User login

Platelet-rich plasma injections show no benefit in knee OA in placebo-controlled trial

A large randomized, placebo-controlled trial of platelet-rich plasma injections for knee osteoarthritis has found almost no symptomatic or structural benefit from the treatment, giving some clarity to an evidence base that has seen both positive and negative trials for the treatment modality.

Given the need for better disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis, there has been a lot of interest in biological therapies such as platelet-rich plasma and stem cells, the lead author of the study, Kim Bennell, PhD, told this news organization. “People have started to use it to treat osteoarthritis, but the evidence to support it was limited in terms of its quality, and there’s been very little work looking at effects on structure,” said Dr. Bennell, a research physiotherapist and chair of physiotherapy at the University of Melbourne.

Platelet-rich plasma contains a range of growth factors and cytokines that are thought to be beneficial in building cartilage and reducing inflammation. There have been several clinical trials of the treatment in knee osteoarthritis, but the current study’s authors said these were limited by factors such as a lack of blinding and were at high risk of bias. “That was the impetus to do a large, high-quality study and to look at joint structure,” Dr. Bennell said.

Study details

For the study, which was published Nov. 23 in JAMA, the researchers enrolled 288 adults older than 50 with knee osteoarthritis who had experienced knee pain on most days of the past month and had radiographic evidence of mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the tibiofemoral joint.

After having stopped all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and pain-relief drugs 2 weeks prior – except acetaminophen – participants were randomly assigned to receive three weekly intra-articular knee injections of either a commercially available leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma or saline placebo. They were then followed for 12 months.

Among the 288 participants in the study, researchers saw no statistically significant difference in the change in pain scores between the treatment and placebo groups at 12 months, although there was a nonsignificantly greater reduction in pain scores among those given platelet-rich plasma. The study also found no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the change in medial tibial cartilage volume.

The researchers also looked at a large number of secondary outcomes, including the effects of treatment on pain and function at 2 months, change in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome (KOOS) scores, and change in quality of life scores. There were no indications of any benefits from the treatment at the 2-month follow-up, and at 12 months, the study showed no significant improvements in knee pain while walking or in pain scores, KOOS scores, or quality of life measures.

However, significantly more participants in the treatment group than in the placebo group reported overall improvement at the 2-month point – 48.2% of those in the treatment arm, compared with 36.2% of the placebo group (risk ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.80; P = .02). At 12 months, 42.8% of those who received platelet-rich plasma reported improved function, compared with 32.1% of those in the placebo group (risk ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.00-1.86, P = .05).

The study also found that significantly more people in the platelet-rich plasma group had three or more areas of cartilage thinning at 12 months (17.1% vs. 6.8%; risk ratio, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.16-6.34; P = .02).

Even when researchers looked for treatment effects in subgroups – for example, based on disease severity, body mass index, or knee alignment – they found no significant differences from placebo.

Dr. Bennell said the results were disappointing but not surprising. “Anecdotally, people do report that they get better, but we know that there is a very large placebo effect with treatment of pain,” she said.

Results emphasize importance of placebo controls

In an accompanying editorial by Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, director of the Orthopaedic and Arthritis Center for Outcomes Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, and professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, all in Boston, draws parallels between this study and two earlier studies of platelet-rich plasma for ankle osteoarthritis and Achilles tendinopathy, both published in JAMA in 2021. None of the three studies showed any significant improvements over and above placebo.

“These findings emphasize the importance of comparing interventions with placebos in trials of injection therapies,” Dr. Katz writes. However, he notes that these studies do suggest possible benefits in secondary outcomes, such as self-reported pain and function, and that earlier studies of the treatment had had more positive outcomes.

Dr. Katz said it was premature to dismiss platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis, but “until a new generation of trials using standardized approaches to PRP [platelet-rich plasma] therapy provides evidence of efficacy, it would be prudent to pause the use of PRP for OA and Achilles tendinitis.”

Not ready to stop using platelet-rich plasma?

When asked for comment, sports medicine physician Maarten Moen, MD, from the Bergman Clinics Naarden (the Netherlands) said the study was the largest yet of the use of platelet-rich plasma for knee osteoarthritis and that it was a well-designed, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

However, he also pointed out that at least six earlier randomized, placebo-controlled studies of this treatment approach have been conducted, and of those six, all but two found positive benefits for patients. “It’s a very well-performed study, but for me, it would be a bridge too far to say, ‘Now we have this study, let’s stop doing it,’ ” Dr. Moen said.

Dr. Moen said he would like to see what effect this study had on meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the treatment, as that would give the clearest indication of the overall picture of its effectiveness.

Dr. Moen’s own experience of treating patients with platelet-rich plasma also suggested that, among those who do benefit from the treatment, that benefit would most likely show between 2 and 12 months afterward. He said it would have been useful to see outcomes at 3- and 6-month intervals.

“What I tell people is that, on average, around 9 months’ effect is to be expected,” he said.

Dr. Bennell said the research group chose the 12-month follow-up because they wanted to see if there were long-term improvements in joint structure which they hoped for, given the cost of treatment.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Regen Lab SA provided platelet-rich plasma kits free of charge. Two authors reported using platelet-rich plasma injections in clinical practice, one reported scientific advisory board fees from Biobone, Novartis, Tissuegene, Pfizer, and Lilly; two reported fees for contributing to UpToDate clinical guidelines, and two reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large randomized, placebo-controlled trial of platelet-rich plasma injections for knee osteoarthritis has found almost no symptomatic or structural benefit from the treatment, giving some clarity to an evidence base that has seen both positive and negative trials for the treatment modality.

Given the need for better disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis, there has been a lot of interest in biological therapies such as platelet-rich plasma and stem cells, the lead author of the study, Kim Bennell, PhD, told this news organization. “People have started to use it to treat osteoarthritis, but the evidence to support it was limited in terms of its quality, and there’s been very little work looking at effects on structure,” said Dr. Bennell, a research physiotherapist and chair of physiotherapy at the University of Melbourne.

Platelet-rich plasma contains a range of growth factors and cytokines that are thought to be beneficial in building cartilage and reducing inflammation. There have been several clinical trials of the treatment in knee osteoarthritis, but the current study’s authors said these were limited by factors such as a lack of blinding and were at high risk of bias. “That was the impetus to do a large, high-quality study and to look at joint structure,” Dr. Bennell said.

Study details

For the study, which was published Nov. 23 in JAMA, the researchers enrolled 288 adults older than 50 with knee osteoarthritis who had experienced knee pain on most days of the past month and had radiographic evidence of mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the tibiofemoral joint.

