User login

Navigators improve medication adherence in HFrEF

PHILADELPHIA – Treatment guidelines are clear about optimal treatment of heart failure in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but adherence breakdowns often occur.

So, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston implemented a navigator-administered patient outreach program that led to improved medication adherence over usual care, according to study results reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the study was done at a major academic center, the findings have implications for community practitioners, lead study author Akshay S. Desai, MD, MPH, said in an interview. “The impact of the intervention is clearly greater in those practitioners who manage heart failure and have the least support around them,” he said.

“Our sense is that the kind of population where this intervention would have the greater impact would be a community-dwelling heart failure population managed by community cardiologists, where the infrastructure to provide longitudinal heart failure care is less robust than may be in an academic center,” Dr. Desai said.

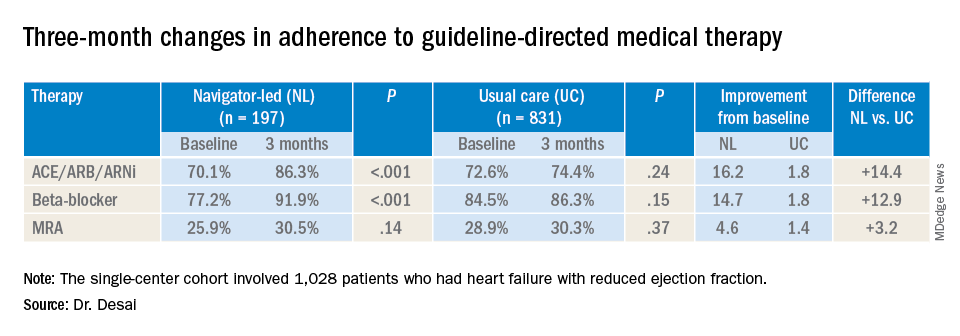

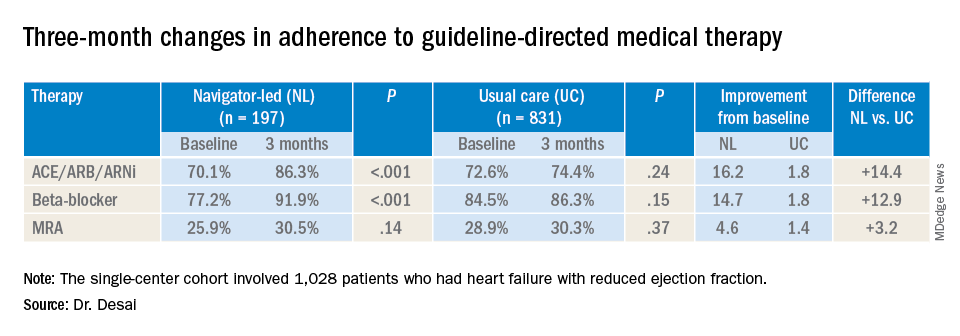

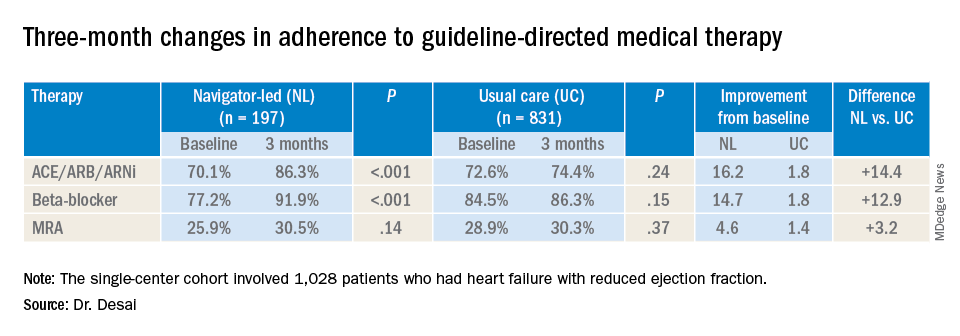

The study evaluated adherence in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at 3 months. “The navigator-led remote medication optimization strategy improved utilization and dosing of all categories of GDMP and was associated with a lower rate of adverse events,” Dr. Desai said. “The impact was more pronounced in patients followed by general practitioners than by a HF specialist.” In the outreach, health navigators contacted patients by phone and managed medications based on remote surveillance of labs, blood pressure, and symptoms under supervision of a pharmacist, nurse practitioner, and heart failure specialist.

The study included 1,028 patients with chronic HFrEF who’d visited a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s in the year prior to the study: 197 patients and their providers consented to participate in the program with the remainder serving as the reference usual-care group. Most HF specialists at Brigham and Women’s declined to participate in the navigator-led program, Dr. Desai said.

Treating providers were approached for consent to adjust medical therapy according to a sequential, stepped titration algorithm modeled on the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF Guidelines. The study population did not include patients with end-stage HF, those with a severe noncardiac illness with a life expectancy of less than a year, and patients with a pattern of nonadherence. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced, Dr. Desai said.

At baseline, 74% (759) participants were treated with ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ACE/ARB/ARNi), 73% (746) with guideline-directed beta-blockers, and 29% (303) with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), with 10% (107) and 11% (117) treated with target doses of ACE/ARB/ARNi and beta-blockers, respectively.

In the navigator-led group, beta-blocker adherence improved from 77.2% at baseline to 91.9% at 3 months (P less than 0.001) compared with an increase from 84.5% to 86.3% in the usual-care patients (P = 0.15), Dr. Desai said. ACE/ARB/ARNi adherence increased 16.2 percentage points to 86.3% (P less than 0.001) in the navigator-group versus 1.8 percentage points to 74.4% (P = 0.24) for usual care. In the MRA subgroup, 3-month adherence to GDMT was almost identical: 30.5% (P = 0.14) and 30.3% (P = 0.37) for the two treatment groups, respectively, although the navigator-led patients averaged a larger increase of 4.6 versus 1.4 percentage points from baseline.

Adverse event rates were similar in both groups, although the navigator group had “slightly higher rates” of hypotension and hyperkalemia but no serious events, Dr. Desai said. This group also had similarly higher rates of worsening renal function, but most were asymptomatic change in creatinine that was addressed with medication changes, he said. There were no hospitalizations for adverse events.

He said the navigator-led optimization has potential in a community setting because the referral nature of Brigham and Women’s HF population “reflects potentially a worst-case scenario for such a program.” The greatest impact was seen in patients managed by general cardiologists, he said. “If we were to move this forward, which we hope to do with scale, the impact might be greater in a community population where there are fewer specialists and less severe illnesses present.”

This study represents a proof of concept, Dr. Desai said in an interview. “What we would like to do is demonstrate that this can be done on a larger scale,” he said. “That might involve partnership with a payer or health care system to see if we can replicate these findings across a broader range of providers.”

Dr. Desai disclosed financial relationships with Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Coston Scientific, Biofourmis, DalCor, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Alnylam. Novartis provided an unrestricted grant for the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Desai AS. AHA 2019 Featured Science session AOS.07.

PHILADELPHIA – Treatment guidelines are clear about optimal treatment of heart failure in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but adherence breakdowns often occur.

So, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston implemented a navigator-administered patient outreach program that led to improved medication adherence over usual care, according to study results reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the study was done at a major academic center, the findings have implications for community practitioners, lead study author Akshay S. Desai, MD, MPH, said in an interview. “The impact of the intervention is clearly greater in those practitioners who manage heart failure and have the least support around them,” he said.

“Our sense is that the kind of population where this intervention would have the greater impact would be a community-dwelling heart failure population managed by community cardiologists, where the infrastructure to provide longitudinal heart failure care is less robust than may be in an academic center,” Dr. Desai said.

The study evaluated adherence in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at 3 months. “The navigator-led remote medication optimization strategy improved utilization and dosing of all categories of GDMP and was associated with a lower rate of adverse events,” Dr. Desai said. “The impact was more pronounced in patients followed by general practitioners than by a HF specialist.” In the outreach, health navigators contacted patients by phone and managed medications based on remote surveillance of labs, blood pressure, and symptoms under supervision of a pharmacist, nurse practitioner, and heart failure specialist.

