User login

No survival dip with neoadjuvant letrozole-palbociclib in NeoPAL study

Three-year survival rates were similarly high among postmenopausal women with high-risk early luminal breast cancer who were treated with either the neoadjuvant combination of letrozole and palbociclib (Ibrance) or standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the phase 2 NeoPAL study.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was a respective 86.7% and 87.2%, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.01 (P = .98) comparing the endocrine therapy and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor combination versus FEC/taxane chemotherapy.

There were also no differences between the two treatment arms in terms of invasive disease-free survival (iDFS, HR = 0.83, P = .71) or breast cancer–specific survival (BCSS), although the latter was an exploratory endpoint alongside overall survival (OS).

“The lack of difference is impressive,” said Hope S. Rugo, MD, FASCO, who commented independently on the study’s findings after their presentation at the European Society for Medical Oncology: Breast Cancer virtual meeting.

“Overall survival in patients who received chemotherapy appears to be better, but the very small numbers here make interpretation of this difference impossible,” observed Dr. Rugo, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco’s Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Unfortunately, this study is underpowered for definitive conclusions,” acknowledged study investigator Suzette Delaloge, MD, associate professor of medical oncology at Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France.

However, “it shows that the nonchemotherapy, preoperative letrozole/palbociclib approach deserves further exploration and could be an option for a chemotherapy-free regimen in some specific cases.”

Primary data already reported

The NeoPAL study was an open-label, randomized study conducted in 27 centers throughout France that compared the preoperative use of letrozole plus palbociclib to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in 106 postmenopausal patients with either luminal A or B node-positive disease.

Patients were considered for inclusion in the trial if they had been newly diagnosed with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative stage I-III breast cancer and were not candidates for breast conservation. Genetic testing was used to confirm that only those with luminal B, or luminal A and who were node positive were recruited.

Neoadjuvant treatment consisted of either letrozole (2.5 mg/day) and palbociclib (125 mg daily for 3 weeks out of 4 weeks) for 19 weeks or three 21-day cycles of 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2), epirubicin (100 mg/m2), and cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2), followed by three 21-day cycles of docetaxel (100 mg/m2).

The primary endpoint was the pathological complete response (pCR), defined as a residual cancer burden (RCB) of 0 to 1. Results, which have already been reported, showed equivalent, but perhaps disappointingly low, pathological responses in both the letrozole/palbociclib and chemotherapy arms (3.8% and 5.9%, respectively).

There were, however, identical clinical responses (at around 75%) and “encouraging biomarker responses in the Prosigna-defined high risk luminal breast cancer population,” Dr. Delaloge said.

The NeoPAL findings were on par with those of the CORALLEEN study, Dr. Delaloge suggested. That trial, as Dr. Rugo has also pointed out, was conducted in 106 patients with luminal B early breast cancer and used a combination of letrozole and the CDK 4/6 inhibitor ribociclib (Kisquali).

Future studies needed

NeoPAL “is a small study with relatively short follow-up even for hormone receptor-positive, high-risk disease,” Dr. Rugo observed. However, she qualified “this short follow-up can be very meaningful in high-risk disease.” as shown by other CDK 4/6 inhibitor trials.

Dr. Rugo also noted: “Short-term biologic endpoints are clearly more informative following and during neoadjuvant endocrine therapy than pCR and this trial, as well as the data from previous studies, indicates that this is the case.”

Further, Dr. Rugo said: “Antiproliferative response is enhanced with CDK 4/6 inhibitors, but this doesn’t seem to translate into a difference in pCR. The lack of impact on longer term, outcome to date, provides support for ongoing trials.”

Two such trials are already underway. The 200-patient CARABELA trial started recruitment in March last year and is comparing endocrine therapy with letrozole plus the CDK 4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib (Verzenio) to standard chemotherapy in patients with hormone receptor–positive, high-risk Ki67 disease.

Then there is the ADAPTcycle trial, a large open-label, phase 3 trial that is randomizing patients based on Ki67 and recurrence score after a short preoperative induction with endocrine therapy to postoperative chemotherapy or to 2 years of endocrine therapy plus ribociclib, with both arms receiving a standard course of 5 years of endocrine therapy.

“These two studies have provided interesting information that will help us design studies in the future,” said Dr. Rugo.

Not only that, but they will also help “investigate the subgroups of patients that benefit the most from CDK 4/6 inhibitors and better study neoadjuvant endocrine therapy which is an important option for patients that can be evaluated in terms of its efficacy by short term measures of antiproliferative response.”

NeoPAL was sponsored by UNICANCER with funding from Pfizer and NanoString Technologies. Dr. Delaloge disclosed receiving research grants or funding via her institution from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck, Sanofi, Lilly, Novartis, BMS, Orion, Daiichi, Puma, and Pierre Fabre. Dr. Rugo reported receipt of grants via her institution to perform clinical trials from Pfizer and multiple other companies. She disclosed receiving honoraria from PUMA, Samsung, and Mylan.

Three-year survival rates were similarly high among postmenopausal women with high-risk early luminal breast cancer who were treated with either the neoadjuvant combination of letrozole and palbociclib (Ibrance) or standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the phase 2 NeoPAL study.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was a respective 86.7% and 87.2%, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.01 (P = .98) comparing the endocrine therapy and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor combination versus FEC/taxane chemotherapy.

There were also no differences between the two treatment arms in terms of invasive disease-free survival (iDFS, HR = 0.83, P = .71) or breast cancer–specific survival (BCSS), although the latter was an exploratory endpoint alongside overall survival (OS).

“The lack of difference is impressive,” said Hope S. Rugo, MD, FASCO, who commented independently on the study’s findings after their presentation at the European Society for Medical Oncology: Breast Cancer virtual meeting.

“Overall survival in patients who received chemotherapy appears to be better, but the very small numbers here make interpretation of this difference impossible,” observed Dr. Rugo, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco’s Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Unfortunately, this study is underpowered for definitive conclusions,” acknowledged study investigator Suzette Delaloge, MD, associate professor of medical oncology at Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France.

However, “it shows that the nonchemotherapy, preoperative letrozole/palbociclib approach deserves further exploration and could be an option for a chemotherapy-free regimen in some specific cases.”

Primary data already reported

The NeoPAL study was an open-label, randomized study conducted in 27 centers throughout France that compared the preoperative use of letrozole plus palbociclib to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in 106 postmenopausal patients with either luminal A or B node-positive disease.

Patients were considered for inclusion in the trial if they had been newly diagnosed with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative stage I-III breast cancer and were not candidates for breast conservation. Genetic testing was used to confirm that only those with luminal B, or luminal A and who were node positive were recruited.

Neoadjuvant treatment consisted of either letrozole (2.5 mg/day) and palbociclib (125 mg daily for 3 weeks out of 4 weeks) for 19 weeks or three 21-day cycles of 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2), epirubicin (100 mg/m2), and cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2), followed by three 21-day cycles of docetaxel (100 mg/m2).

The primary endpoint was the pathological complete response (pCR), defined as a residual cancer burden (RCB) of 0 to 1. Results, which have already been reported, showed equivalent, but perhaps disappointingly low, pathological responses in both the letrozole/palbociclib and chemotherapy arms (3.8% and 5.9%, respectively).

