User login

Syncope during pregnancy increases risk for poor outcomes

a retrospective population-based cohort study finds. Risks appeared highest with first-trimester syncope.

“There are very limited data on the frequency of fainting during pregnancy,” Padma Kaul, Ph.D., senior study author and professor of medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in a statement. “In our study, fainting during pregnancy occurred in about 1%, or 10 per 1,000 pregnancies, but appears to be increasing by 5% each year.”

“Fainting during pregnancy has previously been thought to follow a relatively benign course,” Dr. Kaul said. “The findings of our study suggest that timing of fainting during pregnancy may be important. When the faint happens early during pregnancy or multiple times during pregnancy, it may be associated with both short- and long-term health issues for the baby and the mother.”

First authors Safia Chatur, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.) and Sunjidatul Islam, MBBS, of the Canadian Vigour Centre, Edmonton, Alta., and associates analyzed 481,930 pregnancies occurring during 2005-2014 in the province.

Study results, reported in the Journal of the American Heart Association, showed that syncope occurred in almost 1% of pregnancies (9.7 episodes per 1,000 pregnancies) overall. Incidence increased by 5% per year during the study period.

Syncope episodes were distributed across the first trimester (32%), second trimester (44%), and third trimester (24%). Eight percent of pregnancies had more than one episode.

Compared with unaffected peers, women who experienced syncope were younger (age younger than 25 years, 35% vs. 21%; P less than .001) and more often primiparous (52% vs. 42%; P less than .001).

The rate of preterm birth was 18%, 16%, and 14% in pregnancies with an initial syncope episode during the first, second, and third trimester, respectively, compared with 15% in pregnancies without syncope (P less than .01 across groups).

With a median follow-up of about 5 years, compared with peers of syncope-free pregnancies, children of pregnancies complicated by syncope had a higher incidence of congenital anomalies (3.1% vs. 2.6%; P = .023). Incidence was highest in pregnancies with multiple episodes of syncope (5% vs. 3%; P less than .01).

In adjusted analyses that accounted for multiple pregnancies in individual women, relative to counterparts with no syncope during pregnancy, women who experienced syncope during the first trimester had higher odds of giving birth preterm (odds ratio, 1.3; P = .001) and of having an infant small for gestational age (OR, 1.2; P = .04) or with congenital anomalies (OR, 1.4; P = .036). Women with multiple syncope episodes versus none were twice as likely to have offspring with congenital anomalies (OR, 2.0; P = .003).

Relative to peers who did not experience syncope in pregnancy, women who did had higher incidences of cardiac arrhythmias (0.8% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) and syncope episodes (1.4% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) in the first year after delivery.

“Our data suggest that syncope during pregnancy may not be a benign occurrence,” Dr. Chatur and associates said. “More detailed clinical data are needed to identify potential causes for the observed increase in syncope during pregnancy in our study.“Whether women who experience syncope during pregnancy may benefit from closer monitoring during the obstetric and postpartum periods requires further study,” they concluded.

The investigators disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. This study was funded by a grant from the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada.

SOURCE: Chatur S et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011608.

a retrospective population-based cohort study finds. Risks appeared highest with first-trimester syncope.

“There are very limited data on the frequency of fainting during pregnancy,” Padma Kaul, Ph.D., senior study author and professor of medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in a statement. “In our study, fainting during pregnancy occurred in about 1%, or 10 per 1,000 pregnancies, but appears to be increasing by 5% each year.”

“Fainting during pregnancy has previously been thought to follow a relatively benign course,” Dr. Kaul said. “The findings of our study suggest that timing of fainting during pregnancy may be important. When the faint happens early during pregnancy or multiple times during pregnancy, it may be associated with both short- and long-term health issues for the baby and the mother.”

First authors Safia Chatur, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.) and Sunjidatul Islam, MBBS, of the Canadian Vigour Centre, Edmonton, Alta., and associates analyzed 481,930 pregnancies occurring during 2005-2014 in the province.

Study results, reported in the Journal of the American Heart Association, showed that syncope occurred in almost 1% of pregnancies (9.7 episodes per 1,000 pregnancies) overall. Incidence increased by 5% per year during the study period.

Syncope episodes were distributed across the first trimester (32%), second trimester (44%), and third trimester (24%). Eight percent of pregnancies had more than one episode.

Compared with unaffected peers, women who experienced syncope were younger (age younger than 25 years, 35% vs. 21%; P less than .001) and more often primiparous (52% vs. 42%; P less than .001).

The rate of preterm birth was 18%, 16%, and 14% in pregnancies with an initial syncope episode during the first, second, and third trimester, respectively, compared with 15% in pregnancies without syncope (P less than .01 across groups).

With a median follow-up of about 5 years, compared with peers of syncope-free pregnancies, children of pregnancies complicated by syncope had a higher incidence of congenital anomalies (3.1% vs. 2.6%; P = .023). Incidence was highest in pregnancies with multiple episodes of syncope (5% vs. 3%; P less than .01).

In adjusted analyses that accounted for multiple pregnancies in individual women, relative to counterparts with no syncope during pregnancy, women who experienced syncope during the first trimester had higher odds of giving birth preterm (odds ratio, 1.3; P = .001) and of having an infant small for gestational age (OR, 1.2; P = .04) or with congenital anomalies (OR, 1.4; P = .036). Women with multiple syncope episodes versus none were twice as likely to have offspring with congenital anomalies (OR, 2.0; P = .003).

Relative to peers who did not experience syncope in pregnancy, women who did had higher incidences of cardiac arrhythmias (0.8% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) and syncope episodes (1.4% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) in the first year after delivery.

“Our data suggest that syncope during pregnancy may not be a benign occurrence,” Dr. Chatur and associates said. “More detailed clinical data are needed to identify potential causes for the observed increase in syncope during pregnancy in our study.“Whether women who experience syncope during pregnancy may benefit from closer monitoring during the obstetric and postpartum periods requires further study,” they concluded.

The investigators disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. This study was funded by a grant from the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada.

SOURCE: Chatur S et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011608.

a retrospective population-based cohort study finds. Risks appeared highest with first-trimester syncope.

“There are very limited data on the frequency of fainting during pregnancy,” Padma Kaul, Ph.D., senior study author and professor of medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, said in a statement. “In our study, fainting during pregnancy occurred in about 1%, or 10 per 1,000 pregnancies, but appears to be increasing by 5% each year.”

“Fainting during pregnancy has previously been thought to follow a relatively benign course,” Dr. Kaul said. “The findings of our study suggest that timing of fainting during pregnancy may be important. When the faint happens early during pregnancy or multiple times during pregnancy, it may be associated with both short- and long-term health issues for the baby and the mother.”

First authors Safia Chatur, MD, of the University of Calgary (Alta.) and Sunjidatul Islam, MBBS, of the Canadian Vigour Centre, Edmonton, Alta., and associates analyzed 481,930 pregnancies occurring during 2005-2014 in the province.

Study results, reported in the Journal of the American Heart Association, showed that syncope occurred in almost 1% of pregnancies (9.7 episodes per 1,000 pregnancies) overall. Incidence increased by 5% per year during the study period.

Syncope episodes were distributed across the first trimester (32%), second trimester (44%), and third trimester (24%). Eight percent of pregnancies had more than one episode.

Compared with unaffected peers, women who experienced syncope were younger (age younger than 25 years, 35% vs. 21%; P less than .001) and more often primiparous (52% vs. 42%; P less than .001).

The rate of preterm birth was 18%, 16%, and 14% in pregnancies with an initial syncope episode during the first, second, and third trimester, respectively, compared with 15% in pregnancies without syncope (P less than .01 across groups).

