User login

Hypermucoviscous K pneumoniae Shows Reduced Drug Resistance

TOPLINE:

Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae (hmKp) strains demonstrate a significantly lower prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production and slightly lower carbapenem resistance than non-hmKp strains, according to a recent meta-analysis of 2049 clinical isolates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis to assess the prevalence of ESBL-producing strains and carbapenem-resistant strains among the hmKp and non-hmKp clinical isolates.

- They included 15 studies published between 2014 and 2023, with 2049 clinical isolates of K pneumoniae identified using a string test to distinguish hypermucoviscous from non-hypermucoviscous strains.

- These studies spanned across four continents: Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

- The primary outcome was the prevalence of ESBL-producing and carbapenem-resistant strains, determined through antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

TAKEAWAY:

- The hmKp strains were associated with a significantly lower prevalence of ESBL-producing strains than non-hmKp strains (pooled odds ratio [OR], 0.26; P = .003).

- Similarly, hmKp strains were associated with a slightly lower prevalence of carbapenem-resistant strains than non-hmKp strains (pooled OR, 0.63; P = .038).

IN PRACTICE:

“Therapeutic options for CRKP [carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae] infections are extremely limited due to the scarcity of effective antibacterial drugs. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the risks posed by CRKP strains when administering treatment to patients with hmKp infections and a history of the aforementioned risk factors,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Hiroki Namikawa, Department of Medical Education and General Practice, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University, Japan. It was published online on December 16, 2024, in Emerging Microbes & Infections.

LIMITATIONS:

Only three databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane Library) were searched for identifying studies, potentially missing relevant studies from other sources. Furthermore, only articles published in English were included, which may have restricted the scope of analysis. Additionally, geographical distribution was predominantly limited to Asia, limiting the global applicability of the results.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were mentioned, and no conflicts of interest were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae (hmKp) strains demonstrate a significantly lower prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production and slightly lower carbapenem resistance than non-hmKp strains, according to a recent meta-analysis of 2049 clinical isolates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis to assess the prevalence of ESBL-producing strains and carbapenem-resistant strains among the hmKp and non-hmKp clinical isolates.

- They included 15 studies published between 2014 and 2023, with 2049 clinical isolates of K pneumoniae identified using a string test to distinguish hypermucoviscous from non-hypermucoviscous strains.

- These studies spanned across four continents: Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

- The primary outcome was the prevalence of ESBL-producing and carbapenem-resistant strains, determined through antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

TAKEAWAY:

- The hmKp strains were associated with a significantly lower prevalence of ESBL-producing strains than non-hmKp strains (pooled odds ratio [OR], 0.26; P = .003).

- Similarly, hmKp strains were associated with a slightly lower prevalence of carbapenem-resistant strains than non-hmKp strains (pooled OR, 0.63; P = .038).

IN PRACTICE:

“Therapeutic options for CRKP [carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae] infections are extremely limited due to the scarcity of effective antibacterial drugs. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the risks posed by CRKP strains when administering treatment to patients with hmKp infections and a history of the aforementioned risk factors,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Hiroki Namikawa, Department of Medical Education and General Practice, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University, Japan. It was published online on December 16, 2024, in Emerging Microbes & Infections.

LIMITATIONS:

Only three databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane Library) were searched for identifying studies, potentially missing relevant studies from other sources. Furthermore, only articles published in English were included, which may have restricted the scope of analysis. Additionally, geographical distribution was predominantly limited to Asia, limiting the global applicability of the results.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were mentioned, and no conflicts of interest were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae (hmKp) strains demonstrate a significantly lower prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production and slightly lower carbapenem resistance than non-hmKp strains, according to a recent meta-analysis of 2049 clinical isolates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a meta-analysis to assess the prevalence of ESBL-producing strains and carbapenem-resistant strains among the hmKp and non-hmKp clinical isolates.

- They included 15 studies published between 2014 and 2023, with 2049 clinical isolates of K pneumoniae identified using a string test to distinguish hypermucoviscous from non-hypermucoviscous strains.

- These studies spanned across four continents: Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America.

- The primary outcome was the prevalence of ESBL-producing and carbapenem-resistant strains, determined through antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

TAKEAWAY:

- The hmKp strains were associated with a significantly lower prevalence of ESBL-producing strains than non-hmKp strains (pooled odds ratio [OR], 0.26; P = .003).

- Similarly, hmKp strains were associated with a slightly lower prevalence of carbapenem-resistant strains than non-hmKp strains (pooled OR, 0.63; P = .038).

IN PRACTICE:

“Therapeutic options for CRKP [carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae] infections are extremely limited due to the scarcity of effective antibacterial drugs. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the risks posed by CRKP strains when administering treatment to patients with hmKp infections and a history of the aforementioned risk factors,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Hiroki Namikawa, Department of Medical Education and General Practice, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka Metropolitan University, Japan. It was published online on December 16, 2024, in Emerging Microbes & Infections.

LIMITATIONS:

Only three databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane Library) were searched for identifying studies, potentially missing relevant studies from other sources. Furthermore, only articles published in English were included, which may have restricted the scope of analysis. Additionally, geographical distribution was predominantly limited to Asia, limiting the global applicability of the results.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were mentioned, and no conflicts of interest were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First Human Bird Flu Death Confirmed in US; Overall Risk Remains Low

The first human patient in the United States with a confirmed case of avian influenza has died, according to a press release from the Louisiana Department of Health. The individual was older than 65 years and had underlying medical conditions and remains the only known human case in the state.

The patient contracted highly pathogenic avian influenza, also known as H5N1, through exposure to wild birds and a noncommercial backyard flock, according to the release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted genetic sequencing of specimens of the virus collected from the Louisiana patient. The agency compared the sequences with sequences from dairy cows, wild birds, and poultry in various areas of the United States that were infected with the H5N1 virus.

The Louisiana patient was infected with the D1.1 genotype of the H5N1 virus. Although D1.1 is related to other D1.1 viruses found in recent human cases in Washington State and British Columbia, Canada, it is distinct from the widely spreading B3.13 genotype that has caused H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cows, poultry, and other animals and has been linked to sporadic human cases in the United States, according to the CDC.

Despite evidence of some changes in the virus between the Louisiana patient and samples from poultry on the patient’s property, “these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection,” according to the CDC. The CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health are conducting additional sequencing to facilitate further analysis.

In the meantime, the risk to the general public for H5N1 remains low, but individuals who work with or have recreational exposure to birds, poultry, or cows remain at increased risk.

The CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health advise individuals to reduce the risk for H5N1 exposure by avoiding direct contact with wild birds or other animals infected or possibly infected with the virus, avoiding any contact with dead animals, and keeping pets away from sick or dead animals and their feces. Additional safety measures include avoiding uncooked food products such as unpasteurized raw milk or cheese from animals with suspected or confirmed infections and reporting sick or dead birds or animals to the US Department of Agriculture by calling 1-866-536-7593 or the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry Diagnostic Lab by calling 318-927-3441.

The CDC advises clinicians to consider H5N1 in patients presenting with conjunctivitis or signs of acute respiratory illness and a history of high-risk exposure, including handling sick or dead animals, notably birds and livestock, within 10 days before the onset of symptoms. Other risk factors include consuming uncooked or undercooked food, direct contact with areas contaminated with feces, direct contact with unpasteurized milk or other dairy products or with parts of potentially infected animals, and prolonged exposure to infected animals in a confined space.

Clinical symptoms also may include gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhea, as well as fatigue, arthralgia, and headache. Patients with more severe H5N1 may experience shortness of breath, altered mental state, and seizures, and serious complications of the virus include pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiorgan failure, and sepsis, according to the CDC.