There were, however, identical clinical responses (at around 75%) and “encouraging biomarker responses in the Prosigna-defined high risk luminal breast cancer population,” Dr. Delaloge said.

The NeoPAL findings were on par with those of the CORALLEEN study, Dr. Delaloge suggested. That trial, as Dr. Rugo has also pointed out, was conducted in 106 patients with luminal B early breast cancer and used a combination of letrozole and the CDK 4/6 inhibitor ribociclib (Kisquali).

Future studies needed

NeoPAL “is a small study with relatively short follow-up even for hormone receptor-positive, high-risk disease,” Dr. Rugo observed. However, she qualified “this short follow-up can be very meaningful in high-risk disease.” as shown by other CDK 4/6 inhibitor trials.

Dr. Rugo also noted: “Short-term biologic endpoints are clearly more informative following and during neoadjuvant endocrine therapy than pCR and this trial, as well as the data from previous studies, indicates that this is the case.”

Further, Dr. Rugo said: “Antiproliferative response is enhanced with CDK 4/6 inhibitors, but this doesn’t seem to translate into a difference in pCR. The lack of impact on longer term, outcome to date, provides support for ongoing trials.”

Two such trials are already underway. The 200-patient CARABELA trial started recruitment in March last year and is comparing endocrine therapy with letrozole plus the CDK 4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib (Verzenio) to standard chemotherapy in patients with hormone receptor–positive, high-risk Ki67 disease.

Then there is the ADAPTcycle trial, a large open-label, phase 3 trial that is randomizing patients based on Ki67 and recurrence score after a short preoperative induction with endocrine therapy to postoperative chemotherapy or to 2 years of endocrine therapy plus ribociclib, with both arms receiving a standard course of 5 years of endocrine therapy.

“These two studies have provided interesting information that will help us design studies in the future,” said Dr. Rugo.

Not only that, but they will also help “investigate the subgroups of patients that benefit the most from CDK 4/6 inhibitors and better study neoadjuvant endocrine therapy which is an important option for patients that can be evaluated in terms of its efficacy by short term measures of antiproliferative response.”

NeoPAL was sponsored by UNICANCER with funding from Pfizer and NanoString Technologies. Dr. Delaloge disclosed receiving research grants or funding via her institution from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck, Sanofi, Lilly, Novartis, BMS, Orion, Daiichi, Puma, and Pierre Fabre. Dr. Rugo reported receipt of grants via her institution to perform clinical trials from Pfizer and multiple other companies. She disclosed receiving honoraria from PUMA, Samsung, and Mylan.

Three-year survival rates were similarly high among postmenopausal women with high-risk early luminal breast cancer who were treated with either the neoadjuvant combination of letrozole and palbociclib (Ibrance) or standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the phase 2 NeoPAL study.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was a respective 86.7% and 87.2%, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.01 (P = .98) comparing the endocrine therapy and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor combination versus FEC/taxane chemotherapy.

There were also no differences between the two treatment arms in terms of invasive disease-free survival (iDFS, HR = 0.83, P = .71) or breast cancer–specific survival (BCSS), although the latter was an exploratory endpoint alongside overall survival (OS).

“The lack of difference is impressive,” said Hope S. Rugo, MD, FASCO, who commented independently on the study’s findings after their presentation at the European Society for Medical Oncology: Breast Cancer virtual meeting.

“Overall survival in patients who received chemotherapy appears to be better, but the very small numbers here make interpretation of this difference impossible,” observed Dr. Rugo, professor of medicine at the University of California San Francisco’s Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Unfortunately, this study is underpowered for definitive conclusions,” acknowledged study investigator Suzette Delaloge, MD, associate professor of medical oncology at Institut Gustave Roussy in Villejuif, France.

However, “it shows that the nonchemotherapy, preoperative letrozole/palbociclib approach deserves further exploration and could be an option for a chemotherapy-free regimen in some specific cases.”

Primary data already reported

The NeoPAL study was an open-label, randomized study conducted in 27 centers throughout France that compared the preoperative use of letrozole plus palbociclib to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in 106 postmenopausal patients with either luminal A or B node-positive disease.

Patients were considered for inclusion in the trial if they had been newly diagnosed with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative stage I-III breast cancer and were not candidates for breast conservation. Genetic testing was used to confirm that only those with luminal B, or luminal A and who were node positive were recruited.

Neoadjuvant treatment consisted of either letrozole (2.5 mg/day) and palbociclib (125 mg daily for 3 weeks out of 4 weeks) for 19 weeks or three 21-day cycles of 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2), epirubicin (100 mg/m2), and cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2), followed by three 21-day cycles of docetaxel (100 mg/m2).

The primary endpoint was the pathological complete response (pCR), defined as a residual cancer burden (RCB) of 0 to 1. Results, which have already been reported, showed equivalent, but perhaps disappointingly low, pathological responses in both the letrozole/palbociclib and chemotherapy arms (3.8% and 5.9%, respectively).

There were, however, identical clinical responses (at around 75%) and “encouraging biomarker responses in the Prosigna-defined high risk luminal breast cancer population,” Dr. Delaloge said.

The NeoPAL findings were on par with those of the CORALLEEN study, Dr. Delaloge suggested. That trial, as Dr. Rugo has also pointed out, was conducted in 106 patients with luminal B early breast cancer and used a combination of letrozole and the CDK 4/6 inhibitor ribociclib (Kisquali).

Future studies needed

NeoPAL “is a small study with relatively short follow-up even for hormone receptor-positive, high-risk disease,” Dr. Rugo observed. However, she qualified “this short follow-up can be very meaningful in high-risk disease.” as shown by other CDK 4/6 inhibitor trials.

Dr. Rugo also noted: “Short-term biologic endpoints are clearly more informative following and during neoadjuvant endocrine therapy than pCR and this trial, as well as the data from previous studies, indicates that this is the case.”

Further, Dr. Rugo said: “Antiproliferative response is enhanced with CDK 4/6 inhibitors, but this doesn’t seem to translate into a difference in pCR. The lack of impact on longer term, outcome to date, provides support for ongoing trials.”

Two such trials are already underway. The 200-patient CARABELA trial started recruitment in March last year and is comparing endocrine therapy with letrozole plus the CDK 4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib (Verzenio) to standard chemotherapy in patients with hormone receptor–positive, high-risk Ki67 disease.

Then there is the ADAPTcycle trial, a large open-label, phase 3 trial that is randomizing patients based on Ki67 and recurrence score after a short preoperative induction with endocrine therapy to postoperative chemotherapy or to 2 years of endocrine therapy plus ribociclib, with both arms receiving a standard course of 5 years of endocrine therapy.

“These two studies have provided interesting information that will help us design studies in the future,” said Dr. Rugo.

Not only that, but they will also help “investigate the subgroups of patients that benefit the most from CDK 4/6 inhibitors and better study neoadjuvant endocrine therapy which is an important option for patients that can be evaluated in terms of its efficacy by short term measures of antiproliferative response.”

NeoPAL was sponsored by UNICANCER with funding from Pfizer and NanoString Technologies. Dr. Delaloge disclosed receiving research grants or funding via her institution from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Roche, Merck, Sanofi, Lilly, Novartis, BMS, Orion, Daiichi, Puma, and Pierre Fabre. Dr. Rugo reported receipt of grants via her institution to perform clinical trials from Pfizer and multiple other companies. She disclosed receiving honoraria from PUMA, Samsung, and Mylan.