With a median follow-up of about 5 years, compared with peers of syncope-free pregnancies, children of pregnancies complicated by syncope had a higher incidence of congenital anomalies (3.1% vs. 2.6%; P = .023). Incidence was highest in pregnancies with multiple episodes of syncope (5% vs. 3%; P less than .01).

In adjusted analyses that accounted for multiple pregnancies in individual women, relative to counterparts with no syncope during pregnancy, women who experienced syncope during the first trimester had higher odds of giving birth preterm (odds ratio, 1.3; P = .001) and of having an infant small for gestational age (OR, 1.2; P = .04) or with congenital anomalies (OR, 1.4; P = .036). Women with multiple syncope episodes versus none were twice as likely to have offspring with congenital anomalies (OR, 2.0; P = .003).

Relative to peers who did not experience syncope in pregnancy, women who did had higher incidences of cardiac arrhythmias (0.8% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) and syncope episodes (1.4% vs. 0.2%; P less than .01) in the first year after delivery.

“Our data suggest that syncope during pregnancy may not be a benign occurrence,” Dr. Chatur and associates said. “More detailed clinical data are needed to identify potential causes for the observed increase in syncope during pregnancy in our study.“Whether women who experience syncope during pregnancy may benefit from closer monitoring during the obstetric and postpartum periods requires further study,” they concluded.

The investigators disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. This study was funded by a grant from the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada.

SOURCE: Chatur S et al. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011608.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Rapid urine test could aid in preeclampsia diagnosis

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to findings from a study of urine samples from a prospective cohort of women referred to a labor and delivery triage center to rule out the condition.

The study involved the evaluation of 349 frozen urine samples from the cohort, which included 89 preeclampsia cases (26%) as diagnosed by expert adjudication based on 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines. Visual scoring by a blinded user at 3 minutes after application of urine to the test device for 329 available samples showed 84% test sensitivity, 77% test specificity, and 93% negative predictive value, compared with the adjudicated diagnoses, Wendy L. Davis reported during an e-poster session at ACOG’s annual clinical and scientific meeting.

Of the women in the study cohort, 52% were multiparous, 91% were overweight or obese, 38% were early preterm, 31% were late preterm, and 31% were at term. Cases were described by at least one referring physician as “particularly challenging and ambiguous,” said Ms. Davis, founder and CEO of GestVision in Groton, Conn., and colleagues.

The findings, which suggest that this rapid test holds promise as an aid in the diagnosis of preeclampsia, are important as preeclampsia-associated morbidity and mortality most often occur because of a delay or misdiagnosis, they explained, also noting that diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia are “inadequate even in best care situations.”

The test – an in vitro diagnostic device known as the GestAssured Test Kit – is being developed by GestVision based on data showing that aberrant protein misfolding and aggregation is a pathogenic feature of preeclampsia. That data initially led to development of the Congo Red Dot test as a laboratory batch test, followed by development and validation of a point-of-care version of the test to allow for better integration in clinical work flow.

The GestAssured Test Kit currently in development for commercial use is based on that technology, and the current data suggest that it has slightly higher sensitivity, slightly lower specificity, and slightly higher negative predictive value than the Congo Red Dot test.

“The GestAssured test was developed specifically for preeclampsia and has a high negative predictive value, suggesting that this device, in conjunction with ACOG task force guidelines for hypertension in pregnancy, can assist in ruling out disease in patients suspected of preeclampsia,” the investigators wrote.

“[It is] particularly useful in a triage setting where you have a complex collection of patients coming in,” Ms. Davis said during the poster presentation. “And it warrants ongoing U.S. multicenter clinical studies.”

This study was funded by GestVision and Saving Lives at Birth. Ms. Davis is an employee and shareholder of GestVision and is named as an inventor or coinventor on patents licensed for commercialization to the company.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to findings from a study of urine samples from a prospective cohort of women referred to a labor and delivery triage center to rule out the condition.

The study involved the evaluation of 349 frozen urine samples from the cohort, which included 89 preeclampsia cases (26%) as diagnosed by expert adjudication based on 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines. Visual scoring by a blinded user at 3 minutes after application of urine to the test device for 329 available samples showed 84% test sensitivity, 77% test specificity, and 93% negative predictive value, compared with the adjudicated diagnoses, Wendy L. Davis reported during an e-poster session at ACOG’s annual clinical and scientific meeting.

Of the women in the study cohort, 52% were multiparous, 91% were overweight or obese, 38% were early preterm, 31% were late preterm, and 31% were at term. Cases were described by at least one referring physician as “particularly challenging and ambiguous,” said Ms. Davis, founder and CEO of GestVision in Groton, Conn., and colleagues.

The findings, which suggest that this rapid test holds promise as an aid in the diagnosis of preeclampsia, are important as preeclampsia-associated morbidity and mortality most often occur because of a delay or misdiagnosis, they explained, also noting that diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia are “inadequate even in best care situations.”

The test – an in vitro diagnostic device known as the GestAssured Test Kit – is being developed by GestVision based on data showing that aberrant protein misfolding and aggregation is a pathogenic feature of preeclampsia. That data initially led to development of the Congo Red Dot test as a laboratory batch test, followed by development and validation of a point-of-care version of the test to allow for better integration in clinical work flow.

The GestAssured Test Kit currently in development for commercial use is based on that technology, and the current data suggest that it has slightly higher sensitivity, slightly lower specificity, and slightly higher negative predictive value than the Congo Red Dot test.

“The GestAssured test was developed specifically for preeclampsia and has a high negative predictive value, suggesting that this device, in conjunction with ACOG task force guidelines for hypertension in pregnancy, can assist in ruling out disease in patients suspected of preeclampsia,” the investigators wrote.

“[It is] particularly useful in a triage setting where you have a complex collection of patients coming in,” Ms. Davis said during the poster presentation. “And it warrants ongoing U.S. multicenter clinical studies.”

This study was funded by GestVision and Saving Lives at Birth. Ms. Davis is an employee and shareholder of GestVision and is named as an inventor or coinventor on patents licensed for commercialization to the company.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – according to findings from a study of urine samples from a prospective cohort of women referred to a labor and delivery triage center to rule out the condition.

The study involved the evaluation of 349 frozen urine samples from the cohort, which included 89 preeclampsia cases (26%) as diagnosed by expert adjudication based on 2013 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines. Visual scoring by a blinded user at 3 minutes after application of urine to the test device for 329 available samples showed 84% test sensitivity, 77% test specificity, and 93% negative predictive value, compared with the adjudicated diagnoses, Wendy L. Davis reported during an e-poster session at ACOG’s annual clinical and scientific meeting.

Of the women in the study cohort, 52% were multiparous, 91% were overweight or obese, 38% were early preterm, 31% were late preterm, and 31% were at term. Cases were described by at least one referring physician as “particularly challenging and ambiguous,” said Ms. Davis, founder and CEO of GestVision in Groton, Conn., and colleagues.

The findings, which suggest that this rapid test holds promise as an aid in the diagnosis of preeclampsia, are important as preeclampsia-associated morbidity and mortality most often occur because of a delay or misdiagnosis, they explained, also noting that diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia are “inadequate even in best care situations.”

The test – an in vitro diagnostic device known as the GestAssured Test Kit – is being developed by GestVision based on data showing that aberrant protein misfolding and aggregation is a pathogenic feature of preeclampsia. That data initially led to development of the Congo Red Dot test as a laboratory batch test, followed by development and validation of a point-of-care version of the test to allow for better integration in clinical work flow.

The GestAssured Test Kit currently in development for commercial use is based on that technology, and the current data suggest that it has slightly higher sensitivity, slightly lower specificity, and slightly higher negative predictive value than the Congo Red Dot test.

