User login

VIDEO: Does genitourinary syndrome of menopause capture all the symptoms?

PHILADELPHIA – Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) replaced vulvovaginal atrophy in 2014 as a way to describe the changes to the genital and urinary tracts after menopause, but preliminary research shows it may be missing some symptoms.

In 2015, Amanda Clark, MD, a urogynecologist at the Kaiser Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and her colleagues surveyed women aged 55 years and older about their vulvar, vaginal, urinary, and sexual symptoms within 2 weeks of a well-woman visit to their primary care physician or gynecologist in the Kaiser system. In total, 1,533 provided valid data.

The researchers then used factor analysis to see if the symptoms matched up with GSM. If GSM is a true syndrome and only a single syndrome, then all of the factors would fit together in a one-factor model, Dr. Clark explained at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Instead, the researchers found that a three-factor model – with vulvovaginal symptoms of irritation and pain in one group, urinary symptoms in another group, and vaginal discharge and odor in a third group – fit best with the symptoms reported in their survey.

“This work is very preliminary and needs to be replicated in many other samples and looked at carefully,” Dr. Clark said in an interview. “But what we think is that genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a starting point.”

The study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and the North American Menopause Society. Dr. Clark reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) replaced vulvovaginal atrophy in 2014 as a way to describe the changes to the genital and urinary tracts after menopause, but preliminary research shows it may be missing some symptoms.

In 2015, Amanda Clark, MD, a urogynecologist at the Kaiser Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and her colleagues surveyed women aged 55 years and older about their vulvar, vaginal, urinary, and sexual symptoms within 2 weeks of a well-woman visit to their primary care physician or gynecologist in the Kaiser system. In total, 1,533 provided valid data.

The researchers then used factor analysis to see if the symptoms matched up with GSM. If GSM is a true syndrome and only a single syndrome, then all of the factors would fit together in a one-factor model, Dr. Clark explained at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Instead, the researchers found that a three-factor model – with vulvovaginal symptoms of irritation and pain in one group, urinary symptoms in another group, and vaginal discharge and odor in a third group – fit best with the symptoms reported in their survey.

“This work is very preliminary and needs to be replicated in many other samples and looked at carefully,” Dr. Clark said in an interview. “But what we think is that genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a starting point.”

The study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and the North American Menopause Society. Dr. Clark reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

PHILADELPHIA – Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) replaced vulvovaginal atrophy in 2014 as a way to describe the changes to the genital and urinary tracts after menopause, but preliminary research shows it may be missing some symptoms.

In 2015, Amanda Clark, MD, a urogynecologist at the Kaiser Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and her colleagues surveyed women aged 55 years and older about their vulvar, vaginal, urinary, and sexual symptoms within 2 weeks of a well-woman visit to their primary care physician or gynecologist in the Kaiser system. In total, 1,533 provided valid data.

The researchers then used factor analysis to see if the symptoms matched up with GSM. If GSM is a true syndrome and only a single syndrome, then all of the factors would fit together in a one-factor model, Dr. Clark explained at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society. Instead, the researchers found that a three-factor model – with vulvovaginal symptoms of irritation and pain in one group, urinary symptoms in another group, and vaginal discharge and odor in a third group – fit best with the symptoms reported in their survey.

“This work is very preliminary and needs to be replicated in many other samples and looked at carefully,” Dr. Clark said in an interview. “But what we think is that genitourinary syndrome of menopause is a starting point.”

The study was funded by a Pfizer Independent Grant for Learning & Change and the North American Menopause Society. Dr. Clark reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

AT NAMS 2017

Ciprofloxacin cured gyrA wild-type Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections

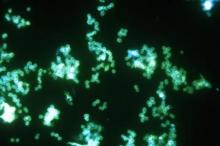

SAN DIEGO – Ciprofloxacin cured 100% of gyrase A wild-type Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, and physicians prescribed it significantly more frequently when they received electronic reminders of test results and recommendations, in a single-center study.

“Recent reports of untreatable gonorrhea have caused great concern. Treatment with ceftriaxone may be a major driver of resistance, and reducing its use may curb the emergence of resistant infections,” Lao-Tzu Allan-Blitz, a medical student at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae third among all drug-resistant threats in the United States, Mr. Allan-Blitz noted during an oral presentation at the meeting. Beginning in the late 1990s, strains of N. gonorrhoeae developed resistance to sulfanilamides, penicillin, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones, leaving only the extended-spectrum cephalosporins for empiric treatment. Recent reports of cephalosporin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in other countries have raised the specter of untreatable gonorrhea.

Because antimicrobial resistance can shift in response to selective pressure, experts are exploring the use of antibiotics once considered ineffective for treating N. gonorrhoeae infections. At UCLA, researchers developed a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test for a mutation of codon 91 in the gyrase A (gyrA) gene in N. gonorrhoeae that reliably predicts resistance to ciprofloxacin.

Test results take 24-48 hours. The test is not Food and Drug Administration approved but has been validated in accordance with Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, Mr. Allan-Blitz said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

In November 2015, UCLA Health began gyrA genotyping all N. gonorrhoeae positive specimens, and in May 2016, it began sending providers electronic reminders of genotype results and treatment recommendations. For gyrA wild-type infections, UCLA Health recommends 500 mg oral ciprofloxacin, Mr. Allan-Blitz said.

Initial test-of-cure data are promising. All 25 patients with wild-type infections who received ciprofloxacin and returned 7-90 days later tested negative for N. gonorrhoeae. Culture sites included the urethra (seven cases), pharynx (seven cases), rectum (seven cases), and genitals (four cases), Mr. Allan-Blitz said. “Prior studies have demonstrated that reminder notifications improve uptake of antimicrobial stewardship,” he said. “Other health centers should consider implementing the gyrA assay, and using reminder notifications may improve uptake by providers.”

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Ciprofloxacin cured 100% of gyrase A wild-type Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, and physicians prescribed it significantly more frequently when they received electronic reminders of test results and recommendations, in a single-center study.

“Recent reports of untreatable gonorrhea have caused great concern. Treatment with ceftriaxone may be a major driver of resistance, and reducing its use may curb the emergence of resistant infections,” Lao-Tzu Allan-Blitz, a medical student at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae third among all drug-resistant threats in the United States, Mr. Allan-Blitz noted during an oral presentation at the meeting. Beginning in the late 1990s, strains of N. gonorrhoeae developed resistance to sulfanilamides, penicillin, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones, leaving only the extended-spectrum cephalosporins for empiric treatment. Recent reports of cephalosporin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in other countries have raised the specter of untreatable gonorrhea.

Because antimicrobial resistance can shift in response to selective pressure, experts are exploring the use of antibiotics once considered ineffective for treating N. gonorrhoeae infections. At UCLA, researchers developed a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test for a mutation of codon 91 in the gyrase A (gyrA) gene in N. gonorrhoeae that reliably predicts resistance to ciprofloxacin.

Test results take 24-48 hours. The test is not Food and Drug Administration approved but has been validated in accordance with Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, Mr. Allan-Blitz said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

In November 2015, UCLA Health began gyrA genotyping all N. gonorrhoeae positive specimens, and in May 2016, it began sending providers electronic reminders of genotype results and treatment recommendations. For gyrA wild-type infections, UCLA Health recommends 500 mg oral ciprofloxacin, Mr. Allan-Blitz said.

