User login

Crusted Scabies Presenting as Erythroderma in a Patient With Iatrogenic Immunosuppression for Treatment of Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis

Scabies is caused by cutaneous ectoparasitic infection by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The infection is highly contagious via direct skin-to-skin contact or indirectly through infested bedding, clothing or fomites.1,2 Scabies occurs at all ages, in all ethnic groups, and at all socioeconomic levels.1 Analysis by the Global Burden of Disease estimates that 200 million individuals have been infected with scabies worldwide. The World Health Organization has declared scabies a neglected tropical disease.3

Crusted scabies is a severe and rare form of scabies, with hyperinfestation of thousands to millions of mites, and more commonly is associated with immunosuppressed states, including HIV and hematologic malignancies.1,2,4 Crusted scabies has a high mortality rate due to sepsis when left untreated.3,5

Occasionally, iatrogenic immunosuppression contributes to the development of crusted scabies.1,2 Iatrogenic immunosuppression leading to crusted scabies most commonly occurs secondary to immunosuppression after bone marrow or solid organ transplantation.6 Less often, crusted scabies is caused by iatrogenic immunosuppression from other clinical scenarios.1,2

We describe a patient with iatrogenic immunosuppression due to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression for the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) who developed crusted scabies that clinically presented as erythroderma. Crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma, especially in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression, for timely and appropriate management.

Case Report

An 84-year-old man presented with worsening pruritus, erythema, and thick yellow scale that progressed to erythroderma over the last 2 weeks. He was diagnosed with GPA 6 months prior to presentation and was treated with azathioprine 150 mg/d, prednisone 10 mg/d, and sulfamethoxazole 800 mg plus trimethoprim 160 mg twice weekly for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

Three weeks prior to presentation, the patient was hospitalized for pancytopenia attributed to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression (hemoglobin, 6.1 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–18.0 g/dL]; hematocrit, 17.5% [reference range, 42%–52%]; white blood cell count, 1.66×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.5×103/μL]; platelet count, 146×103/μL [reference range, 150–450×103/μL]; absolute neutrophil count, 1.29×103/μL [reference range, 1.4–6.5×103/μL]). He was transferred to a skilled nursing facility after discharge and referred to dermatology for evaluation of the worsening pruritic rash.

