User login

HPV Positive Test: How to Address Patients’ Anxieties

Faced with a positive human papillomavirus (HPV) test, patients are quickly overwhelmed by anxiety-inducing questions. It is crucial to provide them with adequate responses to reassure them, emphasized Jean-Louis Mergui, MD, president of the International Federation for Colposcopy, during the press conference of the Congress of the French Society of Colposcopy and Cervico-Vaginal Pathology.

“Do I have cancer? When did I catch this papillomavirus? Is it dangerous for my partner? How do I get rid of it?” “Not everyone is equipped to answer these four questions. However, it is extremely important that healthcare professionals provide correct answers to patients so that they stop worrying,” Dr. Mergui explained.

Papillomavirus and Cancer

One of the first instincts of patients who receive a positive HPV test is to turn to the Internet. There, they read about “high-risk HPV, which is potentially oncogenic,” and become completely panicked, said Dr. Mergui.

However, among women, the probability of having a high-grade CIN3 lesion or higher on the cervix when the HPV test is positive is about 7%, according to the ATHENA study. “About 93% of patients do not have a severe lesion on the cervix. That’s why colposcopy is not performed on all patients. They need to be reassured,” said Dr. Mergui. When the papillomavirus persists, there is a risk for a cervical lesion. After 11 years, between 20% and 30% of patients develop a high-grade lesion on the cervix. However, on average, a high-risk HPV is spontaneously eliminated within 1-2 years. “After 14 months, 50% of women will test negative for their papillomavirus,” Dr. Mergui noted.

“High-risk HPV does not mean there is a lesion; it means there is a risk of developing a lesion on the cervix one day. That’s why these patients need to be monitored and explored,” he added.

In practice, when a patient aged between 30 and 65 years has a positive HPV test, cytology is performed to look for lesions. Only in the case of an abnormal smear, ASC-US, is colposcopy recommended. In the absence of a lesion, a control HPV test is conducted 1 year later to monitor virus persistence.

It should be noted that patients who have been treated for a cervical lesion have a five times higher risk of developing invasive cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer. Therefore, treated patients must be monitored once every 3 years for life.

Time of Infection

Many patients ask, “When did I catch this papillomavirus?” In response, Dr. Mergui first emphasized that HPV infection is common. “Between ages 15 and 30 years, most of us are infected with a high-risk HPV. When we look at the incidence between ages 15 and 25 years, every year, 20% of all young girls are infected with HPV, including 17% with high-risk HPV. The virus is usually caught within the first 5 years of sexual activity, and typically disappears after about a year,” he explained.

However, the most disturbing scenario for patients is when their last examination was negative, and there is no apparent reason for having caught the virus since then. Suspicion often falls on the partner. Once again, the gynecologist seeks to reassure.

It is possible that the last time screening was conducted, the virus was not sought (HPV test), but rather cervical lesions were sought by smear. However, a normal smear does not mean that the papillomavirus is not present. A negative cytology does not mean a negative HPV test. As we have seen, the virus is not always associated with the presence of a lesion, explained Dr. Mergui.

Also, having had a negative HPV test a few years earlier does not mean that one was not already infected. The HPV test determines the quantity of virus. Therefore, it is possible that the virus was present in small quantities that were without clinical significance (hence, a negative test). However, a few years later, the virus may have multiplied, and the HPV test became positive.

“Sometimes, the virus re-emerges 40, 50 years after infection due to age-related immune decline,” said Dr. Mergui. “So, just because the smear was negative or the HPV test was negative at the last examination does not mean that one was infected between the two.” Moreover, only 15% of couples have the same virus present on the penis or vagina, he pointed out.

Protecting One’s Partner

Once the diagnosis is made, it is often too late to protect the partner because they have already been infected. “It is certain that the partner will be infected or has already been infected because when the patient comes to you with a positive HPV test, she has already had sexual intercourse. It is worth noting that the virus can be transmitted through digital touching, and condoms are not very effective in preventing virus transmission,” said Dr. Mergui.

The speaker further clarified that the risk for men is much lower than that for women. “In women, about 40,000 lesions linked to high-risk HPV types, precancerous or cancerous, are observed every year. In men, this number is 1900. So, this represents 20 times fewer neoplastic lesions in men. The problem in men is oropharyngeal lesions, which are three times more common than in women. However, there is no screening for oropharyngeal cancer.”

So, when should the partner consult? Dr. Mergui advised consulting when there are clinically visible lesions (small warts, bumps, or ear, nose, and throat symptoms). “I do not recommend systematic examination of male or female partners,” he added.

Clearing the Virus

There are treatments for cervical lesions but not for papillomavirus infection.

“The only thing that can be suggested is quitting smoking, which increases viral clearance, thus reducing viral load. Also, the use of condoms helps improve viral clearance, but when women have a stable relationship, it seems unrealistic to think they will constantly use condoms. Finally, the prophylactic vaccine has been proposed, but it does not treat the infection. In fact, the real solution is to tell patients that they need to continue regular monitoring,” said Dr. Mergui.

“It should be noted that an ongoing study at the European level seems to show that when women who have undergone surgical treatment for a high-grade cervical lesion are vaccinated at the time of treatment or just after treatment, it reduces the risk of recurrence by 50%. So, the risk of recurrence is around 7%-8%. This strategy could be interesting, but for now, there is no official recommendation,” Dr. Mergui concluded.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Faced with a positive human papillomavirus (HPV) test, patients are quickly overwhelmed by anxiety-inducing questions. It is crucial to provide them with adequate responses to reassure them, emphasized Jean-Louis Mergui, MD, president of the International Federation for Colposcopy, during the press conference of the Congress of the French Society of Colposcopy and Cervico-Vaginal Pathology.

“Do I have cancer? When did I catch this papillomavirus? Is it dangerous for my partner? How do I get rid of it?” “Not everyone is equipped to answer these four questions. However, it is extremely important that healthcare professionals provide correct answers to patients so that they stop worrying,” Dr. Mergui explained.

