User login

Video-Based Coaching for Dermatology Resident Surgical Education

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

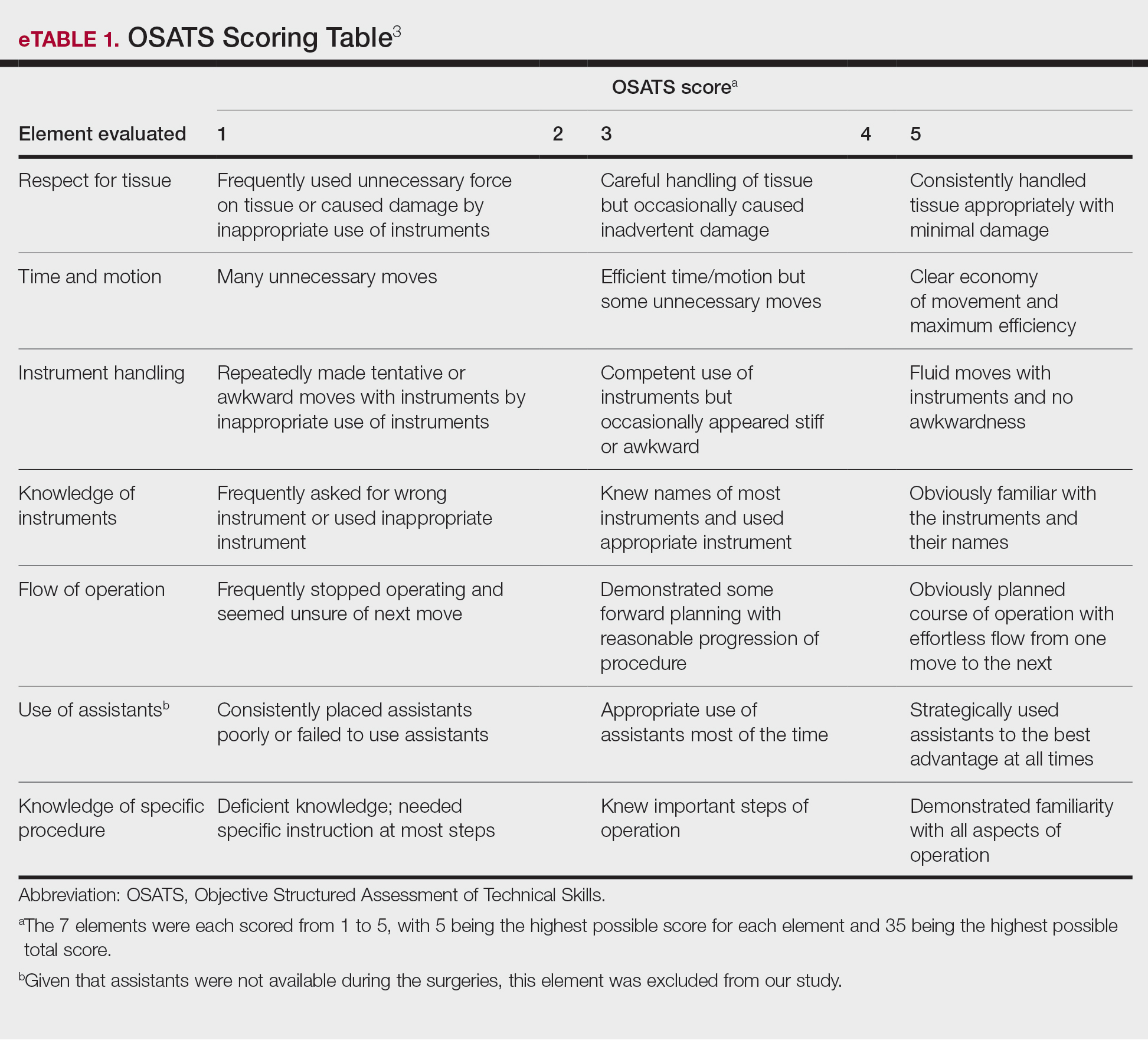

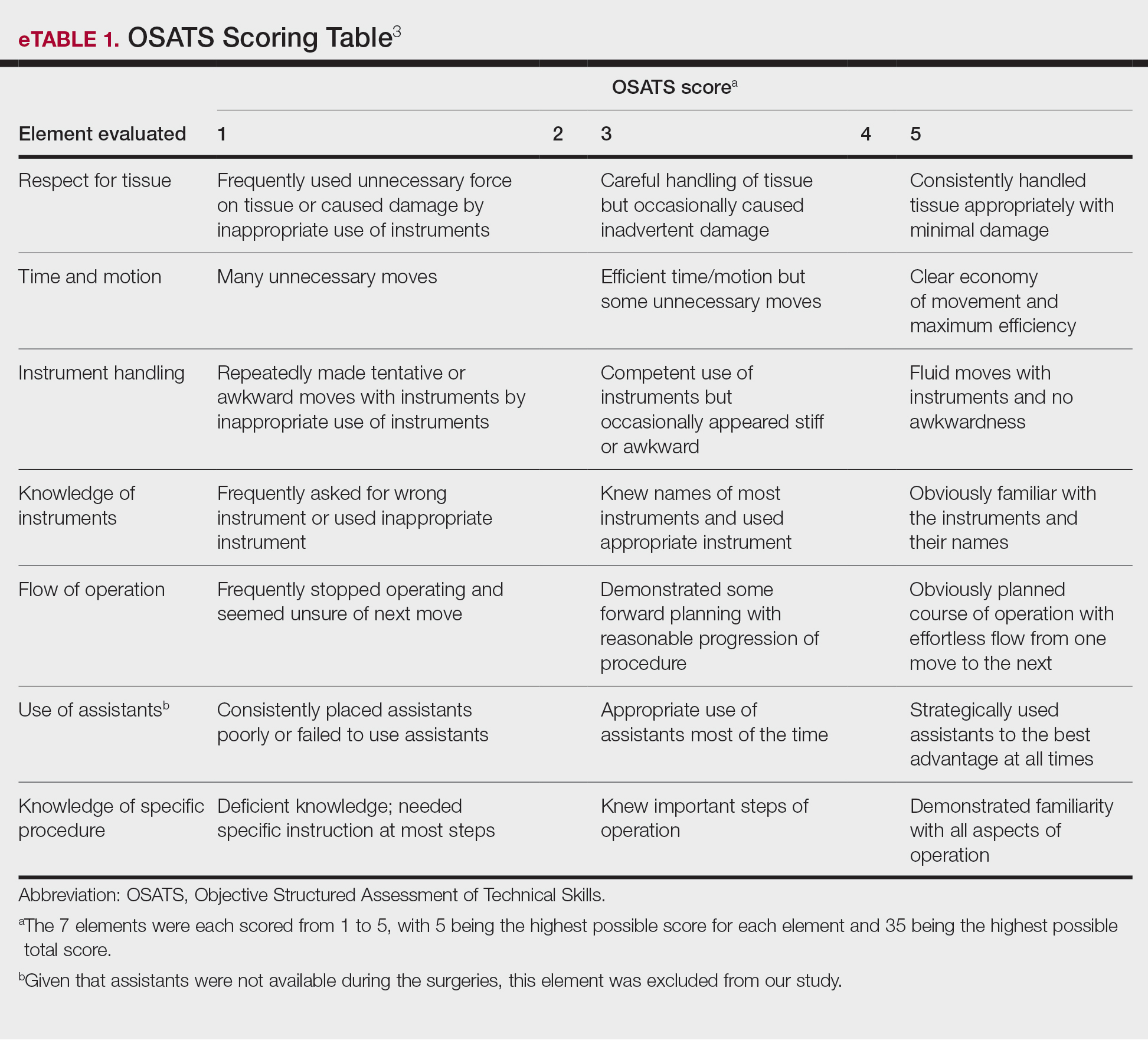

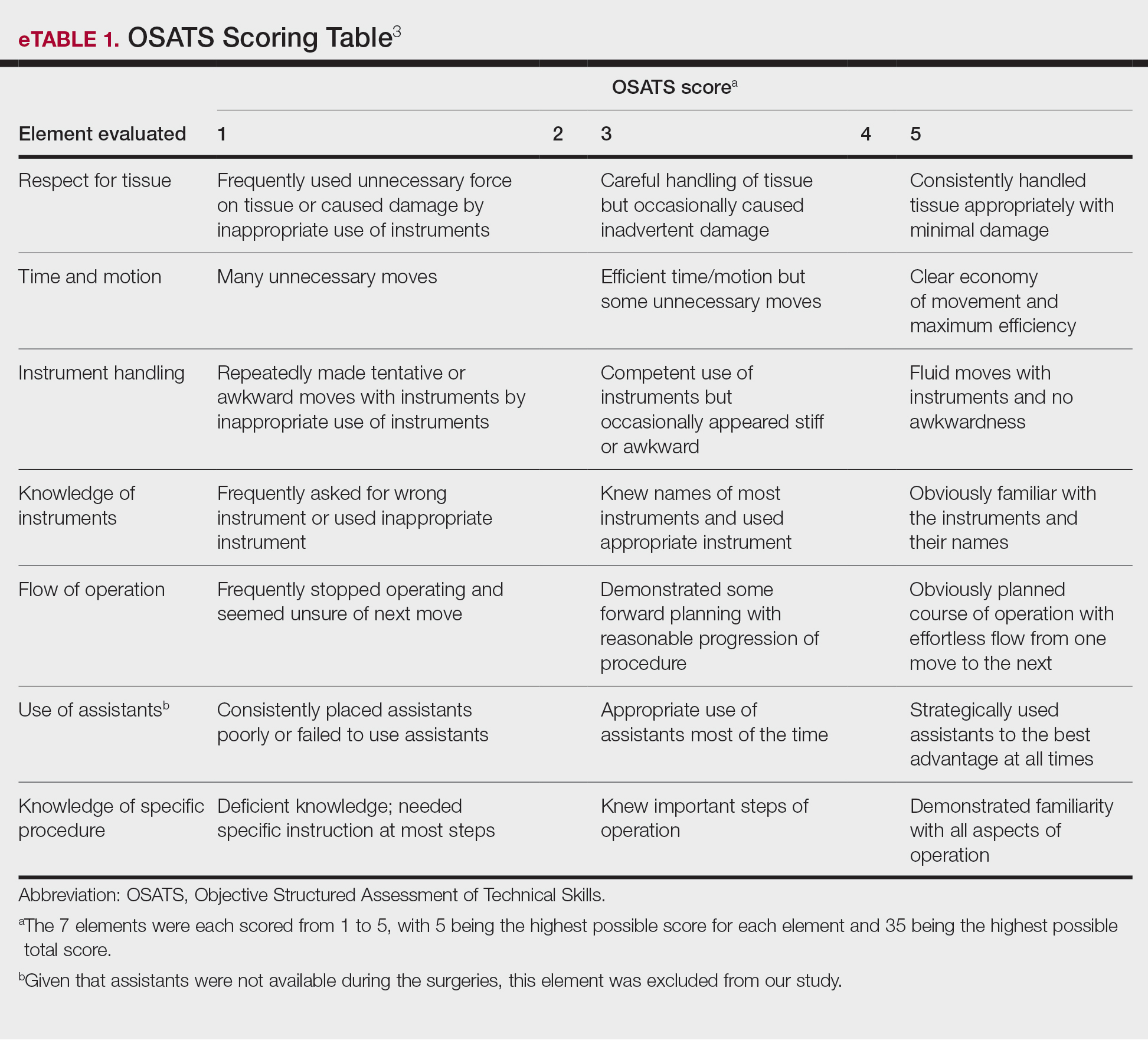

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

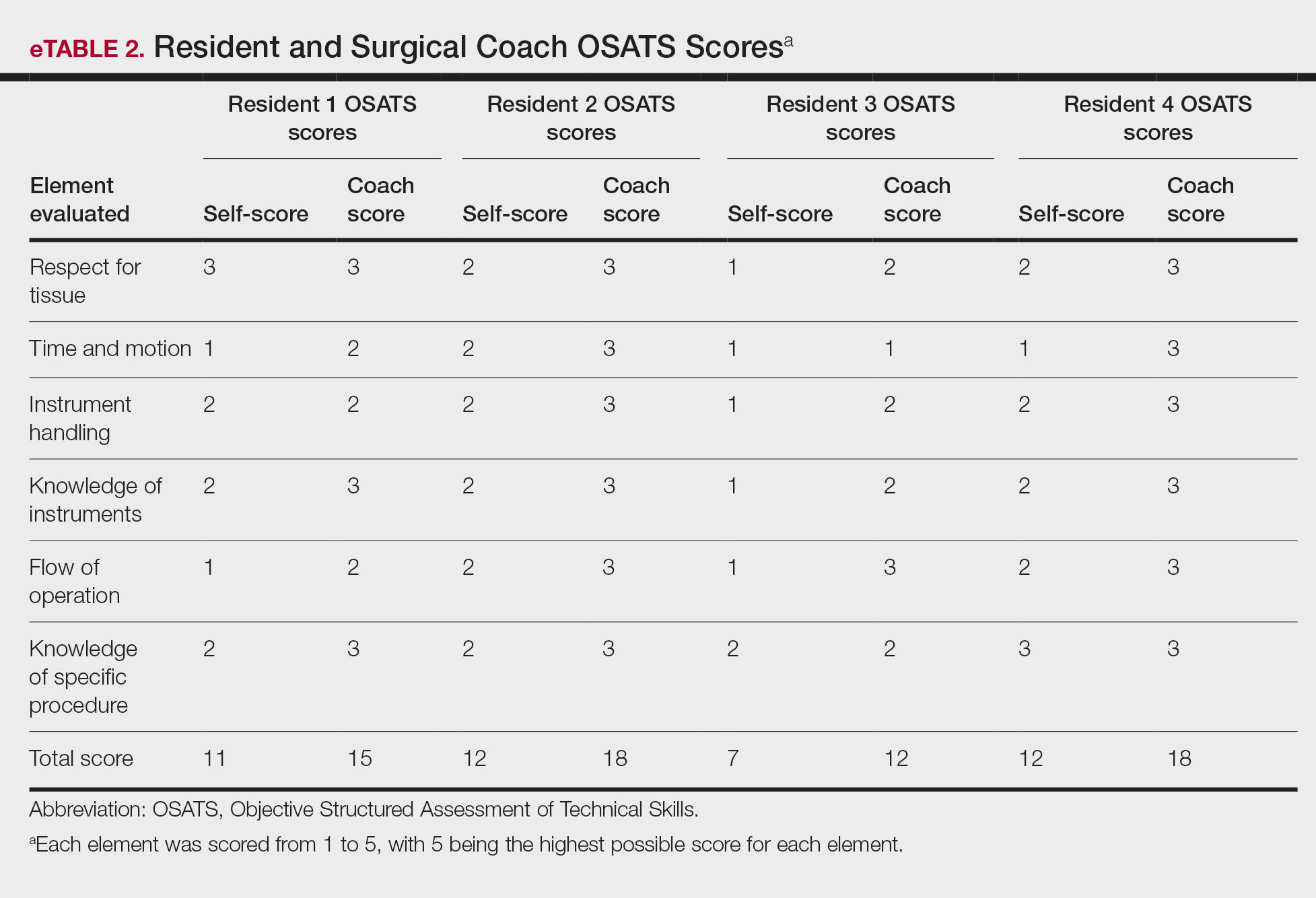

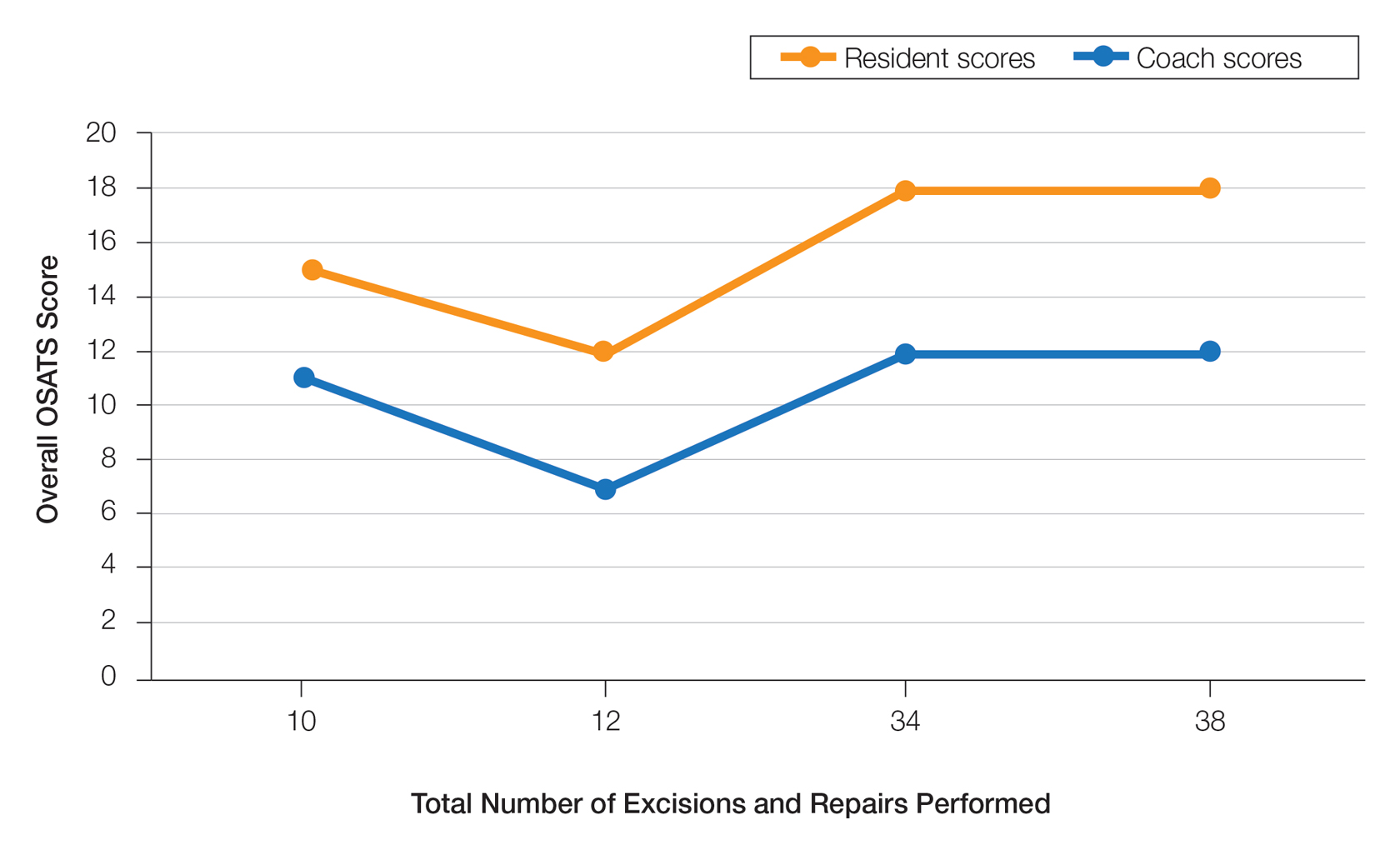

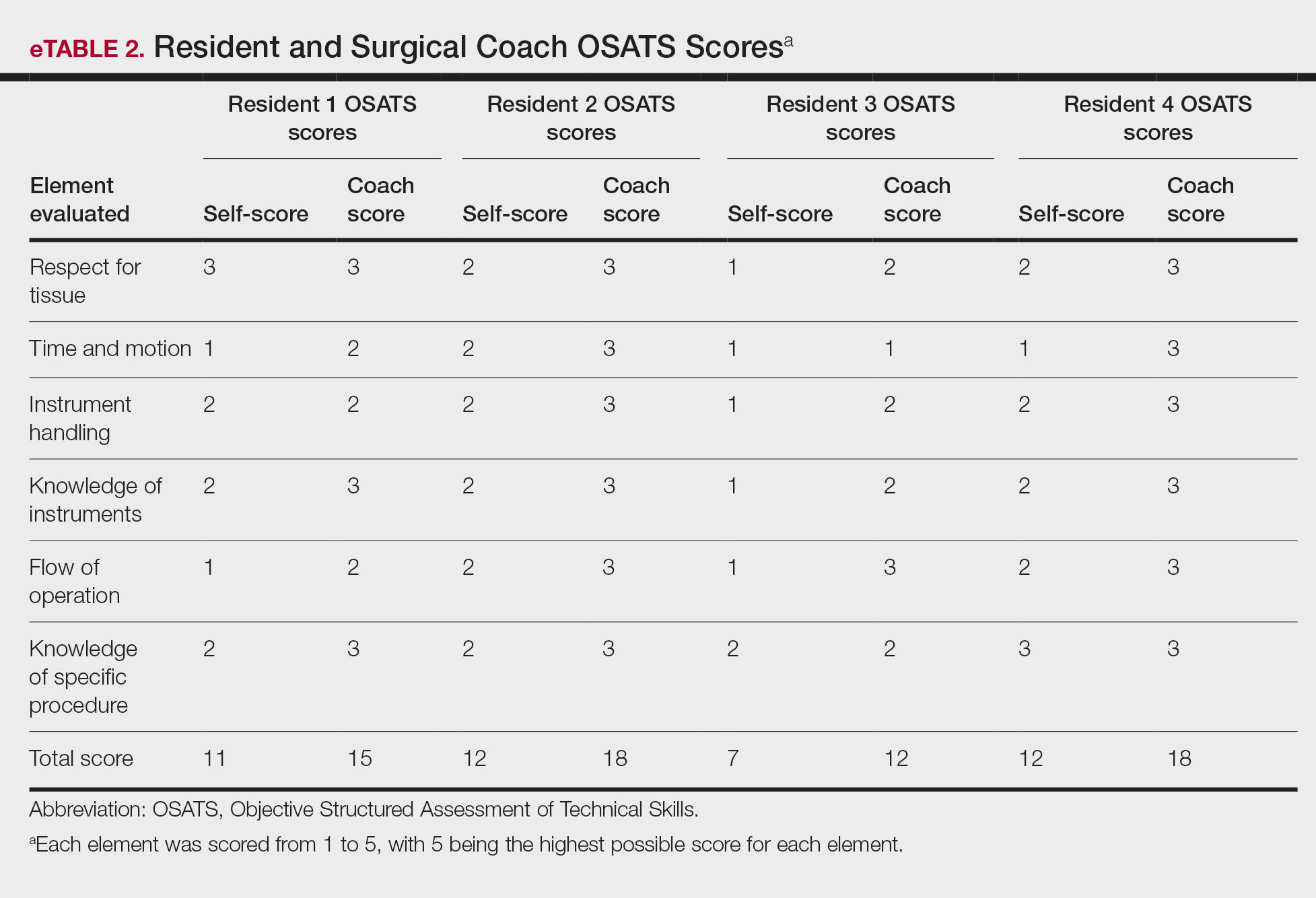

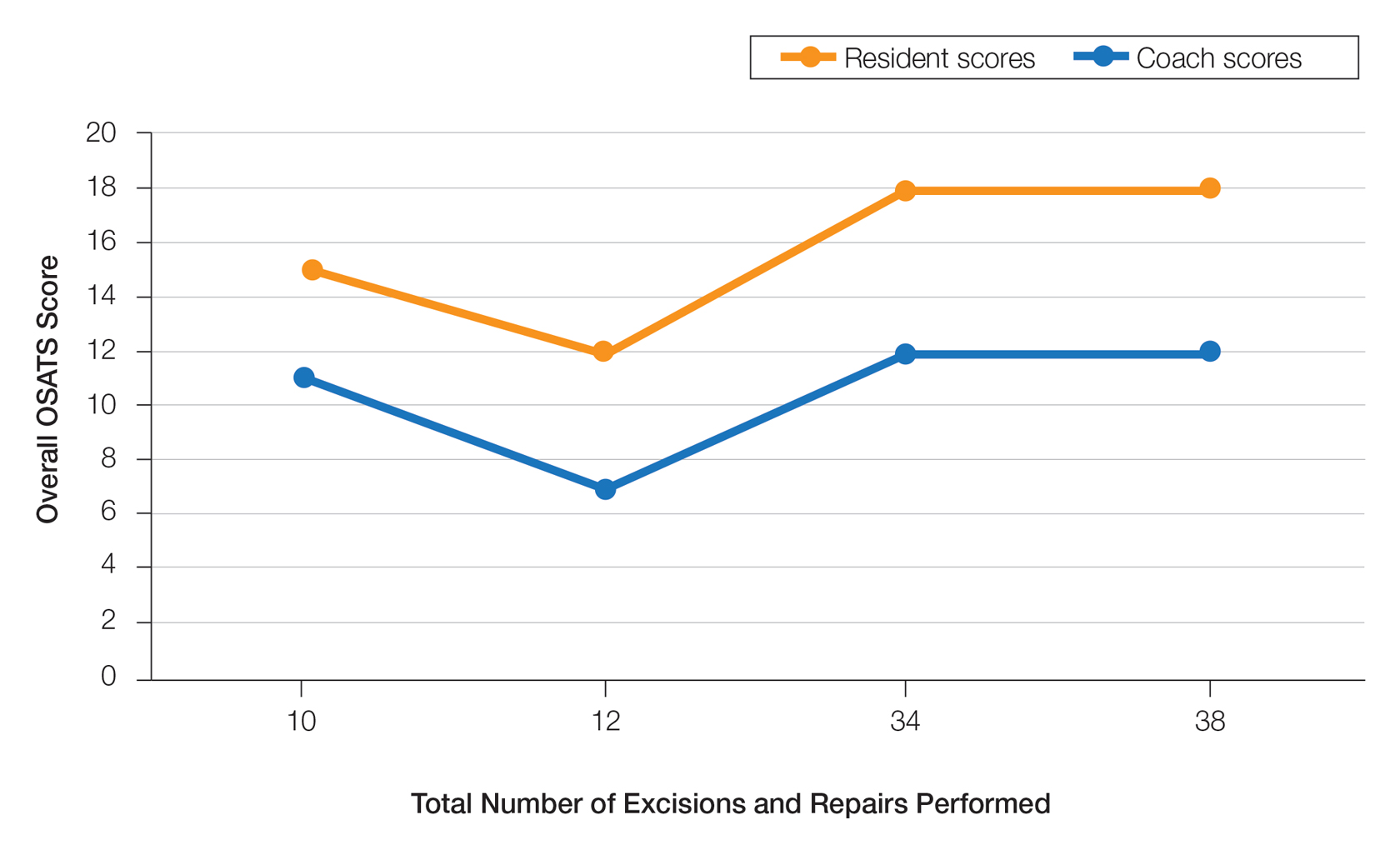

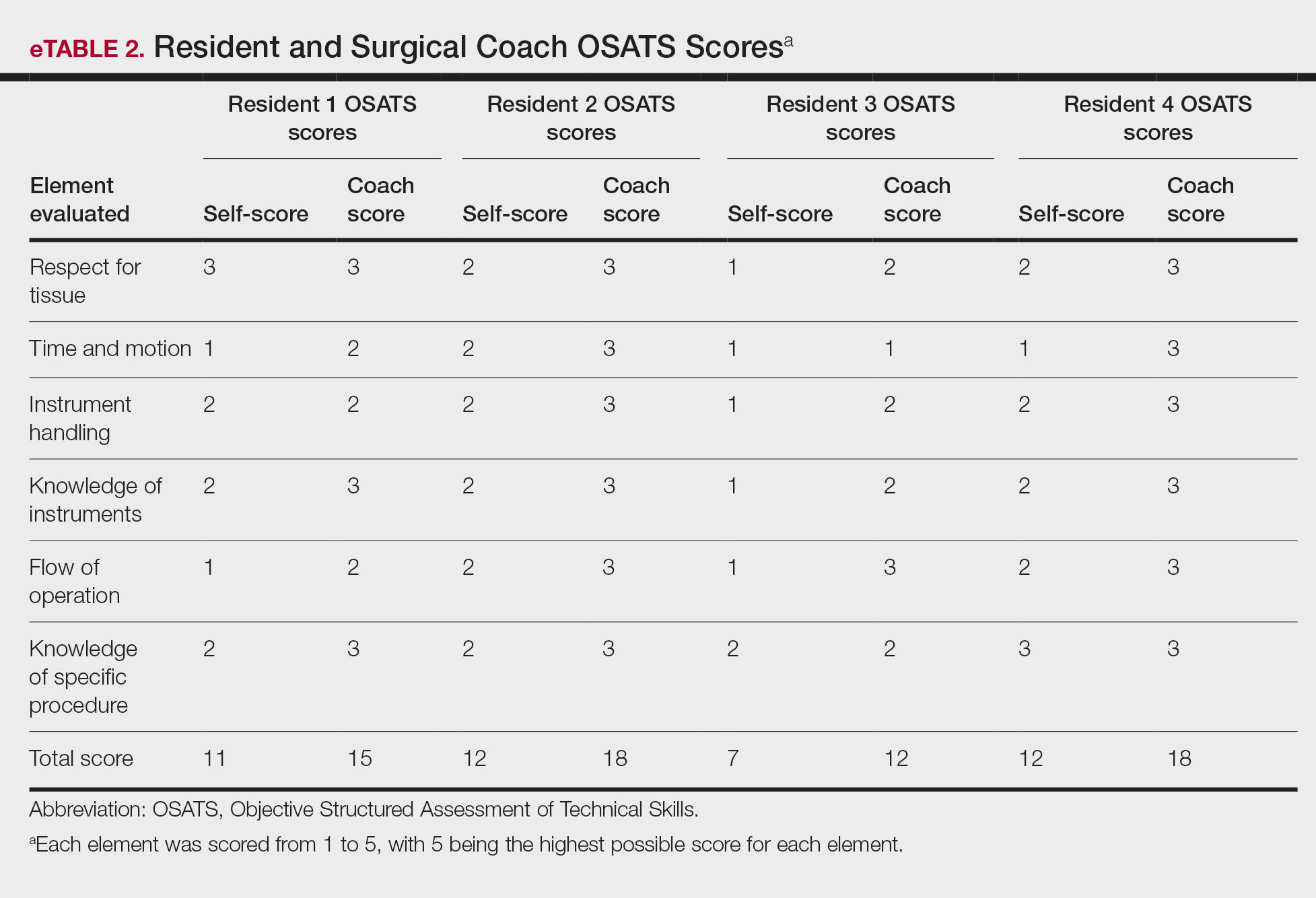

