User login

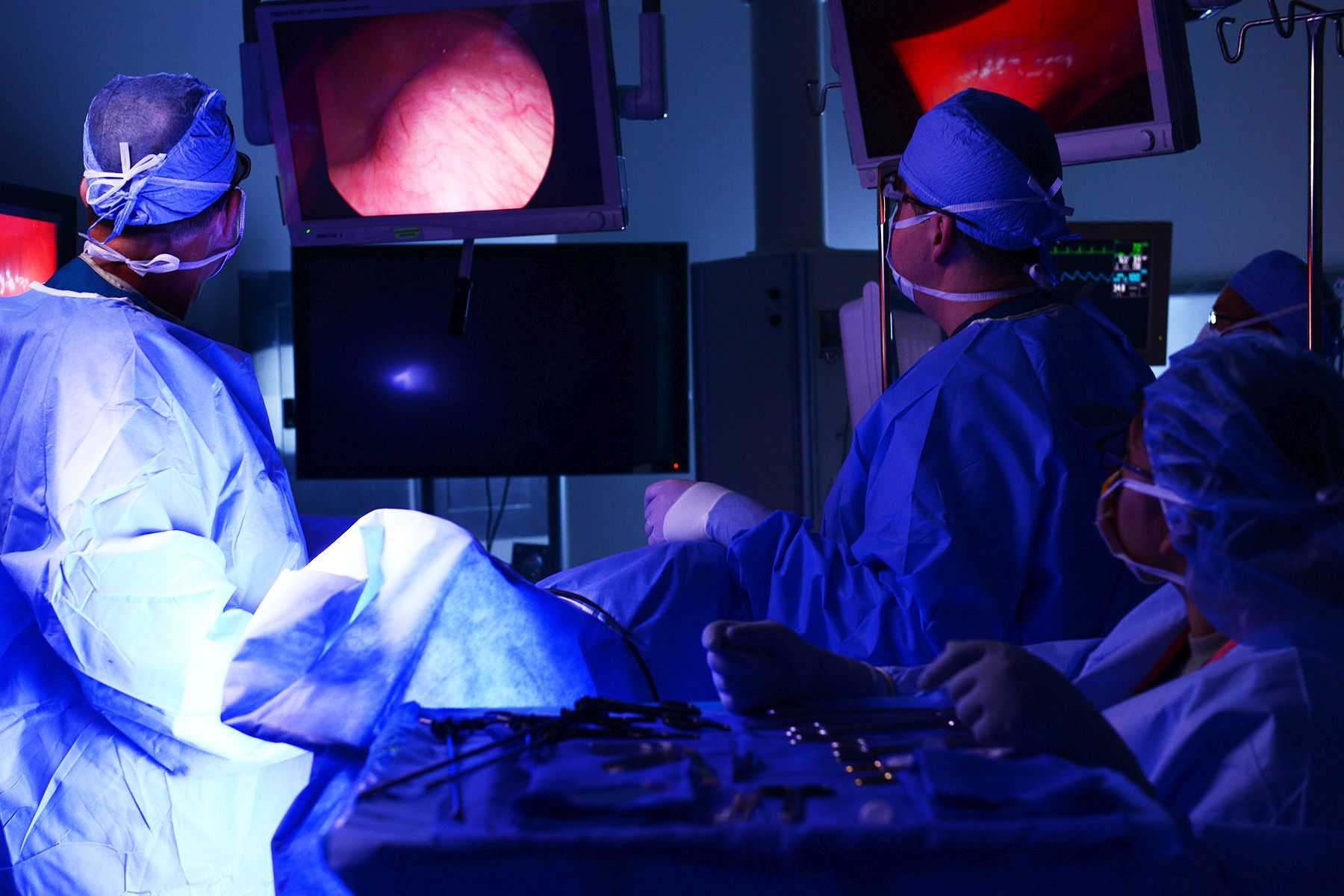

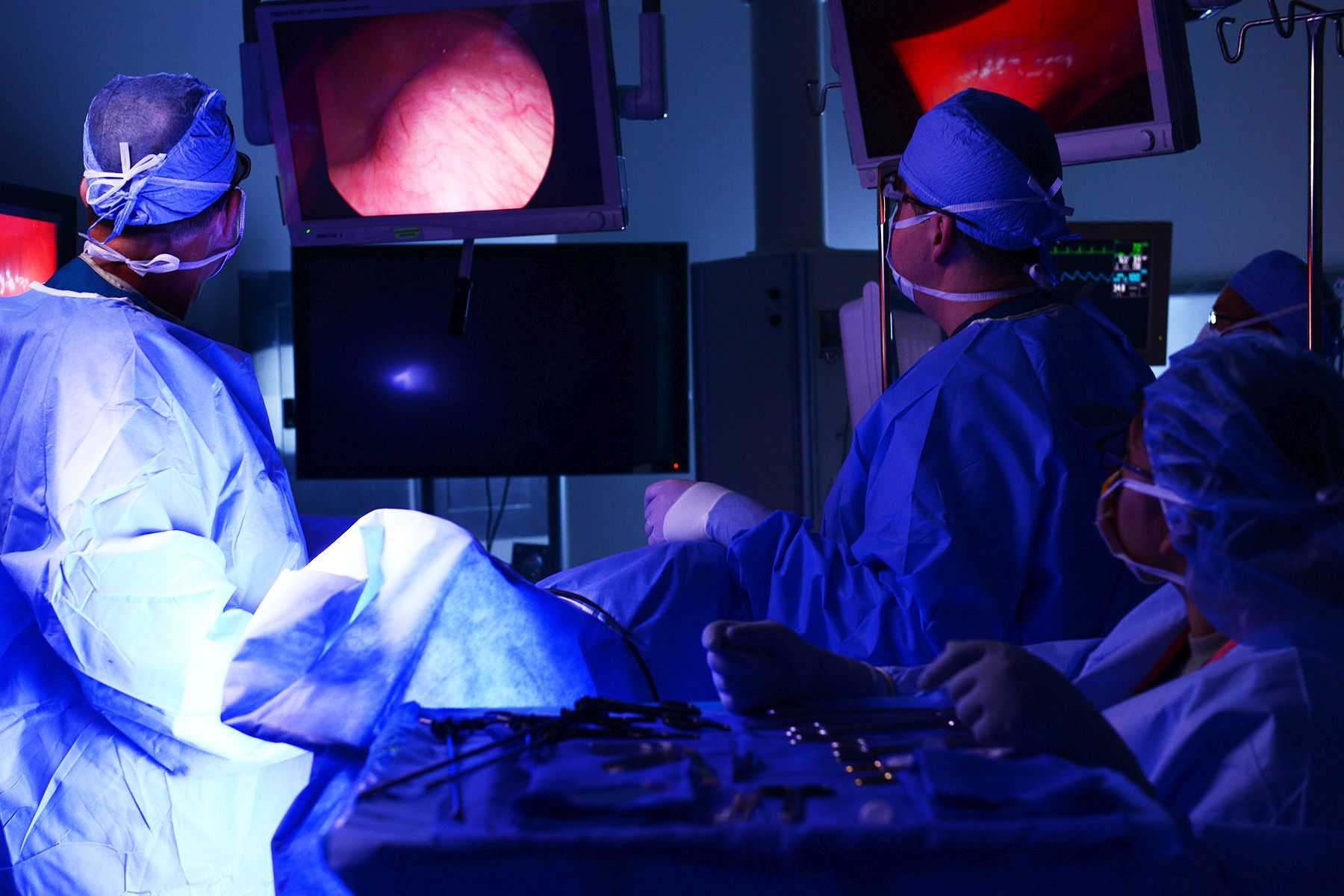

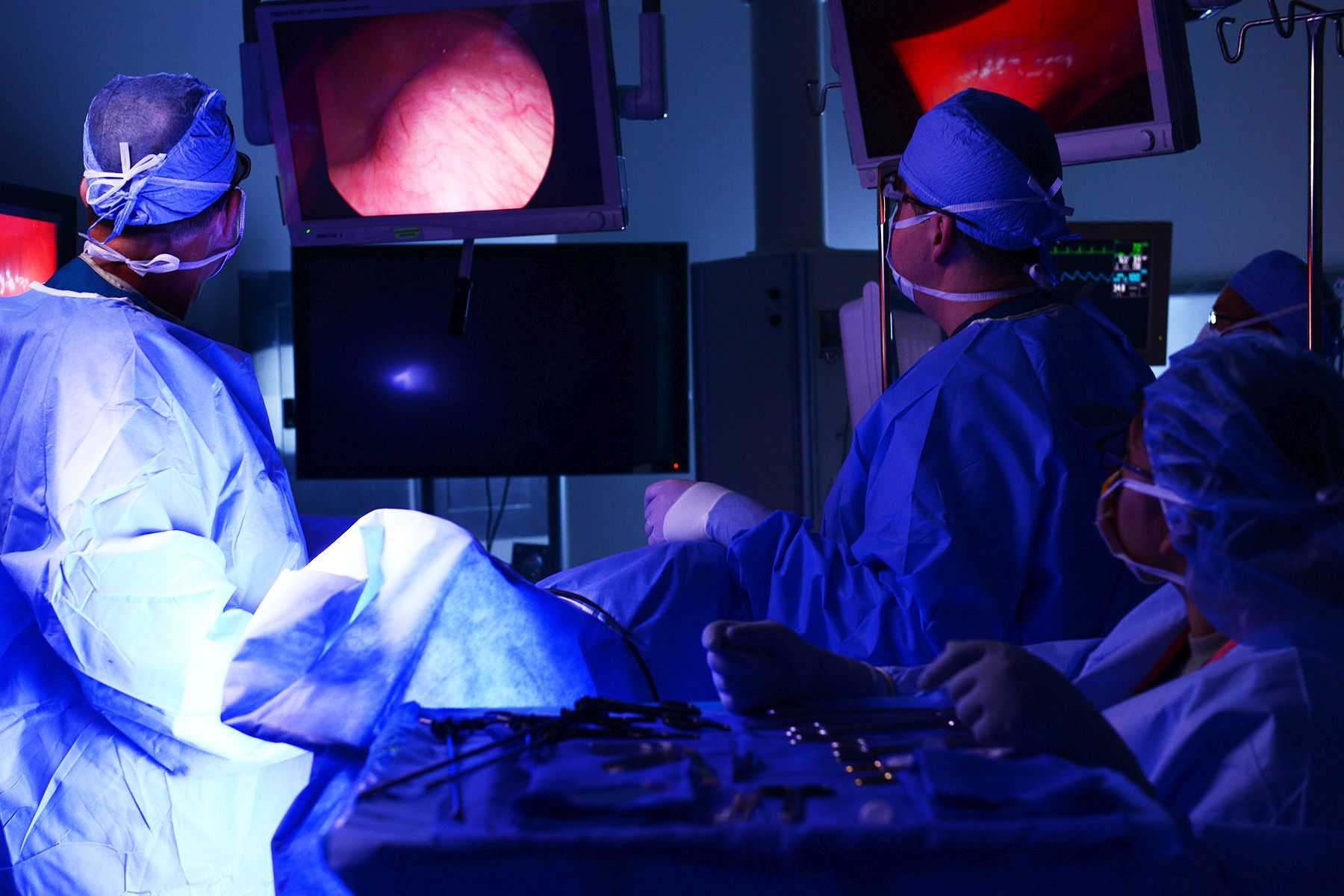

Robotic vs. conventional laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: No winner yet

Robot-assisted rectal surgery is gaining acceptance but, with some exceptions, outcomes are not significantly improved over the conventional laparoscopic approach, a meta-analysis has found.

Conducted by Katie Jones, MD, and her colleagues at Brighton and Sussex (England) University Hospital NHS Trust, the meta-analysis was designed as a follow-up to ROLARR (isrctn.org ID: ISRCTN80500123), a randomized clinical trial in which robot-assisted and. conventional laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer were studied for risk of conversion to open surgery. That trial findings showed that robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery did not significantly reduce the risk of conversion. For other outcomes (pathology, complications, bladder, and sexual function), the differences between the two approaches were insignificant. But the two surgical approaches did differ on cost: The robot-assisted operation was significantly more expensive than the conventional laparoscopic procedure.

Dr. Jones and her colleagues analyzed data from ROLARR in the context of 27 other qualifying studies and confirmed many of the ROLARR findings. The 27 case control studies comprised 5,547 patients and had comparable outcomes data.

The outcomes of interest were duration of operation, conversion risk, blood loss, length of stay, oncological outcomes, time to first flatus, reoperation rate, postoperative morbidity, and postoperative mortality.

The investigators found that duration of the operation was longer for the robot-assisted procedure, compared with the conventional laparoscopic approach, though this difference was not statistically significant (z = 1.28, P = .20), and blood loss, morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups. Oncological outcomes (risk of positive circumferential resection margins, lymph node yield, and length of distal resection margins) were similar for these two surgical approaches.

In contrast to the ROLARR findings, this meta-analysis found that the risk of conversion favored the robot-assisted procedure (z = 5.51, P = .00001). Hospital stay (z = 2.46, P = 01) and time to first flatus outcomes (z = 3.09, P = .002) favored the robot-assisted procedure. Postop morbidity and mortality and reoperation rate were similar in the two groups.

“Based upon the findings of this largest-ever series on the role of robotic surgery in rectal cancer resection, the [robot-assisted procedure] is certainly a feasible technique and oncologically safe surgical intervention but failed to demonstrate any superiority over [the conventional laparoscopic approach] for many surgical outcomes,” the investigators wrote. “Mere advantage of robotic surgery was noted in only three postoperative outcomes, that is early passage of flatus, lower risk of conversion, and shorter hospitalization.”

Dr. Jones and her colleagues declared they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jones K et al. World J Gastroentrol. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.449.

Robot-assisted rectal surgery is gaining acceptance but, with some exceptions, outcomes are not significantly improved over the conventional laparoscopic approach, a meta-analysis has found.

Conducted by Katie Jones, MD, and her colleagues at Brighton and Sussex (England) University Hospital NHS Trust, the meta-analysis was designed as a follow-up to ROLARR (isrctn.org ID: ISRCTN80500123), a randomized clinical trial in which robot-assisted and. conventional laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer were studied for risk of conversion to open surgery. That trial findings showed that robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery did not significantly reduce the risk of conversion. For other outcomes (pathology, complications, bladder, and sexual function), the differences between the two approaches were insignificant. But the two surgical approaches did differ on cost: The robot-assisted operation was significantly more expensive than the conventional laparoscopic procedure.

