User login

Cross-contamination of Pathology Specimens: A Cautionary Tale

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

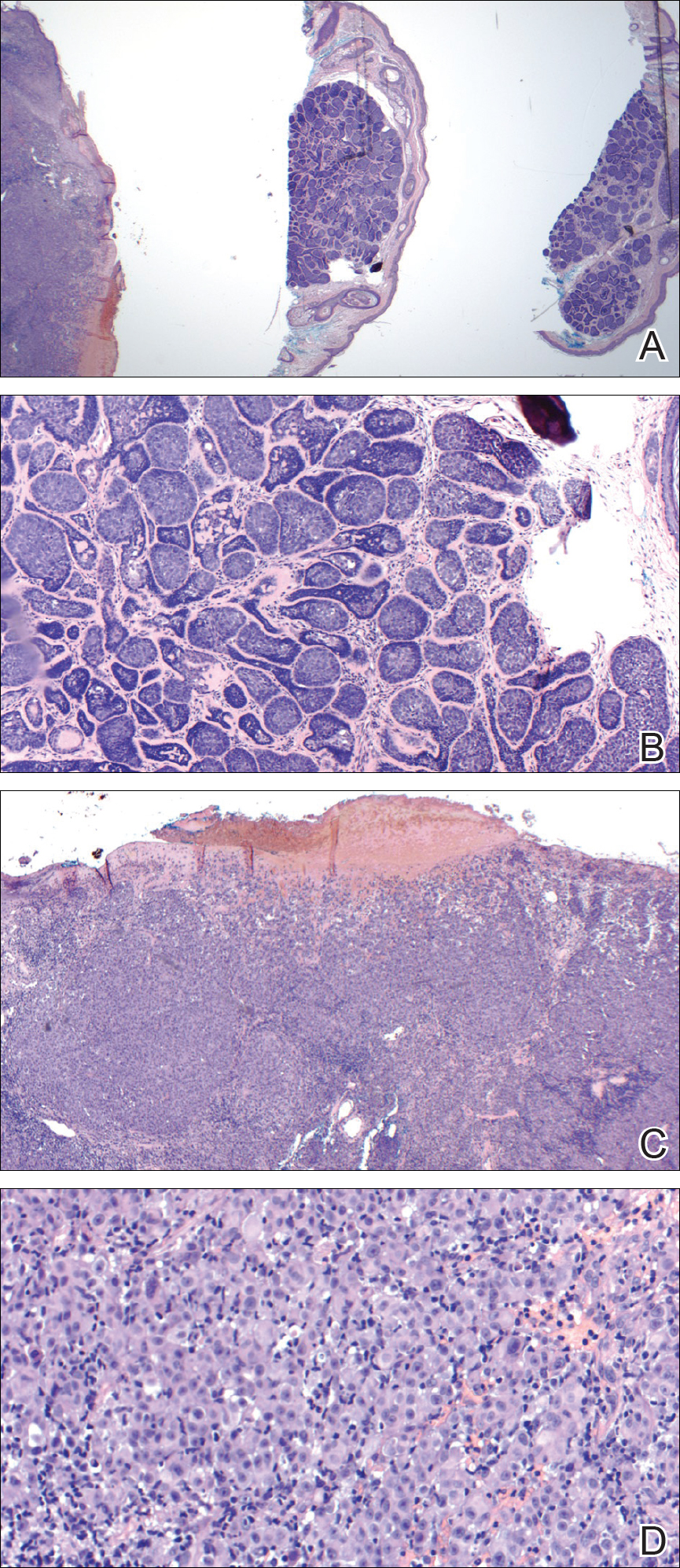

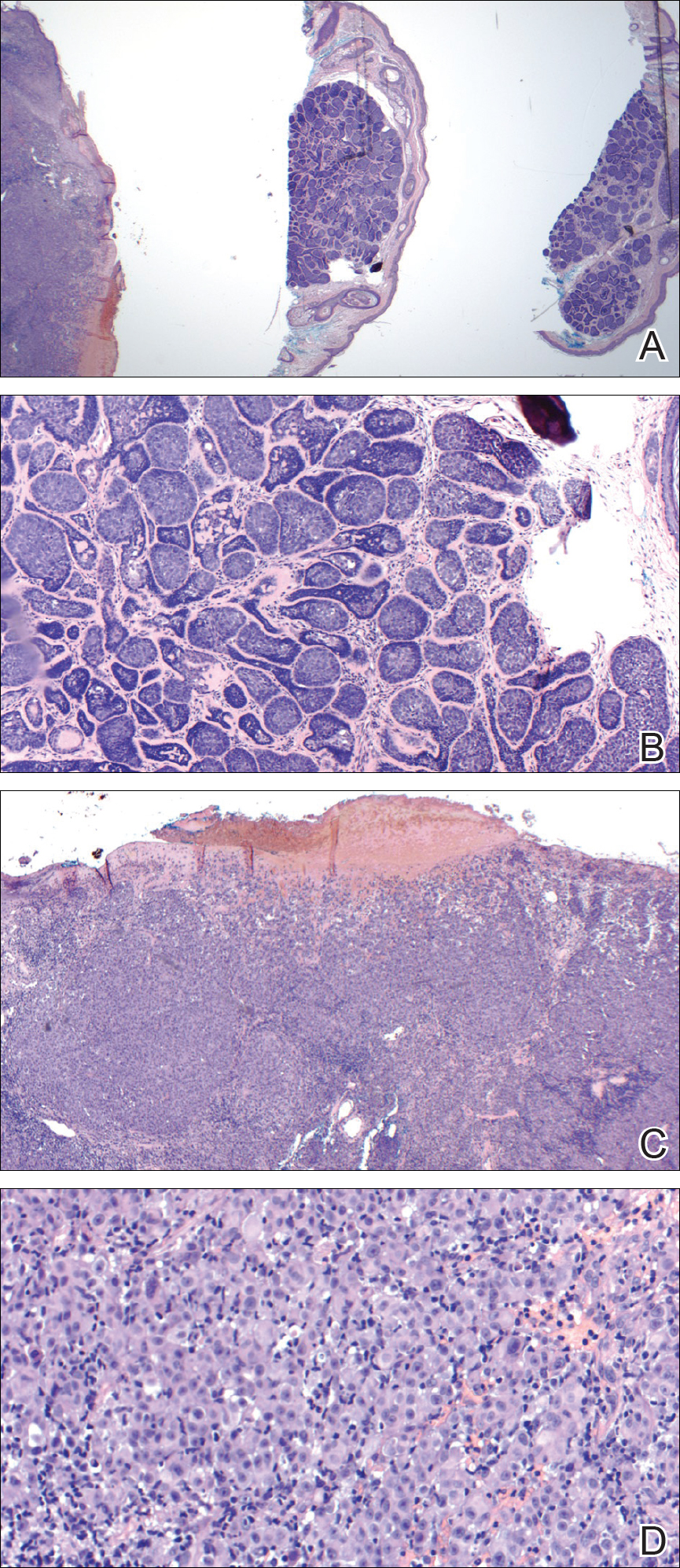

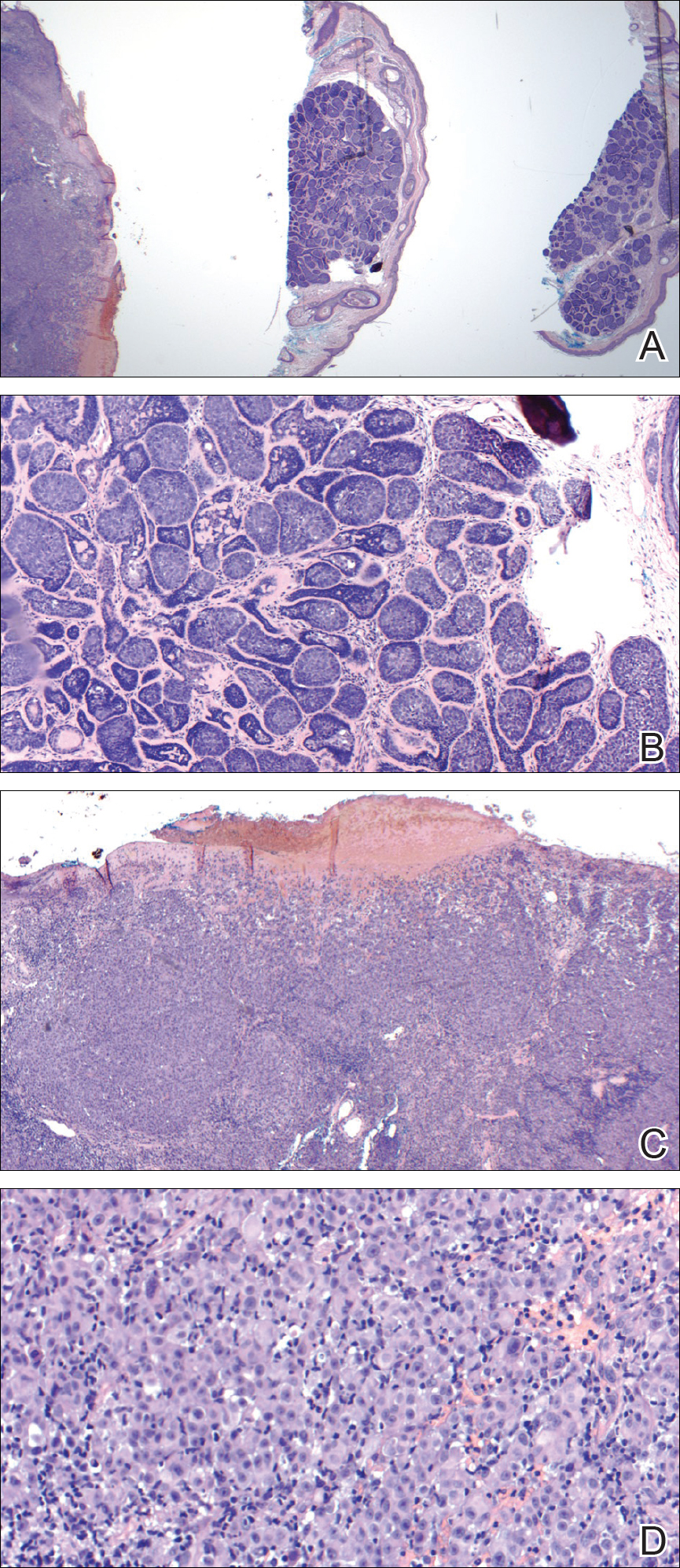

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

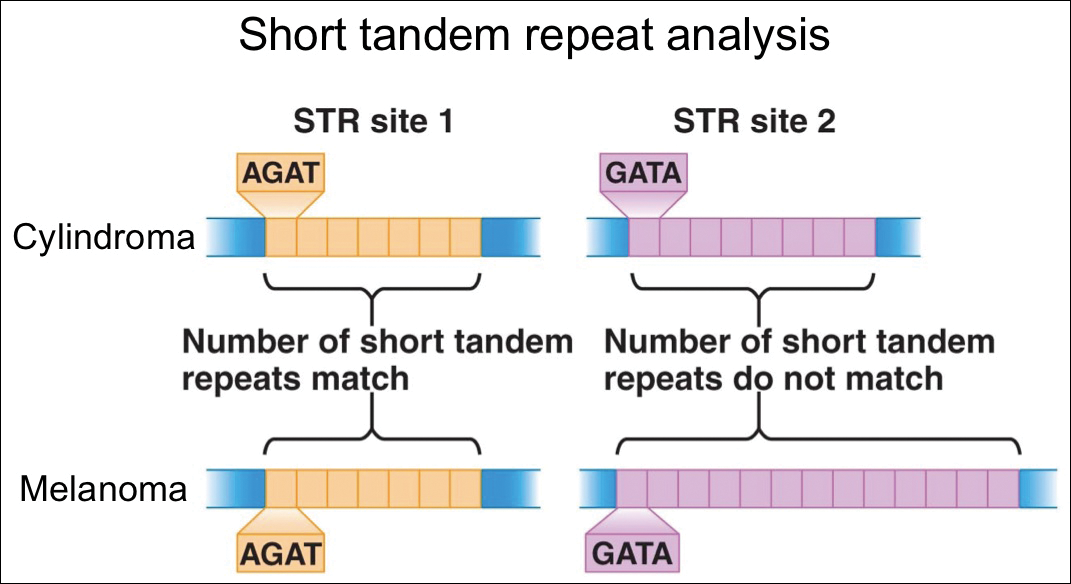

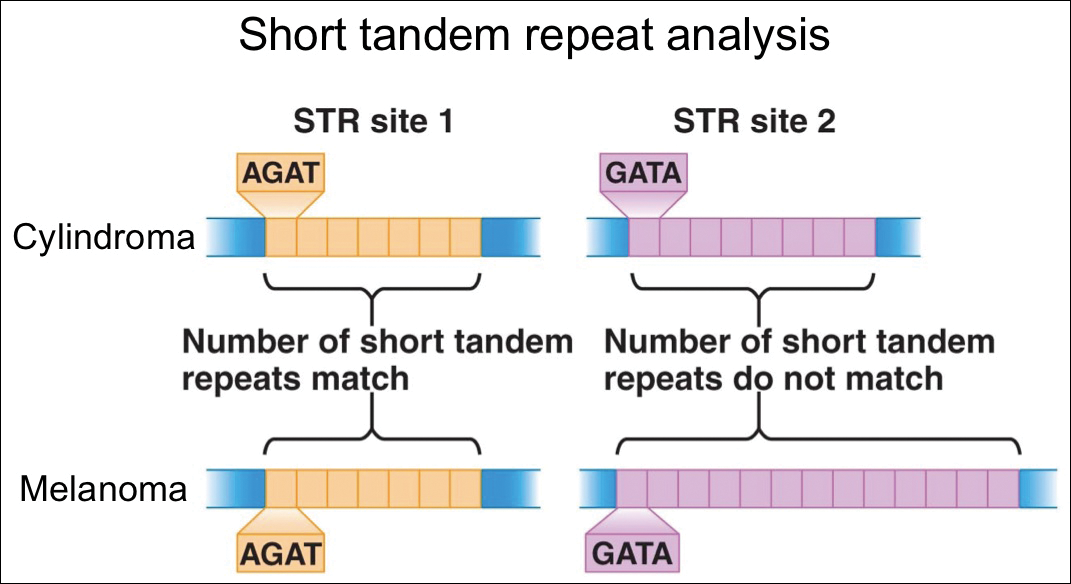

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

Resident Pearl

- Although cross-contamination of pathology specimens is rare, it does occur and can impact diagnosis and management if detected early.

Which Patients Have the Best Chance With Checkpoint Inhibitors?

Checkpoint inhibitors are so new that not enough patients have received them to allow clinicians to predict who will benefit most. But researchers from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Institute; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and University of Maryland in College Park may have found a clue: A gene expression predictor.

They began by looking at neuroblastoma cases where the immune system seemed to mount “an unprompted, successful immune response” to cancer, causing spontaneous tumor regression. The researchers were able to define gene expression features that separated regressing from nonregressing disease.

