User login

TBI is an unrecognized risk factor for cardiovascular disease

(CVD). More severe TBI is associated with higher risk of CVD, new research shows.

Given the relatively young age of post-9/11–era veterans with TBI, there may be an increased burden of heart disease in the future as these veterans age and develop traditional risk factors for CVD, the investigators, led by Ian J. Stewart, MD, with Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Novel data

Since Sept. 11, 2001, 4.5 million people have served in the U.S. military, with their time in service defined by the long-running wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Estimates suggest that up to 20% of post-9/11 veterans sustained a TBI.

While some evidence suggests that TBI increases the risk of CVD, prior reports have focused mainly on cerebrovascular outcomes. Until now, the potential association of TBI with CVD has not been comprehensively examined in post-9/11–era veterans.

The retrospective cohort study included 1,559,928 predominantly male post-9/11 veterans, including 301,169 (19.3%) with a history of TBI and 1,258,759 (81%) with no TBI history.

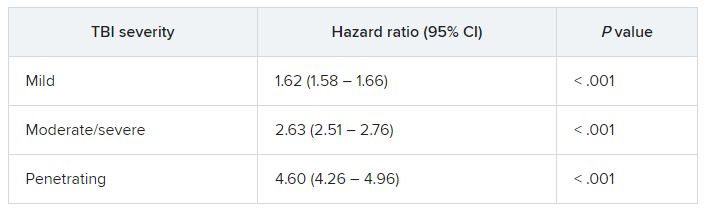

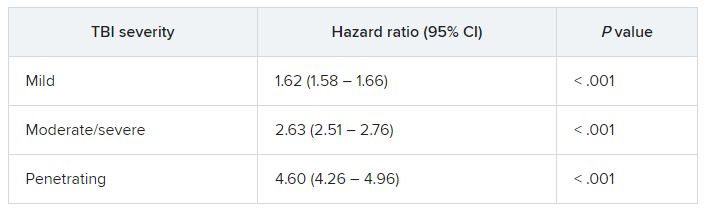

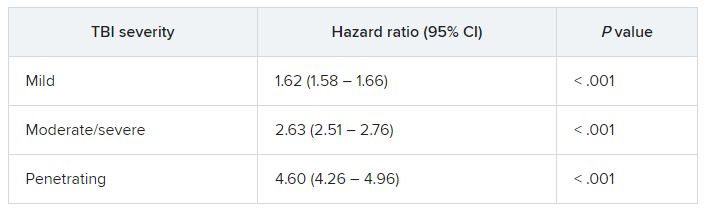

In fully adjusted models, compared with veterans with no TBI history, a history of mild, moderate/severe, or penetrating TBI was associated with increased risk of developing the composite CVD endpoint (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and CVD death).

TBIs of all severities were associated with the individual components of the composite outcome, except penetrating TBI and CVD death.

“The association of TBI with subsequent CVD was not attenuated in multivariable models, suggesting that TBI may be accounting for risk that is independent from the other variables,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote.

They noted that the risk was highest shortly after injury, but TBI remained significantly associated with CVD for years after the initial insult.

Why TBI may raise the risk of subsequent CVD remains unclear.

It’s possible that patients with TBI develop more traditional risk factors for CVD through time than do patients without TBI. A study in mice found that TBI led to increased rates of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

An additional mechanism may be disruption of autonomic regulation, which has been known to occur after TBI.

Another potential pathway is through mental health diagnoses, such as posttraumatic stress disorder; a large body of work has identified associations between PTSD and CVD, including among post-9/11 veterans.

Further work is needed to determine how this risk can be modified to improve outcomes for post-9/11–era veterans, the researchers write.

Unrecognized CVD risk factor?

Reached for comment, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher from Boston who wasn’t involved in the study, said the effects of TBI on heart health are “very underreported, and most clinicians would not make the link.”

“When the brain suffers a traumatic injury, it activates a cascade of neuro-inflammation that goes haywire in an attempt to protect further brain damage. Oftentimes, these inflammatory by-products leak into the body, especially in trauma, when the barriers are broken between brain and body, and can cause systemic body inflammation, which is well associated with heart disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

In addition, Dr. Lakhan said, “TBI itself localized to just the brain can negatively affect good health habits, leading to worsening heart health, too.”

“Research like this brings light where not much exists and underscores the importance of protecting our brains from physical trauma,” he said.

The study was supported by the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, endorsed by the Department of Defense through the Psychological Health/Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium, and by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Stewart and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(CVD). More severe TBI is associated with higher risk of CVD, new research shows.

Given the relatively young age of post-9/11–era veterans with TBI, there may be an increased burden of heart disease in the future as these veterans age and develop traditional risk factors for CVD, the investigators, led by Ian J. Stewart, MD, with Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Novel data

Since Sept. 11, 2001, 4.5 million people have served in the U.S. military, with their time in service defined by the long-running wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Estimates suggest that up to 20% of post-9/11 veterans sustained a TBI.

While some evidence suggests that TBI increases the risk of CVD, prior reports have focused mainly on cerebrovascular outcomes. Until now, the potential association of TBI with CVD has not been comprehensively examined in post-9/11–era veterans.

The retrospective cohort study included 1,559,928 predominantly male post-9/11 veterans, including 301,169 (19.3%) with a history of TBI and 1,258,759 (81%) with no TBI history.

In fully adjusted models, compared with veterans with no TBI history, a history of mild, moderate/severe, or penetrating TBI was associated with increased risk of developing the composite CVD endpoint (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and CVD death).

TBIs of all severities were associated with the individual components of the composite outcome, except penetrating TBI and CVD death.

“The association of TBI with subsequent CVD was not attenuated in multivariable models, suggesting that TBI may be accounting for risk that is independent from the other variables,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote.

They noted that the risk was highest shortly after injury, but TBI remained significantly associated with CVD for years after the initial insult.

Why TBI may raise the risk of subsequent CVD remains unclear.

It’s possible that patients with TBI develop more traditional risk factors for CVD through time than do patients without TBI. A study in mice found that TBI led to increased rates of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

An additional mechanism may be disruption of autonomic regulation, which has been known to occur after TBI.

Another potential pathway is through mental health diagnoses, such as posttraumatic stress disorder; a large body of work has identified associations between PTSD and CVD, including among post-9/11 veterans.

Further work is needed to determine how this risk can be modified to improve outcomes for post-9/11–era veterans, the researchers write.

Unrecognized CVD risk factor?

Reached for comment, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher from Boston who wasn’t involved in the study, said the effects of TBI on heart health are “very underreported, and most clinicians would not make the link.”

“When the brain suffers a traumatic injury, it activates a cascade of neuro-inflammation that goes haywire in an attempt to protect further brain damage. Oftentimes, these inflammatory by-products leak into the body, especially in trauma, when the barriers are broken between brain and body, and can cause systemic body inflammation, which is well associated with heart disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

In addition, Dr. Lakhan said, “TBI itself localized to just the brain can negatively affect good health habits, leading to worsening heart health, too.”

“Research like this brings light where not much exists and underscores the importance of protecting our brains from physical trauma,” he said.

The study was supported by the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, endorsed by the Department of Defense through the Psychological Health/Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium, and by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Stewart and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

(CVD). More severe TBI is associated with higher risk of CVD, new research shows.

Given the relatively young age of post-9/11–era veterans with TBI, there may be an increased burden of heart disease in the future as these veterans age and develop traditional risk factors for CVD, the investigators, led by Ian J. Stewart, MD, with Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md., wrote.

The study was published online in JAMA Neurology.

