User login

NICE Rejects Bevacizumab/Capecitabine for Breast Cancer

The cost-effectiveness agency for England and Wales says that it will not recommend bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine to treat advanced metastatic breast cancer.

In new draft guidance issued April 18, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) cited insufficient evidence in support of the drug combination, one of two bevacizumab regimens licensed in the European Union for the first-line treatment of advanced metastatic breast cancer.

Roche’s bevacizumab (Avastin) is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks vascular endothelial growth factor, reducing blood flow to tumors. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration revoked bevacizumab’s breast cancer indications altogether in November 2011, citing an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio.

The European Medicines Agency did not follow suit, however. Bevacizumab is licensed in Europe in combination with paclitaxel and also with capecitabine, which is used when paclitaxel is judged inappropriate, for advanced metastatic breast cancer.

In February 2011, NICE rejected bevacizumab and paclitaxel for the same indication.

In announcing its decision on bevacizumab and capecitabine, NICE cited uncertainties about overall survival benefit in results from RIBBON-1, a randomized controlled trial of bevacizumab in 1,237 women with advanced breast cancer. In the capecitabine arm of the trial, 615 patients were randomized to capecitabine plus bevacizumab or capecitabine plus placebo.

Although the results showed that capecitabine and bevacizumab prolonged progression-free survival by 2.9 months compared with capecitabine monotherapy, it remained unclear whether that benefit translated into an improvement in overall survival, NICE said, because so many patients on monotherapy crossed over to bevacizumab in the trial’s open-label postprogression phase.

NICE cited in its negative guidance the fact that no quality of life data had been collected in the trial, and that serious adverse reactions were higher with bevacizumab plus capecitabine (36.6%) than with capecitabine plus placebo (22.9%). "In addition, the number of patients with hypertension, proteinuria, sensory neuropathy, and venous thromboembolic events was higher with bevacizumab plus capecitabine compared with capecitabine plus placebo," NICE said in an April 18 press statement about its decision. "The Committee concluded that bevacizumab plus capecitabine had a less favorable toxicity profile than capecitabine plus placebo."

Finally, as in all NICE decisions, there was the question of cost. The manufacturer’s best-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for bevacizumab plus capecitabine was £82,000 (U.S.$131,400) per quality-adjusted life year gained, and this only for a subgroup of patients. The ICER placed bevacizumab firmly out of NICE’s cost-effectiveness range.

Bevacizumab, which is administered by intravenous infusion, is dosed at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks, amounting, NICE said, to an average monthly cost of around £3,689 (U.S.$5,913) per patient.

The cost-effectiveness agency for England and Wales says that it will not recommend bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine to treat advanced metastatic breast cancer.

In new draft guidance issued April 18, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) cited insufficient evidence in support of the drug combination, one of two bevacizumab regimens licensed in the European Union for the first-line treatment of advanced metastatic breast cancer.

Roche’s bevacizumab (Avastin) is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks vascular endothelial growth factor, reducing blood flow to tumors. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration revoked bevacizumab’s breast cancer indications altogether in November 2011, citing an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio.

The European Medicines Agency did not follow suit, however. Bevacizumab is licensed in Europe in combination with paclitaxel and also with capecitabine, which is used when paclitaxel is judged inappropriate, for advanced metastatic breast cancer.

In February 2011, NICE rejected bevacizumab and paclitaxel for the same indication.

In announcing its decision on bevacizumab and capecitabine, NICE cited uncertainties about overall survival benefit in results from RIBBON-1, a randomized controlled trial of bevacizumab in 1,237 women with advanced breast cancer. In the capecitabine arm of the trial, 615 patients were randomized to capecitabine plus bevacizumab or capecitabine plus placebo.

Although the results showed that capecitabine and bevacizumab prolonged progression-free survival by 2.9 months compared with capecitabine monotherapy, it remained unclear whether that benefit translated into an improvement in overall survival, NICE said, because so many patients on monotherapy crossed over to bevacizumab in the trial’s open-label postprogression phase.

NICE cited in its negative guidance the fact that no quality of life data had been collected in the trial, and that serious adverse reactions were higher with bevacizumab plus capecitabine (36.6%) than with capecitabine plus placebo (22.9%). "In addition, the number of patients with hypertension, proteinuria, sensory neuropathy, and venous thromboembolic events was higher with bevacizumab plus capecitabine compared with capecitabine plus placebo," NICE said in an April 18 press statement about its decision. "The Committee concluded that bevacizumab plus capecitabine had a less favorable toxicity profile than capecitabine plus placebo."

Finally, as in all NICE decisions, there was the question of cost. The manufacturer’s best-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for bevacizumab plus capecitabine was £82,000 (U.S.$131,400) per quality-adjusted life year gained, and this only for a subgroup of patients. The ICER placed bevacizumab firmly out of NICE’s cost-effectiveness range.

Bevacizumab, which is administered by intravenous infusion, is dosed at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks, amounting, NICE said, to an average monthly cost of around £3,689 (U.S.$5,913) per patient.

The cost-effectiveness agency for England and Wales says that it will not recommend bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine to treat advanced metastatic breast cancer.

In new draft guidance issued April 18, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) cited insufficient evidence in support of the drug combination, one of two bevacizumab regimens licensed in the European Union for the first-line treatment of advanced metastatic breast cancer.

Roche’s bevacizumab (Avastin) is a humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks vascular endothelial growth factor, reducing blood flow to tumors. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration revoked bevacizumab’s breast cancer indications altogether in November 2011, citing an unfavorable risk-benefit ratio.

The European Medicines Agency did not follow suit, however. Bevacizumab is licensed in Europe in combination with paclitaxel and also with capecitabine, which is used when paclitaxel is judged inappropriate, for advanced metastatic breast cancer.

In February 2011, NICE rejected bevacizumab and paclitaxel for the same indication.

In announcing its decision on bevacizumab and capecitabine, NICE cited uncertainties about overall survival benefit in results from RIBBON-1, a randomized controlled trial of bevacizumab in 1,237 women with advanced breast cancer. In the capecitabine arm of the trial, 615 patients were randomized to capecitabine plus bevacizumab or capecitabine plus placebo.

Although the results showed that capecitabine and bevacizumab prolonged progression-free survival by 2.9 months compared with capecitabine monotherapy, it remained unclear whether that benefit translated into an improvement in overall survival, NICE said, because so many patients on monotherapy crossed over to bevacizumab in the trial’s open-label postprogression phase.

NICE cited in its negative guidance the fact that no quality of life data had been collected in the trial, and that serious adverse reactions were higher with bevacizumab plus capecitabine (36.6%) than with capecitabine plus placebo (22.9%). "In addition, the number of patients with hypertension, proteinuria, sensory neuropathy, and venous thromboembolic events was higher with bevacizumab plus capecitabine compared with capecitabine plus placebo," NICE said in an April 18 press statement about its decision. "The Committee concluded that bevacizumab plus capecitabine had a less favorable toxicity profile than capecitabine plus placebo."

Finally, as in all NICE decisions, there was the question of cost. The manufacturer’s best-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for bevacizumab plus capecitabine was £82,000 (U.S.$131,400) per quality-adjusted life year gained, and this only for a subgroup of patients. The ICER placed bevacizumab firmly out of NICE’s cost-effectiveness range.

Bevacizumab, which is administered by intravenous infusion, is dosed at 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks, amounting, NICE said, to an average monthly cost of around £3,689 (U.S.$5,913) per patient.

Trastuzumab Raises Cardiotoxicity Fivefold in Breast Cancer Patients

The risk of cardiotoxicity is five times higher in breast cancer patients given trastuzumab than in those receiving a standard chemotherapy regimen alone, according to a new systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration.

