User login

Self-fitted and audiologist-fitted hearing aids equal for mild to moderate hearing loss

Self-fitted over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids may be an effective option for individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss, a small randomized effectiveness trial reports. OTC devices yielded 6-week patient-perceived and clinical outcomes comparable to those with audiologist-fitted hearing aids, In fact, at week 2, the self-fitted group had a small but meaningful advantage on two of the four study outcome measures.

“After support and fine-tuning were provided to the self-fitting (remote support) and audiologist-fitted groups, no clinically meaningful differences were evident in any outcome measures at the end of the 6-week trial,” wrote researchers led by Karina C. De Sousa, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of speech-language pathology and audiology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Their findings appear in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Hearing aid uptake is low even in populations with adequate access to audiological resources, the authors noted, with hearing aid use in U.S. adults who could benefit estimated at about 20%. Currently, an estimated 22.9 million older Americans with audiometric hearing loss do not use hearing aids.

Major barriers have been access and affordability, Dr. De Sousa and associates wrote, and until recently, people with hearing loss could obtain hearing aids only after consultation with a credentialed dispenser. “The World Health Organization estimates that over 2.5 billion people will experience some degree of hearing loss by 2050,” Dr. De Sousa said in an interview. “This new category of self-fitting hearing aids opens up newer care pathways for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.”

The study

From April to August 2022 the trial recruited 68 participants (51.6% men) with mild-to-moderate self-reported hearing loss, a mean age of 63.6 years, and no ear disease within the past 90 days. They were randomized to a self-fitted commercially available device (Lexi Lumen), with instructional material on set-up and remote support, or to the same unit fitted by an audiologist. The majority in both arms were new users and were similar in age and baseline hearing scores.

The primary outcome measure was patient-reported hearing aid benefit, measured by the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. This scale evaluates auditory acuity before and after amplification by such criteria as ease of communication, background noise, reverberation, aversiveness, and global hearing status.

Secondary measures included the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) and speech recognition in noise measured using an abbreviated speech-in-noise test and a digits-in-noise test. Measures were taken at baseline, week 2, and week 6 after fitting. After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting arm had an initial advantage on the self-reported APHAB: difference, Cohen d = −.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 0). It also fared better on the IOI-HA: effect size, r = 0.3 (95% CI, .0 to –.5), but not on speech recognition in noise.

One member of the self-fitting arm withdrew owing to an unrelated middle-ear infection.

“While these results are promising, it is essential to note that OTC hearing aids are not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dr. De Sousa said. “If a person has ear disease symptoms or hearing loss that is too severe, they have to consult a trained hearing health care professional.” She added that proper use of a self-fitted OTC hearing aid requires a degree of digital proficiency, as many devices are set up using a smartphone.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and by the hearX Group, which provided the Lexie Lumen devices and software support for data collection. Dr. De Sousa reported nonfinancial support from hearX as well as consulting fees from hearX outside of the submitted work. A coauthor reported grant support from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and fees from hearX during and outside of the study. Another coauthor disclosed fees, equity, and grant support from hearX during the conduct of the study.

Self-fitted over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids may be an effective option for individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss, a small randomized effectiveness trial reports. OTC devices yielded 6-week patient-perceived and clinical outcomes comparable to those with audiologist-fitted hearing aids, In fact, at week 2, the self-fitted group had a small but meaningful advantage on two of the four study outcome measures.

“After support and fine-tuning were provided to the self-fitting (remote support) and audiologist-fitted groups, no clinically meaningful differences were evident in any outcome measures at the end of the 6-week trial,” wrote researchers led by Karina C. De Sousa, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of speech-language pathology and audiology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Their findings appear in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Hearing aid uptake is low even in populations with adequate access to audiological resources, the authors noted, with hearing aid use in U.S. adults who could benefit estimated at about 20%. Currently, an estimated 22.9 million older Americans with audiometric hearing loss do not use hearing aids.

Major barriers have been access and affordability, Dr. De Sousa and associates wrote, and until recently, people with hearing loss could obtain hearing aids only after consultation with a credentialed dispenser. “The World Health Organization estimates that over 2.5 billion people will experience some degree of hearing loss by 2050,” Dr. De Sousa said in an interview. “This new category of self-fitting hearing aids opens up newer care pathways for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.”

The study

From April to August 2022 the trial recruited 68 participants (51.6% men) with mild-to-moderate self-reported hearing loss, a mean age of 63.6 years, and no ear disease within the past 90 days. They were randomized to a self-fitted commercially available device (Lexi Lumen), with instructional material on set-up and remote support, or to the same unit fitted by an audiologist. The majority in both arms were new users and were similar in age and baseline hearing scores.

The primary outcome measure was patient-reported hearing aid benefit, measured by the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. This scale evaluates auditory acuity before and after amplification by such criteria as ease of communication, background noise, reverberation, aversiveness, and global hearing status.

Secondary measures included the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) and speech recognition in noise measured using an abbreviated speech-in-noise test and a digits-in-noise test. Measures were taken at baseline, week 2, and week 6 after fitting. After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting arm had an initial advantage on the self-reported APHAB: difference, Cohen d = −.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 0). It also fared better on the IOI-HA: effect size, r = 0.3 (95% CI, .0 to –.5), but not on speech recognition in noise.

One member of the self-fitting arm withdrew owing to an unrelated middle-ear infection.

“While these results are promising, it is essential to note that OTC hearing aids are not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dr. De Sousa said. “If a person has ear disease symptoms or hearing loss that is too severe, they have to consult a trained hearing health care professional.” She added that proper use of a self-fitted OTC hearing aid requires a degree of digital proficiency, as many devices are set up using a smartphone.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and by the hearX Group, which provided the Lexie Lumen devices and software support for data collection. Dr. De Sousa reported nonfinancial support from hearX as well as consulting fees from hearX outside of the submitted work. A coauthor reported grant support from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and fees from hearX during and outside of the study. Another coauthor disclosed fees, equity, and grant support from hearX during the conduct of the study.

Self-fitted over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids may be an effective option for individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss, a small randomized effectiveness trial reports. OTC devices yielded 6-week patient-perceived and clinical outcomes comparable to those with audiologist-fitted hearing aids, In fact, at week 2, the self-fitted group had a small but meaningful advantage on two of the four study outcome measures.