After having stopped all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and pain-relief drugs 2 weeks prior – except acetaminophen – participants were randomly assigned to receive three weekly intra-articular knee injections of either a commercially available leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma or saline placebo. They were then followed for 12 months.

Among the 288 participants in the study, researchers saw no statistically significant difference in the change in pain scores between the treatment and placebo groups at 12 months, although there was a nonsignificantly greater reduction in pain scores among those given platelet-rich plasma. The study also found no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the change in medial tibial cartilage volume.

The researchers also looked at a large number of secondary outcomes, including the effects of treatment on pain and function at 2 months, change in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome (KOOS) scores, and change in quality of life scores. There were no indications of any benefits from the treatment at the 2-month follow-up, and at 12 months, the study showed no significant improvements in knee pain while walking or in pain scores, KOOS scores, or quality of life measures.

However, significantly more participants in the treatment group than in the placebo group reported overall improvement at the 2-month point – 48.2% of those in the treatment arm, compared with 36.2% of the placebo group (risk ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.80; P = .02). At 12 months, 42.8% of those who received platelet-rich plasma reported improved function, compared with 32.1% of those in the placebo group (risk ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.00-1.86, P = .05).

The study also found that significantly more people in the platelet-rich plasma group had three or more areas of cartilage thinning at 12 months (17.1% vs. 6.8%; risk ratio, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.16-6.34; P = .02).

Even when researchers looked for treatment effects in subgroups – for example, based on disease severity, body mass index, or knee alignment – they found no significant differences from placebo.

Dr. Bennell said the results were disappointing but not surprising. “Anecdotally, people do report that they get better, but we know that there is a very large placebo effect with treatment of pain,” she said.

Results emphasize importance of placebo controls

In an accompanying editorial by Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, director of the Orthopaedic and Arthritis Center for Outcomes Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, and professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, all in Boston, draws parallels between this study and two earlier studies of platelet-rich plasma for ankle osteoarthritis and Achilles tendinopathy, both published in JAMA in 2021. None of the three studies showed any significant improvements over and above placebo.

“These findings emphasize the importance of comparing interventions with placebos in trials of injection therapies,” Dr. Katz writes. However, he notes that these studies do suggest possible benefits in secondary outcomes, such as self-reported pain and function, and that earlier studies of the treatment had had more positive outcomes.

Dr. Katz said it was premature to dismiss platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis, but “until a new generation of trials using standardized approaches to PRP [platelet-rich plasma] therapy provides evidence of efficacy, it would be prudent to pause the use of PRP for OA and Achilles tendinitis.”

Not ready to stop using platelet-rich plasma?

When asked for comment, sports medicine physician Maarten Moen, MD, from the Bergman Clinics Naarden (the Netherlands) said the study was the largest yet of the use of platelet-rich plasma for knee osteoarthritis and that it was a well-designed, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

However, he also pointed out that at least six earlier randomized, placebo-controlled studies of this treatment approach have been conducted, and of those six, all but two found positive benefits for patients. “It’s a very well-performed study, but for me, it would be a bridge too far to say, ‘Now we have this study, let’s stop doing it,’ ” Dr. Moen said.

Dr. Moen said he would like to see what effect this study had on meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the treatment, as that would give the clearest indication of the overall picture of its effectiveness.

Dr. Moen’s own experience of treating patients with platelet-rich plasma also suggested that, among those who do benefit from the treatment, that benefit would most likely show between 2 and 12 months afterward. He said it would have been useful to see outcomes at 3- and 6-month intervals.

“What I tell people is that, on average, around 9 months’ effect is to be expected,” he said.

Dr. Bennell said the research group chose the 12-month follow-up because they wanted to see if there were long-term improvements in joint structure which they hoped for, given the cost of treatment.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Regen Lab SA provided platelet-rich plasma kits free of charge. Two authors reported using platelet-rich plasma injections in clinical practice, one reported scientific advisory board fees from Biobone, Novartis, Tissuegene, Pfizer, and Lilly; two reported fees for contributing to UpToDate clinical guidelines, and two reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A large randomized, placebo-controlled trial of platelet-rich plasma injections for knee osteoarthritis has found almost no symptomatic or structural benefit from the treatment, giving some clarity to an evidence base that has seen both positive and negative trials for the treatment modality.

Given the need for better disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis, there has been a lot of interest in biological therapies such as platelet-rich plasma and stem cells, the lead author of the study, Kim Bennell, PhD, told this news organization. “People have started to use it to treat osteoarthritis, but the evidence to support it was limited in terms of its quality, and there’s been very little work looking at effects on structure,” said Dr. Bennell, a research physiotherapist and chair of physiotherapy at the University of Melbourne.

Platelet-rich plasma contains a range of growth factors and cytokines that are thought to be beneficial in building cartilage and reducing inflammation. There have been several clinical trials of the treatment in knee osteoarthritis, but the current study’s authors said these were limited by factors such as a lack of blinding and were at high risk of bias. “That was the impetus to do a large, high-quality study and to look at joint structure,” Dr. Bennell said.

Study details

For the study, which was published Nov. 23 in JAMA, the researchers enrolled 288 adults older than 50 with knee osteoarthritis who had experienced knee pain on most days of the past month and had radiographic evidence of mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the tibiofemoral joint.

After having stopped all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and pain-relief drugs 2 weeks prior – except acetaminophen – participants were randomly assigned to receive three weekly intra-articular knee injections of either a commercially available leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma or saline placebo. They were then followed for 12 months.

Among the 288 participants in the study, researchers saw no statistically significant difference in the change in pain scores between the treatment and placebo groups at 12 months, although there was a nonsignificantly greater reduction in pain scores among those given platelet-rich plasma. The study also found no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the change in medial tibial cartilage volume.

The researchers also looked at a large number of secondary outcomes, including the effects of treatment on pain and function at 2 months, change in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome (KOOS) scores, and change in quality of life scores. There were no indications of any benefits from the treatment at the 2-month follow-up, and at 12 months, the study showed no significant improvements in knee pain while walking or in pain scores, KOOS scores, or quality of life measures.

However, significantly more participants in the treatment group than in the placebo group reported overall improvement at the 2-month point – 48.2% of those in the treatment arm, compared with 36.2% of the placebo group (risk ratio, 1.37; 95% confidence interval, 1.05-1.80; P = .02). At 12 months, 42.8% of those who received platelet-rich plasma reported improved function, compared with 32.1% of those in the placebo group (risk ratio, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.00-1.86, P = .05).

