User login

Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis

From the Division of Rheumatology & Immunology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, NE.

Abstract

- Objective: To review cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

- Methods: Literature review of the assessment of CVD risk in RA.

- Results: CVD is the leading cause of death among RA patients.

Because of the increased risk of CVD events and CVD mortality in patients with RA, regular assessment of CVD risk and aggressive management of CVD risk in these patients is crucial. CVD risk estimation typically centers on the use of well-established CVD risk calculators. Most CVD risk scores from the general population do not contain RA-related factors predictive of CVD but have had more extensive performance testing, while novel RA-derived CVD risk scores that incorporate RA-related factors have had limited external validity testing. Neither set of risk scores incorporates novel imaging modalities or serum biomarkers, which are most likely to be helpful among individuals at intermediate risk. - Conclusion: Primary care and rheumatology providers must be aware of the increased risk of CVD in RA, a risk that approaches that of diabetic patients.

Routine assessment of CVD risk is an essential first step in minimizing CVD risk in this population. Until the performance of RA-specific CVD risk scores can be better established, we recommend the use of nationally endorsed CVD risk scores, with the frequency of reassessment based on CVD risk.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis; cardiovascular disease; cardiovascular risk assessment.

Editor’s note: This article is part 1 of a 2-part article. “Management of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis” was published in the March/April 2019 issue.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, autoimmune inflammatory arthritis affecting up to 1% of the US population that can lead to joint damage, functional disability, and reduced quality of life.1 In addition to articular involvement, systemic inflammation accompanying RA may lead to extra-articular manifestations and increase the risk of premature death.2 Cardiovascular disease (CVD), accounting for nearly half of all deaths among RA patients, is now recognized as a critical extra-articular manifestation of RA.2,3 As such, assessment and management of CVD risk is essential to the comprehensive care of the RA patient. This article reviews the approach to assessing CVD risk in patients with RA; the management of both traditional and RA-specific risk factors is discussed in a separate article.

Scope of the Problem

In a large meta-analysis of observational studies that included more than 111,000 patients with RA, CVD-related mortality rates were 1.5 times higher among RA patients than among general population controls.4 The risk of overall CVD, including nonfatal events, is similar; a separate meta-analysis of observational studies that included more than 41,000 patients with RA calculated a pooled relative risk for incident CVD of 1.48.5 Individual analyses identified heightened risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), cerebrovascular accident, and congestive heart failure (CHF).5 Perhaps more illustrative of the magnitude of the problem, the risk of CVD in RA approaches that observed among individuals with diabetes mellitus.6,7

Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounts for a significant portion of the CVD risk in RA, but its presentation may be atypical in RA patients. RA patients are at higher risk of suffering unrecognized myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden cardiac death.8 The reasons for silent ischemia in RA are not fully known, but have been hypothesized to include imbalances of inflammatory cytokines, alterations in pain sensitization, or the female predominance of RA (with women more often presenting with atypical symptoms of myocardial ischemia).9 Alarmingly, a retrospective chart review study reported that RA patients admitted for an acute MI were less likely to receive appropriate reperfusion therapy as well as secondary prevention with beta-blockers and lipid-lowering agents.10 Even with appropriate therapy, long-term outcomes such as mortality and recurrent ischemic events are more likely to occur in RA patients after acute MI.11-13

Independent of ischemic heart disease, RA patients are at increased risk of CHF.14-16 RA patients are at particular risk for CHF with preserved ejection fraction,17 which may be a result of systemic inflammation causing left ventricular stiffening.18,19 Similar to CAD, patients with RA are less likely to present with typical CHF symptoms, are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care, and have higher mortality rates following presentation with CHF.17

Although accounting for a lower proportion of the excess CVD morbidity and mortality in RA, the risk of noncardiac vascular disease is also increased in RA patients. Large meta-analyses have identified positive associations between RA with both ischemic (odds ratio [OR], 1.64 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.32-2.05]) and hemorrhagic (OR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.11-2.53]) stroke.20 Similarly, RA patients appear to have an approximately twofold higher risk of venous thromboembolic events.21 Less frequently studied than other forms of CVD, peripheral arterial disease may be increased in RA patients independent of other CVD and CVD risk factors.22,23

