User login

No vascular benefit of testosterone over exercise in aging men

Exercise training – but not testosterone therapy – improved vascular health in aging men with widening midsections and low to normal testosterone, new research suggests.

“Previous studies have suggested that men with higher levels of testosterone, who were more physically active, might have better health outcomes,” Bu Beng Yeap, MBBS, PhD, University of Western Australia, Perth, said in an interview. “We formulated the hypothesis that the combination of testosterone treatment and exercise training would improve the health of arteries more than either alone.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators randomly assigned 80 men, aged 50-70 years, to 12 weeks of 5% testosterone cream 2 mL applied daily or placebo plus a supervised exercise program that included machine-based resistance and aerobic (cycling) exercises two to three times a week or no additional exercise.

The men (mean age, 59 years) had low-normal testosterone (6-14 nmol/L), a waist circumference of at least 95 cm (37.4 inches), and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 1 diabetes, or other clinically significant illnesses. Current smokers and men on testosterone or medications that would alter testosterone levels were also excluded.

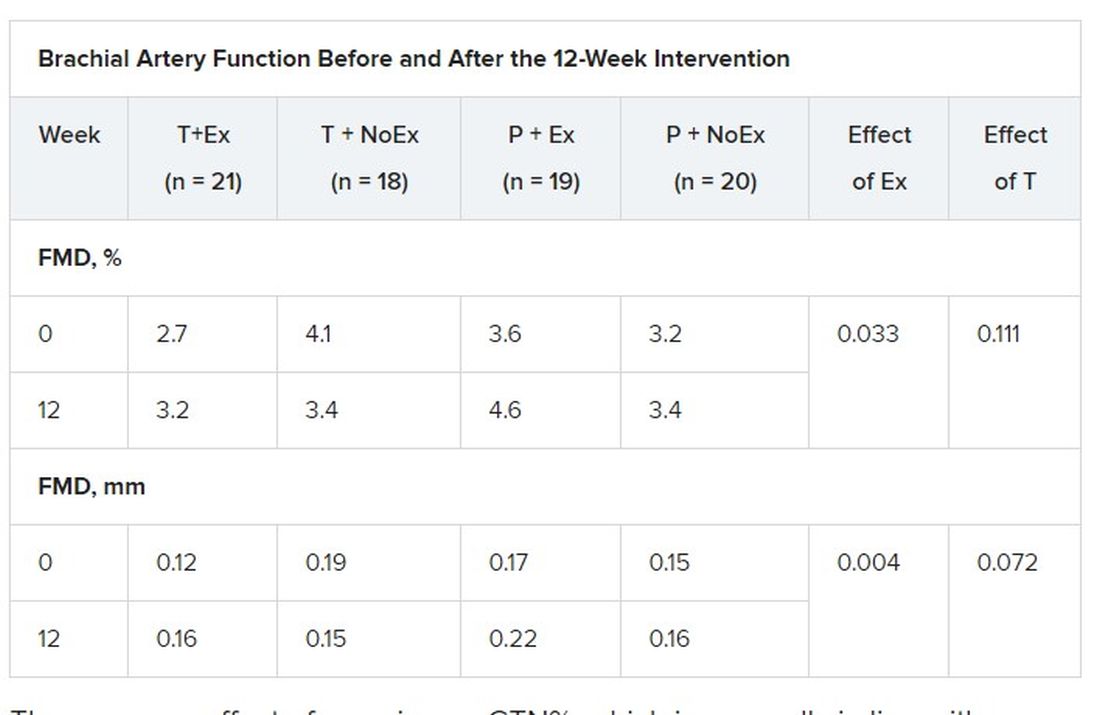

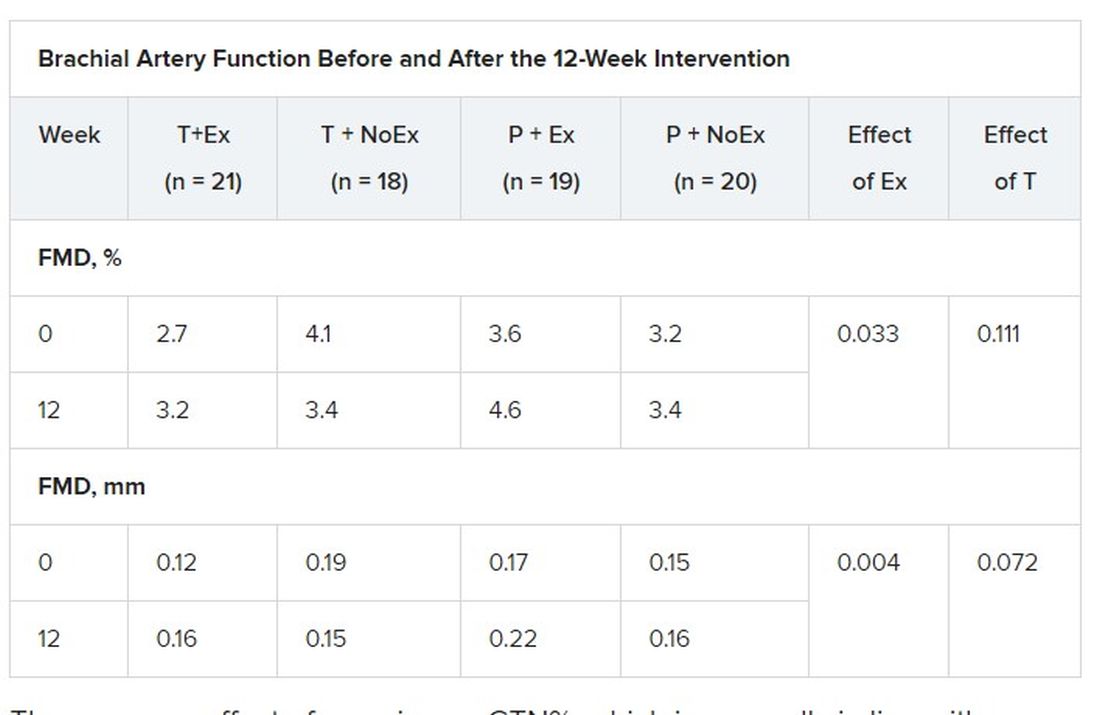

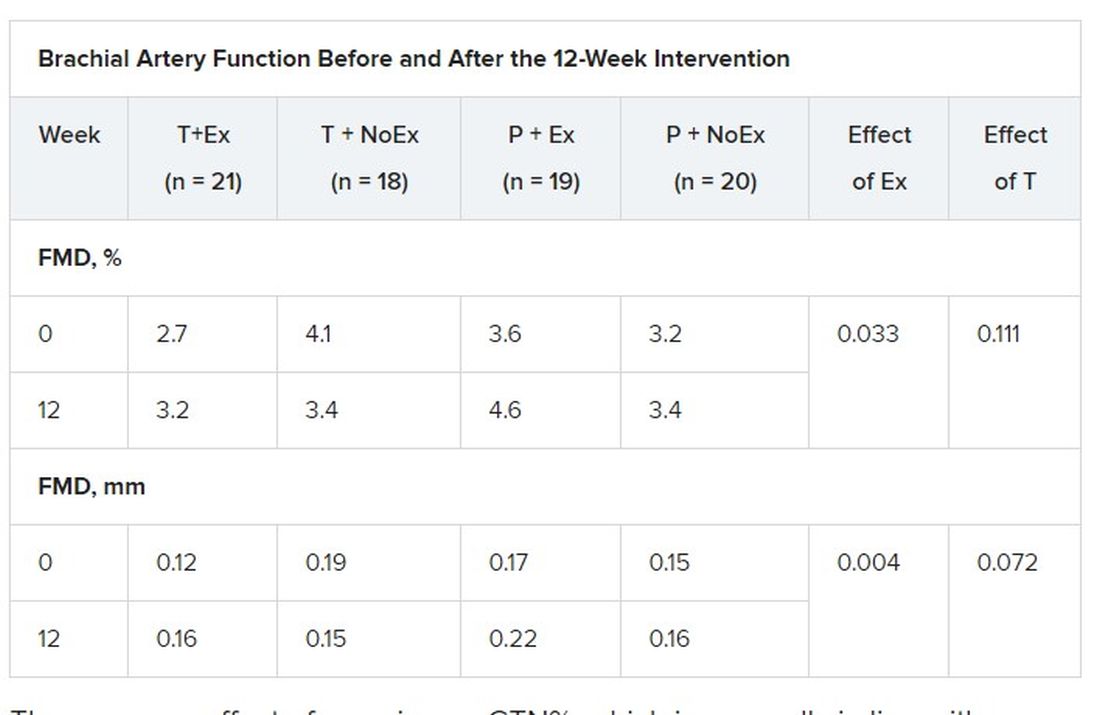

High-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery was used to assess flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) responses. FMD has been shown to be predictive of CVD risk, with a 1% increase in FMD associated with a 9%-13% decrease in future CVD events.

