User login

Observation versus inpatient status

A dilemma for hospitalists and patients

A federal effort to reduce health care expenditures has left many older Medicare recipients experiencing the sticker shock of “observation status.” Patients who are not sick enough to meet inpatient admission criteria, however, still require hospitalization, and may be placed under Medicare observation care.

Seniors can get frustrated, confused, and anxious as their status can be changed while they are in the hospital, and they may receive large medical bills after they are discharged. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “3-day rule” mandates that Medicare will not pay for skilled nursing facility care unless the patient is admitted as an “inpatient” for at least 3 days. Observation days do not count towards this 3-day hospital stay.

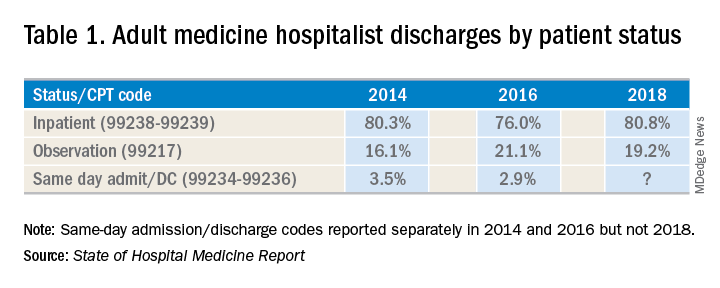

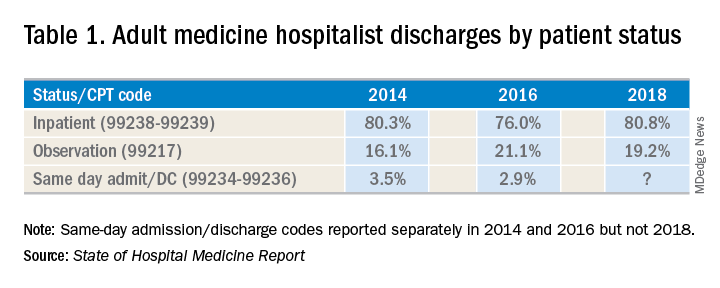

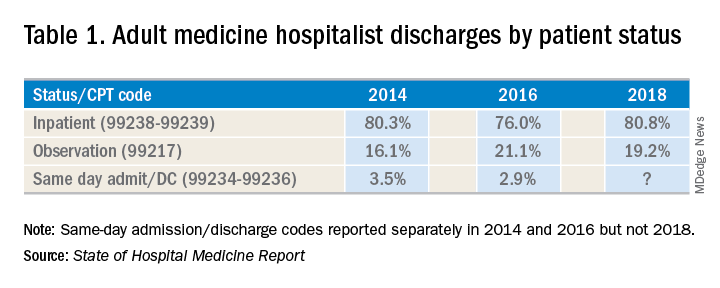

There has been an increase in outpatient services over the years since 2006. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) highlights the percentage of discharges based on hospitalists’ billed Current Procedural Terminology codes. Codes 99217 (observation discharge) and 99238-99239 (inpatient discharge) were used to calculate the percentages. 80.7% of adult medicine hospitalist discharges were coded using inpatient discharge codes, while 19.3% of patients were discharged with observation discharge codes.

In the 2016 SoHM report, the ratio was 76.0% inpatient and 21.1% observation codes and in the 2014 report we saw 80.3% inpatient and 16.1% observation discharges (see table 1). But in both of those surveys, same-day admission/discharge codes were also separately reported, which did not occur in 2018. That makes year-over-year comparison of the data challenging.

Interestingly, the 2017 CMS data on Evaluation and Management Codes by Specialty for the first time included separate data for hospitalists, based on hospitalists who credentialed with Medicare using the new C6 specialty code. Based on that data, when looking only at inpatient (99238-99239) and observation (99217) codes, 83% of the discharges were inpatient and 17% were observation.

Physicians feel the pressure of strained patient-physician relationships as a consequence of patients feeling the brunt of the financing gap related to observation status. Patients often feel they were not warned adequately about the financial ramifications of observation status. Even if Medicare beneficiaries have received the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice, outlined by the Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility Act, they have no rights to appeal.

Currently Medicare beneficiaries admitted as inpatients only incur a Part A deductible; they are not liable for tests, procedures, and nursing care. On the other hand, in observation status all services are billed separately. For Medicare Part B services (which covers observation care) patients must pay 20% of services after the Part B deductible, which could result in a huge financial burden. Costs for skilled nursing facilities, when they are not covered by Medicare Part A, because of the 3-day rule, can easily go up to $20,000 or more. Medicare beneficiaries have no cap on costs for an observation stay. In some cases, hospitals have to apply a condition code 44 and retroactively change the stay to observation status.

I attended the 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference in Washington. Hospitalists from all parts of the country advocated on Capitol Hill against the “observation bill,” and “meet and greets” with congressional representatives increased their opposition to the bill. These efforts may work in favor of protecting patients from surprise medical bills. Hospital medicine physicians are on the front lines for providing health care in the hospital setting; they have demanded a fix to this legislative loophole which brings high out of pocket costs to our nation’s most vulnerable seniors. The observation status “2-midnight rule” utilized by CMS has increased financial barriers and decreased access to postacute care, affecting the provision of high-quality care for patients.

My hospital has a utilization review committee which reviews all cases to determine the appropriateness of an inpatient versus an observation designation. (An interesting question is whether the financial resources used to support this additional staff could be better assigned to provide high-quality care.) Distribution of these patients is determined on very specific criteria as outlined by Medicare. Observation is basically considered a billing method implemented by payers to decrease dollars paid to acute care hospitals for inpatient care. It pertains to admission status, not to the level of care provided in the hospital. Unfortunately, it is felt that no two payers define observation the same way. A few examples of common observation diagnoses are chest pain, abdominal pain, syncope, and migraine headache; in other words, patients with diagnoses where it is suspected that a less than 24-hour stay in the hospital could be sufficient.

Observation care is increasing and can sometimes contribute to work flow impediments and frustrations in hospitalists; thus, hospitalists are demanding reform. It has been proposed that observation could be eliminated altogether by creating a payment blend of inpatient/outpatient rates. Another option could be to assign lower Diagnosis Related Group coding to lower acuity disease processes, instead of separate observation reimbursement.

Patients and doctors lament that “Once you are in the hospital, you are admitted!” I don’t know the right answer that would solve the observation versus inpatient dilemma, but it is intriguing to consider changes in policy that might focus on the complete elimination of observation status.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

A dilemma for hospitalists and patients

A dilemma for hospitalists and patients

A federal effort to reduce health care expenditures has left many older Medicare recipients experiencing the sticker shock of “observation status.” Patients who are not sick enough to meet inpatient admission criteria, however, still require hospitalization, and may be placed under Medicare observation care.

Seniors can get frustrated, confused, and anxious as their status can be changed while they are in the hospital, and they may receive large medical bills after they are discharged. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “3-day rule” mandates that Medicare will not pay for skilled nursing facility care unless the patient is admitted as an “inpatient” for at least 3 days. Observation days do not count towards this 3-day hospital stay.

