User login

US Alcohol-Related Deaths Double Over 2 Decades, With Notable Age and Gender Disparities

TOPLINE:

US alcohol-related mortality rates increased from 10.7 to 21.6 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2020, with the largest rise of 3.8-fold observed in adults aged 25-34 years. Women experienced a 2.5-fold increase, while the Midwest region showed a similar rise in mortality rates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Analysis utilized the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research to examine alcohol-related mortality trends from 1999 to 2020.

- Researchers analyzed data from a total US population of 180,408,769 people aged 25 to 85+ years in 1999 and 226,635,013 people in 2020.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were used to identify deaths with alcohol attribution, including mental and behavioral disorders, alcoholic organ damage, and alcohol-related poisoning.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall mortality rates increased from 10.7 (95% CI, 10.6-10.8) per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 (95% CI, 21.4-21.8) per 100,000 in 2020, representing a significant twofold increase.

- Adults aged 55-64 years demonstrated both the steepest increase and highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020.

- American Indian and Alaska Native individuals experienced the steepest increase and highest absolute rates among all racial groups.

- The West region maintained the highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020, despite the Midwest showing the largest increase.

IN PRACTICE:

“Individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol tend to have the highest risks of total mortality as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease deaths are predominantly due to myocardial infarction and stroke. To mitigate these risks, health providers may wish to implement screening for alcohol use in primary care and other healthcare settings. By providing brief interventions and referrals to treatment, healthcare providers would be able to achieve the early identification of individuals at risk of alcohol-related harm and offer them the support and resources they need to reduce their alcohol consumption,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Alexandra Matarazzo, BS, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. It was published online in The American Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the authors, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the study to descriptive analysis only, making it suitable for hypothesis generation but not hypothesis testing. While the validity and generalizability within the United States are secure because of the use of complete population data, potential bias and uncontrolled confounding may exist because of different population mixes between the two time points.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. One coauthor disclosed serving as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC, to the Food and Drug Administration, and to Up to Date. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

US alcohol-related mortality rates increased from 10.7 to 21.6 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2020, with the largest rise of 3.8-fold observed in adults aged 25-34 years. Women experienced a 2.5-fold increase, while the Midwest region showed a similar rise in mortality rates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Analysis utilized the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research to examine alcohol-related mortality trends from 1999 to 2020.

- Researchers analyzed data from a total US population of 180,408,769 people aged 25 to 85+ years in 1999 and 226,635,013 people in 2020.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were used to identify deaths with alcohol attribution, including mental and behavioral disorders, alcoholic organ damage, and alcohol-related poisoning.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall mortality rates increased from 10.7 (95% CI, 10.6-10.8) per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 (95% CI, 21.4-21.8) per 100,000 in 2020, representing a significant twofold increase.

- Adults aged 55-64 years demonstrated both the steepest increase and highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020.

- American Indian and Alaska Native individuals experienced the steepest increase and highest absolute rates among all racial groups.

- The West region maintained the highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020, despite the Midwest showing the largest increase.

IN PRACTICE:

“Individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol tend to have the highest risks of total mortality as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease deaths are predominantly due to myocardial infarction and stroke. To mitigate these risks, health providers may wish to implement screening for alcohol use in primary care and other healthcare settings. By providing brief interventions and referrals to treatment, healthcare providers would be able to achieve the early identification of individuals at risk of alcohol-related harm and offer them the support and resources they need to reduce their alcohol consumption,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Alexandra Matarazzo, BS, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. It was published online in The American Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the authors, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the study to descriptive analysis only, making it suitable for hypothesis generation but not hypothesis testing. While the validity and generalizability within the United States are secure because of the use of complete population data, potential bias and uncontrolled confounding may exist because of different population mixes between the two time points.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. One coauthor disclosed serving as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC, to the Food and Drug Administration, and to Up to Date. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

US alcohol-related mortality rates increased from 10.7 to 21.6 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2020, with the largest rise of 3.8-fold observed in adults aged 25-34 years. Women experienced a 2.5-fold increase, while the Midwest region showed a similar rise in mortality rates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Analysis utilized the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research to examine alcohol-related mortality trends from 1999 to 2020.

- Researchers analyzed data from a total US population of 180,408,769 people aged 25 to 85+ years in 1999 and 226,635,013 people in 2020.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were used to identify deaths with alcohol attribution, including mental and behavioral disorders, alcoholic organ damage, and alcohol-related poisoning.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall mortality rates increased from 10.7 (95% CI, 10.6-10.8) per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 (95% CI, 21.4-21.8) per 100,000 in 2020, representing a significant twofold increase.

- Adults aged 55-64 years demonstrated both the steepest increase and highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020.

