User login

Fatal toxicities from checkpoint inhibitors vary by agent

Fatal adverse events are uncommon with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), but they are not unknown, and it’s important to recognize rare, potentially lethal side effects with these agents, investigators say.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of records from academic medical centers and from a pharmacovigilance database found that fatal side adverse events varied in nature and severity according to the agent and immune checkpoint targeted, reported Daniel Y. Wang, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“This study underscores that the risk of death associated with complications of ICI therapy is real, but within or well below fatality rates for common oncologic interventions,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

In their study, rates of fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors ranged from 0.3% to 1.3%. In contrast, the investigators noted, platinum doublet chemotherapy is associated with a 0.9% rate of fatal toxicities, targeted therapies with angiogenesis inhibitors or tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had fatal toxicity rates up to 4%, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants are associated with a fatal adverse event rate of approximately 15%. In addition, the death rate associated with complex oncologic surgeries such as the Whipple procedure or esophagectomy ranges from 1% to 10%.

The authors queried the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database, called Vigilyze, which contains data on more than 16 million adverse drug reactions; records from patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors in seven academic centers in the United States, Germany, and Australia; and published clinical trials.

They combed through the data to identify fatal toxic effects associated with the anti-programmed death 1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), avelumab (Bavencio), and durvalumab (Imfinzi), and with the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors ipilimumab (Yervoy) and tremelimumab (investigational).

They found in the Vigilyze data that of 193 deaths attributed to CTLA-4 inhibitors, 70% were from colitis, 16% from hepatitis, 8% from pneumonitis, and the remainder from other causes. In contrast, the most common fatal toxicities associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were pneumonitis in 35%, hepatitis in 22%, colitis in 17%, and the remainder from other causes.

With the two classes of ICIs used in combination, primarily for treatment of malignant melanoma, colitis accounted for 37% of toxic fatal events, followed by myocarditis in 25%, hepatitis in 22%, pneumonitis in 14%, and others.

The events occurred early in the course of therapy, at a median of 14.5 days from the start of therapy for combination treatment, and 40 days each for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 agents.

The complication with highest fatality rate was myocarditis, which killed 39.7% of affected patients. In contrast, endocrine events and colitis were fatal in only 2%-5% of cases. The fatality rates associated with toxic effects in other organ systems ranged from 10% to 17%.

A review of data on 3,545 patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors at the seven academic centers found a 0.6% fatality rate, with cardiac and neurologic events accounting for 43% of the deaths.

The investigators also conducted a meta-analysis of data from 112 clinical trials with a total of 19,217 patients treated with ICIs. In these studies, anti-PD-1 agents were associated with a 0.36% rate of fatal toxicities, anti-PD-L1 agents were associated with a 0.38% rate, anti-CTLA-4 agents were linked to a 1.08% rate, and combined PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 therapy was associated with a 1.23% fatal toxicity rate.

“Each database largely validated the patterns of death from distinct regimens with a few exceptions. Intriguingly, our retrospective analysis at large, experienced academic centers suggested that neurologic and cardiac toxic effects comprised nearly half of deaths. Thus, we surmise that more optimized treatment of these events is urgently needed. In addition, persistent deaths from colitis and pneumonitis, events with standardized treatment algorithms and clear symptoms, suggests that patient and physician education remains a critical objective,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Wang DY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Sept 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923.

Fatal adverse events are uncommon with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), but they are not unknown, and it’s important to recognize rare, potentially lethal side effects with these agents, investigators say.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of records from academic medical centers and from a pharmacovigilance database found that fatal side adverse events varied in nature and severity according to the agent and immune checkpoint targeted, reported Daniel Y. Wang, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“This study underscores that the risk of death associated with complications of ICI therapy is real, but within or well below fatality rates for common oncologic interventions,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

In their study, rates of fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors ranged from 0.3% to 1.3%. In contrast, the investigators noted, platinum doublet chemotherapy is associated with a 0.9% rate of fatal toxicities, targeted therapies with angiogenesis inhibitors or tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had fatal toxicity rates up to 4%, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants are associated with a fatal adverse event rate of approximately 15%. In addition, the death rate associated with complex oncologic surgeries such as the Whipple procedure or esophagectomy ranges from 1% to 10%.

The authors queried the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database, called Vigilyze, which contains data on more than 16 million adverse drug reactions; records from patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors in seven academic centers in the United States, Germany, and Australia; and published clinical trials.

They combed through the data to identify fatal toxic effects associated with the anti-programmed death 1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), avelumab (Bavencio), and durvalumab (Imfinzi), and with the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors ipilimumab (Yervoy) and tremelimumab (investigational).

They found in the Vigilyze data that of 193 deaths attributed to CTLA-4 inhibitors, 70% were from colitis, 16% from hepatitis, 8% from pneumonitis, and the remainder from other causes. In contrast, the most common fatal toxicities associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were pneumonitis in 35%, hepatitis in 22%, colitis in 17%, and the remainder from other causes.

With the two classes of ICIs used in combination, primarily for treatment of malignant melanoma, colitis accounted for 37% of toxic fatal events, followed by myocarditis in 25%, hepatitis in 22%, pneumonitis in 14%, and others.

The events occurred early in the course of therapy, at a median of 14.5 days from the start of therapy for combination treatment, and 40 days each for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 agents.

The complication with highest fatality rate was myocarditis, which killed 39.7% of affected patients. In contrast, endocrine events and colitis were fatal in only 2%-5% of cases. The fatality rates associated with toxic effects in other organ systems ranged from 10% to 17%.

A review of data on 3,545 patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors at the seven academic centers found a 0.6% fatality rate, with cardiac and neurologic events accounting for 43% of the deaths.

The investigators also conducted a meta-analysis of data from 112 clinical trials with a total of 19,217 patients treated with ICIs. In these studies, anti-PD-1 agents were associated with a 0.36% rate of fatal toxicities, anti-PD-L1 agents were associated with a 0.38% rate, anti-CTLA-4 agents were linked to a 1.08% rate, and combined PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 therapy was associated with a 1.23% fatal toxicity rate.

“Each database largely validated the patterns of death from distinct regimens with a few exceptions. Intriguingly, our retrospective analysis at large, experienced academic centers suggested that neurologic and cardiac toxic effects comprised nearly half of deaths. Thus, we surmise that more optimized treatment of these events is urgently needed. In addition, persistent deaths from colitis and pneumonitis, events with standardized treatment algorithms and clear symptoms, suggests that patient and physician education remains a critical objective,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Wang DY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Sept 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923.

Fatal adverse events are uncommon with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI), but they are not unknown, and it’s important to recognize rare, potentially lethal side effects with these agents, investigators say.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of records from academic medical centers and from a pharmacovigilance database found that fatal side adverse events varied in nature and severity according to the agent and immune checkpoint targeted, reported Daniel Y. Wang, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his colleagues.

“This study underscores that the risk of death associated with complications of ICI therapy is real, but within or well below fatality rates for common oncologic interventions,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

In their study, rates of fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors ranged from 0.3% to 1.3%. In contrast, the investigators noted, platinum doublet chemotherapy is associated with a 0.9% rate of fatal toxicities, targeted therapies with angiogenesis inhibitors or tyrosine kinase inhibitors have had fatal toxicity rates up to 4%, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants are associated with a fatal adverse event rate of approximately 15%. In addition, the death rate associated with complex oncologic surgeries such as the Whipple procedure or esophagectomy ranges from 1% to 10%.

The authors queried the World Health Organization pharmacovigilance database, called Vigilyze, which contains data on more than 16 million adverse drug reactions; records from patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors in seven academic centers in the United States, Germany, and Australia; and published clinical trials.

They combed through the data to identify fatal toxic effects associated with the anti-programmed death 1/ligand-1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), atezolizumab (Tecentriq), avelumab (Bavencio), and durvalumab (Imfinzi), and with the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) inhibitors ipilimumab (Yervoy) and tremelimumab (investigational).

