User login

Hospital readmission remains common for teens with nonfatal drug overdose

Approximately 1 in 5 adolescents hospitalized for nonfatal drug overdoses were readmitted within 6 months, based on data from more than 12,000 individuals.

Previous studies suggest that many adolescents fail to receive timely treatment for addiction after a nonfatal overdose, but the rates of hospital readmission in this population have not been examined, according to Julie Gaither, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Gaither and her colleague, John M. Leventhal, MD, also of Yale University, used data from the 2016 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine incidence and recurrent hospitalizations for nonfatal drug overdoses in adolescents. The study population included 12,952 patients aged 11-21 years who were admitted to a hospital after a nonfatal drug overdose in 2016. Of these, 15% were younger than 15 years, and 52.1% were females.

Overall, 76.2% of the overdoses involved opioids; 77.9% involved a prescription opioid, 15.3% involved heroin, and 7.9% involved fentanyl.

Across all drug overdoses, the majority (86.5%) were attributed to accidental intent and 11.8% were attributed to self-harm. Notably, females were nearly four times more likely than males to attempt suicide (odds ratio, 3.57). After the initial hospitalization, 79.3% of the patients were discharged home, and 11.5% went to a short-term care facility.

The 6-month hospital readmission rate was 21.4%. Of the patients readmitted for any cause, 18.2% of readmissions were for recurrent overdoses, and 92.1% of these were attributed to opioids.

The median cost of the initial hospital admission was $23,705 (ranging from $11,902 to $54,682) and the median cost of the first readmission was $25,416 (ranging from $13,905 to $48,810). In 42.1% of all hospitalizations, Medicaid was the primary payer.

The study findings were limited by the relatively high number of Medicaid patients, which may limit generalizability, but is strengthened by the large sample size.

The findings highlight not only the need for prevention efforts to limit opioid use among adolescents, but also “speak to the need for timely evidenced-based addiction treatment and appropriate follow-up care for teens following hospitalization for a nonfatal drug overdose,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

Potential for postpandemic surge in drug use

Interestingly, some recent research has shown a decline in teens’ substance use during the pandemic, Kelly Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, said in an interview.

“However, as the world begins ‘opening up’ again, I suspect rates of drug use will rise – especially with the significant burden of mental health issues adolescents have struggled with during the last few years,” said Dr. Curran, who was not involved with the current study.

“Sadly, I am not surprised by this study’s findings. Too often, teens with substance abuse issues are not connected to effective, evidenced-based treatment, and for those who are, the wait list can be long,” she said.

“Teens who are misusing drugs – either to get high or to attempt suicide – who are admitted for nonfatal overdose have a high rate of readmission for recurrent drug overdose,” Dr. Curran said. “This high rate of readmission has serious social and financial implications,” she added. “This study is part of a growing body of literature that supports the importance of getting adolescents into effective, evidence-based substance abuse treatment, such as medication-assisted treatment in opioid abuse. However, we also should be advocating for improved funding for and access to these treatments for all individuals.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Gaither had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Approximately 1 in 5 adolescents hospitalized for nonfatal drug overdoses were readmitted within 6 months, based on data from more than 12,000 individuals.

Previous studies suggest that many adolescents fail to receive timely treatment for addiction after a nonfatal overdose, but the rates of hospital readmission in this population have not been examined, according to Julie Gaither, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Gaither and her colleague, John M. Leventhal, MD, also of Yale University, used data from the 2016 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine incidence and recurrent hospitalizations for nonfatal drug overdoses in adolescents. The study population included 12,952 patients aged 11-21 years who were admitted to a hospital after a nonfatal drug overdose in 2016. Of these, 15% were younger than 15 years, and 52.1% were females.

Overall, 76.2% of the overdoses involved opioids; 77.9% involved a prescription opioid, 15.3% involved heroin, and 7.9% involved fentanyl.

Across all drug overdoses, the majority (86.5%) were attributed to accidental intent and 11.8% were attributed to self-harm. Notably, females were nearly four times more likely than males to attempt suicide (odds ratio, 3.57). After the initial hospitalization, 79.3% of the patients were discharged home, and 11.5% went to a short-term care facility.

The 6-month hospital readmission rate was 21.4%. Of the patients readmitted for any cause, 18.2% of readmissions were for recurrent overdoses, and 92.1% of these were attributed to opioids.

The median cost of the initial hospital admission was $23,705 (ranging from $11,902 to $54,682) and the median cost of the first readmission was $25,416 (ranging from $13,905 to $48,810). In 42.1% of all hospitalizations, Medicaid was the primary payer.

The study findings were limited by the relatively high number of Medicaid patients, which may limit generalizability, but is strengthened by the large sample size.

The findings highlight not only the need for prevention efforts to limit opioid use among adolescents, but also “speak to the need for timely evidenced-based addiction treatment and appropriate follow-up care for teens following hospitalization for a nonfatal drug overdose,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

Potential for postpandemic surge in drug use

Interestingly, some recent research has shown a decline in teens’ substance use during the pandemic, Kelly Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, said in an interview.

“However, as the world begins ‘opening up’ again, I suspect rates of drug use will rise – especially with the significant burden of mental health issues adolescents have struggled with during the last few years,” said Dr. Curran, who was not involved with the current study.

“Sadly, I am not surprised by this study’s findings. Too often, teens with substance abuse issues are not connected to effective, evidenced-based treatment, and for those who are, the wait list can be long,” she said.

“Teens who are misusing drugs – either to get high or to attempt suicide – who are admitted for nonfatal overdose have a high rate of readmission for recurrent drug overdose,” Dr. Curran said. “This high rate of readmission has serious social and financial implications,” she added. “This study is part of a growing body of literature that supports the importance of getting adolescents into effective, evidence-based substance abuse treatment, such as medication-assisted treatment in opioid abuse. However, we also should be advocating for improved funding for and access to these treatments for all individuals.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Gaither had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Approximately 1 in 5 adolescents hospitalized for nonfatal drug overdoses were readmitted within 6 months, based on data from more than 12,000 individuals.

Previous studies suggest that many adolescents fail to receive timely treatment for addiction after a nonfatal overdose, but the rates of hospital readmission in this population have not been examined, according to Julie Gaither, PhD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

In a study presented at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies, Dr. Gaither and her colleague, John M. Leventhal, MD, also of Yale University, used data from the 2016 Nationwide Readmissions Database to examine incidence and recurrent hospitalizations for nonfatal drug overdoses in adolescents. The study population included 12,952 patients aged 11-21 years who were admitted to a hospital after a nonfatal drug overdose in 2016. Of these, 15% were younger than 15 years, and 52.1% were females.

Overall, 76.2% of the overdoses involved opioids; 77.9% involved a prescription opioid, 15.3% involved heroin, and 7.9% involved fentanyl.

Across all drug overdoses, the majority (86.5%) were attributed to accidental intent and 11.8% were attributed to self-harm. Notably, females were nearly four times more likely than males to attempt suicide (odds ratio, 3.57). After the initial hospitalization, 79.3% of the patients were discharged home, and 11.5% went to a short-term care facility.

The 6-month hospital readmission rate was 21.4%. Of the patients readmitted for any cause, 18.2% of readmissions were for recurrent overdoses, and 92.1% of these were attributed to opioids.

The median cost of the initial hospital admission was $23,705 (ranging from $11,902 to $54,682) and the median cost of the first readmission was $25,416 (ranging from $13,905 to $48,810). In 42.1% of all hospitalizations, Medicaid was the primary payer.