“The GestAssured test was developed specifically for preeclampsia and has a high negative predictive value, suggesting that this device, in conjunction with ACOG task force guidelines for hypertension in pregnancy, can assist in ruling out disease in patients suspected of preeclampsia,” the investigators wrote.

“[It is] particularly useful in a triage setting where you have a complex collection of patients coming in,” Ms. Davis said during the poster presentation. “And it warrants ongoing U.S. multicenter clinical studies.”

This study was funded by GestVision and Saving Lives at Birth. Ms. Davis is an employee and shareholder of GestVision and is named as an inventor or coinventor on patents licensed for commercialization to the company.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

Addressing the sexual and reproductive health needs of trans and gender nonconforming patients

Separating gender identity from sexual identity to allow for more comprehensive history-taking

Grouping the term “transgender” in the abbreviation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) has historically been empowering for trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) persons. However, it also has contributed to the misunderstanding that gender identity is interchangeable with sexual identity. This common misconception can be a barrier to trans and GNC patients seeking care from ob.gyns. for their reproductive health needs.

By definition, gender identity refers to an internal experience of one’s gender, of one’s self.1 While gender identity has social implications, it ultimately is something that a person experiences independently of interactions with others. By contrast, sexual orientation has an explicitly relational underpinning because sexual orientation involves attraction to others. The distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation is similar to an internal-versus-external, or a self-versus-other dichotomy. A further nuance to add is that sexual behavior does not always reflect sexual orientation, and sexual behavior can vary along a wide spectrum when gender identity is added to the equation.

Overall, When approaching a sexual history with any patient, but especially a transgender or GNC patient, providers should think deeply about what information is medically relevant.2 The purpose of a sexual history is to identify behaviors that contribute to health risk, including pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, and social problems such as sex-trafficking or intimate partner violence. The health care provider’s job is to ask questions that will uncover these risk factors.

With the advent of a more inclusive attitude toward gay and lesbian partnership, many providers already have learned to collect the sexual history without assuming the gender of a person’s sexual contacts. Still, when a provider is taking the sexual history, gender often is inappropriately used as proxy for the type of sex that a patient may be having. For example, a provider asking a cisgender woman about her sexual activity may ask, “how many sexual partners have you had in the last year?” But then, the provider may follow-up her response of “three sexual partners in the last year” by asking “men, women, or both?” By asking a patient if the patient’s sexual partners are “men, women, or both,” providers fail to accurately elucidate the risk factors that they are actually seeking when taking a sexual history. The cisgender woman from the above scenario may reply that she has been sleeping only with women for the last year, but if the sexual partners are transgender women, aka a woman who was assigned male at birth and therefore still may use her penis/testes for sexual purposes, then the patient actually may be at risk for pregnancy and may also have a different risk factor profile for sexually transmitted infections than if the patient were sexually active with cisgender women.

A different approach to using gender in taking the sexual history is to speak plainly about which sex organs come into contact during sexual activity. When patients identify as transgender or GNC, a provider first should start by asking them what language they would like providers to use when discussing sex organs.3 One example is that many trans men, both those who have undergone mastectomy as well as those who have not, may not use the word “breasts” to describe their “chests.” This distinction may make the difference between gaining and losing the trust of a trans/GNC patient in your clinic. After identifying how a patient would like to refer to sex organs, a provider can continue by asking which of the patient’s sex partners’ organs come into contact with the patient’s organs during sexual activity. Alternatively, starting with an even more broad line of questioning may be best for some patients, such as “how do you like to have sex?”

Carefully identifying the type of sex and what sex organs are involved has concrete medical implications. Patients assigned female at birth who are on hormone therapy with testosterone may need supportive care if they continue to use their vaginas in sexual encounters because testosterone can lead to a relatively hypoestrogenic state. Patients assigned male at birth who have undergone vaginoplasty procedures may need counseling about how to use and support their neovaginas as well as adjusted testing for dysplasia. Patients assigned female at birth who want to avoid pregnancy may need a nuanced consultation regarding contraception. These are just a few examples of how obstetrician-gynecologists can better support the sexual health of their trans/GNC patients by having an accurate understanding of how a trans/GNC person has sex.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Bahng and Dr. Joyner reported no relevant financial disclosures

References

1. Sexual orientation and gender identity definitions. Human Rights Campaign.

2. Taking a sexual history from transgender people. Transforming Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Sexual health history: Talking sex with gender non-conforming and trans patients. National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute.

Separating gender identity from sexual identity to allow for more comprehensive history-taking

Separating gender identity from sexual identity to allow for more comprehensive history-taking

Grouping the term “transgender” in the abbreviation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) has historically been empowering for trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) persons. However, it also has contributed to the misunderstanding that gender identity is interchangeable with sexual identity. This common misconception can be a barrier to trans and GNC patients seeking care from ob.gyns. for their reproductive health needs.

By definition, gender identity refers to an internal experience of one’s gender, of one’s self.1 While gender identity has social implications, it ultimately is something that a person experiences independently of interactions with others. By contrast, sexual orientation has an explicitly relational underpinning because sexual orientation involves attraction to others. The distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation is similar to an internal-versus-external, or a self-versus-other dichotomy. A further nuance to add is that sexual behavior does not always reflect sexual orientation, and sexual behavior can vary along a wide spectrum when gender identity is added to the equation.

Overall, When approaching a sexual history with any patient, but especially a transgender or GNC patient, providers should think deeply about what information is medically relevant.2 The purpose of a sexual history is to identify behaviors that contribute to health risk, including pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, and social problems such as sex-trafficking or intimate partner violence. The health care provider’s job is to ask questions that will uncover these risk factors.

With the advent of a more inclusive attitude toward gay and lesbian partnership, many providers already have learned to collect the sexual history without assuming the gender of a person’s sexual contacts. Still, when a provider is taking the sexual history, gender often is inappropriately used as proxy for the type of sex that a patient may be having. For example, a provider asking a cisgender woman about her sexual activity may ask, “how many sexual partners have you had in the last year?” But then, the provider may follow-up her response of “three sexual partners in the last year” by asking “men, women, or both?” By asking a patient if the patient’s sexual partners are “men, women, or both,” providers fail to accurately elucidate the risk factors that they are actually seeking when taking a sexual history. The cisgender woman from the above scenario may reply that she has been sleeping only with women for the last year, but if the sexual partners are transgender women, aka a woman who was assigned male at birth and therefore still may use her penis/testes for sexual purposes, then the patient actually may be at risk for pregnancy and may also have a different risk factor profile for sexually transmitted infections than if the patient were sexually active with cisgender women.

A different approach to using gender in taking the sexual history is to speak plainly about which sex organs come into contact during sexual activity. When patients identify as transgender or GNC, a provider first should start by asking them what language they would like providers to use when discussing sex organs.3 One example is that many trans men, both those who have undergone mastectomy as well as those who have not, may not use the word “breasts” to describe their “chests.” This distinction may make the difference between gaining and losing the trust of a trans/GNC patient in your clinic. After identifying how a patient would like to refer to sex organs, a provider can continue by asking which of the patient’s sex partners’ organs come into contact with the patient’s organs during sexual activity. Alternatively, starting with an even more broad line of questioning may be best for some patients, such as “how do you like to have sex?”

Carefully identifying the type of sex and what sex organs are involved has concrete medical implications. Patients assigned female at birth who are on hormone therapy with testosterone may need supportive care if they continue to use their vaginas in sexual encounters because testosterone can lead to a relatively hypoestrogenic state. Patients assigned male at birth who have undergone vaginoplasty procedures may need counseling about how to use and support their neovaginas as well as adjusted testing for dysplasia. Patients assigned female at birth who want to avoid pregnancy may need a nuanced consultation regarding contraception. These are just a few examples of how obstetrician-gynecologists can better support the sexual health of their trans/GNC patients by having an accurate understanding of how a trans/GNC person has sex.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Bahng and Dr. Joyner reported no relevant financial disclosures

References

1. Sexual orientation and gender identity definitions. Human Rights Campaign.

2. Taking a sexual history from transgender people. Transforming Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Sexual health history: Talking sex with gender non-conforming and trans patients. National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute.