Clinicians who suspect H5N1 cases should contact their local public health departments. The CDC offers additional advice on evaluating and managing patients with novel influenza A viruses.

A Clinician’s Take

“Some symptoms of avian flu include fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, fatigue, body aches or eye redness or irritation,” Shirin A. Mazumder, MD, associate professor and infectious disease specialist at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, said in an interview. “The timing to the development of symptoms after exposure is typically within 10 days. Avian influenza should be considered when individuals develop symptoms with a relevant exposure history,” she said.

Whenever possible, avoidance of sick or dead birds and other animals is ideal, but for those who must have contact with sick or dead birds, poultry, or other animals, personal protective equipment (PPE) including a respirator, goggles, and disposable gloves is recommended, said Mazumder.

“For those working in high-exposure settings, additional PPE including boots or boot covers, hair cover, and fluid-resistant coveralls are recommended,” she said. “Other protective measures include avoiding touching surfaces or materials contaminated with feces, mucus, and saliva from infected animals and avoid[ing] the consumption of raw milk, raw milk products, and undercooked meat from infected animals,” she added.

Hunters handling wild game should dress birds in the field, practice good hand hygiene, and use a respirator or well-fitting mask and gloves when handling the animals to help prevent disease, said Mazumder.

In addition, those working with confirmed or suspected H5N1 cases should monitor themselves for symptoms, said Mazumder. “Those who become ill within 10 days of exposure to an infected animal or source should isolate from household members and avoid going to work or school until infection is excluded. It is important to reach out to a healthcare professional if you think you may have been exposed or if you think you are infected,” she said.

There is no currently available vaccine for H5N1 infection, but oseltamivir can be used for chemoprophylaxis and treatment, said Mazumder. “The seasonal flu vaccine does not protect against avian influenza; however, it is still important to ensure that you are up to date on the latest flu vaccine to prevent the possibility of a coinfection with seasonal flu and avian flu,” she emphasized.

More research is needed to better understand how the influenza virus is transmitted, said Mazumder. “The potential for the virus to evolve and mutate, and how it affects different hosts, are all factors that can impact public health decisions,” she said. “In addition, further research into finding a vaccine and improving surveillance methods are necessary for disease prevention,” she said.

Mazumder had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The first human patient in the United States with a confirmed case of avian influenza has died, according to a press release from the Louisiana Department of Health. The individual was older than 65 years and had underlying medical conditions and remains the only known human case in the state.

The patient contracted highly pathogenic avian influenza, also known as H5N1, through exposure to wild birds and a noncommercial backyard flock, according to the release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted genetic sequencing of specimens of the virus collected from the Louisiana patient. The agency compared the sequences with sequences from dairy cows, wild birds, and poultry in various areas of the United States that were infected with the H5N1 virus.

The Louisiana patient was infected with the D1.1 genotype of the H5N1 virus. Although D1.1 is related to other D1.1 viruses found in recent human cases in Washington State and British Columbia, Canada, it is distinct from the widely spreading B3.13 genotype that has caused H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cows, poultry, and other animals and has been linked to sporadic human cases in the United States, according to the CDC.

Despite evidence of some changes in the virus between the Louisiana patient and samples from poultry on the patient’s property, “these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection,” according to the CDC. The CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health are conducting additional sequencing to facilitate further analysis.

In the meantime, the risk to the general public for H5N1 remains low, but individuals who work with or have recreational exposure to birds, poultry, or cows remain at increased risk.

The CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health advise individuals to reduce the risk for H5N1 exposure by avoiding direct contact with wild birds or other animals infected or possibly infected with the virus, avoiding any contact with dead animals, and keeping pets away from sick or dead animals and their feces. Additional safety measures include avoiding uncooked food products such as unpasteurized raw milk or cheese from animals with suspected or confirmed infections and reporting sick or dead birds or animals to the US Department of Agriculture by calling 1-866-536-7593 or the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry Diagnostic Lab by calling 318-927-3441.

The CDC advises clinicians to consider H5N1 in patients presenting with conjunctivitis or signs of acute respiratory illness and a history of high-risk exposure, including handling sick or dead animals, notably birds and livestock, within 10 days before the onset of symptoms. Other risk factors include consuming uncooked or undercooked food, direct contact with areas contaminated with feces, direct contact with unpasteurized milk or other dairy products or with parts of potentially infected animals, and prolonged exposure to infected animals in a confined space.

Clinical symptoms also may include gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhea, as well as fatigue, arthralgia, and headache. Patients with more severe H5N1 may experience shortness of breath, altered mental state, and seizures, and serious complications of the virus include pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiorgan failure, and sepsis, according to the CDC.

Clinicians who suspect H5N1 cases should contact their local public health departments. The CDC offers additional advice on evaluating and managing patients with novel influenza A viruses.

A Clinician’s Take

“Some symptoms of avian flu include fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, fatigue, body aches or eye redness or irritation,” Shirin A. Mazumder, MD, associate professor and infectious disease specialist at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, said in an interview. “The timing to the development of symptoms after exposure is typically within 10 days. Avian influenza should be considered when individuals develop symptoms with a relevant exposure history,” she said.

Whenever possible, avoidance of sick or dead birds and other animals is ideal, but for those who must have contact with sick or dead birds, poultry, or other animals, personal protective equipment (PPE) including a respirator, goggles, and disposable gloves is recommended, said Mazumder.

“For those working in high-exposure settings, additional PPE including boots or boot covers, hair cover, and fluid-resistant coveralls are recommended,” she said. “Other protective measures include avoiding touching surfaces or materials contaminated with feces, mucus, and saliva from infected animals and avoid[ing] the consumption of raw milk, raw milk products, and undercooked meat from infected animals,” she added.

Hunters handling wild game should dress birds in the field, practice good hand hygiene, and use a respirator or well-fitting mask and gloves when handling the animals to help prevent disease, said Mazumder.

In addition, those working with confirmed or suspected H5N1 cases should monitor themselves for symptoms, said Mazumder. “Those who become ill within 10 days of exposure to an infected animal or source should isolate from household members and avoid going to work or school until infection is excluded. It is important to reach out to a healthcare professional if you think you may have been exposed or if you think you are infected,” she said.

There is no currently available vaccine for H5N1 infection, but oseltamivir can be used for chemoprophylaxis and treatment, said Mazumder. “The seasonal flu vaccine does not protect against avian influenza; however, it is still important to ensure that you are up to date on the latest flu vaccine to prevent the possibility of a coinfection with seasonal flu and avian flu,” she emphasized.

More research is needed to better understand how the influenza virus is transmitted, said Mazumder. “The potential for the virus to evolve and mutate, and how it affects different hosts, are all factors that can impact public health decisions,” she said. “In addition, further research into finding a vaccine and improving surveillance methods are necessary for disease prevention,” she said.

Mazumder had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The first human patient in the United States with a confirmed case of avian influenza has died, according to a press release from the Louisiana Department of Health. The individual was older than 65 years and had underlying medical conditions and remains the only known human case in the state.

The patient contracted highly pathogenic avian influenza, also known as H5N1, through exposure to wild birds and a noncommercial backyard flock, according to the release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted genetic sequencing of specimens of the virus collected from the Louisiana patient. The agency compared the sequences with sequences from dairy cows, wild birds, and poultry in various areas of the United States that were infected with the H5N1 virus.

The Louisiana patient was infected with the D1.1 genotype of the H5N1 virus. Although D1.1 is related to other D1.1 viruses found in recent human cases in Washington State and British Columbia, Canada, it is distinct from the widely spreading B3.13 genotype that has caused H5N1 outbreaks in dairy cows, poultry, and other animals and has been linked to sporadic human cases in the United States, according to the CDC.