FROM ESMO BREAST CANCER 2021

BERENICE: Further evidence of heart safety of dual HER2 blockade

Dual HER2 blockade with pertuzumab (Perjeta) and trastuzumab (Herceptin) on top of anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer was associated with a low rate of clinically relevant cardiac events in the final follow-up of the BERENICE study.

After more than 5 years, 1.0%-1.5% of patients who had locally advanced, inflammatory, or early-stage breast cancer developed heart failure, and around 12%-13% showed any significant changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Importantly, “there were no new safety concerns that arose during long-term follow-up,” study investigator Chau Dang, MD, said in presenting the findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology: Breast Cancer virtual meeting.

Dr. Dang, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, reported that the most common cause of death was disease progression.

BERENICE was designed as a cardiac safety study and so not powered to look at long-term efficacy, which Dr. Dang was clear in reporting. Nevertheless event-free survival (EFS), invasive disease-free survival (IDFS), and overall survival (OS) rates at 5 years were all high, at least a respective 89.2%, 91%, and 93.8%, she said. “The medians have not been reached,” she observed.

“These data support the use of dual HER2 blockade with pertuzumab-trastuzumab–based regimens, including in combination with dose-dense, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, across the neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment settings for the complete treatment of patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer,” Dr. Dang said.

Evandro de Azambuja, MD, PhD, the invited discussant for the trial agreed that the regimens tested appeared “safe from a cardiac standpoint.” However, “you cannot forget that today we are using much less anthracyclines in our patient population.”

Patients in trials are also very different from those treated in clinical practice, often being younger and much fitter, he said. Therefore, it may be important to look at the baseline cardiac medications and comorbidities, Dr. de Azambuja, a medical oncologist at the Institut Jules Bordet in Brussels, Belgium, suggested.

That said, the BERENICE findings sit well with other trials that have been conducted, Dr. de Azambuja pointed out.

“If we look at other trials that have also tested dual HER2 blockade with anthracycline or nonanthracycline regimens, all of them reassure that dual blockade is not more cardiotoxic than single blockade,” he said. This includes trials such as TRYPHAENA, APHINITY, KRISTINE, NeoSphere and PEONY.

The 3-year IDFS rate of 91% in BERENICE also compares well to that seen in APHINITY (94%), Dr. de Azambuja said.

BERENICE study design

BERENICE was a multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized and noncomparative phase 2 trial that recruited 400 patients across 75 centers in 12 countries.

Eligibility criteria were that participants had to have been centrally confirmed HER2-positive locally advanced, inflammatory or early breast cancer, with the latter defined as tumors bigger than 2 cm or greater than 5 mm in size, and be node-positive. Patients also had to have a starting LVEF of 55% or higher.

Patients were allocated to one of two neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens depending on the choice of their physician. One group received a regimen of dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (ddAC) given every 2 weeks for four cycles and then paclitaxel every week for 12 cycles. The other group received 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) every 3 weeks for four cycles and then docetaxel every 3 weeks for four cycles.

Pertuzumab and trastuzumab were started at the same time as the taxanes in both groups and given every 3 weeks for four cycles. Patients then underwent surgery and continued pertuzumab/trastuzumab treatment alone for a further 13 cycles.

The co-primary endpoints were the incidence of New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic LVEF decline of 10% or more.

The primary analysis of the trial was published in 2018 and, at that time, it was reported that three patients in the ddAC cohort and none in the FEC cohort experienced heart failure. LVEF decline was observed in a respective 6.5% and 2% of patients.

Discussion points

Dr. de Azambuja noted that the contribution of the chemotherapy to the efficacy cannot be assessed because of the nonrandomized trial design. That should not matter, pointed out Sybille Loibl, MD, PhD, during discussion.

“I think it compares nicely to other trials that looked at dose-dense chemotherapy,” said Dr. Loibl, who is an associate professor at the University of Frankfurt in Germany. “It seems that, in the light of what we consider today probably one of the best anti-HER2 treatments, the chemotherapy is less relevant, and that’s why a dose-dense regimen doesn’t add so much on a standard anthracycline taxane-containing regimen.”

Dr. de Azambuja also commented on the assessment of cardiotoxicity and the use of reduced LVEF as a measure: LVEF decline is a late effect of cardiotoxicity, he observed, and he suggested a different approach in future trials.

“If you use Global Longitudinal Strain, this could be an optimal parameter to detect early subclinical LVEF dysfunction and you should consider it for the next trials looking for cardiac safety. Also, cardiac biomarkers. This was not implemented in this trial, and I strongly recommend this should be for the next trial.”

The BERENICE trial was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Dang disclosed receiving consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, and Puma Biotechnology. Dr. de Azambuja was not involved in the study but disclosed receiving honoraria, travel grants, research grants from Roche and Genentech as well as from other companies. Dr. Loibl was one of the cochairs of the session and, among disclosures regarding many other companies, has been an invited speaker for Roche and received reimbursement via her institution for a writing engagement.

Dual HER2 blockade with pertuzumab (Perjeta) and trastuzumab (Herceptin) on top of anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer was associated with a low rate of clinically relevant cardiac events in the final follow-up of the BERENICE study.

After more than 5 years, 1.0%-1.5% of patients who had locally advanced, inflammatory, or early-stage breast cancer developed heart failure, and around 12%-13% showed any significant changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Importantly, “there were no new safety concerns that arose during long-term follow-up,” study investigator Chau Dang, MD, said in presenting the findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology: Breast Cancer virtual meeting.

Dr. Dang, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, reported that the most common cause of death was disease progression.

BERENICE was designed as a cardiac safety study and so not powered to look at long-term efficacy, which Dr. Dang was clear in reporting. Nevertheless event-free survival (EFS), invasive disease-free survival (IDFS), and overall survival (OS) rates at 5 years were all high, at least a respective 89.2%, 91%, and 93.8%, she said. “The medians have not been reached,” she observed.

“These data support the use of dual HER2 blockade with pertuzumab-trastuzumab–based regimens, including in combination with dose-dense, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, across the neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment settings for the complete treatment of patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer,” Dr. Dang said.

Evandro de Azambuja, MD, PhD, the invited discussant for the trial agreed that the regimens tested appeared “safe from a cardiac standpoint.” However, “you cannot forget that today we are using much less anthracyclines in our patient population.”

Patients in trials are also very different from those treated in clinical practice, often being younger and much fitter, he said. Therefore, it may be important to look at the baseline cardiac medications and comorbidities, Dr. de Azambuja, a medical oncologist at the Institut Jules Bordet in Brussels, Belgium, suggested.

That said, the BERENICE findings sit well with other trials that have been conducted, Dr. de Azambuja pointed out.

“If we look at other trials that have also tested dual HER2 blockade with anthracycline or nonanthracycline regimens, all of them reassure that dual blockade is not more cardiotoxic than single blockade,” he said. This includes trials such as TRYPHAENA, APHINITY, KRISTINE, NeoSphere and PEONY.

The 3-year IDFS rate of 91% in BERENICE also compares well to that seen in APHINITY (94%), Dr. de Azambuja said.