Grouping the term “transgender” in the abbreviation LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) has historically been empowering for trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) persons. However, it also has contributed to the misunderstanding that gender identity is interchangeable with sexual identity. This common misconception can be a barrier to trans and GNC patients seeking care from ob.gyns. for their reproductive health needs.

By definition, gender identity refers to an internal experience of one’s gender, of one’s self.1 While gender identity has social implications, it ultimately is something that a person experiences independently of interactions with others. By contrast, sexual orientation has an explicitly relational underpinning because sexual orientation involves attraction to others. The distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation is similar to an internal-versus-external, or a self-versus-other dichotomy. A further nuance to add is that sexual behavior does not always reflect sexual orientation, and sexual behavior can vary along a wide spectrum when gender identity is added to the equation.

Overall, When approaching a sexual history with any patient, but especially a transgender or GNC patient, providers should think deeply about what information is medically relevant.2 The purpose of a sexual history is to identify behaviors that contribute to health risk, including pregnancy, sexually transmitted infection, and social problems such as sex-trafficking or intimate partner violence. The health care provider’s job is to ask questions that will uncover these risk factors.

With the advent of a more inclusive attitude toward gay and lesbian partnership, many providers already have learned to collect the sexual history without assuming the gender of a person’s sexual contacts. Still, when a provider is taking the sexual history, gender often is inappropriately used as proxy for the type of sex that a patient may be having. For example, a provider asking a cisgender woman about her sexual activity may ask, “how many sexual partners have you had in the last year?” But then, the provider may follow-up her response of “three sexual partners in the last year” by asking “men, women, or both?” By asking a patient if the patient’s sexual partners are “men, women, or both,” providers fail to accurately elucidate the risk factors that they are actually seeking when taking a sexual history. The cisgender woman from the above scenario may reply that she has been sleeping only with women for the last year, but if the sexual partners are transgender women, aka a woman who was assigned male at birth and therefore still may use her penis/testes for sexual purposes, then the patient actually may be at risk for pregnancy and may also have a different risk factor profile for sexually transmitted infections than if the patient were sexually active with cisgender women.

A different approach to using gender in taking the sexual history is to speak plainly about which sex organs come into contact during sexual activity. When patients identify as transgender or GNC, a provider first should start by asking them what language they would like providers to use when discussing sex organs.3 One example is that many trans men, both those who have undergone mastectomy as well as those who have not, may not use the word “breasts” to describe their “chests.” This distinction may make the difference between gaining and losing the trust of a trans/GNC patient in your clinic. After identifying how a patient would like to refer to sex organs, a provider can continue by asking which of the patient’s sex partners’ organs come into contact with the patient’s organs during sexual activity. Alternatively, starting with an even more broad line of questioning may be best for some patients, such as “how do you like to have sex?”

Carefully identifying the type of sex and what sex organs are involved has concrete medical implications. Patients assigned female at birth who are on hormone therapy with testosterone may need supportive care if they continue to use their vaginas in sexual encounters because testosterone can lead to a relatively hypoestrogenic state. Patients assigned male at birth who have undergone vaginoplasty procedures may need counseling about how to use and support their neovaginas as well as adjusted testing for dysplasia. Patients assigned female at birth who want to avoid pregnancy may need a nuanced consultation regarding contraception. These are just a few examples of how obstetrician-gynecologists can better support the sexual health of their trans/GNC patients by having an accurate understanding of how a trans/GNC person has sex.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Bahng and Dr. Joyner reported no relevant financial disclosures

References

1. Sexual orientation and gender identity definitions. Human Rights Campaign.

2. Taking a sexual history from transgender people. Transforming Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

3. Sexual health history: Talking sex with gender non-conforming and trans patients. National LGBT Health Education Center at The Fenway Institute.

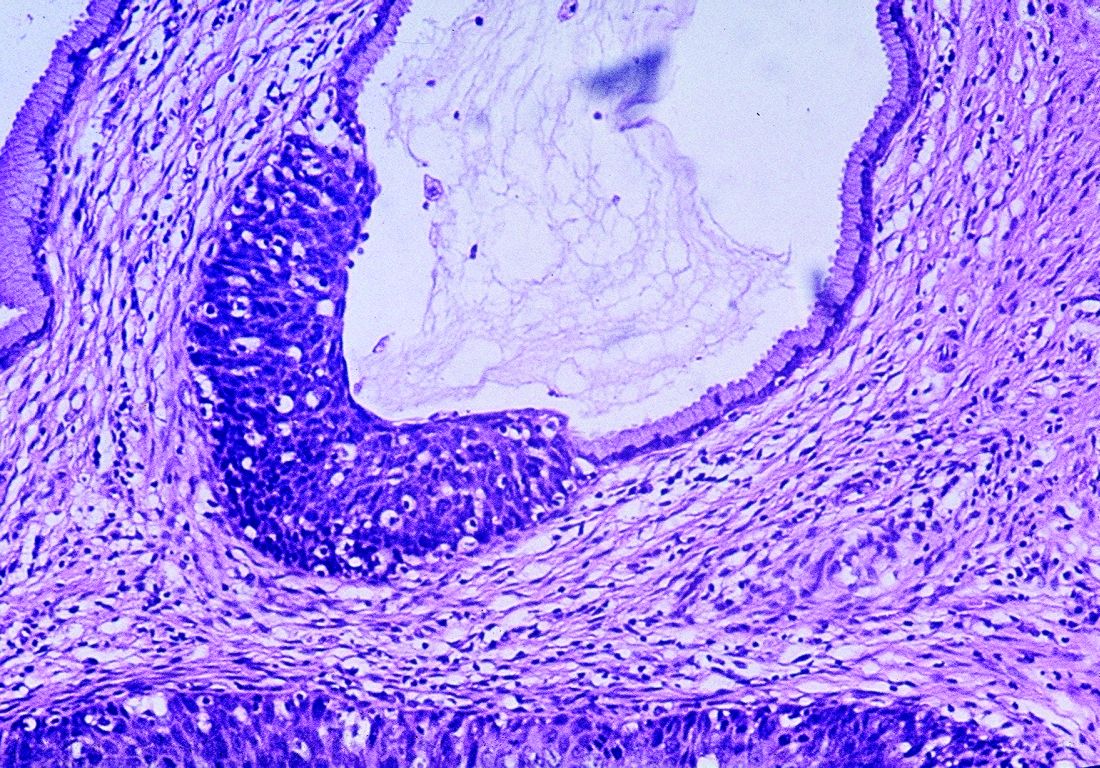

Targeted sequencing panel IDs Lynch syndrome in women with/at risk for endometrial cancer

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , according to findings in a prospective patient cohort.

The findings, which also suggest that the incidence of Lynch syndrome among endometrial cancer patients is higher than previously recognized, have “immediate and major implications for the individual patient with endometrial cancer ... and implications for related family members,” Maria Mercedes M. Padron, MD, reported during an e-poster session at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Of 71 patients included in the study, 67 were undergoing endometrial cancer treatment and 7 (3 among those undergoing endometrial cancer treatment and 4 who did not have endometrial cancer) were known to have Lynch syndrome.

