User login

2017 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines overactive bladder (OAB) as a syndrome of "urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection [UTI] or obvious pathology."1 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reported OAB prevalence to be 15% in US women, with 11% reporting UUI.2 OAB represents a significant health care burden that impacts nearly every aspect of life, including physical, emotional, and psychological domains.3,4 The economic impact is notable; the projected cost is estimated to reach $82.6 billion annually by 2020.5

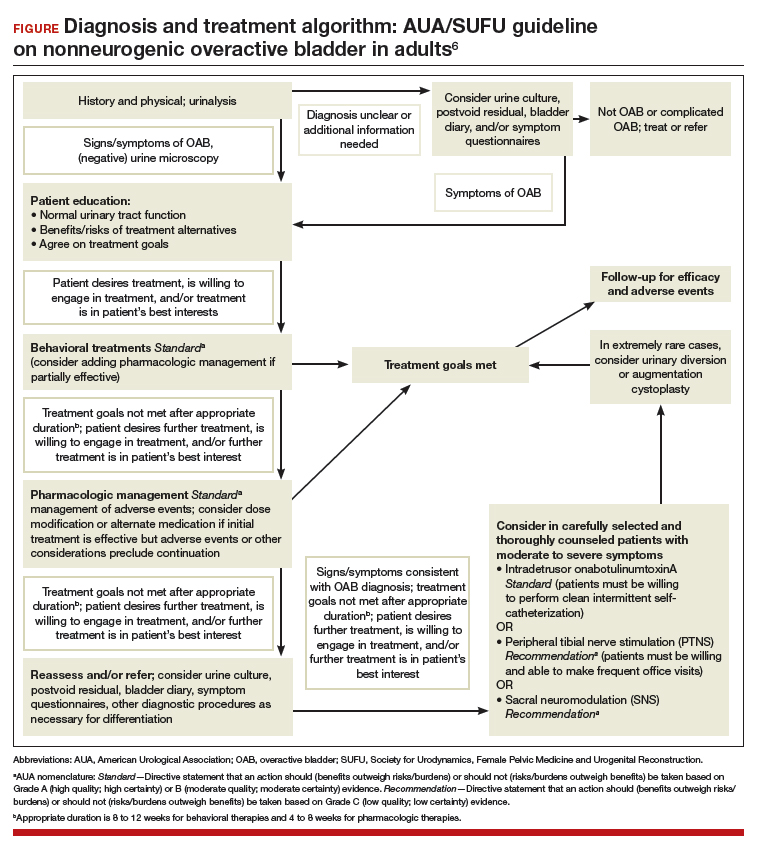

The American Urological Association (AUA) and the Society for Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) have endorsed an algorithm for use in the evaluation of idiopathic OAB (FIGURE).6 If the patient's symptoms are certain, minimal evaluation is needed and it is reasonable to proceed with first-line therapy, which includes fluid management (decreasing caffeine intake and limiting evening fluid intake), bladder retraining drills such as timed voiding, and improving pelvic floor muscles with the use of biofeedback and functional electrical stimulation.6,7 Pelvic floor muscle training can be facilitated with a referral to a physical therapist trained in pelvic floor muscle education.

If treatment goals are not met with first-line strategies, second-line therapy may be initiated with anticholinergic or β3-adrenergic receptor agonist medications. If symptoms persist after 4 to 8 weeks of pharmacologic therapy, clinicians are encouraged to reassess or refer the patient to a specialist. Further evaluation may include a bladder diary in which the patient documents voided volumes, voiding frequency, and number of incontinent episodes; symptom-specific questionnaires; and/or urodynamic testing.

Related article:

The latest treatments for urinary and fecal incontinence: Which hold water?

Based on that evaluation, the patient may be a candidate for third-line therapy with either intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA, posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), or sacral neuromodulation.

There is a paucity of information comparing third-line therapies. In this Update, we focus on 4 randomized clinical trials that compare third-line treatment options for idiopathic OAB.

Read about how anticholinergic medication and onabotulinumtoxinA compare for treating UUI.

Anticholinergic therapy and onabotulinumtoxinA produce equivalent reductions in the frequency of daily UUI episodes

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Anticholinergic therapy vs onabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1803-1813.

In a double-blind, double-placebo-controlled randomized trial, Visco and colleagues compared anticholinergic medication with onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U for the treatment of women with UUI.

Details of the study

Two hundred forty-one women with moderate to severe UUI received either 6 months of oral anticholinergic therapy (solifenacin 5 mg daily with the option of dose escalation to 10 mg daily or change to trospium XR 60 mg daily based on the Patient Global Symptom Control score) plus a single intradetrusor injection of saline, or a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U plus a 6-month oral placebo regimen.

Inclusion criteria were 5 or more UUI episodes on a 3-day diary, insufficient resolution of symptoms after 2 medications, or being drug naive. Exclusions included a postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume greater than 150 mL or previous therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA.

Participants were scheduled for follow up every 2 to 6 months post randomization, at which time all study medications were discontinued. The primary outcome was reduction from baseline in the mean number of UUI episodes per day over the 6-month period, as recorded in the monthly 3-day bladder diaries. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants with complete resolution of UUI, the proportion of participants with 75% or more reduction in UUI episodes, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OABq-SF) scores, other symptom-specific questionnaire scores, and adverse events.

Related article:

Which treatments for pelvic floor disorders are backed by evidence?

Both treatments significantly reduced UUI episodes

At baseline, participants reported a mean (SD) of 5.0 (2.7) UUI episodes per day, and 41% of participants were drug naive. Both treatment groups experienced significant reductions compared with baseline in mean UUI episodes, and the reductions were similar between the 2 groups (reduction of 3.4 episodes per day in the anticholinergic group, reduction of 3.3 episodes in the onabotulinumtoxinA group; P = .81). Complete resolution of UUI was more common in the onabotulinumtoxinA group (27%) as compared with the anticholinergic group (13%) (P = .003). There were no differences in improvement in OABq-SF scores (37.05 in the anticholinergic group vs 37.13 in the onabotulinumtoxinA group; P = .98) or other quality-of-life measures.

Adverse events. The anticholinergic group experienced a higher rate of dry mouth compared with the onabotulinumtoxinA group (46% vs 31%; P = .02) but had lower rates of intermittent catheterization use at 2 months (0% vs 5%, P = .01) and UTIs (13% vs 33%, P<.001).

Strengths and limitations. This was a well-designed, multicenter, randomized double-blind, double placebo-controlled trial. The study design allowed for dose escalation and change to another medication for inadequate symptom control and included drug-naive participants, which increases the generalizability of the results. However, current guidelines recommend reserving onabotulinumtoxinA therapy for third-line therapy, thus deterring this treatment's use in the drug-naive population. Additionally, the lack of a pure placebo arm makes it difficult to interpret the extent to which a placebo effect contributed to observed improvements in clinical symptoms.

Through 6 months, both a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and anticholinergic therapy reduce UUI episodes and improve quality-of-life measures in women who have failed medications or are drug naive. Use of onabotulinumtoxinA, however, more likely will lead to complete resolution of UUI, although with an increased risk of transient urinary retention and UTI. Even given the study findings supporting the use of onabotulinumtoxinA over anticholinergic therapy for complete resolution of UUI, it is most appropriate to align with current practice, which includes a trial of pharmacotherapy before proceeding with third-line onabotulinumtoxinA.

Read: onabotulinumtoxinA vs PTNS for OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA has greater 9-month durability for OAB symptoms compared with12 weeks of PTNS

Sherif H, Khalil M, Omar R. Management of refractory idiopathic overactive bladder: intradetrusor injection of botulinum toxin type A versus posterior tibial nerve stimulation. Can J Urol. 2017;24(3):8838-8846.

In this randomized clinical trial, Sherif and colleagues compared the safety and efficacy of a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U with that of PTNS for OAB.

Details of the study

Sixty adult men and women with OAB who did not respond to medical therapy were randomly assigned to treatment with either onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U or PTNS. Criteria for exclusion were current UTI, PVR urine volume of more than 150 mL, previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy, previous incontinence surgery or bladder malignancy, or presence of mixed urinary incontinence.

At baseline, participants completed a 3-day bladder diary, an OAB symptom score (OABSS) questionnaire, and urodynamic testing. The OABSS questionnaire included 7 questions (scoring range, 0-28), with higher scores indicating worse symptoms, and included subscales for urgency and quality-of-life measures. Total OABSS, urgency score, quality-of-life score, bladder diary records, and urodynamic testing parameters were assessed at 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks, along with adverse events.

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections were performed under spinal anesthesia. If PVR urine volume was greater than 200 mL at any follow-up visit, participants were instructed to begin clean intermittent self-catheterization. PTNS was administered as weekly 30-minute sessions for 12 consecutive weeks.

Participants' baseline demographics and symptoms were similar. Average age was 45 years. Averages (SD) for duration of anticholinergic use was 13 (0.8) weeks, UUI episode score was 4.5 (1) on 3-day bladder diary, and OABSS was 22 (2.7). Nine-month data were available for 29 participants in the onabotulinumtoxinA group and for 8 in the PTNS group.

Related article:

Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence

OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment benefits sustained for 9 months

Through 6 months, compared with baseline assessments, both treatment groups had significant improvements in clinical symptoms and OABSS total score, as well as urgency and quality-of-life subscales. At 3 months, urodynamic study parameters were similarly improved from baseline in both groups.

