User login

Hyperprogression on immunotherapy: When outcomes are much worse

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has ushered in a new era of cancer therapy, with some patients showing dramatic responses and significantly better outcomes than with other therapies across many cancer types. But some patients do worse, sometimes much worse.

A subset of patients who undergo immunotherapy experience unexpected, rapid disease progression, with a dramatic acceleration of disease trajectory. They also have a shorter progression-free survival and overall survival than would have been expected.

This has been described as hyperprogression and has been termed “hyperprogressive disease” (HPD). It has been seen in a variety of cancers; the incidence ranges from 4% to 29% in the studies reported to date.

There has been some debate over whether this is a real phenomenon or whether it is part of the natural course of disease.

HPD is a “provocative phenomenon,” wrote the authors of a recent commentary entitled “Hyperprogression and Immunotherapy: Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?”

“This phenomenon has polarized oncologists who debate that this could still reflect the natural history of the disease,” said the author of another commentary.

But the tide is now turning toward acceptance of HPD, said Kartik Sehgal, MD, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard University, both in Boston.

“With publication of multiple clinical reports of different cancer types worldwide, hyperprogression is now accepted by most oncologists to be a true phenomenon rather than natural progression of disease,” Dr. Sehgal said.

He authored an invited commentary in JAMA Network Openabout one of the latest meta-analyses (JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4[3]:e211136) to investigate HPD during immunotherapy. One of the biggest issues is that the studies that have reported on HPD have been retrospective, with a lack of comparator groups and a lack of a standardized definition of hyperprogression. Dr. Sehgal emphasized the need to study hyperprogression in well-designed prospective studies.

Existing data on HPD

HPD was described as “a new pattern of progression” seen in patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a 2017 article published in Clinical Cancer Research. Authors Stephane Champiat, MD, PhD, of Institut Gustave Roussy, Universite Paris Saclay, Villejuif, France, and colleagues cited “anecdotal occurrences” of HPD among patients in phase 1 trials of anti–PD-1/PD-L1 agents.

In that study, HPD was defined by tumor growth rate ratio. The incidence was 9% among 213 patients.

The findings raised concerns about treating elderly patients with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy, according to the authors, who called for further study.

That same year, Roberto Ferrara, MD, and colleagues from the Insitut Gustave Roussy reported additional data indicating an incidence of HPD of 16% among 333 patients with non–small cell lung cancer who underwent immunotherapy at eight centers from 2012 to 2017. The findings, which were presented at the 2017 World Conference on Lung Cancer and reported at the time by this news organization, also showed that the incidence of HPD was higher with immunotherapy than with single-agent chemotherapy (5%).

Median overall survival (OS) was just 3.4 months among those with HPD, compared with 13 months in the overall study population – worse, even, than the median 5.4-month OS observed among patients with progressive disease who received immunotherapy.

In the wake of these findings, numerous researchers have attempted to better define HPD, its incidence, and patient factors associated with developing HPD while undergoing immunotherapy.

However, there is little so far to show for those efforts, Vivek Subbiah, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an interview.

“Many questions remain to be answered,” said Dr. Subbiah, clinical medical director of the Clinical Center for Targeted Therapy in the division of cancer medicine at MD Anderson. He was the senior author of the “Fact, Fiction, or Alternative Fact?” commentary.

Work is underway to elucidate biological mechanisms. Some groups have implicated the Fc region of antibodies. Another group has reported EGFR and MDM2/MDM4 amplifications in patients with HPD, Dr. Subbiah and colleagues noted.

Other “proposed contributing pathological mechanisms include modulation of tumor immune microenvironment through macrophages and regulatory T cells as well as activation of oncogenic signaling pathways,” noted Dr. Sehgal.

Both groups of authors emphasize the urgent need for prospective studies.

It is imperative to confirm underlying biology, predict which patients are at risk, and identify therapeutic directions for patients who experience HPD, Dr. Subbiah said.

The main challenge is defining HPD, he added. Definitions that have been proposed include tumor growth at least two times greater than in control persons, a 15% increase in tumor burden in a set period, and disease progression of 50% from the first evaluation before treatment, he said.

The recent meta-analysis by Hyo Jung Park, MD, PhD, and colleagues, which Dr. Sehgal addressed in his invited commentary, highlights the many approaches used for defining HPD.

Depending on the definition used, the incidence of HPD across 24 studies involving more than 3,100 patients ranged from 5.9% to 43.1%.

“Hyperprogressive disease could be overestimated or underestimated based on current assessment,” Dr. Park and colleagues concluded. They highlighted the importance of “establishing uniform and clinically relevant criteria based on currently available evidence.”

Steps for solving the HPD mystery

“I think we need to come up with consensus criteria for an HPD definition. We need a unified definition,” Dr. Subbiah said. “We also need to design prospective studies to prove or disprove the immunotherapy-HPD association.”

Prospective registries with independent review of patients with suspected immunotherapy-related HPD would be useful for assessing the true incidence and the biology of HPD among patients undergoing immunotherapy, he suggested.

“We need to know the immunologic signals of HPD. This can give us an idea if patients can be prospectively identified for being at risk,” he said. “We also need to know what to do if they are at risk.”

Dr. Sehgal also called for consensus on an HPD definition, with input from a multidisciplinary group that includes “colleagues from radiology, medical oncology, radiation oncology. Getting expertise from different disciplines would be helpful,” he said.

Dr. Park and colleagues suggested several key requirements for an optimal HP definition, such as the inclusion of multiple variables for measuring tumor growth acceleration, “sufficiently quantitative” criteria for determining time to failure, and establishment of a standardized measure of tumor growth acceleration.

The agreed-upon definition of HPD could be applied to patients in a prospective registry and to existing trial data, Dr. Sehgal said.

“Eventually, the goal of this exercise is to [determine] how we can help our patients the best, having a biomarker that can at least inform us in terms of being aware and being proactive in terms of looking for this ... so that interventions can be brought on earlier,” he said.

“If we know what may be a biological mechanism, we can design trials that are designed to look at how to overcome that HPD,” he said.

Dr. Sehgal said he believes HPD is triggered in some way by treatment, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, but perhaps in different ways for each.

He estimated the true incidence of immunotherapy-related HPD will be in the 9%-10% range.

“This is a substantial number of patients, so it’s important that we try to understand this phenomenon, using, again, uniform criteria,” he said.