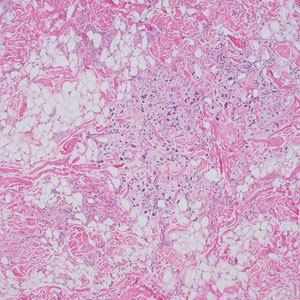

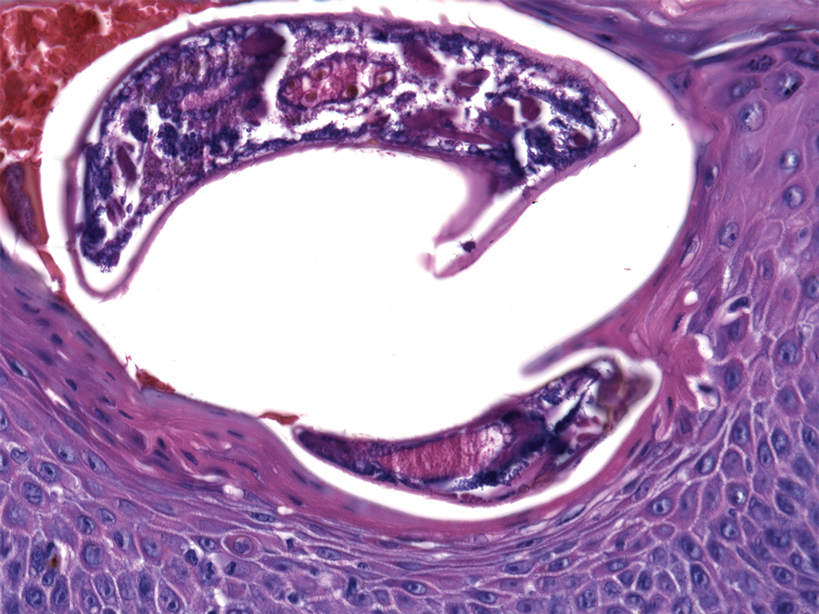

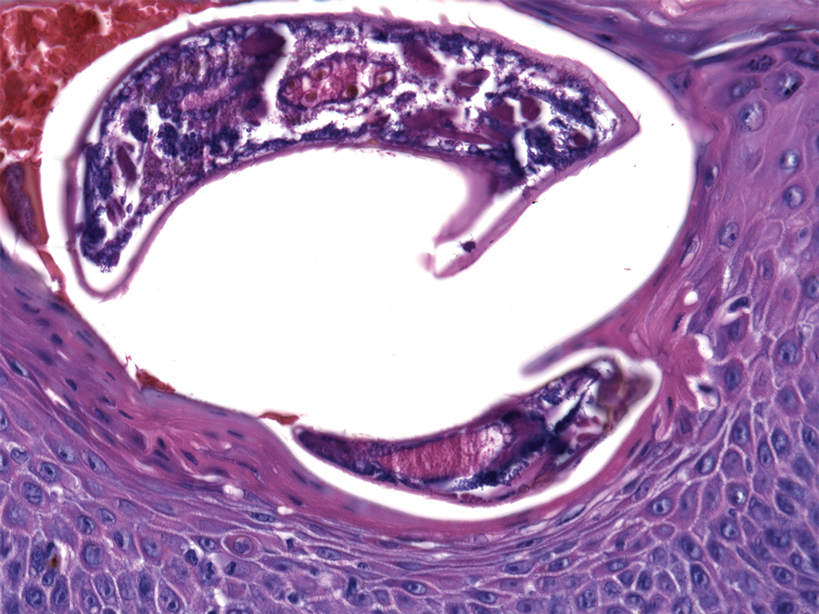

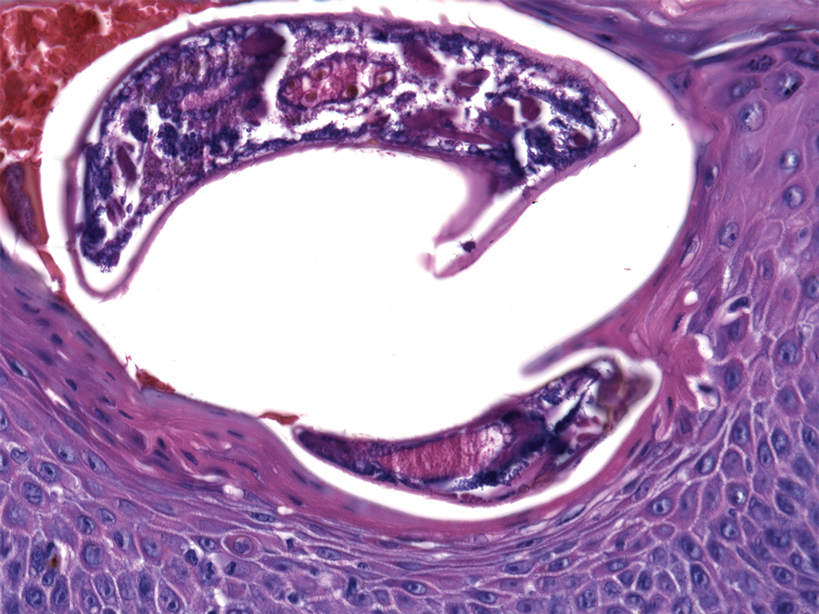

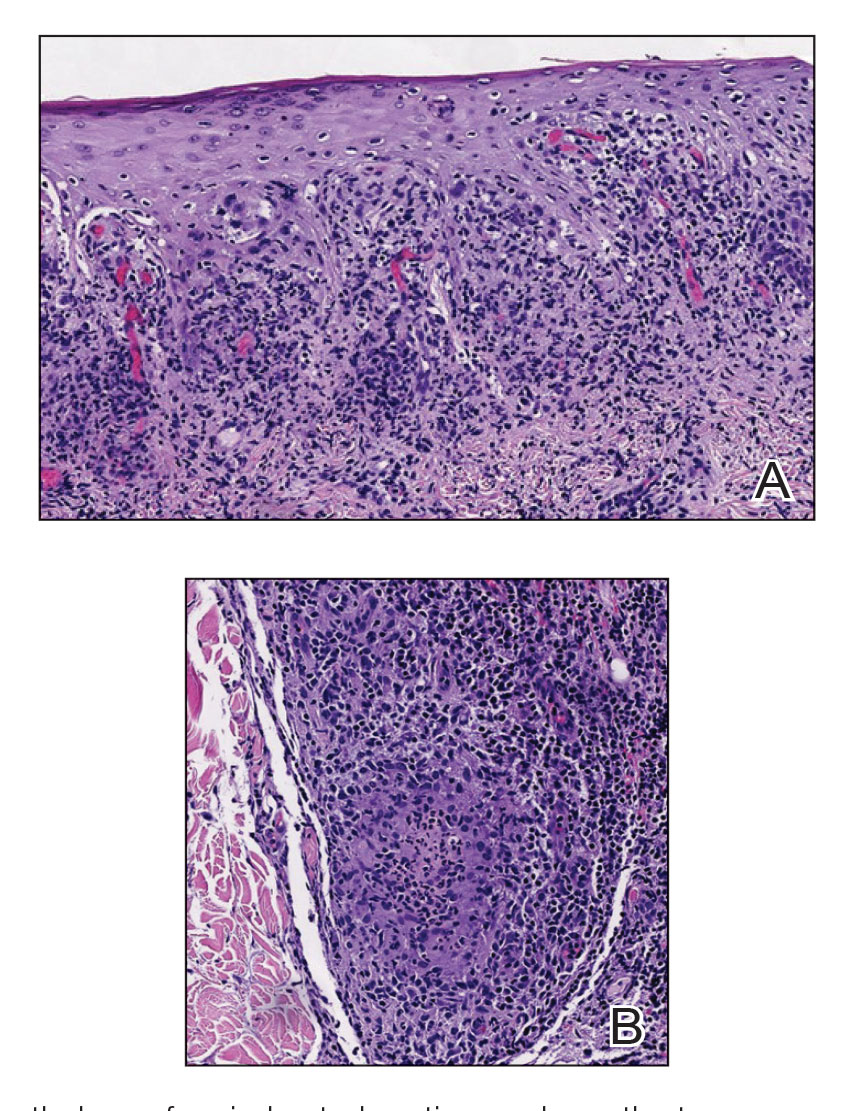

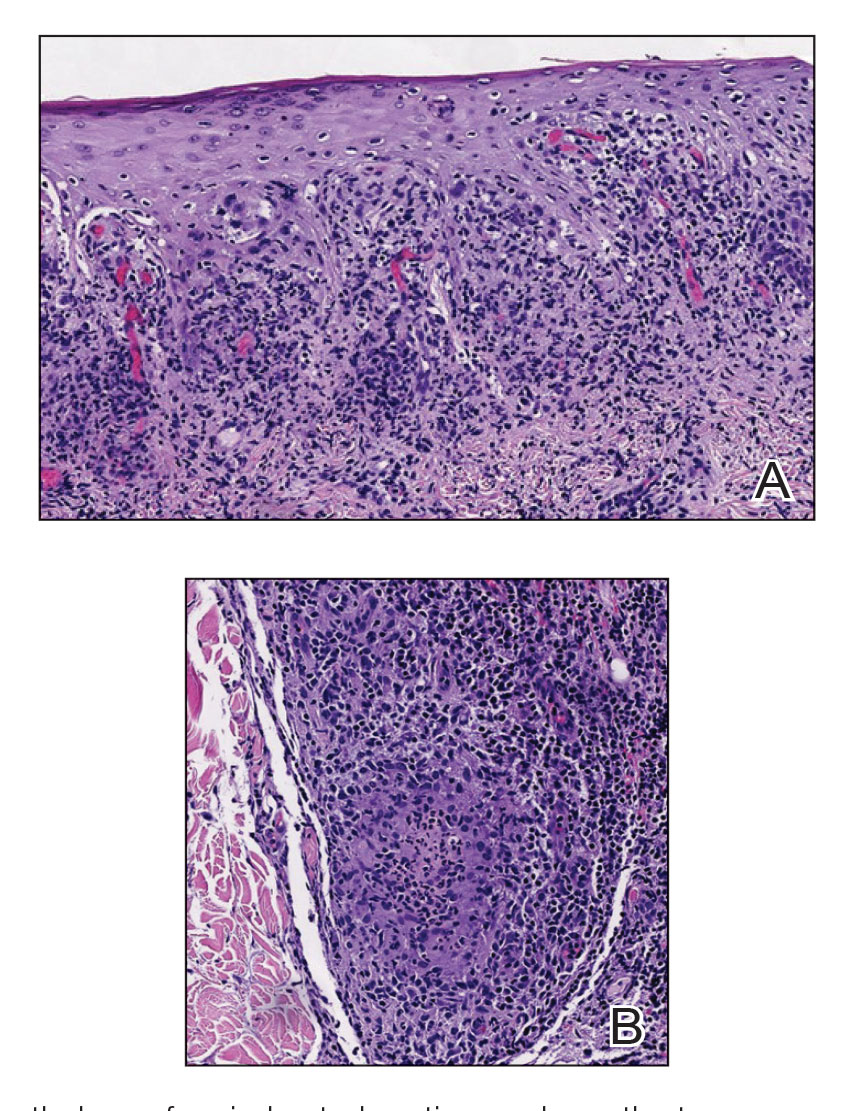

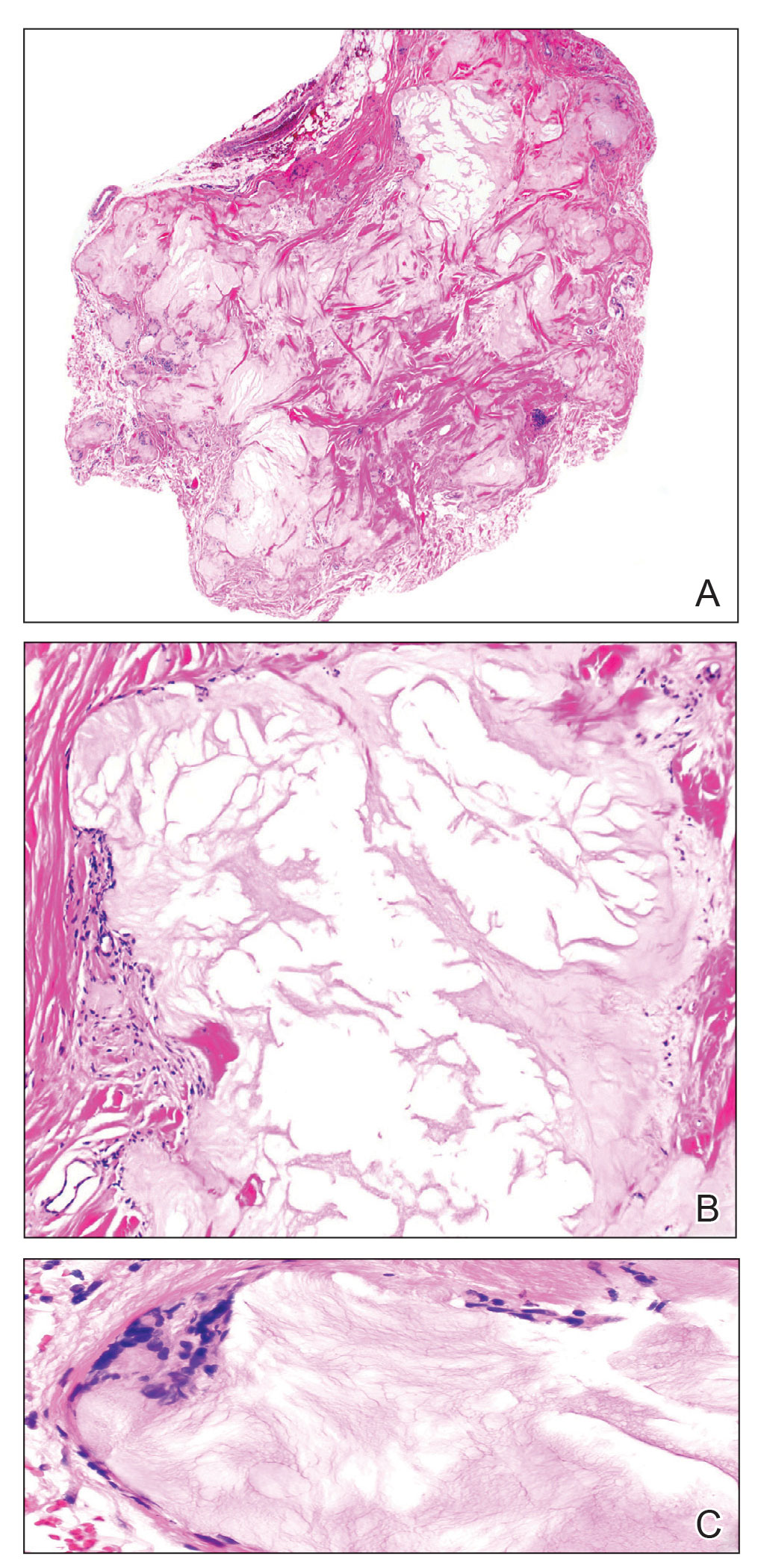

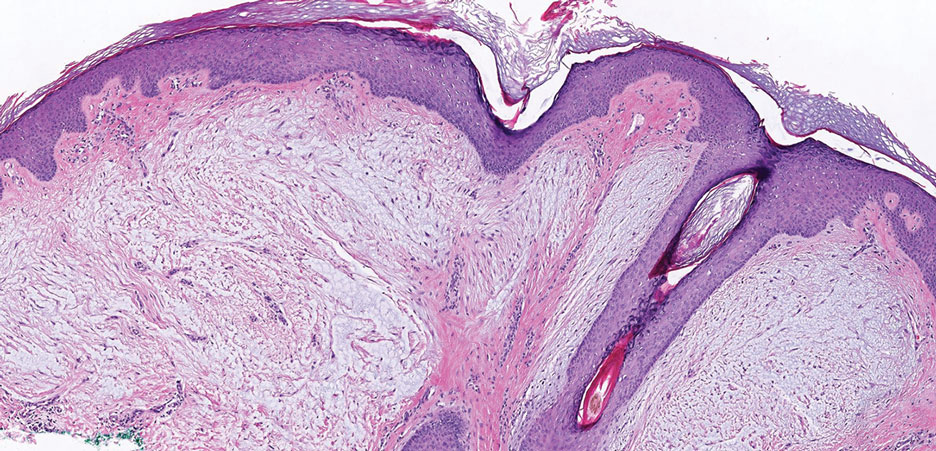

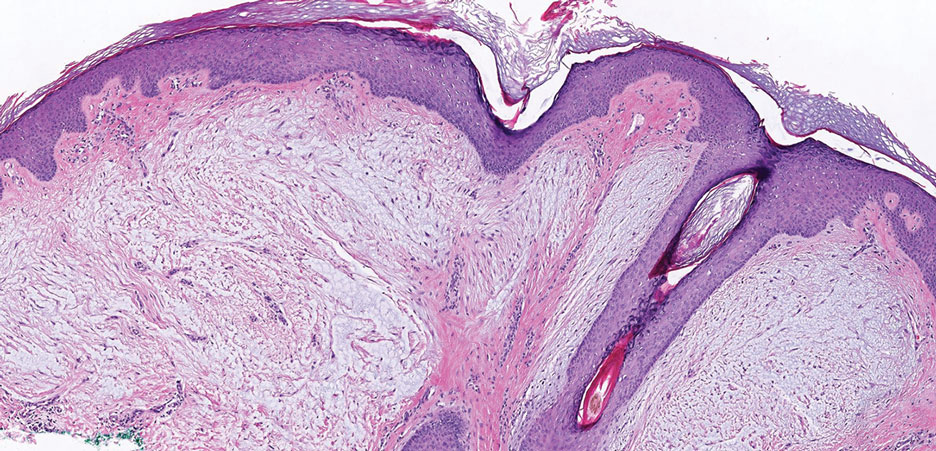

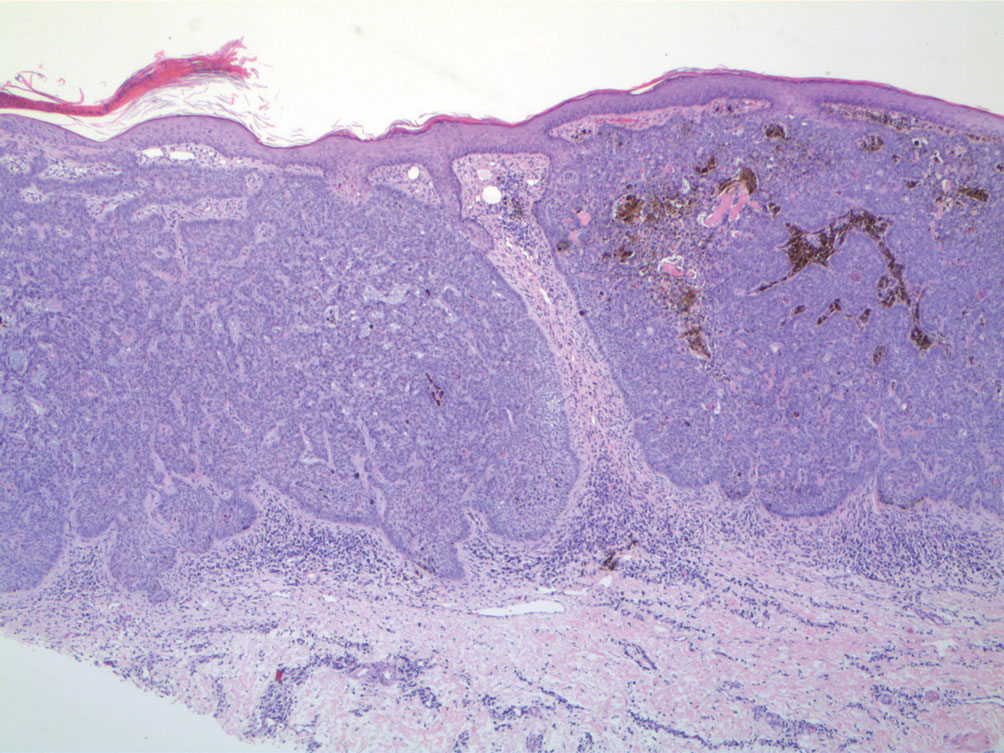

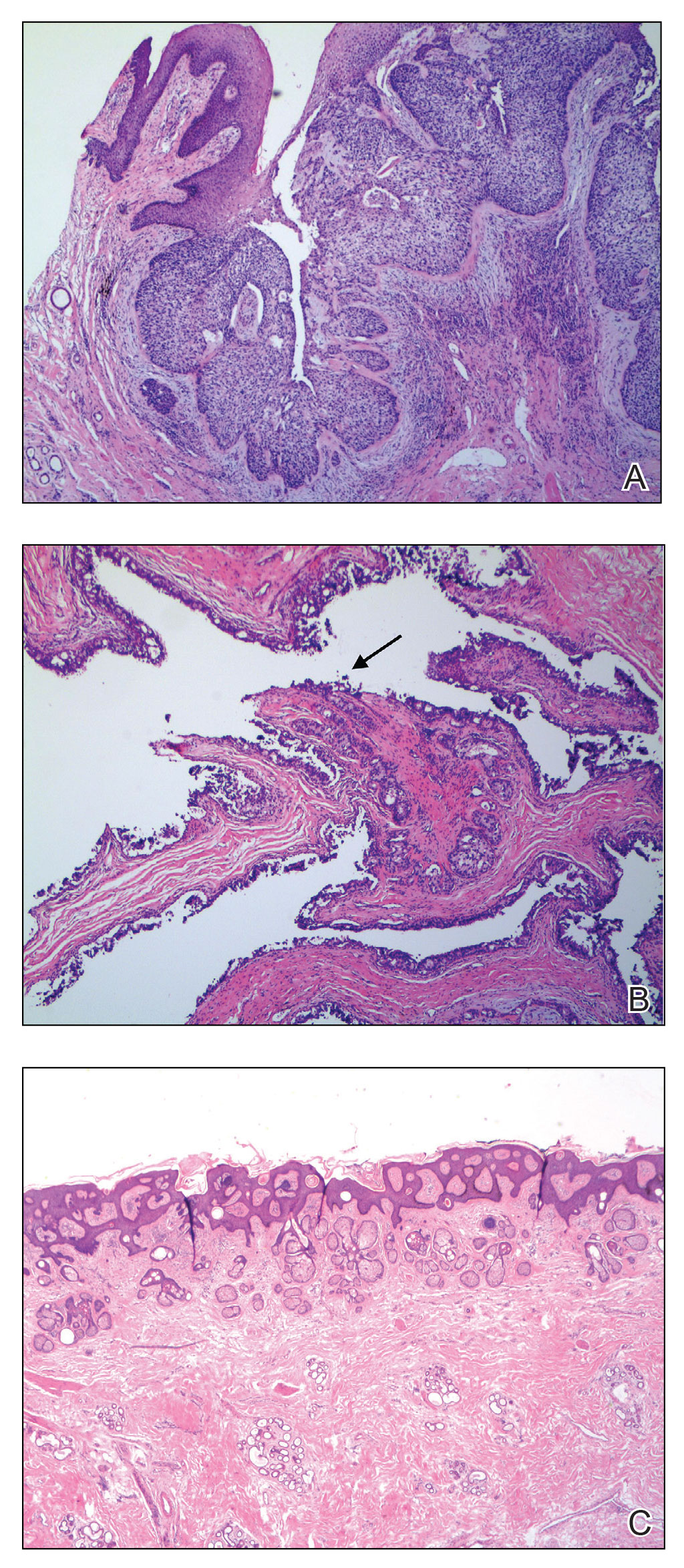

At the current presentation, the patient denied close contact with anyone who had a similar rash at home or at the skilled nursing facility. Physical examination revealed diffuse erythroderma with yellow scale on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs (Figure 1). The palms showed scattered 2- to 3-mm pustules. The mucosal surfaces did not have lesions. A punch biopsy of a pustule from the right arm revealed focal spongiosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis, as well as a perivascular and interstitial mixed inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophils. Organisms morphologically compatible with scabies were found in the stratum corneum (Figure 2). Another punch biopsy of a pustule from the right arm was performed for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and was negative for immunoglobulin deposition. Mineral oil preparation from pustules on the palm was positive for mites.

The patient was treated with permethrin cream 5% and oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg on day 1 and day 10. The prednisone dosage was increased from 10 mg/d to 50 mg/d and tapered over 2 weeks to treat the symptomatic rash and GPA. He remains on maintenance rituximab for GPA, without recurrence of scabies.

Comment

Pathogenesis—As an obligate parasite, S scabiei spends its entire life cycle within the host. Impregnated female mites burrow into the epidermis after mating and lay eggs daily for 1 to 2 months. Eggs hatch 2 or 3 days later. Larvae then migrate to the skin surface; burrow into the stratum corneum, where they mature into adults; and then mate on the skin surface.1,4

Clinical Presentation and Sequelae—Typically, scabies presents 2 to 6 weeks after initial exposure with generalized and intense itching and inflammatory pruritic papules on the finger webs, wrists, elbows, axillae, buttocks, umbilicus, genitalia, and areolae.1 Burrows are specific for scabies but may not always be present. Often, there are nonspecific secondary lesions, including excoriations, dermatitis, and impetiginization.

Complications of scabies can be severe, with initial colonization and infection of the skin resulting in impetigo and cellulitis. Systematic sequelae from local skin infection include post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, rheumatic fever, and sepsis. Mortality from sepsis in scabies can be high.3,5

Classic Crusted Scabies and Other Variants—Crusted scabies presents with psoriasiform hyperkeratotic plaques involving the hands and feet with potential nail involvement that can become more generalized.1 Alterations in CD4+ T-cell function have been implicated in the development of crusted scabies, in which an excessive helper T cell (TH2) response is elicited against the ectoparasite, which may help explain the intense pruritus of scabies.6 Occasionally, iatrogenic immunosuppression contributes to development of crusted scabies,1 as was the case with our patient. However, it is rare for crusted scabies to present with erythroderma.7

Other atypical presentations of scabies include a seborrheic dermatitis–like presentation in infants, nodular lesions in the groin and axillae in more chronic scabies, and vesicles or bullous lesions.1

Diagnosis—Identification of mites, eggs, or feces is necessary for definitive diagnosis of scabies.8 These materials can be obtained through skin scrapings with mineral oil and observed under light microscopy or direct dermoscopy. Multiple scrapings on many lesions should be performed because failure to identify mites can be common and does not rule out scabies. Dermoscopic examination of active lesions under low power also can be helpful, given that identification of dark brown triangular structures can correspond to visualization of the pigmented anterior section of the mite.9-11 A skin biopsy can help identify mites, but histopathology often shows a nonspecific hypersensitivity reaction.12 Therefore, empiric treatment often is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis of erythroderma is broad and includes a drug eruption; Sézary syndrome; and pre-existing skin diseases, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid. Histopathology is critical to differentiate these diagnoses. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus foliaceus are immunobullous diseases that typically are positive for immunoglobulin deposition on DIF. In rare cases, scabies also can present with bullae and positive DIF test results.13

Treatment—First-line treatment of crusted scabies in the United States is permethrin cream 5%, followed by oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg.4,5,14,15 Other scabicides include topicals such as benzyl benzoate 10% to 25%; precipitated sulfur 2% to 10%; crotamiton 10%; malathion 0.5%; and lindane 1%.5 The association of neurotoxicity with lindane has considerably reduced the drug’s use.1

During treatment of scabies, it is important to isolate patients to mitigate the possibility of spread.4 Pruritus can persist for a few weeks after completion of therapy.5 Patients should be closely monitored to ensure that this symptom is secondary to skin inflammation and not incomplete treatment.

Treatment of crusted scabies may require repeated treatments to decrease the notable mite burden as well as the associated crusting and scale. Adding a keratolytic such as 5% to 10% salicylic acid in petrolatum to the treatment regimen may be useful for breaking up thick scale.5

Immunosuppression—With numerous immunomodulatory drugs for treating autoimmunity comes an increased risk for iatrogenic immunosuppression that may contribute to the development of crusted scabies.16 In a number of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,17-19 psoriasis,20,21 pemphigus vulgaris,22 systemic lupus erythematosus,23 systemic sclerosis,22,24 bullous pemphigoid,25,26 and dermatomyositis,27 patients have developed crusted scabies secondary to treatment-related immunosuppression. These immunosuppressive therapies include systemic steroids,22-24,26-31 methotrexate,23 infliximab,18 adalimumab,21 toclizumab,19 and etanercept.20 In a case of drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome, the patient developed crusted scabies during long-term use of oral steroids.22

Patients with a malignancy who are being treated with chemotherapy also can develop crusted scabies.28 Crusted scabies has even been associated with long-term topical steroid32-34 and topical calcineurin inhibitor use.16

Iatrogenic immunosuppression in our patient resulted from treatment of GPA with azathioprine, an immunosuppressive drug that acts as an antagonist of the breakdown of purines, leading to inhibition of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis.35 On occasion, azathioprine can induce immunosuppression in the form of myelosuppression and resulting pancytopenia, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

Although scabies is designated as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization, it still causes a notable burden worldwide, regardless of the economics. Our case highlights an unusual presentation of scabies as erythroderma in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression from azathioprine use. Dermatologists should consider crusted scabies in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma, especially in immunocompromised patients, to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment. Immunosuppressive therapy is an important mainstay in the treatment of many conditions, but it is important to consider that these medications can place patients at an increased risk for rare opportunistic infections. Therefore, patients receiving such treatment should be closely monitored.

- Chosidow O. Clinical practices. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1718-1727. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp052784

- Salgado F, Elston DM. What’s eating you? scabies in the developing world. Cutis. 2017;100:287-289.

- Karimkhani C, Colombara DV, Drucker AM, et al. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1247-1254. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

- Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:717-725. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0910329

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2004.08.033

- Wang X-D, Shen H, Liu Z-H. Contagious erythroderma. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:180-181. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.05.027

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.010

- Bollea Garlatti LA, Torre AC, Bollea Garlatti ML, et al.. Dermoscopy aids the diagnosis of crusted scabies in an erythrodermic patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:E93-E95. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.04.061

- Tang J, You Z, Ran Y. Simple methods to enhance the diagnosis of scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E99-E100. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.038

- Falk ES, Eide TJ. Histologic and clinical findings in human scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:600-605. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1981.tb00844.x

- Shahab RKA, Loo DS. Bullous scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:346-350. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00876-4

- Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD000320. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000320.pub2

- Rosumeck S, Nast A, Dressler C. Evaluation of ivermectin vs permethrin for treating scabies—summary of a Cochrane Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:730-732. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0279

- Ruiz-Maldonado R. Pimecrolimus related crusted scabies in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:299-300. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00241.x

- Bu X, Fan J, Hu X, et al. Norwegian scabies in a patient treated with Tripterygium glycoside for rheumatoid arthritis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:556-558. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174946

- Pipitone MA, Adams B, Sheth A, et al. Crusted scabies in a patient being treated with infliximab for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:719-720. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.12.039

- Baccouche K, Sellam J, Guegan S, et al. Crusted Norwegian scabies, an opportunistic infection, with tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:402-404. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.02.008

- Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:E138-E139. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.049

- Belvisi V, Orsi GB, Del Borgo C, et al. Large nosocomial outbreakassociated with a Norwegian scabies index case undergoing TNF-α inhibitor treatment: management and control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1358-1360. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.188

- Nofal A. Variable response of crusted scabies to oral ivermectin: report on eight Egyptian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:793-797. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03177.x

- Yee BE, Carlos CA, Hata T. Crusted scabies of the scalp in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt9dm891gd.

- Bumb RA, Mehta RD. Crusted scabies in a patient of systemic sclerosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:143-144.

- Hylwa SA, Loss L, Grassi M. Crusted scabies and tinea corporis after treatment of presumed bullous pemphigoid. Cutis. 2013;92:193-198.

- Svecova D, Chmurova N, Pallova A, et al. Norwegian scabies in immunosuppressed patient misdiagnosed as an adverse drug reaction. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2009;58:121-123.

- Dourmishev AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmishev LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00330.x

- Mortazavi H, Abedini R, Sadri F, et al. Crusted scabies in a patient with brain astrocytoma: report of a case. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E526-E527. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.06.011

- Lima FCDR, Cerqueira AMM, MBS, et al. Crusted scabies due to indiscriminate use of glucocorticoid therapy in infant. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:383-385. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174433

- Binic´ I, Jankovic´ A, Jovanovic´ D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191. doi:10.3346/jkms.2010.25.1.188

- Ohtaki N, Taniguchi H, Ohtomo H. Oral ivermectin treatment in two cases of scabies: effective in crusted scabies induced by corticosteroid but ineffective in nail scabies. J Dermatol. 2003;30:411-416. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00408.x

- Bilan P, Colin-Gorski AM, Chapelon E, et al. Crusted scabies induced by topical corticosteroids: a case report [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2015;22:1292-1294. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2015.09.004

- Marlière V, Roul S, C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70342-2

- Jaramillo-Ayerbe F, J. Ivermectin for crusted Norwegian scabies induced by use of topical steroids. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:143-145. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.2.143

- Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Science. 1989;244:41-47. doi:10.1126/science.2649979

Scabies is caused by cutaneous ectoparasitic infection by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The infection is highly contagious via direct skin-to-skin contact or indirectly through infested bedding, clothing or fomites.1,2 Scabies occurs at all ages, in all ethnic groups, and at all socioeconomic levels.1 Analysis by the Global Burden of Disease estimates that 200 million individuals have been infected with scabies worldwide. The World Health Organization has declared scabies a neglected tropical disease.3

Crusted scabies is a severe and rare form of scabies, with hyperinfestation of thousands to millions of mites, and more commonly is associated with immunosuppressed states, including HIV and hematologic malignancies.1,2,4 Crusted scabies has a high mortality rate due to sepsis when left untreated.3,5

Occasionally, iatrogenic immunosuppression contributes to the development of crusted scabies.1,2 Iatrogenic immunosuppression leading to crusted scabies most commonly occurs secondary to immunosuppression after bone marrow or solid organ transplantation.6 Less often, crusted scabies is caused by iatrogenic immunosuppression from other clinical scenarios.1,2

We describe a patient with iatrogenic immunosuppression due to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression for the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) who developed crusted scabies that clinically presented as erythroderma. Crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma, especially in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression, for timely and appropriate management.

Case Report

An 84-year-old man presented with worsening pruritus, erythema, and thick yellow scale that progressed to erythroderma over the last 2 weeks. He was diagnosed with GPA 6 months prior to presentation and was treated with azathioprine 150 mg/d, prednisone 10 mg/d, and sulfamethoxazole 800 mg plus trimethoprim 160 mg twice weekly for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

Three weeks prior to presentation, the patient was hospitalized for pancytopenia attributed to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression (hemoglobin, 6.1 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–18.0 g/dL]; hematocrit, 17.5% [reference range, 42%–52%]; white blood cell count, 1.66×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.5×103/μL]; platelet count, 146×103/μL [reference range, 150–450×103/μL]; absolute neutrophil count, 1.29×103/μL [reference range, 1.4–6.5×103/μL]). He was transferred to a skilled nursing facility after discharge and referred to dermatology for evaluation of the worsening pruritic rash.

At the current presentation, the patient denied close contact with anyone who had a similar rash at home or at the skilled nursing facility. Physical examination revealed diffuse erythroderma with yellow scale on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs (Figure 1). The palms showed scattered 2- to 3-mm pustules. The mucosal surfaces did not have lesions. A punch biopsy of a pustule from the right arm revealed focal spongiosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis, as well as a perivascular and interstitial mixed inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophils. Organisms morphologically compatible with scabies were found in the stratum corneum (Figure 2). Another punch biopsy of a pustule from the right arm was performed for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and was negative for immunoglobulin deposition. Mineral oil preparation from pustules on the palm was positive for mites.

The patient was treated with permethrin cream 5% and oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg on day 1 and day 10. The prednisone dosage was increased from 10 mg/d to 50 mg/d and tapered over 2 weeks to treat the symptomatic rash and GPA. He remains on maintenance rituximab for GPA, without recurrence of scabies.

Comment

Pathogenesis—As an obligate parasite, S scabiei spends its entire life cycle within the host. Impregnated female mites burrow into the epidermis after mating and lay eggs daily for 1 to 2 months. Eggs hatch 2 or 3 days later. Larvae then migrate to the skin surface; burrow into the stratum corneum, where they mature into adults; and then mate on the skin surface.1,4

Clinical Presentation and Sequelae—Typically, scabies presents 2 to 6 weeks after initial exposure with generalized and intense itching and inflammatory pruritic papules on the finger webs, wrists, elbows, axillae, buttocks, umbilicus, genitalia, and areolae.1 Burrows are specific for scabies but may not always be present. Often, there are nonspecific secondary lesions, including excoriations, dermatitis, and impetiginization.