Initial test-of-cure data are promising. All 25 patients with wild-type infections who received ciprofloxacin and returned 7-90 days later tested negative for N. gonorrhoeae. Culture sites included the urethra (seven cases), pharynx (seven cases), rectum (seven cases), and genitals (four cases), Mr. Allan-Blitz said. “Prior studies have demonstrated that reminder notifications improve uptake of antimicrobial stewardship,” he said. “Other health centers should consider implementing the gyrA assay, and using reminder notifications may improve uptake by providers.”

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Ciprofloxacin cured 100% of gyrase A wild-type Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections, and physicians prescribed it significantly more frequently when they received electronic reminders of test results and recommendations, in a single-center study.

“Recent reports of untreatable gonorrhea have caused great concern. Treatment with ceftriaxone may be a major driver of resistance, and reducing its use may curb the emergence of resistant infections,” Lao-Tzu Allan-Blitz, a medical student at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks multidrug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae third among all drug-resistant threats in the United States, Mr. Allan-Blitz noted during an oral presentation at the meeting. Beginning in the late 1990s, strains of N. gonorrhoeae developed resistance to sulfanilamides, penicillin, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones, leaving only the extended-spectrum cephalosporins for empiric treatment. Recent reports of cephalosporin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae in other countries have raised the specter of untreatable gonorrhea.

Because antimicrobial resistance can shift in response to selective pressure, experts are exploring the use of antibiotics once considered ineffective for treating N. gonorrhoeae infections. At UCLA, researchers developed a real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction test for a mutation of codon 91 in the gyrase A (gyrA) gene in N. gonorrhoeae that reliably predicts resistance to ciprofloxacin.

Test results take 24-48 hours. The test is not Food and Drug Administration approved but has been validated in accordance with Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments, Mr. Allan-Blitz said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

In November 2015, UCLA Health began gyrA genotyping all N. gonorrhoeae positive specimens, and in May 2016, it began sending providers electronic reminders of genotype results and treatment recommendations. For gyrA wild-type infections, UCLA Health recommends 500 mg oral ciprofloxacin, Mr. Allan-Blitz said.

Initial test-of-cure data are promising. All 25 patients with wild-type infections who received ciprofloxacin and returned 7-90 days later tested negative for N. gonorrhoeae. Culture sites included the urethra (seven cases), pharynx (seven cases), rectum (seven cases), and genitals (four cases), Mr. Allan-Blitz said. “Prior studies have demonstrated that reminder notifications improve uptake of antimicrobial stewardship,” he said. “Other health centers should consider implementing the gyrA assay, and using reminder notifications may improve uptake by providers.”

The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT IDWEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The cure rate was 100% among 25 patients who received ciprofloxacin for wild-type gyrA gonorrhea.

Data source: A single-center study of 582 patients with gonorrhea.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided funding. The investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

Oral bioidentical combo improves quality of life, vasomotor symptoms

PHILADELPHIA – An oral estradiol/progesterone formulation significantly improved menopause-related quality of life, compared with placebo, for up to 1 year after beginning treatment, according to a new study.

If approved, the new formulation “may be an option for the estimated millions of women currently using less-regulated and unapproved compounded bioidentical hormone therapy,” said James Simon, MD, the study’s senior author.

Patients receiving the combination therapy, termed TX-001HR, experienced a significant improvement in quality of life, compared with placebo and compared with baseline, at all study points, said Dr. Simon of George Washington University, Washington.

Using the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire (MENQOL), Dr. Simon and his coinvestigators found that women taking the combination therapy saw reductions in the vasomotor domain of MENQOL within 12 weeks of beginning the study. The significant symptomatic improvement persisted for the full year that patients were followed.

For patients with particularly bothersome vasomotor symptoms, vasomotor domain scores ranged from 6.9 to 7.2 at baseline and were 2.8-3.6 with TX-001HR and 4.4 with placebo at month 12, according to Dr. Simon.

Speaking during a top abstracts session at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Simon said that TX-001HR combines the physiologic sex hormones 17-beta estradiol and progesterone (E2/P4) into a single oral soft-gel.

The phase 3 randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled REPLENISH trial explored the safety and efficacy of one of four dose combinations of E2/P4. A total of 1,833 patients were randomized to receive E2/P4 in doses of 1.0/100 mg, 0.5/100 mg, 0.5/50 mg, or 0.25/50 mg, or to receive placebo. An approximately equal number of patients were allocated to each study arm, except that 151 patients were allocated to receive placebo.

The MENQOL is structured so that the 29 items in the symptom inventory are grouped into four domains: vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual. Significant reductions were seen at 12 weeks for all patients in overall MENQOL scores and for the four domains.

The REPLENISH investigators also performed a separate analysis of data from the subset of patients who had moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS). At the 6- and 12-month assessment points, the VMS patients on all but the lowest dose of TX-001HR had significant improvement over placebo.

“Independent of treatment, the largest correlation observed was between changes in moderate to severe VMS frequency and changes in the MENQOL vasomotor symptom domain score at 12 weeks,” said Dr. Simon. The quality of life and moderate to severe VMS frequency were highly correlated, he added (rho = 0.561, P less than .0001). Improvements in the other MENQOL domains were also highly correlated with reduction in moderate to severe frequency (P less than .0001 for all).

Among patients who reported significant improvement on the MENQOL, said Dr. Simon, more of the TX-001HR patients had improvements that were judged to be clinically significant compared to those taking placebo. Women who experienced a minimal clinically important difference in their symptoms had a weekly improvement of 34 fewer VMS events. Those who had a stronger response, which was judged to be clinically important, had a weekly improvement of 44 fewer VMS events.

Dr. Simon reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including TherapeuticsMD, the sponsor of the THX-001HR clinical trials.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

PHILADELPHIA – An oral estradiol/progesterone formulation significantly improved menopause-related quality of life, compared with placebo, for up to 1 year after beginning treatment, according to a new study.

If approved, the new formulation “may be an option for the estimated millions of women currently using less-regulated and unapproved compounded bioidentical hormone therapy,” said James Simon, MD, the study’s senior author.

Patients receiving the combination therapy, termed TX-001HR, experienced a significant improvement in quality of life, compared with placebo and compared with baseline, at all study points, said Dr. Simon of George Washington University, Washington.

Using the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire (MENQOL), Dr. Simon and his coinvestigators found that women taking the combination therapy saw reductions in the vasomotor domain of MENQOL within 12 weeks of beginning the study. The significant symptomatic improvement persisted for the full year that patients were followed.

For patients with particularly bothersome vasomotor symptoms, vasomotor domain scores ranged from 6.9 to 7.2 at baseline and were 2.8-3.6 with TX-001HR and 4.4 with placebo at month 12, according to Dr. Simon.

Speaking during a top abstracts session at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Simon said that TX-001HR combines the physiologic sex hormones 17-beta estradiol and progesterone (E2/P4) into a single oral soft-gel.

