User login

Beware of invasive H influenzae disease among pregnant women

Experts generally have not considered H influenzae disease to be a substantial contributor to severely adverse fetal outcomes. Yet new research from England and Wales finds that even though pregnant women in their study tended to be younger and healthier than their nonpregnant counterparts, they were far more likely to develop the invasive unencapsulated form of disease and far more likely to present with bacteremia. Not to mention that almost all of their pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, extremely preterm birth, or, at best, the birth of infants with respiratory distress with or without sepsis.

DETAILS OF THE STUDY

Collins and colleagues queried prospectively general practitioners who cared for women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) with invasive H influenzae disease during the 4-year period of 2009 to 2012. One hundred percent of those queried responded. The study encompassed more than 45 million woman-years of follow-up.

Of the 171 women who developed the infection (confirmed by positive culture from a normally sterile site), approximately 84% (144) had unencapsulated disease. Not quite half (44% or 75) of the 171 women were pregnant at the time of infection. The overall incidence of confirmed invasive H influenzae disease was low at 0.50 per 100,000 women of reproductive age, but the 75 pregnant women were 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-24.1; P<.001) times as likely to develop the infection as the 96 nonpregnant women (2.98/100,000 woman-years versus 0.17/100,000 woman-years, respectively). And, despite being previously healthy, almost three times as many pregnant as nonpregnant women presented with bacteremia (90.3% versus 33.3%, respectively).

Of 47 women who developed unencapsulated H influenzae infection during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, 44 lost the fetus and three had extremely preterm births. Of 28 women who developed the infection during the second half of their pregnancy, two had stillbirths. Eight of the 26 live births were preterm, and 21 of the 26 infants had respiratory distress with or without sepsis at birth. The researchers calculated that the rate of pregnancy loss following invasive H influenzae disease was almost 3 times higher than the average rate of pregnancy loss in England and Wales.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

It is generally reported that up to one-quarter of the approximately 26,000 stillbirths occurring yearly in the United States are due to some type of maternal or fetal infection.2,3 Dr. Morven S. Edwards, in an editorial4 appearing in the same issue of JAMA as the study, comments, “Given the magnitude of the burden of perinatal deaths, clarifying the extent that bacterial infections result in stillbirth and preterm delivery could potentially inform interventions to improve child and maternal health globally.”

Experts generally have not considered H influenzae disease to be a substantial contributor to severely adverse fetal outcomes. Yet new research from England and Wales finds that even though pregnant women in their study tended to be younger and healthier than their nonpregnant counterparts, they were far more likely to develop the invasive unencapsulated form of disease and far more likely to present with bacteremia. Not to mention that almost all of their pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, extremely preterm birth, or, at best, the birth of infants with respiratory distress with or without sepsis.

DETAILS OF THE STUDY

Collins and colleagues queried prospectively general practitioners who cared for women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) with invasive H influenzae disease during the 4-year period of 2009 to 2012. One hundred percent of those queried responded. The study encompassed more than 45 million woman-years of follow-up.

Of the 171 women who developed the infection (confirmed by positive culture from a normally sterile site), approximately 84% (144) had unencapsulated disease. Not quite half (44% or 75) of the 171 women were pregnant at the time of infection. The overall incidence of confirmed invasive H influenzae disease was low at 0.50 per 100,000 women of reproductive age, but the 75 pregnant women were 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-24.1; P<.001) times as likely to develop the infection as the 96 nonpregnant women (2.98/100,000 woman-years versus 0.17/100,000 woman-years, respectively). And, despite being previously healthy, almost three times as many pregnant as nonpregnant women presented with bacteremia (90.3% versus 33.3%, respectively).

Of 47 women who developed unencapsulated H influenzae infection during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, 44 lost the fetus and three had extremely preterm births. Of 28 women who developed the infection during the second half of their pregnancy, two had stillbirths. Eight of the 26 live births were preterm, and 21 of the 26 infants had respiratory distress with or without sepsis at birth. The researchers calculated that the rate of pregnancy loss following invasive H influenzae disease was almost 3 times higher than the average rate of pregnancy loss in England and Wales.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

It is generally reported that up to one-quarter of the approximately 26,000 stillbirths occurring yearly in the United States are due to some type of maternal or fetal infection.2,3 Dr. Morven S. Edwards, in an editorial4 appearing in the same issue of JAMA as the study, comments, “Given the magnitude of the burden of perinatal deaths, clarifying the extent that bacterial infections result in stillbirth and preterm delivery could potentially inform interventions to improve child and maternal health globally.”

Experts generally have not considered H influenzae disease to be a substantial contributor to severely adverse fetal outcomes. Yet new research from England and Wales finds that even though pregnant women in their study tended to be younger and healthier than their nonpregnant counterparts, they were far more likely to develop the invasive unencapsulated form of disease and far more likely to present with bacteremia. Not to mention that almost all of their pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, extremely preterm birth, or, at best, the birth of infants with respiratory distress with or without sepsis.

DETAILS OF THE STUDY

Collins and colleagues queried prospectively general practitioners who cared for women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) with invasive H influenzae disease during the 4-year period of 2009 to 2012. One hundred percent of those queried responded. The study encompassed more than 45 million woman-years of follow-up.

Of the 171 women who developed the infection (confirmed by positive culture from a normally sterile site), approximately 84% (144) had unencapsulated disease. Not quite half (44% or 75) of the 171 women were pregnant at the time of infection. The overall incidence of confirmed invasive H influenzae disease was low at 0.50 per 100,000 women of reproductive age, but the 75 pregnant women were 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-24.1; P<.001) times as likely to develop the infection as the 96 nonpregnant women (2.98/100,000 woman-years versus 0.17/100,000 woman-years, respectively). And, despite being previously healthy, almost three times as many pregnant as nonpregnant women presented with bacteremia (90.3% versus 33.3%, respectively).

