User login

Psoriatic Arthritis on the Rise

The primary comorbidity of psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The true incidence of PsA has long been an issue of debate. To estimate the incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis and to identify risk factors for its development, Eder at al conducted a prospective cohort study involving psoriasis patients without arthritis at study entry that was published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The investigators collected information from patients concerning lifestyle habits, comorbidities, psoriasis activity, and medications. The patients were evaluated at enrollment and annually. A general physical examination, assessment of psoriasis severity, and assessment for the development of musculoskeletal symptoms were conducted at each visit. A diagnosis of PsA was determined by a rheumatologist on the basis of clinical, laboratory, and imaging data; patients also had to fulfill the CASPAR (Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis) criteria (confirmed cases). The annual incidence of PsA was estimated using an event per person-years analysis.

The results from 464 patients who were followed for 8 years were analyzed. The annual incidence of confirmed PsA was 2.7 per 100 patients with psoriasis (95% CI, 2.1-3.6). Overall, 51 patients developed PsA over the course of the study and an additional 9 were considered suspect cases.

The following baseline variables were associated with the development of PsA in multivariate analysis: severe psoriasis (relative risk [RR], 5.4; P=.006), low level of education (college/university vs high school incomplete: RR, 4.5; P=.005; high school education vs high school incomplete: RR, 3.3; P=.049), and use of retinoid medications (RR, 3.4; P=.02). In addition, psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P=.002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P<.001) were time-dependent predictors for PsA development.

The authors concluded that the incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis was higher than previously reported. Possible factors for this finding might include differences in patient recruitment as well as self-reported PsA diagnoses.

What’s the issue?

This prospective analysis is interesting. The incidence of PsA was higher than reported. It reinforces the need for continual evaluation of joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis, even if they have had psoriasis for many years. How will this analysis impact your evaluation of psoriatic patients?

The primary comorbidity of psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The true incidence of PsA has long been an issue of debate. To estimate the incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis and to identify risk factors for its development, Eder at al conducted a prospective cohort study involving psoriasis patients without arthritis at study entry that was published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The investigators collected information from patients concerning lifestyle habits, comorbidities, psoriasis activity, and medications. The patients were evaluated at enrollment and annually. A general physical examination, assessment of psoriasis severity, and assessment for the development of musculoskeletal symptoms were conducted at each visit. A diagnosis of PsA was determined by a rheumatologist on the basis of clinical, laboratory, and imaging data; patients also had to fulfill the CASPAR (Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis) criteria (confirmed cases). The annual incidence of PsA was estimated using an event per person-years analysis.

The results from 464 patients who were followed for 8 years were analyzed. The annual incidence of confirmed PsA was 2.7 per 100 patients with psoriasis (95% CI, 2.1-3.6). Overall, 51 patients developed PsA over the course of the study and an additional 9 were considered suspect cases.

The following baseline variables were associated with the development of PsA in multivariate analysis: severe psoriasis (relative risk [RR], 5.4; P=.006), low level of education (college/university vs high school incomplete: RR, 4.5; P=.005; high school education vs high school incomplete: RR, 3.3; P=.049), and use of retinoid medications (RR, 3.4; P=.02). In addition, psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P=.002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P<.001) were time-dependent predictors for PsA development.

The authors concluded that the incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis was higher than previously reported. Possible factors for this finding might include differences in patient recruitment as well as self-reported PsA diagnoses.

What’s the issue?

This prospective analysis is interesting. The incidence of PsA was higher than reported. It reinforces the need for continual evaluation of joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis, even if they have had psoriasis for many years. How will this analysis impact your evaluation of psoriatic patients?

The primary comorbidity of psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis (PsA). The true incidence of PsA has long been an issue of debate. To estimate the incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis and to identify risk factors for its development, Eder at al conducted a prospective cohort study involving psoriasis patients without arthritis at study entry that was published online in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The investigators collected information from patients concerning lifestyle habits, comorbidities, psoriasis activity, and medications. The patients were evaluated at enrollment and annually. A general physical examination, assessment of psoriasis severity, and assessment for the development of musculoskeletal symptoms were conducted at each visit. A diagnosis of PsA was determined by a rheumatologist on the basis of clinical, laboratory, and imaging data; patients also had to fulfill the CASPAR (Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis) criteria (confirmed cases). The annual incidence of PsA was estimated using an event per person-years analysis.

The results from 464 patients who were followed for 8 years were analyzed. The annual incidence of confirmed PsA was 2.7 per 100 patients with psoriasis (95% CI, 2.1-3.6). Overall, 51 patients developed PsA over the course of the study and an additional 9 were considered suspect cases.

The following baseline variables were associated with the development of PsA in multivariate analysis: severe psoriasis (relative risk [RR], 5.4; P=.006), low level of education (college/university vs high school incomplete: RR, 4.5; P=.005; high school education vs high school incomplete: RR, 3.3; P=.049), and use of retinoid medications (RR, 3.4; P=.02). In addition, psoriatic nail pitting (RR, 2.5; P=.002) and uveitis (RR, 31.5; P<.001) were time-dependent predictors for PsA development.

The authors concluded that the incidence of PsA in patients with psoriasis was higher than previously reported. Possible factors for this finding might include differences in patient recruitment as well as self-reported PsA diagnoses.

What’s the issue?

This prospective analysis is interesting. The incidence of PsA was higher than reported. It reinforces the need for continual evaluation of joint symptoms in patients with psoriasis, even if they have had psoriasis for many years. How will this analysis impact your evaluation of psoriatic patients?

Product News: 02 2016

Cosentyx

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of 2 new indications for Cosentyx (secukinumab): to treat patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and active psoriatic arthritis. Cosentyx is a human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to IL-17A and inhibits its interaction with the IL-17 receptor. Research suggests that IL-17A may play an important role in driving the body’s immune response in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Cosentyx was approved in January 2015 for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. For more information, visit www.cosentyx.com.

Emverm

Impax Laboratories, Inc, receives US Food and Drug Administration approval for the supplemental new drug application of Emverm (mebendazole) 100-mg chewable tablets for the treatment of pinworm and certain worm infections. Emverm is indicated for treatment of pinworm, whipworm, common roundworm, common hookworm, and American hookworm in single or mixed infections. Emverm is expected to become available early in the second quarter of 2016. For more information, visit www.impaxlabs.com.

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of an expanded indication for Keytruda (pembrolizumab) that includes the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Keytruda is indicated in the United States at a dose of 2 mg/kg administered as an intravenous infusion over 30 minutes every 3 weeks. Keytruda is an anti–programmed death receptor-1 therapy that works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to help detect and fight tumor cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Opdivo + Yervoy Regimen

The US Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval of nivolumab (Opdivo) in combination with ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of patients with BRAF V600 wild-type unresectable or metastatic melanoma. An international, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled trial in patients who were previously untreated for unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600 wild-type melanoma demonstrated an increase in the objective response rate, prolonged response durations, and improvement in progression-free survival. When used in combination with ipilimumab, the recommended dose and schedule is nivolumab 1 mg/kg administered as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes, followed by ipilimumab on the same day every 3 weeks for 4 doses. The recommended subsequent dose of nivolumab, as a single agent, is 3 mg/kg as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. For more information, visit www.opdivoyervoyhcp.com.