The phase 3 randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled REPLENISH trial explored the safety and efficacy of one of four dose combinations of E2/P4. A total of 1,833 patients were randomized to receive E2/P4 in doses of 1.0/100 mg, 0.5/100 mg, 0.5/50 mg, or 0.25/50 mg, or to receive placebo. An approximately equal number of patients were allocated to each study arm, except that 151 patients were allocated to receive placebo.

The MENQOL is structured so that the 29 items in the symptom inventory are grouped into four domains: vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual. Significant reductions were seen at 12 weeks for all patients in overall MENQOL scores and for the four domains.

The REPLENISH investigators also performed a separate analysis of data from the subset of patients who had moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS). At the 6- and 12-month assessment points, the VMS patients on all but the lowest dose of TX-001HR had significant improvement over placebo.

“Independent of treatment, the largest correlation observed was between changes in moderate to severe VMS frequency and changes in the MENQOL vasomotor symptom domain score at 12 weeks,” said Dr. Simon. The quality of life and moderate to severe VMS frequency were highly correlated, he added (rho = 0.561, P less than .0001). Improvements in the other MENQOL domains were also highly correlated with reduction in moderate to severe frequency (P less than .0001 for all).

Among patients who reported significant improvement on the MENQOL, said Dr. Simon, more of the TX-001HR patients had improvements that were judged to be clinically significant compared to those taking placebo. Women who experienced a minimal clinically important difference in their symptoms had a weekly improvement of 34 fewer VMS events. Those who had a stronger response, which was judged to be clinically important, had a weekly improvement of 44 fewer VMS events.

Dr. Simon reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including TherapeuticsMD, the sponsor of the THX-001HR clinical trials.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

PHILADELPHIA – An oral estradiol/progesterone formulation significantly improved menopause-related quality of life, compared with placebo, for up to 1 year after beginning treatment, according to a new study.

If approved, the new formulation “may be an option for the estimated millions of women currently using less-regulated and unapproved compounded bioidentical hormone therapy,” said James Simon, MD, the study’s senior author.

Patients receiving the combination therapy, termed TX-001HR, experienced a significant improvement in quality of life, compared with placebo and compared with baseline, at all study points, said Dr. Simon of George Washington University, Washington.

Using the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire (MENQOL), Dr. Simon and his coinvestigators found that women taking the combination therapy saw reductions in the vasomotor domain of MENQOL within 12 weeks of beginning the study. The significant symptomatic improvement persisted for the full year that patients were followed.

For patients with particularly bothersome vasomotor symptoms, vasomotor domain scores ranged from 6.9 to 7.2 at baseline and were 2.8-3.6 with TX-001HR and 4.4 with placebo at month 12, according to Dr. Simon.

Speaking during a top abstracts session at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Simon said that TX-001HR combines the physiologic sex hormones 17-beta estradiol and progesterone (E2/P4) into a single oral soft-gel.

The phase 3 randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled REPLENISH trial explored the safety and efficacy of one of four dose combinations of E2/P4. A total of 1,833 patients were randomized to receive E2/P4 in doses of 1.0/100 mg, 0.5/100 mg, 0.5/50 mg, or 0.25/50 mg, or to receive placebo. An approximately equal number of patients were allocated to each study arm, except that 151 patients were allocated to receive placebo.

The MENQOL is structured so that the 29 items in the symptom inventory are grouped into four domains: vasomotor, psychosocial, physical, and sexual. Significant reductions were seen at 12 weeks for all patients in overall MENQOL scores and for the four domains.

The REPLENISH investigators also performed a separate analysis of data from the subset of patients who had moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS). At the 6- and 12-month assessment points, the VMS patients on all but the lowest dose of TX-001HR had significant improvement over placebo.

“Independent of treatment, the largest correlation observed was between changes in moderate to severe VMS frequency and changes in the MENQOL vasomotor symptom domain score at 12 weeks,” said Dr. Simon. The quality of life and moderate to severe VMS frequency were highly correlated, he added (rho = 0.561, P less than .0001). Improvements in the other MENQOL domains were also highly correlated with reduction in moderate to severe frequency (P less than .0001 for all).

Among patients who reported significant improvement on the MENQOL, said Dr. Simon, more of the TX-001HR patients had improvements that were judged to be clinically significant compared to those taking placebo. Women who experienced a minimal clinically important difference in their symptoms had a weekly improvement of 34 fewer VMS events. Those who had a stronger response, which was judged to be clinically important, had a weekly improvement of 44 fewer VMS events.

Dr. Simon reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including TherapeuticsMD, the sponsor of the THX-001HR clinical trials.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT NAMS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients taking TX-100HR had significant improvements in a menopause-related quality of life scale at all study time points.

Data source: REPLENISH, a phase 3, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study of 1,833 postmenopausal women.

Disclosures: Dr. Simon reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, including TherapeuticsMD, sponsor of the REPLENISH trial.

Syphilis rates reach record high

It’s too soon to discard cotesting in cervical cancer

In their new cervical cancer screening draft recommendation statement, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for cervical cancer every 3 years with cervical cytology alone in women aged 21-29 years, and either continuing 3-year cytology screening or 5-year high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) screening in women aged 30-65 years.1 They arrived at the conclusion primarily based on an analysis of benefits and harms of each of the currently used screening modalities. Cytology plus HPV cotesting was considered but rejected based on the benefits versus harms calculations. However, some of the assumptions in their modeling are wrong and this has led them to faulty conclusions.

The USPSTF correctly identified CIN-2/3 and CIN-3+ detected and cervical cancer cases and deaths prevented as benefits. But they used the number of colposcopies and the number of tests conducted as their proxy for harms, primarily because these were more easily measured. They identified other harms, such as greater psychological distress related to being told of a positive HPV result (compared with being told of an abnormal cytology or cotest result), but these harms were not numerical and so they could not be incorporated into their modeling. They also did not measure the psychological distress associated with an extended screening interval or HPV-only screening.

The USPSTF also primarily relied on evidence from seven large, randomly controlled trials of primary screening, mostly conducted in Europe.3 Of the seven trials, two of them (SWEDESCREEN and POBASCAM) used HPV testing by a polymerase chain reaction methodology that is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, not commercially available in the United States, and has different sensitivity and specificity does than FDA-approved tests.

Most of the studies also were done with conventional cytology that is, for the most part, no longer used in the United States. The age range in some of the studies was also very narrow (SWEDESCREEN evaluated women aged 32-38 years only) while extending to very young ages in others (ARTISTIC evaluated women as young as age 20 years). It may not be possible to extrapolate from these results to the U.S. experience. On the other hand, the USPSTF elected not to use data from very large retrospective U.S. trials, such as the data from more than 1 million women from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, which helped form the foundation of current guidelines.4

Although screening has dramatically reduced the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States, most screening in this country is opportunistic and lacks population-based registries or regular invitations to screening. The USPSTF notes that a sizable proportion of the U.S.-based female population is not routinely screened. In fact, 11.4% of 21- to 65-year-old women have not been screened in the previous 5 years and the percentages are higher among minority and disadvantaged populations. Although the numbers seem relatively small, more than half of women with cervical cancer are found in this population. These women also are at greater risk of being lost to follow-up. Unlike the patients in the European trials, there is no current mechanism in the United States to assure that patients will return in 5 years. In fact, the USPSTF notes this limitation in their evidence, but doesn’t provide a remedy. These women may not get rescreened for many years after the 5-year interval has passed, and there is no evidence that this interval is safe.

