User login

Should I get a COVID-19 booster shot?

When I was in Florida a few weeks ago, I met a friend outside who approached me wearing an N-95 mask. He said he was wearing it because the Delta variant was running wild in Florida, and several of his younger unvaccinated employees had contracted it, and he encouraged me to get a COVID booster shot. In the late summer, although the federal government recommended booster shots for anyone 8 months after their original vaccination series, national confusion still reigns, with an Food and Drug Administration advisory panel more recently recommending against a Pfizer booster for all adults, but supporting a booster for those ages 65 and older or at a high risk for severe COVID-19.

At the end of December, I was excited when the local hospital whose staff I am on made the Moderna vaccine available. I had to wait several hours but it was worth it, and I did not care about the low-grade fever and malaise I experienced after the second dose. Astoundingly, I still have patients who have not been vaccinated, although many of them are elderly, frail, or immunocompromised. I think people who publicly argue against vaccination need to visit their local intensive care unit.

While less so than some other physicians, – and you must lean in to see anything. We take all reasonable precautions, wearing masks, wiping down exam rooms and door handles, keeping the waiting room as empty as possible, using HEPA filters, and keeping exhaust fans going in the rooms continuously. My staff have all been vaccinated (I’m lucky there).

Still, if you are seeing 30 or 40 patients a day of all age groups and working in small unventilated rooms, you could be exposed to the Delta variant. While breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals may be rare, if you do develop a breakthrough case, even if mild or asymptomatic, CDC recommendations include quarantining for at least 10 days. Obviously, this can be disastrous to your practice as a COVID infection works through your office.

This brings us to back to booster shots. Personally, I think all health care workers should be eager to get a booster shot. I also think individuals who have wide public exposure, particularly indoors, such as teachers and retail sales workers, should be eager to get one too. Here are some of the pros, as well as some cons for boosters.

Arguments for booster shots

- Booster shots should elevate your antibody levels and make you more resistant to breakthrough infections, but this is still theoretical. Antibody levels decline over time – more rapidly in those over 56 years of age.

- Vaccine doses go to waste every month in the United States, although specific numbers are lacking.

- Vaccinated individuals almost never get hospitalized and die from COVID, presumably even fewer do so after receiving a booster.

- You could unwittingly become a vector. Many of the breakthrough infections are mild and without symptoms. If you do test positive, it could be devastating to your patients, and your medical practice.

Arguments against booster shots

- These vaccine doses should be going to other countries that have low vaccination levels where many of the nasty variants are developing.

- You may have side effects from the vaccine, though thrombosis has only been seen with the Astra-Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccines. Myocarditis is usually seen in younger patients and is almost always self limited.

- Breakthrough infections are rare.

This COVID pandemic is moving and changing so fast, it is bewildering. But with a little luck, COVID could eventually become an annual nuisance like the flu, and the COVID vaccine will become an annual shot based on the newest mutations. For now, my opinion is, get your booster shot.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

When I was in Florida a few weeks ago, I met a friend outside who approached me wearing an N-95 mask. He said he was wearing it because the Delta variant was running wild in Florida, and several of his younger unvaccinated employees had contracted it, and he encouraged me to get a COVID booster shot. In the late summer, although the federal government recommended booster shots for anyone 8 months after their original vaccination series, national confusion still reigns, with an Food and Drug Administration advisory panel more recently recommending against a Pfizer booster for all adults, but supporting a booster for those ages 65 and older or at a high risk for severe COVID-19.

At the end of December, I was excited when the local hospital whose staff I am on made the Moderna vaccine available. I had to wait several hours but it was worth it, and I did not care about the low-grade fever and malaise I experienced after the second dose. Astoundingly, I still have patients who have not been vaccinated, although many of them are elderly, frail, or immunocompromised. I think people who publicly argue against vaccination need to visit their local intensive care unit.

While less so than some other physicians, – and you must lean in to see anything. We take all reasonable precautions, wearing masks, wiping down exam rooms and door handles, keeping the waiting room as empty as possible, using HEPA filters, and keeping exhaust fans going in the rooms continuously. My staff have all been vaccinated (I’m lucky there).

Still, if you are seeing 30 or 40 patients a day of all age groups and working in small unventilated rooms, you could be exposed to the Delta variant. While breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals may be rare, if you do develop a breakthrough case, even if mild or asymptomatic, CDC recommendations include quarantining for at least 10 days. Obviously, this can be disastrous to your practice as a COVID infection works through your office.

This brings us to back to booster shots. Personally, I think all health care workers should be eager to get a booster shot. I also think individuals who have wide public exposure, particularly indoors, such as teachers and retail sales workers, should be eager to get one too. Here are some of the pros, as well as some cons for boosters.

Arguments for booster shots

- Booster shots should elevate your antibody levels and make you more resistant to breakthrough infections, but this is still theoretical. Antibody levels decline over time – more rapidly in those over 56 years of age.

- Vaccine doses go to waste every month in the United States, although specific numbers are lacking.

- Vaccinated individuals almost never get hospitalized and die from COVID, presumably even fewer do so after receiving a booster.

- You could unwittingly become a vector. Many of the breakthrough infections are mild and without symptoms. If you do test positive, it could be devastating to your patients, and your medical practice.

Arguments against booster shots

- These vaccine doses should be going to other countries that have low vaccination levels where many of the nasty variants are developing.

- You may have side effects from the vaccine, though thrombosis has only been seen with the Astra-Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccines. Myocarditis is usually seen in younger patients and is almost always self limited.

- Breakthrough infections are rare.

This COVID pandemic is moving and changing so fast, it is bewildering. But with a little luck, COVID could eventually become an annual nuisance like the flu, and the COVID vaccine will become an annual shot based on the newest mutations. For now, my opinion is, get your booster shot.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

When I was in Florida a few weeks ago, I met a friend outside who approached me wearing an N-95 mask. He said he was wearing it because the Delta variant was running wild in Florida, and several of his younger unvaccinated employees had contracted it, and he encouraged me to get a COVID booster shot. In the late summer, although the federal government recommended booster shots for anyone 8 months after their original vaccination series, national confusion still reigns, with an Food and Drug Administration advisory panel more recently recommending against a Pfizer booster for all adults, but supporting a booster for those ages 65 and older or at a high risk for severe COVID-19.

At the end of December, I was excited when the local hospital whose staff I am on made the Moderna vaccine available. I had to wait several hours but it was worth it, and I did not care about the low-grade fever and malaise I experienced after the second dose. Astoundingly, I still have patients who have not been vaccinated, although many of them are elderly, frail, or immunocompromised. I think people who publicly argue against vaccination need to visit their local intensive care unit.

While less so than some other physicians, – and you must lean in to see anything. We take all reasonable precautions, wearing masks, wiping down exam rooms and door handles, keeping the waiting room as empty as possible, using HEPA filters, and keeping exhaust fans going in the rooms continuously. My staff have all been vaccinated (I’m lucky there).

Still, if you are seeing 30 or 40 patients a day of all age groups and working in small unventilated rooms, you could be exposed to the Delta variant. While breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals may be rare, if you do develop a breakthrough case, even if mild or asymptomatic, CDC recommendations include quarantining for at least 10 days. Obviously, this can be disastrous to your practice as a COVID infection works through your office.

This brings us to back to booster shots. Personally, I think all health care workers should be eager to get a booster shot. I also think individuals who have wide public exposure, particularly indoors, such as teachers and retail sales workers, should be eager to get one too. Here are some of the pros, as well as some cons for boosters.