Papillomavirus and Cancer

One of the first instincts of patients who receive a positive HPV test is to turn to the Internet. There, they read about “high-risk HPV, which is potentially oncogenic,” and become completely panicked, said Dr. Mergui.

However, among women, the probability of having a high-grade CIN3 lesion or higher on the cervix when the HPV test is positive is about 7%, according to the ATHENA study. “About 93% of patients do not have a severe lesion on the cervix. That’s why colposcopy is not performed on all patients. They need to be reassured,” said Dr. Mergui. When the papillomavirus persists, there is a risk for a cervical lesion. After 11 years, between 20% and 30% of patients develop a high-grade lesion on the cervix. However, on average, a high-risk HPV is spontaneously eliminated within 1-2 years. “After 14 months, 50% of women will test negative for their papillomavirus,” Dr. Mergui noted.

“High-risk HPV does not mean there is a lesion; it means there is a risk of developing a lesion on the cervix one day. That’s why these patients need to be monitored and explored,” he added.

In practice, when a patient aged between 30 and 65 years has a positive HPV test, cytology is performed to look for lesions. Only in the case of an abnormal smear, ASC-US, is colposcopy recommended. In the absence of a lesion, a control HPV test is conducted 1 year later to monitor virus persistence.

It should be noted that patients who have been treated for a cervical lesion have a five times higher risk of developing invasive cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer. Therefore, treated patients must be monitored once every 3 years for life.

Time of Infection

Many patients ask, “When did I catch this papillomavirus?” In response, Dr. Mergui first emphasized that HPV infection is common. “Between ages 15 and 30 years, most of us are infected with a high-risk HPV. When we look at the incidence between ages 15 and 25 years, every year, 20% of all young girls are infected with HPV, including 17% with high-risk HPV. The virus is usually caught within the first 5 years of sexual activity, and typically disappears after about a year,” he explained.

However, the most disturbing scenario for patients is when their last examination was negative, and there is no apparent reason for having caught the virus since then. Suspicion often falls on the partner. Once again, the gynecologist seeks to reassure.

It is possible that the last time screening was conducted, the virus was not sought (HPV test), but rather cervical lesions were sought by smear. However, a normal smear does not mean that the papillomavirus is not present. A negative cytology does not mean a negative HPV test. As we have seen, the virus is not always associated with the presence of a lesion, explained Dr. Mergui.

Also, having had a negative HPV test a few years earlier does not mean that one was not already infected. The HPV test determines the quantity of virus. Therefore, it is possible that the virus was present in small quantities that were without clinical significance (hence, a negative test). However, a few years later, the virus may have multiplied, and the HPV test became positive.

“Sometimes, the virus re-emerges 40, 50 years after infection due to age-related immune decline,” said Dr. Mergui. “So, just because the smear was negative or the HPV test was negative at the last examination does not mean that one was infected between the two.” Moreover, only 15% of couples have the same virus present on the penis or vagina, he pointed out.

Protecting One’s Partner

Once the diagnosis is made, it is often too late to protect the partner because they have already been infected. “It is certain that the partner will be infected or has already been infected because when the patient comes to you with a positive HPV test, she has already had sexual intercourse. It is worth noting that the virus can be transmitted through digital touching, and condoms are not very effective in preventing virus transmission,” said Dr. Mergui.

The speaker further clarified that the risk for men is much lower than that for women. “In women, about 40,000 lesions linked to high-risk HPV types, precancerous or cancerous, are observed every year. In men, this number is 1900. So, this represents 20 times fewer neoplastic lesions in men. The problem in men is oropharyngeal lesions, which are three times more common than in women. However, there is no screening for oropharyngeal cancer.”

So, when should the partner consult? Dr. Mergui advised consulting when there are clinically visible lesions (small warts, bumps, or ear, nose, and throat symptoms). “I do not recommend systematic examination of male or female partners,” he added.

Clearing the Virus

There are treatments for cervical lesions but not for papillomavirus infection.

“The only thing that can be suggested is quitting smoking, which increases viral clearance, thus reducing viral load. Also, the use of condoms helps improve viral clearance, but when women have a stable relationship, it seems unrealistic to think they will constantly use condoms. Finally, the prophylactic vaccine has been proposed, but it does not treat the infection. In fact, the real solution is to tell patients that they need to continue regular monitoring,” said Dr. Mergui.

“It should be noted that an ongoing study at the European level seems to show that when women who have undergone surgical treatment for a high-grade cervical lesion are vaccinated at the time of treatment or just after treatment, it reduces the risk of recurrence by 50%. So, the risk of recurrence is around 7%-8%. This strategy could be interesting, but for now, there is no official recommendation,” Dr. Mergui concluded.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Faced with a positive human papillomavirus (HPV) test, patients are quickly overwhelmed by anxiety-inducing questions. It is crucial to provide them with adequate responses to reassure them, emphasized Jean-Louis Mergui, MD, president of the International Federation for Colposcopy, during the press conference of the Congress of the French Society of Colposcopy and Cervico-Vaginal Pathology.

“Do I have cancer? When did I catch this papillomavirus? Is it dangerous for my partner? How do I get rid of it?” “Not everyone is equipped to answer these four questions. However, it is extremely important that healthcare professionals provide correct answers to patients so that they stop worrying,” Dr. Mergui explained.

Papillomavirus and Cancer

One of the first instincts of patients who receive a positive HPV test is to turn to the Internet. There, they read about “high-risk HPV, which is potentially oncogenic,” and become completely panicked, said Dr. Mergui.