Current treatment decision-making

Until more is known, Dr. Sehgal said he considers the potential risk factors when treating patients with immunotherapy.

For example, the presence of MDM2 or MDM4 amplification on a genomic profile may factor into his treatment decision-making when it comes to using immunotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with chemotherapy, he said.

“Is that the only factor that is going to make me choose one thing or another? No,” Dr. Sehgal said. However, he said it would make him more “proactive in making sure the patient is doing clinically okay” and in determining when to obtain on-treatment imaging studies.

Dr. Subbiah emphasized the relative benefit of immunotherapy, noting that survival with chemotherapy for many difficult-to-treat cancers in the relapsed/refractory metastatic setting is less than 2 years.

Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors has allowed some of these patients to live longer (with survival reported to be more than 10 years for patients with metastatic melanoma).

“Immunotherapy has been a game changer; it has been transformative in the lives of these patients,” Dr. Subbiah said. “So unless there is any other contraindication, the benefit of receiving immunotherapy for an approved indication far outweighs the risk of HPD.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA panel votes against 2 cancer indications but backs 4 of 6

Federal advisers have supported the efforts of pharmaceutical companies in four of six cases in which these firms are fighting to maintain cancer indications for approved drugs. The advisers voted against the companies in two cases.

The staff of the Food and Drug Administration will now consider these votes as they decide what to do regarding the six cases of what they have termed “dangling” accelerated approvals.

“One of the reasons I think we’re convening today is to prevent these accelerated approvals from dangling ad infinitum,” commented one of the members of the advisory panel.

In these cases, companies have been unable to prove the expected benefits that led the FDA to grant accelerated approvals for these indications.

These accelerated approvals, which are often based on surrogate endpoints, such as overall response rates, are granted on the condition that further findings show a clinical benefit – such as in progression-free survival or overall survival – in larger trials.

The FDA tasked its Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) with conducting the review of the six accelerated approvals for cancer indications at a 3-day meeting (April 27-29).

These reviews were only for specific cancer indications and will not lead to the removal of drugs from the market. These drugs have already been approved for several cancer indications. For example, one of the drugs that was reviewed, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), is approved in the United States for 28 indications.

The FDA is facing growing pains in its efforts to manage the rapidly changing landscape for these immune checkpoint inhibitors. This field of medicine has experienced an “unprecedented level of drug development” in recent years, FDA officials said in briefing materials, owing in part to the agency’s willingness to accept surrogate markers for accelerated approvals. Although some companies have struggled with these, others have built strong cases for the use of their checkpoint inhibitors for these indications.

The ODAC panelists, for example, noted the emergence of nivolumab (Opdivo) as an option for patients with gastric cancer as a reason for seeking to withdraw an indication for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for this disease.

Just weeks before the meeting, on April 16, the FDA approved nivolumab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, gastroesophageal junction cancer, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. This was a full approval based on data showing an overall survival benefit from a phase 3 trial.

Votes by indication

On April 29, the last day of the meeting, the ODAC panel voted 6-2 against maintaining pembrolizumab’s indication as monotherapy for an advanced form of gastric cancer. This was an accelerated approval (granted in 2017) that was based on overall response rates from an open-label trial.

That last day of the meeting also saw another negative vote. On April 29, the ODAC panel voted 5-4 against maintaining an indication for nivolumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who were previously treated with sorafenib (Nexavar).

This accelerated approval for nivolumab was granted in 2017. The FDA said it had requested ODAC’s feedback on this indication because of the recent full approval of another checkpoint inhibitor for HCC, atezolizumab (Tecentriq), in combination with bevacizumab (Avastin) for patients with unresectable or metastatic diseases who have not received prior systemic therapy. This full approval (in May 2020) was based on an overall survival benefit.

There was one last vote on the third day of the meeting, and it was positive. The ODAC panel voted 8-0 in favor of maintaining the indication for the use of pembrolizumab as monotherapy for patients with HCC who have previously been treated with sorafenib.

The FDA altered the composition of the ODAC panel during the week, adding members in some cases who had expertise in particular cancers. That led to different totals for the week’s ODAC votes, as shown in the tallies summarized below.

On the first day of the meeting (April 27), the ODAC panel voted 7-2 in favor of maintaining a breast cancer indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq). This covered use of the immunotherapy in combination with nab-paclitaxel for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer whose tumors express PD-L1.

The second day of the meeting (April 28) also saw two positive votes. The ODAC panel voted 10-1 for maintaining the indication for atezolizumab for the first-line treatment of cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma, pending final overall survival results from the IMvigor130 trial. The panel also voted 5-3 for maintaining the indication for pembrolizumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and whose tumors express PD-L1.

The FDA is not bound to follow the voting and recommendations of its advisory panels, but it usually does so.

Managing shifts in treatment

In both of the cases in which ODAC voted against maintaining indications, Richard Pazdur, MD, the FDA’s top regulator for cancer medicines, jumped into the debate. Dr. Pazdur countered arguments put forward by representatives of the manufacturers as they sought to maintain indications for their drugs.

Merck officials and representatives argued for pembrolizumab, saying that maintaining the gastric cancer indication might help patients whose disease has progressed despite earlier treatment.

Dr. Pazdur emphasized that the agency would help Merck and physicians to have access to pembrolizumab for these patients even if this one indication were to be withdrawn. But Dr. Pazdur and ODAC members also noted the recent shift in the landscape for gastric cancer, with the recent approval of a new indication for nivolumab.

“I want to emphasize to the patient community out there [that] we firmly believe in the role of checkpoint inhibitors in this disease,” Dr. Pazdur said during the discussion of the indication for pembrolizumab for gastric cancer. “We have to be cognizant of what is the appropriate setting for that, and it currently is in the first line.”

Dr. Pazdur noted that two studies had failed to confirm the expected benefit from pembrolizumab for patients with more advanced disease. Still, if “small numbers” of patients with advanced disease wanted access to Merck’s drug, the FDA and the company could accommodate them. The FDA could delay the removal of the gastric indication to allow patients to continue receiving it. The FDA also could work with physicians on other routes to provide the medicine, such as through single-patient investigational new drug applications or an expanded access program.

“Or Merck can alternatively give the drug gratis to patients,” Dr. Pazdur said.