TriAcnéal Day Mattifying Lotion and Night Smoothing Lotion

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces 2 TriAcnéal lotions in the Avène line for the treatment and prevention of acne. TriAcnéal Day Mattifying Lotion provides hydrating and mattifying care. It is gentle enough for daily use and can be used alone or in combination with topical acne prescriptions. A trio of ingredients target acne: PCC enzyme (consisting of papain, sodium alginate, caprylyl glycol, and hexanediol) for exfoliation to counteract the formation of new comedones, Diolényl (consisting of caprylyl glycol linseedate and potassium sorbate)to treat existing blemishes and prevent new lesions, and glyceryl laurate to reduce oil production. TriAcnéal Night Smoothing Lotion works to reduce the appearance of acne scars and provides moisturization and redness-reduction benefits. The nighttime formula contains PCC enzyme and Diolényl as well as retinaldehyde to diminish visible signs of aging. For more information, visit www.aveneusa.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Cosentyx

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of 2 new indications for Cosentyx (secukinumab): to treat patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and active psoriatic arthritis. Cosentyx is a human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to IL-17A and inhibits its interaction with the IL-17 receptor. Research suggests that IL-17A may play an important role in driving the body’s immune response in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Cosentyx was approved in January 2015 for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. For more information, visit www.cosentyx.com.

Emverm

Impax Laboratories, Inc, receives US Food and Drug Administration approval for the supplemental new drug application of Emverm (mebendazole) 100-mg chewable tablets for the treatment of pinworm and certain worm infections. Emverm is indicated for treatment of pinworm, whipworm, common roundworm, common hookworm, and American hookworm in single or mixed infections. Emverm is expected to become available early in the second quarter of 2016. For more information, visit www.impaxlabs.com.

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of an expanded indication for Keytruda (pembrolizumab) that includes the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Keytruda is indicated in the United States at a dose of 2 mg/kg administered as an intravenous infusion over 30 minutes every 3 weeks. Keytruda is an anti–programmed death receptor-1 therapy that works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to help detect and fight tumor cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Opdivo + Yervoy Regimen

The US Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval of nivolumab (Opdivo) in combination with ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of patients with BRAF V600 wild-type unresectable or metastatic melanoma. An international, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled trial in patients who were previously untreated for unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600 wild-type melanoma demonstrated an increase in the objective response rate, prolonged response durations, and improvement in progression-free survival. When used in combination with ipilimumab, the recommended dose and schedule is nivolumab 1 mg/kg administered as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes, followed by ipilimumab on the same day every 3 weeks for 4 doses. The recommended subsequent dose of nivolumab, as a single agent, is 3 mg/kg as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. For more information, visit www.opdivoyervoyhcp.com.

TriAcnéal Day Mattifying Lotion and Night Smoothing Lotion

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces 2 TriAcnéal lotions in the Avène line for the treatment and prevention of acne. TriAcnéal Day Mattifying Lotion provides hydrating and mattifying care. It is gentle enough for daily use and can be used alone or in combination with topical acne prescriptions. A trio of ingredients target acne: PCC enzyme (consisting of papain, sodium alginate, caprylyl glycol, and hexanediol) for exfoliation to counteract the formation of new comedones, Diolényl (consisting of caprylyl glycol linseedate and potassium sorbate)to treat existing blemishes and prevent new lesions, and glyceryl laurate to reduce oil production. TriAcnéal Night Smoothing Lotion works to reduce the appearance of acne scars and provides moisturization and redness-reduction benefits. The nighttime formula contains PCC enzyme and Diolényl as well as retinaldehyde to diminish visible signs of aging. For more information, visit www.aveneusa.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Cosentyx

Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of 2 new indications for Cosentyx (secukinumab): to treat patients with active ankylosing spondylitis and active psoriatic arthritis. Cosentyx is a human monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to IL-17A and inhibits its interaction with the IL-17 receptor. Research suggests that IL-17A may play an important role in driving the body’s immune response in psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. Cosentyx was approved in January 2015 for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. For more information, visit www.cosentyx.com.

Emverm

Impax Laboratories, Inc, receives US Food and Drug Administration approval for the supplemental new drug application of Emverm (mebendazole) 100-mg chewable tablets for the treatment of pinworm and certain worm infections. Emverm is indicated for treatment of pinworm, whipworm, common roundworm, common hookworm, and American hookworm in single or mixed infections. Emverm is expected to become available early in the second quarter of 2016. For more information, visit www.impaxlabs.com.

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of an expanded indication for Keytruda (pembrolizumab) that includes the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Keytruda is indicated in the United States at a dose of 2 mg/kg administered as an intravenous infusion over 30 minutes every 3 weeks. Keytruda is an anti–programmed death receptor-1 therapy that works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to help detect and fight tumor cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Opdivo + Yervoy Regimen

The US Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval of nivolumab (Opdivo) in combination with ipilimumab (Yervoy) for the treatment of patients with BRAF V600 wild-type unresectable or metastatic melanoma. An international, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled trial in patients who were previously untreated for unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600 wild-type melanoma demonstrated an increase in the objective response rate, prolonged response durations, and improvement in progression-free survival. When used in combination with ipilimumab, the recommended dose and schedule is nivolumab 1 mg/kg administered as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes, followed by ipilimumab on the same day every 3 weeks for 4 doses. The recommended subsequent dose of nivolumab, as a single agent, is 3 mg/kg as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. For more information, visit www.opdivoyervoyhcp.com.

TriAcnéal Day Mattifying Lotion and Night Smoothing Lotion

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA introduces 2 TriAcnéal lotions in the Avène line for the treatment and prevention of acne. TriAcnéal Day Mattifying Lotion provides hydrating and mattifying care. It is gentle enough for daily use and can be used alone or in combination with topical acne prescriptions. A trio of ingredients target acne: PCC enzyme (consisting of papain, sodium alginate, caprylyl glycol, and hexanediol) for exfoliation to counteract the formation of new comedones, Diolényl (consisting of caprylyl glycol linseedate and potassium sorbate)to treat existing blemishes and prevent new lesions, and glyceryl laurate to reduce oil production. TriAcnéal Night Smoothing Lotion works to reduce the appearance of acne scars and provides moisturization and redness-reduction benefits. The nighttime formula contains PCC enzyme and Diolényl as well as retinaldehyde to diminish visible signs of aging. For more information, visit www.aveneusa.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at cutis@frontlinemedcom.com.

Consider comorbidities in psoriasis treatment for better outcomes

GRAND CAYMAN – Emerging data increasingly link psoriasis with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression, leading one expert to suggest a more integrated approach to care in patients with these comorbid conditions.

“I think people are starting to understand that the skin is just a marker for inflammation,” Dr. J. Mark Jackson of the University of Louisville (Ky.), said at this year’s annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education, a sister company to this news organization.

Growing evidence suggests cardiovascular disease is more common in patients with severe psoriasis. The overlap between the two disease states is thought to occur through similar patterns of inflammation, which Dr. Jackson said indicates that patient outcomes for both could be better if clinicians take an integrated approach to treatment. “Skin disease is an excellent way to study new therapies for other diseases,” said Dr. Jackson. “We can actually look at the skin, so it’s a lot easier to study it than the kidney, heart, or lung” (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Nov 12;67[3]:357-62).