There has been an increase in outpatient services over the years since 2006. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) highlights the percentage of discharges based on hospitalists’ billed Current Procedural Terminology codes. Codes 99217 (observation discharge) and 99238-99239 (inpatient discharge) were used to calculate the percentages. 80.7% of adult medicine hospitalist discharges were coded using inpatient discharge codes, while 19.3% of patients were discharged with observation discharge codes.

In the 2016 SoHM report, the ratio was 76.0% inpatient and 21.1% observation codes and in the 2014 report we saw 80.3% inpatient and 16.1% observation discharges (see table 1). But in both of those surveys, same-day admission/discharge codes were also separately reported, which did not occur in 2018. That makes year-over-year comparison of the data challenging.

Interestingly, the 2017 CMS data on Evaluation and Management Codes by Specialty for the first time included separate data for hospitalists, based on hospitalists who credentialed with Medicare using the new C6 specialty code. Based on that data, when looking only at inpatient (99238-99239) and observation (99217) codes, 83% of the discharges were inpatient and 17% were observation.

Physicians feel the pressure of strained patient-physician relationships as a consequence of patients feeling the brunt of the financing gap related to observation status. Patients often feel they were not warned adequately about the financial ramifications of observation status. Even if Medicare beneficiaries have received the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice, outlined by the Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility Act, they have no rights to appeal.

Currently Medicare beneficiaries admitted as inpatients only incur a Part A deductible; they are not liable for tests, procedures, and nursing care. On the other hand, in observation status all services are billed separately. For Medicare Part B services (which covers observation care) patients must pay 20% of services after the Part B deductible, which could result in a huge financial burden. Costs for skilled nursing facilities, when they are not covered by Medicare Part A, because of the 3-day rule, can easily go up to $20,000 or more. Medicare beneficiaries have no cap on costs for an observation stay. In some cases, hospitals have to apply a condition code 44 and retroactively change the stay to observation status.

I attended the 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference in Washington. Hospitalists from all parts of the country advocated on Capitol Hill against the “observation bill,” and “meet and greets” with congressional representatives increased their opposition to the bill. These efforts may work in favor of protecting patients from surprise medical bills. Hospital medicine physicians are on the front lines for providing health care in the hospital setting; they have demanded a fix to this legislative loophole which brings high out of pocket costs to our nation’s most vulnerable seniors. The observation status “2-midnight rule” utilized by CMS has increased financial barriers and decreased access to postacute care, affecting the provision of high-quality care for patients.

My hospital has a utilization review committee which reviews all cases to determine the appropriateness of an inpatient versus an observation designation. (An interesting question is whether the financial resources used to support this additional staff could be better assigned to provide high-quality care.) Distribution of these patients is determined on very specific criteria as outlined by Medicare. Observation is basically considered a billing method implemented by payers to decrease dollars paid to acute care hospitals for inpatient care. It pertains to admission status, not to the level of care provided in the hospital. Unfortunately, it is felt that no two payers define observation the same way. A few examples of common observation diagnoses are chest pain, abdominal pain, syncope, and migraine headache; in other words, patients with diagnoses where it is suspected that a less than 24-hour stay in the hospital could be sufficient.

Observation care is increasing and can sometimes contribute to work flow impediments and frustrations in hospitalists; thus, hospitalists are demanding reform. It has been proposed that observation could be eliminated altogether by creating a payment blend of inpatient/outpatient rates. Another option could be to assign lower Diagnosis Related Group coding to lower acuity disease processes, instead of separate observation reimbursement.

Patients and doctors lament that “Once you are in the hospital, you are admitted!” I don’t know the right answer that would solve the observation versus inpatient dilemma, but it is intriguing to consider changes in policy that might focus on the complete elimination of observation status.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

A federal effort to reduce health care expenditures has left many older Medicare recipients experiencing the sticker shock of “observation status.” Patients who are not sick enough to meet inpatient admission criteria, however, still require hospitalization, and may be placed under Medicare observation care.

Seniors can get frustrated, confused, and anxious as their status can be changed while they are in the hospital, and they may receive large medical bills after they are discharged. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “3-day rule” mandates that Medicare will not pay for skilled nursing facility care unless the patient is admitted as an “inpatient” for at least 3 days. Observation days do not count towards this 3-day hospital stay.

There has been an increase in outpatient services over the years since 2006. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) highlights the percentage of discharges based on hospitalists’ billed Current Procedural Terminology codes. Codes 99217 (observation discharge) and 99238-99239 (inpatient discharge) were used to calculate the percentages. 80.7% of adult medicine hospitalist discharges were coded using inpatient discharge codes, while 19.3% of patients were discharged with observation discharge codes.

In the 2016 SoHM report, the ratio was 76.0% inpatient and 21.1% observation codes and in the 2014 report we saw 80.3% inpatient and 16.1% observation discharges (see table 1). But in both of those surveys, same-day admission/discharge codes were also separately reported, which did not occur in 2018. That makes year-over-year comparison of the data challenging.

Interestingly, the 2017 CMS data on Evaluation and Management Codes by Specialty for the first time included separate data for hospitalists, based on hospitalists who credentialed with Medicare using the new C6 specialty code. Based on that data, when looking only at inpatient (99238-99239) and observation (99217) codes, 83% of the discharges were inpatient and 17% were observation.

Physicians feel the pressure of strained patient-physician relationships as a consequence of patients feeling the brunt of the financing gap related to observation status. Patients often feel they were not warned adequately about the financial ramifications of observation status. Even if Medicare beneficiaries have received the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice, outlined by the Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility Act, they have no rights to appeal.

Currently Medicare beneficiaries admitted as inpatients only incur a Part A deductible; they are not liable for tests, procedures, and nursing care. On the other hand, in observation status all services are billed separately. For Medicare Part B services (which covers observation care) patients must pay 20% of services after the Part B deductible, which could result in a huge financial burden. Costs for skilled nursing facilities, when they are not covered by Medicare Part A, because of the 3-day rule, can easily go up to $20,000 or more. Medicare beneficiaries have no cap on costs for an observation stay. In some cases, hospitals have to apply a condition code 44 and retroactively change the stay to observation status.

I attended the 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference in Washington. Hospitalists from all parts of the country advocated on Capitol Hill against the “observation bill,” and “meet and greets” with congressional representatives increased their opposition to the bill. These efforts may work in favor of protecting patients from surprise medical bills. Hospital medicine physicians are on the front lines for providing health care in the hospital setting; they have demanded a fix to this legislative loophole which brings high out of pocket costs to our nation’s most vulnerable seniors. The observation status “2-midnight rule” utilized by CMS has increased financial barriers and decreased access to postacute care, affecting the provision of high-quality care for patients.

My hospital has a utilization review committee which reviews all cases to determine the appropriateness of an inpatient versus an observation designation. (An interesting question is whether the financial resources used to support this additional staff could be better assigned to provide high-quality care.) Distribution of these patients is determined on very specific criteria as outlined by Medicare. Observation is basically considered a billing method implemented by payers to decrease dollars paid to acute care hospitals for inpatient care. It pertains to admission status, not to the level of care provided in the hospital. Unfortunately, it is felt that no two payers define observation the same way. A few examples of common observation diagnoses are chest pain, abdominal pain, syncope, and migraine headache; in other words, patients with diagnoses where it is suspected that a less than 24-hour stay in the hospital could be sufficient.