Complications of scabies can be severe, with initial colonization and infection of the skin resulting in impetigo and cellulitis. Systematic sequelae from local skin infection include post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, rheumatic fever, and sepsis. Mortality from sepsis in scabies can be high.3,5

Classic Crusted Scabies and Other Variants—Crusted scabies presents with psoriasiform hyperkeratotic plaques involving the hands and feet with potential nail involvement that can become more generalized.1 Alterations in CD4+ T-cell function have been implicated in the development of crusted scabies, in which an excessive helper T cell (TH2) response is elicited against the ectoparasite, which may help explain the intense pruritus of scabies.6 Occasionally, iatrogenic immunosuppression contributes to development of crusted scabies,1 as was the case with our patient. However, it is rare for crusted scabies to present with erythroderma.7

Other atypical presentations of scabies include a seborrheic dermatitis–like presentation in infants, nodular lesions in the groin and axillae in more chronic scabies, and vesicles or bullous lesions.1

Diagnosis—Identification of mites, eggs, or feces is necessary for definitive diagnosis of scabies.8 These materials can be obtained through skin scrapings with mineral oil and observed under light microscopy or direct dermoscopy. Multiple scrapings on many lesions should be performed because failure to identify mites can be common and does not rule out scabies. Dermoscopic examination of active lesions under low power also can be helpful, given that identification of dark brown triangular structures can correspond to visualization of the pigmented anterior section of the mite.9-11 A skin biopsy can help identify mites, but histopathology often shows a nonspecific hypersensitivity reaction.12 Therefore, empiric treatment often is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis of erythroderma is broad and includes a drug eruption; Sézary syndrome; and pre-existing skin diseases, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid. Histopathology is critical to differentiate these diagnoses. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus foliaceus are immunobullous diseases that typically are positive for immunoglobulin deposition on DIF. In rare cases, scabies also can present with bullae and positive DIF test results.13

Treatment—First-line treatment of crusted scabies in the United States is permethrin cream 5%, followed by oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg.4,5,14,15 Other scabicides include topicals such as benzyl benzoate 10% to 25%; precipitated sulfur 2% to 10%; crotamiton 10%; malathion 0.5%; and lindane 1%.5 The association of neurotoxicity with lindane has considerably reduced the drug’s use.1

During treatment of scabies, it is important to isolate patients to mitigate the possibility of spread.4 Pruritus can persist for a few weeks after completion of therapy.5 Patients should be closely monitored to ensure that this symptom is secondary to skin inflammation and not incomplete treatment.

Treatment of crusted scabies may require repeated treatments to decrease the notable mite burden as well as the associated crusting and scale. Adding a keratolytic such as 5% to 10% salicylic acid in petrolatum to the treatment regimen may be useful for breaking up thick scale.5

Immunosuppression—With numerous immunomodulatory drugs for treating autoimmunity comes an increased risk for iatrogenic immunosuppression that may contribute to the development of crusted scabies.16 In a number of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,17-19 psoriasis,20,21 pemphigus vulgaris,22 systemic lupus erythematosus,23 systemic sclerosis,22,24 bullous pemphigoid,25,26 and dermatomyositis,27 patients have developed crusted scabies secondary to treatment-related immunosuppression. These immunosuppressive therapies include systemic steroids,22-24,26-31 methotrexate,23 infliximab,18 adalimumab,21 toclizumab,19 and etanercept.20 In a case of drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome, the patient developed crusted scabies during long-term use of oral steroids.22

Patients with a malignancy who are being treated with chemotherapy also can develop crusted scabies.28 Crusted scabies has even been associated with long-term topical steroid32-34 and topical calcineurin inhibitor use.16

Iatrogenic immunosuppression in our patient resulted from treatment of GPA with azathioprine, an immunosuppressive drug that acts as an antagonist of the breakdown of purines, leading to inhibition of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis.35 On occasion, azathioprine can induce immunosuppression in the form of myelosuppression and resulting pancytopenia, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

Although scabies is designated as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization, it still causes a notable burden worldwide, regardless of the economics. Our case highlights an unusual presentation of scabies as erythroderma in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression from azathioprine use. Dermatologists should consider crusted scabies in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma, especially in immunocompromised patients, to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment. Immunosuppressive therapy is an important mainstay in the treatment of many conditions, but it is important to consider that these medications can place patients at an increased risk for rare opportunistic infections. Therefore, patients receiving such treatment should be closely monitored.

Scabies is caused by cutaneous ectoparasitic infection by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The infection is highly contagious via direct skin-to-skin contact or indirectly through infested bedding, clothing or fomites.1,2 Scabies occurs at all ages, in all ethnic groups, and at all socioeconomic levels.1 Analysis by the Global Burden of Disease estimates that 200 million individuals have been infected with scabies worldwide. The World Health Organization has declared scabies a neglected tropical disease.3

Crusted scabies is a severe and rare form of scabies, with hyperinfestation of thousands to millions of mites, and more commonly is associated with immunosuppressed states, including HIV and hematologic malignancies.1,2,4 Crusted scabies has a high mortality rate due to sepsis when left untreated.3,5

Occasionally, iatrogenic immunosuppression contributes to the development of crusted scabies.1,2 Iatrogenic immunosuppression leading to crusted scabies most commonly occurs secondary to immunosuppression after bone marrow or solid organ transplantation.6 Less often, crusted scabies is caused by iatrogenic immunosuppression from other clinical scenarios.1,2

We describe a patient with iatrogenic immunosuppression due to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression for the treatment of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) who developed crusted scabies that clinically presented as erythroderma. Crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma, especially in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression, for timely and appropriate management.

Case Report

An 84-year-old man presented with worsening pruritus, erythema, and thick yellow scale that progressed to erythroderma over the last 2 weeks. He was diagnosed with GPA 6 months prior to presentation and was treated with azathioprine 150 mg/d, prednisone 10 mg/d, and sulfamethoxazole 800 mg plus trimethoprim 160 mg twice weekly for prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia.

Three weeks prior to presentation, the patient was hospitalized for pancytopenia attributed to azathioprine-induced myelosuppression (hemoglobin, 6.1 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–18.0 g/dL]; hematocrit, 17.5% [reference range, 42%–52%]; white blood cell count, 1.66×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.5×103/μL]; platelet count, 146×103/μL [reference range, 150–450×103/μL]; absolute neutrophil count, 1.29×103/μL [reference range, 1.4–6.5×103/μL]). He was transferred to a skilled nursing facility after discharge and referred to dermatology for evaluation of the worsening pruritic rash.

At the current presentation, the patient denied close contact with anyone who had a similar rash at home or at the skilled nursing facility. Physical examination revealed diffuse erythroderma with yellow scale on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs (Figure 1). The palms showed scattered 2- to 3-mm pustules. The mucosal surfaces did not have lesions. A punch biopsy of a pustule from the right arm revealed focal spongiosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis, as well as a perivascular and interstitial mixed inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophils. Organisms morphologically compatible with scabies were found in the stratum corneum (Figure 2). Another punch biopsy of a pustule from the right arm was performed for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and was negative for immunoglobulin deposition. Mineral oil preparation from pustules on the palm was positive for mites.

The patient was treated with permethrin cream 5% and oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg on day 1 and day 10. The prednisone dosage was increased from 10 mg/d to 50 mg/d and tapered over 2 weeks to treat the symptomatic rash and GPA. He remains on maintenance rituximab for GPA, without recurrence of scabies.

Comment

Pathogenesis—As an obligate parasite, S scabiei spends its entire life cycle within the host. Impregnated female mites burrow into the epidermis after mating and lay eggs daily for 1 to 2 months. Eggs hatch 2 or 3 days later. Larvae then migrate to the skin surface; burrow into the stratum corneum, where they mature into adults; and then mate on the skin surface.1,4

Clinical Presentation and Sequelae—Typically, scabies presents 2 to 6 weeks after initial exposure with generalized and intense itching and inflammatory pruritic papules on the finger webs, wrists, elbows, axillae, buttocks, umbilicus, genitalia, and areolae.1 Burrows are specific for scabies but may not always be present. Often, there are nonspecific secondary lesions, including excoriations, dermatitis, and impetiginization.

Complications of scabies can be severe, with initial colonization and infection of the skin resulting in impetigo and cellulitis. Systematic sequelae from local skin infection include post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, rheumatic fever, and sepsis. Mortality from sepsis in scabies can be high.3,5

Classic Crusted Scabies and Other Variants—Crusted scabies presents with psoriasiform hyperkeratotic plaques involving the hands and feet with potential nail involvement that can become more generalized.1 Alterations in CD4+ T-cell function have been implicated in the development of crusted scabies, in which an excessive helper T cell (TH2) response is elicited against the ectoparasite, which may help explain the intense pruritus of scabies.6 Occasionally, iatrogenic immunosuppression contributes to development of crusted scabies,1 as was the case with our patient. However, it is rare for crusted scabies to present with erythroderma.7

Other atypical presentations of scabies include a seborrheic dermatitis–like presentation in infants, nodular lesions in the groin and axillae in more chronic scabies, and vesicles or bullous lesions.1

Diagnosis—Identification of mites, eggs, or feces is necessary for definitive diagnosis of scabies.8 These materials can be obtained through skin scrapings with mineral oil and observed under light microscopy or direct dermoscopy. Multiple scrapings on many lesions should be performed because failure to identify mites can be common and does not rule out scabies. Dermoscopic examination of active lesions under low power also can be helpful, given that identification of dark brown triangular structures can correspond to visualization of the pigmented anterior section of the mite.9-11 A skin biopsy can help identify mites, but histopathology often shows a nonspecific hypersensitivity reaction.12 Therefore, empiric treatment often is necessary.

Differential Diagnosis—The differential diagnosis of erythroderma is broad and includes a drug eruption; Sézary syndrome; and pre-existing skin diseases, including psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pemphigus foliaceus, and bullous pemphigoid. Histopathology is critical to differentiate these diagnoses. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus foliaceus are immunobullous diseases that typically are positive for immunoglobulin deposition on DIF. In rare cases, scabies also can present with bullae and positive DIF test results.13

Treatment—First-line treatment of crusted scabies in the United States is permethrin cream 5%, followed by oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg.4,5,14,15 Other scabicides include topicals such as benzyl benzoate 10% to 25%; precipitated sulfur 2% to 10%; crotamiton 10%; malathion 0.5%; and lindane 1%.5 The association of neurotoxicity with lindane has considerably reduced the drug’s use.1

During treatment of scabies, it is important to isolate patients to mitigate the possibility of spread.4 Pruritus can persist for a few weeks after completion of therapy.5 Patients should be closely monitored to ensure that this symptom is secondary to skin inflammation and not incomplete treatment.

Treatment of crusted scabies may require repeated treatments to decrease the notable mite burden as well as the associated crusting and scale. Adding a keratolytic such as 5% to 10% salicylic acid in petrolatum to the treatment regimen may be useful for breaking up thick scale.5

Immunosuppression—With numerous immunomodulatory drugs for treating autoimmunity comes an increased risk for iatrogenic immunosuppression that may contribute to the development of crusted scabies.16 In a number of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,17-19 psoriasis,20,21 pemphigus vulgaris,22 systemic lupus erythematosus,23 systemic sclerosis,22,24 bullous pemphigoid,25,26 and dermatomyositis,27 patients have developed crusted scabies secondary to treatment-related immunosuppression. These immunosuppressive therapies include systemic steroids,22-24,26-31 methotrexate,23 infliximab,18 adalimumab,21 toclizumab,19 and etanercept.20 In a case of drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome, the patient developed crusted scabies during long-term use of oral steroids.22

Patients with a malignancy who are being treated with chemotherapy also can develop crusted scabies.28 Crusted scabies has even been associated with long-term topical steroid32-34 and topical calcineurin inhibitor use.16

Iatrogenic immunosuppression in our patient resulted from treatment of GPA with azathioprine, an immunosuppressive drug that acts as an antagonist of the breakdown of purines, leading to inhibition of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis.35 On occasion, azathioprine can induce immunosuppression in the form of myelosuppression and resulting pancytopenia, as was the case with our patient.

Conclusion

Although scabies is designated as a neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization, it still causes a notable burden worldwide, regardless of the economics. Our case highlights an unusual presentation of scabies as erythroderma in the setting of iatrogenic immunosuppression from azathioprine use. Dermatologists should consider crusted scabies in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma, especially in immunocompromised patients, to avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment. Immunosuppressive therapy is an important mainstay in the treatment of many conditions, but it is important to consider that these medications can place patients at an increased risk for rare opportunistic infections. Therefore, patients receiving such treatment should be closely monitored.

- Chosidow O. Clinical practices. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1718-1727. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp052784

- Salgado F, Elston DM. What’s eating you? scabies in the developing world. Cutis. 2017;100:287-289.

- Karimkhani C, Colombara DV, Drucker AM, et al. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1247-1254. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

- Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:717-725. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0910329

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2004.08.033

- Wang X-D, Shen H, Liu Z-H. Contagious erythroderma. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:180-181. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.05.027

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.010

- Bollea Garlatti LA, Torre AC, Bollea Garlatti ML, et al.. Dermoscopy aids the diagnosis of crusted scabies in an erythrodermic patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:E93-E95. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.04.061

- Tang J, You Z, Ran Y. Simple methods to enhance the diagnosis of scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E99-E100. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.038

- Falk ES, Eide TJ. Histologic and clinical findings in human scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:600-605. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1981.tb00844.x

- Shahab RKA, Loo DS. Bullous scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:346-350. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00876-4

- Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD000320. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000320.pub2

- Rosumeck S, Nast A, Dressler C. Evaluation of ivermectin vs permethrin for treating scabies—summary of a Cochrane Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:730-732. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0279

- Ruiz-Maldonado R. Pimecrolimus related crusted scabies in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:299-300. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00241.x

- Bu X, Fan J, Hu X, et al. Norwegian scabies in a patient treated with Tripterygium glycoside for rheumatoid arthritis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:556-558. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174946

- Pipitone MA, Adams B, Sheth A, et al. Crusted scabies in a patient being treated with infliximab for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:719-720. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.12.039

- Baccouche K, Sellam J, Guegan S, et al. Crusted Norwegian scabies, an opportunistic infection, with tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:402-404. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.02.008

- Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:E138-E139. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.049

- Belvisi V, Orsi GB, Del Borgo C, et al. Large nosocomial outbreakassociated with a Norwegian scabies index case undergoing TNF-α inhibitor treatment: management and control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1358-1360. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.188

- Nofal A. Variable response of crusted scabies to oral ivermectin: report on eight Egyptian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:793-797. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03177.x

- Yee BE, Carlos CA, Hata T. Crusted scabies of the scalp in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt9dm891gd.

- Bumb RA, Mehta RD. Crusted scabies in a patient of systemic sclerosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:143-144.

- Hylwa SA, Loss L, Grassi M. Crusted scabies and tinea corporis after treatment of presumed bullous pemphigoid. Cutis. 2013;92:193-198.

- Svecova D, Chmurova N, Pallova A, et al. Norwegian scabies in immunosuppressed patient misdiagnosed as an adverse drug reaction. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2009;58:121-123.

- Dourmishev AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmishev LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00330.x

- Mortazavi H, Abedini R, Sadri F, et al. Crusted scabies in a patient with brain astrocytoma: report of a case. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E526-E527. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.06.011

- Lima FCDR, Cerqueira AMM, MBS, et al. Crusted scabies due to indiscriminate use of glucocorticoid therapy in infant. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:383-385. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174433

- Binic´ I, Jankovic´ A, Jovanovic´ D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191. doi:10.3346/jkms.2010.25.1.188

- Ohtaki N, Taniguchi H, Ohtomo H. Oral ivermectin treatment in two cases of scabies: effective in crusted scabies induced by corticosteroid but ineffective in nail scabies. J Dermatol. 2003;30:411-416. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00408.x

- Bilan P, Colin-Gorski AM, Chapelon E, et al. Crusted scabies induced by topical corticosteroids: a case report [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2015;22:1292-1294. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2015.09.004

- Marlière V, Roul S, C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70342-2

- Jaramillo-Ayerbe F, J. Ivermectin for crusted Norwegian scabies induced by use of topical steroids. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:143-145. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.2.143

- Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Science. 1989;244:41-47. doi:10.1126/science.2649979

- Chosidow O. Clinical practices. Scabies. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1718-1727. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp052784

- Salgado F, Elston DM. What’s eating you? scabies in the developing world. Cutis. 2017;100:287-289.

- Karimkhani C, Colombara DV, Drucker AM, et al. The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1247-1254. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

- Currie BJ, McCarthy JS. Permethrin and ivermectin for scabies. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:717-725. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0910329

- Thomas C, Coates SJ, Engelman D, et al. Ectoparasites: scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:533-548. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.109

- Roberts LJ, Huffam SE, Walton SF, et al. Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;50:375-381. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2004.08.033

- Wang X-D, Shen H, Liu Z-H. Contagious erythroderma. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:180-181. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.05.027

- Johnston G, Sladden M. Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ. 2005;331:619-622. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

- Micali G, Lacarrubba F, Massimino D, et al. Dermatoscopy: alternative uses in daily clinical practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1135-1146. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.010

- Bollea Garlatti LA, Torre AC, Bollea Garlatti ML, et al.. Dermoscopy aids the diagnosis of crusted scabies in an erythrodermic patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:E93-E95. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.04.061

- Tang J, You Z, Ran Y. Simple methods to enhance the diagnosis of scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:E99-E100. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.07.038

- Falk ES, Eide TJ. Histologic and clinical findings in human scabies. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:600-605. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1981.tb00844.x

- Shahab RKA, Loo DS. Bullous scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:346-350. doi:10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00876-4

- Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD000320. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000320.pub2

- Rosumeck S, Nast A, Dressler C. Evaluation of ivermectin vs permethrin for treating scabies—summary of a Cochrane Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:730-732. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0279

- Ruiz-Maldonado R. Pimecrolimus related crusted scabies in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:299-300. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2006.00241.x

- Bu X, Fan J, Hu X, et al. Norwegian scabies in a patient treated with Tripterygium glycoside for rheumatoid arthritis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:556-558. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174946

- Pipitone MA, Adams B, Sheth A, et al. Crusted scabies in a patient being treated with infliximab for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:719-720. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.12.039

- Baccouche K, Sellam J, Guegan S, et al. Crusted Norwegian scabies, an opportunistic infection, with tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2011;78:402-404. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.02.008

- Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:E138-E139. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.049

- Belvisi V, Orsi GB, Del Borgo C, et al. Large nosocomial outbreakassociated with a Norwegian scabies index case undergoing TNF-α inhibitor treatment: management and control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36:1358-1360. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.188

- Nofal A. Variable response of crusted scabies to oral ivermectin: report on eight Egyptian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:793-797. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03177.x

- Yee BE, Carlos CA, Hata T. Crusted scabies of the scalp in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt9dm891gd.

- Bumb RA, Mehta RD. Crusted scabies in a patient of systemic sclerosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2000;66:143-144.

- Hylwa SA, Loss L, Grassi M. Crusted scabies and tinea corporis after treatment of presumed bullous pemphigoid. Cutis. 2013;92:193-198.

- Svecova D, Chmurova N, Pallova A, et al. Norwegian scabies in immunosuppressed patient misdiagnosed as an adverse drug reaction. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2009;58:121-123.