Screening for CVD, as well as for other comorbidities, such as diabetes and depression – both of which tend to occur at higher rates in persons with psoriasis – could also help improve compliance rates, according to Dr. Jackson (Dermatology. 2012;225[2]:121-6). .

“Especially if patients are heavy, if they smoke, if their lipids are high, if they have high blood pressure, or a history of heart disease, it’s important to remember that all of these things are connected to chronic inflammation. I think if we keep that in mind, we can have a better health outcome overall,” Dr. Jackson said.

A survey of 163 psoriasis patients published in 2012 found that comorbidities significantly affected patients’ preferences for psoriasis treatments: Those with psoriatic arthritis were more focused on the probability of benefit (P = .037), those with CVD worried about the probability of side effects (P = .046), and those with depression were concerned about treatment duration (P = .047), and cost (P = .023) (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Oct 19;67[3]:363-72).

Because psoriasis is also associated with higher prevalence and incidence rates of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, particularly in patients with severe psoriasis, Dr. Jackson recommended screening for these diseases when monitoring patients during their follow-up visits (JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Jan;149[1]:84-91).

“Metabolic syndrome gives you more trouble controlling psoriasis and vice versa,” Dr. Jackson said. “It’s important to tell patients that the better health they are in, the better their medicines will work, and the better response their psoriasis will have.”

Dr. Jackson has financial ties to several pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Amgen, Dermira, Galdera, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

GRAND CAYMAN – Emerging data increasingly link psoriasis with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression, leading one expert to suggest a more integrated approach to care in patients with these comorbid conditions.

“I think people are starting to understand that the skin is just a marker for inflammation,” Dr. J. Mark Jackson of the University of Louisville (Ky.), said at this year’s annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education, a sister company to this news organization.

Growing evidence suggests cardiovascular disease is more common in patients with severe psoriasis. The overlap between the two disease states is thought to occur through similar patterns of inflammation, which Dr. Jackson said indicates that patient outcomes for both could be better if clinicians take an integrated approach to treatment. “Skin disease is an excellent way to study new therapies for other diseases,” said Dr. Jackson. “We can actually look at the skin, so it’s a lot easier to study it than the kidney, heart, or lung” (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Nov 12;67[3]:357-62).

Screening for CVD, as well as for other comorbidities, such as diabetes and depression – both of which tend to occur at higher rates in persons with psoriasis – could also help improve compliance rates, according to Dr. Jackson (Dermatology. 2012;225[2]:121-6). .

“Especially if patients are heavy, if they smoke, if their lipids are high, if they have high blood pressure, or a history of heart disease, it’s important to remember that all of these things are connected to chronic inflammation. I think if we keep that in mind, we can have a better health outcome overall,” Dr. Jackson said.

A survey of 163 psoriasis patients published in 2012 found that comorbidities significantly affected patients’ preferences for psoriasis treatments: Those with psoriatic arthritis were more focused on the probability of benefit (P = .037), those with CVD worried about the probability of side effects (P = .046), and those with depression were concerned about treatment duration (P = .047), and cost (P = .023) (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Oct 19;67[3]:363-72).

Because psoriasis is also associated with higher prevalence and incidence rates of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, particularly in patients with severe psoriasis, Dr. Jackson recommended screening for these diseases when monitoring patients during their follow-up visits (JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Jan;149[1]:84-91).

“Metabolic syndrome gives you more trouble controlling psoriasis and vice versa,” Dr. Jackson said. “It’s important to tell patients that the better health they are in, the better their medicines will work, and the better response their psoriasis will have.”

Dr. Jackson has financial ties to several pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Amgen, Dermira, Galdera, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

GRAND CAYMAN – Emerging data increasingly link psoriasis with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and depression, leading one expert to suggest a more integrated approach to care in patients with these comorbid conditions.

“I think people are starting to understand that the skin is just a marker for inflammation,” Dr. J. Mark Jackson of the University of Louisville (Ky.), said at this year’s annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, provided by Global Academy for Medical Education, a sister company to this news organization.

Growing evidence suggests cardiovascular disease is more common in patients with severe psoriasis. The overlap between the two disease states is thought to occur through similar patterns of inflammation, which Dr. Jackson said indicates that patient outcomes for both could be better if clinicians take an integrated approach to treatment. “Skin disease is an excellent way to study new therapies for other diseases,” said Dr. Jackson. “We can actually look at the skin, so it’s a lot easier to study it than the kidney, heart, or lung” (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Nov 12;67[3]:357-62).

Screening for CVD, as well as for other comorbidities, such as diabetes and depression – both of which tend to occur at higher rates in persons with psoriasis – could also help improve compliance rates, according to Dr. Jackson (Dermatology. 2012;225[2]:121-6). .

“Especially if patients are heavy, if they smoke, if their lipids are high, if they have high blood pressure, or a history of heart disease, it’s important to remember that all of these things are connected to chronic inflammation. I think if we keep that in mind, we can have a better health outcome overall,” Dr. Jackson said.

A survey of 163 psoriasis patients published in 2012 found that comorbidities significantly affected patients’ preferences for psoriasis treatments: Those with psoriatic arthritis were more focused on the probability of benefit (P = .037), those with CVD worried about the probability of side effects (P = .046), and those with depression were concerned about treatment duration (P = .047), and cost (P = .023) (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Oct 19;67[3]:363-72).

Because psoriasis is also associated with higher prevalence and incidence rates of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, particularly in patients with severe psoriasis, Dr. Jackson recommended screening for these diseases when monitoring patients during their follow-up visits (JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Jan;149[1]:84-91).

“Metabolic syndrome gives you more trouble controlling psoriasis and vice versa,” Dr. Jackson said. “It’s important to tell patients that the better health they are in, the better their medicines will work, and the better response their psoriasis will have.”

Dr. Jackson has financial ties to several pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Amgen, Dermira, Galdera, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and others.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL CARIBBEAN DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Guttate Psoriasis Outcomes

