User login

Is anxiety about the coronavirus out of proportion?

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

A number of years ago, a patient I was treating mentioned that she was not eating tomatoes. There had been stories in the news about people contracting bacterial infections from tomatoes, but I paused for a moment, then asked her: “Have there been any contaminated tomatoes here in Maryland?” There had not been and I was still happily eating salsa, but my patient thought about this differently: If disease-causing tomatoes were to come to our state, someone would be the first person to become ill. She did not want to take any risks. My patient, however, was a heavy smoker and already grappling with health issues that were caused by smoking, so I found her choice of what she should worry about and how it influenced her behavior to be perplexing. I realize it’s not the same; nicotine is an addiction, while tomatoes remain a choice for most of us, and it’s common for people to worry about very unlikely events even when we are surrounded by very real and statistically more probable threats to our well-being.

Today’s news reports are filled with stories about 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), an illness that started in Wuhan, China; as of Jan. 31, 2020, there were 9,776 confirmed cases and 213 deaths. There have been an additional 118 cases reported outside of mainland China, including 6 in the United States, and no one outside of China has died.

The response to the virus has been remarkable: Wuhan, a city of more than 11 million inhabitants, is on lockdown, as are 15 other cities in China; 46 million people have been affected, the largest quarantine in human history. Travel is restricted in parts of China, airports all over the world are screening those who fly in from Wuhan, foreign governments are bringing their citizens home from Wuhan, and even Starbucks has temporarily closed half its stores in China. The economics of containing this virus are astounding.

In the meantime, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that, as of the week of Jan. 25, there have been 19 million cases of the flu in the United States. Of those stricken, 180,000 people have been hospitalized and 10,000 have died, including 68 pediatric patients. No cities are on lockdown, public transportation runs as usual, airports don’t screen passengers for flu symptoms, and Starbucks continues to serve vanilla lattes to any willing customer. Anxiety about illness is not new; we’ve seen it with SARS, Ebola, measles, and even around Chipotle’s food poisoning cases – to name just a few recent scares. We have also seen a lot of media on vaping-related deaths, and as of early January 2020, vaping-related illnesses affected 2,602 people with 59 deaths. It has been a topic of discussion among legislators, with an emphasis on either outlawing the flavoring that might appeal to younger people or simply outlawing e-cigarettes. No one, however, is talking about outlawing regular cigarettes, despite the fact that many people have switched from cigarettes to vaping products as a way to quit smoking. So, while vaping has caused 59 deaths since 2018, cigarettes are responsible for 480,000 fatalities a year in the United States and smokers live, on average, 10 years less than nonsmokers.

So what fuels anxiety about the latest health scare, and why aren’t we more anxious about the more common causes of premature mortality? Certainly, the newness and the unknown are factors in the coronavirus scare. It’s not certain how this illness was introduced into the human population, although one theory is that it started with the consumption of bats who carry the virus. It’s spreading fast, and in some people, it has been lethal. The incubation period is not known, or whether it is contagious before symptoms appear. Coronavirus is getting a lot of public health attention and the World Health Organization just announced that the virus is a public health emergency of international concern. On the televised news on Jan. 29, 2020, coronavirus was the top story in the United States, even though an impeachment trial is in progress for our country’s president.

The public health response of locking down cities may help contain the outbreak and prevent a global epidemic, although millions of people had already left Wuhan, so the heavy-handed attempt to prevent spread of the virus may well be too late. In the case of the Ebola virus – a much more lethal disease that was also thought to be introduced by bats – public health measures certainly curtailed global spread, and the epidemic of 2014-2016 was limited to 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths, nearly all of them in West Africa.

Most of the things that cause people to die are not new and are not topics the media chooses to sensationalize. Dissemination of news has changed over the decades, with so much more of it, instant reports on social media, and competition for viewers that leads journalists to pull at our emotions. And while we may, or may not, get flu shots and avoid those who have the flu, how and where we position both our anxiety and our resources does not always make sense. Certainly some people are predisposed to worry about both common and uncommon dangers, while others seem never to worry and engage in acts that many of us would consider dangerous. If we are looking for logic, it may be hard to find – there are those who would happily go bungee jumping but wouldn’t dream of leaving the house out without hand sanitizer.

