User login

For weight-loss apps, the evidence base is still small

NASHVILLE –

Beginning with a pool of 1,380 publications, Christina Hopkins and her colleagues at Duke University, Durham, N.C., eventually identified just nine trials of all-digital interventions for weight loss that met their inclusion criteria.

Presenting their findings at a late-breaking poster session during Obesity Week, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Ms. Hopkins, a clinical psychology graduate student at Duke, and her colleagues found that three of the nine studies showed statistically significant weight loss, compared with a control state. Absolute weight loss in these three trials ranged from 3 kg to about 7 kg (between-group differences, P less than .001 for all).

Participants in another trial didn’t lose a statistically significant amount of weight, compared with the control arm of the study. However, the mean 5 kg lost by those in the intervention arm was enough to be clinically significant, so Ms. Hopkins and her colleagues included this study in a subanalysis that looked for effective modalities and interventions among the studies with significant results.

The duration of the studies ranged from 6 to 24 months, though five of the trials were less than 1 year long. Women made up the majority of participants in all but one trial.

“There is limited evidence that standalone digital weight-loss interventions produce clinically meaningful outcomes,” wrote Ms. Hopkins and her coauthors. “Absolute magnitude of weight loss was low, and the short intervention lengths call into question the sustainability of these weight losses.”

The systematic review cast a broad net to include digital modalities such as wireless scales, text messaging, email, and web-based interventions, as well as the use of smartphone apps and tracking devices. All interventions used multiple digital modalities.

The most frequently used technologies were the use of a website, used in six (67%) of the trials, followed by text messaging and smartphone apps, each used in five (56%) of the trials. Tracking devices, email, message boards, and gamification of some sort were all used in three (33%) of the trials.

In terms of the specific interventions used in the trials, weight, diet, and activity were all tracked in eight trials (89%). Similarly, all but one trial gave feedback and weight and health education to participants. Behavior change education, as well as calorie goals, were each used in six trials (67%).

Ms. Hopkins and her colleagues looked at which trials incorporated which modalities and interventions, finding that “trials that integrated components unique to digital interventions, such as gamification, podcasts, or interactive features, yielded significantly greater and more clinically meaningful weight losses.”

To be included in the systematic review, trials had to include adult participants with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2 and use a standalone digital intervention of at least 6 months’ duration. The primary outcome of interest in the review was the change in participant weight from baseline to the end of the minimum 6-month follow-up period. Randomized, controlled trials and feasibility trials were included, so long as participants were allocated randomly.

Of the 126 trials reviewed at the full text level, the most frequent reason for exclusion was the inclusion of human coaching. Also, 30 of the trials didn’t report weight change as an outcome, the investigators said.

Future directions should include comparing digital interventions that “utilize features unique to digital delivery” with those that more closely resemble in-person weight-loss management interventions, suggested Ms. Hopkins and her collaborators.

The authors reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hopkins C et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-P-LB-3640.

NASHVILLE –

Beginning with a pool of 1,380 publications, Christina Hopkins and her colleagues at Duke University, Durham, N.C., eventually identified just nine trials of all-digital interventions for weight loss that met their inclusion criteria.

Presenting their findings at a late-breaking poster session during Obesity Week, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Ms. Hopkins, a clinical psychology graduate student at Duke, and her colleagues found that three of the nine studies showed statistically significant weight loss, compared with a control state. Absolute weight loss in these three trials ranged from 3 kg to about 7 kg (between-group differences, P less than .001 for all).

Participants in another trial didn’t lose a statistically significant amount of weight, compared with the control arm of the study. However, the mean 5 kg lost by those in the intervention arm was enough to be clinically significant, so Ms. Hopkins and her colleagues included this study in a subanalysis that looked for effective modalities and interventions among the studies with significant results.

The duration of the studies ranged from 6 to 24 months, though five of the trials were less than 1 year long. Women made up the majority of participants in all but one trial.

“There is limited evidence that standalone digital weight-loss interventions produce clinically meaningful outcomes,” wrote Ms. Hopkins and her coauthors. “Absolute magnitude of weight loss was low, and the short intervention lengths call into question the sustainability of these weight losses.”

The systematic review cast a broad net to include digital modalities such as wireless scales, text messaging, email, and web-based interventions, as well as the use of smartphone apps and tracking devices. All interventions used multiple digital modalities.

The most frequently used technologies were the use of a website, used in six (67%) of the trials, followed by text messaging and smartphone apps, each used in five (56%) of the trials. Tracking devices, email, message boards, and gamification of some sort were all used in three (33%) of the trials.

In terms of the specific interventions used in the trials, weight, diet, and activity were all tracked in eight trials (89%). Similarly, all but one trial gave feedback and weight and health education to participants. Behavior change education, as well as calorie goals, were each used in six trials (67%).

Ms. Hopkins and her colleagues looked at which trials incorporated which modalities and interventions, finding that “trials that integrated components unique to digital interventions, such as gamification, podcasts, or interactive features, yielded significantly greater and more clinically meaningful weight losses.”

To be included in the systematic review, trials had to include adult participants with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2 and use a standalone digital intervention of at least 6 months’ duration. The primary outcome of interest in the review was the change in participant weight from baseline to the end of the minimum 6-month follow-up period. Randomized, controlled trials and feasibility trials were included, so long as participants were allocated randomly.

Of the 126 trials reviewed at the full text level, the most frequent reason for exclusion was the inclusion of human coaching. Also, 30 of the trials didn’t report weight change as an outcome, the investigators said.

Future directions should include comparing digital interventions that “utilize features unique to digital delivery” with those that more closely resemble in-person weight-loss management interventions, suggested Ms. Hopkins and her collaborators.

The authors reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hopkins C et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-P-LB-3640.

NASHVILLE –

Beginning with a pool of 1,380 publications, Christina Hopkins and her colleagues at Duke University, Durham, N.C., eventually identified just nine trials of all-digital interventions for weight loss that met their inclusion criteria.

Presenting their findings at a late-breaking poster session during Obesity Week, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Ms. Hopkins, a clinical psychology graduate student at Duke, and her colleagues found that three of the nine studies showed statistically significant weight loss, compared with a control state. Absolute weight loss in these three trials ranged from 3 kg to about 7 kg (between-group differences, P less than .001 for all).

Participants in another trial didn’t lose a statistically significant amount of weight, compared with the control arm of the study. However, the mean 5 kg lost by those in the intervention arm was enough to be clinically significant, so Ms. Hopkins and her colleagues included this study in a subanalysis that looked for effective modalities and interventions among the studies with significant results.

The duration of the studies ranged from 6 to 24 months, though five of the trials were less than 1 year long. Women made up the majority of participants in all but one trial.

“There is limited evidence that standalone digital weight-loss interventions produce clinically meaningful outcomes,” wrote Ms. Hopkins and her coauthors. “Absolute magnitude of weight loss was low, and the short intervention lengths call into question the sustainability of these weight losses.”

The systematic review cast a broad net to include digital modalities such as wireless scales, text messaging, email, and web-based interventions, as well as the use of smartphone apps and tracking devices. All interventions used multiple digital modalities.

The most frequently used technologies were the use of a website, used in six (67%) of the trials, followed by text messaging and smartphone apps, each used in five (56%) of the trials. Tracking devices, email, message boards, and gamification of some sort were all used in three (33%) of the trials.

In terms of the specific interventions used in the trials, weight, diet, and activity were all tracked in eight trials (89%). Similarly, all but one trial gave feedback and weight and health education to participants. Behavior change education, as well as calorie goals, were each used in six trials (67%).

Ms. Hopkins and her colleagues looked at which trials incorporated which modalities and interventions, finding that “trials that integrated components unique to digital interventions, such as gamification, podcasts, or interactive features, yielded significantly greater and more clinically meaningful weight losses.”