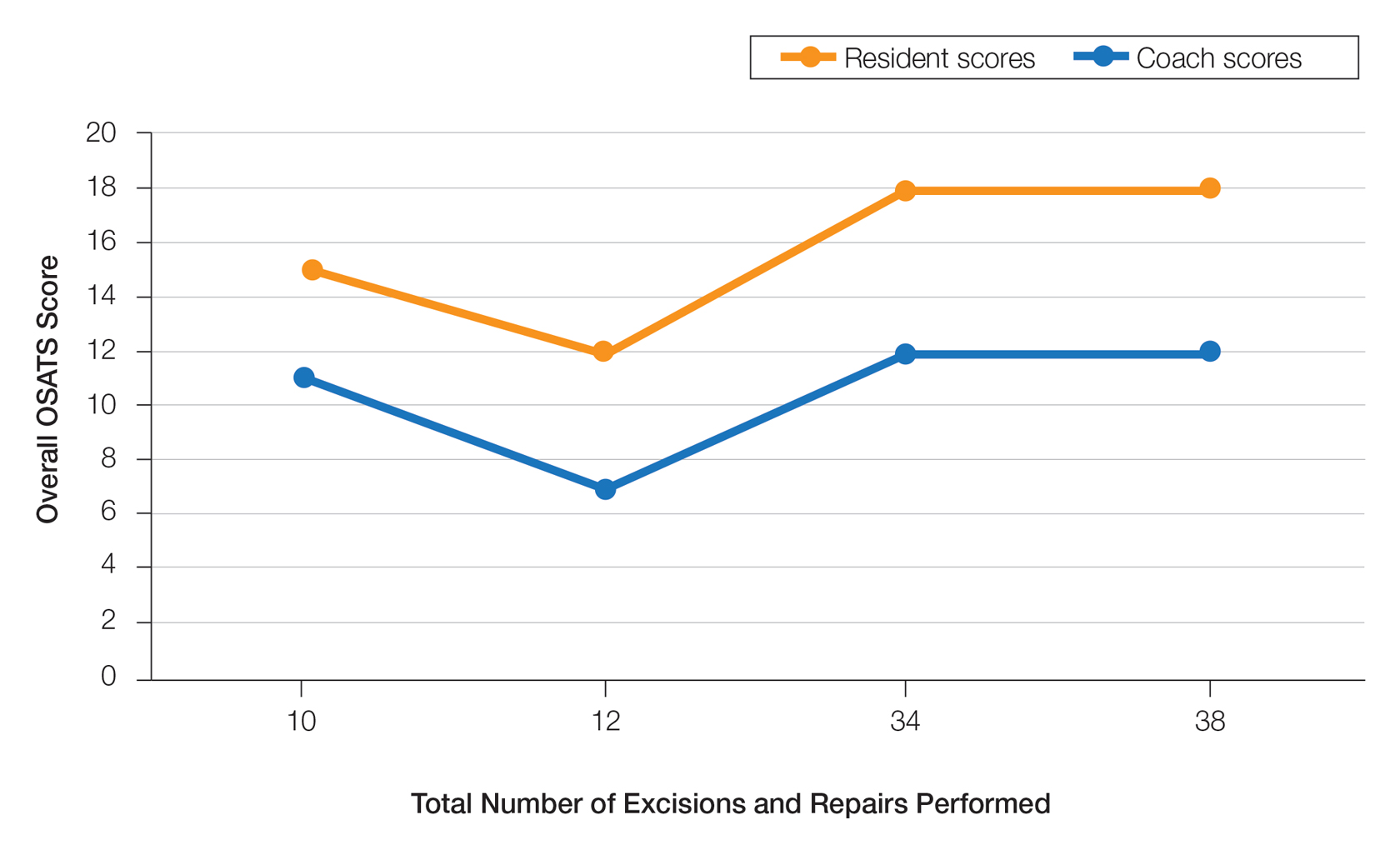

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

To the Editor:

Video-based coaching (VBC) involves a surgeon recording a surgery and then reviewing the video with a surgical coach; it is a form of education that is gaining popularity among surgical specialties.1 Video-based education is underutilized in dermatology residency training.2 We conducted a pilot study at our dermatology residency program to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of VBC.