Of the 67 undergoing treatment, 22 (33%) were identified by the direct sequencing panel as having Lynch syndrome mutations, and of those, 7 (10%) had mutations classified as high confidence inactivating mutations in either MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, or MSH2 genes, said Dr. Padron, a research scholar at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. The remaining 15 patients had rare mutations and met previously defined phenotypic criteria for Lynch syndrome pathogenicity, she reported.

The sequencing panel–based results were compared with commercially available gene tests, including immunohistochemistry (IHC) and microsatellite instability testing (MSI); 10 patients were identified by IHC to have loss of nuclear mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression, and 8 of those were Lynch syndrome mutation positive. In addition, two patients were MSI-high, and both of those were Lynch syndrome mutation positive.

Thus, two Lynch syndrome patients were missed by direct sequencing, noted Dr. Padron.

However, an additional 10 patients who were not identified as having Lynch syndrome by IHC and MSI testing were potentially identified as such using the sequencing panel, Dr. Padron said, noting that “the pathogenicity of these additional variants needs to be defined.”

Lynch syndrome is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by germline mutations in DNA MMR genes; it is the third most common malignancy in women and it confers an increased risk of several types of cancer, including colorectal, ovarian, gastric, and endometrial cancer, among others.

“It is estimated that 3% to 5% of endometrial cancers will arise from Lynch syndrome,” Dr. Padron explained during the poster session.

Because the presence of Lynch syndrome directly affects immediate clinical management and future risk-reducing and surveillance strategies for patients and at-risk family members, screening is recommended in all women with endometrial cancer, she added, noting, however, that “the optimum screening method has yet to be established.”

The sequencing panel evaluated in this study – Swift’s Accel-Amplicon Plus Lynch Syndrome Panel – requires only low input amounts of DNA, and in an earlier test using 10 control samples, it exhibited greater than 90% on-target and coverage uniformity. The work flow allowed for data analysis within 2 days, Dr. Padron noted.

The panel then was tested in the current cohort of patients who were referred to a gynecology oncology clinic for either treatment of endometrial cancer or for evaluation of risk for endometrial cancer.

Germline/tumor DNA was isolated and 10 ng DNA was used for targeted exon-level hotspot coverage of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

The findings suggest that the prevalence of Lynch syndrome may be six to seven times greater than previously estimated, Dr. Padron said during the poster presentation.

“If confirmed, this would have huge implications for our patients and health care system,” she said, adding that the ability to perform and analyze the sequencing within 48 hours of sample collection using a very low DNA input also was of note.

Taken together, “the findings of this study support future larger studies that can be performed concurrently with current standard of care technologies,” she and her colleagues concluded, noting that such studies would better determine more robust estimates of the prevalence of Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer, help define improved standard-of-care guidelines, and provide future guidance for possible universal/targeted screening programs – all with the goal of improving the clinical care of women.

Dr. Padron reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , according to findings in a prospective patient cohort.

The findings, which also suggest that the incidence of Lynch syndrome among endometrial cancer patients is higher than previously recognized, have “immediate and major implications for the individual patient with endometrial cancer ... and implications for related family members,” Maria Mercedes M. Padron, MD, reported during an e-poster session at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Of 71 patients included in the study, 67 were undergoing endometrial cancer treatment and 7 (3 among those undergoing endometrial cancer treatment and 4 who did not have endometrial cancer) were known to have Lynch syndrome.

Of the 67 undergoing treatment, 22 (33%) were identified by the direct sequencing panel as having Lynch syndrome mutations, and of those, 7 (10%) had mutations classified as high confidence inactivating mutations in either MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, or MSH2 genes, said Dr. Padron, a research scholar at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. The remaining 15 patients had rare mutations and met previously defined phenotypic criteria for Lynch syndrome pathogenicity, she reported.

The sequencing panel–based results were compared with commercially available gene tests, including immunohistochemistry (IHC) and microsatellite instability testing (MSI); 10 patients were identified by IHC to have loss of nuclear mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression, and 8 of those were Lynch syndrome mutation positive. In addition, two patients were MSI-high, and both of those were Lynch syndrome mutation positive.

Thus, two Lynch syndrome patients were missed by direct sequencing, noted Dr. Padron.

However, an additional 10 patients who were not identified as having Lynch syndrome by IHC and MSI testing were potentially identified as such using the sequencing panel, Dr. Padron said, noting that “the pathogenicity of these additional variants needs to be defined.”

Lynch syndrome is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by germline mutations in DNA MMR genes; it is the third most common malignancy in women and it confers an increased risk of several types of cancer, including colorectal, ovarian, gastric, and endometrial cancer, among others.

“It is estimated that 3% to 5% of endometrial cancers will arise from Lynch syndrome,” Dr. Padron explained during the poster session.

Because the presence of Lynch syndrome directly affects immediate clinical management and future risk-reducing and surveillance strategies for patients and at-risk family members, screening is recommended in all women with endometrial cancer, she added, noting, however, that “the optimum screening method has yet to be established.”

The sequencing panel evaluated in this study – Swift’s Accel-Amplicon Plus Lynch Syndrome Panel – requires only low input amounts of DNA, and in an earlier test using 10 control samples, it exhibited greater than 90% on-target and coverage uniformity. The work flow allowed for data analysis within 2 days, Dr. Padron noted.

The panel then was tested in the current cohort of patients who were referred to a gynecology oncology clinic for either treatment of endometrial cancer or for evaluation of risk for endometrial cancer.

Germline/tumor DNA was isolated and 10 ng DNA was used for targeted exon-level hotspot coverage of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

The findings suggest that the prevalence of Lynch syndrome may be six to seven times greater than previously estimated, Dr. Padron said during the poster presentation.

“If confirmed, this would have huge implications for our patients and health care system,” she said, adding that the ability to perform and analyze the sequencing within 48 hours of sample collection using a very low DNA input also was of note.

Taken together, “the findings of this study support future larger studies that can be performed concurrently with current standard of care technologies,” she and her colleagues concluded, noting that such studies would better determine more robust estimates of the prevalence of Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer, help define improved standard-of-care guidelines, and provide future guidance for possible universal/targeted screening programs – all with the goal of improving the clinical care of women.

Dr. Padron reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – , according to findings in a prospective patient cohort.

The findings, which also suggest that the incidence of Lynch syndrome among endometrial cancer patients is higher than previously recognized, have “immediate and major implications for the individual patient with endometrial cancer ... and implications for related family members,” Maria Mercedes M. Padron, MD, reported during an e-poster session at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Of 71 patients included in the study, 67 were undergoing endometrial cancer treatment and 7 (3 among those undergoing endometrial cancer treatment and 4 who did not have endometrial cancer) were known to have Lynch syndrome.

Of the 67 undergoing treatment, 22 (33%) were identified by the direct sequencing panel as having Lynch syndrome mutations, and of those, 7 (10%) had mutations classified as high confidence inactivating mutations in either MLH1, MSH6, PMS2, or MSH2 genes, said Dr. Padron, a research scholar at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. The remaining 15 patients had rare mutations and met previously defined phenotypic criteria for Lynch syndrome pathogenicity, she reported.

The sequencing panel–based results were compared with commercially available gene tests, including immunohistochemistry (IHC) and microsatellite instability testing (MSI); 10 patients were identified by IHC to have loss of nuclear mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression, and 8 of those were Lynch syndrome mutation positive. In addition, two patients were MSI-high, and both of those were Lynch syndrome mutation positive.

Thus, two Lynch syndrome patients were missed by direct sequencing, noted Dr. Padron.

However, an additional 10 patients who were not identified as having Lynch syndrome by IHC and MSI testing were potentially identified as such using the sequencing panel, Dr. Padron said, noting that “the pathogenicity of these additional variants needs to be defined.”