Novel data

Since Sept. 11, 2001, 4.5 million people have served in the U.S. military, with their time in service defined by the long-running wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Estimates suggest that up to 20% of post-9/11 veterans sustained a TBI.

While some evidence suggests that TBI increases the risk of CVD, prior reports have focused mainly on cerebrovascular outcomes. Until now, the potential association of TBI with CVD has not been comprehensively examined in post-9/11–era veterans.

The retrospective cohort study included 1,559,928 predominantly male post-9/11 veterans, including 301,169 (19.3%) with a history of TBI and 1,258,759 (81%) with no TBI history.

In fully adjusted models, compared with veterans with no TBI history, a history of mild, moderate/severe, or penetrating TBI was associated with increased risk of developing the composite CVD endpoint (coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and CVD death).

TBIs of all severities were associated with the individual components of the composite outcome, except penetrating TBI and CVD death.

“The association of TBI with subsequent CVD was not attenuated in multivariable models, suggesting that TBI may be accounting for risk that is independent from the other variables,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote.

They noted that the risk was highest shortly after injury, but TBI remained significantly associated with CVD for years after the initial insult.

Why TBI may raise the risk of subsequent CVD remains unclear.

It’s possible that patients with TBI develop more traditional risk factors for CVD through time than do patients without TBI. A study in mice found that TBI led to increased rates of atherosclerosis, the researchers said.

An additional mechanism may be disruption of autonomic regulation, which has been known to occur after TBI.

Another potential pathway is through mental health diagnoses, such as posttraumatic stress disorder; a large body of work has identified associations between PTSD and CVD, including among post-9/11 veterans.

Further work is needed to determine how this risk can be modified to improve outcomes for post-9/11–era veterans, the researchers write.

Unrecognized CVD risk factor?

Reached for comment, Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher from Boston who wasn’t involved in the study, said the effects of TBI on heart health are “very underreported, and most clinicians would not make the link.”

“When the brain suffers a traumatic injury, it activates a cascade of neuro-inflammation that goes haywire in an attempt to protect further brain damage. Oftentimes, these inflammatory by-products leak into the body, especially in trauma, when the barriers are broken between brain and body, and can cause systemic body inflammation, which is well associated with heart disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

In addition, Dr. Lakhan said, “TBI itself localized to just the brain can negatively affect good health habits, leading to worsening heart health, too.”

“Research like this brings light where not much exists and underscores the importance of protecting our brains from physical trauma,” he said.

The study was supported by the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, endorsed by the Department of Defense through the Psychological Health/Traumatic Brain Injury Research Program Long-Term Impact of Military-Relevant Brain Injury Consortium, and by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Stewart and Dr. Lakhan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Your poop may hold the secret to long life

Lots of things can disrupt your gut health over the years. A high-sugar diet, stress, antibiotics – all are linked to bad changes in the gut microbiome, the microbes that live in your intestinal tract. And this can raise the risk of diseases.

It could be possible, scientists say, by having people take a sample of their own stool when they are young to be put back into their colons when they are older.

While the science to back this up isn’t quite there yet, some researchers are saying we shouldn’t wait. They are calling on existing stool banks to let people start banking their stool now, so it’s there for them to use if the science becomes available.

But how would that work?

First, you’d go to a stool bank and provide a fresh sample of your poop, which would be screened for diseases, washed, processed, and deposited into a long-term storage facility.

Then, down the road, if you get a condition such as inflammatory bowel disease, heart disease, or type 2 diabetes – or if you have a procedure that wipes out your microbiome, like a course of antibiotics or chemotherapy – doctors could use your preserved stool to “re-colonize” your gut, restoring it to its earlier, healthier state, said Scott Weiss, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and a coauthor of a recent paper on the topic. They would do that using fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT.

Timing is everything. You’d want a sample from when you’re healthy – say, between the ages of 18 and 35, or before a chronic condition is likely, said Dr. Weiss. But if you’re still healthy into your late 30s, 40s, or even 50s, providing a sample then could still benefit you later in life.

If we could pull off a banking system like this, it could have the potential to treat autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease – or even reverse the effects of aging. How can we make this happen?

Stool banks of today

While stool banks do exist today, the samples inside are destined not for the original donors but rather for sick patients hoping to treat an illness. Using FMT, doctors transfer the fecal material to the patient’s colon, restoring helpful gut microbiota.

Some research shows FMT may help treat inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. Animal studies suggest it could help treat obesity, lengthen lifespan, and reverse some effects of aging, such as age-related decline in brain function. Other clinical trials are looking into its potential as a cancer treatment, said Dr. Weiss.

But outside the lab, FMT is mainly used for one purpose: to treat Clostridioides difficile infection. It works even better than antibiotics, research shows.

But first you need to find a healthy donor, and that’s harder than you might think.

Finding healthy stool samples

Banking our bodily substances is nothing new. Blood banks, for example, are common throughout the United States, and cord blood banking – preserving blood from a baby’s umbilical cord to aid possible future medical needs of the child – is becoming more popular. Sperm donors are highly sought after, and doctors regularly transplant kidneys and bone marrow to patients in need.

So why are we so particular about poop?

Part of the reason may be because feces (like blood, for that matter) can harbor disease – which is why it’s so important to find healthy stool donors. Problem is, this can be surprisingly hard to do.

To donate fecal matter, people must go through a rigorous screening process, said Majdi Osman, MD, chief medical officer for OpenBiome, a nonprofit microbiome research organization.

Until recently, OpenBiome operated a stool donation program, though it has since shifted its focus to research. Potential donors were screened for diseases and mental health conditions, pathogens, and antibiotic resistance. The pass rate was less than 3%.

“We take a very cautious approach because the association between diseases and the microbiome is still being understood,” Dr. Osman said.

FMT also carries risks – though so far, they seem mild. Side effects include mild diarrhea, nausea, belly pain, and fatigue. (The reason? Even the healthiest donor stool may not mix perfectly with your own.)

That’s where the idea of using your own stool comes in, said Yang-Yu Liu, PhD, a Harvard researcher who studies the microbiome and the lead author of the paper mentioned above. It’s not just more appealing but may also be a better “match” for your body.

Should you bank your stool?

While the researchers say we have reason to be optimistic about the future, it’s important to remember that many challenges remain. FMT is early in development, and there’s a lot about the microbiome we still don’t know.

There’s no guarantee, for example, that restoring a person’s microbiome to its formerly disease-free state will keep diseases at bay forever, said Dr. Weiss. If your genes raise your odds of having Crohn’s, for instance, it’s possible the disease could come back.

We also don’t know how long stool samples can be preserved, said Dr. Liu. Stool banks currently store fecal matter for 1 or 2 years, not decades. To protect the proteins and DNA structures for that long, samples would likely need to be stashed at the liquid nitrogen storage temperature of –196° C. (Currently, samples are stored at about –80° C.) Even then, testing would be needed to confirm if the fragile microorganisms in the stool can survive.

This raises another question: Who’s going to regulate all this?

The FDA regulates the use of FMT as a drug for the treatment of C. diff, but as Dr. Liu pointed out, many gastroenterologists consider the gut microbiota an organ. In that case, human fecal matter could be regulated the same way blood, bone, or even egg cells are.

Cord blood banking may be a helpful model, Dr. Liu said.

“We don’t have to start from scratch.”

Then there’s the question of cost. Cord blood banks could be a point of reference for that too, the researchers say. They charge about $1,500 to $2,820 for the first collection and processing, plus a yearly storage fee of $185 to $370.

Despite the unknowns, one thing is for sure: The interest in fecal banking is real – and growing. At least one microbiome firm, Cordlife Group Limited, based in Singapore, announced that it has started to allow people to bank their stool for future use.