The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School institutional review board approved this study. All 4 first-year dermatology residents were recruited to participate in this study. Participants filled out a prestudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Participants used a head-mounted point-of-view camera to record themselves performing a wide local excision on the trunk or extremities of a live human patient. Participants then reviewed the recording on their own and scored themselves using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) scoring table (scored from 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest possible score for each element), which is a validated tool for assessing surgical skills (eTable 1).3 Given that there were no assistants participating in the surgery, this element of the OSATS scoring table was excluded, making a maximum possible score of 30 and a minimum possible score of 6. After scoring themselves, participants then had a 1-on-1 coaching session with a fellowship-trained dermatologic surgeon (M.F. or T.H.) via online teleconferencing.

During the coaching session, participants and coaches reviewed the video. The surgical coaches also scored the residents using the OSATS, then residents and coaches discussed how the resident could improve using the OSATS scores as a guide. The residents then completed a poststudy survey assessing their surgical experience, confidence in performing surgery, and attitudes on VBC. Descriptive statistics were reported.

On average, residents spent 31.3 minutes reviewing their own surgeries and scoring themselves. The average time for a coaching session, which included time spent scoring, was 13.8 minutes. Residents scored themselves lower than the surgical coaches did by an average of 5.25 points (eTable 2). Residents gave themselves an average total score of 10.5, while their respective surgical coaches gave the residents an average score of 15.75. There was a trend of residents with greater surgical experience having higher OSATS scores (Figure). After the coaching session, 3 of 4 residents reported that they felt more confident in their surgical skills. All residents felt more confident in assessing their surgical skills and felt that VBC was an effective teaching measure. All residents agreed that VBC should be continued as part of their residency training.

Video-based coaching has the potential to provide several benefits for dermatology trainees. Because receiving feedback intraoperatively often can be distracting and incomplete, video review can instead allow the surgeon to focus on performing the surgery and then later focus on learning while reviewing the video.1,4 Feedback also can be more comprehensive and delivered without concern for time constraints or disturbing clinic flow as well as without the additional concern of the patient overhearing comments and feedback.3 Although independent video review in the absence of coaching can lead to improvement in surgical skills, the addition of VBC provides even greater potential educational benefit.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, VBC allowed coaches to provide feedback without additional exposures. We utilized dermatologic surgery faculty as coaches, but this format of training also would apply to general dermatology faculty.

Another goal of VBC is to enhance a trainee’s ability to perform self-directed learning, which requires accurate self-assessment.4 Accurately assessing one’s own strengths empowers a trainee to act with appropriate confidence, while understanding one’s own weaknesses allows a trainee to effectively balance confidence and caution in daily practice.5 Interestingly, in our study all residents scored themselves lower than surgical coaches, but with 1 coaching session, the residents subsequently reported greater surgical confidence.

Time constraints can be a potential barrier to surgical coaching.4 Our study demonstrates that VBC requires minimal time investment. Increasing the speed of video playback allowed for efficient evaluation of resident surgeries without compromising the coach’s ability to provide comprehensive feedback. Our feedback sessions were performed virtually, which allowed for ease of scheduling between trainees and coaches.

Our pilot study demonstrated that VBC is relatively easy to implement in a dermatology residency training setting, leveraging relatively low-cost technologies and allowing for a means of learning that residents felt was effective. Video-based coaching requires minimal time investment from both trainees and coaches and has the potential to enhance surgical confidence. Our current study is limited by its small sample size. Future studies should include follow-up recordings and assess the efficacy of VBC in enhancing surgical skills.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

- Greenberg CC, Dombrowski J, Dimick JB. Video-based surgical coaching: an emerging approach to performance improvement. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:282-283.

- Dai J, Bordeaux JS, Miller CJ, et al. Assessing surgical training and deliberate practice methods in dermatology residency: a survey of dermatology program directors. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:977-984.

- Chitgopeker P, Sidey K, Aronson A, et al. Surgical skills video-based assessment tool for dermatology residents: a prospective pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:614-616.

- Bull NB, Silverman CD, Bonrath EM. Targeted surgical coaching can improve operative self-assessment ability: a single-blinded nonrandomized trial. Surgery. 2020;167:308-313.

- Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 suppl):S46-S54.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Video-based coaching (VBC) for surgical procedures is an up-and-coming form of medical education that allows a “coach” to provide thoughtful and in-depth feedback while reviewing a recording with the surgeon in a private setting. This format has potential utility in teaching dermatology resident surgeons being coached by a dermatology faculty member.

- We performed a pilot study demonstrating that VBC can be performed easily with a minimal time investment for both the surgeon and the coach. Dermatology residents not only felt that VBC was an effective teaching method but also should become a formal part of their education.

Perceived Benefits of a Research Fellowship for Dermatology Residency Applicants: Outcomes of a Faculty-Reported Survey