- Dourmishev AL, Serafimova DK, Dourmishev LA, et al. Crusted scabies of the scalp in dermatomyositis patients: three cases treated with oral ivermectin. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:231-234. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00330.x

- Mortazavi H, Abedini R, Sadri F, et al. Crusted scabies in a patient with brain astrocytoma: report of a case. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:E526-E527. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.06.011

- Lima FCDR, Cerqueira AMM, MBS, et al. Crusted scabies due to indiscriminate use of glucocorticoid therapy in infant. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:383-385. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174433

- Binic´ I, Jankovic´ A, Jovanovic´ D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191. doi:10.3346/jkms.2010.25.1.188

- Ohtaki N, Taniguchi H, Ohtomo H. Oral ivermectin treatment in two cases of scabies: effective in crusted scabies induced by corticosteroid but ineffective in nail scabies. J Dermatol. 2003;30:411-416. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00408.x

- Bilan P, Colin-Gorski AM, Chapelon E, et al. Crusted scabies induced by topical corticosteroids: a case report [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2015;22:1292-1294. doi:10.1016/j.arcped.2015.09.004

- Marlière V, Roul S, C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70342-2

- Jaramillo-Ayerbe F, J. Ivermectin for crusted Norwegian scabies induced by use of topical steroids. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:143-145. doi:10.1001/archderm.134.2.143

- Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Science. 1989;244:41-47. doi:10.1126/science.2649979

Practice Points

- Crusted scabies is a highly contagious, severe cutaneous ectoparasitic infection that can present atypically in the form of erythroderma.

- Immunomodulatory drugs for the treatment of autoimmune disease can predispose patients to infection, including ectoparasitic infection.

- Dermatologists should be familiar with the full scope of the clinical presentations of scabies and should especially consider this condition in the differential diagnosis of patients who present in an immunosuppressed state.

Primary Effusion Lymphoma: An Infiltrative Plaque in a Patient With HIV

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented to the dermatology service with an asymptomatic plaque on the right thigh of 2 months’ duration. He had a medical history of HIV and Kaposi sarcoma as well as a recently relapsed primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) subsequent to an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. He initially was diagnosed with PEL 3 years prior to the current presentation during a workup for fever and weight loss. Imaging at the time demonstrated a bladder mass, which was biopsied and demonstrated PEL. Further imaging demonstrated both sinus and bone marrow involvement. Prior to dermatologic consultation, he had been treated with 6 cycles of etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH); 6 cycles of brentuximab; 4 cycles of rituximab with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin; and 2 cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide. Despite these therapies, he had 3 relapses, and oncology determined the need for a matched unrelated donor allogeneic stem cell transplant for his PEL.