Of 47 women who developed unencapsulated H influenzae infection during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, 44 lost the fetus and three had extremely preterm births. Of 28 women who developed the infection during the second half of their pregnancy, two had stillbirths. Eight of the 26 live births were preterm, and 21 of the 26 infants had respiratory distress with or without sepsis at birth. The researchers calculated that the rate of pregnancy loss following invasive H influenzae disease was almost 3 times higher than the average rate of pregnancy loss in England and Wales.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

It is generally reported that up to one-quarter of the approximately 26,000 stillbirths occurring yearly in the United States are due to some type of maternal or fetal infection.2,3 Dr. Morven S. Edwards, in an editorial4 appearing in the same issue of JAMA as the study, comments, “Given the magnitude of the burden of perinatal deaths, clarifying the extent that bacterial infections result in stillbirth and preterm delivery could potentially inform interventions to improve child and maternal health globally.”

FDA panel considers human studies of modified oocytes for preventing disease

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – The first human studies evaluating the use of genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases could enroll women with diseases that are the most severe, tend to present in early childhood, and are relatively common for a mitochondrial disease, according to panelists at a meeting convened by the Food and Drug Administration to discuss the design of such trials and related issues.

At a meeting on Feb. 25 and 26, members of the FDA Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee mentioned two mitochondrial diseases in particular, Leigh’s disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes), that could be included in initial clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of what the FDA refers to as "mitochondrial manipulation technologies."

This controversial approach, which is being developed to prevent maternal transmission of debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases, entails removing the mitochondrial DNA from an affected woman’s oocyte or embryo and replacing it via assisted reproductive technologies with the mitochondrial DNA from the egg of a healthy donor.

The approach has been studied in animal and in vitro studies, but not yet in humans. However, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland, say they are ready to start a clinical trial based on their results in macaque monkeys.

The FDA called the 2-day meeting to discuss potential clinical trials and to focus on the scientific, technologic, and clinical aspects of the technologies, but not to address public policy or ethical issues. In briefing documents posted before the meeting, the agency acknowledged that there are ethical and policy issues related to genetic modification of eggs and embryos, which can affect regulatory decisions, but added that these issues were "outside the scope" of this meeting.

Regarding clinical trial design and execution, panelists recommended that studies should closely monitor the fetus through gestation, and after birth and long-term follow-up, should include future generations, if female offspring are included. Several panelists supported including only male embryos to minimize the risk of a female passing on damaged DNA to future generations, while others said this would result in a lost opportunity to study the transgenerational risks of the technology.

Other recommendations included avoiding the enrollment of people at high risk of having a baby with a birth defect, or with comorbidities that could affect birth outcome, which would make it more difficult to evaluate the risks of the technologies. The use of controls, panelists said, was problematic, because of the variability in when and how mitochondrial diseases present and because of the relatively small populations of patients affected by these diseases. Historical controls could be used, but larger patient registries are needed, they said.

Panelists also recommended screening egg donors for mitochondrial diseases, and providing informed consent to children born to mothers in the trials when they turn age 18.

It is clear that there is a "deft group of creative, innovative investigators" who can perform these techniques, "which is a good start, but there are so many things we don’t know" that must be evaluated further in animal studies, said panelist Dr. David Keefe, who referred to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) as historical examples of therapies that were thought to be promising but proved to have devastating effects.

Another concern Dr. Keefe raised was the possibility that a woman whose risk of having a baby without the inherited defect might be as high as 95% and that she might choose mitochondrial manipulation over preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

"A woman could be led down the primrose path towards a procedure that’s experimental and miss the opportunity to pursue a relatively well-established procedure," said Dr. Keefe, the Stanley H. Kaplan Professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, New York University.

Another panelist, Dr. Katharine Wenstrom, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University, Providence, R.I., said that based on her experience with women with genetic diseases, these women "are very vulnerable, and my concern would be how to [provide] consent [for] somebody for whom a pregnancy would be very dangerous and [who] might not consider a pregnancy, but then given the opportunity to have this technique, might agree to a pregnancy that could actually be life threatening."

She also said that she was concerned about whether the technique could deplete mitochondria, which has been associated with several forms of cancer, and about the "inability to ensure that the technique has not inflicted some new abnormality" on the child.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., whose research group at the Oregon Stem Cell Center at OHSU has tested the technology in macaque monkeys, said that their research cohort currently includes four subjects born through mitochondrial manipulation that are almost adults. To date, they have been healthy, with normal blood test results, and are no different from controls, showing that mitochondrial DNA in oocytes can be replaced.

The next step in their research is to recruit families who are carriers of early-onset mitochondrial DNA diseases who have had at least one affected child, recruit healthy egg donors, and then perform the procedure, followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis of the embryo and/or prenatal diagnosis to "ensure complete mitochondrial DNA replacement and chromosomal normalcy," he said.

The panel was also asked to discuss the use of mitochondrial manipulation as a treatment for infertility. However, members considered this indication a far different type of application than preventing mitochondrial disease, which would have different inclusion criteria, controls, and risk-benefit evaluations, and several panelists raised particular concerns about the use of this technology for infertility.

"The idea we’re going to do anything to infertility patients involving mitochondria I think should be off the table," Dr. Keefe said, noting that there is "a very, very slippery slope when you’re dealing with human reproduction" in the United States, where licensure of infertility clinics is not required.

The controversies of this area of research, which some critics point out would result in a child with three genetically related parents, were not off limits to the open public hearing speakers, including Marcy Darnovsky, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society.

"We want to avoid waking up in a world" where researchers, infertility clinics, governments, insurance companies, "or parents decide that they are going to try to engineer children with specific traits and even possibly [put] in motion a regime of high-tech consumer eugenics," she said.

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – The first human studies evaluating the use of genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases could enroll women with diseases that are the most severe, tend to present in early childhood, and are relatively common for a mitochondrial disease, according to panelists at a meeting convened by the Food and Drug Administration to discuss the design of such trials and related issues.

At a meeting on Feb. 25 and 26, members of the FDA Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee mentioned two mitochondrial diseases in particular, Leigh’s disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes), that could be included in initial clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of what the FDA refers to as "mitochondrial manipulation technologies."

This controversial approach, which is being developed to prevent maternal transmission of debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases, entails removing the mitochondrial DNA from an affected woman’s oocyte or embryo and replacing it via assisted reproductive technologies with the mitochondrial DNA from the egg of a healthy donor.