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

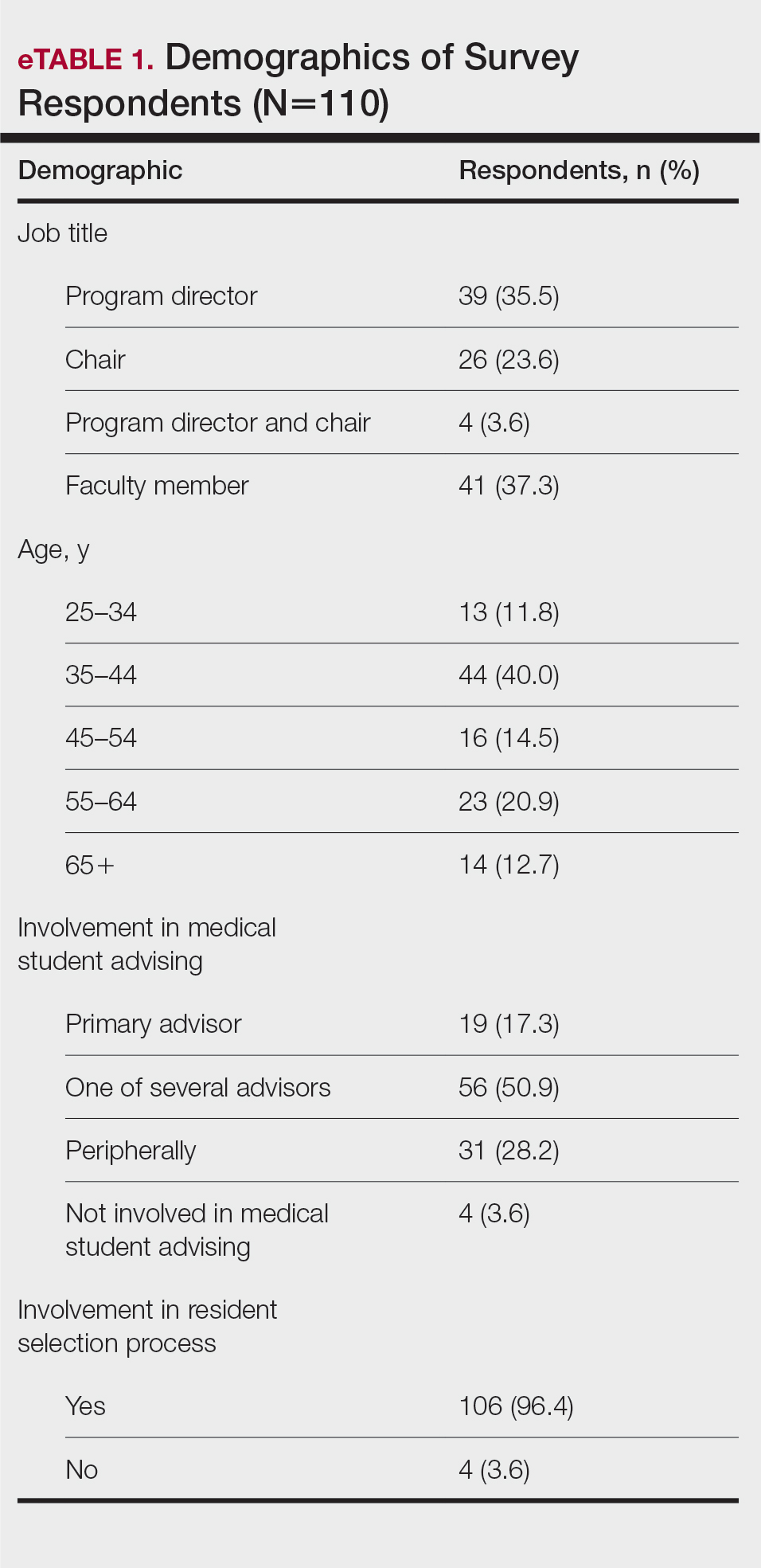

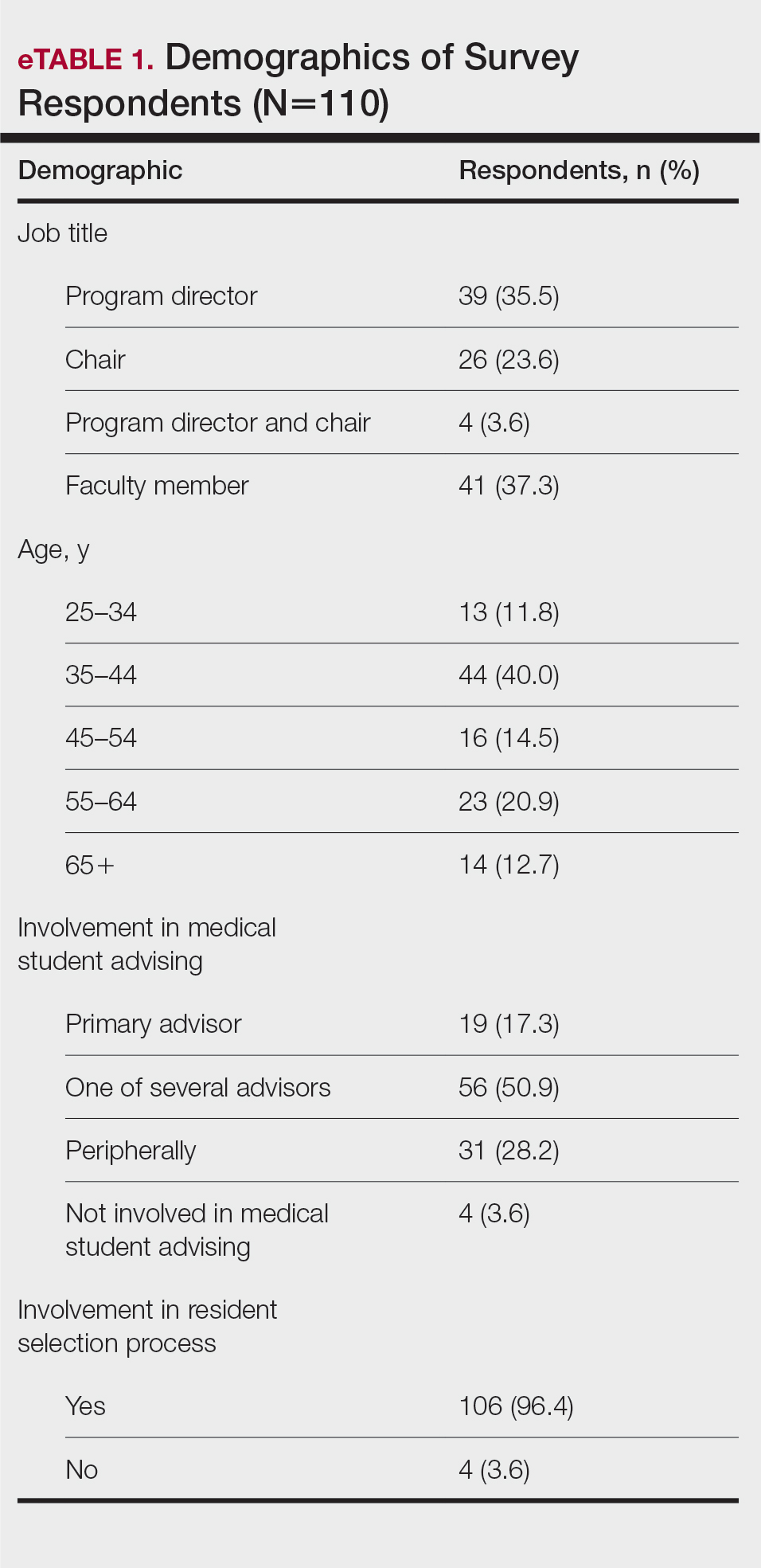

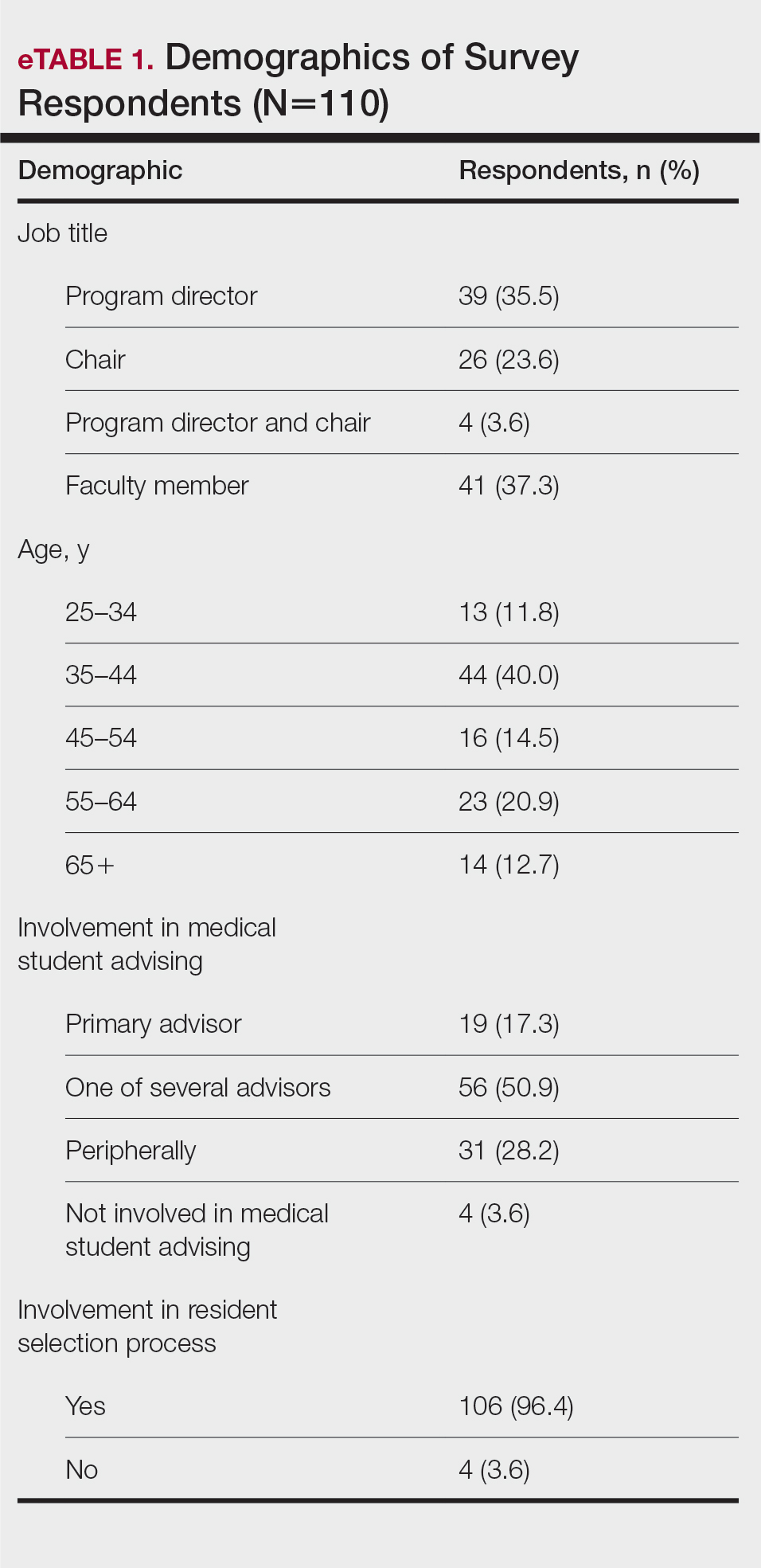

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

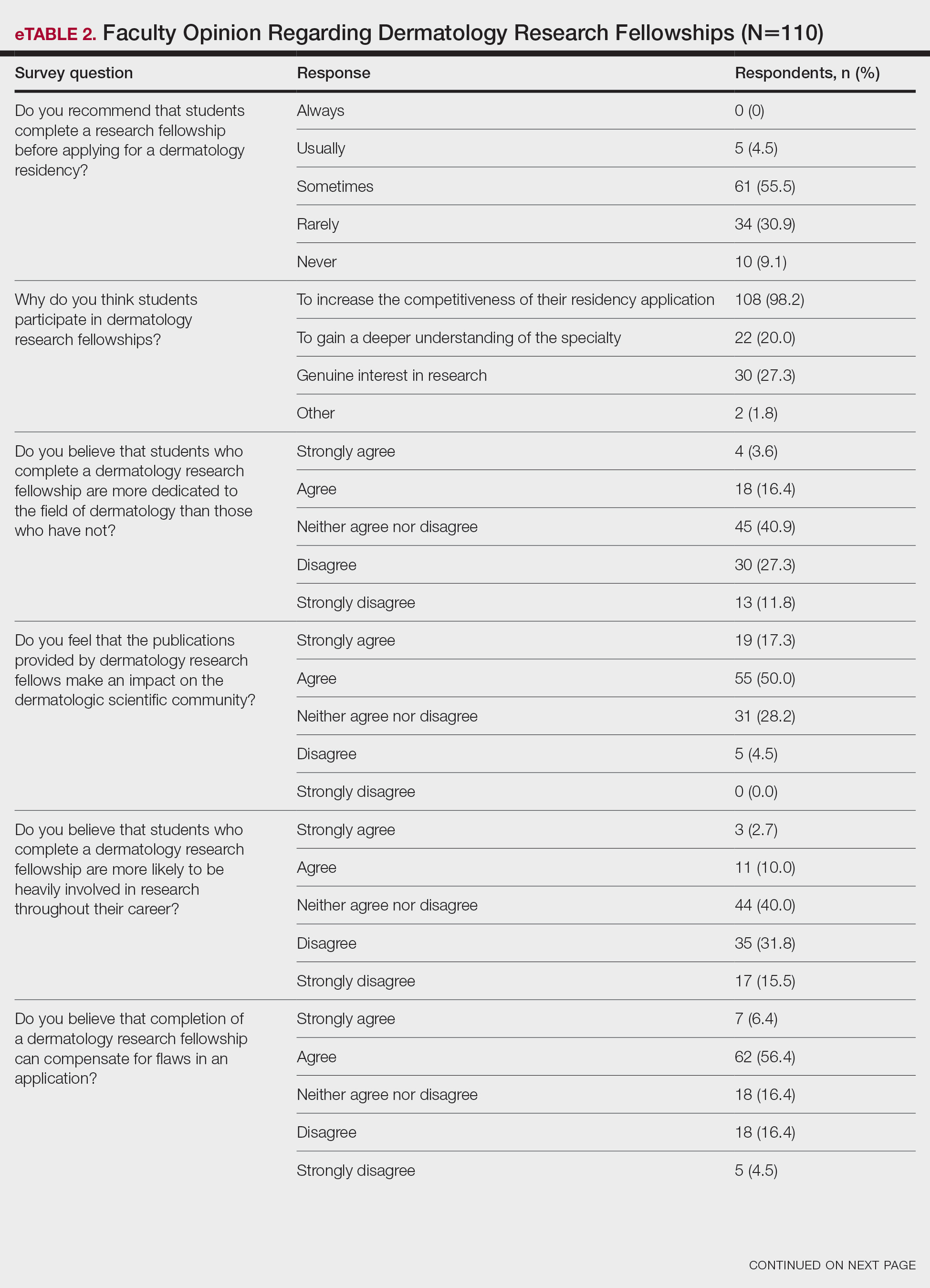

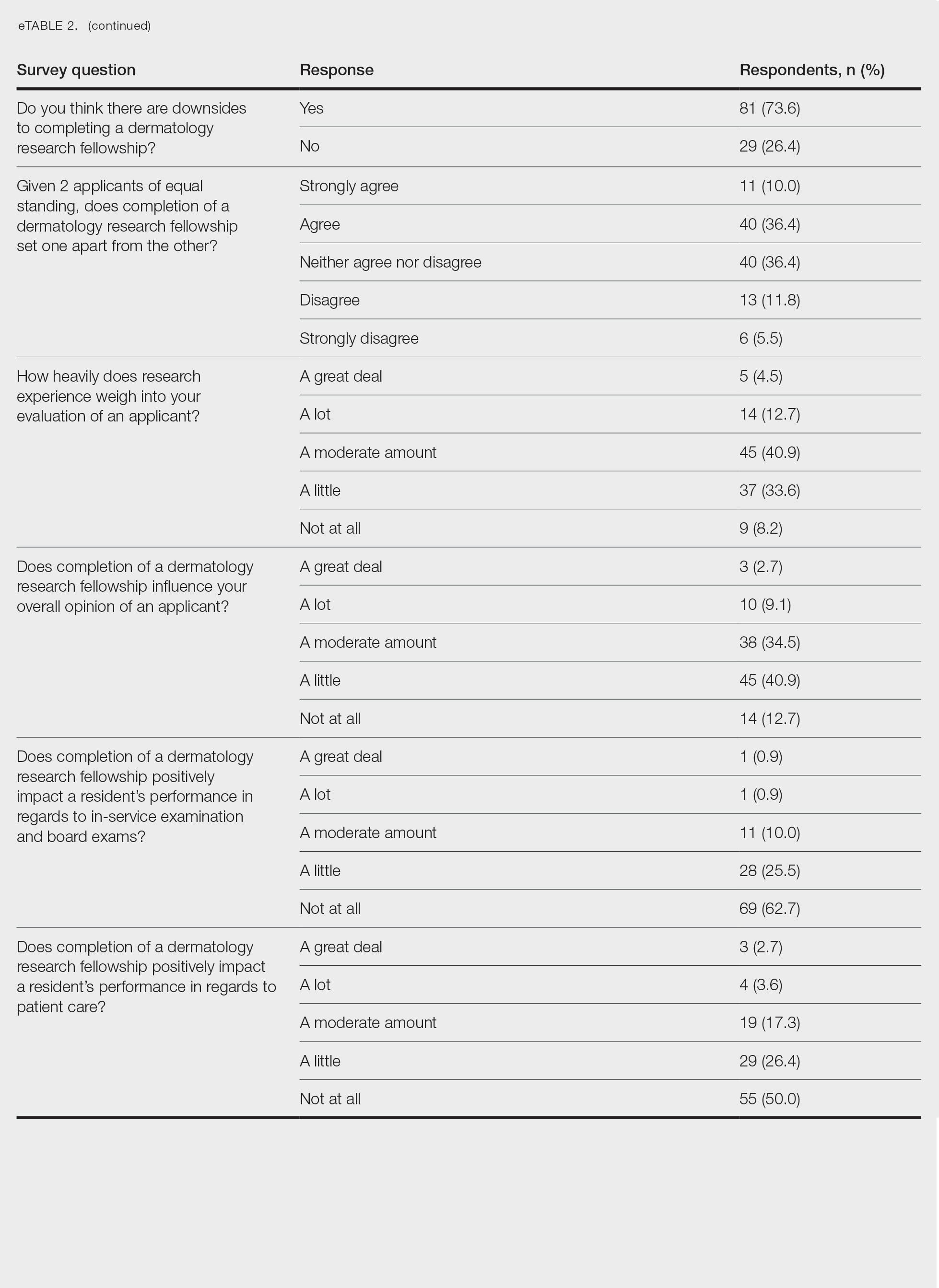

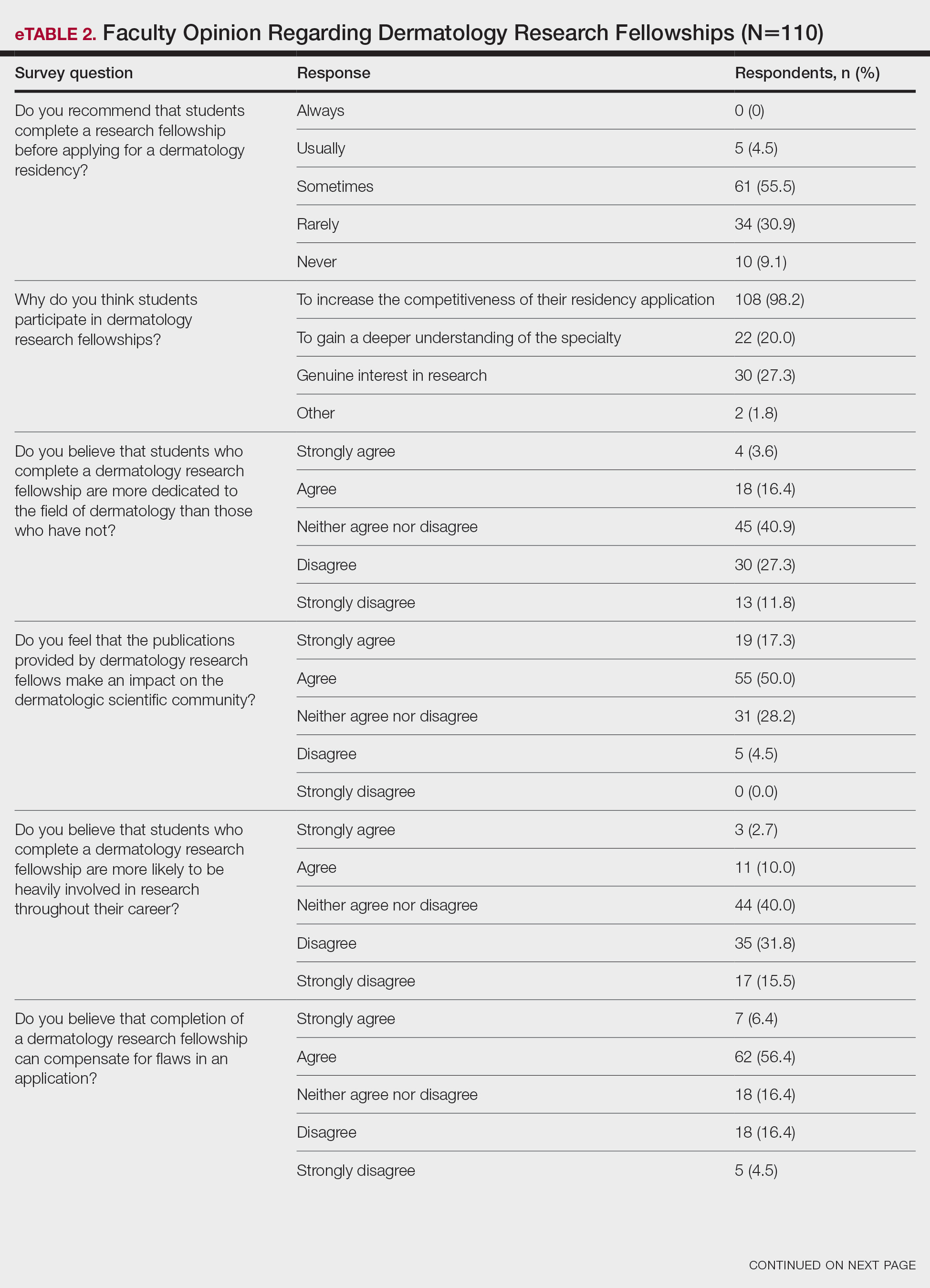

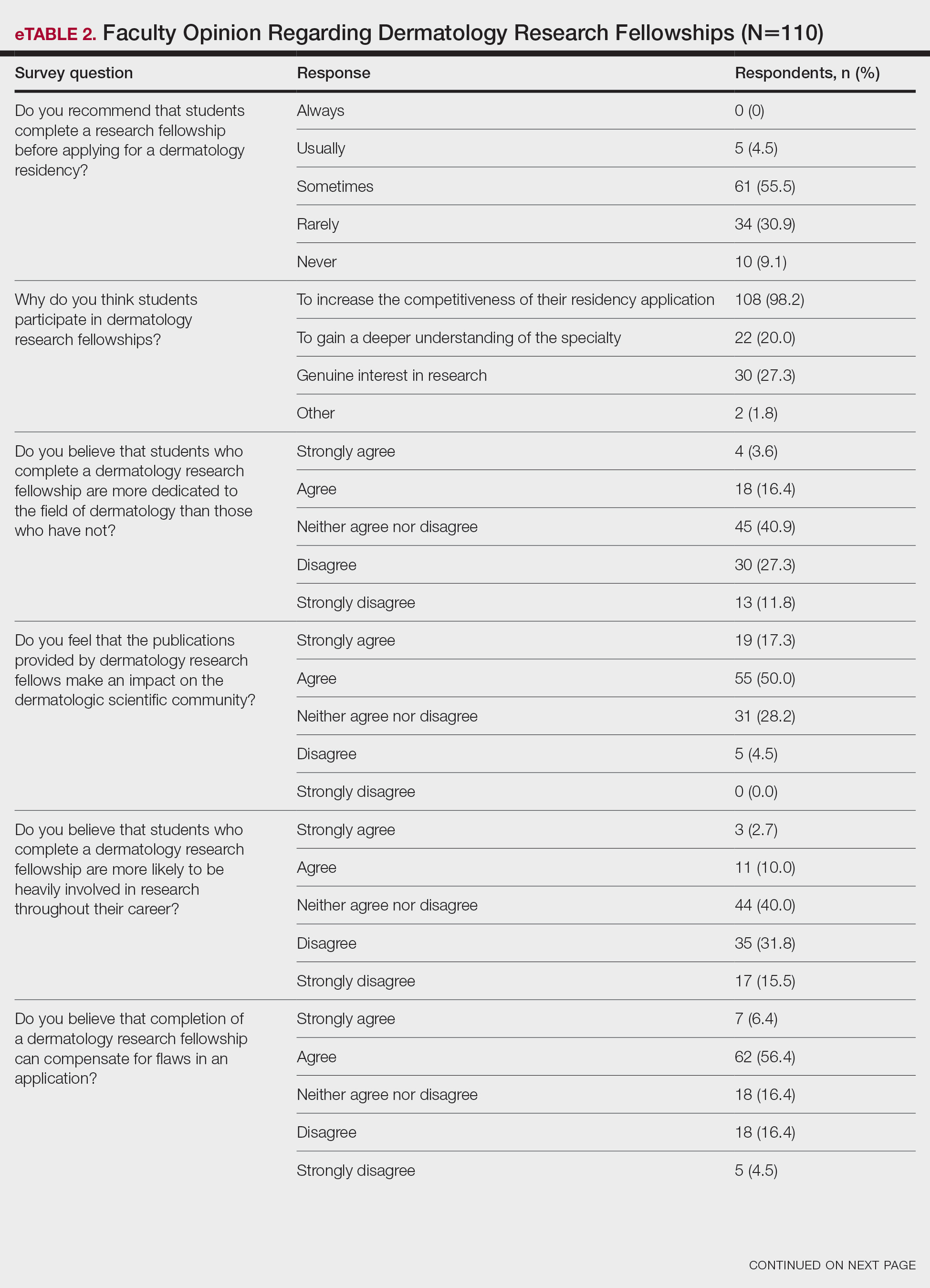

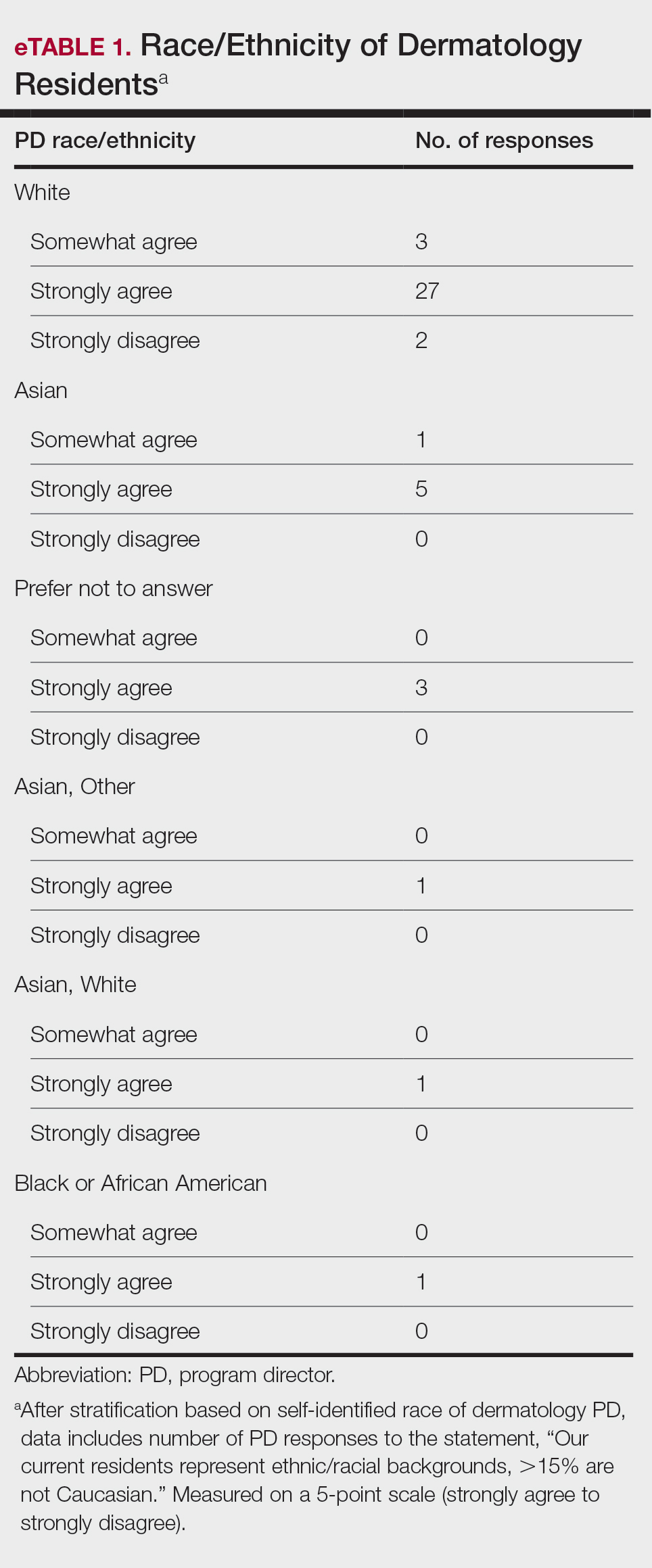

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

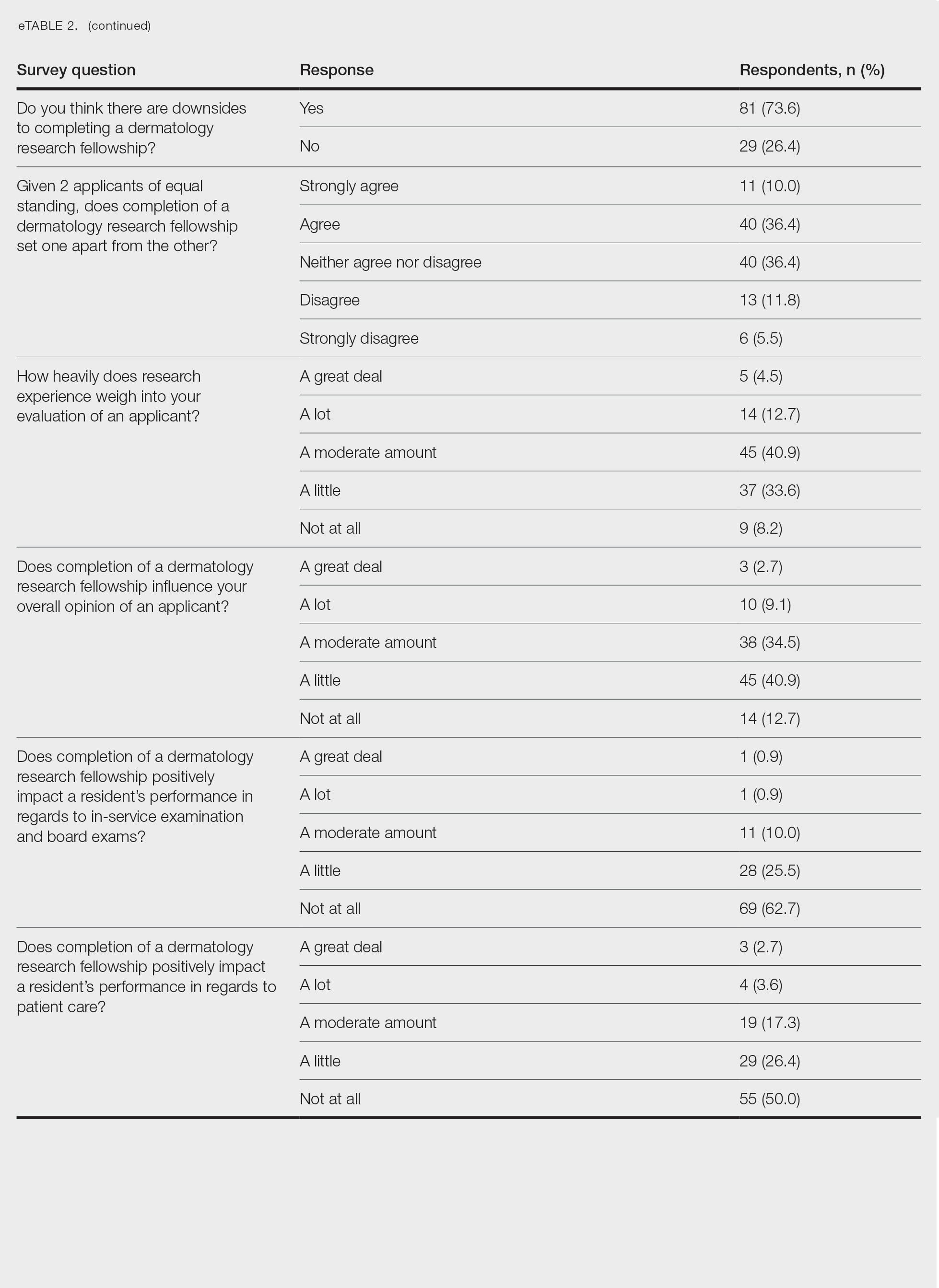

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Many medical students seeking to match into a dermatology residency program complete a research fellowship (RF).

- Completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants even though most advisors acknowledge that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their career, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

- The decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic and should be tailored to each individual applicant.

Results From the First Annual Association of Professors of Dermatology Program Directors Survey

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

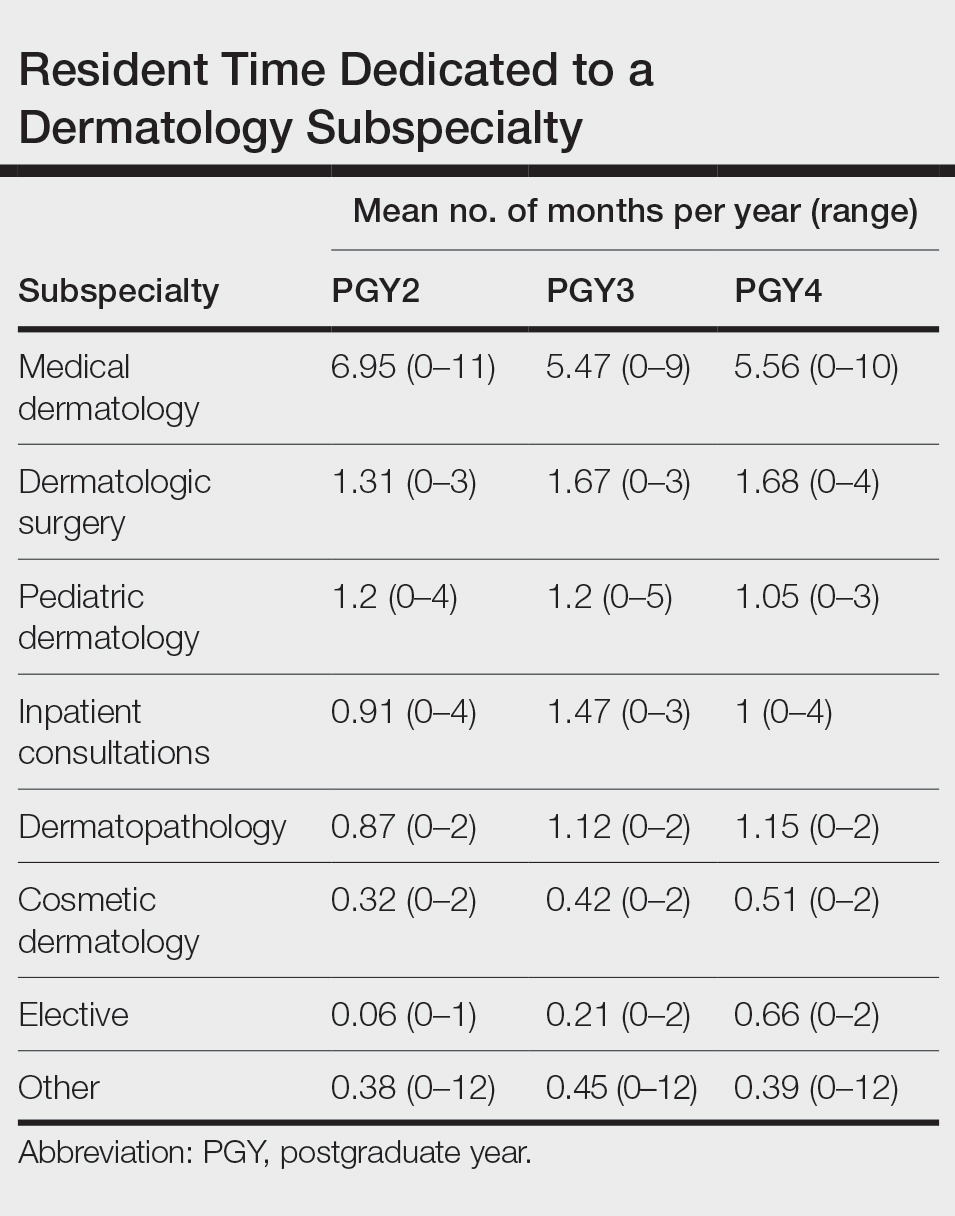

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.