At 9 months, however, only the onabotulinumtoxinA group, compared with the PTNS group, maintained the significant improvement from baseline in 3-day bladder diary voiding episodes (average [SD], 10.7 [1.01] vs 11.6 [1.09]; P = .009), 3-day bladder diary nocturia episodes (average [SD], 3.8 [1.09] vs 4.4 [0.8]; P = .02), and average [SD] UUI episodes over 3 days (3.5 [1.2] vs 4.2 [1.04]; P = .02). Similarly, onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants, compared with those treated with PTNS, maintained improvements at 9 months in average (SD): OABSS total score (19.2 [2.4] vs 20.4 [1.7]; P = .03), urgency scores (10.9 [1.3] vs 11.8 [1.4]; P = .009), urine volume at first desire (177.8 [9.2] vs 171.8 [7.7]), maximum cystometric capacity (304 [17.6] vs 290 [13.1]), and Qmax (mL/sec) (20.7 [1.6] vs 22.2 [1.2]).

Adverse events. Average PVR urine volumes were higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group compared with the PTNS group (36.8 [2.7] vs 32.4 [3.03]; P = .0001) at all time points, and self-catheterization was required in 6.6% of onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants. Urinary tract infection occurred in 6.6% of participants in the onabotulinumtoxinA group and in none of the PTNS group. In the PTNS group, few experienced pain and minor bleeding at the needle site.

Strengths and limitations. This randomized, open-label trial comparing treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and PTNS included both men and women with idiopathic OAB symptoms. The participants were assessed at regular intervals with various measures, and follow-up adherence was good. The sample size was small, so the study may not have been powered to see differences prior to 9 months.

Although at 9 months only the onabotulinumtoxinA group maintained significant improvement over baseline levels, the improvement was diminished, and therefore the clinical meaningfulness is uncertain. Further, participants in the PTNS group did not undergo monthly maintenance therapy after 3 months, which is recommended for those with a 12-week therapeutic response; this may have affected 9-month outcomes in this group. Since the one-time onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U injection was performed under spinal anesthesia, cost comparisons should be considered, since future onabotulinumtoxinA injections would be necessary.

A one-time onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U injection and 12 weeks of PTNS therapy are reasonable short-term options for symptomatic OAB relief after unsuccessful therapy with medications. OnabotulinumtoxinA injection may provide more durable OAB symptom control at 9 months but with a risk of UTI and need for self-catheterization.

Read about using different doses of onabotulinumtoxinA for OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA 200-U injection provides longer OAB symptom improvement than 100-U injection

Abdelwahab O, Sherif H, Soliman T, Elbarky I, Eshazly A. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A 100 units versus 200 units for treatment of refractory idiopathic overactive bladder. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(6):1132-1140.

Abdelwahab and colleagues conducted a single-center, randomized clinical trial to investigate the safety and efficacy of a single injection of intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA in 2 different doses (100 U and 200 U) for treatment of OAB.

Details of the study

Eighty adults (63 women, 17 men) who did not benefit from anticholinergic medication during the previous 3 months were randomly assigned to receive either a 100-U (n = 40) or a 200-U (n = 40) injection of onabotulinumtoxinA. Exclusion criteria were PVR urine volume greater than 150 mL and previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

Initial assessments -- completed at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months -- included the health-related quality-of-life (HR-QOL) questionnaire (maximum score, 100; higher score indicates better quality of life), an abbreviated OABSS questionnaire (4 questions; score range, 0-15; higher score indicates more severe symptoms), and urodynamic evaluation. Outcomes included OABSS, HR-QOL score, and urodynamic parameters at the various time points.

Related article:

Is there a link between impaired mobility and urinary incontinence in elderly, community-dwelling women?

Higher dose, greater symptom improvement and higher adverse event rate

At baseline, participants (average age, 31 years) had an average (SD) OABSS of 1.7 (1.6). OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment with both a 100-U and a 200-U dose resulted in significant improvements (compared with baseline levels) in frequency, nocturia, UUI episodes, OABSS, and urodynamic parameters throughout the 9 months. At 9 months, however, the group treated with the 200-U dose had greater improvements, compared with the group who received a 100-U dose, in urinary frequency symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.32 [0.47] vs 1.1 [0.51]; P<.05), nocturia symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.13 [0.34] vs 0.36 [0.49]; P<.05), UUI symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.68 [0.16] vs 1.26 [1.1]; P<.05), and mean (SD) total OABSS (2.6 [2.31] vs 5.3 [2.11]; P<.05). Similarly, at 9 months the 200-U dose resulted in greater improvements in volume at first desire (mean [SD], 291.8 [42.8] vs 246.8 [53.8] mL; P<.05), volume at strong desire (mean [SD], 392.1 [37.3] vs 313.1 [67.4] mL; P<.05), detrusor pressure (mean [SD], 10.4 [4.0] vs 19.2 [7.8] cm H2O; P<.05), and maximum cystometric capacity (mean [SD], 430.5 [34.2] vs 350 [69.1] mL; P<.05) compared with the 100-U dose.

Adverse events. No participant had a PVR urine volume greater than 100 mL at any follow-up visit. Postoperative hematuria occurred in 23% of the group treated with onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U versus in 15% of those treated with a 100-U dose. Similarly, UTIs occurred in 17.5% of the 200-U dose group and in 7.5% of the 100-U dose group. Dysuria was reported in 37.5% and 15% of the 200-U and 100-U dose groups, respectively.

Strengths and limitations. This randomized, open-label trial comparing a single injection of 100 U versus 200 U of onabotulinumtoxinA included mostly women. OAB symptoms and urodynamic parameters improved after treatment with both dose levels, but a longer duration of improvement was seen with the 200-U dose. The cohort had a low baseline OAB severity, based on the OABSS questionnaire, and a young average age of participants, which limits the generalizability of the study results to a population with refractory OAB. The 0% rate of clean intermittent self-catheterization postinjection might be based on the study's criteria for requiring clean intermittent catheterization. In addition, the initial postinjection visit occurred at 1 month, possibly missing participants who had symptoms of retention soon after injection.

Two dose levels (100 U and 200 U) of a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA are associated with comparable OAB symptom and urodyanamic improvements. The benefits of a longer duration of effect with the 200-U dose must be weighed against the possible higher risks of transient hematuria, dysuria, and UTI.

Read: onabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation therapy for UUI.

Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA may control UUI symptoms better than sacral neuromodulation therapy

Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary incontinence in women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1366-1374.

In this multicenter open-label randomized trial, Amundsen and colleagues compared the efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U with that of sacral neuromodulation.

Details of the study

Three hundred sixty-four women with UUI had data available for primary analysis at 6 months. Women were considered eligible for the study if they had 6 or more UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary, persistent symptoms despite anticholinergic therapy, a PVR urine volume of less than 150 mL, and had never previously received either study treatment.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics of the participants. The average (SD) age of the study population was 63 (11.6) years, with an average (SD) daily number of UUI episodes of 5.3 (2.8). The average (SD) body mass index was 32 (8) kg/m2.

Participants were randomly assigned to undergo either sacral neuromodulation (n = 174) or intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U (n = 190). The primary outcome was change from baseline in mean number of daily UUI episodes averaged over 6 months as recorded on a monthly 3-day bladder diary. Secondary outcomes included complete resolution of urgency incontinence, 75% or more reduction in UUI episodes, the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (SF) score (range, 0-100; higher score indicates higher symptom severity), the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire (range, 0-100; higher score indicates better satisfaction), other quality-of-life measures, and adverse events.

Related article:

2015 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Bladder pain syndrome

Greater symptom bother improvement, treatment satisfaction with onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U

Participants treated with onabotulinumtoxinA had a greater mean reduction of 3.9 UUI episodes per day than the sacral neuromodulation group's reduction of 3.3 UUI episodes per day (mean difference, 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13-1.14; P = .01). In addition, complete UUI resolution was higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group as compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (20% vs 4%; P<.001). The onabotulinumtoxinA group also had higher rates of 75% or more reduction of UUI episodes compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (46% vs 26%; P<.001). Over 6 months, both groups had improvements in all quality-of-life measures, but the onabotulinumtoxinA group had greater improvement in symptom bother compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (-46.7 vs -38.6; mean difference, 8.1; 95% CI, 3.0-13.3; P = .002). Furthermore, the onabotulinumtoxinA group had greater treatment satisfaction compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (mean difference, 7.8; 95% CI, 1.6-14.1; P = .01).

Adverse events. Six women (3%) underwent sacral neuromodulation device revision or removal. Approximately 8% of onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants required intermittent self-catheterization at 1 month, 4% at 3 months, and 2% at 6 months. The risk of UTI was higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (35% vs 11%; risk difference, 23%; 95% CI, -33% to -13%; P<.001).

Strengths and limitations. This is a well-designed randomized clinical trial comparing clinical outcomes and adverse events after treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA 200-U versus sacral neuromodulation. The interventions were standardized across investigators at multiple sites, and the study design required close follow-up to assess efficacy and adverse events. The study used a 200-U dose based on reported durability of effect at that time and findings of equivalency between onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and anticholinergic therapy. The US Food and Drug Administration's recommendation to use a 100-U dose in all patients with idiopathic OAB might dissuade clinicians from considering the higher dose of onabotulinumtoxinA. The study was limited by the lack of a placebo group.

Both onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U and sacral neuromodulation provide significant improvement in UUI episodes and quality of life over 6 months. However, while treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA has a likelihood of complete UUI resolution, greater improvements in symptom bother and treatment satisfaction, these benefits must be weighed against the risks of transient catheterization and UTI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al; International Urogynecological Association; International Continence Society. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):4-20.

- Hartmann KE, McPheeters ML, Biller DH, et al. Treatment of overactive bladder in women. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;187:1-120.