The review found that regimens containing trastuzumab (Herceptin) significantly increased congestive heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) decline, with relative risks of 5.11 and 1.83, respectively, in women with HER2-positive early and locally advanced breast cancer (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;4 [doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006243.pub2]).

However, trastuzumab regimens also significantly increased overall and disease-free survival, with hazard ratios of 0.66 and 0.60, respectively, noted Dr. Lorenzo Moja of the University of Milan and his coauthors. All these results were highly significant, with P values ranging from less than .0008 for risk of LVEF decline to less than .00001 for the others.

In a plain-language summary comparing trastuzumab-containing regimens with standard therapy alone in 1,000 women, the investigators wrote that 33 more women would have their lives prolonged with trastuzumab (933 women vs. 900 women with standard therapy alone). However, about 26 in 1,000 women taking trastuzumab would have serious heart toxicity, which is 21 more than the group treated with standard therapy alone.

Trastuzumab’s cardiotoxic effects have been well known, but the magnitude of the effect reported in the systematic review may be larger than what people have thought, commented Dr. Daniel J. Lenihan, director of clinical research in the cardiovascular medicine division at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., in an interview.

And that risk may be even greater in the world outside of clinical studies, said Dr. Melinda Telli of Stanford (Calif.) University. The patients in the studies included in the systematic review were younger, and none had baseline cardiac disease, observed Dr. Telli, also in an interview.

Another issue: In practice, oncologists are offering trastuzumab to women at lower risk for cancer recurrence than those in the trials. Thus, she said, "it’s more likely the risks are underestimated in this Cochrane review."

Although the data in the systematic review were previously published, having them encapsulated – along with a number of scenarios outlining potential risks and benefits in women with different cancer recurrence and cardiac risk factors – is a significant addition to the literature, said Dr. Telli.

Cochrane reviews are known for being thorough and balanced. This review began by looking at about 3,900 studies; after applying exclusion criteria, the list was winnowed down to 35 publications that covered 8 randomized controlled clinical trials enrolling 11,991 women. A little more than 7,000 women were assigned to a trastuzumab-containing arm, and 4,971 women to a regimen without trastuzumab. The median age in the trials was 49 years. Pre- and postmenopausal women were included, but those with metastatic disease or preexisting heart conditions were excluded.

The review concluded that high-risk women with few cardiac risk factors would benefit from trastuzumab, while those at lower risk "must be carefully evaluated," adding, "The oncologist should share the decision with the patient concerning whether and how to start the treatment."

Dr. Lenihan said he was concerned that the potential cardiotoxicity might cause oncologists to steer away from trastuzumab. He is a proponent of a multidisciplinary team that involves a cardiologist at the outset of therapy.

If cardiac effects develop, "the key is not to ignore it, but to pay attention," said Dr. Lenihan, who is also president of the International CardiOncology Society USA/Canada.

Early identification enables rapid treatment, which can stabilize or correct the heart issues, he said. That allows patients to return to their cancer therapy.

Dr. Lenihan and his colleagues at Vanderbilt University are currently conducting a study testing various cardiac biomarkers to detect toxicity during chemotherapy.

It is still unknown, however, whether the cardiotoxicity that develops during therapy is ultimately reversible, or becomes a lifelong issue. While the ejection fraction may recover after withdrawal of trastuzumab, at least one study – the Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial – has shown that some women had long-term loss of heart muscle cells, said Dr. Telli.

"So we know that the heart is taking a hit," she said, adding that the trastuzumab damage is not "some sort of reversible thing."

The key, she said, is for oncologists to weigh the risks and benefits individually in each patient.

A targeted therapy, trastuzumab is approved for treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer and of metastatic HER2-positive adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. About 20% of tumors in women with early breast cancer are HER2-positive.

Dr. Telli reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lenihan reported receiving consulting fees from Roche and AstraZeneca and research support from Acorda.

The risk of cardiotoxicity is five times higher in breast cancer patients given trastuzumab than in those receiving a standard chemotherapy regimen alone, according to a new systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration.

The review found that regimens containing trastuzumab (Herceptin) significantly increased congestive heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) decline, with relative risks of 5.11 and 1.83, respectively, in women with HER2-positive early and locally advanced breast cancer (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;4 [doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006243.pub2]).

However, trastuzumab regimens also significantly increased overall and disease-free survival, with hazard ratios of 0.66 and 0.60, respectively, noted Dr. Lorenzo Moja of the University of Milan and his coauthors. All these results were highly significant, with P values ranging from less than .0008 for risk of LVEF decline to less than .00001 for the others.

In a plain-language summary comparing trastuzumab-containing regimens with standard therapy alone in 1,000 women, the investigators wrote that 33 more women would have their lives prolonged with trastuzumab (933 women vs. 900 women with standard therapy alone). However, about 26 in 1,000 women taking trastuzumab would have serious heart toxicity, which is 21 more than the group treated with standard therapy alone.

Trastuzumab’s cardiotoxic effects have been well known, but the magnitude of the effect reported in the systematic review may be larger than what people have thought, commented Dr. Daniel J. Lenihan, director of clinical research in the cardiovascular medicine division at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., in an interview.

And that risk may be even greater in the world outside of clinical studies, said Dr. Melinda Telli of Stanford (Calif.) University. The patients in the studies included in the systematic review were younger, and none had baseline cardiac disease, observed Dr. Telli, also in an interview.

Another issue: In practice, oncologists are offering trastuzumab to women at lower risk for cancer recurrence than those in the trials. Thus, she said, "it’s more likely the risks are underestimated in this Cochrane review."

Although the data in the systematic review were previously published, having them encapsulated – along with a number of scenarios outlining potential risks and benefits in women with different cancer recurrence and cardiac risk factors – is a significant addition to the literature, said Dr. Telli.

Cochrane reviews are known for being thorough and balanced. This review began by looking at about 3,900 studies; after applying exclusion criteria, the list was winnowed down to 35 publications that covered 8 randomized controlled clinical trials enrolling 11,991 women. A little more than 7,000 women were assigned to a trastuzumab-containing arm, and 4,971 women to a regimen without trastuzumab. The median age in the trials was 49 years. Pre- and postmenopausal women were included, but those with metastatic disease or preexisting heart conditions were excluded.

The review concluded that high-risk women with few cardiac risk factors would benefit from trastuzumab, while those at lower risk "must be carefully evaluated," adding, "The oncologist should share the decision with the patient concerning whether and how to start the treatment."

Dr. Lenihan said he was concerned that the potential cardiotoxicity might cause oncologists to steer away from trastuzumab. He is a proponent of a multidisciplinary team that involves a cardiologist at the outset of therapy.

If cardiac effects develop, "the key is not to ignore it, but to pay attention," said Dr. Lenihan, who is also president of the International CardiOncology Society USA/Canada.

Early identification enables rapid treatment, which can stabilize or correct the heart issues, he said. That allows patients to return to their cancer therapy.

Dr. Lenihan and his colleagues at Vanderbilt University are currently conducting a study testing various cardiac biomarkers to detect toxicity during chemotherapy.

It is still unknown, however, whether the cardiotoxicity that develops during therapy is ultimately reversible, or becomes a lifelong issue. While the ejection fraction may recover after withdrawal of trastuzumab, at least one study – the Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial – has shown that some women had long-term loss of heart muscle cells, said Dr. Telli.

"So we know that the heart is taking a hit," she said, adding that the trastuzumab damage is not "some sort of reversible thing."

The key, she said, is for oncologists to weigh the risks and benefits individually in each patient.

A targeted therapy, trastuzumab is approved for treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer and of metastatic HER2-positive adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. About 20% of tumors in women with early breast cancer are HER2-positive.

Dr. Telli reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lenihan reported receiving consulting fees from Roche and AstraZeneca and research support from Acorda.

The risk of cardiotoxicity is five times higher in breast cancer patients given trastuzumab than in those receiving a standard chemotherapy regimen alone, according to a new systematic review from the Cochrane Collaboration.