The study included 1,028 patients with chronic HFrEF who’d visited a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s in the year prior to the study: 197 patients and their providers consented to participate in the program with the remainder serving as the reference usual-care group. Most HF specialists at Brigham and Women’s declined to participate in the navigator-led program, Dr. Desai said.

Treating providers were approached for consent to adjust medical therapy according to a sequential, stepped titration algorithm modeled on the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF Guidelines. The study population did not include patients with end-stage HF, those with a severe noncardiac illness with a life expectancy of less than a year, and patients with a pattern of nonadherence. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced, Dr. Desai said.

At baseline, 74% (759) participants were treated with ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ACE/ARB/ARNi), 73% (746) with guideline-directed beta-blockers, and 29% (303) with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), with 10% (107) and 11% (117) treated with target doses of ACE/ARB/ARNi and beta-blockers, respectively.

In the navigator-led group, beta-blocker adherence improved from 77.2% at baseline to 91.9% at 3 months (P less than 0.001) compared with an increase from 84.5% to 86.3% in the usual-care patients (P = 0.15), Dr. Desai said. ACE/ARB/ARNi adherence increased 16.2 percentage points to 86.3% (P less than 0.001) in the navigator-group versus 1.8 percentage points to 74.4% (P = 0.24) for usual care. In the MRA subgroup, 3-month adherence to GDMT was almost identical: 30.5% (P = 0.14) and 30.3% (P = 0.37) for the two treatment groups, respectively, although the navigator-led patients averaged a larger increase of 4.6 versus 1.4 percentage points from baseline.

Adverse event rates were similar in both groups, although the navigator group had “slightly higher rates” of hypotension and hyperkalemia but no serious events, Dr. Desai said. This group also had similarly higher rates of worsening renal function, but most were asymptomatic change in creatinine that was addressed with medication changes, he said. There were no hospitalizations for adverse events.

He said the navigator-led optimization has potential in a community setting because the referral nature of Brigham and Women’s HF population “reflects potentially a worst-case scenario for such a program.” The greatest impact was seen in patients managed by general cardiologists, he said. “If we were to move this forward, which we hope to do with scale, the impact might be greater in a community population where there are fewer specialists and less severe illnesses present.”

This study represents a proof of concept, Dr. Desai said in an interview. “What we would like to do is demonstrate that this can be done on a larger scale,” he said. “That might involve partnership with a payer or health care system to see if we can replicate these findings across a broader range of providers.”

Dr. Desai disclosed financial relationships with Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Coston Scientific, Biofourmis, DalCor, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Alnylam. Novartis provided an unrestricted grant for the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Desai AS. AHA 2019 Featured Science session AOS.07.

PHILADELPHIA – Treatment guidelines are clear about optimal treatment of heart failure in patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but adherence breakdowns often occur.

So, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston implemented a navigator-administered patient outreach program that led to improved medication adherence over usual care, according to study results reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Although the study was done at a major academic center, the findings have implications for community practitioners, lead study author Akshay S. Desai, MD, MPH, said in an interview. “The impact of the intervention is clearly greater in those practitioners who manage heart failure and have the least support around them,” he said.

“Our sense is that the kind of population where this intervention would have the greater impact would be a community-dwelling heart failure population managed by community cardiologists, where the infrastructure to provide longitudinal heart failure care is less robust than may be in an academic center,” Dr. Desai said.

The study evaluated adherence in guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) at 3 months. “The navigator-led remote medication optimization strategy improved utilization and dosing of all categories of GDMP and was associated with a lower rate of adverse events,” Dr. Desai said. “The impact was more pronounced in patients followed by general practitioners than by a HF specialist.” In the outreach, health navigators contacted patients by phone and managed medications based on remote surveillance of labs, blood pressure, and symptoms under supervision of a pharmacist, nurse practitioner, and heart failure specialist.

The study included 1,028 patients with chronic HFrEF who’d visited a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s in the year prior to the study: 197 patients and their providers consented to participate in the program with the remainder serving as the reference usual-care group. Most HF specialists at Brigham and Women’s declined to participate in the navigator-led program, Dr. Desai said.

Treating providers were approached for consent to adjust medical therapy according to a sequential, stepped titration algorithm modeled on the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF Guidelines. The study population did not include patients with end-stage HF, those with a severe noncardiac illness with a life expectancy of less than a year, and patients with a pattern of nonadherence. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced, Dr. Desai said.

At baseline, 74% (759) participants were treated with ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers/angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ACE/ARB/ARNi), 73% (746) with guideline-directed beta-blockers, and 29% (303) with mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs), with 10% (107) and 11% (117) treated with target doses of ACE/ARB/ARNi and beta-blockers, respectively.

In the navigator-led group, beta-blocker adherence improved from 77.2% at baseline to 91.9% at 3 months (P less than 0.001) compared with an increase from 84.5% to 86.3% in the usual-care patients (P = 0.15), Dr. Desai said. ACE/ARB/ARNi adherence increased 16.2 percentage points to 86.3% (P less than 0.001) in the navigator-group versus 1.8 percentage points to 74.4% (P = 0.24) for usual care. In the MRA subgroup, 3-month adherence to GDMT was almost identical: 30.5% (P = 0.14) and 30.3% (P = 0.37) for the two treatment groups, respectively, although the navigator-led patients averaged a larger increase of 4.6 versus 1.4 percentage points from baseline.

Adverse event rates were similar in both groups, although the navigator group had “slightly higher rates” of hypotension and hyperkalemia but no serious events, Dr. Desai said. This group also had similarly higher rates of worsening renal function, but most were asymptomatic change in creatinine that was addressed with medication changes, he said. There were no hospitalizations for adverse events.

He said the navigator-led optimization has potential in a community setting because the referral nature of Brigham and Women’s HF population “reflects potentially a worst-case scenario for such a program.” The greatest impact was seen in patients managed by general cardiologists, he said. “If we were to move this forward, which we hope to do with scale, the impact might be greater in a community population where there are fewer specialists and less severe illnesses present.”

This study represents a proof of concept, Dr. Desai said in an interview. “What we would like to do is demonstrate that this can be done on a larger scale,” he said. “That might involve partnership with a payer or health care system to see if we can replicate these findings across a broader range of providers.”

Dr. Desai disclosed financial relationships with Novartis, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Coston Scientific, Biofourmis, DalCor, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Alnylam. Novartis provided an unrestricted grant for the investigator-initiated trial.

SOURCE: Desai AS. AHA 2019 Featured Science session AOS.07.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

Low RAAS inhibitor dosing linked to MACE risk

Suboptimal dosing of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors to reduce the risk of hyperkalemia could increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or heart failure.

Researchers reported the outcomes of an observational study that explored the real-world associations between RAAS inhibitor dose, hyperkalemia, and clinical outcomes.

RAAS inhibitors – such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists – are known to reduce potassium excretion and therefore increase the risk of high potassium levels.

Dr. Cecilia Linde, from the Karolinska University Hospital and Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and coauthors wrote that management of serum potassium levels often requires reducing the dosage of RAAS inhibitors or stopping them altogether. However, this is also associated with risks in patients with heart failure or CKD.

In this study, researchers looked at data from 100,572 people with nondialysis CKD and 13,113 with new-onset heart failure who were prescribed RAAS inhibitors during 2006-2015.

Overall, 58% of patients with CKD and 63% of patients with heart failure spent the majority of follow-up on prescribed optimal doses of RAAS inhibitors – defined as at least 50% of the guidelines-recommended dose.

Patients with hyperkalemia were more likely to have down-titrations or discontinue their RAAS inhibitors, and this increased with increasing hyperkalemia severity.

The study found consistently lower mortality rates among patients who spent most of their follow-up time on at least 50% of the guideline-recommended dose of RAAS inhibitors.

In patients with CKD, mortality rates were 7.2 deaths per 1,000 patient-years in those taking at least 50% of the recommended dose, compared with 57.7 deaths per 1,000 patient-years for those on suboptimal doses. The rates of MACE were 73 and 130 per 1,000 patient-years, respectively.

