User login

Ob.gyns. on the day that Roe v. Wade was overturned

“I’m happy to contribute, but can you keep it anonymous? It’s a safety concern for me.”

On the day that the Supreme Court of the United States voted to strike down Roe v. Wade, I reached out to ob.gyn.s across the country, wanting to hear their reactions. My own response, like that of many doctors and women, was a visceral mix of anger, fear, and grief. I could only begin to imagine what the real experts on reproductive health care were going through.

When the first ob.gyn. responded to my request by expressing concerns around anonymity and personal safety, I was shocked – but I shouldn’t have been. For starters, there is already a storied history in this country of deadly attacks on abortion providers. David Gunn, MD; Barnett Slepian, MD; and George Tiller, MD, were all tragically murdered by antiabortion extremists. Then, there’s the existence of websites that keep logs of abortion providers and sometimes include photos, office contact information, or even home addresses.

The idea that any reproductive health care provider should have to think twice before offering their uniquely qualified opinion is profoundly disturbing, nearly as disturbing as the Supreme Court’s decision itself. But it’s more critical than ever for ob.gyn. voices to be amplified. This is the time for the healthcare community to rally around women’s health providers, to learn from them, to support them.

I asked ob.gyns. around the country to tell me what they were thinking and feeling on the day that Roe v. Wade was overturned. We agreed to keep the responses anonymous, given that several people expressed very understandable safety concerns.

Here’s what they had to say.

Tennessee ob.gyn.

“Today is an emotionally charged day for many people in this country, yet as I type this, with my ob.gyn. practice continuing around me, with my own almost 10-week pregnancy growing inside me, I feel quite blunted. I feel powerless to answer questions that are variations on ‘what next?’ or ‘how do we fight back?’ All I can think of is, I am so glad I do not have anyone on my schedule right now who does not want to be pregnant. But what will happen when that eventually changes? What about my colleagues who do have these patients on their schedules today? On a personal level, what if my prenatal genetic testing comes back abnormal? How can we so blatantly disregard a separation of church and state in this country? What ways will our government interfere with my practice next? My head is spinning, but I have to go see my next patient. She is a 25-year-old who is here to have an IUD placed, and that seems like the most important thing I can do today.”

South Carolina ob.gyn.

“I’m really scared. For my patients and for myself. I don’t know how to be a good ob.gyn. if my ability to offer safe and accessible abortion care is being threatened.”

Massachusetts ob.gyn.

“Livid and devastated and sad and terrified.”

California family planning specialist

“The fact is that about one in four people with uteruses have had an abortion. I can’t tell you how many abortions I’ve provided for people who say that they don’t ‘believe’ in them or that they thought they’d never be in this situation. ... The fact is that pregnancy is a life-threatening condition in and of itself. I am an ob.gyn., a medical doctor, and an abortion provider. I will not stop providing abortions or helping people access them. I will dedicate my life to ensuring this right to bodily autonomy. Today I am devastated by the Supreme Court’s decision to force parenthood that will result in increased maternal mortality. I am broken, but I have never been more proud to be an abortion provider.”

New York ob.gyn.

“Grateful to live in a state and work for a hospital where I can provide abortions but feel terrible for so many people less fortunate and underserved.”

Illinois maternal-fetal medicine specialist

“As a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, I fear for my patients who are at the highest risk of pregnancy complications having their freedom taken away. For the tragic ultrasound findings that make a pregnant person carry a baby who will never live. For the patients who cannot use most forms of contraception because of their medical comorbidities. For the patients who are victims of intimate partner violence or under the influence of their culture, to continue having children regardless of their desires or their health. ... The freedom to prevent or end a pregnancy has enabled women to become independent and productive members of society on their own terms, with or without children. My heart breaks for the children and adolescents and adults who are being told they are second-class citizens, not worthy of making their own decisions. Politicians and Supreme Court justices are not in the clinic room, ultrasound suite, operating room, or delivery room when we have these intense conversations and pregnancy outcomes. They have no idea that of which they speak, and it’s unconscionable that they can determine what healthcare decisions my patients can make for their own lives. Nobody knows a body better than the patient themselves.”

Texas ob.gyn.

“In the area where I live and practice, it feels like guns and the people who use them have more legal rights than people with uteruses in desperate or life-threatening situations. I’m afraid for my personal safety as a women’s health practitioner in this political climate. I feel helpless, but I’m supposed to be able to help my patients.”

Missouri family planning specialist

“Abortion is an essential part of healthcare, and the only people that should get a say in it are the patient and their doctor. Period. The fact that some far-off court without any medical expertise can insert itself into individual medical decisions is oppressive and unethical.”

Georgia ob.gyn.

“I can’t even think straight right now. I feel sick. Honestly, I’ve been thinking about moving for a long time now. Somewhere where I would actually be able to offer good, comprehensive care.”

New York ob.gyn.

“I graduated from my ob.gyn. residency hours after the Roe v. Wade news broke. It was so emotional for me. I’ve dedicated my life to caring for people with uteruses and I will not let this heartbreaking news change that. I feel more committed than ever to women’s health. I fully plan to continue delivering babies, providing contraception, and performing abortions. I will be there to help women with desired pregnancies who received unspeakably bad news about fetal anomalies. I will be there to help women with life-threatening pregnancy complications before fetal viability. I will be there to help women with ectopic pregnancies. I will be there to help women who were raped or otherwise forced into pregnancy. I will always be there to help women.”

Dr. Croll is a neurovascular fellow at New York University Langone Health. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I’m happy to contribute, but can you keep it anonymous? It’s a safety concern for me.”

On the day that the Supreme Court of the United States voted to strike down Roe v. Wade, I reached out to ob.gyn.s across the country, wanting to hear their reactions. My own response, like that of many doctors and women, was a visceral mix of anger, fear, and grief. I could only begin to imagine what the real experts on reproductive health care were going through.

When the first ob.gyn. responded to my request by expressing concerns around anonymity and personal safety, I was shocked – but I shouldn’t have been. For starters, there is already a storied history in this country of deadly attacks on abortion providers. David Gunn, MD; Barnett Slepian, MD; and George Tiller, MD, were all tragically murdered by antiabortion extremists. Then, there’s the existence of websites that keep logs of abortion providers and sometimes include photos, office contact information, or even home addresses.

The idea that any reproductive health care provider should have to think twice before offering their uniquely qualified opinion is profoundly disturbing, nearly as disturbing as the Supreme Court’s decision itself. But it’s more critical than ever for ob.gyn. voices to be amplified. This is the time for the healthcare community to rally around women’s health providers, to learn from them, to support them.

I asked ob.gyns. around the country to tell me what they were thinking and feeling on the day that Roe v. Wade was overturned. We agreed to keep the responses anonymous, given that several people expressed very understandable safety concerns.

Here’s what they had to say.

Tennessee ob.gyn.

“Today is an emotionally charged day for many people in this country, yet as I type this, with my ob.gyn. practice continuing around me, with my own almost 10-week pregnancy growing inside me, I feel quite blunted. I feel powerless to answer questions that are variations on ‘what next?’ or ‘how do we fight back?’ All I can think of is, I am so glad I do not have anyone on my schedule right now who does not want to be pregnant. But what will happen when that eventually changes? What about my colleagues who do have these patients on their schedules today? On a personal level, what if my prenatal genetic testing comes back abnormal? How can we so blatantly disregard a separation of church and state in this country? What ways will our government interfere with my practice next? My head is spinning, but I have to go see my next patient. She is a 25-year-old who is here to have an IUD placed, and that seems like the most important thing I can do today.”

South Carolina ob.gyn.

“I’m really scared. For my patients and for myself. I don’t know how to be a good ob.gyn. if my ability to offer safe and accessible abortion care is being threatened.”