The study findings were limited by the relatively high number of Medicaid patients, which may limit generalizability, but is strengthened by the large sample size.

The findings highlight not only the need for prevention efforts to limit opioid use among adolescents, but also “speak to the need for timely evidenced-based addiction treatment and appropriate follow-up care for teens following hospitalization for a nonfatal drug overdose,” the researchers wrote in their abstract.

Potential for postpandemic surge in drug use

Interestingly, some recent research has shown a decline in teens’ substance use during the pandemic, Kelly Curran, MD, of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, said in an interview.

“However, as the world begins ‘opening up’ again, I suspect rates of drug use will rise – especially with the significant burden of mental health issues adolescents have struggled with during the last few years,” said Dr. Curran, who was not involved with the current study.

“Sadly, I am not surprised by this study’s findings. Too often, teens with substance abuse issues are not connected to effective, evidenced-based treatment, and for those who are, the wait list can be long,” she said.

“Teens who are misusing drugs – either to get high or to attempt suicide – who are admitted for nonfatal overdose have a high rate of readmission for recurrent drug overdose,” Dr. Curran said. “This high rate of readmission has serious social and financial implications,” she added. “This study is part of a growing body of literature that supports the importance of getting adolescents into effective, evidence-based substance abuse treatment, such as medication-assisted treatment in opioid abuse. However, we also should be advocating for improved funding for and access to these treatments for all individuals.”

The study received no outside funding. Dr. Gaither had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Curran had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM PAS 2022

Substance use disorders increase risk for death from COVID-19

MADRID, Spain – – compared with the general population. Such are the findings of a line of research led by Mexican psychiatrist Nora Volkow, MD, director of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

A pioneer in the use of brain imaging to investigate how substance use affects brain functions and one of Time magazine’s “Top 100 People Who Shape Our World,” she led the Inaugural Conference at the XXXI Congress of the Spanish Society of Clinical Pharmacology “Drugs and Actions During the Pandemic.” Dr. Volkow spoke about the effects that the current health crisis has had on drug use and the social challenges that arose from lockdowns. She also presented and discussed the results of studies being conducted at NIDA that “are aimed at reviewing what we’ve learned and what the consequences of COVID-19 have been with respect to substance abuse disorder.”

As Dr. Volkow pointed out, drugs affect much more than just the brain. “In particular, the heart, the lungs, the immune system – all of these are significantly harmed by substances like tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and methamphetamine. This is why, since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve been worried about seeing what consequences SARS-CoV-2 was going to have on users of these substances, especially in light of the great toll this disease takes on the respiratory system and the vascular system.”

Pulmonary ‘predisposition’ and race

Dr. Volkow and her team launched several studies to get a more thorough understanding of the link between substance abuse disorders and poor COVID-19 prognoses. One of them was based on analyses from electronic health records in the United States. The purpose was to determine COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients based on the type of use disorder (for example, alcohol, opioid, cannabis, cocaine).

“The results showed that regardless of the drug type, all users of these substances had both a higher risk of being infected by COVID-19 and a higher death rate in comparison with the rest of the population,” said Dr. Volkow. “This surprised us, because there’s no evidence that drugs themselves make the virus more infectious. However, what the results did clearly indicate to us was that using these substances was associated with behavior that put these individuals at a greater risk for infection,” Dr. Volkow explained.

“In addition,” she continued, “using, for example, tobacco or cannabis causes inflammation in the lungs. It seems that, as a result, they end up being more vulnerable to infection by COVID. And this has consequences, above all, in terms of mortality.”

Another finding was that, among patients with substance use disorders, race had the largest effect on COVID risk. “From the very start, we saw that, compared with White individuals, Black individuals showed a much higher risk of not only getting COVID, but also dying from it,” said Dr. Volkow. “Therefore, on the one hand, our data show that drug users are more vulnerable to COVID-19 and, on the other hand, they reflect that within this group, Black individuals are even more vulnerable.”

In her presentation, Dr. Volkow drew particular attention to the impact that social surroundings have on these patients and the decisive role they played in terms of vulnerability. “It’s a very complex issue, what with the various factors at play: family, social environment. ... A person living in an at-risk situation can more easily get drugs or even prescription medication, which can also be abused.”

The psychiatrist stressed that when it comes to addictive disorders (and related questions such as prevention, treatment, and social reintegration), one of the most crucial factors has to do with the individual’s social support structures. “The studies also brought to light the role that social interaction has as an inhibitory factor with regard to drug use,” said Dr. Volkow. “And indeed, adequate adherence to treatment requires that the necessary support systems be maintained.”

In the context of the pandemic, this social aspect was also key, especially concerning the high death rate among substance use disorder patients with COVID-19. “There are very significant social determinants, such as the stigma associated with these groups – a stigma that makes these individuals more likely to hesitate to seek out treatment for diseases that may be starting to take hold, in this case COVID-19.”

On that note, Dr. Volkow emphasized the importance of treating drug addicts as though they had a chronic disease in need of treatment. “In fact, the prevalence of pathologies such as hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and dementia is much higher in these individuals than in the general population,” she said. “However, this isn’t widely known. The data reflect that not only the prevalence of these diseases, but also the severity of the symptoms, is higher, and this has a lot to do with these individuals’ reticence when it comes to reaching out for medical care. Added to that are the effects of their economic situation and other factors, such as stress (which can trigger a relapse), lack of ready access to medications, and limited access to community support or other sources of social connection.”

Opioids and COVID-19

As for drug use during the pandemic, Dr. Volkow provided context by mentioning that in the United States, the experts and authorities have spent two decades fighting the epidemic of opioid-related drug overdoses, which has caused many deaths. “And on top of this epidemic – one that we still haven’t been able to get control of – there’s the situation brought about by COVID-19. So, we had to see the consequences of a pandemic crossing paths with an epidemic.”

The United States’s epidemic of overdose deaths started with the use of opioid painkillers, medications which are overprescribed. Another issue that the United States faces is that many drugs are contaminated with fentanyl. This contamination has caused an increase in deaths.

“In the United States, fentanyl is everywhere,” said Dr. Volkow. “And what’s more concerning: almost a third of this fentanyl comes in pills that are sold as benzodiazepines. With this comes a high risk for overdose. In line with this, we saw overdose deaths among adolescents nearly double in 1 year, an increase which is likely related to these contaminated pills. It’s a risk that’s just below the surface. We’ve got to be vigilant, because this phenomenon is expected to eventually spread to Europe. After all, these pills are very cheap, hence the rapid increase in their use.”

To provide figures on drug use and overdose deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, Dr. Volkow referred to COVID-19 data provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data indicate that of the 70,630 drug overdose deaths that occurred in 2019, 49,860 involved opioids (whether prescribed or illicit). “And these numbers have continued to rise, so much so that the current situation can be classified as catastrophic – because this increase has been even greater during the pandemic due to the rise in the use of all drugs,” said Dr. Volkow.

Dr. Volkow referred to an NCHS study that looked at the period between September 2020 and September 2021, finding a 15.9% increase in the number of drug overdose deaths. A breakdown of these data shows that the highest percentage corresponds to deaths from “other psychostimulants,” primarily methamphetamines (35.7%). This category is followed by deaths involving synthetic opioids, mostly illicit fentanyl (25.8%), and deaths from cocaine (13.4%).