The differences were even more pronounced in patients with heart failure. Those taking at least 50% of the recommended dose had mortality rates of 12.5 per 1000 patient-years, compared with 141.7 among those on suboptimal doses. The rates of MACE were 148.5 and 290.4, respectively.

“The results highlight the potential negative impact of suboptimal RAASi dosing, indicate the generalizability of [European Society of Cardiology–recommended] RAASi doses in HF to CKD patients, and emphasize the need for strategies that allow patients to be maintained on appropriate therapy, avoiding RAASi dose modification or discontinuation,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. One author was an employee and stockholder of AstraZeneca, and five authors declared funding and support from the pharmaceutical sector, including AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Linde C et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012655.

Suboptimal dosing of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors to reduce the risk of hyperkalemia could increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or heart failure.

Researchers reported the outcomes of an observational study that explored the real-world associations between RAAS inhibitor dose, hyperkalemia, and clinical outcomes.

RAAS inhibitors – such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists – are known to reduce potassium excretion and therefore increase the risk of high potassium levels.

Dr. Cecilia Linde, from the Karolinska University Hospital and Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and coauthors wrote that management of serum potassium levels often requires reducing the dosage of RAAS inhibitors or stopping them altogether. However, this is also associated with risks in patients with heart failure or CKD.

In this study, researchers looked at data from 100,572 people with nondialysis CKD and 13,113 with new-onset heart failure who were prescribed RAAS inhibitors during 2006-2015.

Overall, 58% of patients with CKD and 63% of patients with heart failure spent the majority of follow-up on prescribed optimal doses of RAAS inhibitors – defined as at least 50% of the guidelines-recommended dose.

Patients with hyperkalemia were more likely to have down-titrations or discontinue their RAAS inhibitors, and this increased with increasing hyperkalemia severity.

The study found consistently lower mortality rates among patients who spent most of their follow-up time on at least 50% of the guideline-recommended dose of RAAS inhibitors.

In patients with CKD, mortality rates were 7.2 deaths per 1,000 patient-years in those taking at least 50% of the recommended dose, compared with 57.7 deaths per 1,000 patient-years for those on suboptimal doses. The rates of MACE were 73 and 130 per 1,000 patient-years, respectively.

The differences were even more pronounced in patients with heart failure. Those taking at least 50% of the recommended dose had mortality rates of 12.5 per 1000 patient-years, compared with 141.7 among those on suboptimal doses. The rates of MACE were 148.5 and 290.4, respectively.

“The results highlight the potential negative impact of suboptimal RAASi dosing, indicate the generalizability of [European Society of Cardiology–recommended] RAASi doses in HF to CKD patients, and emphasize the need for strategies that allow patients to be maintained on appropriate therapy, avoiding RAASi dose modification or discontinuation,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. One author was an employee and stockholder of AstraZeneca, and five authors declared funding and support from the pharmaceutical sector, including AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Linde C et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012655.

Suboptimal dosing of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors to reduce the risk of hyperkalemia could increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or heart failure.

Researchers reported the outcomes of an observational study that explored the real-world associations between RAAS inhibitor dose, hyperkalemia, and clinical outcomes.

RAAS inhibitors – such as ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists – are known to reduce potassium excretion and therefore increase the risk of high potassium levels.

Dr. Cecilia Linde, from the Karolinska University Hospital and Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and coauthors wrote that management of serum potassium levels often requires reducing the dosage of RAAS inhibitors or stopping them altogether. However, this is also associated with risks in patients with heart failure or CKD.

In this study, researchers looked at data from 100,572 people with nondialysis CKD and 13,113 with new-onset heart failure who were prescribed RAAS inhibitors during 2006-2015.

Overall, 58% of patients with CKD and 63% of patients with heart failure spent the majority of follow-up on prescribed optimal doses of RAAS inhibitors – defined as at least 50% of the guidelines-recommended dose.

Patients with hyperkalemia were more likely to have down-titrations or discontinue their RAAS inhibitors, and this increased with increasing hyperkalemia severity.

The study found consistently lower mortality rates among patients who spent most of their follow-up time on at least 50% of the guideline-recommended dose of RAAS inhibitors.

In patients with CKD, mortality rates were 7.2 deaths per 1,000 patient-years in those taking at least 50% of the recommended dose, compared with 57.7 deaths per 1,000 patient-years for those on suboptimal doses. The rates of MACE were 73 and 130 per 1,000 patient-years, respectively.

The differences were even more pronounced in patients with heart failure. Those taking at least 50% of the recommended dose had mortality rates of 12.5 per 1000 patient-years, compared with 141.7 among those on suboptimal doses. The rates of MACE were 148.5 and 290.4, respectively.

“The results highlight the potential negative impact of suboptimal RAASi dosing, indicate the generalizability of [European Society of Cardiology–recommended] RAASi doses in HF to CKD patients, and emphasize the need for strategies that allow patients to be maintained on appropriate therapy, avoiding RAASi dose modification or discontinuation,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca. One author was an employee and stockholder of AstraZeneca, and five authors declared funding and support from the pharmaceutical sector, including AstraZeneca.

SOURCE: Linde C et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Nov 12. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012655.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Hydroxychloroquine prevents congenital heart block recurrence in anti-Ro pregnancies

ATLANTA – Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 400 mg/day starting by pregnancy week 10 reduces recurrence of congenital heart block in infants born to women with anti-Ro antibodies, according to an open-label, prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Among antibody-positive women who had a previous pregnancy complicated by congenital heart block (CHB), the regimen reduced recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy from the expected historical rate of 18% to 7.4%, a more than 50% drop. “Given the potential benefit of hydroxychloroquine” (HCQ) and its relative safety during pregnancy, “testing all pregnancies for anti-Ro antibodies, regardless of maternal health, should be considered,” concluded investigators led by rheumatologist Peter Izmirly, MD, associate professor of medicine at New York (N.Y.) University.

About 40% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus and nearly 100% of women with Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as about 1% of women in the general population, have anti-Ro antibodies. They can be present in completely asymptomatic women, which is why the authors called for general screening. Indeed, half of the women in the trial had no or only mild, undifferentiated rheumatic symptoms. Often, “women who carry anti-Ro antibodies have no idea they have them” until they have a child with CHB and are tested, Dr. Izmirly said.

The antibodies cross the placenta and interfere with the normal development of the AV node; about 18% of infants die and most of the rest require lifelong pacing. The risk of CHB in antibody-positive women is about 2%, but once a child is born with the condition, the risk climbs to about 18% in subsequent pregnancies.

Years ago, Dr. Izmirly and his colleagues had a hunch that HCQ might help because it disrupts the toll-like receptor signaling involved in the disease process. A database review he led added weight to the idea, finding that among 257 anti-Ro positive pregnancies, the rate of CHB was 7.5% among the 40 women who happened to take HCQ, versus 21.2% among the 217 who did not. “We wanted to see if we could replicate that prospectively,” he said.

The Preventive Approach to Congenital Heart Block with Hydroxychloroquine (PATCH) trial enrolled 54 antibody positive women with a previous CHB pregnancy. They were started on 400 mg/day HCQ by gestation week 10.

There were four cases of second- or third-degree CHB among the women (7.4%, P = 0.02), all detected by fetal echocardiogram around week 20.

Nine of the women were treated with IVIG and/or dexamethasone for lupus flares or fetal heart issues other than advanced block, which confounded the results. To analyze the effect in a purely HCQ cohort, the team recruited an additional nine women not treated with any other medication during pregnancy, one of whose fetus developed third-degree heart block.

In total, 5 of 63 pregnancies (7.9%) resulted in advanced block. Among the 54 women exposed only to HCQ, the rate of second- or third-degree block was again 7.4% (4 of 54, P = .02). HCQ compliance, assessed by maternal blood levels above 200 ng/mL at least once, was 98%, and cord blood confirmed fetal exposure to HCQ.

Once detected, CHB was treated with dexamethasone or IVIG. One case progressed to cardiomyopathy, and the pregnancy was terminated. Another child required pacing after birth. Other children reverted to normal sinus rhythm but had intermittent second-degree block at age 2.

