User login

Is the WHO’s HPV vaccination target within reach?

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

The WHO’s goal is to have HPV vaccines delivered to 90% of all adolescent girls by 2030, part of the organization’s larger goal to “eliminate” cervical cancer, or reduce the annual incidence of cervical cancer to below 4 cases per 100,000 people globally.

Laia Bruni, MD, PhD, of Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona, and colleagues outlined the progress made thus far toward reaching the WHO’s goals in an article published in Preventive Medicine.

The authors noted that cervical cancer caused by HPV is a “major public health problem, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC).”

However, vaccines against HPV have been available since 2006 and have been recommended by the WHO since 2009.

HPV vaccines have been introduced into many national immunization schedules. Among the 194 WHO member states, 107 (55%) had introduced HPV vaccination as of June 2020, according to estimates from the WHO and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

Still, vaccine introduction and coverages are suboptimal, according to several studies and international agencies.

In their article, Dr. Bruni and colleagues describe the mid-2020 status of HPV vaccine introduction, based on WHO/UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage from 2010 to 2019.

HPV vaccination by region

The Americas and Europe are by far the WHO regions with the highest rates of HPV vaccination, with 85% and 77% of their countries, respectively, having already introduced HPV vaccination, either partially or nationwide.

In 2019, a record number of introductions, 16, were reported, mostly in LMICs where access has been limited. In prior years, the average had been a relatively steady 7-8 introductions per year.

The percentage of high-income countries (HICs) that have introduced HPV vaccination exceeds 80%. LMICs started introducing HPV vaccination later and at a slower pace, compared with HICs. By the end of 2019, only 41% of LMICs had introduced vaccination. However, of the new introductions in 2019, 87% were in LMICs.

In 2019, the average performance coverage for HPV vaccination programs in 99 countries (both HICs and LMICs) was around 67% for the first vaccine dose and 53% for the final dose.

Median performance coverage was higher in LMICs than in HICs for the first dose (80% and 72%, respectively), but mean dropout rates were higher in LMICs than in HICs (18% and 11%, respectively).

Coverage of more than 90% was achieved for the last dose in only five countries (6%). Twenty-two countries (21%) achieved coverages of 75% or higher, while 35 countries (40%) had final dose coverages of 50% or less.

Global coverage of the final HPV vaccine dose (weighted by population size) was estimated at 15%. According to the authors, that low percentage can be explained by the fact that many of the most populous countries have either not yet introduced HPV vaccination or have low performance.

The countries with highest cervical cancer burden have had limited secondary prevention and have been less likely to provide access to vaccination, the authors noted. However, this trend appears to be reversing, with 14 new LMICs providing HPV vaccination in 2019.

HPV vaccination by sex

By 2019, almost a third of the 107 HPV vaccination programs (n = 33) were “gender neutral,” with girls and boys receiving HPV vaccines. Generally, LMICs targeted younger girls (9-10 years) compared with HICs (11-13 years).

Dr. Bruni and colleagues estimated that 15% of girls and 4% of boys were vaccinated globally with the full course of vaccine. At least one dose was received by 20% of girls and 5% of boys.

From 2010 to 2019, HPV vaccination rates in HICs rose from 42% in girls and 0% in boys to 88% and 44%, respectively. In LMICs, over the same period, rates rose from 4% in girls and 0% in boys to 40% and 5%, respectively.

Obstacles and the path forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has halted HPV vaccine delivery in the majority of countries, Dr. Bruni and colleagues noted. About 70 countries had reported program interruptions by August 2020, and delays to HPV vaccine introductions were anticipated for other countries.

An economic downturn could have further far-reaching effects on plans to introduce HPV vaccines, Dr. Bruni and colleagues observed.

While meeting the 2030 target will be challenging, the authors noted that, in every geographic area, some programs are meeting the 90% target.

“HPV national programs should aim to get 90+% of girls vaccinated before the age of 15,” Dr. Bruni said in an interview. “This is a feasible goal, and some countries have succeeded, such as Norway and Rwanda. Average performance, however, is around 55%, and that shows that it is not an easy task.”

Dr. Bruni underscored the four main actions that should be taken to achieve 90% coverage of HPV vaccination, as outlined in the WHO cervical cancer elimination strategy:

- Secure sufficient and affordable HPV vaccines.

- Increase the quality and coverage of vaccination.

- Improve communication and social mobilization.

- Innovate to improve efficiency of vaccine delivery.

“Addressing vaccine hesitancy adequately is one of the biggest challenges we face, especially for the HPV vaccine,” Dr. Bruni said. “As the WHO document states, understanding social, cultural, societal, and other barriers affecting acceptance and uptake of the vaccine will be critical for overcoming vaccine hesitancy and countering misinformation.”

This research was funded by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and various other grants. Dr. Bruni and coauthors said they have no relevant disclosures.

FROM PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Some with long COVID see relief after vaccination

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Several weeks after getting his second dose of an mRNA vaccine, Aaron Goyang thinks his long bout with COVID-19 has finally come to an end.

Mr. Goyang, who is 33 and is a radiology technician in Austin, Tex., thinks he got COVID-19 from some of the coughing, gasping patients he treated last spring.

At the time, testing was scarce, and by the time he was tested – several weeks into his illness – it came back negative. He fought off the initial symptoms but experienced relapse a week later.

Mr. Goyang says that, for the next 8 or 9 months, he was on a roller coaster with extreme shortness of breath and chest tightness that could be so severe it would send him to the emergency department. He had to use an inhaler to get through his workdays.

“Even if I was just sitting around, it would come and take me,” he says. “It almost felt like someone was bear-hugging me constantly, and I just couldn’t get in a good enough breath.”

On his best days, he would walk around his neighborhood, being careful not to overdo it. He tried running once, and it nearly sent him to the hospital.

“Very honestly, I didn’t know if I would ever be able to do it again,” he says.

But Mr. Goyang says that, several weeks after getting the Pfizer vaccine, he was able to run a mile again with no problems. “I was very thankful for that,” he says.

Mr. Goyang is not alone. Some social media groups are dedicated to patients who are living with a condition that’s been known as long COVID and that was recently termed postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). These patients are sometimes referred to as long haulers.

On social media, patients with PASC are eagerly and anxiously quizzing each other about the vaccines and their effects.

Survivor Corps, which has a public Facebook group with 159,000 members, recently took a poll to see whether there was any substance to rumors that those with long COVID were feeling better after being vaccinated.

“Out of 400 people, 36% showed an improvement in symptoms, anywhere between a mild improvement to complete resolution of symptoms,” said Diana Berrent, a long-COVID patient who founded the group. Survivor Corps has become active in patient advocacy and is a resource for researchers studying the new condition.