- Reynolds,WS, Fowke J, Dmochowski, R. The burden of overactive bladder on US public health. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2016;11(1):8-13.

- Willis-Gray MG, Dieter AA, Geller EJ. Evaluation and management of overactive bladder: strategies for optimizing care. Res Rep Urol. 2016;8:113-122.

- Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology. 2010;75(3):526-532.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP; American Urological Association; Society of Urodyndamics, Female Pelvic Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015; 193(5):1572-1580.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al; American Urological Association; Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 suppl):2455-2463.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines overactive bladder (OAB) as a syndrome of "urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection [UTI] or obvious pathology."1 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reported OAB prevalence to be 15% in US women, with 11% reporting UUI.2 OAB represents a significant health care burden that impacts nearly every aspect of life, including physical, emotional, and psychological domains.3,4 The economic impact is notable; the projected cost is estimated to reach $82.6 billion annually by 2020.5

The American Urological Association (AUA) and the Society for Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) have endorsed an algorithm for use in the evaluation of idiopathic OAB (FIGURE).6 If the patient's symptoms are certain, minimal evaluation is needed and it is reasonable to proceed with first-line therapy, which includes fluid management (decreasing caffeine intake and limiting evening fluid intake), bladder retraining drills such as timed voiding, and improving pelvic floor muscles with the use of biofeedback and functional electrical stimulation.6,7 Pelvic floor muscle training can be facilitated with a referral to a physical therapist trained in pelvic floor muscle education.

If treatment goals are not met with first-line strategies, second-line therapy may be initiated with anticholinergic or β3-adrenergic receptor agonist medications. If symptoms persist after 4 to 8 weeks of pharmacologic therapy, clinicians are encouraged to reassess or refer the patient to a specialist. Further evaluation may include a bladder diary in which the patient documents voided volumes, voiding frequency, and number of incontinent episodes; symptom-specific questionnaires; and/or urodynamic testing.

Related article:

The latest treatments for urinary and fecal incontinence: Which hold water?

Based on that evaluation, the patient may be a candidate for third-line therapy with either intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA, posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), or sacral neuromodulation.

There is a paucity of information comparing third-line therapies. In this Update, we focus on 4 randomized clinical trials that compare third-line treatment options for idiopathic OAB.

Read about how anticholinergic medication and onabotulinumtoxinA compare for treating UUI.

Anticholinergic therapy and onabotulinumtoxinA produce equivalent reductions in the frequency of daily UUI episodes

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Anticholinergic therapy vs onabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1803-1813.

In a double-blind, double-placebo-controlled randomized trial, Visco and colleagues compared anticholinergic medication with onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U for the treatment of women with UUI.

Details of the study

Two hundred forty-one women with moderate to severe UUI received either 6 months of oral anticholinergic therapy (solifenacin 5 mg daily with the option of dose escalation to 10 mg daily or change to trospium XR 60 mg daily based on the Patient Global Symptom Control score) plus a single intradetrusor injection of saline, or a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U plus a 6-month oral placebo regimen.

Inclusion criteria were 5 or more UUI episodes on a 3-day diary, insufficient resolution of symptoms after 2 medications, or being drug naive. Exclusions included a postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume greater than 150 mL or previous therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA.

Participants were scheduled for follow up every 2 to 6 months post randomization, at which time all study medications were discontinued. The primary outcome was reduction from baseline in the mean number of UUI episodes per day over the 6-month period, as recorded in the monthly 3-day bladder diaries. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants with complete resolution of UUI, the proportion of participants with 75% or more reduction in UUI episodes, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OABq-SF) scores, other symptom-specific questionnaire scores, and adverse events.

Related article:

Which treatments for pelvic floor disorders are backed by evidence?

Both treatments significantly reduced UUI episodes

At baseline, participants reported a mean (SD) of 5.0 (2.7) UUI episodes per day, and 41% of participants were drug naive. Both treatment groups experienced significant reductions compared with baseline in mean UUI episodes, and the reductions were similar between the 2 groups (reduction of 3.4 episodes per day in the anticholinergic group, reduction of 3.3 episodes in the onabotulinumtoxinA group; P = .81). Complete resolution of UUI was more common in the onabotulinumtoxinA group (27%) as compared with the anticholinergic group (13%) (P = .003). There were no differences in improvement in OABq-SF scores (37.05 in the anticholinergic group vs 37.13 in the onabotulinumtoxinA group; P = .98) or other quality-of-life measures.

Adverse events. The anticholinergic group experienced a higher rate of dry mouth compared with the onabotulinumtoxinA group (46% vs 31%; P = .02) but had lower rates of intermittent catheterization use at 2 months (0% vs 5%, P = .01) and UTIs (13% vs 33%, P<.001).

Strengths and limitations. This was a well-designed, multicenter, randomized double-blind, double placebo-controlled trial. The study design allowed for dose escalation and change to another medication for inadequate symptom control and included drug-naive participants, which increases the generalizability of the results. However, current guidelines recommend reserving onabotulinumtoxinA therapy for third-line therapy, thus deterring this treatment's use in the drug-naive population. Additionally, the lack of a pure placebo arm makes it difficult to interpret the extent to which a placebo effect contributed to observed improvements in clinical symptoms.

Through 6 months, both a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and anticholinergic therapy reduce UUI episodes and improve quality-of-life measures in women who have failed medications or are drug naive. Use of onabotulinumtoxinA, however, more likely will lead to complete resolution of UUI, although with an increased risk of transient urinary retention and UTI. Even given the study findings supporting the use of onabotulinumtoxinA over anticholinergic therapy for complete resolution of UUI, it is most appropriate to align with current practice, which includes a trial of pharmacotherapy before proceeding with third-line onabotulinumtoxinA.

Read: onabotulinumtoxinA vs PTNS for OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA has greater 9-month durability for OAB symptoms compared with12 weeks of PTNS

Sherif H, Khalil M, Omar R. Management of refractory idiopathic overactive bladder: intradetrusor injection of botulinum toxin type A versus posterior tibial nerve stimulation. Can J Urol. 2017;24(3):8838-8846.

In this randomized clinical trial, Sherif and colleagues compared the safety and efficacy of a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U with that of PTNS for OAB.

Details of the study

Sixty adult men and women with OAB who did not respond to medical therapy were randomly assigned to treatment with either onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U or PTNS. Criteria for exclusion were current UTI, PVR urine volume of more than 150 mL, previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy, previous incontinence surgery or bladder malignancy, or presence of mixed urinary incontinence.

At baseline, participants completed a 3-day bladder diary, an OAB symptom score (OABSS) questionnaire, and urodynamic testing. The OABSS questionnaire included 7 questions (scoring range, 0-28), with higher scores indicating worse symptoms, and included subscales for urgency and quality-of-life measures. Total OABSS, urgency score, quality-of-life score, bladder diary records, and urodynamic testing parameters were assessed at 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks, along with adverse events.

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections were performed under spinal anesthesia. If PVR urine volume was greater than 200 mL at any follow-up visit, participants were instructed to begin clean intermittent self-catheterization. PTNS was administered as weekly 30-minute sessions for 12 consecutive weeks.

Participants' baseline demographics and symptoms were similar. Average age was 45 years. Averages (SD) for duration of anticholinergic use was 13 (0.8) weeks, UUI episode score was 4.5 (1) on 3-day bladder diary, and OABSS was 22 (2.7). Nine-month data were available for 29 participants in the onabotulinumtoxinA group and for 8 in the PTNS group.

Related article:

Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence

OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment benefits sustained for 9 months

Through 6 months, compared with baseline assessments, both treatment groups had significant improvements in clinical symptoms and OABSS total score, as well as urgency and quality-of-life subscales. At 3 months, urodynamic study parameters were similarly improved from baseline in both groups.

At 9 months, however, only the onabotulinumtoxinA group, compared with the PTNS group, maintained the significant improvement from baseline in 3-day bladder diary voiding episodes (average [SD], 10.7 [1.01] vs 11.6 [1.09]; P = .009), 3-day bladder diary nocturia episodes (average [SD], 3.8 [1.09] vs 4.4 [0.8]; P = .02), and average [SD] UUI episodes over 3 days (3.5 [1.2] vs 4.2 [1.04]; P = .02). Similarly, onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants, compared with those treated with PTNS, maintained improvements at 9 months in average (SD): OABSS total score (19.2 [2.4] vs 20.4 [1.7]; P = .03), urgency scores (10.9 [1.3] vs 11.8 [1.4]; P = .009), urine volume at first desire (177.8 [9.2] vs 171.8 [7.7]), maximum cystometric capacity (304 [17.6] vs 290 [13.1]), and Qmax (mL/sec) (20.7 [1.6] vs 22.2 [1.2]).

Adverse events. Average PVR urine volumes were higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group compared with the PTNS group (36.8 [2.7] vs 32.4 [3.03]; P = .0001) at all time points, and self-catheterization was required in 6.6% of onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants. Urinary tract infection occurred in 6.6% of participants in the onabotulinumtoxinA group and in none of the PTNS group. In the PTNS group, few experienced pain and minor bleeding at the needle site.

Strengths and limitations. This randomized, open-label trial comparing treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and PTNS included both men and women with idiopathic OAB symptoms. The participants were assessed at regular intervals with various measures, and follow-up adherence was good. The sample size was small, so the study may not have been powered to see differences prior to 9 months.

Although at 9 months only the onabotulinumtoxinA group maintained significant improvement over baseline levels, the improvement was diminished, and therefore the clinical meaningfulness is uncertain. Further, participants in the PTNS group did not undergo monthly maintenance therapy after 3 months, which is recommended for those with a 12-week therapeutic response; this may have affected 9-month outcomes in this group. Since the one-time onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U injection was performed under spinal anesthesia, cost comparisons should be considered, since future onabotulinumtoxinA injections would be necessary.