Massachusetts ob.gyn.

“Livid and devastated and sad and terrified.”

California family planning specialist

“The fact is that about one in four people with uteruses have had an abortion. I can’t tell you how many abortions I’ve provided for people who say that they don’t ‘believe’ in them or that they thought they’d never be in this situation. ... The fact is that pregnancy is a life-threatening condition in and of itself. I am an ob.gyn., a medical doctor, and an abortion provider. I will not stop providing abortions or helping people access them. I will dedicate my life to ensuring this right to bodily autonomy. Today I am devastated by the Supreme Court’s decision to force parenthood that will result in increased maternal mortality. I am broken, but I have never been more proud to be an abortion provider.”

New York ob.gyn.

“Grateful to live in a state and work for a hospital where I can provide abortions but feel terrible for so many people less fortunate and underserved.”

Illinois maternal-fetal medicine specialist

“As a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, I fear for my patients who are at the highest risk of pregnancy complications having their freedom taken away. For the tragic ultrasound findings that make a pregnant person carry a baby who will never live. For the patients who cannot use most forms of contraception because of their medical comorbidities. For the patients who are victims of intimate partner violence or under the influence of their culture, to continue having children regardless of their desires or their health. ... The freedom to prevent or end a pregnancy has enabled women to become independent and productive members of society on their own terms, with or without children. My heart breaks for the children and adolescents and adults who are being told they are second-class citizens, not worthy of making their own decisions. Politicians and Supreme Court justices are not in the clinic room, ultrasound suite, operating room, or delivery room when we have these intense conversations and pregnancy outcomes. They have no idea that of which they speak, and it’s unconscionable that they can determine what healthcare decisions my patients can make for their own lives. Nobody knows a body better than the patient themselves.”

Texas ob.gyn.

“In the area where I live and practice, it feels like guns and the people who use them have more legal rights than people with uteruses in desperate or life-threatening situations. I’m afraid for my personal safety as a women’s health practitioner in this political climate. I feel helpless, but I’m supposed to be able to help my patients.”

Missouri family planning specialist

“Abortion is an essential part of healthcare, and the only people that should get a say in it are the patient and their doctor. Period. The fact that some far-off court without any medical expertise can insert itself into individual medical decisions is oppressive and unethical.”

Georgia ob.gyn.

“I can’t even think straight right now. I feel sick. Honestly, I’ve been thinking about moving for a long time now. Somewhere where I would actually be able to offer good, comprehensive care.”

New York ob.gyn.

“I graduated from my ob.gyn. residency hours after the Roe v. Wade news broke. It was so emotional for me. I’ve dedicated my life to caring for people with uteruses and I will not let this heartbreaking news change that. I feel more committed than ever to women’s health. I fully plan to continue delivering babies, providing contraception, and performing abortions. I will be there to help women with desired pregnancies who received unspeakably bad news about fetal anomalies. I will be there to help women with life-threatening pregnancy complications before fetal viability. I will be there to help women with ectopic pregnancies. I will be there to help women who were raped or otherwise forced into pregnancy. I will always be there to help women.”

Dr. Croll is a neurovascular fellow at New York University Langone Health. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“I’m happy to contribute, but can you keep it anonymous? It’s a safety concern for me.”

On the day that the Supreme Court of the United States voted to strike down Roe v. Wade, I reached out to ob.gyn.s across the country, wanting to hear their reactions. My own response, like that of many doctors and women, was a visceral mix of anger, fear, and grief. I could only begin to imagine what the real experts on reproductive health care were going through.

When the first ob.gyn. responded to my request by expressing concerns around anonymity and personal safety, I was shocked – but I shouldn’t have been. For starters, there is already a storied history in this country of deadly attacks on abortion providers. David Gunn, MD; Barnett Slepian, MD; and George Tiller, MD, were all tragically murdered by antiabortion extremists. Then, there’s the existence of websites that keep logs of abortion providers and sometimes include photos, office contact information, or even home addresses.

The idea that any reproductive health care provider should have to think twice before offering their uniquely qualified opinion is profoundly disturbing, nearly as disturbing as the Supreme Court’s decision itself. But it’s more critical than ever for ob.gyn. voices to be amplified. This is the time for the healthcare community to rally around women’s health providers, to learn from them, to support them.

I asked ob.gyns. around the country to tell me what they were thinking and feeling on the day that Roe v. Wade was overturned. We agreed to keep the responses anonymous, given that several people expressed very understandable safety concerns.

Here’s what they had to say.

Tennessee ob.gyn.

“Today is an emotionally charged day for many people in this country, yet as I type this, with my ob.gyn. practice continuing around me, with my own almost 10-week pregnancy growing inside me, I feel quite blunted. I feel powerless to answer questions that are variations on ‘what next?’ or ‘how do we fight back?’ All I can think of is, I am so glad I do not have anyone on my schedule right now who does not want to be pregnant. But what will happen when that eventually changes? What about my colleagues who do have these patients on their schedules today? On a personal level, what if my prenatal genetic testing comes back abnormal? How can we so blatantly disregard a separation of church and state in this country? What ways will our government interfere with my practice next? My head is spinning, but I have to go see my next patient. She is a 25-year-old who is here to have an IUD placed, and that seems like the most important thing I can do today.”

South Carolina ob.gyn.

“I’m really scared. For my patients and for myself. I don’t know how to be a good ob.gyn. if my ability to offer safe and accessible abortion care is being threatened.”

Massachusetts ob.gyn.

“Livid and devastated and sad and terrified.”

California family planning specialist

“The fact is that about one in four people with uteruses have had an abortion. I can’t tell you how many abortions I’ve provided for people who say that they don’t ‘believe’ in them or that they thought they’d never be in this situation. ... The fact is that pregnancy is a life-threatening condition in and of itself. I am an ob.gyn., a medical doctor, and an abortion provider. I will not stop providing abortions or helping people access them. I will dedicate my life to ensuring this right to bodily autonomy. Today I am devastated by the Supreme Court’s decision to force parenthood that will result in increased maternal mortality. I am broken, but I have never been more proud to be an abortion provider.”

New York ob.gyn.

“Grateful to live in a state and work for a hospital where I can provide abortions but feel terrible for so many people less fortunate and underserved.”

Illinois maternal-fetal medicine specialist

“As a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, I fear for my patients who are at the highest risk of pregnancy complications having their freedom taken away. For the tragic ultrasound findings that make a pregnant person carry a baby who will never live. For the patients who cannot use most forms of contraception because of their medical comorbidities. For the patients who are victims of intimate partner violence or under the influence of their culture, to continue having children regardless of their desires or their health. ... The freedom to prevent or end a pregnancy has enabled women to become independent and productive members of society on their own terms, with or without children. My heart breaks for the children and adolescents and adults who are being told they are second-class citizens, not worthy of making their own decisions. Politicians and Supreme Court justices are not in the clinic room, ultrasound suite, operating room, or delivery room when we have these intense conversations and pregnancy outcomes. They have no idea that of which they speak, and it’s unconscionable that they can determine what healthcare decisions my patients can make for their own lives. Nobody knows a body better than the patient themselves.”

Texas ob.gyn.

“In the area where I live and practice, it feels like guns and the people who use them have more legal rights than people with uteruses in desperate or life-threatening situations. I’m afraid for my personal safety as a women’s health practitioner in this political climate. I feel helpless, but I’m supposed to be able to help my patients.”

Missouri family planning specialist

“Abortion is an essential part of healthcare, and the only people that should get a say in it are the patient and their doctor. Period. The fact that some far-off court without any medical expertise can insert itself into individual medical decisions is oppressive and unethical.”

Georgia ob.gyn.

“I can’t even think straight right now. I feel sick. Honestly, I’ve been thinking about moving for a long time now. Somewhere where I would actually be able to offer good, comprehensive care.”