The repercussions from this massive response to the Wuhan coronavirus are significant. For the millions of people on lockdown in China, each day gets emotionally harder; some may begin to have issues procuring food, and the financial losses for the economy will be significant. It’s not really possible to know yet if this response is warranted; we do know that infectious diseases can kill millions. The AIDS pandemic has taken the lives of 36 million people since 1981, and the influenza pandemic of 1918 resulted in an estimated 20 million to 50 million deaths after infecting 500 million people. Still, one might wonder if other, more mundane causes of morbidity and mortality – the ones that no longer garner our dread or make it to the front pages – might also be worthy of more hype and resources.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Half of SLE patients have incident neuropsychiatric events

Neuropsychiatric events occurred in just over half of all patients recently diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus and followed for an average of nearly 8 years in an international study of more than 1,800 patients.

Up to 30% of these neuropsychiatric (NP) events in up to 20% of the followed cohort were directly attributable to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a representative patient population, wrote John G. Hanly, MD, and associates in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Their findings were consistent with prior reports, they added.

Another notable finding from follow-up of these 1,827 SLE patients was that among those without a history of SLE-related NP events at baseline, 74% remained free of NP events during the subsequent 10 years, wrote Dr. Hanly, professor of medicine and director of the lupus clinic at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and coauthors. Among patients free from SLE-associated NP events after 2 years, 84% remained event free during their remaining follow-up. SLE patients with a history of an NP event that subsequently resolved had a 72% rate of freedom from another NP event during 10 years of follow-up.

These findings came from patients recently diagnosed with SLE (within the preceding 15 months) and enrolled at any of 31 participating academic medical centers in North America, Europe, and Asia. The investigators considered preenrollment NP events to include those starting from 6 months prior to diagnosis of SLE until the time patients entered the study. They used case definitions for 19 SLE-associated NP events published by the American College of Rheumatology (Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Apr;42[4]:599-608). All enrolled patients underwent annual assessment for NP events, with follow-up continuing as long as 18 years.

The researchers identified NP events in 955 of the 1,827 enrolled patients, a 52% incidence, including 1,910 unique NP events that included episodes from each of the 19 NP event types, with 92% involving the central nervous system and 8% involving the peripheral nervous system. The percentage of NP events attributable to SLE ranged from 17% to 31%, and they occurred in 14%-21% of the studied patients, with the range reflecting various attribution models used in the analyses. Some patients remained in the same NP state, while others progressed through more than one state.

The study did not receive commercial funding. Dr. Hanly had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Hanly JG et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216150.

Neuropsychiatric events occurred in just over half of all patients recently diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus and followed for an average of nearly 8 years in an international study of more than 1,800 patients.

Up to 30% of these neuropsychiatric (NP) events in up to 20% of the followed cohort were directly attributable to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a representative patient population, wrote John G. Hanly, MD, and associates in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Their findings were consistent with prior reports, they added.

Another notable finding from follow-up of these 1,827 SLE patients was that among those without a history of SLE-related NP events at baseline, 74% remained free of NP events during the subsequent 10 years, wrote Dr. Hanly, professor of medicine and director of the lupus clinic at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and coauthors. Among patients free from SLE-associated NP events after 2 years, 84% remained event free during their remaining follow-up. SLE patients with a history of an NP event that subsequently resolved had a 72% rate of freedom from another NP event during 10 years of follow-up.

These findings came from patients recently diagnosed with SLE (within the preceding 15 months) and enrolled at any of 31 participating academic medical centers in North America, Europe, and Asia. The investigators considered preenrollment NP events to include those starting from 6 months prior to diagnosis of SLE until the time patients entered the study. They used case definitions for 19 SLE-associated NP events published by the American College of Rheumatology (Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Apr;42[4]:599-608). All enrolled patients underwent annual assessment for NP events, with follow-up continuing as long as 18 years.