Assessing CVD Risk in RA

CVD Risk Scores

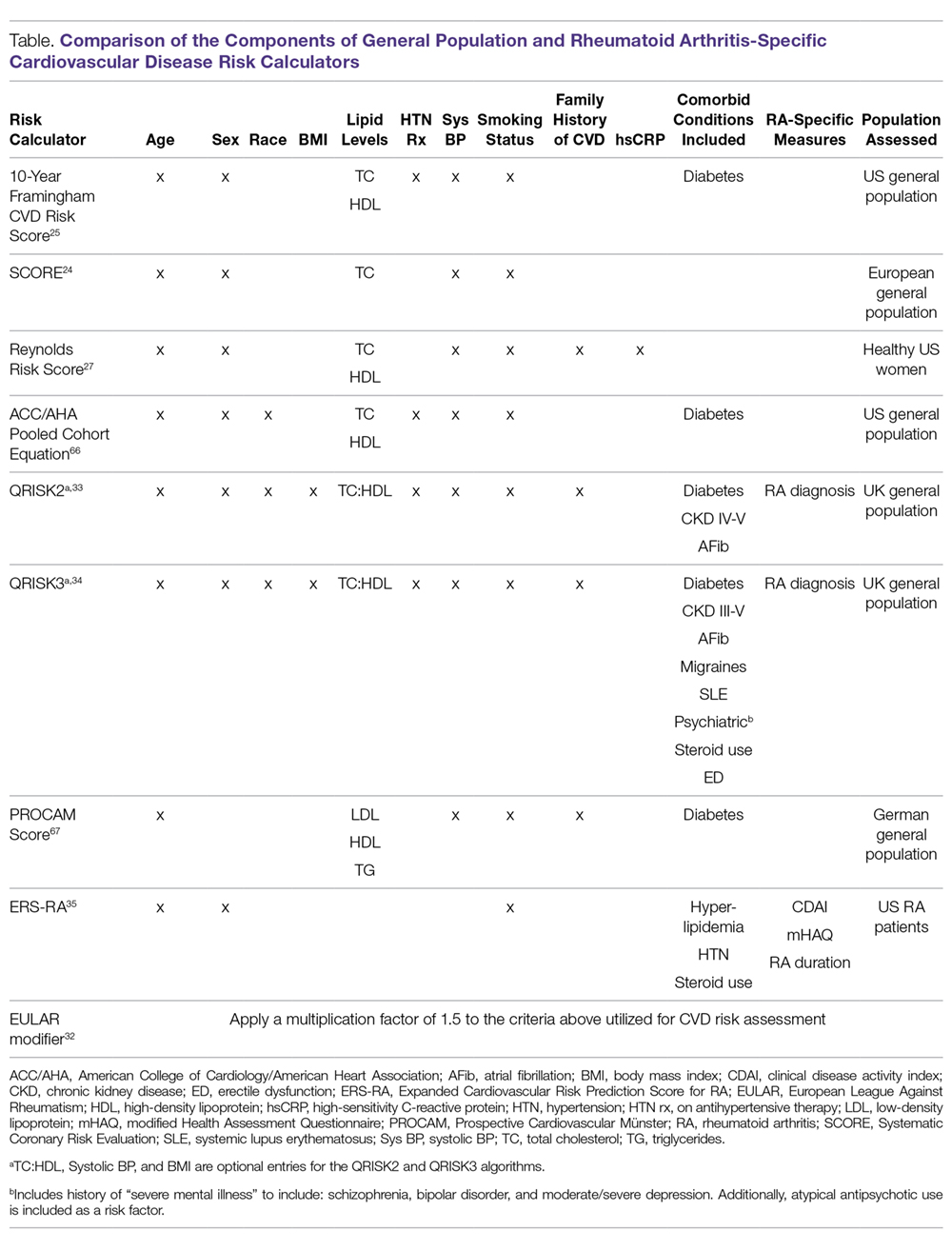

In order to identify patients who may benefit from primary prevention interventions, such as lipid-lowering therapy, CVD risk estimation typically centers on the use of well-established CVD risk calculators (Table). CVD risk scores such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS), Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE), and American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Pooled Cohort Equation incorporate traditional CVD risk factors, including age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, lipid levels, and presence of diabetes mellitus.24,25 However, CVD risk in RA patients appears to be inadequately explained by traditional CVD risk factors,26 with disease activity and inflammation being associated with higher CVD risk. Recognizing that inflammation may contribute to CVD risk even among non-RA patients, the Reynolds Risk Score includes high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) in its calculation.27 In contrast to more robust performance in the general population, these well-established CVD risk scores have had variable predictive potential of incident CVD in RA patients.28-30

Several models, or adaptations to existing models, have been proposed to improve CVD risk assessment in RA populations (Table). In 2009, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) task force suggested using a correction factor of 1.5 with traditional CVD risk models in RA patients with 2 of the following criteria: disease duration exceeding 10 years, rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody positivity, or extra-articular manifestations of RA.31 An update to these recommendations in 2015 continued to propose the use of a 1.5 correction factor, but suggested applying this to all RA patients.32 QRISK2, a modification to QRISK1 which was developed to predict CVD in the UK general population, includes the diagnosis of RA as a risk factor, and in early validation efforts more accurately discriminated patients in the general population at increased risk of CVD compared to the FRS.33 Additional disease-specific risk factors such as systemic lupus, steroid use, severe mental illness, and steroid and atypical antipsychotic use were incorporated in the QRISK3 algorithm, with model performance similar to the QRISK2.34 The Expanded Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Score for RA (ERS-RA) was specifically developed to assess CVD risk in RA patients by including RA disease activity, level of physical disability, RA disease duration, and prednisone use.35 Despite efforts to develop “RA-specific” risk scores, these have not consistently outperformed traditional CVD risk calculators.36-38 In one study involving more than 1700 RA patients, the ERS-RA performed similarly to the FRS and Reynolds Risk Score, with a net reclassification index of just 2.3% versus the FRS.36

Imaging Modalities

Imaging modalities may assist in characterizing the increased risk of CVD in RA and the subclinical CVD manifestations that occur. For example, RA patients were shown to have more prevalent and unstable coronary plaque, higher carotid intima media thickness, and impaired myocardial function with computed tomography (CT) angiography and carotid ultrasound.39,40 However, studies harnessing noninvasive imaging to augment CVD risk assessment in RA patients are limited.

Carotid ultrasound has been the most extensively studied imaging modality for CVD risk assessment in RA. In a cohort of 599 RA patients with no history of ACS, rates of ACS were nearly 4 times higher in RA patients with bilateral carotid plaque on carotid ultrasound, and the association with ACS was independent of other traditional and RA-related risk factors.41 Presence of bilateral carotid plaques was similarly associated with an increased risk of overall CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 3.34 [95% CI, 1.21-9.22]), ACS alone (HR, 6.31 [95% CI, 1.27-31.40]), and a lower mean CVD event-free survival (13.9 versus 15.2 years, P = 0.01) in a separate inception cohort of 105 RA patients with no prior history of CVD.42 The most useful application of carotid ultrasound may be in conjunction with clinical CVD risk models. Use of carotid ultrasound improved CVD risk stratification among RA patients who were considered at moderate risk by the EULAR-modified SCORE calculator.43 Beyond carotid ultrasound, measurement of arterial stiffness through ultrasound could also aid in CVD risk stratification. Aortic pulse wave velocity and augmentation index, measures of arterial stiffness, are predictive of CVD in the general population as well as RA patients and improve with reduction in RA disease activity.44,45 Peripheral arterial stiffness (brachial-ankle elasticity index) is impaired in RA patients and predictive of CVD morbidity and mortality in the general population.46,47

CT coronary angiography and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores are reliable measures of coronary artery atherosclerosis and have been validated for CVD risk assessment in the general population.48-52 While the association between RA and CT-related findings of atherosclerosis is well established, assessment of CT-mediated evaluation as a prognostic tool for CVD in RA is limited. In one cohort study, CAC predicted higher rates of CVD events in Chinese patients with RA and systemic lupus erythematosus in a pooled analysis, although results were limited by low event rates and the absence of RA-only subanalyses.53

While the aforementioned imaging modalities have focused on enhancing the identification of atherosclerosis, echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful for detecting subclinical structural and/or functional abnormalities that predispose to CHF. Structural abnormalities including increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are more prevalent in RA patients and predict incident CHF in the general population.54-56 MRI measures of myocardial inflammation, including T1 mapping and extracellular volume, are associated with higher mortality rates and also appear to be elevated in RA patients.57,58 Whether identification of these imaging findings influences the cost-effective clinical management of RA patients needs further study.

Biomarkers

Serum biomarkers, such as the anti-CCP antibody, have become crucial to the evaluation of patients suspected to have RA. With the growing understanding of the role pro-inflammatory mediators play in CVD pathogenesis and the relative ease with which they can be measured, serum biomarkers have potential to inform CVD risk assessment. In the general population, hsCRP concentrations are predictive of CVD and are included in the Reynolds Risk Score.27 In RA, CRP concentrations are typically much higher than those observed among individuals in the general population solely at increased CVD risk, yet elevated levels remain predictive of CVD death independent of RA disease activity and traditional CVD risk factors.59 Several additional cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules have been associated with surrogate markers of CVD in RA patients, although further study is needed to elucidate thresholds that signify increased CVD risk in a population characterized by the presence of systemic inflammation.60

Cardiac biomarkers used frequently in the general population may be useful to assess CVD risk in RA patients. N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) is a biomarker typically used to evaluate CHF severity, but it may also predict long-term mortality in patients with coronary heart disease.61,62 Circulating NT-pro BNP concentrations are elevated in RA independent of prevalent CHF and may serve as a useful tool to identify subclinical cardiac disease in RA patients.63 High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (HS-cTnI) assays are capable of detecting levels of cardiac troponin below the threshold typically used to diagnose ACS. HS-cTnI levels are increased in RA patients independent of additional CVD risk factors, and elevated levels (> 1.5 pg/mL) were associated with more severe CT angiography findings of coronary plaque as well as increased risk of CVD events.64,65

Clinical Application

A fully validated algorithm for CVD risk assessment in RA is lacking. Most CVD risk scores from the general population do not contain RA-related factors predictive of CVD but have had more extensive performance testing. In contrast, novel RA-derived CVD risk scores incorporate RA-related factors, but have had limited external validity testing. Additionally, RA-derived risk scores are less likely to be utilized and adopted by primary care providers and cardiologists involved in RA patients’ care. Neither set of risk scores incorporates novel imaging modalities or serum biomarkers, which are most likely to be helpful among individuals at intermediate risk. Therefore, until the performance of RA-specific CVD risk scores can be better established, we recommend the use of nationally endorsed CVD risk scores, with the frequency of reassessment based on CVD risk.