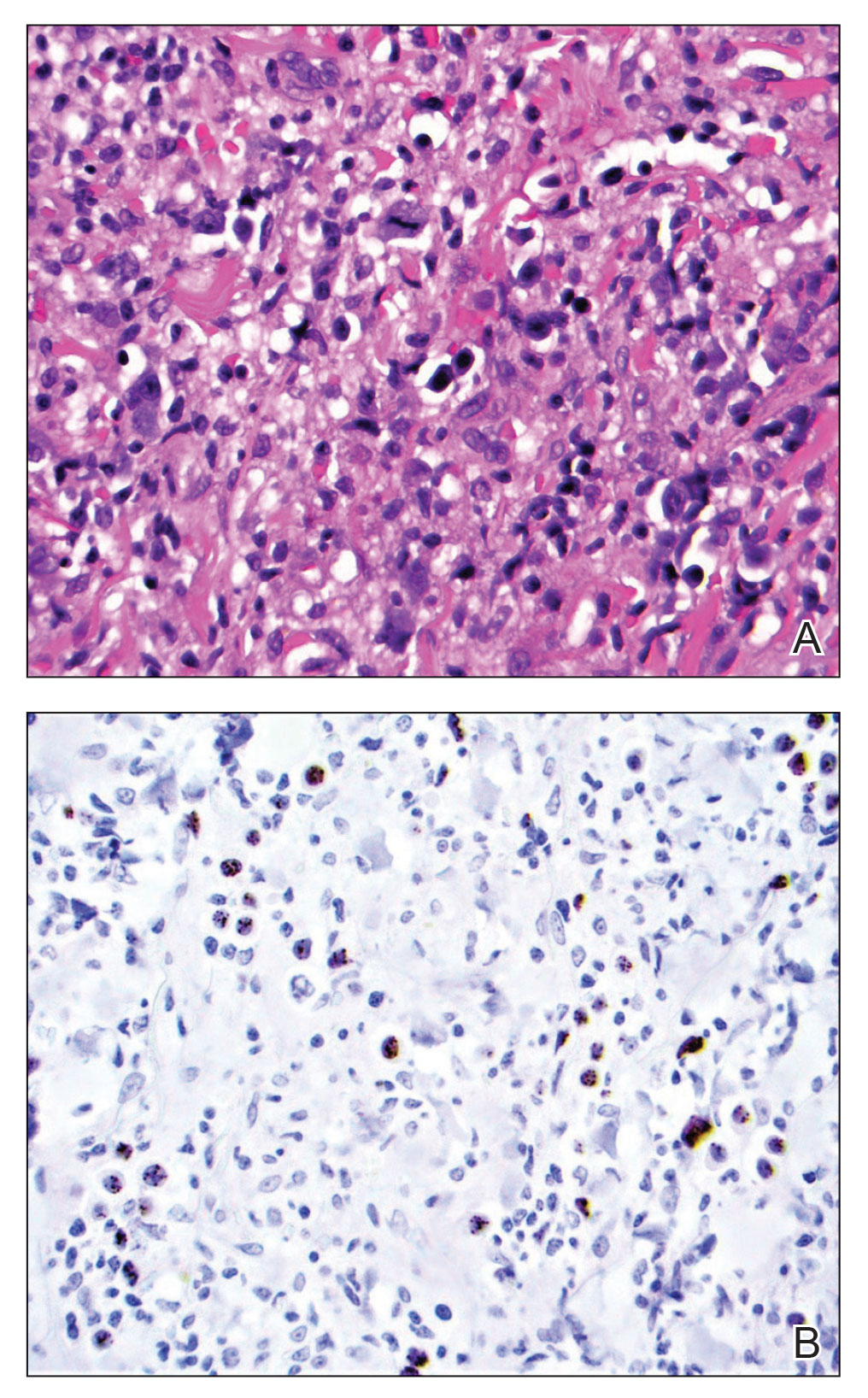

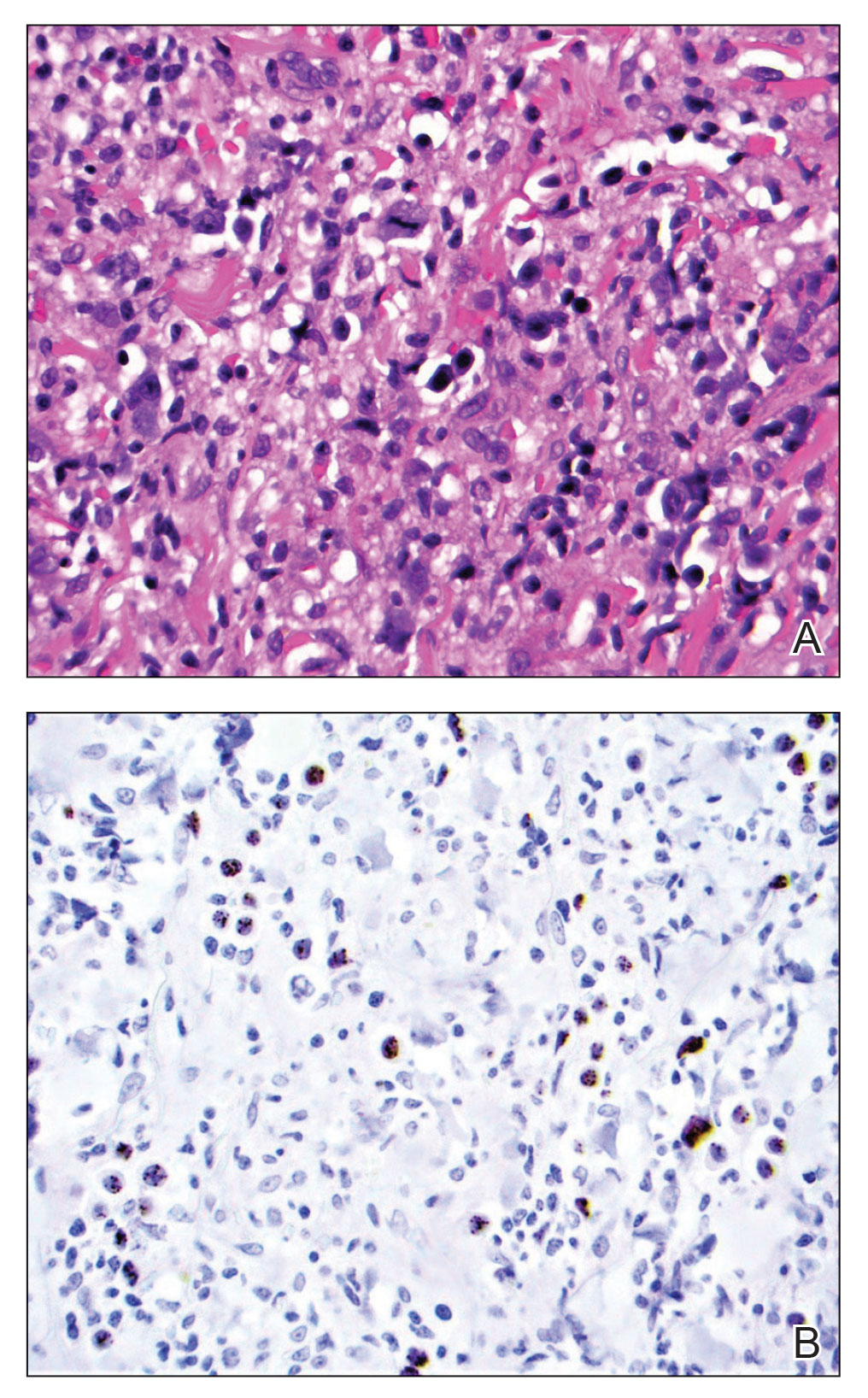

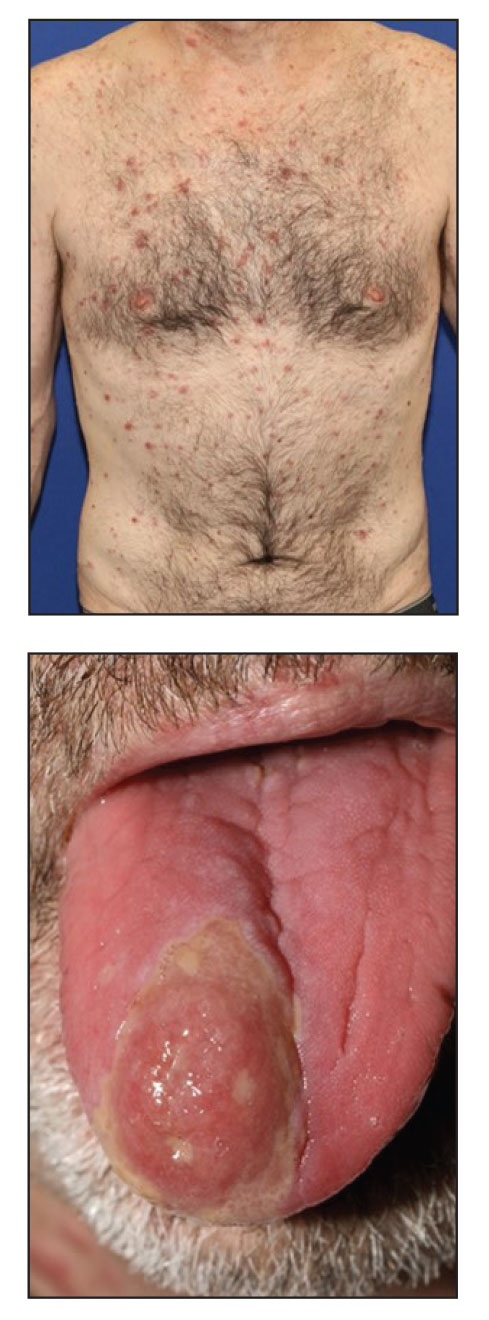

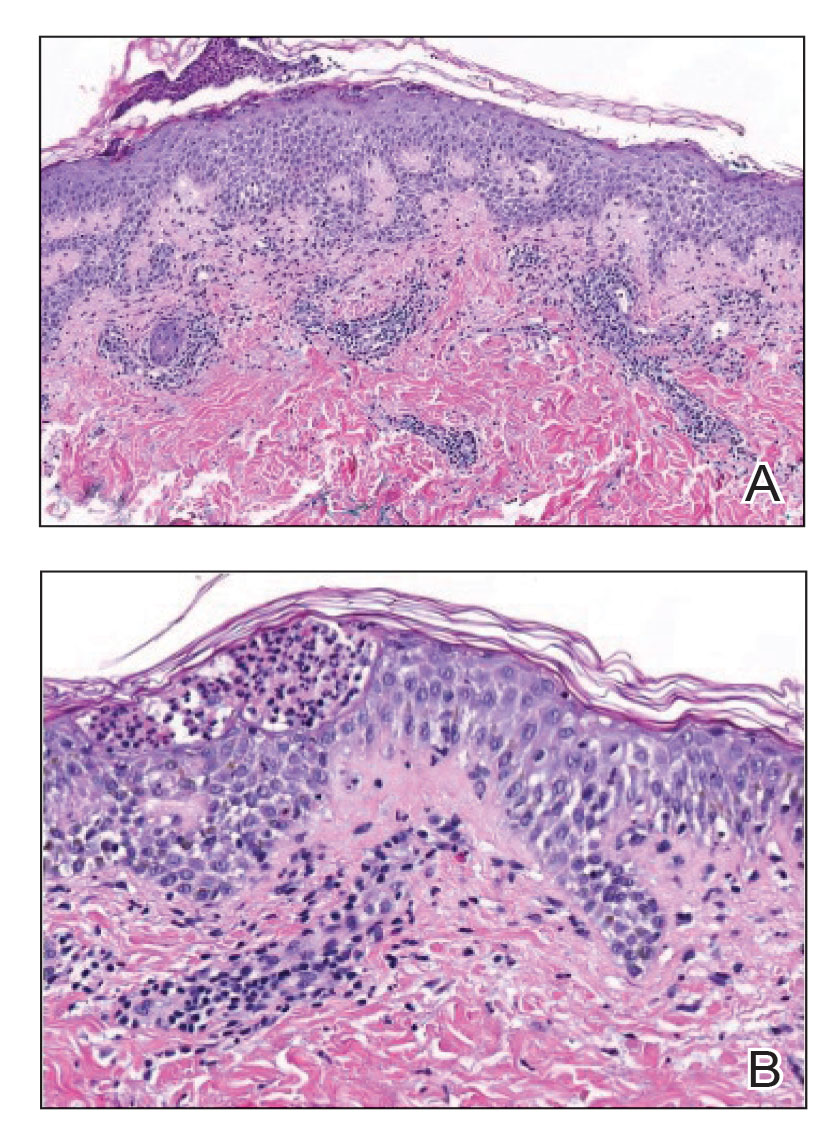

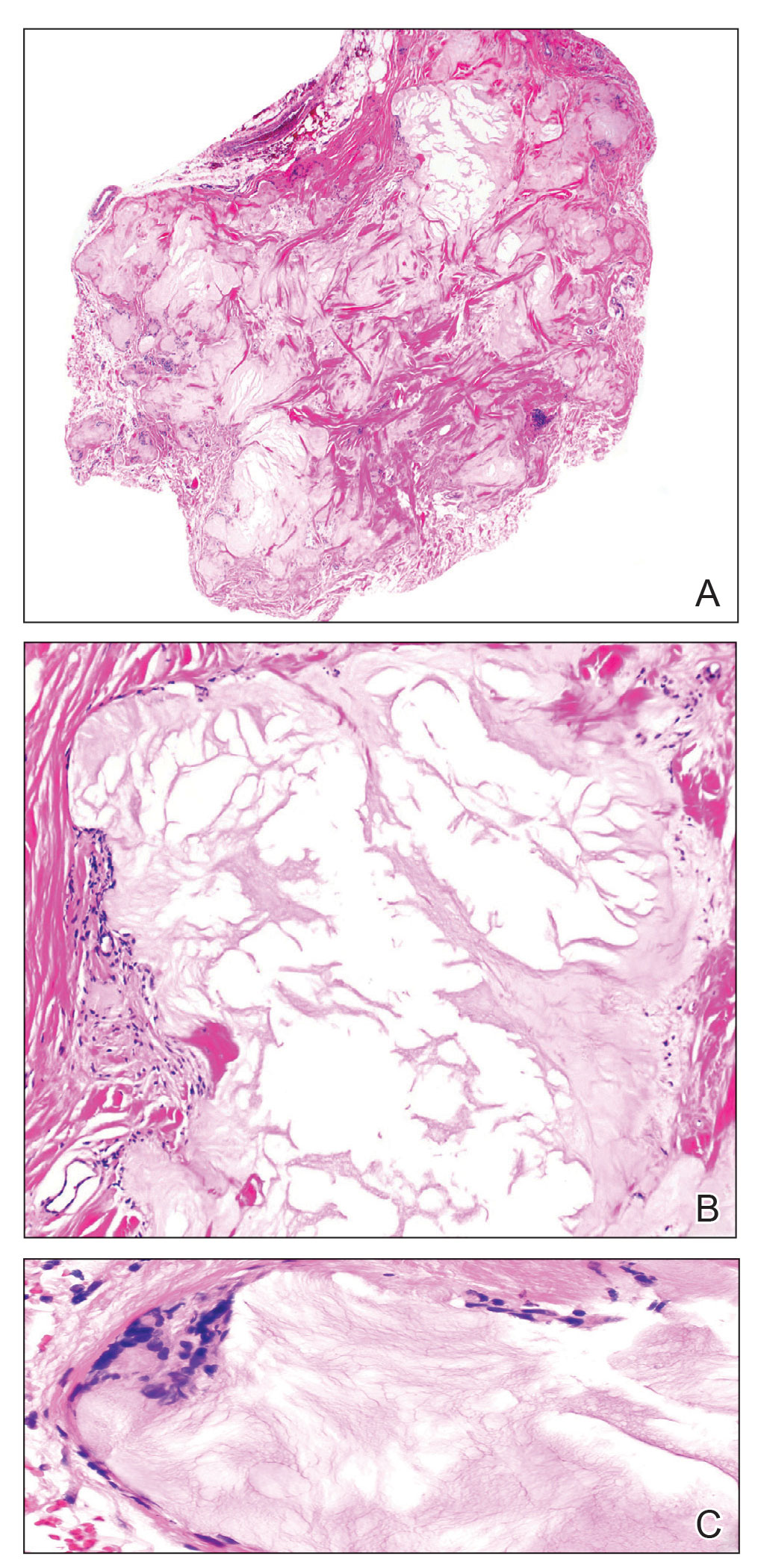

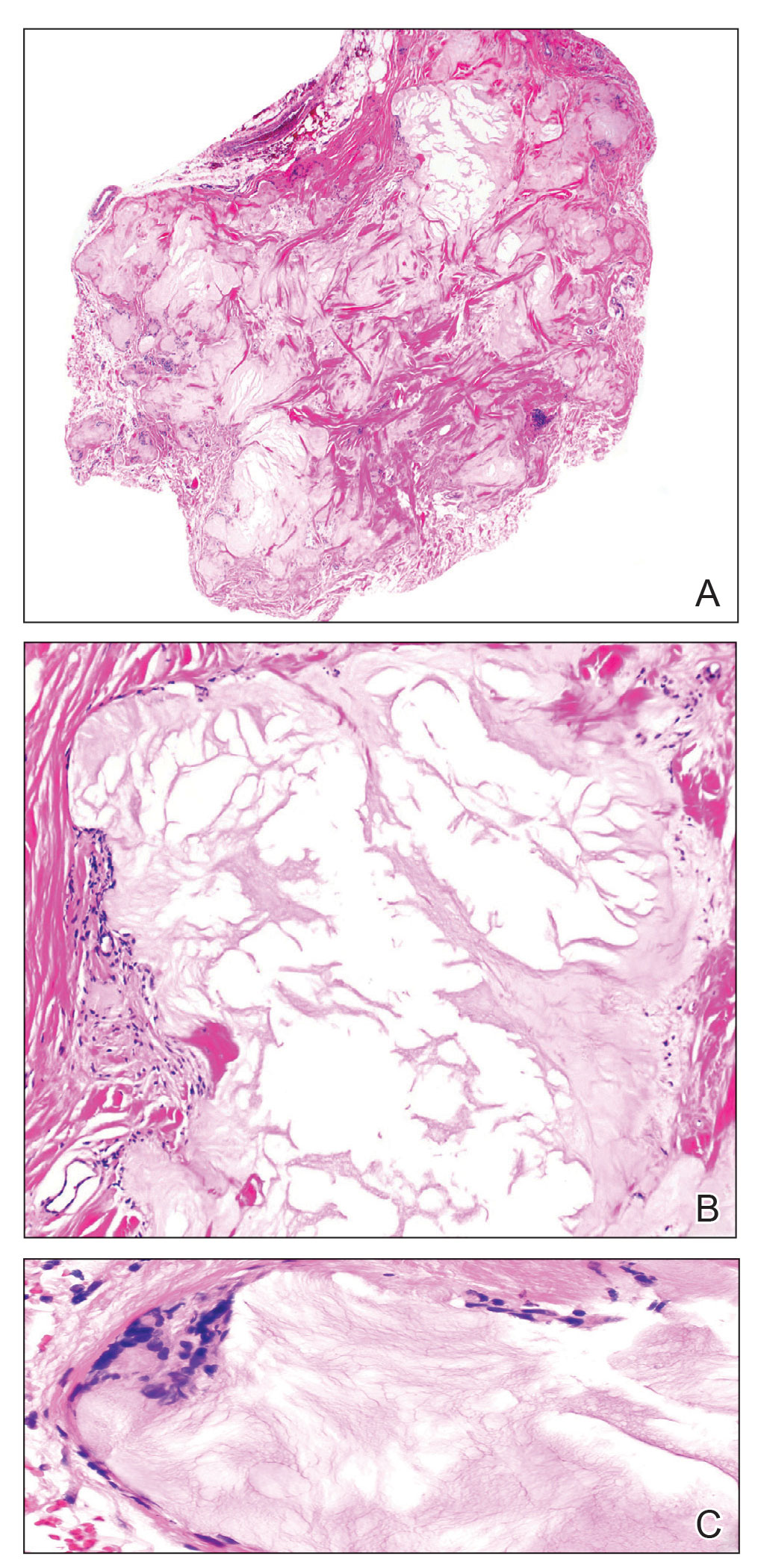

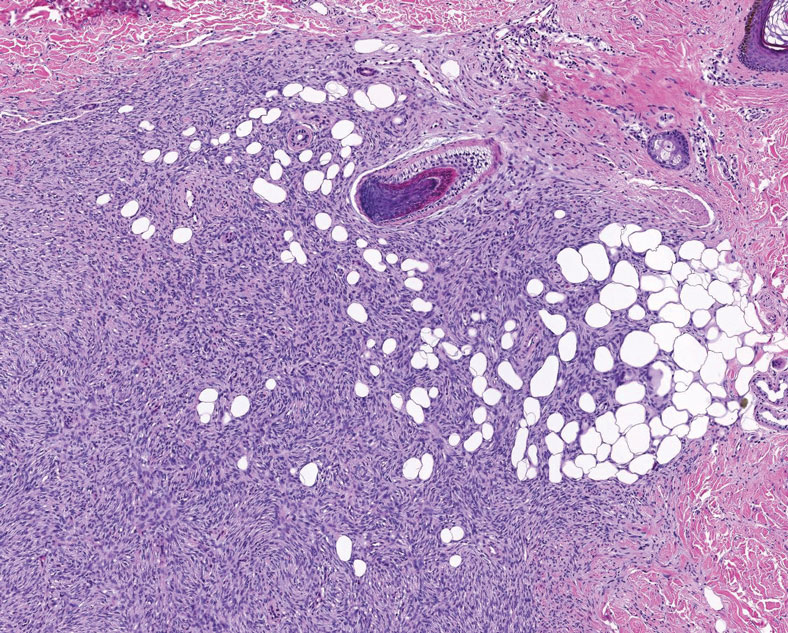

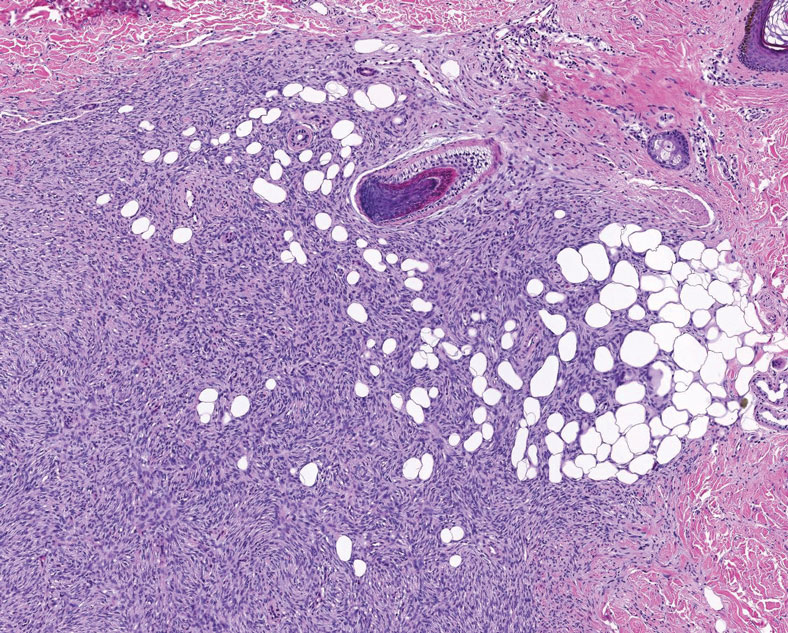

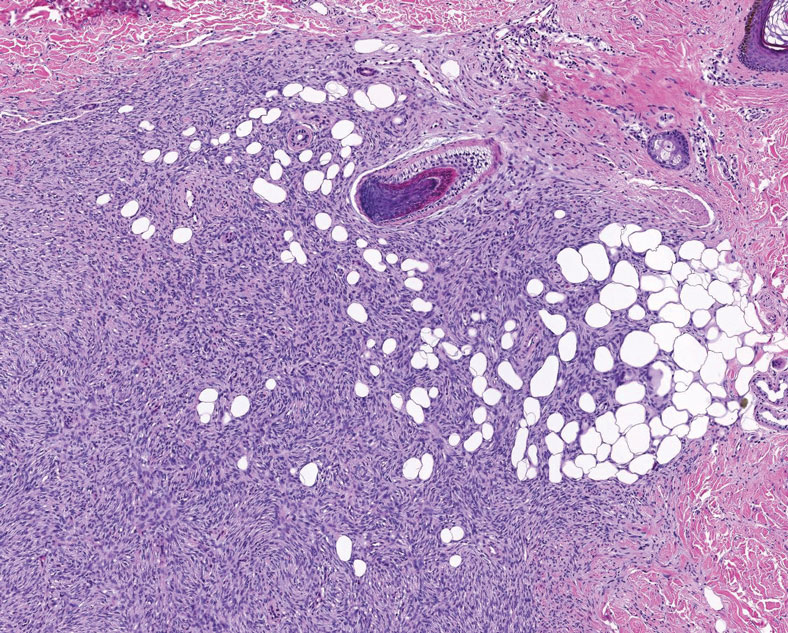

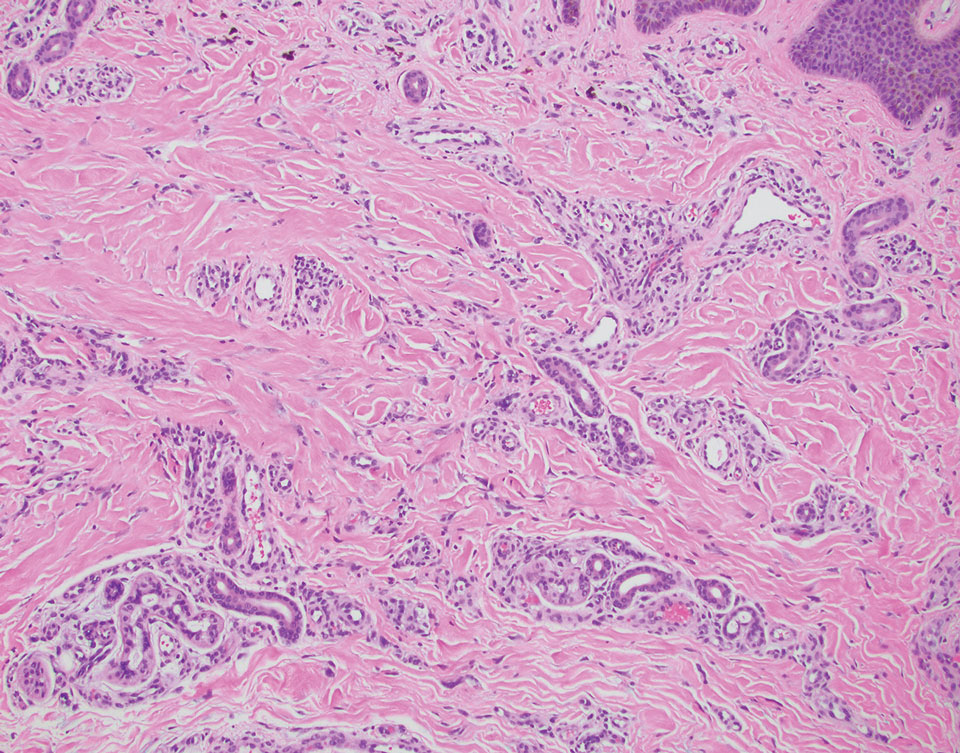

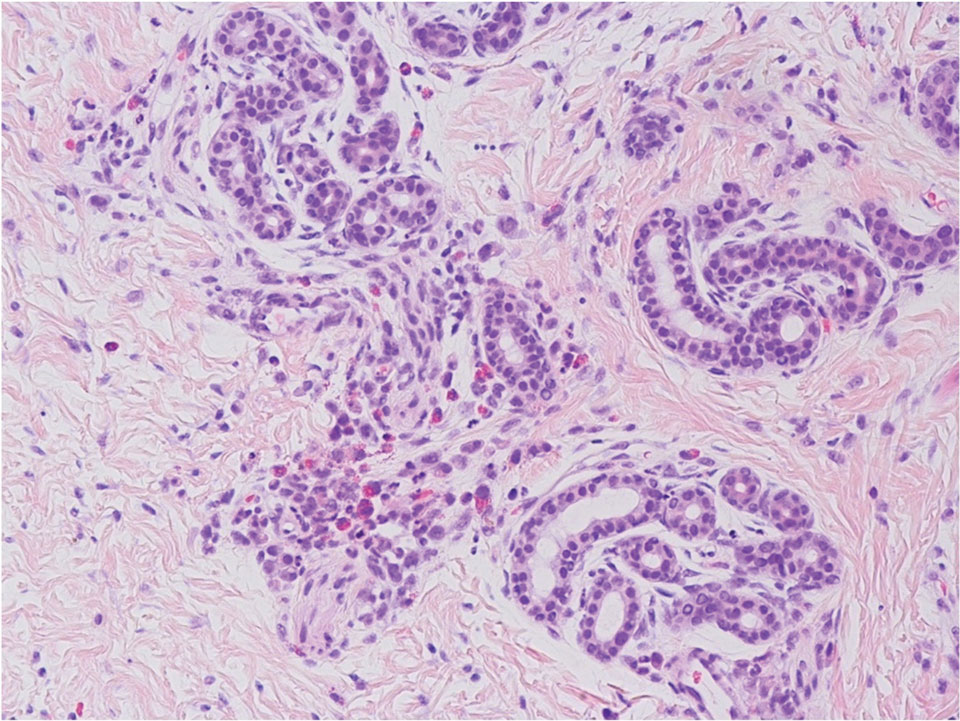

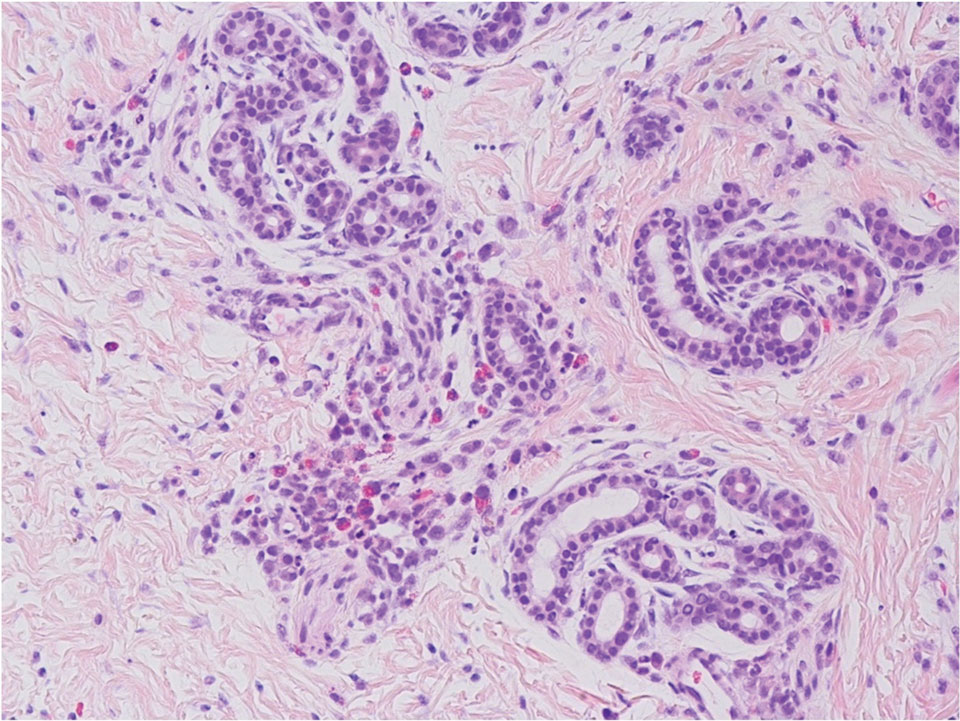

At the time of dermatology consultation, the patient was being managed on daratumumab and bortezomib. Physical examination revealed an infiltrative plaque on the right inferomedial thigh measuring approximately 6.0 cm (largest dimension) with a small amount of peripheral scale (Figure 1). An ultrasound revealed notable subcutaneous tissue edema and increased vascularity without a discrete mass or fluid collection. A 4-mm punch biopsy demonstrated a dense infiltrate comprised of collections of histiocytes admixed with scattered plasma cells and mature lymphoid aggregates. Additionally, rare enlarged plasmablastic cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm and slightly irregular nuclear contours were visualized (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD3 with a normal CD4:CD8 ratio, CD68-highlighted histiocytes within the lymphoid aggregates, and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(or Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus) demonstrated stippled nuclear staining within the scattered large cells (Figure 2B). Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA staining was negative, though the area of interest was lost on deeper sectioning of the tissue block. The histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous extracavitary PEL. Shortly after this diagnosis, he died from disease complications.

Primary effusion lymphoma is an aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that was first described by Knowles et al1 in 1989. Primary effusion lymphoma occurs exclusively in the setting of HHV-8 infection and typically is associated with chronic immunosuppression related to HIV/AIDS. Cases that are negative for HIV-1 are rare but have been reported in organ transplant recipients and elderly men from areas with a high prevalence of HHV-8 infections. Most HIV-associated cases show concurrent Epstein-Barr virus infection, though the pathogenic meaning of this co-infection remains unclear.2,3

Primary effusion lymphoma classically presents as an isolated effusion of malignant lymphoid cells within body cavities in the absence of solid tumor masses. The pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial spaces most commonly are involved. Extracavitary PEL, a rare variant, may present as a solid mass without effusion. In general, extracavitary tumors may occur in the setting of de novo malignancy or recurrent PEL.4 Cutaneous manifestations associated with extracavitary PEL are rare; 4 cases have been described in which skin lesions were the heralding sign of the disease.3 Interestingly, despite obligatory underlying HHV-8 infection, a review by Pielasinski et al3 noted only 2 patients with cutaneous PEL who had prior or concurrent Kaposi sarcoma. This heterogeneity in HHV-8–related phenotypes may be related to differences in microRNA expression, but further study is needed.5

The diagnosis of PEL relies on histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular analysis of the affected tissue. The malignant cells typically are large with round to irregular nuclei. These cells may demonstrate a variety of appearances, including anaplastic, plasmablastic, and immunoblastic morphologies.6,7 The immunophenotype displays CD45 positivity and markers of lymphocyte activation (CD30, CD38, CD71), while typical B-cell (CD19, CD20, CD79a) and T-cell (CD3, CD4, CD8) markers often are absent.6-8 Human herpesvirus 8 detection by polymerase chain reaction testing of the peripheral blood or by immunohistochemistry staining of the affected tissue is required for diagnosis.6,7 Epstein-Barr virus infection may be detected via in situ hybridization, though it is not required for diagnosis.

The overall prognosis for PEL is poor; Brimo et al6 reported a median survival of less than 6 months, and Guillet et al9 reported 5-year overall survival (OS) for PEL vs extracavitary PEL to be 43% vs 39%. Another review noted variation in survival contingent on the number of body cavities involved; patients with a single body cavity involved experienced a median OS of 18 months, whereas patients with multiple involved cavities experienced a median OS of 4 months,7 possibly due to the limited study of treatment regimens or disease aggressiveness. Even in cases of successful initial treatment, relapse within 6 to 8 months is common. Extracavitary PEL may have improved disease-free survival relative to classic PEL, though the data were less clear for OS.9 Limitations of the Guillet et al9 study included a small sample size, the impossibility to randomize to disease type, and loss of power on the log-rank test for OS in the setting of possible nonproportional hazards (crossing survival curves). Overall, prognostic differences between the groups may be challenging to ascertain until further data are obtained.

As with many HIV-associated neoplasms, antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV-positive patients affords a better prognosis when used in addition to therapy directed at malignancy.7 The general approach is for concurrent ART with systemic therapies such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone for the rare CD20+ cases, and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or dose-adjusted EPOCH therapy in the more common CD20− PEL cases. Narkhede et al7 suggested avoidance of methotrexate in patients with effusions because of increased toxicity, but it is unclear if this recommendation is applicable in extracavitary PEL patients without an effusion. Additionally, second-line treatment modalities include radiation for solid PEL masses, HHV-8–targeted antivirals, and stem cell transplantation, though evidence is limited. Of note, there is a phase I-II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02911142) ongoing for treatment-naïve PEL patients involving the experimental treatment DA-EPOCH-R plus lenalidomide, but the trial is ongoing.10

We report a case of cutaneous PEL in a patient with a history of Kaposi sarcoma. The patient’s deterioration and ultimate death despite initial treatment with EPOCH and bone marrow transplantation followed by final management with daratumumab and bortezomib confirm other reports that PEL has a poor prognosis and that optimal treatments are not well delineated for these patients. In general, the current approach is to utilize ART for HIV-positive patients and to then implement chemotherapy such as CHOP. Without continued research and careful planning of treatments, data will remain limited on how best to serve patients with PEL.

