cannabis and psychedelics have a longstanding history of therapeutic and holistic use. Cannabis has been used to manage symptoms such as pain since the 16th and 17th century.7 In palliative care, more patients may turn to various forms of cannabis as a source of relief from symptoms and suffering as their focus shifts more to quality of life.

Even with the increasing popularity of the use of cannabis among seriously ill patients, there is still a lack of evidence of the benefits of medical cannabis use in palliative care, and there is a lack of standardization of type of cannabis used and state regulations regarding their use.7

A recent systematic review found that despite the reported positive treatment effects of cannabis in palliative care, the results of the studies were conflicting. This highlights the need for further high-quality research to determine whether cannabis products are an effective treatment in palliative care patients.8

One limitation to note is that the majority of the included studies focused on cannabis use in patients with cancer for cancer-related symptoms. Few studies included patients with other serious conditions.

Psychedelics

There is evidence that psychedelic assisted therapy (PAT) is a safe and effective treatment for individuals with refractory depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorder.9 Plus, there have been ample studies providing support that PAT improves symptoms such as refractory anxiety/depression, demoralization, and existential distress in seriously ill patients, thus improving their quality of life and overall well-being.9

Nine U.S. cities and the State of Oregon have decriminalized or legalized the psychedelic psilocybin, based on the medical benefits patients have experienced evidenced from using it.10

In light of the increasing interest in PAT, Dr. Ira Byock provided the following points on what “all clinicians should know as they enter this uncharted territory”:

- Psychedelics have been around for a long time.

- Psychedelic-assisted therapies’ therapeutic effects are experiential.

- There are a variety of terms for specific categories of psychedelic compounds.

- Some palliative care teams are already caring for patients who undergo psychedelic experiences.

- Use of psychedelics should be well-observed by a skilled clinician with expertise.

I am hoping this provides a general refresher on palliative care and an overview of updates to alternative and complementary therapies for patients living with serious illness.9

Dr. Kang is a geriatrician and palliative care provider at the University of Washington, Seattle in the division of geriatrics and gerontology. She has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

References

1. World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2020 Aug 5..

2. Weissman DE and Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting a consensus report from the center to advance palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

3. Sherry D et al. Is primary care physician involvement associated with earlier advance care planning? A study of patients in an academic primary care setting. J Palliat Med. 2022;25(1):75-80.

4. Quill TE and Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173-75.

5. Ernecoff NC et al. Comparing specialty and primary palliative care interventions: Analysis of a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(3):389-96.

6. Temmel JS et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;363:733-42.

7. Kogan M and Sexton M. Medical cannabis: A new old tool for palliative care. J Altern Complement Med . 2020 Sep;26(9):776-8.

8. Doppen M et al. Cannabis in palliative care: A systematic review of the current evidence. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022 Jun 12;S0885-3924(22)00760-6.

9. Byock I. Psychedelics for serious illness: Five things clinicians need to know. The Center to Advance Palliative Care. Psychedelics for Serious Illness, Palliative in Practice, Center to Advance Palliative Care (capc.org). June 13, 2022.

10. Marks M. A strategy for rescheduling psilocybin. Scientific American. Oct. 11, 2021.

Caring for the young elite athlete

Concerns about the potential harm resulting from overzealous training regimens and performance schedules for young elite athletes seems to come in cycles much like the Olympics. But, more recently, the media attention has become more intense fueled by the very visible psychological vulnerabilities of some young gymnasts, tennis players, and figure skaters. Accusations of physical and psychological abuse by team physicians and coaches continue to surface with troubling regularity.

A recent article in the Wall St. Journal explores a variety of initiatives aimed at redefining the relationship between youth sports and the physical and mental health of its elite athletes. (Louise Radnofsky, The Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2022).

An example of the new awareness is the recent invitation of Peter Donnelly, PhD, an emeritus professor at the University of Toronto and long-time advocate for regulatory protections for youth athletes, to deliver a paper at a global conference in South Africa devoted to the elimination of child labor. Referring to youth sports, Dr. Donnelly observes “What if McDonalds had the same accident rate? ... There would be huge commissions of inquiry, regulations, and policies.” He suggests that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child might be a mechanism to address the problem.

Writing in the Marquette University Sports Law Review in 2015, Kristin Hoffman, a law student at the time, suggested that the federal Fair Labor Standards Act or state child labor laws could be used to restructure sports like gymnastics or figure skating with tarnished histories. California law prohibits child actors from working more than 5 hours a day on school days and 7 hours on nonschool days but says little about child athletes. On paper, the National Collegiate Athletic Association limits college athletes to 20 hours participation per week but teenagers on club teams are not limited and may sometimes practice 30 hours or more.