To be included in the systematic review, trials had to include adult participants with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2 and use a standalone digital intervention of at least 6 months’ duration. The primary outcome of interest in the review was the change in participant weight from baseline to the end of the minimum 6-month follow-up period. Randomized, controlled trials and feasibility trials were included, so long as participants were allocated randomly.

Of the 126 trials reviewed at the full text level, the most frequent reason for exclusion was the inclusion of human coaching. Also, 30 of the trials didn’t report weight change as an outcome, the investigators said.

Future directions should include comparing digital interventions that “utilize features unique to digital delivery” with those that more closely resemble in-person weight-loss management interventions, suggested Ms. Hopkins and her collaborators.

The authors reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hopkins C et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-P-LB-3640.

REPORTING FROM OBESITY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Three of nine studies found statistically significant weight loss with digital interventions.

Major finding: The largest effect was seen in one study showing 7 kg of long-term weight loss (P less than .001).

Study details: A systematic review of nine studies of digital-only interventions for weight loss.

Disclosures: The authors reported no outside sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hopkins C et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-P-PB-3640.

BMI compares favorably with body scanning for ID of cardiometabolic traits

Although body mass index is criticized for not distinguishing fat from lean mass, its ability to detect subclinical cardiometabolic abnormalities was on par with more sophisticated body scanning technology, according a recent analysis.

BMI and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) had similar associations with cardiometabolic traits associated with coronary heart disease in individuals evaluated at 10 and 18 years of age in a population-based birth cohort study, the study investigators said.

Changes over time in BMI and DXA also were strongly associated with changes in blood pressure, cholesterol, and other markers, according to Joshua A. Bell, PhD, of MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, University of Bristol, England, and his coinvestigators.

“Altogether, the results support abdominal fatness as a primary driver of cardiometabolic dysfunction and BMI as a useful tool for detecting its effects,” Dr. Bell and his colleagues said in a report on the study appearing in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In their analysis, Dr. Bell and coinvestigators used Pearson correlation coefficients to compare BMI and total and regional fat indexes from DXA in offspring participants from ALSPAC, (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children), in which BMI and DXA measurements were collected at 10 and 18 years of age.

Researchers identified a total of 2,840 participants with at least one measurement at each of those time points. The mean BMI was 17.5 kg/m2 at 10 years of age and 22.7 kg/m2 at 18 years of age, with greater than 10% of participants classified as obese at each of those time points.

High BMI and high total fat mass index were similarly associated with a variety of cardiometabolic traits, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, higher low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol levels and lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, and more inflammation, investigators found.

BMI was strongly correlated with DXA total and regional fat indexes at 10 years of age, and again at 18 years of age, they reported.

Moreover, gains in BMI from 10 to 18 years of age were strongly associated with higher blood pressure, higher LDL and VLDL cholesterol, lower HDL cholesterol, and other cardiometabolic traits, while associations between DXA measurements and those traits closely tracked those of BMI in pattern and magnitude, investigators added.

Fatness is most often measured in populations using BMI, and causal analyses suggest linkage between higher BMI and coronary heart disease and its intermediates, including blood pressure, LDL and remnant cholesterol, and glucose; despite that, BMI is often disparaged as a tool for assessing cardiometabolic abnormalities because it does not distinguish fat from lean mass and cannot quantify fat distribution, investigators said.

However, based on results of this analysis, it is reasonable to depend on BMI to indirectly measure body and abdominal fatness in future studies, they said in their report.

Dr. Bell and his colleagues reported that they had no relationships relevant to the study publication.

SOURCE: Bell JA et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;72(24):3142-54.

This study reinforces fatness, quantified by body mass index, as the key modifiable factor for maintaining healthy metabolism in young people, according to Ville-Petteri Mäkinen, ScD.

“The good news is that a single BMI measurement may be enough to capture the same essential information as a detailed body scan and serial measurements,” Dr. Mäkinen wrote in an accompanying editorial.

One other important take-home message of the study is that fat gain is not beneficial in any body region; that finding is important with respect to changes in BMI and fat mass index observed in the second decade of life that were associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in the late teens, he noted.

However, the broader take-home message for society is that children are being exposed to an “adverse metabolic milieu” that predicts cardiovascular disease in adulthood, according to Dr. Mäkinen.

“Childhood obesity must not be seen as a phase that passes but as a looming public health crisis that needs to be addressed by all of us,” he concluded.

Dr. Mäkinen is with the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide. He had no relationships relevant to the contents of his editorial (J Am College Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;74[24]3155-7).

This study reinforces fatness, quantified by body mass index, as the key modifiable factor for maintaining healthy metabolism in young people, according to Ville-Petteri Mäkinen, ScD.

“The good news is that a single BMI measurement may be enough to capture the same essential information as a detailed body scan and serial measurements,” Dr. Mäkinen wrote in an accompanying editorial.

One other important take-home message of the study is that fat gain is not beneficial in any body region; that finding is important with respect to changes in BMI and fat mass index observed in the second decade of life that were associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in the late teens, he noted.

However, the broader take-home message for society is that children are being exposed to an “adverse metabolic milieu” that predicts cardiovascular disease in adulthood, according to Dr. Mäkinen.

“Childhood obesity must not be seen as a phase that passes but as a looming public health crisis that needs to be addressed by all of us,” he concluded.

Dr. Mäkinen is with the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide. He had no relationships relevant to the contents of his editorial (J Am College Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;74[24]3155-7).

This study reinforces fatness, quantified by body mass index, as the key modifiable factor for maintaining healthy metabolism in young people, according to Ville-Petteri Mäkinen, ScD.

“The good news is that a single BMI measurement may be enough to capture the same essential information as a detailed body scan and serial measurements,” Dr. Mäkinen wrote in an accompanying editorial.

One other important take-home message of the study is that fat gain is not beneficial in any body region; that finding is important with respect to changes in BMI and fat mass index observed in the second decade of life that were associated with cardiometabolic risk factors in the late teens, he noted.

However, the broader take-home message for society is that children are being exposed to an “adverse metabolic milieu” that predicts cardiovascular disease in adulthood, according to Dr. Mäkinen.

“Childhood obesity must not be seen as a phase that passes but as a looming public health crisis that needs to be addressed by all of us,” he concluded.

Dr. Mäkinen is with the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide. He had no relationships relevant to the contents of his editorial (J Am College Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;74[24]3155-7).

Although body mass index is criticized for not distinguishing fat from lean mass, its ability to detect subclinical cardiometabolic abnormalities was on par with more sophisticated body scanning technology, according a recent analysis.

BMI and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) had similar associations with cardiometabolic traits associated with coronary heart disease in individuals evaluated at 10 and 18 years of age in a population-based birth cohort study, the study investigators said.

Changes over time in BMI and DXA also were strongly associated with changes in blood pressure, cholesterol, and other markers, according to Joshua A. Bell, PhD, of MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, University of Bristol, England, and his coinvestigators.

“Altogether, the results support abdominal fatness as a primary driver of cardiometabolic dysfunction and BMI as a useful tool for detecting its effects,” Dr. Bell and his colleagues said in a report on the study appearing in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In their analysis, Dr. Bell and coinvestigators used Pearson correlation coefficients to compare BMI and total and regional fat indexes from DXA in offspring participants from ALSPAC, (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children), in which BMI and DXA measurements were collected at 10 and 18 years of age.

Researchers identified a total of 2,840 participants with at least one measurement at each of those time points. The mean BMI was 17.5 kg/m2 at 10 years of age and 22.7 kg/m2 at 18 years of age, with greater than 10% of participants classified as obese at each of those time points.

High BMI and high total fat mass index were similarly associated with a variety of cardiometabolic traits, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, higher low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol levels and lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, and more inflammation, investigators found.

BMI was strongly correlated with DXA total and regional fat indexes at 10 years of age, and again at 18 years of age, they reported.

Moreover, gains in BMI from 10 to 18 years of age were strongly associated with higher blood pressure, higher LDL and VLDL cholesterol, lower HDL cholesterol, and other cardiometabolic traits, while associations between DXA measurements and those traits closely tracked those of BMI in pattern and magnitude, investigators added.