- Knowles DM, Inghirami G, Ubriaco A, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of three AIDS-associated neoplasms of uncertain lineage demonstrates their B-cell derivation and the possible pathogenetic role of the Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 1989;73:792-799.

- Kugasia IAR, Kumar A, Khatri A, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma of the pleural space: report of a rare complication of cardiac transplant with review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13005.

- Pielasinski U, Santonja C, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, et al. Extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma presenting as a cutaneous tumor: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:745-753.

- Boulanger E, Meignin V, Afonso PV, et al. Extracavitary tumor after primary effusion lymphoma: relapse or second distinct lymphoma? Haematologica. 2007;92:1275-1276.

- Goncalves PH, Uldrick TS, Yarchoan R. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma and related diseases. AIDS. 2017;31:1903-1916.

- Brimo F, Michel RP, Khetani K, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature with emphasis on cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical differential diagnosis. Cancer. 2007;111:224-233.

- Narkhede M, Arora S, Ujjani C. Primary effusion lymphoma: current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3747-3754.

- Chen YB, Rahemtullah A, Hochberg E. Primary effusion lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:569-576.

- Guillet S, Gerard L, Meignin V, et al. Classic and extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma in 51 HIV-infected patients from a single institution. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:233-237.

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented to the dermatology service with an asymptomatic plaque on the right thigh of 2 months’ duration. He had a medical history of HIV and Kaposi sarcoma as well as a recently relapsed primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) subsequent to an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. He initially was diagnosed with PEL 3 years prior to the current presentation during a workup for fever and weight loss. Imaging at the time demonstrated a bladder mass, which was biopsied and demonstrated PEL. Further imaging demonstrated both sinus and bone marrow involvement. Prior to dermatologic consultation, he had been treated with 6 cycles of etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH); 6 cycles of brentuximab; 4 cycles of rituximab with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin; and 2 cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide. Despite these therapies, he had 3 relapses, and oncology determined the need for a matched unrelated donor allogeneic stem cell transplant for his PEL.

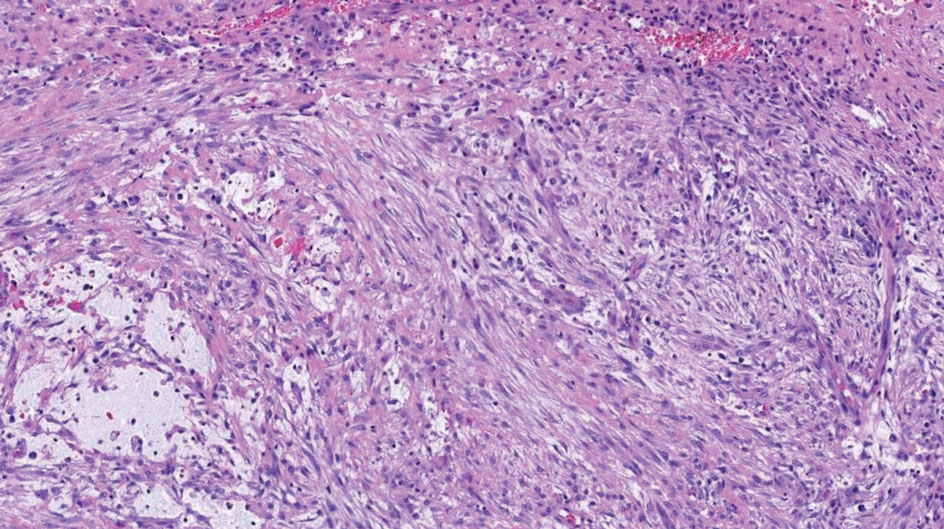

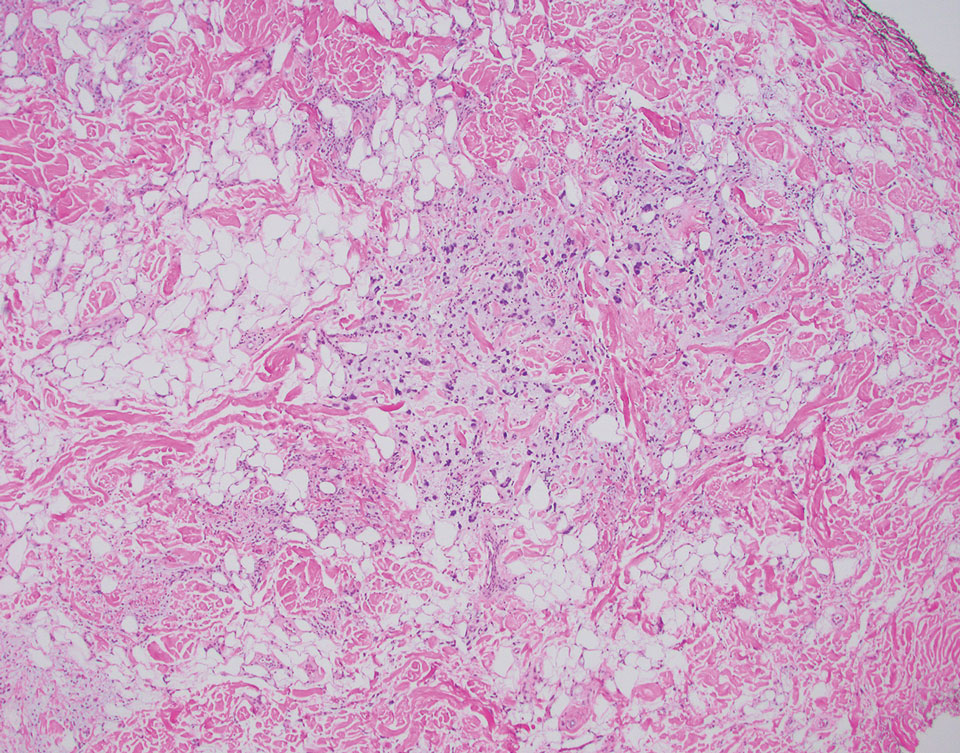

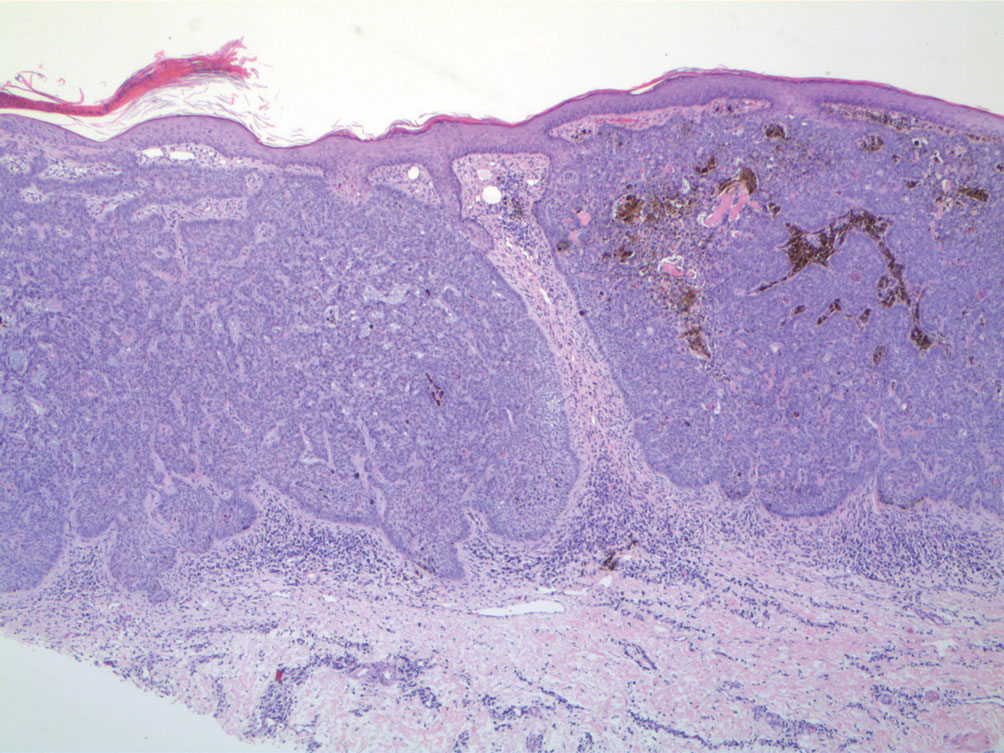

At the time of dermatology consultation, the patient was being managed on daratumumab and bortezomib. Physical examination revealed an infiltrative plaque on the right inferomedial thigh measuring approximately 6.0 cm (largest dimension) with a small amount of peripheral scale (Figure 1). An ultrasound revealed notable subcutaneous tissue edema and increased vascularity without a discrete mass or fluid collection. A 4-mm punch biopsy demonstrated a dense infiltrate comprised of collections of histiocytes admixed with scattered plasma cells and mature lymphoid aggregates. Additionally, rare enlarged plasmablastic cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm and slightly irregular nuclear contours were visualized (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD3 with a normal CD4:CD8 ratio, CD68-highlighted histiocytes within the lymphoid aggregates, and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(or Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus) demonstrated stippled nuclear staining within the scattered large cells (Figure 2B). Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA staining was negative, though the area of interest was lost on deeper sectioning of the tissue block. The histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous extracavitary PEL. Shortly after this diagnosis, he died from disease complications.

Primary effusion lymphoma is an aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that was first described by Knowles et al1 in 1989. Primary effusion lymphoma occurs exclusively in the setting of HHV-8 infection and typically is associated with chronic immunosuppression related to HIV/AIDS. Cases that are negative for HIV-1 are rare but have been reported in organ transplant recipients and elderly men from areas with a high prevalence of HHV-8 infections. Most HIV-associated cases show concurrent Epstein-Barr virus infection, though the pathogenic meaning of this co-infection remains unclear.2,3

Primary effusion lymphoma classically presents as an isolated effusion of malignant lymphoid cells within body cavities in the absence of solid tumor masses. The pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial spaces most commonly are involved. Extracavitary PEL, a rare variant, may present as a solid mass without effusion. In general, extracavitary tumors may occur in the setting of de novo malignancy or recurrent PEL.4 Cutaneous manifestations associated with extracavitary PEL are rare; 4 cases have been described in which skin lesions were the heralding sign of the disease.3 Interestingly, despite obligatory underlying HHV-8 infection, a review by Pielasinski et al3 noted only 2 patients with cutaneous PEL who had prior or concurrent Kaposi sarcoma. This heterogeneity in HHV-8–related phenotypes may be related to differences in microRNA expression, but further study is needed.5

The diagnosis of PEL relies on histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular analysis of the affected tissue. The malignant cells typically are large with round to irregular nuclei. These cells may demonstrate a variety of appearances, including anaplastic, plasmablastic, and immunoblastic morphologies.6,7 The immunophenotype displays CD45 positivity and markers of lymphocyte activation (CD30, CD38, CD71), while typical B-cell (CD19, CD20, CD79a) and T-cell (CD3, CD4, CD8) markers often are absent.6-8 Human herpesvirus 8 detection by polymerase chain reaction testing of the peripheral blood or by immunohistochemistry staining of the affected tissue is required for diagnosis.6,7 Epstein-Barr virus infection may be detected via in situ hybridization, though it is not required for diagnosis.

The overall prognosis for PEL is poor; Brimo et al6 reported a median survival of less than 6 months, and Guillet et al9 reported 5-year overall survival (OS) for PEL vs extracavitary PEL to be 43% vs 39%. Another review noted variation in survival contingent on the number of body cavities involved; patients with a single body cavity involved experienced a median OS of 18 months, whereas patients with multiple involved cavities experienced a median OS of 4 months,7 possibly due to the limited study of treatment regimens or disease aggressiveness. Even in cases of successful initial treatment, relapse within 6 to 8 months is common. Extracavitary PEL may have improved disease-free survival relative to classic PEL, though the data were less clear for OS.9 Limitations of the Guillet et al9 study included a small sample size, the impossibility to randomize to disease type, and loss of power on the log-rank test for OS in the setting of possible nonproportional hazards (crossing survival curves). Overall, prognostic differences between the groups may be challenging to ascertain until further data are obtained.

As with many HIV-associated neoplasms, antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV-positive patients affords a better prognosis when used in addition to therapy directed at malignancy.7 The general approach is for concurrent ART with systemic therapies such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone for the rare CD20+ cases, and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or dose-adjusted EPOCH therapy in the more common CD20− PEL cases. Narkhede et al7 suggested avoidance of methotrexate in patients with effusions because of increased toxicity, but it is unclear if this recommendation is applicable in extracavitary PEL patients without an effusion. Additionally, second-line treatment modalities include radiation for solid PEL masses, HHV-8–targeted antivirals, and stem cell transplantation, though evidence is limited. Of note, there is a phase I-II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02911142) ongoing for treatment-naïve PEL patients involving the experimental treatment DA-EPOCH-R plus lenalidomide, but the trial is ongoing.10

We report a case of cutaneous PEL in a patient with a history of Kaposi sarcoma. The patient’s deterioration and ultimate death despite initial treatment with EPOCH and bone marrow transplantation followed by final management with daratumumab and bortezomib confirm other reports that PEL has a poor prognosis and that optimal treatments are not well delineated for these patients. In general, the current approach is to utilize ART for HIV-positive patients and to then implement chemotherapy such as CHOP. Without continued research and careful planning of treatments, data will remain limited on how best to serve patients with PEL.

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented to the dermatology service with an asymptomatic plaque on the right thigh of 2 months’ duration. He had a medical history of HIV and Kaposi sarcoma as well as a recently relapsed primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) subsequent to an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. He initially was diagnosed with PEL 3 years prior to the current presentation during a workup for fever and weight loss. Imaging at the time demonstrated a bladder mass, which was biopsied and demonstrated PEL. Further imaging demonstrated both sinus and bone marrow involvement. Prior to dermatologic consultation, he had been treated with 6 cycles of etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (EPOCH); 6 cycles of brentuximab; 4 cycles of rituximab with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin; and 2 cycles of ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide. Despite these therapies, he had 3 relapses, and oncology determined the need for a matched unrelated donor allogeneic stem cell transplant for his PEL.

At the time of dermatology consultation, the patient was being managed on daratumumab and bortezomib. Physical examination revealed an infiltrative plaque on the right inferomedial thigh measuring approximately 6.0 cm (largest dimension) with a small amount of peripheral scale (Figure 1). An ultrasound revealed notable subcutaneous tissue edema and increased vascularity without a discrete mass or fluid collection. A 4-mm punch biopsy demonstrated a dense infiltrate comprised of collections of histiocytes admixed with scattered plasma cells and mature lymphoid aggregates. Additionally, rare enlarged plasmablastic cells with scant basophilic cytoplasm and slightly irregular nuclear contours were visualized (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD3 with a normal CD4:CD8 ratio, CD68-highlighted histiocytes within the lymphoid aggregates, and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(or Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus) demonstrated stippled nuclear staining within the scattered large cells (Figure 2B). Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA staining was negative, though the area of interest was lost on deeper sectioning of the tissue block. The histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous extracavitary PEL. Shortly after this diagnosis, he died from disease complications.

Primary effusion lymphoma is an aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that was first described by Knowles et al1 in 1989. Primary effusion lymphoma occurs exclusively in the setting of HHV-8 infection and typically is associated with chronic immunosuppression related to HIV/AIDS. Cases that are negative for HIV-1 are rare but have been reported in organ transplant recipients and elderly men from areas with a high prevalence of HHV-8 infections. Most HIV-associated cases show concurrent Epstein-Barr virus infection, though the pathogenic meaning of this co-infection remains unclear.2,3

Primary effusion lymphoma classically presents as an isolated effusion of malignant lymphoid cells within body cavities in the absence of solid tumor masses. The pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial spaces most commonly are involved. Extracavitary PEL, a rare variant, may present as a solid mass without effusion. In general, extracavitary tumors may occur in the setting of de novo malignancy or recurrent PEL.4 Cutaneous manifestations associated with extracavitary PEL are rare; 4 cases have been described in which skin lesions were the heralding sign of the disease.3 Interestingly, despite obligatory underlying HHV-8 infection, a review by Pielasinski et al3 noted only 2 patients with cutaneous PEL who had prior or concurrent Kaposi sarcoma. This heterogeneity in HHV-8–related phenotypes may be related to differences in microRNA expression, but further study is needed.5

The diagnosis of PEL relies on histologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular analysis of the affected tissue. The malignant cells typically are large with round to irregular nuclei. These cells may demonstrate a variety of appearances, including anaplastic, plasmablastic, and immunoblastic morphologies.6,7 The immunophenotype displays CD45 positivity and markers of lymphocyte activation (CD30, CD38, CD71), while typical B-cell (CD19, CD20, CD79a) and T-cell (CD3, CD4, CD8) markers often are absent.6-8 Human herpesvirus 8 detection by polymerase chain reaction testing of the peripheral blood or by immunohistochemistry staining of the affected tissue is required for diagnosis.6,7 Epstein-Barr virus infection may be detected via in situ hybridization, though it is not required for diagnosis.

The overall prognosis for PEL is poor; Brimo et al6 reported a median survival of less than 6 months, and Guillet et al9 reported 5-year overall survival (OS) for PEL vs extracavitary PEL to be 43% vs 39%. Another review noted variation in survival contingent on the number of body cavities involved; patients with a single body cavity involved experienced a median OS of 18 months, whereas patients with multiple involved cavities experienced a median OS of 4 months,7 possibly due to the limited study of treatment regimens or disease aggressiveness. Even in cases of successful initial treatment, relapse within 6 to 8 months is common. Extracavitary PEL may have improved disease-free survival relative to classic PEL, though the data were less clear for OS.9 Limitations of the Guillet et al9 study included a small sample size, the impossibility to randomize to disease type, and loss of power on the log-rank test for OS in the setting of possible nonproportional hazards (crossing survival curves). Overall, prognostic differences between the groups may be challenging to ascertain until further data are obtained.

As with many HIV-associated neoplasms, antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV-positive patients affords a better prognosis when used in addition to therapy directed at malignancy.7 The general approach is for concurrent ART with systemic therapies such as rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone for the rare CD20+ cases, and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or dose-adjusted EPOCH therapy in the more common CD20− PEL cases. Narkhede et al7 suggested avoidance of methotrexate in patients with effusions because of increased toxicity, but it is unclear if this recommendation is applicable in extracavitary PEL patients without an effusion. Additionally, second-line treatment modalities include radiation for solid PEL masses, HHV-8–targeted antivirals, and stem cell transplantation, though evidence is limited. Of note, there is a phase I-II trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02911142) ongoing for treatment-naïve PEL patients involving the experimental treatment DA-EPOCH-R plus lenalidomide, but the trial is ongoing.10

We report a case of cutaneous PEL in a patient with a history of Kaposi sarcoma. The patient’s deterioration and ultimate death despite initial treatment with EPOCH and bone marrow transplantation followed by final management with daratumumab and bortezomib confirm other reports that PEL has a poor prognosis and that optimal treatments are not well delineated for these patients. In general, the current approach is to utilize ART for HIV-positive patients and to then implement chemotherapy such as CHOP. Without continued research and careful planning of treatments, data will remain limited on how best to serve patients with PEL.

- Knowles DM, Inghirami G, Ubriaco A, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of three AIDS-associated neoplasms of uncertain lineage demonstrates their B-cell derivation and the possible pathogenetic role of the Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 1989;73:792-799.

- Kugasia IAR, Kumar A, Khatri A, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma of the pleural space: report of a rare complication of cardiac transplant with review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13005.

