User login

Improving Prognosis in Hepatoblastoma: Evolving Risk Stratification and Treatment Strategies

Improving Prognosis in Hepatoblastoma: Evolving Risk Stratification and Treatment Strategies

Introduction

Hepatoblastoma accounts for most pediatric liver cancers, but accounts for only 1% of all malignancies in children. Rates of hepatoblastoma have increased gradually over the past 20 years for unclear reasons, but it remains a rare malignancy. In the 1970s, only a small percentage of patients survived long-term. Today, 5-year survival rates range from 65% to over 90%, depending on risk factors, thanks to recent advancements in the understanding and treatment of hepatoblastoma.1-5 Improved risk stratification has led to better staging and more personalized treatment approaches. To further improve survival, current research is concentrated on improving outcomes in the most challenging patient subsets, such as those with metastatic disease and patients with disease relapse.

Background

Hepatoblastoma is typically diagnosed in the first 2 years of life.6 Accounting for more than 60% of pediatric hepatic malignancies worldwide, the incidence of hepatoblastoma is increasing. Results from a study evaluating the incidence between 2001 and 2017 showed a 2% annual increase documented in children aged from birth to 4 years in the United States, climbing to 5.8% annually among children aged 5 to 9 years.2 Risk factors for hepatoblastoma include maternal preeclampsia, premature birth, and parental smoking.7 The degree to which each of these factors plays a role is uncertain. A genetic etiology is suspected in a minority of hepatoblastoma cases, but it is associated with several genetic diseases, including Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, and Prader-Willi syndrome.8 Genetic mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway that result in the accumulation of beta-catenin have also been found in sporadic, nonfamilial cases.9

Although this condition generally presents as a single abdominal mass in the right lobe of the liver, multifocal hepatoblastoma at diagnosis does occur.10 In most patients, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is significantly elevated.11 An estimated 20% of patients present with metastases, which are most commonly found in the lung.12 While ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to define the extent of the tumor in the liver, a chest CT is appropriate to look for metastases beyond the liver.13

Of the 2 broad histological categories commonly used to characterize hepatoblastoma, the more common epithelial form consists of fetal or embryonal liver cells. The mixed epithelial-mesenchymal form that accounts for 20% to 30% of hepatoblastomas features epithelial and primitive mesenchymal tissue, often with osteoid tissue or cartilage6; both have numerous histological subtypes. For example, the epithelial type can be further characterized by a well- or poorly-differentiated appearance, while the mixed type can be subdivided by the presence or absence of teratoid features.

Prior to 2017, there was considerable disparity in the way hepatoblastomas were characterized and staged among the major research consortiums. This issue was addressed when a consortium was established in which pediatric oncology groups pooled their data. The Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC) released the PRETEXT (PRETreatment EXTent of disease) approach.7,14 Based on comprehensive data from 1605 children participating in multicenter trials, the CHIC risk stratification defines and provides risk trees for very low-, low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. The most important predictors included AFP levels, patient age, extent of disease in the liver (particularly involving major hepatic veins), and the presence of metastases.

Further improvements to the diagnosis and staging of hepatoblastoma are credited to consensus-based recommendations for imaging that were created in the context of the PRETEXT staging system.13 While ultrasound is recommended for the initial approach to diagnosis, this consensus calls for MRI with hepatobiliary contrast to better characterize the lesion and detect satellite lesions. This form of imaging is also recommended for follow-up after treatment, but results should be interpreted in the context of biomarkers, such as AFP levels, pathologic grading, and tumor subtypes.

In patients with the most common familial disorders associated with a predisposition for hepatoblastoma, such as adenomatous polyposis, Beckwith-Weidemann spectrum, or trisomy 18, regular surveillance for hepatoblastoma is recommended during the early years of life.8 Characterization of the genetic and molecular features of patients who present with hepatoblastoma might be useful in determining prognosis. Of genetic features, mutations in the CTNNB1 gene are the most common, but several genes in the Wnt pathway are also linked to hepatoblastoma formation.9

Along with the progress in subtyping patients by genetics, epigenetics, and molecular features, there is a growing appreciation for the heterogeneity of hepatoblastoma and the likelihood that treatment strategies can be better individualized to improve outcomes in high-risk patients. This progress is expected to accelerate further when results from the results from the Pediatric Hepatic International Tumor Trial (PHITT) are published. These data are expected to be available in 2025, and may help with prognostication and understanding the biology of hepatoblastoma in relation to outcomes.

Treatment Strategies in Hepatoblastoma

For low-grade hepatoblastoma, the first-line therapy is surgery, which can be sufficient for cure without relapse in selected patients with PRETEXT group 1 disease. Although only 40% to 60% of patients have resectable disease at diagnosis,10 there are several strategies to shrink tumor bulk, particularly chemotherapy due to the relatively high sensitivity of hepatoblastoma to cytotoxic therapies. The intensity of chemotherapy is increased relative to risk.11 For example, cisplatin-based regimens are considered for low-risk patients, while additional therapies, such as doxorubicin, irinotecan, or both, are added in patients at higher risk. Cure is common if these regimens permit a margin-free resection, although relapse does occur in a subset of patients.

If adequate debulking of the tumor cannot be achieved with conventional surgery, liver transplantation is typically offered for patients without extrahepatic disease or after distant metastases have been successfully excised. With liver transplantation and combination therapies to inhibit relapse associated with seeding, long-term survival rates of 80% have been reported.3 Judicious use of transplantation in patients with high-risk disease that raises the potential for relapse has been credited with rates of long-term survival that exceed 80% in some series. However, there is concern of offering transplantation when it is not necessary. In patients who are high risk with multiple lesions in the liver, there is a general agreement that transplantation reduces the likelihood of subsequent relapse; however, as the precision of aggressive resection coupled with effective chemotherapy has improved, there are more patients in whom the optimal choice might not be debated by experts.

Review articles typically cite the likelihood of an overall 5-year survival in patients with hepatoblastoma as being on the order of 80%.1 This rate includes children with late-onset disease, which is generally associated with a worse prognosis, and patients who eventually experience disease relapse. Survival rates are now likely to be substantially higher, with progress developing better treatment protocols for both groups. In the absence of high-risk features, long-term survival rates of 90% or higher are now being reported in some centers with high relative volumes of hepatoblastoma, regardless of baseline risks.

PHITT

The rarity of hepatoblastoma poses a significant challenge to conducting prospective studies with sufficient sample sizes to evaluate the overall efficacy of treatments and their effectiveness in patient subgroups based on specific clinical characteristics and disease severity. PHITT is the first international collaborative liver tumors trial to use a consensus approach. Centers in Europe, Japan, and the United States are participating through regional cancer study consortia. The Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, a leader in hepatoblastoma management in the United States, is anchoring this effort for the Children’s Oncology Group.

In addition to assessing treatment strategies in larger patient cohorts, PHITT is expanding the data available to correlate outcomes across different stages and risk categories based on histological and biological classifications. Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma are being addressed in PHITT, but the design schema for these malignancies differs. For patients enrolled with hepatoblastoma, 4 risk groups have been defined, ranging from very low to high. Within these risk categories, flow charts provide guide selection of treatments based on clinical and disease features.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center is one of the most active centers for the treatment of hepatoblastoma in the Unites States but manages only 15 to 20 cases of this rare disease per year. PHITT is expected to play a critical role in achieving a high level of valuable data, and the first sets of outcomes from this collaboration are anticipated to be available in early 2025. As the study progresses, meaningful data are expected for the most challenging and some of the rarest hepatoblastoma risk groups.