Observation care is increasing and can sometimes contribute to work flow impediments and frustrations in hospitalists; thus, hospitalists are demanding reform. It has been proposed that observation could be eliminated altogether by creating a payment blend of inpatient/outpatient rates. Another option could be to assign lower Diagnosis Related Group coding to lower acuity disease processes, instead of separate observation reimbursement.

Patients and doctors lament that “Once you are in the hospital, you are admitted!” I don’t know the right answer that would solve the observation versus inpatient dilemma, but it is intriguing to consider changes in policy that might focus on the complete elimination of observation status.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

Critics say hospital price transparency proposal ‘misses the mark’

A proposal by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to require full price transparency, including the disclosure of both list prices and payer-negotiated prices, is already receiving pushback.

Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association, said in a statement that “mandating disclosure of negotiated rates between insurers and hospitals is the wrong approach,” adding that it “could seriously limit the choices available to patients in the private market and fuel anticompetitive behavior among commercial health insurers in an already highly concentrated insurance industry.”

The requirement for hospital price transparency was posted online July 29 as part of the proposed annual update to the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS) for 2020. It is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Aug. 9.

CMS is proposing, beginning in calendar year 2020, that hospitals make publicly available their “standard charges,” defined as the gross – or list – price of for all services provided by the hospital, as well as payer-specific negotiated prices. To allow for price comparisons, prices would be posted on the Internet in a machine-readable file that includes common billing or accounting codes and a description of the item of service being delivered.

Additionally, hospitals must make payer-specific negotiated prices for “shoppable” services, defined as services that can be scheduled in advance – such as x-rays, outpatient visits, imaging and laboratory tests, or bundled services like a cesarean delivery with pre- and postdelivery care – in a consumer-friendly manner.

“As deductibles rise and with 29 million uninsured, patients have the right to know the price of health care services so they can shop around for the best deal,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 press conference. “In fact, a recent poll showed that the majority of Americans have tried to get pricing information before getting care, but have found it challenging to find that information.”

She noted that patients may see prices that range from 150% of Medicare rates to more than 400% for the same service.

Hospitals will need to display at least 300 shoppable services, including 70 that are CMS selected and 230 that are hospital selected, according to a fact sheet outlining this and other proposed OPPS updates for 2020.

“If a hospital does not provide one or more of the 70 CMS selected shoppable services, the hospital must select additional shoppable services such that the total number of shoppable services is at least 300,” the fact sheet states.

Information on pricing will be required to be updated at least annually.

CMS is including enforcement tools as part of the proposal, including fines to hospitals for noncompliance.

“Price transparency creates a marketplace where providers compete on the basis of cost and quality that will lower cost,” Ms. Verma said.

However, that notion has been challenged by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

Matt Eyles, president and CEO of AHIP said in a statement that “multiple experts, including the Federal Trade Commission, agree that disclosing privately negotiated rates will make it harder to bargain for lower rates, creating a floor, not a ceiling, for the prices that hospitals would be willing to accept. Publicly disclosing competitively negotiated, proprietary rates will push prices and premiums higher, not lower, for consumers, patients, and taxpayers.”

Mr. Pollack of the American Hospital Association agreed. “While we support transparency, [this] proposal misses the mark, exceeds the Administration’s legal authority, and should be abandoned.”

Ms. Verma said she believed the agency had legal authority to impose this requirement and is not worried about possible lawsuits that could challenge this provision.

“This administration is not afraid of those things,” she said. “We are not about protecting the status quo when it doesn’t work for patients.”

A proposal by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to require full price transparency, including the disclosure of both list prices and payer-negotiated prices, is already receiving pushback.

Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association, said in a statement that “mandating disclosure of negotiated rates between insurers and hospitals is the wrong approach,” adding that it “could seriously limit the choices available to patients in the private market and fuel anticompetitive behavior among commercial health insurers in an already highly concentrated insurance industry.”

The requirement for hospital price transparency was posted online July 29 as part of the proposed annual update to the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS) for 2020. It is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Aug. 9.

CMS is proposing, beginning in calendar year 2020, that hospitals make publicly available their “standard charges,” defined as the gross – or list – price of for all services provided by the hospital, as well as payer-specific negotiated prices. To allow for price comparisons, prices would be posted on the Internet in a machine-readable file that includes common billing or accounting codes and a description of the item of service being delivered.

Additionally, hospitals must make payer-specific negotiated prices for “shoppable” services, defined as services that can be scheduled in advance – such as x-rays, outpatient visits, imaging and laboratory tests, or bundled services like a cesarean delivery with pre- and postdelivery care – in a consumer-friendly manner.

“As deductibles rise and with 29 million uninsured, patients have the right to know the price of health care services so they can shop around for the best deal,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 press conference. “In fact, a recent poll showed that the majority of Americans have tried to get pricing information before getting care, but have found it challenging to find that information.”

She noted that patients may see prices that range from 150% of Medicare rates to more than 400% for the same service.

Hospitals will need to display at least 300 shoppable services, including 70 that are CMS selected and 230 that are hospital selected, according to a fact sheet outlining this and other proposed OPPS updates for 2020.

“If a hospital does not provide one or more of the 70 CMS selected shoppable services, the hospital must select additional shoppable services such that the total number of shoppable services is at least 300,” the fact sheet states.

Information on pricing will be required to be updated at least annually.

CMS is including enforcement tools as part of the proposal, including fines to hospitals for noncompliance.

“Price transparency creates a marketplace where providers compete on the basis of cost and quality that will lower cost,” Ms. Verma said.

However, that notion has been challenged by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

Matt Eyles, president and CEO of AHIP said in a statement that “multiple experts, including the Federal Trade Commission, agree that disclosing privately negotiated rates will make it harder to bargain for lower rates, creating a floor, not a ceiling, for the prices that hospitals would be willing to accept. Publicly disclosing competitively negotiated, proprietary rates will push prices and premiums higher, not lower, for consumers, patients, and taxpayers.”

Mr. Pollack of the American Hospital Association agreed. “While we support transparency, [this] proposal misses the mark, exceeds the Administration’s legal authority, and should be abandoned.”

Ms. Verma said she believed the agency had legal authority to impose this requirement and is not worried about possible lawsuits that could challenge this provision.

“This administration is not afraid of those things,” she said. “We are not about protecting the status quo when it doesn’t work for patients.”

A proposal by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to require full price transparency, including the disclosure of both list prices and payer-negotiated prices, is already receiving pushback.

Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association, said in a statement that “mandating disclosure of negotiated rates between insurers and hospitals is the wrong approach,” adding that it “could seriously limit the choices available to patients in the private market and fuel anticompetitive behavior among commercial health insurers in an already highly concentrated insurance industry.”

The requirement for hospital price transparency was posted online July 29 as part of the proposed annual update to the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS) for 2020. It is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Aug. 9.