The approach has been studied in animal and in vitro studies, but not yet in humans. However, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland, say they are ready to start a clinical trial based on their results in macaque monkeys.

The FDA called the 2-day meeting to discuss potential clinical trials and to focus on the scientific, technologic, and clinical aspects of the technologies, but not to address public policy or ethical issues. In briefing documents posted before the meeting, the agency acknowledged that there are ethical and policy issues related to genetic modification of eggs and embryos, which can affect regulatory decisions, but added that these issues were "outside the scope" of this meeting.

Regarding clinical trial design and execution, panelists recommended that studies should closely monitor the fetus through gestation, and after birth and long-term follow-up, should include future generations, if female offspring are included. Several panelists supported including only male embryos to minimize the risk of a female passing on damaged DNA to future generations, while others said this would result in a lost opportunity to study the transgenerational risks of the technology.

Other recommendations included avoiding the enrollment of people at high risk of having a baby with a birth defect, or with comorbidities that could affect birth outcome, which would make it more difficult to evaluate the risks of the technologies. The use of controls, panelists said, was problematic, because of the variability in when and how mitochondrial diseases present and because of the relatively small populations of patients affected by these diseases. Historical controls could be used, but larger patient registries are needed, they said.

Panelists also recommended screening egg donors for mitochondrial diseases, and providing informed consent to children born to mothers in the trials when they turn age 18.

It is clear that there is a "deft group of creative, innovative investigators" who can perform these techniques, "which is a good start, but there are so many things we don’t know" that must be evaluated further in animal studies, said panelist Dr. David Keefe, who referred to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) as historical examples of therapies that were thought to be promising but proved to have devastating effects.

Another concern Dr. Keefe raised was the possibility that a woman whose risk of having a baby without the inherited defect might be as high as 95% and that she might choose mitochondrial manipulation over preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

"A woman could be led down the primrose path towards a procedure that’s experimental and miss the opportunity to pursue a relatively well-established procedure," said Dr. Keefe, the Stanley H. Kaplan Professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, New York University.

Another panelist, Dr. Katharine Wenstrom, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University, Providence, R.I., said that based on her experience with women with genetic diseases, these women "are very vulnerable, and my concern would be how to [provide] consent [for] somebody for whom a pregnancy would be very dangerous and [who] might not consider a pregnancy, but then given the opportunity to have this technique, might agree to a pregnancy that could actually be life threatening."

She also said that she was concerned about whether the technique could deplete mitochondria, which has been associated with several forms of cancer, and about the "inability to ensure that the technique has not inflicted some new abnormality" on the child.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., whose research group at the Oregon Stem Cell Center at OHSU has tested the technology in macaque monkeys, said that their research cohort currently includes four subjects born through mitochondrial manipulation that are almost adults. To date, they have been healthy, with normal blood test results, and are no different from controls, showing that mitochondrial DNA in oocytes can be replaced.

The next step in their research is to recruit families who are carriers of early-onset mitochondrial DNA diseases who have had at least one affected child, recruit healthy egg donors, and then perform the procedure, followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis of the embryo and/or prenatal diagnosis to "ensure complete mitochondrial DNA replacement and chromosomal normalcy," he said.

The panel was also asked to discuss the use of mitochondrial manipulation as a treatment for infertility. However, members considered this indication a far different type of application than preventing mitochondrial disease, which would have different inclusion criteria, controls, and risk-benefit evaluations, and several panelists raised particular concerns about the use of this technology for infertility.

"The idea we’re going to do anything to infertility patients involving mitochondria I think should be off the table," Dr. Keefe said, noting that there is "a very, very slippery slope when you’re dealing with human reproduction" in the United States, where licensure of infertility clinics is not required.

The controversies of this area of research, which some critics point out would result in a child with three genetically related parents, were not off limits to the open public hearing speakers, including Marcy Darnovsky, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society.

"We want to avoid waking up in a world" where researchers, infertility clinics, governments, insurance companies, "or parents decide that they are going to try to engineer children with specific traits and even possibly [put] in motion a regime of high-tech consumer eugenics," she said.

GAITHERSBURG, MD. – The first human studies evaluating the use of genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases could enroll women with diseases that are the most severe, tend to present in early childhood, and are relatively common for a mitochondrial disease, according to panelists at a meeting convened by the Food and Drug Administration to discuss the design of such trials and related issues.

At a meeting on Feb. 25 and 26, members of the FDA Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee mentioned two mitochondrial diseases in particular, Leigh’s disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes), that could be included in initial clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of what the FDA refers to as "mitochondrial manipulation technologies."

This controversial approach, which is being developed to prevent maternal transmission of debilitating and often fatal mitochondrial diseases, entails removing the mitochondrial DNA from an affected woman’s oocyte or embryo and replacing it via assisted reproductive technologies with the mitochondrial DNA from the egg of a healthy donor.

The approach has been studied in animal and in vitro studies, but not yet in humans. However, researchers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), Portland, say they are ready to start a clinical trial based on their results in macaque monkeys.

The FDA called the 2-day meeting to discuss potential clinical trials and to focus on the scientific, technologic, and clinical aspects of the technologies, but not to address public policy or ethical issues. In briefing documents posted before the meeting, the agency acknowledged that there are ethical and policy issues related to genetic modification of eggs and embryos, which can affect regulatory decisions, but added that these issues were "outside the scope" of this meeting.

Regarding clinical trial design and execution, panelists recommended that studies should closely monitor the fetus through gestation, and after birth and long-term follow-up, should include future generations, if female offspring are included. Several panelists supported including only male embryos to minimize the risk of a female passing on damaged DNA to future generations, while others said this would result in a lost opportunity to study the transgenerational risks of the technology.

Other recommendations included avoiding the enrollment of people at high risk of having a baby with a birth defect, or with comorbidities that could affect birth outcome, which would make it more difficult to evaluate the risks of the technologies. The use of controls, panelists said, was problematic, because of the variability in when and how mitochondrial diseases present and because of the relatively small populations of patients affected by these diseases. Historical controls could be used, but larger patient registries are needed, they said.