The researchers identified NP events in 955 of the 1,827 enrolled patients, a 52% incidence, including 1,910 unique NP events that included episodes from each of the 19 NP event types, with 92% involving the central nervous system and 8% involving the peripheral nervous system. The percentage of NP events attributable to SLE ranged from 17% to 31%, and they occurred in 14%-21% of the studied patients, with the range reflecting various attribution models used in the analyses. Some patients remained in the same NP state, while others progressed through more than one state.

The study did not receive commercial funding. Dr. Hanly had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Hanly JG et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216150.

Neuropsychiatric events occurred in just over half of all patients recently diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus and followed for an average of nearly 8 years in an international study of more than 1,800 patients.

Up to 30% of these neuropsychiatric (NP) events in up to 20% of the followed cohort were directly attributable to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in a representative patient population, wrote John G. Hanly, MD, and associates in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. Their findings were consistent with prior reports, they added.

Another notable finding from follow-up of these 1,827 SLE patients was that among those without a history of SLE-related NP events at baseline, 74% remained free of NP events during the subsequent 10 years, wrote Dr. Hanly, professor of medicine and director of the lupus clinic at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and coauthors. Among patients free from SLE-associated NP events after 2 years, 84% remained event free during their remaining follow-up. SLE patients with a history of an NP event that subsequently resolved had a 72% rate of freedom from another NP event during 10 years of follow-up.

These findings came from patients recently diagnosed with SLE (within the preceding 15 months) and enrolled at any of 31 participating academic medical centers in North America, Europe, and Asia. The investigators considered preenrollment NP events to include those starting from 6 months prior to diagnosis of SLE until the time patients entered the study. They used case definitions for 19 SLE-associated NP events published by the American College of Rheumatology (Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Apr;42[4]:599-608). All enrolled patients underwent annual assessment for NP events, with follow-up continuing as long as 18 years.

The researchers identified NP events in 955 of the 1,827 enrolled patients, a 52% incidence, including 1,910 unique NP events that included episodes from each of the 19 NP event types, with 92% involving the central nervous system and 8% involving the peripheral nervous system. The percentage of NP events attributable to SLE ranged from 17% to 31%, and they occurred in 14%-21% of the studied patients, with the range reflecting various attribution models used in the analyses. Some patients remained in the same NP state, while others progressed through more than one state.

The study did not receive commercial funding. Dr. Hanly had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Hanly JG et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jan 8. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216150.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Book review: New understanding offered of personality development

Rarely does someone come along who has new insight into behavior, someone who conceptualizes with such clarity that we wonder why we never saw it before.

Homer B. Martin, MD, was such a man. Over the course of 40 years’ psychodynamic psychotherapy work as a psychiatrist, he pieced together a concept of how we are emotionally conditioned in the first 3 years of life and how this conditioning affects us throughout our lives. Conditioning forces us to live on autopilot, creating inappropriate knee-jerk emotional responses to those closest to us.

Dr. Martin’s protégé, child and adolescent psychiatrist Christine B.L. Adams, MD, contributed her own 40 years of clinical practice as a psychodynamic psychotherapist to Dr. Martin’s new concept of emotional conditioning. Their findings are published in the award-winning book “Living on Automatic: How Emotional Conditioning Shapes our Lives and Relationships” (Praeger, 2018).

The authors aim to help both therapists and patients out of the quagmire of conflicted relationships and emotional illnesses that result from emotional conditioning. They propose a new understanding of personality development and subsequent relationship conflict, which incorporates work of Pavlov, Skinner, and Lorenz, along with techniques of Freud.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams discovered that we are conditioned into one of two roles – omnipotent and impotent. Those roles become the bedrock of our personalities. We display those roles in marriages, with our children, friends, and colleagues, without regard to gender.

Each role exists on a continuum, from mild to severe, determined by upbringing in the family. Once you acquire a role in childhood, the role is reinforced by both family and society at large – peers, teachers, and friends.