Dr. Jones and her colleagues analyzed data from ROLARR in the context of 27 other qualifying studies and confirmed many of the ROLARR findings. The 27 case control studies comprised 5,547 patients and had comparable outcomes data.

The outcomes of interest were duration of operation, conversion risk, blood loss, length of stay, oncological outcomes, time to first flatus, reoperation rate, postoperative morbidity, and postoperative mortality.

The investigators found that duration of the operation was longer for the robot-assisted procedure, compared with the conventional laparoscopic approach, though this difference was not statistically significant (z = 1.28, P = .20), and blood loss, morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups. Oncological outcomes (risk of positive circumferential resection margins, lymph node yield, and length of distal resection margins) were similar for these two surgical approaches.

In contrast to the ROLARR findings, this meta-analysis found that the risk of conversion favored the robot-assisted procedure (z = 5.51, P = .00001). Hospital stay (z = 2.46, P = 01) and time to first flatus outcomes (z = 3.09, P = .002) favored the robot-assisted procedure. Postop morbidity and mortality and reoperation rate were similar in the two groups.

“Based upon the findings of this largest-ever series on the role of robotic surgery in rectal cancer resection, the [robot-assisted procedure] is certainly a feasible technique and oncologically safe surgical intervention but failed to demonstrate any superiority over [the conventional laparoscopic approach] for many surgical outcomes,” the investigators wrote. “Mere advantage of robotic surgery was noted in only three postoperative outcomes, that is early passage of flatus, lower risk of conversion, and shorter hospitalization.”

Dr. Jones and her colleagues declared they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jones K et al. World J Gastroentrol. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.449.

Robot-assisted rectal surgery is gaining acceptance but, with some exceptions, outcomes are not significantly improved over the conventional laparoscopic approach, a meta-analysis has found.

Conducted by Katie Jones, MD, and her colleagues at Brighton and Sussex (England) University Hospital NHS Trust, the meta-analysis was designed as a follow-up to ROLARR (isrctn.org ID: ISRCTN80500123), a randomized clinical trial in which robot-assisted and. conventional laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer were studied for risk of conversion to open surgery. That trial findings showed that robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery did not significantly reduce the risk of conversion. For other outcomes (pathology, complications, bladder, and sexual function), the differences between the two approaches were insignificant. But the two surgical approaches did differ on cost: The robot-assisted operation was significantly more expensive than the conventional laparoscopic procedure.

Dr. Jones and her colleagues analyzed data from ROLARR in the context of 27 other qualifying studies and confirmed many of the ROLARR findings. The 27 case control studies comprised 5,547 patients and had comparable outcomes data.

The outcomes of interest were duration of operation, conversion risk, blood loss, length of stay, oncological outcomes, time to first flatus, reoperation rate, postoperative morbidity, and postoperative mortality.