Panelists also recommended screening egg donors for mitochondrial diseases, and providing informed consent to children born to mothers in the trials when they turn age 18.

It is clear that there is a "deft group of creative, innovative investigators" who can perform these techniques, "which is a good start, but there are so many things we don’t know" that must be evaluated further in animal studies, said panelist Dr. David Keefe, who referred to thalidomide and diethylstilbestrol (DES) as historical examples of therapies that were thought to be promising but proved to have devastating effects.

Another concern Dr. Keefe raised was the possibility that a woman whose risk of having a baby without the inherited defect might be as high as 95% and that she might choose mitochondrial manipulation over preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

"A woman could be led down the primrose path towards a procedure that’s experimental and miss the opportunity to pursue a relatively well-established procedure," said Dr. Keefe, the Stanley H. Kaplan Professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, New York University.

Another panelist, Dr. Katharine Wenstrom, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, Brown University, Providence, R.I., said that based on her experience with women with genetic diseases, these women "are very vulnerable, and my concern would be how to [provide] consent [for] somebody for whom a pregnancy would be very dangerous and [who] might not consider a pregnancy, but then given the opportunity to have this technique, might agree to a pregnancy that could actually be life threatening."

She also said that she was concerned about whether the technique could deplete mitochondria, which has been associated with several forms of cancer, and about the "inability to ensure that the technique has not inflicted some new abnormality" on the child.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, Ph.D., whose research group at the Oregon Stem Cell Center at OHSU has tested the technology in macaque monkeys, said that their research cohort currently includes four subjects born through mitochondrial manipulation that are almost adults. To date, they have been healthy, with normal blood test results, and are no different from controls, showing that mitochondrial DNA in oocytes can be replaced.

The next step in their research is to recruit families who are carriers of early-onset mitochondrial DNA diseases who have had at least one affected child, recruit healthy egg donors, and then perform the procedure, followed by preimplantation genetic diagnosis of the embryo and/or prenatal diagnosis to "ensure complete mitochondrial DNA replacement and chromosomal normalcy," he said.

The panel was also asked to discuss the use of mitochondrial manipulation as a treatment for infertility. However, members considered this indication a far different type of application than preventing mitochondrial disease, which would have different inclusion criteria, controls, and risk-benefit evaluations, and several panelists raised particular concerns about the use of this technology for infertility.

"The idea we’re going to do anything to infertility patients involving mitochondria I think should be off the table," Dr. Keefe said, noting that there is "a very, very slippery slope when you’re dealing with human reproduction" in the United States, where licensure of infertility clinics is not required.

The controversies of this area of research, which some critics point out would result in a child with three genetically related parents, were not off limits to the open public hearing speakers, including Marcy Darnovsky, Ph.D., executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society.

"We want to avoid waking up in a world" where researchers, infertility clinics, governments, insurance companies, "or parents decide that they are going to try to engineer children with specific traits and even possibly [put] in motion a regime of high-tech consumer eugenics," she said.

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

VIDEO: Oocyte modification might prevent mitochondrial diseases

Clinical trials using genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases in humans may be soon become a reality. But the potentially promising approach to prevent conditions such as Leigh disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) is not without controversy.

In an interview, Dr. Salvatore DiMauro, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, outlined the impact that mitochondrial DNA–related diseases have on women’s and children’s lives, and he explained why genetically modified oocytes may offer new hope for those affected by these diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Clinical trials using genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases in humans may be soon become a reality. But the potentially promising approach to prevent conditions such as Leigh disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) is not without controversy.

In an interview, Dr. Salvatore DiMauro, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, outlined the impact that mitochondrial DNA–related diseases have on women’s and children’s lives, and he explained why genetically modified oocytes may offer new hope for those affected by these diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Clinical trials using genetically modified oocytes to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases in humans may be soon become a reality. But the potentially promising approach to prevent conditions such as Leigh disease and MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) is not without controversy.

In an interview, Dr. Salvatore DiMauro, the Lucy G. Moses Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center, outlined the impact that mitochondrial DNA–related diseases have on women’s and children’s lives, and he explained why genetically modified oocytes may offer new hope for those affected by these diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT AN FDA ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING

Aspirin for Preeclampsia Prevention?

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Draft recommendations back aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

Prophylactic low-dose aspirin – 81 mg per day – should be started after 12 weeks’ gestation in women at high risk for developing preeclampsia, according to a draft recommendation issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in April.

The recommendation applies to asymptomatic pregnant women at increased risk for preeclampsia who have no contraindications to using low-dose aspirin and have not experienced adverse effects associated with aspirin previously.

"The USPSTF found adequate evidence of a reduction in preeclampsia, preterm birth, and IUGR [intrauterine growth restriction] in women at increased risk for preeclampsia who received low-dose aspirin, thus demonstrating substantial benefit," the recommendations state. In a review of clinical trials, low-dose aspirin (at doses of 50-160 mg per day) reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 24%, the risk of preterm birth by 14%, and the risk of IUGR by 20%. There also was "adequate evidence" that the risks of placental abruption, postpartum hemorrhage, and fetal intracranial bleeding were not increased with low-dose aspirin, the USPSTF statement said.

The draft recommendations were based on a review of data on low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia in 23 studies of women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, which was published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M13-2844).

The recommendation is considered a "B" recommendation, defined as one that has a "high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial." The statement includes a table to help identify patients who are at an increased risk of preeclampsia.

The last statement about low-dose aspirin and preeclampsia, issued by the USPSTF in 1996, concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a recommendation for or against the use of aspirin for preventing preeclampsia. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends low-dose aspirin, starting late in the first trimester, in women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and preterm delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation, or a history of preeclampsia in more than one previous pregnancy.

The USPSTF is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine, which includes ob.gyns., pediatricians, family physicians, nurses, and health behavior specialists, according to the USPSTF website.

The draft recommendations are available here. Comments on the recommendations can be submitted via the website until May 5, 2014, at 5 p.m. EST.