Based on participants’ daily dairies, testosterone adherence was 97.6%. Exercise adherence was 96.5% for twice-weekly attendance and 80.0% for thrice-weekly attendance, with no between-group differences.

As reported Feb. 22, 2021, in Hypertension, testosterone levels increased, on average, 3.0 nmol/L in both testosterone groups by week 12 (P = .003). In all, 62% of these men had levels of the hormone exceeding 14 nmol/L, compared with 29% of those receiving placebo.

Testosterone levels improved with exercise training plus placebo by 0.9 nmol/L, but fell with no exercise and placebo by 0.9 nmol/L.

In terms of vascular function, exercise training increased FMD when expressed as both the delta change (mm; P = .004) and relative rise from baseline diameter (%; P = .033).

There was no effect of exercise on GTN%, which is generally in line with exercise literature indicating that shear-mediated adaptations in response to episodic exercise occur largely in endothelial cells, the authors noted.

Testosterone did not affect any measures of FMD nor was there an effect on GTN response, despite previous evidence that lower testosterone doses might enhance smooth muscle function.

“Our main finding was that testosterone – at this dose over this duration of treatment – did not have a beneficial effect on artery health, nor did it enhance the effect of exercise,” said Dr. Yeap, who is also president of the Endocrine Society of Australia. “For middle-aged and older men wanting to improve the health of their arteries, exercise is better than testosterone!”

Shalender Bhasin, MBBS, director of research programs in men’s health, aging, and metabolism at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study is interesting from a mechanistic perspective and adds to the overall body of evidence on how testosterone affects performance, but was narrowly focused.

“They looked at very specific markers and what they’re showing is that this is not the mechanism by which testosterone improves performance,” he said. “That may be so, but it doesn’t negate the finding that testosterone improves endurance and has other vascular effects: it increases capillarity, increases blood flow to the tissues, and improves myocardial function.”

Although well done, the study doesn’t get at the larger question of whether testosterone increases cardiovascular risk, observed Dr. Bhasin. “None of the randomized studies have been large enough or long enough to determine the effect on cardiovascular events rates. There’s a lot of argument on both sides but we need some data to address that.”

The 6,000-patient TRAVERSE trial is specifically looking at long-term major cardiovascular events with topical testosterone, compared with placebo, in hypogonadal men aged 45-80 years age who have evidence of or are at increased risk for CVD. The study, which is set to be completed in April 2022, should also provide information on fracture risk in these men, said Dr. Bhasin, one of the trial’s principal investigators and lead author of the Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism in men.

William Evans, MD, adjunct professor of human nutrition, University of California, Berkley, said in an interview that the positive effects of testosterone occur at much lower doses in men and women who are hypogonadal but, in this particular population, exercise is the key and the major recommendation.

“Testosterone has been overprescribed and overadvertised for essentially a lifetime of sedentary living, and it’s advertised as a way to get all that back without having to work for it,” he said. “Exercise has a profound and positive effect on control of blood pressure, function, and strength, and testosterone may only affect in people who are sick, people who have really low levels.”

The study was funded by the Heart Foundation of Australia. Lawley Pharmaceuticals provided the study medication and placebo. Dr. Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Besins Healthcare; research support from Bayer, Lily, and Lawley; and served as an adviser for Lily, Besins Healthcare, Ferring, and Lawley. Dr. Shalender reports consultation or advisement for GTx, Pfizer, and TAP; grant or other research support from Solvay and GlaxoSmithKline; and honoraria from Solvay and Auxilium. Dr. Evans reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exercise training – but not testosterone therapy – improved vascular health in aging men with widening midsections and low to normal testosterone, new research suggests.

“Previous studies have suggested that men with higher levels of testosterone, who were more physically active, might have better health outcomes,” Bu Beng Yeap, MBBS, PhD, University of Western Australia, Perth, said in an interview. “We formulated the hypothesis that the combination of testosterone treatment and exercise training would improve the health of arteries more than either alone.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators randomly assigned 80 men, aged 50-70 years, to 12 weeks of 5% testosterone cream 2 mL applied daily or placebo plus a supervised exercise program that included machine-based resistance and aerobic (cycling) exercises two to three times a week or no additional exercise.

The men (mean age, 59 years) had low-normal testosterone (6-14 nmol/L), a waist circumference of at least 95 cm (37.4 inches), and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 1 diabetes, or other clinically significant illnesses. Current smokers and men on testosterone or medications that would alter testosterone levels were also excluded.

High-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery was used to assess flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) responses. FMD has been shown to be predictive of CVD risk, with a 1% increase in FMD associated with a 9%-13% decrease in future CVD events.

Based on participants’ daily dairies, testosterone adherence was 97.6%. Exercise adherence was 96.5% for twice-weekly attendance and 80.0% for thrice-weekly attendance, with no between-group differences.

As reported Feb. 22, 2021, in Hypertension, testosterone levels increased, on average, 3.0 nmol/L in both testosterone groups by week 12 (P = .003). In all, 62% of these men had levels of the hormone exceeding 14 nmol/L, compared with 29% of those receiving placebo.

Testosterone levels improved with exercise training plus placebo by 0.9 nmol/L, but fell with no exercise and placebo by 0.9 nmol/L.

In terms of vascular function, exercise training increased FMD when expressed as both the delta change (mm; P = .004) and relative rise from baseline diameter (%; P = .033).

There was no effect of exercise on GTN%, which is generally in line with exercise literature indicating that shear-mediated adaptations in response to episodic exercise occur largely in endothelial cells, the authors noted.

Testosterone did not affect any measures of FMD nor was there an effect on GTN response, despite previous evidence that lower testosterone doses might enhance smooth muscle function.

“Our main finding was that testosterone – at this dose over this duration of treatment – did not have a beneficial effect on artery health, nor did it enhance the effect of exercise,” said Dr. Yeap, who is also president of the Endocrine Society of Australia. “For middle-aged and older men wanting to improve the health of their arteries, exercise is better than testosterone!”

Shalender Bhasin, MBBS, director of research programs in men’s health, aging, and metabolism at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study is interesting from a mechanistic perspective and adds to the overall body of evidence on how testosterone affects performance, but was narrowly focused.

“They looked at very specific markers and what they’re showing is that this is not the mechanism by which testosterone improves performance,” he said. “That may be so, but it doesn’t negate the finding that testosterone improves endurance and has other vascular effects: it increases capillarity, increases blood flow to the tissues, and improves myocardial function.”

Although well done, the study doesn’t get at the larger question of whether testosterone increases cardiovascular risk, observed Dr. Bhasin. “None of the randomized studies have been large enough or long enough to determine the effect on cardiovascular events rates. There’s a lot of argument on both sides but we need some data to address that.”

The 6,000-patient TRAVERSE trial is specifically looking at long-term major cardiovascular events with topical testosterone, compared with placebo, in hypogonadal men aged 45-80 years age who have evidence of or are at increased risk for CVD. The study, which is set to be completed in April 2022, should also provide information on fracture risk in these men, said Dr. Bhasin, one of the trial’s principal investigators and lead author of the Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism in men.

William Evans, MD, adjunct professor of human nutrition, University of California, Berkley, said in an interview that the positive effects of testosterone occur at much lower doses in men and women who are hypogonadal but, in this particular population, exercise is the key and the major recommendation.

“Testosterone has been overprescribed and overadvertised for essentially a lifetime of sedentary living, and it’s advertised as a way to get all that back without having to work for it,” he said. “Exercise has a profound and positive effect on control of blood pressure, function, and strength, and testosterone may only affect in people who are sick, people who have really low levels.”