The investigators found that duration of the operation was longer for the robot-assisted procedure, compared with the conventional laparoscopic approach, though this difference was not statistically significant (z = 1.28, P = .20), and blood loss, morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups. Oncological outcomes (risk of positive circumferential resection margins, lymph node yield, and length of distal resection margins) were similar for these two surgical approaches.

In contrast to the ROLARR findings, this meta-analysis found that the risk of conversion favored the robot-assisted procedure (z = 5.51, P = .00001). Hospital stay (z = 2.46, P = 01) and time to first flatus outcomes (z = 3.09, P = .002) favored the robot-assisted procedure. Postop morbidity and mortality and reoperation rate were similar in the two groups.

“Based upon the findings of this largest-ever series on the role of robotic surgery in rectal cancer resection, the [robot-assisted procedure] is certainly a feasible technique and oncologically safe surgical intervention but failed to demonstrate any superiority over [the conventional laparoscopic approach] for many surgical outcomes,” the investigators wrote. “Mere advantage of robotic surgery was noted in only three postoperative outcomes, that is early passage of flatus, lower risk of conversion, and shorter hospitalization.”

Dr. Jones and her colleagues declared they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Jones K et al. World J Gastroentrol. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.449.

FROM WORLD JOURNAL OF GASTROINTESTINAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Duration of the operation was longer for the robot-assisted procedure, compared with the conventional laparoscopic approach (z = 1.28, P = .20), but blood loss, morbidity, and mortality were similar between the two groups.

Study details: Meta-analysis of 27 studies and one RCT of patients who had robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery or conventional laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer.

Disclosures: The investigators had no disclosures.

Source: Jones K. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i11.449.

‘Organoid technology’ poised to transform cancer care

BOSTON– Imagine being able to .

The implications are nearly endless. To start, chemotherapy and radiation options could be screened in vitro, much like culture and sensitivity testing of bacteria, to find a patient’s best option. Tumor cultures could be banked for mass screening of new cytotoxic candidates.

It’s already beginning to happen in a few research labs around the world, and it might foretell a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

After decades of failure, the trick to growing tumor cells in culture has finally been figured out. When stem cells are fished out of healthy tissue – from the crypts of the gastrointestinal lining, for instance – and put into a three-dimensional matrix culture with growth factors, they grow into little replications of the organs they came from, called “organoids;” when stem cells are pulled from cancers, they replicate the primary tumor, growing into “tumoroids” ready to be tested against cytotoxic drugs and radiation.

Philip B. Paty, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and organoid researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said he is certain that the person who led the team that figured out the right culture condition – Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, a molecular genetics professor at the University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) – is destined for a Nobel Prize.

Dr. Paty took a few minutes at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons to explain in an interview why, and what ‘organoid technology’ will likely mean for cancer treatment in a few years.

“The ability to grow and sustain cancer means that we now can start doing real science on human tissues. We could never do this before. We’ve been treating cancer without being able to grow tumors and study them.” The breakthrough opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” and will likely take personalized cancer treatment to a new level, he said.

“It remains to be proven that “organoid technology “can change outcomes for patients, but those studies are likely coming,” said Dr. Paty, who investigates tumoroid response to radiation in his own lab work.

BOSTON– Imagine being able to .

The implications are nearly endless. To start, chemotherapy and radiation options could be screened in vitro, much like culture and sensitivity testing of bacteria, to find a patient’s best option. Tumor cultures could be banked for mass screening of new cytotoxic candidates.

It’s already beginning to happen in a few research labs around the world, and it might foretell a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

After decades of failure, the trick to growing tumor cells in culture has finally been figured out. When stem cells are fished out of healthy tissue – from the crypts of the gastrointestinal lining, for instance – and put into a three-dimensional matrix culture with growth factors, they grow into little replications of the organs they came from, called “organoids;” when stem cells are pulled from cancers, they replicate the primary tumor, growing into “tumoroids” ready to be tested against cytotoxic drugs and radiation.

Philip B. Paty, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and organoid researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said he is certain that the person who led the team that figured out the right culture condition – Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, a molecular genetics professor at the University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) – is destined for a Nobel Prize.

Dr. Paty took a few minutes at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons to explain in an interview why, and what ‘organoid technology’ will likely mean for cancer treatment in a few years.

“The ability to grow and sustain cancer means that we now can start doing real science on human tissues. We could never do this before. We’ve been treating cancer without being able to grow tumors and study them.” The breakthrough opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” and will likely take personalized cancer treatment to a new level, he said.

“It remains to be proven that “organoid technology “can change outcomes for patients, but those studies are likely coming,” said Dr. Paty, who investigates tumoroid response to radiation in his own lab work.

BOSTON– Imagine being able to .

The implications are nearly endless. To start, chemotherapy and radiation options could be screened in vitro, much like culture and sensitivity testing of bacteria, to find a patient’s best option. Tumor cultures could be banked for mass screening of new cytotoxic candidates.

It’s already beginning to happen in a few research labs around the world, and it might foretell a breakthrough in cancer treatment.

After decades of failure, the trick to growing tumor cells in culture has finally been figured out. When stem cells are fished out of healthy tissue – from the crypts of the gastrointestinal lining, for instance – and put into a three-dimensional matrix culture with growth factors, they grow into little replications of the organs they came from, called “organoids;” when stem cells are pulled from cancers, they replicate the primary tumor, growing into “tumoroids” ready to be tested against cytotoxic drugs and radiation.

Philip B. Paty, MD, FACS, a colorectal surgeon and organoid researcher at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, said he is certain that the person who led the team that figured out the right culture condition – Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, a molecular genetics professor at the University of Utrecht (the Netherlands) – is destined for a Nobel Prize.

Dr. Paty took a few minutes at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons to explain in an interview why, and what ‘organoid technology’ will likely mean for cancer treatment in a few years.

“The ability to grow and sustain cancer means that we now can start doing real science on human tissues. We could never do this before. We’ve been treating cancer without being able to grow tumors and study them.” The breakthrough opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” and will likely take personalized cancer treatment to a new level, he said.

“It remains to be proven that “organoid technology “can change outcomes for patients, but those studies are likely coming,” said Dr. Paty, who investigates tumoroid response to radiation in his own lab work.

REPORTING FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

SRS beats surgery in early control of brain mets, advantage fades with time

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) provides better early local control of brain metastases than complete surgical resection, but this advantage fades with time, according to investigators.

By 6 months, lower risks associated with SRS shifted in favor of those who had surgical resection, reported lead author Thomas Churilla, MD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia and his colleagues.

“Outside recognized indications for surgery such as establishing diagnosis or relieving mass effect, little evidence is available to guide the therapeutic choice of SRS vs. surgical resection in the treatment of patients with limited brain metastases,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators performed an exploratory analysis of data from the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22952-26001 phase 3 trial, which was designed to evaluate whole-brain radiotherapy for patients with one to three brain metastases who had undergone SRS or complete surgical resection. The present analysis involved 268 patients, of whom 154 had SRS and 114 had complete surgical resection.

Primary tumors included lung, breast, colorectum, kidney, and melanoma. Initial analysis showed that patients undergoing surgical resection, compared with those who had SRS, typically had larger brain metastases (median, 28 mm vs. 20 mm) and more often had 1 brain metastasis (98.2% vs. 74.0%). Mass locality also differed between groups; compared with patients receiving SRS, surgical patients more often had metastases in the posterior fossa (26.3% vs. 7.8%) and less often in the parietal lobe (18.4% vs. 39.6%).

After median follow-up of 39.9 months, risks of local recurrence were similar between surgical and SRS groups (hazard ratio, 1.15). Stratifying by interval, however, showed that surgical patients were at much higher risk of local recurrence in the first 3 months following treatment (HR for 0-3 months, 5.94). Of note, this risk faded with time (HR for 3-6 months, 1.37; HR for 6-9 months, 0.75; HR for 9 months or longer, 0.36). From the 6-9 months interval onward, surgical patients had lower risk of recurrence, compared with SRS patients, and the risk even decreased after the 6-9 month interval.

“Prospective controlled trials are warranted to direct the optimal local approach for patients with brain metastases and to define whether any population may benefit from escalation in local therapy,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Fonds Cancer in Belgium. One author reported receiving financial compensation from Pfizer via her institution.

SOURCE: Churilla T et al. JAMA Onc. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4610.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) provides better early local control of brain metastases than complete surgical resection, but this advantage fades with time, according to investigators.

By 6 months, lower risks associated with SRS shifted in favor of those who had surgical resection, reported lead author Thomas Churilla, MD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia and his colleagues.