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

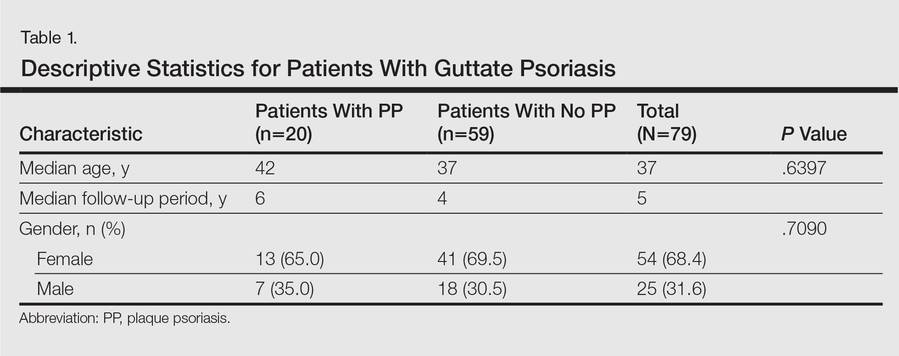

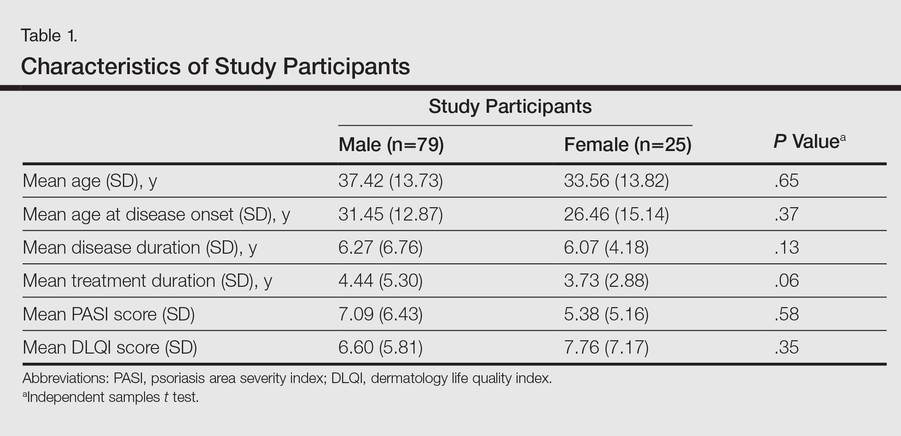

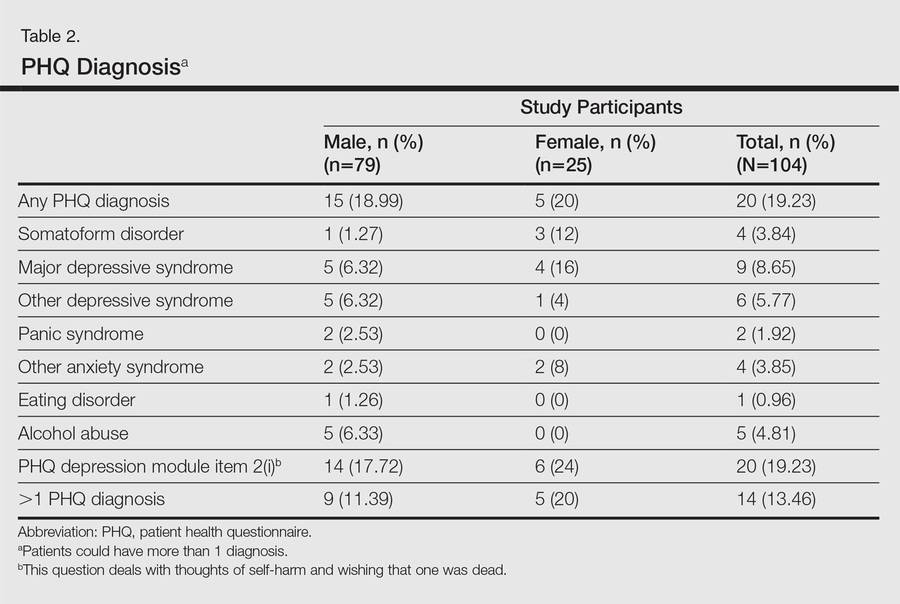

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

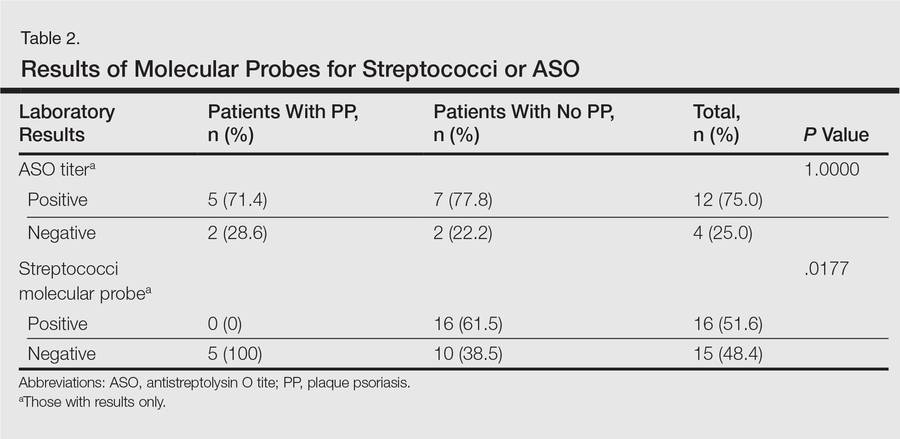

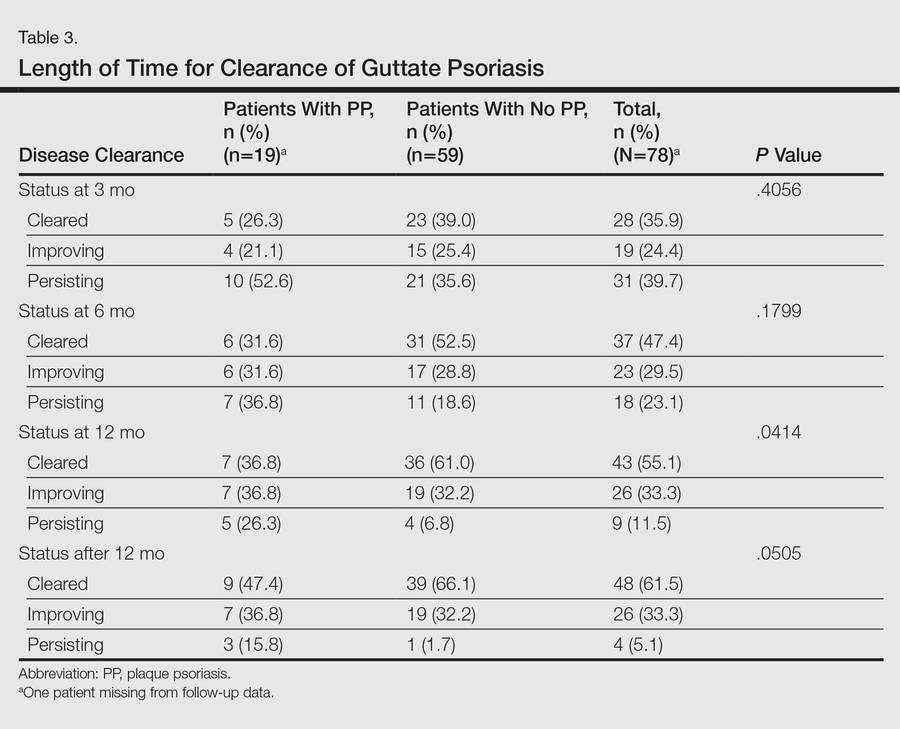

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

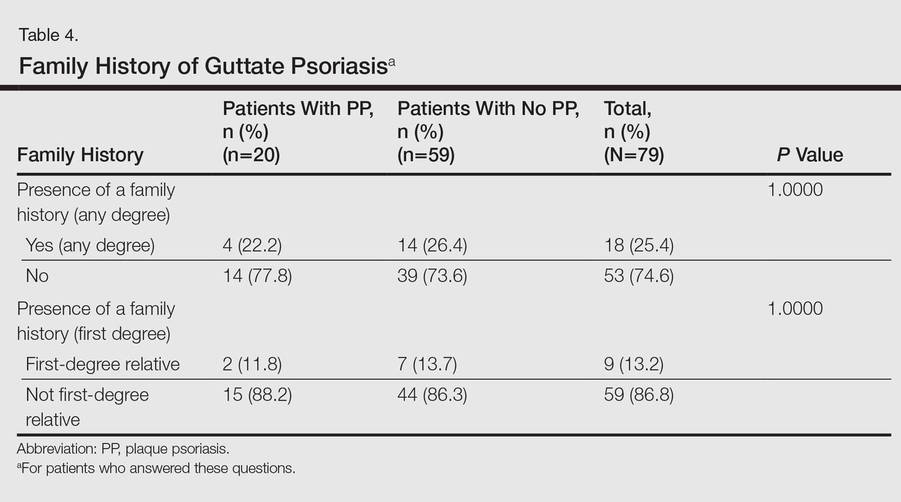

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

Guttate psoriasis (GP) typically occurs abruptly following an acute infection such as streptococcal pharyngitis. It is thought to have a good prognosis and show rapid resolution; however, there are limited studies addressing long-term outcomes of GP, particularly the probability of developing chronic plaque psoriasis (PP) following a single episode of acute GP.