- Pielasinski U, Santonja C, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, et al. Extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma presenting as a cutaneous tumor: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:745-753.

- Boulanger E, Meignin V, Afonso PV, et al. Extracavitary tumor after primary effusion lymphoma: relapse or second distinct lymphoma? Haematologica. 2007;92:1275-1276.

- Goncalves PH, Uldrick TS, Yarchoan R. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma and related diseases. AIDS. 2017;31:1903-1916.

- Brimo F, Michel RP, Khetani K, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature with emphasis on cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical differential diagnosis. Cancer. 2007;111:224-233.

- Narkhede M, Arora S, Ujjani C. Primary effusion lymphoma: current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3747-3754.

- Chen YB, Rahemtullah A, Hochberg E. Primary effusion lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:569-576.

- Guillet S, Gerard L, Meignin V, et al. Classic and extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma in 51 HIV-infected patients from a single institution. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:233-237.

- Knowles DM, Inghirami G, Ubriaco A, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of three AIDS-associated neoplasms of uncertain lineage demonstrates their B-cell derivation and the possible pathogenetic role of the Epstein-Barr virus. Blood. 1989;73:792-799.

- Kugasia IAR, Kumar A, Khatri A, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma of the pleural space: report of a rare complication of cardiac transplant with review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019;21:E13005.

- Pielasinski U, Santonja C, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, et al. Extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma presenting as a cutaneous tumor: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:745-753.

- Boulanger E, Meignin V, Afonso PV, et al. Extracavitary tumor after primary effusion lymphoma: relapse or second distinct lymphoma? Haematologica. 2007;92:1275-1276.

- Goncalves PH, Uldrick TS, Yarchoan R. HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma and related diseases. AIDS. 2017;31:1903-1916.

- Brimo F, Michel RP, Khetani K, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma: a series of 4 cases and review of the literature with emphasis on cytomorphologic and immunocytochemical differential diagnosis. Cancer. 2007;111:224-233.

- Narkhede M, Arora S, Ujjani C. Primary effusion lymphoma: current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:3747-3754.

- Chen YB, Rahemtullah A, Hochberg E. Primary effusion lymphoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:569-576.

- Guillet S, Gerard L, Meignin V, et al. Classic and extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma in 51 HIV-infected patients from a single institution. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:233-237.

Practice Points

- Extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma is an aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma that occurs solely in the presence of human herpesvirus 8 infection and typically is associated with HIV/AIDS.

- Diagnosis necessitates a thorough workup and correlation of histologic, molecular, and immunophenotypic analysis.

- Antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive patients and intensive chemotherapy regimens are the current recommended treatments. Despite newer targeted agents, the prognosis remains poor.