“Outside recognized indications for surgery such as establishing diagnosis or relieving mass effect, little evidence is available to guide the therapeutic choice of SRS vs. surgical resection in the treatment of patients with limited brain metastases,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators performed an exploratory analysis of data from the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22952-26001 phase 3 trial, which was designed to evaluate whole-brain radiotherapy for patients with one to three brain metastases who had undergone SRS or complete surgical resection. The present analysis involved 268 patients, of whom 154 had SRS and 114 had complete surgical resection.

Primary tumors included lung, breast, colorectum, kidney, and melanoma. Initial analysis showed that patients undergoing surgical resection, compared with those who had SRS, typically had larger brain metastases (median, 28 mm vs. 20 mm) and more often had 1 brain metastasis (98.2% vs. 74.0%). Mass locality also differed between groups; compared with patients receiving SRS, surgical patients more often had metastases in the posterior fossa (26.3% vs. 7.8%) and less often in the parietal lobe (18.4% vs. 39.6%).

After median follow-up of 39.9 months, risks of local recurrence were similar between surgical and SRS groups (hazard ratio, 1.15). Stratifying by interval, however, showed that surgical patients were at much higher risk of local recurrence in the first 3 months following treatment (HR for 0-3 months, 5.94). Of note, this risk faded with time (HR for 3-6 months, 1.37; HR for 6-9 months, 0.75; HR for 9 months or longer, 0.36). From the 6-9 months interval onward, surgical patients had lower risk of recurrence, compared with SRS patients, and the risk even decreased after the 6-9 month interval.

“Prospective controlled trials are warranted to direct the optimal local approach for patients with brain metastases and to define whether any population may benefit from escalation in local therapy,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Fonds Cancer in Belgium. One author reported receiving financial compensation from Pfizer via her institution.

SOURCE: Churilla T et al. JAMA Onc. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4610.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) provides better early local control of brain metastases than complete surgical resection, but this advantage fades with time, according to investigators.

By 6 months, lower risks associated with SRS shifted in favor of those who had surgical resection, reported lead author Thomas Churilla, MD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia and his colleagues.

“Outside recognized indications for surgery such as establishing diagnosis or relieving mass effect, little evidence is available to guide the therapeutic choice of SRS vs. surgical resection in the treatment of patients with limited brain metastases,” the investigators wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators performed an exploratory analysis of data from the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22952-26001 phase 3 trial, which was designed to evaluate whole-brain radiotherapy for patients with one to three brain metastases who had undergone SRS or complete surgical resection. The present analysis involved 268 patients, of whom 154 had SRS and 114 had complete surgical resection.

Primary tumors included lung, breast, colorectum, kidney, and melanoma. Initial analysis showed that patients undergoing surgical resection, compared with those who had SRS, typically had larger brain metastases (median, 28 mm vs. 20 mm) and more often had 1 brain metastasis (98.2% vs. 74.0%). Mass locality also differed between groups; compared with patients receiving SRS, surgical patients more often had metastases in the posterior fossa (26.3% vs. 7.8%) and less often in the parietal lobe (18.4% vs. 39.6%).

After median follow-up of 39.9 months, risks of local recurrence were similar between surgical and SRS groups (hazard ratio, 1.15). Stratifying by interval, however, showed that surgical patients were at much higher risk of local recurrence in the first 3 months following treatment (HR for 0-3 months, 5.94). Of note, this risk faded with time (HR for 3-6 months, 1.37; HR for 6-9 months, 0.75; HR for 9 months or longer, 0.36). From the 6-9 months interval onward, surgical patients had lower risk of recurrence, compared with SRS patients, and the risk even decreased after the 6-9 month interval.

“Prospective controlled trials are warranted to direct the optimal local approach for patients with brain metastases and to define whether any population may benefit from escalation in local therapy,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Fonds Cancer in Belgium. One author reported receiving financial compensation from Pfizer via her institution.

SOURCE: Churilla T et al. JAMA Onc. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4610.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) provides better early local control of brain metastases than surgical resection, but this advantage fades with time.

Major finding: Patients treated with surgery were more likely to have local recurrence in the first 3 months following treatment, compared with patients treated with SRS (hazard ratio, 5.94).

Study details: An exploratory analysis of data from the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 22952-26001 phase 3 trial. Analysis involved 268 patients with one to three brain metastases who underwent whole-brain radiotherapy or observation after SRS (n = 154) or complete surgical resection (n = 114).

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Fonds Cancer in Belgium. Dr. Handorf reported financial compensation from Pfizer, via her institution.

Source: Churilla T et al. JAMA Onc. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4610.

Nipple-sparing mastectomy safe in older patients

BOSTON – For women undergoing results of recent studies suggest.

The procedure was “surgically safe” in older patients, with complication rates comparable to those seen in younger patients, Solange E. Cox, MD, of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, said in a presentation of one those two retrospective analyses at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“From this, we think that eligible older patients should be offered a nipple-sparing mastectomy as a surgical option for breast cancer, and age alone should not be used as criteria to exclude these patients from the option,” she said.

The second retrospective study showed that patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy had a rate of surgical complications and unintended reoperations comparable to what was seen in women undergoing primary surgery.

“Our big-picture takeaway from this study is that receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not a contraindication for nipple-sparing mastectomy,” said investigator Alex J. Bartholomew, MS, also of Medstar Georgetown University Hospital.

Mr. Bartholomew’s conclusion was based on an analysis of the nipple-sparing mastectomy registry of the American Society of Breast Surgeons that included a total of 3,125 breasts. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was used in 528, or 16.9%, while primary surgery was performed in 2,597, or 83.1%.

The overall rate of complications was 11%, with nonsignificant differences between the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups at 12.7% and 10.7%, respectively.

The rate of unintended reoperation, at 4.9%, was not significantly different in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups, at 5.2% and 4.8%, Mr. Bartholomew said. Similarly, he found that the rate of nipple areolar complex loss of 1% overall was not different between groups.

Advanced age was likewise not associated with increased complications in the study presented by Dr. Cox, which was a retrospective review of data for patients undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy from 1998 to 2015 at a single institution. That cohort included 38 patients age 60 years or older, and 358 younger patients.

The rate of complications was 15.5% for patients over age 60 years, and similarly, 13.0% for their younger counterparts (P = .590), Dr. Cox reported. Likewise, the rate of unintended operations was 13.3% and 15.3% for older and younger patients, respectively (P = .274).

These findings are important because advancing age has been associated with a decrease in the likelihood of nipple-sparing mastectomy, according to Dr. Cox.

For mastectomies in general, advanced age has been implicated as a potential risk factor for necrosis, technical complications, and poor outcomes with mastectomies. However, no prior studies had been done specifically to evaluate nipple-sparing mastectomies in older breast cancer patients, Dr. Cox said.

Nipple-sparing mastectomy provides both cosmetic and psychosocial benefits to patients, according to the researchers, because the procedure spares the nipple-areolar complex.

The researchers who had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCES: Cox S et al. SF310 abstract; Bartholomew AJ et al. SF310 abstract ACS Clinical Congress 2018

BOSTON – For women undergoing results of recent studies suggest.

The procedure was “surgically safe” in older patients, with complication rates comparable to those seen in younger patients, Solange E. Cox, MD, of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, said in a presentation of one those two retrospective analyses at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“From this, we think that eligible older patients should be offered a nipple-sparing mastectomy as a surgical option for breast cancer, and age alone should not be used as criteria to exclude these patients from the option,” she said.

The second retrospective study showed that patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy had a rate of surgical complications and unintended reoperations comparable to what was seen in women undergoing primary surgery.

“Our big-picture takeaway from this study is that receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not a contraindication for nipple-sparing mastectomy,” said investigator Alex J. Bartholomew, MS, also of Medstar Georgetown University Hospital.

Mr. Bartholomew’s conclusion was based on an analysis of the nipple-sparing mastectomy registry of the American Society of Breast Surgeons that included a total of 3,125 breasts. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was used in 528, or 16.9%, while primary surgery was performed in 2,597, or 83.1%.

The overall rate of complications was 11%, with nonsignificant differences between the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups at 12.7% and 10.7%, respectively.

The rate of unintended reoperation, at 4.9%, was not significantly different in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups, at 5.2% and 4.8%, Mr. Bartholomew said. Similarly, he found that the rate of nipple areolar complex loss of 1% overall was not different between groups.

Advanced age was likewise not associated with increased complications in the study presented by Dr. Cox, which was a retrospective review of data for patients undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy from 1998 to 2015 at a single institution. That cohort included 38 patients age 60 years or older, and 358 younger patients.

The rate of complications was 15.5% for patients over age 60 years, and similarly, 13.0% for their younger counterparts (P = .590), Dr. Cox reported. Likewise, the rate of unintended operations was 13.3% and 15.3% for older and younger patients, respectively (P = .274).