Lynch syndrome is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by germline mutations in DNA MMR genes; it is the third most common malignancy in women and it confers an increased risk of several types of cancer, including colorectal, ovarian, gastric, and endometrial cancer, among others.

“It is estimated that 3% to 5% of endometrial cancers will arise from Lynch syndrome,” Dr. Padron explained during the poster session.

Because the presence of Lynch syndrome directly affects immediate clinical management and future risk-reducing and surveillance strategies for patients and at-risk family members, screening is recommended in all women with endometrial cancer, she added, noting, however, that “the optimum screening method has yet to be established.”

The sequencing panel evaluated in this study – Swift’s Accel-Amplicon Plus Lynch Syndrome Panel – requires only low input amounts of DNA, and in an earlier test using 10 control samples, it exhibited greater than 90% on-target and coverage uniformity. The work flow allowed for data analysis within 2 days, Dr. Padron noted.

The panel then was tested in the current cohort of patients who were referred to a gynecology oncology clinic for either treatment of endometrial cancer or for evaluation of risk for endometrial cancer.

Germline/tumor DNA was isolated and 10 ng DNA was used for targeted exon-level hotspot coverage of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.

The findings suggest that the prevalence of Lynch syndrome may be six to seven times greater than previously estimated, Dr. Padron said during the poster presentation.

“If confirmed, this would have huge implications for our patients and health care system,” she said, adding that the ability to perform and analyze the sequencing within 48 hours of sample collection using a very low DNA input also was of note.

Taken together, “the findings of this study support future larger studies that can be performed concurrently with current standard of care technologies,” she and her colleagues concluded, noting that such studies would better determine more robust estimates of the prevalence of Lynch syndrome in women with endometrial cancer, help define improved standard-of-care guidelines, and provide future guidance for possible universal/targeted screening programs – all with the goal of improving the clinical care of women.

Dr. Padron reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2019

For some MST survivors, VA hospitals can trigger PTSD

Alternative treatment settings could be ‘easier access point’

SAN FRANCISCO – Veterans who are survivors of military sexual trauma during their service face unique challenges in their treatment and recovery. They are often reluctant to report their experiences – and understandably so.

“Military sexual assault represents a huge violation of that trust and safety. That’s what makes it so toxic and hard for participants to [come] forward, because they’re accused of breaking cohesion of their unit and breaking morale, and yet they have been mistreated,” Niranjan Karnik, MD, PhD, associate dean for community behavioral health at Rush Medical College, Chicago, said in an interview.

Dr. Karnik moderated a session on the prevalence and treatment of military sexual assault at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Although the Department of Veterans Affairs treats many survivors of sexual assault, not all of them feel comfortable in that environment. “A VA hospital has a quasi-military feel to it, and that’s a reflection of what it is and the people who are there. That can be an inhibition – and can even be a trigger for [PTSD] symptoms,” Dr. Karnik said.

Survivors may also worry about being labeled, or about adverse entries going into their official record and how that could affect them in the future. The issue is a stark contrast to veterans who are suffering from combat-related trauma.

“When a combat trauma survivor goes to the VA, they feel protected because their colleagues are there. With military sexual trauma, because of that violation of trust from their peers, it can really exacerbate things,” Dr. Karnik said.

Fortunately, there are alternatives, such as the Road Home* Program at Rush Hospital, which has a few military accoutrements but more closely resembles a civilian center. “It can be an easier access point. The VA is taking care of a large majority of patients. We are a boutique program for the vets who can’t or feel unable to go through the VA program,” Dr. Karnik said.

Overall, 52.5% of women and 8.9% of men in the military report sexual harassment, and 23.6% of women and 1.9% of men report being sexually assaulted. That amounts to 14,900 service members, 8,600 women, and 6,300 men who were assaulted in 2016, according to Neeral K. Sheth, DO, assistant professor of psychiatry at Rush Medical College, who also presented at the session. The frequency of assault is higher among LGBTQ individuals, and African American men and women are more likely to experience sexual harassment.

There are options for treatment of military sexual trauma (MST). The 3-week Road Home intensive outpatient treatment program at Rush Hospital combines group and individual cognitive-processing therapy, which is a cognitive-behavioral therapy that has been shown to improve PTSD resulting from MST. The program places combat trauma and MST trauma patients into separate cohorts, each containing individual and group components. Individual sessions closely follow a manualized protocol, while group sessions offer an opportunity to practice cognitive-processing therapy skills.

The team adapted the program to MST treatment by incorporating dialectical-behavioral therapy skills modules in the first week of the program, and implemented one-on-one skills consultation by request throughout the program.

An analysis of 191 subjects participating in 19 cohorts (12 combat, 9 MST cohorts) showed a 92% completion rate, which was similar, regardless of gender or cohort type. Both cohorts had significant reductions in PTSD severity as measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, and depression symptoms as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire–9.

Another program, Families OverComing Under Stress, can also be adapted to MST. It is designed to build resiliency and wellness within families dealing with trauma or loss. It incorporates family assessment, psychoeducation tailored to the needs of the entire family, family-level resilience skills, and a narrative component.

An important element is the identification and management of stress reminders – triggers that remind the individual of a trauma and may cause a sudden shift in mood or behavior. A family member’s knowledge that the survivor is experiencing a stress reminder can reduce misunderstandings or unhelpful interpretations of behavior.

In fact, family considerations are often what bring veterans in for help in the first place, according to Dr. Karnik. He or she may be concerned about behavioral problems in a child, which the VA cannot address because its federal funding dictates a sole focus on the veteran. “We will take care of the whole family,” Dr. Karnik said. “Often that’s the entry point, and that allows us to do some engagement with the veteran, and things start to get uncovered.”

Dr. Karnik has no relevant financial disclosures.

*CORRECTION, 5/21/2019

Alternative treatment settings could be ‘easier access point’

Alternative treatment settings could be ‘easier access point’

SAN FRANCISCO – Veterans who are survivors of military sexual trauma during their service face unique challenges in their treatment and recovery. They are often reluctant to report their experiences – and understandably so.

“Military sexual assault represents a huge violation of that trust and safety. That’s what makes it so toxic and hard for participants to [come] forward, because they’re accused of breaking cohesion of their unit and breaking morale, and yet they have been mistreated,” Niranjan Karnik, MD, PhD, associate dean for community behavioral health at Rush Medical College, Chicago, said in an interview.

Dr. Karnik moderated a session on the prevalence and treatment of military sexual assault at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Although the Department of Veterans Affairs treats many survivors of sexual assault, not all of them feel comfortable in that environment. “A VA hospital has a quasi-military feel to it, and that’s a reflection of what it is and the people who are there. That can be an inhibition – and can even be a trigger for [PTSD] symptoms,” Dr. Karnik said.

Survivors may also worry about being labeled, or about adverse entries going into their official record and how that could affect them in the future. The issue is a stark contrast to veterans who are suffering from combat-related trauma.

“When a combat trauma survivor goes to the VA, they feel protected because their colleagues are there. With military sexual trauma, because of that violation of trust from their peers, it can really exacerbate things,” Dr. Karnik said.

Fortunately, there are alternatives, such as the Road Home* Program at Rush Hospital, which has a few military accoutrements but more closely resembles a civilian center. “It can be an easier access point. The VA is taking care of a large majority of patients. We are a boutique program for the vets who can’t or feel unable to go through the VA program,” Dr. Karnik said.

Overall, 52.5% of women and 8.9% of men in the military report sexual harassment, and 23.6% of women and 1.9% of men report being sexually assaulted. That amounts to 14,900 service members, 8,600 women, and 6,300 men who were assaulted in 2016, according to Neeral K. Sheth, DO, assistant professor of psychiatry at Rush Medical College, who also presented at the session. The frequency of assault is higher among LGBTQ individuals, and African American men and women are more likely to experience sexual harassment.