“More people should talk about it and think about it,” said Dr. Liu.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Lots of things can disrupt your gut health over the years. A high-sugar diet, stress, antibiotics – all are linked to bad changes in the gut microbiome, the microbes that live in your intestinal tract. And this can raise the risk of diseases.

It could be possible, scientists say, by having people take a sample of their own stool when they are young to be put back into their colons when they are older.

While the science to back this up isn’t quite there yet, some researchers are saying we shouldn’t wait. They are calling on existing stool banks to let people start banking their stool now, so it’s there for them to use if the science becomes available.

But how would that work?

First, you’d go to a stool bank and provide a fresh sample of your poop, which would be screened for diseases, washed, processed, and deposited into a long-term storage facility.

Then, down the road, if you get a condition such as inflammatory bowel disease, heart disease, or type 2 diabetes – or if you have a procedure that wipes out your microbiome, like a course of antibiotics or chemotherapy – doctors could use your preserved stool to “re-colonize” your gut, restoring it to its earlier, healthier state, said Scott Weiss, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and a coauthor of a recent paper on the topic. They would do that using fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT.

Timing is everything. You’d want a sample from when you’re healthy – say, between the ages of 18 and 35, or before a chronic condition is likely, said Dr. Weiss. But if you’re still healthy into your late 30s, 40s, or even 50s, providing a sample then could still benefit you later in life.

If we could pull off a banking system like this, it could have the potential to treat autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease – or even reverse the effects of aging. How can we make this happen?

Stool banks of today

While stool banks do exist today, the samples inside are destined not for the original donors but rather for sick patients hoping to treat an illness. Using FMT, doctors transfer the fecal material to the patient’s colon, restoring helpful gut microbiota.

Some research shows FMT may help treat inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. Animal studies suggest it could help treat obesity, lengthen lifespan, and reverse some effects of aging, such as age-related decline in brain function. Other clinical trials are looking into its potential as a cancer treatment, said Dr. Weiss.

But outside the lab, FMT is mainly used for one purpose: to treat Clostridioides difficile infection. It works even better than antibiotics, research shows.

But first you need to find a healthy donor, and that’s harder than you might think.

Finding healthy stool samples

Banking our bodily substances is nothing new. Blood banks, for example, are common throughout the United States, and cord blood banking – preserving blood from a baby’s umbilical cord to aid possible future medical needs of the child – is becoming more popular. Sperm donors are highly sought after, and doctors regularly transplant kidneys and bone marrow to patients in need.

So why are we so particular about poop?

Part of the reason may be because feces (like blood, for that matter) can harbor disease – which is why it’s so important to find healthy stool donors. Problem is, this can be surprisingly hard to do.

To donate fecal matter, people must go through a rigorous screening process, said Majdi Osman, MD, chief medical officer for OpenBiome, a nonprofit microbiome research organization.

Until recently, OpenBiome operated a stool donation program, though it has since shifted its focus to research. Potential donors were screened for diseases and mental health conditions, pathogens, and antibiotic resistance. The pass rate was less than 3%.

“We take a very cautious approach because the association between diseases and the microbiome is still being understood,” Dr. Osman said.

FMT also carries risks – though so far, they seem mild. Side effects include mild diarrhea, nausea, belly pain, and fatigue. (The reason? Even the healthiest donor stool may not mix perfectly with your own.)

That’s where the idea of using your own stool comes in, said Yang-Yu Liu, PhD, a Harvard researcher who studies the microbiome and the lead author of the paper mentioned above. It’s not just more appealing but may also be a better “match” for your body.

Should you bank your stool?

While the researchers say we have reason to be optimistic about the future, it’s important to remember that many challenges remain. FMT is early in development, and there’s a lot about the microbiome we still don’t know.

There’s no guarantee, for example, that restoring a person’s microbiome to its formerly disease-free state will keep diseases at bay forever, said Dr. Weiss. If your genes raise your odds of having Crohn’s, for instance, it’s possible the disease could come back.

We also don’t know how long stool samples can be preserved, said Dr. Liu. Stool banks currently store fecal matter for 1 or 2 years, not decades. To protect the proteins and DNA structures for that long, samples would likely need to be stashed at the liquid nitrogen storage temperature of –196° C. (Currently, samples are stored at about –80° C.) Even then, testing would be needed to confirm if the fragile microorganisms in the stool can survive.

This raises another question: Who’s going to regulate all this?

The FDA regulates the use of FMT as a drug for the treatment of C. diff, but as Dr. Liu pointed out, many gastroenterologists consider the gut microbiota an organ. In that case, human fecal matter could be regulated the same way blood, bone, or even egg cells are.

Cord blood banking may be a helpful model, Dr. Liu said.

“We don’t have to start from scratch.”

Then there’s the question of cost. Cord blood banks could be a point of reference for that too, the researchers say. They charge about $1,500 to $2,820 for the first collection and processing, plus a yearly storage fee of $185 to $370.

Despite the unknowns, one thing is for sure: The interest in fecal banking is real – and growing. At least one microbiome firm, Cordlife Group Limited, based in Singapore, announced that it has started to allow people to bank their stool for future use.

“More people should talk about it and think about it,” said Dr. Liu.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Lots of things can disrupt your gut health over the years. A high-sugar diet, stress, antibiotics – all are linked to bad changes in the gut microbiome, the microbes that live in your intestinal tract. And this can raise the risk of diseases.

It could be possible, scientists say, by having people take a sample of their own stool when they are young to be put back into their colons when they are older.

While the science to back this up isn’t quite there yet, some researchers are saying we shouldn’t wait. They are calling on existing stool banks to let people start banking their stool now, so it’s there for them to use if the science becomes available.

But how would that work?

First, you’d go to a stool bank and provide a fresh sample of your poop, which would be screened for diseases, washed, processed, and deposited into a long-term storage facility.

Then, down the road, if you get a condition such as inflammatory bowel disease, heart disease, or type 2 diabetes – or if you have a procedure that wipes out your microbiome, like a course of antibiotics or chemotherapy – doctors could use your preserved stool to “re-colonize” your gut, restoring it to its earlier, healthier state, said Scott Weiss, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and a coauthor of a recent paper on the topic. They would do that using fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT.

Timing is everything. You’d want a sample from when you’re healthy – say, between the ages of 18 and 35, or before a chronic condition is likely, said Dr. Weiss. But if you’re still healthy into your late 30s, 40s, or even 50s, providing a sample then could still benefit you later in life.

If we could pull off a banking system like this, it could have the potential to treat autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, obesity, and heart disease – or even reverse the effects of aging. How can we make this happen?

Stool banks of today

While stool banks do exist today, the samples inside are destined not for the original donors but rather for sick patients hoping to treat an illness. Using FMT, doctors transfer the fecal material to the patient’s colon, restoring helpful gut microbiota.

Some research shows FMT may help treat inflammatory bowel diseases, such as Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. Animal studies suggest it could help treat obesity, lengthen lifespan, and reverse some effects of aging, such as age-related decline in brain function. Other clinical trials are looking into its potential as a cancer treatment, said Dr. Weiss.

But outside the lab, FMT is mainly used for one purpose: to treat Clostridioides difficile infection. It works even better than antibiotics, research shows.

But first you need to find a healthy donor, and that’s harder than you might think.

Finding healthy stool samples

Banking our bodily substances is nothing new. Blood banks, for example, are common throughout the United States, and cord blood banking – preserving blood from a baby’s umbilical cord to aid possible future medical needs of the child – is becoming more popular. Sperm donors are highly sought after, and doctors regularly transplant kidneys and bone marrow to patients in need.

So why are we so particular about poop?