Despite evidence of some changes in the virus between the Louisiana patient and samples from poultry on the patient’s property, “these changes would be more concerning if found in animal hosts or in early stages of infection,” according to the CDC. The CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health are conducting additional sequencing to facilitate further analysis.

In the meantime, the risk to the general public for H5N1 remains low, but individuals who work with or have recreational exposure to birds, poultry, or cows remain at increased risk.

The CDC and the Louisiana Department of Health advise individuals to reduce the risk for H5N1 exposure by avoiding direct contact with wild birds or other animals infected or possibly infected with the virus, avoiding any contact with dead animals, and keeping pets away from sick or dead animals and their feces. Additional safety measures include avoiding uncooked food products such as unpasteurized raw milk or cheese from animals with suspected or confirmed infections and reporting sick or dead birds or animals to the US Department of Agriculture by calling 1-866-536-7593 or the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry Diagnostic Lab by calling 318-927-3441.

The CDC advises clinicians to consider H5N1 in patients presenting with conjunctivitis or signs of acute respiratory illness and a history of high-risk exposure, including handling sick or dead animals, notably birds and livestock, within 10 days before the onset of symptoms. Other risk factors include consuming uncooked or undercooked food, direct contact with areas contaminated with feces, direct contact with unpasteurized milk or other dairy products or with parts of potentially infected animals, and prolonged exposure to infected animals in a confined space.

Clinical symptoms also may include gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhea, as well as fatigue, arthralgia, and headache. Patients with more severe H5N1 may experience shortness of breath, altered mental state, and seizures, and serious complications of the virus include pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multiorgan failure, and sepsis, according to the CDC.

Clinicians who suspect H5N1 cases should contact their local public health departments. The CDC offers additional advice on evaluating and managing patients with novel influenza A viruses.

A Clinician’s Take

“Some symptoms of avian flu include fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, fatigue, body aches or eye redness or irritation,” Shirin A. Mazumder, MD, associate professor and infectious disease specialist at The University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, said in an interview. “The timing to the development of symptoms after exposure is typically within 10 days. Avian influenza should be considered when individuals develop symptoms with a relevant exposure history,” she said.

Whenever possible, avoidance of sick or dead birds and other animals is ideal, but for those who must have contact with sick or dead birds, poultry, or other animals, personal protective equipment (PPE) including a respirator, goggles, and disposable gloves is recommended, said Mazumder.

“For those working in high-exposure settings, additional PPE including boots or boot covers, hair cover, and fluid-resistant coveralls are recommended,” she said. “Other protective measures include avoiding touching surfaces or materials contaminated with feces, mucus, and saliva from infected animals and avoid[ing] the consumption of raw milk, raw milk products, and undercooked meat from infected animals,” she added.

Hunters handling wild game should dress birds in the field, practice good hand hygiene, and use a respirator or well-fitting mask and gloves when handling the animals to help prevent disease, said Mazumder.

In addition, those working with confirmed or suspected H5N1 cases should monitor themselves for symptoms, said Mazumder. “Those who become ill within 10 days of exposure to an infected animal or source should isolate from household members and avoid going to work or school until infection is excluded. It is important to reach out to a healthcare professional if you think you may have been exposed or if you think you are infected,” she said.

There is no currently available vaccine for H5N1 infection, but oseltamivir can be used for chemoprophylaxis and treatment, said Mazumder. “The seasonal flu vaccine does not protect against avian influenza; however, it is still important to ensure that you are up to date on the latest flu vaccine to prevent the possibility of a coinfection with seasonal flu and avian flu,” she emphasized.

More research is needed to better understand how the influenza virus is transmitted, said Mazumder. “The potential for the virus to evolve and mutate, and how it affects different hosts, are all factors that can impact public health decisions,” she said. “In addition, further research into finding a vaccine and improving surveillance methods are necessary for disease prevention,” she said.