Available Resources—Twenty-four percent (11/46) of respondents indicated that residents in their program do not get protected time or time off for CORE examinations. Seventy-five percent (33/44) of PDs said their program provides funding for residents to participate in board review courses. The chief residents at 63% (31/49) of programs receive additional compensation, and 69% (34/49) provide additional administrative time to chief residents. Seventy-one percent (24/34) of PDs reported their programs have scribes for attendings, and 12% (4/34) have scribes for residents. Support staff help residents with callbacks and in-basket messages according to 76% (35/46) of respondents. The majority (98% [45/46]) of PDs indicated that residents follow-up on results and messages from patients seen in resident clinics, and 43% (20/46) of programs have residents follow-up with patients seen in faculty clinics. Only 15% (7/46) of PDs responded they have schedules with residents dedicated to handle these tasks. According to respondents, 33% (17/52) have residents who are required to travel more than 25 miles to distant clinical sites. Of them, 35% (6/17) provide accommodations.

Quality Improvement—Seventy-one percent (35/49) of respondents indicated their department has a quality improvement/patient safety team or committee, and 94% (33/35) of these teams include residents. A lecture series on quality improvement and patient safety is offered at 67% (33/49) of the respondents’ programs, while morbidity and mortality conferences are offered in 73% (36/49).