CDC: Young teens’ birth rates drop 67%

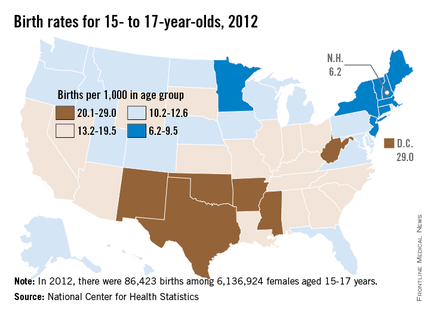

Despite a 67% drop in the birth rate among teens aged 15-17 years over the past 2 decades, there is still plenty of room for improvement, according to a report issued April 8 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years fell from 51.9 in 1991 to 17.0 in 2012, a 67% drop. In 2012, 86,423 teens aged 15-17 years gave birth, which accounted for 28.3% of all births among teens aged 15-19 years. That’s down from 36% of all births to teens 15-19 years in 1991.

The rates among 15- to 17-year-olds varied widely by state and by ethnic and racial groups, with the highest rates among Hispanics (25.5 births per 1,000 teens) and non-Hispanic blacks (21.9), followed by American Indians/Alaska Natives (17.0). The lowest rates were among non-Hispanic whites and Asian/Pacific Islanders, at 8.4 and 4.1 births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years, respectively.

The researchers found no significant racial or ethnic differences in the percentage of female teens 15-17 years old who were sexually experienced or currently sexually active.

Across the United States, the rates among teens aged 15-17 years were the lowest in New Hampshire – 6.2 per 1,000 – and were highest in the District of Columbia – 29 per 1,000.

Among the report’s other findings:

• Between 2006 and 2010, 18% of female teens aged 15-17 years were sexually active.

• 90.9% of female teens aged 15-17 years had received formal sex education on either birth control or how to say no to sex, but only 61.3% received information on both topics.

• 23.6% had not discussed with their parents either saying no to sex or how to use contraceptives.

• 51.8% of the sexually active female 15- to 17-year-olds relied on less effective contraceptives, usually condoms, while 7.8% used no contraception.

• The most effective contraceptives, long-acting reversible contraceptives such as an intrauterine device, were used by 1% of sexually active females aged 15-17 years.

Previous research suggested the 55% drop in pregnancies among 15- to 17-year-olds from 1995 through 2002 was because of changes in contraceptive use (accounting for 77% of the decline) and a decrease in sexual activity (responsible for 23% of the decline), the report’s authors noted. Therefore, they recommended that "efforts to prevent pregnancy in this population should take a multifaceted approach, including the promotion of delayed sexual initiation and the use of more effective contraceptive methods."

The report’s findings "are a reminder that we as health professionals have a special duty to give young people the necessary knowledge, the skills, and the encouragement to make healthy decisions and engage in healthy behaviors," explained Ileana Arias, Ph.D., principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, during a telephone briefing.

The report is based on the CDC’s analysis of data on births from the National Vital Statistics System from 1991 to 2012 and on teen health behaviors from the National Survey of Family Growth from 2006 to 2010. The results were published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2014;63:1-7).

Dr. Arias pointed out that the ages of 15, 16, and 17 years "are a critical time when a teen, especially a young woman, could jeopardize her future if she can’t complete high school or go to college."

While it is encouraging that adolescent birth rates

continue to decline, the United

States continues to have one of the highest

adolescent birth rates of any developed country in the world. It is

particularly concerning that Hispanic and non-Hispanic black adolescents

continue to have about three times the birth rates of non-Hispanic white adolescents.

Equally alarming is that the majority of adolescents

report no formal sex education before their first sexual encounter. As a

community, we need to better prepare our young adolescents with evidence-based

information about sexual activity, contraception methods, and pregnancy. Just

as we vaccinate our community’s children to prevent illness, we need to talk to

our youth about sexual risk behaviors and what they can do to protect

themselves from pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and exploitation,

and to negotiate sexual relationships in a healthy manner. Parents and

educators need to have these conversations prior to sexual activity, so that

our youth can be prepared and protected, just as we do with vaccinations.

Providers and educators

can better prepare parents to have these discussions with young adolescents. There are many pregnancy prevention

programs, but not all of them have been proven to be effective. It is critical

that we use our limited resources in the employment of proven pregnancy

prevention programs.

This report highlights the adolescent birth trend from

1991 to 2012. There are many more effective contraceptive methods available

now, as compared to 1991. However, only 1% of adolescents are using the most

effective methods, which include intrauterine and implant contraception. Providers

can contribute to future declines in adolescent birth rates by educating

themselves about these contraceptive methods and counseling our youth about the

efficacy, safety, and satisfaction of intrauterine and implant contraceptives.

Dr. Amanda Jacobs is a pediatrician in the division of

adolescent medicine at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Jacobs had no relevant disclosures.

sex education

While it is encouraging that adolescent birth rates

continue to decline, the United

States continues to have one of the highest

adolescent birth rates of any developed country in the world. It is

particularly concerning that Hispanic and non-Hispanic black adolescents

continue to have about three times the birth rates of non-Hispanic white adolescents.

Equally alarming is that the majority of adolescents

report no formal sex education before their first sexual encounter. As a

community, we need to better prepare our young adolescents with evidence-based

information about sexual activity, contraception methods, and pregnancy. Just

as we vaccinate our community’s children to prevent illness, we need to talk to

our youth about sexual risk behaviors and what they can do to protect

themselves from pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and exploitation,

and to negotiate sexual relationships in a healthy manner. Parents and

educators need to have these conversations prior to sexual activity, so that

our youth can be prepared and protected, just as we do with vaccinations.

Providers and educators

can better prepare parents to have these discussions with young adolescents. There are many pregnancy prevention

programs, but not all of them have been proven to be effective. It is critical

that we use our limited resources in the employment of proven pregnancy

prevention programs.

This report highlights the adolescent birth trend from

1991 to 2012. There are many more effective contraceptive methods available

now, as compared to 1991. However, only 1% of adolescents are using the most

effective methods, which include intrauterine and implant contraception. Providers

can contribute to future declines in adolescent birth rates by educating

themselves about these contraceptive methods and counseling our youth about the

efficacy, safety, and satisfaction of intrauterine and implant contraceptives.