The researchers then computed Immuno-PREdictive Scores (IMPRES) for each patient sample. The higher the score, the more likely was spontaneous regression. Analyzing 297 samples from several studies, they found the predictor identified nearly all patients who responded to the inhibitors and more than half of those who did not. “Importantly,” the researchers say, their predictor was accurate across many different melanoma patient datasets.

Checkpoint inhibitors are so new that not enough patients have received them to allow clinicians to predict who will benefit most. But researchers from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Institute; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and University of Maryland in College Park may have found a clue: A gene expression predictor.

They began by looking at neuroblastoma cases where the immune system seemed to mount “an unprompted, successful immune response” to cancer, causing spontaneous tumor regression. The researchers were able to define gene expression features that separated regressing from nonregressing disease.

The researchers then computed Immuno-PREdictive Scores (IMPRES) for each patient sample. The higher the score, the more likely was spontaneous regression. Analyzing 297 samples from several studies, they found the predictor identified nearly all patients who responded to the inhibitors and more than half of those who did not. “Importantly,” the researchers say, their predictor was accurate across many different melanoma patient datasets.

Checkpoint inhibitors are so new that not enough patients have received them to allow clinicians to predict who will benefit most. But researchers from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Institute; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and University of Maryland in College Park may have found a clue: A gene expression predictor.

They began by looking at neuroblastoma cases where the immune system seemed to mount “an unprompted, successful immune response” to cancer, causing spontaneous tumor regression. The researchers were able to define gene expression features that separated regressing from nonregressing disease.

The researchers then computed Immuno-PREdictive Scores (IMPRES) for each patient sample. The higher the score, the more likely was spontaneous regression. Analyzing 297 samples from several studies, they found the predictor identified nearly all patients who responded to the inhibitors and more than half of those who did not. “Importantly,” the researchers say, their predictor was accurate across many different melanoma patient datasets.

Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab shows promise in advanced solid tumors

Epacadostat, a highly selective oral inhibitor of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) enzyme, was well tolerated when combined with pembrolizumab and demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity in multiple types of advanced solid tumors, according to the results of a phase l/ll trial.

Tumors may evade immunosurveillance through upregulation of the IDO1 enzyme, and thus there is a great interest in developing combination therapies that can target various immune evasion pathways to improve therapeutic response and outcomes. In this study, the authors evaluated the investigational agent epacadostat combined with pembrolizumab in 62 patients with advanced solid tumors.

In the dose escalation phase, patents received increasing doses of oral epacadostat (25, 50, 100, or 300 mg) twice per day plus intravenous pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg or 200 mg every 3 weeks. During the safety expansion, epacadostat at 50, 100, or 300 mg was given twice per day, plus pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks. The maximum tolerated dose of epacadostat in combination with pembrolizumab was not reached.

Objective responses (per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] version 1.1) occurred in 12 (55%) of 22 patients with melanoma and in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, reported Tara C. Mitchell, MD, of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The authors observed that there was antitumor activity at all epacadostat doses and in several tumor types. A complete response was achieved by 8 patients (treatment naive melanoma [5 patients] and previously treated for advanced/ metastatic melanoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma [EA], or urothelial carcinoma [UC] [1 patient each]), while 17 patients achieved a partial response (treatment-naive melanoma [6 patients], non–small cell lung cancer [NSCLC] [5 patients], renal cell carcinoma [RCC] and UC [2 patients each], and EA and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [1 patient each]).

Most patients (n = 52, 84%) experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), the most frequently observed being fatigue (36%), rash (36%), arthralgia (24%), pruritus (23%), and nausea (21%). Grade 3/4 TRAEs occurred in 24% of patients, and 7 patients (11%) discontinued their treatment because of TRAEs. There were no deaths associated with TRAEs.

“The safety profile observed with epacadostat plus pembrolizumab compares favorably with studies of other combination immunotherapies,” wrote Dr. Mitchell and her colleagues. “Although not powered to evaluate efficacy, the phase I portion of this study showed that epacadostat plus pembrolizumab had encouraging and durable antitumor activity,” they said.

SOURCE: Mitchell TC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9602.

Epacadostat, a highly selective oral inhibitor of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) enzyme, was well tolerated when combined with pembrolizumab and demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity in multiple types of advanced solid tumors, according to the results of a phase l/ll trial.

Tumors may evade immunosurveillance through upregulation of the IDO1 enzyme, and thus there is a great interest in developing combination therapies that can target various immune evasion pathways to improve therapeutic response and outcomes. In this study, the authors evaluated the investigational agent epacadostat combined with pembrolizumab in 62 patients with advanced solid tumors.

In the dose escalation phase, patents received increasing doses of oral epacadostat (25, 50, 100, or 300 mg) twice per day plus intravenous pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg or 200 mg every 3 weeks. During the safety expansion, epacadostat at 50, 100, or 300 mg was given twice per day, plus pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks. The maximum tolerated dose of epacadostat in combination with pembrolizumab was not reached.

Objective responses (per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] version 1.1) occurred in 12 (55%) of 22 patients with melanoma and in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, reported Tara C. Mitchell, MD, of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The authors observed that there was antitumor activity at all epacadostat doses and in several tumor types. A complete response was achieved by 8 patients (treatment naive melanoma [5 patients] and previously treated for advanced/ metastatic melanoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma [EA], or urothelial carcinoma [UC] [1 patient each]), while 17 patients achieved a partial response (treatment-naive melanoma [6 patients], non–small cell lung cancer [NSCLC] [5 patients], renal cell carcinoma [RCC] and UC [2 patients each], and EA and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [1 patient each]).

Most patients (n = 52, 84%) experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), the most frequently observed being fatigue (36%), rash (36%), arthralgia (24%), pruritus (23%), and nausea (21%). Grade 3/4 TRAEs occurred in 24% of patients, and 7 patients (11%) discontinued their treatment because of TRAEs. There were no deaths associated with TRAEs.

“The safety profile observed with epacadostat plus pembrolizumab compares favorably with studies of other combination immunotherapies,” wrote Dr. Mitchell and her colleagues. “Although not powered to evaluate efficacy, the phase I portion of this study showed that epacadostat plus pembrolizumab had encouraging and durable antitumor activity,” they said.

SOURCE: Mitchell TC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9602.

Epacadostat, a highly selective oral inhibitor of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) enzyme, was well tolerated when combined with pembrolizumab and demonstrated encouraging antitumor activity in multiple types of advanced solid tumors, according to the results of a phase l/ll trial.

Tumors may evade immunosurveillance through upregulation of the IDO1 enzyme, and thus there is a great interest in developing combination therapies that can target various immune evasion pathways to improve therapeutic response and outcomes. In this study, the authors evaluated the investigational agent epacadostat combined with pembrolizumab in 62 patients with advanced solid tumors.

In the dose escalation phase, patents received increasing doses of oral epacadostat (25, 50, 100, or 300 mg) twice per day plus intravenous pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg or 200 mg every 3 weeks. During the safety expansion, epacadostat at 50, 100, or 300 mg was given twice per day, plus pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks. The maximum tolerated dose of epacadostat in combination with pembrolizumab was not reached.

Objective responses (per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] version 1.1) occurred in 12 (55%) of 22 patients with melanoma and in patients with non–small-cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma, urothelial carcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, reported Tara C. Mitchell, MD, of the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues. The report is in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The authors observed that there was antitumor activity at all epacadostat doses and in several tumor types. A complete response was achieved by 8 patients (treatment naive melanoma [5 patients] and previously treated for advanced/ metastatic melanoma, endometrial adenocarcinoma [EA], or urothelial carcinoma [UC] [1 patient each]), while 17 patients achieved a partial response (treatment-naive melanoma [6 patients], non–small cell lung cancer [NSCLC] [5 patients], renal cell carcinoma [RCC] and UC [2 patients each], and EA and squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [1 patient each]).