These findings are important because advancing age has been associated with a decrease in the likelihood of nipple-sparing mastectomy, according to Dr. Cox.

For mastectomies in general, advanced age has been implicated as a potential risk factor for necrosis, technical complications, and poor outcomes with mastectomies. However, no prior studies had been done specifically to evaluate nipple-sparing mastectomies in older breast cancer patients, Dr. Cox said.

Nipple-sparing mastectomy provides both cosmetic and psychosocial benefits to patients, according to the researchers, because the procedure spares the nipple-areolar complex.

The researchers who had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCES: Cox S et al. SF310 abstract; Bartholomew AJ et al. SF310 abstract ACS Clinical Congress 2018

BOSTON – For women undergoing results of recent studies suggest.

The procedure was “surgically safe” in older patients, with complication rates comparable to those seen in younger patients, Solange E. Cox, MD, of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, said in a presentation of one those two retrospective analyses at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“From this, we think that eligible older patients should be offered a nipple-sparing mastectomy as a surgical option for breast cancer, and age alone should not be used as criteria to exclude these patients from the option,” she said.

The second retrospective study showed that patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy had a rate of surgical complications and unintended reoperations comparable to what was seen in women undergoing primary surgery.

“Our big-picture takeaway from this study is that receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not a contraindication for nipple-sparing mastectomy,” said investigator Alex J. Bartholomew, MS, also of Medstar Georgetown University Hospital.

Mr. Bartholomew’s conclusion was based on an analysis of the nipple-sparing mastectomy registry of the American Society of Breast Surgeons that included a total of 3,125 breasts. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was used in 528, or 16.9%, while primary surgery was performed in 2,597, or 83.1%.

The overall rate of complications was 11%, with nonsignificant differences between the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups at 12.7% and 10.7%, respectively.

The rate of unintended reoperation, at 4.9%, was not significantly different in the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and primary surgery groups, at 5.2% and 4.8%, Mr. Bartholomew said. Similarly, he found that the rate of nipple areolar complex loss of 1% overall was not different between groups.

Advanced age was likewise not associated with increased complications in the study presented by Dr. Cox, which was a retrospective review of data for patients undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy from 1998 to 2015 at a single institution. That cohort included 38 patients age 60 years or older, and 358 younger patients.

The rate of complications was 15.5% for patients over age 60 years, and similarly, 13.0% for their younger counterparts (P = .590), Dr. Cox reported. Likewise, the rate of unintended operations was 13.3% and 15.3% for older and younger patients, respectively (P = .274).

These findings are important because advancing age has been associated with a decrease in the likelihood of nipple-sparing mastectomy, according to Dr. Cox.

For mastectomies in general, advanced age has been implicated as a potential risk factor for necrosis, technical complications, and poor outcomes with mastectomies. However, no prior studies had been done specifically to evaluate nipple-sparing mastectomies in older breast cancer patients, Dr. Cox said.

Nipple-sparing mastectomy provides both cosmetic and psychosocial benefits to patients, according to the researchers, because the procedure spares the nipple-areolar complex.

The researchers who had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCES: Cox S et al. SF310 abstract; Bartholomew AJ et al. SF310 abstract ACS Clinical Congress 2018

REPORTING FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and advancing age were not associated with increased rates of complications in women undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy in two recent studies.

Major finding: The overall rate of complications was not significantly different for neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs. primary surgery (12.7% vs. 10.7%) or for age over 60 years vs. younger age (15.5% vs. 13.0%).

Study details: Retrospective studies of a nipple-sparing mastectomy registry including more than 3,000 breasts (neoadjuvant chemotherapy vs. primary surgery study) and a single-institution study of nearly 400 patients (older vs. younger study).

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Cox S et al. and Bartholomew AJ et al. Session SF310 ACS Clinical Congress 2018.

'Liver first' for select stage IV colon cancer gaining traction

BOSTON –

It’s an alternative to usual care, meaning simultaneous bowel and liver resection or bowel resection with liver surgery later on.

Systemic chemotherapy comes first, followed by liver resection. If margins are microscopically negative, the patient gets another round of chemotherapy. If no additional lesions emerge, the primary tumor is taken out. The entire process can take up to a year.

The approach was developed in the Netherlands for rectal cancer with advanced liver metastases. The idea was to get the liver lesions out before they became unresectable, then remove the primary tumor later on. It’s gaining traction now for colon cancer, and beginning to trickle into the United States at a few academic medical centers.

It comes down to what’s more dangerous, the metastases or the primary tumor? Tumor science hasn’t answered that question yet. There’s general agreement that metastases are what kill people with cancer, but it’s not known if they come mostly from previous metastases or from the primary tumor. The liver-first approach assumes the former.

Liver-first is “extremely controversial. For older surgeons who are not in tertiary care centers, liver-first doesn’t make sense, and it doesn’t seem to make sense to patients. They wonder why you would go after the liver when they were diagnosed with a colon tumor,” said Janice Rafferty, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Cincinnati, at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“Well, it’s because the primary tumor doesn’t limit your life,” she continued. “The life-limiting disease is in the liver, not the colon. If you explain it to them that way, it makes sense. If we cannot get an R0 resection on the liver, it doesn’t make sense to go after the primary, unless it’s symptomatic with obstruction, bleeding, or fistula.”

There have been about 10 attempts at a randomized trial of this approach versus usual care, but they were not successful because of the difficulty of recruiting patients. Patients – and no doubt, some surgeons – may have some resistance to the logic of going after metastases first.

Dr. Rafferty moderated a review of research from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., that attempted to plug the evidence gap. The Yale investigators “presented really interesting data that shows that liver-first has improved survival,” she said.

The Yale team used the National Cancer Database to compare 2010-2015 outcomes from liver-first patients with patients who had simultaneous or bowel-first resections, followed by later liver resections. The database didn’t allow them to tease out simultaneous from bowel-first cases, so they lumped them together as usual care. To avoid confounding, rectal carcinomas and metastases to the lung, brain, and other organs were excluded.

Median survival was 34 months among 358 liver-first patients versus 24 months among 18,042 usual care patients in an intention-to-treat analysis. Among patients who completed their resections, median survival was 57 months among 140 liver-first patients versus 36 months with usual care in 3,988.

The benefit held after adjustment for patient and tumor characteristics (hazard ratio for death 0.77 in favor of liver first). When further adjusted for chemotherapy timing, there was a strong trend for liver-first but it was not statistically significant, suggesting that up-front chemotherapy contributed to the results (HR, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.01; P = .09).

There were many caveats. The liver-first patients were younger, with over half under the age of 60 years versus just over 40% in usual care. They were also healthier based on Charlson comorbidity scores and more likely to have upfront chemotherapy and be treated at an academic center.

So, what should surgeons make of these findings? Lead investigator Vadim Kurbatov, MD, a Yale surgery resident, argued that, at the very least, they suggest that liver-first is a viable option for stage IV colon cancer with isolated liver metastases. Going further, they suggest that liver first may be the right way to go for younger, healthier patients at academic centers.

For sicker stage IV patients, however, the role of liver-first is unclear. “We really do need a randomized trial,” he said.

Dr. Kurbatov and Dr. Rafferty had no relevant disclosures to report. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

BOSTON –

It’s an alternative to usual care, meaning simultaneous bowel and liver resection or bowel resection with liver surgery later on.

Systemic chemotherapy comes first, followed by liver resection. If margins are microscopically negative, the patient gets another round of chemotherapy. If no additional lesions emerge, the primary tumor is taken out. The entire process can take up to a year.

The approach was developed in the Netherlands for rectal cancer with advanced liver metastases. The idea was to get the liver lesions out before they became unresectable, then remove the primary tumor later on. It’s gaining traction now for colon cancer, and beginning to trickle into the United States at a few academic medical centers.

It comes down to what’s more dangerous, the metastases or the primary tumor? Tumor science hasn’t answered that question yet. There’s general agreement that metastases are what kill people with cancer, but it’s not known if they come mostly from previous metastases or from the primary tumor. The liver-first approach assumes the former.

Liver-first is “extremely controversial. For older surgeons who are not in tertiary care centers, liver-first doesn’t make sense, and it doesn’t seem to make sense to patients. They wonder why you would go after the liver when they were diagnosed with a colon tumor,” said Janice Rafferty, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Cincinnati, at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“Well, it’s because the primary tumor doesn’t limit your life,” she continued. “The life-limiting disease is in the liver, not the colon. If you explain it to them that way, it makes sense. If we cannot get an R0 resection on the liver, it doesn’t make sense to go after the primary, unless it’s symptomatic with obstruction, bleeding, or fistula.”

There have been about 10 attempts at a randomized trial of this approach versus usual care, but they were not successful because of the difficulty of recruiting patients. Patients – and no doubt, some surgeons – may have some resistance to the logic of going after metastases first.

