User login

Study suggests narrow excision margins safe in early melanoma resection

Current U.S., European, and Australian or melanoma-specific mortality (MSM), results of a retrospective study suggest.

Among 1,179 patients with stage T1a melanomas near the face, scalp, external genitalia, or other critical areas, the weighted 10-year local recurrence rate for patients who underwent resection with 10-mm margins was 5.7%, compared with 6.7% for those who had resections with 5-mm margins, a nonsignificant difference.

Weighted 10-year melanoma-specific mortality was 1.8% for patients treated with wide margins, vs. 4.2% for those treated with narrow margins, also a nonsignificant difference. Patients treated with narrow margins did have significantly fewer reconstructive surgeries than patients treated with wide margins, reported Andrea Maurichi, MD, and colleagues at the National Cancer Institute of Italy in Milan.

“Because this association was found in melanomas of the head and neck, acral, and genital sites, there is no plausible reason why it could not be extrapolated to other locations. The findings also support the need for prospective randomized clinical trials to definitively answer the important question about appropriate excision margins for T1a melanoma,” they wrote in the study, published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The authors also found, however, that Breslow thickness greater than 0.4 mm and mitotic rate greater than 1/mm2 were associated with worse MSM, and that acral lentiginous melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, and increasing Breslow thickness were associated with a higher incidence of local recurrence.

A melanoma expert who was not involved in the study said that despite these findings, wider margins are always preferable.

“There is always a conversation around these general [critical] areas, but as a rule we try to get larger margins,” said Ryan J. Sullivan, MD, of Mass General Cancer Center in Boston.

In an interview, Dr. Sullivan said that the finding about lower frequency of reconstructive procedures in the narrow margins groups may be more of a concern for younger patients than for the elderly.

Study design

The investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive patients aged 18 or older at the National Cancer Institute of Milan who were diagnosed with T1a cutaneous melanoma close to critical areas from 2001 through 2020.

Patients with primary cutaneous melanoma of the head and face areas with functional or cosmetic considerations, acral areas (plantar, palmar, digital and interdigital areas), external genitalia, or periumbilical and perineal areas were eligible for inclusion.

The cohort comprised 1,179 patients with a median age of 50 and equal sex distribution. Of these patients, 626 (53%) had a wide excision, of whom 434 had a linear repair, and 192 had a flap of graft reconstruction. The remaining 553 patients had narrow excisions, 491 with linear repair, and 62 with flap or graft reconstruction.

Analyses were adjusted to account for imbalances between the surgical groups.

The study was supported by the nonprofit foundation Emme Rouge. The authors and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Current U.S., European, and Australian or melanoma-specific mortality (MSM), results of a retrospective study suggest.

Among 1,179 patients with stage T1a melanomas near the face, scalp, external genitalia, or other critical areas, the weighted 10-year local recurrence rate for patients who underwent resection with 10-mm margins was 5.7%, compared with 6.7% for those who had resections with 5-mm margins, a nonsignificant difference.

Weighted 10-year melanoma-specific mortality was 1.8% for patients treated with wide margins, vs. 4.2% for those treated with narrow margins, also a nonsignificant difference. Patients treated with narrow margins did have significantly fewer reconstructive surgeries than patients treated with wide margins, reported Andrea Maurichi, MD, and colleagues at the National Cancer Institute of Italy in Milan.

“Because this association was found in melanomas of the head and neck, acral, and genital sites, there is no plausible reason why it could not be extrapolated to other locations. The findings also support the need for prospective randomized clinical trials to definitively answer the important question about appropriate excision margins for T1a melanoma,” they wrote in the study, published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The authors also found, however, that Breslow thickness greater than 0.4 mm and mitotic rate greater than 1/mm2 were associated with worse MSM, and that acral lentiginous melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, and increasing Breslow thickness were associated with a higher incidence of local recurrence.

A melanoma expert who was not involved in the study said that despite these findings, wider margins are always preferable.

“There is always a conversation around these general [critical] areas, but as a rule we try to get larger margins,” said Ryan J. Sullivan, MD, of Mass General Cancer Center in Boston.

In an interview, Dr. Sullivan said that the finding about lower frequency of reconstructive procedures in the narrow margins groups may be more of a concern for younger patients than for the elderly.

Study design

The investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive patients aged 18 or older at the National Cancer Institute of Milan who were diagnosed with T1a cutaneous melanoma close to critical areas from 2001 through 2020.

Patients with primary cutaneous melanoma of the head and face areas with functional or cosmetic considerations, acral areas (plantar, palmar, digital and interdigital areas), external genitalia, or periumbilical and perineal areas were eligible for inclusion.

The cohort comprised 1,179 patients with a median age of 50 and equal sex distribution. Of these patients, 626 (53%) had a wide excision, of whom 434 had a linear repair, and 192 had a flap of graft reconstruction. The remaining 553 patients had narrow excisions, 491 with linear repair, and 62 with flap or graft reconstruction.

Analyses were adjusted to account for imbalances between the surgical groups.

The study was supported by the nonprofit foundation Emme Rouge. The authors and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Current U.S., European, and Australian or melanoma-specific mortality (MSM), results of a retrospective study suggest.

Among 1,179 patients with stage T1a melanomas near the face, scalp, external genitalia, or other critical areas, the weighted 10-year local recurrence rate for patients who underwent resection with 10-mm margins was 5.7%, compared with 6.7% for those who had resections with 5-mm margins, a nonsignificant difference.

Weighted 10-year melanoma-specific mortality was 1.8% for patients treated with wide margins, vs. 4.2% for those treated with narrow margins, also a nonsignificant difference. Patients treated with narrow margins did have significantly fewer reconstructive surgeries than patients treated with wide margins, reported Andrea Maurichi, MD, and colleagues at the National Cancer Institute of Italy in Milan.

“Because this association was found in melanomas of the head and neck, acral, and genital sites, there is no plausible reason why it could not be extrapolated to other locations. The findings also support the need for prospective randomized clinical trials to definitively answer the important question about appropriate excision margins for T1a melanoma,” they wrote in the study, published online in JAMA Dermatology.

The authors also found, however, that Breslow thickness greater than 0.4 mm and mitotic rate greater than 1/mm2 were associated with worse MSM, and that acral lentiginous melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, and increasing Breslow thickness were associated with a higher incidence of local recurrence.

A melanoma expert who was not involved in the study said that despite these findings, wider margins are always preferable.

“There is always a conversation around these general [critical] areas, but as a rule we try to get larger margins,” said Ryan J. Sullivan, MD, of Mass General Cancer Center in Boston.

In an interview, Dr. Sullivan said that the finding about lower frequency of reconstructive procedures in the narrow margins groups may be more of a concern for younger patients than for the elderly.

Study design

The investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of consecutive patients aged 18 or older at the National Cancer Institute of Milan who were diagnosed with T1a cutaneous melanoma close to critical areas from 2001 through 2020.

Patients with primary cutaneous melanoma of the head and face areas with functional or cosmetic considerations, acral areas (plantar, palmar, digital and interdigital areas), external genitalia, or periumbilical and perineal areas were eligible for inclusion.

The cohort comprised 1,179 patients with a median age of 50 and equal sex distribution. Of these patients, 626 (53%) had a wide excision, of whom 434 had a linear repair, and 192 had a flap of graft reconstruction. The remaining 553 patients had narrow excisions, 491 with linear repair, and 62 with flap or graft reconstruction.

Analyses were adjusted to account for imbalances between the surgical groups.

The study was supported by the nonprofit foundation Emme Rouge. The authors and Dr. Sullivan reported having no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

What happens to melanocytic nevi during laser hair removal?

PHOENIX – , while common histologic changes include mild atypia and thermal damage, according to results from a systematic review of literature on the topic. To date, no severe cases of severe dysplasia or melanoma have been reported.

“That’s reassuring,” study author Ahuva Cices, MD, said in an interview at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, where she presented the results during an abstract session. “But, with that in mind, we want to avoid treating nevi with laser hair removal to avoid changes that could be concerning. We also recommend baseline skin exams so we know what we’re looking at before we start treating with lasers, and any changes can be recognized from that baseline status. It’s important to keep an eye out for changes and always be evaluating.”

In December of 2022, Dr. Cices, chief dermatology resident at Mount Sinai Health System, New York, searched PubMed for articles that evaluated changes in melanocytic nevi after laser hair removal procedures. She used the search terms “nevi laser hair removal,” “nevi diode,” “nevi long pulse alexandrite,” “nevi long pulse neodymium doped yttrium aluminum garnet,” and “melanoma laser hair removal,” and limited the analysis to English language patient-based reports that discussed incidental treatment of melanocytic nevi while undergoing hair removal with a laser.

Reports excluded from the analysis were those that focused on changes following hair removal with nonlaser devices such as intense pulsed light (IPL), those evaluating nonmelanocytic nevi such as Becker’s nevus or nevus of Ota, and those evaluating the intentional ablation or removal of melanocytic lesions.

The search yielded 10 relevant studies for systematic review: seven case reports or series and three observational trials, two of which were prospective and one retrospective.

The results of the review, according to Dr. Cices, revealed that clinical and dermoscopic changes were noted to present as early as 15 days after treatment and persist to the maximum follow up time, at 3 years. Commonly reported changes included regression, decreased size, laser-induced asymmetry, bleaching, darkening, and altered pattern on dermoscopy. Histologic changes included mild atypia, thermal damage, scar formation, and regression.

“Although some of the clinical and dermoscopic alterations may be concerning for malignancy, to our knowledge, there are no documented cases of malignant transformation of nevi following treatment with laser hair removal,” she wrote in the abstract.

Dr. Cices acknowledged certain limitations of the systematic review, including the low number of relevant reports and their generally small sample size, many of which were limited to single cases.

Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford, who was asked to comment on the review, characterized the findings as important because laser hair removal is such a commonly performed procedure.