Regulation in any form is a tough sell in this country. Coaches, parents, and athletes caught up in the myth that more repetitions and more touches on the ball are always the ticket to success will argue that most elite athletes are self-motivated and don’t view the long hours as a hardship.

Exactly how many are self-driven and how many are being pushed by parents and coaches is unknown. Across the street from us lived a young girl who, despite not having the obvious physical gifts, was clearly committed to excel in sports. She begged her parents to set up lights to allow her to practice well into the evening. She went on to have a good college career as a player and a very successful career as a Division I coach. Now in retirement, she is very open about her mental health history that in large part explains her inner drive and her subsequent troubles.

We need to be realistic in our hope for regulating the current state of youth sports out of its current situation. State laws that put reasonable limits on the hourly commitment to sports much like the California child actor laws feel like a reasonable goal. However, as physicians for these young athletes we must take each child – and we must remind ourselves that they are still children – as an individual.

When faced with patients who are clearly on the elite sport pathway, our goal is to protect their health – both physical and mental. If they are having symptoms of overuse we need to help them find alternative activities that will rest their injuries but still allow them to satisfy their competitive zeal. However, we must be ever alert to the risk that what appears to be unusual self-motivation may be instead a warning that pathologic obsession and compulsion lurk below the surface.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Concerns about the potential harm resulting from overzealous training regimens and performance schedules for young elite athletes seems to come in cycles much like the Olympics. But, more recently, the media attention has become more intense fueled by the very visible psychological vulnerabilities of some young gymnasts, tennis players, and figure skaters. Accusations of physical and psychological abuse by team physicians and coaches continue to surface with troubling regularity.

A recent article in the Wall St. Journal explores a variety of initiatives aimed at redefining the relationship between youth sports and the physical and mental health of its elite athletes. (Louise Radnofsky, The Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2022).

An example of the new awareness is the recent invitation of Peter Donnelly, PhD, an emeritus professor at the University of Toronto and long-time advocate for regulatory protections for youth athletes, to deliver a paper at a global conference in South Africa devoted to the elimination of child labor. Referring to youth sports, Dr. Donnelly observes “What if McDonalds had the same accident rate? ... There would be huge commissions of inquiry, regulations, and policies.” He suggests that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child might be a mechanism to address the problem.

Writing in the Marquette University Sports Law Review in 2015, Kristin Hoffman, a law student at the time, suggested that the federal Fair Labor Standards Act or state child labor laws could be used to restructure sports like gymnastics or figure skating with tarnished histories. California law prohibits child actors from working more than 5 hours a day on school days and 7 hours on nonschool days but says little about child athletes. On paper, the National Collegiate Athletic Association limits college athletes to 20 hours participation per week but teenagers on club teams are not limited and may sometimes practice 30 hours or more.

Regulation in any form is a tough sell in this country. Coaches, parents, and athletes caught up in the myth that more repetitions and more touches on the ball are always the ticket to success will argue that most elite athletes are self-motivated and don’t view the long hours as a hardship.

Exactly how many are self-driven and how many are being pushed by parents and coaches is unknown. Across the street from us lived a young girl who, despite not having the obvious physical gifts, was clearly committed to excel in sports. She begged her parents to set up lights to allow her to practice well into the evening. She went on to have a good college career as a player and a very successful career as a Division I coach. Now in retirement, she is very open about her mental health history that in large part explains her inner drive and her subsequent troubles.

We need to be realistic in our hope for regulating the current state of youth sports out of its current situation. State laws that put reasonable limits on the hourly commitment to sports much like the California child actor laws feel like a reasonable goal. However, as physicians for these young athletes we must take each child – and we must remind ourselves that they are still children – as an individual.

When faced with patients who are clearly on the elite sport pathway, our goal is to protect their health – both physical and mental. If they are having symptoms of overuse we need to help them find alternative activities that will rest their injuries but still allow them to satisfy their competitive zeal. However, we must be ever alert to the risk that what appears to be unusual self-motivation may be instead a warning that pathologic obsession and compulsion lurk below the surface.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Concerns about the potential harm resulting from overzealous training regimens and performance schedules for young elite athletes seems to come in cycles much like the Olympics. But, more recently, the media attention has become more intense fueled by the very visible psychological vulnerabilities of some young gymnasts, tennis players, and figure skaters. Accusations of physical and psychological abuse by team physicians and coaches continue to surface with troubling regularity.

A recent article in the Wall St. Journal explores a variety of initiatives aimed at redefining the relationship between youth sports and the physical and mental health of its elite athletes. (Louise Radnofsky, The Wall Street Journal, June 9, 2022).

An example of the new awareness is the recent invitation of Peter Donnelly, PhD, an emeritus professor at the University of Toronto and long-time advocate for regulatory protections for youth athletes, to deliver a paper at a global conference in South Africa devoted to the elimination of child labor. Referring to youth sports, Dr. Donnelly observes “What if McDonalds had the same accident rate? ... There would be huge commissions of inquiry, regulations, and policies.” He suggests that the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child might be a mechanism to address the problem.

