User login

Screening for hepatitis B: Where the CDC and USPSTF diverge

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published new recommendations on screening for hepatitis B infection.1 They recommend screening all adults (ages 18 years and older) at least once.

These recommendations differ in a few ways from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).2 This Practice Alert will highlight these differences but also point out areas of agreement between the 2 sets of recommendations—and discuss why 2 separate agencies in the US Department of Health and Human Services reached different conclusions on some issues.

First, some background on hepatitis B

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million people in the United States have chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection—and as many as two-thirds are unaware of it.3 In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services published the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States with a stated goal of increasing awareness of infection status among those with hepatitis B virus (HBV) from 32% to 90% by 2030.4 People living in the United States but born outside the country are at highest risk for CHB; they account for 69% of those with the infection.5

The incidence of acute HBV infection has declined markedly since the HBV vaccine was recommended for high-risk adults in 1982 and universally for infants in 1991.6,7 Overall rates of HBV infection declined fairly steadily starting around 1987—but in 2014, rates began to increase, especially in those ages 40 to 59 years.8,9 In 2019, 3192 cases were reported; but when one factors in underreporting, the CDC estimates that the number is likely closer to 20,700.10 This uptick is one reason the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices changed its HBV vaccination recommendation for adults from a risk-based to a universal recommendation for all unvaccinated adults through age 60 years.10

Chronic hepatitis B infection has serious consequences

The proportion of those infected with HBV who develop CHB differs by age at infection: 80% to 90% if infected during infancy, 30% if infected before age 6 years, and 1% to 12% if infected as an older child or adult.8

CHB infection can lead to chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, and liver failure. About 25% of those who develop CHB infection during childhood and 15% of those who develop chronic infection after childhood will die prematurely from cirrhosis or liver cancer.8

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) classifies CHB into 4 phases that reflect the rate of viral replication and the patient’s immune response.11 These phases are:

- immune-tolerant (minimal inflammation and fibrosis)

- hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)-positive immune-active (moderate-to-severe inflammation or fibrosis)

- inactive CHB (minimal necroinflammation but variable fibrosis), and

- HBeAg-negative immune reactivation (moderate-to-severe inflammation or fibrosis).11

Continue to: The progression from one phase...

The progression from one phase to the next varies by patient, and not all patients will progress through each phase. The AASLD recommends periodically monitoring the HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in those with CHB to track the progression from one phase to the next and to guide treatment decisions.

Treatment can be beneficial for those who meet criteria

The evidence report prepared for USPSTF found that antiviral treatment of those with CHB infection resulted in improved intermediate outcomes (histologic improvement, loss of hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg], loss of HBeAg, HBeAg seroconversion, virologic suppression, and normalization of ALT levels). The magnitude of benefit varied by location and study design.12

In addition, the evidence review found that antiviral therapy was associated with a decreased risk for overall mortality (relative risk [RR] = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03-0.69), cirrhosis (RR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.29-1.77), and hepatocellular carcinoma (RR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.16-2.33). However, these results came from studies that were “limited due to small numbers of trials, few events, and insufficient duration of follow-up.”12

The USPSTF and the CDC both judged that the intermediate outcome results, as well as findings that improved intermediate outcomes lead to decreases in chronic liver disease, are strong enough evidence for their recommendations.

However, not all patients with CHB infection require treatment; estimates of patients with HBV infection meeting AASLD criteria for treatment range from 24% to 48%.1 The AASLD guideline on the treatment of CHB infection is an excellent resource that makes recommendations on the initial evaluation, ongoing monitoring, and treatment decisions for those with CHB.11

Continue to: How CDC and USPSTF guidance on HBV screeinng differs

How CDC and USPSTF guidance on HBV screening differs

The CDC and USPSTF recommendations for HBV screening differ in 3 aspects: whom to screen, whom to classify as at high risk for HBV infection, and what tests to use for screening.

Who should be screened?

The USPSTF recommends screening adults and adolescents who are at high risk for HBV. The CDC recommends screening all adults at least once. Both entities agree that those who are at increased risk should be screened periodically, although the optimal frequency has not been established. The USPSTF does not recommend against screening for the general population, so universal screening (as advocated by the CDC) is not in direct conflict with the USPSTF’s recommendations.

Who is at increased risk for HBV infection?