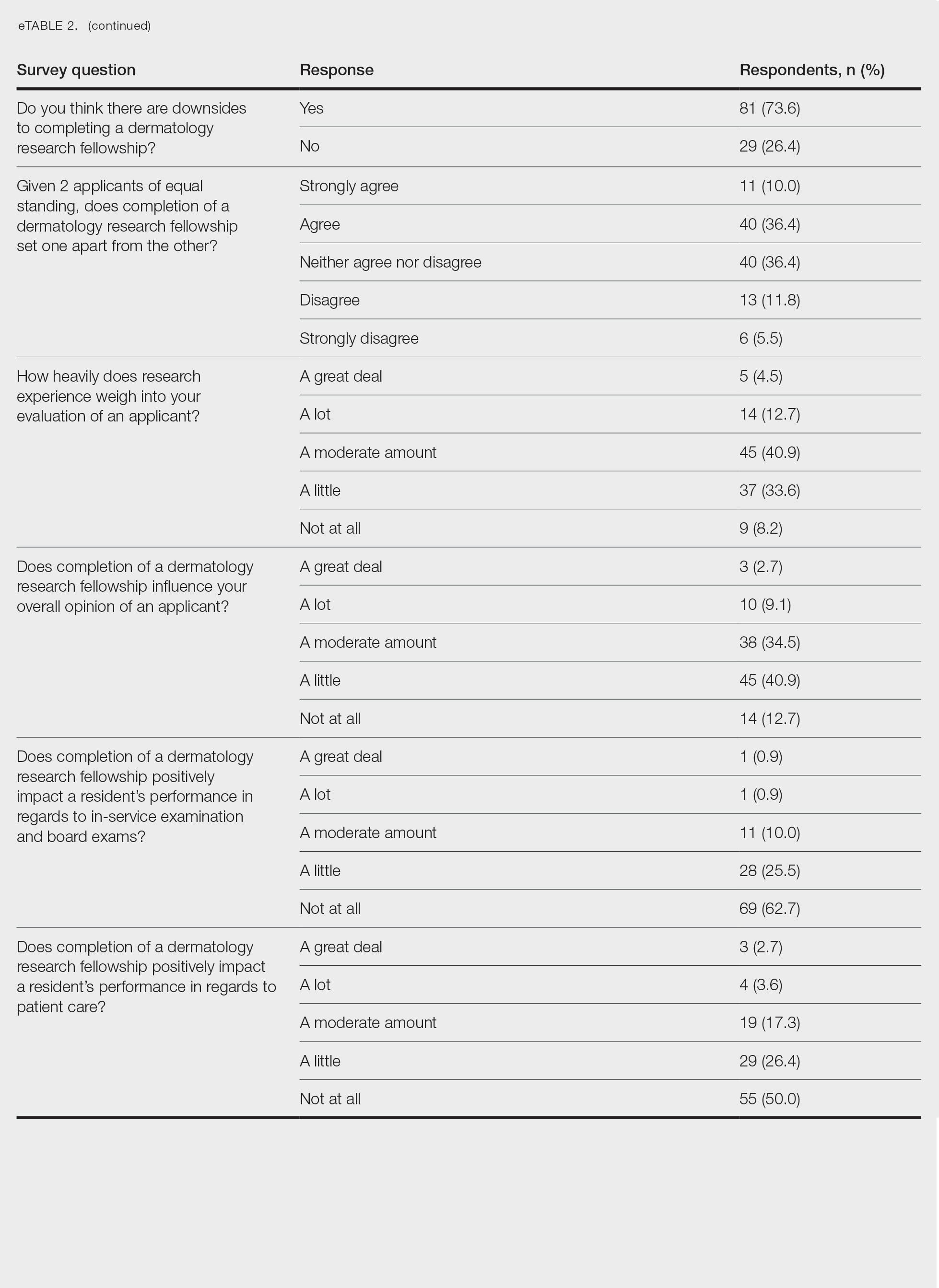

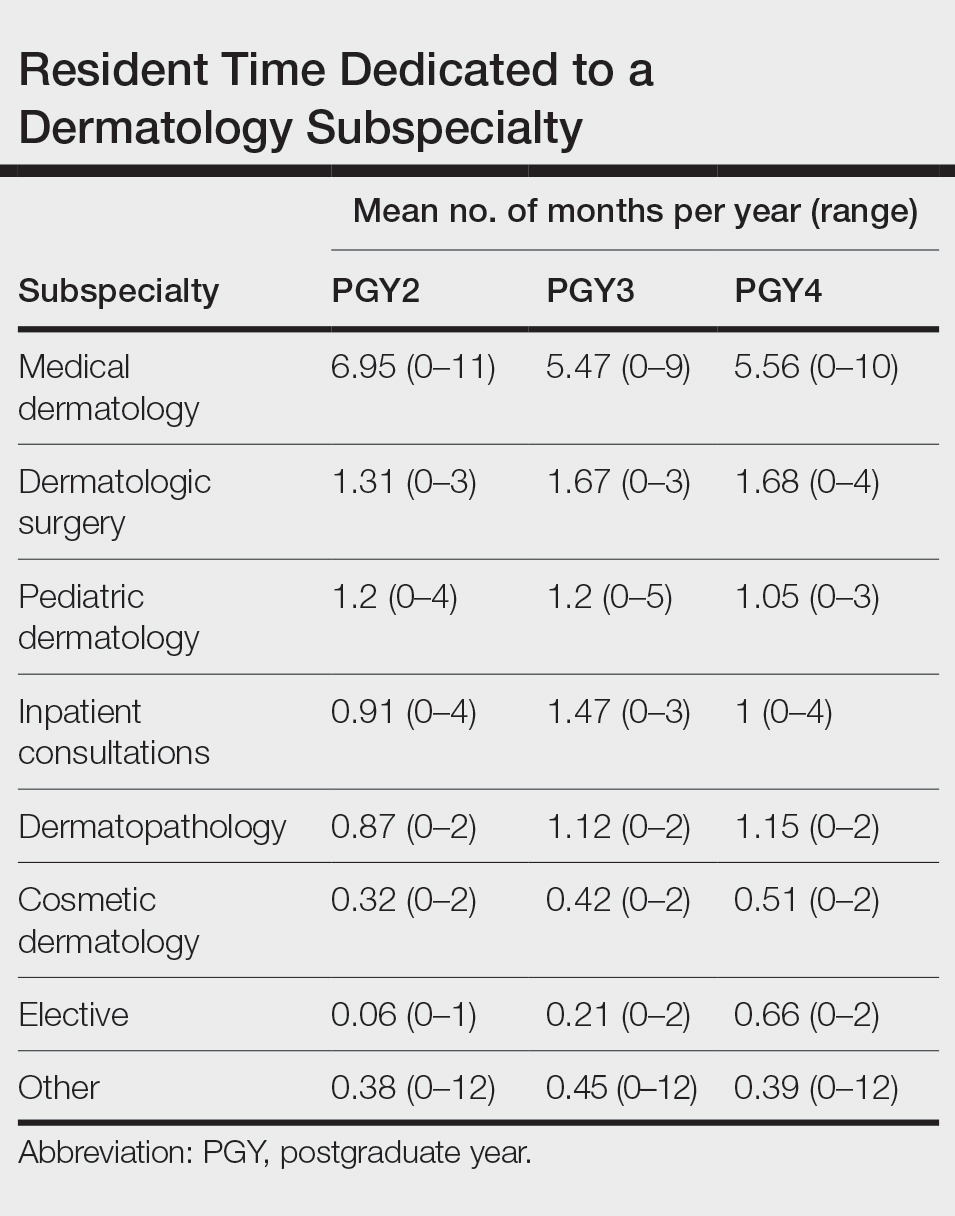

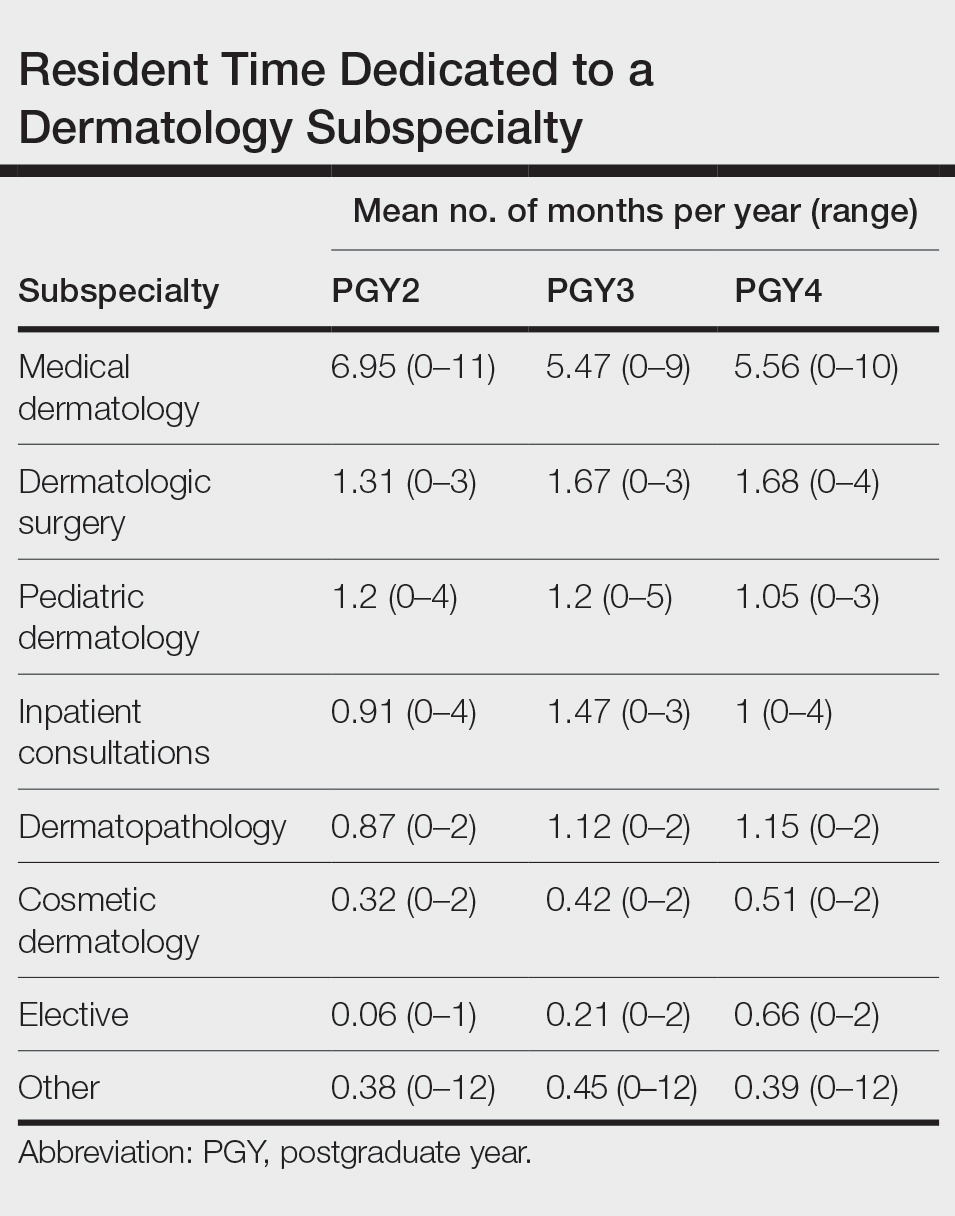

Clinical Instruction—Our survey asked PDs how many months each residency year spends on a certain rotational service. Based on 46 respondents, the average number of months dedicated to medical dermatology is 7, 5, and 6 months for postgraduate year (PGY) 2, PGY3, and PGY4, respectively. The average number of months spent in other subspecialties is provided in the Table. On average, PGY2 residents spend 8 half-days per week seeing patients in clinic, while PGY3 and PGY4 residents see patients for 7 half-days. The median and mean number of patients staffed by a single attending per hour in teaching clinics are 6 and 5.88, respectively. Respondents indicated that residents participate in the following specialty clinics: pediatric dermatology (96% [44/46]), laser/cosmetic (87% [40/44]), high-risk skin cancer (ie, immunosuppressed/transplant patient)(65% [30/44]), pigmented lesion/melanoma (52% [24/44]), connective tissue disease (52% [24/44]), teledermatology (50% [23/44]), free clinic for homeless and/or indigent populations (48% [22/44]), contact dermatitis (43% [20/44]), skin of color (43% [20/44]), oncodermatology (41% [19/44]), and bullous disease (33% [15/44]).

Additionally, in 87% (40/46) of programs, residents participate in a dedicated inpatient consultation service. Most respondents (98% [45/46]) responded that they utilize in-person consultations with a teledermatology supplement. Fifteen percent (7/46) utilize virtual teledermatology (live video-based consultations), and 57% (26/46) utilize asynchronous teledermatology (picture-based consultations). All respondents (n=46) indicated that 0% to 25% of patient encounters involving residents are teledermatology visits. Thirty-three percent (6/18) of programs have a global health special training track, 56% (10/18) have a Specialty Training and Advanced Research/Physician-Scientist Research Training track, 28% (5/18) have a diversity training track, and 50% (9/18) have a clinician educator training track.

Didactic Instruction—Five programs have a full day per week dedicated to didactics, while 36 programs have at least one half-day per week for didactics. On average, didactics in 57% (26/46) of programs are led by faculty alone, while 43% (20/46) are led at least in part by residents or fellows.

Research Content—Fifty percent (23/46) of programs have a specific research requirement for residents beyond general ACGME requirements, and 35% (16/46) require residents to participate in a longitudinal research project over the course of residency. There is a dedicated research coordinator for resident support at 63% (29/46) of programs. Dedicated biostatistics research support is available for resident projects at 42% (19/45) of programs. Additionally, at 42% (19/45) of programs, there is a dedicated faculty member for oversight of resident research.