Fatness is most often measured in populations using BMI, and causal analyses suggest linkage between higher BMI and coronary heart disease and its intermediates, including blood pressure, LDL and remnant cholesterol, and glucose; despite that, BMI is often disparaged as a tool for assessing cardiometabolic abnormalities because it does not distinguish fat from lean mass and cannot quantify fat distribution, investigators said.

However, based on results of this analysis, it is reasonable to depend on BMI to indirectly measure body and abdominal fatness in future studies, they said in their report.

Dr. Bell and his colleagues reported that they had no relationships relevant to the study publication.

SOURCE: Bell JA et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;72(24):3142-54.

Although body mass index is criticized for not distinguishing fat from lean mass, its ability to detect subclinical cardiometabolic abnormalities was on par with more sophisticated body scanning technology, according a recent analysis.

BMI and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) had similar associations with cardiometabolic traits associated with coronary heart disease in individuals evaluated at 10 and 18 years of age in a population-based birth cohort study, the study investigators said.

Changes over time in BMI and DXA also were strongly associated with changes in blood pressure, cholesterol, and other markers, according to Joshua A. Bell, PhD, of MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, University of Bristol, England, and his coinvestigators.

“Altogether, the results support abdominal fatness as a primary driver of cardiometabolic dysfunction and BMI as a useful tool for detecting its effects,” Dr. Bell and his colleagues said in a report on the study appearing in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

In their analysis, Dr. Bell and coinvestigators used Pearson correlation coefficients to compare BMI and total and regional fat indexes from DXA in offspring participants from ALSPAC, (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children), in which BMI and DXA measurements were collected at 10 and 18 years of age.

Researchers identified a total of 2,840 participants with at least one measurement at each of those time points. The mean BMI was 17.5 kg/m2 at 10 years of age and 22.7 kg/m2 at 18 years of age, with greater than 10% of participants classified as obese at each of those time points.

High BMI and high total fat mass index were similarly associated with a variety of cardiometabolic traits, including systolic and diastolic blood pressure, higher low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol levels and lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, and more inflammation, investigators found.

BMI was strongly correlated with DXA total and regional fat indexes at 10 years of age, and again at 18 years of age, they reported.

Moreover, gains in BMI from 10 to 18 years of age were strongly associated with higher blood pressure, higher LDL and VLDL cholesterol, lower HDL cholesterol, and other cardiometabolic traits, while associations between DXA measurements and those traits closely tracked those of BMI in pattern and magnitude, investigators added.

Fatness is most often measured in populations using BMI, and causal analyses suggest linkage between higher BMI and coronary heart disease and its intermediates, including blood pressure, LDL and remnant cholesterol, and glucose; despite that, BMI is often disparaged as a tool for assessing cardiometabolic abnormalities because it does not distinguish fat from lean mass and cannot quantify fat distribution, investigators said.

However, based on results of this analysis, it is reasonable to depend on BMI to indirectly measure body and abdominal fatness in future studies, they said in their report.

Dr. Bell and his colleagues reported that they had no relationships relevant to the study publication.

SOURCE: Bell JA et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 18;72(24):3142-54.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point: Body mass index and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry had similar associations with cardiometabolic abnormalities in individuals evaluated at 10 and 18 years of age.

Major finding: BMI was strongly correlated with DXA total and regional fat indexes at age 10 years (0.9) and age 18 years.

Study details: Analysis of 2,840 offspring participants in ALSPAC (the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children).

Disclosures: Study authors reported that they had no relationships relevant to the study or its publication.

Source: Bell JA et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Dec 10;72(24):3142-54.

ABIM sued over maintenance of certification

Also today, drug test results should not dictate treatment, duodenoscopes contain more bacteria than expected, and weight-loss medications may have a role following bariatric surgery.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, drug test results should not dictate treatment, duodenoscopes contain more bacteria than expected, and weight-loss medications may have a role following bariatric surgery.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, drug test results should not dictate treatment, duodenoscopes contain more bacteria than expected, and weight-loss medications may have a role following bariatric surgery.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Heavy drinkers have a harder time keeping the weight off

NASHVILLE – Advising patients in a comprehensive weight loss intervention to moderate their alcohol consumption did not change how much they drank over the long term. At the same time, abstinent patients kept off more weight over time than those who were classified as heavy drinkers, in a new analysis of data from a multicenter trial.

Abstinent individuals lost just 1.6% more of their body weight after 4 years than those who drank (P = .003), a figure with “uncertain clinical significance,” Ariana Chao, PhD, said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “The results should be taken in the context of the potential – though controversial – benefits of light to moderate alcohol consumption,” she added.

Alcohol contains 7.1 kcal/g, and “calories from alcohol usually add, rather than substitute, for food intake,” said Dr. Chao. Alcohol’s disinhibiting effects are thought to contribute to increased food intake and the making of less healthy food choices. However, existing research has shown inconsistent findings about the relationship between alcohol consumption and body weight, she said.

Reducing or completely cutting out alcoholic beverage consumption is common advice for those trying to lose weight, but whether this advice is followed, and whether it makes a difference over the long term, has been an open question, said Dr. Chao.

She and her collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, used data from Look AHEAD, “a multicenter, randomized, clinical trial that compared an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) to a diabetes support and education (DSE) control group,” for 5,145 people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, explained Dr. Chao and her coinvestigators.

Dr. Chao and her colleagues looked at the effect that the lifestyle intervention had on alcohol consumption. Additionally, to see how drinkers and nondrinkers fared over the long term, they examined the interaction between alcohol consumption and weight loss at year 4, hypothesizing that individuals who received ILI would have a greater decrease in their alcohol consumption by year 4 than those who received DSE. The investigators had a second hypothesis that, among the ILI cohort, greater alcohol consumption would be associated with less weight loss over the 4 years studied.

To measure alcohol consumption, participants completed a questionnaire at baseline and annually thereafter. The questionnaire asked whether participants had consumed any alcoholic beverages in the past week, and how many drinks per week of wine, beer, or liquor per week were typical for those who did consume alcohol.

Respondents were grouped into four categories according to their baseline alcohol consumption: nondrinkers, light drinkers (fewer than 7 drinks weekly for men and 4 for women), moderate drinkers (7-14 drinks weekly for men and 4-7 for women), and heavy drinkers (more than 14 drinks weekly for men and 7 for women).

At baseline, 38% of participants reported being abstinent from alcohol, and about 54% reported being light drinkers. Moderate drinkers made up 6%, and 2% reported falling into the heavy drinking category. Females were more likely than males to be nondrinkers.

Heavy drinkers took in significantly more calories than nondrinkers at baseline (2,397 versus 1,907 kcal/day; P less than .001).

Individuals who had consistently been heavy drinkers throughout the study lost less weight than any other group, dropping just 2.4% of their body weight at year 4, compared with their baseline weight. Those who were abstinent from alcohol fared the best, losing 5.1% of their initial body weight (P = .04 for difference). “Heavy drinking is a risk factor for suboptimal long-term weight loss,” said Dr. Chao.

Even those who were consistent light drinkers lost a bit less than those who were abstinent, keeping off 4.2% of their baseline body weight at 4 years (P = .04).

Look AHEAD included individuals aged 45-76 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, or 27 kg/m2 for those on insulin. Excluded were those with hemoglobin A1c of at least 11%, blood pressure of at least 160/100 mm Hg, and triglycerides over 600 mg/dL. A total of 4,901 patients had complete data available in the public access data set and were included in the present analysis. Dr. Chao and her colleagues used statistical techniques to adjust for baseline differences among participants.

The three-part ILI in Look AHEAD began by encouraging a low-calorie diet of 1,200-1,500 kcal/day for those weighing under 250 pounds, and 1,500-1,800 kcal/day for those who were heavier at baseline. Advice was to consume a balanced diet with less than 30% fat, less than 10% saturated fat, and at least 15% protein.