The review found that regimens containing trastuzumab (Herceptin) significantly increased congestive heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) decline, with relative risks of 5.11 and 1.83, respectively, in women with HER2-positive early and locally advanced breast cancer (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;4 [doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006243.pub2]).

However, trastuzumab regimens also significantly increased overall and disease-free survival, with hazard ratios of 0.66 and 0.60, respectively, noted Dr. Lorenzo Moja of the University of Milan and his coauthors. All these results were highly significant, with P values ranging from less than .0008 for risk of LVEF decline to less than .00001 for the others.

In a plain-language summary comparing trastuzumab-containing regimens with standard therapy alone in 1,000 women, the investigators wrote that 33 more women would have their lives prolonged with trastuzumab (933 women vs. 900 women with standard therapy alone). However, about 26 in 1,000 women taking trastuzumab would have serious heart toxicity, which is 21 more than the group treated with standard therapy alone.

Trastuzumab’s cardiotoxic effects have been well known, but the magnitude of the effect reported in the systematic review may be larger than what people have thought, commented Dr. Daniel J. Lenihan, director of clinical research in the cardiovascular medicine division at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., in an interview.

And that risk may be even greater in the world outside of clinical studies, said Dr. Melinda Telli of Stanford (Calif.) University. The patients in the studies included in the systematic review were younger, and none had baseline cardiac disease, observed Dr. Telli, also in an interview.

Another issue: In practice, oncologists are offering trastuzumab to women at lower risk for cancer recurrence than those in the trials. Thus, she said, "it’s more likely the risks are underestimated in this Cochrane review."

Although the data in the systematic review were previously published, having them encapsulated – along with a number of scenarios outlining potential risks and benefits in women with different cancer recurrence and cardiac risk factors – is a significant addition to the literature, said Dr. Telli.

Cochrane reviews are known for being thorough and balanced. This review began by looking at about 3,900 studies; after applying exclusion criteria, the list was winnowed down to 35 publications that covered 8 randomized controlled clinical trials enrolling 11,991 women. A little more than 7,000 women were assigned to a trastuzumab-containing arm, and 4,971 women to a regimen without trastuzumab. The median age in the trials was 49 years. Pre- and postmenopausal women were included, but those with metastatic disease or preexisting heart conditions were excluded.

The review concluded that high-risk women with few cardiac risk factors would benefit from trastuzumab, while those at lower risk "must be carefully evaluated," adding, "The oncologist should share the decision with the patient concerning whether and how to start the treatment."

Dr. Lenihan said he was concerned that the potential cardiotoxicity might cause oncologists to steer away from trastuzumab. He is a proponent of a multidisciplinary team that involves a cardiologist at the outset of therapy.

If cardiac effects develop, "the key is not to ignore it, but to pay attention," said Dr. Lenihan, who is also president of the International CardiOncology Society USA/Canada.

Early identification enables rapid treatment, which can stabilize or correct the heart issues, he said. That allows patients to return to their cancer therapy.

Dr. Lenihan and his colleagues at Vanderbilt University are currently conducting a study testing various cardiac biomarkers to detect toxicity during chemotherapy.

It is still unknown, however, whether the cardiotoxicity that develops during therapy is ultimately reversible, or becomes a lifelong issue. While the ejection fraction may recover after withdrawal of trastuzumab, at least one study – the Herceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial – has shown that some women had long-term loss of heart muscle cells, said Dr. Telli.

"So we know that the heart is taking a hit," she said, adding that the trastuzumab damage is not "some sort of reversible thing."

The key, she said, is for oncologists to weigh the risks and benefits individually in each patient.

A targeted therapy, trastuzumab is approved for treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer and of metastatic HER2-positive adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. About 20% of tumors in women with early breast cancer are HER2-positive.

Dr. Telli reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lenihan reported receiving consulting fees from Roche and AstraZeneca and research support from Acorda.

FROM THE COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

Use of Ultrasound Expands Across Surgical Specialties

Ultrasound, a technology that was once mainly in the purview of radiologists, is becoming an integral part of the surgeon’s toolbox.

Across specialties, an increasing number of surgeons are incorporating ultrasound into their practices, whether in the office or in the operating room, especially as procedures become less invasive.

The once-cumbersome machines have gotten smaller over the past three decades, the technology has improved dramatically, and – compared with some other types of imaging – ultrasound is more cost-effective and affordable, experts say.

"It’s a technology that I think is going to expand in use," said Dr. Jay K. Harness, an early adopter of ultrasound in breast surgery and coauthor of the textbook "Ultrasound in Surgical Practice." "I started using it in the 1990s, and it’s like we’ve gone from analog TV to digital."

Dr. Heidi Frankel, chair of American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) National Ultrasound Faculty, compared the developments in use of ultrasound in surgery to laparoscopy.

"Ultimately, the patients and the market pushed the need for it," said Dr. Frankel, professor of surgery at University of Maryland Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore. "Surgeons who didn’t do it had to learn to do it, and it became part of surgical training. I suspect the same thing is going to happen with ultrasound."

And while training and certification requirements vary widely, the surgeons currently using ultrasound predict that guidelines may ultimately become somewhat standardized within and across specialties.

Breast Surgery

Dr. Harness, who is also a member of the ACS National Ultrasound Faculty and the past-president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBS), was among the first to incorporate ultrasound into his practice. Today, he said, "for the contemporary breast surgeon, [ultrasound] is a fundamental tool ... Ultrasound is our stethoscope."

In breast surgery, ultrasound is an adjunctive tool for the physical exam, said Dr. Harness. It is used for diagnostic biopsy, and it can speed up the diagnostic process. Ultrasound also is used in the operating room, notably for procedures such as lumpectomies. And finally, ultrasound can help guide the placement of partial breast brachyradiation therapy devices.

Breast surgeons can obtain ultrasound certification through ASBS, although becoming certified is not a requirement. "A major goal of the Society’s breast ultrasound certification program is to improve the quality of care for patients with breast disease by encouraging education and training to advance expertise and clinical competency for surgeons who use ultrasound and ultrasound-guided procedures in their practices," according to the ASBS website.

Dr. Harness said that ultrasound combined with other imaging techniques such as MRI provides the most complete imaging possible, given that there’s no single technology that captures everything.

Abdominal Surgery

In the 1980s, not many surgeons used ultrasound in their day-to-day practice and there were few publications on the topic, said Dr. Junji Machi. At that time, x-rays were commonly used to check areas such as the bile duct for stones. "But, it was cumbersome and took 15-30 minutes. So we used ultrasound instead. It was quicker, and the results were accurate," said Dr. Machi, professor of surgery at University of Hawaii, and director of the Abdominal Ultrasound Module at the ACS.

Dr. Machi has published a number of studies on cases and findings, and he uses ultrasound, especially during liver, biliary, and pancreatic surgery.

"For liver surgery, intraoperative ultrasound is a must," he said. "Without it, we consider the procedure suboptimal, because we may miss lesions and cannot perform the best operations."

Among the indications for ultrasound use in abdominal surgery were laparoscopic procedures, which were introduced in the 1990s, he said. "You can see, but not touch, the tissue," said Dr. Machi. "So we needed something to evaluate under the surface. ... With ultrasound, we can see without much dissection."

Surgeons could be discouraged from using ultrasound because the learning curve is steep (usually several months’ experience is needed) and because the equipment is relatively expensive. Yet, "once you learn it, it’s much more cost effective," he said, adding that this imaging technique does not expose the patient and operative team to radiation.

There’s no specialty limitation in the use of ultrasound, and abdominal surgeons can perform it once they master ultrasound. The ACS ultrasound course is an excellent way to learn, said Dr. Machi. Surgeons receive a certificate upon completion of a course.