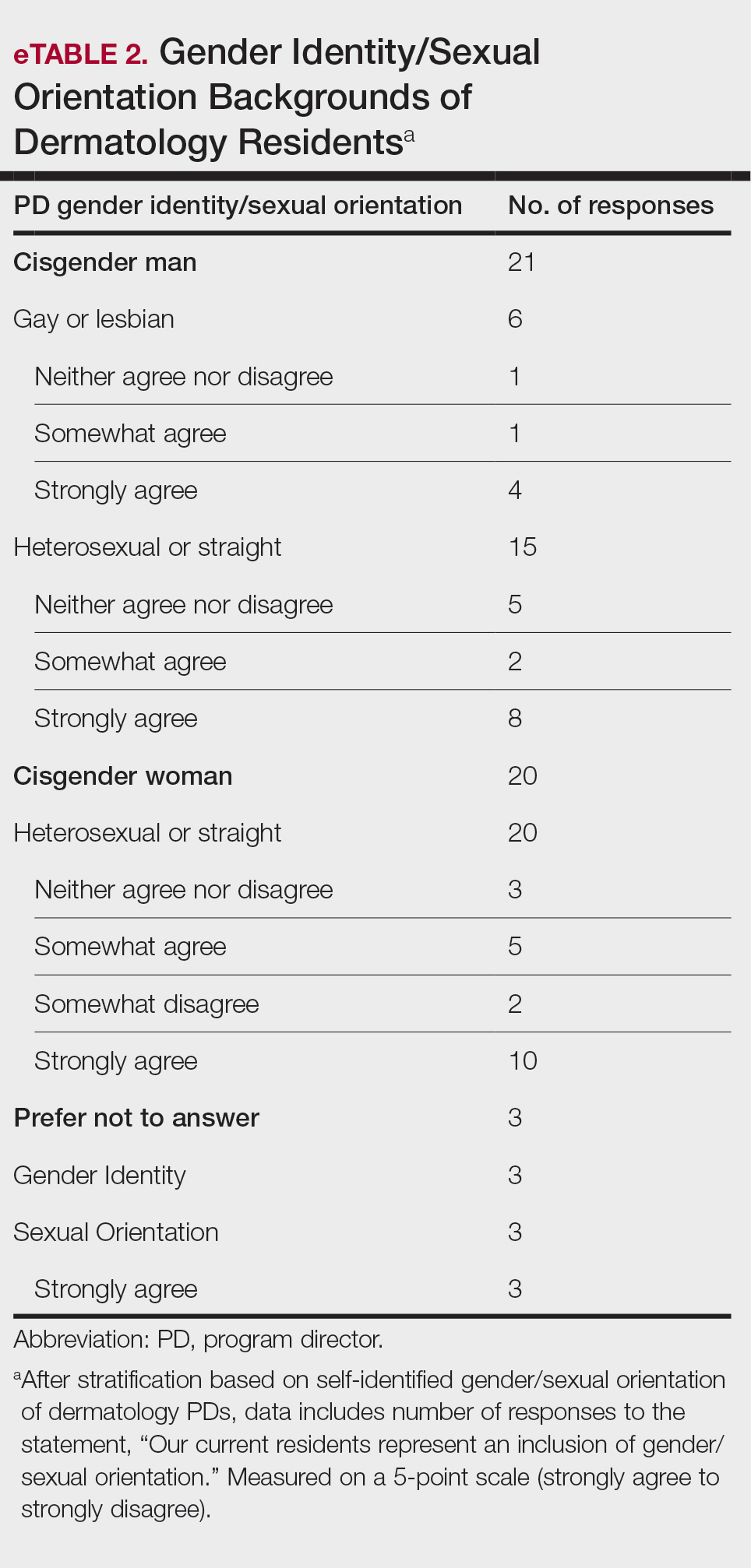

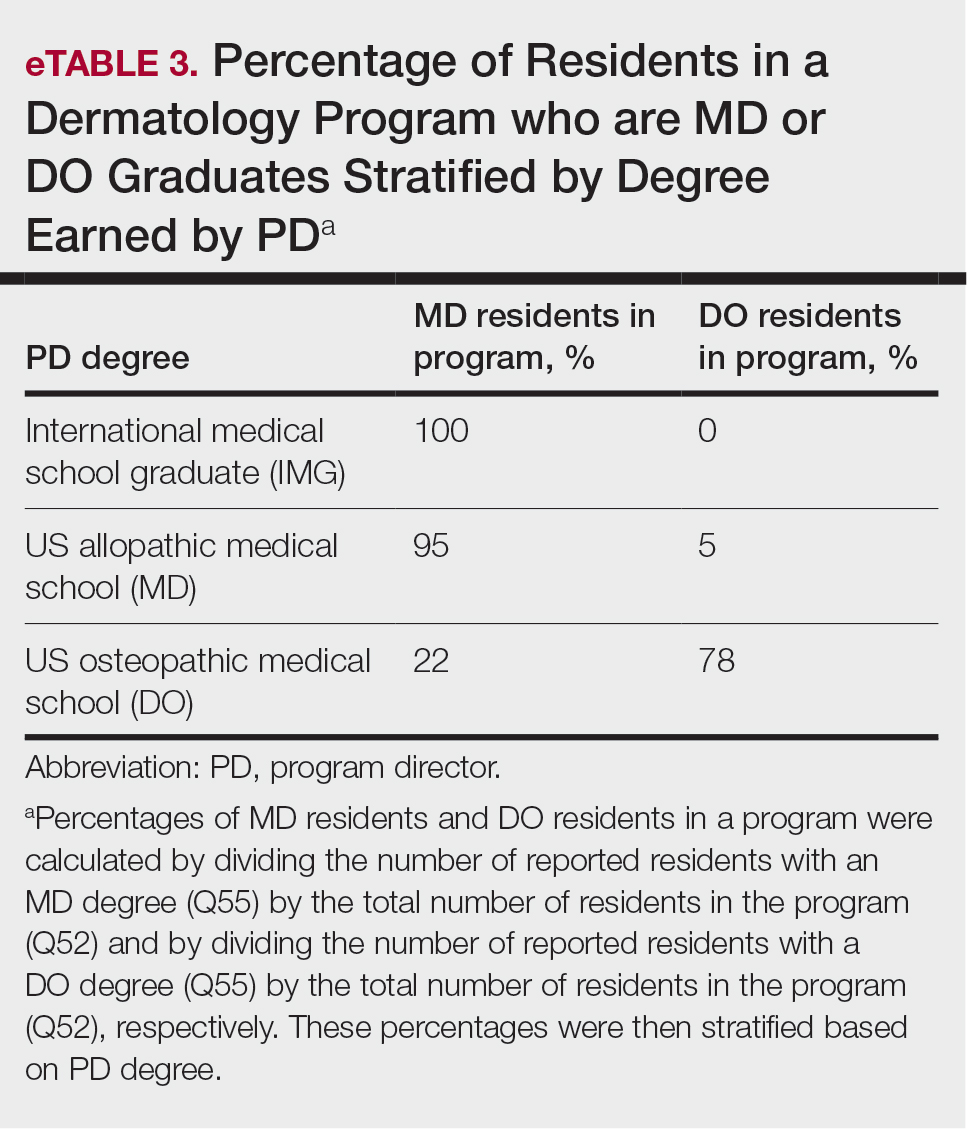

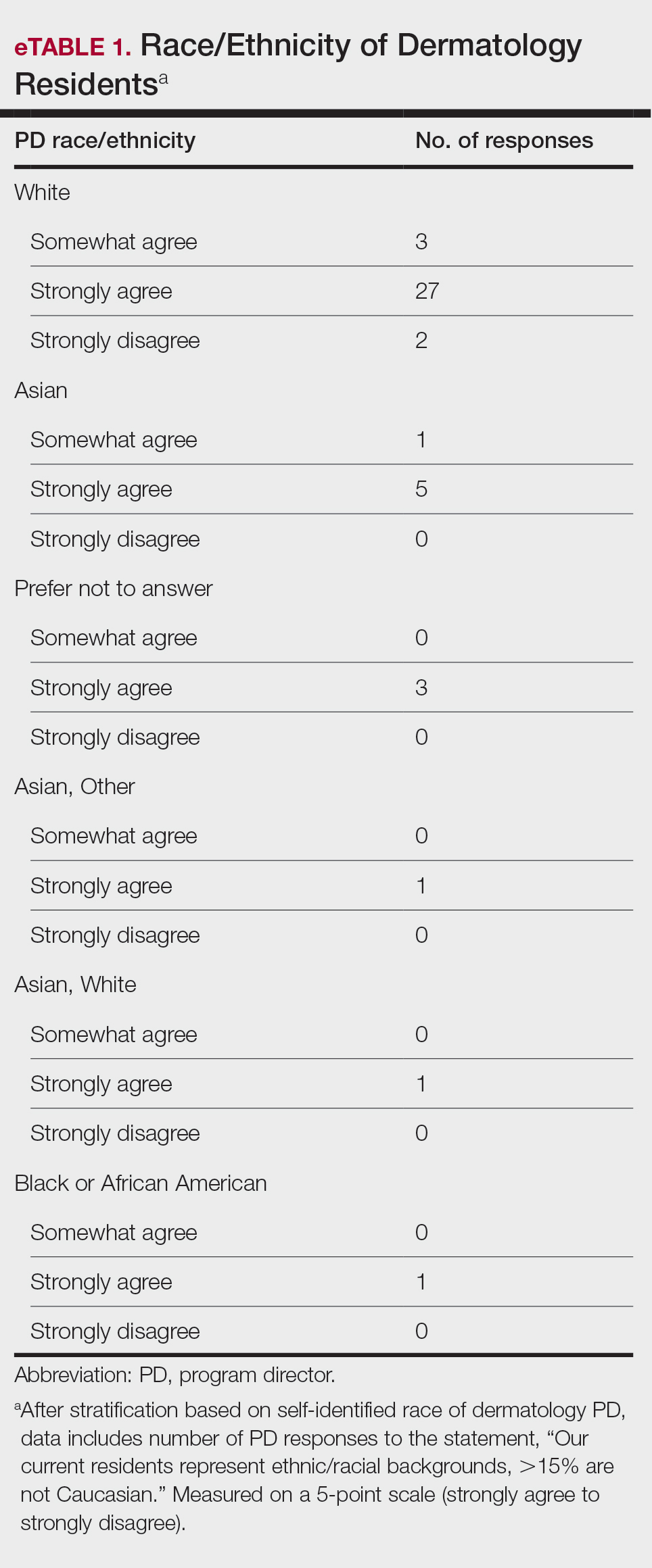

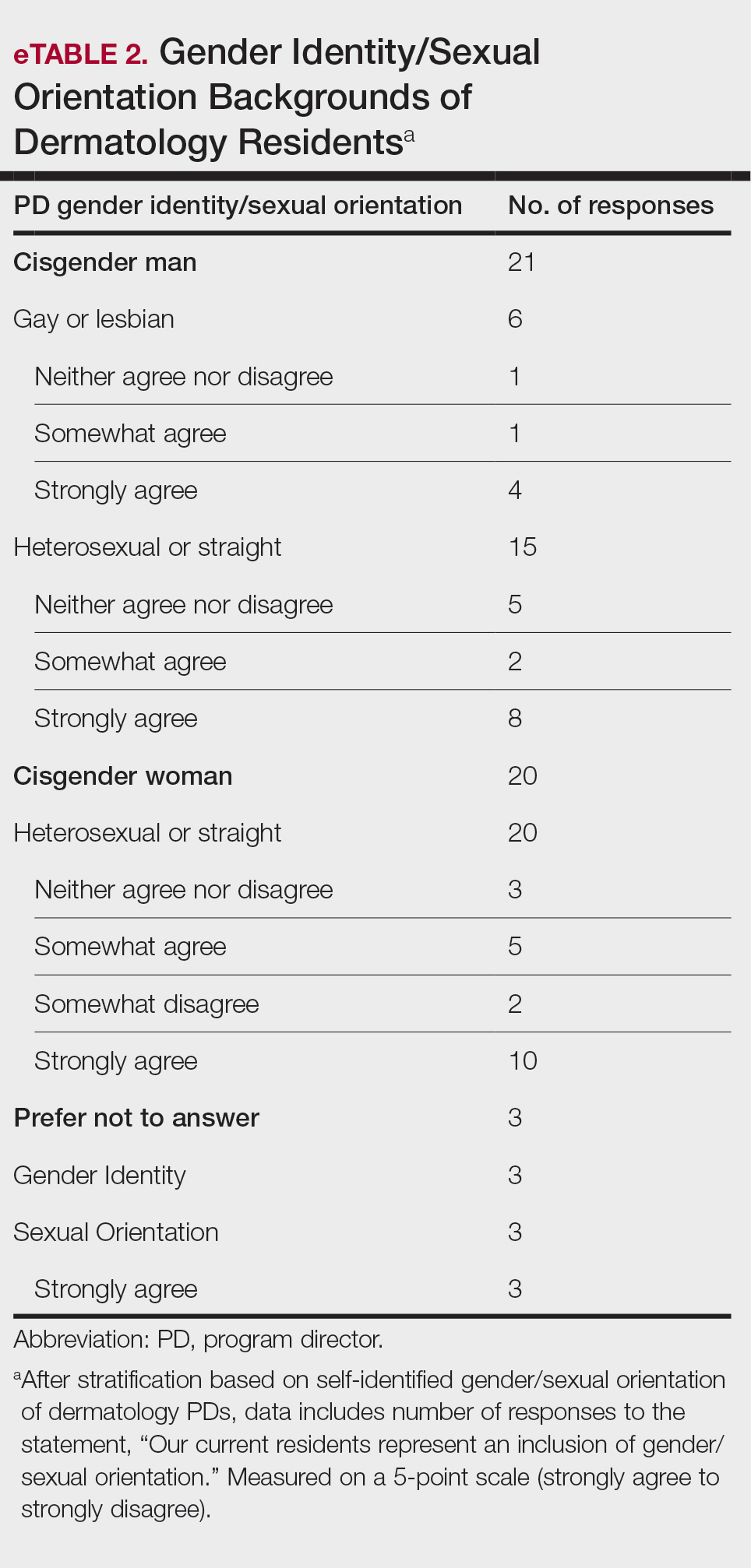

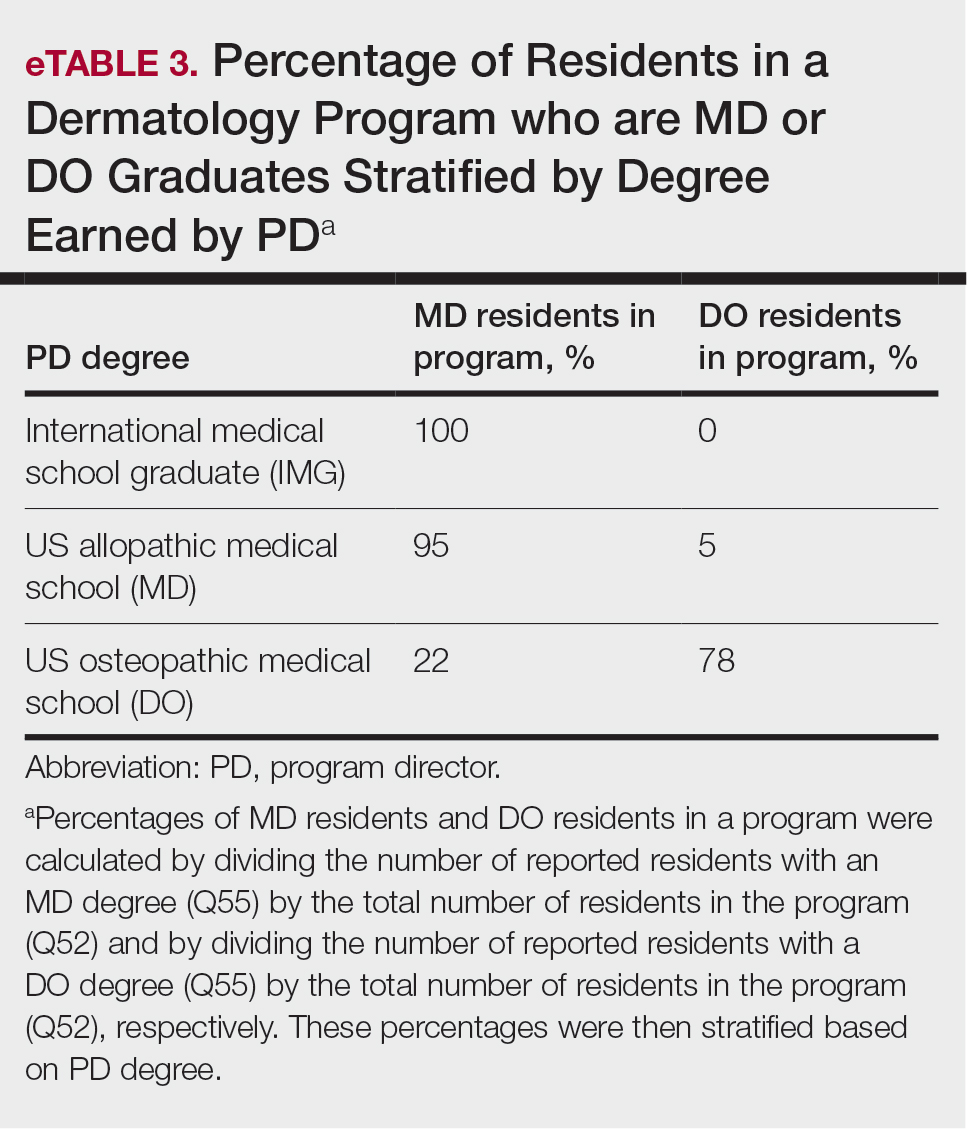

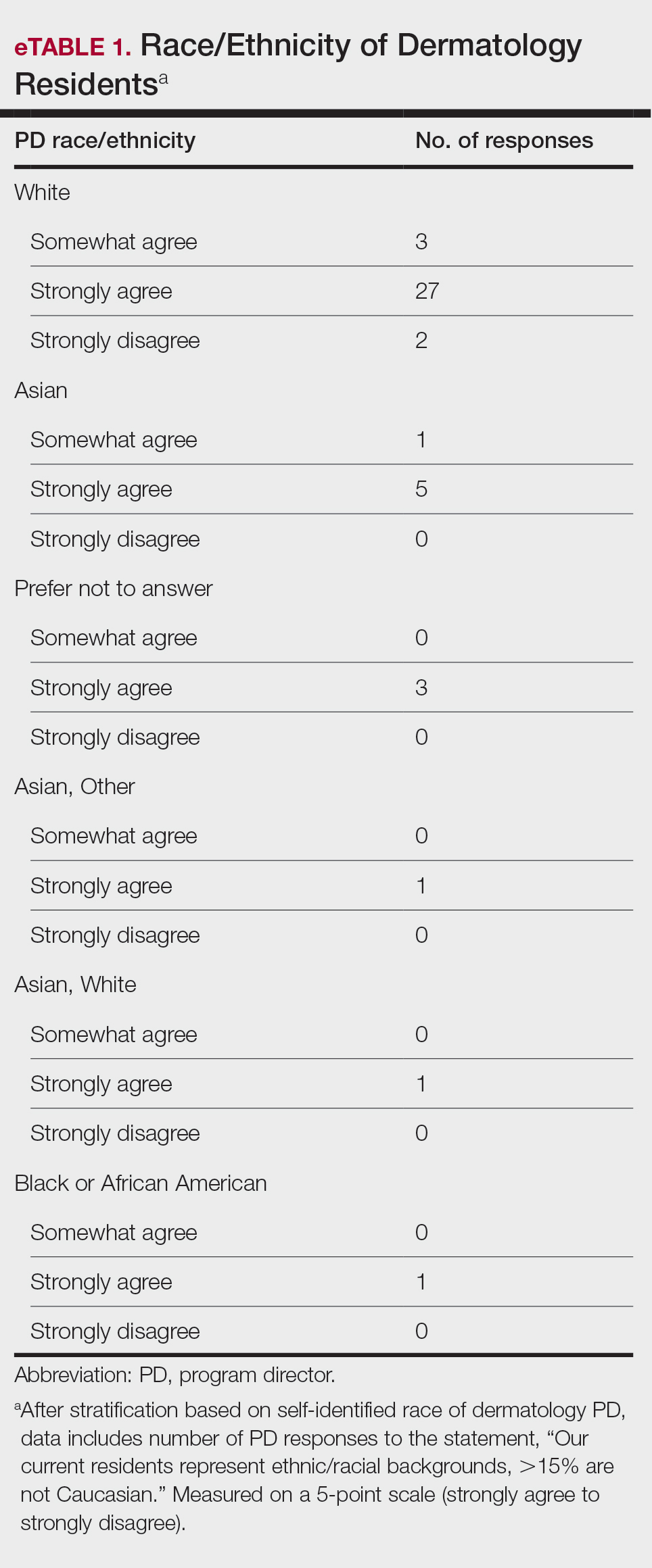

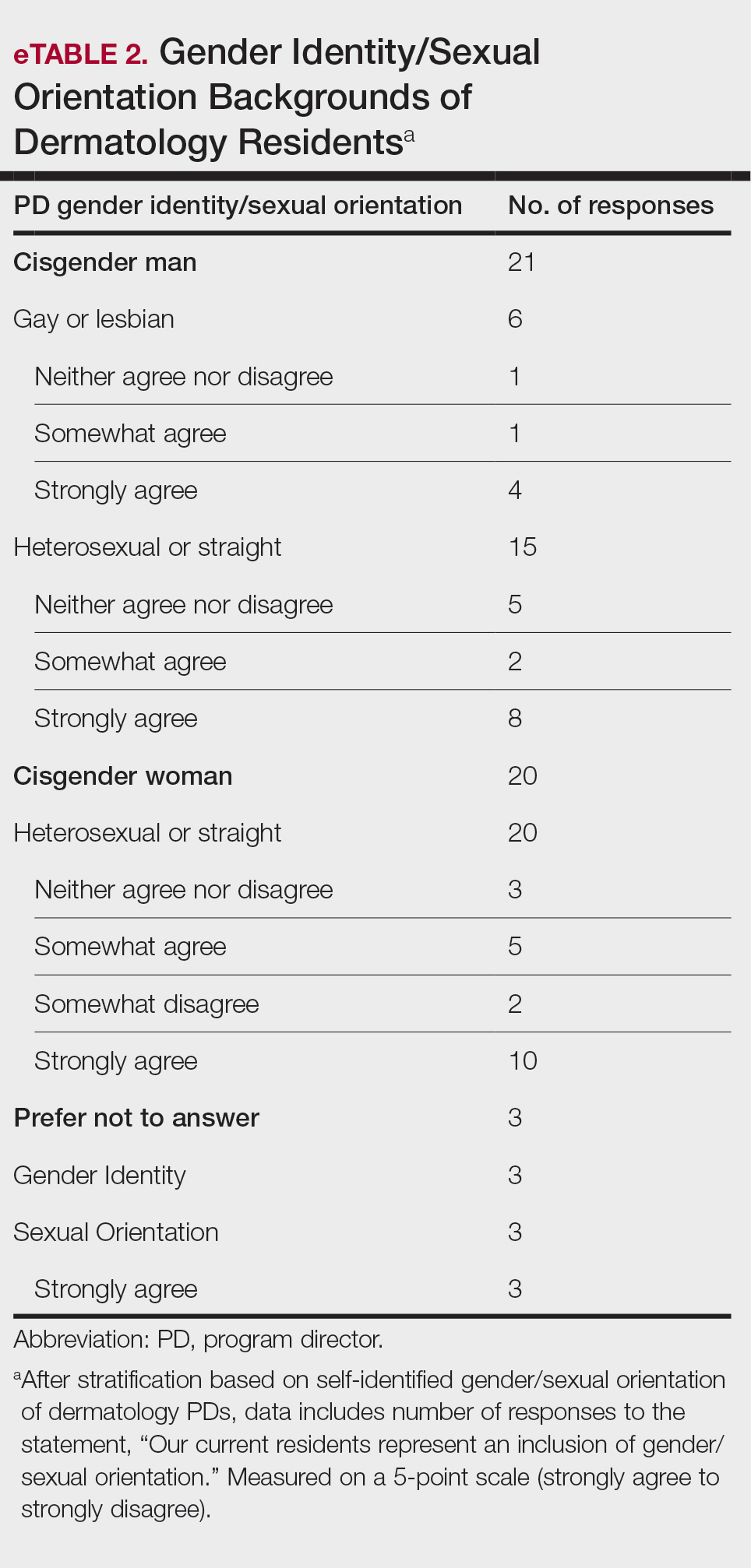

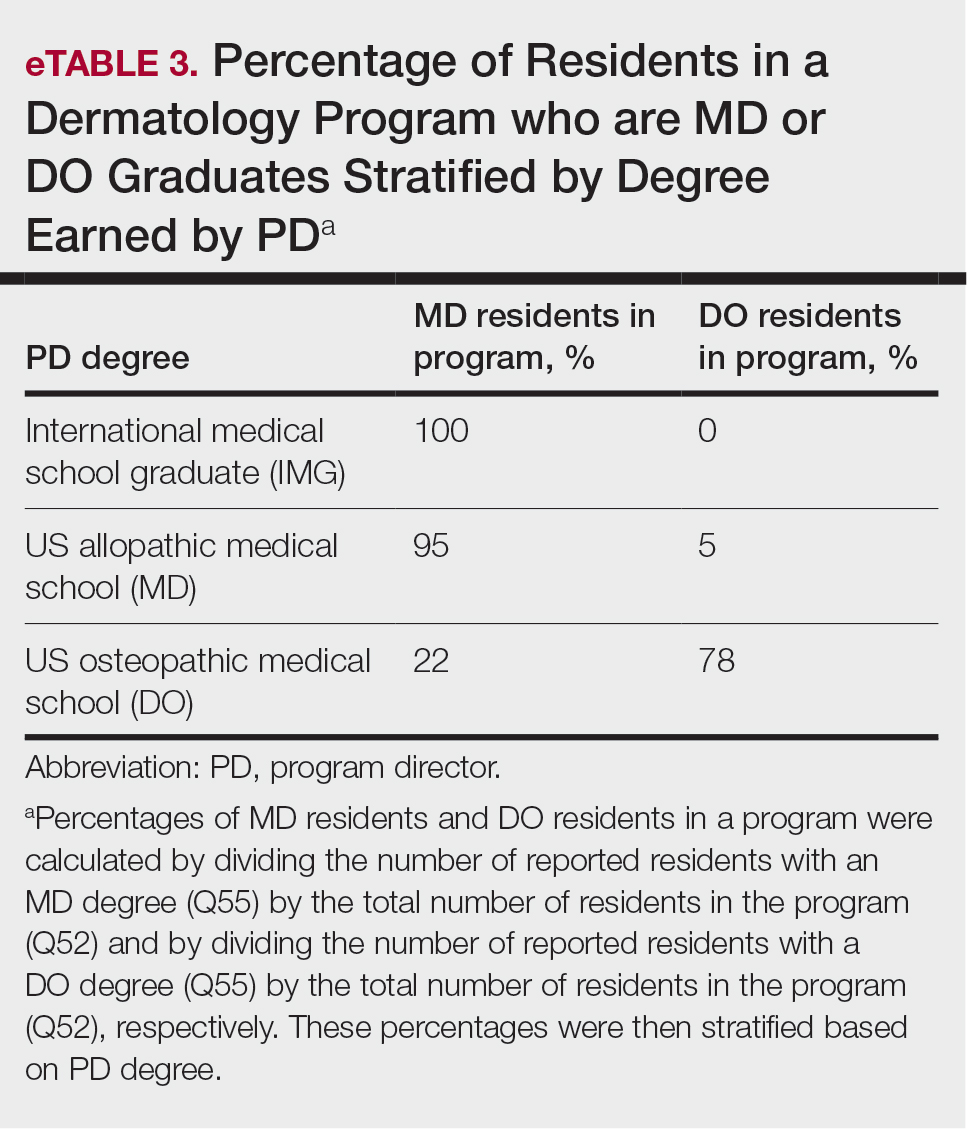

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion—Seventy-three percent (29/40) of programs have special diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or meetings specific to residency, 60% (24/40) have residency initiatives, and 55% (22/40) have a residency diversity committee. Eighty-six percent (42/49) of respondents strongly agreed that their current residents represent diverse ethnic and racial backgrounds (ie, >15% are not White). eTable 1 shows PD responses to this statement, which were stratified based on self-identified race. eTable 2 shows PD responses to the statement, “Our current residents represent an inclusion of gender/sexual orientation,” which were stratified based on self-identified gender identity/sexual orientation. Lastly, eTable 3 highlights the percentage of residents with an MD and DO degree, stratified based on PD degree.