Finally, the USPSTF recommendations for HPV primary screening relied in whole or in part on cytology triage of positive results. There is no U.S. experience for the use of cytology within this context, and many experts have argued that the test performance of cytology in a triage setting would be different than in a screening setting and would further be different in a vaccinated population. Since the modeling on which these draft recommendations are based did not account for these changed performance characteristics, their assumptions must be wrong.

Five years have not yet passed since publication of the last set of guidelines, and we have no idea how this extended screening interval functions in our opportunistic screening system. Stated simply, these draft recommendations have gone too far and too fast and should be reconsidered.

Dr. Spitzer is a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Hempstead, N.Y., and a past president of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. He reported receiving royalties from Elsevier, and consulting fees from Hologic, Biop Medical, Illumigen, and Merck.

References

1. Draft Recommendation Statement: Cervical Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. September 2017.

2. Screening for Cervical Cancer in Primary Care: A Decision Analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2017.

3. Screening for Cervical Cancer With High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Testing: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2017.

4. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Jul 18;106(8). pii: dju153.

In their new cervical cancer screening draft recommendation statement, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for cervical cancer every 3 years with cervical cytology alone in women aged 21-29 years, and either continuing 3-year cytology screening or 5-year high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) screening in women aged 30-65 years.1 They arrived at the conclusion primarily based on an analysis of benefits and harms of each of the currently used screening modalities. Cytology plus HPV cotesting was considered but rejected based on the benefits versus harms calculations. However, some of the assumptions in their modeling are wrong and this has led them to faulty conclusions.

The USPSTF correctly identified CIN-2/3 and CIN-3+ detected and cervical cancer cases and deaths prevented as benefits. But they used the number of colposcopies and the number of tests conducted as their proxy for harms, primarily because these were more easily measured. They identified other harms, such as greater psychological distress related to being told of a positive HPV result (compared with being told of an abnormal cytology or cotest result), but these harms were not numerical and so they could not be incorporated into their modeling. They also did not measure the psychological distress associated with an extended screening interval or HPV-only screening.

The USPSTF also primarily relied on evidence from seven large, randomly controlled trials of primary screening, mostly conducted in Europe.3 Of the seven trials, two of them (SWEDESCREEN and POBASCAM) used HPV testing by a polymerase chain reaction methodology that is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, not commercially available in the United States, and has different sensitivity and specificity does than FDA-approved tests.

Most of the studies also were done with conventional cytology that is, for the most part, no longer used in the United States. The age range in some of the studies was also very narrow (SWEDESCREEN evaluated women aged 32-38 years only) while extending to very young ages in others (ARTISTIC evaluated women as young as age 20 years). It may not be possible to extrapolate from these results to the U.S. experience. On the other hand, the USPSTF elected not to use data from very large retrospective U.S. trials, such as the data from more than 1 million women from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, which helped form the foundation of current guidelines.4

Although screening has dramatically reduced the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States, most screening in this country is opportunistic and lacks population-based registries or regular invitations to screening. The USPSTF notes that a sizable proportion of the U.S.-based female population is not routinely screened. In fact, 11.4% of 21- to 65-year-old women have not been screened in the previous 5 years and the percentages are higher among minority and disadvantaged populations. Although the numbers seem relatively small, more than half of women with cervical cancer are found in this population. These women also are at greater risk of being lost to follow-up. Unlike the patients in the European trials, there is no current mechanism in the United States to assure that patients will return in 5 years. In fact, the USPSTF notes this limitation in their evidence, but doesn’t provide a remedy. These women may not get rescreened for many years after the 5-year interval has passed, and there is no evidence that this interval is safe.

Finally, the USPSTF recommendations for HPV primary screening relied in whole or in part on cytology triage of positive results. There is no U.S. experience for the use of cytology within this context, and many experts have argued that the test performance of cytology in a triage setting would be different than in a screening setting and would further be different in a vaccinated population. Since the modeling on which these draft recommendations are based did not account for these changed performance characteristics, their assumptions must be wrong.

Five years have not yet passed since publication of the last set of guidelines, and we have no idea how this extended screening interval functions in our opportunistic screening system. Stated simply, these draft recommendations have gone too far and too fast and should be reconsidered.

Dr. Spitzer is a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Hempstead, N.Y., and a past president of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. He reported receiving royalties from Elsevier, and consulting fees from Hologic, Biop Medical, Illumigen, and Merck.

References

1. Draft Recommendation Statement: Cervical Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. September 2017.

2. Screening for Cervical Cancer in Primary Care: A Decision Analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2017.

3. Screening for Cervical Cancer With High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Testing: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2017.

4. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Jul 18;106(8). pii: dju153.

In their new cervical cancer screening draft recommendation statement, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for cervical cancer every 3 years with cervical cytology alone in women aged 21-29 years, and either continuing 3-year cytology screening or 5-year high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) screening in women aged 30-65 years.1 They arrived at the conclusion primarily based on an analysis of benefits and harms of each of the currently used screening modalities. Cytology plus HPV cotesting was considered but rejected based on the benefits versus harms calculations. However, some of the assumptions in their modeling are wrong and this has led them to faulty conclusions.

The USPSTF correctly identified CIN-2/3 and CIN-3+ detected and cervical cancer cases and deaths prevented as benefits. But they used the number of colposcopies and the number of tests conducted as their proxy for harms, primarily because these were more easily measured. They identified other harms, such as greater psychological distress related to being told of a positive HPV result (compared with being told of an abnormal cytology or cotest result), but these harms were not numerical and so they could not be incorporated into their modeling. They also did not measure the psychological distress associated with an extended screening interval or HPV-only screening.

The USPSTF also primarily relied on evidence from seven large, randomly controlled trials of primary screening, mostly conducted in Europe.3 Of the seven trials, two of them (SWEDESCREEN and POBASCAM) used HPV testing by a polymerase chain reaction methodology that is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, not commercially available in the United States, and has different sensitivity and specificity does than FDA-approved tests.

Most of the studies also were done with conventional cytology that is, for the most part, no longer used in the United States. The age range in some of the studies was also very narrow (SWEDESCREEN evaluated women aged 32-38 years only) while extending to very young ages in others (ARTISTIC evaluated women as young as age 20 years). It may not be possible to extrapolate from these results to the U.S. experience. On the other hand, the USPSTF elected not to use data from very large retrospective U.S. trials, such as the data from more than 1 million women from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, which helped form the foundation of current guidelines.4

Although screening has dramatically reduced the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States, most screening in this country is opportunistic and lacks population-based registries or regular invitations to screening. The USPSTF notes that a sizable proportion of the U.S.-based female population is not routinely screened. In fact, 11.4% of 21- to 65-year-old women have not been screened in the previous 5 years and the percentages are higher among minority and disadvantaged populations. Although the numbers seem relatively small, more than half of women with cervical cancer are found in this population. These women also are at greater risk of being lost to follow-up. Unlike the patients in the European trials, there is no current mechanism in the United States to assure that patients will return in 5 years. In fact, the USPSTF notes this limitation in their evidence, but doesn’t provide a remedy. These women may not get rescreened for many years after the 5-year interval has passed, and there is no evidence that this interval is safe.