Ms. Berrent has become such a trusted voice during the pandemic. She interviewed Anthony Fauci, MD, head of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, last October.

“The implications are huge,” she says.

“Some of this damage is permanent damage. It’s not going to cure the scarring of your heart tissue, it’s not going to cure the irreparable damage to your lungs, but if it’s making people feel better, then that’s an indication there’s viral persistence going on,” says Ms. Berrent.

“I’ve been saying for months and months, we shouldn’t be calling this postacute anything,” she adds.

Patients report improvement

Daniel Griffin, MD, PhD, is equally excited. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Columbia University, New York. He says about one in five patients he treated for COVID-19 last year never got better. Many of them, such as Mr. Goyang, were health care workers.

“I don’t know if people actually catch this, but a lot of our coworkers are either permanently disabled or died,” Dr. Griffin says.

Health care workers were also among the first to be vaccinated. Dr. Griffin says many of his patients began reaching out to him about a week or two after being vaccinated “and saying, ‘You know, I actually feel better.’ And some of them were saying, ‘I feel all better,’ after being sick – a lot of them – for a year.”

Then he was getting calls and texts from other doctors, asking, “Hey, are you seeing this?”

The benefits of vaccination for some long-haulers came as a surprise. Dr. Griffin says that, before the vaccines came out, many of his patients were worried that getting vaccinated might overstimulate their immune systems and cause symptoms to get worse.

Indeed, a small percentage of people – about 3%-5%, based on informal polls on social media – report that they do experience worsening of symptoms after getting the shot. It’s not clear why.

Dr. Griffin estimates that between 30% and 50% of patients’ symptoms improve after they receive the mRNA vaccines. “I’m seeing this chunk of people – they tell me their brain fog has improved, their fatigue is gone, the fevers that wouldn’t resolve have now gone,” he says. “I’m seeing that personally, and I’m hearing it from my colleagues.”

Dr. Griffin says the observation has launched several studies and that there are several theories about how the vaccines might be affecting long COVID.

An immune system boost?

One possibility is that the virus continues to stimulate the immune system, which continues to fight the virus for months. If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be giving the immune system the boost it needs to finally clear the virus away.

Donna Farber, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University, has heard the stories, too.

“It is possible that the persisting virus in long COVID-19 may be at a low level – not enough to stimulate a potent immune response to clear the virus, but enough to cause symptoms. Activating the immune response therefore is therapeutic in directing viral clearance,” she says.

Dr. Farber explains that long COVID may be a bit like Lyme disease. Some patients with Lyme disease must take antibiotics for months before their symptoms disappear.

Dr. Griffin says there’s another possibility. Several studies have now shown that people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms develop autoantibodies. There’s a theory that SARS-CoV-2 may create an autoimmune condition that leads to long-term symptoms.

If that is the case, Dr. Griffin says, the vaccine may be helping the body to reset its tolerance to itself, “so maybe now you’re getting a healthy immune response.”

More studies are needed to know for sure.

Either way, the vaccines are a much-needed bit of hope for the long-COVID community, and Dr. Griffin tells his patients who are still worried that, at the very least, they’ll be protected from another SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Let’s apply the lessons from the AIDS crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic

In 2020, COVID-19 disrupted our medical system, and life in general. In the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic devastated communities and overwhelmed hospitals. There were lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic that can be applied to the current situation.

Patients with HIV-spectrum illness faced stigmatization and societal indifference, including rejection by family members, increased rates of suicide, fears of sexual and/or intrauterine transmission, substance abuse issues, and alterations of body image for those with wasting syndromes and disfiguring Kaposi lesions. AIDS prevention strategies such as the provision of condoms and needle exchange programs were controversial, and many caregivers exposed to contaminated fluids had to endure months of antiretroviral treatment.

Similar to the AIDS epidemic, the COVID-19 pandemic has had significant psychological implications for patients and caregivers. Patients with COVID-19 infections also face feelings of guilt over potentially exposing a family member to the virus; devastating socioeconomic issues; restrictive hospital visitation policies for family members; disease news oversaturation; and feelings of hopelessness. People with AIDS in the 1980s faced the possibility of dying alone, and there was initial skepticism about medications to treat HIV—just as some individuals are now uneasy about recently introduced coronavirus vaccines.

The similarities of both diseases allow us some foresight on how to deal with current COVID-19 issues. Looking back on the AIDS epidemic should teach us to prioritize attending to the mental health of sufferers and caregivers, creating advocacy and support groups for when a patient’s family is unavailable, instilling public confidence in treatment options, maintaining staff morale, addressing substance abuse (due to COVID-related stress), and depoliticizing prevention strategies. Addressing these issues is especially critical for minority populations.

As respected medical care leaders, we can provide and draw extra attention to the needs of patients’ family members and health care personnel during this COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, the distribution of vaccines will shorten some of our communal and professional distress.

Robert Frierson, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, KY

In 2020, COVID-19 disrupted our medical system, and life in general. In the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic devastated communities and overwhelmed hospitals. There were lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic that can be applied to the current situation.

Patients with HIV-spectrum illness faced stigmatization and societal indifference, including rejection by family members, increased rates of suicide, fears of sexual and/or intrauterine transmission, substance abuse issues, and alterations of body image for those with wasting syndromes and disfiguring Kaposi lesions. AIDS prevention strategies such as the provision of condoms and needle exchange programs were controversial, and many caregivers exposed to contaminated fluids had to endure months of antiretroviral treatment.

Similar to the AIDS epidemic, the COVID-19 pandemic has had significant psychological implications for patients and caregivers. Patients with COVID-19 infections also face feelings of guilt over potentially exposing a family member to the virus; devastating socioeconomic issues; restrictive hospital visitation policies for family members; disease news oversaturation; and feelings of hopelessness. People with AIDS in the 1980s faced the possibility of dying alone, and there was initial skepticism about medications to treat HIV—just as some individuals are now uneasy about recently introduced coronavirus vaccines.

The similarities of both diseases allow us some foresight on how to deal with current COVID-19 issues. Looking back on the AIDS epidemic should teach us to prioritize attending to the mental health of sufferers and caregivers, creating advocacy and support groups for when a patient’s family is unavailable, instilling public confidence in treatment options, maintaining staff morale, addressing substance abuse (due to COVID-related stress), and depoliticizing prevention strategies. Addressing these issues is especially critical for minority populations.

As respected medical care leaders, we can provide and draw extra attention to the needs of patients’ family members and health care personnel during this COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, the distribution of vaccines will shorten some of our communal and professional distress.

Robert Frierson, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, KY

In 2020, COVID-19 disrupted our medical system, and life in general. In the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic devastated communities and overwhelmed hospitals. There were lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic that can be applied to the current situation.