Conclusion

RA patients are at increased risk of CVD and CVD-related mortality relative to the general population. The disproportionate CVD burden seen in RA appears to be multifactorial, owing to the complex effects of systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and pro-atherogenic lipoprotein modifications. Additionally, many traditional CVD risk factors are more prevalent and suboptimally managed in RA patients. To mitigate the increased risk of CVD in RA, primary care and subspecialty providers alike must be aware of this heightened risk in RA, perform frequent assessment of CVD risk, and

Corresponding author: Bryant R. England, MD; 986270 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6270; Bryant.england@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. England is supported by UNMC Internal Medicine Scientist Development Award, UNMC Physician-Scientist Training Program, the UNMC Mentored Scholars Program, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. Dr. Mikuls is supported by a VA Merit Award (CX000896) and grants from the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54GM115458), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R25AA020818), and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2P50AR60772).

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the united states. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15-25.

2. England BR, Sayles H, Michaud K, et al. Cause-specific mortality in male US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:36-45.

3. Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S35-61.

4. Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690-1697.

5. Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1524-1529.

6. van Halm VP, Peters MJ, Voskuyl AE, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study, the CARRE investigation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1395-1400.

7. Peters MJ, van Halm VP, Voskuyl AE, et al. Does rheumatoid arthritis equal diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1571-1579.

8. Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:402-411.

9. Cardiovascular disease in women--often silent and fatal. Lancet. 2011;378:200,6736(11)61108-61112.

10. Van Doornum S, Brand C, Sundararajan V, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients receive less frequent acute reperfusion and secondary prevention therapy after myocardial infarction compared with the general population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R183.

11. Sodergren A, Stegmayr B, Lundberg V, et al. Increased incidence of and impaired prognosis after acute myocardial infarction among patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:263-266.

12. Douglas KM, Pace AV, Treharne GJ, et al. Excess recurrent cardiac events in rheumatoid arthritis patients with acute coronary syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:348-353.

13. McCoy SS, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. Long-term outcomes and treatment after myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:605-610.

14. Mantel A, Holmqvist M, Andersson DC, et al. Association between rheumatoid arthritis and risk of ischemic and nonischemic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1275-1285.

15. Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Kremers HM, et al. How much of the increased incidence of heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic heart disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3039-3044.

16. Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, et al. The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:412-420.

17. Davis JM,3rd, Roger VL, Crowson CS, et al. The presentation and outcome of heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis differs from that in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2603-2611.

18. Arslan S, Bozkurt E, Sari RA, Erol MK. Diastolic function abnormalities in active rheumatoid arthritis evaluation by conventional doppler and tissue doppler: Relation with duration of disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:294-299.

19. Liang KP, Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, et al. Increased prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1665-1670.

20. Wiseman SJ, Ralston SH, Wardlaw JM. Cerebrovascular disease in rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2016;47:943-950.

21. Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Spanuchart I, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:297-304.

22. Stamatelopoulos KS, Kitas GD, Papamichael CM, et al. Subclinical peripheral arterial disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:305-309.

23. Chuang YW, Yu MC, Lin CL, et al. Risk of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A nationwide population-based cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:439-445.

24. Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in europe: The SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987-1003.

25. D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117:743-753.

26. del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2737-2745.

27. Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: The Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297:611-619.

28. Arts EE, Popa C, Den Broeder AA, et al. Performance of four current risk algorithms in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:668-674.

29. Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Roger VL, et al. Usefulness of risk scores to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:420-424.

30. Kawai VK, Chung CP, Solus JF, et al. The ability of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cardiovascular risk score to identify rheumatoid arthritis patients with high coronary artery calcification scores. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:381-385.

31. Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:325-331.

32. Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:17-28.

33. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: Prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336:1475-1482.

34. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2099.

35. Solomon DH, Greenberg J, Curtis JR, et al. Derivation and internal validation of an expanded cardiovascular risk prediction score for rheumatoid arthritis: A consortium of rheumatology researchers of north america registry study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1995-2003.

36. Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Semb AG, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-specific cardiovascular risk scores are not superior to general risk scores: A validation analysis of patients from seven countries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1102-1110.

37. Alemao E, Cawston H, Bourhis F, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk algorithms in patients with vs without rheumatoid arthritis and the role of C-reactive protein in predicting cardiovascular outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:777-786.

38. Crowson CS, Rollefstad S, Kitas GD, et al. Challenges of developing a cardiovascular risk calculator for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2017;12: e0174656.

39. Karpouzas GA, Malpeso J, Choi TY, et al. Prevalence, extent and composition of coronary plaque in patients with rheumatoid arthritis without symptoms or prior diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1797-1804.

40. van Sijl AM, Peters MJ, Knol DK, et al. Carotid intima media thickness in rheumatoid arthritis as compared to control subjects: A meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;40:3893-97.

41. Evans MR, Escalante A, Battafarano DF, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis predicts incident acute coronary syndromes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1211-1220.

42. Ajeganova S, de Faire U, Jogestrand T, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis, disease measures, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, and atheroprotective natural antibodies for cardiovascular disease in early rheumatoid arthritis--an inception cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1146-1154.

43. Corrales A, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Peiro ME, et al. Carotid ultrasound is useful for the cardiovascular risk stratification of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:722-727.

44. Ikdahl E, Rollefstad S, Wibetoe G, et al. Predictive value of arterial stiffness and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis for cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1622-1630.

45. Provan SA, Semb AG, Hisdal J, et al. Remission is the goal for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:812-817.

46. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2012;60:556-562.

47. Ambrosino P, Tasso M, Lupoli R, et al. Non-invasive assessment of arterial stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of literature studies. Ann Med. 2015;47:457-467.

48. Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995;92:2157-2162.

49. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336-1345.

50. Task Force Members, Montalescot G, Sechtem U, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: The task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

51. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935-2959.

52. Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990-999.

53. Yiu KH, Mok MY, Wang S, et al. Prognostic role of coronary calcification in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:345-350.

54. Wright K, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular comorbidity in rheumatic diseases: A focus on heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10:339-352.