A one-time onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U injection and 12 weeks of PTNS therapy are reasonable short-term options for symptomatic OAB relief after unsuccessful therapy with medications. OnabotulinumtoxinA injection may provide more durable OAB symptom control at 9 months but with a risk of UTI and need for self-catheterization.

Read about using different doses of onabotulinumtoxinA for OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA 200-U injection provides longer OAB symptom improvement than 100-U injection

Abdelwahab O, Sherif H, Soliman T, Elbarky I, Eshazly A. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A 100 units versus 200 units for treatment of refractory idiopathic overactive bladder. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(6):1132-1140.

Abdelwahab and colleagues conducted a single-center, randomized clinical trial to investigate the safety and efficacy of a single injection of intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA in 2 different doses (100 U and 200 U) for treatment of OAB.

Details of the study

Eighty adults (63 women, 17 men) who did not benefit from anticholinergic medication during the previous 3 months were randomly assigned to receive either a 100-U (n = 40) or a 200-U (n = 40) injection of onabotulinumtoxinA. Exclusion criteria were PVR urine volume greater than 150 mL and previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

Initial assessments -- completed at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months -- included the health-related quality-of-life (HR-QOL) questionnaire (maximum score, 100; higher score indicates better quality of life), an abbreviated OABSS questionnaire (4 questions; score range, 0-15; higher score indicates more severe symptoms), and urodynamic evaluation. Outcomes included OABSS, HR-QOL score, and urodynamic parameters at the various time points.

Related article:

Is there a link between impaired mobility and urinary incontinence in elderly, community-dwelling women?

Higher dose, greater symptom improvement and higher adverse event rate

At baseline, participants (average age, 31 years) had an average (SD) OABSS of 1.7 (1.6). OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment with both a 100-U and a 200-U dose resulted in significant improvements (compared with baseline levels) in frequency, nocturia, UUI episodes, OABSS, and urodynamic parameters throughout the 9 months. At 9 months, however, the group treated with the 200-U dose had greater improvements, compared with the group who received a 100-U dose, in urinary frequency symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.32 [0.47] vs 1.1 [0.51]; P<.05), nocturia symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.13 [0.34] vs 0.36 [0.49]; P<.05), UUI symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.68 [0.16] vs 1.26 [1.1]; P<.05), and mean (SD) total OABSS (2.6 [2.31] vs 5.3 [2.11]; P<.05). Similarly, at 9 months the 200-U dose resulted in greater improvements in volume at first desire (mean [SD], 291.8 [42.8] vs 246.8 [53.8] mL; P<.05), volume at strong desire (mean [SD], 392.1 [37.3] vs 313.1 [67.4] mL; P<.05), detrusor pressure (mean [SD], 10.4 [4.0] vs 19.2 [7.8] cm H2O; P<.05), and maximum cystometric capacity (mean [SD], 430.5 [34.2] vs 350 [69.1] mL; P<.05) compared with the 100-U dose.

Adverse events. No participant had a PVR urine volume greater than 100 mL at any follow-up visit. Postoperative hematuria occurred in 23% of the group treated with onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U versus in 15% of those treated with a 100-U dose. Similarly, UTIs occurred in 17.5% of the 200-U dose group and in 7.5% of the 100-U dose group. Dysuria was reported in 37.5% and 15% of the 200-U and 100-U dose groups, respectively.

Strengths and limitations. This randomized, open-label trial comparing a single injection of 100 U versus 200 U of onabotulinumtoxinA included mostly women. OAB symptoms and urodynamic parameters improved after treatment with both dose levels, but a longer duration of improvement was seen with the 200-U dose. The cohort had a low baseline OAB severity, based on the OABSS questionnaire, and a young average age of participants, which limits the generalizability of the study results to a population with refractory OAB. The 0% rate of clean intermittent self-catheterization postinjection might be based on the study's criteria for requiring clean intermittent catheterization. In addition, the initial postinjection visit occurred at 1 month, possibly missing participants who had symptoms of retention soon after injection.

Two dose levels (100 U and 200 U) of a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA are associated with comparable OAB symptom and urodyanamic improvements. The benefits of a longer duration of effect with the 200-U dose must be weighed against the possible higher risks of transient hematuria, dysuria, and UTI.

Read: onabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation therapy for UUI.

Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA may control UUI symptoms better than sacral neuromodulation therapy

Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary incontinence in women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1366-1374.

In this multicenter open-label randomized trial, Amundsen and colleagues compared the efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U with that of sacral neuromodulation.

Details of the study

Three hundred sixty-four women with UUI had data available for primary analysis at 6 months. Women were considered eligible for the study if they had 6 or more UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary, persistent symptoms despite anticholinergic therapy, a PVR urine volume of less than 150 mL, and had never previously received either study treatment.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics of the participants. The average (SD) age of the study population was 63 (11.6) years, with an average (SD) daily number of UUI episodes of 5.3 (2.8). The average (SD) body mass index was 32 (8) kg/m2.

Participants were randomly assigned to undergo either sacral neuromodulation (n = 174) or intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U (n = 190). The primary outcome was change from baseline in mean number of daily UUI episodes averaged over 6 months as recorded on a monthly 3-day bladder diary. Secondary outcomes included complete resolution of urgency incontinence, 75% or more reduction in UUI episodes, the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (SF) score (range, 0-100; higher score indicates higher symptom severity), the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire (range, 0-100; higher score indicates better satisfaction), other quality-of-life measures, and adverse events.

Related article:

2015 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Bladder pain syndrome

Greater symptom bother improvement, treatment satisfaction with onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U

Participants treated with onabotulinumtoxinA had a greater mean reduction of 3.9 UUI episodes per day than the sacral neuromodulation group's reduction of 3.3 UUI episodes per day (mean difference, 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13-1.14; P = .01). In addition, complete UUI resolution was higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group as compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (20% vs 4%; P<.001). The onabotulinumtoxinA group also had higher rates of 75% or more reduction of UUI episodes compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (46% vs 26%; P<.001). Over 6 months, both groups had improvements in all quality-of-life measures, but the onabotulinumtoxinA group had greater improvement in symptom bother compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (-46.7 vs -38.6; mean difference, 8.1; 95% CI, 3.0-13.3; P = .002). Furthermore, the onabotulinumtoxinA group had greater treatment satisfaction compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (mean difference, 7.8; 95% CI, 1.6-14.1; P = .01).

Adverse events. Six women (3%) underwent sacral neuromodulation device revision or removal. Approximately 8% of onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants required intermittent self-catheterization at 1 month, 4% at 3 months, and 2% at 6 months. The risk of UTI was higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (35% vs 11%; risk difference, 23%; 95% CI, -33% to -13%; P<.001).

Strengths and limitations. This is a well-designed randomized clinical trial comparing clinical outcomes and adverse events after treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA 200-U versus sacral neuromodulation. The interventions were standardized across investigators at multiple sites, and the study design required close follow-up to assess efficacy and adverse events. The study used a 200-U dose based on reported durability of effect at that time and findings of equivalency between onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and anticholinergic therapy. The US Food and Drug Administration's recommendation to use a 100-U dose in all patients with idiopathic OAB might dissuade clinicians from considering the higher dose of onabotulinumtoxinA. The study was limited by the lack of a placebo group.

Both onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U and sacral neuromodulation provide significant improvement in UUI episodes and quality of life over 6 months. However, while treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA has a likelihood of complete UUI resolution, greater improvements in symptom bother and treatment satisfaction, these benefits must be weighed against the risks of transient catheterization and UTI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines overactive bladder (OAB) as a syndrome of "urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection [UTI] or obvious pathology."1 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reported OAB prevalence to be 15% in US women, with 11% reporting UUI.2 OAB represents a significant health care burden that impacts nearly every aspect of life, including physical, emotional, and psychological domains.3,4 The economic impact is notable; the projected cost is estimated to reach $82.6 billion annually by 2020.5

The American Urological Association (AUA) and the Society for Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine and Urogenital Reconstruction (SUFU) have endorsed an algorithm for use in the evaluation of idiopathic OAB (FIGURE).6 If the patient's symptoms are certain, minimal evaluation is needed and it is reasonable to proceed with first-line therapy, which includes fluid management (decreasing caffeine intake and limiting evening fluid intake), bladder retraining drills such as timed voiding, and improving pelvic floor muscles with the use of biofeedback and functional electrical stimulation.6,7 Pelvic floor muscle training can be facilitated with a referral to a physical therapist trained in pelvic floor muscle education.

If treatment goals are not met with first-line strategies, second-line therapy may be initiated with anticholinergic or β3-adrenergic receptor agonist medications. If symptoms persist after 4 to 8 weeks of pharmacologic therapy, clinicians are encouraged to reassess or refer the patient to a specialist. Further evaluation may include a bladder diary in which the patient documents voided volumes, voiding frequency, and number of incontinent episodes; symptom-specific questionnaires; and/or urodynamic testing.

Related article:

The latest treatments for urinary and fecal incontinence: Which hold water?

Based on that evaluation, the patient may be a candidate for third-line therapy with either intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA, posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), or sacral neuromodulation.

There is a paucity of information comparing third-line therapies. In this Update, we focus on 4 randomized clinical trials that compare third-line treatment options for idiopathic OAB.

Read about how anticholinergic medication and onabotulinumtoxinA compare for treating UUI.