The study was funded by the Heart Foundation of Australia. Lawley Pharmaceuticals provided the study medication and placebo. Dr. Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Besins Healthcare; research support from Bayer, Lily, and Lawley; and served as an adviser for Lily, Besins Healthcare, Ferring, and Lawley. Dr. Shalender reports consultation or advisement for GTx, Pfizer, and TAP; grant or other research support from Solvay and GlaxoSmithKline; and honoraria from Solvay and Auxilium. Dr. Evans reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Exercise training – but not testosterone therapy – improved vascular health in aging men with widening midsections and low to normal testosterone, new research suggests.

“Previous studies have suggested that men with higher levels of testosterone, who were more physically active, might have better health outcomes,” Bu Beng Yeap, MBBS, PhD, University of Western Australia, Perth, said in an interview. “We formulated the hypothesis that the combination of testosterone treatment and exercise training would improve the health of arteries more than either alone.”

To test this hypothesis, the investigators randomly assigned 80 men, aged 50-70 years, to 12 weeks of 5% testosterone cream 2 mL applied daily or placebo plus a supervised exercise program that included machine-based resistance and aerobic (cycling) exercises two to three times a week or no additional exercise.

The men (mean age, 59 years) had low-normal testosterone (6-14 nmol/L), a waist circumference of at least 95 cm (37.4 inches), and no known cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 1 diabetes, or other clinically significant illnesses. Current smokers and men on testosterone or medications that would alter testosterone levels were also excluded.

High-resolution ultrasound of the brachial artery was used to assess flow-mediated dilation (FMD) and sublingual glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) responses. FMD has been shown to be predictive of CVD risk, with a 1% increase in FMD associated with a 9%-13% decrease in future CVD events.

Based on participants’ daily dairies, testosterone adherence was 97.6%. Exercise adherence was 96.5% for twice-weekly attendance and 80.0% for thrice-weekly attendance, with no between-group differences.

As reported Feb. 22, 2021, in Hypertension, testosterone levels increased, on average, 3.0 nmol/L in both testosterone groups by week 12 (P = .003). In all, 62% of these men had levels of the hormone exceeding 14 nmol/L, compared with 29% of those receiving placebo.

Testosterone levels improved with exercise training plus placebo by 0.9 nmol/L, but fell with no exercise and placebo by 0.9 nmol/L.

In terms of vascular function, exercise training increased FMD when expressed as both the delta change (mm; P = .004) and relative rise from baseline diameter (%; P = .033).

There was no effect of exercise on GTN%, which is generally in line with exercise literature indicating that shear-mediated adaptations in response to episodic exercise occur largely in endothelial cells, the authors noted.

Testosterone did not affect any measures of FMD nor was there an effect on GTN response, despite previous evidence that lower testosterone doses might enhance smooth muscle function.

“Our main finding was that testosterone – at this dose over this duration of treatment – did not have a beneficial effect on artery health, nor did it enhance the effect of exercise,” said Dr. Yeap, who is also president of the Endocrine Society of Australia. “For middle-aged and older men wanting to improve the health of their arteries, exercise is better than testosterone!”

Shalender Bhasin, MBBS, director of research programs in men’s health, aging, and metabolism at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, said the study is interesting from a mechanistic perspective and adds to the overall body of evidence on how testosterone affects performance, but was narrowly focused.

“They looked at very specific markers and what they’re showing is that this is not the mechanism by which testosterone improves performance,” he said. “That may be so, but it doesn’t negate the finding that testosterone improves endurance and has other vascular effects: it increases capillarity, increases blood flow to the tissues, and improves myocardial function.”

Although well done, the study doesn’t get at the larger question of whether testosterone increases cardiovascular risk, observed Dr. Bhasin. “None of the randomized studies have been large enough or long enough to determine the effect on cardiovascular events rates. There’s a lot of argument on both sides but we need some data to address that.”

The 6,000-patient TRAVERSE trial is specifically looking at long-term major cardiovascular events with topical testosterone, compared with placebo, in hypogonadal men aged 45-80 years age who have evidence of or are at increased risk for CVD. The study, which is set to be completed in April 2022, should also provide information on fracture risk in these men, said Dr. Bhasin, one of the trial’s principal investigators and lead author of the Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline on testosterone therapy for hypogonadism in men.

William Evans, MD, adjunct professor of human nutrition, University of California, Berkley, said in an interview that the positive effects of testosterone occur at much lower doses in men and women who are hypogonadal but, in this particular population, exercise is the key and the major recommendation.

“Testosterone has been overprescribed and overadvertised for essentially a lifetime of sedentary living, and it’s advertised as a way to get all that back without having to work for it,” he said. “Exercise has a profound and positive effect on control of blood pressure, function, and strength, and testosterone may only affect in people who are sick, people who have really low levels.”

The study was funded by the Heart Foundation of Australia. Lawley Pharmaceuticals provided the study medication and placebo. Dr. Yeap has received speaker honoraria and conference support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Besins Healthcare; research support from Bayer, Lily, and Lawley; and served as an adviser for Lily, Besins Healthcare, Ferring, and Lawley. Dr. Shalender reports consultation or advisement for GTx, Pfizer, and TAP; grant or other research support from Solvay and GlaxoSmithKline; and honoraria from Solvay and Auxilium. Dr. Evans reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Big data ‘clinch’ link between high glycemic index diets and CVD

People who mostly ate foods with a low glycemic index had a lower likelihood of premature death and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, compared with those whose diet included more “poor-quality” food with a high glycemic index.

The results from the global PURE study of nearly 120,000 people provide evidence that helps cement glycemic index as a key measure of dietary health.

This new analysis from PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study) – a massive prospective epidemiologic study – shows people with a diet in the highest quintile of glycemic index had a significant 25% higher rate of combined total deaths and major CVD events during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, compared with those with a diet in the lowest glycemic index quintile, in the report published online on Feb. 24, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, lead author, said people do not necessarily need to closely track the glycemic index of what they eat to follow the guidance that lower is better.

The link between lower glycemic load and fewer CVD events was even stronger among people with an established history of CVD at study entry. In this subset, which included 9% of the total cohort, people in the highest quintile for glycemic index consumption had a 51% higher rate of the composite primary endpoint, compared with those in the lowest quintile, in an analysis that adjusted for several potential confounders.

A simple but accurate and effective public health message is to follow existing dietary recommendations to eat better-quality food – more unprocessed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – Dr. Jenkins advised. Those who prefer a more detailed approach could use the comprehensive glycemic index tables compiled by researchers at the University of Sydney.

‘All carbohydrates are not the same’

“What we’re saying is that all carbohydrates are not the same. Some seem to increase the risk for CVD, and others seem protective. This is not new, but worth restating in an era of low-carb and no-carb diets,” said Dr. Jenkins.

Low-glycemic-index foods are generally unprocessed foods in their native state, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unrefined whole grains. High-glycemic-index foods contain processed and refined carbohydrates that deliver jolts of glucose soon after eating, as the sugar in these carbohydrates quickly moves from the gut to the bloodstream.

An association between a diet with a lower glycemic index and better outcomes had appeared in prior reports from other studies, but not as unambiguously as in the new data from PURE, likely because of fewer study participants in previous studies.

Another feature of PURE that adds to the generalizability of the findings is the diversity of adults included in the study, from 20 countries on five continents.

“This clinches it,” Dr. Jenkins declared in an interview.

New PURE data tip the evidence balance

The NEJM article includes a new meta-analysis that adds the PURE findings to data from two large prior reports that were each less conclusive. The new calculation with the PURE numbers helps establish a clearer association between a diet with a higher glycemic index and the endpoint of CVD death, showing an overall 26% increase in the outcome.

The PURE data are especially informative because the investigators collected additional information on a range of potential confounders they incorporated into their analyses.

“We were able to include a lot of documentation on many potential confounders. That’s a strength of our data,” noted Dr. Jenkins, a professor of nutritional science and medicine at the University of Toronto.

“The present data, along with prior publications from PURE and several other studies, emphasize that consumption of poor quality carbohydrates is likely to be more adverse than the consumption of most fats in the diet,” said senior author Salim Yusuf, MD, DPhil, professor of medicine and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

“This calls for a fundamental shift in our thinking of what types of diet are likely to be harmful and what types neutral or beneficial,” Dr. Yusuf said in a statement from his institution.

Higher BMI associated with greater glycemic index effect

Another important analysis in the new report calculated the impact of a higher glycemic index diet among people with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 as well as higher BMIs.

Among people in the lower BMI subgroup, greater intake of high-glycemic-index foods showed slightly more incident primary outcome events. In contrast, people with a BMI of 25 or greater showed a steady increment in primary outcome events as the glycemic index of their diet increased.