Mazumder had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis Diagnosis

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

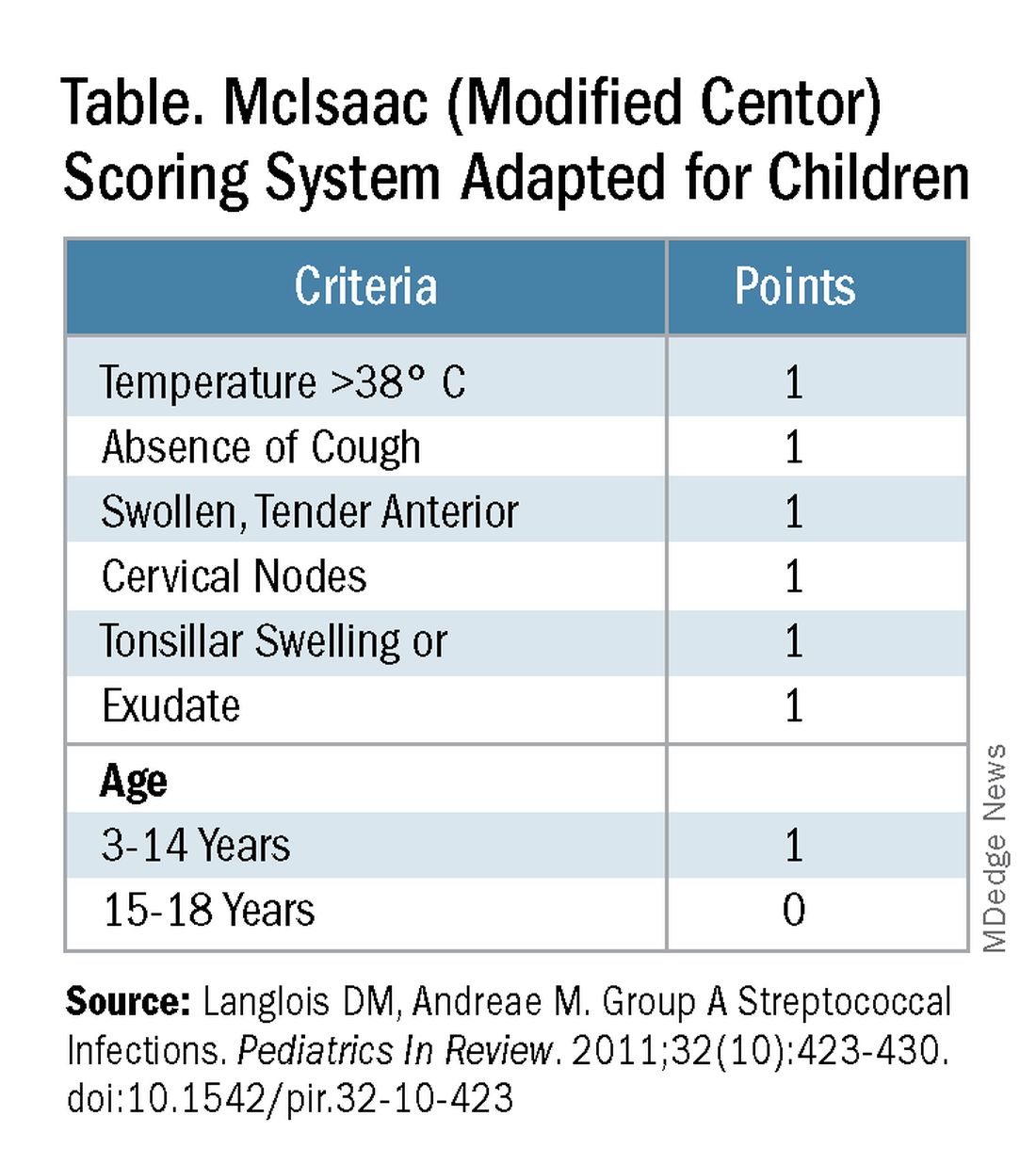

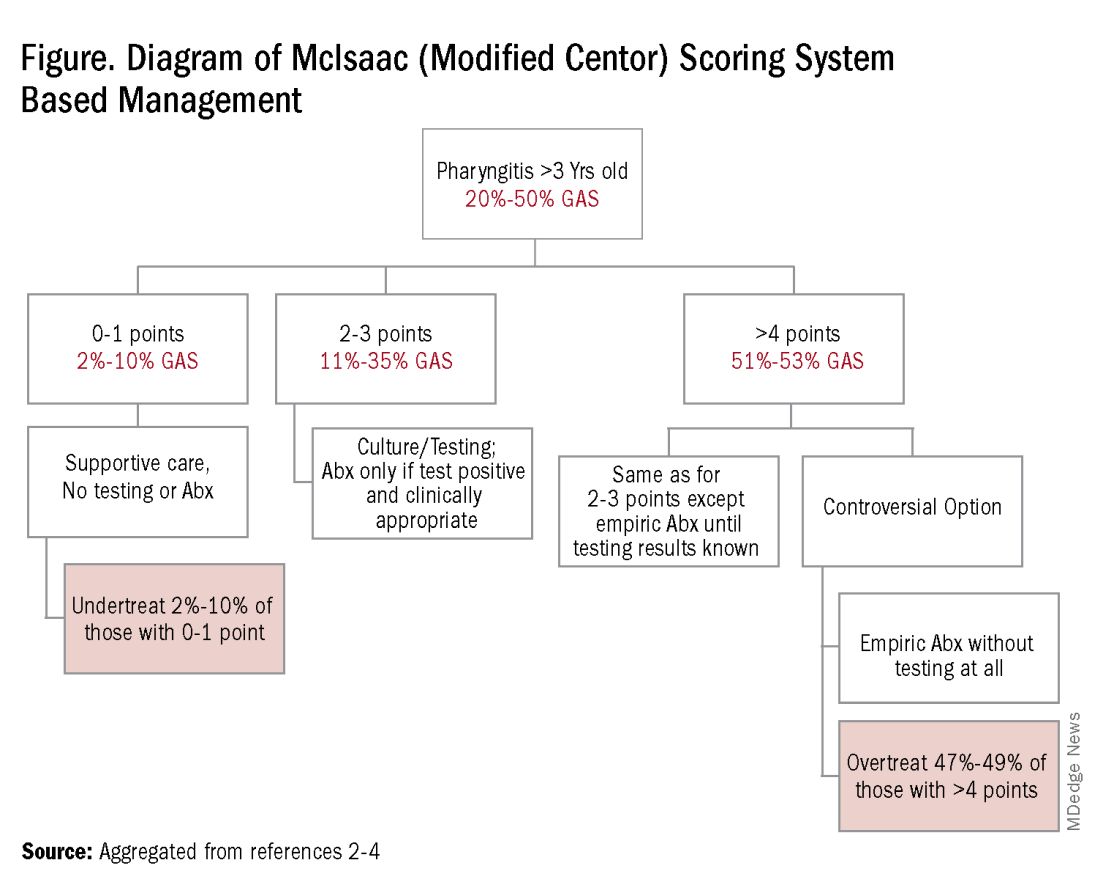

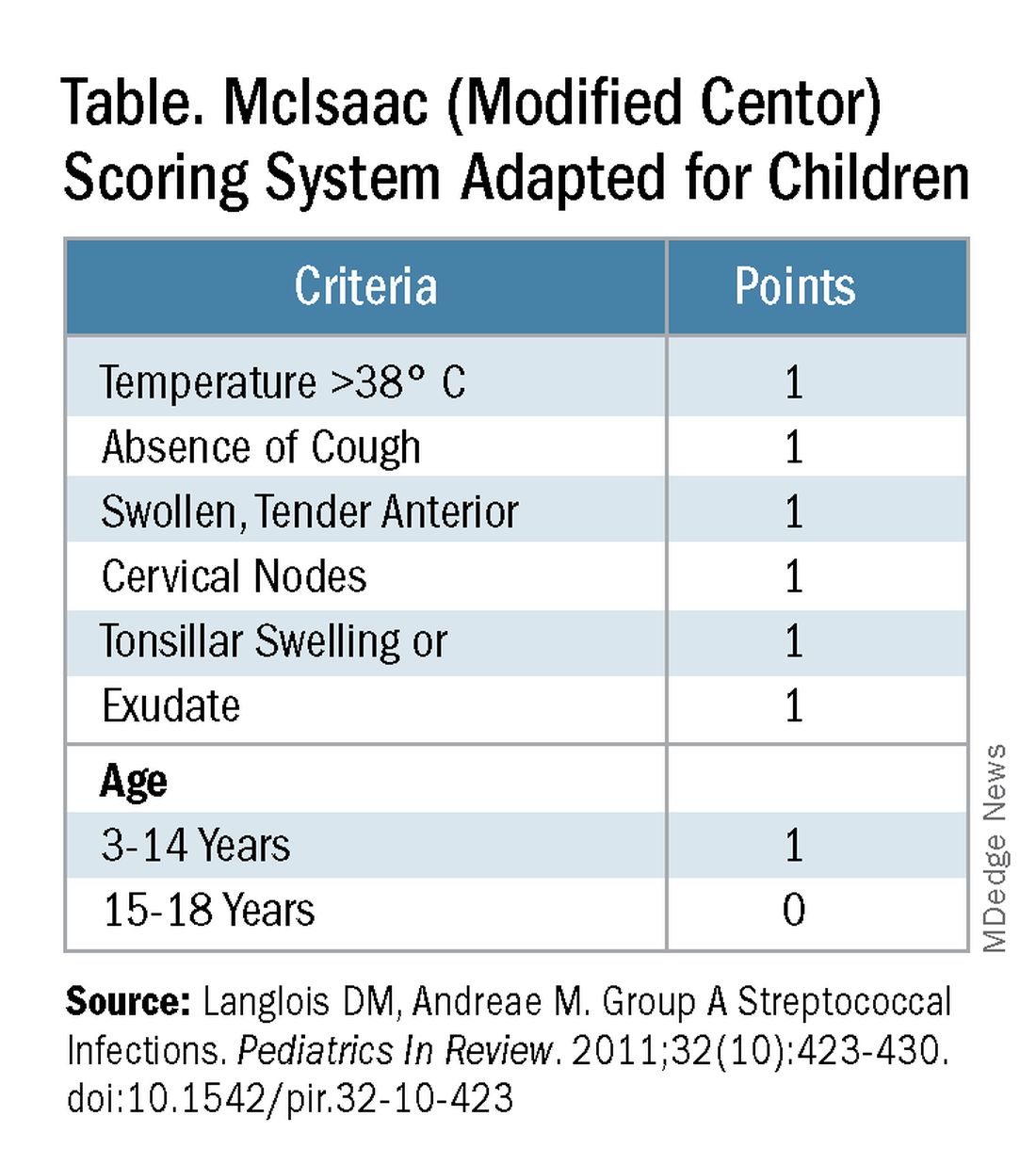

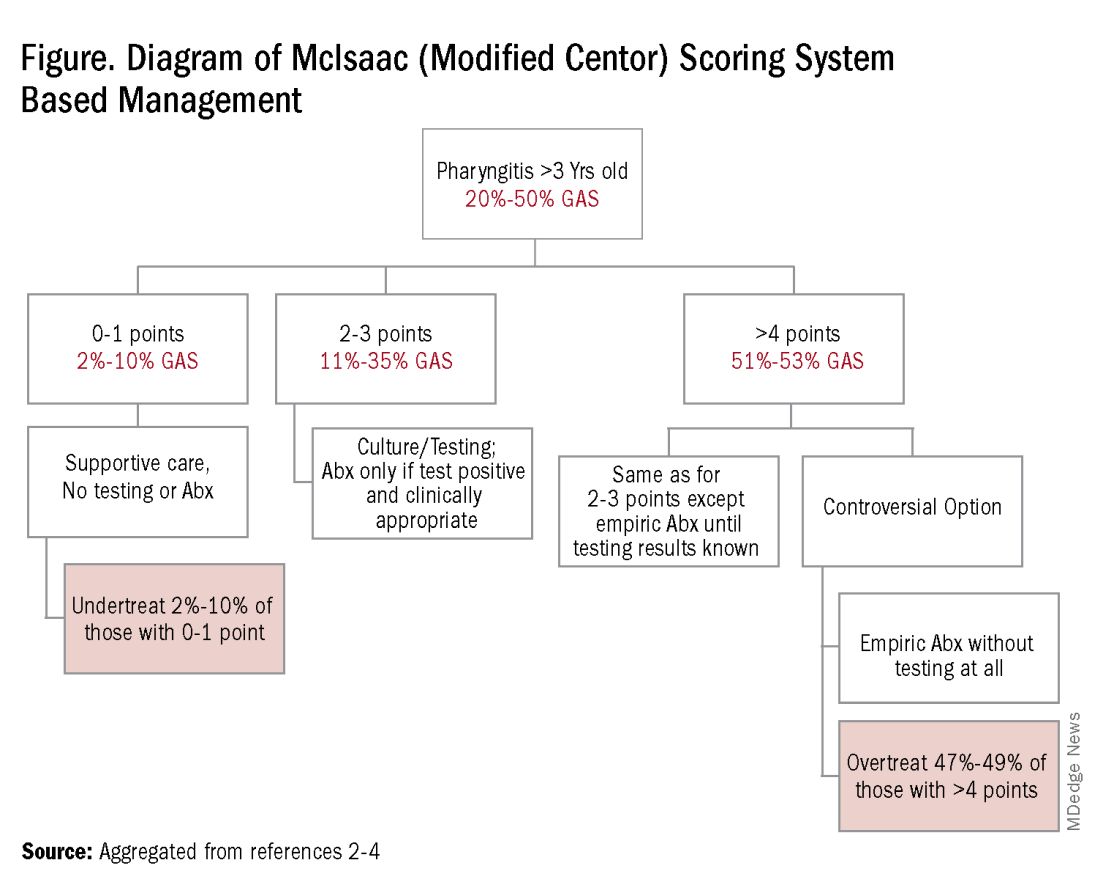

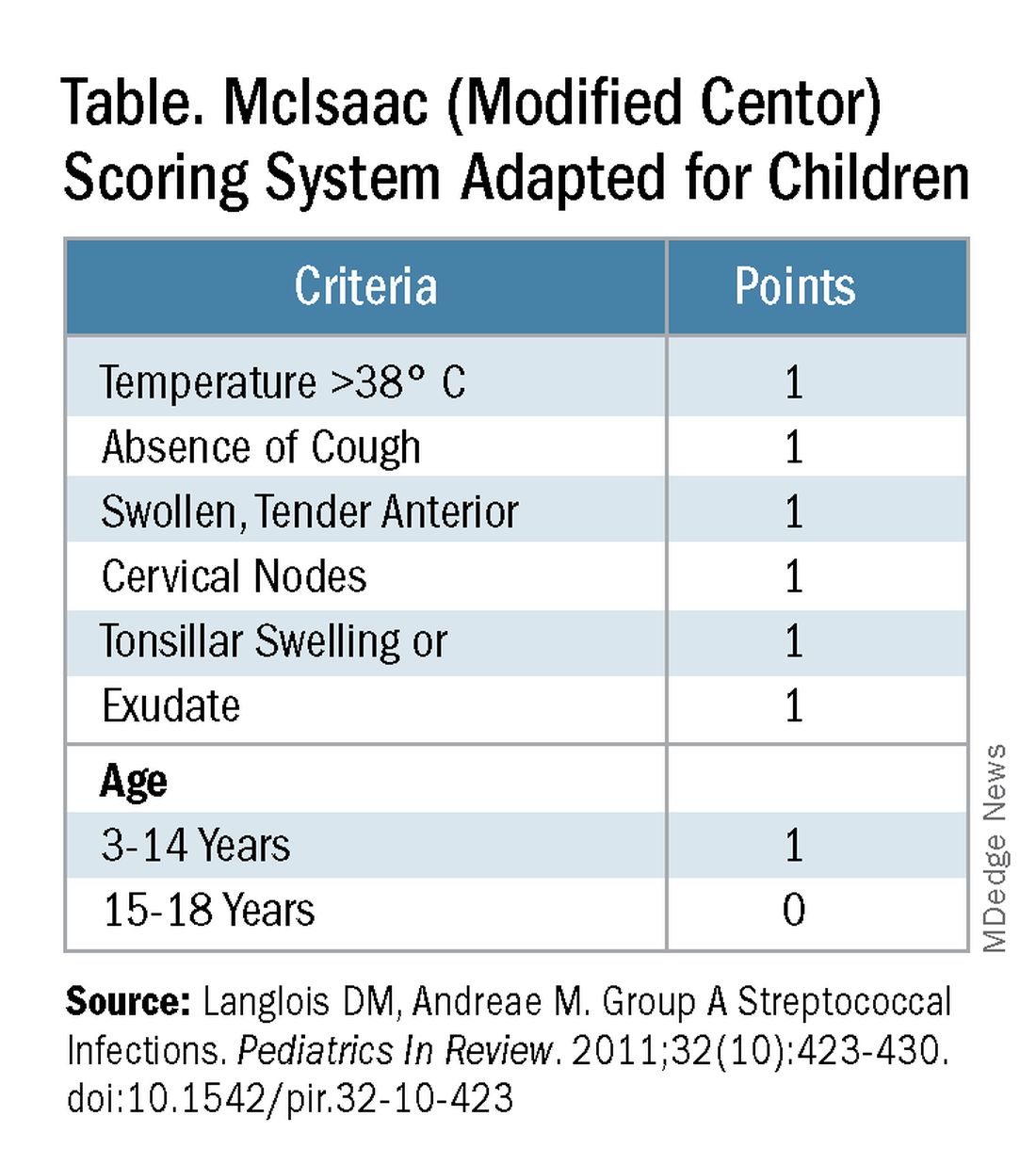

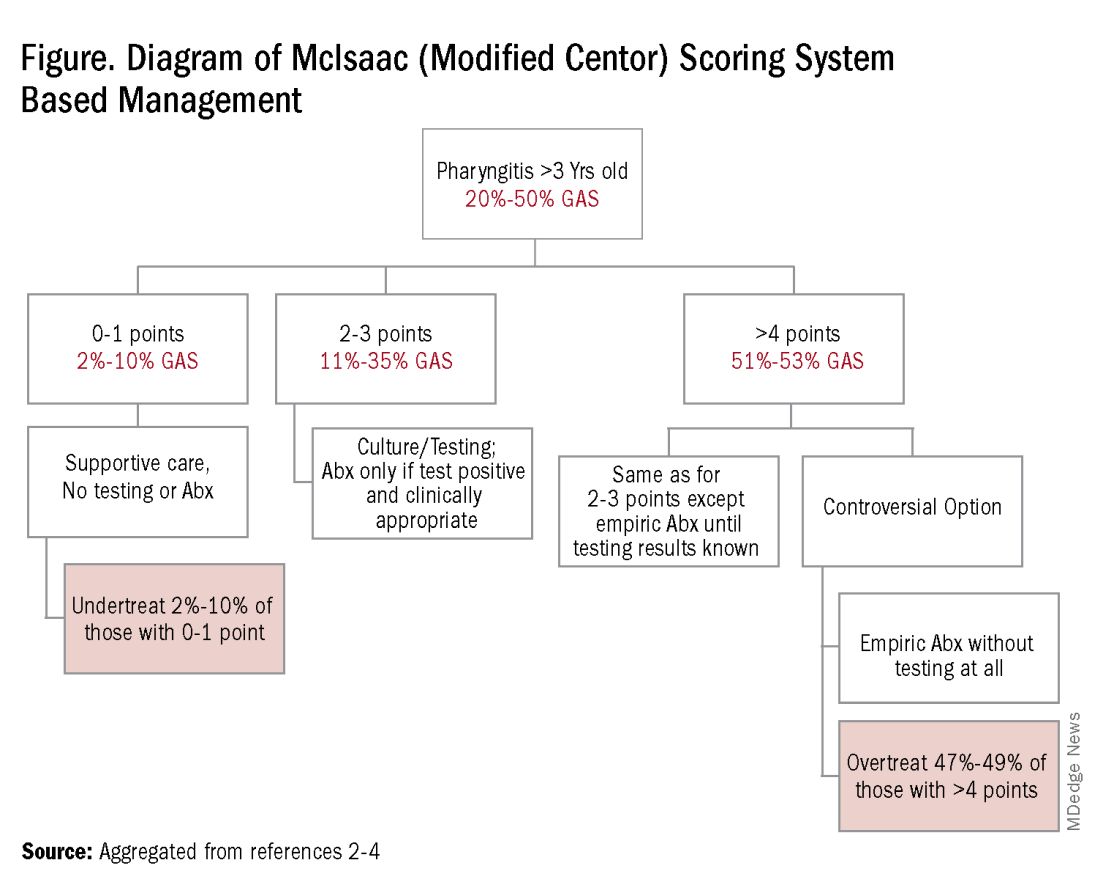

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.

5. Shulman ST et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

6. Rao A et al. Diagnosis and Antibiotic Treatment of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children in a Primary Care Setting: Impact of Point-of-Care Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Jan 16;19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1393-y.

7. Norton LE et al. Improving Guideline-Based Streptococcal Pharyngitis Testing: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatrics. 2018 Jul;142(1):e20172033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2033.

8. MD+ Calc website. Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis.

9. Langlois DM, Andreae M. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Oct;32(10):423-9; quiz 430. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-10-423.

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.

5. Shulman ST et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

6. Rao A et al. Diagnosis and Antibiotic Treatment of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children in a Primary Care Setting: Impact of Point-of-Care Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Jan 16;19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1393-y.

7. Norton LE et al. Improving Guideline-Based Streptococcal Pharyngitis Testing: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatrics. 2018 Jul;142(1):e20172033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2033.

8. MD+ Calc website. Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis.

9. Langlois DM, Andreae M. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Oct;32(10):423-9; quiz 430. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-10-423.

It’s wintertime, peak season for GAS pharyngitis, and you’d think that this far into the 21st century we would have a foolproof process for diagnosing which among the many patients with pharyngitis have true GAS pharyngitis. Thinking back to the 1980s, we have come a long way from simple throat cultures for detecting GAS, e.g., numerous point of care (POC) Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), waved rapid antigen detection tests (RADT), and numerous highly sensitive molecular assays, e.g. nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). But if you think the issues surrounding management of GAS pharyngitis have been solved by these newer tests, think again.