They found in the Vigilyze data that of 193 deaths attributed to CTLA-4 inhibitors, 70% were from colitis, 16% from hepatitis, 8% from pneumonitis, and the remainder from other causes. In contrast, the most common fatal toxicities associated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors were pneumonitis in 35%, hepatitis in 22%, colitis in 17%, and the remainder from other causes.

With the two classes of ICIs used in combination, primarily for treatment of malignant melanoma, colitis accounted for 37% of toxic fatal events, followed by myocarditis in 25%, hepatitis in 22%, pneumonitis in 14%, and others.

The events occurred early in the course of therapy, at a median of 14.5 days from the start of therapy for combination treatment, and 40 days each for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 agents.

The complication with highest fatality rate was myocarditis, which killed 39.7% of affected patients. In contrast, endocrine events and colitis were fatal in only 2%-5% of cases. The fatality rates associated with toxic effects in other organ systems ranged from 10% to 17%.

A review of data on 3,545 patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors at the seven academic centers found a 0.6% fatality rate, with cardiac and neurologic events accounting for 43% of the deaths.

The investigators also conducted a meta-analysis of data from 112 clinical trials with a total of 19,217 patients treated with ICIs. In these studies, anti-PD-1 agents were associated with a 0.36% rate of fatal toxicities, anti-PD-L1 agents were associated with a 0.38% rate, anti-CTLA-4 agents were linked to a 1.08% rate, and combined PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 therapy was associated with a 1.23% fatal toxicity rate.

“Each database largely validated the patterns of death from distinct regimens with a few exceptions. Intriguingly, our retrospective analysis at large, experienced academic centers suggested that neurologic and cardiac toxic effects comprised nearly half of deaths. Thus, we surmise that more optimized treatment of these events is urgently needed. In addition, persistent deaths from colitis and pneumonitis, events with standardized treatment algorithms and clear symptoms, suggests that patient and physician education remains a critical objective,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE: Wang DY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Sept 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Clinicians should be aware of the potential fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Major finding: Cardiac and neurologic toxicities accounted for approximately 43% of all toxicity related deaths.

Study details: Systematic review from WHO data on fatal adverse events, data on 3,545 patients treated in academic medical centers, and a meta-analysis from 112 trials involving 19,217 patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the French National Alliance for Life and Health Sciences, “Plan Cancer 2014-2019,” the National Institutes of Health, the James C. Bradford Jr. Melanoma Fund, and the Melanoma Research Foundation. Corresponding author Douglas B Johnson, MD, disclosed serving on advisory boards for Array Biopharma, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, Merck, Novartis, and Navigate BP, and research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb and Incyte. Four other coauthors reported similar relationships.

Source: Wang DY et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Sept 13. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923.

Sunscreens: Survey of the Cutis Editorial Board

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on sunscreens. Here’s what we found.

What sun protection factor (SPF) do you recommend for the majority of your patients?

Fifty percent of dermatologists we surveyed recommend SPF 30. SPF 50 was recommended by 26%, SPF 50+ by 21%, and SPF 15 by only 2%.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Half of our Editorial Board recommends sunscreen with SPF 30, with many recommending SPF 50 or higher. This trend toward sunscreens with higher SPF is consistent with a survey-based study with 97% of dermatologists stating they were comfortable recommending sunscreens with an SPF of 50 or higher and 83.3% stating that they believe that high SPF sunscreens provide an additional margin of safety (Farberg et al). These trends are supported by a randomized, double-blind, split-face clinical trial in which participants applied either SPF 50+ or SPF 100+ sunscreen after exposure to natural sunlight. The results showed that SPF 100+ sunscreen was remarkably more effective in protecting against sunburn than SPF 50+ sunscreen in actual use conditions (Williams et al).

Next page: Spray sunscreens

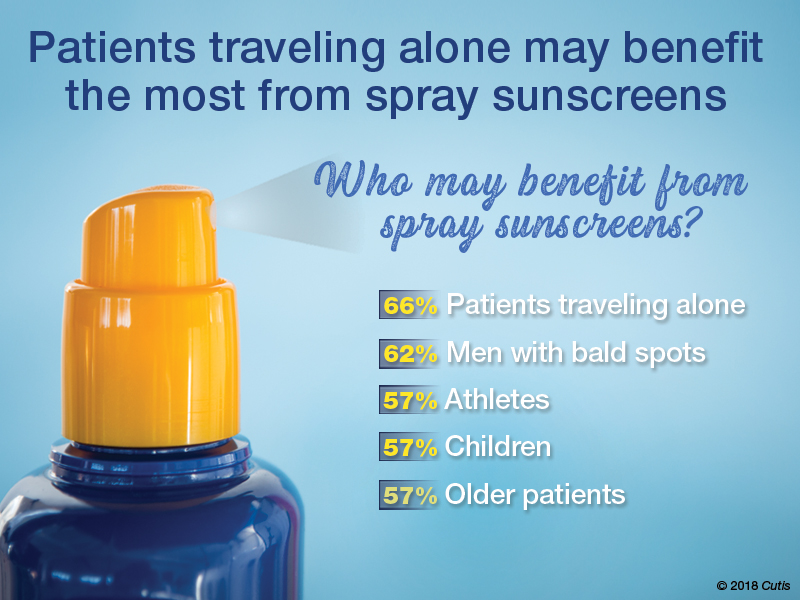

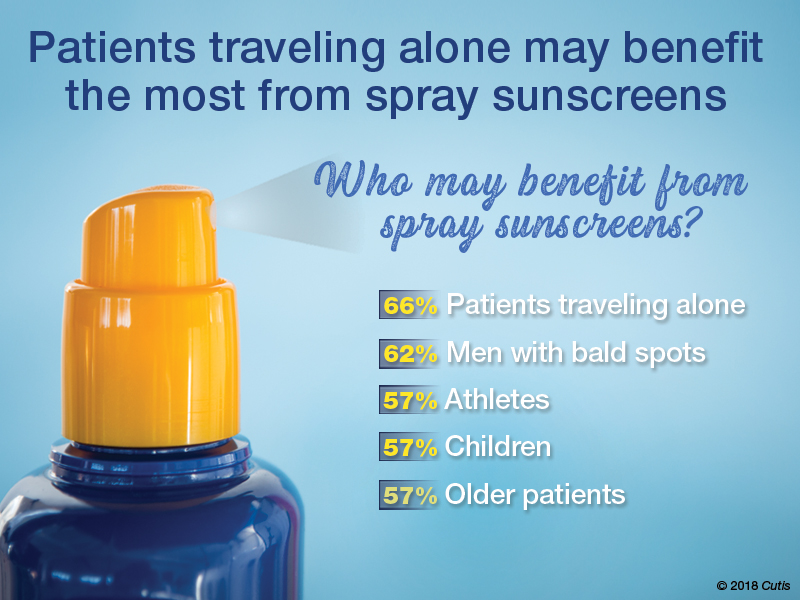

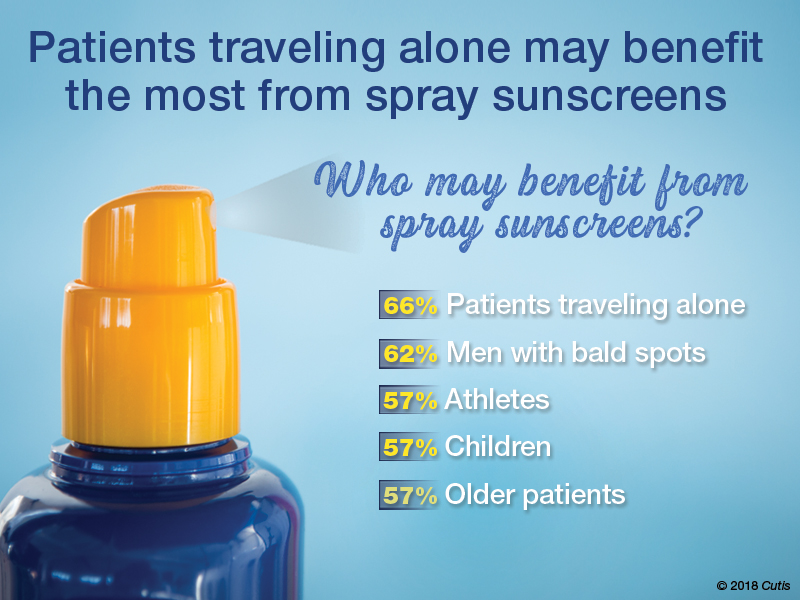

Which patient populations do you feel may benefit from spray sunscreens?