Arguments for booster shots

- Booster shots should elevate your antibody levels and make you more resistant to breakthrough infections, but this is still theoretical. Antibody levels decline over time – more rapidly in those over 56 years of age.

- Vaccine doses go to waste every month in the United States, although specific numbers are lacking.

- Vaccinated individuals almost never get hospitalized and die from COVID, presumably even fewer do so after receiving a booster.

- You could unwittingly become a vector. Many of the breakthrough infections are mild and without symptoms. If you do test positive, it could be devastating to your patients, and your medical practice.

Arguments against booster shots

- These vaccine doses should be going to other countries that have low vaccination levels where many of the nasty variants are developing.

- You may have side effects from the vaccine, though thrombosis has only been seen with the Astra-Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson vaccines. Myocarditis is usually seen in younger patients and is almost always self limited.

- Breakthrough infections are rare.

This COVID pandemic is moving and changing so fast, it is bewildering. But with a little luck, COVID could eventually become an annual nuisance like the flu, and the COVID vaccine will become an annual shot based on the newest mutations. For now, my opinion is, get your booster shot.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Doctor who claimed masks hurt health loses license

Steven Arthur LaTulippe’s advice to patients about face masking amounted to “gross negligence” in the practice of medicine and was grounds for discipline, the medical board said in a report.

Mr. LaTulippe, who had a family practice in Dallas, was fined $10,000, Insider reported. The board also said he’d overprescribed opioids for some patients.

The medical board report said Mr. LaTulippe and his wife, who ran the clinic with him, didn’t wear face masks while treating patients from March to December 2020.

Mr. LaTulippe told elderly and pediatric patients that mask wearing could hurt their health by exacerbating COPD and asthma and could contribute to heart attacks and other medical problems, the report said.

“Licensee asserts masks are likely to harm patients by increasing the body’s carbon dioxide content through rebreathing of gas trapped behind a mask,” the report said.

The report noted that “the amount of carbon dioxide rebreathed within a mask is trivial and would easily be expelled by an increase in minute ventilation so small it would not be noticed.”

The report said Mr. LaTulippe told patients they didn’t have to wear a mask in the clinic unless they were “acutely ill,” “coughing,” or “congested,” even though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Oregon governor had recommended masks be worn to prevent the spread of the virus.

Before coming into the office, patients weren’t asked if they’d had recent contact with anybody who was infected or showed COVID symptoms, the report said.

The medical board first suspended his license in September. He said he would not change his conduct concerning face masks.

“Licensee has confirmed that he will refuse to abide by the state’s COVID-19 protocols in the future as well, affirming that in a choice between losing his medical license versus wearing a mask in his clinic and requiring his patients and staff to wear a mask in his clinic, he will, ‘choose to sacrifice my medical license with no hesitation’ ” the medical board’s report said.

Mr. LaTulippe told the medical board that he was “a strong asset to the public in educating them on the real facts about this pandemic” and that “at least 98% of my patients were so extremely thankful that I did not wear a mask or demand wearing a mask in my clinic.”

The medical board found Mr. LaTulippe engaged in 8 instances of unprofessional or dishonorable conduct, 22 instances of negligence in the practice of medicine, and 5 instances of gross negligence in the practice of medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Steven Arthur LaTulippe’s advice to patients about face masking amounted to “gross negligence” in the practice of medicine and was grounds for discipline, the medical board said in a report.

Mr. LaTulippe, who had a family practice in Dallas, was fined $10,000, Insider reported. The board also said he’d overprescribed opioids for some patients.

The medical board report said Mr. LaTulippe and his wife, who ran the clinic with him, didn’t wear face masks while treating patients from March to December 2020.

Mr. LaTulippe told elderly and pediatric patients that mask wearing could hurt their health by exacerbating COPD and asthma and could contribute to heart attacks and other medical problems, the report said.

“Licensee asserts masks are likely to harm patients by increasing the body’s carbon dioxide content through rebreathing of gas trapped behind a mask,” the report said.

The report noted that “the amount of carbon dioxide rebreathed within a mask is trivial and would easily be expelled by an increase in minute ventilation so small it would not be noticed.”

The report said Mr. LaTulippe told patients they didn’t have to wear a mask in the clinic unless they were “acutely ill,” “coughing,” or “congested,” even though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Oregon governor had recommended masks be worn to prevent the spread of the virus.

Before coming into the office, patients weren’t asked if they’d had recent contact with anybody who was infected or showed COVID symptoms, the report said.

The medical board first suspended his license in September. He said he would not change his conduct concerning face masks.

“Licensee has confirmed that he will refuse to abide by the state’s COVID-19 protocols in the future as well, affirming that in a choice between losing his medical license versus wearing a mask in his clinic and requiring his patients and staff to wear a mask in his clinic, he will, ‘choose to sacrifice my medical license with no hesitation’ ” the medical board’s report said.

Mr. LaTulippe told the medical board that he was “a strong asset to the public in educating them on the real facts about this pandemic” and that “at least 98% of my patients were so extremely thankful that I did not wear a mask or demand wearing a mask in my clinic.”

The medical board found Mr. LaTulippe engaged in 8 instances of unprofessional or dishonorable conduct, 22 instances of negligence in the practice of medicine, and 5 instances of gross negligence in the practice of medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Steven Arthur LaTulippe’s advice to patients about face masking amounted to “gross negligence” in the practice of medicine and was grounds for discipline, the medical board said in a report.

Mr. LaTulippe, who had a family practice in Dallas, was fined $10,000, Insider reported. The board also said he’d overprescribed opioids for some patients.

The medical board report said Mr. LaTulippe and his wife, who ran the clinic with him, didn’t wear face masks while treating patients from March to December 2020.

Mr. LaTulippe told elderly and pediatric patients that mask wearing could hurt their health by exacerbating COPD and asthma and could contribute to heart attacks and other medical problems, the report said.

“Licensee asserts masks are likely to harm patients by increasing the body’s carbon dioxide content through rebreathing of gas trapped behind a mask,” the report said.

The report noted that “the amount of carbon dioxide rebreathed within a mask is trivial and would easily be expelled by an increase in minute ventilation so small it would not be noticed.”

The report said Mr. LaTulippe told patients they didn’t have to wear a mask in the clinic unless they were “acutely ill,” “coughing,” or “congested,” even though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Oregon governor had recommended masks be worn to prevent the spread of the virus.

Before coming into the office, patients weren’t asked if they’d had recent contact with anybody who was infected or showed COVID symptoms, the report said.

The medical board first suspended his license in September. He said he would not change his conduct concerning face masks.

“Licensee has confirmed that he will refuse to abide by the state’s COVID-19 protocols in the future as well, affirming that in a choice between losing his medical license versus wearing a mask in his clinic and requiring his patients and staff to wear a mask in his clinic, he will, ‘choose to sacrifice my medical license with no hesitation’ ” the medical board’s report said.

Mr. LaTulippe told the medical board that he was “a strong asset to the public in educating them on the real facts about this pandemic” and that “at least 98% of my patients were so extremely thankful that I did not wear a mask or demand wearing a mask in my clinic.”

The medical board found Mr. LaTulippe engaged in 8 instances of unprofessional or dishonorable conduct, 22 instances of negligence in the practice of medicine, and 5 instances of gross negligence in the practice of medicine.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Pandemic affected home life of nearly 70% of female physicians with children

The survey, conducted by the Robert Graham Center and the American Board of Family Medicine from May to June 2020, examined the professional and personal experiences of being a mother and a primary care physician during the pandemic.