55. Rudominer RL, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, et al. Independent association of rheumatoid arthritis with increased left ventricular mass but not with reduced ejection fraction. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:22-29.

56. Bluemke DA, Kronmal RA, Lima JA, et al. The relationship of left ventricular mass and geometry to incident cardiovascular events: The MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2148-2155.

57. Ntusi NAB, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: Insights from CMR T1 mapping. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:526-536.

58. Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG, et al. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012;126:1206-1216.

59. Goodson NJ, Symmons DP, Scott DG, et al. Baseline levels of C-reactive protein and prediction of death from cardiovascular disease in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: A ten-year followup study of a primary care-based inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2293-2299.

60. Kozera L, Andrews J, Morgan AW. Cardiovascular risk and rheumatoid arthritis--the next step: Differentiating true soluble biomarkers of cardiovascular risk from surrogate measures of inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1944-1954.

61. Cardarelli R, Lumicao TG Jr. B-type natriuretic peptide: A review of its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic monitoring value in heart failure for primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:327-333.

62. Kragelund C, Gronning B, Kober L, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term mortality in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:666-675.

63. Harney SM, Timperley J, Daly C, et al. Brain natriuretic peptide is a potentially useful screening tool for the detection of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:136.

64. Bradham WS, Bian A, Oeser A, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin-I is elevated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, independent of cardiovascular risk factors and inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38930.

65. Karpouzas GA, Estis J, Rezaeian P, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I is a biomarker for occult coronary plaque burden and cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57:1080-1088.

66. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2889-2934.

67. Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation. 2002;105:310-315.

From the Division of Rheumatology & Immunology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, NE.

Abstract

- Objective: To review cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

- Methods: Literature review of the assessment of CVD risk in RA.

- Results: CVD is the leading cause of death among RA patients.

Because of the increased risk of CVD events and CVD mortality in patients with RA, regular assessment of CVD risk and aggressive management of CVD risk in these patients is crucial. CVD risk estimation typically centers on the use of well-established CVD risk calculators. Most CVD risk scores from the general population do not contain RA-related factors predictive of CVD but have had more extensive performance testing, while novel RA-derived CVD risk scores that incorporate RA-related factors have had limited external validity testing. Neither set of risk scores incorporates novel imaging modalities or serum biomarkers, which are most likely to be helpful among individuals at intermediate risk. - Conclusion: Primary care and rheumatology providers must be aware of the increased risk of CVD in RA, a risk that approaches that of diabetic patients.

Routine assessment of CVD risk is an essential first step in minimizing CVD risk in this population. Until the performance of RA-specific CVD risk scores can be better established, we recommend the use of nationally endorsed CVD risk scores, with the frequency of reassessment based on CVD risk.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis; cardiovascular disease; cardiovascular risk assessment.

Editor’s note: This article is part 1 of a 2-part article. “Management of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis” was published in the March/April 2019 issue.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, autoimmune inflammatory arthritis affecting up to 1% of the US population that can lead to joint damage, functional disability, and reduced quality of life.1 In addition to articular involvement, systemic inflammation accompanying RA may lead to extra-articular manifestations and increase the risk of premature death.2 Cardiovascular disease (CVD), accounting for nearly half of all deaths among RA patients, is now recognized as a critical extra-articular manifestation of RA.2,3 As such, assessment and management of CVD risk is essential to the comprehensive care of the RA patient. This article reviews the approach to assessing CVD risk in patients with RA; the management of both traditional and RA-specific risk factors is discussed in a separate article.

Scope of the Problem

In a large meta-analysis of observational studies that included more than 111,000 patients with RA, CVD-related mortality rates were 1.5 times higher among RA patients than among general population controls.4 The risk of overall CVD, including nonfatal events, is similar; a separate meta-analysis of observational studies that included more than 41,000 patients with RA calculated a pooled relative risk for incident CVD of 1.48.5 Individual analyses identified heightened risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), cerebrovascular accident, and congestive heart failure (CHF).5 Perhaps more illustrative of the magnitude of the problem, the risk of CVD in RA approaches that observed among individuals with diabetes mellitus.6,7

Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounts for a significant portion of the CVD risk in RA, but its presentation may be atypical in RA patients. RA patients are at higher risk of suffering unrecognized myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden cardiac death.8 The reasons for silent ischemia in RA are not fully known, but have been hypothesized to include imbalances of inflammatory cytokines, alterations in pain sensitization, or the female predominance of RA (with women more often presenting with atypical symptoms of myocardial ischemia).9 Alarmingly, a retrospective chart review study reported that RA patients admitted for an acute MI were less likely to receive appropriate reperfusion therapy as well as secondary prevention with beta-blockers and lipid-lowering agents.10 Even with appropriate therapy, long-term outcomes such as mortality and recurrent ischemic events are more likely to occur in RA patients after acute MI.11-13

Independent of ischemic heart disease, RA patients are at increased risk of CHF.14-16 RA patients are at particular risk for CHF with preserved ejection fraction,17 which may be a result of systemic inflammation causing left ventricular stiffening.18,19 Similar to CAD, patients with RA are less likely to present with typical CHF symptoms, are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care, and have higher mortality rates following presentation with CHF.17

Although accounting for a lower proportion of the excess CVD morbidity and mortality in RA, the risk of noncardiac vascular disease is also increased in RA patients. Large meta-analyses have identified positive associations between RA with both ischemic (odds ratio [OR], 1.64 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.32-2.05]) and hemorrhagic (OR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.11-2.53]) stroke.20 Similarly, RA patients appear to have an approximately twofold higher risk of venous thromboembolic events.21 Less frequently studied than other forms of CVD, peripheral arterial disease may be increased in RA patients independent of other CVD and CVD risk factors.22,23

Assessing CVD Risk in RA

CVD Risk Scores

In order to identify patients who may benefit from primary prevention interventions, such as lipid-lowering therapy, CVD risk estimation typically centers on the use of well-established CVD risk calculators (Table). CVD risk scores such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS), Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE), and American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Pooled Cohort Equation incorporate traditional CVD risk factors, including age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, lipid levels, and presence of diabetes mellitus.24,25 However, CVD risk in RA patients appears to be inadequately explained by traditional CVD risk factors,26 with disease activity and inflammation being associated with higher CVD risk. Recognizing that inflammation may contribute to CVD risk even among non-RA patients, the Reynolds Risk Score includes high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) in its calculation.27 In contrast to more robust performance in the general population, these well-established CVD risk scores have had variable predictive potential of incident CVD in RA patients.28-30