CMS is proposing, beginning in calendar year 2020, that hospitals make publicly available their “standard charges,” defined as the gross – or list – price of for all services provided by the hospital, as well as payer-specific negotiated prices. To allow for price comparisons, prices would be posted on the Internet in a machine-readable file that includes common billing or accounting codes and a description of the item of service being delivered.

Additionally, hospitals must make payer-specific negotiated prices for “shoppable” services, defined as services that can be scheduled in advance – such as x-rays, outpatient visits, imaging and laboratory tests, or bundled services like a cesarean delivery with pre- and postdelivery care – in a consumer-friendly manner.

“As deductibles rise and with 29 million uninsured, patients have the right to know the price of health care services so they can shop around for the best deal,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 press conference. “In fact, a recent poll showed that the majority of Americans have tried to get pricing information before getting care, but have found it challenging to find that information.”

She noted that patients may see prices that range from 150% of Medicare rates to more than 400% for the same service.

Hospitals will need to display at least 300 shoppable services, including 70 that are CMS selected and 230 that are hospital selected, according to a fact sheet outlining this and other proposed OPPS updates for 2020.

“If a hospital does not provide one or more of the 70 CMS selected shoppable services, the hospital must select additional shoppable services such that the total number of shoppable services is at least 300,” the fact sheet states.

Information on pricing will be required to be updated at least annually.

CMS is including enforcement tools as part of the proposal, including fines to hospitals for noncompliance.

“Price transparency creates a marketplace where providers compete on the basis of cost and quality that will lower cost,” Ms. Verma said.

However, that notion has been challenged by America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP).

Matt Eyles, president and CEO of AHIP said in a statement that “multiple experts, including the Federal Trade Commission, agree that disclosing privately negotiated rates will make it harder to bargain for lower rates, creating a floor, not a ceiling, for the prices that hospitals would be willing to accept. Publicly disclosing competitively negotiated, proprietary rates will push prices and premiums higher, not lower, for consumers, patients, and taxpayers.”

Mr. Pollack of the American Hospital Association agreed. “While we support transparency, [this] proposal misses the mark, exceeds the Administration’s legal authority, and should be abandoned.”

Ms. Verma said she believed the agency had legal authority to impose this requirement and is not worried about possible lawsuits that could challenge this provision.

“This administration is not afraid of those things,” she said. “We are not about protecting the status quo when it doesn’t work for patients.”

Key clinical point: CMS proposes complete transparency in hospital prices.

Major finding: Hospitals would be required to make public the list prices, as well as all payer-negotiated prices.

Study details: CMS asserts that the disclosure of pricing data will lead to reduced prices through market competition.

Disclosures: CMS, as issuer of the proposed rule, makes no disclosures.

Source: Proposed rule updating the hospital outpatient prospective payment system for 2020.

CMS plans to give MIPS an overhaul

Changes are coming to the Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the Quality Payment Program and officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services say these revisions are aimed at making the transition to value-based care easier for physicians.

The new framework for the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program was included as part of a proposed rule that updated both the physician fee schedule and the Quality Payment Program (QPP) for 2020. The proposed rule was posted online July 29, 2019, and is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Aug. 14. Comments on the rule are due on Sept. 27.

“We are overhauling the Merit-based Incentive Payment System to reduce reporting burden, making sure the measures relevant to clinicians as they move toward value-based care,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 press conference. “Clinicians will now report on fewer, more meaningful measures that are aligned to their specialty or practice area, making it easier to participate in MIPS. We are looking for the public’s input on this new framework so that we can build a better program together.”

CMS is proposing a new conceptual framework called MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs), which would apply to future proposals beginning in the 2021 performance year.

“The goal is to move away from siloed activities and measures and more towards an aligned set of measure options more relevant to a clinician’s scope of practice that is meaningful to patient care,” the CMS said in a fact sheet highlighting the changes.

The framework would align and connect measures across the four performance categories (quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities) and there would be MVP measures for different specialties.

“A clinician or group would be in one MVP associated with their specialty or with a condition, reporting on the same measures and activities as other clinicians and groups in that MVP,” according to the fact sheet.

As part of the proposed framework, the CMS aims to provide “enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.”

In the meantime, the agency is proposing other updates to the program, including adjustments to the weighting of the performance category in 2020. The quality category would drop from 45% to 40%, while the cost category would rise from 15% to 20%. No changes in the weighting of the interoperability (25%) and improvement activities (15%) are proposed.

A number of measures are altered in each of the performance categories, such as increasing the data completeness requirement in the quality category from reporting on 60% of Medicare Part B patients to 70%, changes to patient-centered medical home criteria in the improvement activities performance category, and requiring a yes/no response to the query of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program measure in the promoting interoperability category.

The range of adjustment, by statute for the 2020 performance year, will go up to 9% (plus or minus) depending on the MIPS scoring, expanding from the 7% (plus or minus) range in the 2019 performance year.

A number of provisions of the Quality Payment Program program are proposed to have no change, including the low-volume threshold and opt-in policy, the MIPS performance period, and EHR certification requirements. No quality measures were changed based on changes to clinical guidelines.

The American Medical Association voiced support for the proposal.

“The AMA commends CMS for requesting input on a simplified option that would give physicians the choice to focus on episodes of care rather than following the current, more fragmented approach,” AMA President Patrice Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Making MIPS more clinically relevant and less burdensome is a top priority for the AMA and we believe CMS is taking an important step toward this goal.”

However, AMGA had a different take, expressing concern that MIPS is not becoming a pathway to value-based care.

The group, which represents multispecialty medical groups and integrated health systems, noted that, while the statutory range for bonus payments may be expanding, CMS is estimating that overall payment adjustment will be only 1.4%.

“In light of this significantly reduced adjustment, AMGA is concerned that MIPS is no longer a transition tool to value-based care, but instead represents a regulatory burden that does not support physician group practices and integrated systems of care that are investing in delivery models based on care coordination and improving population health,” AMGA said in a statement. “In addition, this adjustment undermines the intent of Congress to use MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act] to move the health care system to value-based payment.”

Changes are coming to the Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the Quality Payment Program and officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services say these revisions are aimed at making the transition to value-based care easier for physicians.

The new framework for the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program was included as part of a proposed rule that updated both the physician fee schedule and the Quality Payment Program (QPP) for 2020. The proposed rule was posted online July 29, 2019, and is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Aug. 14. Comments on the rule are due on Sept. 27.

“We are overhauling the Merit-based Incentive Payment System to reduce reporting burden, making sure the measures relevant to clinicians as they move toward value-based care,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 press conference. “Clinicians will now report on fewer, more meaningful measures that are aligned to their specialty or practice area, making it easier to participate in MIPS. We are looking for the public’s input on this new framework so that we can build a better program together.”

CMS is proposing a new conceptual framework called MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs), which would apply to future proposals beginning in the 2021 performance year.

“The goal is to move away from siloed activities and measures and more towards an aligned set of measure options more relevant to a clinician’s scope of practice that is meaningful to patient care,” the CMS said in a fact sheet highlighting the changes.

The framework would align and connect measures across the four performance categories (quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities) and there would be MVP measures for different specialties.