People with higher BMIs in the quartile that ate the greatest amount of high-glycemic =-index foods had a significant 38% higher rate of primary outcome events, compared with people with similar BMIs in the lowest quartile for high-glycemic-index intake.

However, the study showed no impact on the primary association of high glycemic index and increased adverse outcomes by exercise habits, smoking, use of blood pressure medications, or use of statins.

The new report complements a separate analysis from PURE published just a few weeks earlier in the BMJ that established a significant association between increased consumption of whole grains and fewer CVD events, compared with people who had more refined grains in their diet, as reported by this news organization.

This prior report on whole versus refined grains, which Dr. Jenkins coauthored, looked at carbohydrate quality using a two-pronged approach, while glycemic index is a continuous variable that provides more nuance and takes into account carbohydrates from sources other than grains, Dr. Jenkins said.

PURE enrolled roughly 225,000 people aged 35-70 years at entry. The glycemic index analysis focused on 119,575 people who had data available for the primary outcome. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, these people had 14,075 primary outcome events, including 8,780 deaths.

Analyses that looked at the individual outcomes that comprised the composite endpoint showed significant associations between a high-glycemic-index diet and total mortality, CVD death, non-CVD death, and stroke, but showed no significant link with myocardial infarction or heart failure. These findings are consistent with prior results of other studies that showed a stronger link between stroke and a high glycemic index diet, compared with other nonfatal CVD events.

Dr. Jenkins suggested that the significant excess of non-CVD deaths linked with a high-glycemic-index diet may stem from the impact of this type of diet on cancer-associated mortality.

PURE received partial funding through unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Jenkins has reported receiving gifts from several food-related trade associations and food companies, as well as research grants from two legume-oriented trade associations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who mostly ate foods with a low glycemic index had a lower likelihood of premature death and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, compared with those whose diet included more “poor-quality” food with a high glycemic index.

The results from the global PURE study of nearly 120,000 people provide evidence that helps cement glycemic index as a key measure of dietary health.

This new analysis from PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study) – a massive prospective epidemiologic study – shows people with a diet in the highest quintile of glycemic index had a significant 25% higher rate of combined total deaths and major CVD events during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, compared with those with a diet in the lowest glycemic index quintile, in the report published online on Feb. 24, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, lead author, said people do not necessarily need to closely track the glycemic index of what they eat to follow the guidance that lower is better.

The link between lower glycemic load and fewer CVD events was even stronger among people with an established history of CVD at study entry. In this subset, which included 9% of the total cohort, people in the highest quintile for glycemic index consumption had a 51% higher rate of the composite primary endpoint, compared with those in the lowest quintile, in an analysis that adjusted for several potential confounders.

A simple but accurate and effective public health message is to follow existing dietary recommendations to eat better-quality food – more unprocessed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – Dr. Jenkins advised. Those who prefer a more detailed approach could use the comprehensive glycemic index tables compiled by researchers at the University of Sydney.

‘All carbohydrates are not the same’

“What we’re saying is that all carbohydrates are not the same. Some seem to increase the risk for CVD, and others seem protective. This is not new, but worth restating in an era of low-carb and no-carb diets,” said Dr. Jenkins.

Low-glycemic-index foods are generally unprocessed foods in their native state, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unrefined whole grains. High-glycemic-index foods contain processed and refined carbohydrates that deliver jolts of glucose soon after eating, as the sugar in these carbohydrates quickly moves from the gut to the bloodstream.

An association between a diet with a lower glycemic index and better outcomes had appeared in prior reports from other studies, but not as unambiguously as in the new data from PURE, likely because of fewer study participants in previous studies.

Another feature of PURE that adds to the generalizability of the findings is the diversity of adults included in the study, from 20 countries on five continents.

“This clinches it,” Dr. Jenkins declared in an interview.

New PURE data tip the evidence balance

The NEJM article includes a new meta-analysis that adds the PURE findings to data from two large prior reports that were each less conclusive. The new calculation with the PURE numbers helps establish a clearer association between a diet with a higher glycemic index and the endpoint of CVD death, showing an overall 26% increase in the outcome.

The PURE data are especially informative because the investigators collected additional information on a range of potential confounders they incorporated into their analyses.

“We were able to include a lot of documentation on many potential confounders. That’s a strength of our data,” noted Dr. Jenkins, a professor of nutritional science and medicine at the University of Toronto.

“The present data, along with prior publications from PURE and several other studies, emphasize that consumption of poor quality carbohydrates is likely to be more adverse than the consumption of most fats in the diet,” said senior author Salim Yusuf, MD, DPhil, professor of medicine and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

“This calls for a fundamental shift in our thinking of what types of diet are likely to be harmful and what types neutral or beneficial,” Dr. Yusuf said in a statement from his institution.

Higher BMI associated with greater glycemic index effect

Another important analysis in the new report calculated the impact of a higher glycemic index diet among people with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 as well as higher BMIs.

Among people in the lower BMI subgroup, greater intake of high-glycemic-index foods showed slightly more incident primary outcome events. In contrast, people with a BMI of 25 or greater showed a steady increment in primary outcome events as the glycemic index of their diet increased.

People with higher BMIs in the quartile that ate the greatest amount of high-glycemic =-index foods had a significant 38% higher rate of primary outcome events, compared with people with similar BMIs in the lowest quartile for high-glycemic-index intake.

However, the study showed no impact on the primary association of high glycemic index and increased adverse outcomes by exercise habits, smoking, use of blood pressure medications, or use of statins.

The new report complements a separate analysis from PURE published just a few weeks earlier in the BMJ that established a significant association between increased consumption of whole grains and fewer CVD events, compared with people who had more refined grains in their diet, as reported by this news organization.

This prior report on whole versus refined grains, which Dr. Jenkins coauthored, looked at carbohydrate quality using a two-pronged approach, while glycemic index is a continuous variable that provides more nuance and takes into account carbohydrates from sources other than grains, Dr. Jenkins said.

PURE enrolled roughly 225,000 people aged 35-70 years at entry. The glycemic index analysis focused on 119,575 people who had data available for the primary outcome. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, these people had 14,075 primary outcome events, including 8,780 deaths.

Analyses that looked at the individual outcomes that comprised the composite endpoint showed significant associations between a high-glycemic-index diet and total mortality, CVD death, non-CVD death, and stroke, but showed no significant link with myocardial infarction or heart failure. These findings are consistent with prior results of other studies that showed a stronger link between stroke and a high glycemic index diet, compared with other nonfatal CVD events.

Dr. Jenkins suggested that the significant excess of non-CVD deaths linked with a high-glycemic-index diet may stem from the impact of this type of diet on cancer-associated mortality.

PURE received partial funding through unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Jenkins has reported receiving gifts from several food-related trade associations and food companies, as well as research grants from two legume-oriented trade associations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People who mostly ate foods with a low glycemic index had a lower likelihood of premature death and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) events, compared with those whose diet included more “poor-quality” food with a high glycemic index.

The results from the global PURE study of nearly 120,000 people provide evidence that helps cement glycemic index as a key measure of dietary health.

This new analysis from PURE (Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study) – a massive prospective epidemiologic study – shows people with a diet in the highest quintile of glycemic index had a significant 25% higher rate of combined total deaths and major CVD events during a median follow-up of nearly 10 years, compared with those with a diet in the lowest glycemic index quintile, in the report published online on Feb. 24, 2021, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

David J.A. Jenkins, MD, PhD, DSc, lead author, said people do not necessarily need to closely track the glycemic index of what they eat to follow the guidance that lower is better.

The link between lower glycemic load and fewer CVD events was even stronger among people with an established history of CVD at study entry. In this subset, which included 9% of the total cohort, people in the highest quintile for glycemic index consumption had a 51% higher rate of the composite primary endpoint, compared with those in the lowest quintile, in an analysis that adjusted for several potential confounders.

A simple but accurate and effective public health message is to follow existing dietary recommendations to eat better-quality food – more unprocessed fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains – Dr. Jenkins advised. Those who prefer a more detailed approach could use the comprehensive glycemic index tables compiled by researchers at the University of Sydney.

‘All carbohydrates are not the same’

“What we’re saying is that all carbohydrates are not the same. Some seem to increase the risk for CVD, and others seem protective. This is not new, but worth restating in an era of low-carb and no-carb diets,” said Dr. Jenkins.