Several models, or adaptations to existing models, have been proposed to improve CVD risk assessment in RA populations (Table). In 2009, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) task force suggested using a correction factor of 1.5 with traditional CVD risk models in RA patients with 2 of the following criteria: disease duration exceeding 10 years, rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody positivity, or extra-articular manifestations of RA.31 An update to these recommendations in 2015 continued to propose the use of a 1.5 correction factor, but suggested applying this to all RA patients.32 QRISK2, a modification to QRISK1 which was developed to predict CVD in the UK general population, includes the diagnosis of RA as a risk factor, and in early validation efforts more accurately discriminated patients in the general population at increased risk of CVD compared to the FRS.33 Additional disease-specific risk factors such as systemic lupus, steroid use, severe mental illness, and steroid and atypical antipsychotic use were incorporated in the QRISK3 algorithm, with model performance similar to the QRISK2.34 The Expanded Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Score for RA (ERS-RA) was specifically developed to assess CVD risk in RA patients by including RA disease activity, level of physical disability, RA disease duration, and prednisone use.35 Despite efforts to develop “RA-specific” risk scores, these have not consistently outperformed traditional CVD risk calculators.36-38 In one study involving more than 1700 RA patients, the ERS-RA performed similarly to the FRS and Reynolds Risk Score, with a net reclassification index of just 2.3% versus the FRS.36

Imaging Modalities

Imaging modalities may assist in characterizing the increased risk of CVD in RA and the subclinical CVD manifestations that occur. For example, RA patients were shown to have more prevalent and unstable coronary plaque, higher carotid intima media thickness, and impaired myocardial function with computed tomography (CT) angiography and carotid ultrasound.39,40 However, studies harnessing noninvasive imaging to augment CVD risk assessment in RA patients are limited.

Carotid ultrasound has been the most extensively studied imaging modality for CVD risk assessment in RA. In a cohort of 599 RA patients with no history of ACS, rates of ACS were nearly 4 times higher in RA patients with bilateral carotid plaque on carotid ultrasound, and the association with ACS was independent of other traditional and RA-related risk factors.41 Presence of bilateral carotid plaques was similarly associated with an increased risk of overall CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 3.34 [95% CI, 1.21-9.22]), ACS alone (HR, 6.31 [95% CI, 1.27-31.40]), and a lower mean CVD event-free survival (13.9 versus 15.2 years, P = 0.01) in a separate inception cohort of 105 RA patients with no prior history of CVD.42 The most useful application of carotid ultrasound may be in conjunction with clinical CVD risk models. Use of carotid ultrasound improved CVD risk stratification among RA patients who were considered at moderate risk by the EULAR-modified SCORE calculator.43 Beyond carotid ultrasound, measurement of arterial stiffness through ultrasound could also aid in CVD risk stratification. Aortic pulse wave velocity and augmentation index, measures of arterial stiffness, are predictive of CVD in the general population as well as RA patients and improve with reduction in RA disease activity.44,45 Peripheral arterial stiffness (brachial-ankle elasticity index) is impaired in RA patients and predictive of CVD morbidity and mortality in the general population.46,47

CT coronary angiography and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores are reliable measures of coronary artery atherosclerosis and have been validated for CVD risk assessment in the general population.48-52 While the association between RA and CT-related findings of atherosclerosis is well established, assessment of CT-mediated evaluation as a prognostic tool for CVD in RA is limited. In one cohort study, CAC predicted higher rates of CVD events in Chinese patients with RA and systemic lupus erythematosus in a pooled analysis, although results were limited by low event rates and the absence of RA-only subanalyses.53

While the aforementioned imaging modalities have focused on enhancing the identification of atherosclerosis, echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful for detecting subclinical structural and/or functional abnormalities that predispose to CHF. Structural abnormalities including increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are more prevalent in RA patients and predict incident CHF in the general population.54-56 MRI measures of myocardial inflammation, including T1 mapping and extracellular volume, are associated with higher mortality rates and also appear to be elevated in RA patients.57,58 Whether identification of these imaging findings influences the cost-effective clinical management of RA patients needs further study.

Biomarkers

Serum biomarkers, such as the anti-CCP antibody, have become crucial to the evaluation of patients suspected to have RA. With the growing understanding of the role pro-inflammatory mediators play in CVD pathogenesis and the relative ease with which they can be measured, serum biomarkers have potential to inform CVD risk assessment. In the general population, hsCRP concentrations are predictive of CVD and are included in the Reynolds Risk Score.27 In RA, CRP concentrations are typically much higher than those observed among individuals in the general population solely at increased CVD risk, yet elevated levels remain predictive of CVD death independent of RA disease activity and traditional CVD risk factors.59 Several additional cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules have been associated with surrogate markers of CVD in RA patients, although further study is needed to elucidate thresholds that signify increased CVD risk in a population characterized by the presence of systemic inflammation.60

Cardiac biomarkers used frequently in the general population may be useful to assess CVD risk in RA patients. N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) is a biomarker typically used to evaluate CHF severity, but it may also predict long-term mortality in patients with coronary heart disease.61,62 Circulating NT-pro BNP concentrations are elevated in RA independent of prevalent CHF and may serve as a useful tool to identify subclinical cardiac disease in RA patients.63 High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (HS-cTnI) assays are capable of detecting levels of cardiac troponin below the threshold typically used to diagnose ACS. HS-cTnI levels are increased in RA patients independent of additional CVD risk factors, and elevated levels (> 1.5 pg/mL) were associated with more severe CT angiography findings of coronary plaque as well as increased risk of CVD events.64,65

Clinical Application

A fully validated algorithm for CVD risk assessment in RA is lacking. Most CVD risk scores from the general population do not contain RA-related factors predictive of CVD but have had more extensive performance testing. In contrast, novel RA-derived CVD risk scores incorporate RA-related factors, but have had limited external validity testing. Additionally, RA-derived risk scores are less likely to be utilized and adopted by primary care providers and cardiologists involved in RA patients’ care. Neither set of risk scores incorporates novel imaging modalities or serum biomarkers, which are most likely to be helpful among individuals at intermediate risk. Therefore, until the performance of RA-specific CVD risk scores can be better established, we recommend the use of nationally endorsed CVD risk scores, with the frequency of reassessment based on CVD risk.

Conclusion

RA patients are at increased risk of CVD and CVD-related mortality relative to the general population. The disproportionate CVD burden seen in RA appears to be multifactorial, owing to the complex effects of systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and pro-atherogenic lipoprotein modifications. Additionally, many traditional CVD risk factors are more prevalent and suboptimally managed in RA patients. To mitigate the increased risk of CVD in RA, primary care and subspecialty providers alike must be aware of this heightened risk in RA, perform frequent assessment of CVD risk, and

Corresponding author: Bryant R. England, MD; 986270 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6270; Bryant.england@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. England is supported by UNMC Internal Medicine Scientist Development Award, UNMC Physician-Scientist Training Program, the UNMC Mentored Scholars Program, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. Dr. Mikuls is supported by a VA Merit Award (CX000896) and grants from the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54GM115458), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R25AA020818), and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2P50AR60772).

From the Division of Rheumatology & Immunology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, and Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, NE.

Abstract

- Objective: To review cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

- Methods: Literature review of the assessment of CVD risk in RA.

- Results: CVD is the leading cause of death among RA patients.