- American Indian and Alaska Native individuals experienced the steepest increase and highest absolute rates among all racial groups.

- The West region maintained the highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020, despite the Midwest showing the largest increase.

IN PRACTICE:

“Individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol tend to have the highest risks of total mortality as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease deaths are predominantly due to myocardial infarction and stroke. To mitigate these risks, health providers may wish to implement screening for alcohol use in primary care and other healthcare settings. By providing brief interventions and referrals to treatment, healthcare providers would be able to achieve the early identification of individuals at risk of alcohol-related harm and offer them the support and resources they need to reduce their alcohol consumption,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Alexandra Matarazzo, BS, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. It was published online in The American Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the authors, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the study to descriptive analysis only, making it suitable for hypothesis generation but not hypothesis testing. While the validity and generalizability within the United States are secure because of the use of complete population data, potential bias and uncontrolled confounding may exist because of different population mixes between the two time points.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. One coauthor disclosed serving as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC, to the Food and Drug Administration, and to Up to Date. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Deprescribe Low-Value Meds to Reduce Polypharmacy Harms

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA — While polypharmacy is inevitable for patients with multiple chronic diseases, not all medications improve patient-oriented outcomes, members of the Patients, Experience, Evidence, Research (PEER) team, a group of Canadian primary care professionals who develop evidence-based guidelines, told attendees at the Family Medicine Forum (FMF) 2024.

In a thought-provoking presentation called “Axe the Rx: Deprescribing Chronic Medications with PEER,” the panelists gave examples of medications that may be safely stopped or tapered, particularly for older adults “whose pill bag is heavier than their lunch bag.”

Curbing Cardiovascular Drugs

The 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults call for reaching an LDL-C < 1.8 mmol/L in secondary cardiovascular prevention by potentially adding on medical therapies such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors or ezetimibe or both if that target is not reached with the maximal dosage of a statin.

But family physicians do not need to follow this guidance for their patients who have had a myocardial infarction, said Ontario family physician Jennifer Young, MD, a physician advisor in the Canadian College of Family Physicians’ Knowledge Experts and Tools Program.

Treating to below 1.8 mmol/L “means lab testing for the patients,” Young told this news organization. “It means increasing doses [of a statin] to try and get to that level.” If the patient is already on the highest dose of a statin, it means adding other medications that lower cholesterol.

“If that was translating into better outcomes like [preventing] death and another heart attack, then all of that extra effort would be worth it,” said Young. “But we don’t have evidence that it actually does have a benefit for outcomes like death and repeated heart attacks,” compared with putting them on a high dose of a potent statin.

Tapering Opioids

Before placing patients on an opioid taper, clinicians should first assess them for opioid use disorder (OUD), said Jessica Kirkwood, MD, assistant professor of family medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. She suggested using the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index questionnaire to do so.

Clinicians should be much more careful in initiating a taper with patients with OUD, said Kirkwood. They must ensure that these patients are motivated to discontinue their opioids. “We’re losing 21 Canadians a day to the opioid crisis. We all know that cutting someone off their opioids and potentially having them seek opioids elsewhere through illicit means can be fatal.”

In addition, clinicians should spend more time counseling patients with OUD than those without, Kirkwood continued. They must explain to these patients how they are being tapered (eg, the intervals and doses) and highlight the benefits of a taper, such as reduced constipation. Opioid agonist therapy (such as methadone or buprenorphine) can be considered in these patients.

Some research has pointed to the importance of patient motivation as a factor in the success of opioid tapers, noted Kirkwood.

Deprescribing Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, too, often can be deprescribed. These drugs should not be prescribed to promote sleep on a long-term basis. Yet clinicians commonly encounter patients who have been taking them for more than a year, said pharmacist Betsy Thomas, assistant adjunct professor of family medicine at the University of Alberta.

The medications “are usually fairly effective for the first couple of weeks to about a month, and then the benefits start to decrease, and we start to see more harms,” she said.

Some of the harms that have been associated with continued use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists include delayed reaction time and impaired cognition, which can affect the ability to drive, the risk for falls, and the risk for hip fractures, she noted. Some research suggests that these drugs are not an option for treating insomnia in patients aged 65 years or older.

Clinicians should encourage tapering the use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists to minimize dependence and transition patients to nonpharmacologic approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy to manage insomnia, she said. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of the intervention, and Thomas suggested that family physicians visit the mysleepwell.ca website for more information.

Young, Kirkwood, and Thomas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA — While polypharmacy is inevitable for patients with multiple chronic diseases, not all medications improve patient-oriented outcomes, members of the Patients, Experience, Evidence, Research (PEER) team, a group of Canadian primary care professionals who develop evidence-based guidelines, told attendees at the Family Medicine Forum (FMF) 2024.