Two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that spray sunscreens may benefit patients traveling alone. Men with bald spots also may benefit (62%), as well as athletes, children, and older patients (57% each).

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

As dermatologists, we tell our patients that the best sunscreens are ones that are used consistently. Spray sunscreens are likely as effective as lotions (Ou-Yang et al). There has been a clear trend in consumer purchasing of spray sunscreens from 2011 to 2016 (Teplitz et al). Spray sunscreens may benefit those traveling alone, particularly for hard-to-reach areas.

Next page: Supplemental vitamin D

In patients who apply sunscreen regularly, do you recommend supplemental vitamin D3?

More than half (53%) of dermatologists recommend supplemental vitamin D3.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Because use of photoprotection results in decreased vitamin D levels in most individuals, it is good practice to recommend vitamin D supplementation in patients who are applying sunscreen regularly (Bogaczewicz et al).

Next page: Sunscreen compliance

What is the most often heard reason(s) for not using sunscreen in your patients?

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of dermatologists reported that patients do not use sunscreen because of cosmetic acceptance. Almost one-third (31%) said their patients prefer “natural” products. Price was a factor for 26%. Fewer dermatologists indicated risk of environmental damage (14%), allergy (12%), cancer induction (5%), and hormonal alteration (5%) were reasons patients are not compliant.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Cosmetic acceptance is paramount for patient compliance for sunscreen application. These results from our Editorial Board echo a study on sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences, which cited “cosmetic elegance” as an important factor in choosing sunscreens (Xu et al). Dermatologists must stress to patients to find a sunscreen that they find acceptable in terms of vehicle and price to increase compliance.

Next page: Sunscreens in pregnant women

What sunscreens do you recommend to pregnant women and children?

Most dermatologists (86%) recommend physical blockers “chemical-free” only sunscreens to pregnant women and children.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

While absorption of sunscreen by human embryos is likely negligible, because there is limited data on sunscreen effects in embryos and children, it is reasonable to recommend physical blockers for pregnant women and children.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

As a dermatologist married to a pediatrician, I try to get my kids to embrace sun-protection strategies. For the little ones it’s hard, but as they have gotten older and been exposed to more derm journals sitting around with pretty graphic pictures, they seem to get on board, even when away at summer camp on their own. If only our patients knew what our kids do.—Joel L. Cohen, MD (Denver, Colorado)

The most important factor in getting patient compliance with sunscreen usage is “cosmetic acceptance.” If they or their children or their spouse don’t like the feel, they won’t use it.—Vincent A. DeLeo, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Not using photoprotection with sunscreen is like crossing a busy road without looking both ways first.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

I do not recommend spray sunscreens. At least half of the spray seems to go in the air rather than on the skin. And people often do not rub the spray into their skin well enough. Lotions are better!—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

The most important factor in sunscreen is not SPF; educate patients on the important role vehicle and sweating play in the length of sun protection.—Orit Markowitz, MD (New York, New York)

Reapplying sunscreen in the appropriate amount is key to blocking the danger rays of the sun.—Vineet Mishra, MD (San Antonio, Texas)

A good sunscreen is the one you put on properly. Regardless of the formulation, make sure you apply the sunscreen evenly to all exposed skin and reapply according to directions on the container. Remember, a regular white T-shirt has minimal SPF 4-5. Either wear sun-protective clothing or wear sunscreen underneath!—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD (Gahanna, Ohio)

Sun protection and sunscreen application go hand-in-hand. We can still enjoy the outdoors without getting excessive UV exposure.—Anthony M. Rossi, MD (New York, New York)

Sunscreens are only part of sun protection. Make sure to reapply them regularly, try to avoid direct sun between about 10 AM and 2 PM if possible, and wear a hat with a wide brim (not a baseball cap, which, after all, is designed for catching baseballs, not sun protection).—Robert I. Rudolph, MD (Wyomissing, Pennsylvania)

Sunscreens keep you younger looking longer!—Richard K. Scher, MD (New York, New York)

The dentist says only floss the teeth you want to keep. I tell patients to only sun block the skin they want to keep.—Daniel M. Siegel, MD, MS (Brooklyn, New York)

The best sunscreen is the one that is used! If it's too greasy or drying, smells bad or stings, it won't be used. Stick to the one YOU like, but at least SPF 30 or better.—Stephen P. Stone, MD, (Springfield, Illinois)

Sunscreen can be a meaningful part of your sun-protection regimen used in conjunction with sun-protective clothing, sun safe behaviors, and a diet rich in natural antioxidants.—Michelle Tarbox, MD (Lubbock, Texas)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from August 2, 2018, to September 2, 2018. A total of 42 usable responses were received.

Bogaczewicz J, Karczmarewicz E, Pludowski P, et al. Requirement for vitamin D supplementation in patients using photoprotection: variations in vitamin D levels and bone formation markers. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e176-e183.

Farberg AS, Glazer AM, Rigel AC, et al. Dermatologists’ perceptions, recommendations, and use of sunscreen. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:99-101.

Ou-Yang H, Stanfield J, Cole C, et al. High-SPF sunscreens (SPF ≥ 70) may provide ultraviolet protection above minimal recommended levels by adequately compensating for lower sunscreen user application amounts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1220-1227.

Teplitz RW, Glazer AM, Svoboda RM, et al. Trends in US sunscreen formulations: impact of increasing spray usage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:187-189.

Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: Results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902.e2-910.e2.

Xu S, Kwa M, Agarwal A, et al. Sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:920-927.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on sunscreens. Here’s what we found.

What sun protection factor (SPF) do you recommend for the majority of your patients?

Fifty percent of dermatologists we surveyed recommend SPF 30. SPF 50 was recommended by 26%, SPF 50+ by 21%, and SPF 15 by only 2%.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Half of our Editorial Board recommends sunscreen with SPF 30, with many recommending SPF 50 or higher. This trend toward sunscreens with higher SPF is consistent with a survey-based study with 97% of dermatologists stating they were comfortable recommending sunscreens with an SPF of 50 or higher and 83.3% stating that they believe that high SPF sunscreens provide an additional margin of safety (Farberg et al). These trends are supported by a randomized, double-blind, split-face clinical trial in which participants applied either SPF 50+ or SPF 100+ sunscreen after exposure to natural sunlight. The results showed that SPF 100+ sunscreen was remarkably more effective in protecting against sunburn than SPF 50+ sunscreen in actual use conditions (Williams et al).

Next page: Spray sunscreens

Which patient populations do you feel may benefit from spray sunscreens?

Two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that spray sunscreens may benefit patients traveling alone. Men with bald spots also may benefit (62%), as well as athletes, children, and older patients (57% each).

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

As dermatologists, we tell our patients that the best sunscreens are ones that are used consistently. Spray sunscreens are likely as effective as lotions (Ou-Yang et al). There has been a clear trend in consumer purchasing of spray sunscreens from 2011 to 2016 (Teplitz et al). Spray sunscreens may benefit those traveling alone, particularly for hard-to-reach areas.

Next page: Supplemental vitamin D

In patients who apply sunscreen regularly, do you recommend supplemental vitamin D3?

More than half (53%) of dermatologists recommend supplemental vitamin D3.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Because use of photoprotection results in decreased vitamin D levels in most individuals, it is good practice to recommend vitamin D supplementation in patients who are applying sunscreen regularly (Bogaczewicz et al).

Next page: Sunscreen compliance

What is the most often heard reason(s) for not using sunscreen in your patients?