BERENICE study design

BERENICE was a multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized and noncomparative phase 2 trial that recruited 400 patients across 75 centers in 12 countries.

Eligibility criteria were that participants had to have been centrally confirmed HER2-positive locally advanced, inflammatory or early breast cancer, with the latter defined as tumors bigger than 2 cm or greater than 5 mm in size, and be node-positive. Patients also had to have a starting LVEF of 55% or higher.

Patients were allocated to one of two neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens depending on the choice of their physician. One group received a regimen of dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (ddAC) given every 2 weeks for four cycles and then paclitaxel every week for 12 cycles. The other group received 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) every 3 weeks for four cycles and then docetaxel every 3 weeks for four cycles.

Pertuzumab and trastuzumab were started at the same time as the taxanes in both groups and given every 3 weeks for four cycles. Patients then underwent surgery and continued pertuzumab/trastuzumab treatment alone for a further 13 cycles.

The co-primary endpoints were the incidence of New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic LVEF decline of 10% or more.

The primary analysis of the trial was published in 2018 and, at that time, it was reported that three patients in the ddAC cohort and none in the FEC cohort experienced heart failure. LVEF decline was observed in a respective 6.5% and 2% of patients.

Discussion points

Dr. de Azambuja noted that the contribution of the chemotherapy to the efficacy cannot be assessed because of the nonrandomized trial design. That should not matter, pointed out Sybille Loibl, MD, PhD, during discussion.

“I think it compares nicely to other trials that looked at dose-dense chemotherapy,” said Dr. Loibl, who is an associate professor at the University of Frankfurt in Germany. “It seems that, in the light of what we consider today probably one of the best anti-HER2 treatments, the chemotherapy is less relevant, and that’s why a dose-dense regimen doesn’t add so much on a standard anthracycline taxane-containing regimen.”

Dr. de Azambuja also commented on the assessment of cardiotoxicity and the use of reduced LVEF as a measure: LVEF decline is a late effect of cardiotoxicity, he observed, and he suggested a different approach in future trials.

“If you use Global Longitudinal Strain, this could be an optimal parameter to detect early subclinical LVEF dysfunction and you should consider it for the next trials looking for cardiac safety. Also, cardiac biomarkers. This was not implemented in this trial, and I strongly recommend this should be for the next trial.”

The BERENICE trial was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Dang disclosed receiving consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, and Puma Biotechnology. Dr. de Azambuja was not involved in the study but disclosed receiving honoraria, travel grants, research grants from Roche and Genentech as well as from other companies. Dr. Loibl was one of the cochairs of the session and, among disclosures regarding many other companies, has been an invited speaker for Roche and received reimbursement via her institution for a writing engagement.

Dual HER2 blockade with pertuzumab (Perjeta) and trastuzumab (Herceptin) on top of anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer was associated with a low rate of clinically relevant cardiac events in the final follow-up of the BERENICE study.

After more than 5 years, 1.0%-1.5% of patients who had locally advanced, inflammatory, or early-stage breast cancer developed heart failure, and around 12%-13% showed any significant changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

Importantly, “there were no new safety concerns that arose during long-term follow-up,” study investigator Chau Dang, MD, said in presenting the findings at the European Society for Medical Oncology: Breast Cancer virtual meeting.

Dr. Dang, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre in New York, reported that the most common cause of death was disease progression.

BERENICE was designed as a cardiac safety study and so not powered to look at long-term efficacy, which Dr. Dang was clear in reporting. Nevertheless event-free survival (EFS), invasive disease-free survival (IDFS), and overall survival (OS) rates at 5 years were all high, at least a respective 89.2%, 91%, and 93.8%, she said. “The medians have not been reached,” she observed.

“These data support the use of dual HER2 blockade with pertuzumab-trastuzumab–based regimens, including in combination with dose-dense, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, across the neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment settings for the complete treatment of patients with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer,” Dr. Dang said.

Evandro de Azambuja, MD, PhD, the invited discussant for the trial agreed that the regimens tested appeared “safe from a cardiac standpoint.” However, “you cannot forget that today we are using much less anthracyclines in our patient population.”

Patients in trials are also very different from those treated in clinical practice, often being younger and much fitter, he said. Therefore, it may be important to look at the baseline cardiac medications and comorbidities, Dr. de Azambuja, a medical oncologist at the Institut Jules Bordet in Brussels, Belgium, suggested.

That said, the BERENICE findings sit well with other trials that have been conducted, Dr. de Azambuja pointed out.

“If we look at other trials that have also tested dual HER2 blockade with anthracycline or nonanthracycline regimens, all of them reassure that dual blockade is not more cardiotoxic than single blockade,” he said. This includes trials such as TRYPHAENA, APHINITY, KRISTINE, NeoSphere and PEONY.

The 3-year IDFS rate of 91% in BERENICE also compares well to that seen in APHINITY (94%), Dr. de Azambuja said.

BERENICE study design

BERENICE was a multicenter, open-label, nonrandomized and noncomparative phase 2 trial that recruited 400 patients across 75 centers in 12 countries.

Eligibility criteria were that participants had to have been centrally confirmed HER2-positive locally advanced, inflammatory or early breast cancer, with the latter defined as tumors bigger than 2 cm or greater than 5 mm in size, and be node-positive. Patients also had to have a starting LVEF of 55% or higher.

Patients were allocated to one of two neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimens depending on the choice of their physician. One group received a regimen of dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (ddAC) given every 2 weeks for four cycles and then paclitaxel every week for 12 cycles. The other group received 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) every 3 weeks for four cycles and then docetaxel every 3 weeks for four cycles.

Pertuzumab and trastuzumab were started at the same time as the taxanes in both groups and given every 3 weeks for four cycles. Patients then underwent surgery and continued pertuzumab/trastuzumab treatment alone for a further 13 cycles.

The co-primary endpoints were the incidence of New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure and incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic LVEF decline of 10% or more.

The primary analysis of the trial was published in 2018 and, at that time, it was reported that three patients in the ddAC cohort and none in the FEC cohort experienced heart failure. LVEF decline was observed in a respective 6.5% and 2% of patients.

Discussion points

Dr. de Azambuja noted that the contribution of the chemotherapy to the efficacy cannot be assessed because of the nonrandomized trial design. That should not matter, pointed out Sybille Loibl, MD, PhD, during discussion.

“I think it compares nicely to other trials that looked at dose-dense chemotherapy,” said Dr. Loibl, who is an associate professor at the University of Frankfurt in Germany. “It seems that, in the light of what we consider today probably one of the best anti-HER2 treatments, the chemotherapy is less relevant, and that’s why a dose-dense regimen doesn’t add so much on a standard anthracycline taxane-containing regimen.”

Dr. de Azambuja also commented on the assessment of cardiotoxicity and the use of reduced LVEF as a measure: LVEF decline is a late effect of cardiotoxicity, he observed, and he suggested a different approach in future trials.

“If you use Global Longitudinal Strain, this could be an optimal parameter to detect early subclinical LVEF dysfunction and you should consider it for the next trials looking for cardiac safety. Also, cardiac biomarkers. This was not implemented in this trial, and I strongly recommend this should be for the next trial.”