Overall, “the safety in this study was excellent,” said rheumatologist and senior investigator Jill Buyon, MD, director of the division of rheumatology at New York University.

The complications – nine births before 37 weeks, one infant small for gestational age – were not unexpected in a rheumatic population. “We were very nervous about Plaquenil cardiomyopathy” in the pregnancy that was terminated, but there was no evidence of it on histology.

The children will have ocular optical coherence tomography at age 5 to check for retinal toxicity; the 12 who have been tested so far show no obvious signs. Dr. Izmirly said he doesn’t expect to see any problems. “We are just being super cautious.”

The audience had questions about why the trial didn’t have a placebo arm. He explained that CHB is a rare event – one in 15,000 pregnancies – and it took 8 years just to adequately power the single-arm study; recruiting more than 100 additional women for a placebo-controlled trial wasn’t practical.

Also, “there was no way” women were going to be randomized to placebo when HCQ seemed so promising; 35% of the enrollees had already lost a child to CHB. “Everyone wanted the drug,” Dr. Izmirly said.

The majority of women were white, and about half met criteria for lupus and/or Sjögren’s. Anti-Ro levels remained above 1,000 EU throughout pregnancy. Women were excluded if they were taking high-dose prednisone or any dose of fluorinated corticosteroids at baseline.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Izmirly P et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 1761.

ATLANTA – Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 400 mg/day starting by pregnancy week 10 reduces recurrence of congenital heart block in infants born to women with anti-Ro antibodies, according to an open-label, prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Among antibody-positive women who had a previous pregnancy complicated by congenital heart block (CHB), the regimen reduced recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy from the expected historical rate of 18% to 7.4%, a more than 50% drop. “Given the potential benefit of hydroxychloroquine” (HCQ) and its relative safety during pregnancy, “testing all pregnancies for anti-Ro antibodies, regardless of maternal health, should be considered,” concluded investigators led by rheumatologist Peter Izmirly, MD, associate professor of medicine at New York (N.Y.) University.

About 40% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus and nearly 100% of women with Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as about 1% of women in the general population, have anti-Ro antibodies. They can be present in completely asymptomatic women, which is why the authors called for general screening. Indeed, half of the women in the trial had no or only mild, undifferentiated rheumatic symptoms. Often, “women who carry anti-Ro antibodies have no idea they have them” until they have a child with CHB and are tested, Dr. Izmirly said.

The antibodies cross the placenta and interfere with the normal development of the AV node; about 18% of infants die and most of the rest require lifelong pacing. The risk of CHB in antibody-positive women is about 2%, but once a child is born with the condition, the risk climbs to about 18% in subsequent pregnancies.

Years ago, Dr. Izmirly and his colleagues had a hunch that HCQ might help because it disrupts the toll-like receptor signaling involved in the disease process. A database review he led added weight to the idea, finding that among 257 anti-Ro positive pregnancies, the rate of CHB was 7.5% among the 40 women who happened to take HCQ, versus 21.2% among the 217 who did not. “We wanted to see if we could replicate that prospectively,” he said.

The Preventive Approach to Congenital Heart Block with Hydroxychloroquine (PATCH) trial enrolled 54 antibody positive women with a previous CHB pregnancy. They were started on 400 mg/day HCQ by gestation week 10.

There were four cases of second- or third-degree CHB among the women (7.4%, P = 0.02), all detected by fetal echocardiogram around week 20.

Nine of the women were treated with IVIG and/or dexamethasone for lupus flares or fetal heart issues other than advanced block, which confounded the results. To analyze the effect in a purely HCQ cohort, the team recruited an additional nine women not treated with any other medication during pregnancy, one of whose fetus developed third-degree heart block.

In total, 5 of 63 pregnancies (7.9%) resulted in advanced block. Among the 54 women exposed only to HCQ, the rate of second- or third-degree block was again 7.4% (4 of 54, P = .02). HCQ compliance, assessed by maternal blood levels above 200 ng/mL at least once, was 98%, and cord blood confirmed fetal exposure to HCQ.

Once detected, CHB was treated with dexamethasone or IVIG. One case progressed to cardiomyopathy, and the pregnancy was terminated. Another child required pacing after birth. Other children reverted to normal sinus rhythm but had intermittent second-degree block at age 2.

Overall, “the safety in this study was excellent,” said rheumatologist and senior investigator Jill Buyon, MD, director of the division of rheumatology at New York University.

The complications – nine births before 37 weeks, one infant small for gestational age – were not unexpected in a rheumatic population. “We were very nervous about Plaquenil cardiomyopathy” in the pregnancy that was terminated, but there was no evidence of it on histology.

The children will have ocular optical coherence tomography at age 5 to check for retinal toxicity; the 12 who have been tested so far show no obvious signs. Dr. Izmirly said he doesn’t expect to see any problems. “We are just being super cautious.”

The audience had questions about why the trial didn’t have a placebo arm. He explained that CHB is a rare event – one in 15,000 pregnancies – and it took 8 years just to adequately power the single-arm study; recruiting more than 100 additional women for a placebo-controlled trial wasn’t practical.

Also, “there was no way” women were going to be randomized to placebo when HCQ seemed so promising; 35% of the enrollees had already lost a child to CHB. “Everyone wanted the drug,” Dr. Izmirly said.

The majority of women were white, and about half met criteria for lupus and/or Sjögren’s. Anti-Ro levels remained above 1,000 EU throughout pregnancy. Women were excluded if they were taking high-dose prednisone or any dose of fluorinated corticosteroids at baseline.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Izmirly P et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 1761.

ATLANTA – Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 400 mg/day starting by pregnancy week 10 reduces recurrence of congenital heart block in infants born to women with anti-Ro antibodies, according to an open-label, prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Among antibody-positive women who had a previous pregnancy complicated by congenital heart block (CHB), the regimen reduced recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy from the expected historical rate of 18% to 7.4%, a more than 50% drop. “Given the potential benefit of hydroxychloroquine” (HCQ) and its relative safety during pregnancy, “testing all pregnancies for anti-Ro antibodies, regardless of maternal health, should be considered,” concluded investigators led by rheumatologist Peter Izmirly, MD, associate professor of medicine at New York (N.Y.) University.

About 40% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus and nearly 100% of women with Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as about 1% of women in the general population, have anti-Ro antibodies. They can be present in completely asymptomatic women, which is why the authors called for general screening. Indeed, half of the women in the trial had no or only mild, undifferentiated rheumatic symptoms. Often, “women who carry anti-Ro antibodies have no idea they have them” until they have a child with CHB and are tested, Dr. Izmirly said.

The antibodies cross the placenta and interfere with the normal development of the AV node; about 18% of infants die and most of the rest require lifelong pacing. The risk of CHB in antibody-positive women is about 2%, but once a child is born with the condition, the risk climbs to about 18% in subsequent pregnancies.

Years ago, Dr. Izmirly and his colleagues had a hunch that HCQ might help because it disrupts the toll-like receptor signaling involved in the disease process. A database review he led added weight to the idea, finding that among 257 anti-Ro positive pregnancies, the rate of CHB was 7.5% among the 40 women who happened to take HCQ, versus 21.2% among the 217 who did not. “We wanted to see if we could replicate that prospectively,” he said.

The Preventive Approach to Congenital Heart Block with Hydroxychloroquine (PATCH) trial enrolled 54 antibody positive women with a previous CHB pregnancy. They were started on 400 mg/day HCQ by gestation week 10.

There were four cases of second- or third-degree CHB among the women (7.4%, P = 0.02), all detected by fetal echocardiogram around week 20.

Nine of the women were treated with IVIG and/or dexamethasone for lupus flares or fetal heart issues other than advanced block, which confounded the results. To analyze the effect in a purely HCQ cohort, the team recruited an additional nine women not treated with any other medication during pregnancy, one of whose fetus developed third-degree heart block.