Because of the increased risk of CVD events and CVD mortality in patients with RA, regular assessment of CVD risk and aggressive management of CVD risk in these patients is crucial. CVD risk estimation typically centers on the use of well-established CVD risk calculators. Most CVD risk scores from the general population do not contain RA-related factors predictive of CVD but have had more extensive performance testing, while novel RA-derived CVD risk scores that incorporate RA-related factors have had limited external validity testing. Neither set of risk scores incorporates novel imaging modalities or serum biomarkers, which are most likely to be helpful among individuals at intermediate risk. - Conclusion: Primary care and rheumatology providers must be aware of the increased risk of CVD in RA, a risk that approaches that of diabetic patients.

Routine assessment of CVD risk is an essential first step in minimizing CVD risk in this population. Until the performance of RA-specific CVD risk scores can be better established, we recommend the use of nationally endorsed CVD risk scores, with the frequency of reassessment based on CVD risk.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis; cardiovascular disease; cardiovascular risk assessment.

Editor’s note: This article is part 1 of a 2-part article. “Management of Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis” was published in the March/April 2019 issue.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, autoimmune inflammatory arthritis affecting up to 1% of the US population that can lead to joint damage, functional disability, and reduced quality of life.1 In addition to articular involvement, systemic inflammation accompanying RA may lead to extra-articular manifestations and increase the risk of premature death.2 Cardiovascular disease (CVD), accounting for nearly half of all deaths among RA patients, is now recognized as a critical extra-articular manifestation of RA.2,3 As such, assessment and management of CVD risk is essential to the comprehensive care of the RA patient. This article reviews the approach to assessing CVD risk in patients with RA; the management of both traditional and RA-specific risk factors is discussed in a separate article.

Scope of the Problem

In a large meta-analysis of observational studies that included more than 111,000 patients with RA, CVD-related mortality rates were 1.5 times higher among RA patients than among general population controls.4 The risk of overall CVD, including nonfatal events, is similar; a separate meta-analysis of observational studies that included more than 41,000 patients with RA calculated a pooled relative risk for incident CVD of 1.48.5 Individual analyses identified heightened risk of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), cerebrovascular accident, and congestive heart failure (CHF).5 Perhaps more illustrative of the magnitude of the problem, the risk of CVD in RA approaches that observed among individuals with diabetes mellitus.6,7

Coronary artery disease (CAD) accounts for a significant portion of the CVD risk in RA, but its presentation may be atypical in RA patients. RA patients are at higher risk of suffering unrecognized myocardial infarction (MI) and sudden cardiac death.8 The reasons for silent ischemia in RA are not fully known, but have been hypothesized to include imbalances of inflammatory cytokines, alterations in pain sensitization, or the female predominance of RA (with women more often presenting with atypical symptoms of myocardial ischemia).9 Alarmingly, a retrospective chart review study reported that RA patients admitted for an acute MI were less likely to receive appropriate reperfusion therapy as well as secondary prevention with beta-blockers and lipid-lowering agents.10 Even with appropriate therapy, long-term outcomes such as mortality and recurrent ischemic events are more likely to occur in RA patients after acute MI.11-13

Independent of ischemic heart disease, RA patients are at increased risk of CHF.14-16 RA patients are at particular risk for CHF with preserved ejection fraction,17 which may be a result of systemic inflammation causing left ventricular stiffening.18,19 Similar to CAD, patients with RA are less likely to present with typical CHF symptoms, are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care, and have higher mortality rates following presentation with CHF.17

Although accounting for a lower proportion of the excess CVD morbidity and mortality in RA, the risk of noncardiac vascular disease is also increased in RA patients. Large meta-analyses have identified positive associations between RA with both ischemic (odds ratio [OR], 1.64 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.32-2.05]) and hemorrhagic (OR, 1.68 [95% CI, 1.11-2.53]) stroke.20 Similarly, RA patients appear to have an approximately twofold higher risk of venous thromboembolic events.21 Less frequently studied than other forms of CVD, peripheral arterial disease may be increased in RA patients independent of other CVD and CVD risk factors.22,23

Assessing CVD Risk in RA

CVD Risk Scores

In order to identify patients who may benefit from primary prevention interventions, such as lipid-lowering therapy, CVD risk estimation typically centers on the use of well-established CVD risk calculators (Table). CVD risk scores such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS), Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE), and American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Pooled Cohort Equation incorporate traditional CVD risk factors, including age, sex, smoking status, blood pressure, lipid levels, and presence of diabetes mellitus.24,25 However, CVD risk in RA patients appears to be inadequately explained by traditional CVD risk factors,26 with disease activity and inflammation being associated with higher CVD risk. Recognizing that inflammation may contribute to CVD risk even among non-RA patients, the Reynolds Risk Score includes high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) in its calculation.27 In contrast to more robust performance in the general population, these well-established CVD risk scores have had variable predictive potential of incident CVD in RA patients.28-30

Several models, or adaptations to existing models, have been proposed to improve CVD risk assessment in RA populations (Table). In 2009, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) task force suggested using a correction factor of 1.5 with traditional CVD risk models in RA patients with 2 of the following criteria: disease duration exceeding 10 years, rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody positivity, or extra-articular manifestations of RA.31 An update to these recommendations in 2015 continued to propose the use of a 1.5 correction factor, but suggested applying this to all RA patients.32 QRISK2, a modification to QRISK1 which was developed to predict CVD in the UK general population, includes the diagnosis of RA as a risk factor, and in early validation efforts more accurately discriminated patients in the general population at increased risk of CVD compared to the FRS.33 Additional disease-specific risk factors such as systemic lupus, steroid use, severe mental illness, and steroid and atypical antipsychotic use were incorporated in the QRISK3 algorithm, with model performance similar to the QRISK2.34 The Expanded Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Score for RA (ERS-RA) was specifically developed to assess CVD risk in RA patients by including RA disease activity, level of physical disability, RA disease duration, and prednisone use.35 Despite efforts to develop “RA-specific” risk scores, these have not consistently outperformed traditional CVD risk calculators.36-38 In one study involving more than 1700 RA patients, the ERS-RA performed similarly to the FRS and Reynolds Risk Score, with a net reclassification index of just 2.3% versus the FRS.36

Imaging Modalities

Imaging modalities may assist in characterizing the increased risk of CVD in RA and the subclinical CVD manifestations that occur. For example, RA patients were shown to have more prevalent and unstable coronary plaque, higher carotid intima media thickness, and impaired myocardial function with computed tomography (CT) angiography and carotid ultrasound.39,40 However, studies harnessing noninvasive imaging to augment CVD risk assessment in RA patients are limited.