In a thought-provoking presentation called “Axe the Rx: Deprescribing Chronic Medications with PEER,” the panelists gave examples of medications that may be safely stopped or tapered, particularly for older adults “whose pill bag is heavier than their lunch bag.”

Curbing Cardiovascular Drugs

The 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults call for reaching an LDL-C < 1.8 mmol/L in secondary cardiovascular prevention by potentially adding on medical therapies such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors or ezetimibe or both if that target is not reached with the maximal dosage of a statin.

But family physicians do not need to follow this guidance for their patients who have had a myocardial infarction, said Ontario family physician Jennifer Young, MD, a physician advisor in the Canadian College of Family Physicians’ Knowledge Experts and Tools Program.

Treating to below 1.8 mmol/L “means lab testing for the patients,” Young told this news organization. “It means increasing doses [of a statin] to try and get to that level.” If the patient is already on the highest dose of a statin, it means adding other medications that lower cholesterol.

“If that was translating into better outcomes like [preventing] death and another heart attack, then all of that extra effort would be worth it,” said Young. “But we don’t have evidence that it actually does have a benefit for outcomes like death and repeated heart attacks,” compared with putting them on a high dose of a potent statin.

Tapering Opioids

Before placing patients on an opioid taper, clinicians should first assess them for opioid use disorder (OUD), said Jessica Kirkwood, MD, assistant professor of family medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. She suggested using the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index questionnaire to do so.

Clinicians should be much more careful in initiating a taper with patients with OUD, said Kirkwood. They must ensure that these patients are motivated to discontinue their opioids. “We’re losing 21 Canadians a day to the opioid crisis. We all know that cutting someone off their opioids and potentially having them seek opioids elsewhere through illicit means can be fatal.”

In addition, clinicians should spend more time counseling patients with OUD than those without, Kirkwood continued. They must explain to these patients how they are being tapered (eg, the intervals and doses) and highlight the benefits of a taper, such as reduced constipation. Opioid agonist therapy (such as methadone or buprenorphine) can be considered in these patients.

Some research has pointed to the importance of patient motivation as a factor in the success of opioid tapers, noted Kirkwood.

Deprescribing Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, too, often can be deprescribed. These drugs should not be prescribed to promote sleep on a long-term basis. Yet clinicians commonly encounter patients who have been taking them for more than a year, said pharmacist Betsy Thomas, assistant adjunct professor of family medicine at the University of Alberta.

The medications “are usually fairly effective for the first couple of weeks to about a month, and then the benefits start to decrease, and we start to see more harms,” she said.

Some of the harms that have been associated with continued use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists include delayed reaction time and impaired cognition, which can affect the ability to drive, the risk for falls, and the risk for hip fractures, she noted. Some research suggests that these drugs are not an option for treating insomnia in patients aged 65 years or older.

Clinicians should encourage tapering the use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists to minimize dependence and transition patients to nonpharmacologic approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy to manage insomnia, she said. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of the intervention, and Thomas suggested that family physicians visit the mysleepwell.ca website for more information.

Young, Kirkwood, and Thomas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

VANCOUVER, BRITISH COLUMBIA — While polypharmacy is inevitable for patients with multiple chronic diseases, not all medications improve patient-oriented outcomes, members of the Patients, Experience, Evidence, Research (PEER) team, a group of Canadian primary care professionals who develop evidence-based guidelines, told attendees at the Family Medicine Forum (FMF) 2024.

In a thought-provoking presentation called “Axe the Rx: Deprescribing Chronic Medications with PEER,” the panelists gave examples of medications that may be safely stopped or tapered, particularly for older adults “whose pill bag is heavier than their lunch bag.”

Curbing Cardiovascular Drugs

The 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults call for reaching an LDL-C < 1.8 mmol/L in secondary cardiovascular prevention by potentially adding on medical therapies such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors or ezetimibe or both if that target is not reached with the maximal dosage of a statin.

But family physicians do not need to follow this guidance for their patients who have had a myocardial infarction, said Ontario family physician Jennifer Young, MD, a physician advisor in the Canadian College of Family Physicians’ Knowledge Experts and Tools Program.

Treating to below 1.8 mmol/L “means lab testing for the patients,” Young told this news organization. “It means increasing doses [of a statin] to try and get to that level.” If the patient is already on the highest dose of a statin, it means adding other medications that lower cholesterol.

“If that was translating into better outcomes like [preventing] death and another heart attack, then all of that extra effort would be worth it,” said Young. “But we don’t have evidence that it actually does have a benefit for outcomes like death and repeated heart attacks,” compared with putting them on a high dose of a potent statin.