New York ob.gyn.

“I graduated from my ob.gyn. residency hours after the Roe v. Wade news broke. It was so emotional for me. I’ve dedicated my life to caring for people with uteruses and I will not let this heartbreaking news change that. I feel more committed than ever to women’s health. I fully plan to continue delivering babies, providing contraception, and performing abortions. I will be there to help women with desired pregnancies who received unspeakably bad news about fetal anomalies. I will be there to help women with life-threatening pregnancy complications before fetal viability. I will be there to help women with ectopic pregnancies. I will be there to help women who were raped or otherwise forced into pregnancy. I will always be there to help women.”

Dr. Croll is a neurovascular fellow at New York University Langone Health. She disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

My picks for best of ASCO 2022

CHICAGO – The American Society of Clinical Oncology recently wrapped its annual meeting in Chicago. Here, I highlight some presentations that stood out to me.

A first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer

The plenary session did not disappoint. In abstract LBA1, investigators presented first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 with either bevacizumab or panitumumab in RAS wild-type positive patients. This was the phase 3 PARADIGM trial.

The primary outcome for this study was overall survival. It included 823 patients who were randomized 1:1 with a subset analysis of whether the primary tumor was on the left or right side of the colon. At 61 months follow-up, the median overall survival results for left-sided colon cancer was 38 months versus 34 months. It was statistically significant favoring the panitumumab arm. It improved the curable resection rate for patients with left-sided tumors from 11% in the bevacizumab arm to 18% in the panitumumab arm. Interestingly, patients randomized with right-sided tumors showed no difference in overall survival. The investigator, Takayuki Yoshino, MD, PhD, National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa, Japan, said the study findings support the use of mFOLFOX6 with panitumumab in left-sided RAS wild type as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal patients.

A possible new standard of care in breast cancer

Shanu Modi, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, received a standing ovation and deserved it. In the phase 3 clinical trial DESTINY-Breast04 (abstract LBA3), she demonstrated that trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for patients with metastatic breast cancer who were HER2 low (IHC 1+ or 2+ ISH-), led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful benefit in both progression free survival and overall survival. In this trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. All patients had at least one to two lines of chemotherapy before entering the trial. Hormone-positive patients were allowed if they had already received and failed, or progressed on hormone therapy.

Previously, most patients were treated either with eribulin with some receiving capecitabine, gemcitabine or taxane, or hormone therapy if hormone positive.

The progression-free survival was 10.1 versus 5.4 months in hormone-positive patients, and in all patients (hormone receptor positive or negative), there was a likewise improvement of 9.9 versus 5.1 months progression free survival.

Overall survival was equally impressive. In the hormone receptor–positive patients, the hazard ratio was 0.64 with a 23.9 versus 17.5 month survival. If all patients were included, the HR was again 0.64 with 23.4 versus 16.8 month survival. Even the triple-negative breast cancer patients had a HR of 0.48 with 18.2 versus 8.3 months survival. Adverse events were quite tolerable with some nausea, some decreased white count, and only an interstitial lung disease of grade 2 or less in 12%.

Trastuzumab deruxtecan is a targeted treatment which, in addition to striking its target, also targets other tumor cells that are part of the cancer. The results of this study may lead to a new standard of care of this patient population.

The study by Dr. Modi and colleagues was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Improving outcomes in multiple myeloma

In abstract LBA4, Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, asks if autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) can improve outcomes after induction with an RVD regimen (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone) and lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance for newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma in the DETERMINATION study.

The take home here was quite interesting. In fact, there is no difference in overall survival if patients get this standard RVD/lenalidomide maintenance induction with or without ASCT. However, the progression free survival was better with ASCT: 46 versus 67 months (improvement of 21 months). However, there were some caveats. There was toxicity and change in quality of life for a while in those patients receiving ASCT as would be expected. Furthermore, the study only allowed 65 years old or younger and ASCT may not be wise for older patients. The discussant made a strong point that African Americans tend to have higher risk disease with different mutations and might also be better served by have ASCT later.

The conclusion was that, given all the new therapies in myeloma for second line and beyond, ASCT should be a discussion with each new patient and not an automatic decision.

This study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Adagrasib promising for pretreated patients with NSCLC with KRAS mutation

In patients with advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), adagrasib was found to be well tolerated and “demonstrates promising efficacy” for patients with the KRAS G12C mutation (KRYSTAL-1, abstract 9002). This was a phase 2 registration trial of 116 patients who were treated with 600 mg of adagrasib twice orally. Patients all had previous chemotherapy or immunotherapy or both. The overall response rate was a surprisingly good 43% (complete response and partial response). Disease control was an incredible 80% if stable disease was included. The duration of response was 8.5 months, progression-free survival was 6.5 months, and overall survival was 12.6 months. Furthermore, 33% of those with brain metastases had a complete response or partial response.

The take-home message is that, since 15% of NSCLC metastatic patients are KRAS mutant G12C, we should be watching for such patients in our biomarker analysis. While we have sotorasib – approved by the Food and Drug Administration for NSCLC – the results of this study suggests we may have another new molecule in the same class.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with immunotherapy for NSCLC

It may be time to consider neoadjuvant chemotherapy with immunotherapy, such as nivolumab, for patients with NSCLC in order to achieve the best response possible.

In NADIM II, investigators led by Mariano Provencio-Pulla, MD, of the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, confirmed the superiority of chemotherapy with immunotherapy for patients with resectable stage IIIA NSCLC. NADIM included patients with resectable stage IIIA/B NSCLC who were randomized 2:1 to receive carboplatin taxol neoadjuvant therapy with or without nivolumab before and after surgery. The pathological complete response rates overall were 36% versus 7%, favoring the nivolumab arm, but even higher pCR rates occurred in patients with PD-L1 over 50%.

In closing, always check MMR, KRAS, BRAF, and HER2. For wild-type left-sided mCRC, consider FOLFOX or FOLFIRI with an anti-EGFR. For KRAS mutant or right-sided colon tumor, consider FOLFOX or FOLFIRI with bevacizumab, followed by maintenance 5FU or capecitabine, with or without bevacizumab.

CHICAGO – The American Society of Clinical Oncology recently wrapped its annual meeting in Chicago. Here, I highlight some presentations that stood out to me.

A first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer

The plenary session did not disappoint. In abstract LBA1, investigators presented first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 with either bevacizumab or panitumumab in RAS wild-type positive patients. This was the phase 3 PARADIGM trial.

The primary outcome for this study was overall survival. It included 823 patients who were randomized 1:1 with a subset analysis of whether the primary tumor was on the left or right side of the colon. At 61 months follow-up, the median overall survival results for left-sided colon cancer was 38 months versus 34 months. It was statistically significant favoring the panitumumab arm. It improved the curable resection rate for patients with left-sided tumors from 11% in the bevacizumab arm to 18% in the panitumumab arm. Interestingly, patients randomized with right-sided tumors showed no difference in overall survival. The investigator, Takayuki Yoshino, MD, PhD, National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa, Japan, said the study findings support the use of mFOLFOX6 with panitumumab in left-sided RAS wild type as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal patients.

A possible new standard of care in breast cancer

Shanu Modi, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, received a standing ovation and deserved it. In the phase 3 clinical trial DESTINY-Breast04 (abstract LBA3), she demonstrated that trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for patients with metastatic breast cancer who were HER2 low (IHC 1+ or 2+ ISH-), led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful benefit in both progression free survival and overall survival. In this trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. All patients had at least one to two lines of chemotherapy before entering the trial. Hormone-positive patients were allowed if they had already received and failed, or progressed on hormone therapy.