Ko et al1 reported a long-term follow-up study of Korean patients with acute GP. The investigators determined that 19 of 36 participants (38.9%) with acute GP went on to develop chronic PP over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years. Martin et al2 reported a smaller follow-up study of 15 patients in England; 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) developed chronic PP within 10 years.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was performed using data from the Geisinger Medical Center (Danville, Pennsylvania) electronic medical records from January 2000 to September 2012 to identify medical records that showed a specific clinical diagnosis of GP or a diagnosis of either dermatitis or psoriasis with a positive molecular probe for streptococci or antistreptolysin O (ASO) titer. (A molecular probe is used in place of culture for streptococcal pharyngeal specimens at our institution.) A separate search of the Co-Path database for biopsy-proven GP also was performed. Each medical record was reviewed by one of the authors (L.F.P.) to confirm the true diagnosis of GP. Exclusion criteria included a prior diagnosis of PP or a follow-up period of less than 1 year. Based on this chart review, the prevalence of developing chronic PP in patients with GP was determined. The patients were split into 2 cohorts: those who had a single episode of GP with resolution versus those who developed PP. We compared the clinical characteristics to those who developed chronic PP. The clinical characteristics that were recorded included patient age; whether or not the patient developed PP; length of time for clearance of GP; molecular probe or ASO results; family history; GP treatment used; smoking status; and comorbid conditions such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabete mellitus, and obesity, which were lumped under the category of metabolic syndrome due to their low prevalence individually.

The study group data set contained 79 patients with GP who had a history of at least 1 year of follow-up. Descriptive statistics of the patients were provided for continuous and categorical variables in the study. Continuous variables were described using the mean and SD or, for skewed distributions, the median and interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles), while categorical variables were presented using frequency counts and percentages. Comparisons between groups were tested using 2-sample t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or Pearson χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Results

A total of 79 patients were included in the study. Descriptive statistics for the total patient population as well as those who did and did not develop PP are shown in Table 1. The median age of patients was 37 years. The median follow-up time was 5 years. The majority of patients were female (68.4%). There were 20 patients (25.3%) who developed PP and 59 (74.7%) who did not (95% CI, 0.1-0.36).

Molecular probes for streptoccoci were obtained from 31 patients (39.2%) during the workup for GP. Patients who had a molecular probe and developed PP were less likely to have had a molecular probe that was positive for streptococci versus patients who did not develop PP (0% vs 61.5%; P=.0177)(Table 2). Patients who developed PP were more likely to have persistent GP at 12 months than patients who did not develop PP (26.3% vs 6.8%, respectively; P=.0414). At the end of the observation period, 4 patients (5.1%) did not yet show GP clearance. The patients who developed PP were more likely to have had a case of GP that never cleared than patients who did not develop PP (15.8% vs 1.7%; P=.0505)(Table 3).

No significant differences were detected among those who developed PP compared to those who did not with respect to any degree of family history of psoriasis (22.2% vs 26.4%; P=1.0000)(Table 4). There were no significant differences in the value of a positive ASO titer between groups (Table 2), but it should be noted that the small number of patients with positive values in each group impacts a test’s power to detect statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in the likelihood of developing PP if a patient was treated with systemic steroids or antibiotics (data not shown). Additionally, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity were not predictive of evolution of GP into PP (data not shown).

Comment

Ryan et al3 noted in a report on research gaps in psoriasis that studies are needed to validate frequency and characteristic factors associated with spontaneous remission for different phenotypes of psoriasis, including disease severity, patient age, morphologic attributes of plaques, and comorbidities. Our analysis attempts to bridge this gap in reference to type, specifically GP, and factors associated with development of chronic PP.

Our study showed that 20 of 79 patients (25.3%) with GP went on to develop chronic PP. The incidence is slightly lower than in prior smaller studies from Korea and England, which reported incidence rates of 38.9% and 33.3%, respectively.1,2 Although Ko et al1 noted that a younger age of onset was more frequently found in the cohort with complete remission of GP, this finding was not observed in our study. Although only a minority of patients underwent a molecular probe for streptococci, of those who were tested and had positive results, they were significantly less likely to develop chronic PP (P=.0177). This finding supports the classic teaching that GP originates after an episode of a streptococcal infection. Of those who developed PP, only one-fourth had been tested for streptococci via molecular probe and all were negative. Interestingly, there was no difference noted in those that had ASO titers drawn (P=1.0000). Although the data were too low to achieve statistical significance, this finding contrasts with Ko et al1 who reported that a high ASO titer correlated with a good prognosis (ie, GP did not evolve into PP). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing PP seen in patients that were treated with antibiotics (P=.1651), suggesting that obtaining a molecular probe that is positive for streptococci may be predictive of prognosis (ie, resolution) and thus is a reasonable diagnostic test to obtain. We do recognize that nonpharyngeal sources for streptococci may occur (ie, perianal), but these data were not captured in our patient population.

In our study, patients were more likely to develop chronic PP if they had a GP history that was longer than 12 months. Ko et al1 also showed that GP patients who did not develop PP were typically cleared after 8 months. There were no statistical differences noted when comparing the different treatments used to treat GP. It appears that the rapidity with which the episode clears is more predictive than the method used to clear it.

There were several limitations to this study including the small number of patients, the median 5-year follow-up time, and the retrospective design.

Conclusion

Based on our cohort study, we have concluded that GP evolves into chronic PP in approximately 25% of cases. Obtaining a group A streptococcal molecular probe or culture may serve as a prognostic tool, as physicians should recognize that GP flares associated with a positive result indicate a favorable prognosis. Additionally, GP flares that resolve within the first year of an outbreak, regardless of treatment choice, are less likely to be followed by chronic PP.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

- Ko HC, Jwa SW, Song M, et al. Clinical course of guttate psoriasis: long-term follow up study. J Dermatol. 2010;37:894-899.

- Martin BA, Chalmers RJ, Telfer NR. How great is the risk of further psoriasis following a single episode of acute guttate psoriasis? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:717-718.

- Ryan C, Korman NJ, Gelfand JM, et al. Research gaps in psoriasis: opportunities for future studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:146-167.

Practice Points

- Following an initial episode of guttate psoriasis, a patient has a 25.3% chance of developing plaque psoriasis (PP).

- A streptococci culture can be prognostic; if the culture is positive, the patient is less likely to develop PP.

- If the patient’s rash clears within 1 year, he/she is less likely to develop PP.