Carotid ultrasound has been the most extensively studied imaging modality for CVD risk assessment in RA. In a cohort of 599 RA patients with no history of ACS, rates of ACS were nearly 4 times higher in RA patients with bilateral carotid plaque on carotid ultrasound, and the association with ACS was independent of other traditional and RA-related risk factors.41 Presence of bilateral carotid plaques was similarly associated with an increased risk of overall CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 3.34 [95% CI, 1.21-9.22]), ACS alone (HR, 6.31 [95% CI, 1.27-31.40]), and a lower mean CVD event-free survival (13.9 versus 15.2 years, P = 0.01) in a separate inception cohort of 105 RA patients with no prior history of CVD.42 The most useful application of carotid ultrasound may be in conjunction with clinical CVD risk models. Use of carotid ultrasound improved CVD risk stratification among RA patients who were considered at moderate risk by the EULAR-modified SCORE calculator.43 Beyond carotid ultrasound, measurement of arterial stiffness through ultrasound could also aid in CVD risk stratification. Aortic pulse wave velocity and augmentation index, measures of arterial stiffness, are predictive of CVD in the general population as well as RA patients and improve with reduction in RA disease activity.44,45 Peripheral arterial stiffness (brachial-ankle elasticity index) is impaired in RA patients and predictive of CVD morbidity and mortality in the general population.46,47

CT coronary angiography and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scores are reliable measures of coronary artery atherosclerosis and have been validated for CVD risk assessment in the general population.48-52 While the association between RA and CT-related findings of atherosclerosis is well established, assessment of CT-mediated evaluation as a prognostic tool for CVD in RA is limited. In one cohort study, CAC predicted higher rates of CVD events in Chinese patients with RA and systemic lupus erythematosus in a pooled analysis, although results were limited by low event rates and the absence of RA-only subanalyses.53

While the aforementioned imaging modalities have focused on enhancing the identification of atherosclerosis, echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful for detecting subclinical structural and/or functional abnormalities that predispose to CHF. Structural abnormalities including increased left ventricular mass and hypertrophy are more prevalent in RA patients and predict incident CHF in the general population.54-56 MRI measures of myocardial inflammation, including T1 mapping and extracellular volume, are associated with higher mortality rates and also appear to be elevated in RA patients.57,58 Whether identification of these imaging findings influences the cost-effective clinical management of RA patients needs further study.

Biomarkers

Serum biomarkers, such as the anti-CCP antibody, have become crucial to the evaluation of patients suspected to have RA. With the growing understanding of the role pro-inflammatory mediators play in CVD pathogenesis and the relative ease with which they can be measured, serum biomarkers have potential to inform CVD risk assessment. In the general population, hsCRP concentrations are predictive of CVD and are included in the Reynolds Risk Score.27 In RA, CRP concentrations are typically much higher than those observed among individuals in the general population solely at increased CVD risk, yet elevated levels remain predictive of CVD death independent of RA disease activity and traditional CVD risk factors.59 Several additional cytokines, chemokines, and adhesion molecules have been associated with surrogate markers of CVD in RA patients, although further study is needed to elucidate thresholds that signify increased CVD risk in a population characterized by the presence of systemic inflammation.60

Cardiac biomarkers used frequently in the general population may be useful to assess CVD risk in RA patients. N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP) is a biomarker typically used to evaluate CHF severity, but it may also predict long-term mortality in patients with coronary heart disease.61,62 Circulating NT-pro BNP concentrations are elevated in RA independent of prevalent CHF and may serve as a useful tool to identify subclinical cardiac disease in RA patients.63 High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (HS-cTnI) assays are capable of detecting levels of cardiac troponin below the threshold typically used to diagnose ACS. HS-cTnI levels are increased in RA patients independent of additional CVD risk factors, and elevated levels (> 1.5 pg/mL) were associated with more severe CT angiography findings of coronary plaque as well as increased risk of CVD events.64,65

Clinical Application

A fully validated algorithm for CVD risk assessment in RA is lacking. Most CVD risk scores from the general population do not contain RA-related factors predictive of CVD but have had more extensive performance testing. In contrast, novel RA-derived CVD risk scores incorporate RA-related factors, but have had limited external validity testing. Additionally, RA-derived risk scores are less likely to be utilized and adopted by primary care providers and cardiologists involved in RA patients’ care. Neither set of risk scores incorporates novel imaging modalities or serum biomarkers, which are most likely to be helpful among individuals at intermediate risk. Therefore, until the performance of RA-specific CVD risk scores can be better established, we recommend the use of nationally endorsed CVD risk scores, with the frequency of reassessment based on CVD risk.

Conclusion

RA patients are at increased risk of CVD and CVD-related mortality relative to the general population. The disproportionate CVD burden seen in RA appears to be multifactorial, owing to the complex effects of systemic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and pro-atherogenic lipoprotein modifications. Additionally, many traditional CVD risk factors are more prevalent and suboptimally managed in RA patients. To mitigate the increased risk of CVD in RA, primary care and subspecialty providers alike must be aware of this heightened risk in RA, perform frequent assessment of CVD risk, and

Corresponding author: Bryant R. England, MD; 986270 Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6270; Bryant.england@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. England is supported by UNMC Internal Medicine Scientist Development Award, UNMC Physician-Scientist Training Program, the UNMC Mentored Scholars Program, and the Rheumatology Research Foundation Scientist Development Award. Dr. Mikuls is supported by a VA Merit Award (CX000896) and grants from the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54GM115458), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R25AA020818), and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (2P50AR60772).

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the united states. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15-25.

2. England BR, Sayles H, Michaud K, et al. Cause-specific mortality in male US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:36-45.

3. Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S35-61.

4. Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690-1697.

5. Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1524-1529.

6. van Halm VP, Peters MJ, Voskuyl AE, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study, the CARRE investigation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1395-1400.

7. Peters MJ, van Halm VP, Voskuyl AE, et al. Does rheumatoid arthritis equal diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1571-1579.

8. Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:402-411.

9. Cardiovascular disease in women--often silent and fatal. Lancet. 2011;378:200,6736(11)61108-61112.

10. Van Doornum S, Brand C, Sundararajan V, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients receive less frequent acute reperfusion and secondary prevention therapy after myocardial infarction compared with the general population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R183.

11. Sodergren A, Stegmayr B, Lundberg V, et al. Increased incidence of and impaired prognosis after acute myocardial infarction among patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:263-266.

12. Douglas KM, Pace AV, Treharne GJ, et al. Excess recurrent cardiac events in rheumatoid arthritis patients with acute coronary syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:348-353.

13. McCoy SS, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. Long-term outcomes and treatment after myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:605-610.

14. Mantel A, Holmqvist M, Andersson DC, et al. Association between rheumatoid arthritis and risk of ischemic and nonischemic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1275-1285.

15. Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Kremers HM, et al. How much of the increased incidence of heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic heart disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3039-3044.

16. Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, et al. The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:412-420.

17. Davis JM,3rd, Roger VL, Crowson CS, et al. The presentation and outcome of heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis differs from that in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2603-2611.

18. Arslan S, Bozkurt E, Sari RA, Erol MK. Diastolic function abnormalities in active rheumatoid arthritis evaluation by conventional doppler and tissue doppler: Relation with duration of disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:294-299.

19. Liang KP, Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, et al. Increased prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1665-1670.

20. Wiseman SJ, Ralston SH, Wardlaw JM. Cerebrovascular disease in rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2016;47:943-950.

21. Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Spanuchart I, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:297-304.

22. Stamatelopoulos KS, Kitas GD, Papamichael CM, et al. Subclinical peripheral arterial disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:305-309.

