User login

COVID vaccines lower risk of serious illness in children

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

METHODOLOGY:

- SARS-CoV-2 infection can severely affect children who have certain chronic conditions.

- Researchers assessed the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing emergency ED visits and hospitalizations associated with the illness from July 2022 to September 2023.

- They drew data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network, which conducts population-based, prospective surveillance for acute respiratory illness in children at seven pediatric medical centers.

- The period assessed was the first year vaccines were authorized for children aged 6 months to 4 years; during that period, several Omicron subvariants arose.

- Researchers used data from 7,434 infants and children; data included patients’ vaccine status and their test results for SARS-CoV-2.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 7,434 infants and children who had an acute respiratory illness and were hospitalized or visited the ED, 387 had COVID-19.

- Children who received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine were 40% less likely to have a COVID-19-associated hospitalization or ED visit compared with unvaccinated youth.

- One dose of a COVID-19 vaccine reduced ED visits and hospitalizations by 31%.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings in this report support the recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination for all children aged ≥6 months and highlight the importance of completion of a primary series for young children,” the researchers reported.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Heidi L. Moline, MD, of the CDC.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the number of children with antibodies and immunity against SARS-CoV-2 has grown, vaccine effectiveness rates in the study may no longer be as relevant. Children with preexisting chronic conditions may be more likely to be vaccinated and receive medical attention. The low rates of vaccination may have prevented researchers from conducting a more detailed analysis. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine requires three doses, whereas Moderna’s requires two doses; this may have skewed the estimated efficacy of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report a variety of potential conflicts of interest, which are detailed in the article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

METHODOLOGY:

- SARS-CoV-2 infection can severely affect children who have certain chronic conditions.

- Researchers assessed the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing emergency ED visits and hospitalizations associated with the illness from July 2022 to September 2023.

- They drew data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network, which conducts population-based, prospective surveillance for acute respiratory illness in children at seven pediatric medical centers.

- The period assessed was the first year vaccines were authorized for children aged 6 months to 4 years; during that period, several Omicron subvariants arose.

- Researchers used data from 7,434 infants and children; data included patients’ vaccine status and their test results for SARS-CoV-2.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 7,434 infants and children who had an acute respiratory illness and were hospitalized or visited the ED, 387 had COVID-19.

- Children who received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine were 40% less likely to have a COVID-19-associated hospitalization or ED visit compared with unvaccinated youth.

- One dose of a COVID-19 vaccine reduced ED visits and hospitalizations by 31%.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings in this report support the recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination for all children aged ≥6 months and highlight the importance of completion of a primary series for young children,” the researchers reported.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Heidi L. Moline, MD, of the CDC.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the number of children with antibodies and immunity against SARS-CoV-2 has grown, vaccine effectiveness rates in the study may no longer be as relevant. Children with preexisting chronic conditions may be more likely to be vaccinated and receive medical attention. The low rates of vaccination may have prevented researchers from conducting a more detailed analysis. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine requires three doses, whereas Moderna’s requires two doses; this may have skewed the estimated efficacy of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report a variety of potential conflicts of interest, which are detailed in the article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

METHODOLOGY:

- SARS-CoV-2 infection can severely affect children who have certain chronic conditions.

- Researchers assessed the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing emergency ED visits and hospitalizations associated with the illness from July 2022 to September 2023.

- They drew data from the New Vaccine Surveillance Network, which conducts population-based, prospective surveillance for acute respiratory illness in children at seven pediatric medical centers.

- The period assessed was the first year vaccines were authorized for children aged 6 months to 4 years; during that period, several Omicron subvariants arose.

- Researchers used data from 7,434 infants and children; data included patients’ vaccine status and their test results for SARS-CoV-2.

TAKEAWAY:

- Of the 7,434 infants and children who had an acute respiratory illness and were hospitalized or visited the ED, 387 had COVID-19.

- Children who received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine were 40% less likely to have a COVID-19-associated hospitalization or ED visit compared with unvaccinated youth.

- One dose of a COVID-19 vaccine reduced ED visits and hospitalizations by 31%.

IN PRACTICE:

“The findings in this report support the recommendation for COVID-19 vaccination for all children aged ≥6 months and highlight the importance of completion of a primary series for young children,” the researchers reported.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Heidi L. Moline, MD, of the CDC.

LIMITATIONS:

Because the number of children with antibodies and immunity against SARS-CoV-2 has grown, vaccine effectiveness rates in the study may no longer be as relevant. Children with preexisting chronic conditions may be more likely to be vaccinated and receive medical attention. The low rates of vaccination may have prevented researchers from conducting a more detailed analysis. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine requires three doses, whereas Moderna’s requires two doses; this may have skewed the estimated efficacy of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report a variety of potential conflicts of interest, which are detailed in the article.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID vaccination protects B cell–deficient patients through T-cell responses

TOPLINE:

In individuals with low B-cell counts, T cells have enhanced responses to COVID-19 vaccination and may help prevent severe disease after infection.

METHODOLOGY:

- How the immune systems of B cell–deficient patients respond to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination is not fully understood.

- Researchers evaluated anti–SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses in 33 patients treated with rituximab (RTX), 12 patients with common variable immune deficiency, and 44 controls.

- The study analyzed effector and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 after infection and vaccination.

TAKEAWAY:

- All B cell–deficient individuals (those treated with RTX or those with a diagnosis of common variable immune deficiency) had increased effector and memory T-cell responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, compared with controls.

- Patients treated with RTX who were vaccinated against COVID-19 had 4.8-fold reduced odds of moderate or severe disease. (These data were not available for patients with common variable immune deficiency.)

- RTX treatment was associated with a decrease in preexisting T-cell immunity in unvaccinated patients, regardless of prior infection with SARS-CoV-2.

- This association was not found in vaccinated patients treated with RTX.

IN PRACTICE:

“[These findings] provide support for vaccination in this vulnerable population and demonstrate the potential benefit of vaccine-induced CD8+ T-cell responses on reducing disease severity from SARS-CoV-2 infection in the absence of spike protein–specific antibodies,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was published online on November 29 in Science Translational Medicine. The first author is Reza Zonozi, MD, who conducted the research while at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and is now in private practice in northern Virginia.

LIMITATIONS:

Researchers did not obtain specimens from patients with common variable immune deficiency after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Only a small subset of immunophenotyped participants had subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard Medical School, the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation and E. Schwartz; the Lambertus Family Foundation; and S. Edgerly and P. Edgerly. Four authors reported relationships with pharmaceutical companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In individuals with low B-cell counts, T cells have enhanced responses to COVID-19 vaccination and may help prevent severe disease after infection.

METHODOLOGY:

- How the immune systems of B cell–deficient patients respond to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination is not fully understood.

- Researchers evaluated anti–SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses in 33 patients treated with rituximab (RTX), 12 patients with common variable immune deficiency, and 44 controls.

- The study analyzed effector and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 after infection and vaccination.

TAKEAWAY:

- All B cell–deficient individuals (those treated with RTX or those with a diagnosis of common variable immune deficiency) had increased effector and memory T-cell responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, compared with controls.

- Patients treated with RTX who were vaccinated against COVID-19 had 4.8-fold reduced odds of moderate or severe disease. (These data were not available for patients with common variable immune deficiency.)

- RTX treatment was associated with a decrease in preexisting T-cell immunity in unvaccinated patients, regardless of prior infection with SARS-CoV-2.

- This association was not found in vaccinated patients treated with RTX.

IN PRACTICE:

“[These findings] provide support for vaccination in this vulnerable population and demonstrate the potential benefit of vaccine-induced CD8+ T-cell responses on reducing disease severity from SARS-CoV-2 infection in the absence of spike protein–specific antibodies,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was published online on November 29 in Science Translational Medicine. The first author is Reza Zonozi, MD, who conducted the research while at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and is now in private practice in northern Virginia.

LIMITATIONS:

Researchers did not obtain specimens from patients with common variable immune deficiency after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Only a small subset of immunophenotyped participants had subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard Medical School, the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation and E. Schwartz; the Lambertus Family Foundation; and S. Edgerly and P. Edgerly. Four authors reported relationships with pharmaceutical companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

In individuals with low B-cell counts, T cells have enhanced responses to COVID-19 vaccination and may help prevent severe disease after infection.

METHODOLOGY:

- How the immune systems of B cell–deficient patients respond to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination is not fully understood.

- Researchers evaluated anti–SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses in 33 patients treated with rituximab (RTX), 12 patients with common variable immune deficiency, and 44 controls.

- The study analyzed effector and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 after infection and vaccination.

TAKEAWAY:

- All B cell–deficient individuals (those treated with RTX or those with a diagnosis of common variable immune deficiency) had increased effector and memory T-cell responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, compared with controls.

- Patients treated with RTX who were vaccinated against COVID-19 had 4.8-fold reduced odds of moderate or severe disease. (These data were not available for patients with common variable immune deficiency.)

- RTX treatment was associated with a decrease in preexisting T-cell immunity in unvaccinated patients, regardless of prior infection with SARS-CoV-2.

- This association was not found in vaccinated patients treated with RTX.

IN PRACTICE:

“[These findings] provide support for vaccination in this vulnerable population and demonstrate the potential benefit of vaccine-induced CD8+ T-cell responses on reducing disease severity from SARS-CoV-2 infection in the absence of spike protein–specific antibodies,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was published online on November 29 in Science Translational Medicine. The first author is Reza Zonozi, MD, who conducted the research while at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and is now in private practice in northern Virginia.