“After support and fine-tuning were provided to the self-fitting (remote support) and audiologist-fitted groups, no clinically meaningful differences were evident in any outcome measures at the end of the 6-week trial,” wrote researchers led by Karina C. De Sousa, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of speech-language pathology and audiology at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Their findings appear in JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

Hearing aid uptake is low even in populations with adequate access to audiological resources, the authors noted, with hearing aid use in U.S. adults who could benefit estimated at about 20%. Currently, an estimated 22.9 million older Americans with audiometric hearing loss do not use hearing aids.

Major barriers have been access and affordability, Dr. De Sousa and associates wrote, and until recently, people with hearing loss could obtain hearing aids only after consultation with a credentialed dispenser. “The World Health Organization estimates that over 2.5 billion people will experience some degree of hearing loss by 2050,” Dr. De Sousa said in an interview. “This new category of self-fitting hearing aids opens up newer care pathways for people with mild to moderate hearing loss.”

The study

From April to August 2022 the trial recruited 68 participants (51.6% men) with mild-to-moderate self-reported hearing loss, a mean age of 63.6 years, and no ear disease within the past 90 days. They were randomized to a self-fitted commercially available device (Lexi Lumen), with instructional material on set-up and remote support, or to the same unit fitted by an audiologist. The majority in both arms were new users and were similar in age and baseline hearing scores.

The primary outcome measure was patient-reported hearing aid benefit, measured by the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) questionnaire. This scale evaluates auditory acuity before and after amplification by such criteria as ease of communication, background noise, reverberation, aversiveness, and global hearing status.

Secondary measures included the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) and speech recognition in noise measured using an abbreviated speech-in-noise test and a digits-in-noise test. Measures were taken at baseline, week 2, and week 6 after fitting. After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting arm had an initial advantage on the self-reported APHAB: difference, Cohen d = −.5 (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.0 to 0). It also fared better on the IOI-HA: effect size, r = 0.3 (95% CI, .0 to –.5), but not on speech recognition in noise.

One member of the self-fitting arm withdrew owing to an unrelated middle-ear infection.

“While these results are promising, it is essential to note that OTC hearing aids are not a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dr. De Sousa said. “If a person has ear disease symptoms or hearing loss that is too severe, they have to consult a trained hearing health care professional.” She added that proper use of a self-fitted OTC hearing aid requires a degree of digital proficiency, as many devices are set up using a smartphone.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and by the hearX Group, which provided the Lexie Lumen devices and software support for data collection. Dr. De Sousa reported nonfinancial support from hearX as well as consulting fees from hearX outside of the submitted work. A coauthor reported grant support from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, and fees from hearX during and outside of the study. Another coauthor disclosed fees, equity, and grant support from hearX during the conduct of the study.

FROM JAMA OTOLARYNGOLOGY–HEAD & NECK SURGERY

Urban green and blue spaces linked to less psychological distress

The findings of the study, which was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, build on a growing understanding of the relationship between types and qualities of urban environments and dementia risk.

Adithya Vegaraju, a student at Washington State University, Spokane, led the study, which looked at data from the Washington State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess prevalence of serious psychological distress among 42,980 Washington state residents aged 65 and over.

The data, collected between 2011 and 2019, used a self-reported questionnaire to determine serious psychological distress, which is defined as a level of mental distress considered debilitating enough to warrant treatment.

Mr. Vegaraju and his coauthor Solmaz Amiri, DDes, also of Washington State University, used ZIP codes, along with U.S. census data, to approximate the urban adults’ proximity to green and blue spaces.

After controlling for potential confounders of age, sex, ethnicity, education, and marital status, the investigators found that people living within half a mile of green or blue spaces had a 17% lower risk of experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with people living farther from these spaces, the investigators said in a news release.

Implications for cognitive decline and dementia?

Psychological distress in adults has been linked in population-based longitudinal studies to later cognitive decline and dementia. One study in older adults found the risk of dementia to be more than 50% higher among adults aged 50-70 with persistent depression. Blue and green spaces have also been investigated in relation to neurodegenerative disease among older adults; a 2022 study looking at data from some 62 million Medicare beneficiaries found those living in areas with more vegetation saw lower risk of hospitalizations for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“Since we lack effective prevention methods or treatments for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, we need to get creative in how we look at these issues,” Dr. Amiri commented in a press statement about her and Mr. Vegaraju’s findings. “Our hope is that this study showing better mental health among people living close to parks and water will trigger other studies about how these benefits work and whether this proximity can help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

The investigators acknowledged that their findings were limited by reliance on a self-reported measure of psychological distress.

A bidirectional connection with depression and dementia

In a comment, Anjum Hajat, PhD, an epidemiologist at University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle who has also studied the relationship between green space and dementia risk in older adults, noted some further apparent limitations of the new study, for which only an abstract was available at publication.

“It has been shown that people with depression are at higher risk for dementia, but the opposite is also true,” Dr. Hajat commented. “Those with dementia are more likely to develop depression. This bidirectionality makes this study abstract difficult to interpret since the study is based on cross-sectional data: Individuals are not followed over time to see which develops first, dementia or depression.”

Additionally, Dr. Hajat noted, the data used to determine proximity to green and blue spaces did not allow for the calculation of precise distances between subjects’ homes and these spaces.

Mr. Vegaraju and Dr. Amiri’s study had no outside support, and the investigators declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hajat declared no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the study, which was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, build on a growing understanding of the relationship between types and qualities of urban environments and dementia risk.

Adithya Vegaraju, a student at Washington State University, Spokane, led the study, which looked at data from the Washington State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess prevalence of serious psychological distress among 42,980 Washington state residents aged 65 and over.

The data, collected between 2011 and 2019, used a self-reported questionnaire to determine serious psychological distress, which is defined as a level of mental distress considered debilitating enough to warrant treatment.

Mr. Vegaraju and his coauthor Solmaz Amiri, DDes, also of Washington State University, used ZIP codes, along with U.S. census data, to approximate the urban adults’ proximity to green and blue spaces.

After controlling for potential confounders of age, sex, ethnicity, education, and marital status, the investigators found that people living within half a mile of green or blue spaces had a 17% lower risk of experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with people living farther from these spaces, the investigators said in a news release.

Implications for cognitive decline and dementia?