Most patients (n = 52, 84%) experienced treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), the most frequently observed being fatigue (36%), rash (36%), arthralgia (24%), pruritus (23%), and nausea (21%). Grade 3/4 TRAEs occurred in 24% of patients, and 7 patients (11%) discontinued their treatment because of TRAEs. There were no deaths associated with TRAEs.

“The safety profile observed with epacadostat plus pembrolizumab compares favorably with studies of other combination immunotherapies,” wrote Dr. Mitchell and her colleagues. “Although not powered to evaluate efficacy, the phase I portion of this study showed that epacadostat plus pembrolizumab had encouraging and durable antitumor activity,” they said.

SOURCE: Mitchell TC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9602.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab showed antitumor activity and tolerability in patients with advanced solid tumors.

Major finding: Among 62 patients, 25 achieved an objective response.

Study details: Phase l/ll clinical trial of 62 patients with advanced solid tumors.

Disclosures: Incyte and Merck funded the study. All of the authors have disclosed relationships with industry, including the study sponsor.

Source: Mitchell TC et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Sep 28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9602.

Xanthogranulomatous Reaction to Trametinib for Metastatic Malignant Melanoma

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

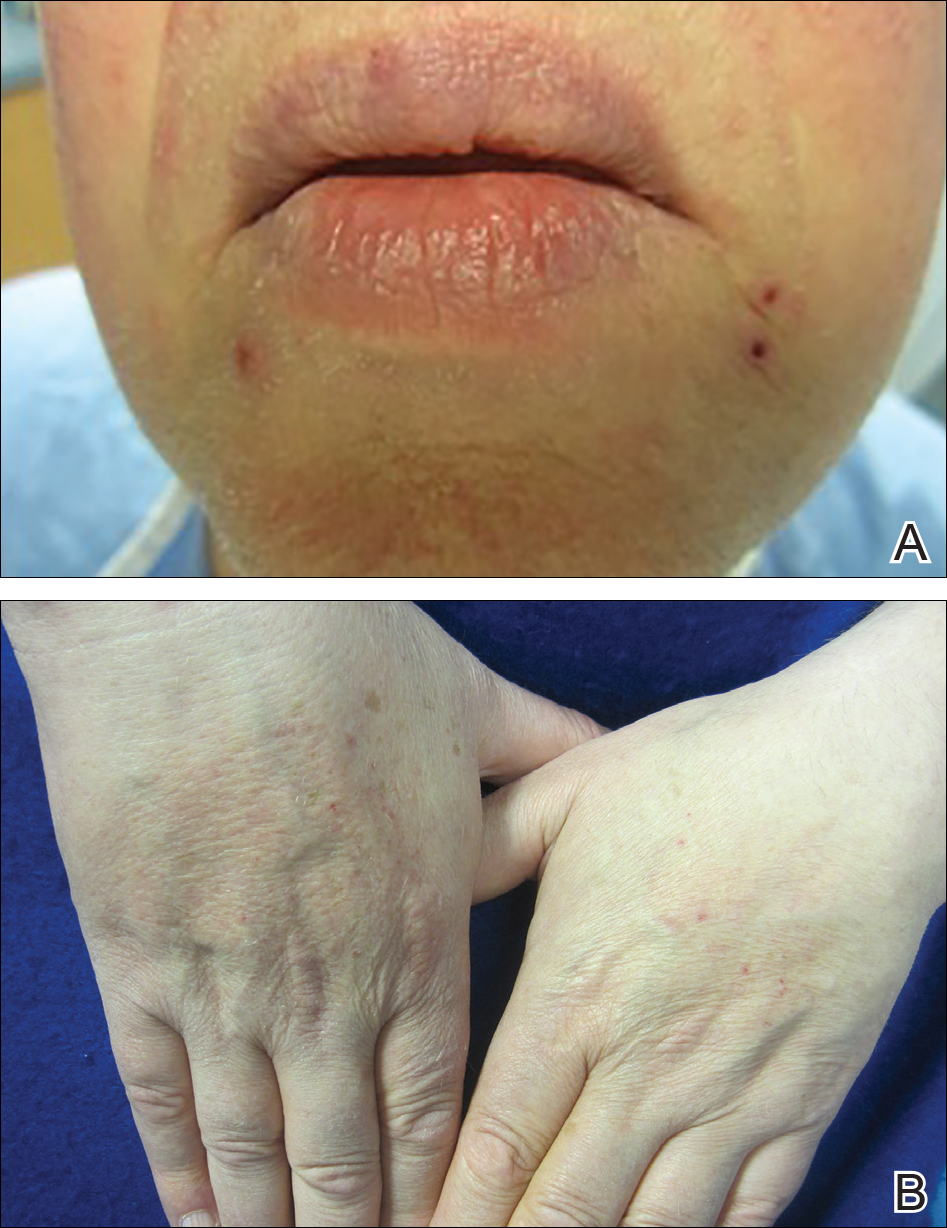

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

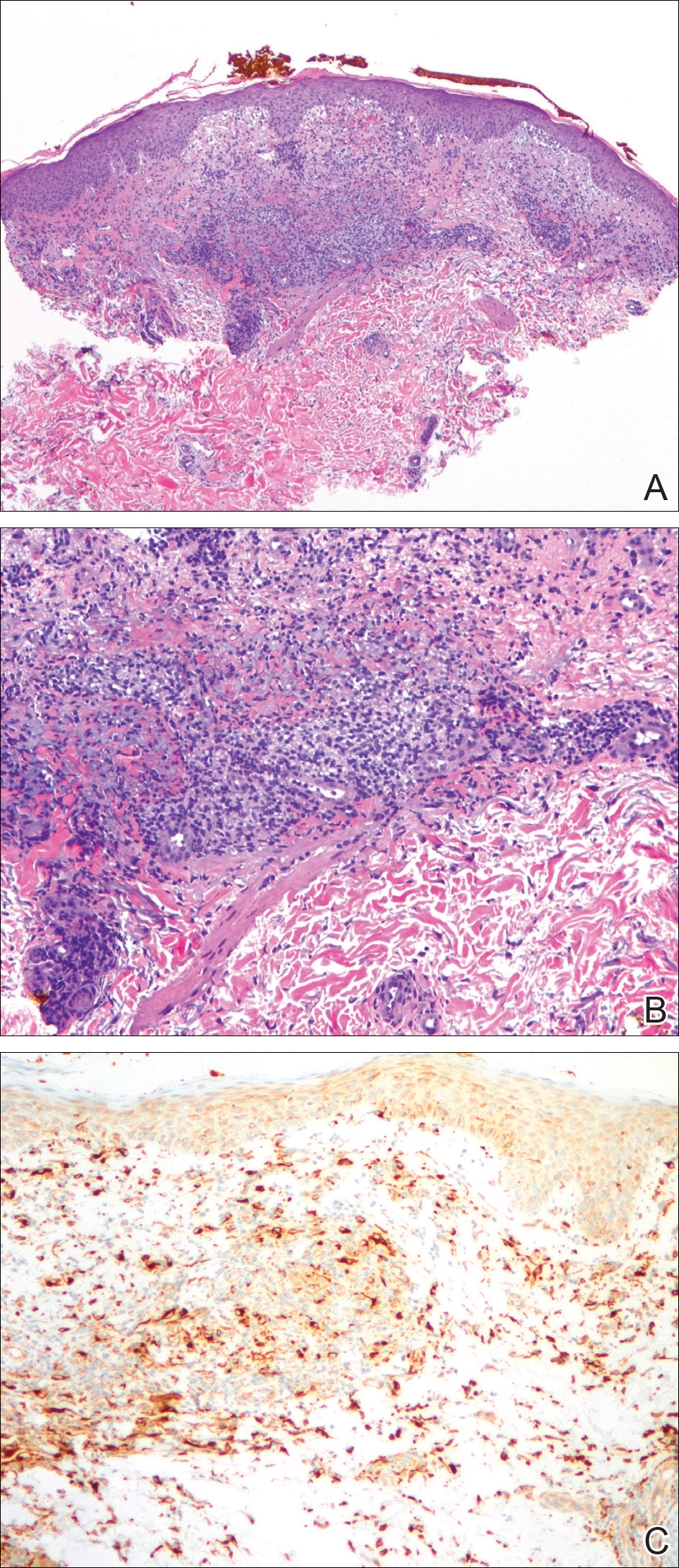

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

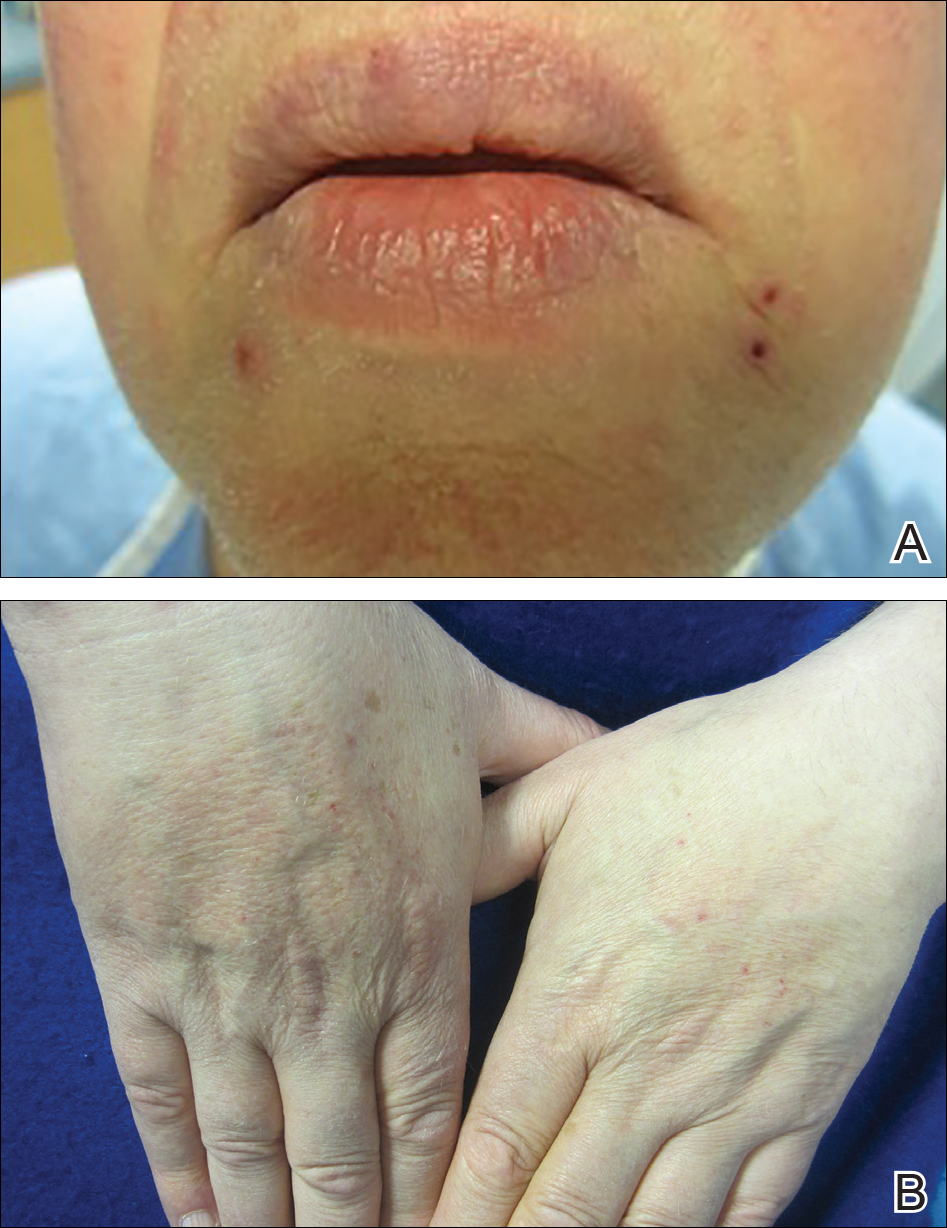

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

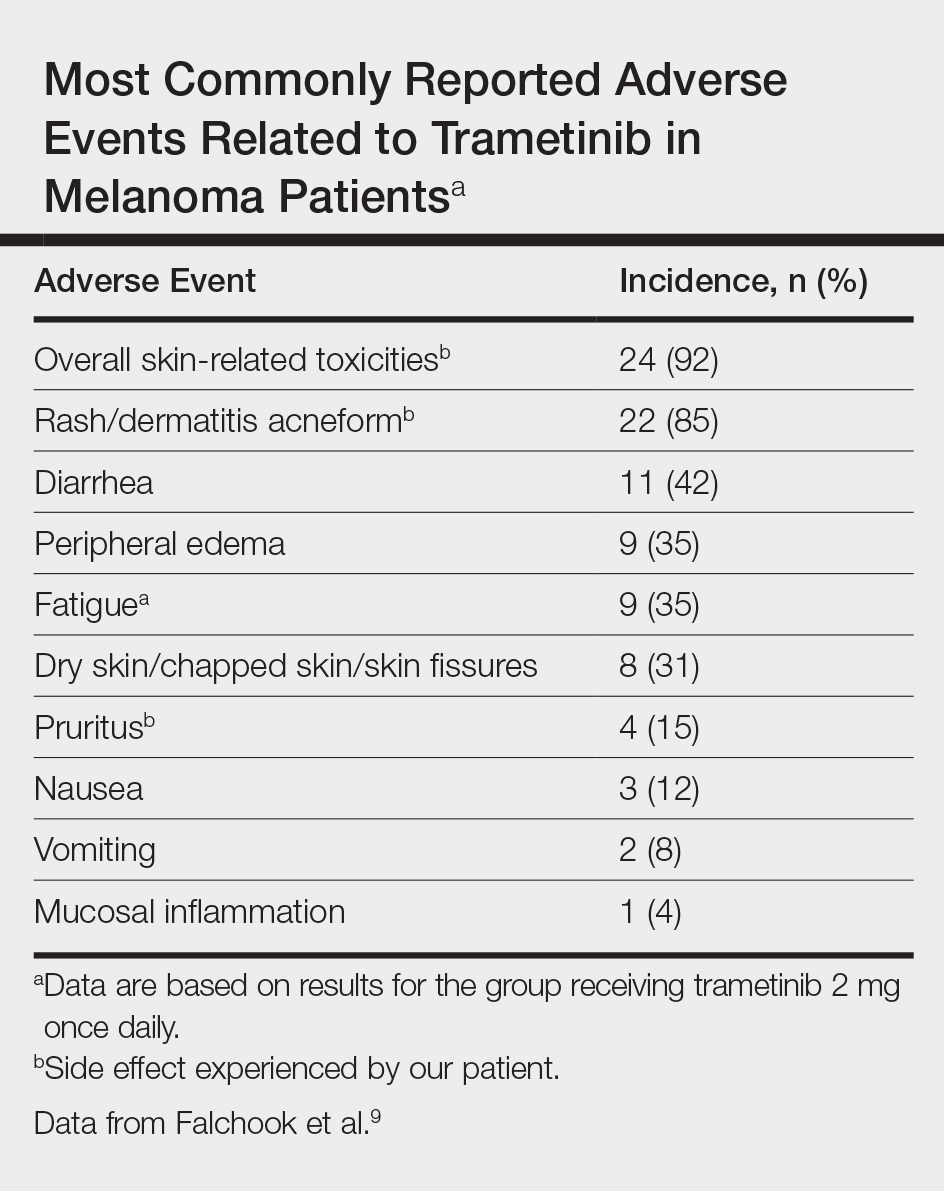

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

A decade ago, the few agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of metastatic melanoma demonstrated low therapeutic success rates (ie, <15%–20%).1 Since then, advances in molecular biology have identified oncogenes that contribute to melanoma progression.2 Inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by targeting mutant BRAF and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MEK) has created promising pharmacologic treatment opportunities.3 Due to the recent US Food and Drug Administration approval of these therapies for treatment of melanoma, it is important to better characterize these adverse events (AEs) so that we can manage them. We present the development of an unusual cutaneous reaction to trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, in a man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma.

Case Report

A 66-year-old man with stage IV M1b malignant melanoma with metastases to the brain and lungs presented with recurring pruritic erythematous papules on the face and bilateral forearms that began shortly after initiating therapy with trametinib. The cutaneous eruption had initially presented on the face, forearms, and dorsal hands when trametinib was used in combination with vemurafenib, a BRAF inhibitor, and ipilimumab, a human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4–blocking antibody; however, lesions initially were minimal and self-resolving. When trametinib was reintroduced as monotherapy due to fever attributed to the combination treatment regimen, the cutaneous eruption recurred more severely. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly papules limited to the face and bilateral upper extremities, including the flexural surfaces.