However, among women, the probability of having a high-grade CIN3 lesion or higher on the cervix when the HPV test is positive is about 7%, according to the ATHENA study. “About 93% of patients do not have a severe lesion on the cervix. That’s why colposcopy is not performed on all patients. They need to be reassured,” said Dr. Mergui. When the papillomavirus persists, there is a risk for a cervical lesion. After 11 years, between 20% and 30% of patients develop a high-grade lesion on the cervix. However, on average, a high-risk HPV is spontaneously eliminated within 1-2 years. “After 14 months, 50% of women will test negative for their papillomavirus,” Dr. Mergui noted.

“High-risk HPV does not mean there is a lesion; it means there is a risk of developing a lesion on the cervix one day. That’s why these patients need to be monitored and explored,” he added.

In practice, when a patient aged between 30 and 65 years has a positive HPV test, cytology is performed to look for lesions. Only in the case of an abnormal smear, ASC-US, is colposcopy recommended. In the absence of a lesion, a control HPV test is conducted 1 year later to monitor virus persistence.

It should be noted that patients who have been treated for a cervical lesion have a five times higher risk of developing invasive cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer. Therefore, treated patients must be monitored once every 3 years for life.

Time of Infection

Many patients ask, “When did I catch this papillomavirus?” In response, Dr. Mergui first emphasized that HPV infection is common. “Between ages 15 and 30 years, most of us are infected with a high-risk HPV. When we look at the incidence between ages 15 and 25 years, every year, 20% of all young girls are infected with HPV, including 17% with high-risk HPV. The virus is usually caught within the first 5 years of sexual activity, and typically disappears after about a year,” he explained.

However, the most disturbing scenario for patients is when their last examination was negative, and there is no apparent reason for having caught the virus since then. Suspicion often falls on the partner. Once again, the gynecologist seeks to reassure.

It is possible that the last time screening was conducted, the virus was not sought (HPV test), but rather cervical lesions were sought by smear. However, a normal smear does not mean that the papillomavirus is not present. A negative cytology does not mean a negative HPV test. As we have seen, the virus is not always associated with the presence of a lesion, explained Dr. Mergui.

Also, having had a negative HPV test a few years earlier does not mean that one was not already infected. The HPV test determines the quantity of virus. Therefore, it is possible that the virus was present in small quantities that were without clinical significance (hence, a negative test). However, a few years later, the virus may have multiplied, and the HPV test became positive.

“Sometimes, the virus re-emerges 40, 50 years after infection due to age-related immune decline,” said Dr. Mergui. “So, just because the smear was negative or the HPV test was negative at the last examination does not mean that one was infected between the two.” Moreover, only 15% of couples have the same virus present on the penis or vagina, he pointed out.

Protecting One’s Partner

Once the diagnosis is made, it is often too late to protect the partner because they have already been infected. “It is certain that the partner will be infected or has already been infected because when the patient comes to you with a positive HPV test, she has already had sexual intercourse. It is worth noting that the virus can be transmitted through digital touching, and condoms are not very effective in preventing virus transmission,” said Dr. Mergui.

The speaker further clarified that the risk for men is much lower than that for women. “In women, about 40,000 lesions linked to high-risk HPV types, precancerous or cancerous, are observed every year. In men, this number is 1900. So, this represents 20 times fewer neoplastic lesions in men. The problem in men is oropharyngeal lesions, which are three times more common than in women. However, there is no screening for oropharyngeal cancer.”

So, when should the partner consult? Dr. Mergui advised consulting when there are clinically visible lesions (small warts, bumps, or ear, nose, and throat symptoms). “I do not recommend systematic examination of male or female partners,” he added.

Clearing the Virus

There are treatments for cervical lesions but not for papillomavirus infection.

“The only thing that can be suggested is quitting smoking, which increases viral clearance, thus reducing viral load. Also, the use of condoms helps improve viral clearance, but when women have a stable relationship, it seems unrealistic to think they will constantly use condoms. Finally, the prophylactic vaccine has been proposed, but it does not treat the infection. In fact, the real solution is to tell patients that they need to continue regular monitoring,” said Dr. Mergui.

“It should be noted that an ongoing study at the European level seems to show that when women who have undergone surgical treatment for a high-grade cervical lesion are vaccinated at the time of treatment or just after treatment, it reduces the risk of recurrence by 50%. So, the risk of recurrence is around 7%-8%. This strategy could be interesting, but for now, there is no official recommendation,” Dr. Mergui concluded.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

RNA Vaccines: Risk for Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Clarified

Cases of menstrual disorders, particularly unusually heavy menstrual bleeding, have been reported following RNA vaccination against COVID-19.

In France, this safety signal has been confirmed and added to the product characteristics summaries and vaccine leaflets for mRNA vaccines in October 2022. However, few studies have accurately measured this risk to date.

To address this gap in research, the French scientific interest group in the epidemiology of health products, ANSM-Cnam EPI-PHARE, conducted a study to assess the risk for heavy menstrual bleeding requiring hospitalization after COVID-19 vaccination in France.

“This study provides new evidence supporting the existence of an increased risk for heavy menstrual bleeding following COVID-19 vaccination with mRNA vaccines,” wrote the authors.

Study Details

The study included all women aged 15-50 years who were diagnosed with heavy menstrual bleeding in the hospital between May 12, 2021, and August 31, 2022. Participants were identified in the National Health Data System, and the study population totaled 4610 women.

Each participant was randomly matched with as many as 30 women who had not been hospitalized for abnormal genital bleeding and had similar characteristics in terms of age, department of residence, social deprivation index of the commune of residence, and contraceptive method.

Women who had a recent pregnancy, hysterectomy, or coagulation disorder within the specified time frames were excluded.

At the time of the study, 71% of cases and 70% of controls had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Among vaccinated participants, 68% and 66%, respectively, received a vaccination dose (first or second dose). An mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty or Spikevax) was the last vaccine for 99.8% of the population.

Increased Risk

Compared with control women, those hospitalized for heavy menstrual bleeding were more likely to have received their last dose of mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty or Spikevax) in the previous 1-3 months. This association was observed for vaccination doses (odds ratio [OR], 1.20), indicating a 20% increased risk, but it was not found for booster doses (OR, 1.07).