While the study is limited by the small number of studies on the subject matter, “it brings up an important discussion,” Dr. Ibrahimi said in an interview. “Generally speaking, we know that most hair removal lasers do indeed target melanin pigment and can be absorbed by melanocytes. While the wavelengths used for LHR [laser hair removal] will not result in DNA damage or cause mutations that can lead to melanoma, they can sometimes alter the appearance of pigmented lesions and that may change the dermatologist’s ability to monitor them for atypia,” he noted.

“For that reason, I would recommend all patients see a dermatologist for evaluation of their nevi prior to any treatments and they consider very carefully where they get their laser treatments. If they have any atypical pigmented lesions, then that information should be disclosed with the person performing the laser hair removal procedure particularly if there are lesions that are being specifically monitored.”

Dr. Cices reported having no disclosures. Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Accure Acne, AbbVie, Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

PHOENIX – , while common histologic changes include mild atypia and thermal damage, according to results from a systematic review of literature on the topic. To date, no severe cases of severe dysplasia or melanoma have been reported.

“That’s reassuring,” study author Ahuva Cices, MD, said in an interview at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, where she presented the results during an abstract session. “But, with that in mind, we want to avoid treating nevi with laser hair removal to avoid changes that could be concerning. We also recommend baseline skin exams so we know what we’re looking at before we start treating with lasers, and any changes can be recognized from that baseline status. It’s important to keep an eye out for changes and always be evaluating.”

In December of 2022, Dr. Cices, chief dermatology resident at Mount Sinai Health System, New York, searched PubMed for articles that evaluated changes in melanocytic nevi after laser hair removal procedures. She used the search terms “nevi laser hair removal,” “nevi diode,” “nevi long pulse alexandrite,” “nevi long pulse neodymium doped yttrium aluminum garnet,” and “melanoma laser hair removal,” and limited the analysis to English language patient-based reports that discussed incidental treatment of melanocytic nevi while undergoing hair removal with a laser.

Reports excluded from the analysis were those that focused on changes following hair removal with nonlaser devices such as intense pulsed light (IPL), those evaluating nonmelanocytic nevi such as Becker’s nevus or nevus of Ota, and those evaluating the intentional ablation or removal of melanocytic lesions.

The search yielded 10 relevant studies for systematic review: seven case reports or series and three observational trials, two of which were prospective and one retrospective.

The results of the review, according to Dr. Cices, revealed that clinical and dermoscopic changes were noted to present as early as 15 days after treatment and persist to the maximum follow up time, at 3 years. Commonly reported changes included regression, decreased size, laser-induced asymmetry, bleaching, darkening, and altered pattern on dermoscopy. Histologic changes included mild atypia, thermal damage, scar formation, and regression.

“Although some of the clinical and dermoscopic alterations may be concerning for malignancy, to our knowledge, there are no documented cases of malignant transformation of nevi following treatment with laser hair removal,” she wrote in the abstract.

Dr. Cices acknowledged certain limitations of the systematic review, including the low number of relevant reports and their generally small sample size, many of which were limited to single cases.

Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford, who was asked to comment on the review, characterized the findings as important because laser hair removal is such a commonly performed procedure.

While the study is limited by the small number of studies on the subject matter, “it brings up an important discussion,” Dr. Ibrahimi said in an interview. “Generally speaking, we know that most hair removal lasers do indeed target melanin pigment and can be absorbed by melanocytes. While the wavelengths used for LHR [laser hair removal] will not result in DNA damage or cause mutations that can lead to melanoma, they can sometimes alter the appearance of pigmented lesions and that may change the dermatologist’s ability to monitor them for atypia,” he noted.

“For that reason, I would recommend all patients see a dermatologist for evaluation of their nevi prior to any treatments and they consider very carefully where they get their laser treatments. If they have any atypical pigmented lesions, then that information should be disclosed with the person performing the laser hair removal procedure particularly if there are lesions that are being specifically monitored.”

Dr. Cices reported having no disclosures. Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Accure Acne, AbbVie, Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

PHOENIX – , while common histologic changes include mild atypia and thermal damage, according to results from a systematic review of literature on the topic. To date, no severe cases of severe dysplasia or melanoma have been reported.

“That’s reassuring,” study author Ahuva Cices, MD, said in an interview at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, where she presented the results during an abstract session. “But, with that in mind, we want to avoid treating nevi with laser hair removal to avoid changes that could be concerning. We also recommend baseline skin exams so we know what we’re looking at before we start treating with lasers, and any changes can be recognized from that baseline status. It’s important to keep an eye out for changes and always be evaluating.”

In December of 2022, Dr. Cices, chief dermatology resident at Mount Sinai Health System, New York, searched PubMed for articles that evaluated changes in melanocytic nevi after laser hair removal procedures. She used the search terms “nevi laser hair removal,” “nevi diode,” “nevi long pulse alexandrite,” “nevi long pulse neodymium doped yttrium aluminum garnet,” and “melanoma laser hair removal,” and limited the analysis to English language patient-based reports that discussed incidental treatment of melanocytic nevi while undergoing hair removal with a laser.

Reports excluded from the analysis were those that focused on changes following hair removal with nonlaser devices such as intense pulsed light (IPL), those evaluating nonmelanocytic nevi such as Becker’s nevus or nevus of Ota, and those evaluating the intentional ablation or removal of melanocytic lesions.

The search yielded 10 relevant studies for systematic review: seven case reports or series and three observational trials, two of which were prospective and one retrospective.

The results of the review, according to Dr. Cices, revealed that clinical and dermoscopic changes were noted to present as early as 15 days after treatment and persist to the maximum follow up time, at 3 years. Commonly reported changes included regression, decreased size, laser-induced asymmetry, bleaching, darkening, and altered pattern on dermoscopy. Histologic changes included mild atypia, thermal damage, scar formation, and regression.

“Although some of the clinical and dermoscopic alterations may be concerning for malignancy, to our knowledge, there are no documented cases of malignant transformation of nevi following treatment with laser hair removal,” she wrote in the abstract.

Dr. Cices acknowledged certain limitations of the systematic review, including the low number of relevant reports and their generally small sample size, many of which were limited to single cases.

Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford, who was asked to comment on the review, characterized the findings as important because laser hair removal is such a commonly performed procedure.

While the study is limited by the small number of studies on the subject matter, “it brings up an important discussion,” Dr. Ibrahimi said in an interview. “Generally speaking, we know that most hair removal lasers do indeed target melanin pigment and can be absorbed by melanocytes. While the wavelengths used for LHR [laser hair removal] will not result in DNA damage or cause mutations that can lead to melanoma, they can sometimes alter the appearance of pigmented lesions and that may change the dermatologist’s ability to monitor them for atypia,” he noted.

“For that reason, I would recommend all patients see a dermatologist for evaluation of their nevi prior to any treatments and they consider very carefully where they get their laser treatments. If they have any atypical pigmented lesions, then that information should be disclosed with the person performing the laser hair removal procedure particularly if there are lesions that are being specifically monitored.”

Dr. Cices reported having no disclosures. Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Accure Acne, AbbVie, Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

AT ASLMS 2023

Alzheimer’s drug may ease hair pulling, skin-picking disorders

Results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that 61% of participants who received memantine were “much or very much improved,” versus 8% in the placebo group.

“Memantine was far more effective than placebo,” lead investigator Jon Grant, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, said in an interview. “However, while subjects responded favorably, that didn’t necessarily mean there were no symptoms.”

The study was published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Underrecognized, disabling

The investigators noted that trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder are underrecognized and are often disabling conditions. However, the researchers pointed out that with prevalence rates of 1.7% for trichotillomania and 2.1% for skin-picking disorder, they are not uncommon.

Behavioral therapy that attempts to reverse these habits is considered first-line treatment, but trained therapists are difficult to find. In addition, the investigators wrote that currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for either disorder, and pharmacologic clinical trials are relatively uncommon.

The existing data from double-blind, placebo-controlled studies support the use of the antipsychotic olanzapine, the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine, and the supplement N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Dr. Grant also noted that previous drug trials involving patients with trichotillomania have been very short in duration.

Prior research has implicated the glutamate system in repetitive motor habits and the urges that drive them. Memantine, a glutamate receptor antagonist, targets excessive glutamatergic drive. To investigate whether this medication may be beneficial for patients with trichotillomania and skin-picking disorders, the investigators conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial.

The study included 100 adults (86 women; mean age, 31.4) with trichotillomania, skin-picking disorder, or both; participants received memantine (n = 55) or placebo (n = 45) for 8 weeks; they received memantine 10 mg or placebo for the first 2 weeks, then 20 mg for the next 6 weeks.

The researchers, who were blinded to assignment, assessed participants every 2 weeks using the National Institute of Mental Health Trichotillomania Symptom Severity Scale, which was modified to include questions for skin-picking disorder.

The team also tracked symptoms and behaviors using additional scales, including the Sheehan Disability Scale and the Clinical Global Impressions severity scale.

At the study’s conclusion, 79 patients remained. Of those, 26 of the 43 participants in the memantine group were “very much” or “much” improved (61%), versus 3 of 36 (8%) in the placebo group. (P < .0001)

Six participants in the memantine group experienced complete remission of symptoms, compared with one in the placebo group. There were no differences between the study groups in terms of adverse events.

Study limitations included the relatively short length of the trial for what should be considered a chronic disease, as well as the inclusion of only mildly to moderately symptomatic participants.

Dr. Grant said that he would like to study how memantine works in combination with behavioral therapy.

‘Two great options’

Katharine Phillips, MD, professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said she has been using memantine for “quite some time” to treat her patients with skin-picking disorder, adding that she uses higher doses of the drug than were tested in the study.

She noted that both NAC and memantine affect glutamate, an amino acid in the brain that is likely involved in repetitive physical or motor habits, such as hair pulling and skin picking.

“The good news is that we have two great options” for the treatment of trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder, said Dr. Phillips, and that both are easy to tolerate.