Low-glycemic-index foods are generally unprocessed foods in their native state, including fruits, vegetables, legumes, and unrefined whole grains. High-glycemic-index foods contain processed and refined carbohydrates that deliver jolts of glucose soon after eating, as the sugar in these carbohydrates quickly moves from the gut to the bloodstream.

An association between a diet with a lower glycemic index and better outcomes had appeared in prior reports from other studies, but not as unambiguously as in the new data from PURE, likely because of fewer study participants in previous studies.

Another feature of PURE that adds to the generalizability of the findings is the diversity of adults included in the study, from 20 countries on five continents.

“This clinches it,” Dr. Jenkins declared in an interview.

New PURE data tip the evidence balance

The NEJM article includes a new meta-analysis that adds the PURE findings to data from two large prior reports that were each less conclusive. The new calculation with the PURE numbers helps establish a clearer association between a diet with a higher glycemic index and the endpoint of CVD death, showing an overall 26% increase in the outcome.

The PURE data are especially informative because the investigators collected additional information on a range of potential confounders they incorporated into their analyses.

“We were able to include a lot of documentation on many potential confounders. That’s a strength of our data,” noted Dr. Jenkins, a professor of nutritional science and medicine at the University of Toronto.

“The present data, along with prior publications from PURE and several other studies, emphasize that consumption of poor quality carbohydrates is likely to be more adverse than the consumption of most fats in the diet,” said senior author Salim Yusuf, MD, DPhil, professor of medicine and executive director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.

“This calls for a fundamental shift in our thinking of what types of diet are likely to be harmful and what types neutral or beneficial,” Dr. Yusuf said in a statement from his institution.

Higher BMI associated with greater glycemic index effect

Another important analysis in the new report calculated the impact of a higher glycemic index diet among people with a body mass index (BMI) of less than 25 kg/m2 as well as higher BMIs.

Among people in the lower BMI subgroup, greater intake of high-glycemic-index foods showed slightly more incident primary outcome events. In contrast, people with a BMI of 25 or greater showed a steady increment in primary outcome events as the glycemic index of their diet increased.

People with higher BMIs in the quartile that ate the greatest amount of high-glycemic =-index foods had a significant 38% higher rate of primary outcome events, compared with people with similar BMIs in the lowest quartile for high-glycemic-index intake.

However, the study showed no impact on the primary association of high glycemic index and increased adverse outcomes by exercise habits, smoking, use of blood pressure medications, or use of statins.

The new report complements a separate analysis from PURE published just a few weeks earlier in the BMJ that established a significant association between increased consumption of whole grains and fewer CVD events, compared with people who had more refined grains in their diet, as reported by this news organization.

This prior report on whole versus refined grains, which Dr. Jenkins coauthored, looked at carbohydrate quality using a two-pronged approach, while glycemic index is a continuous variable that provides more nuance and takes into account carbohydrates from sources other than grains, Dr. Jenkins said.

PURE enrolled roughly 225,000 people aged 35-70 years at entry. The glycemic index analysis focused on 119,575 people who had data available for the primary outcome. During a median follow-up of 9.5 years, these people had 14,075 primary outcome events, including 8,780 deaths.

Analyses that looked at the individual outcomes that comprised the composite endpoint showed significant associations between a high-glycemic-index diet and total mortality, CVD death, non-CVD death, and stroke, but showed no significant link with myocardial infarction or heart failure. These findings are consistent with prior results of other studies that showed a stronger link between stroke and a high glycemic index diet, compared with other nonfatal CVD events.

Dr. Jenkins suggested that the significant excess of non-CVD deaths linked with a high-glycemic-index diet may stem from the impact of this type of diet on cancer-associated mortality.

PURE received partial funding through unrestricted grants from several drug companies. Dr. Jenkins has reported receiving gifts from several food-related trade associations and food companies, as well as research grants from two legume-oriented trade associations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Thirteen percent of patients with type 2 diabetes have major ECG abnormalities

Major ECG abnormalities were found in 13% of more than 8,000 unselected patients with type 2 diabetes, including a 9% prevalence in the subgroup of these patients without identified cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a community-based Dutch cohort. Minor ECG abnormalities were even more prevalent.

These prevalence rates were consistent with prior findings from patients with type 2 diabetes, but the current report is notable because “it provides the most thorough description of the prevalence of ECG abnormalities in people with type 2 diabetes,” and used an “unselected and large population with comprehensive measurements,” including many without a history of CVD, said Peter P. Harms, MSc, and associates noted in a recent report in the Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications.

The analysis also identified several parameters that significantly linked with the presence of a major ECG abnormality including hypertension, male sex, older age, and higher levels of hemoglobin A1c.

“Resting ECG abnormalities might be a useful tool for CVD screening in people with type 2 diabetes,” concluded Mr. Harms, a researcher at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, and coauthors.

Findings “not unexpected”

Patients with diabetes have a higher prevalence of ECG abnormalities “because of their higher likelihood of having hypertension and other CVD risk factors,” as well as potentially having subclinical CVD, said Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, so these findings are “not unexpected. The more risk factors a patient has for structural heart disease, atrial fibrillation (AFib), or stroke from AFib, the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

But he cautioned against seeing these findings as a rationale to routinely run a resting ECG examination on every adult with diabetes.

“Patients with diabetes are very heterogeneous,” which makes it “difficult to come up with a ‘one size fits all’ recommendation” for ECG screening of patients with diabetes, he said.

While a task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes set a class I level C guideline for resting ECG screening of patients with diabetes if they also have either hypertension or suspected CVD, the American Diabetes Association has no specific recommendations on which patients with diabetes should receive ECG screening.

“The current absence of U.S. recommendations is reasonable, as it allows patients and physicians to discuss the issues and decide on the utility of an ECG in their specific situation,” said Dr. Kusumoto, director of heart rhythm services at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. But he also suggested that “the more risk factors that a patient with diabetes has for structural heart disease, AFib, or stroke from AFib the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate.”

Data from a Dutch prospective cohort

The new study used data collected from 8,068 patients with type 2 diabetes and enrolled in the prospective Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort, which enrolled patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in the West Friesland region of the Netherlands starting in 1996. The study includes most of these patients in the region who are under regular care of a general practitioner, and the study protocol calls for an annual resting ECG examination.

The investigators used standard, 12-lead ECG readings taken for each patient during 2018, and classified abnormalities by the Minnesota Code criteria. They divided the abnormalities into major or minor groups “in accordance with consensus between previous studies who categorised abnormalities according to perceived importance and/or severity.” The major subgroup included major QS pattern abnormalities, major ST-segment abnormalities, complete left bundle branch block or intraventricular block, or atrial fibrillation or flutter. Minor abnormalities included minor QS pattern abnormalities, minor ST-segment abnormalities, complete right bundle branch block, or premature atrial or ventricular contractions.

The prevalence of a major abnormality in the entire cohort examined was 13%, and another 16% had a minor abnormality. The most common types of abnormalities were ventricular conduction defects, in 14%; and arrhythmias, in 11%. In the subgroup of 6,494 of these patients with no history of CVD, 9% had a major abnormality and 15% a minor abnormality. Within this subgroup, 23% also had no hypertension, and their prevalence of a major abnormality was 4%, while 9% had a minor abnormality.

A multivariable analysis of potential risk factors among the entire study cohort showed that patients with hypertension had nearly triple the prevalence of a major ECG abnormality as those without hypertension, and men had double the prevalence of a major abnormality compared with women. Other markers that significantly linked with a higher rate of a major abnormality were older age, higher body mass index, higher A1c levels, and moderately depressed renal function.

“While the criteria the authors used for differentiating major and minor criteria are reasonable, in an asymptomatic patient even the presence of frequent premature atrial contractions on a baseline ECG has been associated with the development of AFib and a higher risk for stroke. The presence of left or right bundle branch block could spur additional evaluation with an echocardiogram,” said Dr. Kusumoto, president-elect of the Heart Rhythm Society.

“Generally an ECG abnormality is supplemental to clinical data in deciding the choice and timing of next therapeutic steps or additional testing. Physicians should have a fairly low threshold for obtaining ECG in patients with diabetes since it is inexpensive and can provide supplemental and potentially actionable information,” he said. “The presence of ECG abnormalities increases the possibility of underlying cardiovascular disease. When taking care of patients with diabetes at initial evaluation or without prior cardiac history or symptoms referable to the heart, two main issues are identifying the likelihood of coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation.”