Tapering Opioids

Before placing patients on an opioid taper, clinicians should first assess them for opioid use disorder (OUD), said Jessica Kirkwood, MD, assistant professor of family medicine at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada. She suggested using the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index questionnaire to do so.

Clinicians should be much more careful in initiating a taper with patients with OUD, said Kirkwood. They must ensure that these patients are motivated to discontinue their opioids. “We’re losing 21 Canadians a day to the opioid crisis. We all know that cutting someone off their opioids and potentially having them seek opioids elsewhere through illicit means can be fatal.”

In addition, clinicians should spend more time counseling patients with OUD than those without, Kirkwood continued. They must explain to these patients how they are being tapered (eg, the intervals and doses) and highlight the benefits of a taper, such as reduced constipation. Opioid agonist therapy (such as methadone or buprenorphine) can be considered in these patients.

Some research has pointed to the importance of patient motivation as a factor in the success of opioid tapers, noted Kirkwood.

Deprescribing Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, too, often can be deprescribed. These drugs should not be prescribed to promote sleep on a long-term basis. Yet clinicians commonly encounter patients who have been taking them for more than a year, said pharmacist Betsy Thomas, assistant adjunct professor of family medicine at the University of Alberta.

The medications “are usually fairly effective for the first couple of weeks to about a month, and then the benefits start to decrease, and we start to see more harms,” she said.

Some of the harms that have been associated with continued use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists include delayed reaction time and impaired cognition, which can affect the ability to drive, the risk for falls, and the risk for hip fractures, she noted. Some research suggests that these drugs are not an option for treating insomnia in patients aged 65 years or older.

Clinicians should encourage tapering the use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists to minimize dependence and transition patients to nonpharmacologic approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy to manage insomnia, she said. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of the intervention, and Thomas suggested that family physicians visit the mysleepwell.ca website for more information.

Young, Kirkwood, and Thomas reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM FMF 2024

As Populations Age, Occam’s Razor Loses Its Diagnostic Edge

The principle of parsimony, often referred to as “Occam’s razor,” favors a unifying explanation over multiple ones, as long as both explain the data equally well. This heuristic, widely used in medical practice, advocates for simpler explanations rather than complex theories. However, its application in modern medicine has sparked debate.

“Hickam’s dictum,” a counterargument to Occam’s razor, asserts that patients — especially as populations grow older and more fragile — can simultaneously have multiple, unrelated diagnoses. These contrasting perspectives on clinical reasoning, balancing diagnostic simplicity and complexity, are both used in daily medical practice.

But are these two axioms truly in conflict, or is this a false dichotomy?

Occam’s Razor and Simple Diagnoses

Interpersonal variability in diagnostic approaches, shaped by the subjective nature of many judgments, complicates the formal evaluation of diagnostic parsimony (Occam’s razor). Indirect evidence suggests that prioritizing simplicity in diagnosis can result in under-detection of secondary conditions, particularly in patients with chronic illnesses.

For example, older patients with a known chronic illness were found to have a 30%-60% lower likelihood of being treated for an unrelated secondary diagnosis than matched peers without the chronic condition. Other studies indicate that a readily available, simple diagnosis can lead clinicians to prematurely close their diagnostic reasoning, overlooking other significant illnesses.

Beyond Hickam’s Dictum and Occam’s Razor

A recent study explored the phenomenon of multiple diagnoses by examining the supposed conflict between Hickam’s dictum and Occam’s razor, as well as the ambiguities in how they are interpreted and used by physicians in clinical reasoning.

Part 1: Researchers identified articles on PubMed related to Hickam’s dictum or conflicting with Occam’s razor, categorizing instances into four models of Hickam’s dictum:

1. Incidentaloma: An asymptomatic condition discovered accidentally.

2. Preexisting diagnosis: A known condition in the patient’s medical history.

3. Causally related disease: A complication, association, epiphenomenon, or underlying cause connected to the primary diagnosis.

4. Coincidental and independent disease: A symptomatic condition unrelated to the primary diagnosis.

Part 2: Researchers analyzed 220 case records from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and clinical problem-solving reports published in The New England Journal of Medicine between 2017 and 2023. They found no cases where the final diagnosis was not a unifying one.

Part 3: In an online survey of 265 physicians, 79% identified coincidental symptomatic conditions (category 4) as the least likely type of multiple diagnoses. Preexisting conditions (category 2) emerged as the most common, reflecting the tendency to add new diagnoses to a patient’s existing health profile. Almost one third of instances referencing Hickam’s dictum or violations of Occam’s razor fell into category 2.

Causally related diseases (category 3) were probabilistically dependent, meaning that the presence of one condition increased the likelihood of the other, based on the strength (often unknown) of the causal relationship.