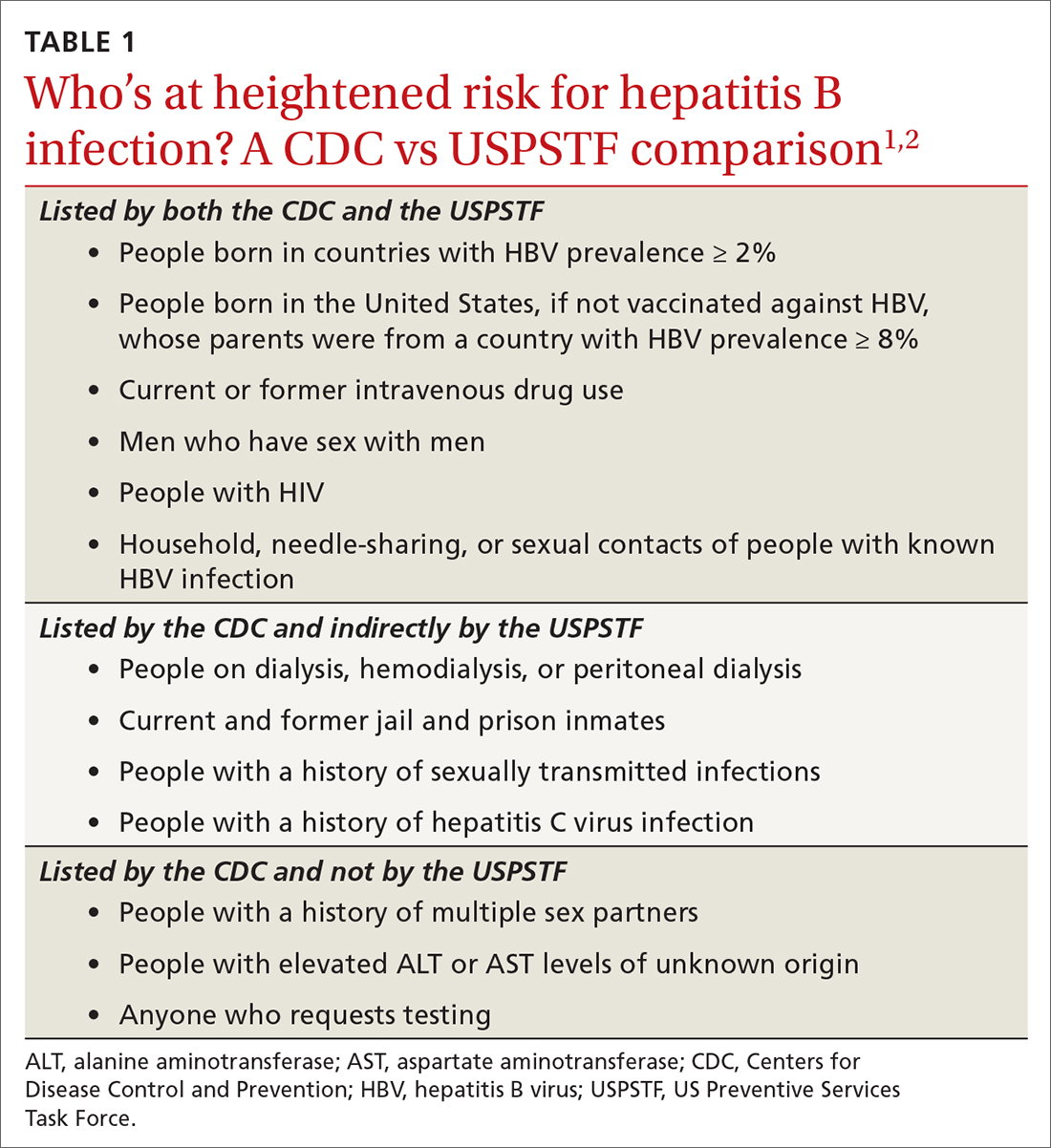

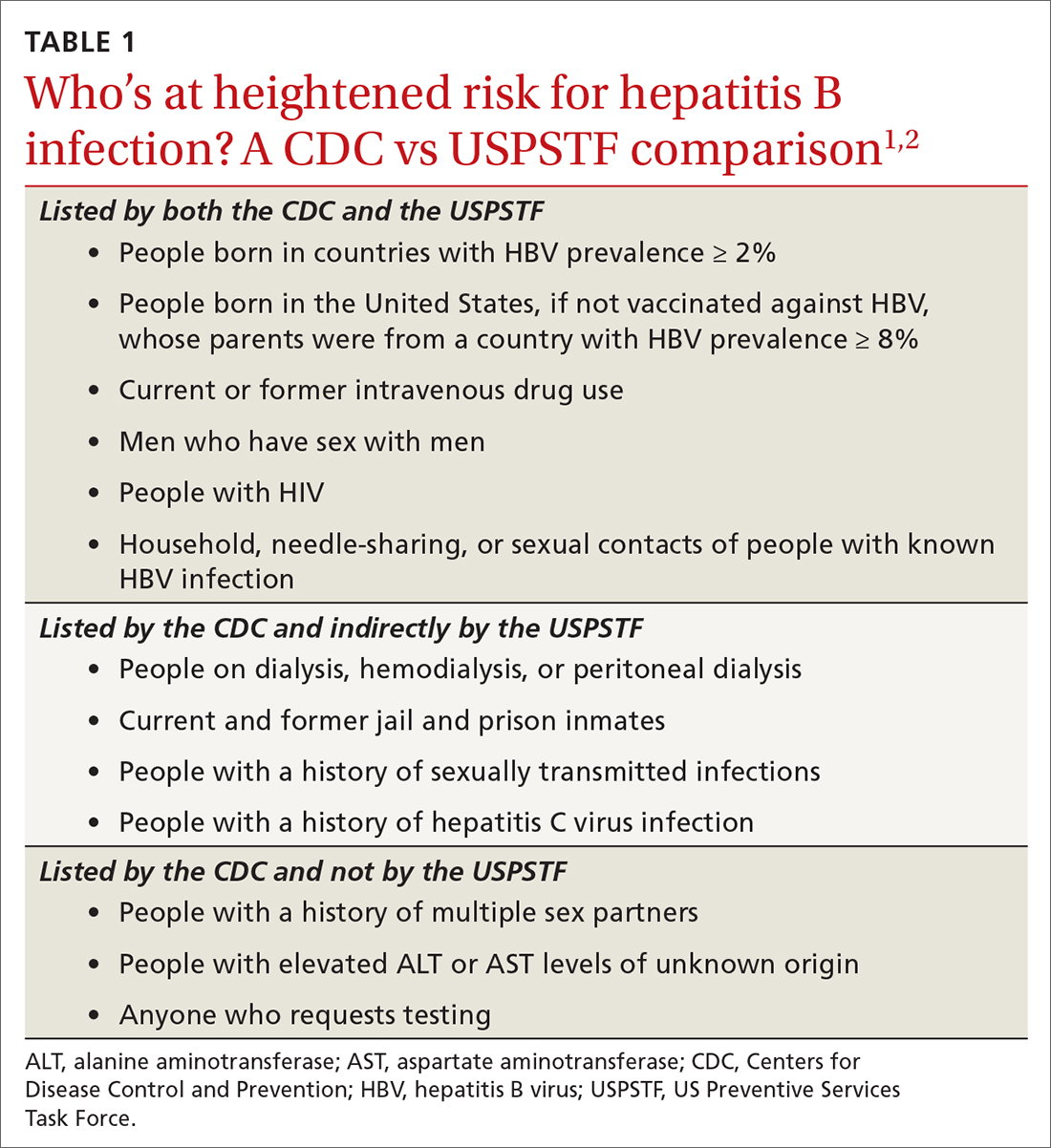

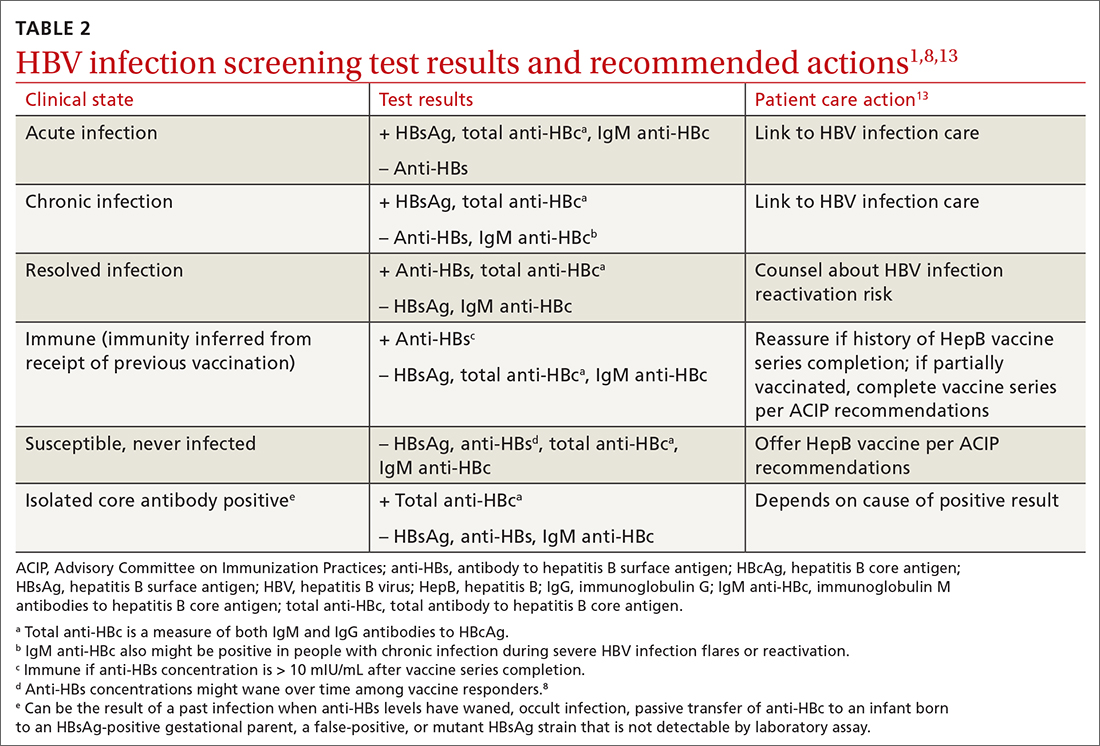

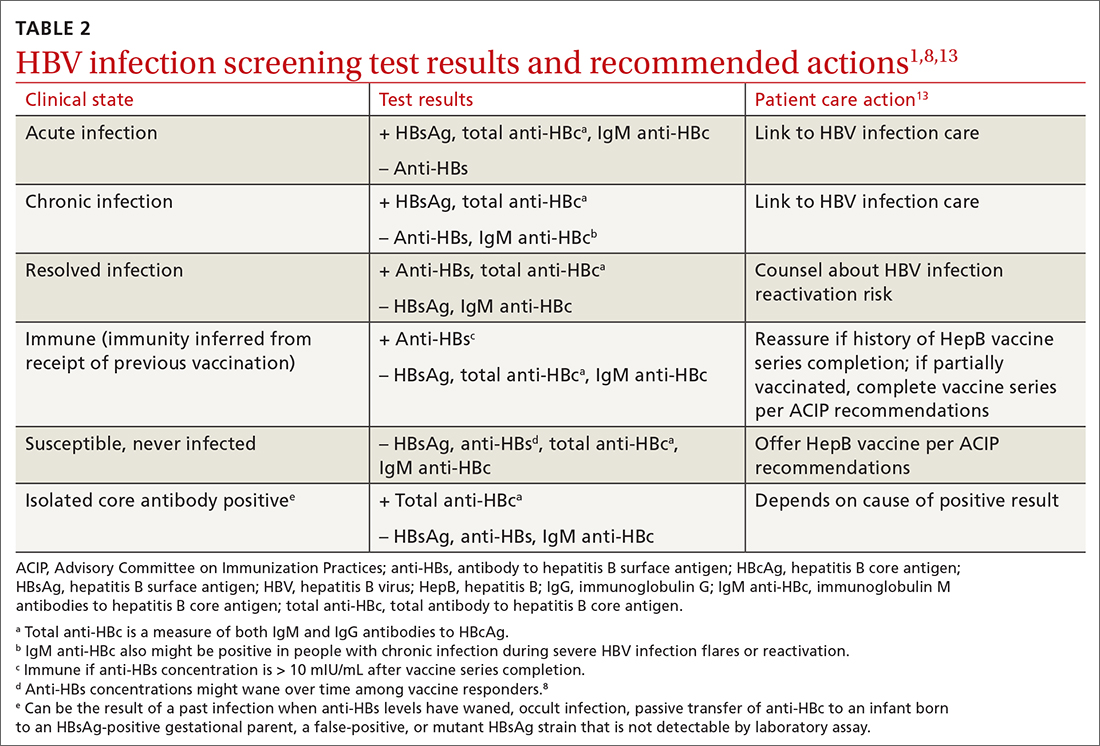

The CDC and the USPSTF differ slightly on the factors they consider to constitute increased risk for HBV infection. These are listed in TABLE 1.1,2

The CDC lists 6 categories that the USPSTF does not mention. However, 4 of these categories are mentioned indirectly in the USPSTF evidence report that accompanies the recommendations, via statements that certain settings have high proportions of people at risk for HBV infection: sexually transmitted infection clinics; HIV testing and treatment centers; health care settings that target services toward people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men; correctional facilities; hemodialysis facilities; and institutions and nonresidential daycare centers for developmentally disabled persons. People who are served at most of these facilities are also at risk for hepatitis C virus infection.

Three categories are listed by the CDC and not by the USPSTF, in either the recommendation or evidence report. These include a history of multiple sex partners; elevated ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels of unknown origin; and patient request for testing (because they may not want to reveal risk factors).

Continue to: What test(s) should be ordered?

What test(s) should be ordered?