Dr. Amanda Jacobs is a pediatrician in the division of

adolescent medicine at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Jacobs had no relevant disclosures.

While it is encouraging that adolescent birth rates

continue to decline, the United

States continues to have one of the highest

adolescent birth rates of any developed country in the world. It is

particularly concerning that Hispanic and non-Hispanic black adolescents

continue to have about three times the birth rates of non-Hispanic white adolescents.

Equally alarming is that the majority of adolescents

report no formal sex education before their first sexual encounter. As a

community, we need to better prepare our young adolescents with evidence-based

information about sexual activity, contraception methods, and pregnancy. Just

as we vaccinate our community’s children to prevent illness, we need to talk to

our youth about sexual risk behaviors and what they can do to protect

themselves from pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and exploitation,

and to negotiate sexual relationships in a healthy manner. Parents and

educators need to have these conversations prior to sexual activity, so that

our youth can be prepared and protected, just as we do with vaccinations.

Providers and educators

can better prepare parents to have these discussions with young adolescents. There are many pregnancy prevention

programs, but not all of them have been proven to be effective. It is critical

that we use our limited resources in the employment of proven pregnancy

prevention programs.

This report highlights the adolescent birth trend from

1991 to 2012. There are many more effective contraceptive methods available

now, as compared to 1991. However, only 1% of adolescents are using the most

effective methods, which include intrauterine and implant contraception. Providers

can contribute to future declines in adolescent birth rates by educating

themselves about these contraceptive methods and counseling our youth about the

efficacy, safety, and satisfaction of intrauterine and implant contraceptives.

Dr. Amanda Jacobs is a pediatrician in the division of

adolescent medicine at the Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, N.Y. Dr. Jacobs had no relevant disclosures.

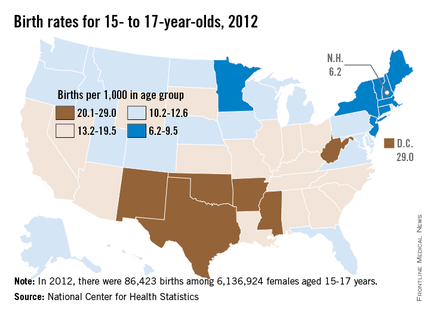

Despite a 67% drop in the birth rate among teens aged 15-17 years over the past 2 decades, there is still plenty of room for improvement, according to a report issued April 8 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years fell from 51.9 in 1991 to 17.0 in 2012, a 67% drop. In 2012, 86,423 teens aged 15-17 years gave birth, which accounted for 28.3% of all births among teens aged 15-19 years. That’s down from 36% of all births to teens 15-19 years in 1991.

The rates among 15- to 17-year-olds varied widely by state and by ethnic and racial groups, with the highest rates among Hispanics (25.5 births per 1,000 teens) and non-Hispanic blacks (21.9), followed by American Indians/Alaska Natives (17.0). The lowest rates were among non-Hispanic whites and Asian/Pacific Islanders, at 8.4 and 4.1 births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years, respectively.

The researchers found no significant racial or ethnic differences in the percentage of female teens 15-17 years old who were sexually experienced or currently sexually active.

Across the United States, the rates among teens aged 15-17 years were the lowest in New Hampshire – 6.2 per 1,000 – and were highest in the District of Columbia – 29 per 1,000.

Among the report’s other findings:

• Between 2006 and 2010, 18% of female teens aged 15-17 years were sexually active.

• 90.9% of female teens aged 15-17 years had received formal sex education on either birth control or how to say no to sex, but only 61.3% received information on both topics.

• 23.6% had not discussed with their parents either saying no to sex or how to use contraceptives.

• 51.8% of the sexually active female 15- to 17-year-olds relied on less effective contraceptives, usually condoms, while 7.8% used no contraception.

• The most effective contraceptives, long-acting reversible contraceptives such as an intrauterine device, were used by 1% of sexually active females aged 15-17 years.

Previous research suggested the 55% drop in pregnancies among 15- to 17-year-olds from 1995 through 2002 was because of changes in contraceptive use (accounting for 77% of the decline) and a decrease in sexual activity (responsible for 23% of the decline), the report’s authors noted. Therefore, they recommended that "efforts to prevent pregnancy in this population should take a multifaceted approach, including the promotion of delayed sexual initiation and the use of more effective contraceptive methods."

The report’s findings "are a reminder that we as health professionals have a special duty to give young people the necessary knowledge, the skills, and the encouragement to make healthy decisions and engage in healthy behaviors," explained Ileana Arias, Ph.D., principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, during a telephone briefing.

The report is based on the CDC’s analysis of data on births from the National Vital Statistics System from 1991 to 2012 and on teen health behaviors from the National Survey of Family Growth from 2006 to 2010. The results were published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2014;63:1-7).

Dr. Arias pointed out that the ages of 15, 16, and 17 years "are a critical time when a teen, especially a young woman, could jeopardize her future if she can’t complete high school or go to college."

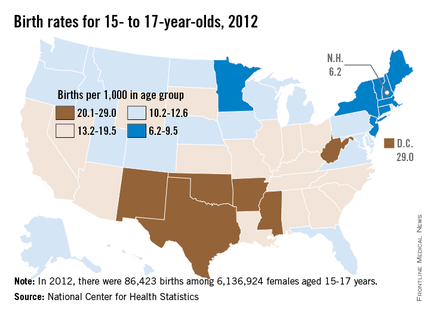

Despite a 67% drop in the birth rate among teens aged 15-17 years over the past 2 decades, there is still plenty of room for improvement, according to a report issued April 8 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years fell from 51.9 in 1991 to 17.0 in 2012, a 67% drop. In 2012, 86,423 teens aged 15-17 years gave birth, which accounted for 28.3% of all births among teens aged 15-19 years. That’s down from 36% of all births to teens 15-19 years in 1991.

The rates among 15- to 17-year-olds varied widely by state and by ethnic and racial groups, with the highest rates among Hispanics (25.5 births per 1,000 teens) and non-Hispanic blacks (21.9), followed by American Indians/Alaska Natives (17.0). The lowest rates were among non-Hispanic whites and Asian/Pacific Islanders, at 8.4 and 4.1 births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years, respectively.