Part of the reason may be because feces (like blood, for that matter) can harbor disease – which is why it’s so important to find healthy stool donors. Problem is, this can be surprisingly hard to do.

To donate fecal matter, people must go through a rigorous screening process, said Majdi Osman, MD, chief medical officer for OpenBiome, a nonprofit microbiome research organization.

Until recently, OpenBiome operated a stool donation program, though it has since shifted its focus to research. Potential donors were screened for diseases and mental health conditions, pathogens, and antibiotic resistance. The pass rate was less than 3%.

“We take a very cautious approach because the association between diseases and the microbiome is still being understood,” Dr. Osman said.

FMT also carries risks – though so far, they seem mild. Side effects include mild diarrhea, nausea, belly pain, and fatigue. (The reason? Even the healthiest donor stool may not mix perfectly with your own.)

That’s where the idea of using your own stool comes in, said Yang-Yu Liu, PhD, a Harvard researcher who studies the microbiome and the lead author of the paper mentioned above. It’s not just more appealing but may also be a better “match” for your body.

Should you bank your stool?

While the researchers say we have reason to be optimistic about the future, it’s important to remember that many challenges remain. FMT is early in development, and there’s a lot about the microbiome we still don’t know.

There’s no guarantee, for example, that restoring a person’s microbiome to its formerly disease-free state will keep diseases at bay forever, said Dr. Weiss. If your genes raise your odds of having Crohn’s, for instance, it’s possible the disease could come back.

We also don’t know how long stool samples can be preserved, said Dr. Liu. Stool banks currently store fecal matter for 1 or 2 years, not decades. To protect the proteins and DNA structures for that long, samples would likely need to be stashed at the liquid nitrogen storage temperature of –196° C. (Currently, samples are stored at about –80° C.) Even then, testing would be needed to confirm if the fragile microorganisms in the stool can survive.

This raises another question: Who’s going to regulate all this?

The FDA regulates the use of FMT as a drug for the treatment of C. diff, but as Dr. Liu pointed out, many gastroenterologists consider the gut microbiota an organ. In that case, human fecal matter could be regulated the same way blood, bone, or even egg cells are.

Cord blood banking may be a helpful model, Dr. Liu said.

“We don’t have to start from scratch.”

Then there’s the question of cost. Cord blood banks could be a point of reference for that too, the researchers say. They charge about $1,500 to $2,820 for the first collection and processing, plus a yearly storage fee of $185 to $370.

Despite the unknowns, one thing is for sure: The interest in fecal banking is real – and growing. At least one microbiome firm, Cordlife Group Limited, based in Singapore, announced that it has started to allow people to bank their stool for future use.

“More people should talk about it and think about it,” said Dr. Liu.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Heparin pretreatment may safely open arteries before STEMI cath

, suggests a large registry study.

An open infarct-related artery (IRA) at angiography on cath-lab arrival presents STEMI patients an opportunity for earlier reperfusion and a chance, in theory at least, for smaller infarcts and maybe improved clinical outcomes.

In the new analysis, which covers more than 40,000 patients with STEMI in Sweden, the 38% who received heparin before cath-lab arrival were 11% less likely to show IRA occlusion at angiography prior to direct percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). They also showed a 13% lower 30-day mortality compared with patients who were started on heparin in the cath lab. Importantly, their risk of major bleeding in the hospital did not increase.

The “early reperfusion” associated with IRA patency at angiography “could have long-term benefit due to smaller infarct size,” potentially explaining the observed 30-day survival gain in the pretreatment group, Oskar Love Emilsson, Lund (Sweden) University, said in an interview.

Mr. Emilsson, a third-year medical student, reported the analysis at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, and is lead author on its same-day publication in the journal EuroIntervention.

He mentioned a few cautions in interpreting the study, which is based primarily on data from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). It included several sensitivity analyses that continued to back pretreatment heparin as a significant predictor of an unoccluded IRA but didn’t consistently support the 30-day mortality benefit seen in the primary analysis.

And, although the pretreatment group overall didn’t have more major bleeds, the risk did go up significantly for those older than 75 or those who weighed less than 60 kg (132 pounds) or underwent catheterization with an access route other than the radial artery. Extra caution should be exercised in such patients who receive heparin before cath-lab arrival for PCI, Mr. Emilsson observed.

“Our results suggest that heparin pretreatment might be a good option to improve patency of infarct related arteries in STEMI,” and potentially clinical outcomes, he said. “However, a definite answer would require a randomized controlled trial.”

Meanwhile, the current study may be the largest yet to look at clinical outcomes after pretreatment with unfractionated heparin before PCI for acute STEMI, the report states. There have been some observational studies, subanalyses of STEMI trials, and even a few limited randomized trials – including the HEAP trial published in 2000 – to weigh in on the subject. Some have supported the strategy, others have not.

“With rapid door-to-balloon times in STEMI, it can be challenging to show a significant difference between a prehospital heparin approach and heparin given in the lab,” observed Sunil V. Rao, MD, NYU Langone Health System, New York, who is not connected with the current study.

Many EDs in the United States have “a STEMI protocol that calls for an IV bolus of heparin. It would be tougher in the U.S. to give it in the ambulance but again, it’s not clear how much advantage that would really provide,” he told this news organization.

Support from randomized trials would be needed before the practice could be formally recommended. “The SCAAR registries have set the standard for how registries should be conducted,” Dr. Rao said. “This is a very well done observational study, but it is observational.”

The priority for STEMI patients, he added, “really should be to get them to the lab as fast as possible. If the ED protocol includes heparin before the cath lab, that’s great, but I don’t think we should delay getting these patients to the lab to accommodate pre–cath-lab heparin.”

The current analysis covered 41,631 patients with STEMI from 2008 through to 2016, of whom 38% were pretreated with heparin in an ambulance or the ED. The remaining 62% initiated heparin in the cath lab.

About one-third of the group had an open IRA at angiography. The adjusted risk ratio (RR) for IRA occlusion at angiography for patients pretreated vs. not pretreated with heparin was 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-0.90).

The corresponding RR for death within 30 days was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.77-0.99), and for major in-hospital bleeding it was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.86-1.18).

The analysis was adjusted for other medications received before cath-lab arrival, especially a long list of antiplatelets and non-heparin antithrombins. That strengthens the case for heparin pretreatment as an independent predictor of an open IRA at initial angiography, Mr. Emilsson said.

Comparisons of propensity-score–matched subgroups of the total cohort, conducted separately for the IRA-occlusion endpoint and the endpoints of 30-day mortality and major bleeding, produced similar results.

Some observational data suggest that antiplatelet pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor may promote IRA patency on angiography after cath lab arrival, Dr. Rao observed. “This indicates that there probably is a role of earlier antithrombotic therapy in STEMI patients, but the randomized trials have not shown a consistent benefit,” he said, referring in particular to the ATLANTIC trial.

Mr. Emilsson and Dr. Rao disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggests a large registry study.

An open infarct-related artery (IRA) at angiography on cath-lab arrival presents STEMI patients an opportunity for earlier reperfusion and a chance, in theory at least, for smaller infarcts and maybe improved clinical outcomes.

In the new analysis, which covers more than 40,000 patients with STEMI in Sweden, the 38% who received heparin before cath-lab arrival were 11% less likely to show IRA occlusion at angiography prior to direct percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). They also showed a 13% lower 30-day mortality compared with patients who were started on heparin in the cath lab. Importantly, their risk of major bleeding in the hospital did not increase.

The “early reperfusion” associated with IRA patency at angiography “could have long-term benefit due to smaller infarct size,” potentially explaining the observed 30-day survival gain in the pretreatment group, Oskar Love Emilsson, Lund (Sweden) University, said in an interview.