The authors unveil a new conceptualization of how the mind works for each role – thinking style, ways of elaborating emotions, attitudes, personal standards, value systems, reality testing mode, quality of thought, and mode of commitment.

The book has three sections. “Part One, Understanding Emotional Conditioning” describes the basic concepts, the effects of conditioning, and the two personality types. “Part Two, Relationship Struggles: Miscommunications and Marriages” examines marriage conflict, divorce, and living single. “Part Three, Solutions: Psychotherapy and Deconditioning” presents steps we can take to decondition ourselves, as well as the process of deconditioning psychotherapy.

To escape automatic living, Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams endorse the use of deconditioning psychotherapy, which helps people lessen their emotional conditioning. The cornerstone of deconditioning treatment is helping people turn off automatic responses through replacing emotional conditioning with thinking.

In undergoing deconditioning you discover how you were emotionally conditioned as a child and how you skew participation in your relationships. You learn to slow down and dissect the automatic responding that you and others do. You discover how to evaluate what the situation calls for with the involved people. Who needs what, how much, and from whom?

This book is written for both general readers and psychotherapists. Its novel approach for alleviating emotional illnesses in “ordinary” people is a welcome addition to the armamentarium of any therapist.

The book is extraordinarily well written. It offers valuable case vignettes, tables, and self-inquiry questions to assist in understanding the characteristics associated with each emotionally conditioned role.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams have made the book very digestible, intriguing and practical. And it is a marvelous tribute to the value of a 30-year mentorship.

Judith R. Milner, MD, MEd, SpecEd, is a general, child, and adolescent psychiatrist in private practice in Everett, Wash. She has traveled with various groups over the years in an effort to alleviate some of the suffering caused by war and natural disaster. She has worked with Step Up Rwanda Women and Pygmy Survival Alliance, as well as on the Committee for Women at the American Psychiatric Association and the Consumer Issues Committee, the Committee on Diversity and Culture, and the Membership Committee for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Rarely does someone come along who has new insight into behavior, someone who conceptualizes with such clarity that we wonder why we never saw it before.

Homer B. Martin, MD, was such a man. Over the course of 40 years’ psychodynamic psychotherapy work as a psychiatrist, he pieced together a concept of how we are emotionally conditioned in the first 3 years of life and how this conditioning affects us throughout our lives. Conditioning forces us to live on autopilot, creating inappropriate knee-jerk emotional responses to those closest to us.

Dr. Martin’s protégé, child and adolescent psychiatrist Christine B.L. Adams, MD, contributed her own 40 years of clinical practice as a psychodynamic psychotherapist to Dr. Martin’s new concept of emotional conditioning. Their findings are published in the award-winning book “Living on Automatic: How Emotional Conditioning Shapes our Lives and Relationships” (Praeger, 2018).

The authors aim to help both therapists and patients out of the quagmire of conflicted relationships and emotional illnesses that result from emotional conditioning. They propose a new understanding of personality development and subsequent relationship conflict, which incorporates work of Pavlov, Skinner, and Lorenz, along with techniques of Freud.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams discovered that we are conditioned into one of two roles – omnipotent and impotent. Those roles become the bedrock of our personalities. We display those roles in marriages, with our children, friends, and colleagues, without regard to gender.

Each role exists on a continuum, from mild to severe, determined by upbringing in the family. Once you acquire a role in childhood, the role is reinforced by both family and society at large – peers, teachers, and friends.

The authors unveil a new conceptualization of how the mind works for each role – thinking style, ways of elaborating emotions, attitudes, personal standards, value systems, reality testing mode, quality of thought, and mode of commitment.

The book has three sections. “Part One, Understanding Emotional Conditioning” describes the basic concepts, the effects of conditioning, and the two personality types. “Part Two, Relationship Struggles: Miscommunications and Marriages” examines marriage conflict, divorce, and living single. “Part Three, Solutions: Psychotherapy and Deconditioning” presents steps we can take to decondition ourselves, as well as the process of deconditioning psychotherapy.