A biopsy from the flexural surface of the right forearm revealed a dense perivascular lymphoid and xanthomatous infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 1). Poorly formed granulomas within the mid reticular dermis demonstrated focal palisading of histiocytes with prominent giant cells at the periphery. Histiocytes and giant cells showed foamy or xanthomatous cytoplasm. Within the reaction, degenerative and swollen collagen fibers were noted with no mucin deposition, which was confirmed with negative colloidal iron staining.

Brief cessation of trametinib along with application of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% resulted in resolution of the cutaneous eruption. Later, trametinib was reintroduced in combination with vemurafenib, though therapy was intermittently discontinued due to various side effects. Skin lesions continued to recur (Figure 2) while the patient was on trametinib but remained minimal and continued to respond to topical clobetasol propionate. One year later, the patient continues to tolerate combination therapy with trametinib and vemurafenib.

Comment

BRAF Inhibitors

Normally, activated BRAF phosphorylates and stimulates MEK proteins, ultimately influencing cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation.3-5 BRAF mutations that constitutively activate this pathway have been detected in several malignancies, including papillary thyroid cancer, colorectal cancer, and brain tumors, but they are particularly prevalent in melanoma.4,6 The majority of BRAF-positive malignant melanomas are associated with V600E, in which valine is substituted for glutamic acid at codon 600. The next most common BRAF mutation is V600K, in which valine is substituted for lysine.2,7 Together these constitute approximately 95% of BRAF mutations in melanoma patients.5

MEK Inhibitors

Initially, BRAF inhibitors (BRAFi) were introduced to the market for treating melanoma with great success; however, resistance to BRAFi therapy quickly was identified within months of initiating therapy, leading to investigations for combination therapy with MEK inhibitors (MEKi).2,5 MEK inhibition decreases cellular proliferation and also leads to apoptosis of melanoma cells in patients with BRAF V600E or V600K mutations.2,8 Trametinib, in particular, is a reversible, highly selective allosteric inhibitor of both MEK1 and MEK2. While on trametinib, patients with metastatic melanoma have experienced 3 times as long progression-free survival as well as 81% overall survival compared to 67% overall survival at 6 months in patients on chemotherapy, dacarbazine, or paclitaxel.5 However, AEs are quite common with trametinib, with cutaneous AEs being a leading side effect. Several large trials have reported that 57% to 92% of patients on trametinib report cutaneous AEs, with the majority of cases being described as papulopustular or acneform (Table).5,9

Combination Therapy

Fortunately, combination treatment with a BRAFi may alleviate MEKi-induced cutaneous drug reactions. In one study, acneform eruptions were identified in only 10% of those on combination therapy—trametinib with the BRAFi dabrafenib—compared to 77% of patients on trametinib monotherapy.10 Strikingly, cutaneous AEs occurred in 100% of trametinib-treated mice compared to 30% of combination-treated mice in another study, while the benefits of MEKi remained similar in both groups.11 Because BRAFi and MEKi combination therapy improves progression-free survival while minimizing AEs, we support the use of combination therapy instead of BRAFi or MEKi monotherapy.5