Psychological distress in adults has been linked in population-based longitudinal studies to later cognitive decline and dementia. One study in older adults found the risk of dementia to be more than 50% higher among adults aged 50-70 with persistent depression. Blue and green spaces have also been investigated in relation to neurodegenerative disease among older adults; a 2022 study looking at data from some 62 million Medicare beneficiaries found those living in areas with more vegetation saw lower risk of hospitalizations for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“Since we lack effective prevention methods or treatments for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, we need to get creative in how we look at these issues,” Dr. Amiri commented in a press statement about her and Mr. Vegaraju’s findings. “Our hope is that this study showing better mental health among people living close to parks and water will trigger other studies about how these benefits work and whether this proximity can help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

The investigators acknowledged that their findings were limited by reliance on a self-reported measure of psychological distress.

A bidirectional connection with depression and dementia

In a comment, Anjum Hajat, PhD, an epidemiologist at University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle who has also studied the relationship between green space and dementia risk in older adults, noted some further apparent limitations of the new study, for which only an abstract was available at publication.

“It has been shown that people with depression are at higher risk for dementia, but the opposite is also true,” Dr. Hajat commented. “Those with dementia are more likely to develop depression. This bidirectionality makes this study abstract difficult to interpret since the study is based on cross-sectional data: Individuals are not followed over time to see which develops first, dementia or depression.”

Additionally, Dr. Hajat noted, the data used to determine proximity to green and blue spaces did not allow for the calculation of precise distances between subjects’ homes and these spaces.

Mr. Vegaraju and Dr. Amiri’s study had no outside support, and the investigators declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hajat declared no conflicts of interest.

The findings of the study, which was released ahead of its scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, build on a growing understanding of the relationship between types and qualities of urban environments and dementia risk.

Adithya Vegaraju, a student at Washington State University, Spokane, led the study, which looked at data from the Washington State Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System to assess prevalence of serious psychological distress among 42,980 Washington state residents aged 65 and over.

The data, collected between 2011 and 2019, used a self-reported questionnaire to determine serious psychological distress, which is defined as a level of mental distress considered debilitating enough to warrant treatment.

Mr. Vegaraju and his coauthor Solmaz Amiri, DDes, also of Washington State University, used ZIP codes, along with U.S. census data, to approximate the urban adults’ proximity to green and blue spaces.

After controlling for potential confounders of age, sex, ethnicity, education, and marital status, the investigators found that people living within half a mile of green or blue spaces had a 17% lower risk of experiencing serious psychological distress, compared with people living farther from these spaces, the investigators said in a news release.

Implications for cognitive decline and dementia?

Psychological distress in adults has been linked in population-based longitudinal studies to later cognitive decline and dementia. One study in older adults found the risk of dementia to be more than 50% higher among adults aged 50-70 with persistent depression. Blue and green spaces have also been investigated in relation to neurodegenerative disease among older adults; a 2022 study looking at data from some 62 million Medicare beneficiaries found those living in areas with more vegetation saw lower risk of hospitalizations for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

“Since we lack effective prevention methods or treatments for mild cognitive impairment and dementia, we need to get creative in how we look at these issues,” Dr. Amiri commented in a press statement about her and Mr. Vegaraju’s findings. “Our hope is that this study showing better mental health among people living close to parks and water will trigger other studies about how these benefits work and whether this proximity can help prevent or delay mild cognitive impairment and dementia.”

The investigators acknowledged that their findings were limited by reliance on a self-reported measure of psychological distress.

A bidirectional connection with depression and dementia

In a comment, Anjum Hajat, PhD, an epidemiologist at University of Washington School of Public Health in Seattle who has also studied the relationship between green space and dementia risk in older adults, noted some further apparent limitations of the new study, for which only an abstract was available at publication.

“It has been shown that people with depression are at higher risk for dementia, but the opposite is also true,” Dr. Hajat commented. “Those with dementia are more likely to develop depression. This bidirectionality makes this study abstract difficult to interpret since the study is based on cross-sectional data: Individuals are not followed over time to see which develops first, dementia or depression.”

Additionally, Dr. Hajat noted, the data used to determine proximity to green and blue spaces did not allow for the calculation of precise distances between subjects’ homes and these spaces.

Mr. Vegaraju and Dr. Amiri’s study had no outside support, and the investigators declared no conflicts of interest. Dr. Hajat declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM AAN 2023

New Medicare rule streamlines prior authorization in Medicare Advantage plans

A new federal rule seeks to reduce Medicare Advantage insurance plans’ prior authorization burdens on physicians while also ensuring that enrollees have the same access to necessary care that they would receive under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The prior authorization changes, announced this week, are part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 2024 update of policy changes for Medicare Advantage and Part D pharmacy plans

Medicare Advantage plans’ business practices have raised significant concerns in recent years. More than 28 million Americans were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2022, which is nearly half of all Medicare enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare pays a fixed amount per enrollee per year to these privately run managed care plans, in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have been criticized for aggressive marketing, for overbilling the federal government for care, and for using prior authorization to inappropriately deny needed care to patients.

About 13% of prior authorization requests that are denied by Medicare Advantage plans actually met Medicare coverage rules and should have been approved, the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported in 2022.

The newly finalized rule now requires Medicare Advantage plans to do the following.

- Ensure that a prior authorization approval, once granted, remains valid for as long as medically necessary to avoid disruptions in care.

- Conduct an annual review of utilization management policies.

- Ensure that coverage denials based on medical necessity be reviewed by health care professionals with relevant expertise before a denial can be issued.

Physician groups welcomed the changes. In a statement, the American Medical Association said that an initial reading of the rule suggested CMS had “taken important steps toward right-sizing the prior authorization process.”

The Medical Group Management Association praised CMS in a statement for having limited “dangerous disruptions and delays to necessary patient care” resulting from the cumbersome processes of prior approval. With the new rules, CMS will provide greater consistency across Advantage plans as well as traditional Medicare, said Anders Gilberg, MGMA’s senior vice president of government affairs, in a statement.

Peer consideration

The final rule did disappoint physician groups in one key way. CMS rebuffed requests to have CMS require Advantage plans to use reviewers of the same specialty as treating physicians in handling disputes about prior authorization. CMS said it expects plans to exercise judgment in finding reviewers with “sufficient expertise to make an informed and supportable decision.”

“In some instances, we expect that plans will use a physician or other health care professional of the same specialty or subspecialty as the treating physician,” CMS said. “In other instances, we expect that plans will utilize a reviewer with specialized training, certification, or clinical experience in the applicable field of medicine.”