Previously, most patients were treated either with eribulin with some receiving capecitabine, gemcitabine or taxane, or hormone therapy if hormone positive.

The progression-free survival was 10.1 versus 5.4 months in hormone-positive patients, and in all patients (hormone receptor positive or negative), there was a likewise improvement of 9.9 versus 5.1 months progression free survival.

Overall survival was equally impressive. In the hormone receptor–positive patients, the hazard ratio was 0.64 with a 23.9 versus 17.5 month survival. If all patients were included, the HR was again 0.64 with 23.4 versus 16.8 month survival. Even the triple-negative breast cancer patients had a HR of 0.48 with 18.2 versus 8.3 months survival. Adverse events were quite tolerable with some nausea, some decreased white count, and only an interstitial lung disease of grade 2 or less in 12%.

Trastuzumab deruxtecan is a targeted treatment which, in addition to striking its target, also targets other tumor cells that are part of the cancer. The results of this study may lead to a new standard of care of this patient population.

The study by Dr. Modi and colleagues was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Improving outcomes in multiple myeloma

In abstract LBA4, Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, asks if autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) can improve outcomes after induction with an RVD regimen (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone) and lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance for newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma in the DETERMINATION study.

The take home here was quite interesting. In fact, there is no difference in overall survival if patients get this standard RVD/lenalidomide maintenance induction with or without ASCT. However, the progression free survival was better with ASCT: 46 versus 67 months (improvement of 21 months). However, there were some caveats. There was toxicity and change in quality of life for a while in those patients receiving ASCT as would be expected. Furthermore, the study only allowed 65 years old or younger and ASCT may not be wise for older patients. The discussant made a strong point that African Americans tend to have higher risk disease with different mutations and might also be better served by have ASCT later.

The conclusion was that, given all the new therapies in myeloma for second line and beyond, ASCT should be a discussion with each new patient and not an automatic decision.

This study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Adagrasib promising for pretreated patients with NSCLC with KRAS mutation

In patients with advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), adagrasib was found to be well tolerated and “demonstrates promising efficacy” for patients with the KRAS G12C mutation (KRYSTAL-1, abstract 9002). This was a phase 2 registration trial of 116 patients who were treated with 600 mg of adagrasib twice orally. Patients all had previous chemotherapy or immunotherapy or both. The overall response rate was a surprisingly good 43% (complete response and partial response). Disease control was an incredible 80% if stable disease was included. The duration of response was 8.5 months, progression-free survival was 6.5 months, and overall survival was 12.6 months. Furthermore, 33% of those with brain metastases had a complete response or partial response.

The take-home message is that, since 15% of NSCLC metastatic patients are KRAS mutant G12C, we should be watching for such patients in our biomarker analysis. While we have sotorasib – approved by the Food and Drug Administration for NSCLC – the results of this study suggests we may have another new molecule in the same class.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with immunotherapy for NSCLC

It may be time to consider neoadjuvant chemotherapy with immunotherapy, such as nivolumab, for patients with NSCLC in order to achieve the best response possible.

In NADIM II, investigators led by Mariano Provencio-Pulla, MD, of the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, confirmed the superiority of chemotherapy with immunotherapy for patients with resectable stage IIIA NSCLC. NADIM included patients with resectable stage IIIA/B NSCLC who were randomized 2:1 to receive carboplatin taxol neoadjuvant therapy with or without nivolumab before and after surgery. The pathological complete response rates overall were 36% versus 7%, favoring the nivolumab arm, but even higher pCR rates occurred in patients with PD-L1 over 50%.

In closing, always check MMR, KRAS, BRAF, and HER2. For wild-type left-sided mCRC, consider FOLFOX or FOLFIRI with an anti-EGFR. For KRAS mutant or right-sided colon tumor, consider FOLFOX or FOLFIRI with bevacizumab, followed by maintenance 5FU or capecitabine, with or without bevacizumab.

CHICAGO – The American Society of Clinical Oncology recently wrapped its annual meeting in Chicago. Here, I highlight some presentations that stood out to me.

A first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer

The plenary session did not disappoint. In abstract LBA1, investigators presented first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who were randomized to receive mFOLFOX6 with either bevacizumab or panitumumab in RAS wild-type positive patients. This was the phase 3 PARADIGM trial.

The primary outcome for this study was overall survival. It included 823 patients who were randomized 1:1 with a subset analysis of whether the primary tumor was on the left or right side of the colon. At 61 months follow-up, the median overall survival results for left-sided colon cancer was 38 months versus 34 months. It was statistically significant favoring the panitumumab arm. It improved the curable resection rate for patients with left-sided tumors from 11% in the bevacizumab arm to 18% in the panitumumab arm. Interestingly, patients randomized with right-sided tumors showed no difference in overall survival. The investigator, Takayuki Yoshino, MD, PhD, National Cancer Center Hospital East, Kashiwa, Japan, said the study findings support the use of mFOLFOX6 with panitumumab in left-sided RAS wild type as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal patients.

A possible new standard of care in breast cancer

Shanu Modi, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, received a standing ovation and deserved it. In the phase 3 clinical trial DESTINY-Breast04 (abstract LBA3), she demonstrated that trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) for patients with metastatic breast cancer who were HER2 low (IHC 1+ or 2+ ISH-), led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful benefit in both progression free survival and overall survival. In this trial, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive trastuzumab deruxtecan or physician’s choice of chemotherapy. All patients had at least one to two lines of chemotherapy before entering the trial. Hormone-positive patients were allowed if they had already received and failed, or progressed on hormone therapy.

Previously, most patients were treated either with eribulin with some receiving capecitabine, gemcitabine or taxane, or hormone therapy if hormone positive.

The progression-free survival was 10.1 versus 5.4 months in hormone-positive patients, and in all patients (hormone receptor positive or negative), there was a likewise improvement of 9.9 versus 5.1 months progression free survival.

Overall survival was equally impressive. In the hormone receptor–positive patients, the hazard ratio was 0.64 with a 23.9 versus 17.5 month survival. If all patients were included, the HR was again 0.64 with 23.4 versus 16.8 month survival. Even the triple-negative breast cancer patients had a HR of 0.48 with 18.2 versus 8.3 months survival. Adverse events were quite tolerable with some nausea, some decreased white count, and only an interstitial lung disease of grade 2 or less in 12%.

Trastuzumab deruxtecan is a targeted treatment which, in addition to striking its target, also targets other tumor cells that are part of the cancer. The results of this study may lead to a new standard of care of this patient population.

The study by Dr. Modi and colleagues was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Improving outcomes in multiple myeloma

In abstract LBA4, Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, asks if autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) can improve outcomes after induction with an RVD regimen (lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone) and lenalidomide (Revlimid) maintenance for newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma in the DETERMINATION study.

The take home here was quite interesting. In fact, there is no difference in overall survival if patients get this standard RVD/lenalidomide maintenance induction with or without ASCT. However, the progression free survival was better with ASCT: 46 versus 67 months (improvement of 21 months). However, there were some caveats. There was toxicity and change in quality of life for a while in those patients receiving ASCT as would be expected. Furthermore, the study only allowed 65 years old or younger and ASCT may not be wise for older patients. The discussant made a strong point that African Americans tend to have higher risk disease with different mutations and might also be better served by have ASCT later.

The conclusion was that, given all the new therapies in myeloma for second line and beyond, ASCT should be a discussion with each new patient and not an automatic decision.

This study was simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Adagrasib promising for pretreated patients with NSCLC with KRAS mutation

In patients with advanced or metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), adagrasib was found to be well tolerated and “demonstrates promising efficacy” for patients with the KRAS G12C mutation (KRYSTAL-1, abstract 9002). This was a phase 2 registration trial of 116 patients who were treated with 600 mg of adagrasib twice orally. Patients all had previous chemotherapy or immunotherapy or both. The overall response rate was a surprisingly good 43% (complete response and partial response). Disease control was an incredible 80% if stable disease was included. The duration of response was 8.5 months, progression-free survival was 6.5 months, and overall survival was 12.6 months. Furthermore, 33% of those with brain metastases had a complete response or partial response.