Summary

The rates of cure are now approaching 100% with surgery and chemotherapy in patients with localized or locally advanced hepatoblastoma. For more advanced, unresectable disease, liver transplantation is effective in most patients, providing high rates of long-term survival. For patients with relapsed disease, advanced treatment protocols at centers with high relative volumes

of hepatoblastoma are now regularly achieving a second remission—many of which are durable. Although prognosis is less favorable in patients who experience a second relapse, long-term survival is achieved even in a proportion of these children. Substantial rates of response and long-term survival have been common in hepatoblastoma diagnosed at early stages, but the recent progress in advanced hepatoblastoma is credited to more aggressive therapies based on a better understanding of the disease characteristics that allows for individualized therapy. There is hope that the larger pool of data becoming available in 2025 from PHITT will prove to be an additional source of information that guides further advances in managing this rare disease.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Koh KN, Namgoong JM, Yoon HM, et al. Recent improvement in survival outcomes and reappraisal of prognostic factors in hepatoblastoma. Cancer Med. 2021;10(10):3261-3273. doi:10.1002/cam4.3897

- Kahla JA, Siegel DA, Dai S, et al. Incidence and 5-year survival of children and adolescents with hepatoblastoma in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(10):e29763. doi:10.1002/pbc.29763

- Ramos-Gonzalez G, LaQuaglia M, O’Neill AF, et al. Long-term outcomes of liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: a single-center 14-year experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2018:e13250. doi:10.1111/petr.13250

- Zhou S, Malvar J, Chi YY, et al. Independent assessment of the Children’s Hepatic Tumors International Collaboration risk stratification for hepatoblastoma and the association of tumor histological characteristics with prognosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148013. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48013

- Feng J, Polychronidis G, Heger U, Frongia G, Mehrabi A, Hoffmann K. Incidence trends and survival prediction of hepatoblastoma in children: a population-based study. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2019;39(1):62. doi:10.1186/s40880-019-0411-7

- Sharma D, Subbarao G, Saxena R. Hepatoblastoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(2):192-200. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.015

- Heck JE, Meyers TJ, Lombardi C, et al. Case-control study of birth characteristics and the risk of hepatoblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(4):390-395. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2013.03.004

- Ranganathan S, Lopez-Terrada D, Alaggio R. Hepatoblastoma and pediatric hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2020;23(2):79-95. doi:10.1177/1093526619875228

- Curia MC, Zuckermann M, De Lellis L, et al. Sporadic childhood hepatoblastomas show activation of beta-catenin, mismatch repair defects and p53 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(1):7-14. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800977

- Fahy AS, Shaikh F, Gerstle JT. Multifocal hepatoblastoma: what is the risk of recurrent disease in the remnant liver? J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(5):1035-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.036

- Głowska-Ciemny J, Szymanski M, Kuszerska A, Rzepka R, von Kaisenberg CS, Kocyłowski R. Role of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in diagnosing childhood cancers and genetic-related chronic diseases. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(17):4302. doi:10.3390/cancers15174302

- Angelico R, Grimaldi C, Gazia C, et al. How do synchronous lung metastases influence the surgical management of children with hepatoblastoma? An update and systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(11):1693. doi:10.3390/cancers11111693

- Schooler GR, Infante JC, Acord M, et al. Imaging of pediatric liver tumors: A COG Diagnostic Imaging Committee/SPR Oncology Committee white paper. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70(suppl 4):e29965. doi:10.1002/pbc.29965

- Meyers RL, Maibach R, Hiyama E, et al. Risk-stratified staging in paediatric hepatoblastoma: a unified analysis from the Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):122-131. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30598-8

Introduction

Hepatoblastoma accounts for most pediatric liver cancers, but accounts for only 1% of all malignancies in children. Rates of hepatoblastoma have increased gradually over the past 20 years for unclear reasons, but it remains a rare malignancy. In the 1970s, only a small percentage of patients survived long-term. Today, 5-year survival rates range from 65% to over 90%, depending on risk factors, thanks to recent advancements in the understanding and treatment of hepatoblastoma.1-5 Improved risk stratification has led to better staging and more personalized treatment approaches. To further improve survival, current research is concentrated on improving outcomes in the most challenging patient subsets, such as those with metastatic disease and patients with disease relapse.

Background

Hepatoblastoma is typically diagnosed in the first 2 years of life.6 Accounting for more than 60% of pediatric hepatic malignancies worldwide, the incidence of hepatoblastoma is increasing. Results from a study evaluating the incidence between 2001 and 2017 showed a 2% annual increase documented in children aged from birth to 4 years in the United States, climbing to 5.8% annually among children aged 5 to 9 years.2 Risk factors for hepatoblastoma include maternal preeclampsia, premature birth, and parental smoking.7 The degree to which each of these factors plays a role is uncertain. A genetic etiology is suspected in a minority of hepatoblastoma cases, but it is associated with several genetic diseases, including Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, and Prader-Willi syndrome.8 Genetic mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway that result in the accumulation of beta-catenin have also been found in sporadic, nonfamilial cases.9

Although this condition generally presents as a single abdominal mass in the right lobe of the liver, multifocal hepatoblastoma at diagnosis does occur.10 In most patients, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is significantly elevated.11 An estimated 20% of patients present with metastases, which are most commonly found in the lung.12 While ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to define the extent of the tumor in the liver, a chest CT is appropriate to look for metastases beyond the liver.13

Of the 2 broad histological categories commonly used to characterize hepatoblastoma, the more common epithelial form consists of fetal or embryonal liver cells. The mixed epithelial-mesenchymal form that accounts for 20% to 30% of hepatoblastomas features epithelial and primitive mesenchymal tissue, often with osteoid tissue or cartilage6; both have numerous histological subtypes. For example, the epithelial type can be further characterized by a well- or poorly-differentiated appearance, while the mixed type can be subdivided by the presence or absence of teratoid features.

Prior to 2017, there was considerable disparity in the way hepatoblastomas were characterized and staged among the major research consortiums. This issue was addressed when a consortium was established in which pediatric oncology groups pooled their data. The Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC) released the PRETEXT (PRETreatment EXTent of disease) approach.7,14 Based on comprehensive data from 1605 children participating in multicenter trials, the CHIC risk stratification defines and provides risk trees for very low-, low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. The most important predictors included AFP levels, patient age, extent of disease in the liver (particularly involving major hepatic veins), and the presence of metastases.

Further improvements to the diagnosis and staging of hepatoblastoma are credited to consensus-based recommendations for imaging that were created in the context of the PRETEXT staging system.13 While ultrasound is recommended for the initial approach to diagnosis, this consensus calls for MRI with hepatobiliary contrast to better characterize the lesion and detect satellite lesions. This form of imaging is also recommended for follow-up after treatment, but results should be interpreted in the context of biomarkers, such as AFP levels, pathologic grading, and tumor subtypes.

In patients with the most common familial disorders associated with a predisposition for hepatoblastoma, such as adenomatous polyposis, Beckwith-Weidemann spectrum, or trisomy 18, regular surveillance for hepatoblastoma is recommended during the early years of life.8 Characterization of the genetic and molecular features of patients who present with hepatoblastoma might be useful in determining prognosis. Of genetic features, mutations in the CTNNB1 gene are the most common, but several genes in the Wnt pathway are also linked to hepatoblastoma formation.9

Along with the progress in subtyping patients by genetics, epigenetics, and molecular features, there is a growing appreciation for the heterogeneity of hepatoblastoma and the likelihood that treatment strategies can be better individualized to improve outcomes in high-risk patients. This progress is expected to accelerate further when results from the results from the Pediatric Hepatic International Tumor Trial (PHITT) are published. These data are expected to be available in 2025, and may help with prognostication and understanding the biology of hepatoblastoma in relation to outcomes.

Treatment Strategies in Hepatoblastoma

For low-grade hepatoblastoma, the first-line therapy is surgery, which can be sufficient for cure without relapse in selected patients with PRETEXT group 1 disease. Although only 40% to 60% of patients have resectable disease at diagnosis,10 there are several strategies to shrink tumor bulk, particularly chemotherapy due to the relatively high sensitivity of hepatoblastoma to cytotoxic therapies. The intensity of chemotherapy is increased relative to risk.11 For example, cisplatin-based regimens are considered for low-risk patients, while additional therapies, such as doxorubicin, irinotecan, or both, are added in patients at higher risk. Cure is common if these regimens permit a margin-free resection, although relapse does occur in a subset of patients.

If adequate debulking of the tumor cannot be achieved with conventional surgery, liver transplantation is typically offered for patients without extrahepatic disease or after distant metastases have been successfully excised. With liver transplantation and combination therapies to inhibit relapse associated with seeding, long-term survival rates of 80% have been reported.3 Judicious use of transplantation in patients with high-risk disease that raises the potential for relapse has been credited with rates of long-term survival that exceed 80% in some series. However, there is concern of offering transplantation when it is not necessary. In patients who are high risk with multiple lesions in the liver, there is a general agreement that transplantation reduces the likelihood of subsequent relapse; however, as the precision of aggressive resection coupled with effective chemotherapy has improved, there are more patients in whom the optimal choice might not be debated by experts.