Medicare Advantage marketing ‘sowing confusion’

With this final rule, CMS also sought to protect consumers from “potentially misleading marketing practices” used in promoting Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription drug plans.

The agency said it had received complaints about people who have received official-looking promotional materials for Medicare that directed them not to government sources of information but to Medicare Advantage and Part D plans or their agents and brokers.

Ads now must mention a specific plan name, and they cannot use the Medicare name, CMS logo, Medicare card, or other government information in a misleading way, CMS said.

“CMS can see no value or purpose in a non-governmental entity’s use of the Medicare logo or HHS logo except for the express purpose of sowing confusion and misrepresenting itself as the government,” the agency said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new federal rule seeks to reduce Medicare Advantage insurance plans’ prior authorization burdens on physicians while also ensuring that enrollees have the same access to necessary care that they would receive under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The prior authorization changes, announced this week, are part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 2024 update of policy changes for Medicare Advantage and Part D pharmacy plans

Medicare Advantage plans’ business practices have raised significant concerns in recent years. More than 28 million Americans were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2022, which is nearly half of all Medicare enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare pays a fixed amount per enrollee per year to these privately run managed care plans, in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have been criticized for aggressive marketing, for overbilling the federal government for care, and for using prior authorization to inappropriately deny needed care to patients.

About 13% of prior authorization requests that are denied by Medicare Advantage plans actually met Medicare coverage rules and should have been approved, the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported in 2022.

The newly finalized rule now requires Medicare Advantage plans to do the following.

- Ensure that a prior authorization approval, once granted, remains valid for as long as medically necessary to avoid disruptions in care.

- Conduct an annual review of utilization management policies.

- Ensure that coverage denials based on medical necessity be reviewed by health care professionals with relevant expertise before a denial can be issued.

Physician groups welcomed the changes. In a statement, the American Medical Association said that an initial reading of the rule suggested CMS had “taken important steps toward right-sizing the prior authorization process.”

The Medical Group Management Association praised CMS in a statement for having limited “dangerous disruptions and delays to necessary patient care” resulting from the cumbersome processes of prior approval. With the new rules, CMS will provide greater consistency across Advantage plans as well as traditional Medicare, said Anders Gilberg, MGMA’s senior vice president of government affairs, in a statement.

Peer consideration

The final rule did disappoint physician groups in one key way. CMS rebuffed requests to have CMS require Advantage plans to use reviewers of the same specialty as treating physicians in handling disputes about prior authorization. CMS said it expects plans to exercise judgment in finding reviewers with “sufficient expertise to make an informed and supportable decision.”

“In some instances, we expect that plans will use a physician or other health care professional of the same specialty or subspecialty as the treating physician,” CMS said. “In other instances, we expect that plans will utilize a reviewer with specialized training, certification, or clinical experience in the applicable field of medicine.”

Medicare Advantage marketing ‘sowing confusion’

With this final rule, CMS also sought to protect consumers from “potentially misleading marketing practices” used in promoting Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription drug plans.

The agency said it had received complaints about people who have received official-looking promotional materials for Medicare that directed them not to government sources of information but to Medicare Advantage and Part D plans or their agents and brokers.

Ads now must mention a specific plan name, and they cannot use the Medicare name, CMS logo, Medicare card, or other government information in a misleading way, CMS said.

“CMS can see no value or purpose in a non-governmental entity’s use of the Medicare logo or HHS logo except for the express purpose of sowing confusion and misrepresenting itself as the government,” the agency said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new federal rule seeks to reduce Medicare Advantage insurance plans’ prior authorization burdens on physicians while also ensuring that enrollees have the same access to necessary care that they would receive under traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

The prior authorization changes, announced this week, are part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ 2024 update of policy changes for Medicare Advantage and Part D pharmacy plans

Medicare Advantage plans’ business practices have raised significant concerns in recent years. More than 28 million Americans were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan in 2022, which is nearly half of all Medicare enrollees, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Medicare pays a fixed amount per enrollee per year to these privately run managed care plans, in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare. Medicare Advantage plans have been criticized for aggressive marketing, for overbilling the federal government for care, and for using prior authorization to inappropriately deny needed care to patients.

About 13% of prior authorization requests that are denied by Medicare Advantage plans actually met Medicare coverage rules and should have been approved, the Office of the Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services reported in 2022.

The newly finalized rule now requires Medicare Advantage plans to do the following.

- Ensure that a prior authorization approval, once granted, remains valid for as long as medically necessary to avoid disruptions in care.

- Conduct an annual review of utilization management policies.

- Ensure that coverage denials based on medical necessity be reviewed by health care professionals with relevant expertise before a denial can be issued.

Physician groups welcomed the changes. In a statement, the American Medical Association said that an initial reading of the rule suggested CMS had “taken important steps toward right-sizing the prior authorization process.”

The Medical Group Management Association praised CMS in a statement for having limited “dangerous disruptions and delays to necessary patient care” resulting from the cumbersome processes of prior approval. With the new rules, CMS will provide greater consistency across Advantage plans as well as traditional Medicare, said Anders Gilberg, MGMA’s senior vice president of government affairs, in a statement.

Peer consideration

The final rule did disappoint physician groups in one key way. CMS rebuffed requests to have CMS require Advantage plans to use reviewers of the same specialty as treating physicians in handling disputes about prior authorization. CMS said it expects plans to exercise judgment in finding reviewers with “sufficient expertise to make an informed and supportable decision.”

“In some instances, we expect that plans will use a physician or other health care professional of the same specialty or subspecialty as the treating physician,” CMS said. “In other instances, we expect that plans will utilize a reviewer with specialized training, certification, or clinical experience in the applicable field of medicine.”

Medicare Advantage marketing ‘sowing confusion’

With this final rule, CMS also sought to protect consumers from “potentially misleading marketing practices” used in promoting Medicare Advantage and Part D prescription drug plans.

The agency said it had received complaints about people who have received official-looking promotional materials for Medicare that directed them not to government sources of information but to Medicare Advantage and Part D plans or their agents and brokers.

Ads now must mention a specific plan name, and they cannot use the Medicare name, CMS logo, Medicare card, or other government information in a misleading way, CMS said.