Finally, the USPSTF recommendations for HPV primary screening relied in whole or in part on cytology triage of positive results. There is no U.S. experience for the use of cytology within this context, and many experts have argued that the test performance of cytology in a triage setting would be different than in a screening setting and would further be different in a vaccinated population. Since the modeling on which these draft recommendations are based did not account for these changed performance characteristics, their assumptions must be wrong.

Five years have not yet passed since publication of the last set of guidelines, and we have no idea how this extended screening interval functions in our opportunistic screening system. Stated simply, these draft recommendations have gone too far and too fast and should be reconsidered.

Dr. Spitzer is a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Hempstead, N.Y., and a past president of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. He reported receiving royalties from Elsevier, and consulting fees from Hologic, Biop Medical, Illumigen, and Merck.

References

1. Draft Recommendation Statement: Cervical Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. September 2017.

2. Screening for Cervical Cancer in Primary Care: A Decision Analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2017.

3. Screening for Cervical Cancer With High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Testing: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. 2017.

4. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Jul 18;106(8). pii: dju153.

Approaching intraoperative bowel injury

Enterotomy can be a serious complication in abdominopelvic surgery, particularly if it is not immediately recognized and treated. Risk of visceral injury increases when complex dissection is required for treatment of cancer, resection of endometriosis, and extensive lysis of adhesions.

In a retrospective review from 1984 to 2003, investigators assessed intestinal injuries at the time of gynecologic operations. Of the 110 cases reported, about 37% occurred during the opening of the peritoneal cavity, 38% during adhesiolysis and pelvic dissection, 9% during laparoscopy, 9% during vaginal surgery, and 8% during dilation and curettage. Of the bowel injuries, more than 75% were minor.1 Mortality from unrecognized bowel injury is significant, and as such, appropriate recognition and management of these injuries is critical.2

Some basic principles are critical when surgeons face a bowel injury:

1. Recognize the extent of the injury, including the size of the breach, the depth (full or partial thickness), and the nature of the injury (thermal or cold).

2. Assess the integrity of the bowel, including adequacy of blood supply, prior bowel damage from radiation, and absence of downstream obstruction.

3. Ensure no other occult injuries exist in other segments.

4. Obtain adequate exposure and mobilization of the bowel beyond the site of injury, including the adjacent bowel. This involves releasing other adhesions so that adequate bowel length is available for a tension-free repair.

Methods of repair

The decision to employ each is influenced by multiple factors. Primary closure is best suited to small lesions (1 cm or less) that are a result of cold or sharp injury. However, thermal injury sustained via electrosurgical devices induces delayed tissue damage beyond the visible edges of the immediate defect, and surgeons should consider a resection of bowel to at least 1 cm beyond the immediately apparent injury site. Additionally, resection and re-anastamosis should also be considered if the damaged segment of bowel has poor blood supply, integrity, or the repair would result in tension along the suture/staple line or luminal narrowing.

Simple small bowel closures

Serosal abrasions need not be repaired; however, small tears of the serosa and muscularis can be managed with a single layer of interrupted 3-0 absorbable or permanent silk suture on a tapered needle. The suture line should be perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bowel at 2-mm to 3-mm intervals in order to prevent narrowing of the lumen. The suture should pass through serosal and muscular layers in an imbricating (Lembert) stitch. For smaller defects of less than 6 mm, a single layer closure is typically adequate.

Small bowel resection

Some larger defects, thermal injuries, and segments with multiple enterotomies may be best repaired with resection and re-anastamosis technique. A segment of resectable bowel is chosen such that the afferent and efferent limbs to be re-anastamosed can be reapproximated in a tension-free fashion. A mesenterotomy is made at the proximal and distal portions of the involved bowel. A gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is then inserted perpendicularly across the bowel. The remaining wedge of connected mesentery can then be efficiently excised with an electrothermal bipolar coagulator device ensuring that maximal mesentery and blood supply are preserved to the remaining limbs of intestine. The proximal and distal segments are then aligned at the antimesenteric sides.

Large bowel repair

Defects in the serosa and small lacerations can be managed with a primary closure, similar to the small intestine. For more extensive injuries that may require resection, diversion, or complicated repair, consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or general or colorectal surgeon may be indicated as colotomy repairs are associated with higher rates of breakdown and fistula. If fecal contamination is present, copious irrigation should be performed and placement of a peritoneal drain to reduce the likelihood of abscess formation should be considered. If appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for colonic surgery has not been given prior to skin incision, it should be administered once the colotomy is identified.

Standard prophylaxis for hysterectomy (such as a first-generation cephalosporin like cefazolin) is not adequate for large bowel surgery, and either metronidazole should be added or a second-generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin should be given. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin with either gentamicin or a fluoroquinolone should be administered.6

Postoperative management

The potential for postoperative morbidity must be understood for appropriate management following bowel surgery. Ileus is common and the clinician should understand how to diagnose and manage it. Additionally, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, fistula formation, and mechanical obstruction are complications that may require surgical intervention and must be vigilantly managed.

The routine use of postoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) does not hasten return of bowel function or prevent leak from sites of gastrointestinal repair. In fact, early feeding has been associated with reduced perioperative complications and earlier return of bowel function has been observed without the use of NGT.7 In general, for small and large intestinal injuries, early feeding is considered acceptable.8

Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis, beyond 24 hours, is not recommended.6

Avoiding injury

Gynecologic surgeons should adhere to surgical principles with sharp dissection for adhesions, gentle tissue handling, adequate exposure, and light retraction to prevent bowel injury or minimize their extent. Laparoscopic entry sites should be chosen based on the likelihood of abdominal adhesions. When the patient’s history predicts a high likelihood of intraperitoneal adhesions, the left upper quadrant site should be strongly considered as the entry site. The likelihood of gastrointestinal injury is not influenced by open versus closed laparoscopic entry and surgeons should use the technique with which they have the greatest experience and skill.9 However, in patients who have had prior laparotomies, there is an increased risk of periumbilical adhesions, and consideration should be made for a nonumbilical entry site.10 Methodical sharp dissection and sparing use of thermal energy should be used with adhesiolysis. When injury occurs, prompt recognition, preparation, and methodical management can mitigate the impact.

Dr. Staley is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Int Surg. 2006 Nov-Dec;91(6):336-40.

2. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Jun;192(6):677-83.

3. Doherty, G. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Surgery. Thirteenth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010.

4. Hoffman B. Williams Gynecology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2016.

5. Berek J, Hacker N. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

6. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;14(1):73-156.

7. Br J Surg. 2005 Jun;92(6):673-80.

8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jul;185(1):1-4.

9. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 31;8:CD006583.

10. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):595-600.

Enterotomy can be a serious complication in abdominopelvic surgery, particularly if it is not immediately recognized and treated. Risk of visceral injury increases when complex dissection is required for treatment of cancer, resection of endometriosis, and extensive lysis of adhesions.

In a retrospective review from 1984 to 2003, investigators assessed intestinal injuries at the time of gynecologic operations. Of the 110 cases reported, about 37% occurred during the opening of the peritoneal cavity, 38% during adhesiolysis and pelvic dissection, 9% during laparoscopy, 9% during vaginal surgery, and 8% during dilation and curettage. Of the bowel injuries, more than 75% were minor.1 Mortality from unrecognized bowel injury is significant, and as such, appropriate recognition and management of these injuries is critical.2

Some basic principles are critical when surgeons face a bowel injury:

1. Recognize the extent of the injury, including the size of the breach, the depth (full or partial thickness), and the nature of the injury (thermal or cold).

2. Assess the integrity of the bowel, including adequacy of blood supply, prior bowel damage from radiation, and absence of downstream obstruction.

3. Ensure no other occult injuries exist in other segments.

4. Obtain adequate exposure and mobilization of the bowel beyond the site of injury, including the adjacent bowel. This involves releasing other adhesions so that adequate bowel length is available for a tension-free repair.

Methods of repair

The decision to employ each is influenced by multiple factors. Primary closure is best suited to small lesions (1 cm or less) that are a result of cold or sharp injury. However, thermal injury sustained via electrosurgical devices induces delayed tissue damage beyond the visible edges of the immediate defect, and surgeons should consider a resection of bowel to at least 1 cm beyond the immediately apparent injury site. Additionally, resection and re-anastamosis should also be considered if the damaged segment of bowel has poor blood supply, integrity, or the repair would result in tension along the suture/staple line or luminal narrowing.

Simple small bowel closures

Serosal abrasions need not be repaired; however, small tears of the serosa and muscularis can be managed with a single layer of interrupted 3-0 absorbable or permanent silk suture on a tapered needle. The suture line should be perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bowel at 2-mm to 3-mm intervals in order to prevent narrowing of the lumen. The suture should pass through serosal and muscular layers in an imbricating (Lembert) stitch. For smaller defects of less than 6 mm, a single layer closure is typically adequate.

Small bowel resection

Some larger defects, thermal injuries, and segments with multiple enterotomies may be best repaired with resection and re-anastamosis technique. A segment of resectable bowel is chosen such that the afferent and efferent limbs to be re-anastamosed can be reapproximated in a tension-free fashion. A mesenterotomy is made at the proximal and distal portions of the involved bowel. A gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is then inserted perpendicularly across the bowel. The remaining wedge of connected mesentery can then be efficiently excised with an electrothermal bipolar coagulator device ensuring that maximal mesentery and blood supply are preserved to the remaining limbs of intestine. The proximal and distal segments are then aligned at the antimesenteric sides.

Large bowel repair

Defects in the serosa and small lacerations can be managed with a primary closure, similar to the small intestine. For more extensive injuries that may require resection, diversion, or complicated repair, consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or general or colorectal surgeon may be indicated as colotomy repairs are associated with higher rates of breakdown and fistula. If fecal contamination is present, copious irrigation should be performed and placement of a peritoneal drain to reduce the likelihood of abscess formation should be considered. If appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for colonic surgery has not been given prior to skin incision, it should be administered once the colotomy is identified.

Standard prophylaxis for hysterectomy (such as a first-generation cephalosporin like cefazolin) is not adequate for large bowel surgery, and either metronidazole should be added or a second-generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin should be given. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin with either gentamicin or a fluoroquinolone should be administered.6

Postoperative management

The potential for postoperative morbidity must be understood for appropriate management following bowel surgery. Ileus is common and the clinician should understand how to diagnose and manage it. Additionally, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, fistula formation, and mechanical obstruction are complications that may require surgical intervention and must be vigilantly managed.

The routine use of postoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) does not hasten return of bowel function or prevent leak from sites of gastrointestinal repair. In fact, early feeding has been associated with reduced perioperative complications and earlier return of bowel function has been observed without the use of NGT.7 In general, for small and large intestinal injuries, early feeding is considered acceptable.8

Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis, beyond 24 hours, is not recommended.6

Avoiding injury

Gynecologic surgeons should adhere to surgical principles with sharp dissection for adhesions, gentle tissue handling, adequate exposure, and light retraction to prevent bowel injury or minimize their extent. Laparoscopic entry sites should be chosen based on the likelihood of abdominal adhesions. When the patient’s history predicts a high likelihood of intraperitoneal adhesions, the left upper quadrant site should be strongly considered as the entry site. The likelihood of gastrointestinal injury is not influenced by open versus closed laparoscopic entry and surgeons should use the technique with which they have the greatest experience and skill.9 However, in patients who have had prior laparotomies, there is an increased risk of periumbilical adhesions, and consideration should be made for a nonumbilical entry site.10 Methodical sharp dissection and sparing use of thermal energy should be used with adhesiolysis. When injury occurs, prompt recognition, preparation, and methodical management can mitigate the impact.

Dr. Staley is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Int Surg. 2006 Nov-Dec;91(6):336-40.

2. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Jun;192(6):677-83.

3. Doherty, G. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Surgery. Thirteenth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010.

4. Hoffman B. Williams Gynecology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2016.

5. Berek J, Hacker N. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

6. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;14(1):73-156.

7. Br J Surg. 2005 Jun;92(6):673-80.

8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jul;185(1):1-4.

9. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 31;8:CD006583.

10. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):595-600.

Enterotomy can be a serious complication in abdominopelvic surgery, particularly if it is not immediately recognized and treated. Risk of visceral injury increases when complex dissection is required for treatment of cancer, resection of endometriosis, and extensive lysis of adhesions.

In a retrospective review from 1984 to 2003, investigators assessed intestinal injuries at the time of gynecologic operations. Of the 110 cases reported, about 37% occurred during the opening of the peritoneal cavity, 38% during adhesiolysis and pelvic dissection, 9% during laparoscopy, 9% during vaginal surgery, and 8% during dilation and curettage. Of the bowel injuries, more than 75% were minor.1 Mortality from unrecognized bowel injury is significant, and as such, appropriate recognition and management of these injuries is critical.2

Some basic principles are critical when surgeons face a bowel injury:

1. Recognize the extent of the injury, including the size of the breach, the depth (full or partial thickness), and the nature of the injury (thermal or cold).

2. Assess the integrity of the bowel, including adequacy of blood supply, prior bowel damage from radiation, and absence of downstream obstruction.

3. Ensure no other occult injuries exist in other segments.

4. Obtain adequate exposure and mobilization of the bowel beyond the site of injury, including the adjacent bowel. This involves releasing other adhesions so that adequate bowel length is available for a tension-free repair.