The study also found that significantly more people in the platelet-rich plasma group had three or more areas of cartilage thinning at 12 months (17.1% vs. 6.8%; risk ratio, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.16-6.34; P = .02).

Even when researchers looked for treatment effects in subgroups – for example, based on disease severity, body mass index, or knee alignment – they found no significant differences from placebo.

Dr. Bennell said the results were disappointing but not surprising. “Anecdotally, people do report that they get better, but we know that there is a very large placebo effect with treatment of pain,” she said.

Results emphasize importance of placebo controls

In an accompanying editorial by Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, director of the Orthopaedic and Arthritis Center for Outcomes Research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Harvard Medical School, and professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, all in Boston, draws parallels between this study and two earlier studies of platelet-rich plasma for ankle osteoarthritis and Achilles tendinopathy, both published in JAMA in 2021. None of the three studies showed any significant improvements over and above placebo.

“These findings emphasize the importance of comparing interventions with placebos in trials of injection therapies,” Dr. Katz writes. However, he notes that these studies do suggest possible benefits in secondary outcomes, such as self-reported pain and function, and that earlier studies of the treatment had had more positive outcomes.

Dr. Katz said it was premature to dismiss platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis, but “until a new generation of trials using standardized approaches to PRP [platelet-rich plasma] therapy provides evidence of efficacy, it would be prudent to pause the use of PRP for OA and Achilles tendinitis.”

Not ready to stop using platelet-rich plasma?

When asked for comment, sports medicine physician Maarten Moen, MD, from the Bergman Clinics Naarden (the Netherlands) said the study was the largest yet of the use of platelet-rich plasma for knee osteoarthritis and that it was a well-designed, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

However, he also pointed out that at least six earlier randomized, placebo-controlled studies of this treatment approach have been conducted, and of those six, all but two found positive benefits for patients. “It’s a very well-performed study, but for me, it would be a bridge too far to say, ‘Now we have this study, let’s stop doing it,’ ” Dr. Moen said.

Dr. Moen said he would like to see what effect this study had on meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the treatment, as that would give the clearest indication of the overall picture of its effectiveness.

Dr. Moen’s own experience of treating patients with platelet-rich plasma also suggested that, among those who do benefit from the treatment, that benefit would most likely show between 2 and 12 months afterward. He said it would have been useful to see outcomes at 3- and 6-month intervals.

“What I tell people is that, on average, around 9 months’ effect is to be expected,” he said.

Dr. Bennell said the research group chose the 12-month follow-up because they wanted to see if there were long-term improvements in joint structure which they hoped for, given the cost of treatment.

The study was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, and Regen Lab SA provided platelet-rich plasma kits free of charge. Two authors reported using platelet-rich plasma injections in clinical practice, one reported scientific advisory board fees from Biobone, Novartis, Tissuegene, Pfizer, and Lilly; two reported fees for contributing to UpToDate clinical guidelines, and two reported grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

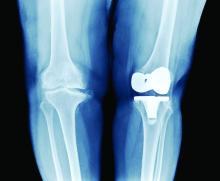

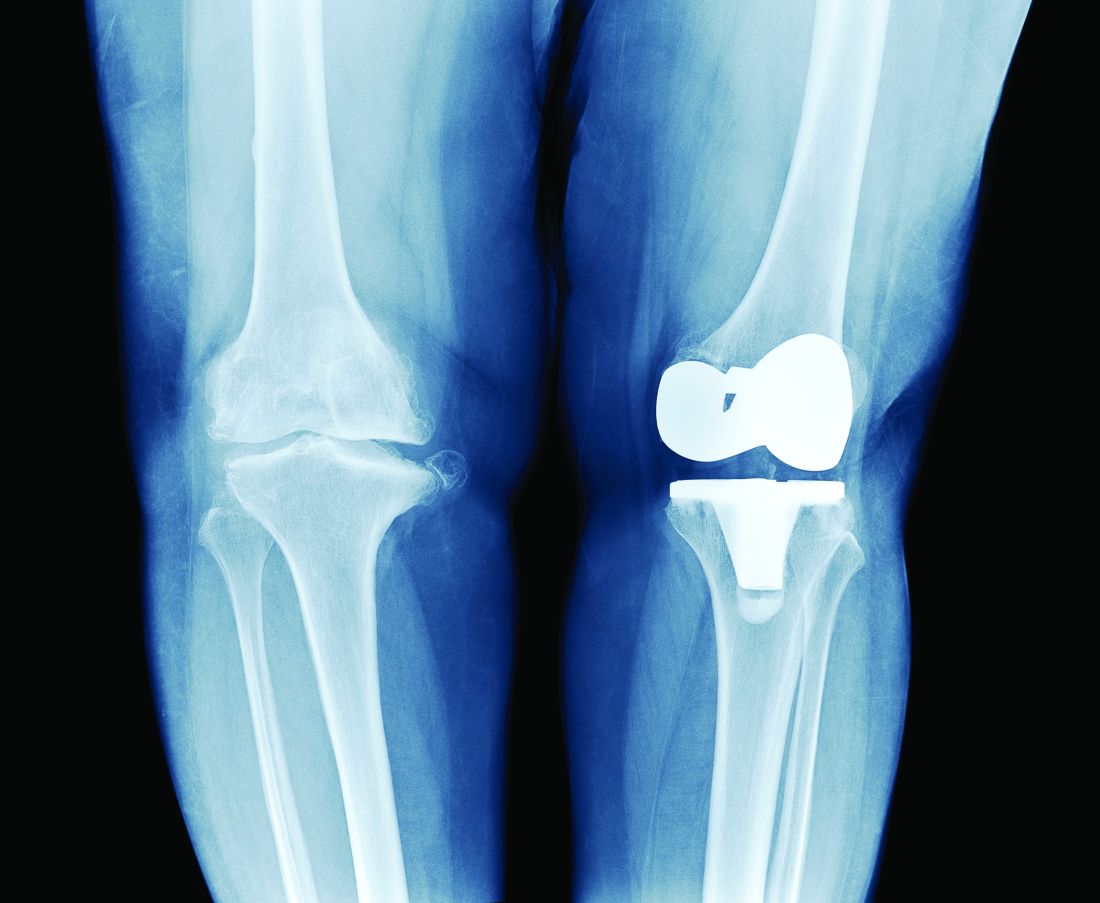

PT may lower risk of long-term opioid use after knee replacement

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PRP injections don’t top placebo for ankle osteoarthritis

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections did not significantly improve pain or function when compared with placebo injections in patients with ankle osteoarthritis (OA), a new study has found.