Indeed, "the training issues are really paramount," said Dr. Ellen Hagopian, who did her liver training in France, and studied with radiologists and surgeons. Ultrasound is used much more frequently in Europe than in the United States, she said. "I sit on the education and training committee of Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association [AHPBA], and I think ultrasound training throughout the fellowship programs needs to be more consistent."

Dr. Hagopian, who sits on ACS’s National Ultrasound Faculty board, coordinated and taught the first advanced ultrasound course in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery at the AHPBA Annual Meeting in March. The course will be given again this year at the ACS Clinical Congress in San Francisco. Surgeons receive a certification of completion.

"Feedback and interest at AHPBA was excellent," said Dr. Hagopian. "There were many more surgeons who wanted to take the course than we could accommodate." She anticipates that similar interest will be shown during the ACS Clinical Congress.

Head and Neck Surgery

"Basically, the best way to evaluate the thyroid gland is ultrasound," said Dr. Robert Sofferman, an otolaryngologist who does thyroid and parathyroid surgery as part of his practice. "It’s cheaper and incredibly accurate."

Dr. Sofferman, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of Vermont in Burlington, said that some 15 years ago, ultrasound machines were too big and didn’t have good resolution. But over time, the equipment has become smaller, better, portable, and less expensive, he said. He predicts that the machines will eventually shrink to the size of an iPad.

"We operate in the neck on a daily basis," said Dr. Sofferman. "Ultrasound is very helpful for us. I couldn’t do my work without it."

Having the imaging available in the office is also convenient for the patients. "We arrange everything before the patient comes in. We do the physical exam. We do the ultrasound exam. We do ultrasound-guided biopsy, so the patient is done in one visit."

He said ultrasound can be used to evaluate the size and characteristics of a tumor before deciding whether to operate or to monitor the tumor’s response to treatment. "It’s a technology that has some advantages. It’s an extension of our physical examination."

It also comes with a few drawbacks. Aside from the price, which can be upwards of $30,000, ultrasound can slow down the day, and it does have a moderate learning curve, according to Dr. Sofferman.

Neither the ACS nor American Association of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) require certification for the use of ultrasound. However, the ACS offers training in thyroid/parathyroid ultrasound to all surgeons who do neck surgery, either during the annual Clinical Congress or in other courses. Participants who complete training receive certification from the ACS.

Vascular Surgery

Ultrasound is a major component of vascular surgery training and practice, and many vascular surgeons have obtained the Registered Vascular Technologist (RVT) credential from the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography (ARDMS.)

While the RVT credential has been available since the 1980s, the ARDMS introduced the Registered Physician in Vascular Interpretation (RPVI) credential in 2006 to provide a certification process that focuses more on interpretation of vascular ultrasound tests than on performing the examinations. The RPVI credential is open to all qualified physicians and is not restricted to vascular surgeons.

"The advantage of the RPVI is that it is a national, standardized credential that is available to all physicians with an interest in vascular testing," said Dr. Gene Zierler, a member of the National Ultrasound Faculty and professor of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle. "So that means it can document expertise in vascular ultrasound across multiple specialties and training programs."

Starting in 2014, the RPVI will be a requirement for vascular surgery board certification, a decision supported by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Trauma Surgery

Ultrasound is the quickest and most reliable diagnostic tool under emergency conditions, according to Dr. Frankel.

"We work with very time-sensitive injuries. Ultrasound in my specialty is absolutely necessary. We image trauma patients this way. We can’t wait for a radiologist to come in," she said.

Dr. Frankel, who began using ultrasound in 1994, echoed her colleagues who said that technology has improved over time. Her hospital has begun using ultrasound in the intensive care unit, and "our residents are starting to use it early on. And medical students are picking it up," she said.

Whether surgeons are permitted to use ultrasound in the hospital varies by system or institution. Hospitals may require board-certified surgeons to perform a certain number of ultrasound procedures before granting them certification or to show certain certification or credentialing in ultrasound, experts said.

"There’s no science [to show] how many of these procedures I should have done to get credentialed by the hospital to use ultrasound," Dr. Frankel said.

She and other surgeons predicted that the individual surgical societies will ultimately specify the training, certification, or accreditation requirements for performing ultrasound. In the meantime, ultrasound seems to be finding its place in surgery, and surgeons who have been using it say they wouldn’t practice without it.

"It adds to the joy of practicing medicine," said Dr. Sofferman. "It makes it enjoyable for us to be able to see everything. That’s a definite advantage. I couldn’t be as efficient and as accurate without it."

None of the surgeons reported any relevant disclosures.

Ultrasound, a technology that was once mainly in the purview of radiologists, is becoming an integral part of the surgeon’s toolbox.

Across specialties, an increasing number of surgeons are incorporating ultrasound into their practices, whether in the office or in the operating room, especially as procedures become less invasive.

The once-cumbersome machines have gotten smaller over the past three decades, the technology has improved dramatically, and – compared with some other types of imaging – ultrasound is more cost-effective and affordable, experts say.

"It’s a technology that I think is going to expand in use," said Dr. Jay K. Harness, an early adopter of ultrasound in breast surgery and coauthor of the textbook "Ultrasound in Surgical Practice." "I started using it in the 1990s, and it’s like we’ve gone from analog TV to digital."

Dr. Heidi Frankel, chair of American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) National Ultrasound Faculty, compared the developments in use of ultrasound in surgery to laparoscopy.

"Ultimately, the patients and the market pushed the need for it," said Dr. Frankel, professor of surgery at University of Maryland Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore. "Surgeons who didn’t do it had to learn to do it, and it became part of surgical training. I suspect the same thing is going to happen with ultrasound."

And while training and certification requirements vary widely, the surgeons currently using ultrasound predict that guidelines may ultimately become somewhat standardized within and across specialties.

Breast Surgery

Dr. Harness, who is also a member of the ACS National Ultrasound Faculty and the past-president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBS), was among the first to incorporate ultrasound into his practice. Today, he said, "for the contemporary breast surgeon, [ultrasound] is a fundamental tool ... Ultrasound is our stethoscope."

In breast surgery, ultrasound is an adjunctive tool for the physical exam, said Dr. Harness. It is used for diagnostic biopsy, and it can speed up the diagnostic process. Ultrasound also is used in the operating room, notably for procedures such as lumpectomies. And finally, ultrasound can help guide the placement of partial breast brachyradiation therapy devices.

Breast surgeons can obtain ultrasound certification through ASBS, although becoming certified is not a requirement. "A major goal of the Society’s breast ultrasound certification program is to improve the quality of care for patients with breast disease by encouraging education and training to advance expertise and clinical competency for surgeons who use ultrasound and ultrasound-guided procedures in their practices," according to the ASBS website.

Dr. Harness said that ultrasound combined with other imaging techniques such as MRI provides the most complete imaging possible, given that there’s no single technology that captures everything.

Abdominal Surgery

In the 1980s, not many surgeons used ultrasound in their day-to-day practice and there were few publications on the topic, said Dr. Junji Machi. At that time, x-rays were commonly used to check areas such as the bile duct for stones. "But, it was cumbersome and took 15-30 minutes. So we used ultrasound instead. It was quicker, and the results were accurate," said Dr. Machi, professor of surgery at University of Hawaii, and director of the Abdominal Ultrasound Module at the ACS.

Dr. Machi has published a number of studies on cases and findings, and he uses ultrasound, especially during liver, biliary, and pancreatic surgery.

"For liver surgery, intraoperative ultrasound is a must," he said. "Without it, we consider the procedure suboptimal, because we may miss lesions and cannot perform the best operations."

Among the indications for ultrasound use in abdominal surgery were laparoscopic procedures, which were introduced in the 1990s, he said. "You can see, but not touch, the tissue," said Dr. Machi. "So we needed something to evaluate under the surface. ... With ultrasound, we can see without much dissection."