Several good reviews1-3 are excellent resources for those wishing a refresher on GAS diagnosis/management issues. They present nitty gritty details on comparative advantages/disadvantages of the many testing options while reminding us of the nuts and bolts of GAS pharyngitis. The following are a few nuggets from these articles.

Properly collected throat specimen. A quality throat specimen involves swabbing both tonsillar pillars plus posterior pharynx without touching tongue or inner cheeks. Two swab collections increase sensitivity by almost 10% compared with a single swab. Transport media is preferred if samples will not be cultured within 24 hours. Caveat: RADT testing of a transport media-diluted sample lowers sensitivity compared with direct swab use.

Reliable GAS detection. Commercially available tests in 2025 are well studied. Culture is considered a gold standard for detecting clinically relevant GAS by CDC.4 Culture has good sensitivity (estimated 80%-90% varying among studies and by quality of specimens) and 99% specificity but requires 16-24 hours for results. RADT solves the time-delay issues and has near 100% specificity but sensitivity used to be as low as 65%, hence the 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline recommendation for backup throat culture for negative tests.5 However, current RADT have sensitivities in the 85%-90% range.3,4 So a positive RADT reliably and quickly indicates GAS antigens are present. NAAT have the highest combined sensitivity and specificity, near 100% for each, and a positive reliably indicates GAS nucleic acids are present.

So why not simply always use NAAT? First, it’s a “be careful what you wish for” scenario. NAAT can, and do, detect dead remnants and colonizing GAS way more than culture.2,3 So NAAT are overly sensitive, adding an extra layer of interpretation difficulty, ie, as many as 20% of positive NAAT detections may be carriers or dead GAS. Second, NAAT often requires special instrumentation and kits are more expensive. That said, reimbursement is often higher for NAAT.