Psoriasis-Associated Fatigue: Pathogenesis, Metrics, and Treatment

Fatigue is defined as “an overwhelming, sustained sense of exhaustion and decreased capacity for physical and mental work,”1 and it is experienced by most patients with chronic disease. There are 2 types of fatigue: acute and chronic.2 Acute fatigue typically is caused by an identified insult (ie, injury), is self-limited, and is relieved by rest. Chronic fatigue, which may have multiple unknown causes, may accompany chronic illness and lasts longer than 6 months.2 In chronic disease, fatigue can originate peripherally (neu romuscular dysfunction outside of the central nervous system) or centrally (neurotransmitter activity within the central nervous system). Generally, central fatigue is more relevant in patients with chronic disease; however, both central and peripheral fatigue frequently coexist.

Fatigue, even with its accepted definition, is a nonspecific symptom, making it difficult to measure. Because of its subjective nature and the lack of effective therapies, clinicians often ignore fatigue. Still, patients with chronic disease continue to cite fatigue as one of the most challenging aspects of their disease that frequently decreases their quality of life (QOL).2

Fatigue has been well recognized in a number of chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis,3,4 systemic lupus erythematosus,5 fibromyalgia,6 and primary Sjögren syndrome.7 Similarly, fatigue is a frequent concern among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.8 Given the prevalence and significance of psoriasis-associated fatigue,9 new efforts are needed to understand its pathophysiology, to develop new metrics for its evaluation, and to investigate therapeutic strategies to target it clinically. The following discussion provides an overview of the association between fatigue and psoriatic disease as well as the commonly used metrics for evaluating fatigue. Possible therapeutic agents with which to manage fatigue in this patient population also are provided.

Pathogenesis of Psoriasis-Associated Fatigue

Immunologic/Molecular Basis for Psoriasis-Associated Fatigue

Several theories aim to explain the pathophysiology of fatigue in patients with psoriatic disease. Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by sharply demarcated erythematous plaques with adherent scale (Figure 1). Many in vitro studies have demonstrated the complex cytokine network that underlies the histopathologic alterations we observe in psoriatic lesions.10,11 Until recently, psoriasis was considered a type I autoimmune disease with strong TH1 signaling, influenced by IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-12.12 TH1-producing proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and IFN-γ are elevated in psoriatic lesions.13 Studies on the efficacy of ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-12 and IL-23, demonstrate the integral role of the immune system in psoriasis pathogenesis as the production of IL-12 polarizes T cells into TH1 cells.14,15 However, in recent years, TH17 cells have been linked to autoimmune inflammation16 and have been localized to the dermis in psoriatic lesions.17

Among a milieu of inflammatory cytokines, IL-1 is crucial for the early differentiation of TH17 cells.18 The IL-1 family of cytokines serve as primary mediators of inflammation with members including the IL-1 agonists (IL-1α, IL-1β),19 IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA),20 and IL-1 receptor type II (IL-1RII).20 The latter two inhibit IL-1 agonists from binding to their receptor (IL-1RI).19,20 A study by Yoshinaga et al21 investigated the level of inflammatory cytokines within lesional and nonlesional psoriatic skin, finding elevated levels of IL-1β in lesional skin. Another study found that IL-1β expression was increased 357% within biopsied psoriasiform lesions from flaky-skin mice, a useful model to examine the hyperproliferative alterations in the skin. This same study revealed that in vivo IL-1β neutralization alleviated the psoriasiform features in these same mice, suggesting IL-1β is integral to psoriasis pathogenesis.22

Evidence indicates that the aforementioned inflammatory mediators may contribute to psoriasis-associated fatigue. When the peripheral immune system is continuously activated, such as in psoriasis, the peripherally produced proinflammatory cytokines and subsequent immune signaling are monitored by the brain via afferent nerves, cytokine transporters at the blood-brain barrier, and IL-1 receptors on macrophages and endothelial cells of brain venules.23 For example, subseptic doses of lipopolysaccharide injected into rats induced messenger RNA expression of IL-1β in the choroid plexus, circumventricular organs, and the meninges,24 sites where cytokines can enter the blood-brain barrier via diffusion or cytokine transporters.23 These results may suggest a pathway that relays the peripheral immune signals that underlie psoriatic disease to the brain, resulting in activation of brain circuitry that mediates various negative behavioral responses, including fatigue.23 Following a central IL-1β infusion in mice, investigators found a significant decrease in the running performance (P<.01)25; the same infusion increased lethargy, malaise, and fatigue in rats.26 Interestingly, administration of IL-1RA significantly increased run time to fatigue (P<.05), supporting the hypothesis that IL-1β plays an important role in fatigue.25 Other investigators found that administration of many cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) into rats induced depressivelike behaviors27 and suppressed locomotor activity.28 Lastly, another investigation found that IL-1RI knockout mice were resistant to symptoms of sickness, such as social exploration, anorexia, immobility, and weight loss, following IL-1β injections.29 Although the translatability of these studies to humans is not entirely clear, one study found that the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1 and TNF-α were elevated in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.30 Furthermore, a 2013 systematic review found that several serum inflammatory markers including IL-6 and TNF-α were elevated in patients with severe plaque psoriasis compared to healthy controls.31 Therefore, these shared inflammatory cytokines may contribute to and explain the pathogenesis of both fatigue and psoriasis.

Confounding Factors

Although fatigue may be partially explained by the joint effect of inflammatory mediators on both the skin and the brain, there is evidence to suggest that other confounding factors may modify this association and affect its clinical presentation. The pathophysiology of fatigue in psoriasis may not be strictly immunologic; the environmental, psychological, and physical effects of psoriasis may all contribute to and perpetuate fatigue.9,32,33 Interestingly, the pathophysiology of psoriasis involves many cytokines also known to contribute to features of the metabolic syndrome.34 For example, elevated levels of free fatty acids, TNF-α, and IL-6 act in concert to promote inflammation, alter glucose metabolism, and dysregulate endothelial cell function, contributing to dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular disease.35 A systematic review found a high prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis and have found that those with more severe disease have an even greater risk for developing metabolic syndrome.34

Numerous studies have documented that upward of 80% of patients consider psoriasis to have a major impact on their QOL.36-38 The National Psoriasis Foundation assessed patients’ perspectives on the social, physical, and psychological aspects of their disease, finding that health-related QOL is impaired in patients with psoriatic disease.36,39 Patients reported their disease interfered with overall emotional well-being and life enjoyment and cited feelings of anger, frustration, helplessness, embarrassment, and self-consciousness, all of which can influence fatigue.36,39 Pain and pruritus (Figure 2) can interrupt sleep and thus may also contribute to symptoms of fatigue.40 Patients with psoriatic disease have a higher incidence of both depression and anxiety compared with the general population. Another study found that patient-reported factors of disability, pain, and fatigue were associated with clinical depression and anxiety; however, these factors are commonly observed in this cohort of patients and thus it is unclear whether they are predictors of or the result of depression.38

Furthermore, psoriatic disease leads to considerable economic burdens; one study (N=5604) found that among respondents who were not employed, 92% reported they were unemployed solely due to their psoriatic disease.36 One study explored the relationship between fatigue, work disability, and psoriatic arthritis, finding that the association between fatigue and work productivity loss persisted after controlling for cutaneous/musculoskeletal activity.41 However, another investigation revealed contradicting results, finding that improvements in fatigue correlated with improvements in joint and skin pain.9

Therefore, we can conclude that the pathogenesis of psoriasis-associated fatigue is the result of a multifactorial immunologic, psychologic, and physiologic pathway that triggers symptoms of exhaustion and lethargy. Fatigue is a complex multidimensional symptom activated by psoriatic disease, directly by shared inflammatory cytokines and indirectly by factors of disease activity and psychiatric distress that inherently influence somatic manifestations of fatigue. Regardless of its pathogenesis, these data and observations highlight the importance of fatigue symptoms and the need for new therapeutics to target this debilitating disease.