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of dermatologists reported that patients do not use sunscreen because of cosmetic acceptance. Almost one-third (31%) said their patients prefer “natural” products. Price was a factor for 26%. Fewer dermatologists indicated risk of environmental damage (14%), allergy (12%), cancer induction (5%), and hormonal alteration (5%) were reasons patients are not compliant.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Cosmetic acceptance is paramount for patient compliance for sunscreen application. These results from our Editorial Board echo a study on sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences, which cited “cosmetic elegance” as an important factor in choosing sunscreens (Xu et al). Dermatologists must stress to patients to find a sunscreen that they find acceptable in terms of vehicle and price to increase compliance.

Next page: Sunscreens in pregnant women

What sunscreens do you recommend to pregnant women and children?

Most dermatologists (86%) recommend physical blockers “chemical-free” only sunscreens to pregnant women and children.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

While absorption of sunscreen by human embryos is likely negligible, because there is limited data on sunscreen effects in embryos and children, it is reasonable to recommend physical blockers for pregnant women and children.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

As a dermatologist married to a pediatrician, I try to get my kids to embrace sun-protection strategies. For the little ones it’s hard, but as they have gotten older and been exposed to more derm journals sitting around with pretty graphic pictures, they seem to get on board, even when away at summer camp on their own. If only our patients knew what our kids do.—Joel L. Cohen, MD (Denver, Colorado)

The most important factor in getting patient compliance with sunscreen usage is “cosmetic acceptance.” If they or their children or their spouse don’t like the feel, they won’t use it.—Vincent A. DeLeo, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Not using photoprotection with sunscreen is like crossing a busy road without looking both ways first.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

I do not recommend spray sunscreens. At least half of the spray seems to go in the air rather than on the skin. And people often do not rub the spray into their skin well enough. Lotions are better!—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

The most important factor in sunscreen is not SPF; educate patients on the important role vehicle and sweating play in the length of sun protection.—Orit Markowitz, MD (New York, New York)

Reapplying sunscreen in the appropriate amount is key to blocking the danger rays of the sun.—Vineet Mishra, MD (San Antonio, Texas)

A good sunscreen is the one you put on properly. Regardless of the formulation, make sure you apply the sunscreen evenly to all exposed skin and reapply according to directions on the container. Remember, a regular white T-shirt has minimal SPF 4-5. Either wear sun-protective clothing or wear sunscreen underneath!—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD (Gahanna, Ohio)

Sun protection and sunscreen application go hand-in-hand. We can still enjoy the outdoors without getting excessive UV exposure.—Anthony M. Rossi, MD (New York, New York)

Sunscreens are only part of sun protection. Make sure to reapply them regularly, try to avoid direct sun between about 10 AM and 2 PM if possible, and wear a hat with a wide brim (not a baseball cap, which, after all, is designed for catching baseballs, not sun protection).—Robert I. Rudolph, MD (Wyomissing, Pennsylvania)

Sunscreens keep you younger looking longer!—Richard K. Scher, MD (New York, New York)

The dentist says only floss the teeth you want to keep. I tell patients to only sun block the skin they want to keep.—Daniel M. Siegel, MD, MS (Brooklyn, New York)

The best sunscreen is the one that is used! If it's too greasy or drying, smells bad or stings, it won't be used. Stick to the one YOU like, but at least SPF 30 or better.—Stephen P. Stone, MD, (Springfield, Illinois)

Sunscreen can be a meaningful part of your sun-protection regimen used in conjunction with sun-protective clothing, sun safe behaviors, and a diet rich in natural antioxidants.—Michelle Tarbox, MD (Lubbock, Texas)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from August 2, 2018, to September 2, 2018. A total of 42 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on sunscreens. Here’s what we found.

What sun protection factor (SPF) do you recommend for the majority of your patients?

Fifty percent of dermatologists we surveyed recommend SPF 30. SPF 50 was recommended by 26%, SPF 50+ by 21%, and SPF 15 by only 2%.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Half of our Editorial Board recommends sunscreen with SPF 30, with many recommending SPF 50 or higher. This trend toward sunscreens with higher SPF is consistent with a survey-based study with 97% of dermatologists stating they were comfortable recommending sunscreens with an SPF of 50 or higher and 83.3% stating that they believe that high SPF sunscreens provide an additional margin of safety (Farberg et al). These trends are supported by a randomized, double-blind, split-face clinical trial in which participants applied either SPF 50+ or SPF 100+ sunscreen after exposure to natural sunlight. The results showed that SPF 100+ sunscreen was remarkably more effective in protecting against sunburn than SPF 50+ sunscreen in actual use conditions (Williams et al).

Next page: Spray sunscreens

Which patient populations do you feel may benefit from spray sunscreens?

Two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that spray sunscreens may benefit patients traveling alone. Men with bald spots also may benefit (62%), as well as athletes, children, and older patients (57% each).

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

As dermatologists, we tell our patients that the best sunscreens are ones that are used consistently. Spray sunscreens are likely as effective as lotions (Ou-Yang et al). There has been a clear trend in consumer purchasing of spray sunscreens from 2011 to 2016 (Teplitz et al). Spray sunscreens may benefit those traveling alone, particularly for hard-to-reach areas.

Next page: Supplemental vitamin D

In patients who apply sunscreen regularly, do you recommend supplemental vitamin D3?

More than half (53%) of dermatologists recommend supplemental vitamin D3.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Because use of photoprotection results in decreased vitamin D levels in most individuals, it is good practice to recommend vitamin D supplementation in patients who are applying sunscreen regularly (Bogaczewicz et al).

Next page: Sunscreen compliance

What is the most often heard reason(s) for not using sunscreen in your patients?

Nearly three-quarters (72%) of dermatologists reported that patients do not use sunscreen because of cosmetic acceptance. Almost one-third (31%) said their patients prefer “natural” products. Price was a factor for 26%. Fewer dermatologists indicated risk of environmental damage (14%), allergy (12%), cancer induction (5%), and hormonal alteration (5%) were reasons patients are not compliant.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Cosmetic acceptance is paramount for patient compliance for sunscreen application. These results from our Editorial Board echo a study on sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences, which cited “cosmetic elegance” as an important factor in choosing sunscreens (Xu et al). Dermatologists must stress to patients to find a sunscreen that they find acceptable in terms of vehicle and price to increase compliance.

Next page: Sunscreens in pregnant women

What sunscreens do you recommend to pregnant women and children?

Most dermatologists (86%) recommend physical blockers “chemical-free” only sunscreens to pregnant women and children.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

While absorption of sunscreen by human embryos is likely negligible, because there is limited data on sunscreen effects in embryos and children, it is reasonable to recommend physical blockers for pregnant women and children.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

As a dermatologist married to a pediatrician, I try to get my kids to embrace sun-protection strategies. For the little ones it’s hard, but as they have gotten older and been exposed to more derm journals sitting around with pretty graphic pictures, they seem to get on board, even when away at summer camp on their own. If only our patients knew what our kids do.—Joel L. Cohen, MD (Denver, Colorado)

The most important factor in getting patient compliance with sunscreen usage is “cosmetic acceptance.” If they or their children or their spouse don’t like the feel, they won’t use it.—Vincent A. DeLeo, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Not using photoprotection with sunscreen is like crossing a busy road without looking both ways first.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

I do not recommend spray sunscreens. At least half of the spray seems to go in the air rather than on the skin. And people often do not rub the spray into their skin well enough. Lotions are better!—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

The most important factor in sunscreen is not SPF; educate patients on the important role vehicle and sweating play in the length of sun protection.—Orit Markowitz, MD (New York, New York)

Reapplying sunscreen in the appropriate amount is key to blocking the danger rays of the sun.—Vineet Mishra, MD (San Antonio, Texas)

A good sunscreen is the one you put on properly. Regardless of the formulation, make sure you apply the sunscreen evenly to all exposed skin and reapply according to directions on the container. Remember, a regular white T-shirt has minimal SPF 4-5. Either wear sun-protective clothing or wear sunscreen underneath!—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD (Gahanna, Ohio)

Sun protection and sunscreen application go hand-in-hand. We can still enjoy the outdoors without getting excessive UV exposure.—Anthony M. Rossi, MD (New York, New York)

Sunscreens are only part of sun protection. Make sure to reapply them regularly, try to avoid direct sun between about 10 AM and 2 PM if possible, and wear a hat with a wide brim (not a baseball cap, which, after all, is designed for catching baseballs, not sun protection).—Robert I. Rudolph, MD (Wyomissing, Pennsylvania)

Sunscreens keep you younger looking longer!—Richard K. Scher, MD (New York, New York)

The dentist says only floss the teeth you want to keep. I tell patients to only sun block the skin they want to keep.—Daniel M. Siegel, MD, MS (Brooklyn, New York)

The best sunscreen is the one that is used! If it's too greasy or drying, smells bad or stings, it won't be used. Stick to the one YOU like, but at least SPF 30 or better.—Stephen P. Stone, MD, (Springfield, Illinois)

Sunscreen can be a meaningful part of your sun-protection regimen used in conjunction with sun-protective clothing, sun safe behaviors, and a diet rich in natural antioxidants.—Michelle Tarbox, MD (Lubbock, Texas)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from August 2, 2018, to September 2, 2018. A total of 42 usable responses were received.