Surgeons could be discouraged from using ultrasound because the learning curve is steep (usually several months’ experience is needed) and because the equipment is relatively expensive. Yet, "once you learn it, it’s much more cost effective," he said, adding that this imaging technique does not expose the patient and operative team to radiation.

There’s no specialty limitation in the use of ultrasound, and abdominal surgeons can perform it once they master ultrasound. The ACS ultrasound course is an excellent way to learn, said Dr. Machi. Surgeons receive a certificate upon completion of a course.

Indeed, "the training issues are really paramount," said Dr. Ellen Hagopian, who did her liver training in France, and studied with radiologists and surgeons. Ultrasound is used much more frequently in Europe than in the United States, she said. "I sit on the education and training committee of Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association [AHPBA], and I think ultrasound training throughout the fellowship programs needs to be more consistent."

Dr. Hagopian, who sits on ACS’s National Ultrasound Faculty board, coordinated and taught the first advanced ultrasound course in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery at the AHPBA Annual Meeting in March. The course will be given again this year at the ACS Clinical Congress in San Francisco. Surgeons receive a certification of completion.

"Feedback and interest at AHPBA was excellent," said Dr. Hagopian. "There were many more surgeons who wanted to take the course than we could accommodate." She anticipates that similar interest will be shown during the ACS Clinical Congress.

Head and Neck Surgery

"Basically, the best way to evaluate the thyroid gland is ultrasound," said Dr. Robert Sofferman, an otolaryngologist who does thyroid and parathyroid surgery as part of his practice. "It’s cheaper and incredibly accurate."

Dr. Sofferman, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of Vermont in Burlington, said that some 15 years ago, ultrasound machines were too big and didn’t have good resolution. But over time, the equipment has become smaller, better, portable, and less expensive, he said. He predicts that the machines will eventually shrink to the size of an iPad.

"We operate in the neck on a daily basis," said Dr. Sofferman. "Ultrasound is very helpful for us. I couldn’t do my work without it."

Having the imaging available in the office is also convenient for the patients. "We arrange everything before the patient comes in. We do the physical exam. We do the ultrasound exam. We do ultrasound-guided biopsy, so the patient is done in one visit."

He said ultrasound can be used to evaluate the size and characteristics of a tumor before deciding whether to operate or to monitor the tumor’s response to treatment. "It’s a technology that has some advantages. It’s an extension of our physical examination."

It also comes with a few drawbacks. Aside from the price, which can be upwards of $30,000, ultrasound can slow down the day, and it does have a moderate learning curve, according to Dr. Sofferman.

Neither the ACS nor American Association of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) require certification for the use of ultrasound. However, the ACS offers training in thyroid/parathyroid ultrasound to all surgeons who do neck surgery, either during the annual Clinical Congress or in other courses. Participants who complete training receive certification from the ACS.

Vascular Surgery

Ultrasound is a major component of vascular surgery training and practice, and many vascular surgeons have obtained the Registered Vascular Technologist (RVT) credential from the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography (ARDMS.)

While the RVT credential has been available since the 1980s, the ARDMS introduced the Registered Physician in Vascular Interpretation (RPVI) credential in 2006 to provide a certification process that focuses more on interpretation of vascular ultrasound tests than on performing the examinations. The RPVI credential is open to all qualified physicians and is not restricted to vascular surgeons.

"The advantage of the RPVI is that it is a national, standardized credential that is available to all physicians with an interest in vascular testing," said Dr. Gene Zierler, a member of the National Ultrasound Faculty and professor of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle. "So that means it can document expertise in vascular ultrasound across multiple specialties and training programs."

Starting in 2014, the RPVI will be a requirement for vascular surgery board certification, a decision supported by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Trauma Surgery

Ultrasound is the quickest and most reliable diagnostic tool under emergency conditions, according to Dr. Frankel.

"We work with very time-sensitive injuries. Ultrasound in my specialty is absolutely necessary. We image trauma patients this way. We can’t wait for a radiologist to come in," she said.

Dr. Frankel, who began using ultrasound in 1994, echoed her colleagues who said that technology has improved over time. Her hospital has begun using ultrasound in the intensive care unit, and "our residents are starting to use it early on. And medical students are picking it up," she said.

Whether surgeons are permitted to use ultrasound in the hospital varies by system or institution. Hospitals may require board-certified surgeons to perform a certain number of ultrasound procedures before granting them certification or to show certain certification or credentialing in ultrasound, experts said.

"There’s no science [to show] how many of these procedures I should have done to get credentialed by the hospital to use ultrasound," Dr. Frankel said.

She and other surgeons predicted that the individual surgical societies will ultimately specify the training, certification, or accreditation requirements for performing ultrasound. In the meantime, ultrasound seems to be finding its place in surgery, and surgeons who have been using it say they wouldn’t practice without it.

"It adds to the joy of practicing medicine," said Dr. Sofferman. "It makes it enjoyable for us to be able to see everything. That’s a definite advantage. I couldn’t be as efficient and as accurate without it."

None of the surgeons reported any relevant disclosures.

Ultrasound, a technology that was once mainly in the purview of radiologists, is becoming an integral part of the surgeon’s toolbox.

Across specialties, an increasing number of surgeons are incorporating ultrasound into their practices, whether in the office or in the operating room, especially as procedures become less invasive.

The once-cumbersome machines have gotten smaller over the past three decades, the technology has improved dramatically, and – compared with some other types of imaging – ultrasound is more cost-effective and affordable, experts say.

"It’s a technology that I think is going to expand in use," said Dr. Jay K. Harness, an early adopter of ultrasound in breast surgery and coauthor of the textbook "Ultrasound in Surgical Practice." "I started using it in the 1990s, and it’s like we’ve gone from analog TV to digital."

Dr. Heidi Frankel, chair of American College of Surgeons’ (ACS) National Ultrasound Faculty, compared the developments in use of ultrasound in surgery to laparoscopy.

"Ultimately, the patients and the market pushed the need for it," said Dr. Frankel, professor of surgery at University of Maryland Shock Trauma Center, Baltimore. "Surgeons who didn’t do it had to learn to do it, and it became part of surgical training. I suspect the same thing is going to happen with ultrasound."

And while training and certification requirements vary widely, the surgeons currently using ultrasound predict that guidelines may ultimately become somewhat standardized within and across specialties.

Breast Surgery

Dr. Harness, who is also a member of the ACS National Ultrasound Faculty and the past-president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBS), was among the first to incorporate ultrasound into his practice. Today, he said, "for the contemporary breast surgeon, [ultrasound] is a fundamental tool ... Ultrasound is our stethoscope."

In breast surgery, ultrasound is an adjunctive tool for the physical exam, said Dr. Harness. It is used for diagnostic biopsy, and it can speed up the diagnostic process. Ultrasound also is used in the operating room, notably for procedures such as lumpectomies. And finally, ultrasound can help guide the placement of partial breast brachyradiation therapy devices.

Breast surgeons can obtain ultrasound certification through ASBS, although becoming certified is not a requirement. "A major goal of the Society’s breast ultrasound certification program is to improve the quality of care for patients with breast disease by encouraging education and training to advance expertise and clinical competency for surgeons who use ultrasound and ultrasound-guided procedures in their practices," according to the ASBS website.

Dr. Harness said that ultrasound combined with other imaging techniques such as MRI provides the most complete imaging possible, given that there’s no single technology that captures everything.

Abdominal Surgery

In the 1980s, not many surgeons used ultrasound in their day-to-day practice and there were few publications on the topic, said Dr. Junji Machi. At that time, x-rays were commonly used to check areas such as the bile duct for stones. "But, it was cumbersome and took 15-30 minutes. So we used ultrasound instead. It was quicker, and the results were accurate," said Dr. Machi, professor of surgery at University of Hawaii, and director of the Abdominal Ultrasound Module at the ACS.