Patients with HIV-spectrum illness faced stigmatization and societal indifference, including rejection by family members, increased rates of suicide, fears of sexual and/or intrauterine transmission, substance abuse issues, and alterations of body image for those with wasting syndromes and disfiguring Kaposi lesions. AIDS prevention strategies such as the provision of condoms and needle exchange programs were controversial, and many caregivers exposed to contaminated fluids had to endure months of antiretroviral treatment.

Similar to the AIDS epidemic, the COVID-19 pandemic has had significant psychological implications for patients and caregivers. Patients with COVID-19 infections also face feelings of guilt over potentially exposing a family member to the virus; devastating socioeconomic issues; restrictive hospital visitation policies for family members; disease news oversaturation; and feelings of hopelessness. People with AIDS in the 1980s faced the possibility of dying alone, and there was initial skepticism about medications to treat HIV—just as some individuals are now uneasy about recently introduced coronavirus vaccines.

The similarities of both diseases allow us some foresight on how to deal with current COVID-19 issues. Looking back on the AIDS epidemic should teach us to prioritize attending to the mental health of sufferers and caregivers, creating advocacy and support groups for when a patient’s family is unavailable, instilling public confidence in treatment options, maintaining staff morale, addressing substance abuse (due to COVID-related stress), and depoliticizing prevention strategies. Addressing these issues is especially critical for minority populations.

As respected medical care leaders, we can provide and draw extra attention to the needs of patients’ family members and health care personnel during this COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, the distribution of vaccines will shorten some of our communal and professional distress.

Robert Frierson, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, KY

COVID-related immunization gaps portend return of preventable infections

Because of significant reduction in delivery of recommended childhood immunization during the pandemic, there is a risk for resurgence of vaccine preventable infections, including measles, pertussis, and polio, which can result in significant morbidity and mortality in children, reported Amy G. Feldman, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, and associates.

Will loss of herd immunity lead to vaccine deserts?

When asked to comment, pediatric infectious disease specialist Christopher J. Harrison, MD, said, “My concern is that we may see expansion of what I call ‘vaccine deserts.’ Vaccine deserts occur in underserved communities, areas with pockets of vaccine-hesitant families or among selected groups with difficult access to health care. These vaccine deserts have held a higher density of vulnerables due to low vaccine uptake, often giving rise to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, e.g., measles, mumps, pertussis. They are usually due to an index case arriving from another vaccine desert (a developing country or a developed country, U.S. or foreign) where the disease is still endemic or pockets of vaccine hesitancy/refusal exist. When detected, local outbreaks result in rapid responses from public/private health collaborations that limit the outbreak. But what if vaccine deserts became more generalized in the U.S. because of loss of vaccine-induced herd immunity in many more or larger areas of our communities because of pandemic-driven lack of vaccinations? That pandemic-driven indirect damage would further stress the health care system and the economy. And it may first show up in the older children whose vaccines were deferred in the first 4-6 months of the pandemic.”

Dr. Feldman and associates cited findings from a collaborative survey conducted by UNICEF, the World Health Organization, Gavi the Vaccine Alliance, the CDC, the Sabin Vaccine Institute, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which found that immunization programs experienced moderate to severe disruptions or terminations in at least 68 of 129 low and middle-income countries surveyed. According to the WHO, CDC, Red Cross, and GAVI, 94 million people presently are estimated to be at risk as a consequence of not receiving their measles vaccines following the suspensions.

“These national and international declines in routine immunizations have placed the global community at significant risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable infections (VPIs) including measles, polio, and pertussis, diseases which are more deadly, more contagious and have a higher reproductive factor (R0) amongst children than COVID-19,” the authors observed.

Dr. Feldman and associates outlined the horrible devastation that these VPI can cause in children, including significantly higher morbidity and mortality than adults, especially among those with immunodeficiencies. Neurologic deficits, paralysis, intellectual disabilities, and vision and hearing loss are just some of the permanent effects conveyed. “It is concerning to imagine how measles could spread across the United States when social distancing restriction[s] are relaxed and unvaccinated children return to school and usual community engagement,” they noted.

Collaborative engagement key to course correction

The authors found that primary care providers and public health communities are working not only to restore vaccine administration but also to restore confidence that vaccine delivery is safe in spite of COVID. In addition to recommending specific risk mitigation strategies for clinicians, they also suggested individual practitioners use electronic health records to identify patients with COVID-related lapses in vaccination, employ electronic health record–based parent notification of overdue immunizations, and offer distance-friendly vaccination options that include parking lot or drive-up window vaccine delivery.

Additionally, Dr. Feldman and colleagues recommended that local, state, regional, and national health systems use public service announcements via television and digital as well as social media platforms to convey important messages about the considerable health risks associated with vaccine avoidance and the availability of free or reduced-cost vaccination programs through the federally funded Vaccines For Children program for parents out of work or without insurance. Equally important is messaging around encouraging vaccine opportunities during all health care visits, whether they be subspecialty, urgent care, emergency room, or inpatient visits. In areas where access to clinics is limited, they urged the use of mobile clinics as well as additional focus on providing medical homes to children with poor access to care.

“A partial but expanding safety net may be developing spontaneously, i.e., practices and clinics based on a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model,” noted Dr. Harrison, professor of pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City, in an interview. “When lagging vaccinations were reported in mid-2020, we checked with a local hospital–based urban clinic and two suburban private practices modeled on PCMH. Each had noted a drastic drop in well checks in the first months of the pandemic. But with ill visits nearly nonexistent, they doubled down on maintaining health maintenance visits. Even though staff and provider work hours were limited, and families were less enthusiastic about well checks, momentum appears to have grown so that, by later in 2020, vaccine uptake rates were again comparable to 2019. So, some already seem to have answered the call, but practices/clinics remain hampered by months of reduced revenue needed to support staff, providers, PPE supplies, and added infection control needs,” he said.The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. Dr. Isakov disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. The other authors had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Harrison’s institution receives grant funding from GSK, Merck, and Pfizer for pediatric vaccine trials and pneumococcal seroprevalence studies on which he is an investigator.

pdnews@mdedge.com

Because of significant reduction in delivery of recommended childhood immunization during the pandemic, there is a risk for resurgence of vaccine preventable infections, including measles, pertussis, and polio, which can result in significant morbidity and mortality in children, reported Amy G. Feldman, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, and associates.

Will loss of herd immunity lead to vaccine deserts?