Future research should focus on longer trials of memantine and at higher doses, as well as other glutamate modulators, she said.

The study was funded by departmental research funds at the University of Chicago. Dr. Grant reported receiving research funding from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and Janssen, as well as yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for his role as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies. He has also received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, McGraw Hill, Oxford University Press, and WW Norton. Dr. Phillips reported receiving royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing and an honorarium from the Merck Manual.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that 61% of participants who received memantine were “much or very much improved,” versus 8% in the placebo group.

“Memantine was far more effective than placebo,” lead investigator Jon Grant, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, said in an interview. “However, while subjects responded favorably, that didn’t necessarily mean there were no symptoms.”

The study was published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Underrecognized, disabling

The investigators noted that trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder are underrecognized and are often disabling conditions. However, the researchers pointed out that with prevalence rates of 1.7% for trichotillomania and 2.1% for skin-picking disorder, they are not uncommon.

Behavioral therapy that attempts to reverse these habits is considered first-line treatment, but trained therapists are difficult to find. In addition, the investigators wrote that currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for either disorder, and pharmacologic clinical trials are relatively uncommon.

The existing data from double-blind, placebo-controlled studies support the use of the antipsychotic olanzapine, the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine, and the supplement N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Dr. Grant also noted that previous drug trials involving patients with trichotillomania have been very short in duration.

Prior research has implicated the glutamate system in repetitive motor habits and the urges that drive them. Memantine, a glutamate receptor antagonist, targets excessive glutamatergic drive. To investigate whether this medication may be beneficial for patients with trichotillomania and skin-picking disorders, the investigators conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial.

The study included 100 adults (86 women; mean age, 31.4) with trichotillomania, skin-picking disorder, or both; participants received memantine (n = 55) or placebo (n = 45) for 8 weeks; they received memantine 10 mg or placebo for the first 2 weeks, then 20 mg for the next 6 weeks.

The researchers, who were blinded to assignment, assessed participants every 2 weeks using the National Institute of Mental Health Trichotillomania Symptom Severity Scale, which was modified to include questions for skin-picking disorder.

The team also tracked symptoms and behaviors using additional scales, including the Sheehan Disability Scale and the Clinical Global Impressions severity scale.

At the study’s conclusion, 79 patients remained. Of those, 26 of the 43 participants in the memantine group were “very much” or “much” improved (61%), versus 3 of 36 (8%) in the placebo group. (P < .0001)

Six participants in the memantine group experienced complete remission of symptoms, compared with one in the placebo group. There were no differences between the study groups in terms of adverse events.

Study limitations included the relatively short length of the trial for what should be considered a chronic disease, as well as the inclusion of only mildly to moderately symptomatic participants.

Dr. Grant said that he would like to study how memantine works in combination with behavioral therapy.

‘Two great options’

Katharine Phillips, MD, professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said she has been using memantine for “quite some time” to treat her patients with skin-picking disorder, adding that she uses higher doses of the drug than were tested in the study.

She noted that both NAC and memantine affect glutamate, an amino acid in the brain that is likely involved in repetitive physical or motor habits, such as hair pulling and skin picking.

“The good news is that we have two great options” for the treatment of trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder, said Dr. Phillips, and that both are easy to tolerate.

Future research should focus on longer trials of memantine and at higher doses, as well as other glutamate modulators, she said.

The study was funded by departmental research funds at the University of Chicago. Dr. Grant reported receiving research funding from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and Janssen, as well as yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for his role as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies. He has also received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, McGraw Hill, Oxford University Press, and WW Norton. Dr. Phillips reported receiving royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing and an honorarium from the Merck Manual.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Results from the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed that 61% of participants who received memantine were “much or very much improved,” versus 8% in the placebo group.

“Memantine was far more effective than placebo,” lead investigator Jon Grant, MD, MPH, professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, said in an interview. “However, while subjects responded favorably, that didn’t necessarily mean there were no symptoms.”

The study was published online in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Underrecognized, disabling

The investigators noted that trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder are underrecognized and are often disabling conditions. However, the researchers pointed out that with prevalence rates of 1.7% for trichotillomania and 2.1% for skin-picking disorder, they are not uncommon.

Behavioral therapy that attempts to reverse these habits is considered first-line treatment, but trained therapists are difficult to find. In addition, the investigators wrote that currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for either disorder, and pharmacologic clinical trials are relatively uncommon.

The existing data from double-blind, placebo-controlled studies support the use of the antipsychotic olanzapine, the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine, and the supplement N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). Dr. Grant also noted that previous drug trials involving patients with trichotillomania have been very short in duration.

Prior research has implicated the glutamate system in repetitive motor habits and the urges that drive them. Memantine, a glutamate receptor antagonist, targets excessive glutamatergic drive. To investigate whether this medication may be beneficial for patients with trichotillomania and skin-picking disorders, the investigators conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial.

The study included 100 adults (86 women; mean age, 31.4) with trichotillomania, skin-picking disorder, or both; participants received memantine (n = 55) or placebo (n = 45) for 8 weeks; they received memantine 10 mg or placebo for the first 2 weeks, then 20 mg for the next 6 weeks.

The researchers, who were blinded to assignment, assessed participants every 2 weeks using the National Institute of Mental Health Trichotillomania Symptom Severity Scale, which was modified to include questions for skin-picking disorder.

The team also tracked symptoms and behaviors using additional scales, including the Sheehan Disability Scale and the Clinical Global Impressions severity scale.

At the study’s conclusion, 79 patients remained. Of those, 26 of the 43 participants in the memantine group were “very much” or “much” improved (61%), versus 3 of 36 (8%) in the placebo group. (P < .0001)

Six participants in the memantine group experienced complete remission of symptoms, compared with one in the placebo group. There were no differences between the study groups in terms of adverse events.

Study limitations included the relatively short length of the trial for what should be considered a chronic disease, as well as the inclusion of only mildly to moderately symptomatic participants.

Dr. Grant said that he would like to study how memantine works in combination with behavioral therapy.

‘Two great options’

Katharine Phillips, MD, professor of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, said she has been using memantine for “quite some time” to treat her patients with skin-picking disorder, adding that she uses higher doses of the drug than were tested in the study.

She noted that both NAC and memantine affect glutamate, an amino acid in the brain that is likely involved in repetitive physical or motor habits, such as hair pulling and skin picking.

“The good news is that we have two great options” for the treatment of trichotillomania and skin-picking disorder, said Dr. Phillips, and that both are easy to tolerate.

Future research should focus on longer trials of memantine and at higher doses, as well as other glutamate modulators, she said.

The study was funded by departmental research funds at the University of Chicago. Dr. Grant reported receiving research funding from Biohaven Pharmaceuticals and Janssen, as well as yearly compensation from Springer Publishing for his role as editor-in-chief of the Journal of Gambling Studies. He has also received royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing, McGraw Hill, Oxford University Press, and WW Norton. Dr. Phillips reported receiving royalties from American Psychiatric Publishing and an honorarium from the Merck Manual.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

FDA clears first patch to treat axillary hyperhidrosis

The Food and Drug Administration on April 13 cleared the first patch to reduce excessive underarm sweating for adults with primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

The single-use, disposable, prescription-only patch will be marketed as Brella. It consists of a sodium sheet with an adhesive overlay. A health care provider applies it to the patient’s underarm for up to 3 minutes and then repeats the process on the other underarm.

The developer, Candesant Biomedical, says the patch uses the company’s patented targeted alkali thermolysis (TAT) technology, which was built on the principle that heat is generated when sodium reacts with water in sweat. “The thermal energy created by the sodium sheet is precisely localized, microtargeting sweat glands to significantly reduce sweat production,” according to the company’s press release announcing the FDA decision.

FDA clearance was based on data from the pivotal randomized, double-blind, multicenter SAHARA study, which indicated that the product is effective and well tolerated.

Patients experienced a reduction in sweat that was maintained for 3 months or longer, according to trial results.

The SAHARA trial results were reported in a late-breaking abstract at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology in March.

The trial enrolled 110 individuals with Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) scores of 3 or 4 (indicating frequent sweating or sweating that always interferes with daily activities). Trial participants were randomly assigned to receive either an active TAT or a sham patch, which was applied for up to 3 minutes.

At the meeting, lead investigator David M. Pariser, MD, a dermatologist practicing in Norfolk, Va., reported that at 4 weeks, 63.6% of patients in the active patch group achieved an HDSS score of 1 or 2, compared with 44.2% of those in the sham treatment group (P = .0332). Also, 43.2% of those in the active-patch group achieved an improvement of 2 points or greater on the HDSS, as compared with 16.3% of those in the sham treatment group (P = .0107) .

In addition, 9.1% of those in the active-patch group achieved a 3-point improvement on the HDSS, compared with none in the sham group. “That’s an amazing improvement; you’re basically going from moderate or severe to none,” Dr. Pariser said at the meeting.

As for adverse events (AEs), 13 patients in the active-patch group experienced AEs at the treatment site. Six patients experienced erythema; four experienced erosion; two experienced burning, itching, or stinging; and one had underarm odor.

“The two procedure-related AEs in the TAT-treated group were compensatory sweating and irritant contact dermatitis due to the adhesive,” Dr. Pariser said. He noted that most AEs resolved in fewer than 2 weeks, and all AEs were mild to moderate.

According to the International Hyperhidrosis Society, about 1.3 million people in the United States have axillary hyperhidrosis, and about a third report that sweating is barely tolerable and frequently interferes with daily activities or is intolerable and always interferes with daily activities.

The patch will be available within months in select U.S. markets beginning in late summer. The company says the markets will be listed on its website.

A company representative told this news organization that because it is an in-office procedure, pricing will vary, depending on the practice. “With that said, Candesant expects doctors will charge about the same for one session of the Brella SweatControl Patch as they would for a high-end, in-office facial or chemical peel,” the representative said.