Histologic Evidence of AEs

Histology of trametinib-associated cutaneous reactions is not well characterized, which is in contrast to our understanding of cutaneous AEs associated with BRAFi in which transient acantholytic dermatosis (seen in 45% of patients) and verrucal keratosis (seen in 18% of patients) have been well characterized on histology.12 Interestingly, cutaneous granulomatous eruptions have been attributed to BRAFi therapy in 4 patients.13,14 One patient was on monotherapy with vemurafenib and granulomatous dermatitis with focal necrosis was seen on histology.13 The other 3 patients were on combination therapy with trametinib; 2 had histology-proven sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation, and 1 demonstrated perifollicular granulomatous inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding a focus of melanoma cells.13,14 Although these granulomatous reactions were attributed to BRAFi or combination therapy, the association with trametinib remains unclear. On the other hand, our patient’s granulomatous reaction was exacerbated on trametinib monotherapy, suggesting a relationship to trametinib itself rather than BRAFi.

Conclusion

With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAFi and MEKi therapies provide major milestones in metastatic melanoma management. As more patients are treated with these agents, it is important that we better characterize their associated side effects. Our case of an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction to trametinib adds to the knowledge base of possible cutaneous reactions caused by this drug. We hope that prospective studies will further investigate and differentiate the cutaneous AEs described so that we can better manage these patients.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

- Eggermont AM, Schadendorf D. Melanoma and immunotherapy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23:547-564.

- Chung C, Reilly S. Trametinib: a novel signal transduction inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:101-110.

- Montagut C, Settleman J. Targeting the RAF-MEK-ERK pathway in cancer therapy [published online February 12, 2009]. Cancer Lett. 2009;283:125-134.

- Hertzman Johansson C, Egyhazi Brage S. BRAF inhibitors in cancer therapy [published online December 8, 2013]. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;142:176-182.

- Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al; METRIC Study Group. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma [published online June 4, 2012]. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:107-114.

- Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer [published online June 9, 2002]. Nature. 2002;417:949-954.

- Houben R, Becker JC, Kappel A, et al. Constitutive activation of the Ras-Raf signaling pathway in metastatic melanoma is associated with poor prognosis. J Carcinog. 2004;3:6.

- Roberts PF, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291-3310.

- Falchook GS, Lewis KD, Infante JR, et al. Activity of the oral MEK inhibitor trametinib in patients with advanced melanoma: a phase 2 dose-escalation trial [published online July 16, 2012]. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:782-789.

- Anforth R, Liu M, Nguyen B, et al. Acneiform eruptions: a common cutaneous toxicity of the MEK inhibitor trametinib [published online December 9, 2013]. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:250-254.