Review articles typically cite the likelihood of an overall 5-year survival in patients with hepatoblastoma as being on the order of 80%.1 This rate includes children with late-onset disease, which is generally associated with a worse prognosis, and patients who eventually experience disease relapse. Survival rates are now likely to be substantially higher, with progress developing better treatment protocols for both groups. In the absence of high-risk features, long-term survival rates of 90% or higher are now being reported in some centers with high relative volumes of hepatoblastoma, regardless of baseline risks.

PHITT

The rarity of hepatoblastoma poses a significant challenge to conducting prospective studies with sufficient sample sizes to evaluate the overall efficacy of treatments and their effectiveness in patient subgroups based on specific clinical characteristics and disease severity. PHITT is the first international collaborative liver tumors trial to use a consensus approach. Centers in Europe, Japan, and the United States are participating through regional cancer study consortia. The Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, a leader in hepatoblastoma management in the United States, is anchoring this effort for the Children’s Oncology Group.

In addition to assessing treatment strategies in larger patient cohorts, PHITT is expanding the data available to correlate outcomes across different stages and risk categories based on histological and biological classifications. Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma are being addressed in PHITT, but the design schema for these malignancies differs. For patients enrolled with hepatoblastoma, 4 risk groups have been defined, ranging from very low to high. Within these risk categories, flow charts provide guide selection of treatments based on clinical and disease features.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center is one of the most active centers for the treatment of hepatoblastoma in the Unites States but manages only 15 to 20 cases of this rare disease per year. PHITT is expected to play a critical role in achieving a high level of valuable data, and the first sets of outcomes from this collaboration are anticipated to be available in early 2025. As the study progresses, meaningful data are expected for the most challenging and some of the rarest hepatoblastoma risk groups.

Summary

The rates of cure are now approaching 100% with surgery and chemotherapy in patients with localized or locally advanced hepatoblastoma. For more advanced, unresectable disease, liver transplantation is effective in most patients, providing high rates of long-term survival. For patients with relapsed disease, advanced treatment protocols at centers with high relative volumes

of hepatoblastoma are now regularly achieving a second remission—many of which are durable. Although prognosis is less favorable in patients who experience a second relapse, long-term survival is achieved even in a proportion of these children. Substantial rates of response and long-term survival have been common in hepatoblastoma diagnosed at early stages, but the recent progress in advanced hepatoblastoma is credited to more aggressive therapies based on a better understanding of the disease characteristics that allows for individualized therapy. There is hope that the larger pool of data becoming available in 2025 from PHITT will prove to be an additional source of information that guides further advances in managing this rare disease.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

Introduction

Hepatoblastoma accounts for most pediatric liver cancers, but accounts for only 1% of all malignancies in children. Rates of hepatoblastoma have increased gradually over the past 20 years for unclear reasons, but it remains a rare malignancy. In the 1970s, only a small percentage of patients survived long-term. Today, 5-year survival rates range from 65% to over 90%, depending on risk factors, thanks to recent advancements in the understanding and treatment of hepatoblastoma.1-5 Improved risk stratification has led to better staging and more personalized treatment approaches. To further improve survival, current research is concentrated on improving outcomes in the most challenging patient subsets, such as those with metastatic disease and patients with disease relapse.

Background

Hepatoblastoma is typically diagnosed in the first 2 years of life.6 Accounting for more than 60% of pediatric hepatic malignancies worldwide, the incidence of hepatoblastoma is increasing. Results from a study evaluating the incidence between 2001 and 2017 showed a 2% annual increase documented in children aged from birth to 4 years in the United States, climbing to 5.8% annually among children aged 5 to 9 years.2 Risk factors for hepatoblastoma include maternal preeclampsia, premature birth, and parental smoking.7 The degree to which each of these factors plays a role is uncertain. A genetic etiology is suspected in a minority of hepatoblastoma cases, but it is associated with several genetic diseases, including Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome, familial adenomatous polyposis, and Prader-Willi syndrome.8 Genetic mutations in the Wnt signaling pathway that result in the accumulation of beta-catenin have also been found in sporadic, nonfamilial cases.9

Although this condition generally presents as a single abdominal mass in the right lobe of the liver, multifocal hepatoblastoma at diagnosis does occur.10 In most patients, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is significantly elevated.11 An estimated 20% of patients present with metastases, which are most commonly found in the lung.12 While ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to define the extent of the tumor in the liver, a chest CT is appropriate to look for metastases beyond the liver.13

Of the 2 broad histological categories commonly used to characterize hepatoblastoma, the more common epithelial form consists of fetal or embryonal liver cells. The mixed epithelial-mesenchymal form that accounts for 20% to 30% of hepatoblastomas features epithelial and primitive mesenchymal tissue, often with osteoid tissue or cartilage6; both have numerous histological subtypes. For example, the epithelial type can be further characterized by a well- or poorly-differentiated appearance, while the mixed type can be subdivided by the presence or absence of teratoid features.

Prior to 2017, there was considerable disparity in the way hepatoblastomas were characterized and staged among the major research consortiums. This issue was addressed when a consortium was established in which pediatric oncology groups pooled their data. The Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC) released the PRETEXT (PRETreatment EXTent of disease) approach.7,14 Based on comprehensive data from 1605 children participating in multicenter trials, the CHIC risk stratification defines and provides risk trees for very low-, low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups. The most important predictors included AFP levels, patient age, extent of disease in the liver (particularly involving major hepatic veins), and the presence of metastases.

Further improvements to the diagnosis and staging of hepatoblastoma are credited to consensus-based recommendations for imaging that were created in the context of the PRETEXT staging system.13 While ultrasound is recommended for the initial approach to diagnosis, this consensus calls for MRI with hepatobiliary contrast to better characterize the lesion and detect satellite lesions. This form of imaging is also recommended for follow-up after treatment, but results should be interpreted in the context of biomarkers, such as AFP levels, pathologic grading, and tumor subtypes.

In patients with the most common familial disorders associated with a predisposition for hepatoblastoma, such as adenomatous polyposis, Beckwith-Weidemann spectrum, or trisomy 18, regular surveillance for hepatoblastoma is recommended during the early years of life.8 Characterization of the genetic and molecular features of patients who present with hepatoblastoma might be useful in determining prognosis. Of genetic features, mutations in the CTNNB1 gene are the most common, but several genes in the Wnt pathway are also linked to hepatoblastoma formation.9

Along with the progress in subtyping patients by genetics, epigenetics, and molecular features, there is a growing appreciation for the heterogeneity of hepatoblastoma and the likelihood that treatment strategies can be better individualized to improve outcomes in high-risk patients. This progress is expected to accelerate further when results from the results from the Pediatric Hepatic International Tumor Trial (PHITT) are published. These data are expected to be available in 2025, and may help with prognostication and understanding the biology of hepatoblastoma in relation to outcomes.

Treatment Strategies in Hepatoblastoma

For low-grade hepatoblastoma, the first-line therapy is surgery, which can be sufficient for cure without relapse in selected patients with PRETEXT group 1 disease. Although only 40% to 60% of patients have resectable disease at diagnosis,10 there are several strategies to shrink tumor bulk, particularly chemotherapy due to the relatively high sensitivity of hepatoblastoma to cytotoxic therapies. The intensity of chemotherapy is increased relative to risk.11 For example, cisplatin-based regimens are considered for low-risk patients, while additional therapies, such as doxorubicin, irinotecan, or both, are added in patients at higher risk. Cure is common if these regimens permit a margin-free resection, although relapse does occur in a subset of patients.

If adequate debulking of the tumor cannot be achieved with conventional surgery, liver transplantation is typically offered for patients without extrahepatic disease or after distant metastases have been successfully excised. With liver transplantation and combination therapies to inhibit relapse associated with seeding, long-term survival rates of 80% have been reported.3 Judicious use of transplantation in patients with high-risk disease that raises the potential for relapse has been credited with rates of long-term survival that exceed 80% in some series. However, there is concern of offering transplantation when it is not necessary. In patients who are high risk with multiple lesions in the liver, there is a general agreement that transplantation reduces the likelihood of subsequent relapse; however, as the precision of aggressive resection coupled with effective chemotherapy has improved, there are more patients in whom the optimal choice might not be debated by experts.