“A clinician or group would be in one MVP associated with their specialty or with a condition, reporting on the same measures and activities as other clinicians and groups in that MVP,” according to the fact sheet.

As part of the proposed framework, the CMS aims to provide “enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.”

In the meantime, the agency is proposing other updates to the program, including adjustments to the weighting of the performance category in 2020. The quality category would drop from 45% to 40%, while the cost category would rise from 15% to 20%. No changes in the weighting of the interoperability (25%) and improvement activities (15%) are proposed.

A number of measures are altered in each of the performance categories, such as increasing the data completeness requirement in the quality category from reporting on 60% of Medicare Part B patients to 70%, changes to patient-centered medical home criteria in the improvement activities performance category, and requiring a yes/no response to the query of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program measure in the promoting interoperability category.

The range of adjustment, by statute for the 2020 performance year, will go up to 9% (plus or minus) depending on the MIPS scoring, expanding from the 7% (plus or minus) range in the 2019 performance year.

A number of provisions of the Quality Payment Program program are proposed to have no change, including the low-volume threshold and opt-in policy, the MIPS performance period, and EHR certification requirements. No quality measures were changed based on changes to clinical guidelines.

The American Medical Association voiced support for the proposal.

“The AMA commends CMS for requesting input on a simplified option that would give physicians the choice to focus on episodes of care rather than following the current, more fragmented approach,” AMA President Patrice Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Making MIPS more clinically relevant and less burdensome is a top priority for the AMA and we believe CMS is taking an important step toward this goal.”

However, AMGA had a different take, expressing concern that MIPS is not becoming a pathway to value-based care.

The group, which represents multispecialty medical groups and integrated health systems, noted that, while the statutory range for bonus payments may be expanding, CMS is estimating that overall payment adjustment will be only 1.4%.

“In light of this significantly reduced adjustment, AMGA is concerned that MIPS is no longer a transition tool to value-based care, but instead represents a regulatory burden that does not support physician group practices and integrated systems of care that are investing in delivery models based on care coordination and improving population health,” AMGA said in a statement. “In addition, this adjustment undermines the intent of Congress to use MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act] to move the health care system to value-based payment.”

Changes are coming to the Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the Quality Payment Program and officials at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services say these revisions are aimed at making the transition to value-based care easier for physicians.

The new framework for the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) program was included as part of a proposed rule that updated both the physician fee schedule and the Quality Payment Program (QPP) for 2020. The proposed rule was posted online July 29, 2019, and is scheduled for publication in the Federal Register on Aug. 14. Comments on the rule are due on Sept. 27.

“We are overhauling the Merit-based Incentive Payment System to reduce reporting burden, making sure the measures relevant to clinicians as they move toward value-based care,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 press conference. “Clinicians will now report on fewer, more meaningful measures that are aligned to their specialty or practice area, making it easier to participate in MIPS. We are looking for the public’s input on this new framework so that we can build a better program together.”

CMS is proposing a new conceptual framework called MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs), which would apply to future proposals beginning in the 2021 performance year.

“The goal is to move away from siloed activities and measures and more towards an aligned set of measure options more relevant to a clinician’s scope of practice that is meaningful to patient care,” the CMS said in a fact sheet highlighting the changes.

The framework would align and connect measures across the four performance categories (quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities) and there would be MVP measures for different specialties.

“A clinician or group would be in one MVP associated with their specialty or with a condition, reporting on the same measures and activities as other clinicians and groups in that MVP,” according to the fact sheet.

As part of the proposed framework, the CMS aims to provide “enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.”

In the meantime, the agency is proposing other updates to the program, including adjustments to the weighting of the performance category in 2020. The quality category would drop from 45% to 40%, while the cost category would rise from 15% to 20%. No changes in the weighting of the interoperability (25%) and improvement activities (15%) are proposed.

A number of measures are altered in each of the performance categories, such as increasing the data completeness requirement in the quality category from reporting on 60% of Medicare Part B patients to 70%, changes to patient-centered medical home criteria in the improvement activities performance category, and requiring a yes/no response to the query of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program measure in the promoting interoperability category.

The range of adjustment, by statute for the 2020 performance year, will go up to 9% (plus or minus) depending on the MIPS scoring, expanding from the 7% (plus or minus) range in the 2019 performance year.

A number of provisions of the Quality Payment Program program are proposed to have no change, including the low-volume threshold and opt-in policy, the MIPS performance period, and EHR certification requirements. No quality measures were changed based on changes to clinical guidelines.

The American Medical Association voiced support for the proposal.

“The AMA commends CMS for requesting input on a simplified option that would give physicians the choice to focus on episodes of care rather than following the current, more fragmented approach,” AMA President Patrice Harris, MD, said in a statement. “Making MIPS more clinically relevant and less burdensome is a top priority for the AMA and we believe CMS is taking an important step toward this goal.”

However, AMGA had a different take, expressing concern that MIPS is not becoming a pathway to value-based care.

The group, which represents multispecialty medical groups and integrated health systems, noted that, while the statutory range for bonus payments may be expanding, CMS is estimating that overall payment adjustment will be only 1.4%.

“In light of this significantly reduced adjustment, AMGA is concerned that MIPS is no longer a transition tool to value-based care, but instead represents a regulatory burden that does not support physician group practices and integrated systems of care that are investing in delivery models based on care coordination and improving population health,” AMGA said in a statement. “In addition, this adjustment undermines the intent of Congress to use MACRA [Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act] to move the health care system to value-based payment.”

Key clinical point: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services proposes an overhaul to the Merit-based Incentive Payment System track of the Quality Payment Program.

Major finding: The move is intended to make measures more meaningful to clinicians.

Study details: Measures would be more focused to specialties through Merit-based Incentive Payment System Value Pathways, with all those reporting on a specialty or condition reporting on more streamlined measures.

Disclosures: CMS, as the issuer of the rules, makes no disclosures.

CMS proposes improved E/M payments, additional price transparency for hospitals

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is proposing improvements to physician payments and an overhaul of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program.

In a separate proposal also released on July 29, the agency proposed that hospitals be required to make more pricing information publicly available.

The Medicare Outpatient Prospective Payment System proposed rule for the 2020 annual update would require hospitals to not only publish their gross charges, but also the negotiated price by specific payer for select services that can be scheduled by a patient in advance.

The proposal states "that hospitals make public their standard changes (both gross charges and payer-specific negotiated charges) for all items and services online in a machine-readable format" which would allow them to be included in price transparency tools and electronic health records.

"Hospitals would be required to post all their payer-specific negotiated rates, which are the prices actually paid by insurers," CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 conference call with reporters.

As "deductibles rise and with 29 million uninsured, patients have the right to know the price of health care services so they can shop around for the best deal," she said.

The rule also comes with new enforcement tools so that CMS can ensure hospitals are complying with the rule, should it be finalized.

Hospitals would need to start publishing list prices and payer-specific negotiated prices beginning Jan. 1, 2020.

In a separate proposal to update the physician fee schedule for 2020, CMS is looking to increase Medicare payments in 2021 for evaluation and management (E/M) visits based on recommendations from the American Medical Association's Relative Value Scale Update Committee (AMA-RUC).