#ProjectFacilitate for expanded access

One of Merck’s speakers at the ODAC meeting, Peter Enzinger, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, objected to Dr. Pazdur’s plan.

A loss of the gastric indication for pembrolizumab would result in patients with advanced cancer missing out on a chance to try this therapy. Some patients will not have had a chance to try a checkpoint inhibitor earlier in their treatment, and a loss of the indication would cost them that opportunity, he said.

“An expanded-access program sounds very nice, but the reality is that our patients are incredibly sick and that weeks matter,” Dr. Enzinger said, citing administrative hurdles as a barrier to treatment.

“Our patients just don’t have the time for that, and therefore I don’t think an expanded access program is the way to go,” Dr. Enzinger said.

Dr. Pazdur responded to these objections by highlighting an initiative called Project Facilitate at the FDA’s Oncology Center for Excellence. During the meeting, Dr. Pazdur’s division used its @FDAOncology Twitter handle to draw attention to this project.

ODAC panelist Diane Reidy-Lagunes, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said she had struggled with this vote. She was one of the two panelists to vote in favor of keeping the indication.

“This is also incredibly hard for me. I actually changed it at the last minute,” she said of her vote.

But Dr. Reidy-Lagunes said she was concerned that some patients with advanced disease might not be able to get a checkpoint inhibitor.

“With disparities in healthcare and differences in the way that patients are treated throughout our country, I was nervous that they may not be able to get treated,” she said, noting that she shared her fellow panelists’ doubts about use of pembrolizumab as third-line treatment, owing to negative results in trials.

ODAC member David Mitchell, who served as a consumer representative, also said he found the vote on the gastric indication for pembrolizumab to be a difficult decision.

“As a patient with incurable cancer who’s now being given all three major classes of drugs to treat my disease in combination, these issues really cut close to home,” Mr. Mitchell said.

He said the expectation that the FDA’s expanded access program could help patients with advanced disease try pembrolizumab helped him decide to vote with the 6-2 majority against maintaining this gastric cancer approval.

His vote was based on “the changing treatment landscape.” There is general agreement that the patients in question should receive checkpoint inhibitors as first-line treatment, not third-line treatment, Mr. Mitchell said. The FDA should delay a withdrawal of the approval for pembrolizumab in this case and should allow a transition for those who missed out on treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor earlier in the disease course, he suggested.

“To protect the safety and well-being of patients, we have to base decisions on data,” Mr. Mitchell said. “The data don’t support maintaining the indication” for pembrolizumab.

Close split on nivolumab

In contrast to the 6-2 vote against maintaining the pembrolizumab indication, the ODAC panel split more closely, 5-4, on the question of maintaining an indication for the use as monotherapy of nivolumab in HCC.

ODAC panelist Philip C. Hoffman, MD, of the University of Chicago was among those who supported keeping the indication.

“There’s still an unmet need for second-line immunotherapy because there will always be some patients who are poor candidates for bevacizumab or who are not tolerating or responding to sorafenib,” he said.

ODAC panelist Mark A. Lewis, MD, of Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, said he voted “no” in part because he doubted that Bristol-Myers Squibb would be able to soon produce data for nivolumab that was needed to support this indication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal advisers have supported the efforts of pharmaceutical companies in four of six cases in which these firms are fighting to maintain cancer indications for approved drugs. The advisers voted against the companies in two cases.

The staff of the Food and Drug Administration will now consider these votes as they decide what to do regarding the six cases of what they have termed “dangling” accelerated approvals.

“One of the reasons I think we’re convening today is to prevent these accelerated approvals from dangling ad infinitum,” commented one of the members of the advisory panel.

In these cases, companies have been unable to prove the expected benefits that led the FDA to grant accelerated approvals for these indications.

These accelerated approvals, which are often based on surrogate endpoints, such as overall response rates, are granted on the condition that further findings show a clinical benefit – such as in progression-free survival or overall survival – in larger trials.

The FDA tasked its Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) with conducting the review of the six accelerated approvals for cancer indications at a 3-day meeting (April 27-29).

These reviews were only for specific cancer indications and will not lead to the removal of drugs from the market. These drugs have already been approved for several cancer indications. For example, one of the drugs that was reviewed, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), is approved in the United States for 28 indications.

The FDA is facing growing pains in its efforts to manage the rapidly changing landscape for these immune checkpoint inhibitors. This field of medicine has experienced an “unprecedented level of drug development” in recent years, FDA officials said in briefing materials, owing in part to the agency’s willingness to accept surrogate markers for accelerated approvals. Although some companies have struggled with these, others have built strong cases for the use of their checkpoint inhibitors for these indications.

The ODAC panelists, for example, noted the emergence of nivolumab (Opdivo) as an option for patients with gastric cancer as a reason for seeking to withdraw an indication for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for this disease.

Just weeks before the meeting, on April 16, the FDA approved nivolumab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, gastroesophageal junction cancer, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. This was a full approval based on data showing an overall survival benefit from a phase 3 trial.

Votes by indication

On April 29, the last day of the meeting, the ODAC panel voted 6-2 against maintaining pembrolizumab’s indication as monotherapy for an advanced form of gastric cancer. This was an accelerated approval (granted in 2017) that was based on overall response rates from an open-label trial.

That last day of the meeting also saw another negative vote. On April 29, the ODAC panel voted 5-4 against maintaining an indication for nivolumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who were previously treated with sorafenib (Nexavar).

This accelerated approval for nivolumab was granted in 2017. The FDA said it had requested ODAC’s feedback on this indication because of the recent full approval of another checkpoint inhibitor for HCC, atezolizumab (Tecentriq), in combination with bevacizumab (Avastin) for patients with unresectable or metastatic diseases who have not received prior systemic therapy. This full approval (in May 2020) was based on an overall survival benefit.

There was one last vote on the third day of the meeting, and it was positive. The ODAC panel voted 8-0 in favor of maintaining the indication for the use of pembrolizumab as monotherapy for patients with HCC who have previously been treated with sorafenib.

The FDA altered the composition of the ODAC panel during the week, adding members in some cases who had expertise in particular cancers. That led to different totals for the week’s ODAC votes, as shown in the tallies summarized below.

On the first day of the meeting (April 27), the ODAC panel voted 7-2 in favor of maintaining a breast cancer indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq). This covered use of the immunotherapy in combination with nab-paclitaxel for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer whose tumors express PD-L1.