“CMS can see no value or purpose in a non-governmental entity’s use of the Medicare logo or HHS logo except for the express purpose of sowing confusion and misrepresenting itself as the government,” the agency said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Picking up the premotor symptoms of Parkinson’s

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

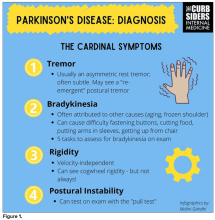

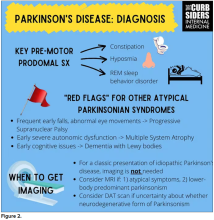

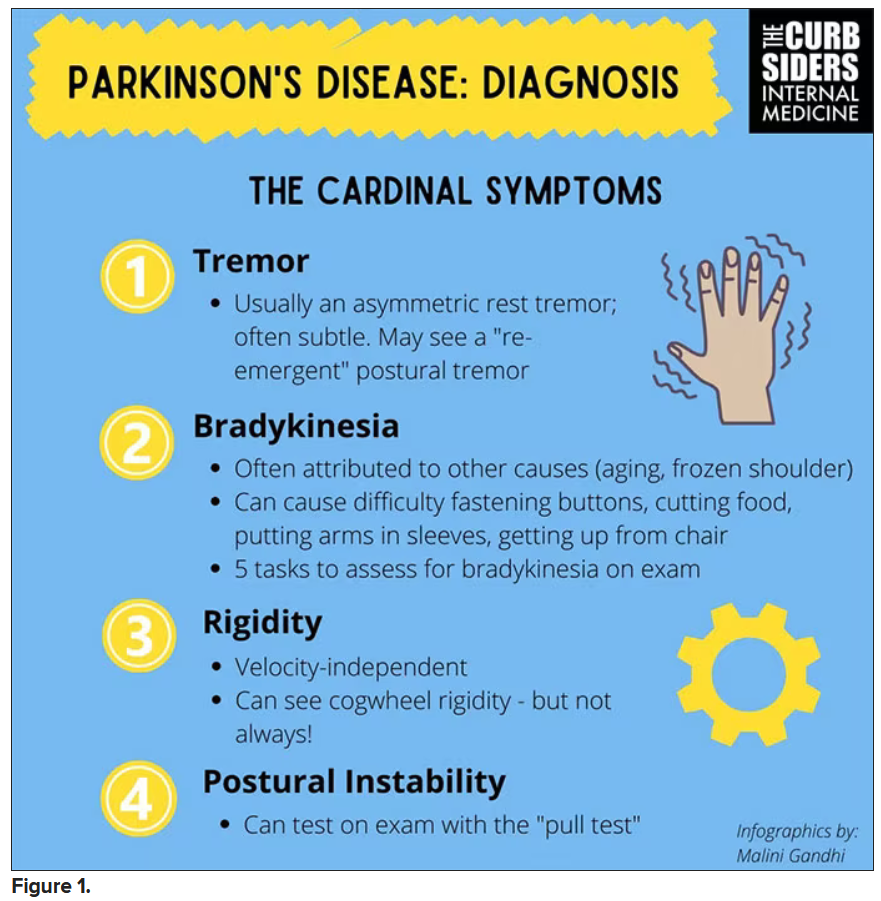

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

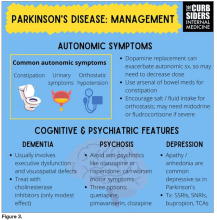

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. We had a great discussion on Parkinson’s Disease for Primary Care with Dr. Albert Hung. Paul, this was something that really made me nervous. I didn’t have a lot of comfort with it. But he taught us a lot of tips about how to recognize Parkinson’s.

I hadn’t been as aware of the premotor symptoms: constipation, hyposmia (loss of sense of smell), and rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. If patients have those early on and they aren’t explained by other things (especially the REM sleep behavior disorder), you should really key in because those patients are at risk of developing Parkinson’s years down the line. Those symptoms could present first, which just kind of blew my mind.

What tips do you have about how to recognize Parkinson’s? Do you want to talk about the physical exam?

Paul N. Williams, MD: You know I love the physical exam stuff, so I’m happy to talk about that.

You were deeply upset that cogwheel rigidity was not pathognomonic for Parkinson’s, but you made the point – and our guest agreed – that asymmetry tends to be the key here. And I really appreciated the point about reemergent tremor. This is this idea of a resting tremor. If someone has more parkinsonian features, you might see an intention tremor with essential tremor. If they reach out, it might seem steady at first, but if they hold long enough, then the tremor may kind of reemerge. I thought that was a neat distinction.

And this idea of cogwheel rigidity is a combination of some of the cardinal features of Parkinson’s – it’s a little bit of tremor and a little bit of rigidity too. There’s a baseline increase in tone, and then the tremor is superimposed on top of that. When you’re feeling cogwheeling, that’s actually what you’re feeling on examination. Parkinson’s, with all of its physical exam findings has always fascinated me.

Dr. Watto: He also told us about some red flags.

With classic idiopathic parkinsonism, there’s asymmetric involvement of the tremor. So red flags include a symmetric tremor, which might be something other than idiopathic parkinsonism. He also mentioned that one of the reasons you may want to get imaging (which is not always necessary if someone has a classic presentation), is if you see lower body–predominant symptoms of parkinsonism. These patients have rigidity or slowness of movement in their legs, but their upper bodies are not affected. They don’t have masked facies or the tremor in their hands. You might get an MRI in that case because that could be presentation of vascular dementia or vascular disease in the brain or even normal pressure hydrocephalus, which is a treatable condition. That would be one reason to get imaging.

What if the patient was exposed to a drug like a dopamine antagonist? They will get better in a couple of days, right?

Dr. Williams: This was a really fascinating point because we typically think if a patient’s symptoms are related to a drug exposure – in this case, drug-induced parkinsonism – we can just stop the medication and the symptoms will disappear in a couple of days as the drug leaves the system. But as it turns out, it might take much longer. A mistake that Dr Hung often sees is that the clinician stops the possibly offending agent, but when they don’t see an immediate relief of symptoms, they assume the drug wasn’t causing them. You really have to give the patient a fair shot off the medication to experience recovery because those symptoms can last weeks or even months after the drug is discontinued.

Dr. Watto: Dr Hung looks at the patient’s problem list and asks whether is there any reason this patient might have been exposed to one of these medications?