Methods of repair

The decision to employ each is influenced by multiple factors. Primary closure is best suited to small lesions (1 cm or less) that are a result of cold or sharp injury. However, thermal injury sustained via electrosurgical devices induces delayed tissue damage beyond the visible edges of the immediate defect, and surgeons should consider a resection of bowel to at least 1 cm beyond the immediately apparent injury site. Additionally, resection and re-anastamosis should also be considered if the damaged segment of bowel has poor blood supply, integrity, or the repair would result in tension along the suture/staple line or luminal narrowing.

Simple small bowel closures

Serosal abrasions need not be repaired; however, small tears of the serosa and muscularis can be managed with a single layer of interrupted 3-0 absorbable or permanent silk suture on a tapered needle. The suture line should be perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the bowel at 2-mm to 3-mm intervals in order to prevent narrowing of the lumen. The suture should pass through serosal and muscular layers in an imbricating (Lembert) stitch. For smaller defects of less than 6 mm, a single layer closure is typically adequate.

Small bowel resection

Some larger defects, thermal injuries, and segments with multiple enterotomies may be best repaired with resection and re-anastamosis technique. A segment of resectable bowel is chosen such that the afferent and efferent limbs to be re-anastamosed can be reapproximated in a tension-free fashion. A mesenterotomy is made at the proximal and distal portions of the involved bowel. A gastrointestinal anastomotic stapler is then inserted perpendicularly across the bowel. The remaining wedge of connected mesentery can then be efficiently excised with an electrothermal bipolar coagulator device ensuring that maximal mesentery and blood supply are preserved to the remaining limbs of intestine. The proximal and distal segments are then aligned at the antimesenteric sides.

Large bowel repair

Defects in the serosa and small lacerations can be managed with a primary closure, similar to the small intestine. For more extensive injuries that may require resection, diversion, or complicated repair, consultation with a gynecologic oncologist or general or colorectal surgeon may be indicated as colotomy repairs are associated with higher rates of breakdown and fistula. If fecal contamination is present, copious irrigation should be performed and placement of a peritoneal drain to reduce the likelihood of abscess formation should be considered. If appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis for colonic surgery has not been given prior to skin incision, it should be administered once the colotomy is identified.

Standard prophylaxis for hysterectomy (such as a first-generation cephalosporin like cefazolin) is not adequate for large bowel surgery, and either metronidazole should be added or a second-generation cephalosporin such as cefoxitin should be given. For patients with penicillin allergy, clindamycin or vancomycin with either gentamicin or a fluoroquinolone should be administered.6

Postoperative management

The potential for postoperative morbidity must be understood for appropriate management following bowel surgery. Ileus is common and the clinician should understand how to diagnose and manage it. Additionally, intra-abdominal abscess, anastomotic leak, fistula formation, and mechanical obstruction are complications that may require surgical intervention and must be vigilantly managed.

The routine use of postoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) does not hasten return of bowel function or prevent leak from sites of gastrointestinal repair. In fact, early feeding has been associated with reduced perioperative complications and earlier return of bowel function has been observed without the use of NGT.7 In general, for small and large intestinal injuries, early feeding is considered acceptable.8

Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis, beyond 24 hours, is not recommended.6

Avoiding injury

Gynecologic surgeons should adhere to surgical principles with sharp dissection for adhesions, gentle tissue handling, adequate exposure, and light retraction to prevent bowel injury or minimize their extent. Laparoscopic entry sites should be chosen based on the likelihood of abdominal adhesions. When the patient’s history predicts a high likelihood of intraperitoneal adhesions, the left upper quadrant site should be strongly considered as the entry site. The likelihood of gastrointestinal injury is not influenced by open versus closed laparoscopic entry and surgeons should use the technique with which they have the greatest experience and skill.9 However, in patients who have had prior laparotomies, there is an increased risk of periumbilical adhesions, and consideration should be made for a nonumbilical entry site.10 Methodical sharp dissection and sparing use of thermal energy should be used with adhesiolysis. When injury occurs, prompt recognition, preparation, and methodical management can mitigate the impact.

Dr. Staley is a gynecologic oncology fellow at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Int Surg. 2006 Nov-Dec;91(6):336-40.

2. J Am Coll Surg. 2001 Jun;192(6):677-83.

3. Doherty, G. Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Surgery. Thirteenth Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2010.

4. Hoffman B. Williams Gynecology. Third Edition. New York: McGraw Hill, 2016.

5. Berek J, Hacker N. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic Oncology. Sixth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2015.

6. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;14(1):73-156.

7. Br J Surg. 2005 Jun;92(6):673-80.

8. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 Jul;185(1):1-4.

9. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 31;8:CD006583.

10. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997 May;104(5):595-600.

A multidisciplinary approach to diaphragmatic endometriosis

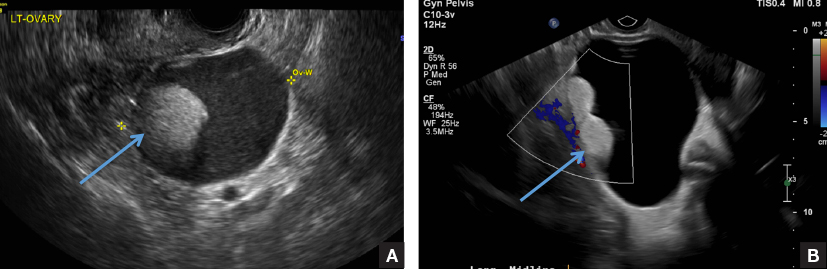

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

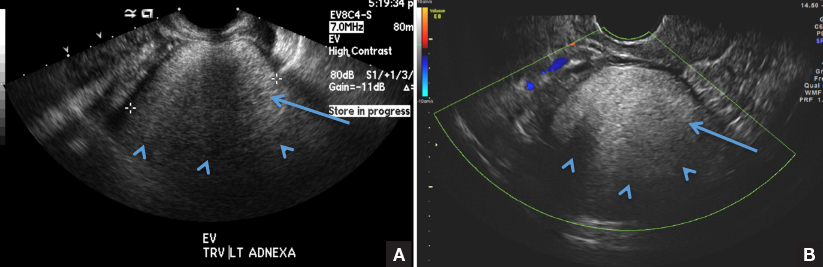

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.

Thoracoscopic treatment varies, involving ablation or excision of smaller diaphragmatic lesions, pulmonary wedge resection of deep parenchymal nodules (using a stapling device), diaphragm resection of deep diaphragmatic lesions using a stapling device, or by excision and manual suturing.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment begins by introducing a 10-mm port at the umbilicus and placing three additional ports in the upper quadrant (right or left, depending on implant location). The arrangement (similar to that of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy or splenectomy) allows for examination of the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm and almost the entire left hemidiaphragm in addition to routine abdominopelvic exploration.

For better laparoscopic visualization, the patient is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, and the liver is gently pushed caudally to view the adjacent diaphragm. The upper abdominal walls and the liver also may be evaluated while in this position.

Bluish pigmented lesions are the most commonly reported form of diaphragmatic endometriosis, followed by lesions with a reddish-purple appearance. However, lesions can present with various colors and morphologic appearances, such as fibrotic white lesions or adhesions to the liver.