Choice based on accuracy in detecting GAS. If time delays were not a problem, culture would still seem the answer. If more rapid detection is needed, either RADT with culture back up or NAAT could be the answer. That said, consider that in the real world, throat cultures are less sensitive and RADT are less specific than indicated by some published data.6 So, the ideal answer, it seems, would be NAAT GAS detection coupled with a confirmatory biomarker of GAS infection. Such innate immune biomarkers may be on the horizon.3

But first, pretest screening. In 2025 what do we do with a positive result? Do we prescribe antibiotics? Do we think the detected GAS bacteria/antigens/nucleic acids represent the cause of the pharyngitis? Or did we just detect dead GAS or even a carrier, while a virus is the true cause? Challenges for this decision include most pharyngitis (up to 70%) being due to viruses, not GAS, plus up to 20% of GAS detections even by less sensitive culture or RADT can be carriers, plus an added 10%-20% of RADT and NAAT detections are dead GAS. Thus, with indiscriminate testing of all pharyngitis patients, the number of truly positive GAS detections that are actually “false positives” (GAS in some form is present but not causing pharyngitis) may be almost as high as for those representing true GAS pharyngitis.

Some tool is needed to minimize testing patients who are likely to have viral pharyngitis to reduce test-positive/GAS-pharyngitis-negative scenarios. Pretest patient screening therefore is critical to increase the positive predictive value of positive GAS testing results. The history and physical can be helpful. In the simplest form of pretest screening, eliminate those younger than 3 years old* or those with viral type sign/symptoms, eg conjunctivitis, cough, coryza.7 This could cut “false” positives by as much as a half. More complete validated scoring systems are also available but remain imperfect. The most published is the McIsaac score (modified Centor score).3-5,8 (See Table and Figure.)

However, even with this validated scoring system, misdiagnoses and some antibiotic misuse will likely occur, particularly if the controversial option to treat a patient with a score above 4 without testing is used. For example, a 2004 study in patients older than 3 years old revealed that 45% with a score above 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis. (McIsaac et al.) A 2012 study showed similar potential overdiagnosis from using the score without testing (45% with > 4 points did not have GAS pharyngitis). Of note, clinical scores of below 2 comprised up to 10% and would be neither tested nor treated. (Figure.)