Patients were advised to strive for 10,000 steps per day, with 175 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise each week. Exercise was unsupervised.

Behavioral modification techniques included goal-setting, stimulus control, self-monitoring, and ideas for problem solving and relapse prevention. The intervention used motivational interviewing techniques.

With regard to alcohol, the ILI group was given information about the number of calories in various alcoholic beverages and advised to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed, in order to reduce calories.

The DSE group participated in three group sessions annually, and received general information about nutrition, exercise, and general support.

A potentially important limitation of the study was that alcohol consumption was assessed by self-report and a request for annual recall of typical drinking habits. An audience member from the United Kingdom commented that she found the overall rate of reported alcohol consumption to be “shockingly low,” compared with what her patients report drinking in England. The average United States resident drinks 2.3 gallons of alcohol, or 494 standard drinks, annually, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, said Dr. Chao.

The midlife age range of participants, their diabetes diagnosis, and the fact that depressive symptoms were overall low limits generalizability of the findings, said Dr. Chao, adding that psychosocial factors, other health conditions, and current or past alcohol use disorder could also cause some residual confounding of the data.

Dr. Chao has received research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Chao A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2017.

NASHVILLE – Advising patients in a comprehensive weight loss intervention to moderate their alcohol consumption did not change how much they drank over the long term. At the same time, abstinent patients kept off more weight over time than those who were classified as heavy drinkers, in a new analysis of data from a multicenter trial.

Abstinent individuals lost just 1.6% more of their body weight after 4 years than those who drank (P = .003), a figure with “uncertain clinical significance,” Ariana Chao, PhD, said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “The results should be taken in the context of the potential – though controversial – benefits of light to moderate alcohol consumption,” she added.

Alcohol contains 7.1 kcal/g, and “calories from alcohol usually add, rather than substitute, for food intake,” said Dr. Chao. Alcohol’s disinhibiting effects are thought to contribute to increased food intake and the making of less healthy food choices. However, existing research has shown inconsistent findings about the relationship between alcohol consumption and body weight, she said.

Reducing or completely cutting out alcoholic beverage consumption is common advice for those trying to lose weight, but whether this advice is followed, and whether it makes a difference over the long term, has been an open question, said Dr. Chao.

She and her collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, used data from Look AHEAD, “a multicenter, randomized, clinical trial that compared an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) to a diabetes support and education (DSE) control group,” for 5,145 people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, explained Dr. Chao and her coinvestigators.

Dr. Chao and her colleagues looked at the effect that the lifestyle intervention had on alcohol consumption. Additionally, to see how drinkers and nondrinkers fared over the long term, they examined the interaction between alcohol consumption and weight loss at year 4, hypothesizing that individuals who received ILI would have a greater decrease in their alcohol consumption by year 4 than those who received DSE. The investigators had a second hypothesis that, among the ILI cohort, greater alcohol consumption would be associated with less weight loss over the 4 years studied.

To measure alcohol consumption, participants completed a questionnaire at baseline and annually thereafter. The questionnaire asked whether participants had consumed any alcoholic beverages in the past week, and how many drinks per week of wine, beer, or liquor per week were typical for those who did consume alcohol.

Respondents were grouped into four categories according to their baseline alcohol consumption: nondrinkers, light drinkers (fewer than 7 drinks weekly for men and 4 for women), moderate drinkers (7-14 drinks weekly for men and 4-7 for women), and heavy drinkers (more than 14 drinks weekly for men and 7 for women).

At baseline, 38% of participants reported being abstinent from alcohol, and about 54% reported being light drinkers. Moderate drinkers made up 6%, and 2% reported falling into the heavy drinking category. Females were more likely than males to be nondrinkers.

Heavy drinkers took in significantly more calories than nondrinkers at baseline (2,397 versus 1,907 kcal/day; P less than .001).

Individuals who had consistently been heavy drinkers throughout the study lost less weight than any other group, dropping just 2.4% of their body weight at year 4, compared with their baseline weight. Those who were abstinent from alcohol fared the best, losing 5.1% of their initial body weight (P = .04 for difference). “Heavy drinking is a risk factor for suboptimal long-term weight loss,” said Dr. Chao.

Even those who were consistent light drinkers lost a bit less than those who were abstinent, keeping off 4.2% of their baseline body weight at 4 years (P = .04).

Look AHEAD included individuals aged 45-76 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, or 27 kg/m2 for those on insulin. Excluded were those with hemoglobin A1c of at least 11%, blood pressure of at least 160/100 mm Hg, and triglycerides over 600 mg/dL. A total of 4,901 patients had complete data available in the public access data set and were included in the present analysis. Dr. Chao and her colleagues used statistical techniques to adjust for baseline differences among participants.

The three-part ILI in Look AHEAD began by encouraging a low-calorie diet of 1,200-1,500 kcal/day for those weighing under 250 pounds, and 1,500-1,800 kcal/day for those who were heavier at baseline. Advice was to consume a balanced diet with less than 30% fat, less than 10% saturated fat, and at least 15% protein.

Patients were advised to strive for 10,000 steps per day, with 175 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise each week. Exercise was unsupervised.

Behavioral modification techniques included goal-setting, stimulus control, self-monitoring, and ideas for problem solving and relapse prevention. The intervention used motivational interviewing techniques.

With regard to alcohol, the ILI group was given information about the number of calories in various alcoholic beverages and advised to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed, in order to reduce calories.

The DSE group participated in three group sessions annually, and received general information about nutrition, exercise, and general support.

A potentially important limitation of the study was that alcohol consumption was assessed by self-report and a request for annual recall of typical drinking habits. An audience member from the United Kingdom commented that she found the overall rate of reported alcohol consumption to be “shockingly low,” compared with what her patients report drinking in England. The average United States resident drinks 2.3 gallons of alcohol, or 494 standard drinks, annually, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, said Dr. Chao.

The midlife age range of participants, their diabetes diagnosis, and the fact that depressive symptoms were overall low limits generalizability of the findings, said Dr. Chao, adding that psychosocial factors, other health conditions, and current or past alcohol use disorder could also cause some residual confounding of the data.

Dr. Chao has received research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Chao A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2017.

NASHVILLE – Advising patients in a comprehensive weight loss intervention to moderate their alcohol consumption did not change how much they drank over the long term. At the same time, abstinent patients kept off more weight over time than those who were classified as heavy drinkers, in a new analysis of data from a multicenter trial.

Abstinent individuals lost just 1.6% more of their body weight after 4 years than those who drank (P = .003), a figure with “uncertain clinical significance,” Ariana Chao, PhD, said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. “The results should be taken in the context of the potential – though controversial – benefits of light to moderate alcohol consumption,” she added.

Alcohol contains 7.1 kcal/g, and “calories from alcohol usually add, rather than substitute, for food intake,” said Dr. Chao. Alcohol’s disinhibiting effects are thought to contribute to increased food intake and the making of less healthy food choices. However, existing research has shown inconsistent findings about the relationship between alcohol consumption and body weight, she said.

Reducing or completely cutting out alcoholic beverage consumption is common advice for those trying to lose weight, but whether this advice is followed, and whether it makes a difference over the long term, has been an open question, said Dr. Chao.

She and her collaborators at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, used data from Look AHEAD, “a multicenter, randomized, clinical trial that compared an intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) to a diabetes support and education (DSE) control group,” for 5,145 people with overweight or obesity and type 2 diabetes, explained Dr. Chao and her coinvestigators.

Dr. Chao and her colleagues looked at the effect that the lifestyle intervention had on alcohol consumption. Additionally, to see how drinkers and nondrinkers fared over the long term, they examined the interaction between alcohol consumption and weight loss at year 4, hypothesizing that individuals who received ILI would have a greater decrease in their alcohol consumption by year 4 than those who received DSE. The investigators had a second hypothesis that, among the ILI cohort, greater alcohol consumption would be associated with less weight loss over the 4 years studied.