The take-home message is that, since 15% of NSCLC metastatic patients are KRAS mutant G12C, we should be watching for such patients in our biomarker analysis. While we have sotorasib – approved by the Food and Drug Administration for NSCLC – the results of this study suggests we may have another new molecule in the same class.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with immunotherapy for NSCLC

It may be time to consider neoadjuvant chemotherapy with immunotherapy, such as nivolumab, for patients with NSCLC in order to achieve the best response possible.

In NADIM II, investigators led by Mariano Provencio-Pulla, MD, of the Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, confirmed the superiority of chemotherapy with immunotherapy for patients with resectable stage IIIA NSCLC. NADIM included patients with resectable stage IIIA/B NSCLC who were randomized 2:1 to receive carboplatin taxol neoadjuvant therapy with or without nivolumab before and after surgery. The pathological complete response rates overall were 36% versus 7%, favoring the nivolumab arm, but even higher pCR rates occurred in patients with PD-L1 over 50%.

In closing, always check MMR, KRAS, BRAF, and HER2. For wild-type left-sided mCRC, consider FOLFOX or FOLFIRI with an anti-EGFR. For KRAS mutant or right-sided colon tumor, consider FOLFOX or FOLFIRI with bevacizumab, followed by maintenance 5FU or capecitabine, with or without bevacizumab.

AT ASCO 2022

Adjuvant vs. neoadjuvant? What has ASCO 2022 taught us regarding resectable NSCLC?

for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). While there has been some notable progress in this area, we need phase 3 trials that compare the two therapeutic approaches.

Investigators reporting at the 2022 annual meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology focused primarily on neoadjuvant treatment, which I’ll address here.

In the randomized, phase 2 NADIM II clinical trial reported at the meeting, researchers expanded on the results of NADIM published in 2020 in the Lancet Oncology and in May 2022 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology along with CheckMate 816 results published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In each of these three studies, researchers compared nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone (abstract 8501) as a neoadjuvant treatment for resectable stage IIIA NSCLC. In the study reported at ASCO 2022, patients with resectable clinical stage IIIA-B (per American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition) NSCLC and no known EGFR/ALK alterations, were randomized to receive preoperative nivolumab plus chemotherapy (paclitaxel and carboplatin; n = 57) or chemotherapy (n = 29) alone followed by surgery.

The primary endpoint was pathological complete response (pCR); secondary endpoints included major pathological response, safety and tolerability, impact on surgical issues such as delayed or canceled surgeries or length of hospital stay, overall survival and progression free survival. The pCR rate was 36.8% in the neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm and 6.9% in the chemotherapy alone arm. (P = .0068). 25% of patients on the nivolumab plus chemo arm had grade 3-4 adverse events, compared with 10.3% in the control arm. 93% of patients on the nivolumab plus chemo arm underwent definitive surgery whereas 69.0% of the patients on the chemo alone arm had definitive surgery. (P = .008)

What else did we learn about neoadjuvant treatment at the meeting?

Investigators looking at the optimal number of neoadjuvant cycles (abstract 8500) found that three cycles of sintilimab (an investigational PD-1 inhibitor) produced a numerically higher major pathological response rate, compared with two cycles (when given in concert with platinum-doublet chemotherapy). And, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy does not result in significant survival benefits when compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (abstract 8503).

Of course, when it comes to resectable NSCLC, the goal of treatment is to increase the cure rate and improve survival. No randomized studies have reported yet on overall survival, probably because they are too immature. Instead, disease-free survival (DFS) or event-free survival (EFS) are often used as surrogate endpoints. Since none of the studies reported at ASCO reported on DFS or EFS, we need to look elsewhere. CheckMate 816 was a phase 3 study which randomized patients with stages IB-IIIA NSCLC to receive neoadjuvant nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy or neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy alone, followed by resection. The median EFS was 31.6 months with nivolumab plus chemotherapy and 20.8 months with chemotherapy alone (P = .005). The percentage of patients with a pCR was 24.0% and 2.2%, respectively (P < .001).

We all know one has to be careful when doing cross-trial comparisons as these studies differ by the percentage of patients with various stages of disease, the type of immunotherapy and chemotherapy used, etc. However, I think we can agree that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy results in better outcomes than chemotherapy alone.

Of course, resectable NSCLC is, by definition, resectable. And traditionally, resection is followed by adjuvant chemotherapy to eradicate micrometastases. Unfortunately, the current standard of care for completely resected early-stage NSCLC (stage I [tumor ≥ 4 cm] to IIIA) involves adjuvant platinum-based combination chemotherapy which results in only a modest 4%-5% improvement in survival versus observation.

Given these modest results, as in the neoadjuvant space, investigators have looked at the benefit of adding immunotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy. One such study has been reported. IMpower 010 randomly assigned patients with completely resected stage IB (tumors ≥ 4 cm) to IIIA NSCLC, whose tumor cells expressed at least 1% PD-L1, to receive adjuvant atezolizumab or best supportive care after adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. In the stage II-IIIA population whose tumors expressed PD-L1 on 1% or more of tumor cells, 3-year DFS rates were 60% and 48% in the atezolizumab and best supportive care arms, respectively (hazard ratio, 0·66 P =·.0039). In all patients in the stage II-IIIA population, the 3-year DFS rates were 56% in the atezolizumab group and 49% in the best supportive care group, (HR, 0.79; P = .020).

KEYNOTE-091, reported at the 2021 annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology, randomized early-stage NSCLC patients following complete resection and adjuvant chemotherapy to pembrolizumab or placebo. Median DFS for the overall population was 53.6 months for patients in the pembro arm versus 42 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.76; P = .0014). Interestingly, the benefit was not seen in patients with PD-L1 with at least 50%, where the 18-month DFS rate was 71.7% in the pembro arm and 70.2% in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .14). Although the contradictory results of PD-L1 as a biomarker is puzzling, I think we can agree that the addition of immunotherapy following adjuvant chemotherapy improves outcomes compared to adjuvant chemotherapy alone.

What to do when a patient presents with resectable disease?

Cross-trial comparisons are fraught with danger. Until we have a phase 3 study comparing concurrent neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy with concurrent adjuvant chemo/immunotherapy, I do not think we can answer the question “which is better?” However, there are some caveats to keep in mind when deciding on which approach to recommend to our patients: First, neoadjuvant treatment requires biomarker testing to ensure the patient does not have EGFR or ALK mutations. This will necessitate a delay in the operation. Will patients be willing to wait? Will the surgeon? Or, would patients prefer to proceed with surgery while the results are pending? Yes, neoadjuvant therapy gives you information regarding the pCR rate, but does that help you in subsequent management of the patient? We do not know.

Secondly, the two adjuvant studies used adjuvant chemotherapy followed by adjuvant immunotherapy, as contrasted to the neoadjuvant study which used concurrent chemo/immunotherapy. Given the longer duration of treatment in postoperative sequential adjuvant studies, there tends to be more drop off because of patients being unwilling or unfit postoperatively to receive long courses of therapy. In IMpower 010, 1,269 patients completed adjuvant chemotherapy; 1,005 were randomized, and of the 507 assigned to the atezolizumab/chemo group, only 323 completed treatment.

Finally, we must beware of using neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy to “down-stage” a patient. KEYNOTE-091 included patients with IIIA disease and no benefit to adjuvant chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy was found in this subgroup of patients, which leads me to wonder if these patients were appropriately selected as surgical candidates. In the NADIM II trials, 9 of 29 patients on the neoadjuvant chemotherapy were not resected.