Dr. Machi has published a number of studies on cases and findings, and he uses ultrasound, especially during liver, biliary, and pancreatic surgery.

"For liver surgery, intraoperative ultrasound is a must," he said. "Without it, we consider the procedure suboptimal, because we may miss lesions and cannot perform the best operations."

Among the indications for ultrasound use in abdominal surgery were laparoscopic procedures, which were introduced in the 1990s, he said. "You can see, but not touch, the tissue," said Dr. Machi. "So we needed something to evaluate under the surface. ... With ultrasound, we can see without much dissection."

Surgeons could be discouraged from using ultrasound because the learning curve is steep (usually several months’ experience is needed) and because the equipment is relatively expensive. Yet, "once you learn it, it’s much more cost effective," he said, adding that this imaging technique does not expose the patient and operative team to radiation.

There’s no specialty limitation in the use of ultrasound, and abdominal surgeons can perform it once they master ultrasound. The ACS ultrasound course is an excellent way to learn, said Dr. Machi. Surgeons receive a certificate upon completion of a course.

Indeed, "the training issues are really paramount," said Dr. Ellen Hagopian, who did her liver training in France, and studied with radiologists and surgeons. Ultrasound is used much more frequently in Europe than in the United States, she said. "I sit on the education and training committee of Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association [AHPBA], and I think ultrasound training throughout the fellowship programs needs to be more consistent."

Dr. Hagopian, who sits on ACS’s National Ultrasound Faculty board, coordinated and taught the first advanced ultrasound course in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery at the AHPBA Annual Meeting in March. The course will be given again this year at the ACS Clinical Congress in San Francisco. Surgeons receive a certification of completion.

"Feedback and interest at AHPBA was excellent," said Dr. Hagopian. "There were many more surgeons who wanted to take the course than we could accommodate." She anticipates that similar interest will be shown during the ACS Clinical Congress.

Head and Neck Surgery

"Basically, the best way to evaluate the thyroid gland is ultrasound," said Dr. Robert Sofferman, an otolaryngologist who does thyroid and parathyroid surgery as part of his practice. "It’s cheaper and incredibly accurate."

Dr. Sofferman, professor emeritus of surgery at the University of Vermont in Burlington, said that some 15 years ago, ultrasound machines were too big and didn’t have good resolution. But over time, the equipment has become smaller, better, portable, and less expensive, he said. He predicts that the machines will eventually shrink to the size of an iPad.

"We operate in the neck on a daily basis," said Dr. Sofferman. "Ultrasound is very helpful for us. I couldn’t do my work without it."

Having the imaging available in the office is also convenient for the patients. "We arrange everything before the patient comes in. We do the physical exam. We do the ultrasound exam. We do ultrasound-guided biopsy, so the patient is done in one visit."

He said ultrasound can be used to evaluate the size and characteristics of a tumor before deciding whether to operate or to monitor the tumor’s response to treatment. "It’s a technology that has some advantages. It’s an extension of our physical examination."

It also comes with a few drawbacks. Aside from the price, which can be upwards of $30,000, ultrasound can slow down the day, and it does have a moderate learning curve, according to Dr. Sofferman.

Neither the ACS nor American Association of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) require certification for the use of ultrasound. However, the ACS offers training in thyroid/parathyroid ultrasound to all surgeons who do neck surgery, either during the annual Clinical Congress or in other courses. Participants who complete training receive certification from the ACS.

Vascular Surgery

Ultrasound is a major component of vascular surgery training and practice, and many vascular surgeons have obtained the Registered Vascular Technologist (RVT) credential from the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography (ARDMS.)

While the RVT credential has been available since the 1980s, the ARDMS introduced the Registered Physician in Vascular Interpretation (RPVI) credential in 2006 to provide a certification process that focuses more on interpretation of vascular ultrasound tests than on performing the examinations. The RPVI credential is open to all qualified physicians and is not restricted to vascular surgeons.

"The advantage of the RPVI is that it is a national, standardized credential that is available to all physicians with an interest in vascular testing," said Dr. Gene Zierler, a member of the National Ultrasound Faculty and professor of surgery at the University of Washington, Seattle. "So that means it can document expertise in vascular ultrasound across multiple specialties and training programs."

Starting in 2014, the RPVI will be a requirement for vascular surgery board certification, a decision supported by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

Trauma Surgery

Ultrasound is the quickest and most reliable diagnostic tool under emergency conditions, according to Dr. Frankel.

"We work with very time-sensitive injuries. Ultrasound in my specialty is absolutely necessary. We image trauma patients this way. We can’t wait for a radiologist to come in," she said.

Dr. Frankel, who began using ultrasound in 1994, echoed her colleagues who said that technology has improved over time. Her hospital has begun using ultrasound in the intensive care unit, and "our residents are starting to use it early on. And medical students are picking it up," she said.

Whether surgeons are permitted to use ultrasound in the hospital varies by system or institution. Hospitals may require board-certified surgeons to perform a certain number of ultrasound procedures before granting them certification or to show certain certification or credentialing in ultrasound, experts said.

"There’s no science [to show] how many of these procedures I should have done to get credentialed by the hospital to use ultrasound," Dr. Frankel said.

She and other surgeons predicted that the individual surgical societies will ultimately specify the training, certification, or accreditation requirements for performing ultrasound. In the meantime, ultrasound seems to be finding its place in surgery, and surgeons who have been using it say they wouldn’t practice without it.

"It adds to the joy of practicing medicine," said Dr. Sofferman. "It makes it enjoyable for us to be able to see everything. That’s a definite advantage. I couldn’t be as efficient and as accurate without it."

None of the surgeons reported any relevant disclosures.

NCCN: Skip ALND in Some Early Breast Cancer

Axillary lymph node dissection can be skipped in some early-stage breast cancer patients with minimal sentinel node involvement, as well as in those with negative findings on sentinel node biopsy, according to revised clinical practice guidelines issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The recommendation that no further axial surgery be considered for certain patients with only one or two involved sentinel lymph nodes reflects an upgrade of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline on sentinel node biopsy to a category 1 recommendation.

The change is based on the findings of recent prospective studies. In particular, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial, found no survival difference between early-stage breast cancer patients who underwent axillary lymph node dissection [ALND] and those who did not after one or two sentinel nodes were determined to be positive on biopsy (JAMA 2011;305:569-75).

The revised recommendation extends only to those patients with early-stage disease (tumor grades 1 or 2) who undergo breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiation and who have not received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, according to the guidelines. A primary objective is to reduce the risk of lymphedema associated with axillary lymph node dissection.

"In the absence of definitive data demonstrating superior survival from the performance of axillary lymph node dissection, patients who have particularly favorable tumors, patients for whom the selection of adjuvant systemic therapy is unlikely to be affected, for the elderly or those with serious comorbid conditions, the performance of axillary lymph node dissection may be considered optional," the guidelines advise.

The update was presented at the NCCN annual meeting in Hollywood, Fla. The Breast Cancer Panel lists potential conflict of interest disclosures on the NCCN website.

Axillary lymph node dissection can be skipped in some early-stage breast cancer patients with minimal sentinel node involvement, as well as in those with negative findings on sentinel node biopsy, according to revised clinical practice guidelines issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The recommendation that no further axial surgery be considered for certain patients with only one or two involved sentinel lymph nodes reflects an upgrade of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline on sentinel node biopsy to a category 1 recommendation.

The change is based on the findings of recent prospective studies. In particular, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial, found no survival difference between early-stage breast cancer patients who underwent axillary lymph node dissection [ALND] and those who did not after one or two sentinel nodes were determined to be positive on biopsy (JAMA 2011;305:569-75).

The revised recommendation extends only to those patients with early-stage disease (tumor grades 1 or 2) who undergo breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiation and who have not received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, according to the guidelines. A primary objective is to reduce the risk of lymphedema associated with axillary lymph node dissection.