Dr. Rafferty moderated a review of research from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., that attempted to plug the evidence gap. The Yale investigators “presented really interesting data that shows that liver-first has improved survival,” she said.

The Yale team used the National Cancer Database to compare 2010-2015 outcomes from liver-first patients with patients who had simultaneous or bowel-first resections, followed by later liver resections. The database didn’t allow them to tease out simultaneous from bowel-first cases, so they lumped them together as usual care. To avoid confounding, rectal carcinomas and metastases to the lung, brain, and other organs were excluded.

Median survival was 34 months among 358 liver-first patients versus 24 months among 18,042 usual care patients in an intention-to-treat analysis. Among patients who completed their resections, median survival was 57 months among 140 liver-first patients versus 36 months with usual care in 3,988.

The benefit held after adjustment for patient and tumor characteristics (hazard ratio for death 0.77 in favor of liver first). When further adjusted for chemotherapy timing, there was a strong trend for liver-first but it was not statistically significant, suggesting that up-front chemotherapy contributed to the results (HR, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.01; P = .09).

There were many caveats. The liver-first patients were younger, with over half under the age of 60 years versus just over 40% in usual care. They were also healthier based on Charlson comorbidity scores and more likely to have upfront chemotherapy and be treated at an academic center.

So, what should surgeons make of these findings? Lead investigator Vadim Kurbatov, MD, a Yale surgery resident, argued that, at the very least, they suggest that liver-first is a viable option for stage IV colon cancer with isolated liver metastases. Going further, they suggest that liver first may be the right way to go for younger, healthier patients at academic centers.

For sicker stage IV patients, however, the role of liver-first is unclear. “We really do need a randomized trial,” he said.

Dr. Kurbatov and Dr. Rafferty had no relevant disclosures to report. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

BOSTON –

It’s an alternative to usual care, meaning simultaneous bowel and liver resection or bowel resection with liver surgery later on.

Systemic chemotherapy comes first, followed by liver resection. If margins are microscopically negative, the patient gets another round of chemotherapy. If no additional lesions emerge, the primary tumor is taken out. The entire process can take up to a year.

The approach was developed in the Netherlands for rectal cancer with advanced liver metastases. The idea was to get the liver lesions out before they became unresectable, then remove the primary tumor later on. It’s gaining traction now for colon cancer, and beginning to trickle into the United States at a few academic medical centers.

It comes down to what’s more dangerous, the metastases or the primary tumor? Tumor science hasn’t answered that question yet. There’s general agreement that metastases are what kill people with cancer, but it’s not known if they come mostly from previous metastases or from the primary tumor. The liver-first approach assumes the former.

Liver-first is “extremely controversial. For older surgeons who are not in tertiary care centers, liver-first doesn’t make sense, and it doesn’t seem to make sense to patients. They wonder why you would go after the liver when they were diagnosed with a colon tumor,” said Janice Rafferty, MD, FACS, professor of surgery at the University of Cincinnati, at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“Well, it’s because the primary tumor doesn’t limit your life,” she continued. “The life-limiting disease is in the liver, not the colon. If you explain it to them that way, it makes sense. If we cannot get an R0 resection on the liver, it doesn’t make sense to go after the primary, unless it’s symptomatic with obstruction, bleeding, or fistula.”

There have been about 10 attempts at a randomized trial of this approach versus usual care, but they were not successful because of the difficulty of recruiting patients. Patients – and no doubt, some surgeons – may have some resistance to the logic of going after metastases first.

Dr. Rafferty moderated a review of research from Yale University, New Haven, Conn., that attempted to plug the evidence gap. The Yale investigators “presented really interesting data that shows that liver-first has improved survival,” she said.

The Yale team used the National Cancer Database to compare 2010-2015 outcomes from liver-first patients with patients who had simultaneous or bowel-first resections, followed by later liver resections. The database didn’t allow them to tease out simultaneous from bowel-first cases, so they lumped them together as usual care. To avoid confounding, rectal carcinomas and metastases to the lung, brain, and other organs were excluded.

Median survival was 34 months among 358 liver-first patients versus 24 months among 18,042 usual care patients in an intention-to-treat analysis. Among patients who completed their resections, median survival was 57 months among 140 liver-first patients versus 36 months with usual care in 3,988.

The benefit held after adjustment for patient and tumor characteristics (hazard ratio for death 0.77 in favor of liver first). When further adjusted for chemotherapy timing, there was a strong trend for liver-first but it was not statistically significant, suggesting that up-front chemotherapy contributed to the results (HR, 0.88; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-1.01; P = .09).

There were many caveats. The liver-first patients were younger, with over half under the age of 60 years versus just over 40% in usual care. They were also healthier based on Charlson comorbidity scores and more likely to have upfront chemotherapy and be treated at an academic center.

So, what should surgeons make of these findings? Lead investigator Vadim Kurbatov, MD, a Yale surgery resident, argued that, at the very least, they suggest that liver-first is a viable option for stage IV colon cancer with isolated liver metastases. Going further, they suggest that liver first may be the right way to go for younger, healthier patients at academic centers.

For sicker stage IV patients, however, the role of liver-first is unclear. “We really do need a randomized trial,” he said.

Dr. Kurbatov and Dr. Rafferty had no relevant disclosures to report. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

REPORTING FROM THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The liver-first approach may be appropriate for younger, healthier patients at academic centers.

Major finding: Median survival was 34 months among 358 liver-first patients versus 24 months among 18,042 usual care patients in an intention-to-treat analysis.

Study details: A review of over 18,000 patients in the National Cancer Database

Disclosures: The lead investigator had no disclosures to report. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Cervical cancer survival higher with open surgery in LACC trial

based on findings from the randomized, controlled phase 3 Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial of more than 600 women.

The alarming findings, which led to early study termination, also were supported by results from a second population-based study. Both studies were published concurrently in the Oct. 31 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The disease-free survival at 4.5 years among 319 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery in the LACC trial was 86.0% vs. 96.5% in 312 patients who underwent open surgery, Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395).

At 3 years, the disease-free survival rates were 91.2% in the minimally invasive surgery group and 97.1% in open surgery group (hazard ratio for disease recurrence or death from cervical cancer, 3.74).

The differences between the groups persisted after adjustment for age, body mass index, disease stage, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph-node involvement. In the minimally invasive surgery group, the findings were comparable for those who underwent laparoscopic vs. robot-assisted surgery, the investigators found.

Further, at 3 years, overall survival was 93.8% vs. 99.0% (HR for death from any cause, 6.00), death from cervical cancer was 4.4% vs. 0.6% (HR, 6.56), and the rate of locoregional recurrence-free survival was 94.3 vs. 98.3 (HR, 4.26) in the minimally invasive and open surgery groups, respectively.

Study participants were women with a mean age of 46 years with stage IA1, IA2, or IB1 cervical cancer, with most (91.9%) having IB1 disease, and either squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma. They were recruited from 33 centers worldwide between June 2008 and June 2017. Most of those assigned to minimally invasive surgery underwent laparoscopic surgery (84.4%), and the remaining patients underwent robot-assisted surgery.

The treatment groups were balanced with respect to baseline characteristics, they noted.

The minimally invasive approach is widely used given that guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society of Gynecological Oncology consider both surgical approaches acceptable, and since retrospective studies suggest laparoscopic radical hysterectomy is associated with lower complication rates and comparable outcomes. However, there are limited prospective data regarding survival outcomes in early stage disease with the two approaches, the researchers said.

“Our results call into question the findings in the literature suggesting that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy is associated with no difference in oncologic outcomes as compared with the open approach,” they wrote, noting that a number of factors may explain the differences, such as concurrent vs. sequential analyses in the current studies vs. prior studies (in sequential analyses, earlier procedures may have been performed under broader indications and less clearly defined radiotherapy guidelines), and the possibility that “routine use of a uterine manipulator might increase the propensity for tumor spillage” in minimally invasive surgery.

Strengths of the study include its prospective, randomized, international multicenter design and inclusion of a per-protocol analysis that was consistent with the intention-to-treat analysis, and limitations include the fact that intended enrollment wasn’t reached because of the “safety alert raised by the data and safety monitoring committee on the basis of the higher recurrence and death in the minimally invasive surgery groups,” as well as the inability to generalize the results to patients with low-risk disease as there was lack of power to evaluate outcomes in that context.

Even though the trial was initially powered on the assumption that there would be a 4.5 year follow-up for all patients, only 59.7% reached that length of follow-up. However, the trial still reached 84% power to detect noninferiority of the primary outcome (disease-free survival) with minimally invasive surgery, which was not found, they noted.