Best clinical judgment. Regardless of the chosen test, we still need to interpret positive results, ie, use best clinical judgment. We know that even with pretest screening some positives tests will represent carriers or nonviable GAS. Yet true GAS pharyngitis needs antibiotic treatment to minimize nonpyogenic and pyogenic complications, plus reduce contagion/transmission risk and days of illness. Thus, we are forced to use best clinical judgment when considering if what could be GAS pharyngitis, particularly exudative pharyngitis, could actually be due to EBV, adenovirus, or gonococcus, each of which can mimic GAS findings. Differentiating these requires discussion beyond the scope of this article, but clues are often found in the history, the patient’s age, associated symptoms and distribution of tonsillopharyngeal exudate. Likewise Group C and G streptococcal pharyngitis can mimic GAS. Note: A comprehensive throat culture can identify these streptococci but requires a special order and likely a call to the laboratory.

Summary: The age-old problem persists, ie, differentiating the minority (~30%) of pharyngitis cases needing antibiotics from the majority that do not. We all wish to promptly treat true GAS pharyngitis; however our current tools remain imperfect. That said, we should strive to correctly diagnose/manage as many patients with pharyngitis as possible. I, for one, can’t wait until we get a validated biomarker that confirms GAS as the culprit in pharyngitis episodes. In the meantime, most providers likely have clinic or hospital approved pathways for managing GAS pharyngitis, many of which are at least in part based on data from sources for this discussion. If not, a firm foundation for creating one can be found in sources among the reference list below. Finally, if you think such pathways somehow interfere with patient flow, consider that a busy multi-provider private practice successfully integrated pretest screening and a pathway while maintaining patient flow and improving antibiotic stewardship.7

*Focal pharyngotonsillar GAS infection is rare in children younger than 3 years old, when GAS nasal passage infection may manifest as streptococcosis.9

Dr Harrison is professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, Missouri. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bannerjee D, Selvarangan RS. The Evolution of Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis Testing. Association for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine, 2018, Sep 1.

2. Cohen JF et al. Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis in Children: New Perspectives on Rapid Diagnostic Testing and Antimicrobial Stewardship. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2024 Apr 24;13(4):250-256. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piae0223.

3. Boyanton Jr BL et al. Current Laboratory and Point-of-Care Pharyngitis Diagnostic Testing and Knowledge Gaps. J Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 23;230(Suppl 3):S182–S189. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiae415.

4. Group A Strep Infection. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024, Mar 1.

5. Shulman ST et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Nov 15;55(10):e86-102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629.

6. Rao A et al. Diagnosis and Antibiotic Treatment of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children in a Primary Care Setting: Impact of Point-of-Care Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Pediatr. 2019 Jan 16;19(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1393-y.

7. Norton LE et al. Improving Guideline-Based Streptococcal Pharyngitis Testing: A Quality Improvement Initiative. Pediatrics. 2018 Jul;142(1):e20172033. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2033.

8. MD+ Calc website. Centor Score (Modified/McIsaac) for Strep Pharyngitis.

9. Langlois DM, Andreae M. Group A Streptococcal Infections. Pediatr Rev. 2011 Oct;32(10):423-9; quiz 430. doi: 10.1542/pir.32-10-423.

Central Line Skin Reactions in Children: Survey Addresses Treatment Protocols in Use

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A and reported varying management approaches.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers developed and administered a 14-item Qualtrics survey to 107 dermatologists providing pediatric inpatient care through the Society for Pediatric Dermatology’s Inpatient Dermatology Section and Section Chief email lists.

- A total of 35 dermatologists (33%) from multiple institutions responded to the survey; most respondents (94%) specialized in pediatric dermatology.

- Researchers assessed management of CLD-associated adverse skin reactions.

TAKEAWAY:

- All respondents reported receiving CLD-related consults, but 66% indicated there was no personal or institutional standardized approach for managing CLD-associated skin reactions.

- Respondents said most reactions were in children aged 1-12 years (19 or 76% of 25 respondents) compared with those aged < 1 year (3 or 12% of 25 respondents).

- Management strategies included switching to alternative products, applying topical corticosteroids, and performing patch testing for allergies.

IN PRACTICE:

“Insights derived from this study, including variation in clinician familiarity with reaction patterns, underscore the necessity of a standardized protocol for classifying and managing cutaneous CLD reactions in pediatric patients,” the authors wrote. “Further investigation is needed to better characterize CLD-associated allergic CD [contact dermatitis], irritant CD, and skin infections, as well as at-risk populations, to better inform clinical approaches,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Mulinda, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, and was published online on December 16 in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted variable respondent awareness of institutional CLD and potential recency bias as key limitations of the study.

DISCLOSURES:

Study funding source was not declared. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Imipenem-Cilastatin-Relebactam, the New Go-To for Pneumonia?

TOPLINE:

In a multinational phase 3 trial, imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam demonstrated noninferiority to piperacillin-tazobactam in treating critically ill patients with hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP) or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP), with a comparable safety profile.

METHODOLOGY:

- This multinational phase 3 trial, conducted between September 2018 and July 2022, compared imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam with piperacillin-tazobactam for HABP and VABP to support its use across multiple countries.

- Overall, 270 patients with HABP or VABP (mean age, 57.6 years; 73.3% men) were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam (500 mg/250 mg) or piperacillin-tazobactam (4000 mg/500 mg) every 6 hours over 30 minutes for 7-14 days.

- Both treatment groups included critically ill patients, with 54.5% and 55.1% of patients in the imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam and piperacillin-tazobactam groups, respectively, having an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score ≥ 15.

- The primary outcome was the 28-day all-cause mortality; secondary outcomes included the rates of clinical and microbiological responses, as well as the incidence of adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam was noninferior to piperacillin-tazobactam in terms of 28-day all-cause mortality (adjusted difference, 5.2%; 95% CI, −1.5-12.4; P = .024 for noninferiority).

- After treatment, microbiological response rates were 48.8% in the imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam group, whereas the rates were 47.9% in the piperacillin-tazobactam group.

- The incidence of drug-related adverse events was similar across the treatment groups, with diarrhea, increased levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, and abnormal hepatic function being the most common events.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results support the use of IMI/REL [imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam] in MDR [multidrug-resistant] infections globally, including to expand the range of available treatments for critically ill patients with HABP/VABP in China, and provide additional data to inform the World Health Organization’s MDR pathogen strategy,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Junjie Li, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. It was published online on December 12, 2024, in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

This study excluded patients with immunosuppression and those on intermittent hemodialysis, limiting the generalizability of the results to these populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Inc., Rahway, New Jersey. Some authors served as employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, New Jersey, and MSD, China.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In a multinational phase 3 trial, imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam demonstrated noninferiority to piperacillin-tazobactam in treating critically ill patients with hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP) or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP), with a comparable safety profile.

METHODOLOGY:

- This multinational phase 3 trial, conducted between September 2018 and July 2022, compared imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam with piperacillin-tazobactam for HABP and VABP to support its use across multiple countries.

- Overall, 270 patients with HABP or VABP (mean age, 57.6 years; 73.3% men) were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam (500 mg/250 mg) or piperacillin-tazobactam (4000 mg/500 mg) every 6 hours over 30 minutes for 7-14 days.

- Both treatment groups included critically ill patients, with 54.5% and 55.1% of patients in the imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam and piperacillin-tazobactam groups, respectively, having an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score ≥ 15.