When asked to comment, pediatric infectious disease specialist Christopher J. Harrison, MD, said, “My concern is that we may see expansion of what I call ‘vaccine deserts.’ Vaccine deserts occur in underserved communities, areas with pockets of vaccine-hesitant families or among selected groups with difficult access to health care. These vaccine deserts have held a higher density of vulnerables due to low vaccine uptake, often giving rise to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, e.g., measles, mumps, pertussis. They are usually due to an index case arriving from another vaccine desert (a developing country or a developed country, U.S. or foreign) where the disease is still endemic or pockets of vaccine hesitancy/refusal exist. When detected, local outbreaks result in rapid responses from public/private health collaborations that limit the outbreak. But what if vaccine deserts became more generalized in the U.S. because of loss of vaccine-induced herd immunity in many more or larger areas of our communities because of pandemic-driven lack of vaccinations? That pandemic-driven indirect damage would further stress the health care system and the economy. And it may first show up in the older children whose vaccines were deferred in the first 4-6 months of the pandemic.”

Dr. Feldman and associates cited findings from a collaborative survey conducted by UNICEF, the World Health Organization, Gavi the Vaccine Alliance, the CDC, the Sabin Vaccine Institute, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which found that immunization programs experienced moderate to severe disruptions or terminations in at least 68 of 129 low and middle-income countries surveyed. According to the WHO, CDC, Red Cross, and GAVI, 94 million people presently are estimated to be at risk as a consequence of not receiving their measles vaccines following the suspensions.

“These national and international declines in routine immunizations have placed the global community at significant risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable infections (VPIs) including measles, polio, and pertussis, diseases which are more deadly, more contagious and have a higher reproductive factor (R0) amongst children than COVID-19,” the authors observed.

Dr. Feldman and associates outlined the horrible devastation that these VPI can cause in children, including significantly higher morbidity and mortality than adults, especially among those with immunodeficiencies. Neurologic deficits, paralysis, intellectual disabilities, and vision and hearing loss are just some of the permanent effects conveyed. “It is concerning to imagine how measles could spread across the United States when social distancing restriction[s] are relaxed and unvaccinated children return to school and usual community engagement,” they noted.

Collaborative engagement key to course correction

The authors found that primary care providers and public health communities are working not only to restore vaccine administration but also to restore confidence that vaccine delivery is safe in spite of COVID. In addition to recommending specific risk mitigation strategies for clinicians, they also suggested individual practitioners use electronic health records to identify patients with COVID-related lapses in vaccination, employ electronic health record–based parent notification of overdue immunizations, and offer distance-friendly vaccination options that include parking lot or drive-up window vaccine delivery.

Additionally, Dr. Feldman and colleagues recommended that local, state, regional, and national health systems use public service announcements via television and digital as well as social media platforms to convey important messages about the considerable health risks associated with vaccine avoidance and the availability of free or reduced-cost vaccination programs through the federally funded Vaccines For Children program for parents out of work or without insurance. Equally important is messaging around encouraging vaccine opportunities during all health care visits, whether they be subspecialty, urgent care, emergency room, or inpatient visits. In areas where access to clinics is limited, they urged the use of mobile clinics as well as additional focus on providing medical homes to children with poor access to care.

“A partial but expanding safety net may be developing spontaneously, i.e., practices and clinics based on a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model,” noted Dr. Harrison, professor of pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City, in an interview. “When lagging vaccinations were reported in mid-2020, we checked with a local hospital–based urban clinic and two suburban private practices modeled on PCMH. Each had noted a drastic drop in well checks in the first months of the pandemic. But with ill visits nearly nonexistent, they doubled down on maintaining health maintenance visits. Even though staff and provider work hours were limited, and families were less enthusiastic about well checks, momentum appears to have grown so that, by later in 2020, vaccine uptake rates were again comparable to 2019. So, some already seem to have answered the call, but practices/clinics remain hampered by months of reduced revenue needed to support staff, providers, PPE supplies, and added infection control needs,” he said.The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. Dr. Isakov disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. The other authors had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Harrison’s institution receives grant funding from GSK, Merck, and Pfizer for pediatric vaccine trials and pneumococcal seroprevalence studies on which he is an investigator.

pdnews@mdedge.com

Because of significant reduction in delivery of recommended childhood immunization during the pandemic, there is a risk for resurgence of vaccine preventable infections, including measles, pertussis, and polio, which can result in significant morbidity and mortality in children, reported Amy G. Feldman, MD, of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, and associates.

Will loss of herd immunity lead to vaccine deserts?

When asked to comment, pediatric infectious disease specialist Christopher J. Harrison, MD, said, “My concern is that we may see expansion of what I call ‘vaccine deserts.’ Vaccine deserts occur in underserved communities, areas with pockets of vaccine-hesitant families or among selected groups with difficult access to health care. These vaccine deserts have held a higher density of vulnerables due to low vaccine uptake, often giving rise to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, e.g., measles, mumps, pertussis. They are usually due to an index case arriving from another vaccine desert (a developing country or a developed country, U.S. or foreign) where the disease is still endemic or pockets of vaccine hesitancy/refusal exist. When detected, local outbreaks result in rapid responses from public/private health collaborations that limit the outbreak. But what if vaccine deserts became more generalized in the U.S. because of loss of vaccine-induced herd immunity in many more or larger areas of our communities because of pandemic-driven lack of vaccinations? That pandemic-driven indirect damage would further stress the health care system and the economy. And it may first show up in the older children whose vaccines were deferred in the first 4-6 months of the pandemic.”

Dr. Feldman and associates cited findings from a collaborative survey conducted by UNICEF, the World Health Organization, Gavi the Vaccine Alliance, the CDC, the Sabin Vaccine Institute, and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which found that immunization programs experienced moderate to severe disruptions or terminations in at least 68 of 129 low and middle-income countries surveyed. According to the WHO, CDC, Red Cross, and GAVI, 94 million people presently are estimated to be at risk as a consequence of not receiving their measles vaccines following the suspensions.

“These national and international declines in routine immunizations have placed the global community at significant risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable infections (VPIs) including measles, polio, and pertussis, diseases which are more deadly, more contagious and have a higher reproductive factor (R0) amongst children than COVID-19,” the authors observed.

Dr. Feldman and associates outlined the horrible devastation that these VPI can cause in children, including significantly higher morbidity and mortality than adults, especially among those with immunodeficiencies. Neurologic deficits, paralysis, intellectual disabilities, and vision and hearing loss are just some of the permanent effects conveyed. “It is concerning to imagine how measles could spread across the United States when social distancing restriction[s] are relaxed and unvaccinated children return to school and usual community engagement,” they noted.

Collaborative engagement key to course correction

The authors found that primary care providers and public health communities are working not only to restore vaccine administration but also to restore confidence that vaccine delivery is safe in spite of COVID. In addition to recommending specific risk mitigation strategies for clinicians, they also suggested individual practitioners use electronic health records to identify patients with COVID-related lapses in vaccination, employ electronic health record–based parent notification of overdue immunizations, and offer distance-friendly vaccination options that include parking lot or drive-up window vaccine delivery.