Review articles typically cite the likelihood of an overall 5-year survival in patients with hepatoblastoma as being on the order of 80%.1 This rate includes children with late-onset disease, which is generally associated with a worse prognosis, and patients who eventually experience disease relapse. Survival rates are now likely to be substantially higher, with progress developing better treatment protocols for both groups. In the absence of high-risk features, long-term survival rates of 90% or higher are now being reported in some centers with high relative volumes of hepatoblastoma, regardless of baseline risks.

PHITT

The rarity of hepatoblastoma poses a significant challenge to conducting prospective studies with sufficient sample sizes to evaluate the overall efficacy of treatments and their effectiveness in patient subgroups based on specific clinical characteristics and disease severity. PHITT is the first international collaborative liver tumors trial to use a consensus approach. Centers in Europe, Japan, and the United States are participating through regional cancer study consortia. The Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, a leader in hepatoblastoma management in the United States, is anchoring this effort for the Children’s Oncology Group.

In addition to assessing treatment strategies in larger patient cohorts, PHITT is expanding the data available to correlate outcomes across different stages and risk categories based on histological and biological classifications. Hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma are being addressed in PHITT, but the design schema for these malignancies differs. For patients enrolled with hepatoblastoma, 4 risk groups have been defined, ranging from very low to high. Within these risk categories, flow charts provide guide selection of treatments based on clinical and disease features.

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center is one of the most active centers for the treatment of hepatoblastoma in the Unites States but manages only 15 to 20 cases of this rare disease per year. PHITT is expected to play a critical role in achieving a high level of valuable data, and the first sets of outcomes from this collaboration are anticipated to be available in early 2025. As the study progresses, meaningful data are expected for the most challenging and some of the rarest hepatoblastoma risk groups.

Summary

The rates of cure are now approaching 100% with surgery and chemotherapy in patients with localized or locally advanced hepatoblastoma. For more advanced, unresectable disease, liver transplantation is effective in most patients, providing high rates of long-term survival. For patients with relapsed disease, advanced treatment protocols at centers with high relative volumes

of hepatoblastoma are now regularly achieving a second remission—many of which are durable. Although prognosis is less favorable in patients who experience a second relapse, long-term survival is achieved even in a proportion of these children. Substantial rates of response and long-term survival have been common in hepatoblastoma diagnosed at early stages, but the recent progress in advanced hepatoblastoma is credited to more aggressive therapies based on a better understanding of the disease characteristics that allows for individualized therapy. There is hope that the larger pool of data becoming available in 2025 from PHITT will prove to be an additional source of information that guides further advances in managing this rare disease.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Koh KN, Namgoong JM, Yoon HM, et al. Recent improvement in survival outcomes and reappraisal of prognostic factors in hepatoblastoma. Cancer Med. 2021;10(10):3261-3273. doi:10.1002/cam4.3897

- Kahla JA, Siegel DA, Dai S, et al. Incidence and 5-year survival of children and adolescents with hepatoblastoma in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(10):e29763. doi:10.1002/pbc.29763

- Ramos-Gonzalez G, LaQuaglia M, O’Neill AF, et al. Long-term outcomes of liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: a single-center 14-year experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2018:e13250. doi:10.1111/petr.13250

- Zhou S, Malvar J, Chi YY, et al. Independent assessment of the Children’s Hepatic Tumors International Collaboration risk stratification for hepatoblastoma and the association of tumor histological characteristics with prognosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148013. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48013

- Feng J, Polychronidis G, Heger U, Frongia G, Mehrabi A, Hoffmann K. Incidence trends and survival prediction of hepatoblastoma in children: a population-based study. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2019;39(1):62. doi:10.1186/s40880-019-0411-7

- Sharma D, Subbarao G, Saxena R. Hepatoblastoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(2):192-200. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.015

- Heck JE, Meyers TJ, Lombardi C, et al. Case-control study of birth characteristics and the risk of hepatoblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(4):390-395. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2013.03.004

- Ranganathan S, Lopez-Terrada D, Alaggio R. Hepatoblastoma and pediatric hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2020;23(2):79-95. doi:10.1177/1093526619875228

- Curia MC, Zuckermann M, De Lellis L, et al. Sporadic childhood hepatoblastomas show activation of beta-catenin, mismatch repair defects and p53 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(1):7-14. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800977

- Fahy AS, Shaikh F, Gerstle JT. Multifocal hepatoblastoma: what is the risk of recurrent disease in the remnant liver? J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(5):1035-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.036

- Głowska-Ciemny J, Szymanski M, Kuszerska A, Rzepka R, von Kaisenberg CS, Kocyłowski R. Role of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in diagnosing childhood cancers and genetic-related chronic diseases. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(17):4302. doi:10.3390/cancers15174302

- Angelico R, Grimaldi C, Gazia C, et al. How do synchronous lung metastases influence the surgical management of children with hepatoblastoma? An update and systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(11):1693. doi:10.3390/cancers11111693

- Schooler GR, Infante JC, Acord M, et al. Imaging of pediatric liver tumors: A COG Diagnostic Imaging Committee/SPR Oncology Committee white paper. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70(suppl 4):e29965. doi:10.1002/pbc.29965

- Meyers RL, Maibach R, Hiyama E, et al. Risk-stratified staging in paediatric hepatoblastoma: a unified analysis from the Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):122-131. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30598-8

- Koh KN, Namgoong JM, Yoon HM, et al. Recent improvement in survival outcomes and reappraisal of prognostic factors in hepatoblastoma. Cancer Med. 2021;10(10):3261-3273. doi:10.1002/cam4.3897

- Kahla JA, Siegel DA, Dai S, et al. Incidence and 5-year survival of children and adolescents with hepatoblastoma in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(10):e29763. doi:10.1002/pbc.29763

- Ramos-Gonzalez G, LaQuaglia M, O’Neill AF, et al. Long-term outcomes of liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: a single-center 14-year experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2018:e13250. doi:10.1111/petr.13250

- Zhou S, Malvar J, Chi YY, et al. Independent assessment of the Children’s Hepatic Tumors International Collaboration risk stratification for hepatoblastoma and the association of tumor histological characteristics with prognosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2148013. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48013

- Feng J, Polychronidis G, Heger U, Frongia G, Mehrabi A, Hoffmann K. Incidence trends and survival prediction of hepatoblastoma in children: a population-based study. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2019;39(1):62. doi:10.1186/s40880-019-0411-7

- Sharma D, Subbarao G, Saxena R. Hepatoblastoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(2):192-200. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.015

- Heck JE, Meyers TJ, Lombardi C, et al. Case-control study of birth characteristics and the risk of hepatoblastoma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37(4):390-395. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2013.03.004

- Ranganathan S, Lopez-Terrada D, Alaggio R. Hepatoblastoma and pediatric hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2020;23(2):79-95. doi:10.1177/1093526619875228

- Curia MC, Zuckermann M, De Lellis L, et al. Sporadic childhood hepatoblastomas show activation of beta-catenin, mismatch repair defects and p53 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(1):7-14. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800977

- Fahy AS, Shaikh F, Gerstle JT. Multifocal hepatoblastoma: what is the risk of recurrent disease in the remnant liver? J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(5):1035-1040. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.036

- Głowska-Ciemny J, Szymanski M, Kuszerska A, Rzepka R, von Kaisenberg CS, Kocyłowski R. Role of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) in diagnosing childhood cancers and genetic-related chronic diseases. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(17):4302. doi:10.3390/cancers15174302

- Angelico R, Grimaldi C, Gazia C, et al. How do synchronous lung metastases influence the surgical management of children with hepatoblastoma? An update and systematic review of the literature. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(11):1693. doi:10.3390/cancers11111693

- Schooler GR, Infante JC, Acord M, et al. Imaging of pediatric liver tumors: A COG Diagnostic Imaging Committee/SPR Oncology Committee white paper. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023;70(suppl 4):e29965. doi:10.1002/pbc.29965

- Meyers RL, Maibach R, Hiyama E, et al. Risk-stratified staging in paediatric hepatoblastoma: a unified analysis from the Children’s Hepatic tumors International Collaboration. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):122-131. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30598-8

Improving Prognosis in Hepatoblastoma: Evolving Risk Stratification and Treatment Strategies

Improving Prognosis in Hepatoblastoma: Evolving Risk Stratification and Treatment Strategies

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors

How do you assess a patient’s prognosis at the time that they are diagnosed with myelofibrosis?