To measure alcohol consumption, participants completed a questionnaire at baseline and annually thereafter. The questionnaire asked whether participants had consumed any alcoholic beverages in the past week, and how many drinks per week of wine, beer, or liquor per week were typical for those who did consume alcohol.

Respondents were grouped into four categories according to their baseline alcohol consumption: nondrinkers, light drinkers (fewer than 7 drinks weekly for men and 4 for women), moderate drinkers (7-14 drinks weekly for men and 4-7 for women), and heavy drinkers (more than 14 drinks weekly for men and 7 for women).

At baseline, 38% of participants reported being abstinent from alcohol, and about 54% reported being light drinkers. Moderate drinkers made up 6%, and 2% reported falling into the heavy drinking category. Females were more likely than males to be nondrinkers.

Heavy drinkers took in significantly more calories than nondrinkers at baseline (2,397 versus 1,907 kcal/day; P less than .001).

Individuals who had consistently been heavy drinkers throughout the study lost less weight than any other group, dropping just 2.4% of their body weight at year 4, compared with their baseline weight. Those who were abstinent from alcohol fared the best, losing 5.1% of their initial body weight (P = .04 for difference). “Heavy drinking is a risk factor for suboptimal long-term weight loss,” said Dr. Chao.

Even those who were consistent light drinkers lost a bit less than those who were abstinent, keeping off 4.2% of their baseline body weight at 4 years (P = .04).

Look AHEAD included individuals aged 45-76 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus and a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, or 27 kg/m2 for those on insulin. Excluded were those with hemoglobin A1c of at least 11%, blood pressure of at least 160/100 mm Hg, and triglycerides over 600 mg/dL. A total of 4,901 patients had complete data available in the public access data set and were included in the present analysis. Dr. Chao and her colleagues used statistical techniques to adjust for baseline differences among participants.

The three-part ILI in Look AHEAD began by encouraging a low-calorie diet of 1,200-1,500 kcal/day for those weighing under 250 pounds, and 1,500-1,800 kcal/day for those who were heavier at baseline. Advice was to consume a balanced diet with less than 30% fat, less than 10% saturated fat, and at least 15% protein.

Patients were advised to strive for 10,000 steps per day, with 175 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise each week. Exercise was unsupervised.

Behavioral modification techniques included goal-setting, stimulus control, self-monitoring, and ideas for problem solving and relapse prevention. The intervention used motivational interviewing techniques.

With regard to alcohol, the ILI group was given information about the number of calories in various alcoholic beverages and advised to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed, in order to reduce calories.

The DSE group participated in three group sessions annually, and received general information about nutrition, exercise, and general support.

A potentially important limitation of the study was that alcohol consumption was assessed by self-report and a request for annual recall of typical drinking habits. An audience member from the United Kingdom commented that she found the overall rate of reported alcohol consumption to be “shockingly low,” compared with what her patients report drinking in England. The average United States resident drinks 2.3 gallons of alcohol, or 494 standard drinks, annually, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, said Dr. Chao.

The midlife age range of participants, their diabetes diagnosis, and the fact that depressive symptoms were overall low limits generalizability of the findings, said Dr. Chao, adding that psychosocial factors, other health conditions, and current or past alcohol use disorder could also cause some residual confounding of the data.

Dr. Chao has received research support from Shire Pharmaceuticals.

SOURCE: Chao A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2017.

REPORTING FROM OBESITY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: After 4 years of an intervention program, heavy drinkers had the smallest net loss in body weight.

Major finding: Heavy drinkers kept off less than half as much weight as teetotalers (2.4% versus 5.1% of baseline weight, P = .04).

Study details: Analysis of public data from Look AHEAD, a multicenter randomized trial of intensive lifestyle intervention for weight loss that enrolled 5,145 people.

Disclosures: Dr. Chao reported receiving research funding from Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Chao A et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2017.

Weight loss medications may have a role after bariatric surgery

NASHVILLE – .

Phentermine and topiramate were each prescribed to between 10% and 12.5% of bariatric surgery patients at Boston Medical Center in recent years. That figure had been steadily increasing since 2004, when data collection began, Nawfal W. Istfan, MD, PhD, said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

However, the center didn’t know how patients who had received medication fared for long-term maintenance of weight loss, compared with those who had surgery alone; also, there were no clinical guidelines for prescribing weight loss medications (WLMs). “Have we done those patients any benefit by prescribing weight loss medications after gastric bypass surgery?” asked Dr. Istfan. The answer from the Boston Medical Center data is a qualified “yes;” patients with the highest rates of weight regain who were adherent to their medication did see lower rates of regain, and fewer rapid weight regain events.

Comparing patients who received prescriptions with those who did not, patients with less weight loss at nadir were more likely to receive a prescription. “This could very well be the reason they were prescribed a medication: They did not lose as much weight, and they are more likely to ask us” for WLMs, said Dr. Istfan, an endocrinologist at Boston University. However, for those who were prescribed WLMs, the slope of regain was flatter than for those who didn’t receive medication. Of the 626 patients included in the study, 91 received phentermine alone, 54 topiramate alone, and 113 were prescribed both phentermine and topiramate. Three received lorcaserin.

Those receiving medication were similar to the total bariatric surgery population in terms of age, sex, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and preoperative body mass index, said Dr. Istfan, the senior author in the study. However, Hispanic individuals were more likely to receive WLMs, he said.

Recognizing that “the ratio of weight regain to nadir weight is more indicative of overfeeding than other parameters,” Dr. Istfan said that he and his colleagues divided patients into quartiles of regain, based on this ratio. The quartiles fell out so that those who had the least regain either lost weight or regained less than 1.4%, to make up the first quartile. The second quartile included those who regained from 1.5% to 6.26%, while the third quartile ranged up to 14.29% regain. Those who regained 14.3% or more were in the highest quartile of weight regain.

In comparing characteristics of the quartiles, there were more African Americans in the two higher quartiles (P = .017). More patients had achieved maximal weight loss in the highest quartile of regain (P less than .0001), though preoperative BMI had also been higher in this group (P = .0008).

After statistical adjustment, the investigators found that for individuals who had the highest quartile of regain, patients who were adherent to their WLMs had significantly less weight regain than those who took no medication (P = .014). However, patients considered nonadherent saw no medication effect on weight regain. The differences were small overall, with adherent patients regaining about 27% of weight relative to their nadir and those who didn’t take WLMs regaining about 30%. These significant results were seen long after bariatric surgery, at about 7 years post surgery.

In another analysis that looked just at the quartile of patients with the highest regain rate, weight regain was significantly delayed among those who were prescribed – and were adherent to – WLMs (P = .023). The analysis used a threshold weight regain rate of 1.22% per month; levels lower than that did not see a significant drug effect, and the effect was not seen for those not adherent to their WLMs.

Finally, an adjusted statistical analysis compared those taking and not taking WLMs to see whether WLMs were effective at preventing weight regain in rolling 90-day intervals throughout the study period. Again, in the highest quartile, those who were adherent to WLMs had a lower odds ratio of hitting the 1.22%/month regain rate, compared with those not taking medication (OR, 0.570; 95% confidence interval, 0.371-0.877; P = .01). The effect was not significant for the nonadherent group (OR, 0.872; 95% CI, 0.593-1.284; P = .489).

As more bariatric procedures are being done, and as more patients are living with their surgeries, physicians are seeing more weight regain, said Dr. Istfan, noting that it’s important to assess efficacy of WLMs in the postsurgical population. “Recent work showed that by 5 years after gastric bypass, half of patients had regained more than 15% of their nadir weight, and two-thirds of patients had regained more than 20% of their total maximum weight loss, said Dr. Istfan (King WC et al. JAMA.2018;320:1560).

Typically, patients will see about a 35% weight loss at their nadir, with a gradual increase in weight gain beginning about 2 years after surgery. Though it’s true that a net weight loss of 25% is still good, it can be a misleading way to look at the data, “because it does not focus on the process of weight regain itself,” said Dr. Istfan.