In total, 5 of 63 pregnancies (7.9%) resulted in advanced block. Among the 54 women exposed only to HCQ, the rate of second- or third-degree block was again 7.4% (4 of 54, P = .02). HCQ compliance, assessed by maternal blood levels above 200 ng/mL at least once, was 98%, and cord blood confirmed fetal exposure to HCQ.

Once detected, CHB was treated with dexamethasone or IVIG. One case progressed to cardiomyopathy, and the pregnancy was terminated. Another child required pacing after birth. Other children reverted to normal sinus rhythm but had intermittent second-degree block at age 2.

Overall, “the safety in this study was excellent,” said rheumatologist and senior investigator Jill Buyon, MD, director of the division of rheumatology at New York University.

The complications – nine births before 37 weeks, one infant small for gestational age – were not unexpected in a rheumatic population. “We were very nervous about Plaquenil cardiomyopathy” in the pregnancy that was terminated, but there was no evidence of it on histology.

The children will have ocular optical coherence tomography at age 5 to check for retinal toxicity; the 12 who have been tested so far show no obvious signs. Dr. Izmirly said he doesn’t expect to see any problems. “We are just being super cautious.”

The audience had questions about why the trial didn’t have a placebo arm. He explained that CHB is a rare event – one in 15,000 pregnancies – and it took 8 years just to adequately power the single-arm study; recruiting more than 100 additional women for a placebo-controlled trial wasn’t practical.

Also, “there was no way” women were going to be randomized to placebo when HCQ seemed so promising; 35% of the enrollees had already lost a child to CHB. “Everyone wanted the drug,” Dr. Izmirly said.

The majority of women were white, and about half met criteria for lupus and/or Sjögren’s. Anti-Ro levels remained above 1,000 EU throughout pregnancy. Women were excluded if they were taking high-dose prednisone or any dose of fluorinated corticosteroids at baseline.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Izmirly P et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 1761.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Mechanical circulatory support in PCI needs clearer guidance

PHILADELPHIA – Use of the Impella ventricular-assist device in patients with cardiogenic shock having percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) has increased rapidly since its approval in 2008, but two studies comparing it with intra-aortic balloon pumps in PCI patients have raised questions about the safety, effectiveness, and cost of the ventricular-assist device, according to results of two studies presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The results of an observational analysis of 48,306 patients and a national real-world study of 28,304 patients may not be telling the complete story of the utility of ventricular assist in patients requiring mechanical circulatory support (MCS), one interventional cardiologist said in an interview. “It’s concerning; it’s sobering,” said Ranya N. Sweis, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. However, the data didn’t parse out patients who would have been routed to palliative care and otherwise wouldn’t have been candidates for PCI without MCS.

“What I take from it is that we need to get more randomized data,” she said. “Who are the patients that were doing worse? Who are the patients who really needed the Impella support for the PCI after cardiogenic shock?”

In the observational study, Amit P. Amin, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis, said that the use of MCS devices increased steadily to 32% of all PCI patients receiving MCS from 2008 to 2016 while use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) declined, but that Impella was less likely to be used in critically ill patients. The study analyzed patients in the Premier Healthcare Database who had PCI with MCS at 432 hospitals from 2004 to 2016.

Outcomes in what Dr. Amin called “the Impella era,” showed significantly higher risks for death, acute kidney injury, and stroke, with odds ratios of 1.17, 1.91 and 3.34, respectively (P less than .001 for all). In the patient-level comparison of Impella versus IABP, Impella had a 24% higher risk of death (P less than .0001), 10% for bleeding (P = .0445), 8% for acute kidney injury (P = .0521) and 34% for stroke (P less than .0001). The findings were published simultaneously with the presentation (Circulation. 2019 Nov 17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044007)

“The total length of stay, as well as the ICU length of stay, were actually lower with Impella use, by approximately a half day to 1 day,” Dr. Amin said. “Despite that, the total costs were approximately $15,000.”

Yet, the study found wide variation in the use of Impella among hospitals, some doing no cases with the device and others all of them, Dr. Amin said. The risk analysis also found wide variations in outcomes across hospitals using Impella. “We saw a 2.5-fold variation in bleeding across hospitals and a 1.5-fold variation in acute kidney injury, stroke and death,” he noted. The study found less variation in hospital stays and total cost of Impella, “perhaps related to the uniformly high device acquisition costs.”

“These data underscore the need for defining the appropriate use of mechanical circulatory support in patients undergoing PCI,” Dr. Amin said.

Dr. Sweis wasn’t surprised by the cost findings. “New technology is going to cost more,” she said in an interview. “I’m actually surprised that the cost wasn’t more significantly different just knowing the cost of some of these devices.

Patients who require MCS represent a small portion of PCI cases: 2%, according to Dr. Sweis. “It’s not like all PCI has increased because of MCS, and there’s a potential improvement in the length of stay so there are going to be cost savings that way.”

The national real-world study that Sanket S. Dhruva, MD, MHS, of the University of California San Francisco, reported on focused on Impella and IABP in PCI patients with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The study used outcomes of patients with AMI-CS who had PCI from October 2015 to December 2017 in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s CathPCI and Chest Pain–MI registries. An estimated 4%-12% of AMIs present with CS.

Most patients in the study population had medical therapy only, but this study focused on the 1,768 who had Impella only and the 8,471 who had IABP only. The rates of in-hospital death and bleeding were 34.1% 16% in the IABP group, and 45% and 31.3% in the Impella group, Dr. Dhruva said. In this study population, the rate of Impella use increased from 3.5% in 2015 to 8.7% by the end of 2017 (P less than .001).

Dr. Dhruva acknowledged a number of limitations to the study findings, including residual confounding. However, the “robust propensity match” of 95% of the Impella-only patients and the results were consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses. “There may have been questions about the clinical severity of AMI-CS patients in the NCDR Registry,” he said. “However, the registry definition is similar to that used in the trials.”

The trial also failed to distinguish between the different types of Impella devices, but the results mostly pertain to the Impella 2.5 and CP because the 5.0 device requires a surgical cutdown, and the study excluded patients who received multiple devices.

“Better evidence and guidance are needed regarding the optimal management of patients with AMI-CS as well as the role of mechanical circulatory support devices in general and Impella in particular,” he said, adding that Impella has been on the U.S. market since 2008, but with limited randomized clinical trial evidence in cardiogenic shock.

The study population of patient’s with CS is “only a piece of the puzzle,” Dr. Sweis said. “We know that there are sick hearts that aren’t in shock right now, but you’re going to do triple-vessel intervention and use atherectomy. Those patients would not do very well during the procedure itself and it may not even be offered to them if there weren’t support.”

Impella is not going away, Dr. Sweis said. “It provides an option that a patient wouldn’t otherwise have. This is really stressing to me that we need to get rid of that variability in the safety related to these devices.”

Dr. Amin disclosed financial relationships with Terumo and GE Healthcare. Dr. Dhruva had no financial relationships to disclose. The study was supported in part by a Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation grant from the Food and Drug Administration and the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

PHILADELPHIA – Use of the Impella ventricular-assist device in patients with cardiogenic shock having percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) has increased rapidly since its approval in 2008, but two studies comparing it with intra-aortic balloon pumps in PCI patients have raised questions about the safety, effectiveness, and cost of the ventricular-assist device, according to results of two studies presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The results of an observational analysis of 48,306 patients and a national real-world study of 28,304 patients may not be telling the complete story of the utility of ventricular assist in patients requiring mechanical circulatory support (MCS), one interventional cardiologist said in an interview. “It’s concerning; it’s sobering,” said Ranya N. Sweis, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. However, the data didn’t parse out patients who would have been routed to palliative care and otherwise wouldn’t have been candidates for PCI without MCS.

“What I take from it is that we need to get more randomized data,” she said. “Who are the patients that were doing worse? Who are the patients who really needed the Impella support for the PCI after cardiogenic shock?”

In the observational study, Amit P. Amin, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis, said that the use of MCS devices increased steadily to 32% of all PCI patients receiving MCS from 2008 to 2016 while use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) declined, but that Impella was less likely to be used in critically ill patients. The study analyzed patients in the Premier Healthcare Database who had PCI with MCS at 432 hospitals from 2004 to 2016.