- Gadiot J, Hooijkaas AI, Deken MA, et al. Synchronous BRAF(V600E) and MEK inhibition leads to superior control of murine melanoma by limiting MEK inhibitor induced skin toxicity. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1649-1658.

- Anforth R, Carlos G, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in patients treated with BRAF inhibitor-based therapies for metastatic melanoma for longer than 52 weeks [published online November 21, 2014]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:239-243.

- Park JJ, Hawryluk EB, Tahan SR, et al. Cutaneous granulomatous eruption and successful response to potent topical steroids in patients undergoing targeted BRAF inhibitor treatment for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:307-311.

- Green JS, Norris DA, Wisell K. Novel cutaneous effects of combination chemotherapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors: a report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:172-176.

Practice Points

- With the discovery of molecular targeting in melanoma, BRAF and MEK inhibitors have been increasingly utilized as therapies in metastatic melanoma management.

- Trametinib, a MEK inhibitor, is commonly associated with cutaneous adverse reactions, particularly acneform eruptions.

- We report a patient on trametinib who developed an eruption with an unusual xanthogranulomatous reaction pattern noted on histology.

Mobile App Rankings in Dermatology

As technology continues to advance, so too does its accessibility to the general population. In 2013, 56% of Americans owned a smartphone versus 77% in 2017.1With the increase in mobile applications (apps) available, it is no surprise that the market has extended into the medical field, with dermatology being no exception.2 The majority of dermatology apps can be classified as teledermatology apps, followed by self-surveillance, disease guide, and reference apps. Additional types of dermatology apps include dermoscopy, conference, education, photograph storage and sharing, and journal apps, and others.2 In this study, we examined Apple App Store rankings to determine the types of dermatology apps that are most popular among patients and physicians.

METHODS

A popular app rankings analyzer (App Annie) was used to search for dermatology apps along with their App Store rankings.3 Although iOS is not the most popular mobile device operating system, we chose to evaluate app rankings via the App Store because iPhones are the top-selling individual phones of any kind in the United States.4

We performed our analysis on a single day (July 14, 2018) given that app rankings can change daily. We incorporated the following keywords, which were commonly used in other dermatology app studies: dermatology, psoriasis, rosacea, acne, skin cancer, melanoma, eczema, and teledermatology. The category ranking was defined as the rank of a free or paid app in the App Store’s top charts for the selected country (United States), market (Apple), and device (iPhone) within their app category (Medical). Inclusion criteria required a ranking in the top 1500 Medical apps and being categorized in the App Store as a Medical app. Exclusion criteria included apps that focused on cosmetics, private practice, direct advertisements, photograph editing, or claims to cure skin disease, as well as non–English-language apps. The App Store descriptions were assessed to determine the type of each app (eg, teledermatology, disease guide) and target audience (patient, physician, or both).

Another search was performed using the same keywords but within the Health and Fitness category to capture potentially more highly ranked apps among patients. We also conducted separate searches within the Medical category using the keywords billing, coding, and ICD (International Classification of Diseases) to evaluate rankings for billing/coding apps, as well as EMR and electronic medical records for electronic medical record (EMR) apps.