Anticholinergic therapy and onabotulinumtoxinA produce equivalent reductions in the frequency of daily UUI episodes

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Richter HE, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Anticholinergic therapy vs onabotulinumtoxinA for urgency urinary incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1803-1813.

In a double-blind, double-placebo-controlled randomized trial, Visco and colleagues compared anticholinergic medication with onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U for the treatment of women with UUI.

Details of the study

Two hundred forty-one women with moderate to severe UUI received either 6 months of oral anticholinergic therapy (solifenacin 5 mg daily with the option of dose escalation to 10 mg daily or change to trospium XR 60 mg daily based on the Patient Global Symptom Control score) plus a single intradetrusor injection of saline, or a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U plus a 6-month oral placebo regimen.

Inclusion criteria were 5 or more UUI episodes on a 3-day diary, insufficient resolution of symptoms after 2 medications, or being drug naive. Exclusions included a postvoid residual (PVR) urine volume greater than 150 mL or previous therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA.

Participants were scheduled for follow up every 2 to 6 months post randomization, at which time all study medications were discontinued. The primary outcome was reduction from baseline in the mean number of UUI episodes per day over the 6-month period, as recorded in the monthly 3-day bladder diaries. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants with complete resolution of UUI, the proportion of participants with 75% or more reduction in UUI episodes, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (OABq-SF) scores, other symptom-specific questionnaire scores, and adverse events.

Related article:

Which treatments for pelvic floor disorders are backed by evidence?

Both treatments significantly reduced UUI episodes

At baseline, participants reported a mean (SD) of 5.0 (2.7) UUI episodes per day, and 41% of participants were drug naive. Both treatment groups experienced significant reductions compared with baseline in mean UUI episodes, and the reductions were similar between the 2 groups (reduction of 3.4 episodes per day in the anticholinergic group, reduction of 3.3 episodes in the onabotulinumtoxinA group; P = .81). Complete resolution of UUI was more common in the onabotulinumtoxinA group (27%) as compared with the anticholinergic group (13%) (P = .003). There were no differences in improvement in OABq-SF scores (37.05 in the anticholinergic group vs 37.13 in the onabotulinumtoxinA group; P = .98) or other quality-of-life measures.

Adverse events. The anticholinergic group experienced a higher rate of dry mouth compared with the onabotulinumtoxinA group (46% vs 31%; P = .02) but had lower rates of intermittent catheterization use at 2 months (0% vs 5%, P = .01) and UTIs (13% vs 33%, P<.001).

Strengths and limitations. This was a well-designed, multicenter, randomized double-blind, double placebo-controlled trial. The study design allowed for dose escalation and change to another medication for inadequate symptom control and included drug-naive participants, which increases the generalizability of the results. However, current guidelines recommend reserving onabotulinumtoxinA therapy for third-line therapy, thus deterring this treatment's use in the drug-naive population. Additionally, the lack of a pure placebo arm makes it difficult to interpret the extent to which a placebo effect contributed to observed improvements in clinical symptoms.

Through 6 months, both a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and anticholinergic therapy reduce UUI episodes and improve quality-of-life measures in women who have failed medications or are drug naive. Use of onabotulinumtoxinA, however, more likely will lead to complete resolution of UUI, although with an increased risk of transient urinary retention and UTI. Even given the study findings supporting the use of onabotulinumtoxinA over anticholinergic therapy for complete resolution of UUI, it is most appropriate to align with current practice, which includes a trial of pharmacotherapy before proceeding with third-line onabotulinumtoxinA.

Read: onabotulinumtoxinA vs PTNS for OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA has greater 9-month durability for OAB symptoms compared with12 weeks of PTNS

Sherif H, Khalil M, Omar R. Management of refractory idiopathic overactive bladder: intradetrusor injection of botulinum toxin type A versus posterior tibial nerve stimulation. Can J Urol. 2017;24(3):8838-8846.

In this randomized clinical trial, Sherif and colleagues compared the safety and efficacy of a single intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U with that of PTNS for OAB.

Details of the study

Sixty adult men and women with OAB who did not respond to medical therapy were randomly assigned to treatment with either onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U or PTNS. Criteria for exclusion were current UTI, PVR urine volume of more than 150 mL, previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy, previous incontinence surgery or bladder malignancy, or presence of mixed urinary incontinence.

At baseline, participants completed a 3-day bladder diary, an OAB symptom score (OABSS) questionnaire, and urodynamic testing. The OABSS questionnaire included 7 questions (scoring range, 0-28), with higher scores indicating worse symptoms, and included subscales for urgency and quality-of-life measures. Total OABSS, urgency score, quality-of-life score, bladder diary records, and urodynamic testing parameters were assessed at 6, 12, 24, and 36 weeks, along with adverse events.

OnabotulinumtoxinA injections were performed under spinal anesthesia. If PVR urine volume was greater than 200 mL at any follow-up visit, participants were instructed to begin clean intermittent self-catheterization. PTNS was administered as weekly 30-minute sessions for 12 consecutive weeks.

Participants' baseline demographics and symptoms were similar. Average age was 45 years. Averages (SD) for duration of anticholinergic use was 13 (0.8) weeks, UUI episode score was 4.5 (1) on 3-day bladder diary, and OABSS was 22 (2.7). Nine-month data were available for 29 participants in the onabotulinumtoxinA group and for 8 in the PTNS group.

Related article:

Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence

OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment benefits sustained for 9 months

Through 6 months, compared with baseline assessments, both treatment groups had significant improvements in clinical symptoms and OABSS total score, as well as urgency and quality-of-life subscales. At 3 months, urodynamic study parameters were similarly improved from baseline in both groups.

At 9 months, however, only the onabotulinumtoxinA group, compared with the PTNS group, maintained the significant improvement from baseline in 3-day bladder diary voiding episodes (average [SD], 10.7 [1.01] vs 11.6 [1.09]; P = .009), 3-day bladder diary nocturia episodes (average [SD], 3.8 [1.09] vs 4.4 [0.8]; P = .02), and average [SD] UUI episodes over 3 days (3.5 [1.2] vs 4.2 [1.04]; P = .02). Similarly, onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants, compared with those treated with PTNS, maintained improvements at 9 months in average (SD): OABSS total score (19.2 [2.4] vs 20.4 [1.7]; P = .03), urgency scores (10.9 [1.3] vs 11.8 [1.4]; P = .009), urine volume at first desire (177.8 [9.2] vs 171.8 [7.7]), maximum cystometric capacity (304 [17.6] vs 290 [13.1]), and Qmax (mL/sec) (20.7 [1.6] vs 22.2 [1.2]).

Adverse events. Average PVR urine volumes were higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group compared with the PTNS group (36.8 [2.7] vs 32.4 [3.03]; P = .0001) at all time points, and self-catheterization was required in 6.6% of onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants. Urinary tract infection occurred in 6.6% of participants in the onabotulinumtoxinA group and in none of the PTNS group. In the PTNS group, few experienced pain and minor bleeding at the needle site.

Strengths and limitations. This randomized, open-label trial comparing treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and PTNS included both men and women with idiopathic OAB symptoms. The participants were assessed at regular intervals with various measures, and follow-up adherence was good. The sample size was small, so the study may not have been powered to see differences prior to 9 months.

Although at 9 months only the onabotulinumtoxinA group maintained significant improvement over baseline levels, the improvement was diminished, and therefore the clinical meaningfulness is uncertain. Further, participants in the PTNS group did not undergo monthly maintenance therapy after 3 months, which is recommended for those with a 12-week therapeutic response; this may have affected 9-month outcomes in this group. Since the one-time onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U injection was performed under spinal anesthesia, cost comparisons should be considered, since future onabotulinumtoxinA injections would be necessary.

A one-time onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U injection and 12 weeks of PTNS therapy are reasonable short-term options for symptomatic OAB relief after unsuccessful therapy with medications. OnabotulinumtoxinA injection may provide more durable OAB symptom control at 9 months but with a risk of UTI and need for self-catheterization.

Read about using different doses of onabotulinumtoxinA for OAB.

OnabotulinumtoxinA 200-U injection provides longer OAB symptom improvement than 100-U injection

Abdelwahab O, Sherif H, Soliman T, Elbarky I, Eshazly A. Efficacy of botulinum toxin type A 100 units versus 200 units for treatment of refractory idiopathic overactive bladder. Int Braz J Urol. 2015;41(6):1132-1140.

Abdelwahab and colleagues conducted a single-center, randomized clinical trial to investigate the safety and efficacy of a single injection of intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA in 2 different doses (100 U and 200 U) for treatment of OAB.

Details of the study

Eighty adults (63 women, 17 men) who did not benefit from anticholinergic medication during the previous 3 months were randomly assigned to receive either a 100-U (n = 40) or a 200-U (n = 40) injection of onabotulinumtoxinA. Exclusion criteria were PVR urine volume greater than 150 mL and previous radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

Initial assessments -- completed at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, and 9 months -- included the health-related quality-of-life (HR-QOL) questionnaire (maximum score, 100; higher score indicates better quality of life), an abbreviated OABSS questionnaire (4 questions; score range, 0-15; higher score indicates more severe symptoms), and urodynamic evaluation. Outcomes included OABSS, HR-QOL score, and urodynamic parameters at the various time points.

Related article:

Is there a link between impaired mobility and urinary incontinence in elderly, community-dwelling women?