With this update, the agency will be "rewarding the time that doctors spend with patients," Administrator Verma said.

The fact sheet on the proposed update to the physician fee schedule also highlights improvements to case management payments, allowing physicians to get paid for case management services if the patient only has one high-risk condition.

"For 2021, we are overhauling the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, to reduce reporting burden, making sure the measures are relevant to clinicians as they move toward value-based care," she said, noting that clinicians would be reporting on fewer, more meaningful measures that are aligned to their specialty or practice area, "making it easier to participate in MIPS."

Look for in depth analysis of both proposals shortly on this website.

gtwachtman@mdedge.com

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is proposing improvements to physician payments and an overhaul of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program.

In a separate proposal also released on July 29, the agency proposed that hospitals be required to make more pricing information publicly available.

The Medicare Outpatient Prospective Payment System proposed rule for the 2020 annual update would require hospitals to not only publish their gross charges, but also the negotiated price by specific payer for select services that can be scheduled by a patient in advance.

The proposal states "that hospitals make public their standard changes (both gross charges and payer-specific negotiated charges) for all items and services online in a machine-readable format" which would allow them to be included in price transparency tools and electronic health records.

"Hospitals would be required to post all their payer-specific negotiated rates, which are the prices actually paid by insurers," CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 conference call with reporters.

As "deductibles rise and with 29 million uninsured, patients have the right to know the price of health care services so they can shop around for the best deal," she said.

The rule also comes with new enforcement tools so that CMS can ensure hospitals are complying with the rule, should it be finalized.

Hospitals would need to start publishing list prices and payer-specific negotiated prices beginning Jan. 1, 2020.

In a separate proposal to update the physician fee schedule for 2020, CMS is looking to increase Medicare payments in 2021 for evaluation and management (E/M) visits based on recommendations from the American Medical Association's Relative Value Scale Update Committee (AMA-RUC).

With this update, the agency will be "rewarding the time that doctors spend with patients," Administrator Verma said.

The fact sheet on the proposed update to the physician fee schedule also highlights improvements to case management payments, allowing physicians to get paid for case management services if the patient only has one high-risk condition.

"For 2021, we are overhauling the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, to reduce reporting burden, making sure the measures are relevant to clinicians as they move toward value-based care," she said, noting that clinicians would be reporting on fewer, more meaningful measures that are aligned to their specialty or practice area, "making it easier to participate in MIPS."

Look for in depth analysis of both proposals shortly on this website.

gtwachtman@mdedge.com

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is proposing improvements to physician payments and an overhaul of the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program.

In a separate proposal also released on July 29, the agency proposed that hospitals be required to make more pricing information publicly available.

The Medicare Outpatient Prospective Payment System proposed rule for the 2020 annual update would require hospitals to not only publish their gross charges, but also the negotiated price by specific payer for select services that can be scheduled by a patient in advance.

The proposal states "that hospitals make public their standard changes (both gross charges and payer-specific negotiated charges) for all items and services online in a machine-readable format" which would allow them to be included in price transparency tools and electronic health records.

"Hospitals would be required to post all their payer-specific negotiated rates, which are the prices actually paid by insurers," CMS Administrator Seema Verma said during a July 29 conference call with reporters.

As "deductibles rise and with 29 million uninsured, patients have the right to know the price of health care services so they can shop around for the best deal," she said.

The rule also comes with new enforcement tools so that CMS can ensure hospitals are complying with the rule, should it be finalized.

Hospitals would need to start publishing list prices and payer-specific negotiated prices beginning Jan. 1, 2020.

In a separate proposal to update the physician fee schedule for 2020, CMS is looking to increase Medicare payments in 2021 for evaluation and management (E/M) visits based on recommendations from the American Medical Association's Relative Value Scale Update Committee (AMA-RUC).

With this update, the agency will be "rewarding the time that doctors spend with patients," Administrator Verma said.

The fact sheet on the proposed update to the physician fee schedule also highlights improvements to case management payments, allowing physicians to get paid for case management services if the patient only has one high-risk condition.

"For 2021, we are overhauling the Merit-based Incentive Payment System, or MIPS, to reduce reporting burden, making sure the measures are relevant to clinicians as they move toward value-based care," she said, noting that clinicians would be reporting on fewer, more meaningful measures that are aligned to their specialty or practice area, "making it easier to participate in MIPS."

Look for in depth analysis of both proposals shortly on this website.

gtwachtman@mdedge.com

MIPS: Nearly all eligible clinicians got a bonus for 2018

Nearly all clinicians who are eligible to participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program did so in 2018; most scored above the performance threshold and got a bonus.

According to the most recent data released this month by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 98.37% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated in the program. In the small/solo practice space, 89.20% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated.

But more importantly, the clinicians are performing better one year later with the program, even though fewer are participating.

In 2018, 97.63% of clinicians scored above the performance threshold, up from 93.12% in 2017. There also were fewer clinicians performing at the threshold (0.42% in 2018, down from 2.01% in the previous year) and fewer clinicians scoring below the threshold (1.95%, down from 4.87%).

Exceeding the performance threshold resulted in a bonus to fee schedule payments in 2018, although the agency did not disclose how much money was paid out in performance bonuses.

MIPS scored “improved across performance categories, with the biggest gain in the Quality performance category, which highlights the program’s effectiveness in measuring outcomes for beneficiaries,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma wrote in a blog post.

The total number of eligible clinicians decreased in 2018 to 916,058, down from 1,057,824 in 2017 because CMS broadened the low-volume threshold to exempt providers from participation requirements.

Participants in a MIPS alternative payment model saw even more success in 2018. Participation increased from 341,220 clinicians in 2017 to 356,828 clinicians in 2018, while virtually all performed above the performance threshold (100% in 2017 and 99.99% in 2018). The 0.01% that was not above the threshold still met it, while no clinicians in either year that participated in a MIPS alternative payment model performed below the threshold.

Participation in the advanced alternative payment model track increased as well, going from 99,026 in 2017 to 183,306 in 2018.

Nearly all clinicians who are eligible to participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program did so in 2018; most scored above the performance threshold and got a bonus.

According to the most recent data released this month by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 98.37% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated in the program. In the small/solo practice space, 89.20% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated.

But more importantly, the clinicians are performing better one year later with the program, even though fewer are participating.

In 2018, 97.63% of clinicians scored above the performance threshold, up from 93.12% in 2017. There also were fewer clinicians performing at the threshold (0.42% in 2018, down from 2.01% in the previous year) and fewer clinicians scoring below the threshold (1.95%, down from 4.87%).

Exceeding the performance threshold resulted in a bonus to fee schedule payments in 2018, although the agency did not disclose how much money was paid out in performance bonuses.

MIPS scored “improved across performance categories, with the biggest gain in the Quality performance category, which highlights the program’s effectiveness in measuring outcomes for beneficiaries,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma wrote in a blog post.

The total number of eligible clinicians decreased in 2018 to 916,058, down from 1,057,824 in 2017 because CMS broadened the low-volume threshold to exempt providers from participation requirements.