“Previous evidence for PRP injections in ankle osteoarthritis was limited to 4 small case series with methodological flaws,” wrote Liam D. A. Paget, MD, of the University of Amsterdam, and coauthors. The study was published online Oct. 26 in JAMA.

To assess the value of PRP injections as a treatment for ankle OA, the researchers launched a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of Dutch patients with notable ankle pain and tibiotalar joint space narrowing. From six sites in the Netherlands, 100 patients (45% women, mean age 56 years) were split into two groups: one that received two intra-articular injections of PRP 6 weeks apart (n = 48) and one that received two injections of saline placebo (n = 52).

At baseline, mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) scores were 63 in the PRP group and 64 in the placebo group (range 0-100, with higher scores indicating less pain and more function). At 26-week follow-up, the mean AOFAS score improved by 10 points in the PRP group (95% confidence interval, 6-14; P < .001) and by 11 points in the placebo group (95% CI, 7-15; P < .001). The adjusted between-group difference for AOFAS improvement over 26 weeks was –1 point (95% CI, –6 to 3; P = .56).

There was one serious adverse event in the placebo group – a transient ischemic attack 3 weeks after the first injection – but it was deemed unrelated.

Searching for answers regarding PRP and osteoarthritis

“From my standpoint, this study is a great step forward to where the field needs to be, which is honing in on longer-term studies that are standardizing PRP and teasing out its effects,” Prathap Jayaram, MD, director of regenerative sports medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said in an interview.

He highlighted the authors’ acknowledgment of previous studies in which PRP injections appeared effective in treating knee OA, including their statement that the “results reported here for ankle osteoarthritis were not consistent with these potentially beneficial effects in knee osteoarthritis.”

“They’re acknowledging that this does have some benefit in knees,” he said. “Could that translate toward the ankle?”

“PRP did lead to an improvement,” he added. “There just wasn’t a big enough difference to say one was superior to the other.”

Citing his team’s recent preclinical study that was published in Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Dr. Jayaram emphasized the possibility that PRP could have much-needed disease-modifying effects in osteoarthritis. More work is needed to pin down the details.

“We need more mechanistic studies to be done so we can actually identify the therapeutic properties in PRP and leverage them to track reproducible outcomes,” he said, adding that “simply put, your blood and my blood might be different. There is going to be heterogeneity there. The analogy I give my patients is, when they take an antibiotic, we have a specific dose, a specific drug, and a specific duration. It’s very standardized. We’re just not there yet with PRP.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a likely inability to generalize their results to other platelet-rich blood products as well as a lack of composition analysis of the PRP they used. That said, they added that this particular PRP has been “analyzed previously” for another trial and noted that such analysis is not typically performed in a clinical setting.

The study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Arthritis Society. Its authors reported several potential conflicts of interest, including receiving their own grants from the Dutch Arthritis Society and other organizations, as well as accepting loaned Hettich centrifuges from a medical device company for the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections did not significantly improve pain or function when compared with placebo injections in patients with ankle osteoarthritis (OA), a new study has found.

“Previous evidence for PRP injections in ankle osteoarthritis was limited to 4 small case series with methodological flaws,” wrote Liam D. A. Paget, MD, of the University of Amsterdam, and coauthors. The study was published online Oct. 26 in JAMA.

To assess the value of PRP injections as a treatment for ankle OA, the researchers launched a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of Dutch patients with notable ankle pain and tibiotalar joint space narrowing. From six sites in the Netherlands, 100 patients (45% women, mean age 56 years) were split into two groups: one that received two intra-articular injections of PRP 6 weeks apart (n = 48) and one that received two injections of saline placebo (n = 52).

At baseline, mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) scores were 63 in the PRP group and 64 in the placebo group (range 0-100, with higher scores indicating less pain and more function). At 26-week follow-up, the mean AOFAS score improved by 10 points in the PRP group (95% confidence interval, 6-14; P < .001) and by 11 points in the placebo group (95% CI, 7-15; P < .001). The adjusted between-group difference for AOFAS improvement over 26 weeks was –1 point (95% CI, –6 to 3; P = .56).

There was one serious adverse event in the placebo group – a transient ischemic attack 3 weeks after the first injection – but it was deemed unrelated.

Searching for answers regarding PRP and osteoarthritis

“From my standpoint, this study is a great step forward to where the field needs to be, which is honing in on longer-term studies that are standardizing PRP and teasing out its effects,” Prathap Jayaram, MD, director of regenerative sports medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said in an interview.

He highlighted the authors’ acknowledgment of previous studies in which PRP injections appeared effective in treating knee OA, including their statement that the “results reported here for ankle osteoarthritis were not consistent with these potentially beneficial effects in knee osteoarthritis.”

“They’re acknowledging that this does have some benefit in knees,” he said. “Could that translate toward the ankle?”

“PRP did lead to an improvement,” he added. “There just wasn’t a big enough difference to say one was superior to the other.”

Citing his team’s recent preclinical study that was published in Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Dr. Jayaram emphasized the possibility that PRP could have much-needed disease-modifying effects in osteoarthritis. More work is needed to pin down the details.

“We need more mechanistic studies to be done so we can actually identify the therapeutic properties in PRP and leverage them to track reproducible outcomes,” he said, adding that “simply put, your blood and my blood might be different. There is going to be heterogeneity there. The analogy I give my patients is, when they take an antibiotic, we have a specific dose, a specific drug, and a specific duration. It’s very standardized. We’re just not there yet with PRP.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a likely inability to generalize their results to other platelet-rich blood products as well as a lack of composition analysis of the PRP they used. That said, they added that this particular PRP has been “analyzed previously” for another trial and noted that such analysis is not typically performed in a clinical setting.

The study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Arthritis Society. Its authors reported several potential conflicts of interest, including receiving their own grants from the Dutch Arthritis Society and other organizations, as well as accepting loaned Hettich centrifuges from a medical device company for the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections did not significantly improve pain or function when compared with placebo injections in patients with ankle osteoarthritis (OA), a new study has found.

“Previous evidence for PRP injections in ankle osteoarthritis was limited to 4 small case series with methodological flaws,” wrote Liam D. A. Paget, MD, of the University of Amsterdam, and coauthors. The study was published online Oct. 26 in JAMA.

To assess the value of PRP injections as a treatment for ankle OA, the researchers launched a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of Dutch patients with notable ankle pain and tibiotalar joint space narrowing. From six sites in the Netherlands, 100 patients (45% women, mean age 56 years) were split into two groups: one that received two intra-articular injections of PRP 6 weeks apart (n = 48) and one that received two injections of saline placebo (n = 52).