The second day of the meeting (April 28) also saw two positive votes. The ODAC panel voted 10-1 for maintaining the indication for atezolizumab for the first-line treatment of cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma, pending final overall survival results from the IMvigor130 trial. The panel also voted 5-3 for maintaining the indication for pembrolizumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and whose tumors express PD-L1.

The FDA is not bound to follow the voting and recommendations of its advisory panels, but it usually does so.

Managing shifts in treatment

In both of the cases in which ODAC voted against maintaining indications, Richard Pazdur, MD, the FDA’s top regulator for cancer medicines, jumped into the debate. Dr. Pazdur countered arguments put forward by representatives of the manufacturers as they sought to maintain indications for their drugs.

Merck officials and representatives argued for pembrolizumab, saying that maintaining the gastric cancer indication might help patients whose disease has progressed despite earlier treatment.

Dr. Pazdur emphasized that the agency would help Merck and physicians to have access to pembrolizumab for these patients even if this one indication were to be withdrawn. But Dr. Pazdur and ODAC members also noted the recent shift in the landscape for gastric cancer, with the recent approval of a new indication for nivolumab.

“I want to emphasize to the patient community out there [that] we firmly believe in the role of checkpoint inhibitors in this disease,” Dr. Pazdur said during the discussion of the indication for pembrolizumab for gastric cancer. “We have to be cognizant of what is the appropriate setting for that, and it currently is in the first line.”

Dr. Pazdur noted that two studies had failed to confirm the expected benefit from pembrolizumab for patients with more advanced disease. Still, if “small numbers” of patients with advanced disease wanted access to Merck’s drug, the FDA and the company could accommodate them. The FDA could delay the removal of the gastric indication to allow patients to continue receiving it. The FDA also could work with physicians on other routes to provide the medicine, such as through single-patient investigational new drug applications or an expanded access program.

“Or Merck can alternatively give the drug gratis to patients,” Dr. Pazdur said.

#ProjectFacilitate for expanded access

One of Merck’s speakers at the ODAC meeting, Peter Enzinger, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, objected to Dr. Pazdur’s plan.

A loss of the gastric indication for pembrolizumab would result in patients with advanced cancer missing out on a chance to try this therapy. Some patients will not have had a chance to try a checkpoint inhibitor earlier in their treatment, and a loss of the indication would cost them that opportunity, he said.

“An expanded-access program sounds very nice, but the reality is that our patients are incredibly sick and that weeks matter,” Dr. Enzinger said, citing administrative hurdles as a barrier to treatment.

“Our patients just don’t have the time for that, and therefore I don’t think an expanded access program is the way to go,” Dr. Enzinger said.

Dr. Pazdur responded to these objections by highlighting an initiative called Project Facilitate at the FDA’s Oncology Center for Excellence. During the meeting, Dr. Pazdur’s division used its @FDAOncology Twitter handle to draw attention to this project.

ODAC panelist Diane Reidy-Lagunes, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said she had struggled with this vote. She was one of the two panelists to vote in favor of keeping the indication.

“This is also incredibly hard for me. I actually changed it at the last minute,” she said of her vote.

But Dr. Reidy-Lagunes said she was concerned that some patients with advanced disease might not be able to get a checkpoint inhibitor.

“With disparities in healthcare and differences in the way that patients are treated throughout our country, I was nervous that they may not be able to get treated,” she said, noting that she shared her fellow panelists’ doubts about use of pembrolizumab as third-line treatment, owing to negative results in trials.

ODAC member David Mitchell, who served as a consumer representative, also said he found the vote on the gastric indication for pembrolizumab to be a difficult decision.

“As a patient with incurable cancer who’s now being given all three major classes of drugs to treat my disease in combination, these issues really cut close to home,” Mr. Mitchell said.

He said the expectation that the FDA’s expanded access program could help patients with advanced disease try pembrolizumab helped him decide to vote with the 6-2 majority against maintaining this gastric cancer approval.

His vote was based on “the changing treatment landscape.” There is general agreement that the patients in question should receive checkpoint inhibitors as first-line treatment, not third-line treatment, Mr. Mitchell said. The FDA should delay a withdrawal of the approval for pembrolizumab in this case and should allow a transition for those who missed out on treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor earlier in the disease course, he suggested.

“To protect the safety and well-being of patients, we have to base decisions on data,” Mr. Mitchell said. “The data don’t support maintaining the indication” for pembrolizumab.

Close split on nivolumab

In contrast to the 6-2 vote against maintaining the pembrolizumab indication, the ODAC panel split more closely, 5-4, on the question of maintaining an indication for the use as monotherapy of nivolumab in HCC.

ODAC panelist Philip C. Hoffman, MD, of the University of Chicago was among those who supported keeping the indication.

“There’s still an unmet need for second-line immunotherapy because there will always be some patients who are poor candidates for bevacizumab or who are not tolerating or responding to sorafenib,” he said.

ODAC panelist Mark A. Lewis, MD, of Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, said he voted “no” in part because he doubted that Bristol-Myers Squibb would be able to soon produce data for nivolumab that was needed to support this indication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal advisers have supported the efforts of pharmaceutical companies in four of six cases in which these firms are fighting to maintain cancer indications for approved drugs. The advisers voted against the companies in two cases.

The staff of the Food and Drug Administration will now consider these votes as they decide what to do regarding the six cases of what they have termed “dangling” accelerated approvals.

“One of the reasons I think we’re convening today is to prevent these accelerated approvals from dangling ad infinitum,” commented one of the members of the advisory panel.

In these cases, companies have been unable to prove the expected benefits that led the FDA to grant accelerated approvals for these indications.

These accelerated approvals, which are often based on surrogate endpoints, such as overall response rates, are granted on the condition that further findings show a clinical benefit – such as in progression-free survival or overall survival – in larger trials.

The FDA tasked its Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) with conducting the review of the six accelerated approvals for cancer indications at a 3-day meeting (April 27-29).

These reviews were only for specific cancer indications and will not lead to the removal of drugs from the market. These drugs have already been approved for several cancer indications. For example, one of the drugs that was reviewed, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), is approved in the United States for 28 indications.