“These figures indicate that, for the first time in history, the United States had over 100,000 overdose deaths in 1 year,” said Dr. Volkow. “This is something that has never happened. We can only infer that the pandemic had a hand in making the overdose crisis even worse than it already was.”

As Dr. Volkow explained, policies related to handling overdoses and prescribing medications have been changed in the context of COVID-19. Addiction treatment consequently has been provided through a larger number of telehealth services, and measures such as greater access to treatment for comorbid conditions, expanded access to behavioral treatments, and the establishment of mental health hotlines have been undertaken.

Children’s cognitive development

Dr. Volkow also spoke about another of NIDA’s current subjects of research: The role that damage or compromise from drugs has on the neural circuits involved in reinforcement systems. “It’s important that we make people aware of the significance of what’s at play there, because the greatest damage that can be inflicted on the brain comes from using any type of drug during adolescence. In these cases, the likelihood of having an addictive disorder as an adult significantly increases.”

Within this framework, her team has also investigated the impact of the pandemic on the cognitive development of infants under 1 year of age. One of these studies was a pilot program in which pregnant women participated. “We found that children born during the pandemic had lower cognitive development: n = 112 versus n = 554 of those born before January 2019.”

“None of the mothers or children in the study had been infected with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Volkow explained. “But the results clearly reflect the negative effect of the circumstances brought about by the pandemic, especially the high level of stress, the isolation, and the lack of stimuli. Another study, currently in preprint, is based on imaging. It analyzed the impact on myelination in children not exposed to COVID-19 but born during the pandemic, compared with pre-pandemic infants. The data showed significantly reduced areas of myelin development (P < .05) in those born after 2019. And the researchers didn’t find significant differences in gestation duration or birth weight.”

The longitudinal characteristics of these studies will let us see whether a change in these individuals’ social circumstances over time also brings to light cognitive changes, even the recovery of lost or underdeveloped cognitive processes, Dr. Volkow concluded.

Dr. Volkow has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID, Spain – – compared with the general population. Such are the findings of a line of research led by Mexican psychiatrist Nora Volkow, MD, director of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

A pioneer in the use of brain imaging to investigate how substance use affects brain functions and one of Time magazine’s “Top 100 People Who Shape Our World,” she led the Inaugural Conference at the XXXI Congress of the Spanish Society of Clinical Pharmacology “Drugs and Actions During the Pandemic.” Dr. Volkow spoke about the effects that the current health crisis has had on drug use and the social challenges that arose from lockdowns. She also presented and discussed the results of studies being conducted at NIDA that “are aimed at reviewing what we’ve learned and what the consequences of COVID-19 have been with respect to substance abuse disorder.”

As Dr. Volkow pointed out, drugs affect much more than just the brain. “In particular, the heart, the lungs, the immune system – all of these are significantly harmed by substances like tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and methamphetamine. This is why, since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve been worried about seeing what consequences SARS-CoV-2 was going to have on users of these substances, especially in light of the great toll this disease takes on the respiratory system and the vascular system.”

Pulmonary ‘predisposition’ and race

Dr. Volkow and her team launched several studies to get a more thorough understanding of the link between substance abuse disorders and poor COVID-19 prognoses. One of them was based on analyses from electronic health records in the United States. The purpose was to determine COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients based on the type of use disorder (for example, alcohol, opioid, cannabis, cocaine).

“The results showed that regardless of the drug type, all users of these substances had both a higher risk of being infected by COVID-19 and a higher death rate in comparison with the rest of the population,” said Dr. Volkow. “This surprised us, because there’s no evidence that drugs themselves make the virus more infectious. However, what the results did clearly indicate to us was that using these substances was associated with behavior that put these individuals at a greater risk for infection,” Dr. Volkow explained.

“In addition,” she continued, “using, for example, tobacco or cannabis causes inflammation in the lungs. It seems that, as a result, they end up being more vulnerable to infection by COVID. And this has consequences, above all, in terms of mortality.”

Another finding was that, among patients with substance use disorders, race had the largest effect on COVID risk. “From the very start, we saw that, compared with White individuals, Black individuals showed a much higher risk of not only getting COVID, but also dying from it,” said Dr. Volkow. “Therefore, on the one hand, our data show that drug users are more vulnerable to COVID-19 and, on the other hand, they reflect that within this group, Black individuals are even more vulnerable.”

In her presentation, Dr. Volkow drew particular attention to the impact that social surroundings have on these patients and the decisive role they played in terms of vulnerability. “It’s a very complex issue, what with the various factors at play: family, social environment. ... A person living in an at-risk situation can more easily get drugs or even prescription medication, which can also be abused.”

The psychiatrist stressed that when it comes to addictive disorders (and related questions such as prevention, treatment, and social reintegration), one of the most crucial factors has to do with the individual’s social support structures. “The studies also brought to light the role that social interaction has as an inhibitory factor with regard to drug use,” said Dr. Volkow. “And indeed, adequate adherence to treatment requires that the necessary support systems be maintained.”

In the context of the pandemic, this social aspect was also key, especially concerning the high death rate among substance use disorder patients with COVID-19. “There are very significant social determinants, such as the stigma associated with these groups – a stigma that makes these individuals more likely to hesitate to seek out treatment for diseases that may be starting to take hold, in this case COVID-19.”

On that note, Dr. Volkow emphasized the importance of treating drug addicts as though they had a chronic disease in need of treatment. “In fact, the prevalence of pathologies such as hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and dementia is much higher in these individuals than in the general population,” she said. “However, this isn’t widely known. The data reflect that not only the prevalence of these diseases, but also the severity of the symptoms, is higher, and this has a lot to do with these individuals’ reticence when it comes to reaching out for medical care. Added to that are the effects of their economic situation and other factors, such as stress (which can trigger a relapse), lack of ready access to medications, and limited access to community support or other sources of social connection.”

Opioids and COVID-19

As for drug use during the pandemic, Dr. Volkow provided context by mentioning that in the United States, the experts and authorities have spent two decades fighting the epidemic of opioid-related drug overdoses, which has caused many deaths. “And on top of this epidemic – one that we still haven’t been able to get control of – there’s the situation brought about by COVID-19. So, we had to see the consequences of a pandemic crossing paths with an epidemic.”

The United States’s epidemic of overdose deaths started with the use of opioid painkillers, medications which are overprescribed. Another issue that the United States faces is that many drugs are contaminated with fentanyl. This contamination has caused an increase in deaths.

“In the United States, fentanyl is everywhere,” said Dr. Volkow. “And what’s more concerning: almost a third of this fentanyl comes in pills that are sold as benzodiazepines. With this comes a high risk for overdose. In line with this, we saw overdose deaths among adolescents nearly double in 1 year, an increase which is likely related to these contaminated pills. It’s a risk that’s just below the surface. We’ve got to be vigilant, because this phenomenon is expected to eventually spread to Europe. After all, these pills are very cheap, hence the rapid increase in their use.”

To provide figures on drug use and overdose deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, Dr. Volkow referred to COVID-19 data provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data indicate that of the 70,630 drug overdose deaths that occurred in 2019, 49,860 involved opioids (whether prescribed or illicit). “And these numbers have continued to rise, so much so that the current situation can be classified as catastrophic – because this increase has been even greater during the pandemic due to the rise in the use of all drugs,” said Dr. Volkow.