Bogaczewicz J, Karczmarewicz E, Pludowski P, et al. Requirement for vitamin D supplementation in patients using photoprotection: variations in vitamin D levels and bone formation markers. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e176-e183.

Farberg AS, Glazer AM, Rigel AC, et al. Dermatologists’ perceptions, recommendations, and use of sunscreen. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:99-101.

Ou-Yang H, Stanfield J, Cole C, et al. High-SPF sunscreens (SPF ≥ 70) may provide ultraviolet protection above minimal recommended levels by adequately compensating for lower sunscreen user application amounts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1220-1227.

Teplitz RW, Glazer AM, Svoboda RM, et al. Trends in US sunscreen formulations: impact of increasing spray usage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:187-189.

Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: Results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902.e2-910.e2.

Xu S, Kwa M, Agarwal A, et al. Sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:920-927.

Bogaczewicz J, Karczmarewicz E, Pludowski P, et al. Requirement for vitamin D supplementation in patients using photoprotection: variations in vitamin D levels and bone formation markers. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e176-e183.

Farberg AS, Glazer AM, Rigel AC, et al. Dermatologists’ perceptions, recommendations, and use of sunscreen. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:99-101.

Ou-Yang H, Stanfield J, Cole C, et al. High-SPF sunscreens (SPF ≥ 70) may provide ultraviolet protection above minimal recommended levels by adequately compensating for lower sunscreen user application amounts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1220-1227.

Teplitz RW, Glazer AM, Svoboda RM, et al. Trends in US sunscreen formulations: impact of increasing spray usage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:187-189.

Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: Results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902.e2-910.e2.

Xu S, Kwa M, Agarwal A, et al. Sunscreen product performance and other determinants of consumer preferences. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:920-927.

Skin signs may be good omens during cancer therapy

Signs of efficacy of anti-cancer therapies may be only skin deep, results of a retrospective review indicate.

Cutaneous toxicities such as vitiligo, rash, alopecia, and nail toxicities may be early signs of efficacy of targeted therapies, immunotherapy, or cytotoxic chemotherapy, according to Alexandra K. Rzepecki, of the University of Michigan, and her coauthors from Albert Einstein Medical College in the Bronx, New York.

“Because cutaneous toxicities are a clinically visible parameter, they may alert clinicians to the possibility of treatment success or failure in a rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive manner,” they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators reviewed the medical literature for clinical studies of three major classes of anti-cancer therapies that included data on associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes such progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS).

The drug classes and their associations with cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes were as follows:

- Targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as cetuximab (Erbitux) and erlotinib (Tarceva), and multikinase targeted agents such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and sunitinib (Sutent). Toxicities associated with clinical benefit from EGFR inhibitors include rash, xerosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, paronychia, and pruritus, whereas skin toxicities associated with the multikinase inhibitors trended toward the hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction.

- Immunotherapies included blockers of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) such as ipilimumab (Yervoy) and inhibitors of programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) such as nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and atezolizumab (Tecentriq). In studies of pembrolizumab for various malignancies, rash or vitiligo was an independent prognostic factor for longer OS, a higher proportion of objective responses, and longer PFS. Similar associations were seen with nivolumab, with the additional association of hair repigmentation among patients with non–small-cell lung cancer being associated with stable disease responses or better. Among patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab, hair depigmentation correlated with durable responses.

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents included the anthracycline doxorubicin, taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, platinum agents (cisplatin and carboplatin), and fluoropyrimidines such as capecitabine. Patients treated for various cancers with doxorubicin who had alopecia were significantly more likely to have clinical remissions than were patients who did not lose their hair, and patients treated with this agent who developed hand-foot syndrome had significantly longer PFS. For patients treated with docetaxel, severity of nail changes and/or development of nail alterations were associated with both improved OS and PFS. Patients treated with the combination of paclitaxel and a platinum agent who developed grade 2 or greater alopecia up to cycle 3 had significantly longer OS than did patients who had hair loss later in the course of therapy. Patients treated with capecitabine who developed had hand-foot skin reactions had improved progression-free and disease-free survival.

“Although further studies are needed to better evaluate these promising associations, vigilant monitoring of cutaneous toxicities should be a priority, as their development may indicate a favorable response to treatment. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with oncologists to help identify and manage these toxicities, thereby allowing patients to receive life-prolonging anticancer therapy while minimizing dose reduction or interruption of their treatment,” the authors wrote.

They reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rzepecki A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:545-555.

Signs of efficacy of anti-cancer therapies may be only skin deep, results of a retrospective review indicate.

Cutaneous toxicities such as vitiligo, rash, alopecia, and nail toxicities may be early signs of efficacy of targeted therapies, immunotherapy, or cytotoxic chemotherapy, according to Alexandra K. Rzepecki, of the University of Michigan, and her coauthors from Albert Einstein Medical College in the Bronx, New York.

“Because cutaneous toxicities are a clinically visible parameter, they may alert clinicians to the possibility of treatment success or failure in a rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive manner,” they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators reviewed the medical literature for clinical studies of three major classes of anti-cancer therapies that included data on associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes such progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS).

The drug classes and their associations with cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes were as follows:

- Targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as cetuximab (Erbitux) and erlotinib (Tarceva), and multikinase targeted agents such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and sunitinib (Sutent). Toxicities associated with clinical benefit from EGFR inhibitors include rash, xerosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, paronychia, and pruritus, whereas skin toxicities associated with the multikinase inhibitors trended toward the hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction.

- Immunotherapies included blockers of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) such as ipilimumab (Yervoy) and inhibitors of programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) such as nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and atezolizumab (Tecentriq). In studies of pembrolizumab for various malignancies, rash or vitiligo was an independent prognostic factor for longer OS, a higher proportion of objective responses, and longer PFS. Similar associations were seen with nivolumab, with the additional association of hair repigmentation among patients with non–small-cell lung cancer being associated with stable disease responses or better. Among patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab, hair depigmentation correlated with durable responses.

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents included the anthracycline doxorubicin, taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, platinum agents (cisplatin and carboplatin), and fluoropyrimidines such as capecitabine. Patients treated for various cancers with doxorubicin who had alopecia were significantly more likely to have clinical remissions than were patients who did not lose their hair, and patients treated with this agent who developed hand-foot syndrome had significantly longer PFS. For patients treated with docetaxel, severity of nail changes and/or development of nail alterations were associated with both improved OS and PFS. Patients treated with the combination of paclitaxel and a platinum agent who developed grade 2 or greater alopecia up to cycle 3 had significantly longer OS than did patients who had hair loss later in the course of therapy. Patients treated with capecitabine who developed had hand-foot skin reactions had improved progression-free and disease-free survival.

“Although further studies are needed to better evaluate these promising associations, vigilant monitoring of cutaneous toxicities should be a priority, as their development may indicate a favorable response to treatment. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with oncologists to help identify and manage these toxicities, thereby allowing patients to receive life-prolonging anticancer therapy while minimizing dose reduction or interruption of their treatment,” the authors wrote.

They reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rzepecki A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:545-555.

Signs of efficacy of anti-cancer therapies may be only skin deep, results of a retrospective review indicate.

Cutaneous toxicities such as vitiligo, rash, alopecia, and nail toxicities may be early signs of efficacy of targeted therapies, immunotherapy, or cytotoxic chemotherapy, according to Alexandra K. Rzepecki, of the University of Michigan, and her coauthors from Albert Einstein Medical College in the Bronx, New York.

“Because cutaneous toxicities are a clinically visible parameter, they may alert clinicians to the possibility of treatment success or failure in a rapid, cost-effective, and noninvasive manner,” they wrote. The report is in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The investigators reviewed the medical literature for clinical studies of three major classes of anti-cancer therapies that included data on associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes such progression-free survival (PFS) overall survival (OS).

The drug classes and their associations with cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes were as follows:

- Targeted therapies, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) such as cetuximab (Erbitux) and erlotinib (Tarceva), and multikinase targeted agents such as sorafenib (Nexavar) and sunitinib (Sutent). Toxicities associated with clinical benefit from EGFR inhibitors include rash, xerosis, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, paronychia, and pruritus, whereas skin toxicities associated with the multikinase inhibitors trended toward the hand-foot syndrome and hand-foot skin reaction.

- Immunotherapies included blockers of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4) such as ipilimumab (Yervoy) and inhibitors of programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand 1 (PD-L1) such as nivolumab (Opdivo), pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and atezolizumab (Tecentriq). In studies of pembrolizumab for various malignancies, rash or vitiligo was an independent prognostic factor for longer OS, a higher proportion of objective responses, and longer PFS. Similar associations were seen with nivolumab, with the additional association of hair repigmentation among patients with non–small-cell lung cancer being associated with stable disease responses or better. Among patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab, hair depigmentation correlated with durable responses.

- Cytotoxic chemotherapy agents included the anthracycline doxorubicin, taxanes such as paclitaxel and docetaxel, platinum agents (cisplatin and carboplatin), and fluoropyrimidines such as capecitabine. Patients treated for various cancers with doxorubicin who had alopecia were significantly more likely to have clinical remissions than were patients who did not lose their hair, and patients treated with this agent who developed hand-foot syndrome had significantly longer PFS. For patients treated with docetaxel, severity of nail changes and/or development of nail alterations were associated with both improved OS and PFS. Patients treated with the combination of paclitaxel and a platinum agent who developed grade 2 or greater alopecia up to cycle 3 had significantly longer OS than did patients who had hair loss later in the course of therapy. Patients treated with capecitabine who developed had hand-foot skin reactions had improved progression-free and disease-free survival.

“Although further studies are needed to better evaluate these promising associations, vigilant monitoring of cutaneous toxicities should be a priority, as their development may indicate a favorable response to treatment. Dermatologists have a unique opportunity to collaborate with oncologists to help identify and manage these toxicities, thereby allowing patients to receive life-prolonging anticancer therapy while minimizing dose reduction or interruption of their treatment,” the authors wrote.

They reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rzepecki A, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:545-555.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cutaneous adverse events may be early signs of drug efficacy in patients treated for various cancers.

Major finding: Cutaneous toxicities with targeted therapies, immunotherapy, and cytotoxic drugs were associated in multiple studies with improved outcomes, including progression-free and overall survival.

Study details: Retrospective review of medical literature for clinical studies reporting associations between cutaneous toxicities and clinical outcomes of cancer therapy.

Disclosures: The authors reported no study funding source and no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rzepecki A et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Sep;79[3]:545-55.

Reflectance confocal microscopy: The future looks bright

CHICAGO – The future looks bright for to rule out malignancy, Ann M. John, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“With the advent of dermoscopy, dermatologists were able to elucidate both benign and malignant patterns to help further guide their decision to biopsy or not. This increased diagnostic accuracy of suspicious lesions by 30%, while reducing the benign to malignant ratio of biopsies performed from 18:1 to 4:1. However, there are still lesions that are equivocal on dermoscopy, as we all know, and for this, there’s reflectance confocal microscopy,” observed Dr. John, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

RCM is a device technology that’s been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration since 2008 for the imaging of clinically suspicious lesions. It employs laser scanning to assess the light-scattering properties of cells in the epidermis and dermis, generating images with resolution comparable to histology.

RCM took a back seat initially while American dermatologists were gradually coming to embrace dermoscopy, which their European colleagues had done years earlier. Now, with the availability of handheld RCM for use in the dermatology clinic, expect RCM to assume a growing role in daily practice.

To illustrate the power of RCM as a diagnostic aid, she presented a single-center retrospective study of 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions that were equivocal on dermoscopy and then assessed using RCM with 1 year of subsequent patient follow-up. Overall, 155 lesions were deemed positive for cancer or atypia by RCM, while 1,034 were determined to be benign. Of those 155, 46 lesions were considered false positives because of their benign appearance on histologic inspection of the biopsy sample. Only 2 of the 1,034 lesions identified as negative by RCM proved to be false negatives on the basis of clinical changes within 1 year.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RCM was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively, with a positive predictive value of 70.3% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%.

The entire RCM procedure takes a skilled technician 15-20 minutes per lesion. As a practical matter, other investigators have estimated that RCM results in a cost savings of about $308,000 per million health plan members per year by reducing the need for biopsies (Dermatol Clin. 2016 Oct;34[4]:367-75).

In addition to evaluating clinically suspicious lesions, other situations in which RCM offers practical value include its use directly before the first cut during Mohs surgery in order to determine the margins of atypia; ex vivo imaging of Mohs margins, which has been shown to be comparable with frozen sections in accuracy but takes only one-third of the time; and imaging of biopsied lesions in order to determine the diagnosis relatively quickly, Dr. John noted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

CHICAGO – The future looks bright for to rule out malignancy, Ann M. John, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“With the advent of dermoscopy, dermatologists were able to elucidate both benign and malignant patterns to help further guide their decision to biopsy or not. This increased diagnostic accuracy of suspicious lesions by 30%, while reducing the benign to malignant ratio of biopsies performed from 18:1 to 4:1. However, there are still lesions that are equivocal on dermoscopy, as we all know, and for this, there’s reflectance confocal microscopy,” observed Dr. John, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

RCM is a device technology that’s been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration since 2008 for the imaging of clinically suspicious lesions. It employs laser scanning to assess the light-scattering properties of cells in the epidermis and dermis, generating images with resolution comparable to histology.

RCM took a back seat initially while American dermatologists were gradually coming to embrace dermoscopy, which their European colleagues had done years earlier. Now, with the availability of handheld RCM for use in the dermatology clinic, expect RCM to assume a growing role in daily practice.

To illustrate the power of RCM as a diagnostic aid, she presented a single-center retrospective study of 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions that were equivocal on dermoscopy and then assessed using RCM with 1 year of subsequent patient follow-up. Overall, 155 lesions were deemed positive for cancer or atypia by RCM, while 1,034 were determined to be benign. Of those 155, 46 lesions were considered false positives because of their benign appearance on histologic inspection of the biopsy sample. Only 2 of the 1,034 lesions identified as negative by RCM proved to be false negatives on the basis of clinical changes within 1 year.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RCM was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively, with a positive predictive value of 70.3% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%.

The entire RCM procedure takes a skilled technician 15-20 minutes per lesion. As a practical matter, other investigators have estimated that RCM results in a cost savings of about $308,000 per million health plan members per year by reducing the need for biopsies (Dermatol Clin. 2016 Oct;34[4]:367-75).

In addition to evaluating clinically suspicious lesions, other situations in which RCM offers practical value include its use directly before the first cut during Mohs surgery in order to determine the margins of atypia; ex vivo imaging of Mohs margins, which has been shown to be comparable with frozen sections in accuracy but takes only one-third of the time; and imaging of biopsied lesions in order to determine the diagnosis relatively quickly, Dr. John noted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

CHICAGO – The future looks bright for to rule out malignancy, Ann M. John, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

“With the advent of dermoscopy, dermatologists were able to elucidate both benign and malignant patterns to help further guide their decision to biopsy or not. This increased diagnostic accuracy of suspicious lesions by 30%, while reducing the benign to malignant ratio of biopsies performed from 18:1 to 4:1. However, there are still lesions that are equivocal on dermoscopy, as we all know, and for this, there’s reflectance confocal microscopy,” observed Dr. John, of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J.