“The pandemic was hard for everyone, but for women who had children in the home, and it didn’t really matter what age, it seemed like the emotional impact was much harder,” study author Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, said in an interview.

The results of the survey of 89 female physicians who worked in the primary care specialty were published in the Journal of Mother Studies.

Dr. Jabbapour and her colleagues found that 67% of female physicians with children said the pandemic had a great “impact” on their home life compared with 25% of those without children. Furthermore, 41% of physician moms said COVID-19 greatly affected their work life, as opposed to 17% of their counterparts without children.

“Women are going into medicine at much higher rates. In primary care, it’s becoming close to the majority,” said Dr. Jabbarpour, a family physician and medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies. “That has important workforce implications. If we’re not supporting our female physicians and they are greater than 50% of the physician workforce and they’re burning out, who’s going to have a doctor anymore?”

Child care challenges

Researchers found that the emotional toll female physicians experienced early on in the pandemic was indicative of the challenges they were facing. Some of those challenges included managing anxiety, increased stress from both work and home, and social isolation from friends and family.

Another challenge physician mothers had to deal with was fulfilling child care and homeschooling needs, as many women didn’t know what to do with their children and didn’t have external support from their employers.

Child care options vanished for many people during the pandemic, Emily Kaye, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

“I think it was incredibly challenging for everyone and uniquely challenging for women who were young mothers, specifically with respect to child care” said Dr. Kaye, assistant professor in the department of oncology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “Many women were expected to just continue plugging on in the absence of any reasonable or safe form of child care.”

Some of the changes physician-mothers said they were required to make at home or in their personal lives included physical changes related to their family safety, such as decontaminating themselves in their garages before heading home after a shift. Some also reported that they had to find new ways to maintain emotional and mental health because of social isolation from family and friends.

The survey results, which were taken early on in the pandemic, highlight the need for health policies that support physician mothers and families, as women shoulder the burden of parenting and domestic responsibilities in heterosexual relationships, the researchers said.

“I’m hoping that people pay attention and start to implement more family friendly policies within their workplaces,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “But during a pandemic, it was essential for [female health care workers] to go in, and they had nowhere to put their kids. [Therefore], the choice became leaving young children alone at home, putting them into daycare facilities that did remain open without knowing if they were [safe], or quitting their jobs. None of those choices are good.”

Community support as a potential solution

Dr. Kaye said she believes that there should be a “long overdue investment” in community support, affordable and accessible child care, flexible spending, paid family leave, and other forms of caregiving support.

“In order to keep women physicians in the workforce, we need to have a significant increase in investment in the social safety net in this country,” Dr. Kaye said.

Researchers said more studies should evaluate the role the COVID-19 pandemic had on the primary care workforce in the U.S., “with a specific emphasis on how the pandemic impacted mothers, and should more intentionally consider the further intersections of race and ethnicity in the experiences of physician-mothers.”

“I think people are burning out and then there’s all this anti-science, anti-health sentiment out there, which makes it harder,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “If we did repeat this study now, I think things would be even more dire in the voices of the women that we heard.”

Dr. Jabbarpour and Dr. Kaye reported no disclosures.

The survey, conducted by the Robert Graham Center and the American Board of Family Medicine from May to June 2020, examined the professional and personal experiences of being a mother and a primary care physician during the pandemic.

“The pandemic was hard for everyone, but for women who had children in the home, and it didn’t really matter what age, it seemed like the emotional impact was much harder,” study author Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, said in an interview.

The results of the survey of 89 female physicians who worked in the primary care specialty were published in the Journal of Mother Studies.

Dr. Jabbapour and her colleagues found that 67% of female physicians with children said the pandemic had a great “impact” on their home life compared with 25% of those without children. Furthermore, 41% of physician moms said COVID-19 greatly affected their work life, as opposed to 17% of their counterparts without children.

“Women are going into medicine at much higher rates. In primary care, it’s becoming close to the majority,” said Dr. Jabbarpour, a family physician and medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies. “That has important workforce implications. If we’re not supporting our female physicians and they are greater than 50% of the physician workforce and they’re burning out, who’s going to have a doctor anymore?”

Child care challenges

Researchers found that the emotional toll female physicians experienced early on in the pandemic was indicative of the challenges they were facing. Some of those challenges included managing anxiety, increased stress from both work and home, and social isolation from friends and family.

Another challenge physician mothers had to deal with was fulfilling child care and homeschooling needs, as many women didn’t know what to do with their children and didn’t have external support from their employers.

Child care options vanished for many people during the pandemic, Emily Kaye, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

“I think it was incredibly challenging for everyone and uniquely challenging for women who were young mothers, specifically with respect to child care” said Dr. Kaye, assistant professor in the department of oncology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “Many women were expected to just continue plugging on in the absence of any reasonable or safe form of child care.”

Some of the changes physician-mothers said they were required to make at home or in their personal lives included physical changes related to their family safety, such as decontaminating themselves in their garages before heading home after a shift. Some also reported that they had to find new ways to maintain emotional and mental health because of social isolation from family and friends.

The survey results, which were taken early on in the pandemic, highlight the need for health policies that support physician mothers and families, as women shoulder the burden of parenting and domestic responsibilities in heterosexual relationships, the researchers said.

“I’m hoping that people pay attention and start to implement more family friendly policies within their workplaces,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “But during a pandemic, it was essential for [female health care workers] to go in, and they had nowhere to put their kids. [Therefore], the choice became leaving young children alone at home, putting them into daycare facilities that did remain open without knowing if they were [safe], or quitting their jobs. None of those choices are good.”

Community support as a potential solution

Dr. Kaye said she believes that there should be a “long overdue investment” in community support, affordable and accessible child care, flexible spending, paid family leave, and other forms of caregiving support.

“In order to keep women physicians in the workforce, we need to have a significant increase in investment in the social safety net in this country,” Dr. Kaye said.

Researchers said more studies should evaluate the role the COVID-19 pandemic had on the primary care workforce in the U.S., “with a specific emphasis on how the pandemic impacted mothers, and should more intentionally consider the further intersections of race and ethnicity in the experiences of physician-mothers.”

“I think people are burning out and then there’s all this anti-science, anti-health sentiment out there, which makes it harder,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “If we did repeat this study now, I think things would be even more dire in the voices of the women that we heard.”

Dr. Jabbarpour and Dr. Kaye reported no disclosures.

The survey, conducted by the Robert Graham Center and the American Board of Family Medicine from May to June 2020, examined the professional and personal experiences of being a mother and a primary care physician during the pandemic.

“The pandemic was hard for everyone, but for women who had children in the home, and it didn’t really matter what age, it seemed like the emotional impact was much harder,” study author Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, said in an interview.

The results of the survey of 89 female physicians who worked in the primary care specialty were published in the Journal of Mother Studies.

Dr. Jabbapour and her colleagues found that 67% of female physicians with children said the pandemic had a great “impact” on their home life compared with 25% of those without children. Furthermore, 41% of physician moms said COVID-19 greatly affected their work life, as opposed to 17% of their counterparts without children.

“Women are going into medicine at much higher rates. In primary care, it’s becoming close to the majority,” said Dr. Jabbarpour, a family physician and medical director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies. “That has important workforce implications. If we’re not supporting our female physicians and they are greater than 50% of the physician workforce and they’re burning out, who’s going to have a doctor anymore?”