Dr. Pariser is a consultant or investigator for Bickel Biotechnology, Biofrontera AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Celgene Corporation, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration on April 13 cleared the first patch to reduce excessive underarm sweating for adults with primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

The single-use, disposable, prescription-only patch will be marketed as Brella. It consists of a sodium sheet with an adhesive overlay. A health care provider applies it to the patient’s underarm for up to 3 minutes and then repeats the process on the other underarm.

The developer, Candesant Biomedical, says the patch uses the company’s patented targeted alkali thermolysis (TAT) technology, which was built on the principle that heat is generated when sodium reacts with water in sweat. “The thermal energy created by the sodium sheet is precisely localized, microtargeting sweat glands to significantly reduce sweat production,” according to the company’s press release announcing the FDA decision.

FDA clearance was based on data from the pivotal randomized, double-blind, multicenter SAHARA study, which indicated that the product is effective and well tolerated.

Patients experienced a reduction in sweat that was maintained for 3 months or longer, according to trial results.

The SAHARA trial results were reported in a late-breaking abstract at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology in March.

The trial enrolled 110 individuals with Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) scores of 3 or 4 (indicating frequent sweating or sweating that always interferes with daily activities). Trial participants were randomly assigned to receive either an active TAT or a sham patch, which was applied for up to 3 minutes.

At the meeting, lead investigator David M. Pariser, MD, a dermatologist practicing in Norfolk, Va., reported that at 4 weeks, 63.6% of patients in the active patch group achieved an HDSS score of 1 or 2, compared with 44.2% of those in the sham treatment group (P = .0332). Also, 43.2% of those in the active-patch group achieved an improvement of 2 points or greater on the HDSS, as compared with 16.3% of those in the sham treatment group (P = .0107) .

In addition, 9.1% of those in the active-patch group achieved a 3-point improvement on the HDSS, compared with none in the sham group. “That’s an amazing improvement; you’re basically going from moderate or severe to none,” Dr. Pariser said at the meeting.

As for adverse events (AEs), 13 patients in the active-patch group experienced AEs at the treatment site. Six patients experienced erythema; four experienced erosion; two experienced burning, itching, or stinging; and one had underarm odor.

“The two procedure-related AEs in the TAT-treated group were compensatory sweating and irritant contact dermatitis due to the adhesive,” Dr. Pariser said. He noted that most AEs resolved in fewer than 2 weeks, and all AEs were mild to moderate.

According to the International Hyperhidrosis Society, about 1.3 million people in the United States have axillary hyperhidrosis, and about a third report that sweating is barely tolerable and frequently interferes with daily activities or is intolerable and always interferes with daily activities.

The patch will be available within months in select U.S. markets beginning in late summer. The company says the markets will be listed on its website.

A company representative told this news organization that because it is an in-office procedure, pricing will vary, depending on the practice. “With that said, Candesant expects doctors will charge about the same for one session of the Brella SweatControl Patch as they would for a high-end, in-office facial or chemical peel,” the representative said.

Dr. Pariser is a consultant or investigator for Bickel Biotechnology, Biofrontera AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Celgene Corporation, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration on April 13 cleared the first patch to reduce excessive underarm sweating for adults with primary axillary hyperhidrosis.

The single-use, disposable, prescription-only patch will be marketed as Brella. It consists of a sodium sheet with an adhesive overlay. A health care provider applies it to the patient’s underarm for up to 3 minutes and then repeats the process on the other underarm.

The developer, Candesant Biomedical, says the patch uses the company’s patented targeted alkali thermolysis (TAT) technology, which was built on the principle that heat is generated when sodium reacts with water in sweat. “The thermal energy created by the sodium sheet is precisely localized, microtargeting sweat glands to significantly reduce sweat production,” according to the company’s press release announcing the FDA decision.

FDA clearance was based on data from the pivotal randomized, double-blind, multicenter SAHARA study, which indicated that the product is effective and well tolerated.

Patients experienced a reduction in sweat that was maintained for 3 months or longer, according to trial results.

The SAHARA trial results were reported in a late-breaking abstract at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology in March.

The trial enrolled 110 individuals with Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale (HDSS) scores of 3 or 4 (indicating frequent sweating or sweating that always interferes with daily activities). Trial participants were randomly assigned to receive either an active TAT or a sham patch, which was applied for up to 3 minutes.

At the meeting, lead investigator David M. Pariser, MD, a dermatologist practicing in Norfolk, Va., reported that at 4 weeks, 63.6% of patients in the active patch group achieved an HDSS score of 1 or 2, compared with 44.2% of those in the sham treatment group (P = .0332). Also, 43.2% of those in the active-patch group achieved an improvement of 2 points or greater on the HDSS, as compared with 16.3% of those in the sham treatment group (P = .0107) .

In addition, 9.1% of those in the active-patch group achieved a 3-point improvement on the HDSS, compared with none in the sham group. “That’s an amazing improvement; you’re basically going from moderate or severe to none,” Dr. Pariser said at the meeting.

As for adverse events (AEs), 13 patients in the active-patch group experienced AEs at the treatment site. Six patients experienced erythema; four experienced erosion; two experienced burning, itching, or stinging; and one had underarm odor.

“The two procedure-related AEs in the TAT-treated group were compensatory sweating and irritant contact dermatitis due to the adhesive,” Dr. Pariser said. He noted that most AEs resolved in fewer than 2 weeks, and all AEs were mild to moderate.

According to the International Hyperhidrosis Society, about 1.3 million people in the United States have axillary hyperhidrosis, and about a third report that sweating is barely tolerable and frequently interferes with daily activities or is intolerable and always interferes with daily activities.

The patch will be available within months in select U.S. markets beginning in late summer. The company says the markets will be listed on its website.

A company representative told this news organization that because it is an in-office procedure, pricing will vary, depending on the practice. “With that said, Candesant expects doctors will charge about the same for one session of the Brella SweatControl Patch as they would for a high-end, in-office facial or chemical peel,” the representative said.

Dr. Pariser is a consultant or investigator for Bickel Biotechnology, Biofrontera AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Celgene Corporation, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Brittle fingernails

The abnormal upward curve to the fingernails was consistent with a diagnosis of koilonychia—otherwise known as spoon nails.

Koilonychia is an abnormal nail growth pattern where the distal nail matrix is depressed below its normal level, resulting in the spoon shape. The reverse, where the distal nail matrix is elevated in contrast to the proximal nail matrix, results in clubbing.1

There are multiple factors and diseases that result in koilonychia, including lichen planus, psoriasis, nutritional deficiencies (including iron deficiency anemia), and endocrinopathies.1 Lichen planus, which can cause koilonychia, often affects multiple nails and can also cause an associated central ridge pattern. Psoriasis may display a range of nail abnormalities; these include koilonychia, pitting onycholysis, and oil staining.

This patient did not have any signs or symptoms of psoriasis or lichen planus of her nails or skin. A review of her laboratory tests on file made no mention of anemia. Her chemistry profile—including liver tests, renal function tests, and protein levels—were all normal except for glucose levels, which was consistent with her prediabetes. Her thyroid function was also normal. No additional testing was performed since she had no symptoms, physical exam findings, or laboratory clues that pointed to other diseases or systemic processes.

The patient was advised to pick up over-the-counter nail strengtheners and to keep her fingernails trimmed short to minimize the likelihood of painful distal splitting that often occurs with brittle nails. Her physician advised her to follow up with the primary care team if she developed any new signs or symptoms.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Walker J, Baran R, Vélez N, et al. Koilonychia: an update on pathophysiology, differential diagnosis and clinical relevance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1985-1991. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13610

The abnormal upward curve to the fingernails was consistent with a diagnosis of koilonychia—otherwise known as spoon nails.

Koilonychia is an abnormal nail growth pattern where the distal nail matrix is depressed below its normal level, resulting in the spoon shape. The reverse, where the distal nail matrix is elevated in contrast to the proximal nail matrix, results in clubbing.1

There are multiple factors and diseases that result in koilonychia, including lichen planus, psoriasis, nutritional deficiencies (including iron deficiency anemia), and endocrinopathies.1 Lichen planus, which can cause koilonychia, often affects multiple nails and can also cause an associated central ridge pattern. Psoriasis may display a range of nail abnormalities; these include koilonychia, pitting onycholysis, and oil staining.

This patient did not have any signs or symptoms of psoriasis or lichen planus of her nails or skin. A review of her laboratory tests on file made no mention of anemia. Her chemistry profile—including liver tests, renal function tests, and protein levels—were all normal except for glucose levels, which was consistent with her prediabetes. Her thyroid function was also normal. No additional testing was performed since she had no symptoms, physical exam findings, or laboratory clues that pointed to other diseases or systemic processes.

The patient was advised to pick up over-the-counter nail strengtheners and to keep her fingernails trimmed short to minimize the likelihood of painful distal splitting that often occurs with brittle nails. Her physician advised her to follow up with the primary care team if she developed any new signs or symptoms.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The abnormal upward curve to the fingernails was consistent with a diagnosis of koilonychia—otherwise known as spoon nails.

Koilonychia is an abnormal nail growth pattern where the distal nail matrix is depressed below its normal level, resulting in the spoon shape. The reverse, where the distal nail matrix is elevated in contrast to the proximal nail matrix, results in clubbing.1

There are multiple factors and diseases that result in koilonychia, including lichen planus, psoriasis, nutritional deficiencies (including iron deficiency anemia), and endocrinopathies.1 Lichen planus, which can cause koilonychia, often affects multiple nails and can also cause an associated central ridge pattern. Psoriasis may display a range of nail abnormalities; these include koilonychia, pitting onycholysis, and oil staining.

This patient did not have any signs or symptoms of psoriasis or lichen planus of her nails or skin. A review of her laboratory tests on file made no mention of anemia. Her chemistry profile—including liver tests, renal function tests, and protein levels—were all normal except for glucose levels, which was consistent with her prediabetes. Her thyroid function was also normal. No additional testing was performed since she had no symptoms, physical exam findings, or laboratory clues that pointed to other diseases or systemic processes.