Dr. Volkow referred to an NCHS study that looked at the period between September 2020 and September 2021, finding a 15.9% increase in the number of drug overdose deaths. A breakdown of these data shows that the highest percentage corresponds to deaths from “other psychostimulants,” primarily methamphetamines (35.7%). This category is followed by deaths involving synthetic opioids, mostly illicit fentanyl (25.8%), and deaths from cocaine (13.4%).

“These figures indicate that, for the first time in history, the United States had over 100,000 overdose deaths in 1 year,” said Dr. Volkow. “This is something that has never happened. We can only infer that the pandemic had a hand in making the overdose crisis even worse than it already was.”

As Dr. Volkow explained, policies related to handling overdoses and prescribing medications have been changed in the context of COVID-19. Addiction treatment consequently has been provided through a larger number of telehealth services, and measures such as greater access to treatment for comorbid conditions, expanded access to behavioral treatments, and the establishment of mental health hotlines have been undertaken.

Children’s cognitive development

Dr. Volkow also spoke about another of NIDA’s current subjects of research: The role that damage or compromise from drugs has on the neural circuits involved in reinforcement systems. “It’s important that we make people aware of the significance of what’s at play there, because the greatest damage that can be inflicted on the brain comes from using any type of drug during adolescence. In these cases, the likelihood of having an addictive disorder as an adult significantly increases.”

Within this framework, her team has also investigated the impact of the pandemic on the cognitive development of infants under 1 year of age. One of these studies was a pilot program in which pregnant women participated. “We found that children born during the pandemic had lower cognitive development: n = 112 versus n = 554 of those born before January 2019.”

“None of the mothers or children in the study had been infected with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Volkow explained. “But the results clearly reflect the negative effect of the circumstances brought about by the pandemic, especially the high level of stress, the isolation, and the lack of stimuli. Another study, currently in preprint, is based on imaging. It analyzed the impact on myelination in children not exposed to COVID-19 but born during the pandemic, compared with pre-pandemic infants. The data showed significantly reduced areas of myelin development (P < .05) in those born after 2019. And the researchers didn’t find significant differences in gestation duration or birth weight.”

The longitudinal characteristics of these studies will let us see whether a change in these individuals’ social circumstances over time also brings to light cognitive changes, even the recovery of lost or underdeveloped cognitive processes, Dr. Volkow concluded.

Dr. Volkow has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MADRID, Spain – – compared with the general population. Such are the findings of a line of research led by Mexican psychiatrist Nora Volkow, MD, director of the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

A pioneer in the use of brain imaging to investigate how substance use affects brain functions and one of Time magazine’s “Top 100 People Who Shape Our World,” she led the Inaugural Conference at the XXXI Congress of the Spanish Society of Clinical Pharmacology “Drugs and Actions During the Pandemic.” Dr. Volkow spoke about the effects that the current health crisis has had on drug use and the social challenges that arose from lockdowns. She also presented and discussed the results of studies being conducted at NIDA that “are aimed at reviewing what we’ve learned and what the consequences of COVID-19 have been with respect to substance abuse disorder.”

As Dr. Volkow pointed out, drugs affect much more than just the brain. “In particular, the heart, the lungs, the immune system – all of these are significantly harmed by substances like tobacco, alcohol, cocaine, and methamphetamine. This is why, since the beginning of the pandemic, we’ve been worried about seeing what consequences SARS-CoV-2 was going to have on users of these substances, especially in light of the great toll this disease takes on the respiratory system and the vascular system.”

Pulmonary ‘predisposition’ and race

Dr. Volkow and her team launched several studies to get a more thorough understanding of the link between substance abuse disorders and poor COVID-19 prognoses. One of them was based on analyses from electronic health records in the United States. The purpose was to determine COVID-19 risk and outcomes in patients based on the type of use disorder (for example, alcohol, opioid, cannabis, cocaine).

“The results showed that regardless of the drug type, all users of these substances had both a higher risk of being infected by COVID-19 and a higher death rate in comparison with the rest of the population,” said Dr. Volkow. “This surprised us, because there’s no evidence that drugs themselves make the virus more infectious. However, what the results did clearly indicate to us was that using these substances was associated with behavior that put these individuals at a greater risk for infection,” Dr. Volkow explained.

“In addition,” she continued, “using, for example, tobacco or cannabis causes inflammation in the lungs. It seems that, as a result, they end up being more vulnerable to infection by COVID. And this has consequences, above all, in terms of mortality.”

Another finding was that, among patients with substance use disorders, race had the largest effect on COVID risk. “From the very start, we saw that, compared with White individuals, Black individuals showed a much higher risk of not only getting COVID, but also dying from it,” said Dr. Volkow. “Therefore, on the one hand, our data show that drug users are more vulnerable to COVID-19 and, on the other hand, they reflect that within this group, Black individuals are even more vulnerable.”

In her presentation, Dr. Volkow drew particular attention to the impact that social surroundings have on these patients and the decisive role they played in terms of vulnerability. “It’s a very complex issue, what with the various factors at play: family, social environment. ... A person living in an at-risk situation can more easily get drugs or even prescription medication, which can also be abused.”

The psychiatrist stressed that when it comes to addictive disorders (and related questions such as prevention, treatment, and social reintegration), one of the most crucial factors has to do with the individual’s social support structures. “The studies also brought to light the role that social interaction has as an inhibitory factor with regard to drug use,” said Dr. Volkow. “And indeed, adequate adherence to treatment requires that the necessary support systems be maintained.”

In the context of the pandemic, this social aspect was also key, especially concerning the high death rate among substance use disorder patients with COVID-19. “There are very significant social determinants, such as the stigma associated with these groups – a stigma that makes these individuals more likely to hesitate to seek out treatment for diseases that may be starting to take hold, in this case COVID-19.”

On that note, Dr. Volkow emphasized the importance of treating drug addicts as though they had a chronic disease in need of treatment. “In fact, the prevalence of pathologies such as hypertension, diabetes, cancer, and dementia is much higher in these individuals than in the general population,” she said. “However, this isn’t widely known. The data reflect that not only the prevalence of these diseases, but also the severity of the symptoms, is higher, and this has a lot to do with these individuals’ reticence when it comes to reaching out for medical care. Added to that are the effects of their economic situation and other factors, such as stress (which can trigger a relapse), lack of ready access to medications, and limited access to community support or other sources of social connection.”

Opioids and COVID-19

As for drug use during the pandemic, Dr. Volkow provided context by mentioning that in the United States, the experts and authorities have spent two decades fighting the epidemic of opioid-related drug overdoses, which has caused many deaths. “And on top of this epidemic – one that we still haven’t been able to get control of – there’s the situation brought about by COVID-19. So, we had to see the consequences of a pandemic crossing paths with an epidemic.”

The United States’s epidemic of overdose deaths started with the use of opioid painkillers, medications which are overprescribed. Another issue that the United States faces is that many drugs are contaminated with fentanyl. This contamination has caused an increase in deaths.

“In the United States, fentanyl is everywhere,” said Dr. Volkow. “And what’s more concerning: almost a third of this fentanyl comes in pills that are sold as benzodiazepines. With this comes a high risk for overdose. In line with this, we saw overdose deaths among adolescents nearly double in 1 year, an increase which is likely related to these contaminated pills. It’s a risk that’s just below the surface. We’ve got to be vigilant, because this phenomenon is expected to eventually spread to Europe. After all, these pills are very cheap, hence the rapid increase in their use.”