Participants in a MIPS alternative payment model saw even more success in 2018. Participation increased from 341,220 clinicians in 2017 to 356,828 clinicians in 2018, while virtually all performed above the performance threshold (100% in 2017 and 99.99% in 2018). The 0.01% that was not above the threshold still met it, while no clinicians in either year that participated in a MIPS alternative payment model performed below the threshold.

Participation in the advanced alternative payment model track increased as well, going from 99,026 in 2017 to 183,306 in 2018.

Nearly all clinicians who are eligible to participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) track of the Quality Payment Program did so in 2018; most scored above the performance threshold and got a bonus.

According to the most recent data released this month by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 98.37% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated in the program. In the small/solo practice space, 89.20% of MIPS-eligible clinicians participated.

But more importantly, the clinicians are performing better one year later with the program, even though fewer are participating.

In 2018, 97.63% of clinicians scored above the performance threshold, up from 93.12% in 2017. There also were fewer clinicians performing at the threshold (0.42% in 2018, down from 2.01% in the previous year) and fewer clinicians scoring below the threshold (1.95%, down from 4.87%).

Exceeding the performance threshold resulted in a bonus to fee schedule payments in 2018, although the agency did not disclose how much money was paid out in performance bonuses.

MIPS scored “improved across performance categories, with the biggest gain in the Quality performance category, which highlights the program’s effectiveness in measuring outcomes for beneficiaries,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma wrote in a blog post.

The total number of eligible clinicians decreased in 2018 to 916,058, down from 1,057,824 in 2017 because CMS broadened the low-volume threshold to exempt providers from participation requirements.

Participants in a MIPS alternative payment model saw even more success in 2018. Participation increased from 341,220 clinicians in 2017 to 356,828 clinicians in 2018, while virtually all performed above the performance threshold (100% in 2017 and 99.99% in 2018). The 0.01% that was not above the threshold still met it, while no clinicians in either year that participated in a MIPS alternative payment model performed below the threshold.

Participation in the advanced alternative payment model track increased as well, going from 99,026 in 2017 to 183,306 in 2018.

MedPAC to Congress: End “incident-to” billing

Incident-to billing occurs when an advanced practicing registered nurse (APRN) or a physician assistant (PA) performs a service but bills Medicare under the physician’s national provider number and receives full physician fee schedule payment, as opposed to 85% of the fee under their own number.

“Medicare beneficiaries increasingly use APRNs and PAs for both primary and specialty care,” according to MedPAC’s June report. “APRNs are furnishing a larger share and a greater variety of services for Medicare beneficiaries than they did in the past. Despite this growing reliance, Medicare does not have a full accounting of the services delivered and beneficiaries treated.”

Currently, identical coding requirements obscure whether the physician or the APRN/PA is providing the service, making it difficult to track volume and quality.

MedPAC estimated that, in 2016, 17% of all nurse practitioners billed all their services as incident to, as that was the number of nurse practitioners who never appeared in the performing provider field for reimbursement but ordered services/drugs or at least one Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary.

Another 34% billed some of their services as incident to as their name appeared at least once in the performing provider they ordered services/drugs for, but ordered more services/drugs for patients where they were not listed as the performing provider.

That leaves just about half (49%) who did not billing their services as incident to.

Requiring APRNs and PAs to bill directly for all of their services provided would update Medicare’s payment policies to better reflect current clinical practice, according to the MedPAC report. “In addition to improving policy makers’ foundational knowledge of who provides care for Medicare beneficiaries, direct billing could create substantial benefits for the Medicare program, beneficiaries, clinicians, and researchers that range from improving the accuracy of the physician fee schedule, reducing expenditures, enhancing program integrity, and allowing for better comparisons between cost and quality of care provided by physicians and APRNs/PAs.”

At their October 2018 meeting, MedPAC commissioners discussed how to appropriately compensate APRNs and PAs, should incident-to billing be eliminated; they ultimately recommended maintaining the 85% rate.

The American Academy of Family Practitioners spoke out against the idea of eliminating incident-to billing.

However, lowering all APRN/PA payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, according to AAFP President Michael Munger, MD.

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said in an interview. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

The MedPAC commissioner saw it differently.

“Most of these clinicians are already paid at this lower rate, and yet the supply of these clinicians has increased dramatically over the last several years,” the report states, adding that the salary differential between these clinicians and physicians “is large enough that employing them likely would remain attractive even if all of their services were paid at 85% of physician fee schedule rates.”

MedPAC, as an advisory body to Congress, makes no disclosures.

Incident-to billing occurs when an advanced practicing registered nurse (APRN) or a physician assistant (PA) performs a service but bills Medicare under the physician’s national provider number and receives full physician fee schedule payment, as opposed to 85% of the fee under their own number.

“Medicare beneficiaries increasingly use APRNs and PAs for both primary and specialty care,” according to MedPAC’s June report. “APRNs are furnishing a larger share and a greater variety of services for Medicare beneficiaries than they did in the past. Despite this growing reliance, Medicare does not have a full accounting of the services delivered and beneficiaries treated.”

Currently, identical coding requirements obscure whether the physician or the APRN/PA is providing the service, making it difficult to track volume and quality.

MedPAC estimated that, in 2016, 17% of all nurse practitioners billed all their services as incident to, as that was the number of nurse practitioners who never appeared in the performing provider field for reimbursement but ordered services/drugs or at least one Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary.

Another 34% billed some of their services as incident to as their name appeared at least once in the performing provider they ordered services/drugs for, but ordered more services/drugs for patients where they were not listed as the performing provider.

That leaves just about half (49%) who did not billing their services as incident to.

Requiring APRNs and PAs to bill directly for all of their services provided would update Medicare’s payment policies to better reflect current clinical practice, according to the MedPAC report. “In addition to improving policy makers’ foundational knowledge of who provides care for Medicare beneficiaries, direct billing could create substantial benefits for the Medicare program, beneficiaries, clinicians, and researchers that range from improving the accuracy of the physician fee schedule, reducing expenditures, enhancing program integrity, and allowing for better comparisons between cost and quality of care provided by physicians and APRNs/PAs.”

At their October 2018 meeting, MedPAC commissioners discussed how to appropriately compensate APRNs and PAs, should incident-to billing be eliminated; they ultimately recommended maintaining the 85% rate.

The American Academy of Family Practitioners spoke out against the idea of eliminating incident-to billing.

However, lowering all APRN/PA payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, according to AAFP President Michael Munger, MD.

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said in an interview. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

The MedPAC commissioner saw it differently.

“Most of these clinicians are already paid at this lower rate, and yet the supply of these clinicians has increased dramatically over the last several years,” the report states, adding that the salary differential between these clinicians and physicians “is large enough that employing them likely would remain attractive even if all of their services were paid at 85% of physician fee schedule rates.”

MedPAC, as an advisory body to Congress, makes no disclosures.

Incident-to billing occurs when an advanced practicing registered nurse (APRN) or a physician assistant (PA) performs a service but bills Medicare under the physician’s national provider number and receives full physician fee schedule payment, as opposed to 85% of the fee under their own number.