Outcomes in what Dr. Amin called “the Impella era,” showed significantly higher risks for death, acute kidney injury, and stroke, with odds ratios of 1.17, 1.91 and 3.34, respectively (P less than .001 for all). In the patient-level comparison of Impella versus IABP, Impella had a 24% higher risk of death (P less than .0001), 10% for bleeding (P = .0445), 8% for acute kidney injury (P = .0521) and 34% for stroke (P less than .0001). The findings were published simultaneously with the presentation (Circulation. 2019 Nov 17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044007)

“The total length of stay, as well as the ICU length of stay, were actually lower with Impella use, by approximately a half day to 1 day,” Dr. Amin said. “Despite that, the total costs were approximately $15,000.”

Yet, the study found wide variation in the use of Impella among hospitals, some doing no cases with the device and others all of them, Dr. Amin said. The risk analysis also found wide variations in outcomes across hospitals using Impella. “We saw a 2.5-fold variation in bleeding across hospitals and a 1.5-fold variation in acute kidney injury, stroke and death,” he noted. The study found less variation in hospital stays and total cost of Impella, “perhaps related to the uniformly high device acquisition costs.”

“These data underscore the need for defining the appropriate use of mechanical circulatory support in patients undergoing PCI,” Dr. Amin said.

Dr. Sweis wasn’t surprised by the cost findings. “New technology is going to cost more,” she said in an interview. “I’m actually surprised that the cost wasn’t more significantly different just knowing the cost of some of these devices.

Patients who require MCS represent a small portion of PCI cases: 2%, according to Dr. Sweis. “It’s not like all PCI has increased because of MCS, and there’s a potential improvement in the length of stay so there are going to be cost savings that way.”

The national real-world study that Sanket S. Dhruva, MD, MHS, of the University of California San Francisco, reported on focused on Impella and IABP in PCI patients with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The study used outcomes of patients with AMI-CS who had PCI from October 2015 to December 2017 in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s CathPCI and Chest Pain–MI registries. An estimated 4%-12% of AMIs present with CS.

Most patients in the study population had medical therapy only, but this study focused on the 1,768 who had Impella only and the 8,471 who had IABP only. The rates of in-hospital death and bleeding were 34.1% 16% in the IABP group, and 45% and 31.3% in the Impella group, Dr. Dhruva said. In this study population, the rate of Impella use increased from 3.5% in 2015 to 8.7% by the end of 2017 (P less than .001).

Dr. Dhruva acknowledged a number of limitations to the study findings, including residual confounding. However, the “robust propensity match” of 95% of the Impella-only patients and the results were consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses. “There may have been questions about the clinical severity of AMI-CS patients in the NCDR Registry,” he said. “However, the registry definition is similar to that used in the trials.”

The trial also failed to distinguish between the different types of Impella devices, but the results mostly pertain to the Impella 2.5 and CP because the 5.0 device requires a surgical cutdown, and the study excluded patients who received multiple devices.

“Better evidence and guidance are needed regarding the optimal management of patients with AMI-CS as well as the role of mechanical circulatory support devices in general and Impella in particular,” he said, adding that Impella has been on the U.S. market since 2008, but with limited randomized clinical trial evidence in cardiogenic shock.

The study population of patient’s with CS is “only a piece of the puzzle,” Dr. Sweis said. “We know that there are sick hearts that aren’t in shock right now, but you’re going to do triple-vessel intervention and use atherectomy. Those patients would not do very well during the procedure itself and it may not even be offered to them if there weren’t support.”

Impella is not going away, Dr. Sweis said. “It provides an option that a patient wouldn’t otherwise have. This is really stressing to me that we need to get rid of that variability in the safety related to these devices.”

Dr. Amin disclosed financial relationships with Terumo and GE Healthcare. Dr. Dhruva had no financial relationships to disclose. The study was supported in part by a Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation grant from the Food and Drug Administration and the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

PHILADELPHIA – Use of the Impella ventricular-assist device in patients with cardiogenic shock having percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) has increased rapidly since its approval in 2008, but two studies comparing it with intra-aortic balloon pumps in PCI patients have raised questions about the safety, effectiveness, and cost of the ventricular-assist device, according to results of two studies presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The results of an observational analysis of 48,306 patients and a national real-world study of 28,304 patients may not be telling the complete story of the utility of ventricular assist in patients requiring mechanical circulatory support (MCS), one interventional cardiologist said in an interview. “It’s concerning; it’s sobering,” said Ranya N. Sweis, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago. However, the data didn’t parse out patients who would have been routed to palliative care and otherwise wouldn’t have been candidates for PCI without MCS.

“What I take from it is that we need to get more randomized data,” she said. “Who are the patients that were doing worse? Who are the patients who really needed the Impella support for the PCI after cardiogenic shock?”

In the observational study, Amit P. Amin, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis, said that the use of MCS devices increased steadily to 32% of all PCI patients receiving MCS from 2008 to 2016 while use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) declined, but that Impella was less likely to be used in critically ill patients. The study analyzed patients in the Premier Healthcare Database who had PCI with MCS at 432 hospitals from 2004 to 2016.

Outcomes in what Dr. Amin called “the Impella era,” showed significantly higher risks for death, acute kidney injury, and stroke, with odds ratios of 1.17, 1.91 and 3.34, respectively (P less than .001 for all). In the patient-level comparison of Impella versus IABP, Impella had a 24% higher risk of death (P less than .0001), 10% for bleeding (P = .0445), 8% for acute kidney injury (P = .0521) and 34% for stroke (P less than .0001). The findings were published simultaneously with the presentation (Circulation. 2019 Nov 17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044007)

“The total length of stay, as well as the ICU length of stay, were actually lower with Impella use, by approximately a half day to 1 day,” Dr. Amin said. “Despite that, the total costs were approximately $15,000.”

Yet, the study found wide variation in the use of Impella among hospitals, some doing no cases with the device and others all of them, Dr. Amin said. The risk analysis also found wide variations in outcomes across hospitals using Impella. “We saw a 2.5-fold variation in bleeding across hospitals and a 1.5-fold variation in acute kidney injury, stroke and death,” he noted. The study found less variation in hospital stays and total cost of Impella, “perhaps related to the uniformly high device acquisition costs.”

“These data underscore the need for defining the appropriate use of mechanical circulatory support in patients undergoing PCI,” Dr. Amin said.

Dr. Sweis wasn’t surprised by the cost findings. “New technology is going to cost more,” she said in an interview. “I’m actually surprised that the cost wasn’t more significantly different just knowing the cost of some of these devices.

Patients who require MCS represent a small portion of PCI cases: 2%, according to Dr. Sweis. “It’s not like all PCI has increased because of MCS, and there’s a potential improvement in the length of stay so there are going to be cost savings that way.”

The national real-world study that Sanket S. Dhruva, MD, MHS, of the University of California San Francisco, reported on focused on Impella and IABP in PCI patients with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (CS). The study used outcomes of patients with AMI-CS who had PCI from October 2015 to December 2017 in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s CathPCI and Chest Pain–MI registries. An estimated 4%-12% of AMIs present with CS.

Most patients in the study population had medical therapy only, but this study focused on the 1,768 who had Impella only and the 8,471 who had IABP only. The rates of in-hospital death and bleeding were 34.1% 16% in the IABP group, and 45% and 31.3% in the Impella group, Dr. Dhruva said. In this study population, the rate of Impella use increased from 3.5% in 2015 to 8.7% by the end of 2017 (P less than .001).

Dr. Dhruva acknowledged a number of limitations to the study findings, including residual confounding. However, the “robust propensity match” of 95% of the Impella-only patients and the results were consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses. “There may have been questions about the clinical severity of AMI-CS patients in the NCDR Registry,” he said. “However, the registry definition is similar to that used in the trials.”

The trial also failed to distinguish between the different types of Impella devices, but the results mostly pertain to the Impella 2.5 and CP because the 5.0 device requires a surgical cutdown, and the study excluded patients who received multiple devices.