The patient was advised to pick up over-the-counter nail strengtheners and to keep her fingernails trimmed short to minimize the likelihood of painful distal splitting that often occurs with brittle nails. Her physician advised her to follow up with the primary care team if she developed any new signs or symptoms.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Walker J, Baran R, Vélez N, et al. Koilonychia: an update on pathophysiology, differential diagnosis and clinical relevance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1985-1991. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13610

1. Walker J, Baran R, Vélez N, et al. Koilonychia: an update on pathophysiology, differential diagnosis and clinical relevance. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1985-1991. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13610

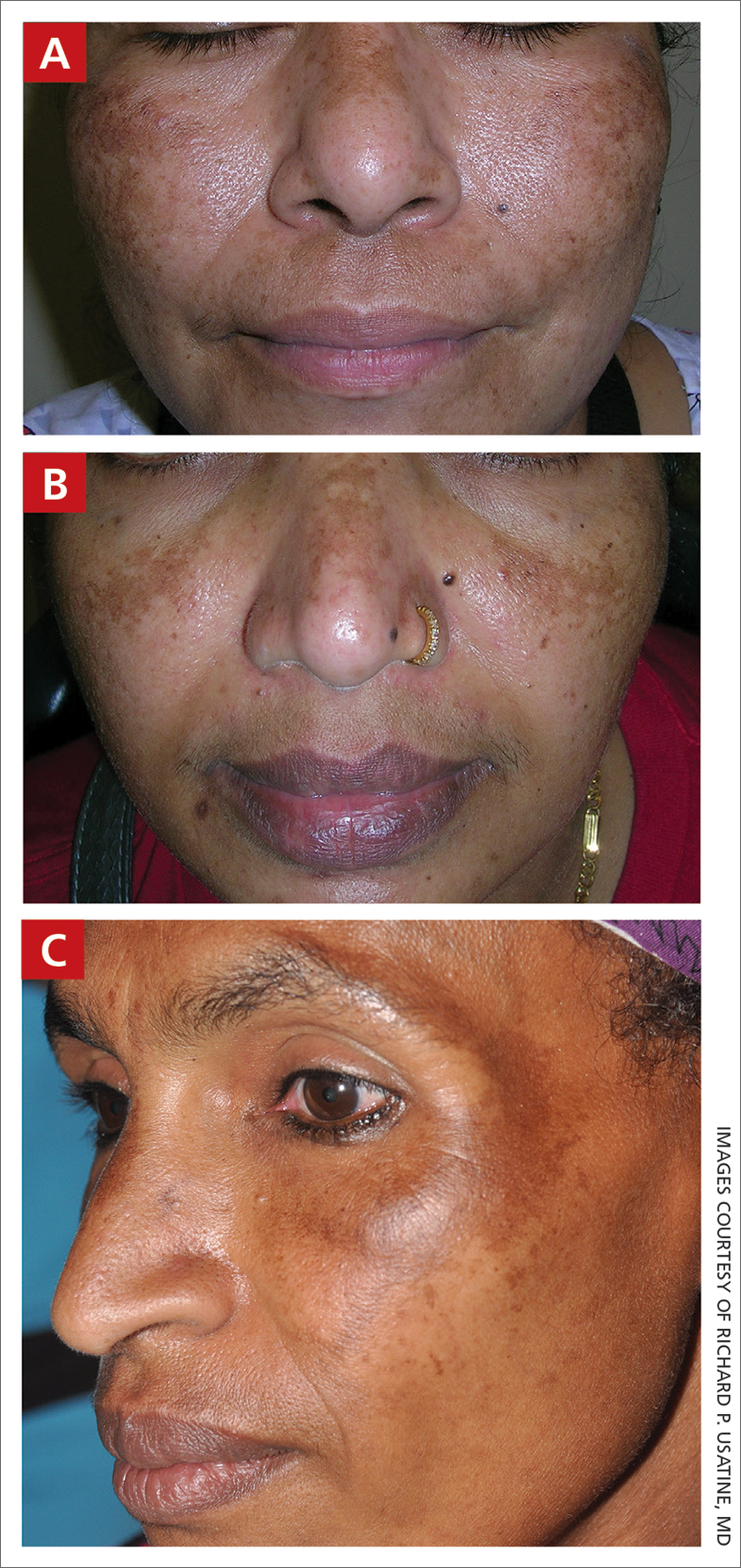

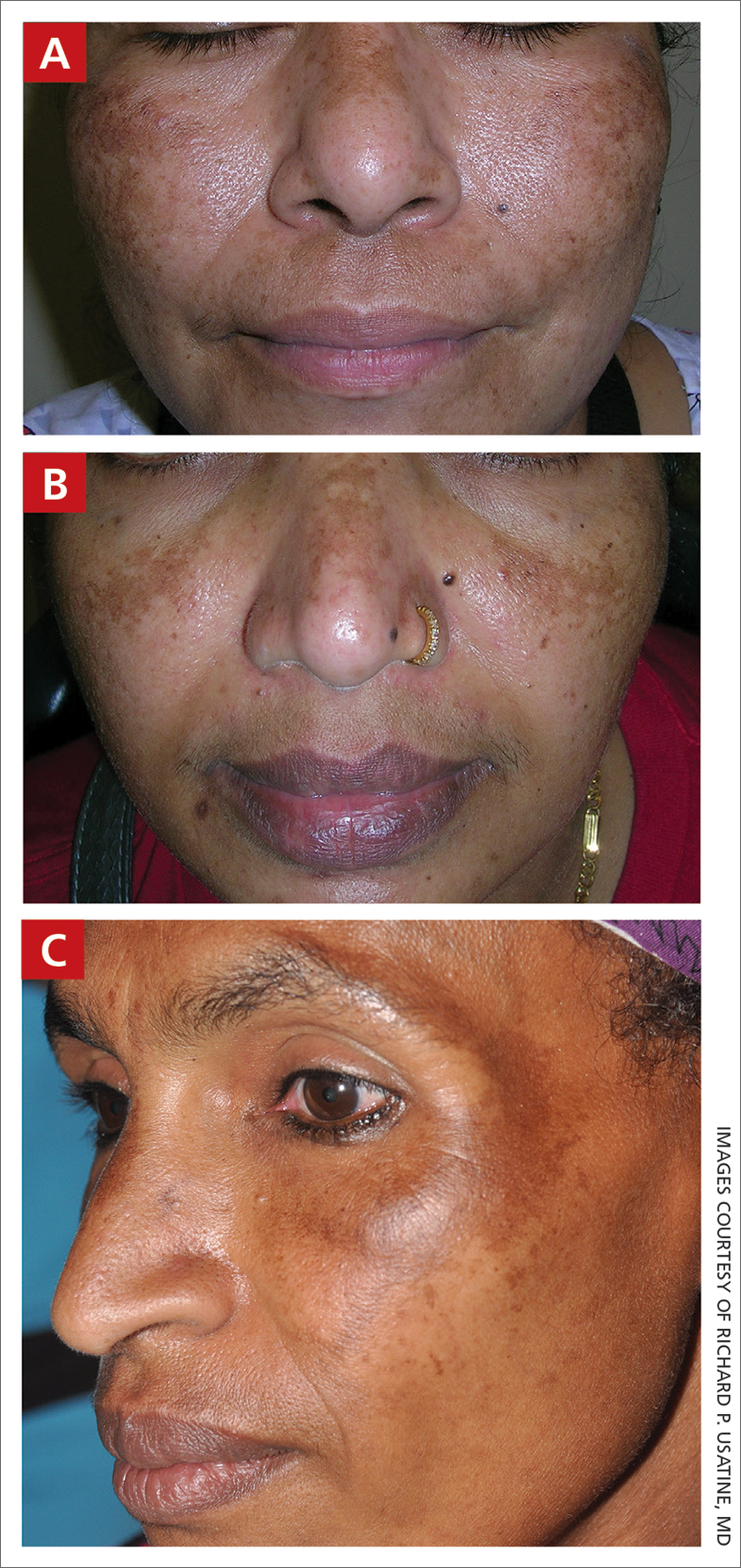

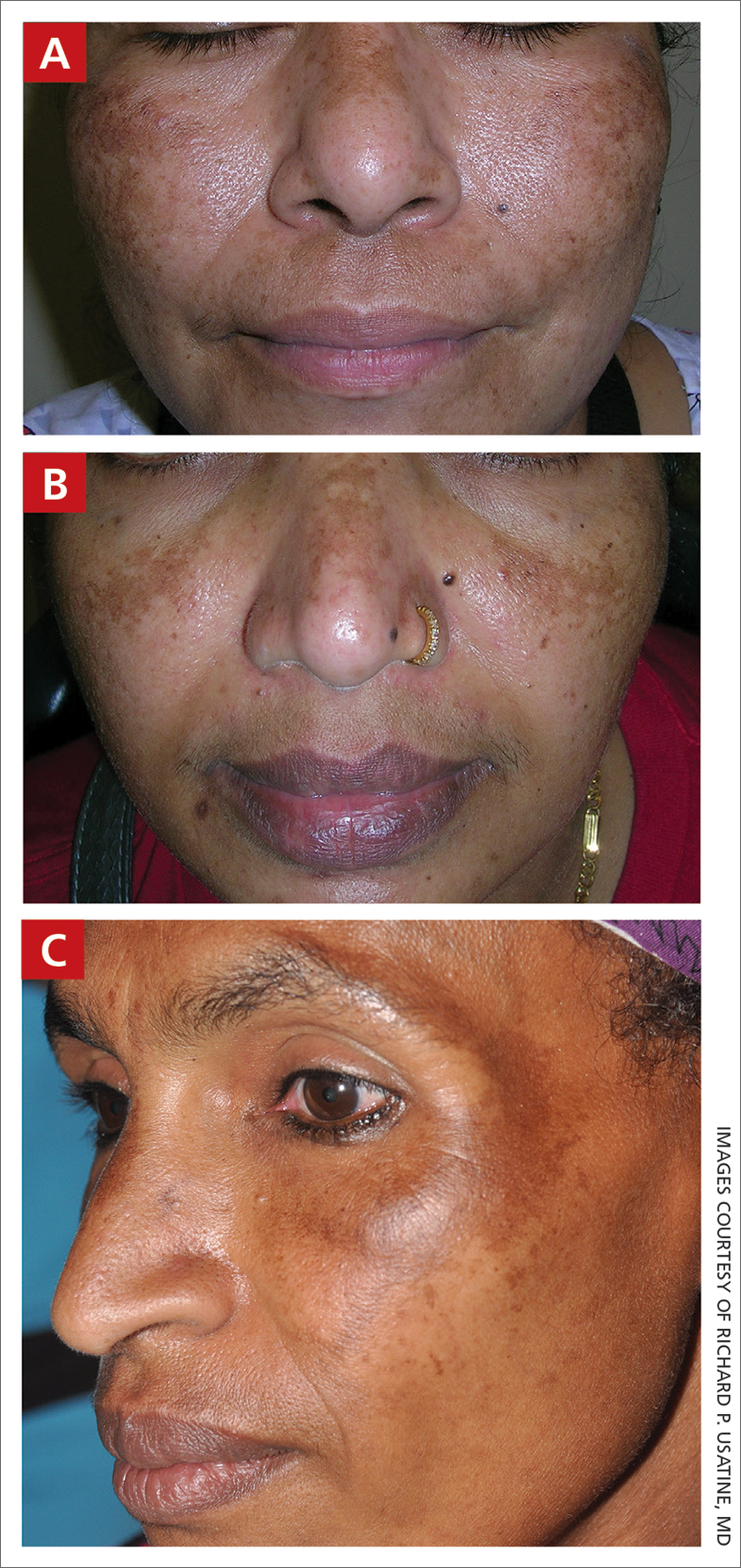

Dark facial lesion

Although an elevated and pigmented lesion should be considered for possible melanoma, this one had prominent telangiectasias and was proven to be a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on biopsy.

While the literature often focuses on light-colored skin types and the high risk of skin cancers, individuals with darker skin can also get melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Half of the BCCs in African American people are pigmented BCCs, compared to less than 10% for Caucasian individuals. Individuals who are Hispanic have twice the likelihood of pigmented BCCs as those who are Caucasian.1 Pigmented BCCs manifest as darker lesions, as occurred in this individual. Nonpigmented BCCs tend to be pink or pale in color.

Typically, superficial and very small, nodular BCCs can be successfully treated with 2 cycles of electrodesiccation and curettage. EDC should, however, be avoided in low-risk BCCs when these lesions occur in areas of secondary hair growth, such as the beard or scalp. This is because the epidermis follows the hair follicle, and in sites with deep hair follicles, EDC would have to get down to the subcutis to effectively clear the tumor.

For larger, nodular BCCs, full-thickness excision with adequate margins is warranted. For high-risk types, and those in high-risk areas near the nose, eyes, mouth, and ears, Mohs micrographic surgery is recommended to maximize the likelihood of complete excision while minimizing the loss of normal tissue.

Since the physician suspected this was a pigmented BCC, he performed a superficial shave biopsy on a small representative area of the lesion for diagnosis. This patient’s biopsy confirmed a nodular-type pigmented BCC. The lesion was removed in the office with 5-mm margins oriented along the resting skin tension lines with good closure and cosmetic results.

The patient was advised to have routine skin evaluations every 6 months due to the high risk of additional cancers. He was also advised to take oral niacinamide 500 mg twice daily, which can reduce the risk of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers by 15% and 23%, respectively, in those who have had lesions.2

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Higgins S, Nazemi A, Chow M, et al. Review of nonmelanoma skin cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:903-910. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001547

2. Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Although an elevated and pigmented lesion should be considered for possible melanoma, this one had prominent telangiectasias and was proven to be a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on biopsy.

While the literature often focuses on light-colored skin types and the high risk of skin cancers, individuals with darker skin can also get melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Half of the BCCs in African American people are pigmented BCCs, compared to less than 10% for Caucasian individuals. Individuals who are Hispanic have twice the likelihood of pigmented BCCs as those who are Caucasian.1 Pigmented BCCs manifest as darker lesions, as occurred in this individual. Nonpigmented BCCs tend to be pink or pale in color.

Typically, superficial and very small, nodular BCCs can be successfully treated with 2 cycles of electrodesiccation and curettage. EDC should, however, be avoided in low-risk BCCs when these lesions occur in areas of secondary hair growth, such as the beard or scalp. This is because the epidermis follows the hair follicle, and in sites with deep hair follicles, EDC would have to get down to the subcutis to effectively clear the tumor.

For larger, nodular BCCs, full-thickness excision with adequate margins is warranted. For high-risk types, and those in high-risk areas near the nose, eyes, mouth, and ears, Mohs micrographic surgery is recommended to maximize the likelihood of complete excision while minimizing the loss of normal tissue.

Since the physician suspected this was a pigmented BCC, he performed a superficial shave biopsy on a small representative area of the lesion for diagnosis. This patient’s biopsy confirmed a nodular-type pigmented BCC. The lesion was removed in the office with 5-mm margins oriented along the resting skin tension lines with good closure and cosmetic results.

The patient was advised to have routine skin evaluations every 6 months due to the high risk of additional cancers. He was also advised to take oral niacinamide 500 mg twice daily, which can reduce the risk of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers by 15% and 23%, respectively, in those who have had lesions.2