In the clinic, we use several scoring systems that have been developed based on the outcomes of hundreds of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to try to predict survival from time of diagnosis. Disease features associated with a poor prognosis include anemia, elevated white blood cell count, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, and increased peripheral blasts. Some of these scoring systems also incorporate chromosomal abnormalities as well as gene mutations to further refine prognostication.1

Determining prognosis can be important to creating a treatment plan, particularly to decide if curative allogeneic stem cell transplantation is necessary. However, I always caution patients that these prognostic scoring systems cannot tell the future and that each patient may respond differently to treatment.

How do you monitor for disease progression?

I will discuss with patients how they are feeling in order to determine if there are any new or developing symptoms that could be a sign that their disease is progressing. I will also review their laboratory work looking for changes in blood counts that could be a signal of disease evolution.

For instance, development of anemia or thrombocytopenia may signal worsening bone marrow function or progression to secondary acute leukemia. If there are concerning signs or symptoms, I will then perform a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate that will include assessment of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities to determine if their disease is progressing.

What are the first-line treatment options for a patient newly diagnosed with myelofibrosis, and how do you determine the best course of action?

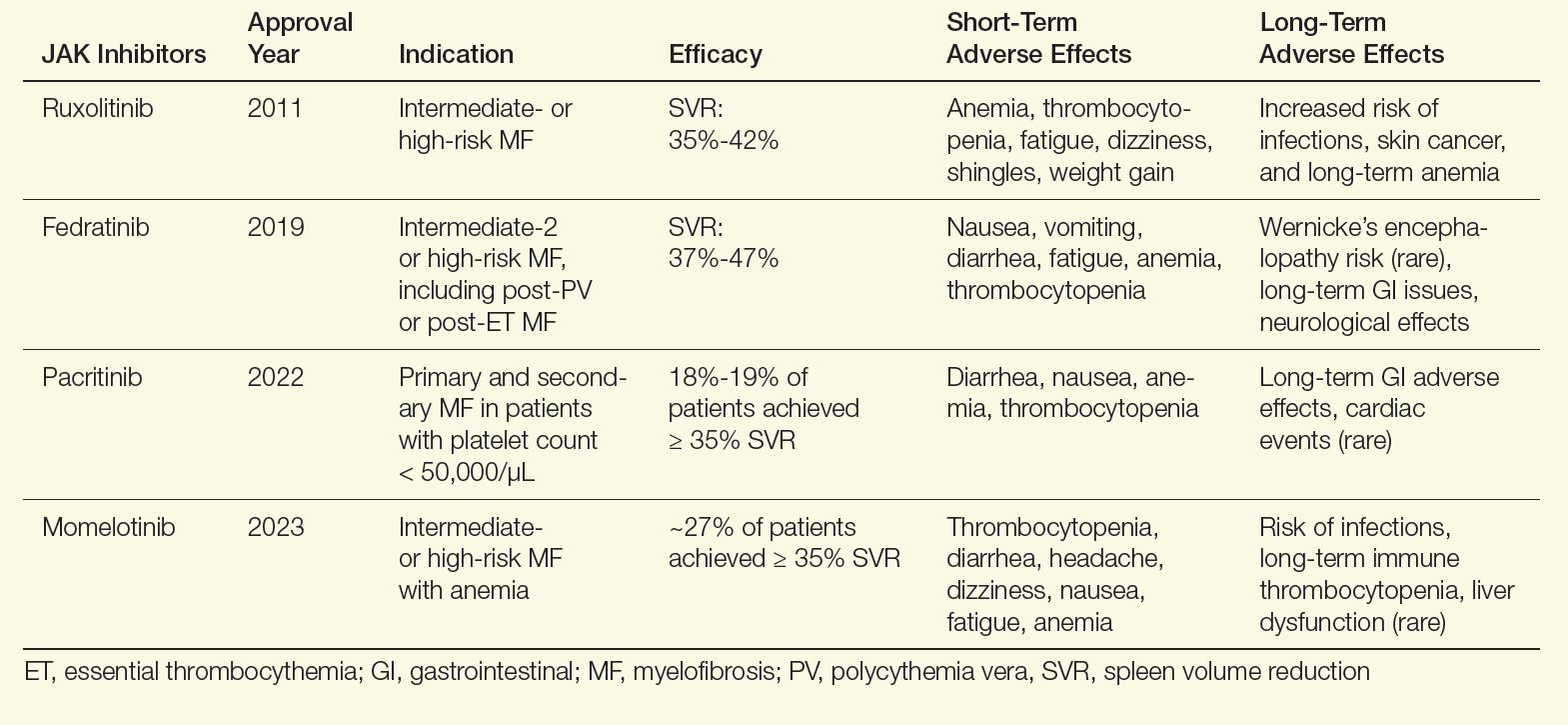

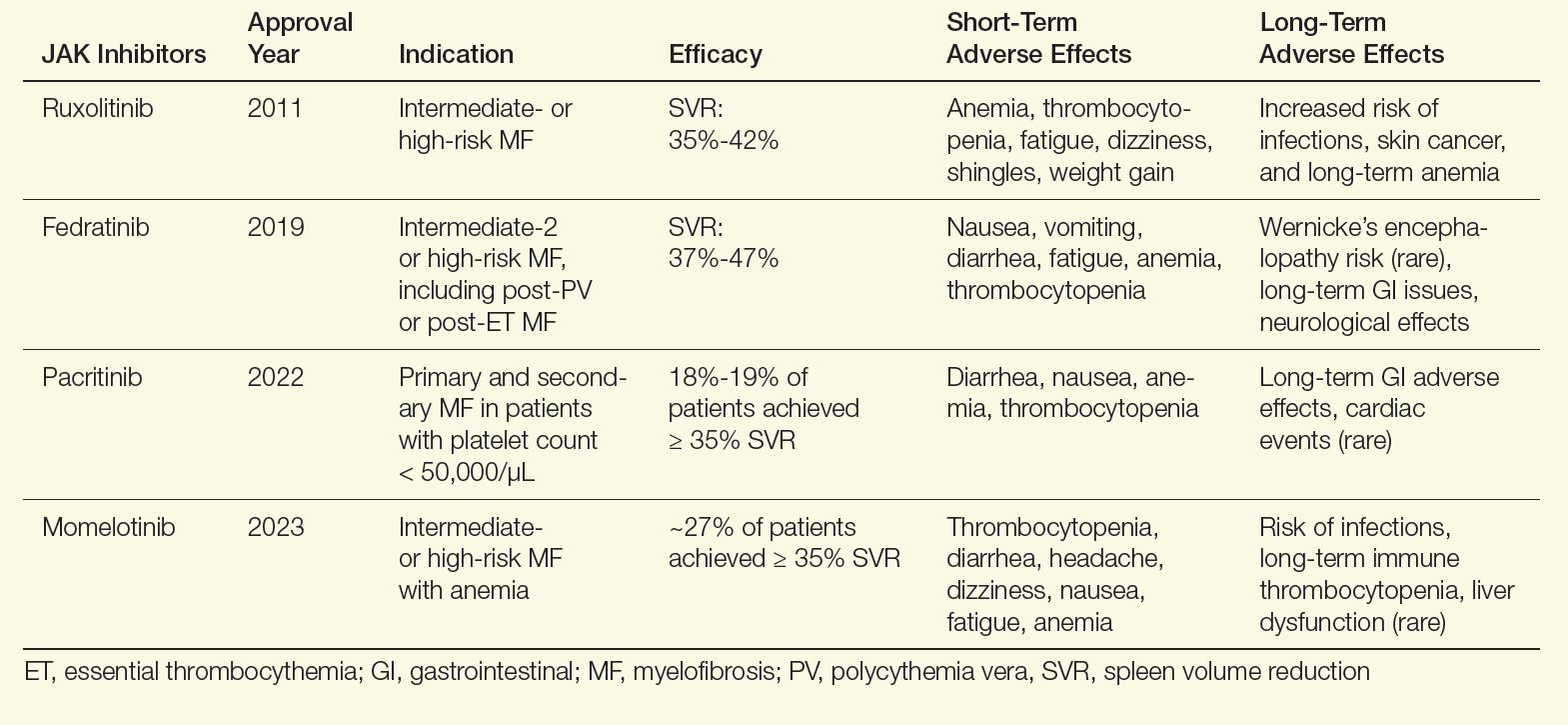

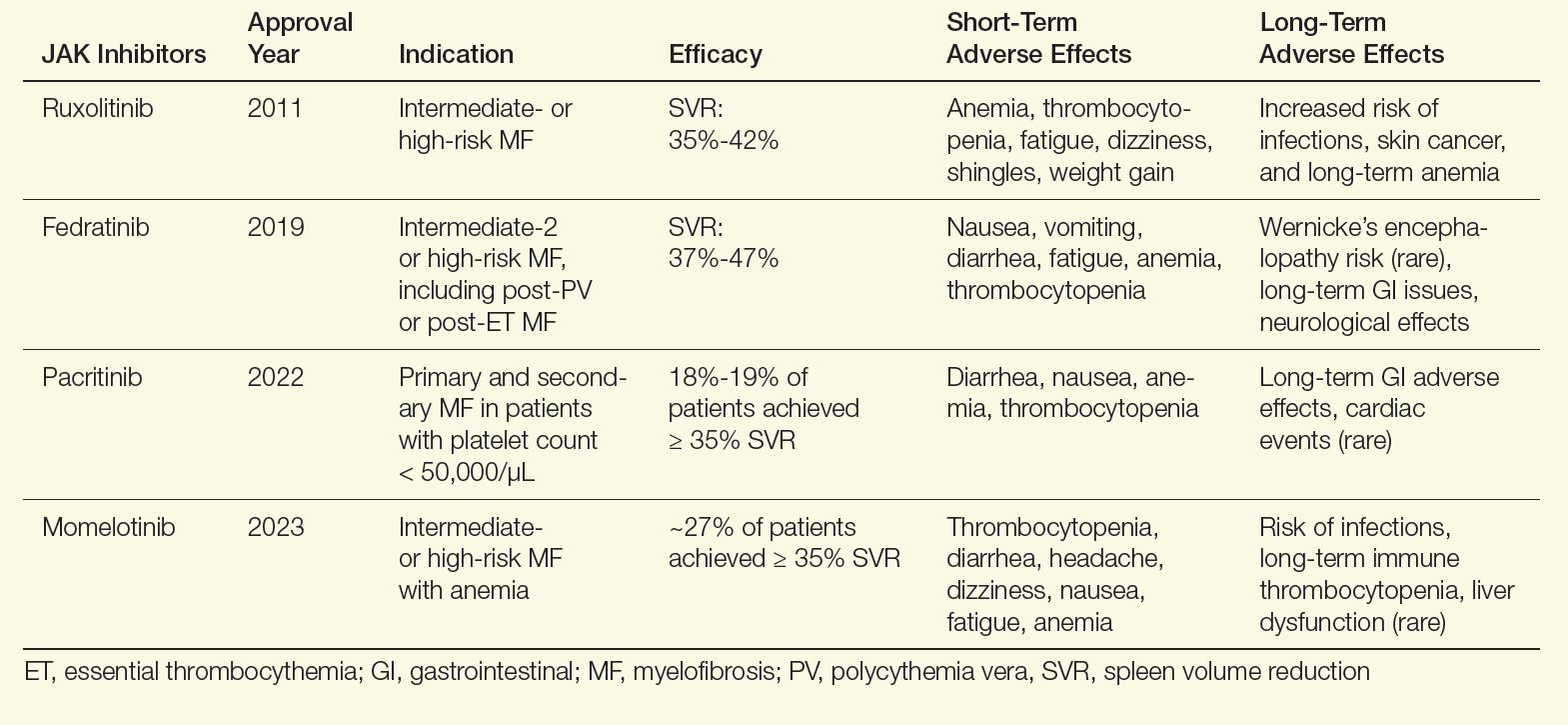

For patients with myelofibrosis, the first-line treatment options include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which are effective at improving spleen size and reducing symptom burden. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 4 JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myelofibrosis: ruxolitinib, fedratinib, pacritinib, and momelotinib (Table).2-13 In general, ruxolitinib is the first-line treatment option unless there is thrombocytopenia, in which case pacritinib is more appropriate. In patients with baseline anemia, momelotinib may be the best choice.

Table. FDA-Approved JAK Inhibitors for Myelofibrosis2-13

Although these agents are effective in reducing spleen size and improving symptoms, they do not affect disease progression. Therefore, I also evaluate all patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only curative modality. Appropriate patients are younger than age 75, with a low comorbidity burden and either intermediate-2 or high-risk disease. In addition, patients who do not respond to frontline JAK inhibitors should be considered for this approach. In patients who are transplant candidates, I will concurrently have them evaluated and start the process of finding a donor while initiating a JAK inhibitor.

What are the most common adverse effects of JAK inhibitors, and how do you help patients manage these issues?

There are short- and long-term effects of JAK inhibitors. Focusing on ruxolitinib, the most frequently used JAK inhibitor, patients can experience bruising, dizziness, and headaches, which generally resolves within a few weeks. Notable longer-term adverse events of ruxolitinib include increased rates of shingles infection, so I encourage my patients to get vaccinated for shingles before initiation.11 Weight gain has also been reported with ruxolitinib, but not with other JAK inhibitors.12,13 The other main adverse effect of ruxolitinib is worsening anemia and thrombocythemia, so I closely monitor blood counts during treatment.

What are some of the key reasons why patients may develop JAK inhibitor resistance or intolerance, and how do you address these problems in clinical practice?

There are a variety of reasons why patients discontinue a JAK inhibitor, but these can be lumped into 2 categories: (1) the medication has not achieved, or is no longer achieving, treatment goals, or (2) adverse effects from the JAK inhibitor require discontinuation. In a large series of patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with ruxolitinib, about 60% of discontinuations were because of JAK inhibitor refractoriness/resistance, and around 40% were from adverse events.14

Resistance can arise from several mechanisms, including activation of alternative pathways and clonal evolution that are ongoing regardless of JAK inhibition. In clinical practice, we are addressing JAK inhibitor resistance through clinical trials of novel therapies, particularly in combination with JAK inhibitors, which can potentially mitigate resistance. New JAK inhibitors are also being developed that may more effectively target the overactive JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and reduce resistance.