Writing in the Marquette University Sports Law Review in 2015, Kristin Hoffman, a law student at the time, suggested that the federal Fair Labor Standards Act or state child labor laws could be used to restructure sports like gymnastics or figure skating with tarnished histories. California law prohibits child actors from working more than 5 hours a day on school days and 7 hours on nonschool days but says little about child athletes. On paper, the National Collegiate Athletic Association limits college athletes to 20 hours participation per week but teenagers on club teams are not limited and may sometimes practice 30 hours or more.

Regulation in any form is a tough sell in this country. Coaches, parents, and athletes caught up in the myth that more repetitions and more touches on the ball are always the ticket to success will argue that most elite athletes are self-motivated and don’t view the long hours as a hardship.

Exactly how many are self-driven and how many are being pushed by parents and coaches is unknown. Across the street from us lived a young girl who, despite not having the obvious physical gifts, was clearly committed to excel in sports. She begged her parents to set up lights to allow her to practice well into the evening. She went on to have a good college career as a player and a very successful career as a Division I coach. Now in retirement, she is very open about her mental health history that in large part explains her inner drive and her subsequent troubles.

We need to be realistic in our hope for regulating the current state of youth sports out of its current situation. State laws that put reasonable limits on the hourly commitment to sports much like the California child actor laws feel like a reasonable goal. However, as physicians for these young athletes we must take each child – and we must remind ourselves that they are still children – as an individual.

When faced with patients who are clearly on the elite sport pathway, our goal is to protect their health – both physical and mental. If they are having symptoms of overuse we need to help them find alternative activities that will rest their injuries but still allow them to satisfy their competitive zeal. However, we must be ever alert to the risk that what appears to be unusual self-motivation may be instead a warning that pathologic obsession and compulsion lurk below the surface.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

The mother’s double jeopardy

Jamestown, Colo., is a small mountain town several miles up through Lefthand Canyon out of Boulder, in the Rocky Mountains. The canyon roads are steep, winding, and narrow, and peopled by brightly clad cyclists struggling up the hill and flying down faster than the cars. The road through Jamestown is dusty in the summer with brightly colored oil barrels strategically placed in the middle of the single road through town. Slashed across their sides: “SLOW DOWN! Watch out for our feral children!”

Wild child or hothouse child? What is the best choice? Women bear the brunt of this deciding, whether they are working outside of the home, or stay-at-home caregivers, or both. Women know they will be blamed if they get it wrong.

Society has exacted a tall order on women who choose to have children. Patriarchal norms ask (White) women who choose both to work and have children, if they are really a “stay-at-home” mother who must work, or a “working” mother who prefers work over their children. The underlying attitude can be read as: “Are you someone who prioritizes paid work over caregiving, or are you someone who prioritizes caregiving over work?” You may be seen as a bad mother if you prioritize work over the welfare of your child. If you prioritize your child over your work, then you are not a reliable, dedicated worker. The working mother can’t win.

Woman’s central question is what kind of mother should I be? Mothers struggle with this question all their lives; when their child has difficulties, society’s question is what did you do wrong with your child? Mothers internalize the standard of the “good mother” and are aware of each minor transgression that depicts them as the “bad mother.” It is hard to escape the impossible perfectionistic standard of the good mother. But perhaps it has come time to push back on the moral imbalance.

Internalized sexism

As women move out of the home into the workplace, the societal pressures to maintain the status quo bear down on women, trying to keep them in their place.

Social pressures employ subtle “technologies of the self,” so that women – as any oppressed group – learn to internalize these technologies, and monitor themselves.1 This is now widely accepted as internalized sexism, whereby women feel that they are not good enough, do not have the right qualifications, and are “less” than the dominant group (men). This phenomenon is also recognized when racial and ethnic biases are assimilated unconsciously, as internalized racism. Should we also have internalized “momism”?

Women are caught between trying to claim their individualism as well as feeling the responsibility to be the self-denying mother. Everyone has an opinion about the place of women. Conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly considered “women’s lib” to be un-American, citing women in the military and the establishment of federal day care centers as actions of a communist state. A similar ideology helped form the antifeminist organization Concerned Women for America, which self-reports that it is the largest American public policy women’s organization. Formed in opposition to the National Organization for Women, CWA is focused on maintaining the traditional family, as understood by (White) evangelical Christians.

An example similar to CWA is the Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. It was established to help evangelical Christian churches defend themselves against an accommodation of secular feminism and also against evangelical feminism (which pushes for more equality in the church). It promotes complementarianism – the idea that masculinity and femininity are ordained by God and that men and women are created to complement each other.