LIMITATIONS:

Researchers did not obtain specimens from patients with common variable immune deficiency after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Only a small subset of immunophenotyped participants had subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Ragon Institute of Massachusetts General Hospital, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Harvard Medical School, the Mark and Lisa Schwartz Foundation and E. Schwartz; the Lambertus Family Foundation; and S. Edgerly and P. Edgerly. Four authors reported relationships with pharmaceutical companies including AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Childhood immunization schedule includes new RSV, mpox, meningococcal, and pneumococcal vaccines

The immunization schedule for children and adolescents, summarized as an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement in the journal Pediatrics, contains new entries for the monoclonal antibody immunization nirsevimab for respiratory syncytial virus in infants, the maternal RSV vaccine RSVpreF for pregnant people, the mpox vaccine for adolescents, the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine, the 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20), and the pentavalent meningococcal vaccine (MenACWY-TT/MenB-FHbp).

A number of immunizations have been deleted from the 2024 schedule, including the pentavalent meningococcal vaccine MenABCWY because of a discontinuation in its distribution in the United States, the bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, the diphtheria and tetanus toxoids adsorbed vaccine, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), and the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

The 2024 childhood and adolescent immunization schedule, also approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American Academy of Physician Associates, and National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, is published each year based on current recommendations that have been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration.

In a press release, the AAP said the CDC decided to publish the recommendations early to ensure health providers are able to administer immunizations and that they are covered by insurance. They also referenced CDC reports that found vaccination rates for kindergarteners have not bounced back since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and vaccine exemptions for the 2022-2023 school year were at an “all-time high.”

RSV

New to the schedule are the recently approved RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab for infants and the RSV vaccine RSVpreF for pregnant people. According to the CDC’s combined immunization schedule for 2024, the timing of the infant RSV immunization is heavily dependent upon when and whether a RSV vaccine was administered during pregnancy. The RSV vaccine should be routinely given between 32 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation between September and January in most of the United States with the caveat that either the maternal vaccine or the infant immunization is recommended.

Infants born between October and March in most of the United States are eligible for the RSV immunization within 14 days of birth if the pregnant parent did not receive an RSV vaccine during pregnancy, or if the parent received the vaccine in the 14 days prior to birth. For infants born between April and September RSV immunization is recommended prior to the start of RSV season.

The immunization is also recommended for infants who were hospitalized for conditions such as prematurity after birth between October and March, infants aged 8-19 months who are undergoing medical support related to prematurity, infants aged 8-19 months who are severely immunocompromised, and infants aged 9-19 months who are American Indian or Alaska Native, and infants undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

Mpox

Another new addition to the schedule is mpox, which is recommended for adolescents 18 years or older who are at risk for mpox infection, including gay, bisexual, nonbinary, transgender, or other individuals who have developed a sexually transmitted disease within the last 6 months, had more than one sexual partner, or engaged in sex in a commercial sex venue or public space with confirmed mpox transmission.

Currently, mpox vaccination during pregnancy is not recommended due to a lack of safety data on the vaccine during pregnancy; however, the CDC noted pregnant persons who have been exposed to any of the risk factors above may receive the vaccine.

COVID, influenza, pneumococcal vaccines

The COVID-19 vaccine recommendations were updated to reflect the 2023-2023 formulation of the vaccine. Unvaccinated children between 6 months and 4 years of age will now receive the 2023-2024 formula mRNA vaccines, which includes the two-dose Moderna vaccine and three-dose Pfizer vaccine for use in that age group. Children with a previous history of COVID-19 vaccination are eligible to receive an age-appropriate COVID-19 vaccine from the 2023-2024 formulation, and children between 5-11 years old and 12-18 years old can receive a single dose of an mRNA vaccine regardless of vaccine history; unvaccinated children 12-18 years old are also eligible to receive the two-dose Novavax vaccine.

For influenza, the schedule refers to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations released in August, with a note indicating that individuals with an egg allergy can receive another vaccine recommended for their age group without concerns for safety.

The pneumococcal vaccine recommendations have removed PCV13 completely, with updates on the PCV15, PCV20, and PPSV23 in sections on routine vaccination, catch-up vaccination, and special situations. The poliovirus section has also seen its catch-up section revised with a recommendation to complete a vaccination series in adolescents 18 years old known or suspected to have an incomplete series, and to count trivalent oral poliovirus vaccines and OPV administered before April 2016 toward U.S. vaccination requirements.

‘Timely and necessary’ changes

Michael Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital Research Institute, said in an interview that the committee that developed the immunization schedule was thorough in its recommendations for children and adolescents.

“The additions are timely and necessary as the landscape of vaccines for children changes,” he said.

Bonnie M. Word, MD, director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic, said that the immunization schedule “sets the standard and provides clarification and uniformity for administration of all recommended vaccines for U.S. children.”

The U.S. immunization program “is one of the best success stories in medicine,” Dr. Wood said. She noted it is important for providers to become familiar with these vaccines and their indications “to provide advice and be able to respond to questions of parents and/or patients.

“Often patients spend more time with office staff than the physician. It is helpful to make sure everyone in the office understands the importance of and the rationale for immunizing, so families hear consistent messaging,” she said.

Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Word reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The immunization schedule for children and adolescents, summarized as an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement in the journal Pediatrics, contains new entries for the monoclonal antibody immunization nirsevimab for respiratory syncytial virus in infants, the maternal RSV vaccine RSVpreF for pregnant people, the mpox vaccine for adolescents, the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine, the 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20), and the pentavalent meningococcal vaccine (MenACWY-TT/MenB-FHbp).

A number of immunizations have been deleted from the 2024 schedule, including the pentavalent meningococcal vaccine MenABCWY because of a discontinuation in its distribution in the United States, the bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, the diphtheria and tetanus toxoids adsorbed vaccine, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), and the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

The 2024 childhood and adolescent immunization schedule, also approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American Academy of Physician Associates, and National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, is published each year based on current recommendations that have been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration.

In a press release, the AAP said the CDC decided to publish the recommendations early to ensure health providers are able to administer immunizations and that they are covered by insurance. They also referenced CDC reports that found vaccination rates for kindergarteners have not bounced back since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and vaccine exemptions for the 2022-2023 school year were at an “all-time high.”

RSV

New to the schedule are the recently approved RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab for infants and the RSV vaccine RSVpreF for pregnant people. According to the CDC’s combined immunization schedule for 2024, the timing of the infant RSV immunization is heavily dependent upon when and whether a RSV vaccine was administered during pregnancy. The RSV vaccine should be routinely given between 32 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation between September and January in most of the United States with the caveat that either the maternal vaccine or the infant immunization is recommended.

Infants born between October and March in most of the United States are eligible for the RSV immunization within 14 days of birth if the pregnant parent did not receive an RSV vaccine during pregnancy, or if the parent received the vaccine in the 14 days prior to birth. For infants born between April and September RSV immunization is recommended prior to the start of RSV season.

The immunization is also recommended for infants who were hospitalized for conditions such as prematurity after birth between October and March, infants aged 8-19 months who are undergoing medical support related to prematurity, infants aged 8-19 months who are severely immunocompromised, and infants aged 9-19 months who are American Indian or Alaska Native, and infants undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

Mpox

Another new addition to the schedule is mpox, which is recommended for adolescents 18 years or older who are at risk for mpox infection, including gay, bisexual, nonbinary, transgender, or other individuals who have developed a sexually transmitted disease within the last 6 months, had more than one sexual partner, or engaged in sex in a commercial sex venue or public space with confirmed mpox transmission.

Currently, mpox vaccination during pregnancy is not recommended due to a lack of safety data on the vaccine during pregnancy; however, the CDC noted pregnant persons who have been exposed to any of the risk factors above may receive the vaccine.

COVID, influenza, pneumococcal vaccines

The COVID-19 vaccine recommendations were updated to reflect the 2023-2023 formulation of the vaccine. Unvaccinated children between 6 months and 4 years of age will now receive the 2023-2024 formula mRNA vaccines, which includes the two-dose Moderna vaccine and three-dose Pfizer vaccine for use in that age group. Children with a previous history of COVID-19 vaccination are eligible to receive an age-appropriate COVID-19 vaccine from the 2023-2024 formulation, and children between 5-11 years old and 12-18 years old can receive a single dose of an mRNA vaccine regardless of vaccine history; unvaccinated children 12-18 years old are also eligible to receive the two-dose Novavax vaccine.

For influenza, the schedule refers to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations released in August, with a note indicating that individuals with an egg allergy can receive another vaccine recommended for their age group without concerns for safety.

The pneumococcal vaccine recommendations have removed PCV13 completely, with updates on the PCV15, PCV20, and PPSV23 in sections on routine vaccination, catch-up vaccination, and special situations. The poliovirus section has also seen its catch-up section revised with a recommendation to complete a vaccination series in adolescents 18 years old known or suspected to have an incomplete series, and to count trivalent oral poliovirus vaccines and OPV administered before April 2016 toward U.S. vaccination requirements.

‘Timely and necessary’ changes

Michael Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital Research Institute, said in an interview that the committee that developed the immunization schedule was thorough in its recommendations for children and adolescents.

“The additions are timely and necessary as the landscape of vaccines for children changes,” he said.

Bonnie M. Word, MD, director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic, said that the immunization schedule “sets the standard and provides clarification and uniformity for administration of all recommended vaccines for U.S. children.”

The U.S. immunization program “is one of the best success stories in medicine,” Dr. Wood said. She noted it is important for providers to become familiar with these vaccines and their indications “to provide advice and be able to respond to questions of parents and/or patients.

“Often patients spend more time with office staff than the physician. It is helpful to make sure everyone in the office understands the importance of and the rationale for immunizing, so families hear consistent messaging,” she said.

Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Word reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

The immunization schedule for children and adolescents, summarized as an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement in the journal Pediatrics, contains new entries for the monoclonal antibody immunization nirsevimab for respiratory syncytial virus in infants, the maternal RSV vaccine RSVpreF for pregnant people, the mpox vaccine for adolescents, the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine, the 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV20), and the pentavalent meningococcal vaccine (MenACWY-TT/MenB-FHbp).

A number of immunizations have been deleted from the 2024 schedule, including the pentavalent meningococcal vaccine MenABCWY because of a discontinuation in its distribution in the United States, the bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, the diphtheria and tetanus toxoids adsorbed vaccine, the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), and the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23).