“Despite the maintenance of substantial weight loss, weight regain is concerning: It’s the present and future, not the past,” he said.

Regaining weight necessarily means that patients are having excess nutrient intake and a net-positive energy balance; this state can be associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and insulin resistance – all potential contributors to the recurrence of comorbidities.

What’s to be done about weight regain, if it’s a point of concern? One option, said Dr. Istfan, is to consider more surgery. Patients might want a “re-do;” techniques that have been tried include reshaping the pouch and doing an anastomosis plication. If a gastro-gastric fistula’s developed, that can be corrected, he said.

Some factors influencing regain can be targeted by behavioral therapy. These include addressing alcohol consumption, discouraging grazing, encouraging exercise, and assessing and modifying diet quality in general.

“There is a general reluctance on the part of physicians to use weight loss medications after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Istfan. Reasons can include concern about further nutritional compromise, especially when thinking about long-term use of appetite-suppressing medications. Importantly, there aren’t clinical guidelines for prescribing WLMs after bariatric surgery, nor is there a strong body of prospective studies in this area.

Dr. Istfan noted that the medical and surgical bariatric teams collaborate closely at Boston Medical Center to provide pre- and postoperative assessment and management.

The long observational interval and ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of the study population are strengths, said Dr. Istfan. Also, the three different multivariable models converged to similar findings.

However, the study was retrospective, with some confounding likely, and each prescriber involved in the study may have varying prescribing practices. Also, adherence was assessed by follow-up medication appointments, a measure that likely introduced some inaccuracy.

“Weight loss medications are potentially effective tools to counter weight regain after bariatric surgery; prospective studies are needed to optimize the use of weight loss medications after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Istfan.

Dr. Istfan reported no outside sources of funding, and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Anderson W et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2016.

NASHVILLE – .

Phentermine and topiramate were each prescribed to between 10% and 12.5% of bariatric surgery patients at Boston Medical Center in recent years. That figure had been steadily increasing since 2004, when data collection began, Nawfal W. Istfan, MD, PhD, said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

However, the center didn’t know how patients who had received medication fared for long-term maintenance of weight loss, compared with those who had surgery alone; also, there were no clinical guidelines for prescribing weight loss medications (WLMs). “Have we done those patients any benefit by prescribing weight loss medications after gastric bypass surgery?” asked Dr. Istfan. The answer from the Boston Medical Center data is a qualified “yes;” patients with the highest rates of weight regain who were adherent to their medication did see lower rates of regain, and fewer rapid weight regain events.

Comparing patients who received prescriptions with those who did not, patients with less weight loss at nadir were more likely to receive a prescription. “This could very well be the reason they were prescribed a medication: They did not lose as much weight, and they are more likely to ask us” for WLMs, said Dr. Istfan, an endocrinologist at Boston University. However, for those who were prescribed WLMs, the slope of regain was flatter than for those who didn’t receive medication. Of the 626 patients included in the study, 91 received phentermine alone, 54 topiramate alone, and 113 were prescribed both phentermine and topiramate. Three received lorcaserin.

Those receiving medication were similar to the total bariatric surgery population in terms of age, sex, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and preoperative body mass index, said Dr. Istfan, the senior author in the study. However, Hispanic individuals were more likely to receive WLMs, he said.

Recognizing that “the ratio of weight regain to nadir weight is more indicative of overfeeding than other parameters,” Dr. Istfan said that he and his colleagues divided patients into quartiles of regain, based on this ratio. The quartiles fell out so that those who had the least regain either lost weight or regained less than 1.4%, to make up the first quartile. The second quartile included those who regained from 1.5% to 6.26%, while the third quartile ranged up to 14.29% regain. Those who regained 14.3% or more were in the highest quartile of weight regain.

In comparing characteristics of the quartiles, there were more African Americans in the two higher quartiles (P = .017). More patients had achieved maximal weight loss in the highest quartile of regain (P less than .0001), though preoperative BMI had also been higher in this group (P = .0008).

After statistical adjustment, the investigators found that for individuals who had the highest quartile of regain, patients who were adherent to their WLMs had significantly less weight regain than those who took no medication (P = .014). However, patients considered nonadherent saw no medication effect on weight regain. The differences were small overall, with adherent patients regaining about 27% of weight relative to their nadir and those who didn’t take WLMs regaining about 30%. These significant results were seen long after bariatric surgery, at about 7 years post surgery.

In another analysis that looked just at the quartile of patients with the highest regain rate, weight regain was significantly delayed among those who were prescribed – and were adherent to – WLMs (P = .023). The analysis used a threshold weight regain rate of 1.22% per month; levels lower than that did not see a significant drug effect, and the effect was not seen for those not adherent to their WLMs.

Finally, an adjusted statistical analysis compared those taking and not taking WLMs to see whether WLMs were effective at preventing weight regain in rolling 90-day intervals throughout the study period. Again, in the highest quartile, those who were adherent to WLMs had a lower odds ratio of hitting the 1.22%/month regain rate, compared with those not taking medication (OR, 0.570; 95% confidence interval, 0.371-0.877; P = .01). The effect was not significant for the nonadherent group (OR, 0.872; 95% CI, 0.593-1.284; P = .489).

As more bariatric procedures are being done, and as more patients are living with their surgeries, physicians are seeing more weight regain, said Dr. Istfan, noting that it’s important to assess efficacy of WLMs in the postsurgical population. “Recent work showed that by 5 years after gastric bypass, half of patients had regained more than 15% of their nadir weight, and two-thirds of patients had regained more than 20% of their total maximum weight loss, said Dr. Istfan (King WC et al. JAMA.2018;320:1560).

Typically, patients will see about a 35% weight loss at their nadir, with a gradual increase in weight gain beginning about 2 years after surgery. Though it’s true that a net weight loss of 25% is still good, it can be a misleading way to look at the data, “because it does not focus on the process of weight regain itself,” said Dr. Istfan.

“Despite the maintenance of substantial weight loss, weight regain is concerning: It’s the present and future, not the past,” he said.

Regaining weight necessarily means that patients are having excess nutrient intake and a net-positive energy balance; this state can be associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and insulin resistance – all potential contributors to the recurrence of comorbidities.

What’s to be done about weight regain, if it’s a point of concern? One option, said Dr. Istfan, is to consider more surgery. Patients might want a “re-do;” techniques that have been tried include reshaping the pouch and doing an anastomosis plication. If a gastro-gastric fistula’s developed, that can be corrected, he said.

Some factors influencing regain can be targeted by behavioral therapy. These include addressing alcohol consumption, discouraging grazing, encouraging exercise, and assessing and modifying diet quality in general.

“There is a general reluctance on the part of physicians to use weight loss medications after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Istfan. Reasons can include concern about further nutritional compromise, especially when thinking about long-term use of appetite-suppressing medications. Importantly, there aren’t clinical guidelines for prescribing WLMs after bariatric surgery, nor is there a strong body of prospective studies in this area.

Dr. Istfan noted that the medical and surgical bariatric teams collaborate closely at Boston Medical Center to provide pre- and postoperative assessment and management.

The long observational interval and ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of the study population are strengths, said Dr. Istfan. Also, the three different multivariable models converged to similar findings.

However, the study was retrospective, with some confounding likely, and each prescriber involved in the study may have varying prescribing practices. Also, adherence was assessed by follow-up medication appointments, a measure that likely introduced some inaccuracy.

“Weight loss medications are potentially effective tools to counter weight regain after bariatric surgery; prospective studies are needed to optimize the use of weight loss medications after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Istfan.

Dr. Istfan reported no outside sources of funding, and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Anderson W et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2016.

NASHVILLE – .