In terms of intolerance, there are many strategies to address nonhematological toxicities, and with the availability of pacritinib and momelotinib, patients in whom thrombocytopenia and anemia develop can be safely and effectively transitioned to an alternative JAK inhibitor if they experience adverse effects with ruxolitinib.

How do you incorporate patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-life measures into treatment planning?

Symptom assessment is a key component of the care for myelofibrosis. There are several well-validated patient-reported symptom assessment forms for myelofibrosis.15 These can be helpful both to quantify the burden of myelofibrosis-related symptoms, as well as to track progress of these symptoms over time. I generally incorporate these assessments into the initial evaluation and several times throughout therapy.

However, many symptoms are not captured on these assessments, and so I spend considerable time speaking to patients about how they are feeling and tracking their symptoms carefully over time. I also find it helpful to assess how a patient feels during treatment using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) questionnaire, which is a 7-point scale reflecting overall improvement compared with baseline.

Can you share any strategies for helping patients navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of living with a chronic disease like myelofibrosis?

In my experience, addressing emotional and psychological stress is one of the greatest challenges in caring for patients with myelofibrosis. Myelofibrosis significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and productivity.16 Some strategies that my patients have found helpful include engaging with the patient community and learning from others who have been living with this disease for years.

Anecdotally, I find that patients who exercise regularly and maintain an active lifestyle benefit psychologically. I have also observed that involving a support system is critical for dealing with the emotional stress of living with a chronic disease. It is particularly helpful if the patient brings a supportive friend or family member to appointments, as they can help the patient process the information discussed.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310-318. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886

- Jakafi [package insert]. Incyte Corporation; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Inrebic for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. FDA announcement. August 16, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approvesfedratinib-myelofibrosis

- Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Masszi T, et al. Updated results of the placebo-controlled, phase III JAKARTA trial of fedratinib in patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):244-248. doi:10.1111/bjh.17727

- Vonjo [package insert]. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225-e236. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3

- Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818

- Ojjaara [package insert]. GSK; 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216873s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844-3850. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418

- Lussana F, Cattaneo M, Rambaldi A, Squizzato A. Ruxolitinib-associated infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):339-347. doi:10.1002/ajh.24976

- Sapre M, Tremblay D, Wilck E, et al. Metabolic effects of JAK1/2 inhibition in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16609. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53056-x

- Tremblay D, Cavalli L, Sy O, Rose S, Mascarenhas J. The effect of fedratinib, a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(7):e463-e466. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.01.003

- Palandri F, Breccia M, Bonifacio M, et al. Life after ruxolitinib: reasons for discontinuation, impact of disease phase, and outcomes in 218 patients with myelofibrosis. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1243-1252. doi:10.1002/cncr.32664

- Tremblay D, Mesa R. Addressing symptom burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35(2):101372. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2022.101372

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653-1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y

How do you assess a patient’s prognosis at the time that they are diagnosed with myelofibrosis?