Higher dose, greater symptom improvement and higher adverse event rate

At baseline, participants (average age, 31 years) had an average (SD) OABSS of 1.7 (1.6). OnabotulinumtoxinA treatment with both a 100-U and a 200-U dose resulted in significant improvements (compared with baseline levels) in frequency, nocturia, UUI episodes, OABSS, and urodynamic parameters throughout the 9 months. At 9 months, however, the group treated with the 200-U dose had greater improvements, compared with the group who received a 100-U dose, in urinary frequency symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.32 [0.47] vs 1.1 [0.51]; P<.05), nocturia symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.13 [0.34] vs 0.36 [0.49]; P<.05), UUI symptom scores (mean [SD], 0.68 [0.16] vs 1.26 [1.1]; P<.05), and mean (SD) total OABSS (2.6 [2.31] vs 5.3 [2.11]; P<.05). Similarly, at 9 months the 200-U dose resulted in greater improvements in volume at first desire (mean [SD], 291.8 [42.8] vs 246.8 [53.8] mL; P<.05), volume at strong desire (mean [SD], 392.1 [37.3] vs 313.1 [67.4] mL; P<.05), detrusor pressure (mean [SD], 10.4 [4.0] vs 19.2 [7.8] cm H2O; P<.05), and maximum cystometric capacity (mean [SD], 430.5 [34.2] vs 350 [69.1] mL; P<.05) compared with the 100-U dose.

Adverse events. No participant had a PVR urine volume greater than 100 mL at any follow-up visit. Postoperative hematuria occurred in 23% of the group treated with onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U versus in 15% of those treated with a 100-U dose. Similarly, UTIs occurred in 17.5% of the 200-U dose group and in 7.5% of the 100-U dose group. Dysuria was reported in 37.5% and 15% of the 200-U and 100-U dose groups, respectively.

Strengths and limitations. This randomized, open-label trial comparing a single injection of 100 U versus 200 U of onabotulinumtoxinA included mostly women. OAB symptoms and urodynamic parameters improved after treatment with both dose levels, but a longer duration of improvement was seen with the 200-U dose. The cohort had a low baseline OAB severity, based on the OABSS questionnaire, and a young average age of participants, which limits the generalizability of the study results to a population with refractory OAB. The 0% rate of clean intermittent self-catheterization postinjection might be based on the study's criteria for requiring clean intermittent catheterization. In addition, the initial postinjection visit occurred at 1 month, possibly missing participants who had symptoms of retention soon after injection.

Two dose levels (100 U and 200 U) of a single injection of onabotulinumtoxinA are associated with comparable OAB symptom and urodyanamic improvements. The benefits of a longer duration of effect with the 200-U dose must be weighed against the possible higher risks of transient hematuria, dysuria, and UTI.

Read: onabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation therapy for UUI.

Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA may control UUI symptoms better than sacral neuromodulation therapy

Amundsen CL, Richter HE, Menefee SA, et al; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. OnabotulinumtoxinA vs sacral neuromodulation on refractory urgency urinary incontinence in women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1366-1374.

In this multicenter open-label randomized trial, Amundsen and colleagues compared the efficacy and safety of onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U with that of sacral neuromodulation.

Details of the study

Three hundred sixty-four women with UUI had data available for primary analysis at 6 months. Women were considered eligible for the study if they had 6 or more UUI episodes on a 3-day bladder diary, persistent symptoms despite anticholinergic therapy, a PVR urine volume of less than 150 mL, and had never previously received either study treatment.

There were no differences in baseline characteristics of the participants. The average (SD) age of the study population was 63 (11.6) years, with an average (SD) daily number of UUI episodes of 5.3 (2.8). The average (SD) body mass index was 32 (8) kg/m2.

Participants were randomly assigned to undergo either sacral neuromodulation (n = 174) or intradetrusor injection of onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U (n = 190). The primary outcome was change from baseline in mean number of daily UUI episodes averaged over 6 months as recorded on a monthly 3-day bladder diary. Secondary outcomes included complete resolution of urgency incontinence, 75% or more reduction in UUI episodes, the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire Short Form (SF) score (range, 0-100; higher score indicates higher symptom severity), the Overactive Bladder Satisfaction of Treatment questionnaire (range, 0-100; higher score indicates better satisfaction), other quality-of-life measures, and adverse events.

Related article:

2015 Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Bladder pain syndrome

Greater symptom bother improvement, treatment satisfaction with onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U

Participants treated with onabotulinumtoxinA had a greater mean reduction of 3.9 UUI episodes per day than the sacral neuromodulation group's reduction of 3.3 UUI episodes per day (mean difference, 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13-1.14; P = .01). In addition, complete UUI resolution was higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group as compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (20% vs 4%; P<.001). The onabotulinumtoxinA group also had higher rates of 75% or more reduction of UUI episodes compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (46% vs 26%; P<.001). Over 6 months, both groups had improvements in all quality-of-life measures, but the onabotulinumtoxinA group had greater improvement in symptom bother compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (-46.7 vs -38.6; mean difference, 8.1; 95% CI, 3.0-13.3; P = .002). Furthermore, the onabotulinumtoxinA group had greater treatment satisfaction compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (mean difference, 7.8; 95% CI, 1.6-14.1; P = .01).

Adverse events. Six women (3%) underwent sacral neuromodulation device revision or removal. Approximately 8% of onabotulinumtoxinA-treated participants required intermittent self-catheterization at 1 month, 4% at 3 months, and 2% at 6 months. The risk of UTI was higher in the onabotulinumtoxinA group compared with the sacral neuromodulation group (35% vs 11%; risk difference, 23%; 95% CI, -33% to -13%; P<.001).

Strengths and limitations. This is a well-designed randomized clinical trial comparing clinical outcomes and adverse events after treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA 200-U versus sacral neuromodulation. The interventions were standardized across investigators at multiple sites, and the study design required close follow-up to assess efficacy and adverse events. The study used a 200-U dose based on reported durability of effect at that time and findings of equivalency between onabotulinumtoxinA 100 U and anticholinergic therapy. The US Food and Drug Administration's recommendation to use a 100-U dose in all patients with idiopathic OAB might dissuade clinicians from considering the higher dose of onabotulinumtoxinA. The study was limited by the lack of a placebo group.

Both onabotulinumtoxinA 200 U and sacral neuromodulation provide significant improvement in UUI episodes and quality of life over 6 months. However, while treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA has a likelihood of complete UUI resolution, greater improvements in symptom bother and treatment satisfaction, these benefits must be weighed against the risks of transient catheterization and UTI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al; International Urogynecological Association; International Continence Society. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):4-20.

- Hartmann KE, McPheeters ML, Biller DH, et al. Treatment of overactive bladder in women. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;187:1-120.

- Reynolds,WS, Fowke J, Dmochowski, R. The burden of overactive bladder on US public health. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2016;11(1):8-13.

- Willis-Gray MG, Dieter AA, Geller EJ. Evaluation and management of overactive bladder: strategies for optimizing care. Res Rep Urol. 2016;8:113-122.

- Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology. 2010;75(3):526-532.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP; American Urological Association; Society of Urodyndamics, Female Pelvic Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015; 193(5):1572-1580.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al; American Urological Association; Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 suppl):2455-2463.

- Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al; International Urogynecological Association; International Continence Society. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):4-20.

- Hartmann KE, McPheeters ML, Biller DH, et al. Treatment of overactive bladder in women. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2009;187:1-120.

- Reynolds,WS, Fowke J, Dmochowski, R. The burden of overactive bladder on US public health. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2016;11(1):8-13.

- Willis-Gray MG, Dieter AA, Geller EJ. Evaluation and management of overactive bladder: strategies for optimizing care. Res Rep Urol. 2016;8:113-122.

- Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology. 2010;75(3):526-532.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Faraday M, Vasavada SP; American Urological Association; Society of Urodyndamics, Female Pelvic Medicine. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline amendment. J Urol. 2015; 193(5):1572-1580.

- Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al; American Urological Association; Society of Urodynamics, Female Pelvic Medicine & Urogenital Reconstruction. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012;188(6 suppl):2455-2463.

Top translator apps can help you communicate with patients who have limited English proficiency

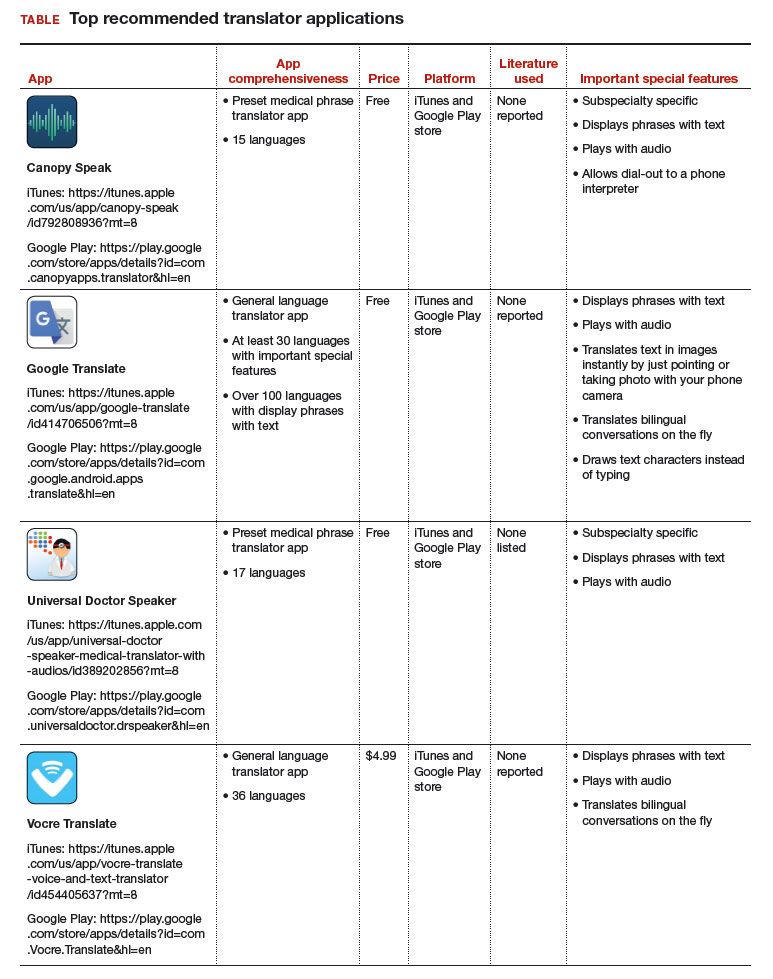

As the population of patients with limited English proficiency increases throughout English-speaking countries, health care providers often need translator services. Medical translator smartphone applications (apps) are useful tools that can provide ad hoc translator services.