So, many questions remain. In addition to the ones we’ve raised, there is a clear and immediate need for predictive and prognostic biomarkers. In the NADIM II trial, PD-L1 expression was a predictive biomarker of response. The pCR rate for patients with a PD-L1 tumor expression of less than 1%, 1%-49%, and 50% or higher was 15%, 41.7%, and 61.1%, respectively. However, in KEYNOTE-091, the benefit was not seen in patients with PD-L1 of at least than 50%, where the 18-month DFS rate was 71.7% in the pembro arm and 70.2% in the placebo arm.

Another possible biomarker: circulating tumor DNA. In the first NADIM study, three low pretreatment levels of ctDNA were significantly associated with improved progression-free survival and overall survival (HR, 0.20 and HR, 0.07, respectively). Although clinical response did not predict survival outcomes, undetectable ctDNA levels after neoadjuvant treatment were significantly associated with progression-free survival and overall survival (HR, 0.26 and HR0.04, respectively). Similarly, in CheckMate 816, clearance of ctDNA was associated with longer EFS in patients with ctDNA clearance than in those without ctDNA clearance in both the nivolumab/chemotherapy group (HR, 0.60) and the chemotherapy-alone group (HR, 0.63).

Hopefully, ASCO 2023 will provide more answers.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). While there has been some notable progress in this area, we need phase 3 trials that compare the two therapeutic approaches.

Investigators reporting at the 2022 annual meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology focused primarily on neoadjuvant treatment, which I’ll address here.

In the randomized, phase 2 NADIM II clinical trial reported at the meeting, researchers expanded on the results of NADIM published in 2020 in the Lancet Oncology and in May 2022 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology along with CheckMate 816 results published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In each of these three studies, researchers compared nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone (abstract 8501) as a neoadjuvant treatment for resectable stage IIIA NSCLC. In the study reported at ASCO 2022, patients with resectable clinical stage IIIA-B (per American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition) NSCLC and no known EGFR/ALK alterations, were randomized to receive preoperative nivolumab plus chemotherapy (paclitaxel and carboplatin; n = 57) or chemotherapy (n = 29) alone followed by surgery.

The primary endpoint was pathological complete response (pCR); secondary endpoints included major pathological response, safety and tolerability, impact on surgical issues such as delayed or canceled surgeries or length of hospital stay, overall survival and progression free survival. The pCR rate was 36.8% in the neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm and 6.9% in the chemotherapy alone arm. (P = .0068). 25% of patients on the nivolumab plus chemo arm had grade 3-4 adverse events, compared with 10.3% in the control arm. 93% of patients on the nivolumab plus chemo arm underwent definitive surgery whereas 69.0% of the patients on the chemo alone arm had definitive surgery. (P = .008)

What else did we learn about neoadjuvant treatment at the meeting?

Investigators looking at the optimal number of neoadjuvant cycles (abstract 8500) found that three cycles of sintilimab (an investigational PD-1 inhibitor) produced a numerically higher major pathological response rate, compared with two cycles (when given in concert with platinum-doublet chemotherapy). And, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy does not result in significant survival benefits when compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (abstract 8503).

Of course, when it comes to resectable NSCLC, the goal of treatment is to increase the cure rate and improve survival. No randomized studies have reported yet on overall survival, probably because they are too immature. Instead, disease-free survival (DFS) or event-free survival (EFS) are often used as surrogate endpoints. Since none of the studies reported at ASCO reported on DFS or EFS, we need to look elsewhere. CheckMate 816 was a phase 3 study which randomized patients with stages IB-IIIA NSCLC to receive neoadjuvant nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy or neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy alone, followed by resection. The median EFS was 31.6 months with nivolumab plus chemotherapy and 20.8 months with chemotherapy alone (P = .005). The percentage of patients with a pCR was 24.0% and 2.2%, respectively (P < .001).

We all know one has to be careful when doing cross-trial comparisons as these studies differ by the percentage of patients with various stages of disease, the type of immunotherapy and chemotherapy used, etc. However, I think we can agree that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy results in better outcomes than chemotherapy alone.

Of course, resectable NSCLC is, by definition, resectable. And traditionally, resection is followed by adjuvant chemotherapy to eradicate micrometastases. Unfortunately, the current standard of care for completely resected early-stage NSCLC (stage I [tumor ≥ 4 cm] to IIIA) involves adjuvant platinum-based combination chemotherapy which results in only a modest 4%-5% improvement in survival versus observation.

Given these modest results, as in the neoadjuvant space, investigators have looked at the benefit of adding immunotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy. One such study has been reported. IMpower 010 randomly assigned patients with completely resected stage IB (tumors ≥ 4 cm) to IIIA NSCLC, whose tumor cells expressed at least 1% PD-L1, to receive adjuvant atezolizumab or best supportive care after adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. In the stage II-IIIA population whose tumors expressed PD-L1 on 1% or more of tumor cells, 3-year DFS rates were 60% and 48% in the atezolizumab and best supportive care arms, respectively (hazard ratio, 0·66 P =·.0039). In all patients in the stage II-IIIA population, the 3-year DFS rates were 56% in the atezolizumab group and 49% in the best supportive care group, (HR, 0.79; P = .020).

KEYNOTE-091, reported at the 2021 annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology, randomized early-stage NSCLC patients following complete resection and adjuvant chemotherapy to pembrolizumab or placebo. Median DFS for the overall population was 53.6 months for patients in the pembro arm versus 42 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.76; P = .0014). Interestingly, the benefit was not seen in patients with PD-L1 with at least 50%, where the 18-month DFS rate was 71.7% in the pembro arm and 70.2% in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .14). Although the contradictory results of PD-L1 as a biomarker is puzzling, I think we can agree that the addition of immunotherapy following adjuvant chemotherapy improves outcomes compared to adjuvant chemotherapy alone.

What to do when a patient presents with resectable disease?

Cross-trial comparisons are fraught with danger. Until we have a phase 3 study comparing concurrent neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy with concurrent adjuvant chemo/immunotherapy, I do not think we can answer the question “which is better?” However, there are some caveats to keep in mind when deciding on which approach to recommend to our patients: First, neoadjuvant treatment requires biomarker testing to ensure the patient does not have EGFR or ALK mutations. This will necessitate a delay in the operation. Will patients be willing to wait? Will the surgeon? Or, would patients prefer to proceed with surgery while the results are pending? Yes, neoadjuvant therapy gives you information regarding the pCR rate, but does that help you in subsequent management of the patient? We do not know.

Secondly, the two adjuvant studies used adjuvant chemotherapy followed by adjuvant immunotherapy, as contrasted to the neoadjuvant study which used concurrent chemo/immunotherapy. Given the longer duration of treatment in postoperative sequential adjuvant studies, there tends to be more drop off because of patients being unwilling or unfit postoperatively to receive long courses of therapy. In IMpower 010, 1,269 patients completed adjuvant chemotherapy; 1,005 were randomized, and of the 507 assigned to the atezolizumab/chemo group, only 323 completed treatment.

Finally, we must beware of using neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy to “down-stage” a patient. KEYNOTE-091 included patients with IIIA disease and no benefit to adjuvant chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy was found in this subgroup of patients, which leads me to wonder if these patients were appropriately selected as surgical candidates. In the NADIM II trials, 9 of 29 patients on the neoadjuvant chemotherapy were not resected.