To escape automatic living, Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams endorse the use of deconditioning psychotherapy, which helps people lessen their emotional conditioning. The cornerstone of deconditioning treatment is helping people turn off automatic responses through replacing emotional conditioning with thinking.

In undergoing deconditioning you discover how you were emotionally conditioned as a child and how you skew participation in your relationships. You learn to slow down and dissect the automatic responding that you and others do. You discover how to evaluate what the situation calls for with the involved people. Who needs what, how much, and from whom?

This book is written for both general readers and psychotherapists. Its novel approach for alleviating emotional illnesses in “ordinary” people is a welcome addition to the armamentarium of any therapist.

The book is extraordinarily well written. It offers valuable case vignettes, tables, and self-inquiry questions to assist in understanding the characteristics associated with each emotionally conditioned role.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams have made the book very digestible, intriguing and practical. And it is a marvelous tribute to the value of a 30-year mentorship.

Judith R. Milner, MD, MEd, SpecEd, is a general, child, and adolescent psychiatrist in private practice in Everett, Wash. She has traveled with various groups over the years in an effort to alleviate some of the suffering caused by war and natural disaster. She has worked with Step Up Rwanda Women and Pygmy Survival Alliance, as well as on the Committee for Women at the American Psychiatric Association and the Consumer Issues Committee, the Committee on Diversity and Culture, and the Membership Committee for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Rarely does someone come along who has new insight into behavior, someone who conceptualizes with such clarity that we wonder why we never saw it before.

Homer B. Martin, MD, was such a man. Over the course of 40 years’ psychodynamic psychotherapy work as a psychiatrist, he pieced together a concept of how we are emotionally conditioned in the first 3 years of life and how this conditioning affects us throughout our lives. Conditioning forces us to live on autopilot, creating inappropriate knee-jerk emotional responses to those closest to us.

Dr. Martin’s protégé, child and adolescent psychiatrist Christine B.L. Adams, MD, contributed her own 40 years of clinical practice as a psychodynamic psychotherapist to Dr. Martin’s new concept of emotional conditioning. Their findings are published in the award-winning book “Living on Automatic: How Emotional Conditioning Shapes our Lives and Relationships” (Praeger, 2018).

The authors aim to help both therapists and patients out of the quagmire of conflicted relationships and emotional illnesses that result from emotional conditioning. They propose a new understanding of personality development and subsequent relationship conflict, which incorporates work of Pavlov, Skinner, and Lorenz, along with techniques of Freud.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams discovered that we are conditioned into one of two roles – omnipotent and impotent. Those roles become the bedrock of our personalities. We display those roles in marriages, with our children, friends, and colleagues, without regard to gender.

Each role exists on a continuum, from mild to severe, determined by upbringing in the family. Once you acquire a role in childhood, the role is reinforced by both family and society at large – peers, teachers, and friends.

The authors unveil a new conceptualization of how the mind works for each role – thinking style, ways of elaborating emotions, attitudes, personal standards, value systems, reality testing mode, quality of thought, and mode of commitment.

The book has three sections. “Part One, Understanding Emotional Conditioning” describes the basic concepts, the effects of conditioning, and the two personality types. “Part Two, Relationship Struggles: Miscommunications and Marriages” examines marriage conflict, divorce, and living single. “Part Three, Solutions: Psychotherapy and Deconditioning” presents steps we can take to decondition ourselves, as well as the process of deconditioning psychotherapy.

To escape automatic living, Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams endorse the use of deconditioning psychotherapy, which helps people lessen their emotional conditioning. The cornerstone of deconditioning treatment is helping people turn off automatic responses through replacing emotional conditioning with thinking.

In undergoing deconditioning you discover how you were emotionally conditioned as a child and how you skew participation in your relationships. You learn to slow down and dissect the automatic responding that you and others do. You discover how to evaluate what the situation calls for with the involved people. Who needs what, how much, and from whom?

This book is written for both general readers and psychotherapists. Its novel approach for alleviating emotional illnesses in “ordinary” people is a welcome addition to the armamentarium of any therapist.