Practical Insights

The significant finding of this work was that multiple diagnoses occur in predictable patterns, informed by causal connections between conditions, symptom onset timing, and likelihood. The principle of common causation supports the search for a unifying diagnosis for coincidental symptoms. It is not surprising that causally related phenomena often co-occur, as reflected by the fact that 40% of multiple diagnoses in the study’s first part were causally linked.

Thus, understanding multiple diagnoses goes beyond Hickam’s dictum and Occam’s razor. It requires not only identifying diseases but also examining their causal relationships and the timing of symptom onset. A unifying diagnosis is not equivalent to a single diagnosis; rather, it represents a causal pathway linking underlying pathologic changes to acute presentations.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The principle of parsimony, often referred to as “Occam’s razor,” favors a unifying explanation over multiple ones, as long as both explain the data equally well. This heuristic, widely used in medical practice, advocates for simpler explanations rather than complex theories. However, its application in modern medicine has sparked debate.

“Hickam’s dictum,” a counterargument to Occam’s razor, asserts that patients — especially as populations grow older and more fragile — can simultaneously have multiple, unrelated diagnoses. These contrasting perspectives on clinical reasoning, balancing diagnostic simplicity and complexity, are both used in daily medical practice.

But are these two axioms truly in conflict, or is this a false dichotomy?

Occam’s Razor and Simple Diagnoses

Interpersonal variability in diagnostic approaches, shaped by the subjective nature of many judgments, complicates the formal evaluation of diagnostic parsimony (Occam’s razor). Indirect evidence suggests that prioritizing simplicity in diagnosis can result in under-detection of secondary conditions, particularly in patients with chronic illnesses.

For example, older patients with a known chronic illness were found to have a 30%-60% lower likelihood of being treated for an unrelated secondary diagnosis than matched peers without the chronic condition. Other studies indicate that a readily available, simple diagnosis can lead clinicians to prematurely close their diagnostic reasoning, overlooking other significant illnesses.

Beyond Hickam’s Dictum and Occam’s Razor

A recent study explored the phenomenon of multiple diagnoses by examining the supposed conflict between Hickam’s dictum and Occam’s razor, as well as the ambiguities in how they are interpreted and used by physicians in clinical reasoning.

Part 1: Researchers identified articles on PubMed related to Hickam’s dictum or conflicting with Occam’s razor, categorizing instances into four models of Hickam’s dictum:

1. Incidentaloma: An asymptomatic condition discovered accidentally.

2. Preexisting diagnosis: A known condition in the patient’s medical history.

3. Causally related disease: A complication, association, epiphenomenon, or underlying cause connected to the primary diagnosis.

4. Coincidental and independent disease: A symptomatic condition unrelated to the primary diagnosis.

Part 2: Researchers analyzed 220 case records from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and clinical problem-solving reports published in The New England Journal of Medicine between 2017 and 2023. They found no cases where the final diagnosis was not a unifying one.

Part 3: In an online survey of 265 physicians, 79% identified coincidental symptomatic conditions (category 4) as the least likely type of multiple diagnoses. Preexisting conditions (category 2) emerged as the most common, reflecting the tendency to add new diagnoses to a patient’s existing health profile. Almost one third of instances referencing Hickam’s dictum or violations of Occam’s razor fell into category 2.

Causally related diseases (category 3) were probabilistically dependent, meaning that the presence of one condition increased the likelihood of the other, based on the strength (often unknown) of the causal relationship.

Practical Insights

The significant finding of this work was that multiple diagnoses occur in predictable patterns, informed by causal connections between conditions, symptom onset timing, and likelihood. The principle of common causation supports the search for a unifying diagnosis for coincidental symptoms. It is not surprising that causally related phenomena often co-occur, as reflected by the fact that 40% of multiple diagnoses in the study’s first part were causally linked.

Thus, understanding multiple diagnoses goes beyond Hickam’s dictum and Occam’s razor. It requires not only identifying diseases but also examining their causal relationships and the timing of symptom onset. A unifying diagnosis is not equivalent to a single diagnosis; rather, it represents a causal pathway linking underlying pathologic changes to acute presentations.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The principle of parsimony, often referred to as “Occam’s razor,” favors a unifying explanation over multiple ones, as long as both explain the data equally well. This heuristic, widely used in medical practice, advocates for simpler explanations rather than complex theories. However, its application in modern medicine has sparked debate.

“Hickam’s dictum,” a counterargument to Occam’s razor, asserts that patients — especially as populations grow older and more fragile — can simultaneously have multiple, unrelated diagnoses. These contrasting perspectives on clinical reasoning, balancing diagnostic simplicity and complexity, are both used in daily medical practice.

But are these two axioms truly in conflict, or is this a false dichotomy?