In the clinic, we use several scoring systems that have been developed based on the outcomes of hundreds of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to try to predict survival from time of diagnosis. Disease features associated with a poor prognosis include anemia, elevated white blood cell count, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, and increased peripheral blasts. Some of these scoring systems also incorporate chromosomal abnormalities as well as gene mutations to further refine prognostication.1

Determining prognosis can be important to creating a treatment plan, particularly to decide if curative allogeneic stem cell transplantation is necessary. However, I always caution patients that these prognostic scoring systems cannot tell the future and that each patient may respond differently to treatment.

How do you monitor for disease progression?

I will discuss with patients how they are feeling in order to determine if there are any new or developing symptoms that could be a sign that their disease is progressing. I will also review their laboratory work looking for changes in blood counts that could be a signal of disease evolution.

For instance, development of anemia or thrombocytopenia may signal worsening bone marrow function or progression to secondary acute leukemia. If there are concerning signs or symptoms, I will then perform a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate that will include assessment of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities to determine if their disease is progressing.

What are the first-line treatment options for a patient newly diagnosed with myelofibrosis, and how do you determine the best course of action?

For patients with myelofibrosis, the first-line treatment options include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which are effective at improving spleen size and reducing symptom burden. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 4 JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myelofibrosis: ruxolitinib, fedratinib, pacritinib, and momelotinib (Table).2-13 In general, ruxolitinib is the first-line treatment option unless there is thrombocytopenia, in which case pacritinib is more appropriate. In patients with baseline anemia, momelotinib may be the best choice.

Table. FDA-Approved JAK Inhibitors for Myelofibrosis2-13

Although these agents are effective in reducing spleen size and improving symptoms, they do not affect disease progression. Therefore, I also evaluate all patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only curative modality. Appropriate patients are younger than age 75, with a low comorbidity burden and either intermediate-2 or high-risk disease. In addition, patients who do not respond to frontline JAK inhibitors should be considered for this approach. In patients who are transplant candidates, I will concurrently have them evaluated and start the process of finding a donor while initiating a JAK inhibitor.

What are the most common adverse effects of JAK inhibitors, and how do you help patients manage these issues?

There are short- and long-term effects of JAK inhibitors. Focusing on ruxolitinib, the most frequently used JAK inhibitor, patients can experience bruising, dizziness, and headaches, which generally resolves within a few weeks. Notable longer-term adverse events of ruxolitinib include increased rates of shingles infection, so I encourage my patients to get vaccinated for shingles before initiation.11 Weight gain has also been reported with ruxolitinib, but not with other JAK inhibitors.12,13 The other main adverse effect of ruxolitinib is worsening anemia and thrombocythemia, so I closely monitor blood counts during treatment.

What are some of the key reasons why patients may develop JAK inhibitor resistance or intolerance, and how do you address these problems in clinical practice?

There are a variety of reasons why patients discontinue a JAK inhibitor, but these can be lumped into 2 categories: (1) the medication has not achieved, or is no longer achieving, treatment goals, or (2) adverse effects from the JAK inhibitor require discontinuation. In a large series of patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with ruxolitinib, about 60% of discontinuations were because of JAK inhibitor refractoriness/resistance, and around 40% were from adverse events.14

Resistance can arise from several mechanisms, including activation of alternative pathways and clonal evolution that are ongoing regardless of JAK inhibition. In clinical practice, we are addressing JAK inhibitor resistance through clinical trials of novel therapies, particularly in combination with JAK inhibitors, which can potentially mitigate resistance. New JAK inhibitors are also being developed that may more effectively target the overactive JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and reduce resistance.

In terms of intolerance, there are many strategies to address nonhematological toxicities, and with the availability of pacritinib and momelotinib, patients in whom thrombocytopenia and anemia develop can be safely and effectively transitioned to an alternative JAK inhibitor if they experience adverse effects with ruxolitinib.

How do you incorporate patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-life measures into treatment planning?

Symptom assessment is a key component of the care for myelofibrosis. There are several well-validated patient-reported symptom assessment forms for myelofibrosis.15 These can be helpful both to quantify the burden of myelofibrosis-related symptoms, as well as to track progress of these symptoms over time. I generally incorporate these assessments into the initial evaluation and several times throughout therapy.

However, many symptoms are not captured on these assessments, and so I spend considerable time speaking to patients about how they are feeling and tracking their symptoms carefully over time. I also find it helpful to assess how a patient feels during treatment using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) questionnaire, which is a 7-point scale reflecting overall improvement compared with baseline.

Can you share any strategies for helping patients navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of living with a chronic disease like myelofibrosis?

In my experience, addressing emotional and psychological stress is one of the greatest challenges in caring for patients with myelofibrosis. Myelofibrosis significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and productivity.16 Some strategies that my patients have found helpful include engaging with the patient community and learning from others who have been living with this disease for years.

Anecdotally, I find that patients who exercise regularly and maintain an active lifestyle benefit psychologically. I have also observed that involving a support system is critical for dealing with the emotional stress of living with a chronic disease. It is particularly helpful if the patient brings a supportive friend or family member to appointments, as they can help the patient process the information discussed.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

How do you assess a patient’s prognosis at the time that they are diagnosed with myelofibrosis?

In the clinic, we use several scoring systems that have been developed based on the outcomes of hundreds of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to try to predict survival from time of diagnosis. Disease features associated with a poor prognosis include anemia, elevated white blood cell count, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, and increased peripheral blasts. Some of these scoring systems also incorporate chromosomal abnormalities as well as gene mutations to further refine prognostication.1

Determining prognosis can be important to creating a treatment plan, particularly to decide if curative allogeneic stem cell transplantation is necessary. However, I always caution patients that these prognostic scoring systems cannot tell the future and that each patient may respond differently to treatment.

How do you monitor for disease progression?

I will discuss with patients how they are feeling in order to determine if there are any new or developing symptoms that could be a sign that their disease is progressing. I will also review their laboratory work looking for changes in blood counts that could be a signal of disease evolution.

For instance, development of anemia or thrombocytopenia may signal worsening bone marrow function or progression to secondary acute leukemia. If there are concerning signs or symptoms, I will then perform a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate that will include assessment of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities to determine if their disease is progressing.

What are the first-line treatment options for a patient newly diagnosed with myelofibrosis, and how do you determine the best course of action?

For patients with myelofibrosis, the first-line treatment options include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which are effective at improving spleen size and reducing symptom burden. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 4 JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myelofibrosis: ruxolitinib, fedratinib, pacritinib, and momelotinib (Table).2-13 In general, ruxolitinib is the first-line treatment option unless there is thrombocytopenia, in which case pacritinib is more appropriate. In patients with baseline anemia, momelotinib may be the best choice.

Table. FDA-Approved JAK Inhibitors for Myelofibrosis2-13

Although these agents are effective in reducing spleen size and improving symptoms, they do not affect disease progression. Therefore, I also evaluate all patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only curative modality. Appropriate patients are younger than age 75, with a low comorbidity burden and either intermediate-2 or high-risk disease. In addition, patients who do not respond to frontline JAK inhibitors should be considered for this approach. In patients who are transplant candidates, I will concurrently have them evaluated and start the process of finding a donor while initiating a JAK inhibitor.

What are the most common adverse effects of JAK inhibitors, and how do you help patients manage these issues?

There are short- and long-term effects of JAK inhibitors. Focusing on ruxolitinib, the most frequently used JAK inhibitor, patients can experience bruising, dizziness, and headaches, which generally resolves within a few weeks. Notable longer-term adverse events of ruxolitinib include increased rates of shingles infection, so I encourage my patients to get vaccinated for shingles before initiation.11 Weight gain has also been reported with ruxolitinib, but not with other JAK inhibitors.12,13 The other main adverse effect of ruxolitinib is worsening anemia and thrombocythemia, so I closely monitor blood counts during treatment.