Child care challenges

Researchers found that the emotional toll female physicians experienced early on in the pandemic was indicative of the challenges they were facing. Some of those challenges included managing anxiety, increased stress from both work and home, and social isolation from friends and family.

Another challenge physician mothers had to deal with was fulfilling child care and homeschooling needs, as many women didn’t know what to do with their children and didn’t have external support from their employers.

Child care options vanished for many people during the pandemic, Emily Kaye, MD, MPH, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

“I think it was incredibly challenging for everyone and uniquely challenging for women who were young mothers, specifically with respect to child care” said Dr. Kaye, assistant professor in the department of oncology at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “Many women were expected to just continue plugging on in the absence of any reasonable or safe form of child care.”

Some of the changes physician-mothers said they were required to make at home or in their personal lives included physical changes related to their family safety, such as decontaminating themselves in their garages before heading home after a shift. Some also reported that they had to find new ways to maintain emotional and mental health because of social isolation from family and friends.

The survey results, which were taken early on in the pandemic, highlight the need for health policies that support physician mothers and families, as women shoulder the burden of parenting and domestic responsibilities in heterosexual relationships, the researchers said.

“I’m hoping that people pay attention and start to implement more family friendly policies within their workplaces,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “But during a pandemic, it was essential for [female health care workers] to go in, and they had nowhere to put their kids. [Therefore], the choice became leaving young children alone at home, putting them into daycare facilities that did remain open without knowing if they were [safe], or quitting their jobs. None of those choices are good.”

Community support as a potential solution

Dr. Kaye said she believes that there should be a “long overdue investment” in community support, affordable and accessible child care, flexible spending, paid family leave, and other forms of caregiving support.

“In order to keep women physicians in the workforce, we need to have a significant increase in investment in the social safety net in this country,” Dr. Kaye said.

Researchers said more studies should evaluate the role the COVID-19 pandemic had on the primary care workforce in the U.S., “with a specific emphasis on how the pandemic impacted mothers, and should more intentionally consider the further intersections of race and ethnicity in the experiences of physician-mothers.”

“I think people are burning out and then there’s all this anti-science, anti-health sentiment out there, which makes it harder,” Dr. Jabbarpour said. “If we did repeat this study now, I think things would be even more dire in the voices of the women that we heard.”

Dr. Jabbarpour and Dr. Kaye reported no disclosures.

FROM JOURNAL OF MOTHER STUDIES

Noise in medicine

A 26-year-old woman who reports a history of acyclovir-resistant herpes complains of a recurring, stinging rash around her mouth. Topical tacrolimus made it worse, she said. On exam, she has somewhat grouped pustules on her cutaneous lip. I mentioned her to colleagues, saying: “I’ve a patient with acyclovir-resistant herpes who isn’t improving on high-dose Valtrex.” They proffered a few alternative diagnoses and treatment recommendations. I tried several to no avail.

(it is after all only one condition). Nobel Prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman, PhD, with two other authors, has written a brilliant book about this cognitive unreliability called “Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2021).

Both bias and noise create trouble for us. Although biases get more attention, noise is both more prevalent and insidious. In a 2016 article, Dr. Kahneman and coauthors use a bathroom scale as an analogy to explain the difference. “We would say that the scale is biased if its readings are generally either too high or too low. A scale that consistently underestimates true weight by exactly 4 pounds is seriously biased but free of noise. A scale that gives two different readings when you step on it twice is noisy.” In the case presented, “measurements” by me and my colleagues were returning different “readings.” There is one true diagnosis and best treatment, yet because of noise, we waste time and resources by not getting it right the first time.

There is also evidence of bias in this case. For example, there’s probably some confirmation bias: The patient said she has a history of antiviral-resistant herpes; therefore, her rash might appear to be herpes. Also there might be salience bias: it’s easy to see how prominent pustules might be herpes simplex virus. Noise is an issue in many misdiagnoses, but trickier to see. In most instances, we don’t have the opportunity to get multiple assessments of the same case. When examined though, interrater reliability in medicine is often found to be shockingly low, an indication of how much noise there is in our clinical judgments. This leads to waste, frustration – and can even be dangerous when we’re trying to diagnose cancers such as melanoma, lung, or breast cancer.

Dr. Kahneman and colleagues have excellent recommendations on how to reduce noise, such as tips for good decision hygiene (e.g., using differential diagnoses) and using algorithms (e.g., calculating Apgar or LACE scores). I also liked their strategy of aggregating expert opinions. Fascinatingly, averaging multiple independent assessments is mathematically guaranteed to reduce noise. (God, I love economists). This is true of measurements and opinions: If you use 100 judgments for a case, you reduce noise by 90% (the noise is divided by the square root of the number of judgments averaged). So 20 colleagues’ opinions would reduce noise by almost 80%. However, those 20 opinions must be independent to avoid spurious agreement. (Again, math for the win.)

I showed photos of my patient to a few other dermatologists. They independently returned the same result: perioral dermatitis. This was the correct diagnosis and reminded me why grand rounds and tumor boards are such a great help. Multiple, independent assessments are more likely to get it right than just one opinion because we are canceling out the noise. But remember, grand rounds has to be old-school style – no looking at your coresident answers before giving yours!

Our patient cleared after restarting her topical tacrolimus and a bit of doxycycline. Credit the wisdom of the crowd. Reassuringly though, Dr. Kahneman also shows that expertise does matter in minimizing error. So that fellowship you did was still a great idea.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. He reports having no conflicts of interest. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

A 26-year-old woman who reports a history of acyclovir-resistant herpes complains of a recurring, stinging rash around her mouth. Topical tacrolimus made it worse, she said. On exam, she has somewhat grouped pustules on her cutaneous lip. I mentioned her to colleagues, saying: “I’ve a patient with acyclovir-resistant herpes who isn’t improving on high-dose Valtrex.” They proffered a few alternative diagnoses and treatment recommendations. I tried several to no avail.

(it is after all only one condition). Nobel Prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman, PhD, with two other authors, has written a brilliant book about this cognitive unreliability called “Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2021).

Both bias and noise create trouble for us. Although biases get more attention, noise is both more prevalent and insidious. In a 2016 article, Dr. Kahneman and coauthors use a bathroom scale as an analogy to explain the difference. “We would say that the scale is biased if its readings are generally either too high or too low. A scale that consistently underestimates true weight by exactly 4 pounds is seriously biased but free of noise. A scale that gives two different readings when you step on it twice is noisy.” In the case presented, “measurements” by me and my colleagues were returning different “readings.” There is one true diagnosis and best treatment, yet because of noise, we waste time and resources by not getting it right the first time.

There is also evidence of bias in this case. For example, there’s probably some confirmation bias: The patient said she has a history of antiviral-resistant herpes; therefore, her rash might appear to be herpes. Also there might be salience bias: it’s easy to see how prominent pustules might be herpes simplex virus. Noise is an issue in many misdiagnoses, but trickier to see. In most instances, we don’t have the opportunity to get multiple assessments of the same case. When examined though, interrater reliability in medicine is often found to be shockingly low, an indication of how much noise there is in our clinical judgments. This leads to waste, frustration – and can even be dangerous when we’re trying to diagnose cancers such as melanoma, lung, or breast cancer.