The book is extraordinarily well written. It offers valuable case vignettes, tables, and self-inquiry questions to assist in understanding the characteristics associated with each emotionally conditioned role.

Dr. Martin and Dr. Adams have made the book very digestible, intriguing and practical. And it is a marvelous tribute to the value of a 30-year mentorship.

Judith R. Milner, MD, MEd, SpecEd, is a general, child, and adolescent psychiatrist in private practice in Everett, Wash. She has traveled with various groups over the years in an effort to alleviate some of the suffering caused by war and natural disaster. She has worked with Step Up Rwanda Women and Pygmy Survival Alliance, as well as on the Committee for Women at the American Psychiatric Association and the Consumer Issues Committee, the Committee on Diversity and Culture, and the Membership Committee for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Buspirone: A forgotten friend

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

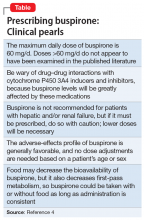

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

In general, when a medication goes off patent, marketing for it significantly slows down or comes to a halt. Studies have shown that physicians’ prescribing habits are influenced by pharmaceutical representatives and companies.1 This phenomenon may have an unforeseen adverse effect: once an effective and inexpensive medication “goes generic,” its use may fall out of favor. Additionally, physicians may have concerns about prescribing generic medications, such as perceiving them as less effective and conferring more adverse effects compared with brand-name formulations.2 One such generic medication is buspirone, which originally was branded as BuSpar.

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diagnoses, and at times are the most challenging to treat.3 Anecdotally, we often see benzodiazepines prescribed as first-line monotherapy for acute and chronic anxiety, but because these agents can cause physical dependence and a withdrawal reaction, alternative anxiolytic medications should be strongly considered. Despite its age, buspirone still plays a role in the treatment of anxiety, and its off-label use can also be useful in certain populations and scenarios. In this article, we delve into buspirone’s mechanism of action, discuss its advantages and challenges, and what you need to know when prescribing it.

How buspirone works

Buspirone was originally described as an anxiolytic agent that was pharmacologically unrelated to traditional anxiety-reducing medications (ie, benzodiazepines and barbiturates).4

The antidepressants vortioxetine and vilazodone exhibit dual-action at both serotonin reuptake transporters and 5HT1A receptors; thus, they work like an SSRI and buspirone combined.6 Although some patients may find it more convenient to take a dual-action pill over 2 separate ones, some insurance companies do not cover these newer agents. Additionally, prescribing buspirone separately allows for more precise dosing, which may lower the risk of adverse effects.

Buspirone is a major substrate for cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and a minor for CYP2D6, so caution must be advised if considering buspirone for a patient receiving any CYP3A4 inducers and/or inhibitors,7 including grapefruit juice.8

Dose adjustments are not necessary for age and sex, which allows for highly consistent dosing.4 However, as with prescribing medications in any geriatric population, lower starting doses and slower titration of buspirone may be necessary to avoid potential adverse effects due to the alterations of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic processes that occur as patients age.9

Advantages of buspirone

Works well as an add-on to other medications. While buspirone in adequate doses may be helpful as monotherapy in GAD, it can also be helpful in other, more complex psychiatric scenarios. Sumiyoshi et al10 observed improvement in scores on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test when buspirone was added to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), which suggests buspirone may help improve attention in patients with schizophrenia. It has been postulated that buspirone may also be helpful for cognitive dysfunction in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.11 Buspirone has been used to treat comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorder, resulting in reduced anxiety, longer latency to relapse, and fewer drinking days during a 12-week treatment program.12 Buspirone has been more effective than placebo for treating post-stroke anxiety.13

Continue to: Patients who receive...

Patients who receive an SSRI, such as citalopram, but are not able to achieve a substantial improvement in their depressive and/or anxious symptoms may benefit from the addition of buspirone to their treatment regimen.14,15

A favorable adverse-effect profile. There are no absolute contraindications to buspirone except a history of hypersensitivity.4 Buspirone generally is well tolerated and carries a low risk of adverse effects. The most common adverse effects are dizziness and nausea.6 Buspirone is not sedating.