The FDA is facing growing pains in its efforts to manage the rapidly changing landscape for these immune checkpoint inhibitors. This field of medicine has experienced an “unprecedented level of drug development” in recent years, FDA officials said in briefing materials, owing in part to the agency’s willingness to accept surrogate markers for accelerated approvals. Although some companies have struggled with these, others have built strong cases for the use of their checkpoint inhibitors for these indications.

The ODAC panelists, for example, noted the emergence of nivolumab (Opdivo) as an option for patients with gastric cancer as a reason for seeking to withdraw an indication for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for this disease.

Just weeks before the meeting, on April 16, the FDA approved nivolumab plus chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, gastroesophageal junction cancer, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. This was a full approval based on data showing an overall survival benefit from a phase 3 trial.

Votes by indication

On April 29, the last day of the meeting, the ODAC panel voted 6-2 against maintaining pembrolizumab’s indication as monotherapy for an advanced form of gastric cancer. This was an accelerated approval (granted in 2017) that was based on overall response rates from an open-label trial.

That last day of the meeting also saw another negative vote. On April 29, the ODAC panel voted 5-4 against maintaining an indication for nivolumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who were previously treated with sorafenib (Nexavar).

This accelerated approval for nivolumab was granted in 2017. The FDA said it had requested ODAC’s feedback on this indication because of the recent full approval of another checkpoint inhibitor for HCC, atezolizumab (Tecentriq), in combination with bevacizumab (Avastin) for patients with unresectable or metastatic diseases who have not received prior systemic therapy. This full approval (in May 2020) was based on an overall survival benefit.

There was one last vote on the third day of the meeting, and it was positive. The ODAC panel voted 8-0 in favor of maintaining the indication for the use of pembrolizumab as monotherapy for patients with HCC who have previously been treated with sorafenib.

The FDA altered the composition of the ODAC panel during the week, adding members in some cases who had expertise in particular cancers. That led to different totals for the week’s ODAC votes, as shown in the tallies summarized below.

On the first day of the meeting (April 27), the ODAC panel voted 7-2 in favor of maintaining a breast cancer indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq). This covered use of the immunotherapy in combination with nab-paclitaxel for patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer whose tumors express PD-L1.

The second day of the meeting (April 28) also saw two positive votes. The ODAC panel voted 10-1 for maintaining the indication for atezolizumab for the first-line treatment of cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma, pending final overall survival results from the IMvigor130 trial. The panel also voted 5-3 for maintaining the indication for pembrolizumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who are not eligible for cisplatin-containing chemotherapy and whose tumors express PD-L1.

The FDA is not bound to follow the voting and recommendations of its advisory panels, but it usually does so.

Managing shifts in treatment

In both of the cases in which ODAC voted against maintaining indications, Richard Pazdur, MD, the FDA’s top regulator for cancer medicines, jumped into the debate. Dr. Pazdur countered arguments put forward by representatives of the manufacturers as they sought to maintain indications for their drugs.

Merck officials and representatives argued for pembrolizumab, saying that maintaining the gastric cancer indication might help patients whose disease has progressed despite earlier treatment.

Dr. Pazdur emphasized that the agency would help Merck and physicians to have access to pembrolizumab for these patients even if this one indication were to be withdrawn. But Dr. Pazdur and ODAC members also noted the recent shift in the landscape for gastric cancer, with the recent approval of a new indication for nivolumab.

“I want to emphasize to the patient community out there [that] we firmly believe in the role of checkpoint inhibitors in this disease,” Dr. Pazdur said during the discussion of the indication for pembrolizumab for gastric cancer. “We have to be cognizant of what is the appropriate setting for that, and it currently is in the first line.”

Dr. Pazdur noted that two studies had failed to confirm the expected benefit from pembrolizumab for patients with more advanced disease. Still, if “small numbers” of patients with advanced disease wanted access to Merck’s drug, the FDA and the company could accommodate them. The FDA could delay the removal of the gastric indication to allow patients to continue receiving it. The FDA also could work with physicians on other routes to provide the medicine, such as through single-patient investigational new drug applications or an expanded access program.

“Or Merck can alternatively give the drug gratis to patients,” Dr. Pazdur said.

#ProjectFacilitate for expanded access

One of Merck’s speakers at the ODAC meeting, Peter Enzinger, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, objected to Dr. Pazdur’s plan.

A loss of the gastric indication for pembrolizumab would result in patients with advanced cancer missing out on a chance to try this therapy. Some patients will not have had a chance to try a checkpoint inhibitor earlier in their treatment, and a loss of the indication would cost them that opportunity, he said.

“An expanded-access program sounds very nice, but the reality is that our patients are incredibly sick and that weeks matter,” Dr. Enzinger said, citing administrative hurdles as a barrier to treatment.

“Our patients just don’t have the time for that, and therefore I don’t think an expanded access program is the way to go,” Dr. Enzinger said.

Dr. Pazdur responded to these objections by highlighting an initiative called Project Facilitate at the FDA’s Oncology Center for Excellence. During the meeting, Dr. Pazdur’s division used its @FDAOncology Twitter handle to draw attention to this project.

ODAC panelist Diane Reidy-Lagunes, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said she had struggled with this vote. She was one of the two panelists to vote in favor of keeping the indication.

“This is also incredibly hard for me. I actually changed it at the last minute,” she said of her vote.

But Dr. Reidy-Lagunes said she was concerned that some patients with advanced disease might not be able to get a checkpoint inhibitor.

“With disparities in healthcare and differences in the way that patients are treated throughout our country, I was nervous that they may not be able to get treated,” she said, noting that she shared her fellow panelists’ doubts about use of pembrolizumab as third-line treatment, owing to negative results in trials.

ODAC member David Mitchell, who served as a consumer representative, also said he found the vote on the gastric indication for pembrolizumab to be a difficult decision.

“As a patient with incurable cancer who’s now being given all three major classes of drugs to treat my disease in combination, these issues really cut close to home,” Mr. Mitchell said.

He said the expectation that the FDA’s expanded access program could help patients with advanced disease try pembrolizumab helped him decide to vote with the 6-2 majority against maintaining this gastric cancer approval.

His vote was based on “the changing treatment landscape.” There is general agreement that the patients in question should receive checkpoint inhibitors as first-line treatment, not third-line treatment, Mr. Mitchell said. The FDA should delay a withdrawal of the approval for pembrolizumab in this case and should allow a transition for those who missed out on treatment with a checkpoint inhibitor earlier in the disease course, he suggested.