RCM is a device technology that’s been cleared by the Food and Drug Administration since 2008 for the imaging of clinically suspicious lesions. It employs laser scanning to assess the light-scattering properties of cells in the epidermis and dermis, generating images with resolution comparable to histology.

RCM took a back seat initially while American dermatologists were gradually coming to embrace dermoscopy, which their European colleagues had done years earlier. Now, with the availability of handheld RCM for use in the dermatology clinic, expect RCM to assume a growing role in daily practice.

To illustrate the power of RCM as a diagnostic aid, she presented a single-center retrospective study of 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions that were equivocal on dermoscopy and then assessed using RCM with 1 year of subsequent patient follow-up. Overall, 155 lesions were deemed positive for cancer or atypia by RCM, while 1,034 were determined to be benign. Of those 155, 46 lesions were considered false positives because of their benign appearance on histologic inspection of the biopsy sample. Only 2 of the 1,034 lesions identified as negative by RCM proved to be false negatives on the basis of clinical changes within 1 year.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of RCM was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively, with a positive predictive value of 70.3% and a negative predictive value of 99.8%.

The entire RCM procedure takes a skilled technician 15-20 minutes per lesion. As a practical matter, other investigators have estimated that RCM results in a cost savings of about $308,000 per million health plan members per year by reducing the need for biopsies (Dermatol Clin. 2016 Oct;34[4]:367-75).

In addition to evaluating clinically suspicious lesions, other situations in which RCM offers practical value include its use directly before the first cut during Mohs surgery in order to determine the margins of atypia; ex vivo imaging of Mohs margins, which has been shown to be comparable with frozen sections in accuracy but takes only one-third of the time; and imaging of biopsied lesions in order to determine the diagnosis relatively quickly, Dr. John noted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The future looks bright for reflectance confocal microscopy in dermatology.

Major finding: The sensitivity and specificity of reflectance confocal microscopy for diagnosis of skin cancer in patients with equivocal dermoscopic findings was 98.2% and 99.8%, respectively.

Study details: This retrospective single center study included 1,189 clinically suspicious skin lesions with equivocal dermoscopy findings, which were then evaluated using reflectance confocal microscopy.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

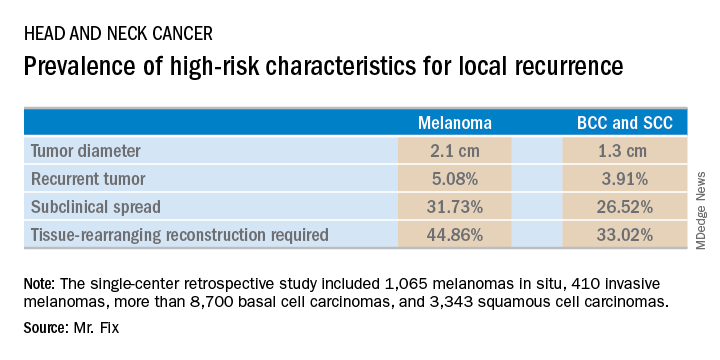

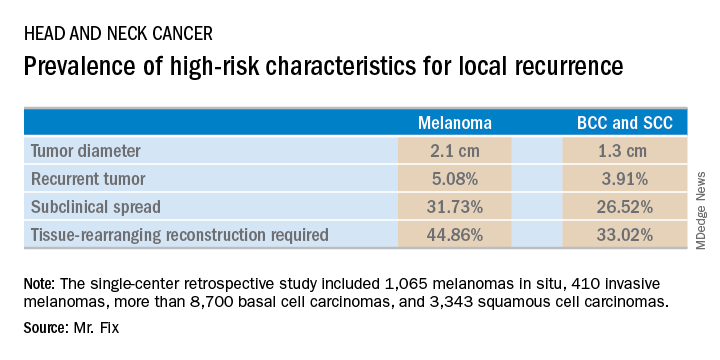

Mohs underutilized for melanoma of head and neck

CHICAGO – Contemporary national guidelines undervalue the benefits of Mohs micrographic surgery for patients with melanoma of the head and neck, William C. Fix asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

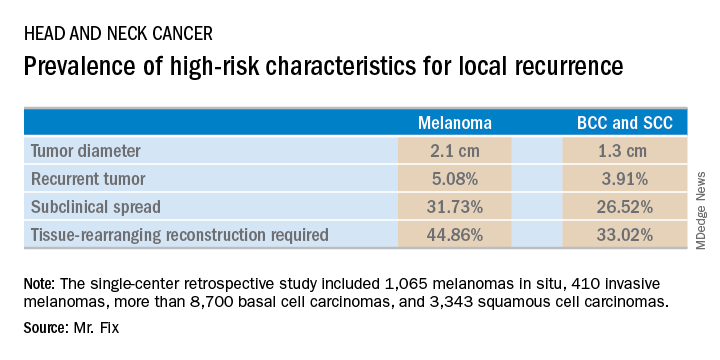

Mr. Fix, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, presented a single-center retrospective study of 13,644 cases of head and neck skin cancer treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for margin control. The cohort included 1,065 melanomas in situ, 410 invasive melanomas, more than 8,700 basal cell carcinomas, and 3,343 squamous cell carcinomas.

Mr. Fix and his coinvestigators undertook this observational study because they identified a gap in current guidelines for treatment of skin cancers of the head and neck. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends margin control at the time of primary surgery for BCCs and SCCs deemed at high risk for local recurrence and defines what those high-risk features are. For melanomas, however, the guidelines recommend wide local excision, even though that approach has roughly a 10% recurrence rate, compared with less than 1% for MMS.

Moreover, the 2012 appropriate use criteria for MMS put forth by the American Academy of Dermatology in concert with several other medical societies are unclear about invasive melanoma. As a result of this lack of guidance, the use of margin control in primary surgery for melanoma is applied in less than 4% of cases, according to Mr. Fix.

The University of Pennsylvania data he presented showed that melanomas of the head and neck were significantly more likely to be large in size, to be poorly defined, and to have other high-risk features for local recurrence than were the BCCs and SCCs. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for high-risk characteristics, melanomas were independently associated with a twofold increased likelihood of requiring flap reconstruction compared with BCCs and SCCs of the head and neck.

“We’ve shown that melanomas have high-risk features for local recurrence, possibly to a greater extent than BCCs and SCCs. These features help us triage resource use for BCC and SCC. Could these same features help us make decisions for melanomas?” he asked rhetorically.

Mr. Fix reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – Contemporary national guidelines undervalue the benefits of Mohs micrographic surgery for patients with melanoma of the head and neck, William C. Fix asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mr. Fix, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, presented a single-center retrospective study of 13,644 cases of head and neck skin cancer treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for margin control. The cohort included 1,065 melanomas in situ, 410 invasive melanomas, more than 8,700 basal cell carcinomas, and 3,343 squamous cell carcinomas.

Mr. Fix and his coinvestigators undertook this observational study because they identified a gap in current guidelines for treatment of skin cancers of the head and neck. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends margin control at the time of primary surgery for BCCs and SCCs deemed at high risk for local recurrence and defines what those high-risk features are. For melanomas, however, the guidelines recommend wide local excision, even though that approach has roughly a 10% recurrence rate, compared with less than 1% for MMS.

Moreover, the 2012 appropriate use criteria for MMS put forth by the American Academy of Dermatology in concert with several other medical societies are unclear about invasive melanoma. As a result of this lack of guidance, the use of margin control in primary surgery for melanoma is applied in less than 4% of cases, according to Mr. Fix.