We’re not going to get too much into specific Parkinson’s treatment, but I was glad to hear that exercise actually improves mobility and may even have some neuroprotective effects. He mentioned ongoing trials looking at that. We always love an excuse to tell patients that they should be moving around more and being physically active.

Dr. Williams: That was one of the more shocking things I learned, that exercise might actually be good for you. That will deeply inform my practice. Many of the treatments that we use for Parkinson’s only address symptoms. They don’t address progression or fix anything, but exercise can help with that.

Dr. Watto: Paul, the last question I wanted to ask you is about our role in primary care. Patients with Parkinson’s have autonomic symptoms. They have neurocognitive symptoms. What is our role in that as primary care physicians?

Dr. Williams: Myriad symptoms can accompany Parkinson’s, and we have experience with most of them. We should all feel fairly comfortable dealing with constipation, which can be a very bothersome symptom. And we can use our full arsenal for symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and even apathy – the anhedonia, which apparently can be the predominant feature. We do have the tools to address these problems.

This might be a situation where we might reach for bupropion or a tricyclic antidepressant, which might not be your initial choice for a patient with a possibly annoying mood disorder. But for someone with Parkinson’s disease, this actually may be very helpful. We know how to manage a lot of the symptoms that come along with Parkinson’s that are not just the motor symptoms, and we should take ownership of those things.

Dr. Watto: You can hear the rest of this podcast here. This has been another episode of The Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I’ve been Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Dr. Williams: And I’m Dr Paul Nelson Williams.

Dr. Watto is a clinical assistant professor, department of medicine, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Williams is Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, at Temple University, Philadelphia. Neither Dr. Watto nor Dr. Williams reported any relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parkinson’s disease: What’s trauma got to do with it?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I’m happy to talk today to Dr. Indu Subramanian, clinical professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center in Los Angeles. I am a neurologist in Saratoga Springs, New York, and we will be talking today about Indu’s new paper on childhood trauma and Parkinson’s disease. Welcome and thanks for taking the time.

Indu Subramanian, MD: Thank you so much for letting us highlight this important topic.

Dr. LaFaver: There are many papers published every month on Parkinson’s disease, but this topic stands out because it’s not a thing that has been commonly looked at. What gave you the idea to study this?

Neurology behind other specialties

Dr. Subramanian: Kathrin, you and I have been looking at things that can inform us about our patients – the person who’s standing in front of us when they come in and we’re giving them this diagnosis. I think that so much of what we’ve done [in the past] is a cookie cutter approach to giving everybody the standard treatment. [We’ve been assuming that] It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman. It doesn’t matter if they’re a veteran. It doesn’t matter if they may be from a minoritized population.

We’ve also been interested in approaches that are outside the box, right? We have this integrative medicine and lifestyle medicine background. I’ve been going to those meetings and really been struck by the mounting evidence on the importance of things like early adverse childhood events (ACEs), what zip code you live in, what your pollution index is, and how these things can affect people through their life and their health.

I think that it is high time neurologists pay attention to this. There’s been mounting evidence throughout many disease states, various types of cancers, and mental health. Cardiology is much more advanced, but we haven’t had much data in neurology. In fact, when we went to write this paper, there were just one or two papers that were looking at multiple sclerosis or general neurologic issues, but really nothing in Parkinson’s disease.

We know that Parkinson’s disease is not only a motor disease that affects mental health, but that it also affects nonmotor issues. Childhood adversity may affect how people progress or how quickly they may get a disease, and we were interested in how it may manifest in a disease like Parkinson’s disease.

That was the framework going to meetings. As we wrote this paper and were in various editing stages, there was a beautiful paper that came out by Nadine Burke Harris and team that really was a call to action for neurologists and caring about trauma.

Dr. LaFaver: I couldn’t agree more. It’s really an underrecognized issue. With my own background, being very interested in functional movement disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and so on, it becomes much more evident how common a trauma background is, not only for people we were traditionally asking about.

Why don’t you summarize your findings for us?

Adverse childhood events

Dr. Subramanian: This is a web-based survey, so obviously, these are patient self-reports of their disease. We have a large cohort of people that we’ve been following over 7 years. I’m looking at modifiable variables and what really impacts Parkinson’s disease. Some of our previous papers have looked at diet, exercise, and loneliness. This is the same cohort.

We ended up putting the ACEs questionnaire, which is 10 questions looking at whether you were exposed to certain things in your household below the age of 18. This is a relatively standard questionnaire that’s administered one time, and you get a score out of 10. This is something that has been pushed, at least in the state of California, as something that we should be checking more in all people coming in.

We introduced the survey, and we didn’t force everyone to take it. Unfortunately, there was 20% or so of our patients who chose not to answer these questions. One has to ask, who are those people that didn’t answer the questions? Are they the ones that may have had trauma and these questions were triggering? It was a gap. We didn’t add extra questions to explore why people didn’t answer those questions.

We have to also put this in context. We have a patient population that’s largely quite affluent, who are able to access web-based surveys through their computer, and largely Caucasian; there are not many minoritized populations in our cohort. We want to do better with that. We actually were able to gather a decent number of women. We represent women quite well in our survey. I think that’s because of this online approach and some of the things that we’re studying.

In our survey, we broke it down into people who had no ACEs, one to three ACEs, or four or more ACEs. This is a standard way to break down ACEs so that we’re able to categorize what to do with these patient populations.

What we saw – and it’s preliminary evidence – is that people who had higher ACE scores seemed to have more symptom severity when we controlled for things like years since diagnosis, age, and gender. They also seem to have a worse quality of life. There was some indication that there were more nonmotor issues in those populations, as you might expect, such as anxiety, depression, and things that presumably ACEs can affect separately.

There are some confounders, but I think we really want to use this as the first piece of evidence to hopefully pave the way for caring about trauma in Parkinson’s disease moving forward.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you so much for that summary. You already mentioned the main methodology you used.

What is the next step for you? How do you see these findings informing our clinical care? Do you have suggestions for all of the neurologists listening in this regard?

PD not yet considered ACE-related

Dr. Subramanian: Dr. Burke Harris was the former surgeon general in California. She’s a woman of color and a brilliant speaker, and she had worked in inner cities, I think in San Francisco, with pediatric populations, seeing these effects of adversity in that time frame.

You see this population at risk, and then you’re following this cohort, which we knew from the Kaiser cohort determines earlier morbidity and mortality across a number of disease states. We’re seeing things like more heart attacks, more diabetes, and all kinds of things in these populations. This is not new news; we just have not been focusing on this.