Similarly, in the population-based cohort study of 2,461 women who underwent radical hysterectomy for stage IA2 of IB1 cervical cancer between 2010 and 2013, 4-year mortality was 9.1% among 1,225 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery vs. 5.3% among the 1,236 patients who underwent open surgery (HR, 1.65), Alexander Melamed, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804923).

Of note, the 4-year relative survival rate following radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer remained stable prior to the widespread adoption of minimally invasive approaches; an interrupted time-series analysis involving women who underwent surgery during 2000-2010, which was also conducted as part of the study, showed a decline in 4-year survival of 0.8% per year after 2006, coinciding with increased use of minimally invasive surgery, the investigators said.

For the main patient-level analysis, the researchers used the National Cancer Database, and for the time-series analysis they used information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program database.

“Our findings suggest that minimally invasive surgery was associated with a higher risk of death than open surgery among women who underwent radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This association was apparent regardless of laparoscopic approach, tumor size, or histologic type,” they concluded.

The findings are unexpected, eye-opening, and should inform practice, according to Ritu Salani, MD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus.

“This is something we have to discuss with patients,” she said in an interview, noting that while these aren’t perfect studies, they “are the best information we have.

Data reported in September at a meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society show that surgical complications and quality of life outcomes are similar with minimally invasive and open surgery, therefore the findings from these two new studies suggest a need to shift back toward open surgery for patients with cervical cancer, she said.

One “catch” is that survival in the open surgery group in the LACC trial was unusually high and recurrence rates unusually low, compared with what might be expected, and the explanation for this observation is unclear.

“There may be some missing pieces that they haven’t been able to explain, but it’s not clear that they would change the outcome,” she said.

Justin Chura, MD, director of gynecologic oncology and robotic surgery at Cancer Treatment Center of America’s Eastern Regional Medical Center in Philadelphia, said in an interview, “The results of the study by Ramirez et al. are certainly disappointing for those among us who are advocates of minimally invasive surgery (MIS). In my own practice, I transitioned to minimally invasive radical hysterectomy approximately 10 years ago. Now that approach has to be reconsidered. While there are likely subsets of patients who will still benefit from a MIS approach without worsening oncologic outcomes, we do not have robust data to reliably identify those patients.

“One factor that warrants further investigation is the use of a uterine manipulator. While I do not use a manipulator out of personal preference (one less step in the operating room), the idea of placing a device through the tumor or adjacent to it, has biologic plausibility in terms of displacing tumor cells into lymphatic channels,” he said. “Until we have more data, an open approach appears to be preferred.”*

Dr. Ramirez and Dr. Melamed each reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Salani and Dr. Chura are members of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial board, but reported having no other relevant disclosures.*

SOURCE: Ramirez P. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395.

*This article was updated 11/9/2018.

The findings by Ramirez et al. and Melamed et al. are striking in part because previous studies focused more on surgical than clinical outcomes.

They are powerful, but scientific scrutiny demands consideration of potential study-design or study-conduct issues. For example, all cancer recurrences in the LACC trial were clustered at 14 of 33 participating centers, raising questions about factors that contributed to recurrence at those centers .

Still, the findings are alarming and deal a blow to the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches in cervical cancer patients. They don’t necessarily “signal the death knell” of such approaches.

Select patients may still benefit from a less invasive approach; none of the patients with stage lA2 disease, and only one with stage lB1, grade 1 disease had a recurrence in the LACC trial.

Further, patients with tumors smaller than 2 cm also did not have worse outcomes with minimally invasive surgery in either study. However, until further details are known, surgeons should proceed cautiously and counsel patients regarding these study results.

Amanda N. Fader, MD , made her comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395 ). Dr. Fader is with the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She reported having no relevant disclosures.

The findings by Ramirez et al. and Melamed et al. are striking in part because previous studies focused more on surgical than clinical outcomes.

They are powerful, but scientific scrutiny demands consideration of potential study-design or study-conduct issues. For example, all cancer recurrences in the LACC trial were clustered at 14 of 33 participating centers, raising questions about factors that contributed to recurrence at those centers .

Still, the findings are alarming and deal a blow to the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches in cervical cancer patients. They don’t necessarily “signal the death knell” of such approaches.

Select patients may still benefit from a less invasive approach; none of the patients with stage lA2 disease, and only one with stage lB1, grade 1 disease had a recurrence in the LACC trial.

Further, patients with tumors smaller than 2 cm also did not have worse outcomes with minimally invasive surgery in either study. However, until further details are known, surgeons should proceed cautiously and counsel patients regarding these study results.

Amanda N. Fader, MD , made her comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395 ). Dr. Fader is with the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She reported having no relevant disclosures.

The findings by Ramirez et al. and Melamed et al. are striking in part because previous studies focused more on surgical than clinical outcomes.

They are powerful, but scientific scrutiny demands consideration of potential study-design or study-conduct issues. For example, all cancer recurrences in the LACC trial were clustered at 14 of 33 participating centers, raising questions about factors that contributed to recurrence at those centers .

Still, the findings are alarming and deal a blow to the use of minimally invasive surgical approaches in cervical cancer patients. They don’t necessarily “signal the death knell” of such approaches.

Select patients may still benefit from a less invasive approach; none of the patients with stage lA2 disease, and only one with stage lB1, grade 1 disease had a recurrence in the LACC trial.

Further, patients with tumors smaller than 2 cm also did not have worse outcomes with minimally invasive surgery in either study. However, until further details are known, surgeons should proceed cautiously and counsel patients regarding these study results.

Amanda N. Fader, MD , made her comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395 ). Dr. Fader is with the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. She reported having no relevant disclosures.

based on findings from the randomized, controlled phase 3 Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial of more than 600 women.

The alarming findings, which led to early study termination, also were supported by results from a second population-based study. Both studies were published concurrently in the Oct. 31 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The disease-free survival at 4.5 years among 319 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery in the LACC trial was 86.0% vs. 96.5% in 312 patients who underwent open surgery, Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395).

At 3 years, the disease-free survival rates were 91.2% in the minimally invasive surgery group and 97.1% in open surgery group (hazard ratio for disease recurrence or death from cervical cancer, 3.74).

The differences between the groups persisted after adjustment for age, body mass index, disease stage, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph-node involvement. In the minimally invasive surgery group, the findings were comparable for those who underwent laparoscopic vs. robot-assisted surgery, the investigators found.

Further, at 3 years, overall survival was 93.8% vs. 99.0% (HR for death from any cause, 6.00), death from cervical cancer was 4.4% vs. 0.6% (HR, 6.56), and the rate of locoregional recurrence-free survival was 94.3 vs. 98.3 (HR, 4.26) in the minimally invasive and open surgery groups, respectively.

Study participants were women with a mean age of 46 years with stage IA1, IA2, or IB1 cervical cancer, with most (91.9%) having IB1 disease, and either squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma. They were recruited from 33 centers worldwide between June 2008 and June 2017. Most of those assigned to minimally invasive surgery underwent laparoscopic surgery (84.4%), and the remaining patients underwent robot-assisted surgery.

The treatment groups were balanced with respect to baseline characteristics, they noted.

The minimally invasive approach is widely used given that guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society of Gynecological Oncology consider both surgical approaches acceptable, and since retrospective studies suggest laparoscopic radical hysterectomy is associated with lower complication rates and comparable outcomes. However, there are limited prospective data regarding survival outcomes in early stage disease with the two approaches, the researchers said.

“Our results call into question the findings in the literature suggesting that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy is associated with no difference in oncologic outcomes as compared with the open approach,” they wrote, noting that a number of factors may explain the differences, such as concurrent vs. sequential analyses in the current studies vs. prior studies (in sequential analyses, earlier procedures may have been performed under broader indications and less clearly defined radiotherapy guidelines), and the possibility that “routine use of a uterine manipulator might increase the propensity for tumor spillage” in minimally invasive surgery.

Strengths of the study include its prospective, randomized, international multicenter design and inclusion of a per-protocol analysis that was consistent with the intention-to-treat analysis, and limitations include the fact that intended enrollment wasn’t reached because of the “safety alert raised by the data and safety monitoring committee on the basis of the higher recurrence and death in the minimally invasive surgery groups,” as well as the inability to generalize the results to patients with low-risk disease as there was lack of power to evaluate outcomes in that context.

Even though the trial was initially powered on the assumption that there would be a 4.5 year follow-up for all patients, only 59.7% reached that length of follow-up. However, the trial still reached 84% power to detect noninferiority of the primary outcome (disease-free survival) with minimally invasive surgery, which was not found, they noted.

Similarly, in the population-based cohort study of 2,461 women who underwent radical hysterectomy for stage IA2 of IB1 cervical cancer between 2010 and 2013, 4-year mortality was 9.1% among 1,225 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery vs. 5.3% among the 1,236 patients who underwent open surgery (HR, 1.65), Alexander Melamed, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804923).