The University of Pennsylvania data he presented showed that melanomas of the head and neck were significantly more likely to be large in size, to be poorly defined, and to have other high-risk features for local recurrence than were the BCCs and SCCs. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for high-risk characteristics, melanomas were independently associated with a twofold increased likelihood of requiring flap reconstruction compared with BCCs and SCCs of the head and neck.

“We’ve shown that melanomas have high-risk features for local recurrence, possibly to a greater extent than BCCs and SCCs. These features help us triage resource use for BCC and SCC. Could these same features help us make decisions for melanomas?” he asked rhetorically.

Mr. Fix reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – Contemporary national guidelines undervalue the benefits of Mohs micrographic surgery for patients with melanoma of the head and neck, William C. Fix asserted at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Mr. Fix, a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, presented a single-center retrospective study of 13,644 cases of head and neck skin cancer treated with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for margin control. The cohort included 1,065 melanomas in situ, 410 invasive melanomas, more than 8,700 basal cell carcinomas, and 3,343 squamous cell carcinomas.

Mr. Fix and his coinvestigators undertook this observational study because they identified a gap in current guidelines for treatment of skin cancers of the head and neck. For example, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends margin control at the time of primary surgery for BCCs and SCCs deemed at high risk for local recurrence and defines what those high-risk features are. For melanomas, however, the guidelines recommend wide local excision, even though that approach has roughly a 10% recurrence rate, compared with less than 1% for MMS.

Moreover, the 2012 appropriate use criteria for MMS put forth by the American Academy of Dermatology in concert with several other medical societies are unclear about invasive melanoma. As a result of this lack of guidance, the use of margin control in primary surgery for melanoma is applied in less than 4% of cases, according to Mr. Fix.

The University of Pennsylvania data he presented showed that melanomas of the head and neck were significantly more likely to be large in size, to be poorly defined, and to have other high-risk features for local recurrence than were the BCCs and SCCs. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis controlling for high-risk characteristics, melanomas were independently associated with a twofold increased likelihood of requiring flap reconstruction compared with BCCs and SCCs of the head and neck.

“We’ve shown that melanomas have high-risk features for local recurrence, possibly to a greater extent than BCCs and SCCs. These features help us triage resource use for BCC and SCC. Could these same features help us make decisions for melanomas?” he asked rhetorically.

Mr. Fix reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Margin control at the time of primary surgery for melanoma of the head and neck makes sense.

Major finding: Patients with a melanoma of the head and neck were twice as likely to require secondary flap reconstruction compared with patients with a basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Study details: A retrospective single-center study of 13,644 cases of skin cancer of the head and neck treated with Mohs surgery.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

ESMO scale offers guidance on cancer targets

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has published a proposed scale that would rank molecular targets for various cancers by how well they can be treated with new or emerging drugs.

The ESMO Scale of Clinical Actionability for Molecular Targets is designed to “harmonize and standardize the reporting and interpretation of clinically relevant genomics data,” according to Joaquin Mateo, MD, PhD, from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, and his fellow members of the ESMO Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group.

“A major challenge for oncologists in the clinic is to distinguish between findings that represent proven clinical value or potential value based on preliminary clinical or preclinical evidence from hypothetical gene-drug matches and findings that are currently irrelevant for clinical practice,” they wrote in Annals of Oncology.

The scale groups targets into one of six tiers based on levels of evidence ranging from the gold standard of prospective, randomized clinical trials to targets for which there are no evidence and only hypothetical actionability. The primary goal is to help oncologists assign priority to potential targets when they review results of gene-sequencing panels for individual patients, according to the developers.

Briefly, the six tiers are:

Tier I includes targets that are agreed to be suitable for routine use and a recommended specific drug when a specific molecular alteration is detected. Examples include trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer, and inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in patients with non–small cell lung cancer positive for EGFR mutations.

Tier II includes “investigational targets that likely define a patient population that benefits from a targeted drug but additional data are needed.” This tier includes agents that work in the phosphatidylinostiol 3-kinase pathway.

Tier III is similar to Tier II, in that it includes investigational targets that define a patient population with proven benefit from a targeted therapy, but in this case the target is detected in a different tumor type that has not previously been studied. For example, the targeted agent vemurafenib (Zelboraf), which extends survival of patients with metastatic melanomas carrying the BRAF V600E mutation, has only limited activity against BRAF-mutated colorectal cancers.

Tier IV includes targets with preclinical evidence of actionability.

Tier V includes targets with “evidence of relevant antitumor activity, not resulting in clinical meaningful benefit as single treatment but supporting development of cotargeting approaches.” The authors cite the example of PIK3CA inhibitors in patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers who also have PIK3CA activating mutations. In clinical trials, this strategy led to objective responses but not change outcomes.

The final tier is not Tier VI, as might be expected, but Tier X, with the X in this case being the unknown – that is, alterations/mutations for which there is neither preclinical nor clinical evidence to support their hypothetical use as a drug target.

“This clinical benefit–centered classification system offers a common language for all the actors involved in clinical cancer drug development. Its implementation in sequencing reports, tumor boards, and scientific communication can enable precise treatment decisions and facilitate discussions with patients about novel therapeutic options,” Dr. Mateo and his associates wrote in their conclusion.

The development process was supported by ESMO. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies as well as grants/support from other foundations or charities.

SOURCE: Mateo J et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263.

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has published a proposed scale that would rank molecular targets for various cancers by how well they can be treated with new or emerging drugs.

The ESMO Scale of Clinical Actionability for Molecular Targets is designed to “harmonize and standardize the reporting and interpretation of clinically relevant genomics data,” according to Joaquin Mateo, MD, PhD, from the Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, Spain, and his fellow members of the ESMO Translational Research and Precision Medicine Working Group.

“A major challenge for oncologists in the clinic is to distinguish between findings that represent proven clinical value or potential value based on preliminary clinical or preclinical evidence from hypothetical gene-drug matches and findings that are currently irrelevant for clinical practice,” they wrote in Annals of Oncology.

The scale groups targets into one of six tiers based on levels of evidence ranging from the gold standard of prospective, randomized clinical trials to targets for which there are no evidence and only hypothetical actionability. The primary goal is to help oncologists assign priority to potential targets when they review results of gene-sequencing panels for individual patients, according to the developers.

Briefly, the six tiers are:

Tier I includes targets that are agreed to be suitable for routine use and a recommended specific drug when a specific molecular alteration is detected. Examples include trastuzumab for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer, and inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in patients with non–small cell lung cancer positive for EGFR mutations.

Tier II includes “investigational targets that likely define a patient population that benefits from a targeted drug but additional data are needed.” This tier includes agents that work in the phosphatidylinostiol 3-kinase pathway.

Tier III is similar to Tier II, in that it includes investigational targets that define a patient population with proven benefit from a targeted therapy, but in this case the target is detected in a different tumor type that has not previously been studied. For example, the targeted agent vemurafenib (Zelboraf), which extends survival of patients with metastatic melanomas carrying the BRAF V600E mutation, has only limited activity against BRAF-mutated colorectal cancers.

Tier IV includes targets with preclinical evidence of actionability.

Tier V includes targets with “evidence of relevant antitumor activity, not resulting in clinical meaningful benefit as single treatment but supporting development of cotargeting approaches.” The authors cite the example of PIK3CA inhibitors in patients with estrogen receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancers who also have PIK3CA activating mutations. In clinical trials, this strategy led to objective responses but not change outcomes.

The final tier is not Tier VI, as might be expected, but Tier X, with the X in this case being the unknown – that is, alterations/mutations for which there is neither preclinical nor clinical evidence to support their hypothetical use as a drug target.

“This clinical benefit–centered classification system offers a common language for all the actors involved in clinical cancer drug development. Its implementation in sequencing reports, tumor boards, and scientific communication can enable precise treatment decisions and facilitate discussions with patients about novel therapeutic options,” Dr. Mateo and his associates wrote in their conclusion.

The development process was supported by ESMO. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with various companies as well as grants/support from other foundations or charities.

SOURCE: Mateo J et al. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy263.

The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) has published a proposed scale that would rank molecular targets for various cancers by how well they can be treated with new or emerging drugs.