Additionally, Dr. Feldman and colleagues recommended that local, state, regional, and national health systems use public service announcements via television and digital as well as social media platforms to convey important messages about the considerable health risks associated with vaccine avoidance and the availability of free or reduced-cost vaccination programs through the federally funded Vaccines For Children program for parents out of work or without insurance. Equally important is messaging around encouraging vaccine opportunities during all health care visits, whether they be subspecialty, urgent care, emergency room, or inpatient visits. In areas where access to clinics is limited, they urged the use of mobile clinics as well as additional focus on providing medical homes to children with poor access to care.

“A partial but expanding safety net may be developing spontaneously, i.e., practices and clinics based on a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model,” noted Dr. Harrison, professor of pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City, in an interview. “When lagging vaccinations were reported in mid-2020, we checked with a local hospital–based urban clinic and two suburban private practices modeled on PCMH. Each had noted a drastic drop in well checks in the first months of the pandemic. But with ill visits nearly nonexistent, they doubled down on maintaining health maintenance visits. Even though staff and provider work hours were limited, and families were less enthusiastic about well checks, momentum appears to have grown so that, by later in 2020, vaccine uptake rates were again comparable to 2019. So, some already seem to have answered the call, but practices/clinics remain hampered by months of reduced revenue needed to support staff, providers, PPE supplies, and added infection control needs,” he said.The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. Dr. Isakov disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work. The other authors had no relevant disclosures. Dr. Harrison’s institution receives grant funding from GSK, Merck, and Pfizer for pediatric vaccine trials and pneumococcal seroprevalence studies on which he is an investigator.

pdnews@mdedge.com

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Federal Government Ramps Up COVID-19 Vaccination Programs

The Biden Administration launched the first phase of the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Program for COVID-19 Vaccination. Beginning February 15, FQHCs (including centers in the Urban Indian Health Program) began directly receiving vaccines.

The announcement coincided with a boost in vaccine supply for states, Tribes, and territories. In early February, the Biden Administration announced it would expand vaccine supply to 11 million doses nationwide, a 28% increase since January 20, when President Biden took office. According to a White House fact sheet, “The Administration is committing to maintaining this as the minimum supply level for the next three weeks, and we will continue to work with manufacturers in their efforts to ramp up supply.”

In February, President Biden and Vice President Harris travelled to Arizona and toured a vaccination site at State Farm Stadium in Glendale. Arizona, one of the first states to reach out for federal help from the new administration, has 15 counties and 22 Tribes with sovereign lands in the state. Those 37 entities work collaboratively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), said Major General Michael McGuire, head of the Arizona National Guard.

In his remarks during the tour, President Biden addressed equity, saying, “[I]t really does matter that we have access to the people who are most in need [and are] most affected by the COVID crisis, dying at faster rates, getting sick at faster rates, …but not being able to get into the mix. …Equity is a big thing.”

To that end, one of the programs under way is to stand up four vaccination centers for the Navajo Nation. Tammy Littrell, Acting Regional Administrator for FEMA, said the centers will help increase tribal members’ access to vaccination, as well as take the burden off from having to drive in “austere winter conditions.”

In addition to more vaccines, Indian Health Services (IHS) is allocating $1 billion it received to help with COVID-19 response. Of the $1 billion, $790 million will go to testing, contact tracing, containment, and mitigation, among other things. Another $210 million will support IHS, tribal, and urban Indian health programs for vaccine-related activities to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage. The money is part of the fifth round of supplemental COVID-19 funding from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. The funds transferred so far amount to nearly $3 billion.

According to IHS, the money can be used to scale up testing by public health, academic, commercial, and hospital laboratories, as well as community-based testing sites, mobile testing units, healthcare facilities, and other entities engaged in COVID-19 testing. The funds are also legally available to lease or purchase non-federally owned facilities to improve COVID-19 preparedness and response capability.

The Biden Administration launched the first phase of the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Program for COVID-19 Vaccination. Beginning February 15, FQHCs (including centers in the Urban Indian Health Program) began directly receiving vaccines.

The announcement coincided with a boost in vaccine supply for states, Tribes, and territories. In early February, the Biden Administration announced it would expand vaccine supply to 11 million doses nationwide, a 28% increase since January 20, when President Biden took office. According to a White House fact sheet, “The Administration is committing to maintaining this as the minimum supply level for the next three weeks, and we will continue to work with manufacturers in their efforts to ramp up supply.”

In February, President Biden and Vice President Harris travelled to Arizona and toured a vaccination site at State Farm Stadium in Glendale. Arizona, one of the first states to reach out for federal help from the new administration, has 15 counties and 22 Tribes with sovereign lands in the state. Those 37 entities work collaboratively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), said Major General Michael McGuire, head of the Arizona National Guard.

In his remarks during the tour, President Biden addressed equity, saying, “[I]t really does matter that we have access to the people who are most in need [and are] most affected by the COVID crisis, dying at faster rates, getting sick at faster rates, …but not being able to get into the mix. …Equity is a big thing.”

To that end, one of the programs under way is to stand up four vaccination centers for the Navajo Nation. Tammy Littrell, Acting Regional Administrator for FEMA, said the centers will help increase tribal members’ access to vaccination, as well as take the burden off from having to drive in “austere winter conditions.”

In addition to more vaccines, Indian Health Services (IHS) is allocating $1 billion it received to help with COVID-19 response. Of the $1 billion, $790 million will go to testing, contact tracing, containment, and mitigation, among other things. Another $210 million will support IHS, tribal, and urban Indian health programs for vaccine-related activities to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage. The money is part of the fifth round of supplemental COVID-19 funding from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. The funds transferred so far amount to nearly $3 billion.

According to IHS, the money can be used to scale up testing by public health, academic, commercial, and hospital laboratories, as well as community-based testing sites, mobile testing units, healthcare facilities, and other entities engaged in COVID-19 testing. The funds are also legally available to lease or purchase non-federally owned facilities to improve COVID-19 preparedness and response capability.

The Biden Administration launched the first phase of the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Program for COVID-19 Vaccination. Beginning February 15, FQHCs (including centers in the Urban Indian Health Program) began directly receiving vaccines.

The announcement coincided with a boost in vaccine supply for states, Tribes, and territories. In early February, the Biden Administration announced it would expand vaccine supply to 11 million doses nationwide, a 28% increase since January 20, when President Biden took office. According to a White House fact sheet, “The Administration is committing to maintaining this as the minimum supply level for the next three weeks, and we will continue to work with manufacturers in their efforts to ramp up supply.”