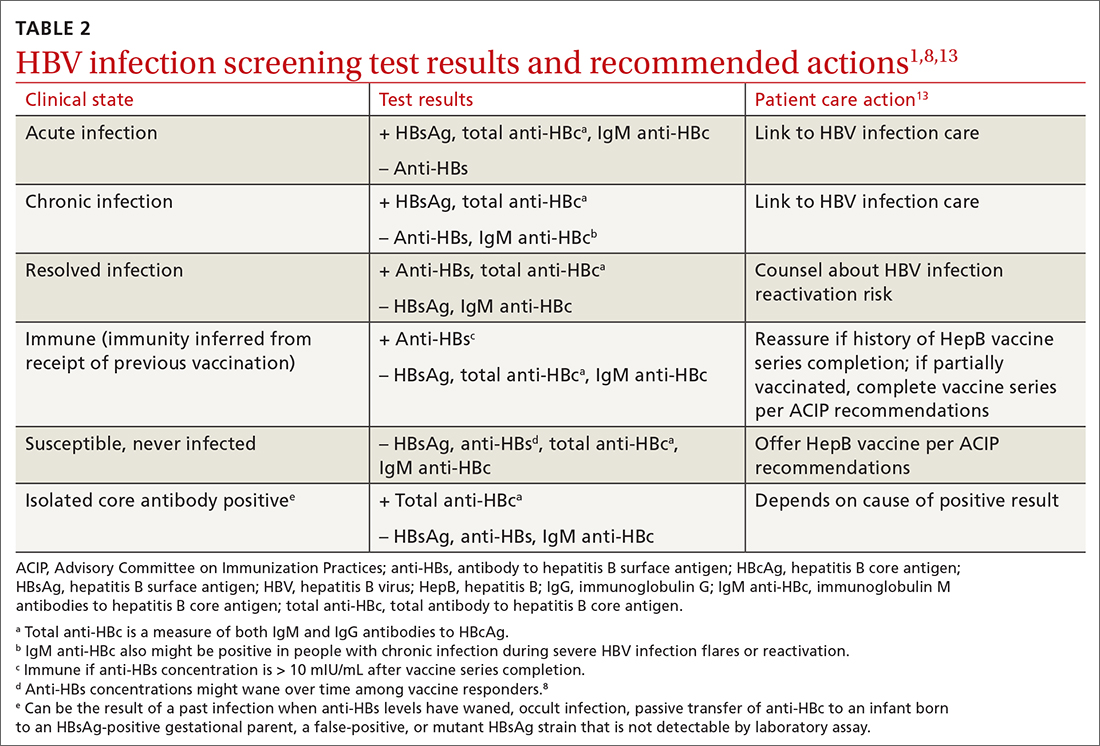

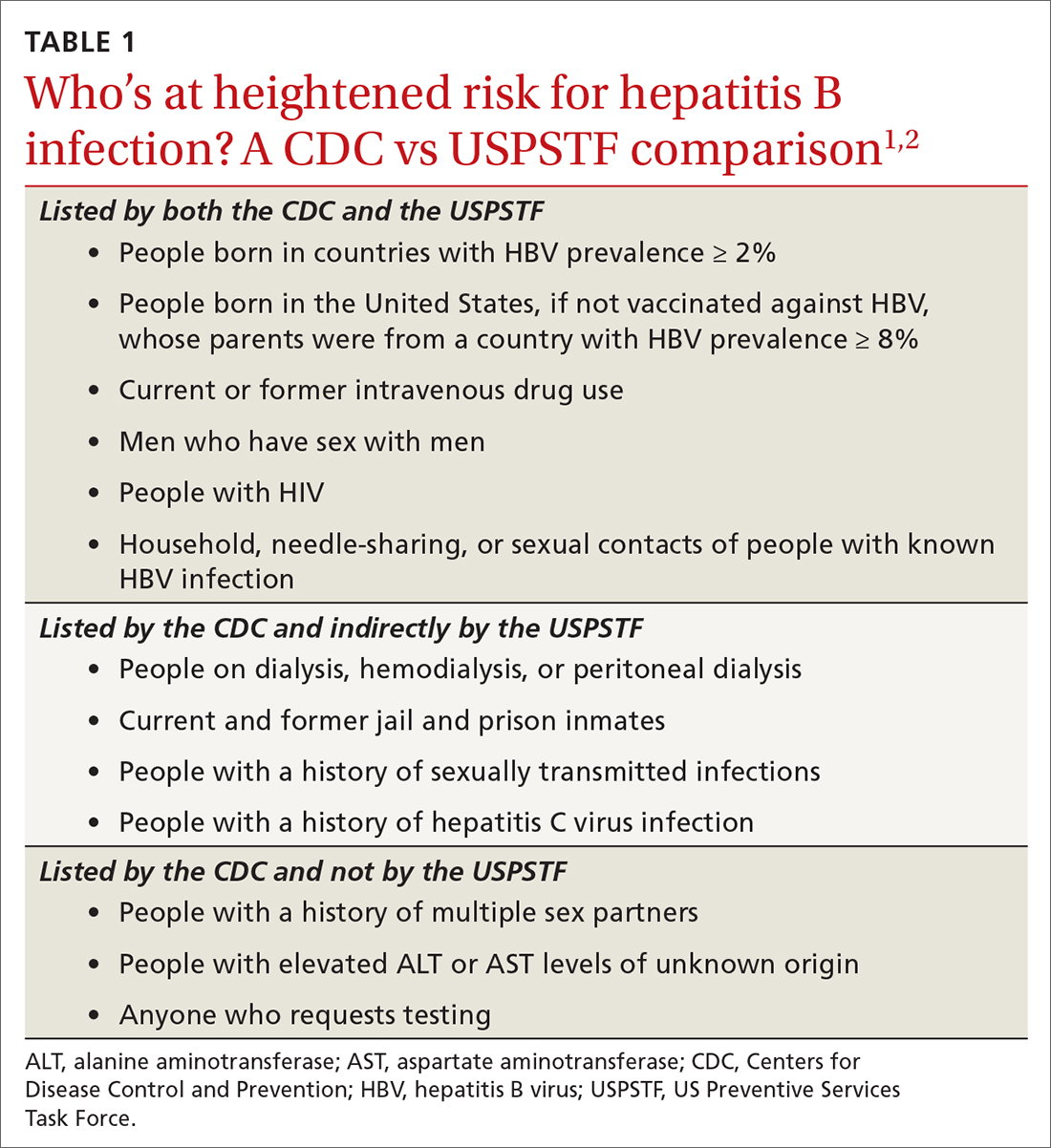

The USPSTF recommends screening using HBsAg. The CDC recommends using triple-panel screening: HBsAg, anti-hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), and total antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc).

HBsAg indicates HBV infection, either acute or chronic, or a recent dose of HBV vaccine. Anti-HBs indicate recovery from HBV infection, response to HBV vaccine, or recent receipt of hepatitis B immune globulin. Total anti-HBc develops in all HBV infections, resolved or current, and usually persists for life. Vaccine-induced immunity does not cause anti-HBc to develop.

The USPSTF’s rationale is that testing for HBsAg is more than 98% sensitive and specific for detecting HBV infections.2 The CDC recommends triple testing because it can detect those with asymptomatic active HBV infections (this would be a rare occurrence); those who have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (eg, those who are immunosuppressed); and those who are susceptible and need vaccination.

Interpretation of HBV test results and suggested actions are described in TABLE 2.1,8,13

Why do the CDC and USPSTF differ?

While it would be optimal if the CDC and the USPSTF coordinated and harmonized recommendations, this is difficult to achieve given their different missions. The USPSTF is charged to make evidence-based recommendations about preventive services such as screenings, behavioral counseling, and preventive medications, which are provided by clinicians to individual patients. The Task Force uses a very strict evidence-based process and will not make recommendations unless there is adequate evidence of efficacy and safety. Members of the Task Force are primary care professionals, and their collaborating professional organizations are primary care focused.

The CDC takes a community-wide, public health perspective. The professionals that work there are not always clinicians. They strive to prevent as much illness as possible, using public health measures and making recommendations to clinicians. They collaborate with professional organizations; on topics such as hepatitis and other infectious diseases, they collaborate with specialty-oriented societies. Given the imperative to act with the best evidence available, their evidence assessment process is not as strict.

The result, at times, is slight differences in recommendations. However, the HBV screening recommendations from the CDC and the USPSTF agree more than they do not. Based on practice-specific characteristics, family physicians should decide if they want to screen all adults or only those at increased risk, and whether to use single- or triple-test screening.

1. Conners EE, Panagiotakopoulos L, Hofmeister MG, et al. Screening and testing for hepatitis B virus infection: CDC recommendations—United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72:1-25. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7201a1

2. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published December 15, 2020. Access June 21, 2023. www.uspreventiveser vicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

3. Roberts H, Ly KN, Yin S, et al. Prevalence of HBV infection, vaccine-induced immunity, and susceptibility among at-risk populations: US households, 2013-2018. Hepatology. 2021;74:2353-2365. doi: 10.1002/hep.31991

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Viral hepatitis national strategic plan for the United States: a roadmap to elimination (2021-2025). Published January 7, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2023. www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Viral-Hepatitis-National-Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf

5. Wong RJ, Brosgart CL, Welch S, et al. An updated assessment of chronic hepatitis B prevalence among foreign-born persons living in the United States. Hepatology. 2021;74:607-626. doi: 10.1002/hep.31782

6. CDC. Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP): inactivated hepatitis B virus vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:317-318, 327-288.

7. CDC. Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination: recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:1-25.

8. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1

9. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance 2019. Published July 2021. Accessed June 29, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/

10. Weng MK, Doshani M, Khan MA, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19-59 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:477-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a1

11. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261-283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156

12. Chou R, Blazina I, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020;324:2423-2436. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19750

13. Abara WE, Qaseem A, Schillie S, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination, screening, and linkage to care: best practice advice from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:794-804. doi: 10.7326/M17-110

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published new recommendations on screening for hepatitis B infection.1 They recommend screening all adults (ages 18 years and older) at least once.

These recommendations differ in a few ways from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).2 This Practice Alert will highlight these differences but also point out areas of agreement between the 2 sets of recommendations—and discuss why 2 separate agencies in the US Department of Health and Human Services reached different conclusions on some issues.