Mr. Harms and coauthors, and Dr. Kusumoto, had no disclosures.

Major ECG abnormalities were found in 13% of more than 8,000 unselected patients with type 2 diabetes, including a 9% prevalence in the subgroup of these patients without identified cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a community-based Dutch cohort. Minor ECG abnormalities were even more prevalent.

These prevalence rates were consistent with prior findings from patients with type 2 diabetes, but the current report is notable because “it provides the most thorough description of the prevalence of ECG abnormalities in people with type 2 diabetes,” and used an “unselected and large population with comprehensive measurements,” including many without a history of CVD, said Peter P. Harms, MSc, and associates noted in a recent report in the Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications.

The analysis also identified several parameters that significantly linked with the presence of a major ECG abnormality including hypertension, male sex, older age, and higher levels of hemoglobin A1c.

“Resting ECG abnormalities might be a useful tool for CVD screening in people with type 2 diabetes,” concluded Mr. Harms, a researcher at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, and coauthors.

Findings “not unexpected”

Patients with diabetes have a higher prevalence of ECG abnormalities “because of their higher likelihood of having hypertension and other CVD risk factors,” as well as potentially having subclinical CVD, said Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, so these findings are “not unexpected. The more risk factors a patient has for structural heart disease, atrial fibrillation (AFib), or stroke from AFib, the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

But he cautioned against seeing these findings as a rationale to routinely run a resting ECG examination on every adult with diabetes.

“Patients with diabetes are very heterogeneous,” which makes it “difficult to come up with a ‘one size fits all’ recommendation” for ECG screening of patients with diabetes, he said.

While a task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes set a class I level C guideline for resting ECG screening of patients with diabetes if they also have either hypertension or suspected CVD, the American Diabetes Association has no specific recommendations on which patients with diabetes should receive ECG screening.

“The current absence of U.S. recommendations is reasonable, as it allows patients and physicians to discuss the issues and decide on the utility of an ECG in their specific situation,” said Dr. Kusumoto, director of heart rhythm services at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. But he also suggested that “the more risk factors that a patient with diabetes has for structural heart disease, AFib, or stroke from AFib the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate.”

Data from a Dutch prospective cohort

The new study used data collected from 8,068 patients with type 2 diabetes and enrolled in the prospective Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort, which enrolled patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in the West Friesland region of the Netherlands starting in 1996. The study includes most of these patients in the region who are under regular care of a general practitioner, and the study protocol calls for an annual resting ECG examination.

The investigators used standard, 12-lead ECG readings taken for each patient during 2018, and classified abnormalities by the Minnesota Code criteria. They divided the abnormalities into major or minor groups “in accordance with consensus between previous studies who categorised abnormalities according to perceived importance and/or severity.” The major subgroup included major QS pattern abnormalities, major ST-segment abnormalities, complete left bundle branch block or intraventricular block, or atrial fibrillation or flutter. Minor abnormalities included minor QS pattern abnormalities, minor ST-segment abnormalities, complete right bundle branch block, or premature atrial or ventricular contractions.

The prevalence of a major abnormality in the entire cohort examined was 13%, and another 16% had a minor abnormality. The most common types of abnormalities were ventricular conduction defects, in 14%; and arrhythmias, in 11%. In the subgroup of 6,494 of these patients with no history of CVD, 9% had a major abnormality and 15% a minor abnormality. Within this subgroup, 23% also had no hypertension, and their prevalence of a major abnormality was 4%, while 9% had a minor abnormality.

A multivariable analysis of potential risk factors among the entire study cohort showed that patients with hypertension had nearly triple the prevalence of a major ECG abnormality as those without hypertension, and men had double the prevalence of a major abnormality compared with women. Other markers that significantly linked with a higher rate of a major abnormality were older age, higher body mass index, higher A1c levels, and moderately depressed renal function.

“While the criteria the authors used for differentiating major and minor criteria are reasonable, in an asymptomatic patient even the presence of frequent premature atrial contractions on a baseline ECG has been associated with the development of AFib and a higher risk for stroke. The presence of left or right bundle branch block could spur additional evaluation with an echocardiogram,” said Dr. Kusumoto, president-elect of the Heart Rhythm Society.

“Generally an ECG abnormality is supplemental to clinical data in deciding the choice and timing of next therapeutic steps or additional testing. Physicians should have a fairly low threshold for obtaining ECG in patients with diabetes since it is inexpensive and can provide supplemental and potentially actionable information,” he said. “The presence of ECG abnormalities increases the possibility of underlying cardiovascular disease. When taking care of patients with diabetes at initial evaluation or without prior cardiac history or symptoms referable to the heart, two main issues are identifying the likelihood of coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation.”

Mr. Harms and coauthors, and Dr. Kusumoto, had no disclosures.

Major ECG abnormalities were found in 13% of more than 8,000 unselected patients with type 2 diabetes, including a 9% prevalence in the subgroup of these patients without identified cardiovascular disease (CVD) in a community-based Dutch cohort. Minor ECG abnormalities were even more prevalent.

These prevalence rates were consistent with prior findings from patients with type 2 diabetes, but the current report is notable because “it provides the most thorough description of the prevalence of ECG abnormalities in people with type 2 diabetes,” and used an “unselected and large population with comprehensive measurements,” including many without a history of CVD, said Peter P. Harms, MSc, and associates noted in a recent report in the Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications.

The analysis also identified several parameters that significantly linked with the presence of a major ECG abnormality including hypertension, male sex, older age, and higher levels of hemoglobin A1c.

“Resting ECG abnormalities might be a useful tool for CVD screening in people with type 2 diabetes,” concluded Mr. Harms, a researcher at the Amsterdam University Medical Center, and coauthors.

Findings “not unexpected”

Patients with diabetes have a higher prevalence of ECG abnormalities “because of their higher likelihood of having hypertension and other CVD risk factors,” as well as potentially having subclinical CVD, said Fred M. Kusumoto, MD, so these findings are “not unexpected. The more risk factors a patient has for structural heart disease, atrial fibrillation (AFib), or stroke from AFib, the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate,” Dr. Kusumoto said in an interview.

But he cautioned against seeing these findings as a rationale to routinely run a resting ECG examination on every adult with diabetes.

“Patients with diabetes are very heterogeneous,” which makes it “difficult to come up with a ‘one size fits all’ recommendation” for ECG screening of patients with diabetes, he said.

While a task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes set a class I level C guideline for resting ECG screening of patients with diabetes if they also have either hypertension or suspected CVD, the American Diabetes Association has no specific recommendations on which patients with diabetes should receive ECG screening.

“The current absence of U.S. recommendations is reasonable, as it allows patients and physicians to discuss the issues and decide on the utility of an ECG in their specific situation,” said Dr. Kusumoto, director of heart rhythm services at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. But he also suggested that “the more risk factors that a patient with diabetes has for structural heart disease, AFib, or stroke from AFib the more a physician must consider whether a baseline ECG and future surveillance is appropriate.”

Data from a Dutch prospective cohort

The new study used data collected from 8,068 patients with type 2 diabetes and enrolled in the prospective Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort, which enrolled patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in the West Friesland region of the Netherlands starting in 1996. The study includes most of these patients in the region who are under regular care of a general practitioner, and the study protocol calls for an annual resting ECG examination.

The investigators used standard, 12-lead ECG readings taken for each patient during 2018, and classified abnormalities by the Minnesota Code criteria. They divided the abnormalities into major or minor groups “in accordance with consensus between previous studies who categorised abnormalities according to perceived importance and/or severity.” The major subgroup included major QS pattern abnormalities, major ST-segment abnormalities, complete left bundle branch block or intraventricular block, or atrial fibrillation or flutter. Minor abnormalities included minor QS pattern abnormalities, minor ST-segment abnormalities, complete right bundle branch block, or premature atrial or ventricular contractions.

The prevalence of a major abnormality in the entire cohort examined was 13%, and another 16% had a minor abnormality. The most common types of abnormalities were ventricular conduction defects, in 14%; and arrhythmias, in 11%. In the subgroup of 6,494 of these patients with no history of CVD, 9% had a major abnormality and 15% a minor abnormality. Within this subgroup, 23% also had no hypertension, and their prevalence of a major abnormality was 4%, while 9% had a minor abnormality.