According to the US Census Bureau in 2015, more than 60 million individuals — about 19% of Americans — reported speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million said that they speak English “less than very well.”1,2 The top 5 non-English languages spoken at home were Spanish, French, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese, encompassing 72% of non-English speakers.

In the health care sector, translator services are essential for providing accurate and culturally competent care. Current options for translator services include face-to-face interpreters, phone-based translator services, and translator apps on mobile devices. In settings where face-to-face interpreters or phone-based translator services are not available, translator apps may provide reasonable alternatives. My colleagues, Dr. Amrin Khander and Dr. Sara Farag, and I identified and evaluated medical translator apps that are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores to aid clinicians in using such apps during clinical encounters.3

Three types of translator apps

Preset medical phrase translator apps require the user to search for or find a question or statement in order to facilitate a conversation. With these types of apps, a health care provider can choose fully conjugated sentences, which then can be played or read back to the patient in the chosen translated language. Within this group of apps, Canopy Speak and Universal Doctor Speaker are highly accessible, since both apps are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores and both are free.

Medical dictionary apps require the user to search for a medical term in one language to receive a translation in another language. These apps are less useful, but they can help providers find and define specific terms in a given language.

General language translator apps require the user to enter a term, statement, or question in one language and then provide a translation in another language. Google Translate and Vocre Translate are examples.

The top recommended translator apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 I hope the apps described here will help you enhance communication with your patients who have limited English proficiency.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- United States Census Bureau. Detailed language spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Published October 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. US population world clock. http://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- Khander A, Farag S, Chen KT. Identification and rating of medical translator mobile applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system [abstract 321]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5 suppl):101S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000514971.96123.20

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478–1483.

As the population of patients with limited English proficiency increases throughout English-speaking countries, health care providers often need translator services. Medical translator smartphone applications (apps) are useful tools that can provide ad hoc translator services.

According to the US Census Bureau in 2015, more than 60 million individuals — about 19% of Americans — reported speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million said that they speak English “less than very well.”1,2 The top 5 non-English languages spoken at home were Spanish, French, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese, encompassing 72% of non-English speakers.

In the health care sector, translator services are essential for providing accurate and culturally competent care. Current options for translator services include face-to-face interpreters, phone-based translator services, and translator apps on mobile devices. In settings where face-to-face interpreters or phone-based translator services are not available, translator apps may provide reasonable alternatives. My colleagues, Dr. Amrin Khander and Dr. Sara Farag, and I identified and evaluated medical translator apps that are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores to aid clinicians in using such apps during clinical encounters.3

Three types of translator apps

Preset medical phrase translator apps require the user to search for or find a question or statement in order to facilitate a conversation. With these types of apps, a health care provider can choose fully conjugated sentences, which then can be played or read back to the patient in the chosen translated language. Within this group of apps, Canopy Speak and Universal Doctor Speaker are highly accessible, since both apps are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores and both are free.

Medical dictionary apps require the user to search for a medical term in one language to receive a translation in another language. These apps are less useful, but they can help providers find and define specific terms in a given language.

General language translator apps require the user to enter a term, statement, or question in one language and then provide a translation in another language. Google Translate and Vocre Translate are examples.

The top recommended translator apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 I hope the apps described here will help you enhance communication with your patients who have limited English proficiency.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

As the population of patients with limited English proficiency increases throughout English-speaking countries, health care providers often need translator services. Medical translator smartphone applications (apps) are useful tools that can provide ad hoc translator services.

According to the US Census Bureau in 2015, more than 60 million individuals — about 19% of Americans — reported speaking a language other than English at home, and more than 25 million said that they speak English “less than very well.”1,2 The top 5 non-English languages spoken at home were Spanish, French, Chinese, Tagalog, and Vietnamese, encompassing 72% of non-English speakers.

In the health care sector, translator services are essential for providing accurate and culturally competent care. Current options for translator services include face-to-face interpreters, phone-based translator services, and translator apps on mobile devices. In settings where face-to-face interpreters or phone-based translator services are not available, translator apps may provide reasonable alternatives. My colleagues, Dr. Amrin Khander and Dr. Sara Farag, and I identified and evaluated medical translator apps that are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores to aid clinicians in using such apps during clinical encounters.3

Three types of translator apps

Preset medical phrase translator apps require the user to search for or find a question or statement in order to facilitate a conversation. With these types of apps, a health care provider can choose fully conjugated sentences, which then can be played or read back to the patient in the chosen translated language. Within this group of apps, Canopy Speak and Universal Doctor Speaker are highly accessible, since both apps are available from the Apple iTunes and Google Play stores and both are free.

Medical dictionary apps require the user to search for a medical term in one language to receive a translation in another language. These apps are less useful, but they can help providers find and define specific terms in a given language.

General language translator apps require the user to enter a term, statement, or question in one language and then provide a translation in another language. Google Translate and Vocre Translate are examples.

The top recommended translator apps are listed in the TABLE alphabetically and are detailed with a shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (app comprehensiveness, price, platform, literature use, and important special features).4 I hope the apps described here will help you enhance communication with your patients who have limited English proficiency.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- United States Census Bureau. Detailed language spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Published October 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. US population world clock. http://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- Khander A, Farag S, Chen KT. Identification and rating of medical translator mobile applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system [abstract 321]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5 suppl):101S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000514971.96123.20

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478–1483.

- United States Census Bureau. Detailed language spoken at home and ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over: 2009–2013. http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/2009-2013-lang-tables.html. Published October 2015. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. US population world clock. http://www.census.gov/popclock/?intcmp=home_pop. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- Khander A, Farag S, Chen KT. Identification and rating of medical translator mobile applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system [abstract 321]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(5 suppl):101S. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000514971.96123.20

- Chyjek K, Farag S, Chen KT. Rating pregnancy wheel applications using the APPLICATIONS scoring system. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1478–1483.