RESULTS

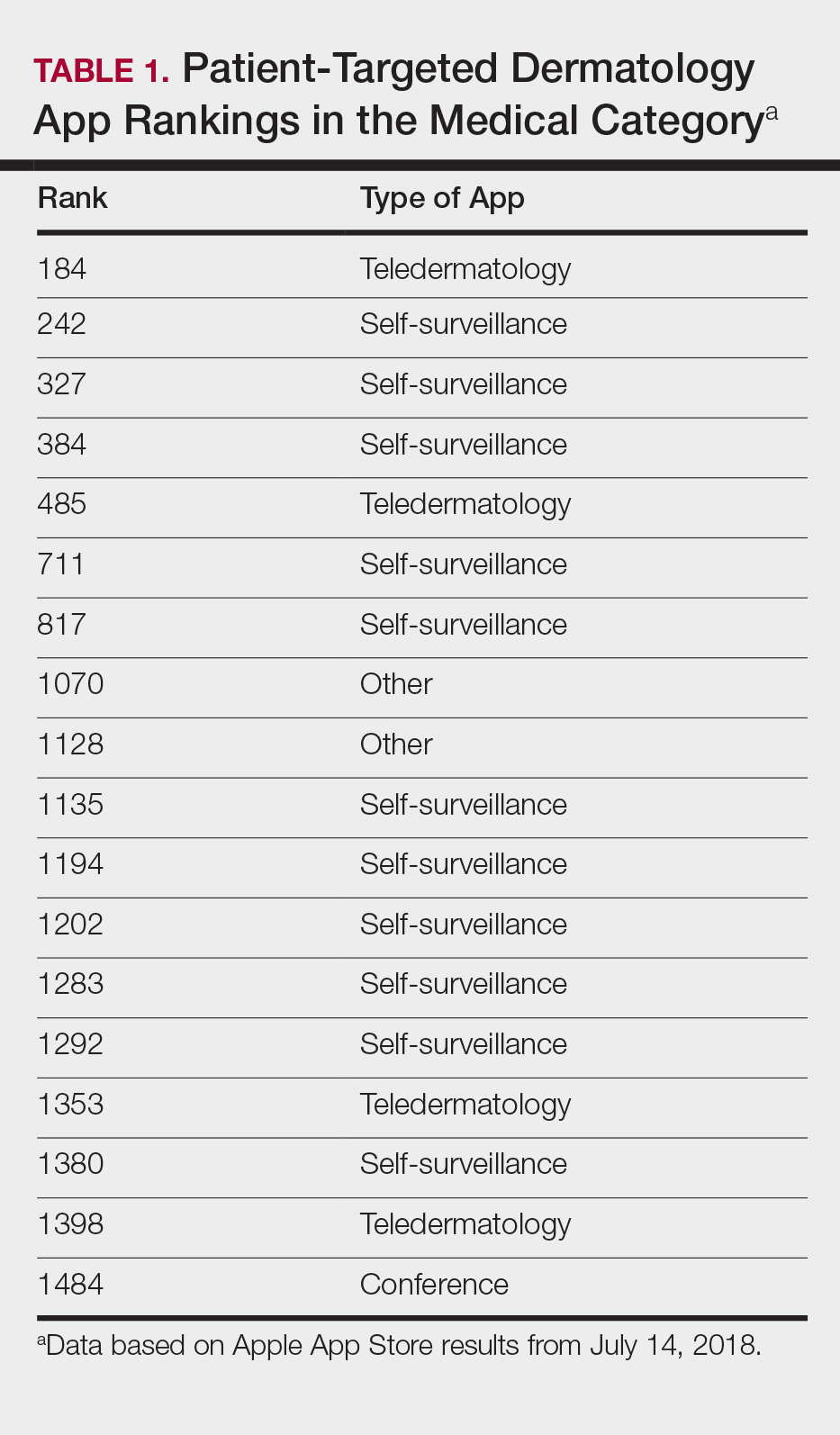

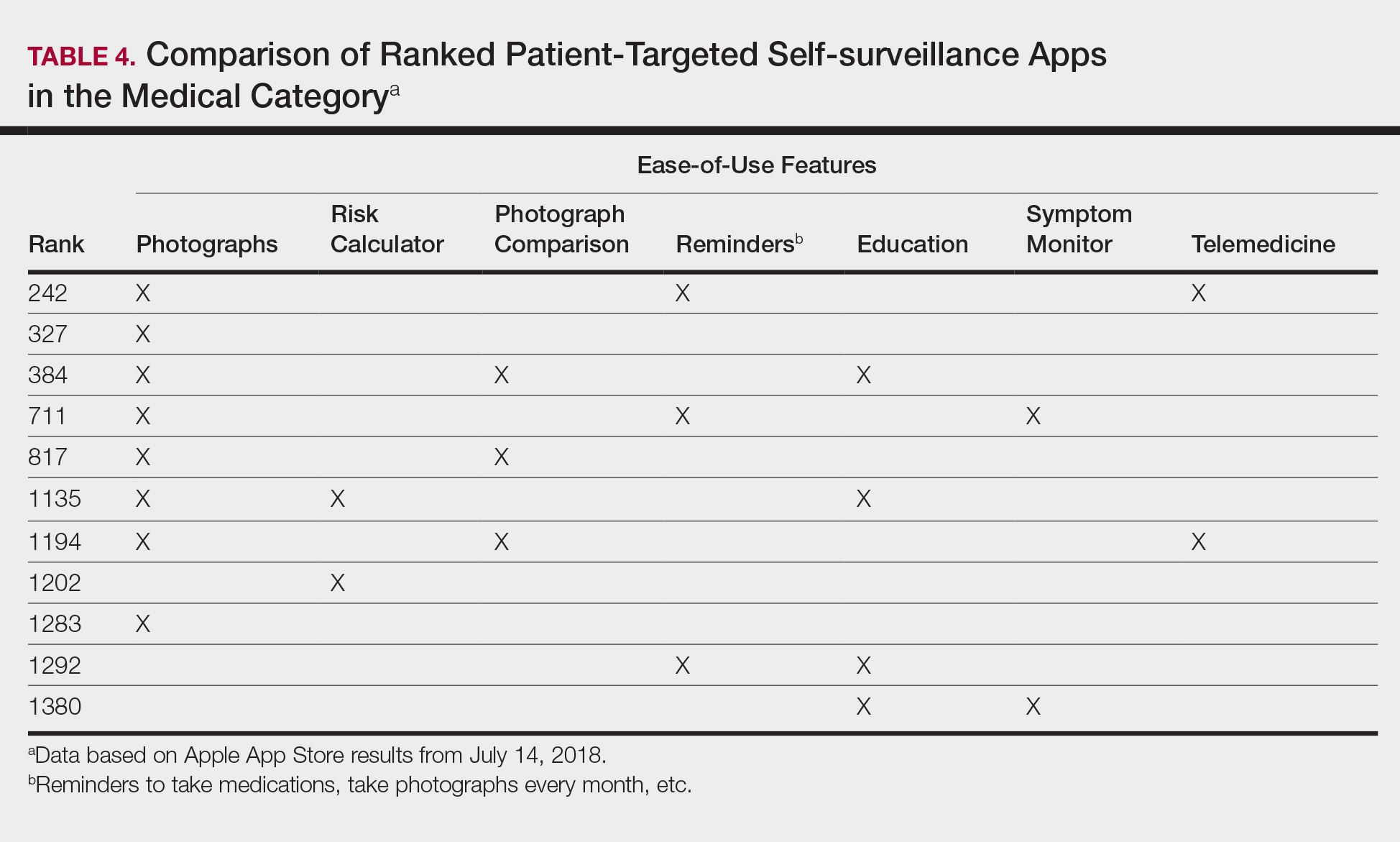

The initial search yielded 851 results, which was narrowed down to 29 apps after applying the exclusion criteria. Of note, prior to application of the exclusion criteria, one dermatology app that was considered to be a direct advertisement app claiming to cure acne was ranked fourth of 1500 apps in the Medical category. However, the majority of the search results were excluded because they were not popular enough to be ranked among the top 1500 apps. There were more ranked dermatology apps in the Medical category targeting patients than physicians; 18 of 29 (62%) qualifying apps targeted patients and 11 (38%) targeted physicians (Tables 1 and 2). No apps targeted both groups. The most common type of ranked app targeting patients was self-surveillance (11/18), and the most common type targeting physicians was reference (8/11). The highest ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app with a ranking of 184, and the highest ranked app targeting physicians was educational, ranked 353. The least common type of ranked apps targeting patients were “other” (2/18 [11%]; 1 prescription and 1 UV monitor app) and conference (1/18 [6%]). The least common type of ranked apps targeting physicians were education (2/11 [18%]) and dermoscopy (1/11 [9%]).

Our search of the Health and Fitness category yielded 6 apps, all targeting patients; 3 (50%) were self-surveillance apps, and 3 (50%) were classified as other (2 UV monitors and a conferencing app for cancer emotional support)(Table 3).

Our search of the Medical category for billing/coding and EMR apps yielded 232 and 164 apps, respectively; of them, 49 (21%) and 54 (33%) apps were ranked. These apps did not overlap with the dermatology-related search criteria; thus, we were not able to ascertain how many of these apps were used specifically by health care providers in dermatology.

COMMENT

Patient Apps

The most common apps used by patients are fitness and nutrition tracker apps categorized as Health and Fitness5,6; however, the majority of ranked dermatology apps are categorized as Medical per our findings. In a study of 557 dermatology patients, it was found that among the health-related apps they used, the most common apps after fitness/nutrition were references, followed by patient portals, self-surveillance, and emotional assistance apps.6 Our search was consistent with these findings, suggesting that the most desired dermatology apps by patients are those that allow them to be proactive with their health. It is no surprise that the top-ranked app targeting patients was a teledermatology app, followed by multiple self-surveillance apps. The highest ranked self-surveillance app in the Health and Fitness category focused on monitoring the effects of nutrition on symptoms of diseases including skin disorders, while the highest ranked (as well as the majority of) self-surveillance apps in the Medical category encompassed mole monitoring and cancer risk calculators.

Benefits of the ranked dermatology apps in the Medical and Health and Fitness categories targeting patients include more immediate access to health care and education. Despite this popularity among patients, Masud et al7 demonstrated that only 20.5% (9/44) of dermatology apps targeting patients may be reliable resources based on a rubric created by the investigators. Overall, there remains a research gap for a standardized scientific approach to evaluating app validity and reliability.

Teledermatology

Teledermatology apps are the most common dermatology apps,2 allowing for remote evaluation of patients through either live consultations or transmittance of medical information for later review by board-certified physicians.8 Features common to many teledermatology apps include accessibility on Android (Google Inc) and iOS as well as a web version. Security and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliance is especially important and is enforced through user authentications, data encryption, and automatic logout features. Data is not stored locally and is secured on a private server with backup. Referring providers and consultants often can communicate within the app. Insurance providers also may cover teledermatology services, and if not, the out-of-pocket costs often are affordable.

The highest-ranked patient app (ranked 184 in the Medical category) was a teledermatology app that did not meet the American Telemedicine Association standards for teledermatology apps.9 The popularity of this app among patients may have been attributable to multiple ease-of-use and turnaround time features. The user interface was simplistic, and the design was appealing to the eye. The entry field options were minimal to avoid confusion. The turnaround time to receive a diagnosis depended on 1 of 3 options, including a more rapid response for an increased cost. Ease of use was the highlight of this app at the cost of accuracy, as the limited amount of information that users were required to provide physicians compromised diagnostic accuracy in this app.

For comparison, we chose a nonranked (and thus less frequently used) teledermatology app that had previously undergone scientific evaluation using 13 evaluation criteria specific to teledermatology.10 The app also met the American Telemedicine Association standard for teledermatology apps.9 The app was originally a broader telemedicine app but featured a section specific to teledermatology. The user interface was simple but professional, almost resembling an EMR. The input fields included a comprehensive history that permitted a better evaluation of a lesion but might be tedious for users. This app boasted professionalism and accuracy, but from a user standpoint, it may have been too time-consuming.