To provide figures on drug use and overdose deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, Dr. Volkow referred to COVID-19 data provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The data indicate that of the 70,630 drug overdose deaths that occurred in 2019, 49,860 involved opioids (whether prescribed or illicit). “And these numbers have continued to rise, so much so that the current situation can be classified as catastrophic – because this increase has been even greater during the pandemic due to the rise in the use of all drugs,” said Dr. Volkow.

Dr. Volkow referred to an NCHS study that looked at the period between September 2020 and September 2021, finding a 15.9% increase in the number of drug overdose deaths. A breakdown of these data shows that the highest percentage corresponds to deaths from “other psychostimulants,” primarily methamphetamines (35.7%). This category is followed by deaths involving synthetic opioids, mostly illicit fentanyl (25.8%), and deaths from cocaine (13.4%).

“These figures indicate that, for the first time in history, the United States had over 100,000 overdose deaths in 1 year,” said Dr. Volkow. “This is something that has never happened. We can only infer that the pandemic had a hand in making the overdose crisis even worse than it already was.”

As Dr. Volkow explained, policies related to handling overdoses and prescribing medications have been changed in the context of COVID-19. Addiction treatment consequently has been provided through a larger number of telehealth services, and measures such as greater access to treatment for comorbid conditions, expanded access to behavioral treatments, and the establishment of mental health hotlines have been undertaken.

Children’s cognitive development

Dr. Volkow also spoke about another of NIDA’s current subjects of research: The role that damage or compromise from drugs has on the neural circuits involved in reinforcement systems. “It’s important that we make people aware of the significance of what’s at play there, because the greatest damage that can be inflicted on the brain comes from using any type of drug during adolescence. In these cases, the likelihood of having an addictive disorder as an adult significantly increases.”

Within this framework, her team has also investigated the impact of the pandemic on the cognitive development of infants under 1 year of age. One of these studies was a pilot program in which pregnant women participated. “We found that children born during the pandemic had lower cognitive development: n = 112 versus n = 554 of those born before January 2019.”

“None of the mothers or children in the study had been infected with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Volkow explained. “But the results clearly reflect the negative effect of the circumstances brought about by the pandemic, especially the high level of stress, the isolation, and the lack of stimuli. Another study, currently in preprint, is based on imaging. It analyzed the impact on myelination in children not exposed to COVID-19 but born during the pandemic, compared with pre-pandemic infants. The data showed significantly reduced areas of myelin development (P < .05) in those born after 2019. And the researchers didn’t find significant differences in gestation duration or birth weight.”

The longitudinal characteristics of these studies will let us see whether a change in these individuals’ social circumstances over time also brings to light cognitive changes, even the recovery of lost or underdeveloped cognitive processes, Dr. Volkow concluded.

Dr. Volkow has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNUAL MEETING OF SPANISH SOCIETY OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Alcohol dependence drug the next antianxiety med?

, early research suggests.

Japanese researchers, headed by Akiyoshi Saitoh, PhD, professor in the department of pharmacy, Tokyo University of Science, compared the reactions of mice that received a classic anxiolytic agent (diazepam) to those that received disulfiram while performing a maze task and found comparable reductions in anxiety in both groups of mice.

Moreover, unlike diazepam, disulfiram caused no sedation, amnesia, or impairments in coordination.

“These results indicate that disulfiram can be used safely by elderly patients suffering from anxiety and insomnia and has the potential to become a breakthrough psychotropic drug,” Dr. Saitoh said in a press release.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Inhibitory function

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which is responsible for alcohol metabolism. Recent research suggests that disulfiram may have broader inhibitory functions.

In particular, it inhibits the cytoplasmic protein FROUNT, preventing it from interacting with two chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCRs) that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and are associated with regulating behaviors, including anxiety, in rodents, the authors write.

“Although the functions of FROUNT-chemokines signaling in the immune system are well documented, the potential role of CNS-expressed FROUNT chemokine–related molecules as neuromodulators remains largely unknown,” they write.

The researchers had been conducting preclinical research on the secondary pharmacologic properties of disulfiram and “coincidentally discovered” its “anxiolytic-like effects.” They investigated these effects further because currently used anxiolytics – i.e., benzodiazepines – have unwanted side effects.

The researchers utilized an elevated plus-maze (EPM) test to investigate the effects of disulfiram in mice. The EPM apparatus consists of four arms set in a cross pattern and are connected to a central square. Of these, two arms are protected by vertical boundaries, while the other two have unprotected edges. Typically, mice with anxiety prefer to spend time in the closed arms. The mice also underwent other tests of coordination and the ability to navigate a Y-maze.

Some mice received disulfiram, others received a benzodiazepine, and others received merely a “vehicle,” which served as a control.

Disulfiram “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the time spent in the open arms of the EPM, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at 30 minutes after administration (F [3, 30] = 16.64; P < .0001), suggesting less anxiety. The finding was confirmed by a Bonferroni analysis that showed a significant effect of disulfiram, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.9894; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 3.863; P < .01; 80 mg/kg: t = 6.417; P < .001).

A Student’s t-test analysis showed that diazepam likewise had a significant effect, compared to the vehicle (t = 5.038; P < .001).

Disulfiram also “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the percentage of open-arm entries (F [3, 30] = 14.24; P < .0001). The Bonferroni analysis showed this effect at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.3999; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 2.693; P > .05; 80 mg/kg: t = 5.864; P < .001).

Diazepam similarly showed a significant effect, compared to the vehicle condition (t = 3.733; P < .005).

In particular, the 40 mg/kg dose of disulfiram significantly increased the percentage of time spent in the open arms at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration, with the peak effect occurring at 30 minutes.

The researchers examined the effect of cyanamide, another ALDH inhibitor, on the anxiety behaviors of mice and found no effect on the number of open-arm entries or percentage of time the mice spent in the open arm, compared with the vehicle condition.

In contrast to diazepam, disulfiram had no effect on the amount of spontaneous locomotor activity, time spent on the rotarod, or activity on the Y-maze test displayed by the mice, “suggesting that there were no apparent sedative effects at the dosages used.” Moreover, unlike the mice treated with diazepam, there were no increases in the number of falls the mice experienced on the rotarod.

Glutamate levels in the prelimbic-prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) “play an important role in the development of anxiety-like behavior in mice,” the authors state. Disulfiram “significantly and completely attenuated increased extracellular glutamate levels in the PL-PFC during stress exposure” on the EPM.

“We propose that DSF inhibits FROUNT protein and the chemokine signaling pathways under its influence, which may suppress presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the brain,” said Dr. Saitoh. “This, in turn, attenuates the levels of glutamate in the brain, reducing overall anxiety.”

Humanity’s most common affliction

Commenting for this news organization, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, noted that there is a “renewed interest in psychiatry in excitatory and inhibitory balance – for example, ketamine represents a treatment that facilitates excitatory activity, while neurosteroids are candidate medicines now for inhibitory activity.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study, said it is believed “that the excitatory-inhibitory balance may be relevant to brain health and disease.”

Dr. McIntyre also pointed out that the study “highlights not only the repurposing of a well-known medicine but also exploit[s] the potential brain therapeutic effects of immune targets that indirectly affect inhibitory systems, resulting in potentially a safer treatment for anxiety – the most common affliction of humanity.”