Wellness—Forty-eight percent (20/42) of respondents indicated they are under stress and do not always have as much energy as before becoming a PD but do not feel burned out. Thirty-one percent (13/42) indicated they have 1 or more symptoms of burnout, such as emotional exhaustion. Eighty-six percent (36/42) are satisfied with their jobs overall (43% agree and 43% strongly agree [18/42 each]).

Evaluation System—Seventy-five percent (33/44) of programs deliver evaluations of residents by faculty online, 86% (38/44) of programs have PDs discuss evaluations in-person, and 20% (9/44) of programs have faculty evaluators discuss evaluations in-person. Seventy-seven percent (34/44) of programs have formal faculty-resident mentor-mentee programs. Clinical competency committee chair positions are filled by PDs, assistant PDs, or core faculty members 47%, 38%, and 16% of the time, respectively.

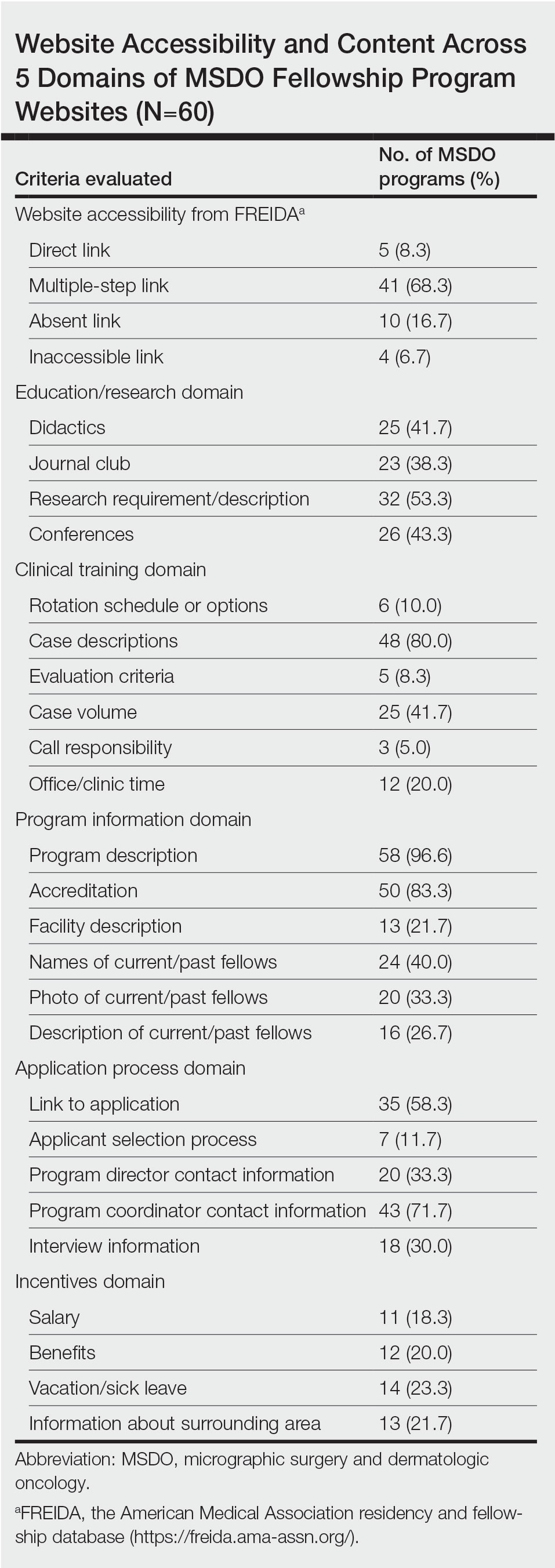

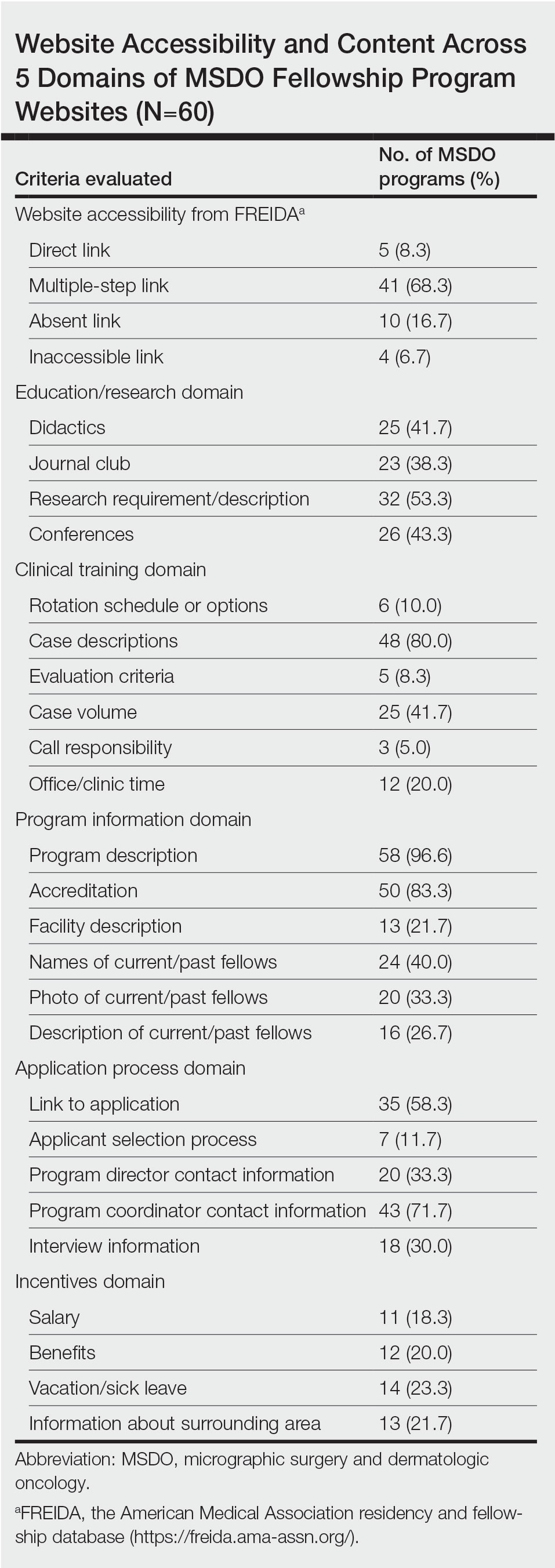

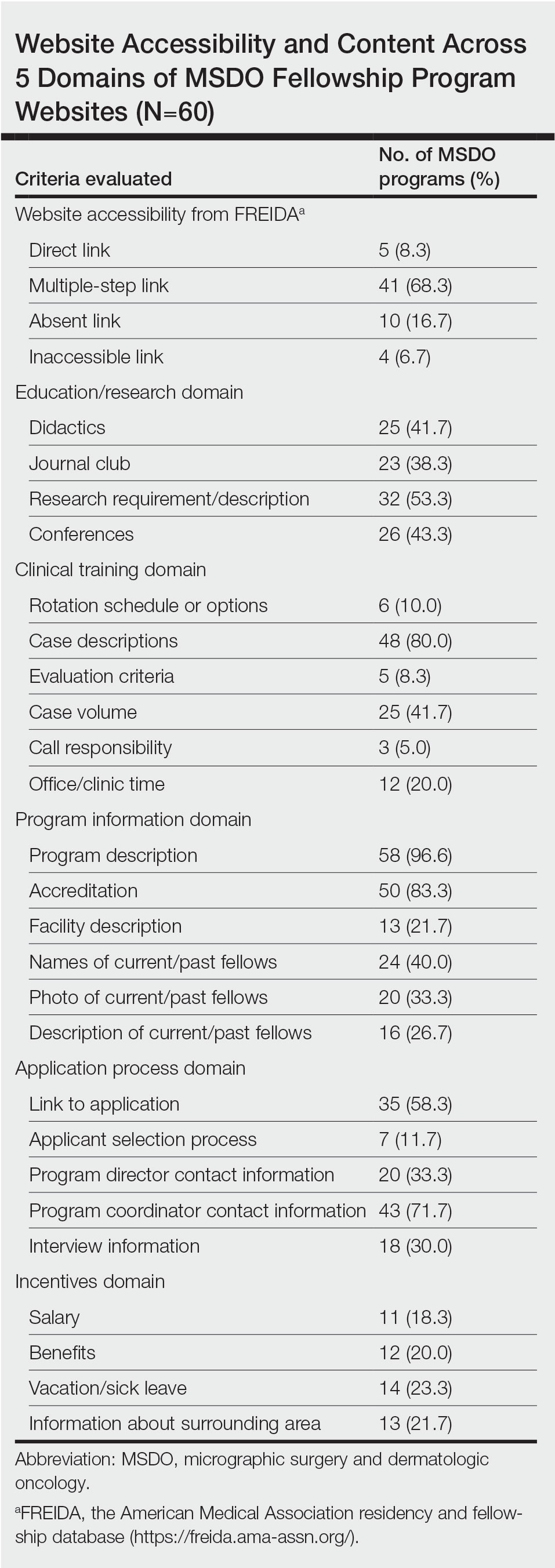

Graduation Outcomes of PGY4 Residents—About 28% (55/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with the majority (15% [29/55]) matching into Mohs micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology (MSDO) fellowships. Approximately 5% (9/199) and 4% (7/199) of graduates matched into dermatopathology and pediatric dermatology, respectively. The remaining 5% (10/199) of graduating residents applied to a fellowship but did not match. The majority (45% [91/199]) of residency graduates entered private practice after graduation. Approximately 21% (42/199) of graduating residents chose an academic practice with 17% (33/199), 2% (4/199), and 2% (3/199) of those positions being full-time, part-time, and adjunct, respectively.

Comment

The first annual APD survey is a novel data source and provides opportunities for areas of discussion and investigation. Evaluating the similarities and differences among dermatology residency programs across the United States can strengthen individual programs through collaboration and provide areas of cohesion among programs.

Diversity of PDs—An important area of discussion is diversity and PD demographics. Although DO students make up 1 in 4 US graduating medical students, they are not interviewed or ranked as often as MD students.2 Diversity in PD race and ethnicity may be worthy of investigation in future studies, as match rates and recruitment of diverse medical school applicants may be impacted by these demographics.

Continued Use of Telemedicine in Training—Since 2020, the benefits of virtual residency recruitment have been debated among PDs across all medical specialties. Points in favor of virtual interviews include cost savings for programs and especially for applicants, as well as time efficiency, reduced burden of travel, and reduced carbon footprint. A problem posed by virtual interviews is that candidates are unable to fully learn institutional cultures and social environments of the programs.3 Likewise, telehealth was an important means of clinical teaching for residents during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, with benefits that included cost-effectiveness and reduction of disparities in access to dermatologic care.4 Seventy-five percent (38/51) of PDs indicated that their program plans to include telemedicine in resident clinical rotation moving forward.

Resources Available—Our survey showed that resources available for residents, delivery of lectures and program time allocated to didactics, protected academic or study time for residents, and allocation of program time for CORE examinations are highly variable across programs. This could inspire future studies to be done to determine the differences in success of the resident on CORE examinations and in digesting material.

Postgraduate Career Plans and Fellowship Matches—Residents of programs that have a home MSDO fellowship are more likely to successfully match into a MSDO fellowship.5 Based on this survey, approximately 28% of graduating residents applied to a fellowship position, with 15%, 5%, and 3% matching into desired MSDO, dermatopathology, and pediatric dermatology fellowships, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine advantages and disadvantages that lead to residents reaching their career goals.

Limitations—Limitations of this study include a small sample size that may not adequately represent all ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs and selection bias toward respondents who are more likely to participate in survey-based research.

Conclusion

The APD plans to continue to administer this survey on an annual basis, with updates to the content and questions based on input from PDs. This survey will continue to provide valuable information to drive collaboration among residency programs and optimize the learning experience for residents. Our hope is that the response rate will increase in coming years, allowing us to draw more generalizable conclusions. Nonetheless, the survey data allow individual dermatology residency programs to compare their specific characteristics to other programs.

- Maciejko L, Cope A, Mara K, et al. A national survey of obstetrics and gynecology emergency training and deficits in office emergency preparation [A53]. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;139:16S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000826548.05758.26

- Lavertue SM, Terry R. A comparison of surgical subspecialty match rates in 2022 in the United States. Cureus. 2023;15:E37178. doi:10.7759/cureus.37178

- Domingo A, Rdesinski RE, Stenson A, et al. Virtual residency interviews: applicant perceptions regarding virtual interview effectiveness, advantages, and barriers. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14:224-228. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-21-00675.1

- Rustad AM, Lio PA. Pandemic pressure: teledermatology and health care disparities. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:2374373521996982. doi:10.1177/2374373521996982

- Rickstrew J, Rajpara A, Hocker TLH. Dermatology residency program influences chance of successful surgery fellowship match. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1040-1042. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002859

Educational organizations across several specialties, including internal medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, have formal surveys1; however, the field of dermatology has been without one. This study aimed to establish a formal survey for dermatology program directors (PDs) and clinician-educators. Because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Dermatology surveys do not capture all metrics relevant to dermatology residency educators, an annual survey for our specialty may be helpful to compare dermatology-specific data among programs. Responses could provide context and perspective to faculty and residents who respond to the ACGME annual survey, as our Association of Professors of Dermatology (APD) survey asks more in-depth questions, such as how often didactics occur and who leads them. Resident commute time and faculty demographics and training also are covered. Current ad hoc surveys disseminated through listserves of various medical associations contain overlapping questions and reflect relatively low response rates; dermatology PDs may benefit from a survey with a high response rate to which they can contribute future questions and topics that reflect recent trends and current needs in graduate medical education. As future surveys are administered, the results can be captured in a centralized database accessible by dermatology PDs.

Methods

A survey of PDs from 141 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs was conducted by the Residency Program Director Steering Committee of the APD from November 2022 to January 2023 using a prevalidated questionnaire. Personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each PD’s email listed in the ACGME accreditation data system. All survey responses were captured anonymously, with a number assigned to keep de-identified responses separate and organized. The survey consisted of 137 survey questions addressing topics that included program characteristics, PD demographics, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical rotation and educational conferences, available resident resources, quality improvement, clinical and didactic instruction, research content, diversity and inclusion, wellness, professionalism, evaluation systems, and graduate outcomes.

Data were collected using Qualtrics survey tools. After removing duplicate and incomplete surveys, data were analyzed using Qualtrics reports and Microsoft Excel for data plotting, averages, and range calculations.

Results

One hundred forty-one personalized survey links were created and sent individually to each program’s filed email obtained from the APD listserv. Fifty-three responses were recorded after removing duplicate or incomplete surveys (38% [53/141] response rate). As of May 2023, there were 144 ACGME-accredited dermatology residency programs due to 3 newly accredited programs in 2022-2023 academic year, which were not included in our survey population.

Program Characteristics—Forty-four respondents (83%) were from a university-based program. Fifty respondents (94%) were from programs that were ACGME accredited prior to 2020, while 3 programs (6%) were American Osteopathic Association accredited prior to singular accreditation. Seventy-one percent (38/53) of respondents had 1 or more associate PDs.

PD Demographics—Eighty-seven percent (45/52) of PDs who responded to the survey graduated from a US allopathic medical school (MD), 10% (5/52) graduated from a US osteopathic medical school (DO), and 4% (2/52) graduated from an international medical school. Seventy-four percent (35/47) of respondents were White, 17% (8/47) were Asian, and 2% (1/47) were Black or African American; this data was not provided for 4 respondents. Forty-eight percent (23/48) of PDs identified as cisgender man, 48% (23/48) identified as cisgender woman, and 4% (2/48) preferred not to answer. Eighty-one percent (38/47) of PDs identified as heterosexual or straight, 15% (7/47) identified as gay or lesbian, and 4% (2/47) preferred not to answer.

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Residency Training—Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 88% (45/51) of respondents incorporated telemedicine into the resident clinical rotation schedule. Moving forward, 75% (38/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to continue to incorporate telemedicine into the rotation schedule. Based on 50 responses, the average of educational conferences that became virtual at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic was 87%; based on 46 responses, the percentage of educational conferences that will remain virtual moving forward is 46%, while 90% (46/51) of respondents indicated that their programs plan to use virtual conferences in some capacity moving forward. Seventy-three percent (37/51) of respondents indicated that they plan to use virtual interviews as part of residency recruitment moving forward.