Dr. Kahneman and colleagues have excellent recommendations on how to reduce noise, such as tips for good decision hygiene (e.g., using differential diagnoses) and using algorithms (e.g., calculating Apgar or LACE scores). I also liked their strategy of aggregating expert opinions. Fascinatingly, averaging multiple independent assessments is mathematically guaranteed to reduce noise. (God, I love economists). This is true of measurements and opinions: If you use 100 judgments for a case, you reduce noise by 90% (the noise is divided by the square root of the number of judgments averaged). So 20 colleagues’ opinions would reduce noise by almost 80%. However, those 20 opinions must be independent to avoid spurious agreement. (Again, math for the win.)

I showed photos of my patient to a few other dermatologists. They independently returned the same result: perioral dermatitis. This was the correct diagnosis and reminded me why grand rounds and tumor boards are such a great help. Multiple, independent assessments are more likely to get it right than just one opinion because we are canceling out the noise. But remember, grand rounds has to be old-school style – no looking at your coresident answers before giving yours!

Our patient cleared after restarting her topical tacrolimus and a bit of doxycycline. Credit the wisdom of the crowd. Reassuringly though, Dr. Kahneman also shows that expertise does matter in minimizing error. So that fellowship you did was still a great idea.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. He reports having no conflicts of interest. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

A 26-year-old woman who reports a history of acyclovir-resistant herpes complains of a recurring, stinging rash around her mouth. Topical tacrolimus made it worse, she said. On exam, she has somewhat grouped pustules on her cutaneous lip. I mentioned her to colleagues, saying: “I’ve a patient with acyclovir-resistant herpes who isn’t improving on high-dose Valtrex.” They proffered a few alternative diagnoses and treatment recommendations. I tried several to no avail.

(it is after all only one condition). Nobel Prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman, PhD, with two other authors, has written a brilliant book about this cognitive unreliability called “Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment” (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2021).

Both bias and noise create trouble for us. Although biases get more attention, noise is both more prevalent and insidious. In a 2016 article, Dr. Kahneman and coauthors use a bathroom scale as an analogy to explain the difference. “We would say that the scale is biased if its readings are generally either too high or too low. A scale that consistently underestimates true weight by exactly 4 pounds is seriously biased but free of noise. A scale that gives two different readings when you step on it twice is noisy.” In the case presented, “measurements” by me and my colleagues were returning different “readings.” There is one true diagnosis and best treatment, yet because of noise, we waste time and resources by not getting it right the first time.

There is also evidence of bias in this case. For example, there’s probably some confirmation bias: The patient said she has a history of antiviral-resistant herpes; therefore, her rash might appear to be herpes. Also there might be salience bias: it’s easy to see how prominent pustules might be herpes simplex virus. Noise is an issue in many misdiagnoses, but trickier to see. In most instances, we don’t have the opportunity to get multiple assessments of the same case. When examined though, interrater reliability in medicine is often found to be shockingly low, an indication of how much noise there is in our clinical judgments. This leads to waste, frustration – and can even be dangerous when we’re trying to diagnose cancers such as melanoma, lung, or breast cancer.

Dr. Kahneman and colleagues have excellent recommendations on how to reduce noise, such as tips for good decision hygiene (e.g., using differential diagnoses) and using algorithms (e.g., calculating Apgar or LACE scores). I also liked their strategy of aggregating expert opinions. Fascinatingly, averaging multiple independent assessments is mathematically guaranteed to reduce noise. (God, I love economists). This is true of measurements and opinions: If you use 100 judgments for a case, you reduce noise by 90% (the noise is divided by the square root of the number of judgments averaged). So 20 colleagues’ opinions would reduce noise by almost 80%. However, those 20 opinions must be independent to avoid spurious agreement. (Again, math for the win.)

I showed photos of my patient to a few other dermatologists. They independently returned the same result: perioral dermatitis. This was the correct diagnosis and reminded me why grand rounds and tumor boards are such a great help. Multiple, independent assessments are more likely to get it right than just one opinion because we are canceling out the noise. But remember, grand rounds has to be old-school style – no looking at your coresident answers before giving yours!

Our patient cleared after restarting her topical tacrolimus and a bit of doxycycline. Credit the wisdom of the crowd. Reassuringly though, Dr. Kahneman also shows that expertise does matter in minimizing error. So that fellowship you did was still a great idea.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. He reports having no conflicts of interest. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Supreme Court sets date for case that challenges Roe v. Wade

The Supreme Court will hear arguments in a major Mississippi abortion case on Dec. 1, which could challenge the landmark Roe v. Wade decision that guarantees a woman’s right to an abortion.

On Sept. 20, the court issued its calendar for arguments that will be heard in late November and early December, The Associated Press reported.

The Mississippi case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is seeking to overturn Roe v. Wade by asking the Supreme Court to uphold a ban on most abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy. The state also said the court should overrule the 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that prevents states from banning abortion before viability, which is around 24 weeks of pregnancy.

Earlier in September, the Supreme Court allowed a Texas law to take effect that bans abortions after cardiac activity can be detected, which is around 6 weeks of pregnancy and often before many women know they’re pregnant. The court, which was split 5-4, didn’t rule on the constitutional nature of the law, instead declining to block its enforcement.

Hundreds of legal briefs have been filed on both sides of the case, the AP reported. On Sept. 20, more than 500 women athletes, including members of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association, the National Women’s Soccer League Players Association, and Olympic medalists, filed a brief that said an abortion ban would be devastating for female athletes.

The Mississippi law was enacted in 2018 but was blocked after a challenge at the federal court level. The state’s only abortion clinic, Jackson Women’s Health Organization, remains open and offers abortions up to 16 weeks of pregnancy, the AP reported. About 100 abortions a year are completed after 15 weeks, the organization said.

More than 90% of abortions in the United States occur in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy, the AP said.

The Supreme Court justices will return to the courtroom in October to hear arguments now that all of them have been vaccinated, the AP reported. The justices had been hearing cases by phone during the pandemic.

The public won’t be able to attend sessions, but the court will allow live audio of the session.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments in a major Mississippi abortion case on Dec. 1, which could challenge the landmark Roe v. Wade decision that guarantees a woman’s right to an abortion.

On Sept. 20, the court issued its calendar for arguments that will be heard in late November and early December, The Associated Press reported.

The Mississippi case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is seeking to overturn Roe v. Wade by asking the Supreme Court to uphold a ban on most abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy. The state also said the court should overrule the 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that prevents states from banning abortion before viability, which is around 24 weeks of pregnancy.

Earlier in September, the Supreme Court allowed a Texas law to take effect that bans abortions after cardiac activity can be detected, which is around 6 weeks of pregnancy and often before many women know they’re pregnant. The court, which was split 5-4, didn’t rule on the constitutional nature of the law, instead declining to block its enforcement.

Hundreds of legal briefs have been filed on both sides of the case, the AP reported. On Sept. 20, more than 500 women athletes, including members of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association, the National Women’s Soccer League Players Association, and Olympic medalists, filed a brief that said an abortion ban would be devastating for female athletes.

The Mississippi law was enacted in 2018 but was blocked after a challenge at the federal court level. The state’s only abortion clinic, Jackson Women’s Health Organization, remains open and offers abortions up to 16 weeks of pregnancy, the AP reported. About 100 abortions a year are completed after 15 weeks, the organization said.

More than 90% of abortions in the United States occur in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy, the AP said.

The Supreme Court justices will return to the courtroom in October to hear arguments now that all of them have been vaccinated, the AP reported. The justices had been hearing cases by phone during the pandemic.