Papular Acneform Eruption With Mucositis

The Diagnosis: Syphilis

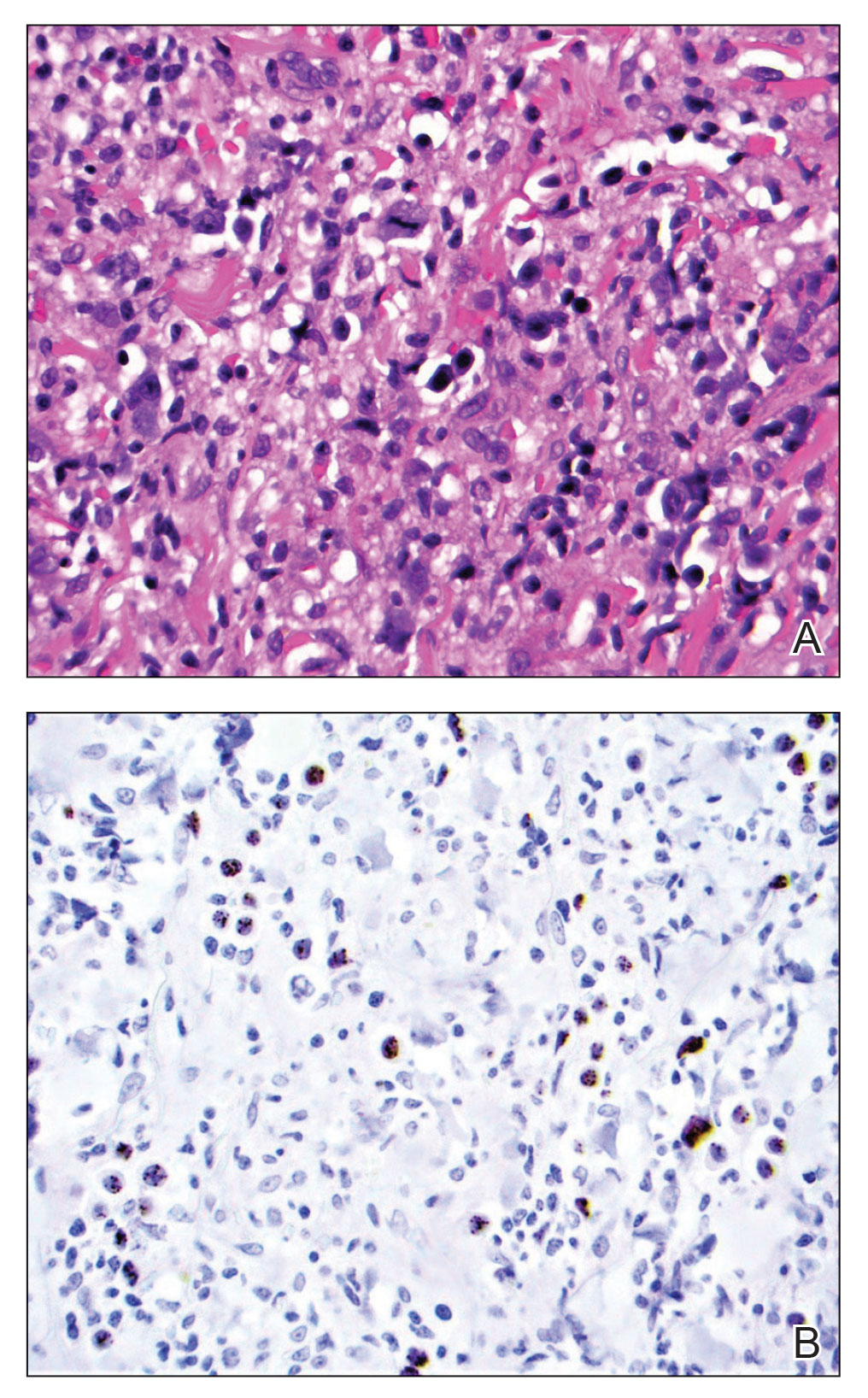

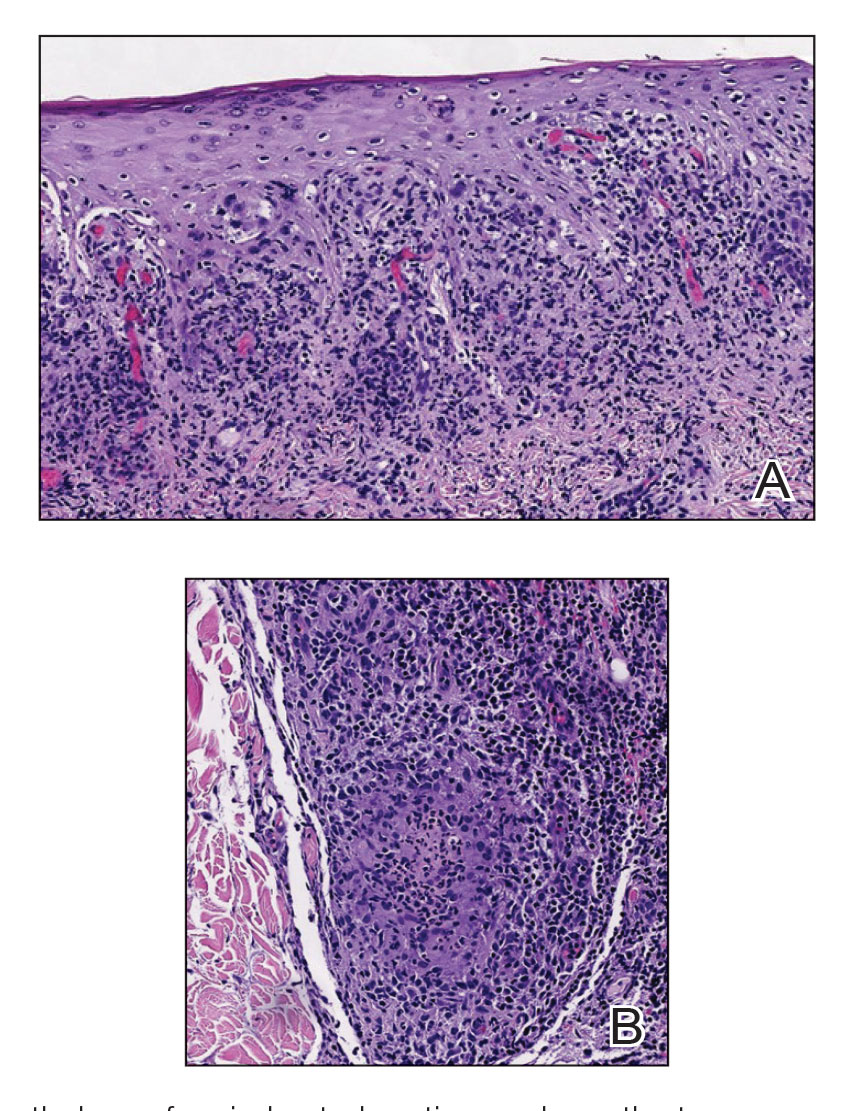

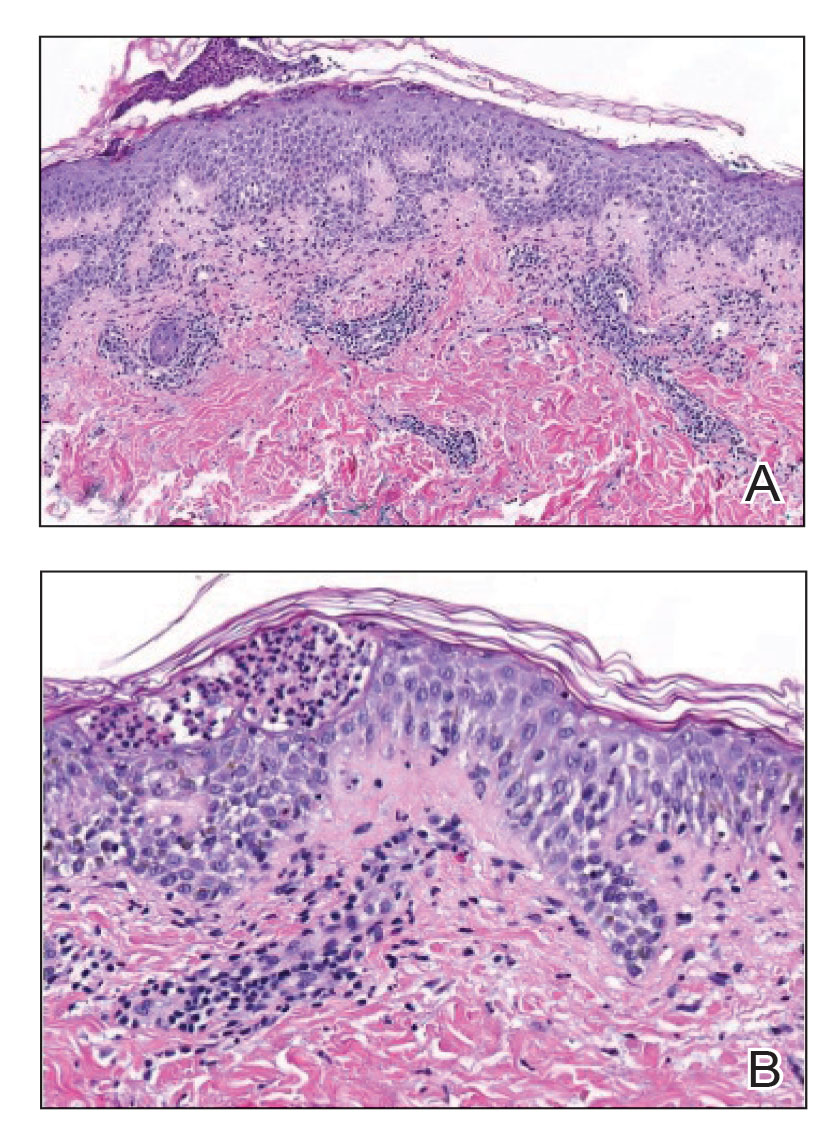

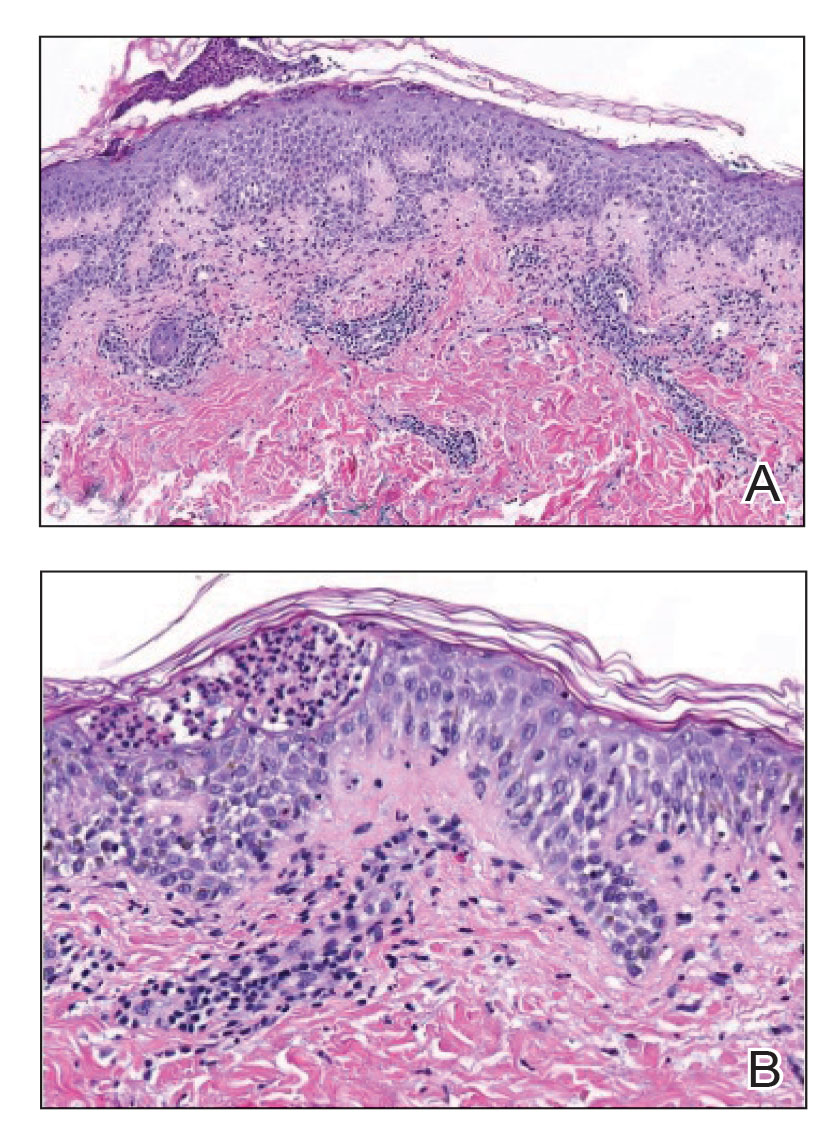

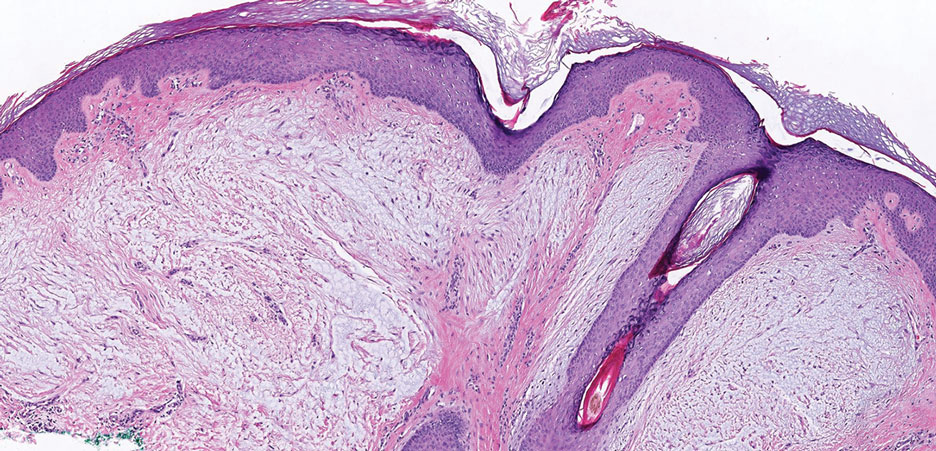

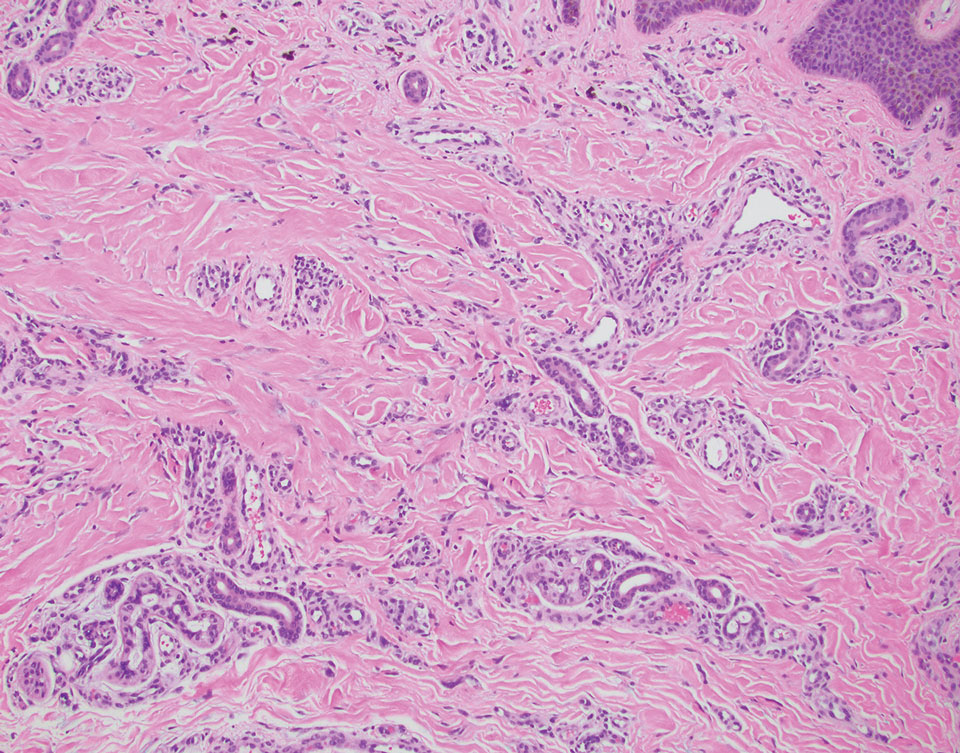

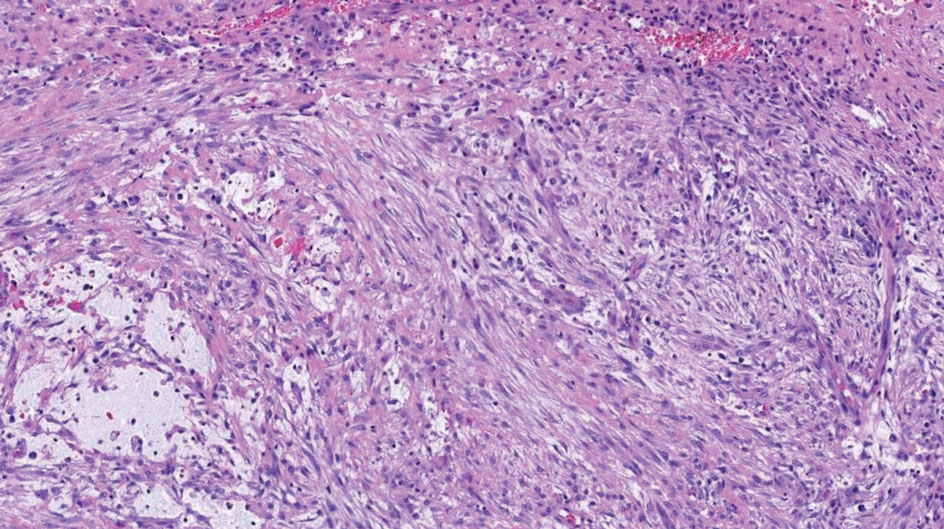

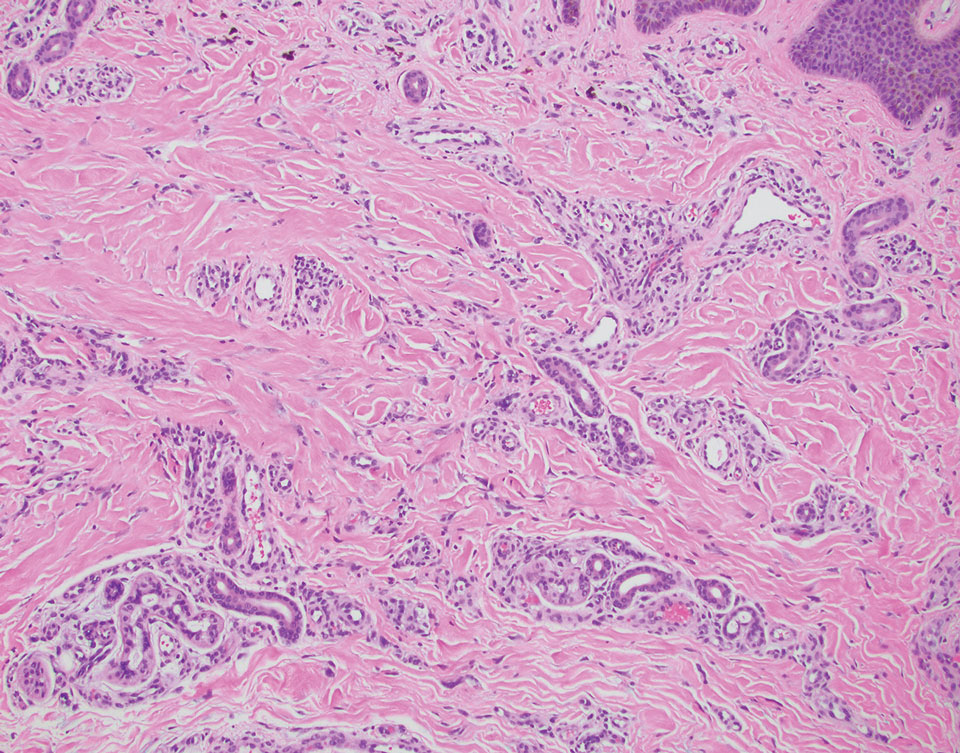

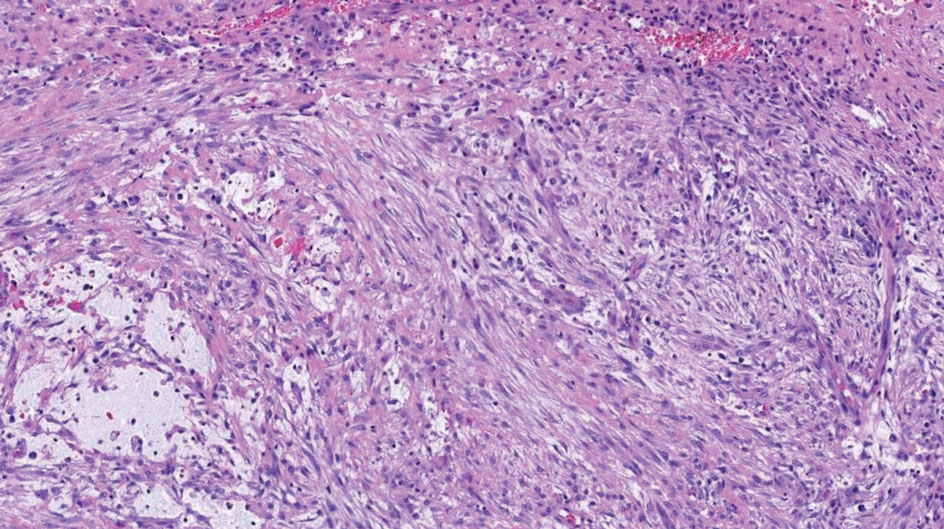

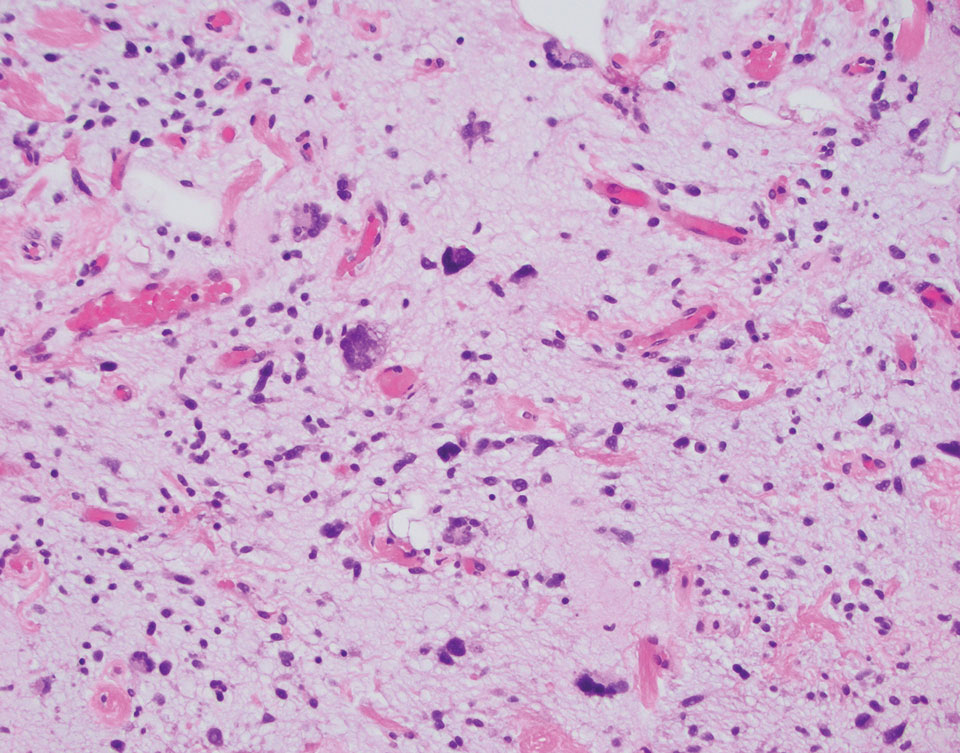

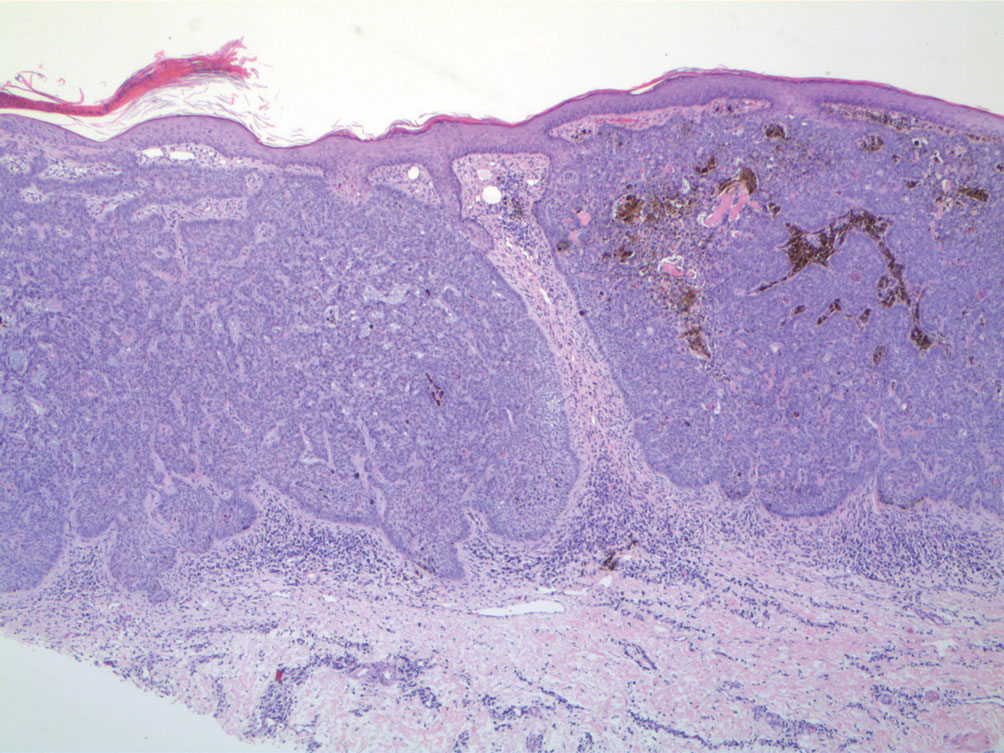

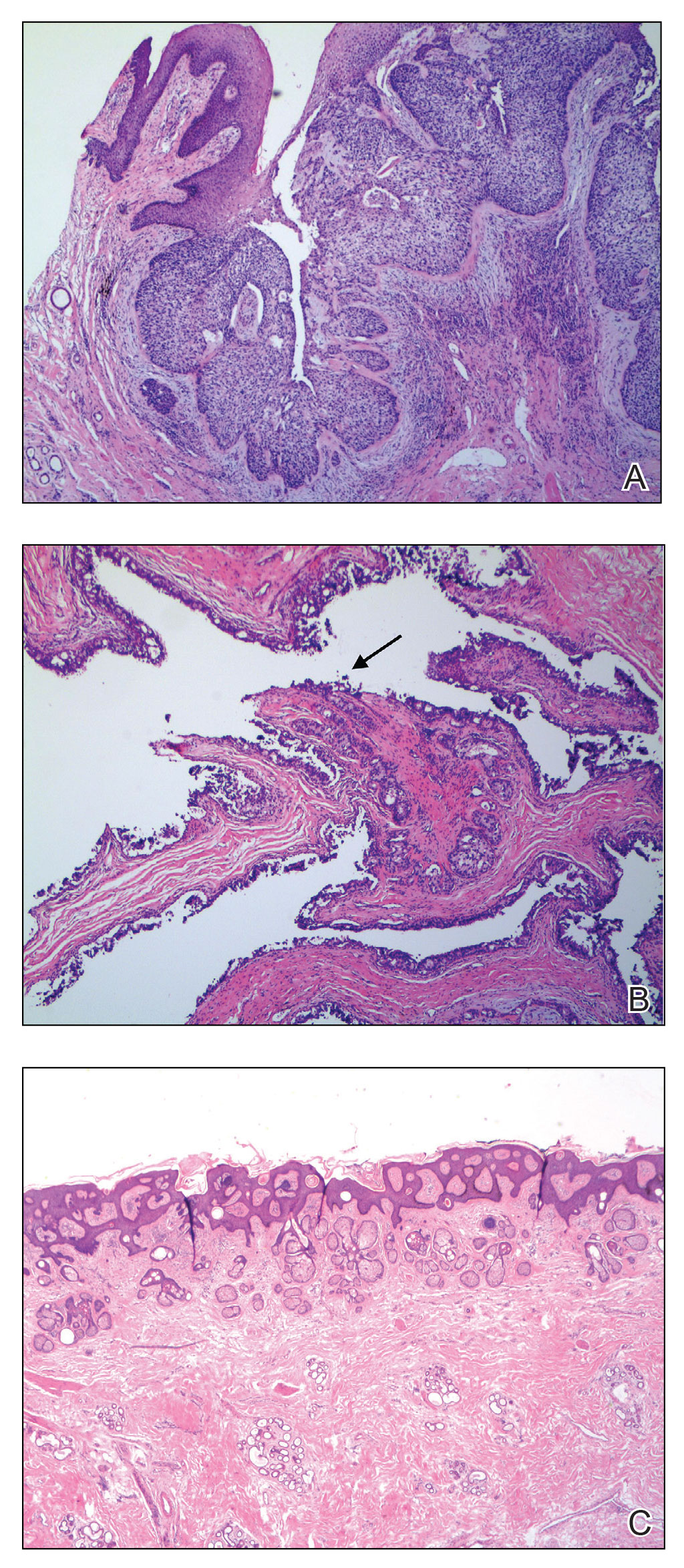

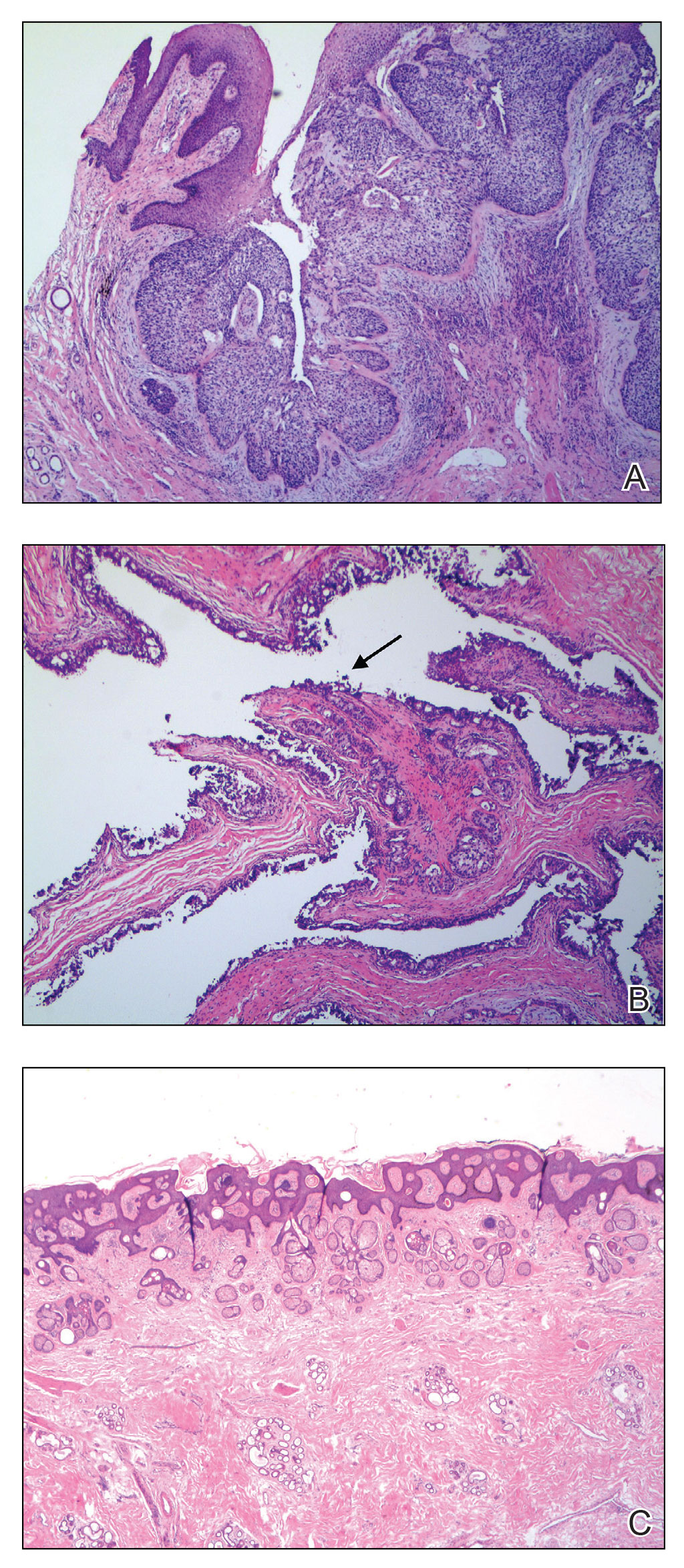

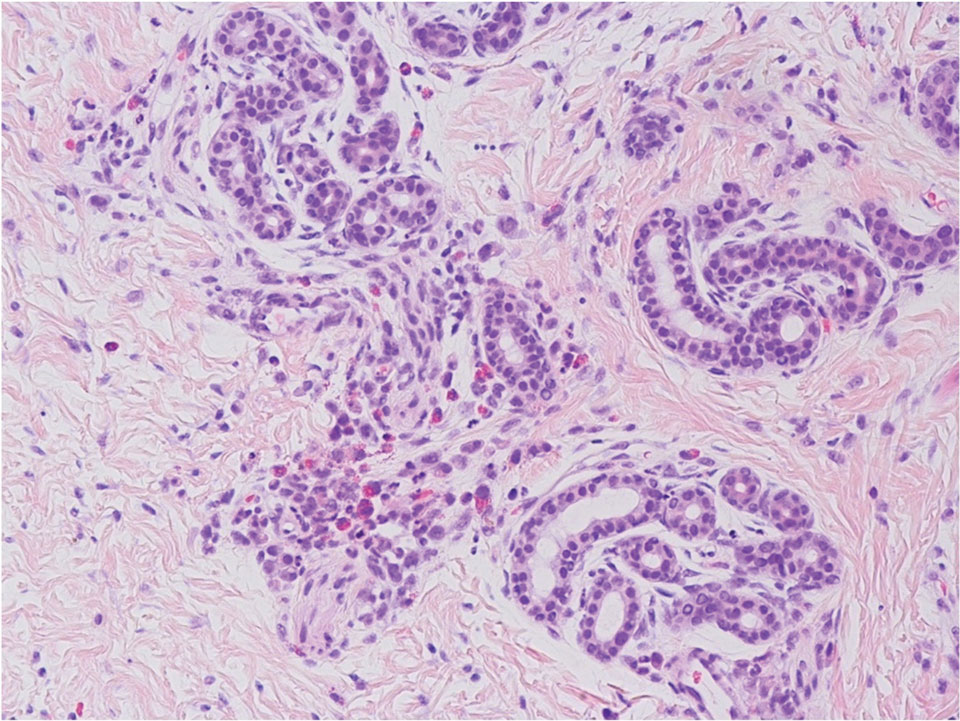

Histopathology revealed psoriasiform hyperplasia, endothelial cell swelling, and a brisk lichenoid inflammation with plasma cells (Figure, A). There also was pustular folliculitis in association with well-formed granulomatous inflammation and a prominent number of plasma cells (Figure, B). Treponema pallidum immunostaining showed numerous organisms in the epidermal and follicular epithelium. Rapid plasma reagin was found to be positive with a titer of 1:128. Evaluation for neurosyphilis through lumbar puncture was negative; the patient also was HIV negative. All of our patient’s skin lesions cleared after a 3-week course of weekly intramuscular benzathine G injections. Due to his substantial clinical improvement, the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.