First, some background on hepatitis B

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million people in the United States have chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection—and as many as two-thirds are unaware of it.3 In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services published the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States with a stated goal of increasing awareness of infection status among those with hepatitis B virus (HBV) from 32% to 90% by 2030.4 People living in the United States but born outside the country are at highest risk for CHB; they account for 69% of those with the infection.5

The incidence of acute HBV infection has declined markedly since the HBV vaccine was recommended for high-risk adults in 1982 and universally for infants in 1991.6,7 Overall rates of HBV infection declined fairly steadily starting around 1987—but in 2014, rates began to increase, especially in those ages 40 to 59 years.8,9 In 2019, 3192 cases were reported; but when one factors in underreporting, the CDC estimates that the number is likely closer to 20,700.10 This uptick is one reason the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices changed its HBV vaccination recommendation for adults from a risk-based to a universal recommendation for all unvaccinated adults through age 60 years.10

Chronic hepatitis B infection has serious consequences

The proportion of those infected with HBV who develop CHB differs by age at infection: 80% to 90% if infected during infancy, 30% if infected before age 6 years, and 1% to 12% if infected as an older child or adult.8

CHB infection can lead to chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, and liver failure. About 25% of those who develop CHB infection during childhood and 15% of those who develop chronic infection after childhood will die prematurely from cirrhosis or liver cancer.8

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) classifies CHB into 4 phases that reflect the rate of viral replication and the patient’s immune response.11 These phases are:

- immune-tolerant (minimal inflammation and fibrosis)

- hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)-positive immune-active (moderate-to-severe inflammation or fibrosis)

- inactive CHB (minimal necroinflammation but variable fibrosis), and

- HBeAg-negative immune reactivation (moderate-to-severe inflammation or fibrosis).11

Continue to: The progression from one phase...

The progression from one phase to the next varies by patient, and not all patients will progress through each phase. The AASLD recommends periodically monitoring the HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in those with CHB to track the progression from one phase to the next and to guide treatment decisions.

Treatment can be beneficial for those who meet criteria

The evidence report prepared for USPSTF found that antiviral treatment of those with CHB infection resulted in improved intermediate outcomes (histologic improvement, loss of hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg], loss of HBeAg, HBeAg seroconversion, virologic suppression, and normalization of ALT levels). The magnitude of benefit varied by location and study design.12

In addition, the evidence review found that antiviral therapy was associated with a decreased risk for overall mortality (relative risk [RR] = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03-0.69), cirrhosis (RR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.29-1.77), and hepatocellular carcinoma (RR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.16-2.33). However, these results came from studies that were “limited due to small numbers of trials, few events, and insufficient duration of follow-up.”12

The USPSTF and the CDC both judged that the intermediate outcome results, as well as findings that improved intermediate outcomes lead to decreases in chronic liver disease, are strong enough evidence for their recommendations.

However, not all patients with CHB infection require treatment; estimates of patients with HBV infection meeting AASLD criteria for treatment range from 24% to 48%.1 The AASLD guideline on the treatment of CHB infection is an excellent resource that makes recommendations on the initial evaluation, ongoing monitoring, and treatment decisions for those with CHB.11

Continue to: How CDC and USPSTF guidance on HBV screeinng differs

How CDC and USPSTF guidance on HBV screening differs

The CDC and USPSTF recommendations for HBV screening differ in 3 aspects: whom to screen, whom to classify as at high risk for HBV infection, and what tests to use for screening.

Who should be screened?

The USPSTF recommends screening adults and adolescents who are at high risk for HBV. The CDC recommends screening all adults at least once. Both entities agree that those who are at increased risk should be screened periodically, although the optimal frequency has not been established. The USPSTF does not recommend against screening for the general population, so universal screening (as advocated by the CDC) is not in direct conflict with the USPSTF’s recommendations.

Who is at increased risk for HBV infection?

The CDC and the USPSTF differ slightly on the factors they consider to constitute increased risk for HBV infection. These are listed in TABLE 1.1,2

The CDC lists 6 categories that the USPSTF does not mention. However, 4 of these categories are mentioned indirectly in the USPSTF evidence report that accompanies the recommendations, via statements that certain settings have high proportions of people at risk for HBV infection: sexually transmitted infection clinics; HIV testing and treatment centers; health care settings that target services toward people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men; correctional facilities; hemodialysis facilities; and institutions and nonresidential daycare centers for developmentally disabled persons. People who are served at most of these facilities are also at risk for hepatitis C virus infection.

Three categories are listed by the CDC and not by the USPSTF, in either the recommendation or evidence report. These include a history of multiple sex partners; elevated ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels of unknown origin; and patient request for testing (because they may not want to reveal risk factors).

Continue to: What test(s) should be ordered?

What test(s) should be ordered?

The USPSTF recommends screening using HBsAg. The CDC recommends using triple-panel screening: HBsAg, anti-hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), and total antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc).

HBsAg indicates HBV infection, either acute or chronic, or a recent dose of HBV vaccine. Anti-HBs indicate recovery from HBV infection, response to HBV vaccine, or recent receipt of hepatitis B immune globulin. Total anti-HBc develops in all HBV infections, resolved or current, and usually persists for life. Vaccine-induced immunity does not cause anti-HBc to develop.

The USPSTF’s rationale is that testing for HBsAg is more than 98% sensitive and specific for detecting HBV infections.2 The CDC recommends triple testing because it can detect those with asymptomatic active HBV infections (this would be a rare occurrence); those who have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (eg, those who are immunosuppressed); and those who are susceptible and need vaccination.

Interpretation of HBV test results and suggested actions are described in TABLE 2.1,8,13

Why do the CDC and USPSTF differ?

While it would be optimal if the CDC and the USPSTF coordinated and harmonized recommendations, this is difficult to achieve given their different missions. The USPSTF is charged to make evidence-based recommendations about preventive services such as screenings, behavioral counseling, and preventive medications, which are provided by clinicians to individual patients. The Task Force uses a very strict evidence-based process and will not make recommendations unless there is adequate evidence of efficacy and safety. Members of the Task Force are primary care professionals, and their collaborating professional organizations are primary care focused.

The CDC takes a community-wide, public health perspective. The professionals that work there are not always clinicians. They strive to prevent as much illness as possible, using public health measures and making recommendations to clinicians. They collaborate with professional organizations; on topics such as hepatitis and other infectious diseases, they collaborate with specialty-oriented societies. Given the imperative to act with the best evidence available, their evidence assessment process is not as strict.

The result, at times, is slight differences in recommendations. However, the HBV screening recommendations from the CDC and the USPSTF agree more than they do not. Based on practice-specific characteristics, family physicians should decide if they want to screen all adults or only those at increased risk, and whether to use single- or triple-test screening.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently published new recommendations on screening for hepatitis B infection.1 They recommend screening all adults (ages 18 years and older) at least once.

These recommendations differ in a few ways from those of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).2 This Practice Alert will highlight these differences but also point out areas of agreement between the 2 sets of recommendations—and discuss why 2 separate agencies in the US Department of Health and Human Services reached different conclusions on some issues.

First, some background on hepatitis B

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million people in the United States have chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection—and as many as two-thirds are unaware of it.3 In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services published the Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States with a stated goal of increasing awareness of infection status among those with hepatitis B virus (HBV) from 32% to 90% by 2030.4 People living in the United States but born outside the country are at highest risk for CHB; they account for 69% of those with the infection.5

The incidence of acute HBV infection has declined markedly since the HBV vaccine was recommended for high-risk adults in 1982 and universally for infants in 1991.6,7 Overall rates of HBV infection declined fairly steadily starting around 1987—but in 2014, rates began to increase, especially in those ages 40 to 59 years.8,9 In 2019, 3192 cases were reported; but when one factors in underreporting, the CDC estimates that the number is likely closer to 20,700.10 This uptick is one reason the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices changed its HBV vaccination recommendation for adults from a risk-based to a universal recommendation for all unvaccinated adults through age 60 years.10

Chronic hepatitis B infection has serious consequences

The proportion of those infected with HBV who develop CHB differs by age at infection: 80% to 90% if infected during infancy, 30% if infected before age 6 years, and 1% to 12% if infected as an older child or adult.8

CHB infection can lead to chronic liver disease, including cirrhosis of the liver, liver cancer, and liver failure. About 25% of those who develop CHB infection during childhood and 15% of those who develop chronic infection after childhood will die prematurely from cirrhosis or liver cancer.8

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) classifies CHB into 4 phases that reflect the rate of viral replication and the patient’s immune response.11 These phases are:

- immune-tolerant (minimal inflammation and fibrosis)

- hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg)-positive immune-active (moderate-to-severe inflammation or fibrosis)

- inactive CHB (minimal necroinflammation but variable fibrosis), and

- HBeAg-negative immune reactivation (moderate-to-severe inflammation or fibrosis).11

Continue to: The progression from one phase...

The progression from one phase to the next varies by patient, and not all patients will progress through each phase. The AASLD recommends periodically monitoring the HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in those with CHB to track the progression from one phase to the next and to guide treatment decisions.

Treatment can be beneficial for those who meet criteria

The evidence report prepared for USPSTF found that antiviral treatment of those with CHB infection resulted in improved intermediate outcomes (histologic improvement, loss of hepatitis B surface antigen [HBsAg], loss of HBeAg, HBeAg seroconversion, virologic suppression, and normalization of ALT levels). The magnitude of benefit varied by location and study design.12

In addition, the evidence review found that antiviral therapy was associated with a decreased risk for overall mortality (relative risk [RR] = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03-0.69), cirrhosis (RR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.29-1.77), and hepatocellular carcinoma (RR = 0.60; 95% CI, 0.16-2.33). However, these results came from studies that were “limited due to small numbers of trials, few events, and insufficient duration of follow-up.”12

The USPSTF and the CDC both judged that the intermediate outcome results, as well as findings that improved intermediate outcomes lead to decreases in chronic liver disease, are strong enough evidence for their recommendations.