This association was particularly notable for women residing in socially disadvantaged communities (OR, 1.28) and women not using hormonal contraception (OR, 1.28).

The risk did not appear to be increased beyond 3 months after vaccination. Researchers noted that the increased risk may have occurred earlier, considering the likely interval between initial symptoms and hospitalization.

Assuming a causal relationship, the estimated number of cases attributable to vaccination was 8 cases per million vaccinated women, totaling 103 cases among all women aged 15-50 years who were vaccinated in France between May 12, 2021, and August 31, 2022.

As of the study date and in the 3 years before the study, none of the authors had any conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of menstrual disorders, particularly unusually heavy menstrual bleeding, have been reported following RNA vaccination against COVID-19.

In France, this safety signal has been confirmed and added to the product characteristics summaries and vaccine leaflets for mRNA vaccines in October 2022. However, few studies have accurately measured this risk to date.

To address this gap in research, the French scientific interest group in the epidemiology of health products, ANSM-Cnam EPI-PHARE, conducted a study to assess the risk for heavy menstrual bleeding requiring hospitalization after COVID-19 vaccination in France.

“This study provides new evidence supporting the existence of an increased risk for heavy menstrual bleeding following COVID-19 vaccination with mRNA vaccines,” wrote the authors.

Study Details

The study included all women aged 15-50 years who were diagnosed with heavy menstrual bleeding in the hospital between May 12, 2021, and August 31, 2022. Participants were identified in the National Health Data System, and the study population totaled 4610 women.

Each participant was randomly matched with as many as 30 women who had not been hospitalized for abnormal genital bleeding and had similar characteristics in terms of age, department of residence, social deprivation index of the commune of residence, and contraceptive method.

Women who had a recent pregnancy, hysterectomy, or coagulation disorder within the specified time frames were excluded.

At the time of the study, 71% of cases and 70% of controls had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Among vaccinated participants, 68% and 66%, respectively, received a vaccination dose (first or second dose). An mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty or Spikevax) was the last vaccine for 99.8% of the population.

Increased Risk

Compared with control women, those hospitalized for heavy menstrual bleeding were more likely to have received their last dose of mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty or Spikevax) in the previous 1-3 months. This association was observed for vaccination doses (odds ratio [OR], 1.20), indicating a 20% increased risk, but it was not found for booster doses (OR, 1.07).

This association was particularly notable for women residing in socially disadvantaged communities (OR, 1.28) and women not using hormonal contraception (OR, 1.28).

The risk did not appear to be increased beyond 3 months after vaccination. Researchers noted that the increased risk may have occurred earlier, considering the likely interval between initial symptoms and hospitalization.

Assuming a causal relationship, the estimated number of cases attributable to vaccination was 8 cases per million vaccinated women, totaling 103 cases among all women aged 15-50 years who were vaccinated in France between May 12, 2021, and August 31, 2022.

As of the study date and in the 3 years before the study, none of the authors had any conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cases of menstrual disorders, particularly unusually heavy menstrual bleeding, have been reported following RNA vaccination against COVID-19.

In France, this safety signal has been confirmed and added to the product characteristics summaries and vaccine leaflets for mRNA vaccines in October 2022. However, few studies have accurately measured this risk to date.

To address this gap in research, the French scientific interest group in the epidemiology of health products, ANSM-Cnam EPI-PHARE, conducted a study to assess the risk for heavy menstrual bleeding requiring hospitalization after COVID-19 vaccination in France.

“This study provides new evidence supporting the existence of an increased risk for heavy menstrual bleeding following COVID-19 vaccination with mRNA vaccines,” wrote the authors.

Study Details

The study included all women aged 15-50 years who were diagnosed with heavy menstrual bleeding in the hospital between May 12, 2021, and August 31, 2022. Participants were identified in the National Health Data System, and the study population totaled 4610 women.

Each participant was randomly matched with as many as 30 women who had not been hospitalized for abnormal genital bleeding and had similar characteristics in terms of age, department of residence, social deprivation index of the commune of residence, and contraceptive method.

Women who had a recent pregnancy, hysterectomy, or coagulation disorder within the specified time frames were excluded.

At the time of the study, 71% of cases and 70% of controls had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Among vaccinated participants, 68% and 66%, respectively, received a vaccination dose (first or second dose). An mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty or Spikevax) was the last vaccine for 99.8% of the population.

Increased Risk

Compared with control women, those hospitalized for heavy menstrual bleeding were more likely to have received their last dose of mRNA vaccine (Comirnaty or Spikevax) in the previous 1-3 months. This association was observed for vaccination doses (odds ratio [OR], 1.20), indicating a 20% increased risk, but it was not found for booster doses (OR, 1.07).

This association was particularly notable for women residing in socially disadvantaged communities (OR, 1.28) and women not using hormonal contraception (OR, 1.28).

The risk did not appear to be increased beyond 3 months after vaccination. Researchers noted that the increased risk may have occurred earlier, considering the likely interval between initial symptoms and hospitalization.

Assuming a causal relationship, the estimated number of cases attributable to vaccination was 8 cases per million vaccinated women, totaling 103 cases among all women aged 15-50 years who were vaccinated in France between May 12, 2021, and August 31, 2022.