Occam’s Razor and Simple Diagnoses

Interpersonal variability in diagnostic approaches, shaped by the subjective nature of many judgments, complicates the formal evaluation of diagnostic parsimony (Occam’s razor). Indirect evidence suggests that prioritizing simplicity in diagnosis can result in under-detection of secondary conditions, particularly in patients with chronic illnesses.

For example, older patients with a known chronic illness were found to have a 30%-60% lower likelihood of being treated for an unrelated secondary diagnosis than matched peers without the chronic condition. Other studies indicate that a readily available, simple diagnosis can lead clinicians to prematurely close their diagnostic reasoning, overlooking other significant illnesses.

Beyond Hickam’s Dictum and Occam’s Razor

A recent study explored the phenomenon of multiple diagnoses by examining the supposed conflict between Hickam’s dictum and Occam’s razor, as well as the ambiguities in how they are interpreted and used by physicians in clinical reasoning.

Part 1: Researchers identified articles on PubMed related to Hickam’s dictum or conflicting with Occam’s razor, categorizing instances into four models of Hickam’s dictum:

1. Incidentaloma: An asymptomatic condition discovered accidentally.

2. Preexisting diagnosis: A known condition in the patient’s medical history.

3. Causally related disease: A complication, association, epiphenomenon, or underlying cause connected to the primary diagnosis.

4. Coincidental and independent disease: A symptomatic condition unrelated to the primary diagnosis.

Part 2: Researchers analyzed 220 case records from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and clinical problem-solving reports published in The New England Journal of Medicine between 2017 and 2023. They found no cases where the final diagnosis was not a unifying one.

Part 3: In an online survey of 265 physicians, 79% identified coincidental symptomatic conditions (category 4) as the least likely type of multiple diagnoses. Preexisting conditions (category 2) emerged as the most common, reflecting the tendency to add new diagnoses to a patient’s existing health profile. Almost one third of instances referencing Hickam’s dictum or violations of Occam’s razor fell into category 2.

Causally related diseases (category 3) were probabilistically dependent, meaning that the presence of one condition increased the likelihood of the other, based on the strength (often unknown) of the causal relationship.

Practical Insights

The significant finding of this work was that multiple diagnoses occur in predictable patterns, informed by causal connections between conditions, symptom onset timing, and likelihood. The principle of common causation supports the search for a unifying diagnosis for coincidental symptoms. It is not surprising that causally related phenomena often co-occur, as reflected by the fact that 40% of multiple diagnoses in the study’s first part were causally linked.

Thus, understanding multiple diagnoses goes beyond Hickam’s dictum and Occam’s razor. It requires not only identifying diseases but also examining their causal relationships and the timing of symptom onset. A unifying diagnosis is not equivalent to a single diagnosis; rather, it represents a causal pathway linking underlying pathologic changes to acute presentations.

This story was translated from Univadis Italy using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Aliens, Ian McShane, and Heart Disease Risk

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

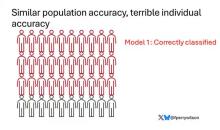

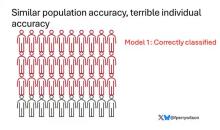

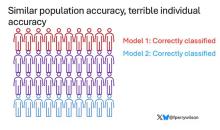

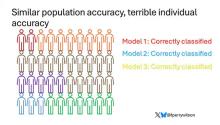

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Sitting for More Than 10 Hours Daily Ups Heart Disease Risk

TOPLINE:

Sedentary time exceeding 10.6 h/d is linked to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular (CV) mortality, researchers found. The risk persists even in individuals who meet recommended physical activity levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a validated machine learning approach to investigate the relationships between sedentary behavior and the future risks for CV illness and mortality in 89,530 middle-aged and older adults (mean age, 62 years; 56% women) from the UK Biobank.

- Participants provided data from a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer that recorded their movements over a period of 7 days.

- Machine learning algorithms classified accelerometer signals into four classes of activities: Sleep, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity.

- Participants were followed up for a median of 8 years through linkage to national health-related datasets in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- The median sedentary time was 9.4 h/d.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period, 3638 individuals (4.9%) experienced incident atrial fibrillation, 1854 (2.09%) developed incident heart failure, 1610 (1.84%) experienced incident myocardial infarction, and 846 (0.94%) died from cardiovascular causes.

- The risks for atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction increased steadily with an increase in sedentary time, with sedentary time greater than 10.6 h/d showing a modest increase in risk for atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21).

- The risks for heart failure and CV mortality were low until sedentary time surpassed approximately 10.6 h/d, after which they rose by 45% (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65) and 62% (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.34-1.96), respectively.

- The associations were attenuated but remained significant for CV mortality (HR, 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07-1.64) in individuals who met the recommended levels for physical activity yet were sedentary for more than 10.6 h/d. Reallocating 30 minutes of sedentary time to other activities reduced the risk for heart failure (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) among those who were sedentary more than 10.6 h/d.