At the other extreme, the most radical of feminists believe in the need to create a women-only society where women would be free from the patriarchy. Less angry but decidedly weirder are the feminists called “FEMEN” who once staged a protest at the Vatican where topless women feigned intercourse with crucifixes, chanting slogans against the pope and religion.

Most women tread a path between extremes, a path which is difficult and lonely. Without a firm ideology, this path is strewn with doubts and pitfalls. Some career-oriented women who have delayed motherhood, knowing that they will soon be biologically past their peak and possibly also without a partner, wonder if they should become single mothers using sperm donation. For many women, the workplace does not offer much help with maternity leave or childcare. Even when maternity leave is available, there is a still a lack of understanding about what is needed.

“Think of it as caregiver bias. If you just extend maternity leave, what is implied is that you’re still expecting me to be the primary source of care for my child, when in fact my partner wants to share the load and will need support to do so as well,” said Pamela Culpepper, an expert in corporate diversity and inclusion.2

Intensive mothering

When the glamor of the workplace wears off and/or when the misogyny and the harassment become too much, women who have the financial stability may decide to return to the role of the stay-at-home mother. Perhaps, in the home, she can feel fulfilled. Yet, young American urban and suburban mothers now parent under a new name – “intensive mothering.”

Conducting in-depth interviews of 38 women of diverse backgrounds in the United States, Sharon Hays found women describing their 2- to 4-year-old children as innocent and priceless, and believing that they – the mothers – should be primarily responsible for rearing their children, using “child-rearing methods that are child centered, expert guided, emotionally absorbing, labor intensive, and financially expensive.”3 Ms. Hays clarified four beliefs that were common to all the women in the study: mothers are more suitable caregivers than fathers; mothering should be child centered; parenting consists of a set of skills that need to be learned; and parenting is labor-intensive but an emotionally fulfilling activity.

Hays wondered if this type of mothering developed as the last defense against “the impoverishment of social ties, communal obligations and unremunerated commitments.”3 She suggested that women succumbing to social pressures to return to the home is yet another example of how society is set up to benefit men, capitalism, political leaders, and those who try to maintain a “traditional” form of family life.3 Ms. Hays concluded that the practice of intensive mothering is a class-based practice of privileged white women, entangled with capitalism in that the buying of “essential” baby products is equated with good mothering. She found this ideology to be oppressive of all women, regardless of their social class, ethnic background, household composition, and financial situation. Ms. Hays noted that many women experience guilt for not matching up to these ideals.

In “Dead End Feminism,” Elisabeth Badinter asks if the upheaval in the role of women has caused so much uncertainty that it is easier for women to regress to a time when they were in the home and knew themselves as mothers. They ask if this has been reinforced by the movement to embrace all things natural, eschewing the falseness of chemicals and other things that threaten Mother Earth.4

There is no escaping the power of the mother: she will continue to symbolize all that is good and bad as the embodiment of the Mother Archetype. All of this is the background against which you will see the new mother in the family. She will not articulate her dilemma, that is your role as the family psychiatrist.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (New York: Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Contact Dr. Heru at alison.heru@ucdenver.edu.

References

1. Martin LH et al (eds.). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. University of Massachusetts Press: Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press, 2022.

2. How Pamela Culpepper Is Changing The Narrative Of Women In The Workplace. Huffpost. 2020 Mar 6. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/pamela-culpepper-diversity-inclusion-empowerment_n_5e56b6ffc5b62e9dc7dbc307.

3. Hays S. Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. Yale University Press: New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1996.

4. Badinter E. (translated by Borossa J). Dead End Feminism. Malden, Mass.: Polity Press, 2006.

Jamestown, Colo., is a small mountain town several miles up through Lefthand Canyon out of Boulder, in the Rocky Mountains. The canyon roads are steep, winding, and narrow, and peopled by brightly clad cyclists struggling up the hill and flying down faster than the cars. The road through Jamestown is dusty in the summer with brightly colored oil barrels strategically placed in the middle of the single road through town. Slashed across their sides: “SLOW DOWN! Watch out for our feral children!”

Wild child or hothouse child? What is the best choice? Women bear the brunt of this deciding, whether they are working outside of the home, or stay-at-home caregivers, or both. Women know they will be blamed if they get it wrong.

Society has exacted a tall order on women who choose to have children. Patriarchal norms ask (White) women who choose both to work and have children, if they are really a “stay-at-home” mother who must work, or a “working” mother who prefers work over their children. The underlying attitude can be read as: “Are you someone who prioritizes paid work over caregiving, or are you someone who prioritizes caregiving over work?” You may be seen as a bad mother if you prioritize work over the welfare of your child. If you prioritize your child over your work, then you are not a reliable, dedicated worker. The working mother can’t win.