Potentially safe for patients who are pregnant. Unlike many other first-line agents for anxiety, such as SSRIs, buspirone has an FDA Category B classification, meaning animal studies have shown no adverse events during pregnancy.4 The FDA Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule applies only to medications that entered the market on or after June 30, 2001; unfortunately, buspirone is excluded from this updated categorization.16 As with any medication being considered for pregnant or lactating women, the prescriber and patient must weigh the benefits vs the risks to determine if buspirone is appropriate for any individual patient.

No adverse events have been reported from abrupt discontinuation of buspirone.17

Inexpensive. Buspirone is generic and extremely inexpensive. According to GoodRx.com, a 30-day supply of 5-mg tablets for twice-daily dosing can cost $4.18 A maximum daily dose (prescribed as 2 pills, 15 mg twice daily) may cost approximately $18/month.18 Thus, buspirone is a good option for uninsured or underinsured patients, for whom this would be more affordable than other anxiolytic medications.

Continue to: May offset certain adverse effects

May offset certain adverse effects. Sexual dysfunction is a common adverse effect of SSRIs. One strategy to offset this phenomenon is to add bupropion. However, in a randomized controlled trial, Landén et al19 found that sexual adverse effects induced by SSRIs were greatly mitigated by adding buspirone, even within the first week of treatment. This improvement was more marked in women than in men, which is helpful because sexual dysfunction in women is generally resistant to other interventions.20 Unlike

Unlikely to cause extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Because of its central D2 antagonism, buspirone has a low potential (<1%) to produce EPS. Buspirone has even been shown to reverse

The Table4 highlights key points to bear in mind when prescribing buspirone.

Challenges with buspirone

Response is not immediate. Unlike benzodiazepines, buspirone does not have an immediate onset of action.22 With buspirone monotherapy, response may be seen in approximately 2 to 4 weeks.23 Therefore, patients transitioning from a quick-onset benzodiazepine to buspirone may not report a good response. However, as noted above, when using buspirone to treat SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction, response may emerge within 1 week.19 Buspirone also lacks the euphoric and sedative qualities of benzodiazepines that patients may prefer.

Not for patients with hepatic and renal impairment. Because plasma levels of buspirone are elevated in patients with hepatic and renal impairment, this medication is not ideal for use in these populations.4

Continue to: Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs

Contraindicated in patients receiving MAOIs. Buspirone should not be prescribed to patients with depression who are receiving treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) because the combination may precipitate a hypertensive reaction.4 A minimum washout period of 14 days from the MAOI is necessary before initiating buspirone.9

Idiosyncratic adverse effects. As with all pharmaceuticals, buspirone may produce idiosyncratic adverse effects. Faber and Sansone24 reported a case of a woman who experienced hair loss 3 months into treatment with buspirone. After cessation, her alopecia resolved.

Questionable efficacy for some anxiety subtypes. Buspirone has been studied as a treatment of other common psychiatric conditions, such as social phobia and anxiety in the setting of smoking cessation. However, it has not proven to be effective over placebo in treating these anxiety subtypes.25,26

Short half-life. Because of its relatively short half-life (2 to 3 hours), buspirone requires dosing 2 to 3 times a day, which could increase the risk of noncompliance.4 However, some patients might prefer multiple dosing throughout the day due to perceived better coverage of their anxiety symptoms.

Limited incentive for future research. Because buspirone is available only as a generic formulation, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies and other interested parties to study what may be valuable uses for buspirone. For example, there is no data available on comparative augmentation of buspirone and SGAs with antidepressants for depression and/or anxiety. There is also little data available about buspirone prescribing trends or why buspirone may be underutilized in clinical practice today.

Continue to: Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal...