“To protect the safety and well-being of patients, we have to base decisions on data,” Mr. Mitchell said. “The data don’t support maintaining the indication” for pembrolizumab.

Close split on nivolumab

In contrast to the 6-2 vote against maintaining the pembrolizumab indication, the ODAC panel split more closely, 5-4, on the question of maintaining an indication for the use as monotherapy of nivolumab in HCC.

ODAC panelist Philip C. Hoffman, MD, of the University of Chicago was among those who supported keeping the indication.

“There’s still an unmet need for second-line immunotherapy because there will always be some patients who are poor candidates for bevacizumab or who are not tolerating or responding to sorafenib,” he said.

ODAC panelist Mark A. Lewis, MD, of Intermountain Healthcare, Salt Lake City, said he voted “no” in part because he doubted that Bristol-Myers Squibb would be able to soon produce data for nivolumab that was needed to support this indication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To stay: Two more cancer indications with ‘dangling approvals’

Two more cancer indications that had been granted accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration are going to stay in place, at least for now. This was the verdict after the second day of a historic 3-day meeting (April 27-29) and follows a similar verdict from day 1.

Federal advisers so far have supported the idea of maintaining conditional approvals of some cancer indications for a number of immune checkpoint inhibitors, despite poor results in studies that were meant to confirm the benefit of these medicines for certain patients.

On the second day (April 28) of the FDA meeting, the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) supported the views of pharmaceutical companies in two more cases of what top agency staff call “dangling accelerated approvals.”

ODAC voted 10-1 in favor of maintaining the indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for the first-line treatment of cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma, pending final overall survival results from the IMvigor130 trial.

ODAC also voted 5-3 that day in favor of maintaining accelerated approval for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for first-line cisplatin- and carboplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

The FDA often follows the advice of its panels, but it is not bound to do so. If the FDA were to decide to strip the indications in question from these PD-1 medicines, such decisions would not remove these drugs from the market. The three drugs have already been approved for a number of other cancer indications.

Off-label prescribing is not uncommon in oncology, but a loss of an approved indication would affect reimbursement for these medicines, Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president of oncology clinical research at Merck (the manufacturer of pembrolizumab), told ODAC members during a discussion of the possible consequences of removing the indications in question.

“Access to those treatments may end up being substantially limited, and really the best way to ensure that there’s access is to maintain FDA approval,” Dr. Ebbinghaus said.

Another participant at the meeting asked the panel and the FDA to consider the burden on patients in paying for medicines that have not yet proved to be beneficial.

Diana Zuckerman, PhD, of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research, noted that the ODAC panel included physicians who see cancer patients.

“You’re used to trying different types of treatments in hopes that something will work,” she said. “Shouldn’t cancer patients be eligible for free treatment in clinical trials instead of paying for treatment that isn’t proven to work?”

Rapid development of PD-1 drugs

Top officials at the FDA framed the challenges with accelerated approvals for immunotherapy drugs in an April 21 article in The New England Journal of Medicine. Over the course of about 6 years, the FDA approved six of these PD-1 or PD-L1 drugs for more than 75 indications in oncology, wrote Richard Pazdur, MD, and Julia A. Beaver, MD, of the FDA.

“Development of drugs in this class occurred more rapidly than that in any other therapeutic area in history,” they wrote.

In 10 cases, the required follow-up trials did not confirm the expected benefit, and yet marketing authorization for these drugs continued, leading Dr. Pazdur and Dr. Beaver to dub these “dangling” accelerated approvals. Four of these indications were voluntarily withdrawn. For the other six indications, the FDA sought feedback from ODAC during the 3-day meeting. Over the first 2 days of the meeting, ODAC recommended that three of these cancer indications remain. Three more will be considered on the last day of the meeting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two more cancer indications that had been granted accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration are going to stay in place, at least for now. This was the verdict after the second day of a historic 3-day meeting (April 27-29) and follows a similar verdict from day 1.

Federal advisers so far have supported the idea of maintaining conditional approvals of some cancer indications for a number of immune checkpoint inhibitors, despite poor results in studies that were meant to confirm the benefit of these medicines for certain patients.

On the second day (April 28) of the FDA meeting, the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) supported the views of pharmaceutical companies in two more cases of what top agency staff call “dangling accelerated approvals.”

ODAC voted 10-1 in favor of maintaining the indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for the first-line treatment of cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma, pending final overall survival results from the IMvigor130 trial.

ODAC also voted 5-3 that day in favor of maintaining accelerated approval for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for first-line cisplatin- and carboplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

The FDA often follows the advice of its panels, but it is not bound to do so. If the FDA were to decide to strip the indications in question from these PD-1 medicines, such decisions would not remove these drugs from the market. The three drugs have already been approved for a number of other cancer indications.

Off-label prescribing is not uncommon in oncology, but a loss of an approved indication would affect reimbursement for these medicines, Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president of oncology clinical research at Merck (the manufacturer of pembrolizumab), told ODAC members during a discussion of the possible consequences of removing the indications in question.

“Access to those treatments may end up being substantially limited, and really the best way to ensure that there’s access is to maintain FDA approval,” Dr. Ebbinghaus said.

Another participant at the meeting asked the panel and the FDA to consider the burden on patients in paying for medicines that have not yet proved to be beneficial.

Diana Zuckerman, PhD, of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research, noted that the ODAC panel included physicians who see cancer patients.

“You’re used to trying different types of treatments in hopes that something will work,” she said. “Shouldn’t cancer patients be eligible for free treatment in clinical trials instead of paying for treatment that isn’t proven to work?”

Rapid development of PD-1 drugs

Top officials at the FDA framed the challenges with accelerated approvals for immunotherapy drugs in an April 21 article in The New England Journal of Medicine. Over the course of about 6 years, the FDA approved six of these PD-1 or PD-L1 drugs for more than 75 indications in oncology, wrote Richard Pazdur, MD, and Julia A. Beaver, MD, of the FDA.

“Development of drugs in this class occurred more rapidly than that in any other therapeutic area in history,” they wrote.