What are some of the key reasons why patients may develop JAK inhibitor resistance or intolerance, and how do you address these problems in clinical practice?

There are a variety of reasons why patients discontinue a JAK inhibitor, but these can be lumped into 2 categories: (1) the medication has not achieved, or is no longer achieving, treatment goals, or (2) adverse effects from the JAK inhibitor require discontinuation. In a large series of patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with ruxolitinib, about 60% of discontinuations were because of JAK inhibitor refractoriness/resistance, and around 40% were from adverse events.14

Resistance can arise from several mechanisms, including activation of alternative pathways and clonal evolution that are ongoing regardless of JAK inhibition. In clinical practice, we are addressing JAK inhibitor resistance through clinical trials of novel therapies, particularly in combination with JAK inhibitors, which can potentially mitigate resistance. New JAK inhibitors are also being developed that may more effectively target the overactive JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and reduce resistance.

In terms of intolerance, there are many strategies to address nonhematological toxicities, and with the availability of pacritinib and momelotinib, patients in whom thrombocytopenia and anemia develop can be safely and effectively transitioned to an alternative JAK inhibitor if they experience adverse effects with ruxolitinib.

How do you incorporate patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-life measures into treatment planning?

Symptom assessment is a key component of the care for myelofibrosis. There are several well-validated patient-reported symptom assessment forms for myelofibrosis.15 These can be helpful both to quantify the burden of myelofibrosis-related symptoms, as well as to track progress of these symptoms over time. I generally incorporate these assessments into the initial evaluation and several times throughout therapy.

However, many symptoms are not captured on these assessments, and so I spend considerable time speaking to patients about how they are feeling and tracking their symptoms carefully over time. I also find it helpful to assess how a patient feels during treatment using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) questionnaire, which is a 7-point scale reflecting overall improvement compared with baseline.

Can you share any strategies for helping patients navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of living with a chronic disease like myelofibrosis?

In my experience, addressing emotional and psychological stress is one of the greatest challenges in caring for patients with myelofibrosis. Myelofibrosis significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and productivity.16 Some strategies that my patients have found helpful include engaging with the patient community and learning from others who have been living with this disease for years.

Anecdotally, I find that patients who exercise regularly and maintain an active lifestyle benefit psychologically. I have also observed that involving a support system is critical for dealing with the emotional stress of living with a chronic disease. It is particularly helpful if the patient brings a supportive friend or family member to appointments, as they can help the patient process the information discussed.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310-318. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886

- Jakafi [package insert]. Incyte Corporation; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Inrebic for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. FDA announcement. August 16, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approvesfedratinib-myelofibrosis

- Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Masszi T, et al. Updated results of the placebo-controlled, phase III JAKARTA trial of fedratinib in patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):244-248. doi:10.1111/bjh.17727

- Vonjo [package insert]. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225-e236. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3

- Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818

- Ojjaara [package insert]. GSK; 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216873s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844-3850. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418

- Lussana F, Cattaneo M, Rambaldi A, Squizzato A. Ruxolitinib-associated infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):339-347. doi:10.1002/ajh.24976

- Sapre M, Tremblay D, Wilck E, et al. Metabolic effects of JAK1/2 inhibition in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16609. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53056-x

- Tremblay D, Cavalli L, Sy O, Rose S, Mascarenhas J. The effect of fedratinib, a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(7):e463-e466. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.01.003

- Palandri F, Breccia M, Bonifacio M, et al. Life after ruxolitinib: reasons for discontinuation, impact of disease phase, and outcomes in 218 patients with myelofibrosis. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1243-1252. doi:10.1002/cncr.32664

- Tremblay D, Mesa R. Addressing symptom burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35(2):101372. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2022.101372

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653-1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y

- Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310-318. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886

- Jakafi [package insert]. Incyte Corporation; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Inrebic for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. FDA announcement. August 16, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approvesfedratinib-myelofibrosis

- Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Masszi T, et al. Updated results of the placebo-controlled, phase III JAKARTA trial of fedratinib in patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):244-248. doi:10.1111/bjh.17727

- Vonjo [package insert]. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225-e236. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3

- Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818

- Ojjaara [package insert]. GSK; 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216873s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844-3850. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418

- Lussana F, Cattaneo M, Rambaldi A, Squizzato A. Ruxolitinib-associated infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):339-347. doi:10.1002/ajh.24976

- Sapre M, Tremblay D, Wilck E, et al. Metabolic effects of JAK1/2 inhibition in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16609. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53056-x

- Tremblay D, Cavalli L, Sy O, Rose S, Mascarenhas J. The effect of fedratinib, a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(7):e463-e466. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.01.003

- Palandri F, Breccia M, Bonifacio M, et al. Life after ruxolitinib: reasons for discontinuation, impact of disease phase, and outcomes in 218 patients with myelofibrosis. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1243-1252. doi:10.1002/cncr.32664

- Tremblay D, Mesa R. Addressing symptom burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35(2):101372. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2022.101372

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653-1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors

Project’s Improvement in JIA Outcome Disparities Sets Stage for Further Interventions

WASHINGTON — A quality improvement project aimed at reducing racial disparities in juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) led to a modest reduction in the overall clinical Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score (cJADAS) and a 17% reduction in the disparity gap between Black and White patients, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our work has led to initial progress in all groups, but we did not fully close the gap in outcomes,” Dori Abel, MD, MSHP, an attending rheumatologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, told attendees. But the project still revealed that it’s feasible to improve outcomes and reduce disparities with a “multipronged, equity-driven approach,” she said. “Stratifying data by demographic variables can reveal important differences in health care delivery and outcomes, catalyzing improvement efforts.”

Giya Harry, MD, MPH, MSc, an associate professor of pediatric rheumatology at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, was not involved in the study but praised both the effort and the progress made.

“The results are promising and suggest that with additional interventions targeting other key drivers, the team may be successful in completely eliminating the disparity in outcomes,” Harry said in an interview. “I applaud the hard work of Dr Abel and the other members of the team for doing the important work of characterizing the very complex issue of disparities in JIA outcomes across different race groups.”

It will now be important to build upon what the physicians learned during this process, said Harry, also the chair of the Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility committee of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance.

“Patience is needed as they cycle through interventions with an emphasis on other key drivers” of disparities, Harry said.

Targeting Factors That Clinicians Can Potentially Influence

In her presentation, Abel discussed the various barriers that interfere with patients’ ability to move up the “JIA escalator” of getting referred and diagnosed, starting treatment and getting control of the disease, and monitoring and managing the disease and flares. These barriers include difficulties with access, trust, finances, insurance, caregivers’ missed work, medication burden, side effects, system barriers, and exhaustion and depression among caregivers and patients.

These barriers then contribute to disparities in JIA outcomes. In the STOP-JIA study, for example, Black children had greater polyarthritis disease activity in the first year and greater odds of radiographic damage, Abel noted. At her own institution, despite a mean cJADAS of 2.9 for the whole population of patients with JIA, the average was 5.0 for non-Hispanic Black patients, compared with 2.6 for non-Hispanic White patients.

The team therefore developed and implemented a quality improvement initiative aimed at improving the overall mean cJADAS and narrowing the gap between Black and White patients. The goal was to reduce the mean cJADAS to 2.7 by July 2024 and simultaneously reduce the cJADAS in Black patients by 1.2 units, or 50% of the baseline disparity gap, without increasing the existing gap.

The team first explored the many overlapping and interacting drivers of disparities within the realms of community characteristics, JIA treatment course, patient/family characteristics, organizational infrastructure, divisional infrastructure, and provider characteristics. While many of the individual factors driving disparities are outside clinicians’ control, “there are some domains clinicians may be able to directly influence, such as provider characteristics, JIA treatment course, and possibly divisional infrastructure,” Harry noted, and the team appeared to choose goals that fell under domains within clinicians’ potential influence.

The research team focused their efforts on four areas: Consistent outcome documentation, application of JIA best practices, providing access to at-risk patients, and team awareness and agency.

As part of improving consistent outcome documentation, they integrated outcome metrics into data visualization tools so that gaps were more evident. Applying JIA best practices included standardizing their approach to assessing medication adherence and barriers, with changes to the JIA note templates in the electronic health record and updates to medication adherence handouts.