In her paper, this call to action, they had talked about some ACE-related conditions that currently do not include Parkinson’s disease. There are three ACE-related neurologic conditions that people should be aware of. One is in the headache/pain universe. Another is in the stroke universe, and that’s understandable, given cardiovascular risk factors . Then the third is in this dementia risk category. I think Parkinson’s disease, as we know, can be associated with dementia. A large percentage of our patients get dementia, but we don’t have Parkinson’s disease called out in this framework.

What people are talking about is if you have no ACEs or are in this middle category of one to three ACEs and you don’t have an ACE-related diagnosis – which Parkinson’s disease is not currently – we just give some basic counseling about the importance of lifestyle. I think we would love to see that anyway. They’re talking about things like exercise, diet, sleep, social connection, getting out in nature, things like that, so just general counseling on the importance of that.

Then if you’re in this higher-risk category, and so with these ACE-related neurologic conditions, including dementia, headache, and stroke, if you had this middle range of one to three ACEs, they’re getting additional resources. Some of them may be referred for social work help or mental health support and things like that.

I’d really love to see that happening in Parkinson’s disease, because I think we have so many needs in our population. I’m always hoping to advocate for more mental health needs that are scarce and resources in the social support realm because I believe that social connection and social support is a huge buffer for this trauma.

ACEs are just one type of trauma. I take care of veterans in the Veterans [Affairs Department]. We have some information now coming out about posttraumatic stress disorder, predisposing to certain things in Parkinson’s disease, possibly head injury, and things like that. I think we have populations at risk that we can hopefully screen at intake, and I’m really pushing for that.

Maybe it’s not the neurologist that does this intake. It might be someone else on the team that can spend some time doing these questionnaires and understand if your patient has a high ACE score. Unless you ask, many patients don’t necessarily come forward to talk about this. I really am pushing for trying to screen and trying to advocate for more research in this area so that we can classify Parkinson’s disease as an ACE-related condition and thus give more resources from the mental health world, and also the social support world, to our patients.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you. There are many important points, and I think it’s a very important thing to recognize that it may not be only trauma in childhood but also throughout life, as you said, and might really influence nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in particular, including anxiety and pain, which are often difficult to treat.

I think there’s much more to do in research, advocacy, and education. We’re going to educate patients about this, and also educate other neurologists and providers. I think you mentioned that trauma-informed care is getting its spotlight in primary care and other specialties. I think we have catching up to do in neurology, and I think this is a really important work toward that goal.

Thank you so much for your work and for taking the time to share your thoughts. I hope to talk to you again soon.

Dr. Subramanian: Thank you so much, Kathrin.

Dr. LaFaver has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Subramanian disclosed ties with Acorda Therapeutics.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I’m happy to talk today to Dr. Indu Subramanian, clinical professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center in Los Angeles. I am a neurologist in Saratoga Springs, New York, and we will be talking today about Indu’s new paper on childhood trauma and Parkinson’s disease. Welcome and thanks for taking the time.

Indu Subramanian, MD: Thank you so much for letting us highlight this important topic.

Dr. LaFaver: There are many papers published every month on Parkinson’s disease, but this topic stands out because it’s not a thing that has been commonly looked at. What gave you the idea to study this?

Neurology behind other specialties

Dr. Subramanian: Kathrin, you and I have been looking at things that can inform us about our patients – the person who’s standing in front of us when they come in and we’re giving them this diagnosis. I think that so much of what we’ve done [in the past] is a cookie cutter approach to giving everybody the standard treatment. [We’ve been assuming that] It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman. It doesn’t matter if they’re a veteran. It doesn’t matter if they may be from a minoritized population.

We’ve also been interested in approaches that are outside the box, right? We have this integrative medicine and lifestyle medicine background. I’ve been going to those meetings and really been struck by the mounting evidence on the importance of things like early adverse childhood events (ACEs), what zip code you live in, what your pollution index is, and how these things can affect people through their life and their health.

I think that it is high time neurologists pay attention to this. There’s been mounting evidence throughout many disease states, various types of cancers, and mental health. Cardiology is much more advanced, but we haven’t had much data in neurology. In fact, when we went to write this paper, there were just one or two papers that were looking at multiple sclerosis or general neurologic issues, but really nothing in Parkinson’s disease.

We know that Parkinson’s disease is not only a motor disease that affects mental health, but that it also affects nonmotor issues. Childhood adversity may affect how people progress or how quickly they may get a disease, and we were interested in how it may manifest in a disease like Parkinson’s disease.

That was the framework going to meetings. As we wrote this paper and were in various editing stages, there was a beautiful paper that came out by Nadine Burke Harris and team that really was a call to action for neurologists and caring about trauma.

Dr. LaFaver: I couldn’t agree more. It’s really an underrecognized issue. With my own background, being very interested in functional movement disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and so on, it becomes much more evident how common a trauma background is, not only for people we were traditionally asking about.

Why don’t you summarize your findings for us?

Adverse childhood events

Dr. Subramanian: This is a web-based survey, so obviously, these are patient self-reports of their disease. We have a large cohort of people that we’ve been following over 7 years. I’m looking at modifiable variables and what really impacts Parkinson’s disease. Some of our previous papers have looked at diet, exercise, and loneliness. This is the same cohort.

We ended up putting the ACEs questionnaire, which is 10 questions looking at whether you were exposed to certain things in your household below the age of 18. This is a relatively standard questionnaire that’s administered one time, and you get a score out of 10. This is something that has been pushed, at least in the state of California, as something that we should be checking more in all people coming in.

We introduced the survey, and we didn’t force everyone to take it. Unfortunately, there was 20% or so of our patients who chose not to answer these questions. One has to ask, who are those people that didn’t answer the questions? Are they the ones that may have had trauma and these questions were triggering? It was a gap. We didn’t add extra questions to explore why people didn’t answer those questions.

We have to also put this in context. We have a patient population that’s largely quite affluent, who are able to access web-based surveys through their computer, and largely Caucasian; there are not many minoritized populations in our cohort. We want to do better with that. We actually were able to gather a decent number of women. We represent women quite well in our survey. I think that’s because of this online approach and some of the things that we’re studying.

In our survey, we broke it down into people who had no ACEs, one to three ACEs, or four or more ACEs. This is a standard way to break down ACEs so that we’re able to categorize what to do with these patient populations.