However, not all patients with CHB infection require treatment; estimates of patients with HBV infection meeting AASLD criteria for treatment range from 24% to 48%.1 The AASLD guideline on the treatment of CHB infection is an excellent resource that makes recommendations on the initial evaluation, ongoing monitoring, and treatment decisions for those with CHB.11

Continue to: How CDC and USPSTF guidance on HBV screeinng differs

How CDC and USPSTF guidance on HBV screening differs

The CDC and USPSTF recommendations for HBV screening differ in 3 aspects: whom to screen, whom to classify as at high risk for HBV infection, and what tests to use for screening.

Who should be screened?

The USPSTF recommends screening adults and adolescents who are at high risk for HBV. The CDC recommends screening all adults at least once. Both entities agree that those who are at increased risk should be screened periodically, although the optimal frequency has not been established. The USPSTF does not recommend against screening for the general population, so universal screening (as advocated by the CDC) is not in direct conflict with the USPSTF’s recommendations.

Who is at increased risk for HBV infection?

The CDC and the USPSTF differ slightly on the factors they consider to constitute increased risk for HBV infection. These are listed in TABLE 1.1,2

The CDC lists 6 categories that the USPSTF does not mention. However, 4 of these categories are mentioned indirectly in the USPSTF evidence report that accompanies the recommendations, via statements that certain settings have high proportions of people at risk for HBV infection: sexually transmitted infection clinics; HIV testing and treatment centers; health care settings that target services toward people who inject drugs and men who have sex with men; correctional facilities; hemodialysis facilities; and institutions and nonresidential daycare centers for developmentally disabled persons. People who are served at most of these facilities are also at risk for hepatitis C virus infection.

Three categories are listed by the CDC and not by the USPSTF, in either the recommendation or evidence report. These include a history of multiple sex partners; elevated ALT or aspartate aminotransferase levels of unknown origin; and patient request for testing (because they may not want to reveal risk factors).

Continue to: What test(s) should be ordered?

What test(s) should be ordered?

The USPSTF recommends screening using HBsAg. The CDC recommends using triple-panel screening: HBsAg, anti-hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), and total antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc).

HBsAg indicates HBV infection, either acute or chronic, or a recent dose of HBV vaccine. Anti-HBs indicate recovery from HBV infection, response to HBV vaccine, or recent receipt of hepatitis B immune globulin. Total anti-HBc develops in all HBV infections, resolved or current, and usually persists for life. Vaccine-induced immunity does not cause anti-HBc to develop.

The USPSTF’s rationale is that testing for HBsAg is more than 98% sensitive and specific for detecting HBV infections.2 The CDC recommends triple testing because it can detect those with asymptomatic active HBV infections (this would be a rare occurrence); those who have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (eg, those who are immunosuppressed); and those who are susceptible and need vaccination.

Interpretation of HBV test results and suggested actions are described in TABLE 2.1,8,13

Why do the CDC and USPSTF differ?

While it would be optimal if the CDC and the USPSTF coordinated and harmonized recommendations, this is difficult to achieve given their different missions. The USPSTF is charged to make evidence-based recommendations about preventive services such as screenings, behavioral counseling, and preventive medications, which are provided by clinicians to individual patients. The Task Force uses a very strict evidence-based process and will not make recommendations unless there is adequate evidence of efficacy and safety. Members of the Task Force are primary care professionals, and their collaborating professional organizations are primary care focused.

The CDC takes a community-wide, public health perspective. The professionals that work there are not always clinicians. They strive to prevent as much illness as possible, using public health measures and making recommendations to clinicians. They collaborate with professional organizations; on topics such as hepatitis and other infectious diseases, they collaborate with specialty-oriented societies. Given the imperative to act with the best evidence available, their evidence assessment process is not as strict.

The result, at times, is slight differences in recommendations. However, the HBV screening recommendations from the CDC and the USPSTF agree more than they do not. Based on practice-specific characteristics, family physicians should decide if they want to screen all adults or only those at increased risk, and whether to use single- or triple-test screening.

1. Conners EE, Panagiotakopoulos L, Hofmeister MG, et al. Screening and testing for hepatitis B virus infection: CDC recommendations—United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72:1-25. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7201a1

2. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published December 15, 2020. Access June 21, 2023. www.uspreventiveser vicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

3. Roberts H, Ly KN, Yin S, et al. Prevalence of HBV infection, vaccine-induced immunity, and susceptibility among at-risk populations: US households, 2013-2018. Hepatology. 2021;74:2353-2365. doi: 10.1002/hep.31991

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Viral hepatitis national strategic plan for the United States: a roadmap to elimination (2021-2025). Published January 7, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2023. www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Viral-Hepatitis-National-Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf

5. Wong RJ, Brosgart CL, Welch S, et al. An updated assessment of chronic hepatitis B prevalence among foreign-born persons living in the United States. Hepatology. 2021;74:607-626. doi: 10.1002/hep.31782

6. CDC. Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP): inactivated hepatitis B virus vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:317-318, 327-288.

7. CDC. Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination: recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:1-25.

8. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1

9. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance 2019. Published July 2021. Accessed June 29, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/

10. Weng MK, Doshani M, Khan MA, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19-59 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:477-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a1

11. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261-283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156

12. Chou R, Blazina I, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020;324:2423-2436. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19750

13. Abara WE, Qaseem A, Schillie S, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination, screening, and linkage to care: best practice advice from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:794-804. doi: 10.7326/M17-110

1. Conners EE, Panagiotakopoulos L, Hofmeister MG, et al. Screening and testing for hepatitis B virus infection: CDC recommendations—United States, 2023. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2023;72:1-25. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7201a1

2. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Final recommendation statement. Published December 15, 2020. Access June 21, 2023. www.uspreventiveser vicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

3. Roberts H, Ly KN, Yin S, et al. Prevalence of HBV infection, vaccine-induced immunity, and susceptibility among at-risk populations: US households, 2013-2018. Hepatology. 2021;74:2353-2365. doi: 10.1002/hep.31991

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Viral hepatitis national strategic plan for the United States: a roadmap to elimination (2021-2025). Published January 7, 2021. Accessed June 21, 2023. www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Viral-Hepatitis-National-Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf

5. Wong RJ, Brosgart CL, Welch S, et al. An updated assessment of chronic hepatitis B prevalence among foreign-born persons living in the United States. Hepatology. 2021;74:607-626. doi: 10.1002/hep.31782

6. CDC. Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP): inactivated hepatitis B virus vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1982;31:317-318, 327-288.

7. CDC. Hepatitis B virus: a comprehensive strategy for eliminating transmission in the United States through universal childhood vaccination: recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:1-25.

8. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2018;67:1-31. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1

9. CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance 2019. Published July 2021. Accessed June 29, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/

10. Weng MK, Doshani M, Khan MA, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in adults aged 19-59 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:477-483. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a1

11. Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016;63:261-283. doi: 10.1002/hep.28156

12. Chou R, Blazina I, Bougatsos C, et al. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2020;324:2423-2436. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19750

13. Abara WE, Qaseem A, Schillie S, et al. Hepatitis B vaccination, screening, and linkage to care: best practice advice from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:794-804. doi: 10.7326/M17-110

Pneumococcal vaccine label adds injection-site risk

No similar safety signal has been detected for the more recently approved 15-valent and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, explain the investigators, led by Brendan Day, MD, MPH, from the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in their report published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Reports of injection-site necrosis emerged after the vaccine (Pneumovax 23, Merck) had been approved by the FDA and was administered to a large, diverse, real-world population.

Rare safety events can emerge after FDA approval, as clinical trials may not be able to detect them in a study-group population.

Therefore, “postmarketing safety surveillance is critical to further characterize the safety profile of licensed vaccines,” the investigators point out.

The FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention monitor the postmarketing safety of licensed vaccines using the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), which relies on people who get the vaccines to report adverse events.

Real-world finding

After reports indicated a safety signal in 2020, the researchers conducted a case-series review, calculated the reporting rate, and did a PubMed search for similar reports.

They found that the reporting rate for injection-site necrosis was less than 0.2 cases per 1 million vaccine doses administered. The PubMed search yielded two cases of injection-site necrosis after the vaccine.

The 23-valent vaccine helps protect people from pneumococcus bacterial infection. The manufacturer reports that it is for people at least 50 years of age and for children who are at least 2 years of age with medical conditions that put them at elevated risk for infection.

The U.S. package insert has been updated, in the Post-Marketing Experience section, to include injection-site necrosis.

Of the 104 VAERS reports identified by the researchers, 48 met the case definition. Of those cases, most were for skin necrosis (n = 43), five of which also included fat necrosis. The remaining five cases of necrosis affected fascia (n = 2); fat and fascia (n = 1); fat, fascia, and muscle (n = 1); and muscle (n = 1).

In 23 of the 48 cases (47.9%), the reactions were serious and included one death (unrelated to vaccination).

Seventeen patients (35.4%) were hospitalized and 26 (54.2%) required surgery, most commonly debridement. Eight patients (16.7%) underwent multiple surgical procedures and three (6.3%) required a skin graft.

For patients with skin necrosis (n = 43), the median age was 67 years, and most patients were female (n = 36). Twelve patients were immunocompromised.