The public won’t be able to attend sessions, but the court will allow live audio of the session.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments in a major Mississippi abortion case on Dec. 1, which could challenge the landmark Roe v. Wade decision that guarantees a woman’s right to an abortion.

On Sept. 20, the court issued its calendar for arguments that will be heard in late November and early December, The Associated Press reported.

The Mississippi case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is seeking to overturn Roe v. Wade by asking the Supreme Court to uphold a ban on most abortions after the 15th week of pregnancy. The state also said the court should overrule the 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey that prevents states from banning abortion before viability, which is around 24 weeks of pregnancy.

Earlier in September, the Supreme Court allowed a Texas law to take effect that bans abortions after cardiac activity can be detected, which is around 6 weeks of pregnancy and often before many women know they’re pregnant. The court, which was split 5-4, didn’t rule on the constitutional nature of the law, instead declining to block its enforcement.

Hundreds of legal briefs have been filed on both sides of the case, the AP reported. On Sept. 20, more than 500 women athletes, including members of the Women’s National Basketball Players Association, the National Women’s Soccer League Players Association, and Olympic medalists, filed a brief that said an abortion ban would be devastating for female athletes.

The Mississippi law was enacted in 2018 but was blocked after a challenge at the federal court level. The state’s only abortion clinic, Jackson Women’s Health Organization, remains open and offers abortions up to 16 weeks of pregnancy, the AP reported. About 100 abortions a year are completed after 15 weeks, the organization said.

More than 90% of abortions in the United States occur in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy, the AP said.

The Supreme Court justices will return to the courtroom in October to hear arguments now that all of them have been vaccinated, the AP reported. The justices had been hearing cases by phone during the pandemic.

The public won’t be able to attend sessions, but the court will allow live audio of the session.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Texas doctor admits to violating abortion ban

A Texas doctor revealed in a Washington Post op-ed Sept. 18 that he violated the state ban on abortions performed beyond 6 weeks -- a move he knows could come with legal consequences.

San Antonio doctor Alan Braid, MD, said the new statewide restrictions reminded him of darker days during his 1972 obstetrics and gynecology residency, when he saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions.

“For me, it is 1972 all over again,” he wrote. “And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.”

“I fully understood that there could be legal consequences -- but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested,” he continued.

According to The Washington Post, Dr. Braid’s wish may come true. Two lawsuits against were filed Sept. 20. In one, a prisoner in Arkansas said he filed the suit in part because he could receive $10,000 if successful, according to the Post. The second was filed by a man in Chicago who wants the law struck down.

Dr. Braid’s op-ed is the first public admission to violating a Texas state law that took effect Sept. 1 banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected. The controversial policy gives private citizens the right to bring civil litigation -- resulting in at least $10,000 in damages -- against providers and anyone else involved in the process.

Since the law went into effect, most patients seeking abortions are too far along to qualify, Dr. Braid wrote.

“I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate,” he wrote.

“I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly,” he continued. “Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

A Texas doctor revealed in a Washington Post op-ed Sept. 18 that he violated the state ban on abortions performed beyond 6 weeks -- a move he knows could come with legal consequences.

San Antonio doctor Alan Braid, MD, said the new statewide restrictions reminded him of darker days during his 1972 obstetrics and gynecology residency, when he saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions.

“For me, it is 1972 all over again,” he wrote. “And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.”

“I fully understood that there could be legal consequences -- but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested,” he continued.

According to The Washington Post, Dr. Braid’s wish may come true. Two lawsuits against were filed Sept. 20. In one, a prisoner in Arkansas said he filed the suit in part because he could receive $10,000 if successful, according to the Post. The second was filed by a man in Chicago who wants the law struck down.

Dr. Braid’s op-ed is the first public admission to violating a Texas state law that took effect Sept. 1 banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected. The controversial policy gives private citizens the right to bring civil litigation -- resulting in at least $10,000 in damages -- against providers and anyone else involved in the process.

Since the law went into effect, most patients seeking abortions are too far along to qualify, Dr. Braid wrote.

“I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate,” he wrote.

“I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly,” he continued. “Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

A Texas doctor revealed in a Washington Post op-ed Sept. 18 that he violated the state ban on abortions performed beyond 6 weeks -- a move he knows could come with legal consequences.

San Antonio doctor Alan Braid, MD, said the new statewide restrictions reminded him of darker days during his 1972 obstetrics and gynecology residency, when he saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions.

“For me, it is 1972 all over again,” he wrote. “And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.”

“I fully understood that there could be legal consequences -- but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested,” he continued.

According to The Washington Post, Dr. Braid’s wish may come true. Two lawsuits against were filed Sept. 20. In one, a prisoner in Arkansas said he filed the suit in part because he could receive $10,000 if successful, according to the Post. The second was filed by a man in Chicago who wants the law struck down.

Dr. Braid’s op-ed is the first public admission to violating a Texas state law that took effect Sept. 1 banning abortion once a fetal heartbeat is detected. The controversial policy gives private citizens the right to bring civil litigation -- resulting in at least $10,000 in damages -- against providers and anyone else involved in the process.

Since the law went into effect, most patients seeking abortions are too far along to qualify, Dr. Braid wrote.

“I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate,” he wrote.

“I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly,” he continued. “Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

Aloha

In July, 2021, JAMA published a study about physicians’ sartorial habits, basically saying that people prefer doctors to dress “professionally.” Even today the white coat still carries some weight.

And I still don’t care.

Today, like every workday since June 2006, I put on my standard patient-seeing attire: shorts, sneakers, and a Hawaiian shirt. The only significant change has been the addition of a face mask since March 2020.

I have no plans to change anytime between now and retirement. I live in Phoenix, the hottest major city in the U.S., and have no desire to be uncomfortable because someone doesn’t think I look professional. It’s even become, albeit unintentionally, a trademark of sorts.

Now, as always, I let my patients be the judge. If someone isn’t happy with my appearance, or feels it makes me less competent, they certainly have the right to feel that way. There are plenty of other neurologists here who dress to higher standards (though jackets and ties, outside of the Mayo Clinic down the road, are getting pretty hard to find).

This is one of the things I like about having a small solo practice. I can be who I am, not who some administrator or dress code specialist says I have to be.

I do my best for my patients, and those who know me are aware that my complete lack of fashion sense doesn’t represent (I hope) an equal lack of medical care. Most of them seem to come back, so I guess I’m doing something right.

But it brings up the question of what should a doctor look like? In a world of changing demographics the stereotype of a neatly-dressed middle-aged white male certainly isn’t it anymore.

Nor should there be. Medicine should be open to all with the drive, brains, and talent who want to follow to path of Hippocrates. Maybe I’m naive, but I still see this as a calling more than a job. Judging someone’s medical competence solely on their sex, race, appearance, or fashion sense is foolhardy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In July, 2021, JAMA published a study about physicians’ sartorial habits, basically saying that people prefer doctors to dress “professionally.” Even today the white coat still carries some weight.

And I still don’t care.

Today, like every workday since June 2006, I put on my standard patient-seeing attire: shorts, sneakers, and a Hawaiian shirt. The only significant change has been the addition of a face mask since March 2020.

I have no plans to change anytime between now and retirement. I live in Phoenix, the hottest major city in the U.S., and have no desire to be uncomfortable because someone doesn’t think I look professional. It’s even become, albeit unintentionally, a trademark of sorts.