The researchers found no significant racial or ethnic differences in the percentage of female teens 15-17 years old who were sexually experienced or currently sexually active.

Across the United States, the rates among teens aged 15-17 years were the lowest in New Hampshire – 6.2 per 1,000 – and were highest in the District of Columbia – 29 per 1,000.

Among the report’s other findings:

• Between 2006 and 2010, 18% of female teens aged 15-17 years were sexually active.

• 90.9% of female teens aged 15-17 years had received formal sex education on either birth control or how to say no to sex, but only 61.3% received information on both topics.

• 23.6% had not discussed with their parents either saying no to sex or how to use contraceptives.

• 51.8% of the sexually active female 15- to 17-year-olds relied on less effective contraceptives, usually condoms, while 7.8% used no contraception.

• The most effective contraceptives, long-acting reversible contraceptives such as an intrauterine device, were used by 1% of sexually active females aged 15-17 years.

Previous research suggested the 55% drop in pregnancies among 15- to 17-year-olds from 1995 through 2002 was because of changes in contraceptive use (accounting for 77% of the decline) and a decrease in sexual activity (responsible for 23% of the decline), the report’s authors noted. Therefore, they recommended that "efforts to prevent pregnancy in this population should take a multifaceted approach, including the promotion of delayed sexual initiation and the use of more effective contraceptive methods."

The report’s findings "are a reminder that we as health professionals have a special duty to give young people the necessary knowledge, the skills, and the encouragement to make healthy decisions and engage in healthy behaviors," explained Ileana Arias, Ph.D., principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, during a telephone briefing.

The report is based on the CDC’s analysis of data on births from the National Vital Statistics System from 1991 to 2012 and on teen health behaviors from the National Survey of Family Growth from 2006 to 2010. The results were published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2014;63:1-7).

Dr. Arias pointed out that the ages of 15, 16, and 17 years "are a critical time when a teen, especially a young woman, could jeopardize her future if she can’t complete high school or go to college."

sex education

sex education

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

Major finding: The rate of births per 1,000 teens aged 15-17 years fell from 51.9 in 1991 to 17.0 in 2012, a 67% drop.

Data source: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) analyzed data on teen births from the National Vital Statistics System from 1991 to 2012 and teen health behaviors, including contraceptive use, from the National Survey of Family Growth from 2006 to 2010.

Disclosures: This is a CDC report.

Review of studies finds lower preeclampsia risk with prenatal aspirin

The use of low-dose aspirin during pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk of preeclampsia in women at high risk, and did not appear to be associated with harmful effects, in a systematic review of 23 studies of low-dose aspirin in women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, the authors reported.

In women at high risk for preeclampsia, "available evidence indicates modest effects but important benefits of daily low-dose aspirin for prevention of the condition and consequent illness," concluded Jillian Henderson, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Ore., and her associates.

However, the review had limitations and could not rule out rare or long-term risks of treatment, they said. In addition, more studies are needed, including more in black women, who are disproportionately affected by preeclampsia in the United States.

The study of the effects of low-dose aspirin on the risk of preeclampsia and other maternal and fetal outcomes is being published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (www.annals.org).

The review, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), was conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The USPSTF will post a draft recommendation, based on this review, as an update to the USPSTF 1996 recommendation (which is not active).

The authors reviewed 23 studies of low-dose aspirin in women at high or average risk of preeclampsia with a mean age of 20-31 years; these included randomized controlled studies and observational studies. Treatment was not started before 12 weeks in any of the studies, but was started before 16 weeks in 8 studies. With the exception of six studies, treatment was continued until delivery. In most of the studies, daily aspirin doses ranged from 60 to 100 mg.

The use of aspirin was associated with a 24% reduced risk of preeclampsia in the studies of high-risk women. The dosage or timing (started before or after 16 weeks) did not have an effect on risk. The reduced risk was greater in the studies that used doses higher than 75 mg, but this difference was not significant, the authors reported.

The use of aspirin was associated with a 20% reduced risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and a 14% reduced risk of preterm birth, they reported, adding that the addition of negative studies could make these associations nonsignificant.

In the discussion, the authors said that their confidence in the magnitude of these results was "tempered by evidence of small-study effects and modest findings" in the two largest studies. Therefore, a more conservative estimate for the reduced risk of these outcomes – preeclampsia, IUGR, and preterm birth – was "closer to 10%," they wrote.

They did not identify any harmful effects of aspirin to the baby or mother, but "potential rare or long-term harms could not be ruled out," they concluded. There was some evidence of a possible increased risk in placental abruption, but the associations were not statistically significant. There was no evidence that perinatal mortality was increased, and the data suggested there was "possibly a benefit" on mortality favoring low-dose aspirin.

Their analyses also did not find evidence that low-dose aspirin increased the risk of postpartum hemorrhage or increased mean blood loss or the risk of intracranial hemorrhage in newborns.

The long-term follow-up data on infants (up to age 18 months) available in one study did not show differences in hospital visits, gross motor development, or height and weight between infants exposed to aspirin and those not exposed to aspirin.

Among the limitations of the study was the fact that only studies considered "fair to good quality" were included, and that the smaller studies did not capture any rare events such as perinatal death or placental abruption.

The review was conducted by the Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center, under a contract to the AHRQ. One author was paid by the USPSTF to conduct the review; two authors reported receiving AHRQ grants during this study (one author) or outside of the study (one author); the rest had no disclosures.

The use of low-dose aspirin during pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk of preeclampsia in women at high risk, and did not appear to be associated with harmful effects, in a systematic review of 23 studies of low-dose aspirin in women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, the authors reported.

In women at high risk for preeclampsia, "available evidence indicates modest effects but important benefits of daily low-dose aspirin for prevention of the condition and consequent illness," concluded Jillian Henderson, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Ore., and her associates.

However, the review had limitations and could not rule out rare or long-term risks of treatment, they said. In addition, more studies are needed, including more in black women, who are disproportionately affected by preeclampsia in the United States.