Unfortunately, historical and longitudinal data on the prescribing practices of buspirone is limited because the original branded medication, BuSpar, is no longer on the market. However, this medication offers multiple advantages over other agents used to treat anxiety, and it should not be forgotten when formulating a treatment regimen for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

Bottom Line

Buspirone is a safe, low-cost, effective treatment option for patients with anxiety and may be helpful as an augmenting agent for depression. Because of its efficacy and high degree of tolerability, it should be prioritized higher in our treatment algorithms and be a part of our routine pharmacologic armamentarium.

Related Resources

- Howland RH. Buspirone: Back to the future. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2015;53(11):21-24.

- Strawn JR, Mills JA, Cornwall GJ, et al. Buspirone in children and adolescents with anxiety: a review and Bayesian analysis of abandoned randomized controlled trials. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2018;28(1):2-9.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Buspirone • BuSpar

Citalopram • Celexa

Haloperidol • Haldol

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

1. Fickweiler F, Fickweiler W, Urbach E. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry generally and sales representatives specifically and their association with physicians’ attitudes and prescribing habits: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e016408. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016408.

2. Haque M. Generic medicine and prescribing: a quick assessment. Adv Hum Biol. 2017;7(3):101-108.

3. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Anxiety disorders. https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Anxiety-Disorders. Published December 2017. Accessed November 26, 2019.

4. Buspar [package insert]. Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2000.

5. Hjorth S, Carlsson A. Buspirone: effects on central monoaminergic transmission-possible relevance to animal experimental and clinical findings. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982:83;299-303.

6. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: neuroscientific basis and practical applications, 4th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

7. Buspirone tablets [package insert]. East Brunswick, NJ: Strides Pharma Inc; 2017.

8. Lilja JJ, Kivistö KT, Backman, JT, et al. Grapefruit juice substantially increases plasma concentrations of buspirone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:655-660.

9. Stahl SM. Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology: prescriber’s guide, 6th ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2017.

10. Sumiyoshi T, Park S, Jayathilake K. Effect of buspirone, a serotonin1A partial agonist, on cognitive function in schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2007;95(1-3):158-168.

11. Schechter LE, Dawson LA, Harder JA. The potential utility of 5-HT1A receptor antagonists in the treatment of cognitive dysfunction associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(2):139-145.

12. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Del Boca FK. Buspirone treatment of anxious alcoholics: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(9):720-731.

13. Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:1-25.

14. Appelberg BG, Syvälahti EK, Koskinen TE, et al. Patients with severe depression may benefit from buspirone augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: results from a placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, placebo wash-in study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001; 62(6):448-452.

15. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 3rd edition. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf. Published May 2010. Accessed November 2019.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/labeling/pregnancy-and-lactation-labeling-drugs-final-rule. Published September 11, 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

17. Goa KL, Ward A. Buspirone. A preliminary review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy as an anxiolytic. Drugs. 1986;32(2):114-129.

18. GoodRx. Buspar prices, coupons, & savings tips in U.S. area code 08054. https://www.goodrx.com/buspar. Accessed June 6, 2019.

19. Landén M, Eriksson E, Agren H, et al. Effect of buspirone on sexual dysfunction in depressed patients treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(3):268-271.

20. Hensley PL, Nurnberg HG. SSRI sexual dysfunction: a female perspective. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(suppl 1):143-153.

21. Haleem DJ, Samad N, Haleem MA. Reversal of haloperidol-induced extrapyramidal symptoms by buspirone: a time-related study. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18(2):147-153.

22. Kaplan SS, Saddock BJ, Grebb JA. Synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

23. National Alliance on Mental Health. Buspirone (BuSpar). https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Treatment/Mental-Health-Medications/Types-of-Medication/Buspirone-(BuSpar). Published January 2019. Accessed November 26, 2019.

24. Faber J, Sansone RA. Buspirone: a possible cause of alopecia. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(1):13.

25. Van Vliet IM, Den Boer JA, Westenberg HGM, et al. Clinical effects of buspirone in social phobia, a double-blind placebo controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):164-168.

26. Schneider NG, Olmstead RE, Steinberg C, et al. Efficacy of buspirone in smoking cessation: a placebo‐controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60(5):568-575.