Phentermine and topiramate were each prescribed to between 10% and 12.5% of bariatric surgery patients at Boston Medical Center in recent years. That figure had been steadily increasing since 2004, when data collection began, Nawfal W. Istfan, MD, PhD, said at the meeting presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

However, the center didn’t know how patients who had received medication fared for long-term maintenance of weight loss, compared with those who had surgery alone; also, there were no clinical guidelines for prescribing weight loss medications (WLMs). “Have we done those patients any benefit by prescribing weight loss medications after gastric bypass surgery?” asked Dr. Istfan. The answer from the Boston Medical Center data is a qualified “yes;” patients with the highest rates of weight regain who were adherent to their medication did see lower rates of regain, and fewer rapid weight regain events.

Comparing patients who received prescriptions with those who did not, patients with less weight loss at nadir were more likely to receive a prescription. “This could very well be the reason they were prescribed a medication: They did not lose as much weight, and they are more likely to ask us” for WLMs, said Dr. Istfan, an endocrinologist at Boston University. However, for those who were prescribed WLMs, the slope of regain was flatter than for those who didn’t receive medication. Of the 626 patients included in the study, 91 received phentermine alone, 54 topiramate alone, and 113 were prescribed both phentermine and topiramate. Three received lorcaserin.

Those receiving medication were similar to the total bariatric surgery population in terms of age, sex, comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and preoperative body mass index, said Dr. Istfan, the senior author in the study. However, Hispanic individuals were more likely to receive WLMs, he said.

Recognizing that “the ratio of weight regain to nadir weight is more indicative of overfeeding than other parameters,” Dr. Istfan said that he and his colleagues divided patients into quartiles of regain, based on this ratio. The quartiles fell out so that those who had the least regain either lost weight or regained less than 1.4%, to make up the first quartile. The second quartile included those who regained from 1.5% to 6.26%, while the third quartile ranged up to 14.29% regain. Those who regained 14.3% or more were in the highest quartile of weight regain.

In comparing characteristics of the quartiles, there were more African Americans in the two higher quartiles (P = .017). More patients had achieved maximal weight loss in the highest quartile of regain (P less than .0001), though preoperative BMI had also been higher in this group (P = .0008).

After statistical adjustment, the investigators found that for individuals who had the highest quartile of regain, patients who were adherent to their WLMs had significantly less weight regain than those who took no medication (P = .014). However, patients considered nonadherent saw no medication effect on weight regain. The differences were small overall, with adherent patients regaining about 27% of weight relative to their nadir and those who didn’t take WLMs regaining about 30%. These significant results were seen long after bariatric surgery, at about 7 years post surgery.

In another analysis that looked just at the quartile of patients with the highest regain rate, weight regain was significantly delayed among those who were prescribed – and were adherent to – WLMs (P = .023). The analysis used a threshold weight regain rate of 1.22% per month; levels lower than that did not see a significant drug effect, and the effect was not seen for those not adherent to their WLMs.

Finally, an adjusted statistical analysis compared those taking and not taking WLMs to see whether WLMs were effective at preventing weight regain in rolling 90-day intervals throughout the study period. Again, in the highest quartile, those who were adherent to WLMs had a lower odds ratio of hitting the 1.22%/month regain rate, compared with those not taking medication (OR, 0.570; 95% confidence interval, 0.371-0.877; P = .01). The effect was not significant for the nonadherent group (OR, 0.872; 95% CI, 0.593-1.284; P = .489).

As more bariatric procedures are being done, and as more patients are living with their surgeries, physicians are seeing more weight regain, said Dr. Istfan, noting that it’s important to assess efficacy of WLMs in the postsurgical population. “Recent work showed that by 5 years after gastric bypass, half of patients had regained more than 15% of their nadir weight, and two-thirds of patients had regained more than 20% of their total maximum weight loss, said Dr. Istfan (King WC et al. JAMA.2018;320:1560).

Typically, patients will see about a 35% weight loss at their nadir, with a gradual increase in weight gain beginning about 2 years after surgery. Though it’s true that a net weight loss of 25% is still good, it can be a misleading way to look at the data, “because it does not focus on the process of weight regain itself,” said Dr. Istfan.

“Despite the maintenance of substantial weight loss, weight regain is concerning: It’s the present and future, not the past,” he said.

Regaining weight necessarily means that patients are having excess nutrient intake and a net-positive energy balance; this state can be associated with oxidative stress, inflammation, and insulin resistance – all potential contributors to the recurrence of comorbidities.

What’s to be done about weight regain, if it’s a point of concern? One option, said Dr. Istfan, is to consider more surgery. Patients might want a “re-do;” techniques that have been tried include reshaping the pouch and doing an anastomosis plication. If a gastro-gastric fistula’s developed, that can be corrected, he said.

Some factors influencing regain can be targeted by behavioral therapy. These include addressing alcohol consumption, discouraging grazing, encouraging exercise, and assessing and modifying diet quality in general.

“There is a general reluctance on the part of physicians to use weight loss medications after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Istfan. Reasons can include concern about further nutritional compromise, especially when thinking about long-term use of appetite-suppressing medications. Importantly, there aren’t clinical guidelines for prescribing WLMs after bariatric surgery, nor is there a strong body of prospective studies in this area.

Dr. Istfan noted that the medical and surgical bariatric teams collaborate closely at Boston Medical Center to provide pre- and postoperative assessment and management.

The long observational interval and ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of the study population are strengths, said Dr. Istfan. Also, the three different multivariable models converged to similar findings.

However, the study was retrospective, with some confounding likely, and each prescriber involved in the study may have varying prescribing practices. Also, adherence was assessed by follow-up medication appointments, a measure that likely introduced some inaccuracy.

“Weight loss medications are potentially effective tools to counter weight regain after bariatric surgery; prospective studies are needed to optimize the use of weight loss medications after bariatric surgery,” said Dr. Istfan.

Dr. Istfan reported no outside sources of funding, and no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Anderson W et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2016.

REPORTING FROM OBESITY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Weight loss medication flattened the curve of weight regain after bariatric surgery – for some patients.

Major finding: Weight loss medicine reduced regain among those who had the most weight regain (P =.014).

Study details: Retrospective single-center cohort study of 626 bariatric surgery patients.

Disclosures: The study authors reported no external sources of funding. Dr. Istfan reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Anderson W et al. Obesity Week 2018, Abstract T-OR-2016.