- The primary outcome was the 28-day all-cause mortality; secondary outcomes included the rates of clinical and microbiological responses, as well as the incidence of adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam was noninferior to piperacillin-tazobactam in terms of 28-day all-cause mortality (adjusted difference, 5.2%; 95% CI, −1.5-12.4; P = .024 for noninferiority).

- After treatment, microbiological response rates were 48.8% in the imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam group, whereas the rates were 47.9% in the piperacillin-tazobactam group.

- The incidence of drug-related adverse events was similar across the treatment groups, with diarrhea, increased levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, and abnormal hepatic function being the most common events.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results support the use of IMI/REL [imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam] in MDR [multidrug-resistant] infections globally, including to expand the range of available treatments for critically ill patients with HABP/VABP in China, and provide additional data to inform the World Health Organization’s MDR pathogen strategy,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Junjie Li, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. It was published online on December 12, 2024, in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

This study excluded patients with immunosuppression and those on intermittent hemodialysis, limiting the generalizability of the results to these populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Inc., Rahway, New Jersey. Some authors served as employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, New Jersey, and MSD, China.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In a multinational phase 3 trial, imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam demonstrated noninferiority to piperacillin-tazobactam in treating critically ill patients with hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP) or ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (VABP), with a comparable safety profile.

METHODOLOGY:

- This multinational phase 3 trial, conducted between September 2018 and July 2022, compared imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam with piperacillin-tazobactam for HABP and VABP to support its use across multiple countries.

- Overall, 270 patients with HABP or VABP (mean age, 57.6 years; 73.3% men) were randomly assigned to receive either intravenous imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam (500 mg/250 mg) or piperacillin-tazobactam (4000 mg/500 mg) every 6 hours over 30 minutes for 7-14 days.

- Both treatment groups included critically ill patients, with 54.5% and 55.1% of patients in the imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam and piperacillin-tazobactam groups, respectively, having an Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score ≥ 15.

- The primary outcome was the 28-day all-cause mortality; secondary outcomes included the rates of clinical and microbiological responses, as well as the incidence of adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam was noninferior to piperacillin-tazobactam in terms of 28-day all-cause mortality (adjusted difference, 5.2%; 95% CI, −1.5-12.4; P = .024 for noninferiority).

- After treatment, microbiological response rates were 48.8% in the imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam group, whereas the rates were 47.9% in the piperacillin-tazobactam group.

- The incidence of drug-related adverse events was similar across the treatment groups, with diarrhea, increased levels of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, and abnormal hepatic function being the most common events.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results support the use of IMI/REL [imipenem-cilastatin-relebactam] in MDR [multidrug-resistant] infections globally, including to expand the range of available treatments for critically ill patients with HABP/VABP in China, and provide additional data to inform the World Health Organization’s MDR pathogen strategy,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Junjie Li, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China. It was published online on December 12, 2024, in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

LIMITATIONS:

This study excluded patients with immunosuppression and those on intermittent hemodialysis, limiting the generalizability of the results to these populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co. Inc., Rahway, New Jersey. Some authors served as employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, New Jersey, and MSD, China.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Doxycycline Kits Boost Chlamydia Treatment in ED

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A single-center retrospective chart review included adults with positive chlamydia tests in the ED between 2021 and 2023.

- In total, 98 received doxycycline discharge kits; 72 patients were enrolled before the implementation of discharge kits for comparison.

- There were no differences in symptoms of infection between patients who received and those who did not receive the kit.

- Main outcome was the number of patients who received treatment.

- Secondary outcomes included 90-day return visits for complaints of sexually transmitted infections and time to treatment initiation.

TAKEAWAY:

- Appropriate treatment rates rose significantly post-implementation of the discharge kit (69.1% vs 45.8%; odds ratio, 2.63; P = .002).

- Implementation of the discharge kit also reduced the time to definitive treatment from 22.7 hours to 1.3 hours (P < .001).

- No significant differences in 90-day ED return visits, time to initial treatment in the ED, and doxycycline prescription via culture callback programs between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pharmacy-driven doxycycline discharge kits significantly increased guideline-directed treatment and decreased time to treatment for chlamydia infections in the ED population at an urban academic medical center,” the authors wrote. “Overall, this initiative overcame barriers to treatment for a significant public health issue, supporting the need for expansion to other emergency departments across the country.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Loudermilk, Department of Pharmacy, Louisville, Kentucky, and was published online on November 14, 2024, in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design is the main limitation and lack of insurance fill history in some patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no external funding. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A single-center retrospective chart review included adults with positive chlamydia tests in the ED between 2021 and 2023.

- In total, 98 received doxycycline discharge kits; 72 patients were enrolled before the implementation of discharge kits for comparison.

- There were no differences in symptoms of infection between patients who received and those who did not receive the kit.

- Main outcome was the number of patients who received treatment.

- Secondary outcomes included 90-day return visits for complaints of sexually transmitted infections and time to treatment initiation.

TAKEAWAY:

- Appropriate treatment rates rose significantly post-implementation of the discharge kit (69.1% vs 45.8%; odds ratio, 2.63; P = .002).

- Implementation of the discharge kit also reduced the time to definitive treatment from 22.7 hours to 1.3 hours (P < .001).

- No significant differences in 90-day ED return visits, time to initial treatment in the ED, and doxycycline prescription via culture callback programs between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pharmacy-driven doxycycline discharge kits significantly increased guideline-directed treatment and decreased time to treatment for chlamydia infections in the ED population at an urban academic medical center,” the authors wrote. “Overall, this initiative overcame barriers to treatment for a significant public health issue, supporting the need for expansion to other emergency departments across the country.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Loudermilk, Department of Pharmacy, Louisville, Kentucky, and was published online on November 14, 2024, in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design is the main limitation and lack of insurance fill history in some patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no external funding. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A single-center retrospective chart review included adults with positive chlamydia tests in the ED between 2021 and 2023.

- In total, 98 received doxycycline discharge kits; 72 patients were enrolled before the implementation of discharge kits for comparison.

- There were no differences in symptoms of infection between patients who received and those who did not receive the kit.

- Main outcome was the number of patients who received treatment.

- Secondary outcomes included 90-day return visits for complaints of sexually transmitted infections and time to treatment initiation.

TAKEAWAY:

- Appropriate treatment rates rose significantly post-implementation of the discharge kit (69.1% vs 45.8%; odds ratio, 2.63; P = .002).

- Implementation of the discharge kit also reduced the time to definitive treatment from 22.7 hours to 1.3 hours (P < .001).

- No significant differences in 90-day ED return visits, time to initial treatment in the ED, and doxycycline prescription via culture callback programs between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pharmacy-driven doxycycline discharge kits significantly increased guideline-directed treatment and decreased time to treatment for chlamydia infections in the ED population at an urban academic medical center,” the authors wrote. “Overall, this initiative overcame barriers to treatment for a significant public health issue, supporting the need for expansion to other emergency departments across the country.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Carly Loudermilk, Department of Pharmacy, Louisville, Kentucky, and was published online on November 14, 2024, in The American Journal of Emergency Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

Retrospective design is the main limitation and lack of insurance fill history in some patients.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no external funding. The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Common Gut Infection Tied to Alzheimer’s Disease

Researchers are gaining new insight into the relationship between the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), a common herpes virus found in the gut, and the immune response associated with CD83 antibody in some individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Using tissue samples from deceased donors with AD, the study showed CD83-positive (CD83+) microglia in the superior frontal gyrus (SFG) are significantly associated with elevated immunoglobulin gamma 4 (IgG4) and HCMV in the transverse colon (TC), increased anti-HCMV IgG4 in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and both HCMV and IgG4 in the SFG and vagus nerve.