“Medicare beneficiaries increasingly use APRNs and PAs for both primary and specialty care,” according to MedPAC’s June report. “APRNs are furnishing a larger share and a greater variety of services for Medicare beneficiaries than they did in the past. Despite this growing reliance, Medicare does not have a full accounting of the services delivered and beneficiaries treated.”

Currently, identical coding requirements obscure whether the physician or the APRN/PA is providing the service, making it difficult to track volume and quality.

MedPAC estimated that, in 2016, 17% of all nurse practitioners billed all their services as incident to, as that was the number of nurse practitioners who never appeared in the performing provider field for reimbursement but ordered services/drugs or at least one Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary.

Another 34% billed some of their services as incident to as their name appeared at least once in the performing provider they ordered services/drugs for, but ordered more services/drugs for patients where they were not listed as the performing provider.

That leaves just about half (49%) who did not billing their services as incident to.

Requiring APRNs and PAs to bill directly for all of their services provided would update Medicare’s payment policies to better reflect current clinical practice, according to the MedPAC report. “In addition to improving policy makers’ foundational knowledge of who provides care for Medicare beneficiaries, direct billing could create substantial benefits for the Medicare program, beneficiaries, clinicians, and researchers that range from improving the accuracy of the physician fee schedule, reducing expenditures, enhancing program integrity, and allowing for better comparisons between cost and quality of care provided by physicians and APRNs/PAs.”

At their October 2018 meeting, MedPAC commissioners discussed how to appropriately compensate APRNs and PAs, should incident-to billing be eliminated; they ultimately recommended maintaining the 85% rate.

The American Academy of Family Practitioners spoke out against the idea of eliminating incident-to billing.

However, lowering all APRN/PA payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, according to AAFP President Michael Munger, MD.

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said in an interview. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

The MedPAC commissioner saw it differently.

“Most of these clinicians are already paid at this lower rate, and yet the supply of these clinicians has increased dramatically over the last several years,” the report states, adding that the salary differential between these clinicians and physicians “is large enough that employing them likely would remain attractive even if all of their services were paid at 85% of physician fee schedule rates.”

MedPAC, as an advisory body to Congress, makes no disclosures.

Medicare may best Medicare Advantage at reducing readmissions

Although earlier research may suggest otherwise, traditional new research suggests.

Researchers used what they described as “a novel data linkage” comparing 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for three major conditions in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for patients using traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage. Those conditions included acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

“Our results contrast with those of previous studies that have reported lower or statistically similar readmission rates for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries,” Orestis A. Panagiotou, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues wrote in a research report published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers linked data from 2011 to 2014 from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

The novel linkage found that HEDIS data underreported hospital admissions for acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia, the researchers stated. “Plans incorrectly excluded hospitalizations that should have qualified for the readmission measure, and readmission rates were substantially higher among incorrectly excluded hospitalizations.”

Despite this, in analyses using the linkage of HEDIS and MedPAR, “Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had higher 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates after [acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia] than did traditional Medicare beneficiaries,” the investigators noted.

Patients in Medicare Advantage had lower unadjusted readmission rates compared with those in traditional Medicare (16.6% vs. 17.1% for acute MI; 21.4% vs. 21.7% for heart failure; and 16.3% vs. 16.4% for pneumonia). After standardization, Medicare Advantage patients had higher readmission rates, compared with those in traditional Medicare (17.2% vs. 16.9% for acute MI; 21.7% vs. 21.4% for heart failure; and 16.5% vs. 16.0% for pneumonia).

The study authors added that, while unadjusted readmission rates were higher for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, “the direction of the difference reversed after standardization. This occurred because Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have, on average, a lower expected readmission risk [that is, they are ‘healthier’].” Prior studies have documented that Medicare Advantage plans enroll beneficiaries with fewer comorbid conditions and that high-cost beneficiaries switch out of Medicare Advantage and into traditional Medicare.

The researchers suggested four reasons for the differences between the results in this study versus others that compared patients using Medicare with those using Medicare Advantage. These were that the new study included a more comprehensive data set, analyses with comorbid conditions “from a well-validated model applied by CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services],” national data focused on three conditions included in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and patients discharged to places other than skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

Authors of an accompanying editorial called for caution to be used in interpreting Medicare Advantage enrollment as causing an increased readmission risk.

“[The] results are sensitive to adjustment for case mix,” wrote Peter Huckfeldt, PhD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Neeraj Sood, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in the editorial published in Annals of Internal Medicine (2019 June 25. doi:10.7326/M19-1599) “Using diagnosis codes on hospital claims for case-mix adjustments may be increasingly perilous. ... To our knowledge, there is no recent evidence comparing the intensity of diagnostic coding between clinically similar [traditional Medicare] and [Medicare Advantage] hospital admissions, but if [traditional Medicare] enrollees were coded more intensively than [Medicare Advantage] enrollees, this could lead to [traditional Medicare] enrollees having lower risk-adjusted readmission rares due to coding practices.”

The editorialists added that using a cross-sectional comparison of Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare patients is concerning because a “key challenge in estimating the effect of [Medicare Advantage] is that enrollment is voluntary,” which can lead to a number of analytical concerns.

The researchers concluded that their findings “are concerning because CMS uses HEDIS performance to construct composite quality ratings and assign payment bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans.

“Our study suggests a need for improved monitoring of the accuracy of HEDIS data,” they noted.

The National Institute on Aging provided the primary funding for this study. A number of the authors received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. No other relevant disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Panagiotou OA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jun 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-1795.

Although earlier research may suggest otherwise, traditional new research suggests.

Researchers used what they described as “a novel data linkage” comparing 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for three major conditions in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for patients using traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage. Those conditions included acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

“Our results contrast with those of previous studies that have reported lower or statistically similar readmission rates for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries,” Orestis A. Panagiotou, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues wrote in a research report published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers linked data from 2011 to 2014 from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

The novel linkage found that HEDIS data underreported hospital admissions for acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia, the researchers stated. “Plans incorrectly excluded hospitalizations that should have qualified for the readmission measure, and readmission rates were substantially higher among incorrectly excluded hospitalizations.”

Despite this, in analyses using the linkage of HEDIS and MedPAR, “Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had higher 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates after [acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia] than did traditional Medicare beneficiaries,” the investigators noted.

Patients in Medicare Advantage had lower unadjusted readmission rates compared with those in traditional Medicare (16.6% vs. 17.1% for acute MI; 21.4% vs. 21.7% for heart failure; and 16.3% vs. 16.4% for pneumonia). After standardization, Medicare Advantage patients had higher readmission rates, compared with those in traditional Medicare (17.2% vs. 16.9% for acute MI; 21.7% vs. 21.4% for heart failure; and 16.5% vs. 16.0% for pneumonia).

The study authors added that, while unadjusted readmission rates were higher for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, “the direction of the difference reversed after standardization. This occurred because Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have, on average, a lower expected readmission risk [that is, they are ‘healthier’].” Prior studies have documented that Medicare Advantage plans enroll beneficiaries with fewer comorbid conditions and that high-cost beneficiaries switch out of Medicare Advantage and into traditional Medicare.