In 10 cases, the required follow-up trials did not confirm the expected benefit, and yet marketing authorization for these drugs continued, leading Dr. Pazdur and Dr. Beaver to dub these “dangling” accelerated approvals. Four of these indications were voluntarily withdrawn. For the other six indications, the FDA sought feedback from ODAC during the 3-day meeting. Over the first 2 days of the meeting, ODAC recommended that three of these cancer indications remain. Three more will be considered on the last day of the meeting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two more cancer indications that had been granted accelerated approval by the Food and Drug Administration are going to stay in place, at least for now. This was the verdict after the second day of a historic 3-day meeting (April 27-29) and follows a similar verdict from day 1.

Federal advisers so far have supported the idea of maintaining conditional approvals of some cancer indications for a number of immune checkpoint inhibitors, despite poor results in studies that were meant to confirm the benefit of these medicines for certain patients.

On the second day (April 28) of the FDA meeting, the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) supported the views of pharmaceutical companies in two more cases of what top agency staff call “dangling accelerated approvals.”

ODAC voted 10-1 in favor of maintaining the indication for atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for the first-line treatment of cisplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma, pending final overall survival results from the IMvigor130 trial.

ODAC also voted 5-3 that day in favor of maintaining accelerated approval for pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for first-line cisplatin- and carboplatin-ineligible patients with advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

The FDA often follows the advice of its panels, but it is not bound to do so. If the FDA were to decide to strip the indications in question from these PD-1 medicines, such decisions would not remove these drugs from the market. The three drugs have already been approved for a number of other cancer indications.

Off-label prescribing is not uncommon in oncology, but a loss of an approved indication would affect reimbursement for these medicines, Scot Ebbinghaus, MD, vice president of oncology clinical research at Merck (the manufacturer of pembrolizumab), told ODAC members during a discussion of the possible consequences of removing the indications in question.

“Access to those treatments may end up being substantially limited, and really the best way to ensure that there’s access is to maintain FDA approval,” Dr. Ebbinghaus said.

Another participant at the meeting asked the panel and the FDA to consider the burden on patients in paying for medicines that have not yet proved to be beneficial.

Diana Zuckerman, PhD, of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research, noted that the ODAC panel included physicians who see cancer patients.

“You’re used to trying different types of treatments in hopes that something will work,” she said. “Shouldn’t cancer patients be eligible for free treatment in clinical trials instead of paying for treatment that isn’t proven to work?”

Rapid development of PD-1 drugs

Top officials at the FDA framed the challenges with accelerated approvals for immunotherapy drugs in an April 21 article in The New England Journal of Medicine. Over the course of about 6 years, the FDA approved six of these PD-1 or PD-L1 drugs for more than 75 indications in oncology, wrote Richard Pazdur, MD, and Julia A. Beaver, MD, of the FDA.

“Development of drugs in this class occurred more rapidly than that in any other therapeutic area in history,” they wrote.

In 10 cases, the required follow-up trials did not confirm the expected benefit, and yet marketing authorization for these drugs continued, leading Dr. Pazdur and Dr. Beaver to dub these “dangling” accelerated approvals. Four of these indications were voluntarily withdrawn. For the other six indications, the FDA sought feedback from ODAC during the 3-day meeting. Over the first 2 days of the meeting, ODAC recommended that three of these cancer indications remain. Three more will be considered on the last day of the meeting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

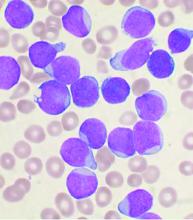

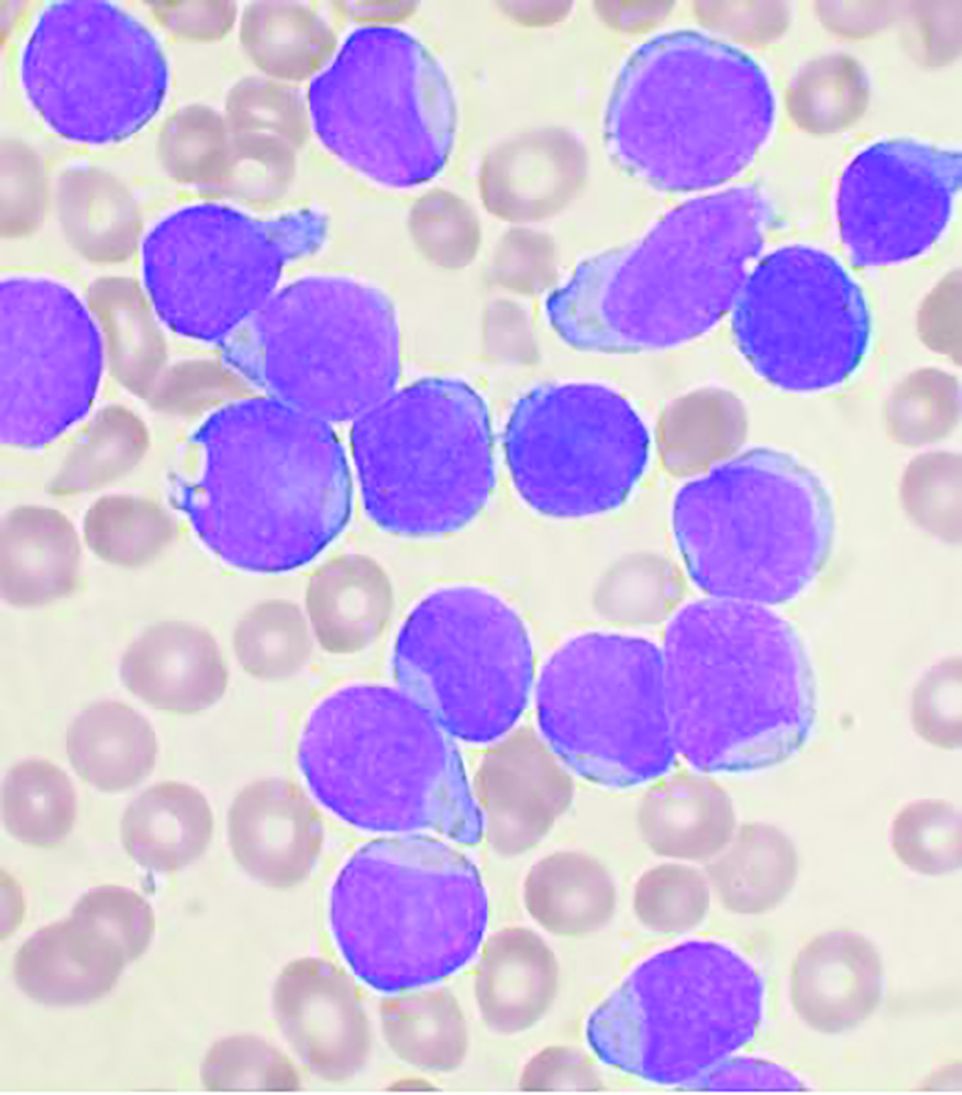

Allo-HSCT plus monoclonal antibody treatment can improve survival in patients with r/r B-ALL