"In the absence of definitive data demonstrating superior survival from the performance of axillary lymph node dissection, patients who have particularly favorable tumors, patients for whom the selection of adjuvant systemic therapy is unlikely to be affected, for the elderly or those with serious comorbid conditions, the performance of axillary lymph node dissection may be considered optional," the guidelines advise.

The update was presented at the NCCN annual meeting in Hollywood, Fla. The Breast Cancer Panel lists potential conflict of interest disclosures on the NCCN website.

Axillary lymph node dissection can be skipped in some early-stage breast cancer patients with minimal sentinel node involvement, as well as in those with negative findings on sentinel node biopsy, according to revised clinical practice guidelines issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

The recommendation that no further axial surgery be considered for certain patients with only one or two involved sentinel lymph nodes reflects an upgrade of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline on sentinel node biopsy to a category 1 recommendation.

The change is based on the findings of recent prospective studies. In particular, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial, found no survival difference between early-stage breast cancer patients who underwent axillary lymph node dissection [ALND] and those who did not after one or two sentinel nodes were determined to be positive on biopsy (JAMA 2011;305:569-75).

The revised recommendation extends only to those patients with early-stage disease (tumor grades 1 or 2) who undergo breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiation and who have not received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, according to the guidelines. A primary objective is to reduce the risk of lymphedema associated with axillary lymph node dissection.

"In the absence of definitive data demonstrating superior survival from the performance of axillary lymph node dissection, patients who have particularly favorable tumors, patients for whom the selection of adjuvant systemic therapy is unlikely to be affected, for the elderly or those with serious comorbid conditions, the performance of axillary lymph node dissection may be considered optional," the guidelines advise.

The update was presented at the NCCN annual meeting in Hollywood, Fla. The Breast Cancer Panel lists potential conflict of interest disclosures on the NCCN website.

FROM THE NATIONAL COMPREHENSIVE CANCER NETWORK

Evidence Suggests Pregnancies Can Survive Maternal Cancer Treatment

Emerging data on pregnancy and cancer can now help women and their doctors chart a safer course between effective treatment and protecting the developing fetus.

Two registries – one in the United States and another in Europe – agree: It’s not only possible to save a pregnancy in many situations, but children born to these women appear to be largely unaffected by in utero chemotherapy exposure. The combined studies followed more than 200 exposed children for up to 18 years; neither one found any elevated risk of congenital anomaly or any kind of cognitive or developmental delay.

"This is practice-changing information," Dr. Frédéric Amant, primary author on the European paper, said in an interview. "Until now, physicians were reluctant to administer chemotherapy and usually opted for termination, or at least for a delay in treatment or premature delivery in order to get treatment going," he said.

Dr. Amant’s study leads off a special section on cancer in pregnancy, published in the March issue of Lancet Oncology. The paper examined evidence that both supports and questions the clinical wisdom of treating a disease that threatens two very different patients – an adult woman and the fetus she carries.

Every case is different, depending on the type of cancer, its grade and potential aggressiveness, the stage of pregnancy, and the woman’s own desires, said Dr. Elyce Cardonick, an ob.gyn. at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J., and the lead investigator of the Pregnancy and Cancer Registry.

"With solid tumors you usually have time to do the surgery, get the pathologic diagnosis, and let the patient recover. But if there is leukemia, for instance, you have to move faster. The first question should be ‘Could we delay treatment for this patient if she was not pregnant?’ I don’t want to limit their treatment, but at the same time, it’s true that they might not be getting the most up-to-date treatment – the newest agent on the block – because you would want to go with something there is at least some experience with. But this doesn’t necessarily mean they are going to do worse."

Cancer occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies, said Dr. Sarah Temkin, a gynecologic oncologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Many of her patients are referred after a routine screening during early pregnancy finds something abnormal, or when a woman with an existing cancer is incidentally found to be pregnant. But signs that might raise a red flag in other situations don’t necessarily alert physicians to danger in pregnant women, she said in an interview. Pregnancy could obfuscate some symptoms, which might be further downplayed in light of a mother’s relatively young age. Breast cancer is a prime example.

"There are two problems, especially for breast cancers, which are the most common ones we see in pregnancy. First, a woman’s breasts are changing anyway during that time. Breast cancer is so rare in women of earlier childbearing age that both the patient and the doctor tend to disregard any new lumps and bumps."

But despite its rarity, cancer in all forms appears to be increasing among pregnant women, she said. This is probably a direct relation to age. "Cancer rates increase with increasing age, and women are becoming mothers at older and older ages."

When cancer coincides with pregnancy, Dr. Temkin views the mother’s health as paramount. "The mother is the person with cancer, and she deserves whatever the standard of care is for that particular cancer – the best care that would be offered to her if she was not pregnant."

Chemotherapy and Fetal Outcomes

To examine long-term neurodevelopmental risks associated with maternal cancer treatment, Dr. Amant, a gynecologic oncologist at the Leuven (Belgium) Cancer Institute, and his colleagues, are following 70 children from the age of 18 months until 18 years. In the newly published interim analysis, the mean follow-up time is 22 months. All the children had intrauterine exposure to chemotherapy, radiation, oncologic surgery, or combinations of these.

The analysis, which also appeared in Lancet Oncology’s special issue, includes data on all the children, including 18 who are now older than 9 years (Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:256-64).

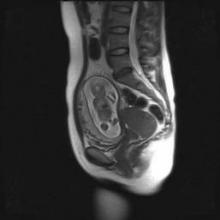

The children – 68 singletons and one set of twins – were born from pregnancies exposed to a total of 236 chemotherapy cycles. Exposure varied by the mother’s cancer type and its stage at diagnosis. In all, 34 mothers were treated with only chemotherapy, 27 had chemotherapy and surgery, 1 received chemotherapy and radiation, and 6 women were treated with all three modalities. Most of the children also had in utero exposure to multiple imaging studies, including MRI, ultrasound, echocardiography, CT, and mammography. Chemotherapy regimens included doxorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin and daunorubicin.

Fetuses also were exposed to a variety of other drugs, including antibiotics, antiemetics, pain medications, colony stimulating factors, and anxiolytics.

Breast cancer was the most common disease type (35). There were 18 cases of hematologic cancers, 6 ovarian cancers, 4 cervical cancers, and 1 each of basal cell carcinoma, brain tumor, Ewing’s sarcoma, colorectal cancer, and nasopharyngeal cancer.

The mean gestational age at cancer diagnosis was 18 weeks, although fetuses ranged in age from 2 to 33 weeks when their mothers were diagnosed. About a third of the babies (23) were born at term.

Seven were born at 28-32 weeks, nine at 32-34 weeks, and 31 at 34-37 weeks. Weight for gestational age was below the 10th percentile in 14 children (21%).

Seven congenital anomalies were found in the group of 70 children (10%) – a rate not significantly different from that in the background population. There were only two major malformations, for a 2.9% rate. Malformations included the following:

• Hip subluxation, pectus excavatum and hemangioma, associated with chemotherapy only.

• Bilateral partial syndactyly, associated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy.

• Bilateral small protuberance on one finger, and rectal atresia, associated with chemotherapy plus surgery.

• Bilateral double cartilage ring in a child exposed to chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy.

None of the children showed any congenital cardiac issues.

All of the children showed neurocognitive development that was within normal range, except for the set of twins, who were delivered by cesarean section at 32.5 weeks after a preterm premature rupture of membranes. These children were so delayed that they were not able to complete cognitive testing. Their mother developed an acute myeloid leukemia – one of the true "emergency" cancers diagnosed in pregnancy, Dr. Amant said. The babies had been exposed to idarubicin and cytosine arabinoside at 15.5, 21.5, 26.5, and 31.5 weeks’ gestation.