In our practice, we recommend using the CO2 laser (set at 20-25 watts) with hydrodissection for superficial lesions. The CO2 laser is much more precise and has a smaller depth of penetration and less thermal spread, compared with electrocautery. The CO2 laser beam also reaches otherwise hard-to-access areas behind the liver and has proven to be safe for vaporizing and/or excising many types of diaphragmatic lesions. We have successfully treated diaphragmatic endometriosis in the vicinity of the phrenic nerve and directly in line with the left ventricle.

Watch a video from Dr. Ceana Nezhat demonstrating a step wise vaporization and excision of diaphragmatic endometriosis utilizing different techniques.

(Courtesy Dr. Ceana Nezhat)

Plasma jet energy and ultrasonic energy are good alternatives when a CO2 laser is not available and are preferable to the use of cold scissors because of subsequent bleeding, which requires bipolar hemostasis.

Monopolar electrocautery is not as good a choice for treating diaphragmatic endometriosis because of higher depth of penetration, which may cause tissue necrosis and subsequent delayed diaphragmatic fenestrations. It also may cause unpredictable diaphragmatic muscular contractions and electrical conduction transmitted to the heart, inducing arrhythmia.

For patients treated via combined VALS and VATS procedures, endometriotic lesions involving the entire thickness of the diaphragm should be completely resected, and the defect can be repaired with either sutures or staples.

In all cases, special anesthesia considerations must be made given the inability to completely ventilate the lung. In our practice, we use a double-lumen endotracheal tube for single lung ventilation, if needed. A bronchial blocker is used to isolate the lung when the double-lumen endotracheal tube cannot be inserted.

It is important to note that we do not recommend VATS with VALS in all suspicious cases. We reserve VATS only for patients with catamenial pneumothorax, catamenial hemothorax, hemoptysis, and pulmonary nodules, defined as Thoracic Endometriosis Syndrome. We usually start with medical management first, then proceed to VALS, and finally, VATS, with the intention to treat if the patient fails nonsurgical treatments. It is better to avoid VATS, if possible, because it is associated with longer recovery and more pain; it should be done if all else fails.

If the patient has completed childbearing or passed reproductive age, bilateral salpingectomy, or hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, may be considered as the first step prior to more aggressive excisional procedures. This is especially true for widespread lesions, as branches of the phrenic nerve are difficult to see and injury could result in paralysis of the diaphragm. It’s important to appreciate that if estrogen stimulation to the diaphragmatic lesions is to cease for the long term, hormonal suppression or surgical treatment including bilateral oophorectomy should be utilized.

My colleagues and I have reported on our experience with a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of diaphragmatic endometriosis in 25 patients. All had both pelvic and thoracic symptoms, and the majority had endometrial implants on both the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm.

There were two postoperative complications: a diaphragmatic hernia and a vaginal cuff hematoma. Over a follow-up period of 3-18 months, all 25 patients had significant improvement or resolution of their chest complaints, and most remained asymptomatic for more than 6 months (JSLS. 2014 Jul-Sep;18[3]. pii: e2014.00312. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00312).

Dr. Ceana Nezhat is the fellowship director of Nezhat Medical Center, the medical director of training and education at Northside Hospital, and an adjunct clinical professor of gynecology and obstetrics at Emory University, all in Atlanta. He is president of SRS (Society of Reproductive Surgeons) and past president of AAGL (American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists). Dr. Nezhat is a consultant for Novuson Surgical, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Lumenis, and AbbVie; a medical advisor for Plasma Surgical, and a member of the scientific advisory board for SurgiQuest.

Suggested readings

1. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Nezhat’s Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy with Hysteroscopy. Fourth Edition. Cambridge University Press. 2013.

2. Am J Med. 1996 Feb;100(2):164-70.

3. Fertil Steril. 1998 Jun;69(6):1048-55.

4. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Sep;42(3):699-711.

5. JSLS. 2012 Jan-Mar; 16(1):140-2.

Endometriosis affects approximately 11% of women; the disease can be categorized as pelvic endometriosis and extrapelvic endometriosis, based on anatomic presentation. It is estimated that about 12% of extrapelvic disease involves the diaphragm or thoracic cavity.

While diaphragmatic endometriosis often is asymptomatic, patients who are symptomatic can experience progressive and incapacitating pain. because of a traditional focus on the lower pelvic region. Some cases are misdiagnosed as other conditions involving the gastrointestinal tract or of cardiothoracic origin, because of the propensity of diaphragmatic disease to occur posteriorly and hide behind the liver. The variable appearance of endometriotic lesions and the lack of reliable diagnostic or imaging tests also can contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Symptoms usually occur cyclically with the onset of menses, but sometimes are unrelated to menses. Most diaphragmatic lesions occur on the abdominal side and right hemidiaphragm, which may offer evidence for the theory that retrograde menstruation drives the development of endometriosis because of the clockwise flow of peritoneal fluid. However, lesions have been found on all parts of the diaphragm, including the left side only, the thoracic and visceral sides of the diaphragm, and the phrenic nerve. There is no correlation between the size/number of lesions and either pneumothorax or hemothorax, nor pain.

The best diagnostic method is thorough surveillance intraoperatively. In our practice, we routinely inspect the diaphragm for endometriosis at the time of video laparoscopy.

In women who have symptoms, it is important to ensure the best exposure of the diaphragm by properly considering the patient’s positioning and port placement, and by using an atraumatic liver retractor or grasping forceps to gently push the liver down and away from the visual/operative field. Posterior diaphragm viewing can also be enhanced by utilizing a 30-degree laparoscope angled toward the back. At times, it is helpful to cut the falciform ligament near the liver to expose the right side of the diaphragm completely while the patient is in steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

Most lesions in symptomatic patients can be successfully removed with hydrodissection and vaporization or excision. For asymptomatic patients with an incidental finding of diaphragmatic endometriosis, the suggestion is not to treat lesions in order to avoid the potential risk of injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, lungs, or heart – especially when an adequate multidisciplinary team is not available.

Pathophysiology

In addition to retrograde menstruation, there are two other common theories regarding the pathophysiology of thoracic endometriosis. First, high prostaglandin F2-alpha at ovulation may result in vasospasm and ischemia of the lungs (resulting, in turn, in alveolar rupture and subsequent pneumothorax). Second, the loss of a mucus plug during menses may result in communication between the environment and peritoneal cavity.

What is clear is that patients who have symptoms consistent with pelvic endometriosis and chest complaints should be evaluated for both diaphragmatic and pelvic endometriosis. It’s also increasing clear that a multidisciplinary approach utilizing combined laparoscopy and thoracoscopy is a safe and effective method for addressing pelvic, diaphragmatic, and other thoracic endometriosis when other treatments have failed.

A multidisciplinary approach

Since the introduction of video laparoscopy and ease of evaluation of the upper abdomen, more extrapelvic endometriosis – including disease in the upper abdomen and diaphragm – is being diagnosed. The thoracic and visceral diaphragm are the most commonly described sites of thoracic endometriosis, and disease is often right sided, with parenchymal involvement less commonly reported.

Abdominopelvic and visceral diaphragmatic endometriosis are treated endoscopically with hydrodissection followed by excision or ablation. Superficial lesions away from the central diaphragm can be coagulated using bipolar current.