Now, as always, I let my patients be the judge. If someone isn’t happy with my appearance, or feels it makes me less competent, they certainly have the right to feel that way. There are plenty of other neurologists here who dress to higher standards (though jackets and ties, outside of the Mayo Clinic down the road, are getting pretty hard to find).

This is one of the things I like about having a small solo practice. I can be who I am, not who some administrator or dress code specialist says I have to be.

I do my best for my patients, and those who know me are aware that my complete lack of fashion sense doesn’t represent (I hope) an equal lack of medical care. Most of them seem to come back, so I guess I’m doing something right.

But it brings up the question of what should a doctor look like? In a world of changing demographics the stereotype of a neatly-dressed middle-aged white male certainly isn’t it anymore.

Nor should there be. Medicine should be open to all with the drive, brains, and talent who want to follow to path of Hippocrates. Maybe I’m naive, but I still see this as a calling more than a job. Judging someone’s medical competence solely on their sex, race, appearance, or fashion sense is foolhardy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

In July, 2021, JAMA published a study about physicians’ sartorial habits, basically saying that people prefer doctors to dress “professionally.” Even today the white coat still carries some weight.

And I still don’t care.

Today, like every workday since June 2006, I put on my standard patient-seeing attire: shorts, sneakers, and a Hawaiian shirt. The only significant change has been the addition of a face mask since March 2020.

I have no plans to change anytime between now and retirement. I live in Phoenix, the hottest major city in the U.S., and have no desire to be uncomfortable because someone doesn’t think I look professional. It’s even become, albeit unintentionally, a trademark of sorts.

Now, as always, I let my patients be the judge. If someone isn’t happy with my appearance, or feels it makes me less competent, they certainly have the right to feel that way. There are plenty of other neurologists here who dress to higher standards (though jackets and ties, outside of the Mayo Clinic down the road, are getting pretty hard to find).

This is one of the things I like about having a small solo practice. I can be who I am, not who some administrator or dress code specialist says I have to be.

I do my best for my patients, and those who know me are aware that my complete lack of fashion sense doesn’t represent (I hope) an equal lack of medical care. Most of them seem to come back, so I guess I’m doing something right.

But it brings up the question of what should a doctor look like? In a world of changing demographics the stereotype of a neatly-dressed middle-aged white male certainly isn’t it anymore.

Nor should there be. Medicine should be open to all with the drive, brains, and talent who want to follow to path of Hippocrates. Maybe I’m naive, but I still see this as a calling more than a job. Judging someone’s medical competence solely on their sex, race, appearance, or fashion sense is foolhardy.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

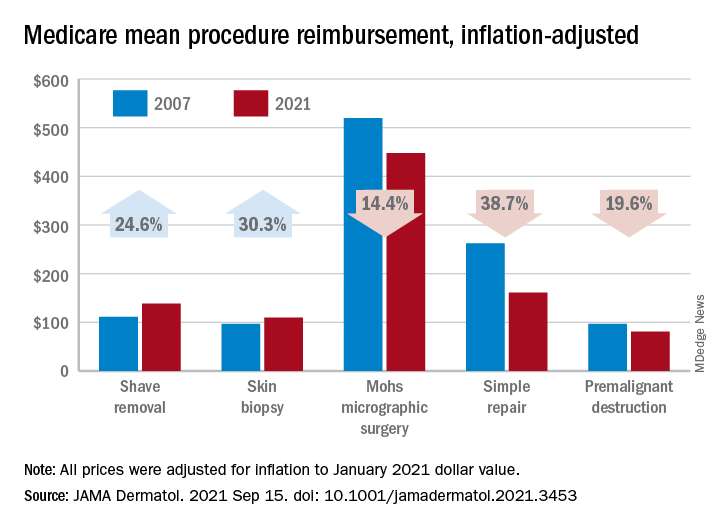

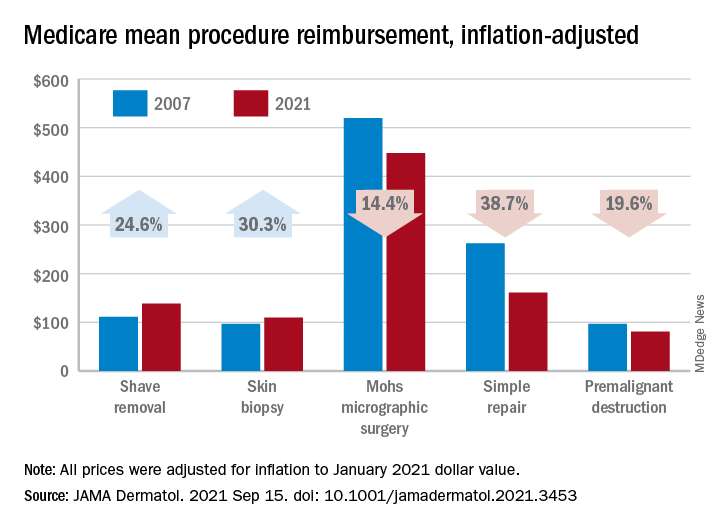

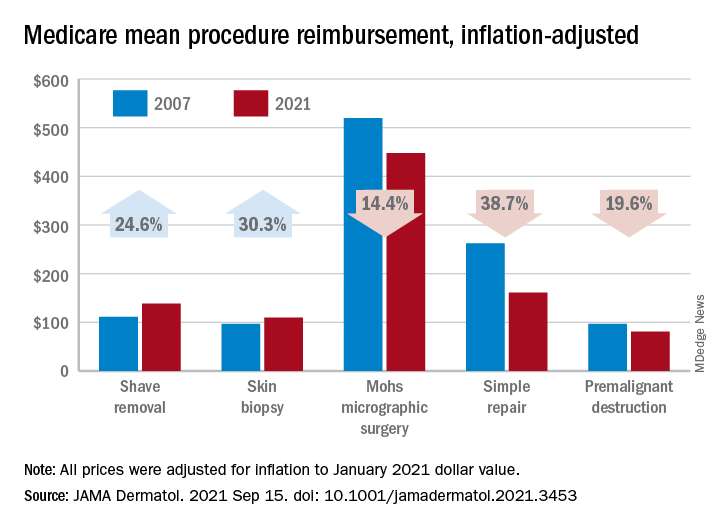

Medicare payments for most skin procedures dropped over last 15 years

according to a new analysis.

Large increases in mean reimbursement for skin biopsies (+30.3%) and shave removal (+24.6%) were not enough to offset lower rates for procedures such as simple repair (–38.7%), premalignant destruction (–19.6%), Mohs micrographic surgery (–14.4%), and flap repair (–14.1%), Rishabh S. Mazmudar, BS, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and associates said.

“Given Medicare’s contribution to a large proportion of health care expenditures, changes in Medicare reimbursement rates may result in parallel changes in private insurance reimbursement,” they wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

A recently published study showed that Medicare reimbursement for 20 dermatologic service codes had fallen by 10% between the two comparison years, 2000 and 2020. The current study expanded the number of procedures to 46 (divided into nine categories) and used historical Medicare fee schedules to examine annual trends over a 15-year period, Mr. Mazmudar and associates explained.

Other specialties have seen reimbursement fall by more than 4.8%, including emergency medicine (–21.2% from 2000 to 2020) and general surgery (–24.4% from 2000 to 2018), but “these comparisons are likely skewed by the disproportionate increase in reimbursement rates for biopsies and shave removals during this time period,” the investigators said.