Concomitant vaccinations were reported in 10 patients, five of whom got the shot in the same arm as the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine. A concurrent diagnosis of cellulitis was reported in 16 patients and an abscess was reported in three patients. There were too few cases of fat, fascia, or muscle necrosis to draw conclusions, the researchers report.

Often, skin necrosis was seen after a progression of symptoms, such as redness, pain, or swelling.

“These reports are consistent with published descriptions of injection-site necrosis, which has been reported as a rare complication for many vaccines and injectable drugs,” the investigators report.

Although the researchers couldn’t conclude from the VAERS reports alone that the vaccine injection caused the necrosis, “the timing and the location of reactions at the injection site suggest a possible causal association with the vaccine,” they explain. However, they add, patient comorbidities and poor injection technique may also be contributors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No similar safety signal has been detected for the more recently approved 15-valent and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, explain the investigators, led by Brendan Day, MD, MPH, from the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in their report published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Reports of injection-site necrosis emerged after the vaccine (Pneumovax 23, Merck) had been approved by the FDA and was administered to a large, diverse, real-world population.

Rare safety events can emerge after FDA approval, as clinical trials may not be able to detect them in a study-group population.

Therefore, “postmarketing safety surveillance is critical to further characterize the safety profile of licensed vaccines,” the investigators point out.

The FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention monitor the postmarketing safety of licensed vaccines using the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), which relies on people who get the vaccines to report adverse events.

Real-world finding

After reports indicated a safety signal in 2020, the researchers conducted a case-series review, calculated the reporting rate, and did a PubMed search for similar reports.

They found that the reporting rate for injection-site necrosis was less than 0.2 cases per 1 million vaccine doses administered. The PubMed search yielded two cases of injection-site necrosis after the vaccine.

The 23-valent vaccine helps protect people from pneumococcus bacterial infection. The manufacturer reports that it is for people at least 50 years of age and for children who are at least 2 years of age with medical conditions that put them at elevated risk for infection.

The U.S. package insert has been updated, in the Post-Marketing Experience section, to include injection-site necrosis.

Of the 104 VAERS reports identified by the researchers, 48 met the case definition. Of those cases, most were for skin necrosis (n = 43), five of which also included fat necrosis. The remaining five cases of necrosis affected fascia (n = 2); fat and fascia (n = 1); fat, fascia, and muscle (n = 1); and muscle (n = 1).

In 23 of the 48 cases (47.9%), the reactions were serious and included one death (unrelated to vaccination).

Seventeen patients (35.4%) were hospitalized and 26 (54.2%) required surgery, most commonly debridement. Eight patients (16.7%) underwent multiple surgical procedures and three (6.3%) required a skin graft.

For patients with skin necrosis (n = 43), the median age was 67 years, and most patients were female (n = 36). Twelve patients were immunocompromised.

Concomitant vaccinations were reported in 10 patients, five of whom got the shot in the same arm as the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine. A concurrent diagnosis of cellulitis was reported in 16 patients and an abscess was reported in three patients. There were too few cases of fat, fascia, or muscle necrosis to draw conclusions, the researchers report.

Often, skin necrosis was seen after a progression of symptoms, such as redness, pain, or swelling.

“These reports are consistent with published descriptions of injection-site necrosis, which has been reported as a rare complication for many vaccines and injectable drugs,” the investigators report.

Although the researchers couldn’t conclude from the VAERS reports alone that the vaccine injection caused the necrosis, “the timing and the location of reactions at the injection site suggest a possible causal association with the vaccine,” they explain. However, they add, patient comorbidities and poor injection technique may also be contributors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No similar safety signal has been detected for the more recently approved 15-valent and 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, explain the investigators, led by Brendan Day, MD, MPH, from the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, in their report published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Reports of injection-site necrosis emerged after the vaccine (Pneumovax 23, Merck) had been approved by the FDA and was administered to a large, diverse, real-world population.

Rare safety events can emerge after FDA approval, as clinical trials may not be able to detect them in a study-group population.

Therefore, “postmarketing safety surveillance is critical to further characterize the safety profile of licensed vaccines,” the investigators point out.

The FDA and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention monitor the postmarketing safety of licensed vaccines using the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), which relies on people who get the vaccines to report adverse events.

Real-world finding

After reports indicated a safety signal in 2020, the researchers conducted a case-series review, calculated the reporting rate, and did a PubMed search for similar reports.

They found that the reporting rate for injection-site necrosis was less than 0.2 cases per 1 million vaccine doses administered. The PubMed search yielded two cases of injection-site necrosis after the vaccine.

The 23-valent vaccine helps protect people from pneumococcus bacterial infection. The manufacturer reports that it is for people at least 50 years of age and for children who are at least 2 years of age with medical conditions that put them at elevated risk for infection.

The U.S. package insert has been updated, in the Post-Marketing Experience section, to include injection-site necrosis.

Of the 104 VAERS reports identified by the researchers, 48 met the case definition. Of those cases, most were for skin necrosis (n = 43), five of which also included fat necrosis. The remaining five cases of necrosis affected fascia (n = 2); fat and fascia (n = 1); fat, fascia, and muscle (n = 1); and muscle (n = 1).

In 23 of the 48 cases (47.9%), the reactions were serious and included one death (unrelated to vaccination).

Seventeen patients (35.4%) were hospitalized and 26 (54.2%) required surgery, most commonly debridement. Eight patients (16.7%) underwent multiple surgical procedures and three (6.3%) required a skin graft.

For patients with skin necrosis (n = 43), the median age was 67 years, and most patients were female (n = 36). Twelve patients were immunocompromised.

Concomitant vaccinations were reported in 10 patients, five of whom got the shot in the same arm as the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine. A concurrent diagnosis of cellulitis was reported in 16 patients and an abscess was reported in three patients. There were too few cases of fat, fascia, or muscle necrosis to draw conclusions, the researchers report.

Often, skin necrosis was seen after a progression of symptoms, such as redness, pain, or swelling.

“These reports are consistent with published descriptions of injection-site necrosis, which has been reported as a rare complication for many vaccines and injectable drugs,” the investigators report.

Although the researchers couldn’t conclude from the VAERS reports alone that the vaccine injection caused the necrosis, “the timing and the location of reactions at the injection site suggest a possible causal association with the vaccine,” they explain. However, they add, patient comorbidities and poor injection technique may also be contributors.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

FDA approves RSV monoclonal antibody for all infants

The monoclonal antibody Beyfortus (nirsevimab-alip), which already is approved for use in Europe and Canada, is indicated for newborns and infants born during or entering their first RSV season, and for children up to 24 months of age who are vulnerable to severe RSV through their second RSV season.

As many as 80,000 children under age 5 years are hospitalized with an RSV infection annually in the United States. Most cases are mild, but infants under 6 months, those born prematurely, and children with weakened immune systems or neuromuscular disorders are at an increased risk for severe illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highly contagious virus is also a concern for immunocompromised adults and older people with underlying health conditions, who are at increased risk for severe disease.

Sanofi and AstraZeneca, which jointly developed the injectable agent, said in a press release that the companies plan to make it available by the fall of 2023. The long-acting antibody is given as a single intramuscular injection.

Beyfortus was approved in part based on data from the phase 3 MELODY trial, which found the shot reduced the incidence of medically attended lower respiratory tract infections associated with RSV by 74.9% versus placebo (95% confidence interval, 50.6-87.3; P < .001).

The phase 2/3 MEDLEY trial, conducted between July 2019 and May 2021, compared Beyfortus with palivizumab, another RSV antibody injection with more limited indications. The trial included more than 900 preterm infants less than 35 weeks’ gestational age and infants with congenital heart disease. Results were similar to the phase 3 MELODY trial, according to the manufacturers.

“Today’s approval marks an unprecedented moment for protecting infant health in the United States, following an RSV season that took a record toll on infants, their families, and the U.S. health care system,” said Thomas Triomphe, executive vice president for vaccines at Sanofi, in a press release about the FDA decision. “Beyfortus is the only monoclonal antibody approved for passive immunization to provide safe and effective protection for all infants during their first RSV season.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The monoclonal antibody Beyfortus (nirsevimab-alip), which already is approved for use in Europe and Canada, is indicated for newborns and infants born during or entering their first RSV season, and for children up to 24 months of age who are vulnerable to severe RSV through their second RSV season.

As many as 80,000 children under age 5 years are hospitalized with an RSV infection annually in the United States. Most cases are mild, but infants under 6 months, those born prematurely, and children with weakened immune systems or neuromuscular disorders are at an increased risk for severe illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highly contagious virus is also a concern for immunocompromised adults and older people with underlying health conditions, who are at increased risk for severe disease.

Sanofi and AstraZeneca, which jointly developed the injectable agent, said in a press release that the companies plan to make it available by the fall of 2023. The long-acting antibody is given as a single intramuscular injection.

Beyfortus was approved in part based on data from the phase 3 MELODY trial, which found the shot reduced the incidence of medically attended lower respiratory tract infections associated with RSV by 74.9% versus placebo (95% confidence interval, 50.6-87.3; P < .001).

The phase 2/3 MEDLEY trial, conducted between July 2019 and May 2021, compared Beyfortus with palivizumab, another RSV antibody injection with more limited indications. The trial included more than 900 preterm infants less than 35 weeks’ gestational age and infants with congenital heart disease. Results were similar to the phase 3 MELODY trial, according to the manufacturers.