The 2024 childhood and adolescent immunization schedule, also approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Nurse-Midwives, American Academy of Physician Associates, and National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, is published each year based on current recommendations that have been approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration.

In a press release, the AAP said the CDC decided to publish the recommendations early to ensure health providers are able to administer immunizations and that they are covered by insurance. They also referenced CDC reports that found vaccination rates for kindergarteners have not bounced back since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and vaccine exemptions for the 2022-2023 school year were at an “all-time high.”

RSV

New to the schedule are the recently approved RSV monoclonal antibody nirsevimab for infants and the RSV vaccine RSVpreF for pregnant people. According to the CDC’s combined immunization schedule for 2024, the timing of the infant RSV immunization is heavily dependent upon when and whether a RSV vaccine was administered during pregnancy. The RSV vaccine should be routinely given between 32 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation between September and January in most of the United States with the caveat that either the maternal vaccine or the infant immunization is recommended.

Infants born between October and March in most of the United States are eligible for the RSV immunization within 14 days of birth if the pregnant parent did not receive an RSV vaccine during pregnancy, or if the parent received the vaccine in the 14 days prior to birth. For infants born between April and September RSV immunization is recommended prior to the start of RSV season.

The immunization is also recommended for infants who were hospitalized for conditions such as prematurity after birth between October and March, infants aged 8-19 months who are undergoing medical support related to prematurity, infants aged 8-19 months who are severely immunocompromised, and infants aged 9-19 months who are American Indian or Alaska Native, and infants undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

Mpox

Another new addition to the schedule is mpox, which is recommended for adolescents 18 years or older who are at risk for mpox infection, including gay, bisexual, nonbinary, transgender, or other individuals who have developed a sexually transmitted disease within the last 6 months, had more than one sexual partner, or engaged in sex in a commercial sex venue or public space with confirmed mpox transmission.

Currently, mpox vaccination during pregnancy is not recommended due to a lack of safety data on the vaccine during pregnancy; however, the CDC noted pregnant persons who have been exposed to any of the risk factors above may receive the vaccine.

COVID, influenza, pneumococcal vaccines

The COVID-19 vaccine recommendations were updated to reflect the 2023-2023 formulation of the vaccine. Unvaccinated children between 6 months and 4 years of age will now receive the 2023-2024 formula mRNA vaccines, which includes the two-dose Moderna vaccine and three-dose Pfizer vaccine for use in that age group. Children with a previous history of COVID-19 vaccination are eligible to receive an age-appropriate COVID-19 vaccine from the 2023-2024 formulation, and children between 5-11 years old and 12-18 years old can receive a single dose of an mRNA vaccine regardless of vaccine history; unvaccinated children 12-18 years old are also eligible to receive the two-dose Novavax vaccine.

For influenza, the schedule refers to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommendations released in August, with a note indicating that individuals with an egg allergy can receive another vaccine recommended for their age group without concerns for safety.

The pneumococcal vaccine recommendations have removed PCV13 completely, with updates on the PCV15, PCV20, and PPSV23 in sections on routine vaccination, catch-up vaccination, and special situations. The poliovirus section has also seen its catch-up section revised with a recommendation to complete a vaccination series in adolescents 18 years old known or suspected to have an incomplete series, and to count trivalent oral poliovirus vaccines and OPV administered before April 2016 toward U.S. vaccination requirements.

‘Timely and necessary’ changes

Michael Pichichero, MD, director of the Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital Research Institute, said in an interview that the committee that developed the immunization schedule was thorough in its recommendations for children and adolescents.

“The additions are timely and necessary as the landscape of vaccines for children changes,” he said.

Bonnie M. Word, MD, director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic, said that the immunization schedule “sets the standard and provides clarification and uniformity for administration of all recommended vaccines for U.S. children.”

The U.S. immunization program “is one of the best success stories in medicine,” Dr. Wood said. She noted it is important for providers to become familiar with these vaccines and their indications “to provide advice and be able to respond to questions of parents and/or patients.

“Often patients spend more time with office staff than the physician. It is helpful to make sure everyone in the office understands the importance of and the rationale for immunizing, so families hear consistent messaging,” she said.

Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Word reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

CDC says child vaccination exemptions hit all-time high

– the highest exemption rate ever reported in the United States.

Of the 3% of children who got exemptions, 0.2% were for medical reasons and 2.8% for nonmedical reasons, the CDC report said. The overall exemption rate was 2.6% for the previous school year.

Though more children received exemptions, the overall national vaccination rate remained steady at 93% for children entering kindergarten for the 2022-2023 school year. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall rate was 95%, the CDC said.

“The bad news is that it’s gone down since the pandemic and still hasn’t rebounded,” Sean O’Leary, MD, a University of Colorado pediatric infectious diseases specialist, told The Associated Press. “The good news is that the vast majority of parents are still vaccinating their kids according to the recommended schedule.”

The CDC report did not offer a specific reason for higher vaccine exemptions. But it did note that the increase could be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID vaccine hesitancy.

“There is a rising distrust in the health care system,” Amna Husain, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in North Carolina and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics, told NBC News. Vaccine exemptions “have unfortunately trended upward with it.”

Exemption rates varied across the nation. The CDC said 40 states reported a rise in exemptions and that the exemption rate went over 5% in 10 states: Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin. Idaho had the highest exemption rate in 2022 with 12%.

While requirements vary from state to state, most states require students entering kindergarten to receive four vaccines: MMR, DTaP, polio, and chickenpox.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

– the highest exemption rate ever reported in the United States.

Of the 3% of children who got exemptions, 0.2% were for medical reasons and 2.8% for nonmedical reasons, the CDC report said. The overall exemption rate was 2.6% for the previous school year.

Though more children received exemptions, the overall national vaccination rate remained steady at 93% for children entering kindergarten for the 2022-2023 school year. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall rate was 95%, the CDC said.

“The bad news is that it’s gone down since the pandemic and still hasn’t rebounded,” Sean O’Leary, MD, a University of Colorado pediatric infectious diseases specialist, told The Associated Press. “The good news is that the vast majority of parents are still vaccinating their kids according to the recommended schedule.”

The CDC report did not offer a specific reason for higher vaccine exemptions. But it did note that the increase could be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID vaccine hesitancy.

“There is a rising distrust in the health care system,” Amna Husain, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in North Carolina and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics, told NBC News. Vaccine exemptions “have unfortunately trended upward with it.”

Exemption rates varied across the nation. The CDC said 40 states reported a rise in exemptions and that the exemption rate went over 5% in 10 states: Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin. Idaho had the highest exemption rate in 2022 with 12%.

While requirements vary from state to state, most states require students entering kindergarten to receive four vaccines: MMR, DTaP, polio, and chickenpox.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

– the highest exemption rate ever reported in the United States.

Of the 3% of children who got exemptions, 0.2% were for medical reasons and 2.8% for nonmedical reasons, the CDC report said. The overall exemption rate was 2.6% for the previous school year.

Though more children received exemptions, the overall national vaccination rate remained steady at 93% for children entering kindergarten for the 2022-2023 school year. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall rate was 95%, the CDC said.

“The bad news is that it’s gone down since the pandemic and still hasn’t rebounded,” Sean O’Leary, MD, a University of Colorado pediatric infectious diseases specialist, told The Associated Press. “The good news is that the vast majority of parents are still vaccinating their kids according to the recommended schedule.”

The CDC report did not offer a specific reason for higher vaccine exemptions. But it did note that the increase could be caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID vaccine hesitancy.

“There is a rising distrust in the health care system,” Amna Husain, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in North Carolina and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics, told NBC News. Vaccine exemptions “have unfortunately trended upward with it.”

Exemption rates varied across the nation. The CDC said 40 states reported a rise in exemptions and that the exemption rate went over 5% in 10 states: Alaska, Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho, Michigan, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah, and Wisconsin. Idaho had the highest exemption rate in 2022 with 12%.

While requirements vary from state to state, most states require students entering kindergarten to receive four vaccines: MMR, DTaP, polio, and chickenpox.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Preventing RSV in children and adults: A vaccine update

In the past year, there has been significant progress in the availability of interventions to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its complications. Four products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). They include 2 vaccines for adults ages 60 years and older, a monoclonal antibody for infants and high-risk children, and a maternal vaccine to prevent RSV infection in newborns.