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Although an elevated and pigmented lesion should be considered for possible melanoma, this one had prominent telangiectasias and was proven to be a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on biopsy.

While the literature often focuses on light-colored skin types and the high risk of skin cancers, individuals with darker skin can also get melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer. Half of the BCCs in African American people are pigmented BCCs, compared to less than 10% for Caucasian individuals. Individuals who are Hispanic have twice the likelihood of pigmented BCCs as those who are Caucasian.1 Pigmented BCCs manifest as darker lesions, as occurred in this individual. Nonpigmented BCCs tend to be pink or pale in color.

Typically, superficial and very small, nodular BCCs can be successfully treated with 2 cycles of electrodesiccation and curettage. EDC should, however, be avoided in low-risk BCCs when these lesions occur in areas of secondary hair growth, such as the beard or scalp. This is because the epidermis follows the hair follicle, and in sites with deep hair follicles, EDC would have to get down to the subcutis to effectively clear the tumor.

For larger, nodular BCCs, full-thickness excision with adequate margins is warranted. For high-risk types, and those in high-risk areas near the nose, eyes, mouth, and ears, Mohs micrographic surgery is recommended to maximize the likelihood of complete excision while minimizing the loss of normal tissue.

Since the physician suspected this was a pigmented BCC, he performed a superficial shave biopsy on a small representative area of the lesion for diagnosis. This patient’s biopsy confirmed a nodular-type pigmented BCC. The lesion was removed in the office with 5-mm margins oriented along the resting skin tension lines with good closure and cosmetic results.

The patient was advised to have routine skin evaluations every 6 months due to the high risk of additional cancers. He was also advised to take oral niacinamide 500 mg twice daily, which can reduce the risk of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers by 15% and 23%, respectively, in those who have had lesions.2

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Higgins S, Nazemi A, Chow M, et al. Review of nonmelanoma skin cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:903-910. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001547

2. Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

1. Higgins S, Nazemi A, Chow M, et al. Review of nonmelanoma skin cancer in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:903-910. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001547

2. Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

A 50-year-old White male presented with a 4- to 5-year history of progressively growing violaceous lesions on his left lower extremity

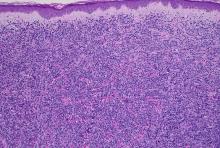

with scarce T-cells, classically presenting as rapidly progressive, plum-colored lesions on the lower extremities.1,2 CBCLs, with PCDLBCL-LT accounting for 4%, make up the minority of cutaneous lymphomas in the Western world.1-3 The leg type variant, typically demonstrating a female predominance and median age of onset in the 70s, is clinically aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis, increased recurrence rate, and 40%-60% 5-year survival rate.1-5

Histologically, this variant demonstrates a diffuse sheet-like growth of enlarged atypical B-cells distinctively separated from the epidermis by a prominent grenz zone. Classic PCDLBCL-LT immunophenotype includes B-cell markers CD20 and IgM; triple expressor phenotype indicating c-MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 positivity; as well as CD10 negativity, lack of BCL-2 rearrangement, and presence of a positive MYD-88 molecular result.

Other characteristic histopathological findings include positivity for post-germinal markers IRF4/MUM-1 and FOXP-1, positivity for additional B-cell markers, including CD79 and PAX5, and negativity of t(14;18) (q32;21).1,3-5

This case is of significant interest as it falls within the approximately 10% of PCDLBCL-LT cases demonstrating weak to negative MUM-1 staining, in addition to its presentation in a younger male individual.

While MUM-1 positivity is common in this subtype, its presence, or lack thereof, should not be looked at in isolation when evaluating diagnostic criteria, nor has it been shown to have a statistically significant effect on survival rate – in contrast to factors like lesion location on the leg versus non-leg lesions, multiple lesions at diagnosis, and dissemination to other sites.2,6

PCDLBCL-LT can uncommonly present in non-leg locations and only 10% depict associated B-symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or lymphadenopathy.2,6 First-line treatment is with the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen – consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone – although radiotherapy is sometimes considered in patients with a single small lesion.1,2

Because of possible cutaneous involvement beyond the legs, common lack of systemic symptoms, and variable immunophenotypes, this case of MUM-1 negative PCDLBCL-LT highlights the importance of a clinicopathological approach to differentiate the subtypes of CBCLs, allowing for proper and individualized stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

This case was submitted and written by Marlee Hill, BS, Michael Franzetti, MD, Jeffrey McBride, MD, and Allison Hood, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. They also provided the photos. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14.

2. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768-85.

3. Sukswai N et al. Pathology. 2020;52(1):53-67.

4. Hristov AC. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(8):876-81.

5. Sokol L et al. Cancer Control. 2012;19(3):236-44.

6. Grange F et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1144-50.

with scarce T-cells, classically presenting as rapidly progressive, plum-colored lesions on the lower extremities.1,2 CBCLs, with PCDLBCL-LT accounting for 4%, make up the minority of cutaneous lymphomas in the Western world.1-3 The leg type variant, typically demonstrating a female predominance and median age of onset in the 70s, is clinically aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis, increased recurrence rate, and 40%-60% 5-year survival rate.1-5

Histologically, this variant demonstrates a diffuse sheet-like growth of enlarged atypical B-cells distinctively separated from the epidermis by a prominent grenz zone. Classic PCDLBCL-LT immunophenotype includes B-cell markers CD20 and IgM; triple expressor phenotype indicating c-MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 positivity; as well as CD10 negativity, lack of BCL-2 rearrangement, and presence of a positive MYD-88 molecular result.

Other characteristic histopathological findings include positivity for post-germinal markers IRF4/MUM-1 and FOXP-1, positivity for additional B-cell markers, including CD79 and PAX5, and negativity of t(14;18) (q32;21).1,3-5

This case is of significant interest as it falls within the approximately 10% of PCDLBCL-LT cases demonstrating weak to negative MUM-1 staining, in addition to its presentation in a younger male individual.

While MUM-1 positivity is common in this subtype, its presence, or lack thereof, should not be looked at in isolation when evaluating diagnostic criteria, nor has it been shown to have a statistically significant effect on survival rate – in contrast to factors like lesion location on the leg versus non-leg lesions, multiple lesions at diagnosis, and dissemination to other sites.2,6

PCDLBCL-LT can uncommonly present in non-leg locations and only 10% depict associated B-symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or lymphadenopathy.2,6 First-line treatment is with the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen – consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone – although radiotherapy is sometimes considered in patients with a single small lesion.1,2

Because of possible cutaneous involvement beyond the legs, common lack of systemic symptoms, and variable immunophenotypes, this case of MUM-1 negative PCDLBCL-LT highlights the importance of a clinicopathological approach to differentiate the subtypes of CBCLs, allowing for proper and individualized stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

This case was submitted and written by Marlee Hill, BS, Michael Franzetti, MD, Jeffrey McBride, MD, and Allison Hood, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. They also provided the photos. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14.

2. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768-85.

3. Sukswai N et al. Pathology. 2020;52(1):53-67.

4. Hristov AC. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(8):876-81.

5. Sokol L et al. Cancer Control. 2012;19(3):236-44.

6. Grange F et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1144-50.

with scarce T-cells, classically presenting as rapidly progressive, plum-colored lesions on the lower extremities.1,2 CBCLs, with PCDLBCL-LT accounting for 4%, make up the minority of cutaneous lymphomas in the Western world.1-3 The leg type variant, typically demonstrating a female predominance and median age of onset in the 70s, is clinically aggressive and associated with a poorer prognosis, increased recurrence rate, and 40%-60% 5-year survival rate.1-5

Histologically, this variant demonstrates a diffuse sheet-like growth of enlarged atypical B-cells distinctively separated from the epidermis by a prominent grenz zone. Classic PCDLBCL-LT immunophenotype includes B-cell markers CD20 and IgM; triple expressor phenotype indicating c-MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 positivity; as well as CD10 negativity, lack of BCL-2 rearrangement, and presence of a positive MYD-88 molecular result.

Other characteristic histopathological findings include positivity for post-germinal markers IRF4/MUM-1 and FOXP-1, positivity for additional B-cell markers, including CD79 and PAX5, and negativity of t(14;18) (q32;21).1,3-5

This case is of significant interest as it falls within the approximately 10% of PCDLBCL-LT cases demonstrating weak to negative MUM-1 staining, in addition to its presentation in a younger male individual.

While MUM-1 positivity is common in this subtype, its presence, or lack thereof, should not be looked at in isolation when evaluating diagnostic criteria, nor has it been shown to have a statistically significant effect on survival rate – in contrast to factors like lesion location on the leg versus non-leg lesions, multiple lesions at diagnosis, and dissemination to other sites.2,6

PCDLBCL-LT can uncommonly present in non-leg locations and only 10% depict associated B-symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, weight loss, or lymphadenopathy.2,6 First-line treatment is with the R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen – consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone – although radiotherapy is sometimes considered in patients with a single small lesion.1,2

Because of possible cutaneous involvement beyond the legs, common lack of systemic symptoms, and variable immunophenotypes, this case of MUM-1 negative PCDLBCL-LT highlights the importance of a clinicopathological approach to differentiate the subtypes of CBCLs, allowing for proper and individualized stratification of risk, prognosis, and treatment.

This case was submitted and written by Marlee Hill, BS, Michael Franzetti, MD, Jeffrey McBride, MD, and Allison Hood, MD, of the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. They also provided the photos. Donna Bilu Martin, MD, edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2019;133(16):1703-14.

2. Willemze R et al. Blood. 2005;105(10):3768-85.

3. Sukswai N et al. Pathology. 2020;52(1):53-67.

4. Hristov AC. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(8):876-81.

5. Sokol L et al. Cancer Control. 2012;19(3):236-44.

6. Grange F et al. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(9):1144-50.

There was no cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy.