A multivariable analysis of potential risk factors among the entire study cohort showed that patients with hypertension had nearly triple the prevalence of a major ECG abnormality as those without hypertension, and men had double the prevalence of a major abnormality compared with women. Other markers that significantly linked with a higher rate of a major abnormality were older age, higher body mass index, higher A1c levels, and moderately depressed renal function.

“While the criteria the authors used for differentiating major and minor criteria are reasonable, in an asymptomatic patient even the presence of frequent premature atrial contractions on a baseline ECG has been associated with the development of AFib and a higher risk for stroke. The presence of left or right bundle branch block could spur additional evaluation with an echocardiogram,” said Dr. Kusumoto, president-elect of the Heart Rhythm Society.

“Generally an ECG abnormality is supplemental to clinical data in deciding the choice and timing of next therapeutic steps or additional testing. Physicians should have a fairly low threshold for obtaining ECG in patients with diabetes since it is inexpensive and can provide supplemental and potentially actionable information,” he said. “The presence of ECG abnormalities increases the possibility of underlying cardiovascular disease. When taking care of patients with diabetes at initial evaluation or without prior cardiac history or symptoms referable to the heart, two main issues are identifying the likelihood of coronary artery disease and atrial fibrillation.”

Mr. Harms and coauthors, and Dr. Kusumoto, had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF DIABETES AND ITS COMPLICATIONS

New-onset arrhythmias low in COVID-19 and flu

Among 3,970 patients treated during the early months of the pandemic, new onset AF/AFL was seen in 4%, matching the 4% incidence found in a historic cohort of patients hospitalized with influenza.

On the other hand, mortality was similarly high in both groups of patients studied with AF/AFL, showing a 77% increased risk of death in COVID-19 and a 78% increased risk in influenza, a team from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York reported.

“We saw new onset Afib and flutter in a minority of patients and it was associated with much higher mortality, but the point is that this increase is basically the same as what you see in influenza, which we feel is an indication that this is more of a generalized response to the inflammatory milieu of such a severe viral illness, as opposed to something specific to COVID,” Vivek Y. Reddy, MD, said in the report, published online Feb. 25 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

“Here we see, with a similar respiratory virus used as controls, that the results are exactly what I would have expected to see, which is that where there is a lot of inflammation, we see Afib,” said John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., who was not involved with the study.

“We need more studies like this one because we know SARS-CoV-2 is a bad virus that may have important effects on the heart, but all the of research done so far has been problematic because it didn’t include controls.”

Atrial arrhythmias in COVID and flu

Dr. Reddy and coinvestigators performed a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients admitted with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during Feb. 4-April 22, 2020, to one of five hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System.

Their comparator arm included 1,420 patients with confirmed influenza A or B hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2017, and Jan. 1, 2020. For both cohorts, automated electronic record abstraction was used and all patient data were de-identified prior to analysis. In the COVID-19 cohort, a manual review of 1,110 charts was also performed.

Compared with those who did not develop AF/AFL, COVID-19 patients with newly detected AF/AFL and COVID-19 were older (74 vs. 66 years; P < .01) and had higher levels of inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and higher troponin and D-dimer levels (all P < .01).

Overall, including those with a history of atrial arrhythmias, 10% of patients with hospitalized COVID-19 (13% in the manual review) and 12% of those with influenza had AF/AFL detected during their hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days was higher in COVID-19 patients with AF/AFL compared to those without (46% vs. 26%; P < .01), as were the rates of intubation (27% vs. 15%; relative risk, 1.8; P < .01), and stroke (1.6% vs. 0.6%, RR, 2.7; P = .05).

Despite having more comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the influenza cohort overall, compared to the COVID-19 cohort (9% vs. 29%; P < .01), reflecting the higher case fatality rate in COVID-19, Dr. Reddy, director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Mount Sinai Hospital, said in an interview.

But as with COVID-19, those influenza patients who had in-hospital AF/AFL were more likely to require intubation (14% vs. 7%; P = .004) or die (16% vs. 10%; P = .003).

“The data are not perfect and there are always limitations when doing an observational study using historic controls, but my guess would be that if we looked at other databases and other populations hospitalized for severe illness, we’d likely see something similar because when the body is inflamed, you’re more likely to see Afib,” said Dr. Mandrola.

Dr. Reddy concurred, noting that they considered comparing other populations to COVID-19 patients, including those with “just generalized severe illness,” but in the end felt there were many similarities between influenza and COVID-19, even though mortality in the latter is higher.

“It would be interesting for people to look at other illnesses and see if they find the same thing,” he said.

Dr. Reddy reported having no disclosures relevant to COVID-19. Dr. Mandrola is chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.com. He reported having no relevant disclosures. MDedge is a member of the Medscape Professional Network.

Among 3,970 patients treated during the early months of the pandemic, new onset AF/AFL was seen in 4%, matching the 4% incidence found in a historic cohort of patients hospitalized with influenza.

On the other hand, mortality was similarly high in both groups of patients studied with AF/AFL, showing a 77% increased risk of death in COVID-19 and a 78% increased risk in influenza, a team from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York reported.

“We saw new onset Afib and flutter in a minority of patients and it was associated with much higher mortality, but the point is that this increase is basically the same as what you see in influenza, which we feel is an indication that this is more of a generalized response to the inflammatory milieu of such a severe viral illness, as opposed to something specific to COVID,” Vivek Y. Reddy, MD, said in the report, published online Feb. 25 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

“Here we see, with a similar respiratory virus used as controls, that the results are exactly what I would have expected to see, which is that where there is a lot of inflammation, we see Afib,” said John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., who was not involved with the study.

“We need more studies like this one because we know SARS-CoV-2 is a bad virus that may have important effects on the heart, but all the of research done so far has been problematic because it didn’t include controls.”

Atrial arrhythmias in COVID and flu

Dr. Reddy and coinvestigators performed a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients admitted with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during Feb. 4-April 22, 2020, to one of five hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System.

Their comparator arm included 1,420 patients with confirmed influenza A or B hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2017, and Jan. 1, 2020. For both cohorts, automated electronic record abstraction was used and all patient data were de-identified prior to analysis. In the COVID-19 cohort, a manual review of 1,110 charts was also performed.

Compared with those who did not develop AF/AFL, COVID-19 patients with newly detected AF/AFL and COVID-19 were older (74 vs. 66 years; P < .01) and had higher levels of inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and higher troponin and D-dimer levels (all P < .01).

Overall, including those with a history of atrial arrhythmias, 10% of patients with hospitalized COVID-19 (13% in the manual review) and 12% of those with influenza had AF/AFL detected during their hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days was higher in COVID-19 patients with AF/AFL compared to those without (46% vs. 26%; P < .01), as were the rates of intubation (27% vs. 15%; relative risk, 1.8; P < .01), and stroke (1.6% vs. 0.6%, RR, 2.7; P = .05).

Despite having more comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the influenza cohort overall, compared to the COVID-19 cohort (9% vs. 29%; P < .01), reflecting the higher case fatality rate in COVID-19, Dr. Reddy, director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Mount Sinai Hospital, said in an interview.

But as with COVID-19, those influenza patients who had in-hospital AF/AFL were more likely to require intubation (14% vs. 7%; P = .004) or die (16% vs. 10%; P = .003).

“The data are not perfect and there are always limitations when doing an observational study using historic controls, but my guess would be that if we looked at other databases and other populations hospitalized for severe illness, we’d likely see something similar because when the body is inflamed, you’re more likely to see Afib,” said Dr. Mandrola.

Dr. Reddy concurred, noting that they considered comparing other populations to COVID-19 patients, including those with “just generalized severe illness,” but in the end felt there were many similarities between influenza and COVID-19, even though mortality in the latter is higher.

“It would be interesting for people to look at other illnesses and see if they find the same thing,” he said.

Dr. Reddy reported having no disclosures relevant to COVID-19. Dr. Mandrola is chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.com. He reported having no relevant disclosures. MDedge is a member of the Medscape Professional Network.

Among 3,970 patients treated during the early months of the pandemic, new onset AF/AFL was seen in 4%, matching the 4% incidence found in a historic cohort of patients hospitalized with influenza.

On the other hand, mortality was similarly high in both groups of patients studied with AF/AFL, showing a 77% increased risk of death in COVID-19 and a 78% increased risk in influenza, a team from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York reported.

“We saw new onset Afib and flutter in a minority of patients and it was associated with much higher mortality, but the point is that this increase is basically the same as what you see in influenza, which we feel is an indication that this is more of a generalized response to the inflammatory milieu of such a severe viral illness, as opposed to something specific to COVID,” Vivek Y. Reddy, MD, said in the report, published online Feb. 25 in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology.