So, many questions remain. In addition to the ones we’ve raised, there is a clear and immediate need for predictive and prognostic biomarkers. In the NADIM II trial, PD-L1 expression was a predictive biomarker of response. The pCR rate for patients with a PD-L1 tumor expression of less than 1%, 1%-49%, and 50% or higher was 15%, 41.7%, and 61.1%, respectively. However, in KEYNOTE-091, the benefit was not seen in patients with PD-L1 of at least than 50%, where the 18-month DFS rate was 71.7% in the pembro arm and 70.2% in the placebo arm.

Another possible biomarker: circulating tumor DNA. In the first NADIM study, three low pretreatment levels of ctDNA were significantly associated with improved progression-free survival and overall survival (HR, 0.20 and HR, 0.07, respectively). Although clinical response did not predict survival outcomes, undetectable ctDNA levels after neoadjuvant treatment were significantly associated with progression-free survival and overall survival (HR, 0.26 and HR0.04, respectively). Similarly, in CheckMate 816, clearance of ctDNA was associated with longer EFS in patients with ctDNA clearance than in those without ctDNA clearance in both the nivolumab/chemotherapy group (HR, 0.60) and the chemotherapy-alone group (HR, 0.63).

Hopefully, ASCO 2023 will provide more answers.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). While there has been some notable progress in this area, we need phase 3 trials that compare the two therapeutic approaches.

Investigators reporting at the 2022 annual meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology focused primarily on neoadjuvant treatment, which I’ll address here.

In the randomized, phase 2 NADIM II clinical trial reported at the meeting, researchers expanded on the results of NADIM published in 2020 in the Lancet Oncology and in May 2022 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology along with CheckMate 816 results published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

In each of these three studies, researchers compared nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone (abstract 8501) as a neoadjuvant treatment for resectable stage IIIA NSCLC. In the study reported at ASCO 2022, patients with resectable clinical stage IIIA-B (per American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition) NSCLC and no known EGFR/ALK alterations, were randomized to receive preoperative nivolumab plus chemotherapy (paclitaxel and carboplatin; n = 57) or chemotherapy (n = 29) alone followed by surgery.

The primary endpoint was pathological complete response (pCR); secondary endpoints included major pathological response, safety and tolerability, impact on surgical issues such as delayed or canceled surgeries or length of hospital stay, overall survival and progression free survival. The pCR rate was 36.8% in the neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy arm and 6.9% in the chemotherapy alone arm. (P = .0068). 25% of patients on the nivolumab plus chemo arm had grade 3-4 adverse events, compared with 10.3% in the control arm. 93% of patients on the nivolumab plus chemo arm underwent definitive surgery whereas 69.0% of the patients on the chemo alone arm had definitive surgery. (P = .008)

What else did we learn about neoadjuvant treatment at the meeting?

Investigators looking at the optimal number of neoadjuvant cycles (abstract 8500) found that three cycles of sintilimab (an investigational PD-1 inhibitor) produced a numerically higher major pathological response rate, compared with two cycles (when given in concert with platinum-doublet chemotherapy). And, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy does not result in significant survival benefits when compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone (abstract 8503).

Of course, when it comes to resectable NSCLC, the goal of treatment is to increase the cure rate and improve survival. No randomized studies have reported yet on overall survival, probably because they are too immature. Instead, disease-free survival (DFS) or event-free survival (EFS) are often used as surrogate endpoints. Since none of the studies reported at ASCO reported on DFS or EFS, we need to look elsewhere. CheckMate 816 was a phase 3 study which randomized patients with stages IB-IIIA NSCLC to receive neoadjuvant nivolumab plus platinum-based chemotherapy or neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy alone, followed by resection. The median EFS was 31.6 months with nivolumab plus chemotherapy and 20.8 months with chemotherapy alone (P = .005). The percentage of patients with a pCR was 24.0% and 2.2%, respectively (P < .001).

We all know one has to be careful when doing cross-trial comparisons as these studies differ by the percentage of patients with various stages of disease, the type of immunotherapy and chemotherapy used, etc. However, I think we can agree that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy results in better outcomes than chemotherapy alone.

Of course, resectable NSCLC is, by definition, resectable. And traditionally, resection is followed by adjuvant chemotherapy to eradicate micrometastases. Unfortunately, the current standard of care for completely resected early-stage NSCLC (stage I [tumor ≥ 4 cm] to IIIA) involves adjuvant platinum-based combination chemotherapy which results in only a modest 4%-5% improvement in survival versus observation.

Given these modest results, as in the neoadjuvant space, investigators have looked at the benefit of adding immunotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy. One such study has been reported. IMpower 010 randomly assigned patients with completely resected stage IB (tumors ≥ 4 cm) to IIIA NSCLC, whose tumor cells expressed at least 1% PD-L1, to receive adjuvant atezolizumab or best supportive care after adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. In the stage II-IIIA population whose tumors expressed PD-L1 on 1% or more of tumor cells, 3-year DFS rates were 60% and 48% in the atezolizumab and best supportive care arms, respectively (hazard ratio, 0·66 P =·.0039). In all patients in the stage II-IIIA population, the 3-year DFS rates were 56% in the atezolizumab group and 49% in the best supportive care group, (HR, 0.79; P = .020).

KEYNOTE-091, reported at the 2021 annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology, randomized early-stage NSCLC patients following complete resection and adjuvant chemotherapy to pembrolizumab or placebo. Median DFS for the overall population was 53.6 months for patients in the pembro arm versus 42 months in the placebo arm (HR, 0.76; P = .0014). Interestingly, the benefit was not seen in patients with PD-L1 with at least 50%, where the 18-month DFS rate was 71.7% in the pembro arm and 70.2% in the placebo arm (HR, 0.82; P = .14). Although the contradictory results of PD-L1 as a biomarker is puzzling, I think we can agree that the addition of immunotherapy following adjuvant chemotherapy improves outcomes compared to adjuvant chemotherapy alone.

What to do when a patient presents with resectable disease?

Cross-trial comparisons are fraught with danger. Until we have a phase 3 study comparing concurrent neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy with concurrent adjuvant chemo/immunotherapy, I do not think we can answer the question “which is better?” However, there are some caveats to keep in mind when deciding on which approach to recommend to our patients: First, neoadjuvant treatment requires biomarker testing to ensure the patient does not have EGFR or ALK mutations. This will necessitate a delay in the operation. Will patients be willing to wait? Will the surgeon? Or, would patients prefer to proceed with surgery while the results are pending? Yes, neoadjuvant therapy gives you information regarding the pCR rate, but does that help you in subsequent management of the patient? We do not know.

Secondly, the two adjuvant studies used adjuvant chemotherapy followed by adjuvant immunotherapy, as contrasted to the neoadjuvant study which used concurrent chemo/immunotherapy. Given the longer duration of treatment in postoperative sequential adjuvant studies, there tends to be more drop off because of patients being unwilling or unfit postoperatively to receive long courses of therapy. In IMpower 010, 1,269 patients completed adjuvant chemotherapy; 1,005 were randomized, and of the 507 assigned to the atezolizumab/chemo group, only 323 completed treatment.

Finally, we must beware of using neoadjuvant chemo/immunotherapy to “down-stage” a patient. KEYNOTE-091 included patients with IIIA disease and no benefit to adjuvant chemotherapy followed by immunotherapy was found in this subgroup of patients, which leads me to wonder if these patients were appropriately selected as surgical candidates. In the NADIM II trials, 9 of 29 patients on the neoadjuvant chemotherapy were not resected.

So, many questions remain. In addition to the ones we’ve raised, there is a clear and immediate need for predictive and prognostic biomarkers. In the NADIM II trial, PD-L1 expression was a predictive biomarker of response. The pCR rate for patients with a PD-L1 tumor expression of less than 1%, 1%-49%, and 50% or higher was 15%, 41.7%, and 61.1%, respectively. However, in KEYNOTE-091, the benefit was not seen in patients with PD-L1 of at least than 50%, where the 18-month DFS rate was 71.7% in the pembro arm and 70.2% in the placebo arm.