“Better evidence and guidance are needed regarding the optimal management of patients with AMI-CS as well as the role of mechanical circulatory support devices in general and Impella in particular,” he said, adding that Impella has been on the U.S. market since 2008, but with limited randomized clinical trial evidence in cardiogenic shock.

The study population of patient’s with CS is “only a piece of the puzzle,” Dr. Sweis said. “We know that there are sick hearts that aren’t in shock right now, but you’re going to do triple-vessel intervention and use atherectomy. Those patients would not do very well during the procedure itself and it may not even be offered to them if there weren’t support.”

Impella is not going away, Dr. Sweis said. “It provides an option that a patient wouldn’t otherwise have. This is really stressing to me that we need to get rid of that variability in the safety related to these devices.”

Dr. Amin disclosed financial relationships with Terumo and GE Healthcare. Dr. Dhruva had no financial relationships to disclose. The study was supported in part by a Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation grant from the Food and Drug Administration and the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

End ‘therapeutic nihilism’ in care of older diabetic patients, says expert

LOS ANGELES – In the opinion of Richard Pratley, MD, it’s time for diabetes treatment guidelines to evolve in light of accumulating data from cardiovascular outcome trials in type 2 diabetes.

“They have evolved for the general patient population, and this should apply to older individuals as well,” Dr. Pratley said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “My fear is, there is therapeutic nihilism, the idea that by the time someone is 75 years old, the horse is out of the barn and you’re not going to be able to impact outcomes with directed therapy. I don’t think that’s true. Our current treatment guidelines for the treatment of diabetes in older individuals remain focused on glycemic control. It’s not hyperglycemia that’s killing people; it’s heart disease and renal disease.”

According to data from the United Nations, about 12% of the global population is older than 60. By 2050, that number is expected to reach 20%, which will continue to drive an epidemic of diabetes in the near future. Dr. Pratley, medical director of AdventHealth Diabetes Institute in Orlando, pointed out that diabetes in older individuals is not a homogeneous condition. “There are many people in my clinic who had type 1 diabetes diagnosed as kids, but I also have patients who have adult-onset type 1 diabetes,” he said. “We also have type 2 patients who can be diagnosed in their 20s, 30s, or 40s, and there are people who are diagnosed in their 70s and 80s. Now we are learning that there are different subtypes of diabetes; so even type 2 diabetes is not a homogeneous condition. There are people who are more insulin resistant or have more of an insulin secretory defect, and there’s a special type of older-onset type 2 diabetes. When you consider all this in talking about diabetes treatments, about 30% of patients in the United States are diagnosed [when they are] over the age of 60, so this is an ongoing issue.”

Older adults with diabetes may have longstanding diabetes with associated microvascular and macrovascular complications, he continued, or they may have newly diagnosed diabetes with evidence of end organ complications at the time of presentation. Or, they may have newly diagnosed diabetes without evidence of complications. “Does this matter? It does,” Dr. Pratley said. “The things we worry about with all patients with diabetes are the microvascular complications, but I would argue that the macrovascular complications, particularly diabetic nephropathy, are things we should have a laser focus on, because they have high morbidity and mortality, especially in older individuals.”

There are more than 28 cardiovascular outcomes trials in patients with type 2 diabetes ongoing or completed, and involving eight classes of medications, with more than 200,000 planned participants, Dr. Pratley said. Of those participants, 90,000 are older than 65 years, and 30,000 are older than 75 years. “This is great,” he said. “Not only do these cardiovascular outcome studies give us a lot of information about the safety and efficacy of these drugs in the general population, we can now dig in to this specific patient population.” For example, in cardiovascular outcomes trials with dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, the mean age of patients was 65. About half of the patients were older than 65, and 10%-14% were older than 75.

Investigators in the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial examined age in one of their subgroup analyses (Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1145-53). In that study with saxagliptin, among people older than 65 who received the study drug, the hazard ratio for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was 0.92, compared with 1.15 for those younger than 65 (P value for interaction = .058). “So older people did great [on this drug],” Dr. Pratley said. “In fact, they had a bit of a decreased risk.” A similar association was seen in adults aged 75 years and older (HR, 1.01 in those younger than 75 years, vs. 0.95 in those aged 75 years and older; P value for interaction = .673). “This is telling us that saxagliptin is safe in the older population.”

In the EXAMINE trial, in which patients with type 2 diabetes who had had a recent acute coronary syndrome received either alogliptin or placebo, researchers conducted an analysis of patients older and younger than 65 (N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1327-35). They observed no significant interactions on the primary composite cardiovascular outcome in those younger than 65 (HR, 0.91) and those aged 65 and older (HR, 0.98).

Dr. Pratley noted that in cardiovascular outcome trials with sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, the mean age of patients was 64, and 48%-50% of them were older than 65. In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial of empagliflozin, the hazard ratio for the primary cardiovascular outcome was 1.04 in patients younger than 65 and 0.71 in those aged 65 and older (P = .01; N Engl J Med, 2015;373:2117-28). “That was a significant interaction,” he said. In addition, the hazard ratio for cardiovascular death was 0.72 in those younger than 65, and 0.54 in those aged 65 and older (P = .21). “There was not a significant interaction here, but clearly there was some trending in the older patient population,” Dr. Pratley said.

In the LEADER study of liraglutide in patients with diabetes, the hazard ratio for the primary composite cardiovascular outcome was 0.87 in the overall population, 0.78 in patients younger than 60, and 0.90 in those aged 60 and older (P = 0.27; N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-22). In a post hoc analysis that stratified LEADER patients into younger than 75 and 75 and older, the researchers observed a 31% reduction in the 75 and older population, compared with a 10% reduction in the younger population (P for interaction = .09; Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[6]:423-6). “This was driven largely by a decrease in nonfatal [myocardial infarction],” said Dr. Pratley, who was one of the study investigators. “But in patients who were 75 years and older, there was a 30% reduction in all-cause mortality in those treated with liraglutide, compared with 12% in those younger than 75 (P for interaction = .22). That interaction is not significant, but the theme here is that older populations do quite well.”

Based on such evidence, he said, In particular, SGLT2 inhibitors and certain GLP-1 receptor agonists may be associated with an additional benefit in older individuals with cardiovascular disease, “perhaps because they’re the ones at highest risk,” Dr. Pratley said. “But we need further studies to better identify those older individuals who may be at highest risk of adverse cardiovascular complications from diabetes and who might benefit from targeted therapies.”

Many questions remain unanswered in efforts to provide optimal care to older adults with diabetes. “One of the problems is being inclusive in the older patient population,” Dr. Pratley said. “We tried to do a study of frail older individuals looking at different treatments and policies. It was difficult to recruit frail older individuals, even though they routinely are treated with the drugs we study in healthier populations. We need to know how to enroll patients, and which investigators are going to do these trials. Who is going to support these trials? Pharma? The NIH?”

Then there’s the question of what appropriate outcomes are in older individuals. “I think we can agree that hemoglobin A1c is a surrogate of microvascular complications,” he said. “Do we need to be looking at outcomes like MACE, hospitalization for heart failure, death, progression of [chronic kidney disease], and perhaps cognitive function, physical function, sarcopenia, and quality of life?”

Dr. Pratley called for the development of a personalized approach to diabetes management that takes into account heterogeneity in disease pathogenesis, comorbidities, and patient preference.

“We need to change the focus to patient-important outcomes: dying, heart attack, strokes, and avoid therapeutic nihilism, which is still pervasive among many practitioners,” he said. “We also need to partner with primary care, because they take care of the majority of older individuals, and they need to understand how we’re evolving the goals of therapy. We need to educate them about the new guidelines and try to get them on board with some of the latest data that will help improve outcomes in our patients. We also need to understand the cost of diabetes and the cost effectiveness of interventions.”

He also recommends the development of a comprehensive evidence base for the use of drugs in older individuals. “I suggest pooled analyses within clinical development programs,” he said. “That’s been done for most development programs, but the phase 3 studies tend to enroll younger, healthier individuals. It would be good to do a meta-analysis across CVOTs [cardiovascular outcome trials] within different classes of medications.”