The BERENICE trial was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche. Dr. Dang disclosed receiving consultancy fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Genentech, Daiichi Sankyo, Lilly, and Puma Biotechnology. Dr. de Azambuja was not involved in the study but disclosed receiving honoraria, travel grants, research grants from Roche and Genentech as well as from other companies. Dr. Loibl was one of the cochairs of the session and, among disclosures regarding many other companies, has been an invited speaker for Roche and received reimbursement via her institution for a writing engagement.

FROM ESMO BREAST CANCER 2021

Screening High-Risk Women Veterans for Breast Cancer

The number of women seeking care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is increasing.1 In 2015, there were 2 million women veterans in the United States, which is 9.4% of the total veteran population. This group is expected to increase at an average of about 18,000 women per year for the next 10 years.2 The percentage of women veterans who are US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) users aged 45 to 64 years rose 46% from 2000 to 2015.1,3-4 It is estimated that 15% of veterans who used VA services in 2020 were women.1 Nineteen percent of women veterans are Black.1 The median age of women veterans in 2015 was 50 years.5 Breast cancer is the leading cancer affecting female veterans, and data suggest they have an increased risk of breast cancer based on unique service-related exposures.1,6-9

In the US, about 10 million women are eligible for breast cancer preventive therapy, including, but not limited to, medications, surgery, or lifestyle changes.10 Secondary prevention options include change in surveillance that can reduce their risk or identify cancer at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective. The United States Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the Oncology Nursing Society recommend screening women aged ≥ 35 years to assess breast cancer risk.11-18 If a woman is at increased risk, she may be a candidate for chemoprevention, prozphylactic surgery, and possibly an enhanced screening regimen.

Urban and minority women are an understudied population. Most veterans (75%) live in urban or suburban settings.19,20 Urban veteran women constitute an important potential study population.

Chemoprevention measures have been underused because of factors involving both women and their health care providers. A large proportion of women are unaware of their higher risk status due to lack of adequate screening and risk assessment.21,22 In addition to patient lack of awareness of their high-risk status, primary care physicians are also reluctant to prescribe chemopreventive agents due to a lack of comfort or familiarity with the risks and benefits.23-26 The STAR2015, BCPT2005, IBIS2014, MAP3 2011, IBIS-I 2014, and IBIS II 2014 studies clearly demonstrate a 49 to 62% reduction in risk for women using chemoprevention such as selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors, respectively.27-32 Yet only 4 to 9% of high-risk women not enrolled in a clinical trial are using chemoprevention.33-39

The possibility of developing breast cancer also may be increased because of a positive family history or being a member of a family in which there is a known susceptibility gene mutation.40 Based on these risk factors, women may be eligible for tailored follow-up and genetic counseling.41-44

Nationally, 7 to 10% of the civilian US population will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).45 The rates are remarkably higher for women veterans, with roughly 20% diagnosed with PTSD.46,47 Anxiety and PTSD have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49

In 2014, a national VA multidisciplinary group focused on breast cancer prevention, detection, treatment, and research to address breast health in the growing population of women veterans. High-risk breast cancer screenings are not routinely carried out by the VA in primary care, women’s health, or oncology services. Furthermore, the recording of screening questionnaire results was not synchronized until a standard questionnaire was created and approved as a template by this group in the VA electronic medical record (EMR) in 2015.

Several prediction models can identify which women are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. The most commonly used risk assessment model, the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool (BCRAT), has been refined to include women of additional ethnicities (https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool).

This pilot project was launched to identify an effective manner to screen women veterans regarding their risk of developing breast cancer and refer them for chemoprevention education or genetic counseling as appropriate.

Methods

A high-risk breast cancer screening questionnaire based on the Gail BCRAT and including lifestyle questions was developed and included as a note template in the VA EMR. The James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY (JJPVAMC) and the Washington DC VA Medical Center (DCVAMC) ran a pilot study between 2015 and 2018 using this breast cancer screening questionnaire to collect data from women veterans. Quality Executive Committee and institutional review board approvals were granted respectively.

Eligibility criteria included women aged ≥ 35 years with no personal history of breast cancer. Most patients were self-referred, but participants also were recruited during VA Breast Cancer Awareness month events, health fairs, or at informational tables in the hospital lobbies. After completing the 20 multiple choice questionnaire with a study team member, either in person or over the phone, a 5-year and lifetime risk of invasive breast cancer was calculated using the Gail BCRAT. A woman is considered high risk and eligible for chemoprevention if her 5-year risk is > 1.66% or her lifetime risk is ≥ 20%. Eligibility for genetic counseling is based on the Breast Cancer Referral Screening Tool, which includes a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer and Jewish ancestry.

All patients were notified of their average or high risk status by a clinician. Those who were deemed to be average risk received a follow-up letter in the mail with instructions (eg, to follow-up with a yearly mammogram). Those who were deemed to be high risk for developing breast cancer were asked to come in for an appointment with the study principal investigator (a VA oncologist/breast cancer specialist) to discuss prevention options, further screening, or referrals to genetic counseling. Depending on a patient’s other health factors, a woman at high risk for developing breast cancer also may be a candidate for chemoprevention with tamoxifen, raloxifene, exemestane, anastrozole, or letrozole.

Data on the participant’s lifestyle, including exercise, diet, and smoking, were evaluated to determine whether these factors had an impact on risk status.

Results

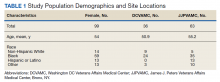

The JJP and DC VAMCs screened 103 women veterans between 2015 and 2018. Four patients were excluded for nonveteran (spousal) status, leaving 99 women veterans with a mean age of 54 years. The most common self-reported races were Black (60%), non-Hispanic White (14%), and Hispanic or Latino (13%) (Table 1).

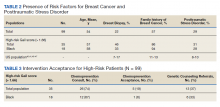

Women veterans in our study were nearly 3-times more likely than the general population were to receive a high-risk Gail Score/BCRAT (35% vs 13%, respectively).50,51 Of this subset, 46% had breast biopsies, and 86% had a positive family history. Thirty-one percent of Black women in our study were high risk, while nationally, 8.2 to 13.3% of Black women aged 50 to 59 years are considered high risk.50,51 Of the Black high-risk group with a high Gail/BCRAT score, 94% had a positive family history, and 33% had a history of breast biopsy (Table 2).

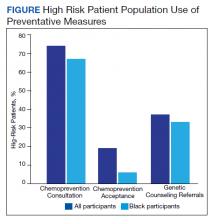

Of the 35 high-risk patients 26 (74%) patients accepted consultations for chemoprevention and 5 (19%) started chemoprevention. Of this high-risk group, 13 (37%) patients were referred for genetic counseling (Table 3).44 The prevalence of PTSD was present in 31% of high-risk women and 29% of the cohort (Figure).The lifestyle questions indicated that, among all participants, 79% had an overweight or obese body mass index; 58% exercised weekly; 51% consumed alcohol; 14% were smokers; and 21% consumed 3 to 4 servings of fruits/vegetables daily.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women.52 The number of women with breast cancer in the VHA has more than tripled from 1995 to 2012.1 The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in the general population is about 13%.50 This rate can be affected by risk factors including age, hormone exposure, family history, radiation exposure, and lifestyle factors, such as weight and alcohol use.6,52-56 In the United States, invasive breast cancer affects 1 in 8 women.50,52,57

Our screened population showed nearly 3 times as many women veterans were at an increased risk for breast cancer when compared with historical averages in US women. This difference may be based on a high rate of prior breast biopsies or positive family history, although a provocative study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database showed military women to have higher rates of breast cancer as well.9 Historically, Blacks are vastly understudied in clinical research with only 5% representation on a national level.5,58 The urban locations of both pilot sites (Washington, DC and Bronx, NY) allowed for the inclusion of minority patients in our study. We found that the rates of breast cancer in Black women veterans to be higher than seen nationally, possibly prompting further screening initiatives for this understudied population.