There are options for treatment of military sexual trauma (MST). The 3-week Road Home intensive outpatient treatment program at Rush Hospital combines group and individual cognitive-processing therapy, which is a cognitive-behavioral therapy that has been shown to improve PTSD resulting from MST. The program places combat trauma and MST trauma patients into separate cohorts, each containing individual and group components. Individual sessions closely follow a manualized protocol, while group sessions offer an opportunity to practice cognitive-processing therapy skills.

The team adapted the program to MST treatment by incorporating dialectical-behavioral therapy skills modules in the first week of the program, and implemented one-on-one skills consultation by request throughout the program.

An analysis of 191 subjects participating in 19 cohorts (12 combat, 9 MST cohorts) showed a 92% completion rate, which was similar, regardless of gender or cohort type. Both cohorts had significant reductions in PTSD severity as measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, and depression symptoms as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire–9.

Another program, Families OverComing Under Stress, can also be adapted to MST. It is designed to build resiliency and wellness within families dealing with trauma or loss. It incorporates family assessment, psychoeducation tailored to the needs of the entire family, family-level resilience skills, and a narrative component.

An important element is the identification and management of stress reminders – triggers that remind the individual of a trauma and may cause a sudden shift in mood or behavior. A family member’s knowledge that the survivor is experiencing a stress reminder can reduce misunderstandings or unhelpful interpretations of behavior.

In fact, family considerations are often what bring veterans in for help in the first place, according to Dr. Karnik. He or she may be concerned about behavioral problems in a child, which the VA cannot address because its federal funding dictates a sole focus on the veteran. “We will take care of the whole family,” Dr. Karnik said. “Often that’s the entry point, and that allows us to do some engagement with the veteran, and things start to get uncovered.”

Dr. Karnik has no relevant financial disclosures.

*CORRECTION, 5/21/2019

SAN FRANCISCO – Veterans who are survivors of military sexual trauma during their service face unique challenges in their treatment and recovery. They are often reluctant to report their experiences – and understandably so.

“Military sexual assault represents a huge violation of that trust and safety. That’s what makes it so toxic and hard for participants to [come] forward, because they’re accused of breaking cohesion of their unit and breaking morale, and yet they have been mistreated,” Niranjan Karnik, MD, PhD, associate dean for community behavioral health at Rush Medical College, Chicago, said in an interview.

Dr. Karnik moderated a session on the prevalence and treatment of military sexual assault at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Although the Department of Veterans Affairs treats many survivors of sexual assault, not all of them feel comfortable in that environment. “A VA hospital has a quasi-military feel to it, and that’s a reflection of what it is and the people who are there. That can be an inhibition – and can even be a trigger for [PTSD] symptoms,” Dr. Karnik said.

Survivors may also worry about being labeled, or about adverse entries going into their official record and how that could affect them in the future. The issue is a stark contrast to veterans who are suffering from combat-related trauma.

“When a combat trauma survivor goes to the VA, they feel protected because their colleagues are there. With military sexual trauma, because of that violation of trust from their peers, it can really exacerbate things,” Dr. Karnik said.

Fortunately, there are alternatives, such as the Road Home* Program at Rush Hospital, which has a few military accoutrements but more closely resembles a civilian center. “It can be an easier access point. The VA is taking care of a large majority of patients. We are a boutique program for the vets who can’t or feel unable to go through the VA program,” Dr. Karnik said.

Overall, 52.5% of women and 8.9% of men in the military report sexual harassment, and 23.6% of women and 1.9% of men report being sexually assaulted. That amounts to 14,900 service members, 8,600 women, and 6,300 men who were assaulted in 2016, according to Neeral K. Sheth, DO, assistant professor of psychiatry at Rush Medical College, who also presented at the session. The frequency of assault is higher among LGBTQ individuals, and African American men and women are more likely to experience sexual harassment.

There are options for treatment of military sexual trauma (MST). The 3-week Road Home intensive outpatient treatment program at Rush Hospital combines group and individual cognitive-processing therapy, which is a cognitive-behavioral therapy that has been shown to improve PTSD resulting from MST. The program places combat trauma and MST trauma patients into separate cohorts, each containing individual and group components. Individual sessions closely follow a manualized protocol, while group sessions offer an opportunity to practice cognitive-processing therapy skills.

The team adapted the program to MST treatment by incorporating dialectical-behavioral therapy skills modules in the first week of the program, and implemented one-on-one skills consultation by request throughout the program.

An analysis of 191 subjects participating in 19 cohorts (12 combat, 9 MST cohorts) showed a 92% completion rate, which was similar, regardless of gender or cohort type. Both cohorts had significant reductions in PTSD severity as measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, and depression symptoms as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire–9.

Another program, Families OverComing Under Stress, can also be adapted to MST. It is designed to build resiliency and wellness within families dealing with trauma or loss. It incorporates family assessment, psychoeducation tailored to the needs of the entire family, family-level resilience skills, and a narrative component.

An important element is the identification and management of stress reminders – triggers that remind the individual of a trauma and may cause a sudden shift in mood or behavior. A family member’s knowledge that the survivor is experiencing a stress reminder can reduce misunderstandings or unhelpful interpretations of behavior.

In fact, family considerations are often what bring veterans in for help in the first place, according to Dr. Karnik. He or she may be concerned about behavioral problems in a child, which the VA cannot address because its federal funding dictates a sole focus on the veteran. “We will take care of the whole family,” Dr. Karnik said. “Often that’s the entry point, and that allows us to do some engagement with the veteran, and things start to get uncovered.”

Dr. Karnik has no relevant financial disclosures.

*CORRECTION, 5/21/2019

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

More empathy for women

At the risk of too much personal self-disclosure, I feel the need to write about my having developed more empathy for women. Having been described as a “manly man,” by a woman who feels she knows me, it has always been difficult for me to understand women. Fortunately, an experience I’ve had has given me more insight into women – shallow though it may still be.

About a year ago, I had learned I had prostate carcinoma, which is now in remission – thanks to a proctectomy, radiation, and hormone therapy. The antitestosterone hormones I need to take for 2 years are turning me into an old woman, thus my newfound empathy.

After the surgery, I found myself leaking – something that I probably only experienced as a child and of which I have little memory. I now have some more empathy for the problems women have with leaking each month or in general – it is a constant preoccupation. The leuprolide shots I am taking are giving me hot flashes, causing me to be more emotional about things I really don’t understand, and apparently I am at risk for getting osteoporosis – all things that happen to women that have been mildly on my radar for years but for which I lacked direct and personal experience.

Since having my testosterone turned off by the leuprolide, my joints are more prone to aches and pains from various injuries over the years. Because I understand that “motion is lotion,” I have some control of this problem. However, the hormone therapy has greatly reduced my endurance, so my exercise tolerance is far more limited – I understand fatigue now. When I was telling another woman who feels she knows me about my experience, she told me it was hormones that made it more difficult to lose weight. And, I am gaining weight.

All in all, I believe my experience has given me more empathy for women, but I realize I still have a very long way to go. Nonetheless, I will continue in my quest to understand the opposite sex, as I am told “women hold up half the sky,” and I have always believed that to be true.

Fortunately, women are ascending in psychiatry and, with some serious dedication, the dearth of scientific understanding of women’s issues will be a thing of the past. and fill that void of knowledge that we men psychiatrists have in our testosterone-bathed brains.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

At the risk of too much personal self-disclosure, I feel the need to write about my having developed more empathy for women. Having been described as a “manly man,” by a woman who feels she knows me, it has always been difficult for me to understand women. Fortunately, an experience I’ve had has given me more insight into women – shallow though it may still be.