At baseline, mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) scores were 63 in the PRP group and 64 in the placebo group (range 0-100, with higher scores indicating less pain and more function). At 26-week follow-up, the mean AOFAS score improved by 10 points in the PRP group (95% confidence interval, 6-14; P < .001) and by 11 points in the placebo group (95% CI, 7-15; P < .001). The adjusted between-group difference for AOFAS improvement over 26 weeks was –1 point (95% CI, –6 to 3; P = .56).

There was one serious adverse event in the placebo group – a transient ischemic attack 3 weeks after the first injection – but it was deemed unrelated.

Searching for answers regarding PRP and osteoarthritis

“From my standpoint, this study is a great step forward to where the field needs to be, which is honing in on longer-term studies that are standardizing PRP and teasing out its effects,” Prathap Jayaram, MD, director of regenerative sports medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said in an interview.

He highlighted the authors’ acknowledgment of previous studies in which PRP injections appeared effective in treating knee OA, including their statement that the “results reported here for ankle osteoarthritis were not consistent with these potentially beneficial effects in knee osteoarthritis.”

“They’re acknowledging that this does have some benefit in knees,” he said. “Could that translate toward the ankle?”

“PRP did lead to an improvement,” he added. “There just wasn’t a big enough difference to say one was superior to the other.”

Citing his team’s recent preclinical study that was published in Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, Dr. Jayaram emphasized the possibility that PRP could have much-needed disease-modifying effects in osteoarthritis. More work is needed to pin down the details.

“We need more mechanistic studies to be done so we can actually identify the therapeutic properties in PRP and leverage them to track reproducible outcomes,” he said, adding that “simply put, your blood and my blood might be different. There is going to be heterogeneity there. The analogy I give my patients is, when they take an antibiotic, we have a specific dose, a specific drug, and a specific duration. It’s very standardized. We’re just not there yet with PRP.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a likely inability to generalize their results to other platelet-rich blood products as well as a lack of composition analysis of the PRP they used. That said, they added that this particular PRP has been “analyzed previously” for another trial and noted that such analysis is not typically performed in a clinical setting.

The study was supported by a grant from the Dutch Arthritis Society. Its authors reported several potential conflicts of interest, including receiving their own grants from the Dutch Arthritis Society and other organizations, as well as accepting loaned Hettich centrifuges from a medical device company for the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MDs doing wrong-site surgery: Why is it still happening?

In July 2021, University Hospitals, in Cleveland, announced that its staff had transplanted a kidney into the wrong patient. Although the patient who received the kidney was recovering well, the patient who was supposed to have received the kidney was skipped over. As a result of the error, two employees were placed on administrative leave and the incident was being investigated, the hospital announced.

In April 2020, an interventional radiologist at Boca Raton Regional Hospital, in Boca Raton, Fla., was sued for allegedly placing a stent into the wrong kidney of an 80-year-old patient. Using fluoroscopic guidance, the doctor removed an old stent from the right side but incorrectly replaced it with a new stent on the left side, according to an interview conducted by this news organization with the patient’s lawyers at Searcy Law, in West Palm Beach.

“The problem is that it is so rare that doctors don’t focus on it,” says Mary R. Kwaan, MD, a colorectal surgeon at UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

A 2006 study in which Kwaan was the lead author concluded that there was one wrong-site surgery for every 112,994 surgeries. Those mistakes can add up. A 2006 study estimated that 25 to 52 wrong-site surgeries were performed each week in the United States.

“Many surgeons don’t think it can happen to them, so they don’t take extra precautions,” says David Mayer, MD, executive director of the MedStar Institute for Quality and Safety, in Washington, DC. “When they make a wrong-site error, usually the first thing they say is, ‘I never thought this would happen to me,’ ” he says.

Wrong-site surgeries are considered sentinel events -- the worst kinds of medical errors. The Sullivan Group, a patient safety consultancy based in Colorado, reports that in 2013, 2.7% of patients who were involved in wrong-site surgeries died and 41% experienced some type of permanent injury. The mean malpractice payment was $127,000.

Some malpractice payments are much higher. In 2013, a Maryland ob.gyn paid a $1.42 million malpractice award for removing the wrong ovary from a woman in 2009. In 2017, a Pennsylvania urologist paid $870,000 for removing the wrong testicle from a man in 2013.

Wrong-site surgery often involves experienced surgeons

One might think that wrong-site surgeries usually involve younger or less-experienced surgeons, but that’s not the case; two thirds of the surgeons who perform wrong-site surgeries are in their 40s and 50s, compared with fewer than 25% younger than 40.

In a rather chilling statistic, in a 2013 survey, 12.4% of doctors who were involved in sentinel events in general had claims for more than one event.

These errors are more common in certain specialties. In a study reported in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Spine, 25% of orthopedic surgeons reported performing at least one wrong-site surgery during their career.

Within orthopedics, spine surgery is ground zero for wrong-site surgery. “Finding the site in spine surgery can be more difficult than in common left-right orthopedic procedures,” says Joseph A. Bosco III, a New York City orthopedist.

A 2007 study found that 25% of neurosurgeons had performed wrong-site surgeries. In Missouri in 2013, for example, a 53-year-old patient who was scheduled to undergo a left-sided craniotomy bypass allegedly underwent a right-sided craniotomy and was unable to speak after surgery.

Wrong-site surgeries are also performed by general surgeons, urologists, cardiologists, otolaryngologists, and ophthalmologists. A 2021 lawsuit accused a Tampa urologist of removing the patient’s wrong testicle. And a 2019 lawsuit accused a Chicago ophthalmologist of operating on the wrong eye to remove a cyst.

It’s not just the surgeon’s mistake

Mistakes are not only made by the surgeon in the operating room (OR). They can be made by staff when scheduling a surgery, radiologists and pathologists when writing their reports for surgery, and by team members in the OR.

Many people are prone to confusing left and right. A 2020 study found that 14.9% of people had difficulty distinguishing left from right; other studies have shown higher rates. Distractions increase the likelihood of mistakes. In a 2015 study, background noise in a hospital ward made it more difficult for medical students to make left-right judgments.

OR personnel can be confused when patients are turned around. “To operate on the back of someone’s leg, the surgeon may turn the patient from supine to prone, and so left becomes right,” says Samuel C. Seiden, MD, an anesthesiologist in Roseville, Calif., who has studied wrong-site surgery.