Measurement of Fatigue in Psoriasis

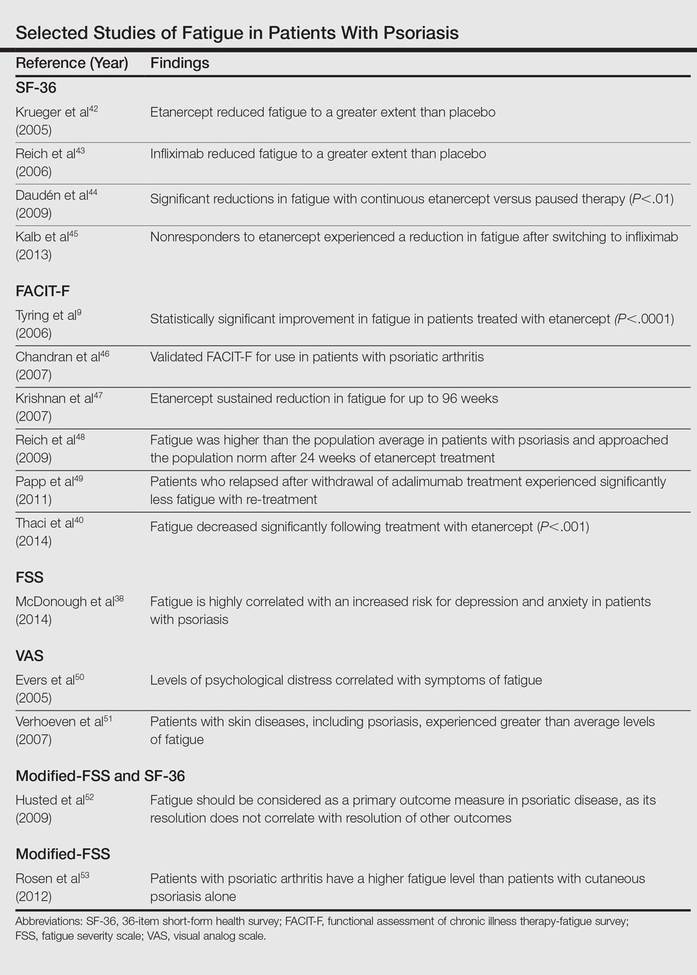

A patient’s level of fatigue is not objectively quantifiable. For this reason, clinicians and investigators have relied on self-report instruments to gauge fatigue (Table).9,38,40,42-53 These survey instruments each have distinct advantages and disadvantages, though all are subject to common difficulties. Many rely on the literacy of patients and their interpretation of each item, which can make completing the survey difficult and yield variability between subjects. Patients are inaccurate in self-reporting even measurable characteristics such as height and weight,54 which introduces an element of uncertainty in the reporting of subjective symptoms (ie, fatigue). Lastly, there are several biases implicit in self-reporting including recall bias, selective recall, and digit preference.55

When analyzing fatigue due to a chronic disease, several symptoms may be misconstrued or interfere with the interpretation of fatigue. For instance, patients with multiple sclerosis may confuse neuropathy-associated muscle weakness with fatigue. These interactions can be controlled for in self-report instruments and validated through careful study of many patients. Disease-specific questionnaires have been validated for use in several diseases,56-58 though none have been validated for cutaneous psoriasis in the absence of psoriatic arthritis. The need for validated instruments in psoriasis is great, as symptoms such as sleep disturbance and arthralgia may confound metrics of fatigue.

Thus far, 4 self-report instruments have been used to study fatigue in psoriasis: the medical outcomes 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36), the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue, the fatigue severity scale (FSS), and the visual analog scale (VAS) for fatigue.

The SF-36 is a 36-item survey designed to measure 8 dimensions of health status in patients with chronic disease.59 Items are answered using a 3- to 6-point Likert scale, or in a yes/no format. Although the SF-36 is typically administered by a trained interviewer, it relies on a patient’s interpretation of language that must be used to describe their level of fatigue, which may not capture the full range of symptoms. Also, the length of the survey makes it impractical for use in clinical practice.

The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue survey is validated for use in psoriatic arthritis. It is similar to the SF-36 in its use of a 5-point Likert scale to answer each of 13 items. It improves on the SF-36 model by including questions about associated symptoms (ie, pain, medication side effects) that may interfere with the measurement of fatigue. It also investigates the impact of fatigue on several areas of functioning. However, it is subject to the same pitfalls of interpretation and a rigid scale with which to answer questions.

The FSS is another Likert scale–based instrument that gauges both level of fatigue and its impact using 9 items and a 7-point scale. Investigators used the FSS to uncover an association between increasing fatigue scores and depression in patients with psoriatic disease.38

The VAS overcomes many of the language and interpretation issues inherent in Likert scale–based instruments. Patients are presented with a single item in which they are asked to plot their level of fatigue on a continuous line, with one end representing no fatigue and the other end the worst possible fatigue. Although VAS adds simplicity of response and removes some ambiguity from surveying, it provides no information about the functional impact of fatigue on patients. It also does not provide a method to control for other symptoms.

Treatment of Psoriasis-Associated Fatigue

Much of our understanding of psoriasis-associated fatigue arises from therapeutic clinical trials. Because increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines are associated with fatigue, it has been suggested that blocking these cytokines with biologic agents may relieve fatigue symptoms. For example, investigators found that patients treated with etanercept, a soluble TNF-α receptor fusion protein, had clinically meaningful improvement in fatigue compared to those receiving placebo, with sustained improvements at 96 weeks.9,47 We must note, however, that the decrease in fatigue correlated with improvements in cutaneous/arthritic pain. Nevertheless, another study found that treatment with the same drug decreased fatigue in patients with psoriasis, even after controlling for improvements in the psoriasis area severity index score.40 Adalimumab is another monoclonal antibody for TNF-α that has caused a notable decline in fatigue symptoms.49

These data suggest that biologic agents are useful in the treatment of fatigue. Biologic agents are frequently administered to patients with moderate to severe psoriasis in whom more conservative treatments previously failed. However, cutaneous/arthritic disease severity is not always correlated with fatigue, so these data may urge clinicians to lower their threshold for treatment with biologics in patients with substantial fatigue symptoms. Although further investigations are necessary, we may even consider using a biologic therapy for severe fatigue in those without severe psoriatic disease.

Conclusion

Fatigue is a multidimensional symptom, impacted both directly and indirectly by psoriasis pathophysiology. The prevalence of fatigue within this patient population suggests that clinicians need to recognize the symptom as a core domain in psoriasis evaluation. Although a host of metrics have been used to quantify/qualify fatigue, there remains a need for a validated instrument for assessing fatigue in patients with psoriatic disease.