RSV in adults

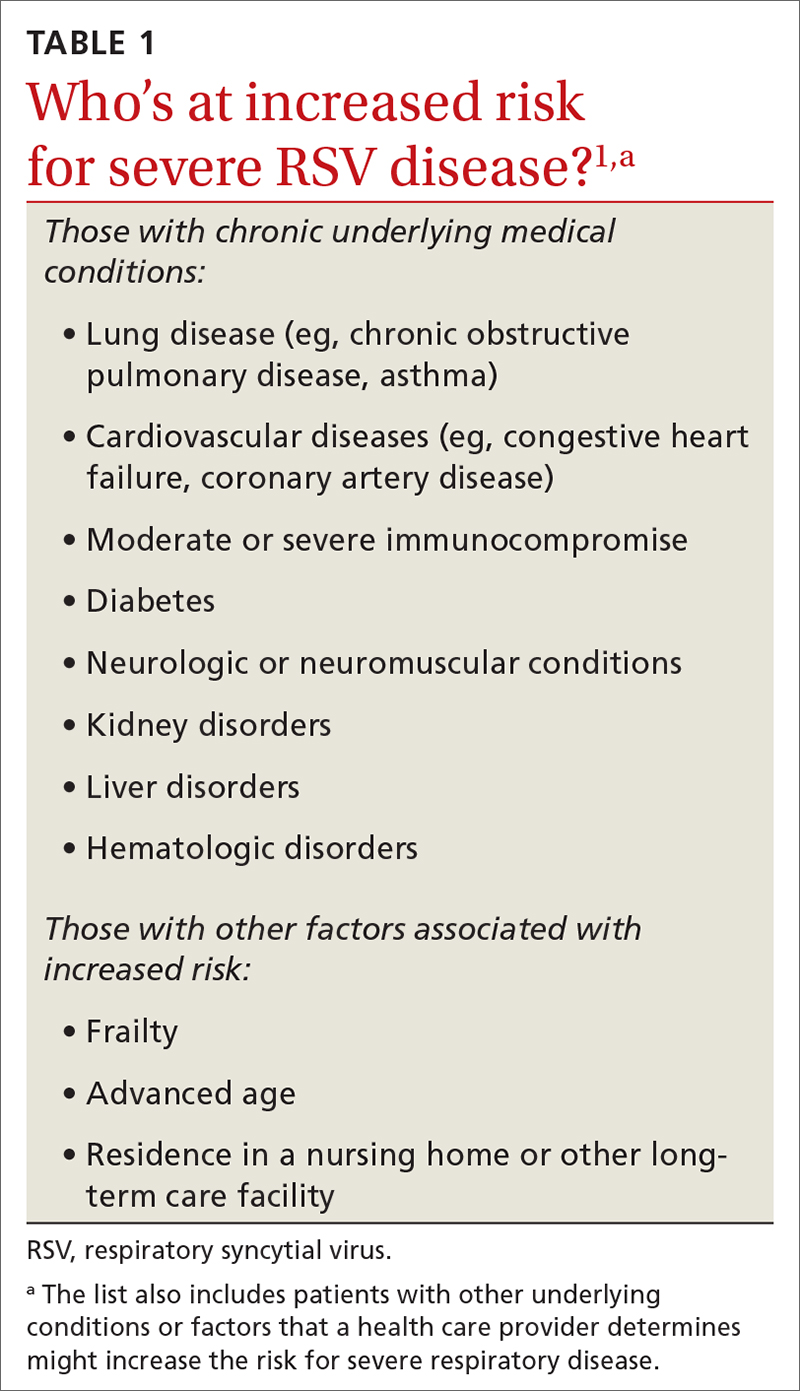

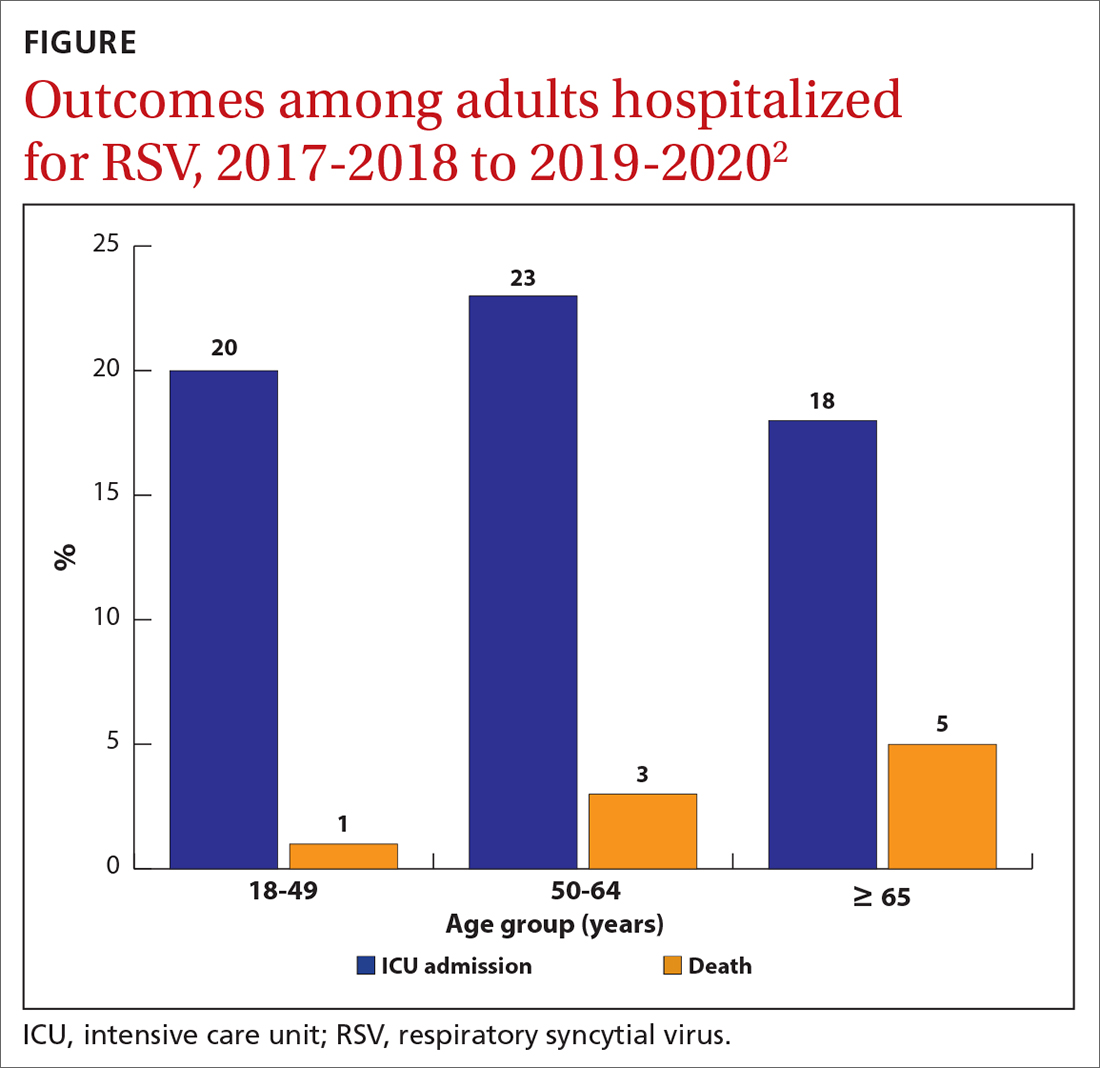

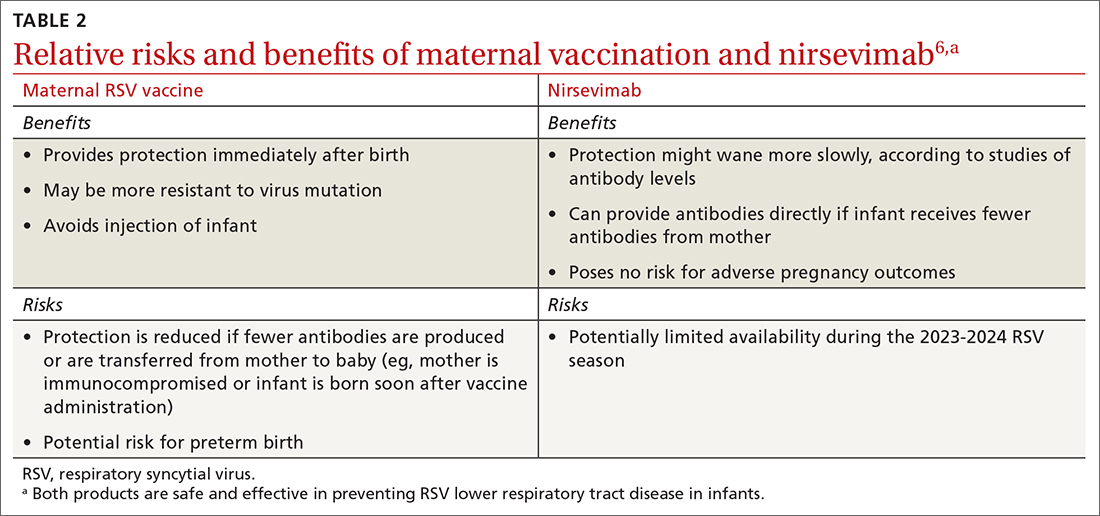

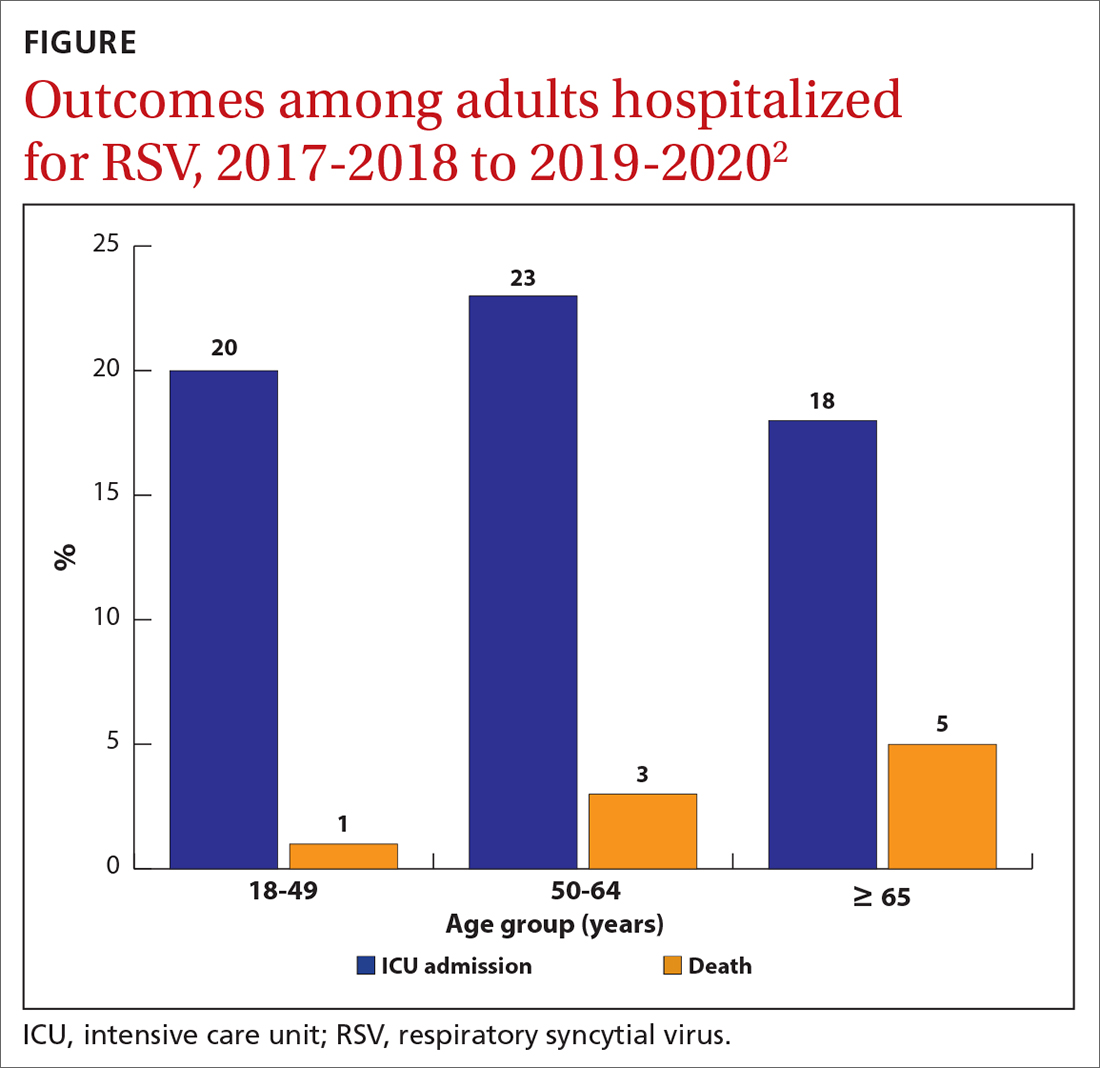

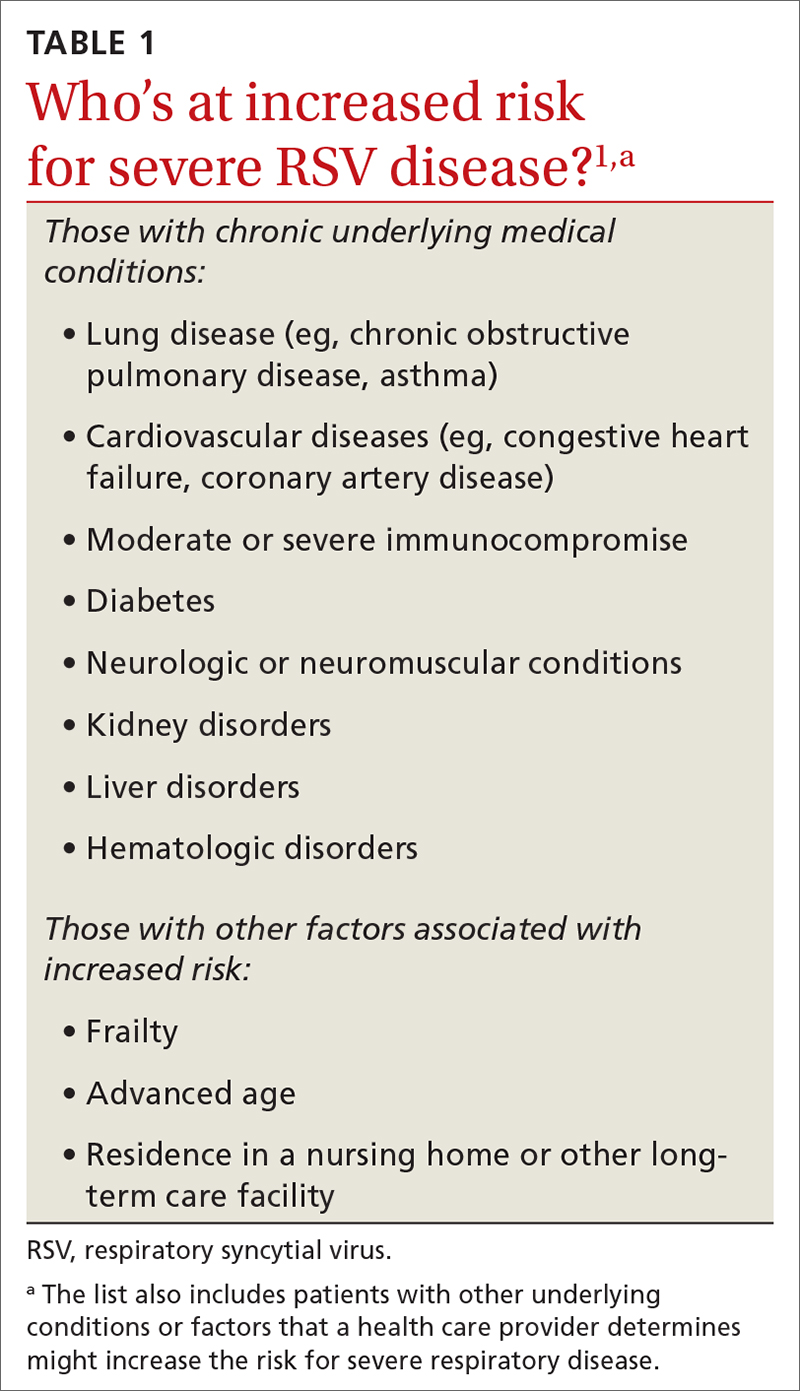

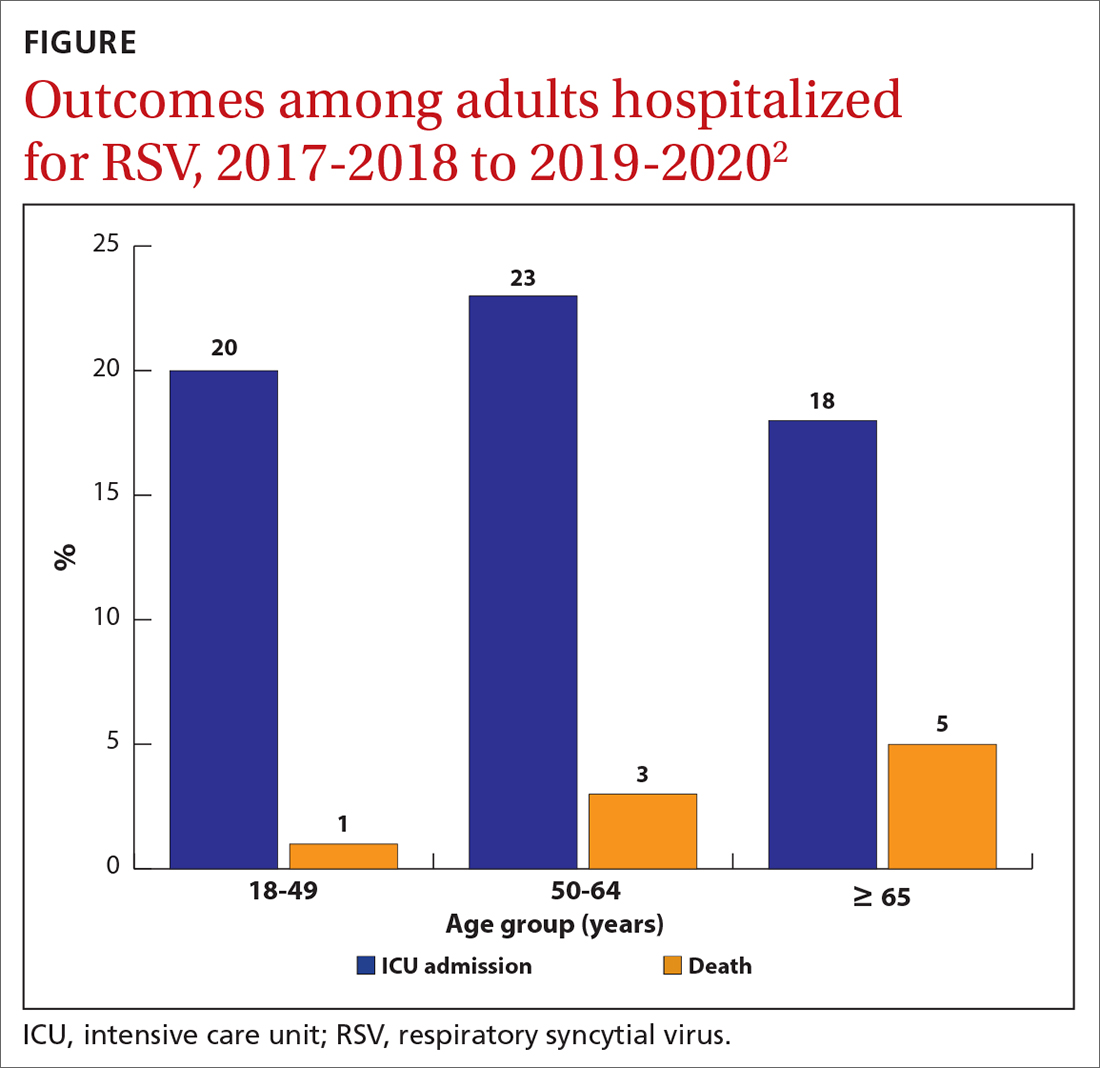

While there is some uncertainty about the total burden of RSV in adults in the United States, the CDC estimates that each year it causes 0.9 to 1.4 million medical encounters, 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations, and 6000 to 10,000 deaths.1 The rate of RSV-caused hospitalization increases with age,2 and the infection is more severe in those with certain chronic medical conditions (TABLE 11). The FIGURE2 demonstrates the outcomes of adults who are hospitalized for RSV. Adults older than 65 years have a 5% mortality rate if hospitalized for RSV infection.2

Vaccine options for adults

Two vaccines were recently approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) in those ages 60 years and older: RSVPreF3 (Arexvy, GSK), which is an adjuvanted recombinant F protein vaccine, and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer), which is a recombinant stabilized vaccine. Both require only a single dose (0.5 mL IM), which provides protection for 2 years.