Operative site markings that are drawn on the skin can be rubbed off when surgical prep is applied, and markings aren’t usually possible for procedures such as spine surgeries. Surgical draping can make it harder to distinguish the patient’s left and right, and a busy surgeon relying on memory may confuse cases and perform wrong-patient surgery.

A push to eliminate wrong-site surgery

In 2004, the Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals and many surgery centers, decided to do something about wrong-site surgery and related surgical errors. It released a universal protocol, which requires hospitals to take three steps to prevent errors: perform preoperative verification that is based on patient care documents; mark the operative site; and take a time-out just before surgery, during which the team should consider whether a mistake is about to be made.

Two years after the Joint Commission published its protocol, Dr. Seiden led a study to determine what effect it had had. The investigators found that wrong-site cases had decreased by only about one third. Preventing wrong-site surgery “turns out to be more complicated to eradicate than anybody thought,” Mark Chassin, MD, president of the Joint Commission, stated a few years later.

Why did the protocol have only a limited effect? Dr. Seiden says that it has been hard to change doctors’ traditional attitudes against standardization. “Some have had an attitude that checklists are for dummies, but that is changing,” he says.

For instance, some surgical teams were not paying attention during time-outs. “The time-out should be like the invocation of the National Anthem,” an orthopedic surgeon from Iowa wrote. “All other activities should stop.”

Even had surgeons followed the universal protocol, about one third of wrong-site surgeries would not have been identified, according to Dr. Kwaan’s study, which was published in the same year as Dr. Seiden’s. As an example, when the wrong kidney was removed at Methodist Hospital, in St. Louis Park, Minn., the hospital said it was following a protocol set by the Minnesota Hospital Association.

Redoubling efforts

In 2009, the Joint Commission decided to take another tack. It encouraged hospitals to make root-cause analyses not only of wrong-site surgeries but also of near misses, which are much more plentiful. It used the insights gained to change surgical routines and protocols.

The Safe Surgery Project, a collaboration between the Joint Commission’s Center for Transforming Healthcare and eight hospitals and surgery centers, reduced the number of errors and near misses by 46% in the scheduling area, 63% in pre-op, and 51% in the OR area.

From that project, the center developed the Targeted Solutions Tool, which basically uses the same methodology that the project used. The center told this news organization that 79 healthcare organizations have used the tool and have reduced the number of errors and near misses by 56% in scheduling, 24% in pre-op, and 48% in the OR.

For this approach to work, however, surgical teams must report their errors to the hospital, which had not been done before. A 2008 study by the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that surgical staff did not report 86% of adverse events to their hospitals. Reasons given included lack of time, fear of punitive action, and skepticism that reporting would do any good.

Unlike some other adverse events, it’s hard to keep wrong-site surgeries secret from patients, because they can usually see the scars from it, but some surgeons invent ways to cover it up from patients, too, Dr. Mayer says. One wrong-side hernia repair was corrected in mid operation. Afterward, the surgeon told the patient that he had found another hernia on the other side and had fixed that one, too.

Changing the culture

Reformers argue that wrong-site surgeries can be prevented by changing the culture of the hospital or surgery center. “We have to think of wrong-site surgeries as a failure of the system, not of the individual,” says Ron Savrin, MD, a general surgeon in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, who is a surgery subject matter expert for the Sullivan Group. “It should never be only up to one individual to stop an error from occurring.”

Seeing oneself as part of a team can reduce errors. Although other people can introduce errors that make a person look bad, they can also stop the errors that might otherwise have occurred. Punishing individuals for making errors does little good in stopping errors.

“It’s human nature to want to punish somebody for making a mistake, and it’s hard to change that mentality,” Dr. Savrin says. He recalls that when he was a resident, “the morbidity and mortality conferences could be very difficult for anyone who made a mistake, but I think that attitude is changing.”

Studies have found wide variation in the number of wrong-site surgeries among hospitals. A recent Pennsylvania study found an average of one wrong-site surgery or near miss per hospital per year, but about one third of hospitals did not report any.

Wrong-site surgeries are often concentrated in certain hospitals -- even prestigious teaching hospitals are not immune. A decade ago, Rhode Island Hospital had five wrong-site surgeries in 2 years, and Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center had three wrong-spine surgeries within 2 months.

Other ways to reduce errors

Dr. Seiden thinks reform efforts should take a page from his own specialty. Anesthesiology has developed a variety of forcing functions, which are simple changes in technology that can stop errors. An example is the use of a valve that will not deliver a drug unless certain steps are followed.

The StartBox System, a new way to prevent surgical errors, delivers the surgery blade only after all safety information has been provided. Tested by 11 orthopedic surgeons performing 487 procedures, the system identified 17 near misses.

Another approach is to film time-outs so as to enforce compliance with protocols and help with root-cause analyses. NYU-Langone Medical Center, in New York City, not only films the time-out but also grades OR teams on compliance, says Dr. Bosco, who is vice chair of clinical affairs in the department of orthopedic surgery at the hospital.

In addition, more states are requiring hospitals to report adverse events, including wrong-site surgeries. According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, 28 states require the reporting of adverse events. However, only six states identify facilities in public reports; 16 states publish only aggregate data; and five states do not report error data to the public.

The goal is zero errors

Are there fewer wrong-site surgeries now? “My sense is that surgeons, hospitals, and surgery centers are taking wrong-site errors more seriously,” Dr. Savrin says.

Because reported information is spotty and no major studies on incidence have been conducted in recent years, “we don’t have a clear idea,” he says, “but my best guess is that the rate is declining.

“Absolute zero preventable errors has to be our goal,” Dr. Savrin says “We might not get there, but we can’t stop trying.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In July 2021, University Hospitals, in Cleveland, announced that its staff had transplanted a kidney into the wrong patient. Although the patient who received the kidney was recovering well, the patient who was supposed to have received the kidney was skipped over. As a result of the error, two employees were placed on administrative leave and the incident was being investigated, the hospital announced.

In April 2020, an interventional radiologist at Boca Raton Regional Hospital, in Boca Raton, Fla., was sued for allegedly placing a stent into the wrong kidney of an 80-year-old patient. Using fluoroscopic guidance, the doctor removed an old stent from the right side but incorrectly replaced it with a new stent on the left side, according to an interview conducted by this news organization with the patient’s lawyers at Searcy Law, in West Palm Beach.

“The problem is that it is so rare that doctors don’t focus on it,” says Mary R. Kwaan, MD, a colorectal surgeon at UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

A 2006 study in which Kwaan was the lead author concluded that there was one wrong-site surgery for every 112,994 surgeries. Those mistakes can add up. A 2006 study estimated that 25 to 52 wrong-site surgeries were performed each week in the United States.