Mr. Emilsson, a third-year medical student, reported the analysis at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, and is lead author on its same-day publication in the journal EuroIntervention.

He mentioned a few cautions in interpreting the study, which is based primarily on data from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). It included several sensitivity analyses that continued to back pretreatment heparin as a significant predictor of an unoccluded IRA but didn’t consistently support the 30-day mortality benefit seen in the primary analysis.

And, although the pretreatment group overall didn’t have more major bleeds, the risk did go up significantly for those older than 75 or those who weighed less than 60 kg (132 pounds) or underwent catheterization with an access route other than the radial artery. Extra caution should be exercised in such patients who receive heparin before cath-lab arrival for PCI, Mr. Emilsson observed.

“Our results suggest that heparin pretreatment might be a good option to improve patency of infarct related arteries in STEMI,” and potentially clinical outcomes, he said. “However, a definite answer would require a randomized controlled trial.”

Meanwhile, the current study may be the largest yet to look at clinical outcomes after pretreatment with unfractionated heparin before PCI for acute STEMI, the report states. There have been some observational studies, subanalyses of STEMI trials, and even a few limited randomized trials – including the HEAP trial published in 2000 – to weigh in on the subject. Some have supported the strategy, others have not.

“With rapid door-to-balloon times in STEMI, it can be challenging to show a significant difference between a prehospital heparin approach and heparin given in the lab,” observed Sunil V. Rao, MD, NYU Langone Health System, New York, who is not connected with the current study.

Many EDs in the United States have “a STEMI protocol that calls for an IV bolus of heparin. It would be tougher in the U.S. to give it in the ambulance but again, it’s not clear how much advantage that would really provide,” he told this news organization.

Support from randomized trials would be needed before the practice could be formally recommended. “The SCAAR registries have set the standard for how registries should be conducted,” Dr. Rao said. “This is a very well done observational study, but it is observational.”

The priority for STEMI patients, he added, “really should be to get them to the lab as fast as possible. If the ED protocol includes heparin before the cath lab, that’s great, but I don’t think we should delay getting these patients to the lab to accommodate pre–cath-lab heparin.”

The current analysis covered 41,631 patients with STEMI from 2008 through to 2016, of whom 38% were pretreated with heparin in an ambulance or the ED. The remaining 62% initiated heparin in the cath lab.

About one-third of the group had an open IRA at angiography. The adjusted risk ratio (RR) for IRA occlusion at angiography for patients pretreated vs. not pretreated with heparin was 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-0.90).

The corresponding RR for death within 30 days was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.77-0.99), and for major in-hospital bleeding it was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.86-1.18).

The analysis was adjusted for other medications received before cath-lab arrival, especially a long list of antiplatelets and non-heparin antithrombins. That strengthens the case for heparin pretreatment as an independent predictor of an open IRA at initial angiography, Mr. Emilsson said.

Comparisons of propensity-score–matched subgroups of the total cohort, conducted separately for the IRA-occlusion endpoint and the endpoints of 30-day mortality and major bleeding, produced similar results.

Some observational data suggest that antiplatelet pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor may promote IRA patency on angiography after cath lab arrival, Dr. Rao observed. “This indicates that there probably is a role of earlier antithrombotic therapy in STEMI patients, but the randomized trials have not shown a consistent benefit,” he said, referring in particular to the ATLANTIC trial.

Mr. Emilsson and Dr. Rao disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, suggests a large registry study.

An open infarct-related artery (IRA) at angiography on cath-lab arrival presents STEMI patients an opportunity for earlier reperfusion and a chance, in theory at least, for smaller infarcts and maybe improved clinical outcomes.

In the new analysis, which covers more than 40,000 patients with STEMI in Sweden, the 38% who received heparin before cath-lab arrival were 11% less likely to show IRA occlusion at angiography prior to direct percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). They also showed a 13% lower 30-day mortality compared with patients who were started on heparin in the cath lab. Importantly, their risk of major bleeding in the hospital did not increase.

The “early reperfusion” associated with IRA patency at angiography “could have long-term benefit due to smaller infarct size,” potentially explaining the observed 30-day survival gain in the pretreatment group, Oskar Love Emilsson, Lund (Sweden) University, said in an interview.

Mr. Emilsson, a third-year medical student, reported the analysis at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, and is lead author on its same-day publication in the journal EuroIntervention.

He mentioned a few cautions in interpreting the study, which is based primarily on data from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). It included several sensitivity analyses that continued to back pretreatment heparin as a significant predictor of an unoccluded IRA but didn’t consistently support the 30-day mortality benefit seen in the primary analysis.

And, although the pretreatment group overall didn’t have more major bleeds, the risk did go up significantly for those older than 75 or those who weighed less than 60 kg (132 pounds) or underwent catheterization with an access route other than the radial artery. Extra caution should be exercised in such patients who receive heparin before cath-lab arrival for PCI, Mr. Emilsson observed.

“Our results suggest that heparin pretreatment might be a good option to improve patency of infarct related arteries in STEMI,” and potentially clinical outcomes, he said. “However, a definite answer would require a randomized controlled trial.”

Meanwhile, the current study may be the largest yet to look at clinical outcomes after pretreatment with unfractionated heparin before PCI for acute STEMI, the report states. There have been some observational studies, subanalyses of STEMI trials, and even a few limited randomized trials – including the HEAP trial published in 2000 – to weigh in on the subject. Some have supported the strategy, others have not.

“With rapid door-to-balloon times in STEMI, it can be challenging to show a significant difference between a prehospital heparin approach and heparin given in the lab,” observed Sunil V. Rao, MD, NYU Langone Health System, New York, who is not connected with the current study.

Many EDs in the United States have “a STEMI protocol that calls for an IV bolus of heparin. It would be tougher in the U.S. to give it in the ambulance but again, it’s not clear how much advantage that would really provide,” he told this news organization.

Support from randomized trials would be needed before the practice could be formally recommended. “The SCAAR registries have set the standard for how registries should be conducted,” Dr. Rao said. “This is a very well done observational study, but it is observational.”

The priority for STEMI patients, he added, “really should be to get them to the lab as fast as possible. If the ED protocol includes heparin before the cath lab, that’s great, but I don’t think we should delay getting these patients to the lab to accommodate pre–cath-lab heparin.”

The current analysis covered 41,631 patients with STEMI from 2008 through to 2016, of whom 38% were pretreated with heparin in an ambulance or the ED. The remaining 62% initiated heparin in the cath lab.

About one-third of the group had an open IRA at angiography. The adjusted risk ratio (RR) for IRA occlusion at angiography for patients pretreated vs. not pretreated with heparin was 0.89 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-0.90).

The corresponding RR for death within 30 days was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.77-0.99), and for major in-hospital bleeding it was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.86-1.18).

The analysis was adjusted for other medications received before cath-lab arrival, especially a long list of antiplatelets and non-heparin antithrombins. That strengthens the case for heparin pretreatment as an independent predictor of an open IRA at initial angiography, Mr. Emilsson said.

Comparisons of propensity-score–matched subgroups of the total cohort, conducted separately for the IRA-occlusion endpoint and the endpoints of 30-day mortality and major bleeding, produced similar results.

Some observational data suggest that antiplatelet pretreatment with a P2Y12 inhibitor may promote IRA patency on angiography after cath lab arrival, Dr. Rao observed. “This indicates that there probably is a role of earlier antithrombotic therapy in STEMI patients, but the randomized trials have not shown a consistent benefit,” he said, referring in particular to the ATLANTIC trial.