Of note, the 4-year relative survival rate following radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer remained stable prior to the widespread adoption of minimally invasive approaches; an interrupted time-series analysis involving women who underwent surgery during 2000-2010, which was also conducted as part of the study, showed a decline in 4-year survival of 0.8% per year after 2006, coinciding with increased use of minimally invasive surgery, the investigators said.

For the main patient-level analysis, the researchers used the National Cancer Database, and for the time-series analysis they used information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program database.

“Our findings suggest that minimally invasive surgery was associated with a higher risk of death than open surgery among women who underwent radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This association was apparent regardless of laparoscopic approach, tumor size, or histologic type,” they concluded.

The findings are unexpected, eye-opening, and should inform practice, according to Ritu Salani, MD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus.

“This is something we have to discuss with patients,” she said in an interview, noting that while these aren’t perfect studies, they “are the best information we have.

Data reported in September at a meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society show that surgical complications and quality of life outcomes are similar with minimally invasive and open surgery, therefore the findings from these two new studies suggest a need to shift back toward open surgery for patients with cervical cancer, she said.

One “catch” is that survival in the open surgery group in the LACC trial was unusually high and recurrence rates unusually low, compared with what might be expected, and the explanation for this observation is unclear.

“There may be some missing pieces that they haven’t been able to explain, but it’s not clear that they would change the outcome,” she said.

Justin Chura, MD, director of gynecologic oncology and robotic surgery at Cancer Treatment Center of America’s Eastern Regional Medical Center in Philadelphia, said in an interview, “The results of the study by Ramirez et al. are certainly disappointing for those among us who are advocates of minimally invasive surgery (MIS). In my own practice, I transitioned to minimally invasive radical hysterectomy approximately 10 years ago. Now that approach has to be reconsidered. While there are likely subsets of patients who will still benefit from a MIS approach without worsening oncologic outcomes, we do not have robust data to reliably identify those patients.

“One factor that warrants further investigation is the use of a uterine manipulator. While I do not use a manipulator out of personal preference (one less step in the operating room), the idea of placing a device through the tumor or adjacent to it, has biologic plausibility in terms of displacing tumor cells into lymphatic channels,” he said. “Until we have more data, an open approach appears to be preferred.”*

Dr. Ramirez and Dr. Melamed each reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Salani and Dr. Chura are members of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial board, but reported having no other relevant disclosures.*

SOURCE: Ramirez P. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395.

*This article was updated 11/9/2018.

based on findings from the randomized, controlled phase 3 Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial of more than 600 women.

The alarming findings, which led to early study termination, also were supported by results from a second population-based study. Both studies were published concurrently in the Oct. 31 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The disease-free survival at 4.5 years among 319 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery in the LACC trial was 86.0% vs. 96.5% in 312 patients who underwent open surgery, Pedro T. Ramirez, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395).

At 3 years, the disease-free survival rates were 91.2% in the minimally invasive surgery group and 97.1% in open surgery group (hazard ratio for disease recurrence or death from cervical cancer, 3.74).

The differences between the groups persisted after adjustment for age, body mass index, disease stage, lymphovascular invasion, and lymph-node involvement. In the minimally invasive surgery group, the findings were comparable for those who underwent laparoscopic vs. robot-assisted surgery, the investigators found.

Further, at 3 years, overall survival was 93.8% vs. 99.0% (HR for death from any cause, 6.00), death from cervical cancer was 4.4% vs. 0.6% (HR, 6.56), and the rate of locoregional recurrence-free survival was 94.3 vs. 98.3 (HR, 4.26) in the minimally invasive and open surgery groups, respectively.

Study participants were women with a mean age of 46 years with stage IA1, IA2, or IB1 cervical cancer, with most (91.9%) having IB1 disease, and either squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma. They were recruited from 33 centers worldwide between June 2008 and June 2017. Most of those assigned to minimally invasive surgery underwent laparoscopic surgery (84.4%), and the remaining patients underwent robot-assisted surgery.

The treatment groups were balanced with respect to baseline characteristics, they noted.

The minimally invasive approach is widely used given that guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society of Gynecological Oncology consider both surgical approaches acceptable, and since retrospective studies suggest laparoscopic radical hysterectomy is associated with lower complication rates and comparable outcomes. However, there are limited prospective data regarding survival outcomes in early stage disease with the two approaches, the researchers said.

“Our results call into question the findings in the literature suggesting that minimally invasive radical hysterectomy is associated with no difference in oncologic outcomes as compared with the open approach,” they wrote, noting that a number of factors may explain the differences, such as concurrent vs. sequential analyses in the current studies vs. prior studies (in sequential analyses, earlier procedures may have been performed under broader indications and less clearly defined radiotherapy guidelines), and the possibility that “routine use of a uterine manipulator might increase the propensity for tumor spillage” in minimally invasive surgery.

Strengths of the study include its prospective, randomized, international multicenter design and inclusion of a per-protocol analysis that was consistent with the intention-to-treat analysis, and limitations include the fact that intended enrollment wasn’t reached because of the “safety alert raised by the data and safety monitoring committee on the basis of the higher recurrence and death in the minimally invasive surgery groups,” as well as the inability to generalize the results to patients with low-risk disease as there was lack of power to evaluate outcomes in that context.

Even though the trial was initially powered on the assumption that there would be a 4.5 year follow-up for all patients, only 59.7% reached that length of follow-up. However, the trial still reached 84% power to detect noninferiority of the primary outcome (disease-free survival) with minimally invasive surgery, which was not found, they noted.

Similarly, in the population-based cohort study of 2,461 women who underwent radical hysterectomy for stage IA2 of IB1 cervical cancer between 2010 and 2013, 4-year mortality was 9.1% among 1,225 patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery vs. 5.3% among the 1,236 patients who underwent open surgery (HR, 1.65), Alexander Melamed, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his colleagues reported (N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804923).

Of note, the 4-year relative survival rate following radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer remained stable prior to the widespread adoption of minimally invasive approaches; an interrupted time-series analysis involving women who underwent surgery during 2000-2010, which was also conducted as part of the study, showed a decline in 4-year survival of 0.8% per year after 2006, coinciding with increased use of minimally invasive surgery, the investigators said.

For the main patient-level analysis, the researchers used the National Cancer Database, and for the time-series analysis they used information from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program database.

“Our findings suggest that minimally invasive surgery was associated with a higher risk of death than open surgery among women who underwent radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This association was apparent regardless of laparoscopic approach, tumor size, or histologic type,” they concluded.

The findings are unexpected, eye-opening, and should inform practice, according to Ritu Salani, MD, of the Ohio State University, Columbus.

“This is something we have to discuss with patients,” she said in an interview, noting that while these aren’t perfect studies, they “are the best information we have.

Data reported in September at a meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society show that surgical complications and quality of life outcomes are similar with minimally invasive and open surgery, therefore the findings from these two new studies suggest a need to shift back toward open surgery for patients with cervical cancer, she said.

One “catch” is that survival in the open surgery group in the LACC trial was unusually high and recurrence rates unusually low, compared with what might be expected, and the explanation for this observation is unclear.

“There may be some missing pieces that they haven’t been able to explain, but it’s not clear that they would change the outcome,” she said.

Justin Chura, MD, director of gynecologic oncology and robotic surgery at Cancer Treatment Center of America’s Eastern Regional Medical Center in Philadelphia, said in an interview, “The results of the study by Ramirez et al. are certainly disappointing for those among us who are advocates of minimally invasive surgery (MIS). In my own practice, I transitioned to minimally invasive radical hysterectomy approximately 10 years ago. Now that approach has to be reconsidered. While there are likely subsets of patients who will still benefit from a MIS approach without worsening oncologic outcomes, we do not have robust data to reliably identify those patients.

“One factor that warrants further investigation is the use of a uterine manipulator. While I do not use a manipulator out of personal preference (one less step in the operating room), the idea of placing a device through the tumor or adjacent to it, has biologic plausibility in terms of displacing tumor cells into lymphatic channels,” he said. “Until we have more data, an open approach appears to be preferred.”*

Dr. Ramirez and Dr. Melamed each reported having no relevant disclosures. Dr. Salani and Dr. Chura are members of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial board, but reported having no other relevant disclosures.*

SOURCE: Ramirez P. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395.

*This article was updated 11/9/2018.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Cervical cancer recurrence and survival rates were worse with minimally invasive vs. open surgery in a prospective study.

Major finding: Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with minimally invasive vs. 96.5% with open surgery.

Study details: The phase 3 LACC trial of more than 600 women with cervical cancer, and a population based study of nearly 2,500 women with cervical cancer.