In February, President Biden and Vice President Harris travelled to Arizona and toured a vaccination site at State Farm Stadium in Glendale. Arizona, one of the first states to reach out for federal help from the new administration, has 15 counties and 22 Tribes with sovereign lands in the state. Those 37 entities work collaboratively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), said Major General Michael McGuire, head of the Arizona National Guard.

In his remarks during the tour, President Biden addressed equity, saying, “[I]t really does matter that we have access to the people who are most in need [and are] most affected by the COVID crisis, dying at faster rates, getting sick at faster rates, …but not being able to get into the mix. …Equity is a big thing.”

To that end, one of the programs under way is to stand up four vaccination centers for the Navajo Nation. Tammy Littrell, Acting Regional Administrator for FEMA, said the centers will help increase tribal members’ access to vaccination, as well as take the burden off from having to drive in “austere winter conditions.”

In addition to more vaccines, Indian Health Services (IHS) is allocating $1 billion it received to help with COVID-19 response. Of the $1 billion, $790 million will go to testing, contact tracing, containment, and mitigation, among other things. Another $210 million will support IHS, tribal, and urban Indian health programs for vaccine-related activities to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage. The money is part of the fifth round of supplemental COVID-19 funding from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. The funds transferred so far amount to nearly $3 billion.

According to IHS, the money can be used to scale up testing by public health, academic, commercial, and hospital laboratories, as well as community-based testing sites, mobile testing units, healthcare facilities, and other entities engaged in COVID-19 testing. The funds are also legally available to lease or purchase non-federally owned facilities to improve COVID-19 preparedness and response capability.

Anticipating the care adolescents will need

Adolescents are an increasingly diverse population reflecting changes in the racial, ethnic, and geopolitical milieus of the United States. The World Health Organization classifies adolescence as ages 10 to 19 years.1 However, given the complexity of adolescent development physically, behaviorally, emotionally, and socially, others propose that adolescence may extend to age 24.2

Recognizing the specific challenges adolescents face is key to providing comprehensive longitudinal health care. Moreover, creating an environment of trust helps to ensure open 2-way communication that can facilitate anticipatory guidance.

Our review focuses on common adolescent issues, including injury from vehicles and firearms, tobacco and substance misuse, obesity, behavioral health, sexual health, and social media use. We discuss current trends and recommend strategies to maximize health and wellness.

Start by framing the visit

Confidentiality

Laws governing confidentiality in adolescent health care vary by state. Be aware of the laws pertaining to your practice setting. In addition, health care facilities may have their own policies regarding consent and confidentiality in adolescent care. Discuss confidentiality with both an adolescent and the parent/guardian at the initial visit. And, to help avoid potential misunderstandings, let them know in advance what will (and will not) be divulged.

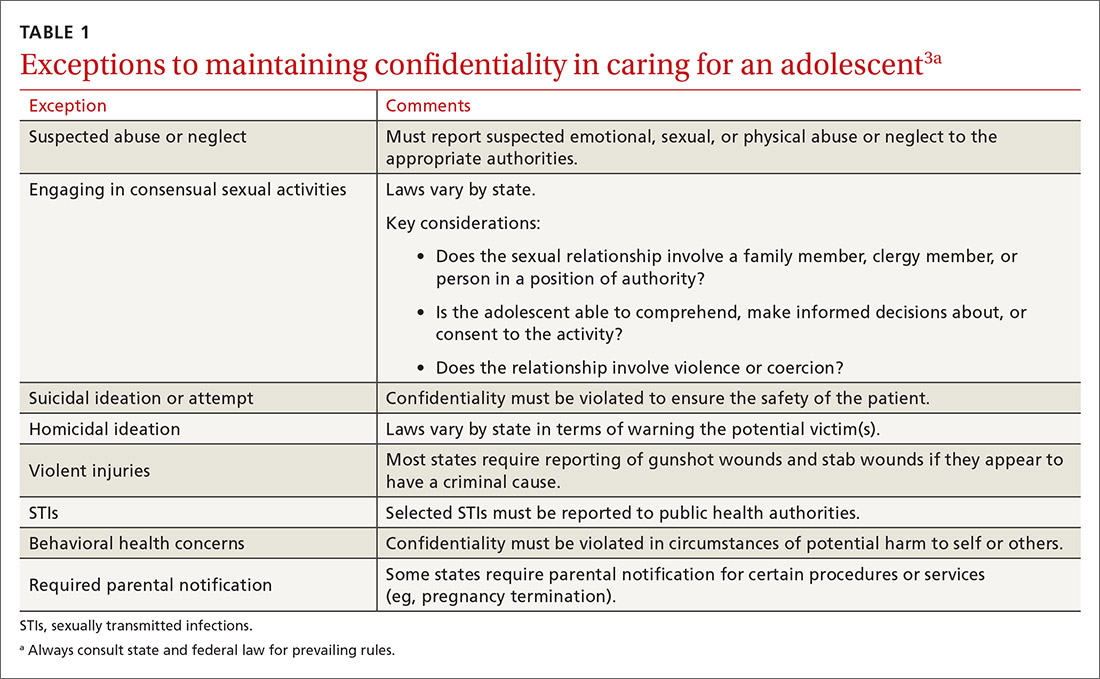

The American Academy of Pediatrics has developed a useful tip sheet regarding confidentiality laws (www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Documents/Confidentiality_Laws.pdf). Examples of required (conditional) disclosure include abuse and suicidal or homicidal ideations. Patients should understand that sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are reportable to public health authorities and that potentially injurious behaviors to self or others (eg, excessive drinking prior to driving) may also warrant disclosure(TABLE 13).

Privacy and general visit structure

Create a safe atmosphere where adolescents can discuss personal issues without fear of repercussion or judgment. While parents may prefer to be present during the visit, allowing for time to visit independently with an adolescent offers the opportunity to reinforce issues of privacy and confidentiality. Also discuss your office policies regarding electronic communication, phone communication, and relaying test results.