Also commenting for this article, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Teaneck, N.J., called disulfiram “grossly underused for alcohol use disorders and even more so when people use alcohol and cocaine.”

Dr. Raby, who was not involved with the study, has found that patients withdrawing from cocaine, cannabis, or stimulants “can respond very well to disulfiram [not only] in terms of their cravings but also in terms of mood stabilization and anxiolysis.”

He has also found that for patients with bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with depression disulfiram and low-dose lithium “can provide anxiolysis and mood stabilization, especially if a rapid effect is required, usually within a week.”

However, Dr. Raby cautioned that “it is probably not advisable to maintain patients on disulfiram for periods long than 3 months consecutively because there is a risk of neuropathy and hepatopathology that are not common but are seen often enough.” He usually interrupts treatment for a month and then resumes if necessary.

The research was partially supported by the Tsukuba Clinical Research and Development Organization from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors and Dr. Raby have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre reports receiving research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, early research suggests.

Japanese researchers, headed by Akiyoshi Saitoh, PhD, professor in the department of pharmacy, Tokyo University of Science, compared the reactions of mice that received a classic anxiolytic agent (diazepam) to those that received disulfiram while performing a maze task and found comparable reductions in anxiety in both groups of mice.

Moreover, unlike diazepam, disulfiram caused no sedation, amnesia, or impairments in coordination.

“These results indicate that disulfiram can be used safely by elderly patients suffering from anxiety and insomnia and has the potential to become a breakthrough psychotropic drug,” Dr. Saitoh said in a press release.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Inhibitory function

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which is responsible for alcohol metabolism. Recent research suggests that disulfiram may have broader inhibitory functions.

In particular, it inhibits the cytoplasmic protein FROUNT, preventing it from interacting with two chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCRs) that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and are associated with regulating behaviors, including anxiety, in rodents, the authors write.

“Although the functions of FROUNT-chemokines signaling in the immune system are well documented, the potential role of CNS-expressed FROUNT chemokine–related molecules as neuromodulators remains largely unknown,” they write.

The researchers had been conducting preclinical research on the secondary pharmacologic properties of disulfiram and “coincidentally discovered” its “anxiolytic-like effects.” They investigated these effects further because currently used anxiolytics – i.e., benzodiazepines – have unwanted side effects.

The researchers utilized an elevated plus-maze (EPM) test to investigate the effects of disulfiram in mice. The EPM apparatus consists of four arms set in a cross pattern and are connected to a central square. Of these, two arms are protected by vertical boundaries, while the other two have unprotected edges. Typically, mice with anxiety prefer to spend time in the closed arms. The mice also underwent other tests of coordination and the ability to navigate a Y-maze.

Some mice received disulfiram, others received a benzodiazepine, and others received merely a “vehicle,” which served as a control.

Disulfiram “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the time spent in the open arms of the EPM, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at 30 minutes after administration (F [3, 30] = 16.64; P < .0001), suggesting less anxiety. The finding was confirmed by a Bonferroni analysis that showed a significant effect of disulfiram, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.9894; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 3.863; P < .01; 80 mg/kg: t = 6.417; P < .001).

A Student’s t-test analysis showed that diazepam likewise had a significant effect, compared to the vehicle (t = 5.038; P < .001).

Disulfiram also “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the percentage of open-arm entries (F [3, 30] = 14.24; P < .0001). The Bonferroni analysis showed this effect at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.3999; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 2.693; P > .05; 80 mg/kg: t = 5.864; P < .001).

Diazepam similarly showed a significant effect, compared to the vehicle condition (t = 3.733; P < .005).

In particular, the 40 mg/kg dose of disulfiram significantly increased the percentage of time spent in the open arms at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration, with the peak effect occurring at 30 minutes.

The researchers examined the effect of cyanamide, another ALDH inhibitor, on the anxiety behaviors of mice and found no effect on the number of open-arm entries or percentage of time the mice spent in the open arm, compared with the vehicle condition.

In contrast to diazepam, disulfiram had no effect on the amount of spontaneous locomotor activity, time spent on the rotarod, or activity on the Y-maze test displayed by the mice, “suggesting that there were no apparent sedative effects at the dosages used.” Moreover, unlike the mice treated with diazepam, there were no increases in the number of falls the mice experienced on the rotarod.

Glutamate levels in the prelimbic-prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) “play an important role in the development of anxiety-like behavior in mice,” the authors state. Disulfiram “significantly and completely attenuated increased extracellular glutamate levels in the PL-PFC during stress exposure” on the EPM.

“We propose that DSF inhibits FROUNT protein and the chemokine signaling pathways under its influence, which may suppress presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the brain,” said Dr. Saitoh. “This, in turn, attenuates the levels of glutamate in the brain, reducing overall anxiety.”

Humanity’s most common affliction

Commenting for this news organization, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, noted that there is a “renewed interest in psychiatry in excitatory and inhibitory balance – for example, ketamine represents a treatment that facilitates excitatory activity, while neurosteroids are candidate medicines now for inhibitory activity.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study, said it is believed “that the excitatory-inhibitory balance may be relevant to brain health and disease.”

Dr. McIntyre also pointed out that the study “highlights not only the repurposing of a well-known medicine but also exploit[s] the potential brain therapeutic effects of immune targets that indirectly affect inhibitory systems, resulting in potentially a safer treatment for anxiety – the most common affliction of humanity.”

Also commenting for this article, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Teaneck, N.J., called disulfiram “grossly underused for alcohol use disorders and even more so when people use alcohol and cocaine.”

Dr. Raby, who was not involved with the study, has found that patients withdrawing from cocaine, cannabis, or stimulants “can respond very well to disulfiram [not only] in terms of their cravings but also in terms of mood stabilization and anxiolysis.”

He has also found that for patients with bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with depression disulfiram and low-dose lithium “can provide anxiolysis and mood stabilization, especially if a rapid effect is required, usually within a week.”

However, Dr. Raby cautioned that “it is probably not advisable to maintain patients on disulfiram for periods long than 3 months consecutively because there is a risk of neuropathy and hepatopathology that are not common but are seen often enough.” He usually interrupts treatment for a month and then resumes if necessary.

The research was partially supported by the Tsukuba Clinical Research and Development Organization from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors and Dr. Raby have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre reports receiving research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, early research suggests.

Japanese researchers, headed by Akiyoshi Saitoh, PhD, professor in the department of pharmacy, Tokyo University of Science, compared the reactions of mice that received a classic anxiolytic agent (diazepam) to those that received disulfiram while performing a maze task and found comparable reductions in anxiety in both groups of mice.

Moreover, unlike diazepam, disulfiram caused no sedation, amnesia, or impairments in coordination.

“These results indicate that disulfiram can be used safely by elderly patients suffering from anxiety and insomnia and has the potential to become a breakthrough psychotropic drug,” Dr. Saitoh said in a press release.

The study was published online in Frontiers in Pharmacology.

Inhibitory function

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), which is responsible for alcohol metabolism. Recent research suggests that disulfiram may have broader inhibitory functions.

In particular, it inhibits the cytoplasmic protein FROUNT, preventing it from interacting with two chemokine receptors (CCR2 and CCRs) that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and are associated with regulating behaviors, including anxiety, in rodents, the authors write.

“Although the functions of FROUNT-chemokines signaling in the immune system are well documented, the potential role of CNS-expressed FROUNT chemokine–related molecules as neuromodulators remains largely unknown,” they write.