About a year ago, I had learned I had prostate carcinoma, which is now in remission – thanks to a proctectomy, radiation, and hormone therapy. The antitestosterone hormones I need to take for 2 years are turning me into an old woman, thus my newfound empathy.

After the surgery, I found myself leaking – something that I probably only experienced as a child and of which I have little memory. I now have some more empathy for the problems women have with leaking each month or in general – it is a constant preoccupation. The leuprolide shots I am taking are giving me hot flashes, causing me to be more emotional about things I really don’t understand, and apparently I am at risk for getting osteoporosis – all things that happen to women that have been mildly on my radar for years but for which I lacked direct and personal experience.

Since having my testosterone turned off by the leuprolide, my joints are more prone to aches and pains from various injuries over the years. Because I understand that “motion is lotion,” I have some control of this problem. However, the hormone therapy has greatly reduced my endurance, so my exercise tolerance is far more limited – I understand fatigue now. When I was telling another woman who feels she knows me about my experience, she told me it was hormones that made it more difficult to lose weight. And, I am gaining weight.

All in all, I believe my experience has given me more empathy for women, but I realize I still have a very long way to go. Nonetheless, I will continue in my quest to understand the opposite sex, as I am told “women hold up half the sky,” and I have always believed that to be true.

Fortunately, women are ascending in psychiatry and, with some serious dedication, the dearth of scientific understanding of women’s issues will be a thing of the past. and fill that void of knowledge that we men psychiatrists have in our testosterone-bathed brains.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

At the risk of too much personal self-disclosure, I feel the need to write about my having developed more empathy for women. Having been described as a “manly man,” by a woman who feels she knows me, it has always been difficult for me to understand women. Fortunately, an experience I’ve had has given me more insight into women – shallow though it may still be.

About a year ago, I had learned I had prostate carcinoma, which is now in remission – thanks to a proctectomy, radiation, and hormone therapy. The antitestosterone hormones I need to take for 2 years are turning me into an old woman, thus my newfound empathy.

After the surgery, I found myself leaking – something that I probably only experienced as a child and of which I have little memory. I now have some more empathy for the problems women have with leaking each month or in general – it is a constant preoccupation. The leuprolide shots I am taking are giving me hot flashes, causing me to be more emotional about things I really don’t understand, and apparently I am at risk for getting osteoporosis – all things that happen to women that have been mildly on my radar for years but for which I lacked direct and personal experience.

Since having my testosterone turned off by the leuprolide, my joints are more prone to aches and pains from various injuries over the years. Because I understand that “motion is lotion,” I have some control of this problem. However, the hormone therapy has greatly reduced my endurance, so my exercise tolerance is far more limited – I understand fatigue now. When I was telling another woman who feels she knows me about my experience, she told me it was hormones that made it more difficult to lose weight. And, I am gaining weight.

All in all, I believe my experience has given me more empathy for women, but I realize I still have a very long way to go. Nonetheless, I will continue in my quest to understand the opposite sex, as I am told “women hold up half the sky,” and I have always believed that to be true.

Fortunately, women are ascending in psychiatry and, with some serious dedication, the dearth of scientific understanding of women’s issues will be a thing of the past. and fill that void of knowledge that we men psychiatrists have in our testosterone-bathed brains.

Dr. Bell is a staff psychiatrist at Jackson Park Hospital’s Medical/Surgical-Psychiatry Inpatient Unit in Chicago, clinical psychiatrist emeritus in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, former president/CEO of Community Mental Health Council, and former director of the Institute for Juvenile Research (birthplace of child psychiatry), also in Chicago.

Thrice yearly cytologic testing may best annual cervical screenings

Less-frequent cytologic testing, followed by hrHPV tests

George F. Sawaya, MD, from the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues enrolled 451 English-speaking or Spanish-speaking women aged 21-65 years from women’s health clinics between September 2014 and June 2016. The women were mean 38 years old, and 57% were nonwhite women. The researchers examined utilities for 23 different health states associated with cervical cancer, and created a Markov decision model of type-specific high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV)–induced cervical carcinogenesis.

The researchers evaluated 12 screening strategies, which included the following scenarios:

- For women aged 21-65 years, cytologic testing every 3 years; if atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) are found, repeat cytologic testing in 1 year or switch to immediate hrHPV triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with cytologic testing plus hrHPV testing (cotesting) for women 30-65 years old; if a normal cytologic test result and positive hrHPV test results, move to cotesting in 1 year or immediate genotyping triage.

- For women 21-29 years, cytologic testing every 3 years, and then followed with hrHPV testing alone every 3-5 years for women 30-65 years; if there are positive hrHPV results, move to immediate cytologic testing triage or immediate genotyping triage. Women with positive hrHPV and negative genotyping results receive additional cytologic testing triage.

In the strategies that switched the women from cytologic testing to hrHPV tests, the study also tested doing the switch at age 25 years rather than 30 years, the investigators reported.

Overall, with regard to cost, screening resulted in more cost savings ($1,267-$2,577) than not screening ($2,891 per woman). Women received the most benefit as measured by lifetime quality-adjusted life-years (QALY) if they received cytologic test every 3 years and received repeat testing for ASCUS. The strategy with the lowest cost was cytologic testing every 3 years and hrHPV triage for ASCUS ($1,267), and the strategy of 3-year cytology testing with repeat testing for ASCUS had more QALY but at a higher cost ($2,166). Other higher-cost strategies relative to QALYs included cotesting and primary hrHPV and also annual cytologic testing ($2,577).

“Both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Cancer Society consider cotesting the preferred cervical cancer screening strategy, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force considers it an alternative strategy,” Dr. Sawaya and colleagues noted. “Our findings challenge these endorsements.”

“Our analyses suggest that it is not cost effective to begin primary hrHPV testing prior to age 30 years, to perform hrHPV testing every 3 years, or to perform cytologic testing annually. Comparative modeling is needed to confirm these findings,” they concluded.

Dual stain vs. cytologic testing alone

In a second study, Nicolas Wentzensen, MD, PhD, from the National Cancer Institute and colleagues performed a prospective observational study of 3,225 women who tested positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) who underwent p16/Ki-67 dual stain (DS) and HPV16/18 genotyping.

p16/Ki-67 DS was more effective at risk stratification for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe neoplasia (CIN3+) than cytologic testing alone, and women with positive DS results had a higher risk of developing CIN3+ (12%) than did women with cytologic testing alone (10%; P = .005). Women who were HPV16/18 negative were the most likely to not have CIN3+ if they had negative DS results, and DS strategies resulted in fewer overall colposcopies relative to CIN3+ detections, compared with cytologic testing alone.

“We found that, for primary HPV screening, DS has both higher sensitivity and specificity compared with cytologic testing for triage of HPV-positive women Because of the greater reassurance of negative DS results, screening intervals can be extended compared with the screening intervals after negative cytologic results. Dual stain reduces unnecessary colposcopy referral and unnecessary cervical biopsies, and may reduce unnecessary treatment compared with Papanicolaou cytologic testing,” Dr. Wentzensen and colleagues concluded. “Our estimates of sensitivity, absolute risk, and colposcopy referral for various triage strategies can guide implementation of primary HPV screening.”

Five authors of Sawaya et al. reported receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute, and Dr. Megan J. Huchko reported receiving a grant from the University of California, San Francisco, during that study. That study was funded by a grant from the NCI. Six authors from Wentzensen et al. reported receiving grants from the NCI or being employed by the NCI or NIH. Dr. Philip E. Castle reported receiving low-cost or free cervical screening tests from Roche, Becton Dickinson, Cepheid, and Arbor Vita Corp. The other authors from both studies reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCES: Sawaya GF et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0299; Wentzensen N et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0306.