As of the study date and in the 3 years before the study, none of the authors had any conflicts of interest with pharmaceutical companies.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Microbiome Impacts Vaccine Responses

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

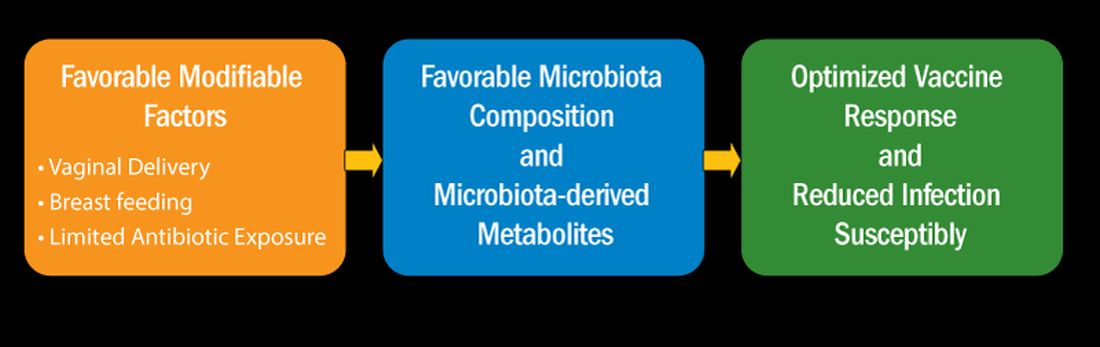

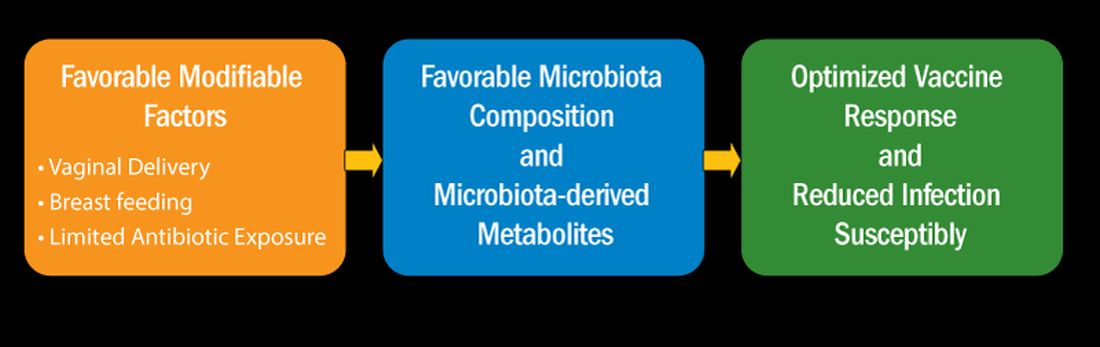

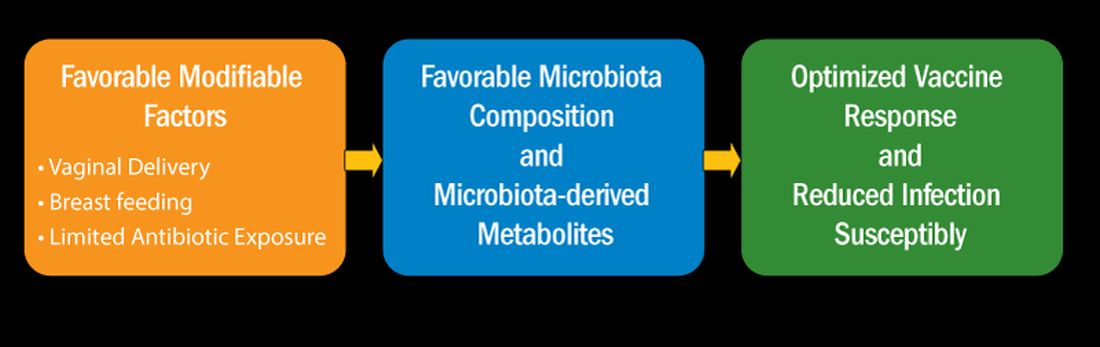

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

HPV Vaccine Shown to Be Highly Effective in Girls Years Later

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.

- Programs to provide Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine, began in the United Kingdom in 2007.

- After the initiation of the programs, administering the vaccine became part of routine care for girls starting at age 12 years.

- Researchers collected data in 2020 from 447,845 women born between 1988 and 1996 from the Scottish cervical cancer screening system to assess the efficacy of Cervarix in lowering rates of cervical cancer.

- They correlated the rate of cervical cancer per 100,000 person-years with data on women regarding vaccination status, age when vaccinated, and deprivation in areas like income, housing, and health.

TAKEAWAY:

- No cases of cervical cancer were found among women who were immunized at ages 12 or 13 years, no matter how many doses they received.

- Women who were immunized between ages 14 and 18 years and received three doses had fewer instances of cervical cancer compared with unvaccinated women regardless of deprivation status (3.2 cases per 100,00 women vs 8.4 cases per 100,000).

IN PRACTICE:

“Continued participation in screening and monitoring of outcomes is required, however, to assess the effects of changes in vaccines used and dosage schedules since the start of vaccination in Scotland in 2008 and the longevity of protection the vaccines offer.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Timothy J. Palmer, PhD, Scottish Clinical Lead for Cervical Screening at Public Health Scotland.

LIMITATIONS:

Only 14,645 women had received just one or two doses, which may have affected the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Public Health Scotland. A coauthor reports attending an advisory board meeting for HOLOGIC and Vaccitech. Her institution received research funding or gratis support funding from Cepheid, Euroimmun, GeneFirst, SelfScreen, Hiantis, Seegene, Roche, Hologic, and Vaccitech in the past 3 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.

- Programs to provide Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine, began in the United Kingdom in 2007.

- After the initiation of the programs, administering the vaccine became part of routine care for girls starting at age 12 years.

- Researchers collected data in 2020 from 447,845 women born between 1988 and 1996 from the Scottish cervical cancer screening system to assess the efficacy of Cervarix in lowering rates of cervical cancer.

- They correlated the rate of cervical cancer per 100,000 person-years with data on women regarding vaccination status, age when vaccinated, and deprivation in areas like income, housing, and health.

TAKEAWAY:

- No cases of cervical cancer were found among women who were immunized at ages 12 or 13 years, no matter how many doses they received.