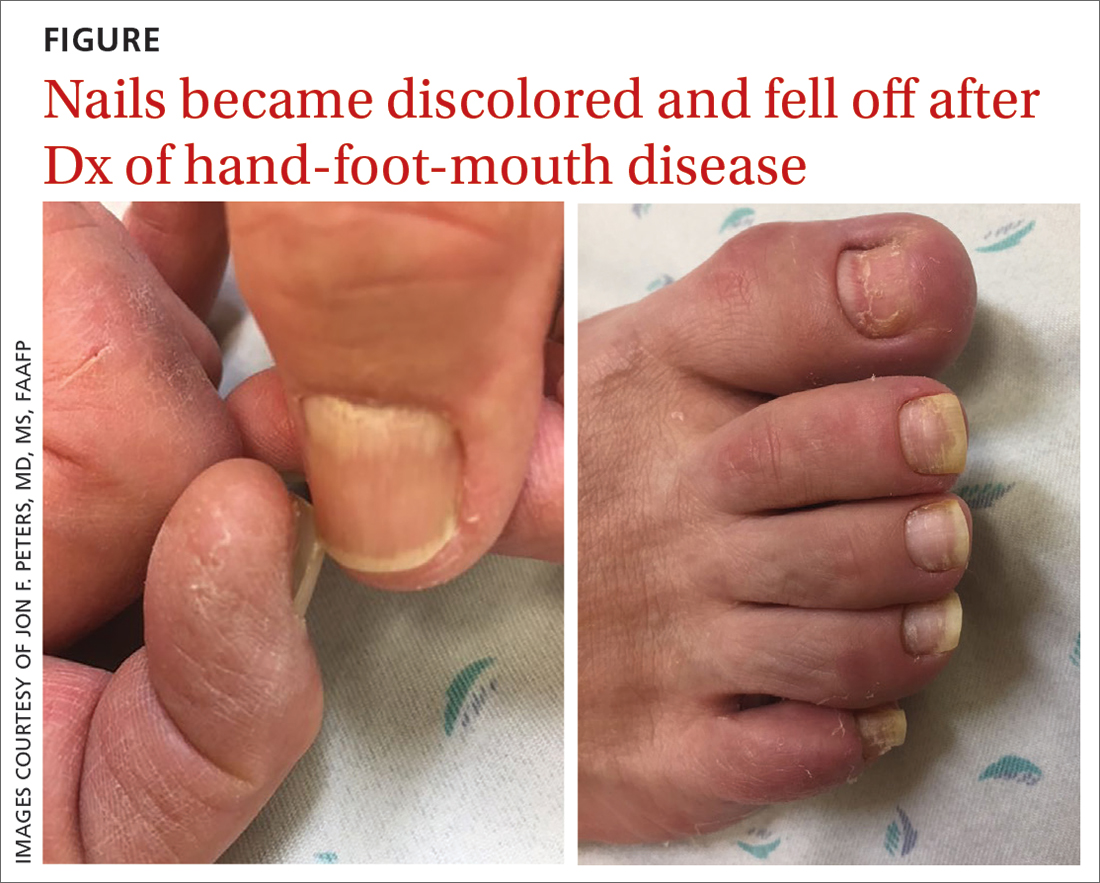

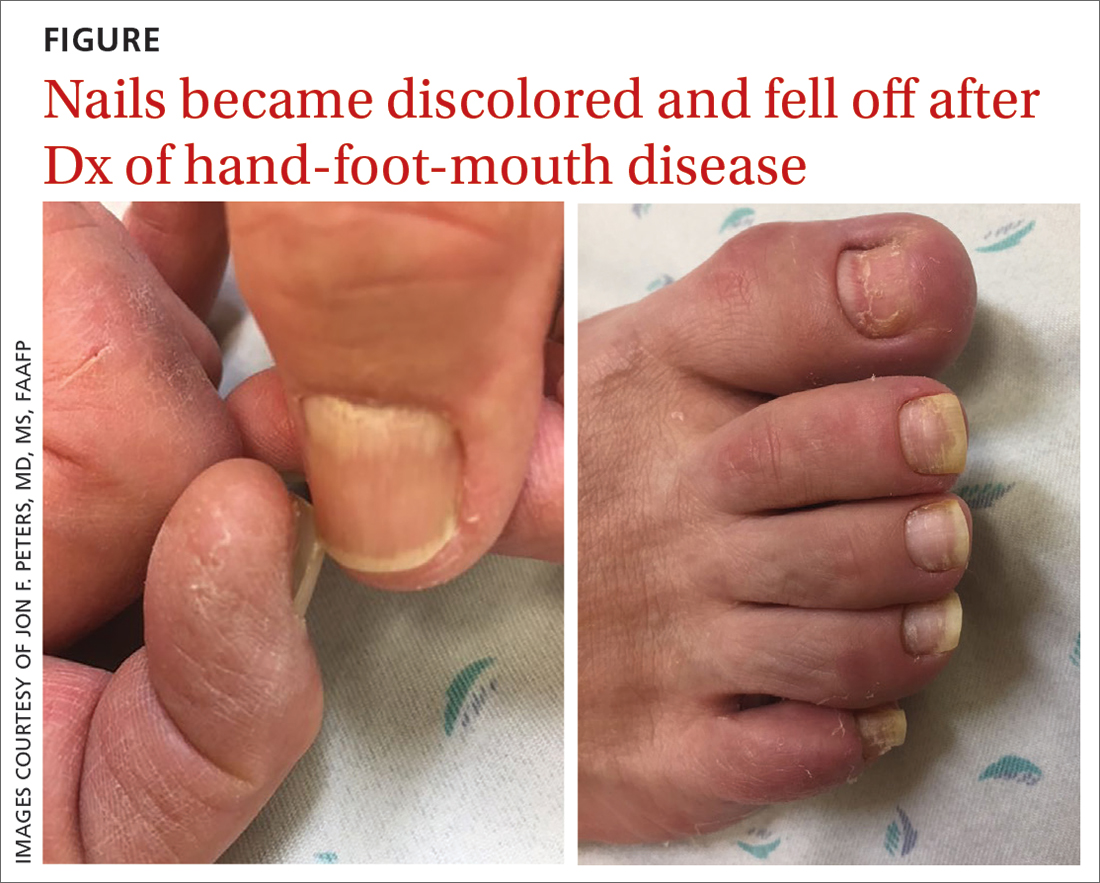

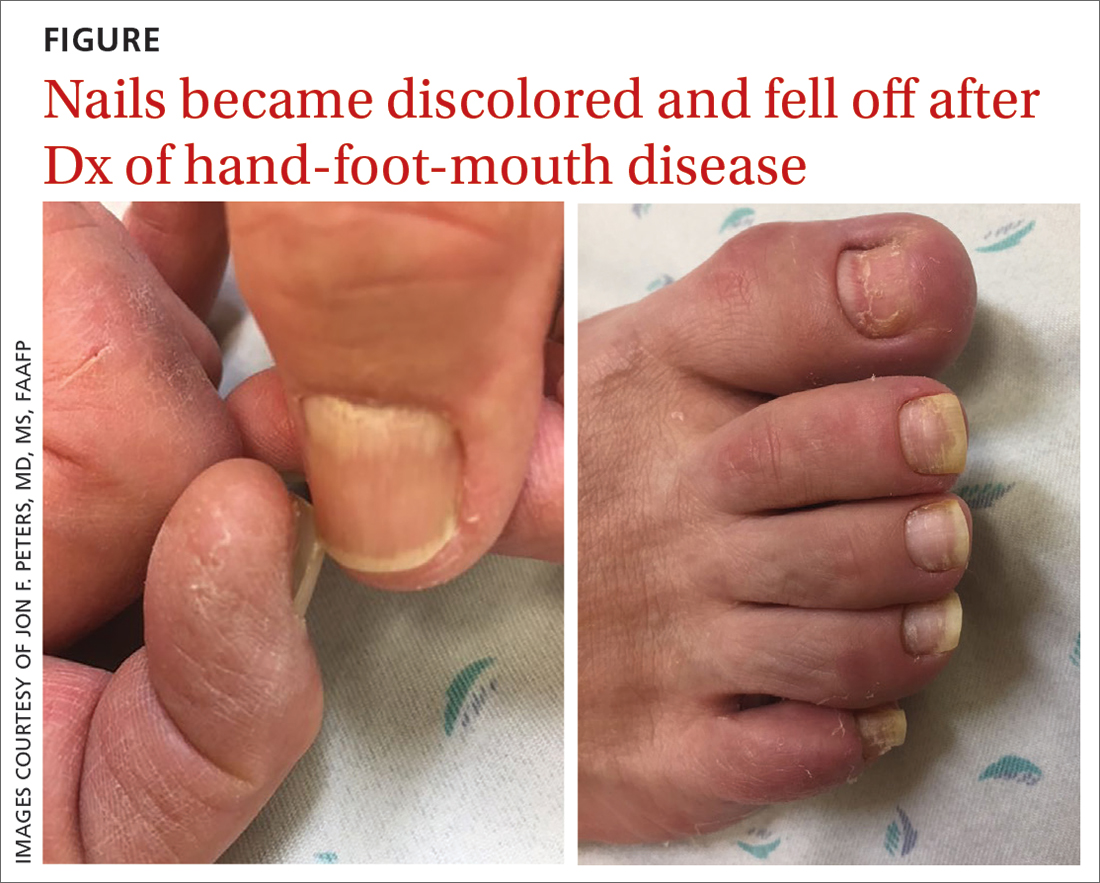

75-year-old man • recent history of hand-foot-mouth disease • discolored fingernails and toenails lifting from the proximal end • Dx?

THE CASE

A 75-year-old man sought care from his primary care physician because his “fingernails and toenails [were] all falling off.” He did not feel ill and had no other complaints. His vital signs were unremarkable. He had no history of malignancies, chronic skin conditions, or systemic diseases. His fingernails and toenails were discolored and lifting from the proximal end of his nail beds (FIGURE). One of his great toenails had already fallen off, 1 thumb nail was minimally attached with the cuticle, and the rest of his nails were loose and in the process of separating from their nail beds. There was no nail pitting, rash, or joint swelling and tenderness.

The patient reported that while on vacation in Hawaii 3 weeks earlier, he had sought care at an urgent care clinic for a painless rash on his hands and the soles of his feet. At that time, he did not feel ill or have mouth ulcers, penile discharge, or arthralgia. There had been no recent changes to his prescription medications, which included finasteride, terazosin, omeprazole, and an albuterol inhaler. He denied taking over-the-counter medications or supplements.

The physical exam at the urgent care had revealed multiple blotchy, dark, 0.5- to 1-cm nonpruritic lesions that were desquamating. No oral lesions were seen. He had been given a diagnosis of hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD) and reassured that it would resolve on its own in about 10 days.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Several possible diagnoses for nail disorders came to mind with this patient, including onychomycosis, onychoschizia, onycholysis, and onychomadesis.

Onychomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of the nail that affects toenails more often than fingernails.1 The most common form is distal subungual onychomycosis, which begins distally and slowly migrates proximally through the nail matrix.1 Often onychomycosis affects only a few nails unless the patient is elderly or has comorbid conditions, and the nails rarely separate from the nail bed.

Onychoschizia involves lamellar splitting and peeling of the dorsal surface of the nail plate.2 Usually white discolorations appear on the distal edges of the nail.3 It is more common in women than in men and is often caused by nail dehydration from repeated excessive immersion in water with detergents or recurrent application of nail polish.2 However, the nails do not separate from the nail bed, and usually only the fingernails are involved.

Onycholysis is a nail attachment disorder in which the nail plate distally separates from the nail bed. Areas of separation will appear white or yellow. There are many etiologies for onycholysis, including trauma, psoriasis, fungal infection, and contact irritant reactions.3 It also can be caused by medications and thyroid disease.3,4

Continue to: Onychomadesis

Onychomadesis, sometimes considered a severe form of Beau’s line,5,6 is defined by the spontaneous separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix. Although the nail will initially remain attached, proximal shedding will eventually occur.7 When several nails are involved, a systemic source—such as an acute infection, autoimmune disease, medication, malignancy (eg, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), Kawasaki disease, skin disorders (eg, pemphigus vulgaris or keratosis punctata et planters), or chemotherapy—may be the cause.6-8 If only a few nails are involved, it may be associated with trauma, and in rare cases, onychomadesis can be idiopathic.5,7

In this case, all signs pointed to onychomadesis. All of the patient’s nails were affected (discolored and lifting), his nail loss involved spontaneous proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail matrix, and he had a recent previous infection: HFMD.

DISCUSSION

Onychomadesis is a rare nail-shedding disorder thought to be caused by the temporary arrest of the nail matrix.8 It is a potential late complication of infection, such as HFMD,9 and was first reported in children in Chicago in 2000.10 Since then, onychomadesis has been noted in children in many countries.8 Reports of onychomadesis following HFMD in adults are rare, but it may be underreported because HFMD is more common in children and symptoms are usually minor in adults.11

Molecular studies have associated onychomadesis with coxsackievirus (CV)A6 and CVA10.4 Other serotypes associated with onychomadesis include CVB1, CVB2, CVA5, CVA16, and enteroviruses 71 and 9.4 Most known outbreaks seem to be caused by CVA6.4

No treatment is needed for onychomadesis; physicians can reassure patients that normal nail growth will begin within 1 to 4 months. Because onychomadesis is rare, it does not have its own billing code, so one can use code L60.8 for “Other nail disorders.”12

Our patient was seen in the primary care clinic 3 months after his initial visit. At that time, his nails were no longer discolored and no other abnormalities were present. All of the nails on his fingers and toes were firmly attached and growing normally.

THE TAKEAWAY

The sudden asymptomatic loss of multiple fingernails and toenails—especially with proximal nail shedding—is a rare disorder known as onychomadesis. It can be caused by various etiologies and can be a late complication of HFMD or other viral infections. Onychomadesis should be considered when evaluating older patients, particularly when all of their nails are involved after a viral infection.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jon F. Peters, MD, MS, FAAFP, 14486 SE Lyon Court, Happy Valley, OR 97086; peters-nw@comcast.net

1. Rodgers P, Bassler M. Treating onychomycosis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:663-672, 677-678.