The efficacy of the GSK vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed, RSV-associated LRTD was 82.6% during the first RSV season and 56.1% during the second season. The efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed LRTD was 88.9% during the first RSV season and 78.6% during the second season.1 However, the trials leading to licensure of both vaccines were underpowered to show efficacy in the oldest adults and those who are frail or to show efficacy against RSV-caused hospitalization.

Safety of the adult RSV vaccines. The safety trials for both vaccines had a total of 38,177 participants. There were a total of 6 neurologic inflammatory conditions that developed within 42 days of vaccination, including 2 cases of suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 2 cases of possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case each of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and undifferentiated motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy.1 That is a rate of 1 case of a neurologic inflammatory condition for every 6363 people vaccinated. Since the trials were not powered to determine whether the small number of cases were due to chance, postmarketing surveillance will be needed to clarify the true risk for GBS or other neurologic inflammatory events from RSV vaccination.

The lack of efficacy data for the most vulnerable older adults and the lingering questions about safety prompted the ACIP to recommend that adults ages 60 years and older may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine, using shared clinical decision-making—which is different from a routine or risk-based vaccine recommendation. For RSV vaccination, the decision to vaccinate should be based on a risk/benefit discussion between the clinician and the patient. Those most likely to benefit from the vaccine are listed in TABLE 1.1

While data on coadministration of RSV vaccines with other adult vaccines are sparse, the ACIP states that co-administration with other vaccines is acceptable.1 It is not known yet whether boosters will be needed after 2 years.

Continue to: RSV in infants and children

RSV in infants and children

RSV is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.3 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.3

There are racial disparities in RSV severity: Intensive care unit admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.3

The months of highest RSV transmission in most locations are December through February, but this can vary. For practical purposes, RSV season runs from October through March.

Prevention in infants and children

The monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is now available for use in infants younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season and children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season. Details regarding the use of this product were described in a recent Practice Alert Brief.4

Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrated 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended LRTD, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.5

Continue to: RSV vaccine in pregnancy

RSV vaccine in pregnancy

In August, the FDA approved Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine for use during pregnancy—as a single dose given at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation—for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants in the first 6 months of life. In the clinical trials, the vaccine was given at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there was a statistically nonsignificant increase in preterm births in the RSVpreF group compared to the placebo group.6 While there were insufficient data to prove or rule out a causal relationship, the FDA advisory committee was more comfortable approving the vaccine for use only later in pregnancy, to avoid the possibility of very early preterm births after vaccination. The ACIP agreed.

From time of maternal vaccination, at least 14 days are needed to develop and transfer maternal antibodies across the placenta to protect the infant. Therefore, infants born less than 14 days after maternal vaccination should be considered unprotected.

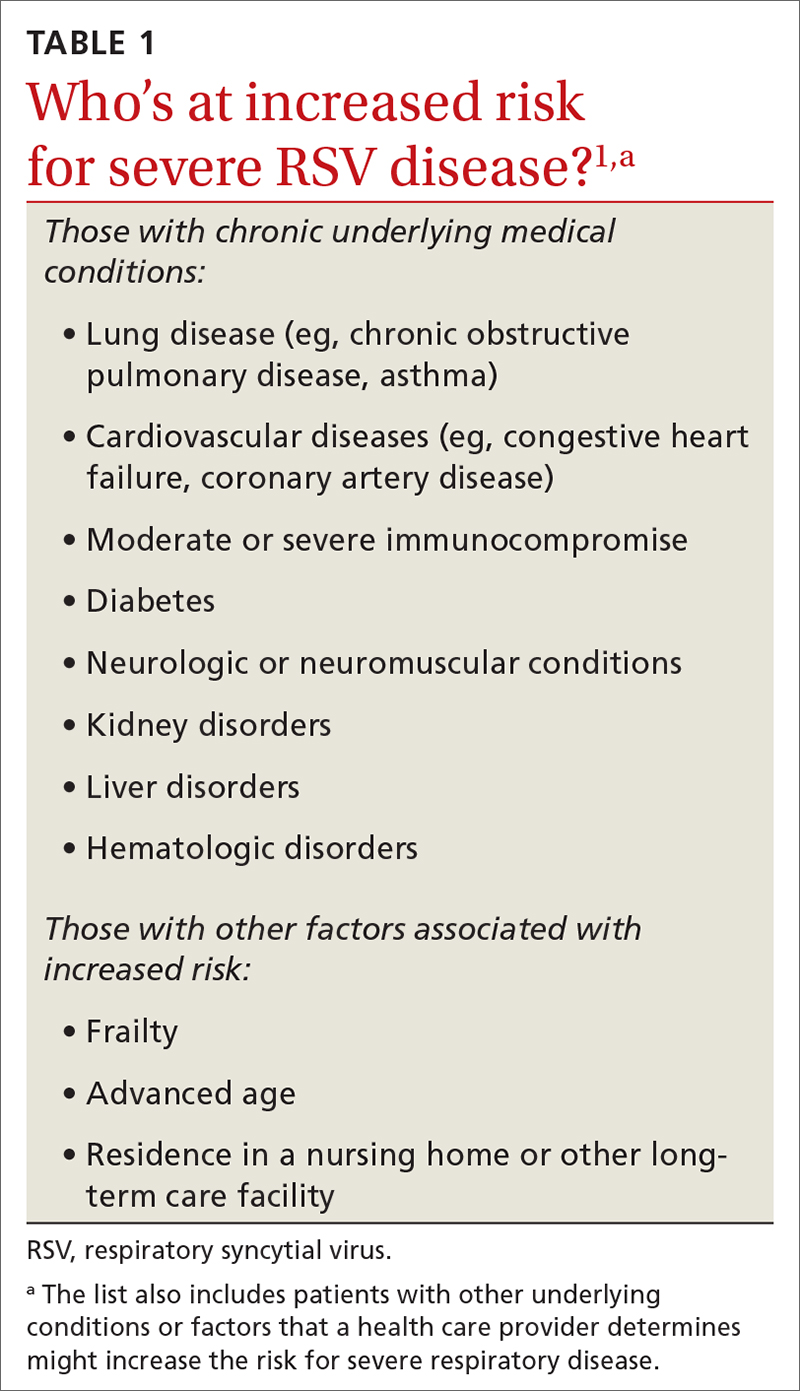

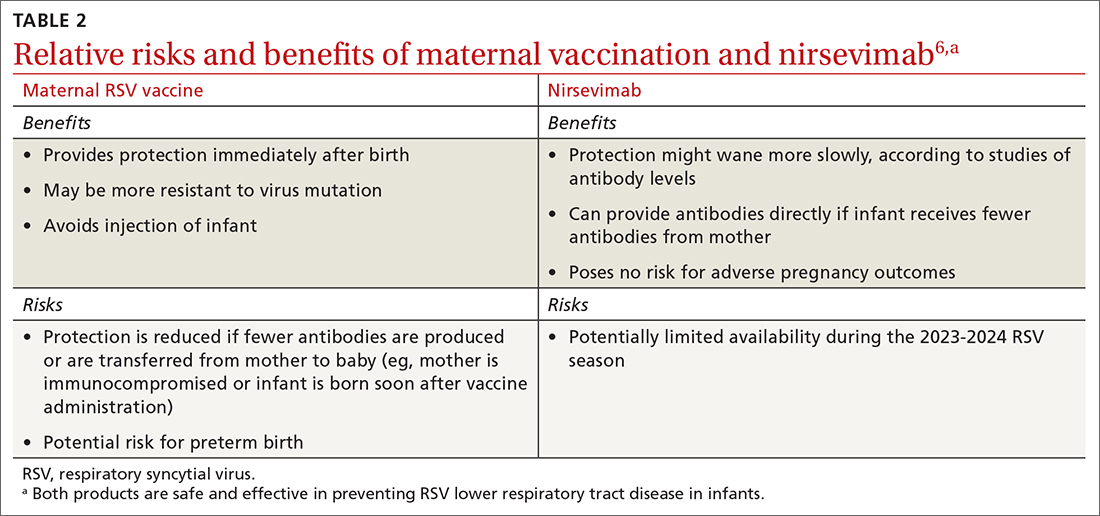

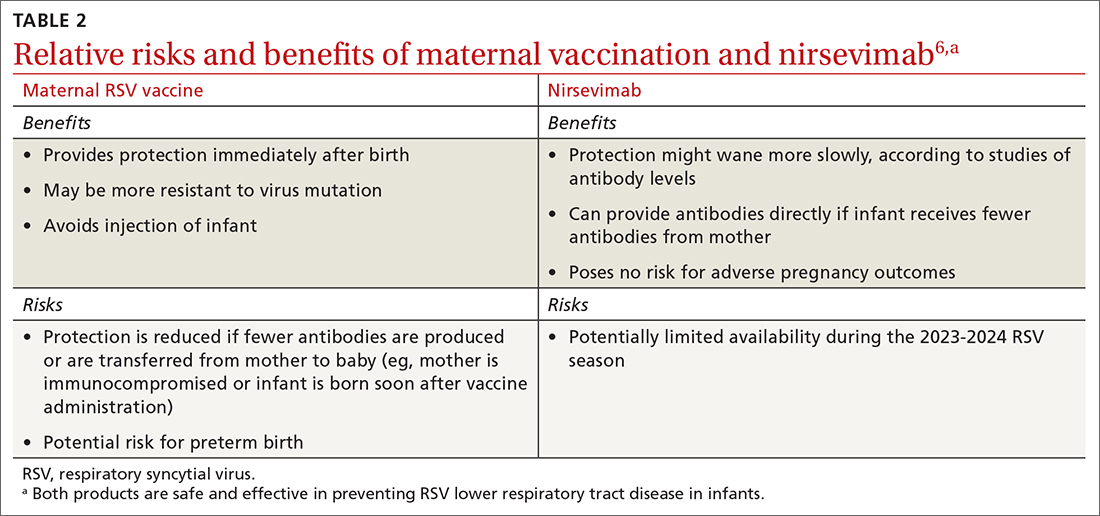

Both maternal vaccination with RSVpreF and infant injection with nirsevimab are now options to protect newborns and infants from RSV. However, use of both products is not needed, since combined they do not offer significant added protection compared to either product alone (exceptions to be discussed shortly).6 When the estimated due date will occur in the RSV season, maternity clinicians should provide information on both products and assist the mother in deciding whether to be vaccinated or rely on administration of nirsevimab to the infant after birth. The benefits and risks of these 2 options are listed in TABLE 2.6

There are some rare situations in which use of both products is recommended, and they include6:

- When the baby is born less than 14 days from the time of maternal vaccination

- When the mother has a condition that could produce an inadequate response to the vaccine

- When the infant has had cardiopulmonary bypass, which would lead to loss of maternal antibodies

- When the infant has severe disease placing them at increased risk for severe RSV.