- Women who were immunized between ages 14 and 18 years and received three doses had fewer instances of cervical cancer compared with unvaccinated women regardless of deprivation status (3.2 cases per 100,00 women vs 8.4 cases per 100,000).

IN PRACTICE:

“Continued participation in screening and monitoring of outcomes is required, however, to assess the effects of changes in vaccines used and dosage schedules since the start of vaccination in Scotland in 2008 and the longevity of protection the vaccines offer.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Timothy J. Palmer, PhD, Scottish Clinical Lead for Cervical Screening at Public Health Scotland.

LIMITATIONS:

Only 14,645 women had received just one or two doses, which may have affected the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Public Health Scotland. A coauthor reports attending an advisory board meeting for HOLOGIC and Vaccitech. Her institution received research funding or gratis support funding from Cepheid, Euroimmun, GeneFirst, SelfScreen, Hiantis, Seegene, Roche, Hologic, and Vaccitech in the past 3 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide.

- Programs to provide Cervarix, a bivalent vaccine, began in the United Kingdom in 2007.

- After the initiation of the programs, administering the vaccine became part of routine care for girls starting at age 12 years.

- Researchers collected data in 2020 from 447,845 women born between 1988 and 1996 from the Scottish cervical cancer screening system to assess the efficacy of Cervarix in lowering rates of cervical cancer.

- They correlated the rate of cervical cancer per 100,000 person-years with data on women regarding vaccination status, age when vaccinated, and deprivation in areas like income, housing, and health.

TAKEAWAY:

- No cases of cervical cancer were found among women who were immunized at ages 12 or 13 years, no matter how many doses they received.

- Women who were immunized between ages 14 and 18 years and received three doses had fewer instances of cervical cancer compared with unvaccinated women regardless of deprivation status (3.2 cases per 100,00 women vs 8.4 cases per 100,000).

IN PRACTICE:

“Continued participation in screening and monitoring of outcomes is required, however, to assess the effects of changes in vaccines used and dosage schedules since the start of vaccination in Scotland in 2008 and the longevity of protection the vaccines offer.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Timothy J. Palmer, PhD, Scottish Clinical Lead for Cervical Screening at Public Health Scotland.

LIMITATIONS:

Only 14,645 women had received just one or two doses, which may have affected the statistical analysis.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by Public Health Scotland. A coauthor reports attending an advisory board meeting for HOLOGIC and Vaccitech. Her institution received research funding or gratis support funding from Cepheid, Euroimmun, GeneFirst, SelfScreen, Hiantis, Seegene, Roche, Hologic, and Vaccitech in the past 3 years.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Rubella Screening in Pregnancy No Longer Recommended in Italy

If a pregnant woman contracts rubella in the first 17 weeks of pregnancy, then the risk for congenital rubella in the newborn — which may entail spontaneous abortion, intrauterine death, or severe fetal malformations — is as high as 80%. This risk once frightened patients and clinicians in Italy. Thanks to widespread population vaccination, however, the World Health Organization declared the elimination of endemic transmission of rubella in Italy in 2021. The Italian National Institute of Health took note, and the recent update of the Guidelines for the Management of Physiological Pregnancy no longer recommends offering rubella screening to all pregnant women.

The Rubeo Test

The rubeo test, an analysis for detecting antibodies in the blood produced by vaccination or a past rubella infection, traditionally forms part of the examination package that every doctor prescribes to expectant patients at the beginning of pregnancy. If the test shows that the woman is not vaccinated and has never encountered the virus, making her susceptible to the risk for infection, according to the previous edition of the Guidelines, then the test should be repeated at 17 weeks of gestation. The purpose is to detect any rubella contracted during pregnancy and offer the woman multidisciplinary counseling in the case of a high risk for severe fetal damage. Infection contracted after the 17th week, however, poses only a minimal risk for congenital deafness. There is no treatment to prevent vertical transmission in case of infection during pregnancy.

For women at risk for infection, the old Guidelines also recommended planning vaccination postnatally, with the prospect of protecting future pregnancies. Rubella vaccination is contraindicated during pregnancy because the vaccine could be teratogenic.

Recommendation Update

In the early ‘90s, universal vaccination against rubella for newborns was introduced in Italy. It became one of the 10 mandatory pediatric vaccinations in 2017. In June 2022, the Ministry of Health reported a vaccination coverage of 93.8% among children aged 24 months, a coverage of 93.3% for the first dose, and a coverage of 89.0% for the second dose in the 2003 birth cohort.

“Rubella is a notifiable disease, and in 2013, the newly activated national surveillance system detected one case of congenital rubella per 100,000 newborns. From 2018 onward, no cases have been reported,” said Vittorio Basevi, a gynecologist of the Perinatal Technical-Scientific Advisory Commission in the Emilia Romagna Region and coordinator of the Technical-Scientific Committee that developed the updated Guidelines. “Thanks to extensive vaccination coverage, the infection no longer circulates in Italy. Based on these data, we decided not to offer screening to pregnant women anymore.”

The recommendation to offer rubella vaccination post partum to women without documentation of two doses or previous infection remains confirmed.

Patients Born Abroad

How should one handle the care of a pregnant woman born in a country where universal rubella vaccination is not provided? The likelihood that she is susceptible to infection is higher than the that of the general Italian population. “On the other hand, since the virus no longer circulates in our country, the probability of contracting the virus during pregnancy is negligible, unless she has recently traveled to her country of origin or come into contact with family members who recently arrived in Italy,” said Dr. Basevi. “The Guidelines refer to offering screening to all pregnant women. In specific cases, it is up to the treating physician to adopt the conduct they deem appropriate in science and conscience.”