The use of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) can improve survival in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative remission patients with relapsed/refractory (r/r) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) after the start of monoclonal antibody treatment, according to the results of a landmark analysis presented at the virtual meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Previous studies have indicated that allo-HSCT improves the results of treatment in r/r B-ALL patients, compared with chemotherapy alone. In addition, it has been found that the monoclonal antibodies (Mab), anti-CD19-blinatumomab and anti-CD22-inotuzumab ozogamicin, induced remission in a significant proportion of such patients.

To determine if the use of allo-HSCT improves the outcome of patients in MRD-negative remission with or without Mab treatment, researchers performed a landmark analysis of 110 patients who achieved MRD-negative status after Mab treatment. The analysis examined results at 2, 4, and 6 months subsequent to the initiation of Mab treatment, according to poster presentation by Inna V. Markova, MD, and colleagues at Pavlov University, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation.

Study details

The researchers included 110 patients who achieved MRD-negative status outside of clinical trials at a single institution in the analysis. Forty of the patients (36%) were children and 70 (64%) were adults. The median age for all patients was 23 years and the median follow up was 24 months. Fifty-seven (52%) and 53 (48%) patients received Mab for hematological relapse and persistent measurable residual disease or for molecular relapse, respectively. Therapy with Mab alone without subsequent allo-HSCT was used in 36 (31%) patients (30 received blinatumomab and 6 received inotuzumab ozogamicin). A total of 74 (69%) patients received allo-HSCT from a matched related or unrelated donor (MD-HSCT, n = 38) or haploidentical donor (Haplo-HSCT, n = 36). All patients received posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCY)–based graft-versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. Landmark analysis was performed at 2, 4, and 6 months after Mab therapy initiation to determine the effect of allo-HSCT on the outcome and the optimal timing of HSCT. Overall survival and disease-free survival (DFS) were used as outcomes.

Promising results

No significant differences between the MD-HSCT, Mab alone, and Haplo-HSCT groups were observed in 2-month landmark analysis (P = .4 for OS and P =.65 for DFS). However, the 4-month landmark analysis demonstrated superior overall survival and DFS in patients after MD-HSCT, but not Haplo-HSCT, compared with Mab alone: 2-year OS was 75%, 50%, and 27,7% (P = .032) and DFS was 53.5%, 51.3%, and 16.6% (P = .02) for MD-HSCT, Mab alone and Haplo-HSCT groups, respectively. In addition, 6-month analysis showed that there was no benefit from subsequent transplantation, according to the authors, with regard to overall survival (P = .11).

“Our study demonstrated that at least MD-HSCT with PTCY platform improves survival in MRD-negative remission if performed during the first 4 months after Mab initiation. Haplo-HSCT or MD-HSCT beyond 4 months are not associated with improved outcomes in this groups of patients,” the researchers concluded.

The researchers reported they had no conflicts of interest to declare.

The use of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) can improve survival in minimal residual disease (MRD)–negative remission patients with relapsed/refractory (r/r) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) after the start of monoclonal antibody treatment, according to the results of a landmark analysis presented at the virtual meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Previous studies have indicated that allo-HSCT improves the results of treatment in r/r B-ALL patients, compared with chemotherapy alone. In addition, it has been found that the monoclonal antibodies (Mab), anti-CD19-blinatumomab and anti-CD22-inotuzumab ozogamicin, induced remission in a significant proportion of such patients.

To determine if the use of allo-HSCT improves the outcome of patients in MRD-negative remission with or without Mab treatment, researchers performed a landmark analysis of 110 patients who achieved MRD-negative status after Mab treatment. The analysis examined results at 2, 4, and 6 months subsequent to the initiation of Mab treatment, according to poster presentation by Inna V. Markova, MD, and colleagues at Pavlov University, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation.

Study details

The researchers included 110 patients who achieved MRD-negative status outside of clinical trials at a single institution in the analysis. Forty of the patients (36%) were children and 70 (64%) were adults. The median age for all patients was 23 years and the median follow up was 24 months. Fifty-seven (52%) and 53 (48%) patients received Mab for hematological relapse and persistent measurable residual disease or for molecular relapse, respectively. Therapy with Mab alone without subsequent allo-HSCT was used in 36 (31%) patients (30 received blinatumomab and 6 received inotuzumab ozogamicin). A total of 74 (69%) patients received allo-HSCT from a matched related or unrelated donor (MD-HSCT, n = 38) or haploidentical donor (Haplo-HSCT, n = 36). All patients received posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PTCY)–based graft-versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis. Landmark analysis was performed at 2, 4, and 6 months after Mab therapy initiation to determine the effect of allo-HSCT on the outcome and the optimal timing of HSCT. Overall survival and disease-free survival (DFS) were used as outcomes.

Promising results

No significant differences between the MD-HSCT, Mab alone, and Haplo-HSCT groups were observed in 2-month landmark analysis (P = .4 for OS and P =.65 for DFS). However, the 4-month landmark analysis demonstrated superior overall survival and DFS in patients after MD-HSCT, but not Haplo-HSCT, compared with Mab alone: 2-year OS was 75%, 50%, and 27,7% (P = .032) and DFS was 53.5%, 51.3%, and 16.6% (P = .02) for MD-HSCT, Mab alone and Haplo-HSCT groups, respectively. In addition, 6-month analysis showed that there was no benefit from subsequent transplantation, according to the authors, with regard to overall survival (P = .11).

“Our study demonstrated that at least MD-HSCT with PTCY platform improves survival in MRD-negative remission if performed during the first 4 months after Mab initiation. Haplo-HSCT or MD-HSCT beyond 4 months are not associated with improved outcomes in this groups of patients,” the researchers concluded.