IN PRACTICE:

The study “highlights a complex interplay between sedentary behavior and physical activity, ultimately suggesting that sedentary behavior remains relevant for CV disease risk even among individuals meeting sufficient” levels of activity, the researchers reported.

“Individuals should move more and be less sedentary to reduce CV risk. ... Being a ‘weekend warrior’ and meeting guideline levels of [moderate to vigorous physical activity] of 150 minutes/week will not completely abolish the deleterious effects of extended sedentary time of > 10.6 hours per day,” Charles B. Eaton, MD, MS, of the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ezimamaka Ajufo, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It was published online on November 15, 2024, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Wrist-based accelerometers cannot assess specific contexts for sedentary behavior and may misclassify standing time as sedentary time, and these limitations may have affected the findings. Physical activity was measured for 1 week only, which might not have fully represented habitual activity patterns. The sample included predominantly White participants and was enriched for health and socioeconomic status, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors disclosed receiving research support, grants, and research fellowships and collaborations from various institutions and pharmaceutical companies, as well as serving on their advisory boards.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Sedentary time exceeding 10.6 h/d is linked to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular (CV) mortality, researchers found. The risk persists even in individuals who meet recommended physical activity levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a validated machine learning approach to investigate the relationships between sedentary behavior and the future risks for CV illness and mortality in 89,530 middle-aged and older adults (mean age, 62 years; 56% women) from the UK Biobank.

- Participants provided data from a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer that recorded their movements over a period of 7 days.

- Machine learning algorithms classified accelerometer signals into four classes of activities: Sleep, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity.

- Participants were followed up for a median of 8 years through linkage to national health-related datasets in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- The median sedentary time was 9.4 h/d.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period, 3638 individuals (4.9%) experienced incident atrial fibrillation, 1854 (2.09%) developed incident heart failure, 1610 (1.84%) experienced incident myocardial infarction, and 846 (0.94%) died from cardiovascular causes.

- The risks for atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction increased steadily with an increase in sedentary time, with sedentary time greater than 10.6 h/d showing a modest increase in risk for atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21).

- The risks for heart failure and CV mortality were low until sedentary time surpassed approximately 10.6 h/d, after which they rose by 45% (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65) and 62% (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.34-1.96), respectively.

- The associations were attenuated but remained significant for CV mortality (HR, 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07-1.64) in individuals who met the recommended levels for physical activity yet were sedentary for more than 10.6 h/d. Reallocating 30 minutes of sedentary time to other activities reduced the risk for heart failure (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) among those who were sedentary more than 10.6 h/d.

IN PRACTICE:

The study “highlights a complex interplay between sedentary behavior and physical activity, ultimately suggesting that sedentary behavior remains relevant for CV disease risk even among individuals meeting sufficient” levels of activity, the researchers reported.

“Individuals should move more and be less sedentary to reduce CV risk. ... Being a ‘weekend warrior’ and meeting guideline levels of [moderate to vigorous physical activity] of 150 minutes/week will not completely abolish the deleterious effects of extended sedentary time of > 10.6 hours per day,” Charles B. Eaton, MD, MS, of the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ezimamaka Ajufo, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It was published online on November 15, 2024, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Wrist-based accelerometers cannot assess specific contexts for sedentary behavior and may misclassify standing time as sedentary time, and these limitations may have affected the findings. Physical activity was measured for 1 week only, which might not have fully represented habitual activity patterns. The sample included predominantly White participants and was enriched for health and socioeconomic status, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors disclosed receiving research support, grants, and research fellowships and collaborations from various institutions and pharmaceutical companies, as well as serving on their advisory boards.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Sedentary time exceeding 10.6 h/d is linked to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular (CV) mortality, researchers found. The risk persists even in individuals who meet recommended physical activity levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a validated machine learning approach to investigate the relationships between sedentary behavior and the future risks for CV illness and mortality in 89,530 middle-aged and older adults (mean age, 62 years; 56% women) from the UK Biobank.

- Participants provided data from a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer that recorded their movements over a period of 7 days.

- Machine learning algorithms classified accelerometer signals into four classes of activities: Sleep, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity.

- Participants were followed up for a median of 8 years through linkage to national health-related datasets in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- The median sedentary time was 9.4 h/d.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period, 3638 individuals (4.9%) experienced incident atrial fibrillation, 1854 (2.09%) developed incident heart failure, 1610 (1.84%) experienced incident myocardial infarction, and 846 (0.94%) died from cardiovascular causes.

- The risks for atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction increased steadily with an increase in sedentary time, with sedentary time greater than 10.6 h/d showing a modest increase in risk for atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21).