Biomarker algorithm may offer noninvasive look at liver fibrosis

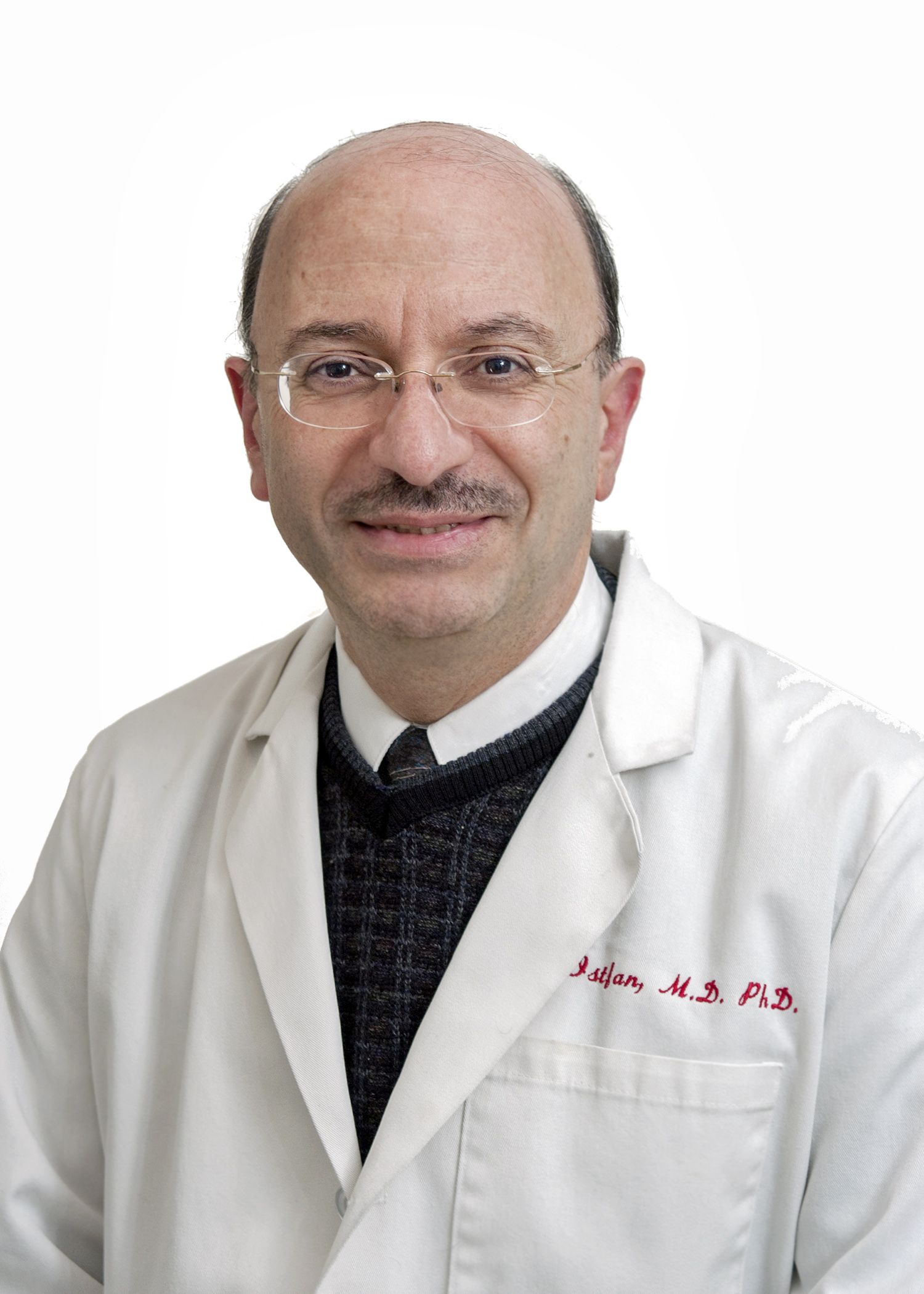

Serum biomarkers may enable a noninvasive method of detecting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to results from a recent study.

An algorithm created by the investigators distinguished NAFLD patients with advanced liver fibrosis from those with mild to moderate fibrosis, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California at San Diego and his colleagues.

“Liver biopsy is currently the gold standard for diagnosing NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] and staging liver fibrosis,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, it is a costly and invasive procedure with an all-cause mortality risk of approximately 0.2%. Liver biopsy typically samples only 1/50,000th of the organ, and it is liable to sampling error with an error rate of 25% for diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis.”

Existing serum-based tests are reliable for diagnosing nonfibrotic NAFLD, but they may misdiagnosis patients with advanced fibrosis. Although imaging-based techniques may provide better diagnostic accuracy, some are available only for subgroups of patients, while others come with a high financial burden. Diagnostic shortcomings may have a major effect on patient outcomes, particularly when risk groups are considered.

“Fibrosis stages F3 and F4 (advanced fibrosis) are primary predictors of liver-related morbidity and mortality, with 11%-22% of NASH patients reported to have advanced fibrosis,” the investigators noted.

The investigators therefore aimed to distinguish such high-risk NAFLD patients from those with mild or moderate liver fibrosis. Three biomarkers were included: hyaluronic acid (HA), TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP-1), and alpha2-macroglobulin (A2M). Each biomarker has documented associations with liver fibrosis. For instance, higher A2M concentrations inhibit fibrinolysis, HA is associated with excessive extracellular matrix and fibrotic tissue, and TIMP-1 is a known liver fibrosis marker and inhibitor of extracellular matrix degradation. The relative strengths of each in detecting advanced liver fibrosis was determined through an algorithm.

The investigators relied on archived serum samples from Duke University, Durham, N.C., (n = 792) and University of California at San Diego (n = 244) that were collected within 11 days of liver biopsy. Biopsies were performed with 15- to 16-gauge needles using at least eight portal tracts, and these samples were used to diagnose NAFLD. Patients with alcoholic liver disease or hepatitis C virus were excluded.

Algorithm training was based on serum measurements from 396 patients treated at Duke University. Samples were divided into mild to moderate (F0-F2) or advanced (F3-F4) fibrosis and split into 10 subsets. The logical regression model was trained on nine subsets and tested on the 10th, with iterations 10 times through this sequence until all 10 samples were tested. This process was repeated 10,000 times. Using the median coefficients from 100,000 logistical regression models, the samples were scored using the algorithm from 0 to 100, with higher numbers representing more advanced fibrosis, and the relative weights of each biomarker measurement were determined.

A noninferiority protocol was used to validate the algorithm, through which the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve was calculated. The AUROC curve of the validation samples was 0.856, with 0.5 being the score for a random algorithm. The algorithm correctly classified 90.0% of F0 cases, 75.0% of F1 cases, 53.8% of F2 cases, 77.4% of F3 cases, and 94.4% of F4 cases. The sensitivity was 79.7% and the specificity was 75.7%.

The algorithm was superior to Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) and NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) in two validation cohorts. In a combination of validation cohorts, the algorithm correctly identified 79.5% of F3-F4 patients, compared with rates of 25.8% and 28.0% from FIB-4 and NFS, respectively. The investigators noted that the algorithm was unaffected by sex or age. In contrast, FIB-4 is biased toward females, and both FIB-4 and NFS are less accurate with patients aged 35 years or younger.

“Performance of the training and validation sets was robust and well matched, enabling the reliable differentiation of NAFLD patients with and without advanced fibrosis,” the investigators concluded.

The study was supported by Prometheus Laboratories. Authors not employed by Prometheus Laboratories were employed by Duke University or the University of California, San Diego; each institution received funding from Prometheus Laboratories.

SOURCE: Loomba R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.11.004.

Serum biomarkers may enable a noninvasive method of detecting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), according to results from a recent study.

An algorithm created by the investigators distinguished NAFLD patients with advanced liver fibrosis from those with mild to moderate fibrosis, reported lead author Rohit Loomba, MD, of the University of California at San Diego and his colleagues.

“Liver biopsy is currently the gold standard for diagnosing NASH [nonalcoholic steatohepatitis] and staging liver fibrosis,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “However, it is a costly and invasive procedure with an all-cause mortality risk of approximately 0.2%. Liver biopsy typically samples only 1/50,000th of the organ, and it is liable to sampling error with an error rate of 25% for diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis.”

Existing serum-based tests are reliable for diagnosing nonfibrotic NAFLD, but they may misdiagnosis patients with advanced fibrosis. Although imaging-based techniques may provide better diagnostic accuracy, some are available only for subgroups of patients, while others come with a high financial burden. Diagnostic shortcomings may have a major effect on patient outcomes, particularly when risk groups are considered.

“Fibrosis stages F3 and F4 (advanced fibrosis) are primary predictors of liver-related morbidity and mortality, with 11%-22% of NASH patients reported to have advanced fibrosis,” the investigators noted.

The investigators therefore aimed to distinguish such high-risk NAFLD patients from those with mild or moderate liver fibrosis. Three biomarkers were included: hyaluronic acid (HA), TIMP metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 (TIMP-1), and alpha2-macroglobulin (A2M). Each biomarker has documented associations with liver fibrosis. For instance, higher A2M concentrations inhibit fibrinolysis, HA is associated with excessive extracellular matrix and fibrotic tissue, and TIMP-1 is a known liver fibrosis marker and inhibitor of extracellular matrix degradation. The relative strengths of each in detecting advanced liver fibrosis was determined through an algorithm.

The investigators relied on archived serum samples from Duke University, Durham, N.C., (n = 792) and University of California at San Diego (n = 244) that were collected within 11 days of liver biopsy. Biopsies were performed with 15- to 16-gauge needles using at least eight portal tracts, and these samples were used to diagnose NAFLD. Patients with alcoholic liver disease or hepatitis C virus were excluded.