“Today’s approval marks an unprecedented moment for protecting infant health in the United States, following an RSV season that took a record toll on infants, their families, and the U.S. health care system,” said Thomas Triomphe, executive vice president for vaccines at Sanofi, in a press release about the FDA decision. “Beyfortus is the only monoclonal antibody approved for passive immunization to provide safe and effective protection for all infants during their first RSV season.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The monoclonal antibody Beyfortus (nirsevimab-alip), which already is approved for use in Europe and Canada, is indicated for newborns and infants born during or entering their first RSV season, and for children up to 24 months of age who are vulnerable to severe RSV through their second RSV season.

As many as 80,000 children under age 5 years are hospitalized with an RSV infection annually in the United States. Most cases are mild, but infants under 6 months, those born prematurely, and children with weakened immune systems or neuromuscular disorders are at an increased risk for severe illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The highly contagious virus is also a concern for immunocompromised adults and older people with underlying health conditions, who are at increased risk for severe disease.

Sanofi and AstraZeneca, which jointly developed the injectable agent, said in a press release that the companies plan to make it available by the fall of 2023. The long-acting antibody is given as a single intramuscular injection.

Beyfortus was approved in part based on data from the phase 3 MELODY trial, which found the shot reduced the incidence of medically attended lower respiratory tract infections associated with RSV by 74.9% versus placebo (95% confidence interval, 50.6-87.3; P < .001).

The phase 2/3 MEDLEY trial, conducted between July 2019 and May 2021, compared Beyfortus with palivizumab, another RSV antibody injection with more limited indications. The trial included more than 900 preterm infants less than 35 weeks’ gestational age and infants with congenital heart disease. Results were similar to the phase 3 MELODY trial, according to the manufacturers.

“Today’s approval marks an unprecedented moment for protecting infant health in the United States, following an RSV season that took a record toll on infants, their families, and the U.S. health care system,” said Thomas Triomphe, executive vice president for vaccines at Sanofi, in a press release about the FDA decision. “Beyfortus is the only monoclonal antibody approved for passive immunization to provide safe and effective protection for all infants during their first RSV season.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID and vaccines: Separating facts from falsehoods

The COVID-19 vaccines have been a game changer for millions of people worldwide in preventing death or disability from the virus. Research suggests that they offer significant protection against long COVID.

False and unfounded claims made by some antivaccine groups that the vaccines themselves may cause long COVID persist and serve as barriers to vaccination.

To help separate the facts from falsehoods, here’s a checklist for doctors on what scientific studies have determined about vaccination and long COVID.

What the research shows

Doctors who work in long COVID clinics have for years suspected that vaccination may help protect against the development of long COVID, noted Lawrence Purpura, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, who treats patients with long COVID in his clinic.

Over the past year, several large, well-conducted studies have borne out that theory, including the following studies:

- In the RECOVER study, published in May in the journal Nature Communications, researchers examined the electronic health records of more than 5 million people who had been diagnosed with COVID and found that vaccination reduced the risk that they would develop long COVID. Although the researchers didn’t compare the effects of having boosters to being fully vaccinated without them, experts have suggested that having a full round of recommended shots may offer the most protection. “My thoughts are that more shots are better, and other work has shown compelling evidence that the protective effect of vaccination on COVID-19 wanes over time,” said study coauthor Daniel Brannock, MS, a research scientist at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, N.C. “It stands to reason that the same is true for long COVID.”

- A review published in February in BMJ Medicine concluded that 10 studies showed a significant reduction in the incidence of long COVID among vaccinated patients. Even one dose of a vaccine was protective.

- A meta-analysis of six studies published last December in Antimicrobial Stewardship and Healthcare Epidemiology found that one or more doses of a COVID-19 vaccine were 29% effective in preventing symptoms of long COVID.

- In a June meta-analysis published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers analyzed more than 40 studies that included 860,000 patients and found that two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of long COVID by almost half.

The message? COVID vaccination is very effective in reducing the risk of long COVID.

“It’s important to emphasize that many of the risk factors [for long COVID] cannot be changed, or at least cannot be changed easily, but vaccination is a decision that can be taken by everyone,” said Vassilios Vassiliou, MBBS, PhD, clinical professor of cardiac medicine at Norwich Medical School in England, who coauthored the article in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Why vaccines may be protective

The COVID-19 vaccines work well to prevent serious illness from the virus, noted Aaron Friedberg, MD, clinical coleader of the Post COVID Recovery Program at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. That may be a clue to why the vaccines help prevent long COVID symptoms.

“When you get COVID and you’ve been vaccinated, the virus may still attach in your nose and respiratory tract, but it’s less likely to spread throughout your body,” he explained. “It’s like a forest fire – if the ground is wet or it starts to rain, it’s less likely to create a great blaze. As a result, your body is less likely to experience inflammation and damage that makes it more likely that you’ll develop long COVID.”

Dr. Friedberg stressed that even for patients who have had COVID, it’s important to get vaccinated – a message he consistently delivers to his own patients.

“There is some protection that comes from having COVID before, but for some people, that’s not enough,” he said. “It’s true that after infection, your body creates antibodies that help protect you against the virus. But I explain to patients that these may be like old Velcro: They barely grab on enough to stay on for the moment, but they don’t last long term. You’re much more likely to get a reliable immune response from the vaccine.”

In addition, a second or third bout of COVID could be the one that gives patients long COVID, Dr. Friedberg adds.

“I have a number of patients in my clinic who were fine after their first bout of COVID but experienced debilitating long COVID symptoms after they developed COVID again,” he said. “Why leave it to chance?”

Vaccines and ‘long vax’

The COVID vaccines are considered very safe but have been linked to very rare side effects, such as blood clots and heart inflammation. There have also been anecdotal reports of symptoms that resemble long COVID – a syndrome that has come to be known as “long Vax” – an extremely rare condition that may or may not be tied to vaccination.

“I have seen people in my clinic who developed symptoms suggestive of long COVID that linger for months – brain fog, fatigue, heart palpitations – soon after they got the COVID-19 vaccine,” said Dr. Purpura. But no published studies have suggested a link, he cautions.

A study called LISTEN is being organized at Yale in an effort to better understand postvaccine adverse events and a potential link to long COVID.

Talking to patients

Discussions of vaccination with patients, including those with COVID or long COVID, are often fraught and challenging, said Dr. Purpura.

“There’s a lot of fear that they will have a worsening of their symptoms,” he explained. The conversation he has with his patients mirrors the conversation all physicians should have with their patients about COVID-19 vaccination, even if they don’t have long COVID. He stresses the importance of highlighting the following components:

- Show compassion and empathy. “A lot of people have strongly held opinions – it’s worth it to try to find out why they feel the way that they do,” said Dr. Friedberg.

- Walk them through side effects. “Many people are afraid of the side effects of the vaccine, especially if they already have long COVID,” explained Dr. Purpura. Such patients can be asked how they felt after their last vaccination, such a shingles or flu shot. Then explain that the COVID-19 vaccine is not much different and that they may experience temporary side effects such as fatigue, headache, or a mild fever for 24-48 hours.

- Explain the benefits. Eighty-five percent of people say their health care provider is a trusted source of information on COVID-19 vaccines, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. That trust is conducive to talks about the vaccine’s benefits, including its ability to protect against long COVID.

Other ways to reduce risk of long COVID

Vaccines can lower the chances of a patient’s developing long COVID. So can the antiviral medication nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid). A March 2023 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine included more than 280,000 people with COVID. The researchers found that vaccination reduced the risk for developing the condition by about 25%.

“I mention that study to all of my long COVID patients who become reinfected with the virus,” said Dr. Purpura. “It not only appears protective against long COVID, but since it lowers levels of virus circulating in their body, it seems to help prevent a flare-up of symptoms.”

Another treatment that may help is the diabetes drug metformin, he added.

A June 2023 study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases found that when metformin was given within 3 days of symptom onset, the incidence of long COVID was reduced by about 41%.

“We’re still trying to wrap our brains around this one, but the thought is it may help to lower inflammation, which plays a role in long COVID,” Dr. Purpura explained. More studies need to be conducted, though, before recommending its use.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 vaccines have been a game changer for millions of people worldwide in preventing death or disability from the virus. Research suggests that they offer significant protection against long COVID.

False and unfounded claims made by some antivaccine groups that the vaccines themselves may cause long COVID persist and serve as barriers to vaccination.

To help separate the facts from falsehoods, here’s a checklist for doctors on what scientific studies have determined about vaccination and long COVID.

What the research shows

Doctors who work in long COVID clinics have for years suspected that vaccination may help protect against the development of long COVID, noted Lawrence Purpura, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, who treats patients with long COVID in his clinic.

Over the past year, several large, well-conducted studies have borne out that theory, including the following studies:

- In the RECOVER study, published in May in the journal Nature Communications, researchers examined the electronic health records of more than 5 million people who had been diagnosed with COVID and found that vaccination reduced the risk that they would develop long COVID. Although the researchers didn’t compare the effects of having boosters to being fully vaccinated without them, experts have suggested that having a full round of recommended shots may offer the most protection. “My thoughts are that more shots are better, and other work has shown compelling evidence that the protective effect of vaccination on COVID-19 wanes over time,” said study coauthor Daniel Brannock, MS, a research scientist at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, N.C. “It stands to reason that the same is true for long COVID.”

- A review published in February in BMJ Medicine concluded that 10 studies showed a significant reduction in the incidence of long COVID among vaccinated patients. Even one dose of a vaccine was protective.

- A meta-analysis of six studies published last December in Antimicrobial Stewardship and Healthcare Epidemiology found that one or more doses of a COVID-19 vaccine were 29% effective in preventing symptoms of long COVID.