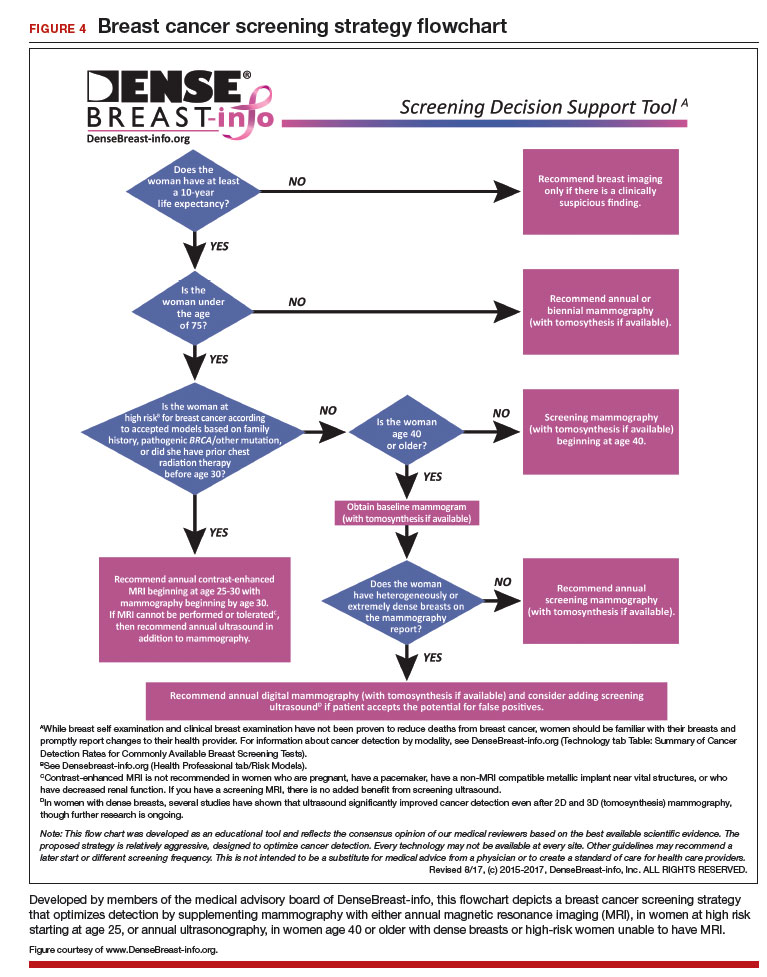

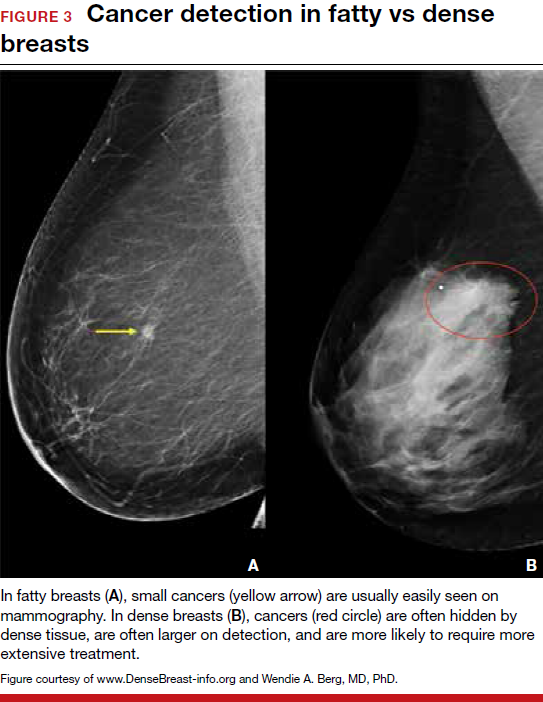

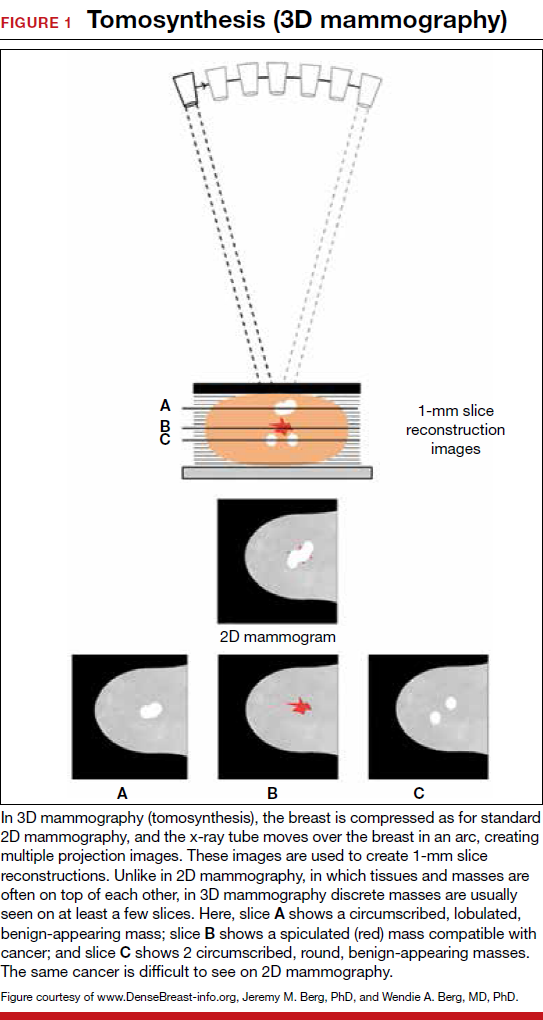

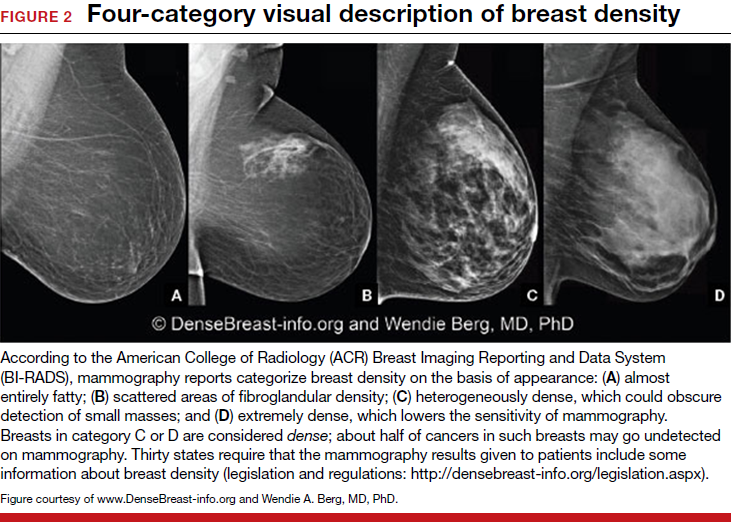

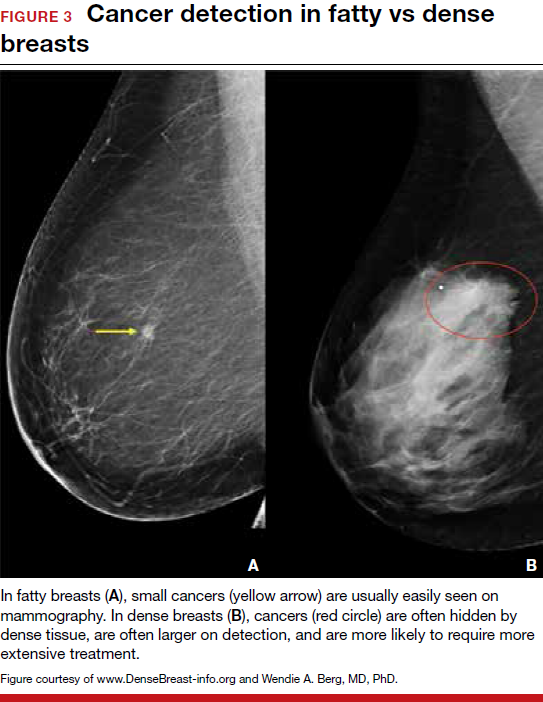

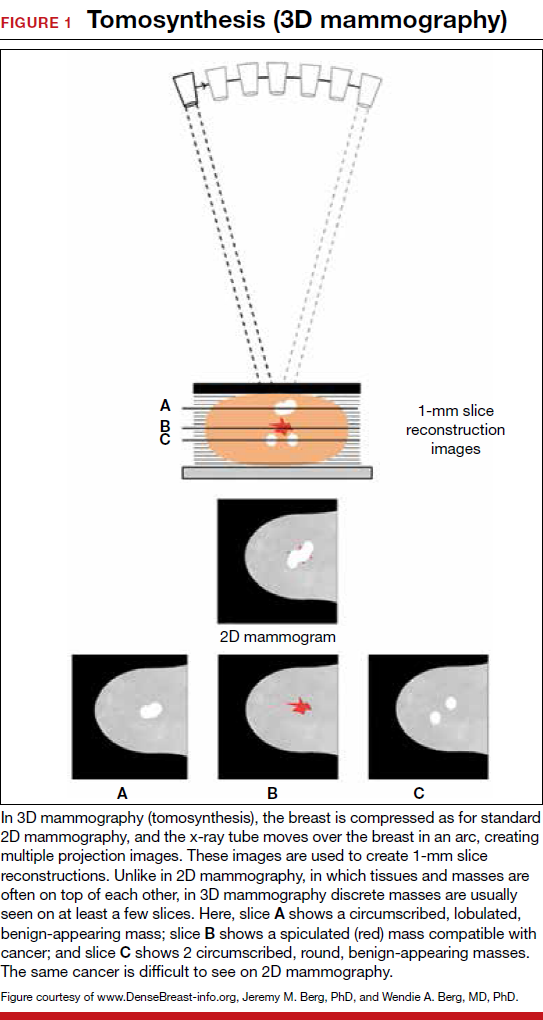

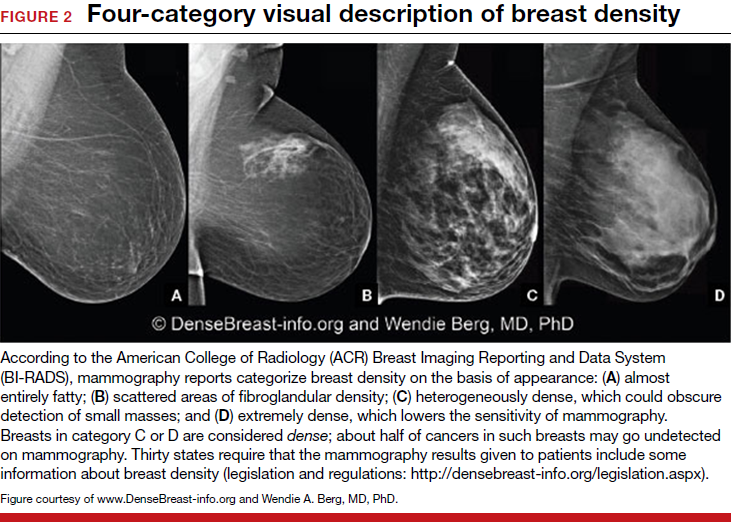

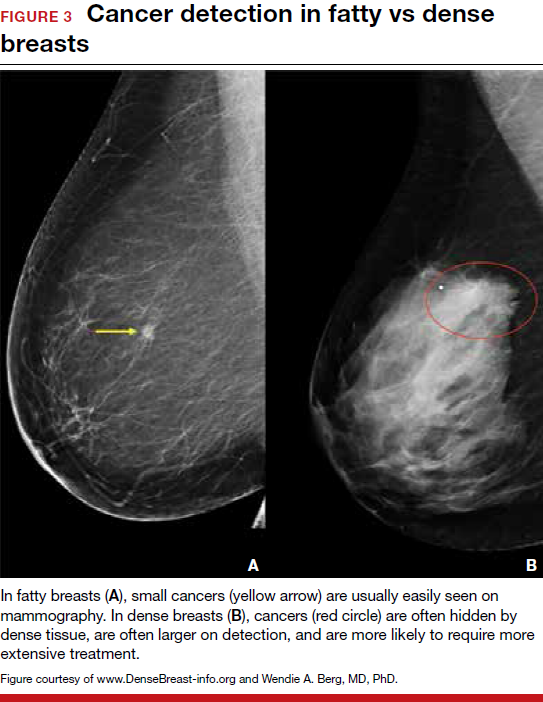

Breast density and optimal screening for breast cancer

MY STORY: Prologue