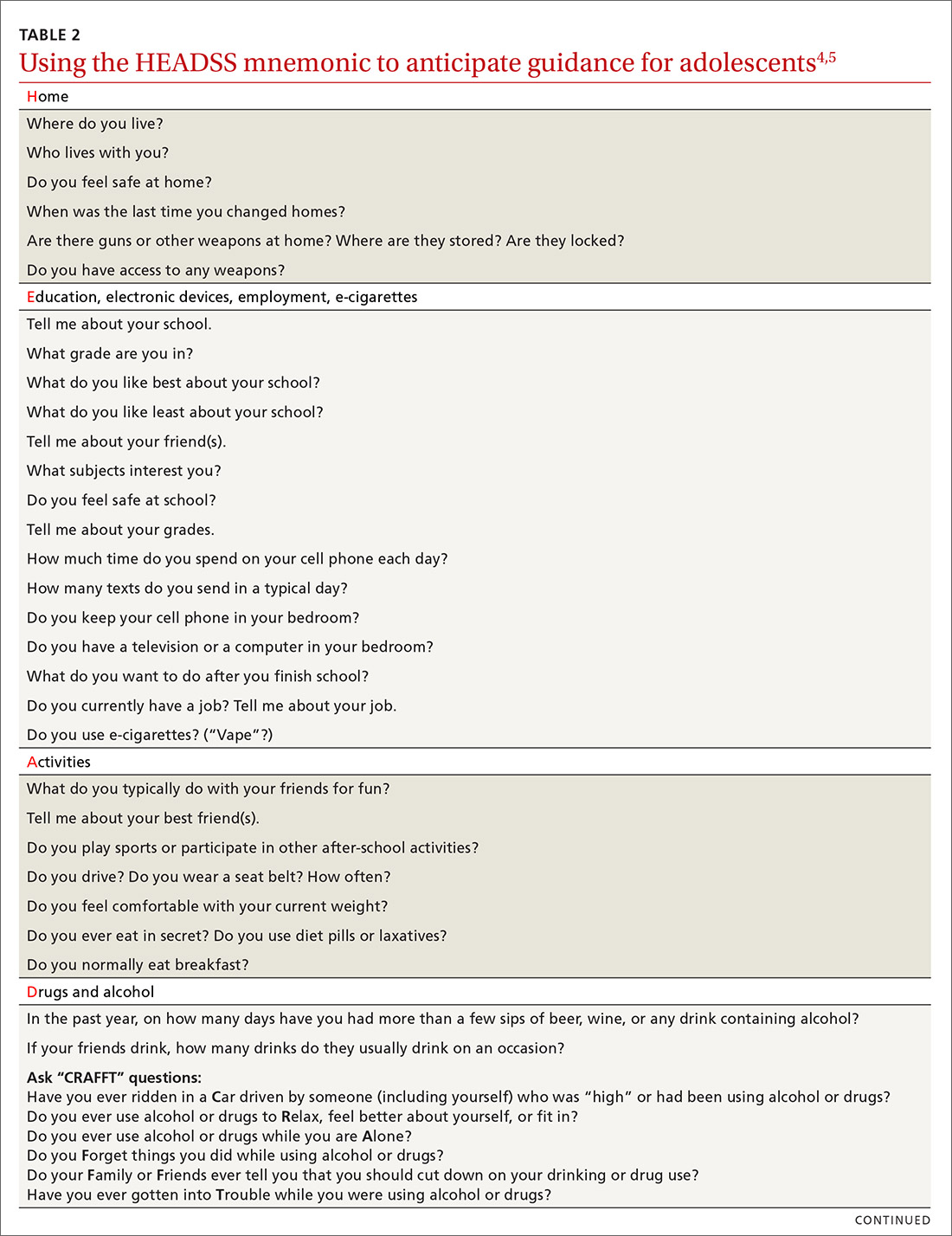

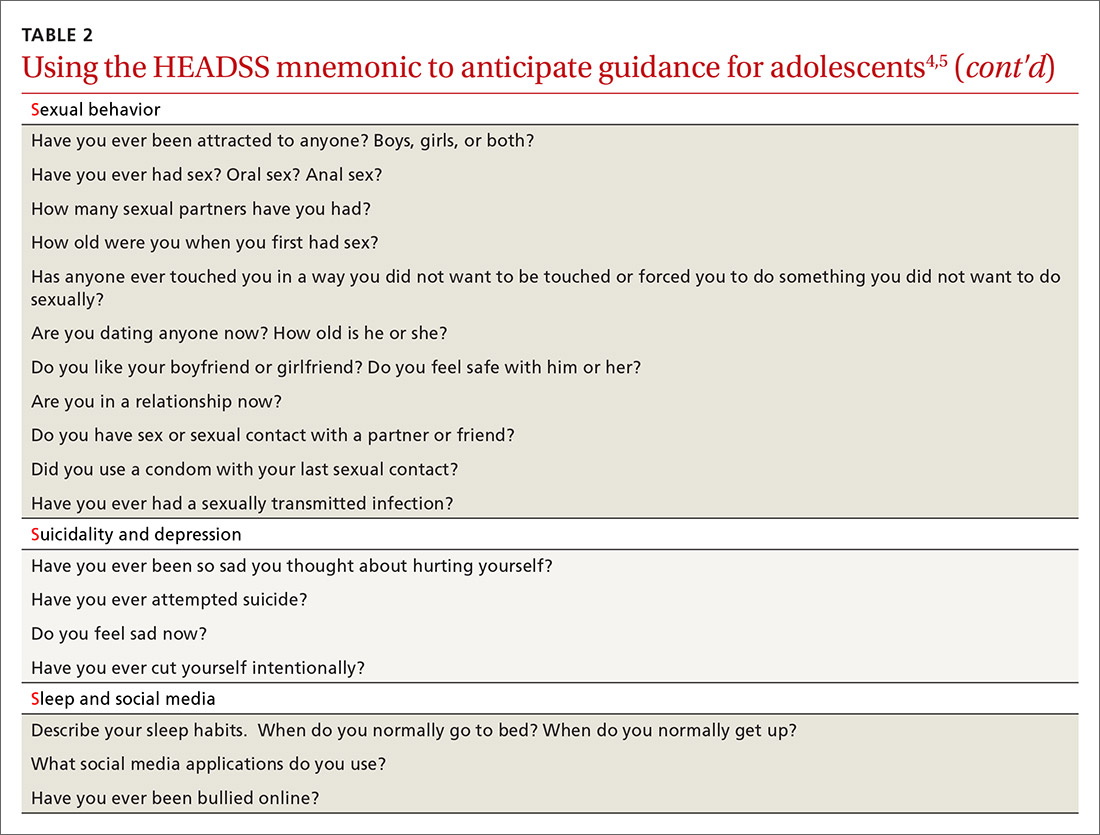

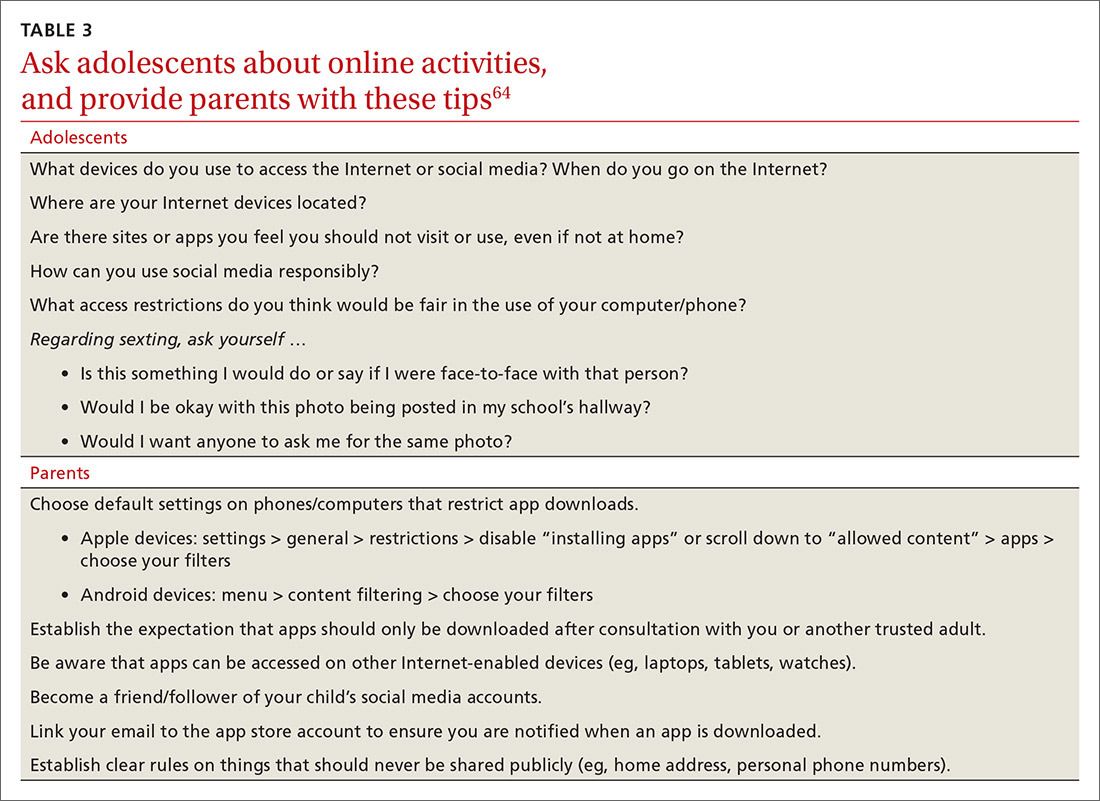

A useful paradigm for organizing a visit for routine adolescent care is to use an expanded version of the HEADSS mnemonic (TABLE 24,5), which includes questions about an adolescent’s Home, Education, Activities, Drug and alcohol use, Sexual behavior, Suicidality and depression, and other topics. Other validated screening tools include RAAPS (Rapid Adolescent Prevention Screening)6 (www.possibilitiesforchange.com/raaps/); the Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services7; and the Bright Futures recommendations for preventive care from the American Academy of Pediatrics.8 Below, we consider important topics addressed with the HEADSS approach.

Continue to: Injury from vehicles and firearms

Injury from vehicles and firearms

Motor vehicle accidents and firearm wounds are the 2 leading causes of adolescent injury. In 2016, of the more than 20,000 deaths in children and adolescents (ages 1-19 years), 20% were due to motor vehicle accidents (4074) and 15% were a result of firearm-related injuries (3143). Among firearm-related deaths, 60% were homicides, 35% were suicides, and 4% were due to accidental discharge.9 The rate of firearm-related deaths among American teens is 36 times greater than that of any other developed nation.9 Currently, 1 of every 3 US households with children younger than 18 has a firearm. Data suggest that in 43% of these households, the firearm is loaded and kept in an unlocked location.10

To aid anticipatory guidance, ask adolescents about firearm and seat belt use, drinking and driving, and suicidal thoughts (TABLE 24,5). Advise them to always wear seat belts whether driving or riding as a passenger. They should never drink and drive (or get in a car with someone who has been drinking). Advise parents that if firearms are present in the household, they should be kept in a secure, locked location. Weapons should be separated from ammunition and safety mechanisms should be engaged on all devices.

Tobacco and substance misuse

Tobacco use, the leading preventable cause of death in the United States,11 is responsible for more deaths than alcohol, motor vehicle accidents, suicides, homicides, and HIV disease combined.12 Most tobacco-associated mortality occurs in individuals who began smoking before the age of 18.12 Individuals who start smoking early are also more likely to continue smoking through adulthood.

Encouragingly, tobacco use has declined significantly among adolescents over the past several decades. Roughly 1 in 25 high school seniors reports daily tobacco use.13 Adolescent smoking behaviors are also changing dramatically with the increasing popularity of electronic cigarettes (“vaping”). Currently, more adolescents vape than smoke cigarettes.13 Vaping has additional health risks including toxic lung injury.