“Many surgeons don’t think it can happen to them, so they don’t take extra precautions,” says David Mayer, MD, executive director of the MedStar Institute for Quality and Safety, in Washington, DC. “When they make a wrong-site error, usually the first thing they say is, ‘I never thought this would happen to me,’ ” he says.

Wrong-site surgeries are considered sentinel events -- the worst kinds of medical errors. The Sullivan Group, a patient safety consultancy based in Colorado, reports that in 2013, 2.7% of patients who were involved in wrong-site surgeries died and 41% experienced some type of permanent injury. The mean malpractice payment was $127,000.

Some malpractice payments are much higher. In 2013, a Maryland ob.gyn paid a $1.42 million malpractice award for removing the wrong ovary from a woman in 2009. In 2017, a Pennsylvania urologist paid $870,000 for removing the wrong testicle from a man in 2013.

Wrong-site surgery often involves experienced surgeons

One might think that wrong-site surgeries usually involve younger or less-experienced surgeons, but that’s not the case; two thirds of the surgeons who perform wrong-site surgeries are in their 40s and 50s, compared with fewer than 25% younger than 40.

In a rather chilling statistic, in a 2013 survey, 12.4% of doctors who were involved in sentinel events in general had claims for more than one event.

These errors are more common in certain specialties. In a study reported in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Spine, 25% of orthopedic surgeons reported performing at least one wrong-site surgery during their career.

Within orthopedics, spine surgery is ground zero for wrong-site surgery. “Finding the site in spine surgery can be more difficult than in common left-right orthopedic procedures,” says Joseph A. Bosco III, a New York City orthopedist.

A 2007 study found that 25% of neurosurgeons had performed wrong-site surgeries. In Missouri in 2013, for example, a 53-year-old patient who was scheduled to undergo a left-sided craniotomy bypass allegedly underwent a right-sided craniotomy and was unable to speak after surgery.

Wrong-site surgeries are also performed by general surgeons, urologists, cardiologists, otolaryngologists, and ophthalmologists. A 2021 lawsuit accused a Tampa urologist of removing the patient’s wrong testicle. And a 2019 lawsuit accused a Chicago ophthalmologist of operating on the wrong eye to remove a cyst.

It’s not just the surgeon’s mistake

Mistakes are not only made by the surgeon in the operating room (OR). They can be made by staff when scheduling a surgery, radiologists and pathologists when writing their reports for surgery, and by team members in the OR.

Many people are prone to confusing left and right. A 2020 study found that 14.9% of people had difficulty distinguishing left from right; other studies have shown higher rates. Distractions increase the likelihood of mistakes. In a 2015 study, background noise in a hospital ward made it more difficult for medical students to make left-right judgments.

OR personnel can be confused when patients are turned around. “To operate on the back of someone’s leg, the surgeon may turn the patient from supine to prone, and so left becomes right,” says Samuel C. Seiden, MD, an anesthesiologist in Roseville, Calif., who has studied wrong-site surgery.

Operative site markings that are drawn on the skin can be rubbed off when surgical prep is applied, and markings aren’t usually possible for procedures such as spine surgeries. Surgical draping can make it harder to distinguish the patient’s left and right, and a busy surgeon relying on memory may confuse cases and perform wrong-patient surgery.

A push to eliminate wrong-site surgery

In 2004, the Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals and many surgery centers, decided to do something about wrong-site surgery and related surgical errors. It released a universal protocol, which requires hospitals to take three steps to prevent errors: perform preoperative verification that is based on patient care documents; mark the operative site; and take a time-out just before surgery, during which the team should consider whether a mistake is about to be made.

Two years after the Joint Commission published its protocol, Dr. Seiden led a study to determine what effect it had had. The investigators found that wrong-site cases had decreased by only about one third. Preventing wrong-site surgery “turns out to be more complicated to eradicate than anybody thought,” Mark Chassin, MD, president of the Joint Commission, stated a few years later.

Why did the protocol have only a limited effect? Dr. Seiden says that it has been hard to change doctors’ traditional attitudes against standardization. “Some have had an attitude that checklists are for dummies, but that is changing,” he says.

For instance, some surgical teams were not paying attention during time-outs. “The time-out should be like the invocation of the National Anthem,” an orthopedic surgeon from Iowa wrote. “All other activities should stop.”

Even had surgeons followed the universal protocol, about one third of wrong-site surgeries would not have been identified, according to Dr. Kwaan’s study, which was published in the same year as Dr. Seiden’s. As an example, when the wrong kidney was removed at Methodist Hospital, in St. Louis Park, Minn., the hospital said it was following a protocol set by the Minnesota Hospital Association.

Redoubling efforts

In 2009, the Joint Commission decided to take another tack. It encouraged hospitals to make root-cause analyses not only of wrong-site surgeries but also of near misses, which are much more plentiful. It used the insights gained to change surgical routines and protocols.

The Safe Surgery Project, a collaboration between the Joint Commission’s Center for Transforming Healthcare and eight hospitals and surgery centers, reduced the number of errors and near misses by 46% in the scheduling area, 63% in pre-op, and 51% in the OR area.

From that project, the center developed the Targeted Solutions Tool, which basically uses the same methodology that the project used. The center told this news organization that 79 healthcare organizations have used the tool and have reduced the number of errors and near misses by 56% in scheduling, 24% in pre-op, and 48% in the OR.

For this approach to work, however, surgical teams must report their errors to the hospital, which had not been done before. A 2008 study by the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that surgical staff did not report 86% of adverse events to their hospitals. Reasons given included lack of time, fear of punitive action, and skepticism that reporting would do any good.

Unlike some other adverse events, it’s hard to keep wrong-site surgeries secret from patients, because they can usually see the scars from it, but some surgeons invent ways to cover it up from patients, too, Dr. Mayer says. One wrong-side hernia repair was corrected in mid operation. Afterward, the surgeon told the patient that he had found another hernia on the other side and had fixed that one, too.

Changing the culture

Reformers argue that wrong-site surgeries can be prevented by changing the culture of the hospital or surgery center. “We have to think of wrong-site surgeries as a failure of the system, not of the individual,” says Ron Savrin, MD, a general surgeon in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, who is a surgery subject matter expert for the Sullivan Group. “It should never be only up to one individual to stop an error from occurring.”

Seeing oneself as part of a team can reduce errors. Although other people can introduce errors that make a person look bad, they can also stop the errors that might otherwise have occurred. Punishing individuals for making errors does little good in stopping errors.