23. Chuang YW, Yu MC, Lin CL, et al. Risk of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A nationwide population-based cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:439-445.

24. Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in europe: The SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987-1003.

25. D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117:743-753.

26. del Rincon ID, Williams K, Stern MP, et al. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2737-2745.

27. Ridker PM, Buring JE, Rifai N, Cook NR. Development and validation of improved algorithms for the assessment of global cardiovascular risk in women: The Reynolds Risk Score. JAMA. 2007;297:611-619.

28. Arts EE, Popa C, Den Broeder AA, et al. Performance of four current risk algorithms in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:668-674.

29. Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Roger VL, et al. Usefulness of risk scores to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:420-424.

30. Kawai VK, Chung CP, Solus JF, et al. The ability of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cardiovascular risk score to identify rheumatoid arthritis patients with high coronary artery calcification scores. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:381-385.

31. Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:325-331.

32. Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:17-28.

33. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: Prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336:1475-1482.

34. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2099.

35. Solomon DH, Greenberg J, Curtis JR, et al. Derivation and internal validation of an expanded cardiovascular risk prediction score for rheumatoid arthritis: A consortium of rheumatology researchers of north america registry study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1995-2003.

36. Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Semb AG, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-specific cardiovascular risk scores are not superior to general risk scores: A validation analysis of patients from seven countries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1102-1110.

37. Alemao E, Cawston H, Bourhis F, et al. Comparison of cardiovascular risk algorithms in patients with vs without rheumatoid arthritis and the role of C-reactive protein in predicting cardiovascular outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:777-786.

38. Crowson CS, Rollefstad S, Kitas GD, et al. Challenges of developing a cardiovascular risk calculator for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2017;12: e0174656.

39. Karpouzas GA, Malpeso J, Choi TY, et al. Prevalence, extent and composition of coronary plaque in patients with rheumatoid arthritis without symptoms or prior diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1797-1804.

40. van Sijl AM, Peters MJ, Knol DK, et al. Carotid intima media thickness in rheumatoid arthritis as compared to control subjects: A meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;40:3893-97.

41. Evans MR, Escalante A, Battafarano DF, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis predicts incident acute coronary syndromes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:1211-1220.

42. Ajeganova S, de Faire U, Jogestrand T, et al. Carotid atherosclerosis, disease measures, oxidized low-density lipoproteins, and atheroprotective natural antibodies for cardiovascular disease in early rheumatoid arthritis--an inception cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39:1146-1154.

43. Corrales A, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Peiro ME, et al. Carotid ultrasound is useful for the cardiovascular risk stratification of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Results of a population-based study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:722-727.

44. Ikdahl E, Rollefstad S, Wibetoe G, et al. Predictive value of arterial stiffness and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis for cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:1622-1630.

45. Provan SA, Semb AG, Hisdal J, et al. Remission is the goal for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:812-817.

46. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2012;60:556-562.

47. Ambrosino P, Tasso M, Lupoli R, et al. Non-invasive assessment of arterial stiffness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of literature studies. Ann Med. 2015;47:457-467.

48. Rumberger JA, Simons DB, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Coronary artery calcium area by electron-beam computed tomography and coronary atherosclerotic plaque area. A histopathologic correlative study. Circulation. 1995;92:2157-2162.

49. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336-1345.

50. Task Force Members, Montalescot G, Sechtem U, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: The task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

51. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935-2959.

52. Hou ZH, Lu B, Gao Y, et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography and calcium score for major adverse cardiac events in outpatients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:990-999.

53. Yiu KH, Mok MY, Wang S, et al. Prognostic role of coronary calcification in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:345-350.

54. Wright K, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular comorbidity in rheumatic diseases: A focus on heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10:339-352.

55. Rudominer RL, Roman MJ, Devereux RB, et al. Independent association of rheumatoid arthritis with increased left ventricular mass but not with reduced ejection fraction. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:22-29.

56. Bluemke DA, Kronmal RA, Lima JA, et al. The relationship of left ventricular mass and geometry to incident cardiovascular events: The MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2148-2155.

57. Ntusi NAB, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis and inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis: Insights from CMR T1 mapping. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:526-536.

58. Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG, et al. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012;126:1206-1216.

59. Goodson NJ, Symmons DP, Scott DG, et al. Baseline levels of C-reactive protein and prediction of death from cardiovascular disease in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: A ten-year followup study of a primary care-based inception cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2293-2299.

60. Kozera L, Andrews J, Morgan AW. Cardiovascular risk and rheumatoid arthritis--the next step: Differentiating true soluble biomarkers of cardiovascular risk from surrogate measures of inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50:1944-1954.

61. Cardarelli R, Lumicao TG Jr. B-type natriuretic peptide: A review of its diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic monitoring value in heart failure for primary care physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16:327-333.

62. Kragelund C, Gronning B, Kober L, et al. N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and long-term mortality in stable coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:666-675.

63. Harney SM, Timperley J, Daly C, et al. Brain natriuretic peptide is a potentially useful screening tool for the detection of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:136.

64. Bradham WS, Bian A, Oeser A, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin-I is elevated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, independent of cardiovascular risk factors and inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38930.

65. Karpouzas GA, Estis J, Rezaeian P, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I is a biomarker for occult coronary plaque burden and cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57:1080-1088.

66. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2889-2934.

67. Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation. 2002;105:310-315.

1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the united states. part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15-25.

2. England BR, Sayles H, Michaud K, et al. Cause-specific mortality in male US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68:36-45.

3. Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:S35-61.

4. Avina-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1690-1697.

5. Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1524-1529.

6. van Halm VP, Peters MJ, Voskuyl AE, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis versus diabetes as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study, the CARRE investigation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1395-1400.

7. Peters MJ, van Halm VP, Voskuyl AE, et al. Does rheumatoid arthritis equal diabetes mellitus as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A prospective study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1571-1579.

8. Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:402-411.

9. Cardiovascular disease in women--often silent and fatal. Lancet. 2011;378:200,6736(11)61108-61112.

10. Van Doornum S, Brand C, Sundararajan V, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis patients receive less frequent acute reperfusion and secondary prevention therapy after myocardial infarction compared with the general population. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R183.

11. Sodergren A, Stegmayr B, Lundberg V, et al. Increased incidence of and impaired prognosis after acute myocardial infarction among patients with seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:263-266.

12. Douglas KM, Pace AV, Treharne GJ, et al. Excess recurrent cardiac events in rheumatoid arthritis patients with acute coronary syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:348-353.

13. McCoy SS, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. Long-term outcomes and treatment after myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:605-610.

14. Mantel A, Holmqvist M, Andersson DC, et al. Association between rheumatoid arthritis and risk of ischemic and nonischemic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1275-1285.

15. Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Kremers HM, et al. How much of the increased incidence of heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic heart disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3039-3044.

16. Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, et al. The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:412-420.

17. Davis JM,3rd, Roger VL, Crowson CS, et al. The presentation and outcome of heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis differs from that in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2603-2611.