Mr. Emilsson and Dr. Rao disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2022

PARADISE-MI results obscured as post hoc analysis finds flaws

A post hoc analysis of the PARADISE-MI trial, although not intended to alter the conclusions generated by the published data, suggests that clinically relevant benefits were obscured, providing the basis for recommending different analyses for future studies that are more suited to capture the most clinically significant endpoints.

“What these data show us is that we need clinical trial designs moving towards more pragmatic information that better reflect clinical practice,” reported Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, director of the Academic Research Organization at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil.

The reevaluation of the PARADISE-MI data, presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Barcelona, was based on a win ratio analysis and on the inclusion of investigator-reported endpoints, not just adjudicated events. Both appear to reveal clinically meaningful benefits not reflected in the published study, according to Dr. Berwanger.

In PARADISE-MI, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, more than 5,500 patients were randomized to the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan or the ACE inhibitor ramipril after a myocardial infarction. A reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), pulmonary congestion, or both were required for enrollment.

For the primary composite outcomes of death from cardiovascular (CV) causes or incident heart failure, the ARNI had a 10% numerical advantage, but it did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio [HR], 0.90; P = .17).

“PARADISE-MI was a neutral trial. This post hoc analysis will not change that result,” Dr. Berwanger emphasized. However, the post hoc analysis does provide a basis for exploring why conventional trial designs might not be providing answers that are relevant and helpful for clinical practice.

New analysis provides positive trial result

When the data from PARADISE-MI are reevaluated in a hierarchical win ratio analysis with CV death serving as the most severe and important outcome, the principal conclusion changes. Whether events are reevaluated in this format by the clinical events committee (CEC) or by investigators, there is a greater number of total wins than total losses for the ARNI. Combined, sacubitril/valsartan was associated with a win ratio of 1.17 (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.33; P = 0.015) over ramipril.

Using a sports analogy, Dr. Berwanger explained that the win ratio analysis divides the total number of wins to the total number of losses to provide a much more clinically relevant approach to keeping score. It also used a hierarchical analysis so that the most serious and important events are considered first.

In addition to CV death, this analysis included first hospitalization for heart failure and first outpatient heart failure events. CEC-defined events and events reported by investigators were evaluated separately.

The ARNI had more wins than losses in every category for all outcomes, whether CEC adjudicated or investigator reported, but most of this benefit was generated by the endpoint of CEC-adjudicated CV deaths. This accounted for 36.9% of all events (investigator-documented CV death accounted for 0.7%). This is important because PARADISE-MI, like many standard trials, was conducted on a time-to-primary event basis.

“In this type of analysis, the first event is what counts. Usually time-to-first-event analyses are dominated by nonfatal events,” Dr. Berwanger explained. He believes that placing more weight on the most serious events results in an emphasis on what outcomes are of greatest clinical interest.

In addition, Dr. Berwanger argued that it is important to consider investigator-reported events, not just CEC-adjudicated events. While adjudicated events improve the rigor of the data, Dr. Berwanger suggested it omits outcomes with which clinicians are most concerned.

Investigator, adjudicated outcomes differ

Again, using PARADISE-MI as an example, he reevaluated the primary outcome based on investigator reports. When investigator-reported events are included, the number of events increased in both the ARNI (443 vs. 338) and ramipril (516 vs. 373) arms, but the advantage of the ARNI over the ACE inhibitors now reached statistical significance (HR, 0.85; P = .01).

“The data suggest that maybe we should find definitions for adjudication that are closer to clinical judgment in the real world and clinical practice,” Dr. Berwanger said.

One possible explanation for the neutral result in PARADISE-MI is that benefit of an ARNI over an ACE inhibitor would only be expected in those at risk for progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and it is likely that a substantial proportion of patients enrolled in this trial recovered, according to Johann Bauersachs, MD, PhD, professor and head of cardiology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

“You cannot predict which patients with reduced LV function following an MI will go on to chronic remodeling and which will recover,” said Dr. Bauersachs, who was an ESC-invited discussant of Dr. Berwanger’s post hoc analysis.

He agreed that Dr. Berwanger has raised several important issues in standard trial design that might have prevented PARADISE-MI from showing a benefit from an ARNI, but he pointed out that there are other potential issues, such as the low use of mineralocorticoid antagonists in PARADISE-MI, that may have skewed results.

However, he agreed generally with the premise that there is a need for trial design likely to generate more clinically useful information.

“We have now seen the win-ratio approach used in several studies,” said Dr. Bauersachs, citing in particular the EMPULSE trial presented at the 2022 meeting of the American College of Cardiology. “It is a very useful tool, and I think we will be seeing it used more in the future.”

However, he indicated that the issues raised by Dr. Berwanger are not necessarily easily resolved. Dr. Bauersachs endorsed the effort to consider trial designs that generate data that are more immediately clinically applicable but suggested that different types of designs may be required for different types of clinical questions.

Dr. Berwanger reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Servier, and Novartis, which provided funding for the PARADISE-MI trial. Dr. Bauersachs reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior, Corvia, CVRx, Novartis, Pfizer, Vifor, and Zoll.

A post hoc analysis of the PARADISE-MI trial, although not intended to alter the conclusions generated by the published data, suggests that clinically relevant benefits were obscured, providing the basis for recommending different analyses for future studies that are more suited to capture the most clinically significant endpoints.

“What these data show us is that we need clinical trial designs moving towards more pragmatic information that better reflect clinical practice,” reported Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, director of the Academic Research Organization at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil.

The reevaluation of the PARADISE-MI data, presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Barcelona, was based on a win ratio analysis and on the inclusion of investigator-reported endpoints, not just adjudicated events. Both appear to reveal clinically meaningful benefits not reflected in the published study, according to Dr. Berwanger.

In PARADISE-MI, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, more than 5,500 patients were randomized to the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan or the ACE inhibitor ramipril after a myocardial infarction. A reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), pulmonary congestion, or both were required for enrollment.

For the primary composite outcomes of death from cardiovascular (CV) causes or incident heart failure, the ARNI had a 10% numerical advantage, but it did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio [HR], 0.90; P = .17).

“PARADISE-MI was a neutral trial. This post hoc analysis will not change that result,” Dr. Berwanger emphasized. However, the post hoc analysis does provide a basis for exploring why conventional trial designs might not be providing answers that are relevant and helpful for clinical practice.

New analysis provides positive trial result

When the data from PARADISE-MI are reevaluated in a hierarchical win ratio analysis with CV death serving as the most severe and important outcome, the principal conclusion changes. Whether events are reevaluated in this format by the clinical events committee (CEC) or by investigators, there is a greater number of total wins than total losses for the ARNI. Combined, sacubitril/valsartan was associated with a win ratio of 1.17 (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.33; P = 0.015) over ramipril.

Using a sports analogy, Dr. Berwanger explained that the win ratio analysis divides the total number of wins to the total number of losses to provide a much more clinically relevant approach to keeping score. It also used a hierarchical analysis so that the most serious and important events are considered first.

In addition to CV death, this analysis included first hospitalization for heart failure and first outpatient heart failure events. CEC-defined events and events reported by investigators were evaluated separately.

The ARNI had more wins than losses in every category for all outcomes, whether CEC adjudicated or investigator reported, but most of this benefit was generated by the endpoint of CEC-adjudicated CV deaths. This accounted for 36.9% of all events (investigator-documented CV death accounted for 0.7%). This is important because PARADISE-MI, like many standard trials, was conducted on a time-to-primary event basis.

“In this type of analysis, the first event is what counts. Usually time-to-first-event analyses are dominated by nonfatal events,” Dr. Berwanger explained. He believes that placing more weight on the most serious events results in an emphasis on what outcomes are of greatest clinical interest.