Our pilot study’s chemoprevention utilization (19%) was double the < 10% seen in the national population.33-35 The presence of a knowledgeable breast health practitioner to recruit study participants and offer personalized counseling to women veterans is a likely factor in overcoming barriers to chemopreventive acceptance. These participants may have been motivated to seek care for their high-risk status given a strong family history and prior breast biopsies.

Interestingly, a 3-fold higher PTSD rate was seen in this pilot population (29%) when compared with PTSD rates in the general female population (7-10%) and still one-third higher than the general population of women veterans (20%).45-47 Mental health, anxiety, and PTSD have been barriers to patients who sought treatment and have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49 Cancer screening can induce anxiety in patients, and it may be amplified in patients with PTSD. It was remarkable that although adherence with screening recommendations is decreased when PTSD is present, our patient population demonstrated a higher rate of screening adherence.

Women who are seen at the VA often use multiple clinical specialties, and their EMR can be accessed across VA medical centers nationwide. Therefore, identifying women veterans who meet screening criteria is easily attainable within the VA.

When comparing high-risk with average risk women, the lifestyle results (BMI, smoking history, exercise and consumption of fruits, vegetables and alcohol) were essentially the same. Lifestyle factors were similar to national population rates and were unlikely to impact risk levels.

Limitations

Study limitations included a high number of self-referrals and the large percentage of patients with a family history of breast cancer, making them more likely to seek screening. The higher-than-average risk of breast cancer may be driven by a high rate of breast biopsies and a strong family history. Lifestyle metrics could not be accurately compared to other national assessments of lifestyle factors due to the difference in data points that we used or the format of our questions.

Conclusions

As the number of women veterans increases and the incidence of breast cancer in women veterans rise, chemoprevention options should follow national guidelines. To our knowledge, this is the only oncology study with 60% Black women veterans. This study had a higher participation rate for Black women veterans than is typically seen in national research studies and shows the VA to be a germane source for further understanding of an understudied population that may benefit from increased screening for breast cancer.

A team-based, multidisciplinary model that meets the unique healthcare needs of women veterans results in a patient-centric delivery of care for assessing breast cancer risk status and prevention options. This model can be replicated nationally by directing primary care physicians and women’s health practitioners to a risk-assessment questionnaire and referring high-risk women for appropriate preventative care. Given that these results show chemoprevention adherence rates doubled those seen nationally, perhaps techniques used within this VA pilot study may be adapted to decrease breast cancer incidence nationally.

Since the rate of PTSD among women veterans is triple the national average, we would expect adherence rates to be lower in our patient cohort. However, the multidisciplinary approach we used in this study (eg, 1:1 consultation with oncologist; genetic counseling referrals; mental health support available), may have improved adherence rates. Perhaps the high rates of PTSD seen in the VA patient population can be a useful way to explore patient adherence rates in those with mental illness and medical conditions.

Future research with a larger cohort may lead to greater insight into the correlation between PTSD and adherence to treatment. Exploring the connection between breast cancer, epigenetics, and specific military service-related exposures could be an area of analysis among this veteran population exhibiting increased breast cancer rates. VAMCs are situated in rural, suburban, and urban locations across the United States and offers a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic patient population for inclusion in clinical investigations. Women veterans make up a small subpopulation of women in the United States, but it is worth considering VA patients as an untapped resource for research collaboration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Sanchez and Marissa Vallette, PhD, Breast Health Research Group. This research project was approved by the James J. Peters VA Medical Center Quality Executive Committee and the Washington, DC VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. The past, present and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf.

2. Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, et al. The VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S504-S509. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2476-3

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. Sourcebook: women veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 1: Sociodemographic characteristics and use of VHA care. Published December 2010. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2455

4. Bean-Mayberry B, Yano EM, Bayliss N, Navratil J, Weisman CS, Scholle SH. Federally funded comprehensive women’s health centers: leading innovation in women’s healthcare delivery. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(9):1281-1290. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0284

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.VA utilization profile FY 2016. Published November 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/QuickFacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.PDF

6. Ekenga CC, Parks CG, Sandler DP. Chemical exposures in the workplace and breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1765-1774. doi:10.1002/ijc.29545

7. Rennix CP, Quinn MM, Amoroso PJ, Eisen EA, Wegman DH. Risk of breast cancer among enlisted Army women occupationally exposed to volatile organic compounds. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(3):157-167. doi:10.1002/ajim.20201

8. Ritz B. Cancer mortality among workers exposed to chemicals during uranium processing. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(7):556-566. doi:10.1097/00043764-199907000-00004

9. Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the U.S. military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

10. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov 10;31(32):4167]. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327-2333. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0258

11. Greene, H. Cancer prevention, screening and early detection. In: Gobel BH, Triest-Robertson S, Vogel WH, eds. Advanced Oncology Nursing Certification Review and Resource Manual. 3rd ed. Oncology Nursing Society; 2016:1-34. https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdfs/2%20ADVPrac%20chapter%201.pdf

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. Version 1.2021 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Updated March 24, 2021 Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_risk.pdf

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Medications use to reduce risk. Updated September 3, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction

14. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Medications to decrease the risk for breast cancer in women: recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):698-708. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00717

15. Boucher JE. Chemoprevention: an overview of pharmacologic agents and nursing considerations. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):350-353. doi:10.1188/18.CJON.350-353

16. Nichols HB, Stürmer T, Lee VS, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention in an integrated health care setting. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1-12. doi:10.1200/CCI.16.00059

17. Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(11):1362-1389. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2018.0083

18. Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec 1;31(34):4383]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2942-2962. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122

19. Sealy-Jefferson S, Roseland ME, Cote ML, et al. rural-urban residence and stage at breast cancer diagnosis among postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(2):276-283. doi:10.1089/jwh.2017.6884

20. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America: 2011-2015. Published January 25, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/acs/acs-36.html

21. Owens WL, Gallagher TJ, Kincheloe MJ, Ruetten VL. Implementation in a large health system of a program to identify women at high risk for breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(2):85-88. doi:10.1200/JOP.2010.000107

2. Pivot X, Viguier J, Touboul C, et al. Breast cancer screening controversy: too much or not enough?. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24 Suppl:S73-S76. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000145

23. Bidassie B, Kovach A, Vallette MA, et al. Breast Cancer risk assessment and chemoprevention use among veterans affairs primary care providers: a national online survey. Mil Med. 2020;185(3-4):512-518. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz291

24. Brewster AM, Davidson NE, McCaskill-Stevens W. Chemoprevention for breast cancer: overcoming barriers to treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2012;85-90. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.152