Dr. Pratley disclosed that all honoraria and fees he receives are directed to AdventHealth. These include serving on the advisory board or as consultant to AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Glytec, Janssen, Ligand, Lilly, Merck, Mundipharma, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. He also has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk, and has received research support from Lexicon, Ligand, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. He receives no direct or indirect compensation.

LOS ANGELES – In the opinion of Richard Pratley, MD, it’s time for diabetes treatment guidelines to evolve in light of accumulating data from cardiovascular outcome trials in type 2 diabetes.

“They have evolved for the general patient population, and this should apply to older individuals as well,” Dr. Pratley said at the World Congress on Insulin Resistance, Diabetes & Cardiovascular Disease. “My fear is, there is therapeutic nihilism, the idea that by the time someone is 75 years old, the horse is out of the barn and you’re not going to be able to impact outcomes with directed therapy. I don’t think that’s true. Our current treatment guidelines for the treatment of diabetes in older individuals remain focused on glycemic control. It’s not hyperglycemia that’s killing people; it’s heart disease and renal disease.”

According to data from the United Nations, about 12% of the global population is older than 60. By 2050, that number is expected to reach 20%, which will continue to drive an epidemic of diabetes in the near future. Dr. Pratley, medical director of AdventHealth Diabetes Institute in Orlando, pointed out that diabetes in older individuals is not a homogeneous condition. “There are many people in my clinic who had type 1 diabetes diagnosed as kids, but I also have patients who have adult-onset type 1 diabetes,” he said. “We also have type 2 patients who can be diagnosed in their 20s, 30s, or 40s, and there are people who are diagnosed in their 70s and 80s. Now we are learning that there are different subtypes of diabetes; so even type 2 diabetes is not a homogeneous condition. There are people who are more insulin resistant or have more of an insulin secretory defect, and there’s a special type of older-onset type 2 diabetes. When you consider all this in talking about diabetes treatments, about 30% of patients in the United States are diagnosed [when they are] over the age of 60, so this is an ongoing issue.”

Older adults with diabetes may have longstanding diabetes with associated microvascular and macrovascular complications, he continued, or they may have newly diagnosed diabetes with evidence of end organ complications at the time of presentation. Or, they may have newly diagnosed diabetes without evidence of complications. “Does this matter? It does,” Dr. Pratley said. “The things we worry about with all patients with diabetes are the microvascular complications, but I would argue that the macrovascular complications, particularly diabetic nephropathy, are things we should have a laser focus on, because they have high morbidity and mortality, especially in older individuals.”

There are more than 28 cardiovascular outcomes trials in patients with type 2 diabetes ongoing or completed, and involving eight classes of medications, with more than 200,000 planned participants, Dr. Pratley said. Of those participants, 90,000 are older than 65 years, and 30,000 are older than 75 years. “This is great,” he said. “Not only do these cardiovascular outcome studies give us a lot of information about the safety and efficacy of these drugs in the general population, we can now dig in to this specific patient population.” For example, in cardiovascular outcomes trials with dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, the mean age of patients was 65. About half of the patients were older than 65, and 10%-14% were older than 75.

Investigators in the SAVOR-TIMI 53 trial examined age in one of their subgroup analyses (Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1145-53). In that study with saxagliptin, among people older than 65 who received the study drug, the hazard ratio for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) was 0.92, compared with 1.15 for those younger than 65 (P value for interaction = .058). “So older people did great [on this drug],” Dr. Pratley said. “In fact, they had a bit of a decreased risk.” A similar association was seen in adults aged 75 years and older (HR, 1.01 in those younger than 75 years, vs. 0.95 in those aged 75 years and older; P value for interaction = .673). “This is telling us that saxagliptin is safe in the older population.”

In the EXAMINE trial, in which patients with type 2 diabetes who had had a recent acute coronary syndrome received either alogliptin or placebo, researchers conducted an analysis of patients older and younger than 65 (N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1327-35). They observed no significant interactions on the primary composite cardiovascular outcome in those younger than 65 (HR, 0.91) and those aged 65 and older (HR, 0.98).

Dr. Pratley noted that in cardiovascular outcome trials with sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, the mean age of patients was 64, and 48%-50% of them were older than 65. In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial of empagliflozin, the hazard ratio for the primary cardiovascular outcome was 1.04 in patients younger than 65 and 0.71 in those aged 65 and older (P = .01; N Engl J Med, 2015;373:2117-28). “That was a significant interaction,” he said. In addition, the hazard ratio for cardiovascular death was 0.72 in those younger than 65, and 0.54 in those aged 65 and older (P = .21). “There was not a significant interaction here, but clearly there was some trending in the older patient population,” Dr. Pratley said.

In the LEADER study of liraglutide in patients with diabetes, the hazard ratio for the primary composite cardiovascular outcome was 0.87 in the overall population, 0.78 in patients younger than 60, and 0.90 in those aged 60 and older (P = 0.27; N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-22). In a post hoc analysis that stratified LEADER patients into younger than 75 and 75 and older, the researchers observed a 31% reduction in the 75 and older population, compared with a 10% reduction in the younger population (P for interaction = .09; Ann Intern Med. 2019;170[6]:423-6). “This was driven largely by a decrease in nonfatal [myocardial infarction],” said Dr. Pratley, who was one of the study investigators. “But in patients who were 75 years and older, there was a 30% reduction in all-cause mortality in those treated with liraglutide, compared with 12% in those younger than 75 (P for interaction = .22). That interaction is not significant, but the theme here is that older populations do quite well.”

Based on such evidence, he said, In particular, SGLT2 inhibitors and certain GLP-1 receptor agonists may be associated with an additional benefit in older individuals with cardiovascular disease, “perhaps because they’re the ones at highest risk,” Dr. Pratley said. “But we need further studies to better identify those older individuals who may be at highest risk of adverse cardiovascular complications from diabetes and who might benefit from targeted therapies.”

Many questions remain unanswered in efforts to provide optimal care to older adults with diabetes. “One of the problems is being inclusive in the older patient population,” Dr. Pratley said. “We tried to do a study of frail older individuals looking at different treatments and policies. It was difficult to recruit frail older individuals, even though they routinely are treated with the drugs we study in healthier populations. We need to know how to enroll patients, and which investigators are going to do these trials. Who is going to support these trials? Pharma? The NIH?”

Then there’s the question of what appropriate outcomes are in older individuals. “I think we can agree that hemoglobin A1c is a surrogate of microvascular complications,” he said. “Do we need to be looking at outcomes like MACE, hospitalization for heart failure, death, progression of [chronic kidney disease], and perhaps cognitive function, physical function, sarcopenia, and quality of life?”

Dr. Pratley called for the development of a personalized approach to diabetes management that takes into account heterogeneity in disease pathogenesis, comorbidities, and patient preference.

“We need to change the focus to patient-important outcomes: dying, heart attack, strokes, and avoid therapeutic nihilism, which is still pervasive among many practitioners,” he said. “We also need to partner with primary care, because they take care of the majority of older individuals, and they need to understand how we’re evolving the goals of therapy. We need to educate them about the new guidelines and try to get them on board with some of the latest data that will help improve outcomes in our patients. We also need to understand the cost of diabetes and the cost effectiveness of interventions.”

He also recommends the development of a comprehensive evidence base for the use of drugs in older individuals. “I suggest pooled analyses within clinical development programs,” he said. “That’s been done for most development programs, but the phase 3 studies tend to enroll younger, healthier individuals. It would be good to do a meta-analysis across CVOTs [cardiovascular outcome trials] within different classes of medications.”

Dr. Pratley disclosed that all honoraria and fees he receives are directed to AdventHealth. These include serving on the advisory board or as consultant to AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Glytec, Janssen, Ligand, Lilly, Merck, Mundipharma, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. He also has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk, and has received research support from Lexicon, Ligand, Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. He receives no direct or indirect compensation.

LOS ANGELES – In the opinion of Richard Pratley, MD, it’s time for diabetes treatment guidelines to evolve in light of accumulating data from cardiovascular outcome trials in type 2 diabetes.