In addition, Dr. Berwanger argued that it is important to consider investigator-reported events, not just CEC-adjudicated events. While adjudicated events improve the rigor of the data, Dr. Berwanger suggested it omits outcomes with which clinicians are most concerned.

Investigator, adjudicated outcomes differ

Again, using PARADISE-MI as an example, he reevaluated the primary outcome based on investigator reports. When investigator-reported events are included, the number of events increased in both the ARNI (443 vs. 338) and ramipril (516 vs. 373) arms, but the advantage of the ARNI over the ACE inhibitors now reached statistical significance (HR, 0.85; P = .01).

“The data suggest that maybe we should find definitions for adjudication that are closer to clinical judgment in the real world and clinical practice,” Dr. Berwanger said.

One possible explanation for the neutral result in PARADISE-MI is that benefit of an ARNI over an ACE inhibitor would only be expected in those at risk for progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and it is likely that a substantial proportion of patients enrolled in this trial recovered, according to Johann Bauersachs, MD, PhD, professor and head of cardiology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

“You cannot predict which patients with reduced LV function following an MI will go on to chronic remodeling and which will recover,” said Dr. Bauersachs, who was an ESC-invited discussant of Dr. Berwanger’s post hoc analysis.

He agreed that Dr. Berwanger has raised several important issues in standard trial design that might have prevented PARADISE-MI from showing a benefit from an ARNI, but he pointed out that there are other potential issues, such as the low use of mineralocorticoid antagonists in PARADISE-MI, that may have skewed results.

However, he agreed generally with the premise that there is a need for trial design likely to generate more clinically useful information.

“We have now seen the win-ratio approach used in several studies,” said Dr. Bauersachs, citing in particular the EMPULSE trial presented at the 2022 meeting of the American College of Cardiology. “It is a very useful tool, and I think we will be seeing it used more in the future.”

However, he indicated that the issues raised by Dr. Berwanger are not necessarily easily resolved. Dr. Bauersachs endorsed the effort to consider trial designs that generate data that are more immediately clinically applicable but suggested that different types of designs may be required for different types of clinical questions.

Dr. Berwanger reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Servier, and Novartis, which provided funding for the PARADISE-MI trial. Dr. Bauersachs reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior, Corvia, CVRx, Novartis, Pfizer, Vifor, and Zoll.

A post hoc analysis of the PARADISE-MI trial, although not intended to alter the conclusions generated by the published data, suggests that clinically relevant benefits were obscured, providing the basis for recommending different analyses for future studies that are more suited to capture the most clinically significant endpoints.

“What these data show us is that we need clinical trial designs moving towards more pragmatic information that better reflect clinical practice,” reported Otavio Berwanger, MD, PhD, director of the Academic Research Organization at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil.

The reevaluation of the PARADISE-MI data, presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Barcelona, was based on a win ratio analysis and on the inclusion of investigator-reported endpoints, not just adjudicated events. Both appear to reveal clinically meaningful benefits not reflected in the published study, according to Dr. Berwanger.

In PARADISE-MI, which was published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year, more than 5,500 patients were randomized to the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan or the ACE inhibitor ramipril after a myocardial infarction. A reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), pulmonary congestion, or both were required for enrollment.

For the primary composite outcomes of death from cardiovascular (CV) causes or incident heart failure, the ARNI had a 10% numerical advantage, but it did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio [HR], 0.90; P = .17).

“PARADISE-MI was a neutral trial. This post hoc analysis will not change that result,” Dr. Berwanger emphasized. However, the post hoc analysis does provide a basis for exploring why conventional trial designs might not be providing answers that are relevant and helpful for clinical practice.

New analysis provides positive trial result

When the data from PARADISE-MI are reevaluated in a hierarchical win ratio analysis with CV death serving as the most severe and important outcome, the principal conclusion changes. Whether events are reevaluated in this format by the clinical events committee (CEC) or by investigators, there is a greater number of total wins than total losses for the ARNI. Combined, sacubitril/valsartan was associated with a win ratio of 1.17 (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.33; P = 0.015) over ramipril.

Using a sports analogy, Dr. Berwanger explained that the win ratio analysis divides the total number of wins to the total number of losses to provide a much more clinically relevant approach to keeping score. It also used a hierarchical analysis so that the most serious and important events are considered first.

In addition to CV death, this analysis included first hospitalization for heart failure and first outpatient heart failure events. CEC-defined events and events reported by investigators were evaluated separately.

The ARNI had more wins than losses in every category for all outcomes, whether CEC adjudicated or investigator reported, but most of this benefit was generated by the endpoint of CEC-adjudicated CV deaths. This accounted for 36.9% of all events (investigator-documented CV death accounted for 0.7%). This is important because PARADISE-MI, like many standard trials, was conducted on a time-to-primary event basis.

“In this type of analysis, the first event is what counts. Usually time-to-first-event analyses are dominated by nonfatal events,” Dr. Berwanger explained. He believes that placing more weight on the most serious events results in an emphasis on what outcomes are of greatest clinical interest.

In addition, Dr. Berwanger argued that it is important to consider investigator-reported events, not just CEC-adjudicated events. While adjudicated events improve the rigor of the data, Dr. Berwanger suggested it omits outcomes with which clinicians are most concerned.

Investigator, adjudicated outcomes differ

Again, using PARADISE-MI as an example, he reevaluated the primary outcome based on investigator reports. When investigator-reported events are included, the number of events increased in both the ARNI (443 vs. 338) and ramipril (516 vs. 373) arms, but the advantage of the ARNI over the ACE inhibitors now reached statistical significance (HR, 0.85; P = .01).

“The data suggest that maybe we should find definitions for adjudication that are closer to clinical judgment in the real world and clinical practice,” Dr. Berwanger said.

One possible explanation for the neutral result in PARADISE-MI is that benefit of an ARNI over an ACE inhibitor would only be expected in those at risk for progressive left ventricular dysfunction, and it is likely that a substantial proportion of patients enrolled in this trial recovered, according to Johann Bauersachs, MD, PhD, professor and head of cardiology at Hannover (Germany) Medical School.

“You cannot predict which patients with reduced LV function following an MI will go on to chronic remodeling and which will recover,” said Dr. Bauersachs, who was an ESC-invited discussant of Dr. Berwanger’s post hoc analysis.

He agreed that Dr. Berwanger has raised several important issues in standard trial design that might have prevented PARADISE-MI from showing a benefit from an ARNI, but he pointed out that there are other potential issues, such as the low use of mineralocorticoid antagonists in PARADISE-MI, that may have skewed results.

However, he agreed generally with the premise that there is a need for trial design likely to generate more clinically useful information.

“We have now seen the win-ratio approach used in several studies,” said Dr. Bauersachs, citing in particular the EMPULSE trial presented at the 2022 meeting of the American College of Cardiology. “It is a very useful tool, and I think we will be seeing it used more in the future.”

However, he indicated that the issues raised by Dr. Berwanger are not necessarily easily resolved. Dr. Bauersachs endorsed the effort to consider trial designs that generate data that are more immediately clinically applicable but suggested that different types of designs may be required for different types of clinical questions.

Dr. Berwanger reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Servier, and Novartis, which provided funding for the PARADISE-MI trial. Dr. Bauersachs reports financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardior, Corvia, CVRx, Novartis, Pfizer, Vifor, and Zoll.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2022

Myocardial infarction in women younger than 50: Lessons to learn

Young women (under 50) are increasingly having heart attacks without doctors really knowing why. This is where the Young Women Presenting Acute Myocardial Infarction in France (WAMIF) study comes in, the results of which were presented in an e-poster at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology by Stéphane Manzo-Silberman, MD, Institute of Cardiology, Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris. The results (yet to be published) fight several of the preconceived ideas on the topic, Dr. Manzo-Silberman commented in an interview.