- In a June meta-analysis published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers analyzed more than 40 studies that included 860,000 patients and found that two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of long COVID by almost half.

The message? COVID vaccination is very effective in reducing the risk of long COVID.

“It’s important to emphasize that many of the risk factors [for long COVID] cannot be changed, or at least cannot be changed easily, but vaccination is a decision that can be taken by everyone,” said Vassilios Vassiliou, MBBS, PhD, clinical professor of cardiac medicine at Norwich Medical School in England, who coauthored the article in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Why vaccines may be protective

The COVID-19 vaccines work well to prevent serious illness from the virus, noted Aaron Friedberg, MD, clinical coleader of the Post COVID Recovery Program at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. That may be a clue to why the vaccines help prevent long COVID symptoms.

“When you get COVID and you’ve been vaccinated, the virus may still attach in your nose and respiratory tract, but it’s less likely to spread throughout your body,” he explained. “It’s like a forest fire – if the ground is wet or it starts to rain, it’s less likely to create a great blaze. As a result, your body is less likely to experience inflammation and damage that makes it more likely that you’ll develop long COVID.”

Dr. Friedberg stressed that even for patients who have had COVID, it’s important to get vaccinated – a message he consistently delivers to his own patients.

“There is some protection that comes from having COVID before, but for some people, that’s not enough,” he said. “It’s true that after infection, your body creates antibodies that help protect you against the virus. But I explain to patients that these may be like old Velcro: They barely grab on enough to stay on for the moment, but they don’t last long term. You’re much more likely to get a reliable immune response from the vaccine.”

In addition, a second or third bout of COVID could be the one that gives patients long COVID, Dr. Friedberg adds.

“I have a number of patients in my clinic who were fine after their first bout of COVID but experienced debilitating long COVID symptoms after they developed COVID again,” he said. “Why leave it to chance?”

Vaccines and ‘long vax’

The COVID vaccines are considered very safe but have been linked to very rare side effects, such as blood clots and heart inflammation. There have also been anecdotal reports of symptoms that resemble long COVID – a syndrome that has come to be known as “long Vax” – an extremely rare condition that may or may not be tied to vaccination.

“I have seen people in my clinic who developed symptoms suggestive of long COVID that linger for months – brain fog, fatigue, heart palpitations – soon after they got the COVID-19 vaccine,” said Dr. Purpura. But no published studies have suggested a link, he cautions.

A study called LISTEN is being organized at Yale in an effort to better understand postvaccine adverse events and a potential link to long COVID.

Talking to patients

Discussions of vaccination with patients, including those with COVID or long COVID, are often fraught and challenging, said Dr. Purpura.

“There’s a lot of fear that they will have a worsening of their symptoms,” he explained. The conversation he has with his patients mirrors the conversation all physicians should have with their patients about COVID-19 vaccination, even if they don’t have long COVID. He stresses the importance of highlighting the following components:

- Show compassion and empathy. “A lot of people have strongly held opinions – it’s worth it to try to find out why they feel the way that they do,” said Dr. Friedberg.

- Walk them through side effects. “Many people are afraid of the side effects of the vaccine, especially if they already have long COVID,” explained Dr. Purpura. Such patients can be asked how they felt after their last vaccination, such a shingles or flu shot. Then explain that the COVID-19 vaccine is not much different and that they may experience temporary side effects such as fatigue, headache, or a mild fever for 24-48 hours.

- Explain the benefits. Eighty-five percent of people say their health care provider is a trusted source of information on COVID-19 vaccines, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. That trust is conducive to talks about the vaccine’s benefits, including its ability to protect against long COVID.

Other ways to reduce risk of long COVID

Vaccines can lower the chances of a patient’s developing long COVID. So can the antiviral medication nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid). A March 2023 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine included more than 280,000 people with COVID. The researchers found that vaccination reduced the risk for developing the condition by about 25%.

“I mention that study to all of my long COVID patients who become reinfected with the virus,” said Dr. Purpura. “It not only appears protective against long COVID, but since it lowers levels of virus circulating in their body, it seems to help prevent a flare-up of symptoms.”

Another treatment that may help is the diabetes drug metformin, he added.

A June 2023 study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases found that when metformin was given within 3 days of symptom onset, the incidence of long COVID was reduced by about 41%.

“We’re still trying to wrap our brains around this one, but the thought is it may help to lower inflammation, which plays a role in long COVID,” Dr. Purpura explained. More studies need to be conducted, though, before recommending its use.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The COVID-19 vaccines have been a game changer for millions of people worldwide in preventing death or disability from the virus. Research suggests that they offer significant protection against long COVID.

False and unfounded claims made by some antivaccine groups that the vaccines themselves may cause long COVID persist and serve as barriers to vaccination.

To help separate the facts from falsehoods, here’s a checklist for doctors on what scientific studies have determined about vaccination and long COVID.

What the research shows

Doctors who work in long COVID clinics have for years suspected that vaccination may help protect against the development of long COVID, noted Lawrence Purpura, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist at New York–Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, who treats patients with long COVID in his clinic.

Over the past year, several large, well-conducted studies have borne out that theory, including the following studies:

- In the RECOVER study, published in May in the journal Nature Communications, researchers examined the electronic health records of more than 5 million people who had been diagnosed with COVID and found that vaccination reduced the risk that they would develop long COVID. Although the researchers didn’t compare the effects of having boosters to being fully vaccinated without them, experts have suggested that having a full round of recommended shots may offer the most protection. “My thoughts are that more shots are better, and other work has shown compelling evidence that the protective effect of vaccination on COVID-19 wanes over time,” said study coauthor Daniel Brannock, MS, a research scientist at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, N.C. “It stands to reason that the same is true for long COVID.”

- A review published in February in BMJ Medicine concluded that 10 studies showed a significant reduction in the incidence of long COVID among vaccinated patients. Even one dose of a vaccine was protective.

- A meta-analysis of six studies published last December in Antimicrobial Stewardship and Healthcare Epidemiology found that one or more doses of a COVID-19 vaccine were 29% effective in preventing symptoms of long COVID.

- In a June meta-analysis published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers analyzed more than 40 studies that included 860,000 patients and found that two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine reduced the risk of long COVID by almost half.

The message? COVID vaccination is very effective in reducing the risk of long COVID.

“It’s important to emphasize that many of the risk factors [for long COVID] cannot be changed, or at least cannot be changed easily, but vaccination is a decision that can be taken by everyone,” said Vassilios Vassiliou, MBBS, PhD, clinical professor of cardiac medicine at Norwich Medical School in England, who coauthored the article in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Why vaccines may be protective

The COVID-19 vaccines work well to prevent serious illness from the virus, noted Aaron Friedberg, MD, clinical coleader of the Post COVID Recovery Program at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. That may be a clue to why the vaccines help prevent long COVID symptoms.

“When you get COVID and you’ve been vaccinated, the virus may still attach in your nose and respiratory tract, but it’s less likely to spread throughout your body,” he explained. “It’s like a forest fire – if the ground is wet or it starts to rain, it’s less likely to create a great blaze. As a result, your body is less likely to experience inflammation and damage that makes it more likely that you’ll develop long COVID.”

Dr. Friedberg stressed that even for patients who have had COVID, it’s important to get vaccinated – a message he consistently delivers to his own patients.

“There is some protection that comes from having COVID before, but for some people, that’s not enough,” he said. “It’s true that after infection, your body creates antibodies that help protect you against the virus. But I explain to patients that these may be like old Velcro: They barely grab on enough to stay on for the moment, but they don’t last long term. You’re much more likely to get a reliable immune response from the vaccine.”

In addition, a second or third bout of COVID could be the one that gives patients long COVID, Dr. Friedberg adds.

“I have a number of patients in my clinic who were fine after their first bout of COVID but experienced debilitating long COVID symptoms after they developed COVID again,” he said. “Why leave it to chance?”

Vaccines and ‘long vax’

The COVID vaccines are considered very safe but have been linked to very rare side effects, such as blood clots and heart inflammation. There have also been anecdotal reports of symptoms that resemble long COVID – a syndrome that has come to be known as “long Vax” – an extremely rare condition that may or may not be tied to vaccination.

“I have seen people in my clinic who developed symptoms suggestive of long COVID that linger for months – brain fog, fatigue, heart palpitations – soon after they got the COVID-19 vaccine,” said Dr. Purpura. But no published studies have suggested a link, he cautions.

A study called LISTEN is being organized at Yale in an effort to better understand postvaccine adverse events and a potential link to long COVID.

Talking to patients

Discussions of vaccination with patients, including those with COVID or long COVID, are often fraught and challenging, said Dr. Purpura.

“There’s a lot of fear that they will have a worsening of their symptoms,” he explained. The conversation he has with his patients mirrors the conversation all physicians should have with their patients about COVID-19 vaccination, even if they don’t have long COVID. He stresses the importance of highlighting the following components:

- Show compassion and empathy. “A lot of people have strongly held opinions – it’s worth it to try to find out why they feel the way that they do,” said Dr. Friedberg.

- Walk them through side effects. “Many people are afraid of the side effects of the vaccine, especially if they already have long COVID,” explained Dr. Purpura. Such patients can be asked how they felt after their last vaccination, such a shingles or flu shot. Then explain that the COVID-19 vaccine is not much different and that they may experience temporary side effects such as fatigue, headache, or a mild fever for 24-48 hours.

- Explain the benefits. Eighty-five percent of people say their health care provider is a trusted source of information on COVID-19 vaccines, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. That trust is conducive to talks about the vaccine’s benefits, including its ability to protect against long COVID.

Other ways to reduce risk of long COVID