The researchers had been conducting preclinical research on the secondary pharmacologic properties of disulfiram and “coincidentally discovered” its “anxiolytic-like effects.” They investigated these effects further because currently used anxiolytics – i.e., benzodiazepines – have unwanted side effects.

The researchers utilized an elevated plus-maze (EPM) test to investigate the effects of disulfiram in mice. The EPM apparatus consists of four arms set in a cross pattern and are connected to a central square. Of these, two arms are protected by vertical boundaries, while the other two have unprotected edges. Typically, mice with anxiety prefer to spend time in the closed arms. The mice also underwent other tests of coordination and the ability to navigate a Y-maze.

Some mice received disulfiram, others received a benzodiazepine, and others received merely a “vehicle,” which served as a control.

Disulfiram “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the time spent in the open arms of the EPM, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at 30 minutes after administration (F [3, 30] = 16.64; P < .0001), suggesting less anxiety. The finding was confirmed by a Bonferroni analysis that showed a significant effect of disulfiram, compared with the vehicle-treated group, at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.9894; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 3.863; P < .01; 80 mg/kg: t = 6.417; P < .001).

A Student’s t-test analysis showed that diazepam likewise had a significant effect, compared to the vehicle (t = 5.038; P < .001).

Disulfiram also “significantly and dose-dependently” increased the percentage of open-arm entries (F [3, 30] = 14.24; P < .0001). The Bonferroni analysis showed this effect at all three doses (20 mg/kg: t = 0.3999; P > .05; 40 mg/kg: t = 2.693; P > .05; 80 mg/kg: t = 5.864; P < .001).

Diazepam similarly showed a significant effect, compared to the vehicle condition (t = 3.733; P < .005).

In particular, the 40 mg/kg dose of disulfiram significantly increased the percentage of time spent in the open arms at 15, 30, and 60 minutes after administration, with the peak effect occurring at 30 minutes.

The researchers examined the effect of cyanamide, another ALDH inhibitor, on the anxiety behaviors of mice and found no effect on the number of open-arm entries or percentage of time the mice spent in the open arm, compared with the vehicle condition.

In contrast to diazepam, disulfiram had no effect on the amount of spontaneous locomotor activity, time spent on the rotarod, or activity on the Y-maze test displayed by the mice, “suggesting that there were no apparent sedative effects at the dosages used.” Moreover, unlike the mice treated with diazepam, there were no increases in the number of falls the mice experienced on the rotarod.

Glutamate levels in the prelimbic-prefrontal cortex (PL-PFC) “play an important role in the development of anxiety-like behavior in mice,” the authors state. Disulfiram “significantly and completely attenuated increased extracellular glutamate levels in the PL-PFC during stress exposure” on the EPM.

“We propose that DSF inhibits FROUNT protein and the chemokine signaling pathways under its influence, which may suppress presynaptic glutamatergic transmission in the brain,” said Dr. Saitoh. “This, in turn, attenuates the levels of glutamate in the brain, reducing overall anxiety.”

Humanity’s most common affliction

Commenting for this news organization, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, noted that there is a “renewed interest in psychiatry in excitatory and inhibitory balance – for example, ketamine represents a treatment that facilitates excitatory activity, while neurosteroids are candidate medicines now for inhibitory activity.”

Dr. McIntyre, who is the chairman and executive director of the Brain and Cognitive Discover Foundation, Toronto, and was not involved with the study, said it is believed “that the excitatory-inhibitory balance may be relevant to brain health and disease.”

Dr. McIntyre also pointed out that the study “highlights not only the repurposing of a well-known medicine but also exploit[s] the potential brain therapeutic effects of immune targets that indirectly affect inhibitory systems, resulting in potentially a safer treatment for anxiety – the most common affliction of humanity.”

Also commenting for this article, Wilfrid Noel Raby, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Teaneck, N.J., called disulfiram “grossly underused for alcohol use disorders and even more so when people use alcohol and cocaine.”

Dr. Raby, who was not involved with the study, has found that patients withdrawing from cocaine, cannabis, or stimulants “can respond very well to disulfiram [not only] in terms of their cravings but also in terms of mood stabilization and anxiolysis.”

He has also found that for patients with bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with depression disulfiram and low-dose lithium “can provide anxiolysis and mood stabilization, especially if a rapid effect is required, usually within a week.”

However, Dr. Raby cautioned that “it is probably not advisable to maintain patients on disulfiram for periods long than 3 months consecutively because there is a risk of neuropathy and hepatopathology that are not common but are seen often enough.” He usually interrupts treatment for a month and then resumes if necessary.

The research was partially supported by the Tsukuba Clinical Research and Development Organization from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. The authors and Dr. Raby have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre reports receiving research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Axsome, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, and Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is CEO of Braxia Scientific.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FRONTIERS IN PHARMACOLOGY

Mental illness tied to COVID-19 breakthrough infection

“Psychiatric disorders remained significantly associated with incident breakthrough infections above and beyond sociodemographic and medical factors, suggesting that mental health is important to consider in conjunction with other risk factors,” wrote the investigators, led by Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, University of California, San Francisco.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders “should be prioritized for booster vaccinations and other critical preventive efforts, including increased SARS-CoV-2 screening, public health campaigns, or COVID-19 discussions during clinical care,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Elderly most vulnerable

The researchers reviewed the records of 263,697 veterans who were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Just over a half (51.4%) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses within the last 5 years and 14.8% developed breakthrough COVID-19 infections, confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Psychiatric diagnoses among the veterans included depression, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, ADHD, dissociation, and eating disorders.

In the overall sample, a history of any psychiatric disorder was associated with a 7% higher incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 infection in models adjusted for potential confounders (adjusted relative risk, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.09) and a 3% higher incidence in models additionally adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities and smoking (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05).

Most psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher incidence of breakthrough infection, with the highest relative risk observed for substance use disorders (aRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12 -1.21) and adjustment disorder (aRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10-1.16) in fully adjusted models.

Older vaccinated veterans with psychiatric illnesses appear to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 reinfection.

In veterans aged 65 and older, all psychiatric disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection, with increases in the incidence rate ranging from 3% to 24% in fully adjusted models.

In the younger veterans, in contrast, only anxiety, adjustment, and substance use disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection in fully adjusted models.

Psychotic disorders were associated with a 10% lower incidence of breakthrough infection among younger veterans, perhaps because of greater social isolation, the researchers said.

Risky behavior or impaired immunity?

“Although some of the larger observed effect sizes are compelling at an individual level, even the relatively modest effect sizes may have a large effect at the population level when considering the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the global reach and scale of the pandemic,” Dr. O’Donovan and colleagues wrote.

They noted that psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, have been associated with impaired cellular immunity and blunted response to vaccines. Therefore, it’s possible that those with psychiatric disorders have poorer responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

It’s also possible that immunity following vaccination wanes more quickly or more strongly in people with psychiatric disorders and they could have less protection against new variants, they added.

Patients with psychiatric disorders could be more apt to engage in risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19, which could also increase the risk for breakthrough infection, they said.