This article was translated from Univadis Italy, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

If a pregnant woman contracts rubella in the first 17 weeks of pregnancy, then the risk for congenital rubella in the newborn — which may entail spontaneous abortion, intrauterine death, or severe fetal malformations — is as high as 80%. This risk once frightened patients and clinicians in Italy. Thanks to widespread population vaccination, however, the World Health Organization declared the elimination of endemic transmission of rubella in Italy in 2021. The Italian National Institute of Health took note, and the recent update of the Guidelines for the Management of Physiological Pregnancy no longer recommends offering rubella screening to all pregnant women.

The Rubeo Test

The rubeo test, an analysis for detecting antibodies in the blood produced by vaccination or a past rubella infection, traditionally forms part of the examination package that every doctor prescribes to expectant patients at the beginning of pregnancy. If the test shows that the woman is not vaccinated and has never encountered the virus, making her susceptible to the risk for infection, according to the previous edition of the Guidelines, then the test should be repeated at 17 weeks of gestation. The purpose is to detect any rubella contracted during pregnancy and offer the woman multidisciplinary counseling in the case of a high risk for severe fetal damage. Infection contracted after the 17th week, however, poses only a minimal risk for congenital deafness. There is no treatment to prevent vertical transmission in case of infection during pregnancy.

For women at risk for infection, the old Guidelines also recommended planning vaccination postnatally, with the prospect of protecting future pregnancies. Rubella vaccination is contraindicated during pregnancy because the vaccine could be teratogenic.

Recommendation Update

In the early ‘90s, universal vaccination against rubella for newborns was introduced in Italy. It became one of the 10 mandatory pediatric vaccinations in 2017. In June 2022, the Ministry of Health reported a vaccination coverage of 93.8% among children aged 24 months, a coverage of 93.3% for the first dose, and a coverage of 89.0% for the second dose in the 2003 birth cohort.

“Rubella is a notifiable disease, and in 2013, the newly activated national surveillance system detected one case of congenital rubella per 100,000 newborns. From 2018 onward, no cases have been reported,” said Vittorio Basevi, a gynecologist of the Perinatal Technical-Scientific Advisory Commission in the Emilia Romagna Region and coordinator of the Technical-Scientific Committee that developed the updated Guidelines. “Thanks to extensive vaccination coverage, the infection no longer circulates in Italy. Based on these data, we decided not to offer screening to pregnant women anymore.”

The recommendation to offer rubella vaccination post partum to women without documentation of two doses or previous infection remains confirmed.

Patients Born Abroad

How should one handle the care of a pregnant woman born in a country where universal rubella vaccination is not provided? The likelihood that she is susceptible to infection is higher than the that of the general Italian population. “On the other hand, since the virus no longer circulates in our country, the probability of contracting the virus during pregnancy is negligible, unless she has recently traveled to her country of origin or come into contact with family members who recently arrived in Italy,” said Dr. Basevi. “The Guidelines refer to offering screening to all pregnant women. In specific cases, it is up to the treating physician to adopt the conduct they deem appropriate in science and conscience.”

This article was translated from Univadis Italy, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

If a pregnant woman contracts rubella in the first 17 weeks of pregnancy, then the risk for congenital rubella in the newborn — which may entail spontaneous abortion, intrauterine death, or severe fetal malformations — is as high as 80%. This risk once frightened patients and clinicians in Italy. Thanks to widespread population vaccination, however, the World Health Organization declared the elimination of endemic transmission of rubella in Italy in 2021. The Italian National Institute of Health took note, and the recent update of the Guidelines for the Management of Physiological Pregnancy no longer recommends offering rubella screening to all pregnant women.

The Rubeo Test

The rubeo test, an analysis for detecting antibodies in the blood produced by vaccination or a past rubella infection, traditionally forms part of the examination package that every doctor prescribes to expectant patients at the beginning of pregnancy. If the test shows that the woman is not vaccinated and has never encountered the virus, making her susceptible to the risk for infection, according to the previous edition of the Guidelines, then the test should be repeated at 17 weeks of gestation. The purpose is to detect any rubella contracted during pregnancy and offer the woman multidisciplinary counseling in the case of a high risk for severe fetal damage. Infection contracted after the 17th week, however, poses only a minimal risk for congenital deafness. There is no treatment to prevent vertical transmission in case of infection during pregnancy.

For women at risk for infection, the old Guidelines also recommended planning vaccination postnatally, with the prospect of protecting future pregnancies. Rubella vaccination is contraindicated during pregnancy because the vaccine could be teratogenic.

Recommendation Update

In the early ‘90s, universal vaccination against rubella for newborns was introduced in Italy. It became one of the 10 mandatory pediatric vaccinations in 2017. In June 2022, the Ministry of Health reported a vaccination coverage of 93.8% among children aged 24 months, a coverage of 93.3% for the first dose, and a coverage of 89.0% for the second dose in the 2003 birth cohort.

“Rubella is a notifiable disease, and in 2013, the newly activated national surveillance system detected one case of congenital rubella per 100,000 newborns. From 2018 onward, no cases have been reported,” said Vittorio Basevi, a gynecologist of the Perinatal Technical-Scientific Advisory Commission in the Emilia Romagna Region and coordinator of the Technical-Scientific Committee that developed the updated Guidelines. “Thanks to extensive vaccination coverage, the infection no longer circulates in Italy. Based on these data, we decided not to offer screening to pregnant women anymore.”

The recommendation to offer rubella vaccination post partum to women without documentation of two doses or previous infection remains confirmed.

Patients Born Abroad

How should one handle the care of a pregnant woman born in a country where universal rubella vaccination is not provided? The likelihood that she is susceptible to infection is higher than the that of the general Italian population. “On the other hand, since the virus no longer circulates in our country, the probability of contracting the virus during pregnancy is negligible, unless she has recently traveled to her country of origin or come into contact with family members who recently arrived in Italy,” said Dr. Basevi. “The Guidelines refer to offering screening to all pregnant women. In specific cases, it is up to the treating physician to adopt the conduct they deem appropriate in science and conscience.”