Biologic agents have proven useful in the treatment of psoriasis-associated fatigue. The central role of proinflammatory cytokines to both fatigue and psoriasis pathogenesis provide insight into potential treatment targets. Understanding the overlapping pathophysiology of psoriasis and fatigue provides an avenue for developing innovative strategies to target molecules implicated in the activation of the immune system. In the future, it may be possible to predict the severity of fatigue by measuring the levels of serum inflammatory cytokines; in fact, a new study aims to identify a panel of soluble biomarkers that can predict joint damage in psoriatic arthritis.60 Taken together, the findings described suggest that further study is needed to characterize, measure, and treat psoriasis-associated fatigue.

- NANDA Nursing Diagnoses: Definitions and Classification, 1999-2000. Philadelphia, PA: NANDA International; 1999.

- Swain MG. Fatigue in chronic disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2000;99:1-8.

- Wolfe F, Hawley DJ, Wilson K. The prevalence and meaning of fatigue in rheumatic disease. J Rheumatol. 1996;23:1407-1417.

- van Hoogmoed D, Fransen J, Bleijenberg G, et al. Physical and psychosocial correlates of severe fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49:1294-1302.

- Cleanthous S, Tyagi M, Isenberg DA, et al. What do we know about self-reported fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus? Lupus. 2012;21:465-476.

- Ulus Y, Akyol Y, Tander B, et al. Sleep quality in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis: associations with pain, fatigue, depression, and disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(6, suppl 69):S92-S96.

- Segal B, Thomas W, Rogers T, et al. Prevalence, severity, and predictors of fatigue in subjects with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1780-1787.

- Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Strand V, et al. Consensus on a core set of domains for psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1167-1170.

- Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35.

- De Rosa G, Mignogna C. The histopathology of psoriasis. Reumatismo. 2007;59(suppl 1):46-48.

- Nickoloff BJ, Xin H, Nestle FO, et al. The cytokine and chemokine network in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:568-573.

- Zaba LC, Fuentes-Duculan J, Eungdamrong NJ, et al. Psoriasis is characterized by accumulation of immunostimulatory and Th1/Th17 cell-polarizing myeloid dendritic cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:79-88.

- Austin LM, Ozawa M, Kikuchi T, et al. The majority of epidermal T cells in psoriasis vulgaris lesions can produce type 1 cytokines, interferon-gamma, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, defining TC1 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) and TH1 effector populations: a type 1 differentiation bias is also measured in circulating blood T cells in psoriatic patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:752-759.

- Lebwohl M, Papp K, Han C, et al. Ustekinumab improves health-related quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from the PHOENIX 1 trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:137-146.

- Sabat R, Wolk K. Pathogenesis of psoriasis. In: Sterry W, Sabat R, Philipp S, eds. Psoriasis: Diagnosis and Management. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014:28-48.

- Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. T(H)-17 cells in the circle of immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:345-350.

- Lowes MA, Kikuchi T, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Psoriasis vulgaris lesions contain discrete populations of Th1 and Th17 T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1207-1211.

- Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, et al. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by IL-1 signaling. Immunity. 2009;30:576-587.

- Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood. 2011;117:3720-3732.

- Jensen LE. Targeting the IL-1 family members in skin inflammation. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:1211-1220.

- Yoshinaga Y, Higaki M, Terajima S, et al. Detection of inflammatory cytokines in psoriatic skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:158-164.

- Schon M, Behmenburg C, Denzer D, et al. Pathogenic function of IL-1 beta in psoriasiform skin lesions of flaky skin (fsn/fsn) mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123:505-510.

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, et al. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46-56.

- Quan N, Stern EL, Whiteside MB, et al. Induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine mRNAs in the brain after peripheral injection of subseptic doses of lipopolysaccharide in the rat. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;93:72-80.

- Carmichael MD, Davis JM, Murphy EA, et al. Role of brain IL-1beta on fatigue after exercise-induced muscle damage. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1344-R1348.

- Swain MG, Beck P, Rioux K, et al. Augmented interleukin-1beta-induced depression of locomotor activity in cholestatic rats. Hepatology. 1998;28:1561-1565.

- Kent S, Bluthé RM, Kelley KW, et al. Sickness behavior as a new target for drug development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:24-28.

- Lacosta S, Merali Z, Anisman H. Influence of interleukin-1beta on exploratory behaviors, plasma ACTH, corticosterone, and central biogenic amines in mice. Psychopharmacology. 1998;137:351-361.

- Bluthé RM, Laye S, Michaud B, et al. Role of interleukin-1beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behaviour: a study with interleukin-1 type I receptor-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4447-4456.

- Maes M, Twisk FN, Ringel K. Inflammatory and cell-mediated immune biomarkers in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and depression: inflammatory markers are higher in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome than in depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81:286-295.

- Dowlatshahi EA, van der Voort EAM, Arends LR, et al. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:266-282.

- Jankovic S, Raznatovic M, Marinkovic J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis.J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:29-36.

- Carneiro C, Chaves M, Verardino G, et al. Fatigue in psoriasis with arthritis. Skinmed. 2011;9:34-37.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:654-662.

- Sterry W, Strober BE, Menter A. Obesity in psoriasis: the metabolic, clinical and therapeutic implications. report of an interdisciplinary conference and review. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:649-655.

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, et al. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003-2011. PloS One. 2012;7:e52935.

- de Korte J, Sprangers MA, Mombers FM, et al. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;9:140-147.

- McDonough E, Ayearst R, Eder L, et al. Depression and anxiety in psoriatic disease: prevalence and associated factors. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:887-896.

- Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, et al. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280-284.

- Thaci D, Galimberti R, Amaya-Guerra M, et al. Improvement in aspects of sleep with etanercept and optional adjunctive topical therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from the PRISTINE trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:900-906.

- Walsh JA, McFadden ML, Morgan MD, et al. Work productivity loss and fatigue in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1670-1674.

- Krueger GG, Langley RG, Finlay AY, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of psoriasis improvement with etanercept therapy: results of a randomized phase III trial. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1192-1199.

- Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, et al. Improvement in quality of life with infliximab induction and maintenance therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:1161-1168.

- Daudén E, Griffiths CE, Ortonne JP, et al. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes in moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients receiving continuous or paused etanercept treatment over 54 weeks: the CRYSTEL study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1374-1382.

- Kalb RE, Blauvelt A, Sofen HL, et al. Effect of infliximab on health-related quality of life and disease activity by body region in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and inadequate response to etanercept: results from the PSUNRISE trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:874-880.

- Chandran V, Bhella S, Schentag C, et al. Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 2007;66:936-939.

- Krishnan R, Cella D, Leonardi C, et al. Effects of etanercept therapy on fatigue and symptoms of depression in subjects treated for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis for up to 96 weeks. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1275-1277.

- Reich K, Segaert S, Van de Kerkhof P, et al. Once-weekly administration of etanercept 50 mgimproves patient-reported outcomes in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatology. 2009;219:239-249.

- Papp K, Crowley J, Ortonne JP, et al. Adalimumab for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety of retreatment and disease recurrence following withdrawal from therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:434-441.

- Evers AW, Lu Y, Duller P, et al. Common burden of chronic skin diseases? contributors to psychological distress in adults with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1275-1281.

- Verhoeven EW, Kraaimaat FW, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. Prevalence of physical symptoms of itch, pain and fatigue in patients with skin diseases in general practice. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1346-1349.