“Here we see, with a similar respiratory virus used as controls, that the results are exactly what I would have expected to see, which is that where there is a lot of inflammation, we see Afib,” said John Mandrola, MD, of Baptist Medical Associates, Louisville, Ky., who was not involved with the study.

“We need more studies like this one because we know SARS-CoV-2 is a bad virus that may have important effects on the heart, but all the of research done so far has been problematic because it didn’t include controls.”

Atrial arrhythmias in COVID and flu

Dr. Reddy and coinvestigators performed a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients admitted with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 during Feb. 4-April 22, 2020, to one of five hospitals within the Mount Sinai Health System.

Their comparator arm included 1,420 patients with confirmed influenza A or B hospitalized between Jan. 1, 2017, and Jan. 1, 2020. For both cohorts, automated electronic record abstraction was used and all patient data were de-identified prior to analysis. In the COVID-19 cohort, a manual review of 1,110 charts was also performed.

Compared with those who did not develop AF/AFL, COVID-19 patients with newly detected AF/AFL and COVID-19 were older (74 vs. 66 years; P < .01) and had higher levels of inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and higher troponin and D-dimer levels (all P < .01).

Overall, including those with a history of atrial arrhythmias, 10% of patients with hospitalized COVID-19 (13% in the manual review) and 12% of those with influenza had AF/AFL detected during their hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days was higher in COVID-19 patients with AF/AFL compared to those without (46% vs. 26%; P < .01), as were the rates of intubation (27% vs. 15%; relative risk, 1.8; P < .01), and stroke (1.6% vs. 0.6%, RR, 2.7; P = .05).

Despite having more comorbidities, in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the influenza cohort overall, compared to the COVID-19 cohort (9% vs. 29%; P < .01), reflecting the higher case fatality rate in COVID-19, Dr. Reddy, director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Mount Sinai Hospital, said in an interview.

But as with COVID-19, those influenza patients who had in-hospital AF/AFL were more likely to require intubation (14% vs. 7%; P = .004) or die (16% vs. 10%; P = .003).

“The data are not perfect and there are always limitations when doing an observational study using historic controls, but my guess would be that if we looked at other databases and other populations hospitalized for severe illness, we’d likely see something similar because when the body is inflamed, you’re more likely to see Afib,” said Dr. Mandrola.

Dr. Reddy concurred, noting that they considered comparing other populations to COVID-19 patients, including those with “just generalized severe illness,” but in the end felt there were many similarities between influenza and COVID-19, even though mortality in the latter is higher.

“It would be interesting for people to look at other illnesses and see if they find the same thing,” he said.

Dr. Reddy reported having no disclosures relevant to COVID-19. Dr. Mandrola is chief cardiology correspondent for Medscape.com. He reported having no relevant disclosures. MDedge is a member of the Medscape Professional Network.

FROM JACC: CLINICAL ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

How to convince patients muscle pain isn’t a statin Achilles heel: StatinWISE

Another randomized trial, on the heels of the recently published SAMSON, has concluded – many would say confirmed – that .

Affected patients who sorely doubt that conclusion might possibly embrace statins, researchers say, if the new trial’s creative methodology could somehow be applied to them in clinical practice.

The recent SAMSON trial made waves in November 2020 by concluding, with some caveats, that about 90% of the burden of muscle symptoms reported by patients on statins may be attributable to a nocebo effect; that is, they are attributed to the drugs – perhaps because of negative expectations – but not actually caused by them.

The new trial, StatinWISE (Statin Web-based Investigation of Side Effects), triple the size but similar in design and conducted parallel to SAMSON, similarly saw no important differences in patient-reported muscle symptom prevalence or severity during administration of atorvastatin 20 mg/day or placebo, in withdrawal from the study because of such symptoms, or in patient quality of life.

The findings also support years of observational evidence that argues against a statin effect on muscle symptoms except in rare cases of confirmed myopathy, as well as results from randomized trials like ODYSSEY ALTERNATIVE and GAUSS-3, in which significant muscle symptoms in “statin-intolerant” patients were unusual, note StatinWISE investigators in their report, published online Feb. 24 in BMJ, with lead author Emily Herrett, MSc, PhD, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“I’m hoping it can change minds a bit and reassure people. That was part of the reason we did it, to inform this debate about harms and benefits of statins,” principal investigator Liam Smeeth, MBChB, MSc, PhD, from the same institution, said during a virtual press conference on the trial conducted by the U.K. nonprofit Science Media Centre.

“In thinking through whether to take a statin or not, people can be reassured that these muscle symptoms are rare; they aren’t common. Aches and pains are common, but are not caused by statins,” said Dr. Smeeth, who is senior author on the trial publication.

Another goal of the 200-patient study, he said, was to explore whether patients who had experienced muscle symptoms on a statin but were willing to explore whether the statin was to blame could be convinced – depending on what they learned in the trial – to stay on the drugs.

It seemed to work; two-thirds of the participants who finished the study “decided that they would actually want to try starting statins again, which was quite amazing.”

But there was a “slight caveat,” Dr. Smeeth observed. “To join our trial, yes, you had to have had a bad experience with statins, but you probably had to be a little bit open to the idea of trying them again. So, I can’t claim that that two-thirds would apply to everybody in the population.”

Because StatinWISE entered only patients who had reported severe muscle symptoms on a statin but hadn’t showed significant enzymatic evidence of myopathy, all had either taken themselves off the statin or were “considering” it. And the study had excluded anyone with “persistent, generalized, unexplained muscle pain” regardless of any statin therapy.

“This was very deliberately a select group of people who had serious problems taking statins. This was not a random sample by any means,” Dr. Smeeth said.

“The patients in the study were willing to participate and take statins again,” suggesting they “may not be completely representative of all those who believe they experience side effects with statins, as anyone who refused to take statins ever again would not have been recruited,” observed Tim Chico, MBChB, MD, University of Sheffield (England) in a Science Media Centre press release on StatinWISE.

Still, even among this “supersaturated group of people” selected for having had muscle symptoms on statins, Dr. Smeeth said at the briefing, “in almost all cases, their pains and aches were no worse on statins than they were on placebo. We’re not saying that anyone is making up their aches and pains. These are real aches and pains. What we’re showing very clearly is that those aches and pains are no worse on statins than they are on placebo.”

Rechallenge is possible

Some people are more likely than others to experience adverse reactions to any drug, “and that’s true of statins,” Neil J. Stone, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, told this news organization. But StatinWISE underscores that many patients with muscle symptoms on the drugs can be convinced to continue with them rather than stop them entirely.

“The study didn’t say that everybody who has symptoms on a statin is having a nocebo effect,” said Dr. Stone, vice chair for the multisociety 2018 Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol, who was not involved with StatinWISE.

“It simply said,” allowing for some caveats, “that a significant number of patients may have symptoms that don’t preclude them from being rechallenged with a statin again, once they understand what this nocebo effect is.”

And, Dr. Stone said, “it amplifies the 2018 guidelines, with their emphasis on the clinician-patient discussion before starting therapy,” by showing that statin-associated muscle pain isn’t necessarily caused by the drugs and isn’t a reason to stop them.

“That there is a second study confirming SAMSON is helpful, and the results are helpful because they say many of these patients, once they are shown the results, can be rechallenged and will then tolerate statins,” Steven E. Nissen, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“They were able to get two-thirds of those completing the trial into long-term treatment, which I think is obviously very admirable and very important,” said Dr. Nissen, who was GAUSS-3 principal investigator but not associated with StatinWISE.

“I think it is important, however, that we not completely dismiss patients who complain of adverse effects. Because, in fact, there probably are some people who do have muscle-related symptoms,” he said. “But you know, to really call somebody statin intolerant, they really should fail three statins, which would be a very good standard.”

In his experience, said Patrick M. Moriarty, MD, who directs the Atherosclerosis & Lipoprotein-Apheresis Center at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, perhaps 80%-90% of patients who believe they are statin intolerant because of muscle symptoms are actually not statin intolerant at all.

“I think a massive amount of it is supratentorial,” Dr. Moriarty, who was not part of StatinWISE, told this news organization. It comes directly from “what they heard, what they read, or what they were told – and at their age, they’re going to have aches and pains.”

Value of the n-of-1 trial