The study of the effects of low-dose aspirin on the risk of preeclampsia and other maternal and fetal outcomes is being published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (www.annals.org).

The review, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), was conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The USPSTF will post a draft recommendation, based on this review, as an update to the USPSTF 1996 recommendation (which is not active).

The authors reviewed 23 studies of low-dose aspirin in women at high or average risk of preeclampsia with a mean age of 20-31 years; these included randomized controlled studies and observational studies. Treatment was not started before 12 weeks in any of the studies, but was started before 16 weeks in 8 studies. With the exception of six studies, treatment was continued until delivery. In most of the studies, daily aspirin doses ranged from 60 to 100 mg.

The use of aspirin was associated with a 24% reduced risk of preeclampsia in the studies of high-risk women. The dosage or timing (started before or after 16 weeks) did not have an effect on risk. The reduced risk was greater in the studies that used doses higher than 75 mg, but this difference was not significant, the authors reported.

The use of aspirin was associated with a 20% reduced risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and a 14% reduced risk of preterm birth, they reported, adding that the addition of negative studies could make these associations nonsignificant.

In the discussion, the authors said that their confidence in the magnitude of these results was "tempered by evidence of small-study effects and modest findings" in the two largest studies. Therefore, a more conservative estimate for the reduced risk of these outcomes – preeclampsia, IUGR, and preterm birth – was "closer to 10%," they wrote.

They did not identify any harmful effects of aspirin to the baby or mother, but "potential rare or long-term harms could not be ruled out," they concluded. There was some evidence of a possible increased risk in placental abruption, but the associations were not statistically significant. There was no evidence that perinatal mortality was increased, and the data suggested there was "possibly a benefit" on mortality favoring low-dose aspirin.

Their analyses also did not find evidence that low-dose aspirin increased the risk of postpartum hemorrhage or increased mean blood loss or the risk of intracranial hemorrhage in newborns.

The long-term follow-up data on infants (up to age 18 months) available in one study did not show differences in hospital visits, gross motor development, or height and weight between infants exposed to aspirin and those not exposed to aspirin.

Among the limitations of the study was the fact that only studies considered "fair to good quality" were included, and that the smaller studies did not capture any rare events such as perinatal death or placental abruption.

The review was conducted by the Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center, under a contract to the AHRQ. One author was paid by the USPSTF to conduct the review; two authors reported receiving AHRQ grants during this study (one author) or outside of the study (one author); the rest had no disclosures.

The use of low-dose aspirin during pregnancy was associated with a reduced risk of preeclampsia in women at high risk, and did not appear to be associated with harmful effects, in a systematic review of 23 studies of low-dose aspirin in women at high or average risk of preeclampsia, the authors reported.

In women at high risk for preeclampsia, "available evidence indicates modest effects but important benefits of daily low-dose aspirin for prevention of the condition and consequent illness," concluded Jillian Henderson, Ph.D., of Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Ore., and her associates.

However, the review had limitations and could not rule out rare or long-term risks of treatment, they said. In addition, more studies are needed, including more in black women, who are disproportionately affected by preeclampsia in the United States.

The study of the effects of low-dose aspirin on the risk of preeclampsia and other maternal and fetal outcomes is being published online April 8 in Annals of Internal Medicine (www.annals.org).

The review, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), was conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The USPSTF will post a draft recommendation, based on this review, as an update to the USPSTF 1996 recommendation (which is not active).

The authors reviewed 23 studies of low-dose aspirin in women at high or average risk of preeclampsia with a mean age of 20-31 years; these included randomized controlled studies and observational studies. Treatment was not started before 12 weeks in any of the studies, but was started before 16 weeks in 8 studies. With the exception of six studies, treatment was continued until delivery. In most of the studies, daily aspirin doses ranged from 60 to 100 mg.

The use of aspirin was associated with a 24% reduced risk of preeclampsia in the studies of high-risk women. The dosage or timing (started before or after 16 weeks) did not have an effect on risk. The reduced risk was greater in the studies that used doses higher than 75 mg, but this difference was not significant, the authors reported.

The use of aspirin was associated with a 20% reduced risk of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and a 14% reduced risk of preterm birth, they reported, adding that the addition of negative studies could make these associations nonsignificant.

In the discussion, the authors said that their confidence in the magnitude of these results was "tempered by evidence of small-study effects and modest findings" in the two largest studies. Therefore, a more conservative estimate for the reduced risk of these outcomes – preeclampsia, IUGR, and preterm birth – was "closer to 10%," they wrote.

They did not identify any harmful effects of aspirin to the baby or mother, but "potential rare or long-term harms could not be ruled out," they concluded. There was some evidence of a possible increased risk in placental abruption, but the associations were not statistically significant. There was no evidence that perinatal mortality was increased, and the data suggested there was "possibly a benefit" on mortality favoring low-dose aspirin.

Their analyses also did not find evidence that low-dose aspirin increased the risk of postpartum hemorrhage or increased mean blood loss or the risk of intracranial hemorrhage in newborns.

The long-term follow-up data on infants (up to age 18 months) available in one study did not show differences in hospital visits, gross motor development, or height and weight between infants exposed to aspirin and those not exposed to aspirin.

Among the limitations of the study was the fact that only studies considered "fair to good quality" were included, and that the smaller studies did not capture any rare events such as perinatal death or placental abruption.

The review was conducted by the Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center, under a contract to the AHRQ. One author was paid by the USPSTF to conduct the review; two authors reported receiving AHRQ grants during this study (one author) or outside of the study (one author); the rest had no disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Major finding: Prenatal use of low-dose aspirin was associated with a 24% reduced risk of preeclampsia in women at high risk.

Data source: A systematic review of 23 randomized controlled studies and cohort studies that evaluated the risks and benefits of prenatal aspirin among women at high risk of preeclampsia.

Disclosures: The review was conducted by the Kaiser Permanente Research Affiliates Evidence-based Practice Center, under a contract to AHRQ. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), under a contract that supported the work of the USPSTF. One author was paid by the USPSTF to conduct the review; two authors reported receiving AHRQ grants during this study (one author) or outside of the study (one author); the rest had no disclosures.

Drop in circumcision rates prompts call for Medicaid coverage