- The risks for heart failure and CV mortality were low until sedentary time surpassed approximately 10.6 h/d, after which they rose by 45% (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65) and 62% (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.34-1.96), respectively.

- The associations were attenuated but remained significant for CV mortality (HR, 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07-1.64) in individuals who met the recommended levels for physical activity yet were sedentary for more than 10.6 h/d. Reallocating 30 minutes of sedentary time to other activities reduced the risk for heart failure (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) among those who were sedentary more than 10.6 h/d.

IN PRACTICE:

The study “highlights a complex interplay between sedentary behavior and physical activity, ultimately suggesting that sedentary behavior remains relevant for CV disease risk even among individuals meeting sufficient” levels of activity, the researchers reported.

“Individuals should move more and be less sedentary to reduce CV risk. ... Being a ‘weekend warrior’ and meeting guideline levels of [moderate to vigorous physical activity] of 150 minutes/week will not completely abolish the deleterious effects of extended sedentary time of > 10.6 hours per day,” Charles B. Eaton, MD, MS, of the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ezimamaka Ajufo, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It was published online on November 15, 2024, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Wrist-based accelerometers cannot assess specific contexts for sedentary behavior and may misclassify standing time as sedentary time, and these limitations may have affected the findings. Physical activity was measured for 1 week only, which might not have fully represented habitual activity patterns. The sample included predominantly White participants and was enriched for health and socioeconomic status, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors disclosed receiving research support, grants, and research fellowships and collaborations from various institutions and pharmaceutical companies, as well as serving on their advisory boards.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An Epidemiologist’s Guide to Debunking Nutritional Research

You’re invited to a dinner party but you struggle to make small talk. Do not worry; that will invariably crop up over cocktails. Because all journalism has been reduced to listicles, here are four ways to seem clever at dinner parties.

1. The Predinner Cocktails: A Lesson in Reverse Causation

Wine connoisseurs sniff, swirl, and gently swish the wine in their mouths before spitting out and cleansing their palates to better appreciate the subtlety of each vintage. If you’re not an oenophile, no matter. Whenever somebody claims that moderate amounts of alcohol are good for your heart, this is your moment to pounce. Interject yourself in the conversation and tell everybody about reverse causation.

Reverse causation, also known as protopathic bias, involves misinterpreting the directionality of an association. You assume that X leads to Y, when in fact Y leads to X. Temporal paradoxes are useful plot devices in science fiction movies, but they have no place in medical research. In our bland world, cause must precede effect. As such, smoking leads to lung cancer; lung cancer doesn’t make you smoke more.

But with alcohol, directionality is less obvious. Many studies of alcohol and cardiovascular disease have demonstrated a U-shaped association, with risk being lowest among those who drink moderate amounts of alcohol (usually one to two drinks per day) and higher in those who drink more and also those who drink very little.

But one must ask why some people drink little or no alcohol. There is an important difference between former drinkers and never drinkers. Former drinkers cut back for a reason. More likely than not, the reason for this newfound sobriety was medical. A new cancer diagnosis, the emergence of atrial fibrillation, the development of diabetes, or rising blood pressure are all good reasons to reduce or eliminate alcohol. A cross-sectional study will fail to capture that alcohol consumption changes over time — people who now don’t drink may have imbibed alcohol in years past. It was not abstinence that led to an increased risk for heart disease; it was the increased risk for heart disease that led to abstinence.

You see the same phenomenon with the so-called obesity paradox. The idea that being a little overweight is good for you may appeal when you no longer fit into last year’s pants. But people who are underweight are so for a reason. Malnutrition, cachexia from cancer, or some other cause is almost certainly driving up the risk at the left-hand side of the U-shaped curve that makes the middle part seem better than it actually is.

Food consumption changes over time. A cross-sectional survey at one point in time cannot accurately capture past habits and distant exposures, especially for diseases such as heart disease and cancer that develop slowly over time. Studies on alcohol that try to overcome these shortcomings by eliminating former drinkers, or by using Mendelian randomization to better account for past exposure, do not show a cardiovascular benefit for moderate red wine drinking.

2. The Hors D’oeuvres — The Importance of RCTs

Now that you have made yourself the center of attention, it is time to cement your newfound reputation as a font of scientific knowledge. Most self-respecting hosts will serve smoked salmon as an amuse-bouche before the main meal. When someone mentions the health benefits of fish oils, you should take the opportunity to teach them about confounding.

Fish, especially cold-water fish from northern climates, have relatively high amounts of omega-3 fatty acids. Despite the plethora of observational studies suggesting a cardiovascular benefit, it’s now relatively clear that fish oil or omega-3 supplements have no medical benefit.