The boy, who weighed 1,640 g at birth, had a normal karyotype but, at 3 years, brain imaging showed a unilateral polymicrogyria in the left perisylvian area. He showed an early developmental delay; at age 9 years, he had the developmental capacity of a 12-month old.

The girl, who weighed 1,390 g at birth, also had an early developmental delay, but at age 9 years she attended school with support. Her parents refused brain imaging.

"The other 68 children did well," Dr. Amant said. "This doesn’t mean they were all normal in every way, but in any population you will see learning and developmental delay issues. We think the problem for the delayed children was not related to chemotherapy exposure, but more likely to their prematurity."

Dr. Amant saw a direct correlation between gestational age and intelligence quota. "When we controlled for age, gender, and country of birth, we found that the IQ score increased by almost 12 points for each additional month of gestation."

The U.S. Experience

Dr. Cardonick has found similar results. Her registry now contains information on 280 women who were enrolled over a 13-year period. The children born from these pregnancies have been assessed annually since birth. It also includes 70 controls – children whose mothers had cancer but who were not exposed to chemotherapy.

She published interim results of the registry in 2010 (Cancer J. 2010;16:76-82). At that point, it contained information on 231 women and 157 children. The most common malignancy was breast cancer (128); the mean gestational age at diagnosis was 13 weeks. About a third of the women (54) were advised to terminate their pregnancy; 12 did so.

Among those who continued both pregnancy and treatment, neonatal outcomes were generally good. There were nine premature deliveries related to preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. The congenital anomaly rate born was 4%, which was in line with the normal background rate and slightly lower than that seen in Dr. Amant’s cohort.

The infants’ mean birth weight was 2,647 g, which was significantly less than the mean 2,873 g in the control group, but probably clinically irrelevant, Dr. Cardonick wrote in the paper.

She continues to follow these children annually. At this point, the children are a mean 5 years old; her oldest subject is 14 years. So far, the rate of neurocognitive issues in the group is no different than would be observed in any other group, and none of the children has developed any health problem that could be conclusively tied to intrauterine chemotherapy exposure.

Her experience stresses several key factors that must be considered in this situation. Her patients received chemotherapy at a mean of 20 weeks’ gestation – safely outside the critical early period. Only two women received chemotherapy before 10 weeks; both were treated before they knew they were pregnant. Both children born of these pregnancies were considered well. One with intrauterine exposure to cytarabine was developmentally normal at age 7 years. The other, who was exposed to oxaliplatin and capecitabine, was normal at age 2 years.

Treatment also was stopped a mean of 40 days before delivery, to allow the mother’s bone marrow to fully recover before giving birth.

A second U.S. study was reported at the 2011 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. A poster by Dr. Jennifer Litton and her colleagues examined physiological outcomes in 81 children exposed to chemotherapy for maternal breast cancer. The mothers had taken a standardized chemotherapy regimen of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide (FAC) given during the second and third trimesters (J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29[May 20 suppl.]:abstract 1099).

One child was born with Down syndrome, one with a club foot, and one with ureteral reflux. Three parents reported language delay in later follow-up surveys. Other reported health issues included 15 children with allergies and/or eczema, 2 with asthma, and 1 with absence seizures.

Dr. Litton, a breast oncologist at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, also cowrote a 2010 review of breast cancer treatment in pregnancy, in which she discusses maternal and fetal outcomes from several cohorts, and the possible impact of intrauterine exposure to a variety of chemotherapy agents (Oncologist 2010;15:1238-47).

Risks Vary With Cancer Type

Breast cancer during pregnancy may be the simplest to treat. If the cancer is caught very early, it may be reasonable to delay treatment until the fetus has passed the critical first trimester, waiting until organs are formed and the risk of chemically induced damage is reduced, Dr. Temkin said. "It’s safe to do breast surgery during pregnancy and it’s safe to give chemotherapy after the first trimester."

But physicians can miss a new breast tumor during a prenatal exam, so some present at a more advanced stage, according to Dr. Amant, who is also the lead author of the Lancet’s breast cancer report (Lancet 2012;379:570-9).

Infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas account for more than 70% of the breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy. These can be aggressive, said Dr. Amant. Estrogen receptor status is probably no different in pregnant and nonpregnant women.

If the tumor is discovered early and is pathologically favorable, chemotherapy probably can be delayed until 14 weeks’ gestation, allowing nearly complete fetal organogenesis without worsening the mother’s outcome. Women also may elect an early termination if the pathology is unfavorable, or for other personal reasons, Dr. Temkin said. "I think a lot of it depends on when the cancer is diagnosed. Patients of mine who already have a diagnosis and then become pregnant almost always elect to terminate. But if the cancer is discovered when the pregnancy is farther along, most will continue, especially if the woman is highly emotionally invested," she noted.

Tougher Cancers, Tougher Choices

Treating gynecologic cancers during pregnancy often comes down to a choice between the mother’s health and maintenance of the pregnancy, Dr. Temkin said. "The standard of care for ovarian cancers is surgery or radiation to the pelvis, where the fetus is. Cervical cancer is treated with a hysterectomy or radiation, and neither treatment is compatible with keeping a pregnancy. Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered standard of care for these tumors. These are complex decisions for the patient: ‘Do I accept a different treatment [that might not be as effective] or maintain the pregnancy?’ "

In early cervical cancers without nodal spread, the most common tactic is close observation with periodic imaging to rule out spread; therapy is given after delivery, Dr. Phillippe Morice wrote in the Lancet section’s review on gynecologic malignancies (Lancet 2012;379:558-69).

"Delayed treatment until fetal maturation for patients with stage IA disease has an excellent prognosis and is now the standard of care," wrote Dr. Morice of the Institut de Cancérologie Gustave-Roussy in Villejuif, France.

Locally advanced disease is often not compatible with pregnancy. "The main treatment choice is either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In pregnant patients, this approach means that the pregnancy must be ended before the initiation of therapy, but in exceptional cases in which surgery to end the pregnancy is not technically feasible ([that is], a bulky cervical tumor), radiation therapy can be delivered with the fetus in utero, resulting in a spontaneous abortion in about 3 weeks," he wrote.

Ovarian tumors can be surgically staged and – if it is of low malignant potential – can be laparoscopically removed, usually without endangering the pregnancy. Large tumors or those with aggressive pathology, like epithelial tumors, are much more difficult. Advanced or large tumors often have uterine and pelvic involvement, and treatment usually means a hysterectomy.

The literature contains reports of a very few women who have undergone chemotherapy to control peritoneal spread while keeping a pregnancy. However, despite giving birth to normally developed children, a number of these women died from recurrent disease, Dr. Morice noted.

Hematologic Cancers: True Emergency

Cancers of the blood are rare in pregnancy, occurring in only 1 of every 6,000. But when they do occur, they can be devastating, Dr. Benjamin Brenner wrote in the special series (Lancet 2012;379:580-7).

Pregnant patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma generally do as well as their nonpregnant counterparts and can receive the same chemotherapy regimens, observing the first-trimester delay to favor the fetus.

Those who present with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are likely to have a very poor outlook. This disease is very rare in pregnant women, and symptoms can overlap with Hodgkin’s. Those factors, combined with a desire to avoid imaging, can delay diagnosis until the cancer is more advanced, said Dr. Brenner of the Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, Israel.

Acute leukemia is also rare, but demands urgent attention regardless of gestational stage, Dr. Brenner warned. "Patients diagnosed with acute leukemia during the first trimester are recommended to terminate the pregnancy, in view of the high risk of toxic effects on the fetus and mother, along with the expected need for further intensive treatment including stem-cell transplantation, which is absolutely contraindicated during gestation."

Talking It Out

Despite the emerging positive evidence, treating cancer during pregnancy can be a tough sell, Dr. Amant said. "Women have been told over and over to avoid taking so much as an aspirin. It’s very difficult to convince them that a fetus can not only survive a mother’s cancer treatment, but have a good chance of developing normally."