Significantly higher hospital death rates in women

“Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death in women, killing seven times more than breast cancer,” notes Dr. Manzo-Silberman. The hospital death rate is significantly higher in women and, despite going down, is significantly higher than in men (more than double), particularly in women under 50. What’s more, in addition to the typical risk factors, women present specific risk factors related to hormone changes, high-risk inflammatory profiles, and thrombophilia.”

The WAMIF study was designed to determine the clinical, biological, and morphological features linked to hospital mortality after 12 months in women under 50. The prospective, observational study included all women in this age range from 30 sites in France between May 2017 and June 2019.

90% with retrosternal chest pain

The age of the 314 women enrolled was 44.9 years on average. Nearly two-thirds (192) presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and the other 122 without. In terms of symptoms, 91.6% of these women presented with typical chest pain, and 59.7% had related symptoms.

“With more than 90% having retrosternal pain, the idea that myocardial infarction presents with atypical symptoms in women has been widely challenged, despite the fact that more than half present with related symptoms and it isn’t known in which order these symptoms occur, Dr. Manzo-Silberman said in an interview. But what we can say is that if at any point a young woman mentions chest pain, even when occurring as part of several other symptoms, MI must be deemed a possibility until it has been ruled out.”

The risk profile revealed that 75.5% were smokers, 35% had a family history of heart disease, 33% had pregnancy complications, and 55% had recently experienced a stressful situation. The analysis also showed that cannabis use and oral contraception were primary risk factors in women younger than 35.

“With regard to risk factors, when designing this study we expected that lots of these young women would have largely atypical autoimmune conditions, with high levels of inflammation. We looked for everything, but this was not actually the case. Instead, we found very many women to have classic risk factors; three-quarters were smokers, a modifiable risk factor, which can largely be prevented. The other aspect concerns contraception, and it’s why I insist that gynecologists must be involved insofar as they must inform their patients how to manage their risk factors and tweak their contraception.”

Coronary angiography findings showed that only 1% received a normal result, 29.3% had vessel damage, and 14.6% had aortic dissection. “We were surprised again here because we expected that with young women we would see lots of heart attacks without obstruction, [in other words] normal coronary arteries, atypical forms of MI,” commented Dr. Manzo-Silberman. “In fact, most presented with atheroma, often obstructive lesions, or even triple-vessel disease, in nearly a third of the cohort. So that’s another misconception dispelled – we can’t just think that because a woman is young, nothing will be found. Coronary catheterization should be considered, and the diagnostic process should be completed in full.”

After 1 year, there had been two cancer-related deaths and 25 patients had undergone several angioplasty procedures. Nevertheless, 90.4% had not experienced any type of CV event, and 72% had not even had any symptoms.

“The final surprise was prognosis,” he said. “Previous studies, especially some authored by Viola Vaccarino, MD, PhD, showed an excess hospital rate in women and we had expected this to be the case here, but no hospital deaths were recorded. However, not far off 10% of women attended (at least once) the emergency department in the year following for recurrent chest pain which was not ischemic – ECG normal, troponin normal – so something was missing in their education as a patient.”

“So, there are improvements to be made in terms of secondary prevention, follow-up, and in the education of these young female patients who have experienced the major event that is a myocardial infarction,” concluded Dr. Manzo-Silberman.

This content was originally published on Medscape French edition.

Young women (under 50) are increasingly having heart attacks without doctors really knowing why. This is where the Young Women Presenting Acute Myocardial Infarction in France (WAMIF) study comes in, the results of which were presented in an e-poster at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology by Stéphane Manzo-Silberman, MD, Institute of Cardiology, Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris. The results (yet to be published) fight several of the preconceived ideas on the topic, Dr. Manzo-Silberman commented in an interview.

Significantly higher hospital death rates in women

“Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death in women, killing seven times more than breast cancer,” notes Dr. Manzo-Silberman. The hospital death rate is significantly higher in women and, despite going down, is significantly higher than in men (more than double), particularly in women under 50. What’s more, in addition to the typical risk factors, women present specific risk factors related to hormone changes, high-risk inflammatory profiles, and thrombophilia.”

The WAMIF study was designed to determine the clinical, biological, and morphological features linked to hospital mortality after 12 months in women under 50. The prospective, observational study included all women in this age range from 30 sites in France between May 2017 and June 2019.

90% with retrosternal chest pain

The age of the 314 women enrolled was 44.9 years on average. Nearly two-thirds (192) presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and the other 122 without. In terms of symptoms, 91.6% of these women presented with typical chest pain, and 59.7% had related symptoms.

“With more than 90% having retrosternal pain, the idea that myocardial infarction presents with atypical symptoms in women has been widely challenged, despite the fact that more than half present with related symptoms and it isn’t known in which order these symptoms occur, Dr. Manzo-Silberman said in an interview. But what we can say is that if at any point a young woman mentions chest pain, even when occurring as part of several other symptoms, MI must be deemed a possibility until it has been ruled out.”

The risk profile revealed that 75.5% were smokers, 35% had a family history of heart disease, 33% had pregnancy complications, and 55% had recently experienced a stressful situation. The analysis also showed that cannabis use and oral contraception were primary risk factors in women younger than 35.

“With regard to risk factors, when designing this study we expected that lots of these young women would have largely atypical autoimmune conditions, with high levels of inflammation. We looked for everything, but this was not actually the case. Instead, we found very many women to have classic risk factors; three-quarters were smokers, a modifiable risk factor, which can largely be prevented. The other aspect concerns contraception, and it’s why I insist that gynecologists must be involved insofar as they must inform their patients how to manage their risk factors and tweak their contraception.”

Coronary angiography findings showed that only 1% received a normal result, 29.3% had vessel damage, and 14.6% had aortic dissection. “We were surprised again here because we expected that with young women we would see lots of heart attacks without obstruction, [in other words] normal coronary arteries, atypical forms of MI,” commented Dr. Manzo-Silberman. “In fact, most presented with atheroma, often obstructive lesions, or even triple-vessel disease, in nearly a third of the cohort. So that’s another misconception dispelled – we can’t just think that because a woman is young, nothing will be found. Coronary catheterization should be considered, and the diagnostic process should be completed in full.”

After 1 year, there had been two cancer-related deaths and 25 patients had undergone several angioplasty procedures. Nevertheless, 90.4% had not experienced any type of CV event, and 72% had not even had any symptoms.

“The final surprise was prognosis,” he said. “Previous studies, especially some authored by Viola Vaccarino, MD, PhD, showed an excess hospital rate in women and we had expected this to be the case here, but no hospital deaths were recorded. However, not far off 10% of women attended (at least once) the emergency department in the year following for recurrent chest pain which was not ischemic – ECG normal, troponin normal – so something was missing in their education as a patient.”

“So, there are improvements to be made in terms of secondary prevention, follow-up, and in the education of these young female patients who have experienced the major event that is a myocardial infarction,” concluded Dr. Manzo-Silberman.

This content was originally published on Medscape French edition.

Young women (under 50) are increasingly having heart attacks without doctors really knowing why. This is where the Young Women Presenting Acute Myocardial Infarction in France (WAMIF) study comes in, the results of which were presented in an e-poster at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology by Stéphane Manzo-Silberman, MD, Institute of Cardiology, Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris. The results (yet to be published) fight several of the preconceived ideas on the topic, Dr. Manzo-Silberman commented in an interview.

Significantly higher hospital death rates in women