Conclusion

All of these new RSV preventive products should soon be widely available and covered with no out-of-pocket expense by commercial and government payers. The exception might be nirsevimab—because of the time needed to produce it, it might not be universally available in the 2023-2024 season.

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:793-801.

2. Melgar M. Evidence to recommendation framework. RSV in adults. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/RSV-Adults-04-Melgar-508.pdf

3. Jones JM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Prill MM, et al. Use of nirsevimab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:90-925.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option. J Fam Pract. 2023;72. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0663

5. Jones J. Evidence to recommendation framework: nirsevimab updates. Presented to the ACIP on August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/131586

6. Jones J. Clinical considerations for maternal RSVPreF vaccine and nirsevimab. Presented to the ACIP on September 25, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2023. www2.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/ciinc/archives/23/09/ciiw_RSV2/CIIW%20RSV%20maternal%20vaccine%20mAb%209.27.23.pdf

In the past year, there has been significant progress in the availability of interventions to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its complications. Four products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). They include 2 vaccines for adults ages 60 years and older, a monoclonal antibody for infants and high-risk children, and a maternal vaccine to prevent RSV infection in newborns.

RSV in adults

While there is some uncertainty about the total burden of RSV in adults in the United States, the CDC estimates that each year it causes 0.9 to 1.4 million medical encounters, 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations, and 6000 to 10,000 deaths.1 The rate of RSV-caused hospitalization increases with age,2 and the infection is more severe in those with certain chronic medical conditions (TABLE 11). The FIGURE2 demonstrates the outcomes of adults who are hospitalized for RSV. Adults older than 65 years have a 5% mortality rate if hospitalized for RSV infection.2

Vaccine options for adults

Two vaccines were recently approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) in those ages 60 years and older: RSVPreF3 (Arexvy, GSK), which is an adjuvanted recombinant F protein vaccine, and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer), which is a recombinant stabilized vaccine. Both require only a single dose (0.5 mL IM), which provides protection for 2 years.

The efficacy of the GSK vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed, RSV-associated LRTD was 82.6% during the first RSV season and 56.1% during the second season. The efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed LRTD was 88.9% during the first RSV season and 78.6% during the second season.1 However, the trials leading to licensure of both vaccines were underpowered to show efficacy in the oldest adults and those who are frail or to show efficacy against RSV-caused hospitalization.

Safety of the adult RSV vaccines. The safety trials for both vaccines had a total of 38,177 participants. There were a total of 6 neurologic inflammatory conditions that developed within 42 days of vaccination, including 2 cases of suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 2 cases of possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case each of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and undifferentiated motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy.1 That is a rate of 1 case of a neurologic inflammatory condition for every 6363 people vaccinated. Since the trials were not powered to determine whether the small number of cases were due to chance, postmarketing surveillance will be needed to clarify the true risk for GBS or other neurologic inflammatory events from RSV vaccination.

The lack of efficacy data for the most vulnerable older adults and the lingering questions about safety prompted the ACIP to recommend that adults ages 60 years and older may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine, using shared clinical decision-making—which is different from a routine or risk-based vaccine recommendation. For RSV vaccination, the decision to vaccinate should be based on a risk/benefit discussion between the clinician and the patient. Those most likely to benefit from the vaccine are listed in TABLE 1.1

While data on coadministration of RSV vaccines with other adult vaccines are sparse, the ACIP states that co-administration with other vaccines is acceptable.1 It is not known yet whether boosters will be needed after 2 years.

Continue to: RSV in infants and children

RSV in infants and children

RSV is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.3 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.3

There are racial disparities in RSV severity: Intensive care unit admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.3

The months of highest RSV transmission in most locations are December through February, but this can vary. For practical purposes, RSV season runs from October through March.

Prevention in infants and children

The monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is now available for use in infants younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season and children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season. Details regarding the use of this product were described in a recent Practice Alert Brief.4

Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrated 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended LRTD, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.5

Continue to: RSV vaccine in pregnancy

RSV vaccine in pregnancy

In August, the FDA approved Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine for use during pregnancy—as a single dose given at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation—for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants in the first 6 months of life. In the clinical trials, the vaccine was given at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there was a statistically nonsignificant increase in preterm births in the RSVpreF group compared to the placebo group.6 While there were insufficient data to prove or rule out a causal relationship, the FDA advisory committee was more comfortable approving the vaccine for use only later in pregnancy, to avoid the possibility of very early preterm births after vaccination. The ACIP agreed.

From time of maternal vaccination, at least 14 days are needed to develop and transfer maternal antibodies across the placenta to protect the infant. Therefore, infants born less than 14 days after maternal vaccination should be considered unprotected.

Both maternal vaccination with RSVpreF and infant injection with nirsevimab are now options to protect newborns and infants from RSV. However, use of both products is not needed, since combined they do not offer significant added protection compared to either product alone (exceptions to be discussed shortly).6 When the estimated due date will occur in the RSV season, maternity clinicians should provide information on both products and assist the mother in deciding whether to be vaccinated or rely on administration of nirsevimab to the infant after birth. The benefits and risks of these 2 options are listed in TABLE 2.6

There are some rare situations in which use of both products is recommended, and they include6:

- When the baby is born less than 14 days from the time of maternal vaccination

- When the mother has a condition that could produce an inadequate response to the vaccine

- When the infant has had cardiopulmonary bypass, which would lead to loss of maternal antibodies

- When the infant has severe disease placing them at increased risk for severe RSV.

Conclusion

All of these new RSV preventive products should soon be widely available and covered with no out-of-pocket expense by commercial and government payers. The exception might be nirsevimab—because of the time needed to produce it, it might not be universally available in the 2023-2024 season.

In the past year, there has been significant progress in the availability of interventions to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its complications. Four products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). They include 2 vaccines for adults ages 60 years and older, a monoclonal antibody for infants and high-risk children, and a maternal vaccine to prevent RSV infection in newborns.

RSV in adults

While there is some uncertainty about the total burden of RSV in adults in the United States, the CDC estimates that each year it causes 0.9 to 1.4 million medical encounters, 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations, and 6000 to 10,000 deaths.1 The rate of RSV-caused hospitalization increases with age,2 and the infection is more severe in those with certain chronic medical conditions (TABLE 11). The FIGURE2 demonstrates the outcomes of adults who are hospitalized for RSV. Adults older than 65 years have a 5% mortality rate if hospitalized for RSV infection.2

Vaccine options for adults

Two vaccines were recently approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) in those ages 60 years and older: RSVPreF3 (Arexvy, GSK), which is an adjuvanted recombinant F protein vaccine, and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer), which is a recombinant stabilized vaccine. Both require only a single dose (0.5 mL IM), which provides protection for 2 years.

The efficacy of the GSK vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed, RSV-associated LRTD was 82.6% during the first RSV season and 56.1% during the second season. The efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed LRTD was 88.9% during the first RSV season and 78.6% during the second season.1 However, the trials leading to licensure of both vaccines were underpowered to show efficacy in the oldest adults and those who are frail or to show efficacy against RSV-caused hospitalization.

Safety of the adult RSV vaccines. The safety trials for both vaccines had a total of 38,177 participants. There were a total of 6 neurologic inflammatory conditions that developed within 42 days of vaccination, including 2 cases of suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 2 cases of possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case each of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and undifferentiated motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy.1 That is a rate of 1 case of a neurologic inflammatory condition for every 6363 people vaccinated. Since the trials were not powered to determine whether the small number of cases were due to chance, postmarketing surveillance will be needed to clarify the true risk for GBS or other neurologic inflammatory events from RSV vaccination.

The lack of efficacy data for the most vulnerable older adults and the lingering questions about safety prompted the ACIP to recommend that adults ages 60 years and older may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine, using shared clinical decision-making—which is different from a routine or risk-based vaccine recommendation. For RSV vaccination, the decision to vaccinate should be based on a risk/benefit discussion between the clinician and the patient. Those most likely to benefit from the vaccine are listed in TABLE 1.1

While data on coadministration of RSV vaccines with other adult vaccines are sparse, the ACIP states that co-administration with other vaccines is acceptable.1 It is not known yet whether boosters will be needed after 2 years.

Continue to: RSV in infants and children

RSV in infants and children

RSV is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.3 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.3

There are racial disparities in RSV severity: Intensive care unit admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.3

The months of highest RSV transmission in most locations are December through February, but this can vary. For practical purposes, RSV season runs from October through March.

Prevention in infants and children

The monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is now available for use in infants younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season and children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season. Details regarding the use of this product were described in a recent Practice Alert Brief.4

Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrated 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended LRTD, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.5

Continue to: RSV vaccine in pregnancy

RSV vaccine in pregnancy

In August, the FDA approved Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine for use during pregnancy—as a single dose given at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation—for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants in the first 6 months of life. In the clinical trials, the vaccine was given at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there was a statistically nonsignificant increase in preterm births in the RSVpreF group compared to the placebo group.6 While there were insufficient data to prove or rule out a causal relationship, the FDA advisory committee was more comfortable approving the vaccine for use only later in pregnancy, to avoid the possibility of very early preterm births after vaccination. The ACIP agreed.