Multiple resources can help combat tobacco and nicotine use in adolescents. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that primary care clinicians intervene through education or brief counselling to prevent initiation of tobacco use in school-aged children and adolescents.14 Ask teens about tobacco and electronic cigarette use and encourage them to quit when use is acknowledged. Other helpful office-based tools are the “Quit Line” 800-QUIT-NOW and texting “Quit” to 47848. Smokefree teen (https://teen.smokefree.gov/) is a website that reviews the risks of tobacco and nicotine use and provides age-appropriate cessation tools and tips (including a smartphone app and a live-chat feature). Other useful information is available in a report from the Surgeon General on preventing tobacco use among young adults.15

Continue to: Alcohol use

Alcohol use. Three in 5 high school students report ever having used alcohol.13 As with tobacco, adolescent alcohol use has declined over the past decade. However, binge drinking (≥ 5 drinks on 1 occasion for males; ≥ 4 drinks on 1 occasion for females) remains a common high-risk behavior among adolescents (particularly college students). Based on the Monitoring the Future Survey, 1 in 6 high school seniors reported binge drinking in the past 2 weeks.13 While historically more common among males, rates of binge drinking are now basically similar between male and female adolescents.13

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has a screening and intervention guide specifically for adolescents.16

Illicit drug use. Half of adolescents report using an illicit drug by their senior year in high school.13 Marijuana is the most commonly used substance, and laws governing its use are rapidly changing across the United States. Marijuana is illegal in 10 states and legal in 10 states (and the District of Columbia). The remaining states have varying policies on the medical use of marijuana and the decriminalization of marijuana. In addition, cannabinoid (CBD) products are increasingly available. Frequent cannabis use in adolescence has an adverse impact on general executive function (compared with adult users) and learning.17 Marijuana may serve as a gateway drug in the abuse of other substances,18 and its use should be strongly discouraged in adolescents.

Of note, there has been a sharp rise in the illicit use of prescription drugs, particularly opioids, creating a public health emergency across the United States.19 In 2015, more than 4000 young people, ages 15 to 24, died from a drug-related overdose (> 50% of these attributable to opioids).20 Adolescents with a history of substance abuse and behavioral illness are at particular risk. Many adolescents who misuse opioids and other prescription drugs obtain them from friends and relatives.21