“It’s human nature to want to punish somebody for making a mistake, and it’s hard to change that mentality,” Dr. Savrin says. He recalls that when he was a resident, “the morbidity and mortality conferences could be very difficult for anyone who made a mistake, but I think that attitude is changing.”

Studies have found wide variation in the number of wrong-site surgeries among hospitals. A recent Pennsylvania study found an average of one wrong-site surgery or near miss per hospital per year, but about one third of hospitals did not report any.

Wrong-site surgeries are often concentrated in certain hospitals -- even prestigious teaching hospitals are not immune. A decade ago, Rhode Island Hospital had five wrong-site surgeries in 2 years, and Boston’s Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center had three wrong-spine surgeries within 2 months.

Other ways to reduce errors

Dr. Seiden thinks reform efforts should take a page from his own specialty. Anesthesiology has developed a variety of forcing functions, which are simple changes in technology that can stop errors. An example is the use of a valve that will not deliver a drug unless certain steps are followed.

The StartBox System, a new way to prevent surgical errors, delivers the surgery blade only after all safety information has been provided. Tested by 11 orthopedic surgeons performing 487 procedures, the system identified 17 near misses.

Another approach is to film time-outs so as to enforce compliance with protocols and help with root-cause analyses. NYU-Langone Medical Center, in New York City, not only films the time-out but also grades OR teams on compliance, says Dr. Bosco, who is vice chair of clinical affairs in the department of orthopedic surgery at the hospital.

In addition, more states are requiring hospitals to report adverse events, including wrong-site surgeries. According to the National Academy for State Health Policy, 28 states require the reporting of adverse events. However, only six states identify facilities in public reports; 16 states publish only aggregate data; and five states do not report error data to the public.

The goal is zero errors

Are there fewer wrong-site surgeries now? “My sense is that surgeons, hospitals, and surgery centers are taking wrong-site errors more seriously,” Dr. Savrin says.

Because reported information is spotty and no major studies on incidence have been conducted in recent years, “we don’t have a clear idea,” he says, “but my best guess is that the rate is declining.

“Absolute zero preventable errors has to be our goal,” Dr. Savrin says “We might not get there, but we can’t stop trying.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In July 2021, University Hospitals, in Cleveland, announced that its staff had transplanted a kidney into the wrong patient. Although the patient who received the kidney was recovering well, the patient who was supposed to have received the kidney was skipped over. As a result of the error, two employees were placed on administrative leave and the incident was being investigated, the hospital announced.

In April 2020, an interventional radiologist at Boca Raton Regional Hospital, in Boca Raton, Fla., was sued for allegedly placing a stent into the wrong kidney of an 80-year-old patient. Using fluoroscopic guidance, the doctor removed an old stent from the right side but incorrectly replaced it with a new stent on the left side, according to an interview conducted by this news organization with the patient’s lawyers at Searcy Law, in West Palm Beach.

“The problem is that it is so rare that doctors don’t focus on it,” says Mary R. Kwaan, MD, a colorectal surgeon at UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

A 2006 study in which Kwaan was the lead author concluded that there was one wrong-site surgery for every 112,994 surgeries. Those mistakes can add up. A 2006 study estimated that 25 to 52 wrong-site surgeries were performed each week in the United States.

“Many surgeons don’t think it can happen to them, so they don’t take extra precautions,” says David Mayer, MD, executive director of the MedStar Institute for Quality and Safety, in Washington, DC. “When they make a wrong-site error, usually the first thing they say is, ‘I never thought this would happen to me,’ ” he says.

Wrong-site surgeries are considered sentinel events -- the worst kinds of medical errors. The Sullivan Group, a patient safety consultancy based in Colorado, reports that in 2013, 2.7% of patients who were involved in wrong-site surgeries died and 41% experienced some type of permanent injury. The mean malpractice payment was $127,000.

Some malpractice payments are much higher. In 2013, a Maryland ob.gyn paid a $1.42 million malpractice award for removing the wrong ovary from a woman in 2009. In 2017, a Pennsylvania urologist paid $870,000 for removing the wrong testicle from a man in 2013.

Wrong-site surgery often involves experienced surgeons

One might think that wrong-site surgeries usually involve younger or less-experienced surgeons, but that’s not the case; two thirds of the surgeons who perform wrong-site surgeries are in their 40s and 50s, compared with fewer than 25% younger than 40.

In a rather chilling statistic, in a 2013 survey, 12.4% of doctors who were involved in sentinel events in general had claims for more than one event.

These errors are more common in certain specialties. In a study reported in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Spine, 25% of orthopedic surgeons reported performing at least one wrong-site surgery during their career.

Within orthopedics, spine surgery is ground zero for wrong-site surgery. “Finding the site in spine surgery can be more difficult than in common left-right orthopedic procedures,” says Joseph A. Bosco III, a New York City orthopedist.

A 2007 study found that 25% of neurosurgeons had performed wrong-site surgeries. In Missouri in 2013, for example, a 53-year-old patient who was scheduled to undergo a left-sided craniotomy bypass allegedly underwent a right-sided craniotomy and was unable to speak after surgery.

Wrong-site surgeries are also performed by general surgeons, urologists, cardiologists, otolaryngologists, and ophthalmologists. A 2021 lawsuit accused a Tampa urologist of removing the patient’s wrong testicle. And a 2019 lawsuit accused a Chicago ophthalmologist of operating on the wrong eye to remove a cyst.

It’s not just the surgeon’s mistake

Mistakes are not only made by the surgeon in the operating room (OR). They can be made by staff when scheduling a surgery, radiologists and pathologists when writing their reports for surgery, and by team members in the OR.

Many people are prone to confusing left and right. A 2020 study found that 14.9% of people had difficulty distinguishing left from right; other studies have shown higher rates. Distractions increase the likelihood of mistakes. In a 2015 study, background noise in a hospital ward made it more difficult for medical students to make left-right judgments.

OR personnel can be confused when patients are turned around. “To operate on the back of someone’s leg, the surgeon may turn the patient from supine to prone, and so left becomes right,” says Samuel C. Seiden, MD, an anesthesiologist in Roseville, Calif., who has studied wrong-site surgery.

Operative site markings that are drawn on the skin can be rubbed off when surgical prep is applied, and markings aren’t usually possible for procedures such as spine surgeries. Surgical draping can make it harder to distinguish the patient’s left and right, and a busy surgeon relying on memory may confuse cases and perform wrong-patient surgery.

A push to eliminate wrong-site surgery