25. Meyskens FL Jr, Curt GA, Brenner DE, et al. Regulatory approval of cancer risk-reducing (chemopreventive) drugs: moving what we have learned into the clinic. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(3):311-323. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0014

26. Tice JA, Kerlikowske K. Screening and prevention of breast cancer in primary care. Prim Care. 2009;36(3):533-558. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.04.003

27. Vogel VG. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer chemoprevention. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(13):1874-1887. doi:10.2174/138945011798184164

28. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2006 Dec 27;296(24):2926] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007 Sep 5;298(9):973]. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2727-2741. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074

29. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3230-3235. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

30. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2014 Mar 22;383(9922):1040] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Mar 11;389(10073):1010]. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8

31. Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Azambuja E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Dinh P, Cardoso F. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):329-339. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.07.005

32. Gabriel EM, Jatoi I. Breast cancer chemoprevention. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(2):223-228. doi:10.1586/era.11.206

33. Crew KD, Albain KS, Hershman DL, Unger JM, Lo SS. How do we increase uptake of tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens for breast cancer prevention?. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3:20. Published 2017 May 19. doi:10.1038/s41523-017-0021-y

34. Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3090-3095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8077

35. Smith SG, Sestak I, Forster A, et al. Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):575-590. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv590

36. Grann VR, Patel PR, Jacobson JS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of screening and prevention strategies among BRCA1/2-affected mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Feb;125(3):837-847. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1043-4

37. Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alés-Martínez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 6;365(14):1361]. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2381-2391. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1103507

38. Kmietowicz Z. Five in six women reject drugs that could reduce their risk of breast cancer. BMJ. 2015;351:h6650. Published 2015 Dec 8. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6650

39. Nelson HD, Fu R, Griffin JC, Nygren P, Smith ME, Humphrey L. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):703-235. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00147

40. Dahabreh IJ, Wieland LS, Adam GP, Halladay C, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Core needle and open surgery biopsy for diagnosis of breast lesions: an update to the 2009 report. Published September 2014. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK246878

41. National Cancer Institute. Genetics of breast and ovarian cancer (PDQ)—health profession version. Updated February 12, 2021. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/breast-and-ovarian/HealthProfessional

42. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences The sister study. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov/english/NIEHS.htm

43. Tutt A, Ashworth A. Can genetic testing guide treatment in breast cancer?. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(18):2774-2780. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.009

44. Katz SJ, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, et al. Gaps in receipt of clinically indicated genetic counseling after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1218-1224. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2369

45. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in adults? Updated October 17, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp

46. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in women? Updated October 16, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_women.asp

47. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in veterans? Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

48. Lindberg NM, Wellisch D. Anxiety and compliance among women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(4):298-303. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_9

49. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR appendix: breast cancer rates among black women and white women. Updated October 13, 2016. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/trends_invasive.htm

51. Richardson LC, Henley SJ, Miller JW, Massetti G, Thomas CC. Patterns and trends in age-specific black-white differences in breast cancer incidence and mortality - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(40):1093-1098. Published 2016 Oct 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6540a1

52. Brody JG, Moysich KB, Humblet O, Attfield KR, Beehler GP, Rudel RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2007;109(12 Suppl):2667-2711. doi:10.1002/cncr.22655

53. Brophy JT, Keith MM, Watterson A, et al. Breast cancer risk in relation to occupations with exposure to carcinogens and endocrine disruptors: a Canadian case-control study. Environ Health. 2012;11:87. Published 2012 Nov 19. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-11-87

54. Labrèche F, Goldberg MS, Valois MF, Nadon L. Postmenopausal breast cancer and occupational exposures. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(4):263-269. doi:10.1136/oem.2009.049817

55. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Interagency Breast Cancer & Environmental Research Coordinating Committee. Breast cancer and the environment: prioritizing prevention. Updated March 8, 2013. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/boards/ibcercc/index.cfm

56. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Pee D, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in African American women [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Aug 6;100(15):1118] [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Mar 5;100(5):373]. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(23):1782-1792. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm223

57. Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537-546. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x

58. Braunstein JB, Sherber NS, Schulman SP, Ding EL, Powe NR. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87(1):1-9. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181625d78

The number of women seeking care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is increasing.1 In 2015, there were 2 million women veterans in the United States, which is 9.4% of the total veteran population. This group is expected to increase at an average of about 18,000 women per year for the next 10 years.2 The percentage of women veterans who are US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) users aged 45 to 64 years rose 46% from 2000 to 2015.1,3-4 It is estimated that 15% of veterans who used VA services in 2020 were women.1 Nineteen percent of women veterans are Black.1 The median age of women veterans in 2015 was 50 years.5 Breast cancer is the leading cancer affecting female veterans, and data suggest they have an increased risk of breast cancer based on unique service-related exposures.1,6-9

In the US, about 10 million women are eligible for breast cancer preventive therapy, including, but not limited to, medications, surgery, or lifestyle changes.10 Secondary prevention options include change in surveillance that can reduce their risk or identify cancer at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective. The United States Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the Oncology Nursing Society recommend screening women aged ≥ 35 years to assess breast cancer risk.11-18 If a woman is at increased risk, she may be a candidate for chemoprevention, prozphylactic surgery, and possibly an enhanced screening regimen.

Urban and minority women are an understudied population. Most veterans (75%) live in urban or suburban settings.19,20 Urban veteran women constitute an important potential study population.

Chemoprevention measures have been underused because of factors involving both women and their health care providers. A large proportion of women are unaware of their higher risk status due to lack of adequate screening and risk assessment.21,22 In addition to patient lack of awareness of their high-risk status, primary care physicians are also reluctant to prescribe chemopreventive agents due to a lack of comfort or familiarity with the risks and benefits.23-26 The STAR2015, BCPT2005, IBIS2014, MAP3 2011, IBIS-I 2014, and IBIS II 2014 studies clearly demonstrate a 49 to 62% reduction in risk for women using chemoprevention such as selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors, respectively.27-32 Yet only 4 to 9% of high-risk women not enrolled in a clinical trial are using chemoprevention.33-39

The possibility of developing breast cancer also may be increased because of a positive family history or being a member of a family in which there is a known susceptibility gene mutation.40 Based on these risk factors, women may be eligible for tailored follow-up and genetic counseling.41-44

Nationally, 7 to 10% of the civilian US population will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).45 The rates are remarkably higher for women veterans, with roughly 20% diagnosed with PTSD.46,47 Anxiety and PTSD have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49

In 2014, a national VA multidisciplinary group focused on breast cancer prevention, detection, treatment, and research to address breast health in the growing population of women veterans. High-risk breast cancer screenings are not routinely carried out by the VA in primary care, women’s health, or oncology services. Furthermore, the recording of screening questionnaire results was not synchronized until a standard questionnaire was created and approved as a template by this group in the VA electronic medical record (EMR) in 2015.

Several prediction models can identify which women are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. The most commonly used risk assessment model, the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool (BCRAT), has been refined to include women of additional ethnicities (https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool).

This pilot project was launched to identify an effective manner to screen women veterans regarding their risk of developing breast cancer and refer them for chemoprevention education or genetic counseling as appropriate.

Methods

A high-risk breast cancer screening questionnaire based on the Gail BCRAT and including lifestyle questions was developed and included as a note template in the VA EMR. The James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY (JJPVAMC) and the Washington DC VA Medical Center (DCVAMC) ran a pilot study between 2015 and 2018 using this breast cancer screening questionnaire to collect data from women veterans. Quality Executive Committee and institutional review board approvals were granted respectively.