Another possible biomarker: circulating tumor DNA. In the first NADIM study, three low pretreatment levels of ctDNA were significantly associated with improved progression-free survival and overall survival (HR, 0.20 and HR, 0.07, respectively). Although clinical response did not predict survival outcomes, undetectable ctDNA levels after neoadjuvant treatment were significantly associated with progression-free survival and overall survival (HR, 0.26 and HR0.04, respectively). Similarly, in CheckMate 816, clearance of ctDNA was associated with longer EFS in patients with ctDNA clearance than in those without ctDNA clearance in both the nivolumab/chemotherapy group (HR, 0.60) and the chemotherapy-alone group (HR, 0.63).

Hopefully, ASCO 2023 will provide more answers.

Dr. Schiller is a medical oncologist and founding member of Oncologists United for Climate and Health. She is a former board member of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and a current board member of the Lung Cancer Research Foundation.

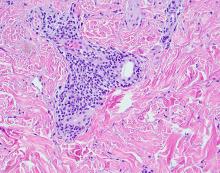

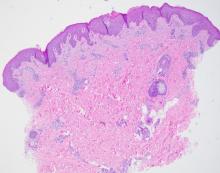

Racial disparities in endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic malignancy and is the fourth most common cancer seen in U.S. women. It is the only major cancer that has continued to see a rise in incidence and mortality for the past 2 decades, and it is anticipated that nearly 66,000 new cases of EC will be diagnosed this year with 12,550 deaths.1 Given that the well-established risk factors for developing EC including obesity, diabetes, and insulin resistance, the obesity epidemic is indisputably playing a significant role in the increasing incidence.

Historically, White women were thought to have the highest incidence of EC; however, this incidence rate did not account for hysterectomy prevalence, which can vary widely by numerous factors including age, race, ethnicity, and geographic region. When correcting EC incidence rates for prevalence of hysterectomy, Black women have had the highest incidence of EC since 2007, and rates continue to climb.2 In fact, the average annual percent change (APC) in EC incidence from 2000 to 2015 was stable for White women at 0.2% while Black women had a near order of magnitude greater APC at 2.1%.2

Differing incidence rates of EC can also be seen by histologic subtype. Endometrioid EC is the more common and less lethal histology of EC that often coincides with the type I classification of EC. These tumors are estrogen driven; therefore, they are associated with conditions resulting in excess estrogen (for example, anovulation, obesity, and hyperlipidemia). Nonendometrioid histologies, primarily composed of serous tumors, are more rare, are typically more aggressive, are not estrogen driven, and are commonly classified as type II tumors. Racial differences between type I and type II tumors are seen with White women more commonly being diagnosed with type I tumors while Black women more typically have type II tumors. White women have the greatest incidence rate of endometrioid EC with an APC that remained relatively unchanged from 2000 to 2015. Black women’s APC in incidence rate of endometrioid EC has increased during this same period at 1.3%. For nonendometrioid tumors, an increasing incidence is seen in all races and ethnicities; however, Black women have a much higher incidence of these tumors, with a rate that continues to increase at an APC of 3.2%.2

EC incidence is increasing with a particularly concerning rise in those who report Black race, but are these same disparities being seen in EC mortality? Unfortunately, drastic disparities are seen in survival data for Black women afflicted with EC. Black patients are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced or metastatic EC and less likely to be diagnosed with localized tumors. While being diagnosed with a more advanced stage of disease does affect survival in EC, Black patients have worse survival regardless of stage of disease at the time of diagnosis.1 As discussed earlier, the more aggressive type II tumors are composed of nonendometrioid histologies and are more common in Black women. This could lead to the false assumption that these higher-risk tumors are why Black women are disproportionately dying from EC; however, when examining survival by histologic subtype, Black women are more frequently dying from the lower-risk endometrioid EC regardless of stage of disease. The same disparate survival outcomes are also seen in nonendometrioid histologies.2 Thus, Black patients have the lowest survival rates irrespective of stage at diagnosis or histologic subtype.

The disparities seen in EC mortality are not new. They can be seen in data for over 30 years and are only widening. While there has been an increase in mortality rates from EC across all races and ethnicities from 2015 to 2019 compared with 1990 to 1994, the mortality rate ratio for Black women compared with White women has increased from 1.83 in 1990-1994 to 1.98 in 2015-2019.3 In the early 1990s, the risk of death from ovarian cancer was twice that of EC. The mortality of EC is now similar to that of ovarian cancer. This threshold in mortality ratio of EC to ovarian cancer has already been seen in Black women, who have experienced greater mortality in EC compared with ovarian cancer since 2005. In fact, the EC mortality of Black women in 2019 was similar to the mortality of White women with ovarian cancer nearly 30 years ago.3

Decades of data have demonstrated the glaring racial disparities seen in EC, and yet, no significant progress has been made in addressing this inequity. Oncology research is now beginning to move beyond describing these differences to a strategy of achieving equitable cancer care. While the study frameworks and novel investigations aimed at addressing the disparities in EC is outside the scope of this article, disparities in clinical trial enrollment continue to exist.

A recent example can be seen in the practice-changing KEYNOTE-775 trial, which led to the Food and Drug Administration approval of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in EC treatment.4 A total of 827 patients with EC that progressed or recurred following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy were enrolled in this multinational, multicenter trial. Thirty-one (3.7%) of the patients enrolled were Black. Of those who were enrolled in the United States, 14% were Black. The authors report that this proportion of Black patients in the United States is consistent with 2020 census data, which reported 13.4% of people identified as Black. However, using census data as a benchmark for equitable enrollment is inappropriate. Certain demographic groups are historically more difficult to count, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the challenge in obtaining an accurate count through job loss, government distrust, and access restrictions resulting in an estimated net undercount of 2.45% in those who report Black race.5 Composition of trial enrollment should mirror the population that will be affected by the study results. As advanced EC disproportionately affects Black patients, their enrollment must be higher in these pivotal trials. How else are we to know if these novel therapeutics will work in the population that is most afflicted by EC?

Future studies must account for socioeconomic factors while acknowledging the role of social determinants of health. It is imperative that we use the knowledge that race is a social construct created to control access to power and that there are biologic responses to environmental stresses, including that of racism, affecting health and disease. Changes at every level, from individual practitioners up to federal policies, will need to be enacted or else the unacceptable status quo will continue.

Dr. Burkett is a clinical fellow in the division of gynecologic oncology, department of obstetrics and gynecology, at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

1. Siegel RL et al. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7-33.

2. Clarke MA et al. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1895-908.

3. Giaquinto AN et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:440-2.

4. Makker V et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:437-48.

5. Elliott D et al. Simulating the 2020 Census: Miscounts and the fairness of outcomes. Urban Institute; 2021.

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecologic malignancy and is the fourth most common cancer seen in U.S. women. It is the only major cancer that has continued to see a rise in incidence and mortality for the past 2 decades, and it is anticipated that nearly 66,000 new cases of EC will be diagnosed this year with 12,550 deaths.1 Given that the well-established risk factors for developing EC including obesity, diabetes, and insulin resistance, the obesity epidemic is indisputably playing a significant role in the increasing incidence.

Historically, White women were thought to have the highest incidence of EC; however, this incidence rate did not account for hysterectomy prevalence, which can vary widely by numerous factors including age, race, ethnicity, and geographic region. When correcting EC incidence rates for prevalence of hysterectomy, Black women have had the highest incidence of EC since 2007, and rates continue to climb.2 In fact, the average annual percent change (APC) in EC incidence from 2000 to 2015 was stable for White women at 0.2% while Black women had a near order of magnitude greater APC at 2.1%.2