The study was supported by a UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award. Dr. O’Donovan reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Psychiatric disorders remained significantly associated with incident breakthrough infections above and beyond sociodemographic and medical factors, suggesting that mental health is important to consider in conjunction with other risk factors,” wrote the investigators, led by Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, University of California, San Francisco.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders “should be prioritized for booster vaccinations and other critical preventive efforts, including increased SARS-CoV-2 screening, public health campaigns, or COVID-19 discussions during clinical care,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Elderly most vulnerable

The researchers reviewed the records of 263,697 veterans who were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Just over a half (51.4%) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses within the last 5 years and 14.8% developed breakthrough COVID-19 infections, confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Psychiatric diagnoses among the veterans included depression, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, ADHD, dissociation, and eating disorders.

In the overall sample, a history of any psychiatric disorder was associated with a 7% higher incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 infection in models adjusted for potential confounders (adjusted relative risk, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.09) and a 3% higher incidence in models additionally adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities and smoking (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05).

Most psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher incidence of breakthrough infection, with the highest relative risk observed for substance use disorders (aRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12 -1.21) and adjustment disorder (aRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10-1.16) in fully adjusted models.

Older vaccinated veterans with psychiatric illnesses appear to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 reinfection.

In veterans aged 65 and older, all psychiatric disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection, with increases in the incidence rate ranging from 3% to 24% in fully adjusted models.

In the younger veterans, in contrast, only anxiety, adjustment, and substance use disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection in fully adjusted models.

Psychotic disorders were associated with a 10% lower incidence of breakthrough infection among younger veterans, perhaps because of greater social isolation, the researchers said.

Risky behavior or impaired immunity?

“Although some of the larger observed effect sizes are compelling at an individual level, even the relatively modest effect sizes may have a large effect at the population level when considering the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the global reach and scale of the pandemic,” Dr. O’Donovan and colleagues wrote.

They noted that psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, have been associated with impaired cellular immunity and blunted response to vaccines. Therefore, it’s possible that those with psychiatric disorders have poorer responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

It’s also possible that immunity following vaccination wanes more quickly or more strongly in people with psychiatric disorders and they could have less protection against new variants, they added.

Patients with psychiatric disorders could be more apt to engage in risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19, which could also increase the risk for breakthrough infection, they said.

The study was supported by a UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award. Dr. O’Donovan reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Psychiatric disorders remained significantly associated with incident breakthrough infections above and beyond sociodemographic and medical factors, suggesting that mental health is important to consider in conjunction with other risk factors,” wrote the investigators, led by Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, University of California, San Francisco.

Individuals with psychiatric disorders “should be prioritized for booster vaccinations and other critical preventive efforts, including increased SARS-CoV-2 screening, public health campaigns, or COVID-19 discussions during clinical care,” they added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Elderly most vulnerable

The researchers reviewed the records of 263,697 veterans who were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

Just over a half (51.4%) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses within the last 5 years and 14.8% developed breakthrough COVID-19 infections, confirmed by a positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Psychiatric diagnoses among the veterans included depression, posttraumatic stress, anxiety, adjustment disorder, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, ADHD, dissociation, and eating disorders.

In the overall sample, a history of any psychiatric disorder was associated with a 7% higher incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 infection in models adjusted for potential confounders (adjusted relative risk, 1.07; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.09) and a 3% higher incidence in models additionally adjusted for underlying medical comorbidities and smoking (aRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01-1.05).

Most psychiatric disorders were associated with a higher incidence of breakthrough infection, with the highest relative risk observed for substance use disorders (aRR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.12 -1.21) and adjustment disorder (aRR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.10-1.16) in fully adjusted models.

Older vaccinated veterans with psychiatric illnesses appear to be most vulnerable to COVID-19 reinfection.

In veterans aged 65 and older, all psychiatric disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection, with increases in the incidence rate ranging from 3% to 24% in fully adjusted models.

In the younger veterans, in contrast, only anxiety, adjustment, and substance use disorders were associated with an increased incidence of breakthrough infection in fully adjusted models.

Psychotic disorders were associated with a 10% lower incidence of breakthrough infection among younger veterans, perhaps because of greater social isolation, the researchers said.

Risky behavior or impaired immunity?

“Although some of the larger observed effect sizes are compelling at an individual level, even the relatively modest effect sizes may have a large effect at the population level when considering the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders and the global reach and scale of the pandemic,” Dr. O’Donovan and colleagues wrote.

They noted that psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorders, have been associated with impaired cellular immunity and blunted response to vaccines. Therefore, it’s possible that those with psychiatric disorders have poorer responses to COVID-19 vaccination.

It’s also possible that immunity following vaccination wanes more quickly or more strongly in people with psychiatric disorders and they could have less protection against new variants, they added.

Patients with psychiatric disorders could be more apt to engage in risky behaviors for contracting COVID-19, which could also increase the risk for breakthrough infection, they said.

The study was supported by a UCSF Department of Psychiatry Rapid Award and UCSF Faculty Resource Fund Award. Dr. O’Donovan reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

52-year-old man • hematemesis • history of cirrhosis • persistent fevers • Dx?

THE CASE

A 52-year-old man presented to the emergency department after vomiting a large volume of blood and was admitted to the intensive care unit. His past medical history was remarkable for untreated chronic hepatitis C resulting from injection drug use and cirrhosis without prior history of esophageal varices.

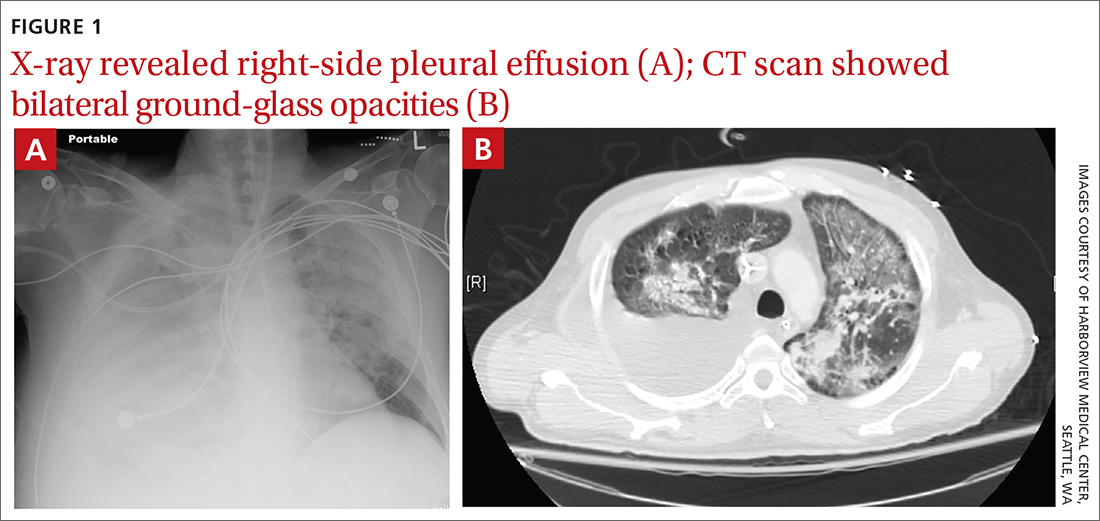

Due to ongoing hematemesis, he was intubated for airway protection and underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with banding of large esophageal varices on hospital day (HD) 1. He was extubated on HD 2 after clinical stability was achieved; however, he became encephalopathic over the subsequent days despite treatment with lactulose. On HD 4, the patient required re-intubation for progressive respiratory failure. Chest imaging revealed a large, simple-appearing right pleural effusion and extensive bilateral patchy ground-glass opacities (FIGURE 1).