Eligibility criteria included women aged ≥ 35 years with no personal history of breast cancer. Most patients were self-referred, but participants also were recruited during VA Breast Cancer Awareness month events, health fairs, or at informational tables in the hospital lobbies. After completing the 20 multiple choice questionnaire with a study team member, either in person or over the phone, a 5-year and lifetime risk of invasive breast cancer was calculated using the Gail BCRAT. A woman is considered high risk and eligible for chemoprevention if her 5-year risk is > 1.66% or her lifetime risk is ≥ 20%. Eligibility for genetic counseling is based on the Breast Cancer Referral Screening Tool, which includes a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer and Jewish ancestry.

All patients were notified of their average or high risk status by a clinician. Those who were deemed to be average risk received a follow-up letter in the mail with instructions (eg, to follow-up with a yearly mammogram). Those who were deemed to be high risk for developing breast cancer were asked to come in for an appointment with the study principal investigator (a VA oncologist/breast cancer specialist) to discuss prevention options, further screening, or referrals to genetic counseling. Depending on a patient’s other health factors, a woman at high risk for developing breast cancer also may be a candidate for chemoprevention with tamoxifen, raloxifene, exemestane, anastrozole, or letrozole.

Data on the participant’s lifestyle, including exercise, diet, and smoking, were evaluated to determine whether these factors had an impact on risk status.

Results

The JJP and DC VAMCs screened 103 women veterans between 2015 and 2018. Four patients were excluded for nonveteran (spousal) status, leaving 99 women veterans with a mean age of 54 years. The most common self-reported races were Black (60%), non-Hispanic White (14%), and Hispanic or Latino (13%) (Table 1).

Women veterans in our study were nearly 3-times more likely than the general population were to receive a high-risk Gail Score/BCRAT (35% vs 13%, respectively).50,51 Of this subset, 46% had breast biopsies, and 86% had a positive family history. Thirty-one percent of Black women in our study were high risk, while nationally, 8.2 to 13.3% of Black women aged 50 to 59 years are considered high risk.50,51 Of the Black high-risk group with a high Gail/BCRAT score, 94% had a positive family history, and 33% had a history of breast biopsy (Table 2).

Of the 35 high-risk patients 26 (74%) patients accepted consultations for chemoprevention and 5 (19%) started chemoprevention. Of this high-risk group, 13 (37%) patients were referred for genetic counseling (Table 3).44 The prevalence of PTSD was present in 31% of high-risk women and 29% of the cohort (Figure).The lifestyle questions indicated that, among all participants, 79% had an overweight or obese body mass index; 58% exercised weekly; 51% consumed alcohol; 14% were smokers; and 21% consumed 3 to 4 servings of fruits/vegetables daily.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women.52 The number of women with breast cancer in the VHA has more than tripled from 1995 to 2012.1 The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in the general population is about 13%.50 This rate can be affected by risk factors including age, hormone exposure, family history, radiation exposure, and lifestyle factors, such as weight and alcohol use.6,52-56 In the United States, invasive breast cancer affects 1 in 8 women.50,52,57

Our screened population showed nearly 3 times as many women veterans were at an increased risk for breast cancer when compared with historical averages in US women. This difference may be based on a high rate of prior breast biopsies or positive family history, although a provocative study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database showed military women to have higher rates of breast cancer as well.9 Historically, Blacks are vastly understudied in clinical research with only 5% representation on a national level.5,58 The urban locations of both pilot sites (Washington, DC and Bronx, NY) allowed for the inclusion of minority patients in our study. We found that the rates of breast cancer in Black women veterans to be higher than seen nationally, possibly prompting further screening initiatives for this understudied population.

Our pilot study’s chemoprevention utilization (19%) was double the < 10% seen in the national population.33-35 The presence of a knowledgeable breast health practitioner to recruit study participants and offer personalized counseling to women veterans is a likely factor in overcoming barriers to chemopreventive acceptance. These participants may have been motivated to seek care for their high-risk status given a strong family history and prior breast biopsies.

Interestingly, a 3-fold higher PTSD rate was seen in this pilot population (29%) when compared with PTSD rates in the general female population (7-10%) and still one-third higher than the general population of women veterans (20%).45-47 Mental health, anxiety, and PTSD have been barriers to patients who sought treatment and have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49 Cancer screening can induce anxiety in patients, and it may be amplified in patients with PTSD. It was remarkable that although adherence with screening recommendations is decreased when PTSD is present, our patient population demonstrated a higher rate of screening adherence.

Women who are seen at the VA often use multiple clinical specialties, and their EMR can be accessed across VA medical centers nationwide. Therefore, identifying women veterans who meet screening criteria is easily attainable within the VA.

When comparing high-risk with average risk women, the lifestyle results (BMI, smoking history, exercise and consumption of fruits, vegetables and alcohol) were essentially the same. Lifestyle factors were similar to national population rates and were unlikely to impact risk levels.

Limitations

Study limitations included a high number of self-referrals and the large percentage of patients with a family history of breast cancer, making them more likely to seek screening. The higher-than-average risk of breast cancer may be driven by a high rate of breast biopsies and a strong family history. Lifestyle metrics could not be accurately compared to other national assessments of lifestyle factors due to the difference in data points that we used or the format of our questions.

Conclusions

As the number of women veterans increases and the incidence of breast cancer in women veterans rise, chemoprevention options should follow national guidelines. To our knowledge, this is the only oncology study with 60% Black women veterans. This study had a higher participation rate for Black women veterans than is typically seen in national research studies and shows the VA to be a germane source for further understanding of an understudied population that may benefit from increased screening for breast cancer.

A team-based, multidisciplinary model that meets the unique healthcare needs of women veterans results in a patient-centric delivery of care for assessing breast cancer risk status and prevention options. This model can be replicated nationally by directing primary care physicians and women’s health practitioners to a risk-assessment questionnaire and referring high-risk women for appropriate preventative care. Given that these results show chemoprevention adherence rates doubled those seen nationally, perhaps techniques used within this VA pilot study may be adapted to decrease breast cancer incidence nationally.

Since the rate of PTSD among women veterans is triple the national average, we would expect adherence rates to be lower in our patient cohort. However, the multidisciplinary approach we used in this study (eg, 1:1 consultation with oncologist; genetic counseling referrals; mental health support available), may have improved adherence rates. Perhaps the high rates of PTSD seen in the VA patient population can be a useful way to explore patient adherence rates in those with mental illness and medical conditions.

Future research with a larger cohort may lead to greater insight into the correlation between PTSD and adherence to treatment. Exploring the connection between breast cancer, epigenetics, and specific military service-related exposures could be an area of analysis among this veteran population exhibiting increased breast cancer rates. VAMCs are situated in rural, suburban, and urban locations across the United States and offers a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic patient population for inclusion in clinical investigations. Women veterans make up a small subpopulation of women in the United States, but it is worth considering VA patients as an untapped resource for research collaboration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Sanchez and Marissa Vallette, PhD, Breast Health Research Group. This research project was approved by the James J. Peters VA Medical Center Quality Executive Committee and the Washington, DC VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.