From time of maternal vaccination, at least 14 days are needed to develop and transfer maternal antibodies across the placenta to protect the infant. Therefore, infants born less than 14 days after maternal vaccination should be considered unprotected.

Both maternal vaccination with RSVpreF and infant injection with nirsevimab are now options to protect newborns and infants from RSV. However, use of both products is not needed, since combined they do not offer significant added protection compared to either product alone (exceptions to be discussed shortly).6 When the estimated due date will occur in the RSV season, maternity clinicians should provide information on both products and assist the mother in deciding whether to be vaccinated or rely on administration of nirsevimab to the infant after birth. The benefits and risks of these 2 options are listed in TABLE 2.6

There are some rare situations in which use of both products is recommended, and they include6:

- When the baby is born less than 14 days from the time of maternal vaccination

- When the mother has a condition that could produce an inadequate response to the vaccine

- When the infant has had cardiopulmonary bypass, which would lead to loss of maternal antibodies

- When the infant has severe disease placing them at increased risk for severe RSV.

Conclusion

All of these new RSV preventive products should soon be widely available and covered with no out-of-pocket expense by commercial and government payers. The exception might be nirsevimab—because of the time needed to produce it, it might not be universally available in the 2023-2024 season.

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:793-801.

2. Melgar M. Evidence to recommendation framework. RSV in adults. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/RSV-Adults-04-Melgar-508.pdf

3. Jones JM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Prill MM, et al. Use of nirsevimab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:90-925.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option. J Fam Pract. 2023;72. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0663

5. Jones J. Evidence to recommendation framework: nirsevimab updates. Presented to the ACIP on August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/131586

6. Jones J. Clinical considerations for maternal RSVPreF vaccine and nirsevimab. Presented to the ACIP on September 25, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2023. www2.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/ciinc/archives/23/09/ciiw_RSV2/CIIW%20RSV%20maternal%20vaccine%20mAb%209.27.23.pdf

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:793-801.

2. Melgar M. Evidence to recommendation framework. RSV in adults. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/RSV-Adults-04-Melgar-508.pdf

3. Jones JM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Prill MM, et al. Use of nirsevimab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:90-925.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option. J Fam Pract. 2023;72. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0663

5. Jones J. Evidence to recommendation framework: nirsevimab updates. Presented to the ACIP on August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/131586

6. Jones J. Clinical considerations for maternal RSVPreF vaccine and nirsevimab. Presented to the ACIP on September 25, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2023. www2.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/ciinc/archives/23/09/ciiw_RSV2/CIIW%20RSV%20maternal%20vaccine%20mAb%209.27.23.pdf

Keep COVID-19 vaccination on your patients’ radar

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently issued updated recommendations on the use of vaccines to protect against COVID-19.1 In addition, 3 new COVID-19 vaccine products have been approved for use in the United States since September. Before we discuss both of these items, it’s important to understand why we’re still talking about COVID-19 vaccines.

The impact of vaccination can’t be understated. Vaccines to protect against COVID-19 have been hugely successful in preventing mortality and morbidity from illness caused by SARS-CoV-2. It is estimated that in the first year alone, after vaccines became widely available, they saved more than 14 million lives globally.2 By the end of 2022, they had prevented 18.5 million hospitalizations and 3.2 million deaths in the United States.3 However, waning levels of vaccine-induced immunity and the continuous mutation of the virus have prompted the need for booster doses of vaccine and development of new vaccines.

Enter this year’s vaccines. The new products include updated (2023-2024 formula) COVID-19 mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, for use in those ages 6 months and older, and Novavax COVID-19 vaccine for use in those ages 12 years and older. All 3 provide protection against the currently circulating XBB variants, which by September 2023 accounted for > 99% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in the United States.1

Novavax is an option for those who are hesitant to use an mRNA-based vaccine, although the exact recommendations for its use are still pending. Of note, the previously approved bivalent vaccines and the previous Novavax monovalent vaccine are no longer approved for use in the United States.

Current recommendations. For those ages 5 years and older, the recommendation is for a single dose of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine regardless of previous vaccination history—except for those who were previously unvaccinated and choose Novavax. (Those individuals should receive 2 doses, 3 to 8 weeks apart.) For those ages 6 months through 4 years, the recommended number of doses varies by vaccine and previous vaccination history1; a table can be found at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7242e1.htm.

Those who are moderately to severely immunocompromised should receive a 3-dose series with one of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccines and may receive 1 or more additional updated doses.1 These recommendations are more nuanced, and a full description of them can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

Major changes in this year’s recommendations,4 compared to those previously made on the use of the bivalent vaccines, include:

- Eliminating complex recommendations for 5-year-olds, who are now included in the standard recommendation

- Reducing the number of COVID-19 vaccine products in use by standardizing the dose (25 mcg) for those ages 6 months to 11 years

- Choosing to monitor epidemiology and vaccine effectiveness data to determine whether an additional dose of this year’s vaccine will be needed for those ages 65 years and older, rather than making a recommendation now.

Who’s paying? Another change is how COVID-19 vaccines are paid for. The United States is moving from a system of federal procurement and distribution to the commercial marketplace. This may lead to some disruption and confusion.

All commercial health plans, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, must cover vaccines recommend by the ACIP with no out-of-pocket cost. The Vaccines for Children program provides free vaccine for uninsured and underinsured children up to age 19 years.

However, that leaves no payer for uninsured adults. In response, the CDC has announced the establishment of the Bridge Access Program, which is a private/government partnership to provide the vaccine to this age group. Details about where an adult can obtain a free COVID-19 vaccine through this program can be found by visiting www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/bridge/index.html or by calling 800-CDC-INFO.

A dynamic situation. COVID-19 vaccines and associated recommendations are likely to change with time, as we learn how best to formulate them to adjust to virus mutations and determine the optimal intervals to adjust and administer these vaccines. The result may (or may not) eventually resemble the approach recommended for influenza vaccines, which is annual assessment and adjustment of the targeted antigens, when needed, and annual universal vaccination.

1. Regan JJ, Moulia DL, Link-Guelles R, et al. Use of updated COVID-19 vaccines 2023-2024 formula for persons aged > 6 months: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, September 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:1140-1146. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7242e1

2. Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, et al. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1293-302. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

3. Fitzpatrick M, Moghadas S, Pandey A, et al. Two years of US COVID-19 vaccines have prevented millions of hospitalizations and deaths. The Commonwealth Fund; 2022. Published December 13, 2022. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/two-years-covid-vaccines-prevented-millions-deaths-hospitalizations https://doi.org/10.26099/whsf-fp90

4. Wallace M. Evidence to recommendations framework: 2023-2024 (monovalent, XBB containing) COVID-19 vaccine. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 12, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-09-12/11-COVID-Wallace-508.pdf

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently issued updated recommendations on the use of vaccines to protect against COVID-19.1 In addition, 3 new COVID-19 vaccine products have been approved for use in the United States since September. Before we discuss both of these items, it’s important to understand why we’re still talking about COVID-19 vaccines.

The impact of vaccination can’t be understated. Vaccines to protect against COVID-19 have been hugely successful in preventing mortality and morbidity from illness caused by SARS-CoV-2. It is estimated that in the first year alone, after vaccines became widely available, they saved more than 14 million lives globally.2 By the end of 2022, they had prevented 18.5 million hospitalizations and 3.2 million deaths in the United States.3 However, waning levels of vaccine-induced immunity and the continuous mutation of the virus have prompted the need for booster doses of vaccine and development of new vaccines.

Enter this year’s vaccines. The new products include updated (2023-2024 formula) COVID-19 mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, for use in those ages 6 months and older, and Novavax COVID-19 vaccine for use in those ages 12 years and older. All 3 provide protection against the currently circulating XBB variants, which by September 2023 accounted for > 99% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in the United States.1

Novavax is an option for those who are hesitant to use an mRNA-based vaccine, although the exact recommendations for its use are still pending. Of note, the previously approved bivalent vaccines and the previous Novavax monovalent vaccine are no longer approved for use in the United States.

Current recommendations. For those ages 5 years and older, the recommendation is for a single dose of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine regardless of previous vaccination history—except for those who were previously unvaccinated and choose Novavax. (Those individuals should receive 2 doses, 3 to 8 weeks apart.) For those ages 6 months through 4 years, the recommended number of doses varies by vaccine and previous vaccination history1; a table can be found at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7242e1.htm.

Those who are moderately to severely immunocompromised should receive a 3-dose series with one of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccines and may receive 1 or more additional updated doses.1 These recommendations are more nuanced, and a full description of them can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

Major changes in this year’s recommendations,4 compared to those previously made on the use of the bivalent vaccines, include:

- Eliminating complex recommendations for 5-year-olds, who are now included in the standard recommendation

- Reducing the number of COVID-19 vaccine products in use by standardizing the dose (25 mcg) for those ages 6 months to 11 years

- Choosing to monitor epidemiology and vaccine effectiveness data to determine whether an additional dose of this year’s vaccine will be needed for those ages 65 years and older, rather than making a recommendation now.

Who’s paying? Another change is how COVID-19 vaccines are paid for. The United States is moving from a system of federal procurement and distribution to the commercial marketplace. This may lead to some disruption and confusion.

All commercial health plans, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, must cover vaccines recommend by the ACIP with no out-of-pocket cost. The Vaccines for Children program provides free vaccine for uninsured and underinsured children up to age 19 years.

However, that leaves no payer for uninsured adults. In response, the CDC has announced the establishment of the Bridge Access Program, which is a private/government partnership to provide the vaccine to this age group. Details about where an adult can obtain a free COVID-19 vaccine through this program can be found by visiting www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/bridge/index.html or by calling 800-CDC-INFO.

A dynamic situation. COVID-19 vaccines and associated recommendations are likely to change with time, as we learn how best to formulate them to adjust to virus mutations and determine the optimal intervals to adjust and administer these vaccines. The result may (or may not) eventually resemble the approach recommended for influenza vaccines, which is annual assessment and adjustment of the targeted antigens, when needed, and annual universal vaccination.