This article was translated from Univadis Italy, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Coming Soon: The First mRNA Vaccine for Melanoma?

Moderna and Merck have presented promising results from their phase 2b clinical trial that investigated a combination of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine and a cancer drug for the treatment of melanoma.

Is mRNA set to shake up the world of cancer treatment? This is certainly what Moderna seems to think; the pharmaceutical company has published the results of a phase 2b trial combining its mRNA vaccine (mRNA-4157 [V940]) with Merck’s cancer drug KEYTRUDA. While these are not the final results but rather mid-term data from the 3-year follow-up, they are somewhat promising. The randomized KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 clinical trial involves patients with high-risk (stage III/IV) melanoma following complete resection.

Relapse Risk Halved

Treatment with mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with pembrolizumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in recurrence-free survival, reducing the risk for recurrence or death by 49%, compared with pembrolizumab alone. T, reducing the risk of developing distant metastasis or death by 62%. “The KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study was the first demonstration of efficacy for an investigational mRNA cancer treatment in a randomized clinical trial and the first combination therapy to show a significant benefit over pembrolizumab alone in adjuvant melanoma,” said Kyle Holen, MD, Moderna’s senior vice president, after presenting these results.

Side Effects

The combined treatment also did not demonstrate more significant side effects than pembrolizumab alone. The number of patients reporting treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater was similar between the arms (25% for mRNA-4157 [V940] with pembrolizumab vs 20% for KEYTRUDA alone). The most common adverse events of any grade attributed to mRNA-4157 (V940) were fatigue (60.6%), injection site pain (56.7%), and chills (49%). Based on data from the phase 2b KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study, the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency granted breakthrough therapy designation and recognition under the the Priority Medicines scheme, respectively, for mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with KEYTRUDA for the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk melanoma.

Phase 3 Trial

In July, Moderna and Merck announced the launch of a phase 3 trial, assessing “mRNA-4157 [V940] in combination with pembrolizumab as adjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk resected melanoma [stages IIB-IV].” Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s director general, believes that an mRNA vaccine for melanoma could be available in 2025.

Other Cancer Vaccines

Moderna is not the only laboratory to set its sights on developing a vaccine for cancer. In May, BioNTech, in partnership with Roche, proposed a phase 1 clinical trial of a vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer in Nature. In June, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology›s conference, Transgene presented its conclusions concerning its viral vector vaccines against ENT and papillomavirus-linked cancers. And in September, Ose Immunotherapeutics made headlines with its vaccine for advanced lung cancer.

This article was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Moderna and Merck have presented promising results from their phase 2b clinical trial that investigated a combination of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine and a cancer drug for the treatment of melanoma.

Is mRNA set to shake up the world of cancer treatment? This is certainly what Moderna seems to think; the pharmaceutical company has published the results of a phase 2b trial combining its mRNA vaccine (mRNA-4157 [V940]) with Merck’s cancer drug KEYTRUDA. While these are not the final results but rather mid-term data from the 3-year follow-up, they are somewhat promising. The randomized KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 clinical trial involves patients with high-risk (stage III/IV) melanoma following complete resection.

Relapse Risk Halved

Treatment with mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with pembrolizumab led to a clinically meaningful improvement in recurrence-free survival, reducing the risk for recurrence or death by 49%, compared with pembrolizumab alone. T, reducing the risk of developing distant metastasis or death by 62%. “The KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study was the first demonstration of efficacy for an investigational mRNA cancer treatment in a randomized clinical trial and the first combination therapy to show a significant benefit over pembrolizumab alone in adjuvant melanoma,” said Kyle Holen, MD, Moderna’s senior vice president, after presenting these results.

Side Effects

The combined treatment also did not demonstrate more significant side effects than pembrolizumab alone. The number of patients reporting treatment-related adverse events of grade 3 or greater was similar between the arms (25% for mRNA-4157 [V940] with pembrolizumab vs 20% for KEYTRUDA alone). The most common adverse events of any grade attributed to mRNA-4157 (V940) were fatigue (60.6%), injection site pain (56.7%), and chills (49%). Based on data from the phase 2b KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 study, the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency granted breakthrough therapy designation and recognition under the the Priority Medicines scheme, respectively, for mRNA-4157 (V940) in combination with KEYTRUDA for the adjuvant treatment of patients with high-risk melanoma.

Phase 3 Trial

In July, Moderna and Merck announced the launch of a phase 3 trial, assessing “mRNA-4157 [V940] in combination with pembrolizumab as adjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk resected melanoma [stages IIB-IV].” Stéphane Bancel, Moderna’s director general, believes that an mRNA vaccine for melanoma could be available in 2025.

Other Cancer Vaccines

Moderna is not the only laboratory to set its sights on developing a vaccine for cancer. In May, BioNTech, in partnership with Roche, proposed a phase 1 clinical trial of a vaccine targeting pancreatic cancer in Nature. In June, at the American Society of Clinical Oncology›s conference, Transgene presented its conclusions concerning its viral vector vaccines against ENT and papillomavirus-linked cancers. And in September, Ose Immunotherapeutics made headlines with its vaccine for advanced lung cancer.

This article was translated from Univadis France, which is part of the Medscape Professional Network.

Moderna and Merck have presented promising results from their phase 2b clinical trial that investigated a combination of a messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine and a cancer drug for the treatment of melanoma.

Is mRNA set to shake up the world of cancer treatment? This is certainly what Moderna seems to think; the pharmaceutical company has published the results of a phase 2b trial combining its mRNA vaccine (mRNA-4157 [V940]) with Merck’s cancer drug KEYTRUDA. While these are not the final results but rather mid-term data from the 3-year follow-up, they are somewhat promising. The randomized KEYNOTE-942/mRNA-4157-P201 clinical trial involves patients with high-risk (stage III/IV) melanoma following complete resection.

Relapse Risk Halved