What we saw – and it’s preliminary evidence – is that people who had higher ACE scores seemed to have more symptom severity when we controlled for things like years since diagnosis, age, and gender. They also seem to have a worse quality of life. There was some indication that there were more nonmotor issues in those populations, as you might expect, such as anxiety, depression, and things that presumably ACEs can affect separately.

There are some confounders, but I think we really want to use this as the first piece of evidence to hopefully pave the way for caring about trauma in Parkinson’s disease moving forward.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you so much for that summary. You already mentioned the main methodology you used.

What is the next step for you? How do you see these findings informing our clinical care? Do you have suggestions for all of the neurologists listening in this regard?

PD not yet considered ACE-related

Dr. Subramanian: Dr. Burke Harris was the former surgeon general in California. She’s a woman of color and a brilliant speaker, and she had worked in inner cities, I think in San Francisco, with pediatric populations, seeing these effects of adversity in that time frame.

You see this population at risk, and then you’re following this cohort, which we knew from the Kaiser cohort determines earlier morbidity and mortality across a number of disease states. We’re seeing things like more heart attacks, more diabetes, and all kinds of things in these populations. This is not new news; we just have not been focusing on this.

In her paper, this call to action, they had talked about some ACE-related conditions that currently do not include Parkinson’s disease. There are three ACE-related neurologic conditions that people should be aware of. One is in the headache/pain universe. Another is in the stroke universe, and that’s understandable, given cardiovascular risk factors . Then the third is in this dementia risk category. I think Parkinson’s disease, as we know, can be associated with dementia. A large percentage of our patients get dementia, but we don’t have Parkinson’s disease called out in this framework.

What people are talking about is if you have no ACEs or are in this middle category of one to three ACEs and you don’t have an ACE-related diagnosis – which Parkinson’s disease is not currently – we just give some basic counseling about the importance of lifestyle. I think we would love to see that anyway. They’re talking about things like exercise, diet, sleep, social connection, getting out in nature, things like that, so just general counseling on the importance of that.

Then if you’re in this higher-risk category, and so with these ACE-related neurologic conditions, including dementia, headache, and stroke, if you had this middle range of one to three ACEs, they’re getting additional resources. Some of them may be referred for social work help or mental health support and things like that.

I’d really love to see that happening in Parkinson’s disease, because I think we have so many needs in our population. I’m always hoping to advocate for more mental health needs that are scarce and resources in the social support realm because I believe that social connection and social support is a huge buffer for this trauma.

ACEs are just one type of trauma. I take care of veterans in the Veterans [Affairs Department]. We have some information now coming out about posttraumatic stress disorder, predisposing to certain things in Parkinson’s disease, possibly head injury, and things like that. I think we have populations at risk that we can hopefully screen at intake, and I’m really pushing for that.

Maybe it’s not the neurologist that does this intake. It might be someone else on the team that can spend some time doing these questionnaires and understand if your patient has a high ACE score. Unless you ask, many patients don’t necessarily come forward to talk about this. I really am pushing for trying to screen and trying to advocate for more research in this area so that we can classify Parkinson’s disease as an ACE-related condition and thus give more resources from the mental health world, and also the social support world, to our patients.

Dr. LaFaver: Thank you. There are many important points, and I think it’s a very important thing to recognize that it may not be only trauma in childhood but also throughout life, as you said, and might really influence nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease in particular, including anxiety and pain, which are often difficult to treat.

I think there’s much more to do in research, advocacy, and education. We’re going to educate patients about this, and also educate other neurologists and providers. I think you mentioned that trauma-informed care is getting its spotlight in primary care and other specialties. I think we have catching up to do in neurology, and I think this is a really important work toward that goal.

Thank you so much for your work and for taking the time to share your thoughts. I hope to talk to you again soon.

Dr. Subramanian: Thank you so much, Kathrin.

Dr. LaFaver has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Subramanian disclosed ties with Acorda Therapeutics.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Kathrin LaFaver, MD: Hello. I’m happy to talk today to Dr. Indu Subramanian, clinical professor at University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Parkinson’s Disease Research, Education and Clinical Center in Los Angeles. I am a neurologist in Saratoga Springs, New York, and we will be talking today about Indu’s new paper on childhood trauma and Parkinson’s disease. Welcome and thanks for taking the time.

Indu Subramanian, MD: Thank you so much for letting us highlight this important topic.

Dr. LaFaver: There are many papers published every month on Parkinson’s disease, but this topic stands out because it’s not a thing that has been commonly looked at. What gave you the idea to study this?

Neurology behind other specialties

Dr. Subramanian: Kathrin, you and I have been looking at things that can inform us about our patients – the person who’s standing in front of us when they come in and we’re giving them this diagnosis. I think that so much of what we’ve done [in the past] is a cookie cutter approach to giving everybody the standard treatment. [We’ve been assuming that] It doesn’t matter if they’re a man or woman. It doesn’t matter if they’re a veteran. It doesn’t matter if they may be from a minoritized population.

We’ve also been interested in approaches that are outside the box, right? We have this integrative medicine and lifestyle medicine background. I’ve been going to those meetings and really been struck by the mounting evidence on the importance of things like early adverse childhood events (ACEs), what zip code you live in, what your pollution index is, and how these things can affect people through their life and their health.

I think that it is high time neurologists pay attention to this. There’s been mounting evidence throughout many disease states, various types of cancers, and mental health. Cardiology is much more advanced, but we haven’t had much data in neurology. In fact, when we went to write this paper, there were just one or two papers that were looking at multiple sclerosis or general neurologic issues, but really nothing in Parkinson’s disease.

We know that Parkinson’s disease is not only a motor disease that affects mental health, but that it also affects nonmotor issues. Childhood adversity may affect how people progress or how quickly they may get a disease, and we were interested in how it may manifest in a disease like Parkinson’s disease.

That was the framework going to meetings. As we wrote this paper and were in various editing stages, there was a beautiful paper that came out by Nadine Burke Harris and team that really was a call to action for neurologists and caring about trauma.

Dr. LaFaver: I couldn’t agree more. It’s really an underrecognized issue. With my own background, being very interested in functional movement disorders, psychosomatic disorders, and so on, it becomes much more evident how common a trauma background is, not only for people we were traditionally asking about.

Why don’t you summarize your findings for us?

Adverse childhood events