If those two procedure categories were excluded from the analysis, the mean change in overall reimbursement for the remaining dermatologic procedures would be −9.6%, they noted.

Detailed payment information provided for 15 of the 46 procedures shows that only intermediate repair (+4.5%) and benign destruction (+2.3%) joined biopsies and shave excisions with increased reimbursement from 2007 to 2021. The smallest drop among the other procedures was –1.9% for malignant destruction, the research team reported.

The inflation-adjusted, year-by-year analysis showed that reimbursement for the nine procedure categories has gradually declined since peaking in 2011, with the most notable exceptions being biopsies and shave excisions. Both had been following the trend until 2013, when reimbursement for shave removals jumped by almost 30 percentage points, and 2019, when rates for biopsies soared by more than 30 percentage points, according to the investigators.

The increase for skin biopsies followed the split of the original CPT code into three categories, but “the jump in reimbursement for shave removals in 2013 requires further investigation,” Mr. Mazmudar and associates wrote.

The investigators did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

according to a new analysis.

Large increases in mean reimbursement for skin biopsies (+30.3%) and shave removal (+24.6%) were not enough to offset lower rates for procedures such as simple repair (–38.7%), premalignant destruction (–19.6%), Mohs micrographic surgery (–14.4%), and flap repair (–14.1%), Rishabh S. Mazmudar, BS, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and associates said.

“Given Medicare’s contribution to a large proportion of health care expenditures, changes in Medicare reimbursement rates may result in parallel changes in private insurance reimbursement,” they wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

A recently published study showed that Medicare reimbursement for 20 dermatologic service codes had fallen by 10% between the two comparison years, 2000 and 2020. The current study expanded the number of procedures to 46 (divided into nine categories) and used historical Medicare fee schedules to examine annual trends over a 15-year period, Mr. Mazmudar and associates explained.

Other specialties have seen reimbursement fall by more than 4.8%, including emergency medicine (–21.2% from 2000 to 2020) and general surgery (–24.4% from 2000 to 2018), but “these comparisons are likely skewed by the disproportionate increase in reimbursement rates for biopsies and shave removals during this time period,” the investigators said.

If those two procedure categories were excluded from the analysis, the mean change in overall reimbursement for the remaining dermatologic procedures would be −9.6%, they noted.

Detailed payment information provided for 15 of the 46 procedures shows that only intermediate repair (+4.5%) and benign destruction (+2.3%) joined biopsies and shave excisions with increased reimbursement from 2007 to 2021. The smallest drop among the other procedures was –1.9% for malignant destruction, the research team reported.

The inflation-adjusted, year-by-year analysis showed that reimbursement for the nine procedure categories has gradually declined since peaking in 2011, with the most notable exceptions being biopsies and shave excisions. Both had been following the trend until 2013, when reimbursement for shave removals jumped by almost 30 percentage points, and 2019, when rates for biopsies soared by more than 30 percentage points, according to the investigators.

The increase for skin biopsies followed the split of the original CPT code into three categories, but “the jump in reimbursement for shave removals in 2013 requires further investigation,” Mr. Mazmudar and associates wrote.

The investigators did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

according to a new analysis.

Large increases in mean reimbursement for skin biopsies (+30.3%) and shave removal (+24.6%) were not enough to offset lower rates for procedures such as simple repair (–38.7%), premalignant destruction (–19.6%), Mohs micrographic surgery (–14.4%), and flap repair (–14.1%), Rishabh S. Mazmudar, BS, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, and associates said.

“Given Medicare’s contribution to a large proportion of health care expenditures, changes in Medicare reimbursement rates may result in parallel changes in private insurance reimbursement,” they wrote in JAMA Dermatology.

A recently published study showed that Medicare reimbursement for 20 dermatologic service codes had fallen by 10% between the two comparison years, 2000 and 2020. The current study expanded the number of procedures to 46 (divided into nine categories) and used historical Medicare fee schedules to examine annual trends over a 15-year period, Mr. Mazmudar and associates explained.

Other specialties have seen reimbursement fall by more than 4.8%, including emergency medicine (–21.2% from 2000 to 2020) and general surgery (–24.4% from 2000 to 2018), but “these comparisons are likely skewed by the disproportionate increase in reimbursement rates for biopsies and shave removals during this time period,” the investigators said.

If those two procedure categories were excluded from the analysis, the mean change in overall reimbursement for the remaining dermatologic procedures would be −9.6%, they noted.

Detailed payment information provided for 15 of the 46 procedures shows that only intermediate repair (+4.5%) and benign destruction (+2.3%) joined biopsies and shave excisions with increased reimbursement from 2007 to 2021. The smallest drop among the other procedures was –1.9% for malignant destruction, the research team reported.

The inflation-adjusted, year-by-year analysis showed that reimbursement for the nine procedure categories has gradually declined since peaking in 2011, with the most notable exceptions being biopsies and shave excisions. Both had been following the trend until 2013, when reimbursement for shave removals jumped by almost 30 percentage points, and 2019, when rates for biopsies soared by more than 30 percentage points, according to the investigators.

The increase for skin biopsies followed the split of the original CPT code into three categories, but “the jump in reimbursement for shave removals in 2013 requires further investigation,” Mr. Mazmudar and associates wrote.

The investigators did not disclose any conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Beware patients’ health plans that skirt state laws on specialty drug access

There is a dangerous trend in our country in which employers, seeking to reduce health plan costs they pay, enter into agreements with small third-party administrators that “carve out” specialty drug benefits from their self-funded health insurance plan. What employers are not told is that these spending reductions are accomplished by risking the health of their employees. It is the self-funded businesses that are being preyed upon by these administrators because there is a lot of money to be made by carving out the specialty drugs in their self-funded health plan.

Let’s start with a little primer on “fully insured” versus “self-funded” health plans. As a small business owner, I understand the need to make sure that expenses don’t outpace revenue if I want to keep my doors open. One of the largest expenses for any business is health insurance. My private rheumatology practice uses a fully insured health plan. In a fully insured plan, the insurer is the party taking the financial risk. We pay the premiums, and the insurance company pays the bills after the deductible is met. It may cost more in premiums than a self-funded plan, but if an employee has an accident or severe illness, our practice is not responsible for the cost of care.

On the other hand, large and small businesses that are self-funded cover the health costs of their employees themselves. These businesses will hire a third-party administrator to pay the bills out of an account that is supplied with money from the business owner. Looking at the insurance card of your patient is one way to tell if they are covered by a fully insured or self-funded plan. If the insurance card says the plan is “administered by” the insurer or “administrative services only,” it is most likely a self-funded plan. If their insurance card states “underwritten by” the insurer on the card then it is likely a fully insured plan. This becomes important because self-funded plans are not subject to the jurisdiction of state laws such as utilization management reform. These state laws are preempted from applying to self-funded plans by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. The Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association Supreme Court case took up the question of whether certain state laws impermissibly applied or were connected to self-funded plans. The ruling in favor of Rutledge opens the door that certain state legislation may one day apply to self-funded plans.

Specialty drug benefit carve outs are not in best interests of employees, employers

This piece is not about Rutledge but about the small third-party administrators that are convincing self-funded businesses to let them “carve out” specialty drug benefits from the larger administrator of the plan by promising huge savings in the employer’s specialty drug spending. Two such companies that have come to the attention of the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organizations are Vivio Health and Archimedes. CSRO has received numerous complaints from rheumatologists regarding interference from these two entities with their clinical decision making and disregard for standard of care.