User login

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

To the Editor:

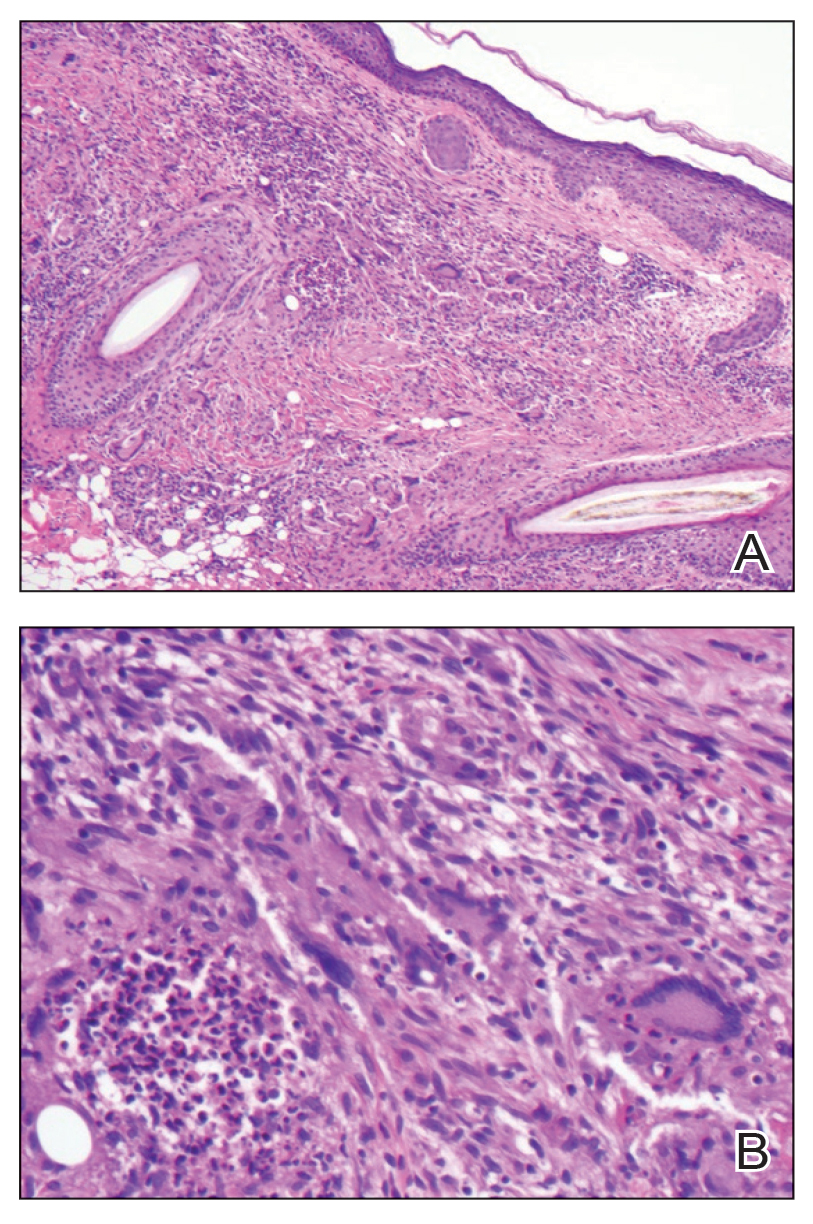

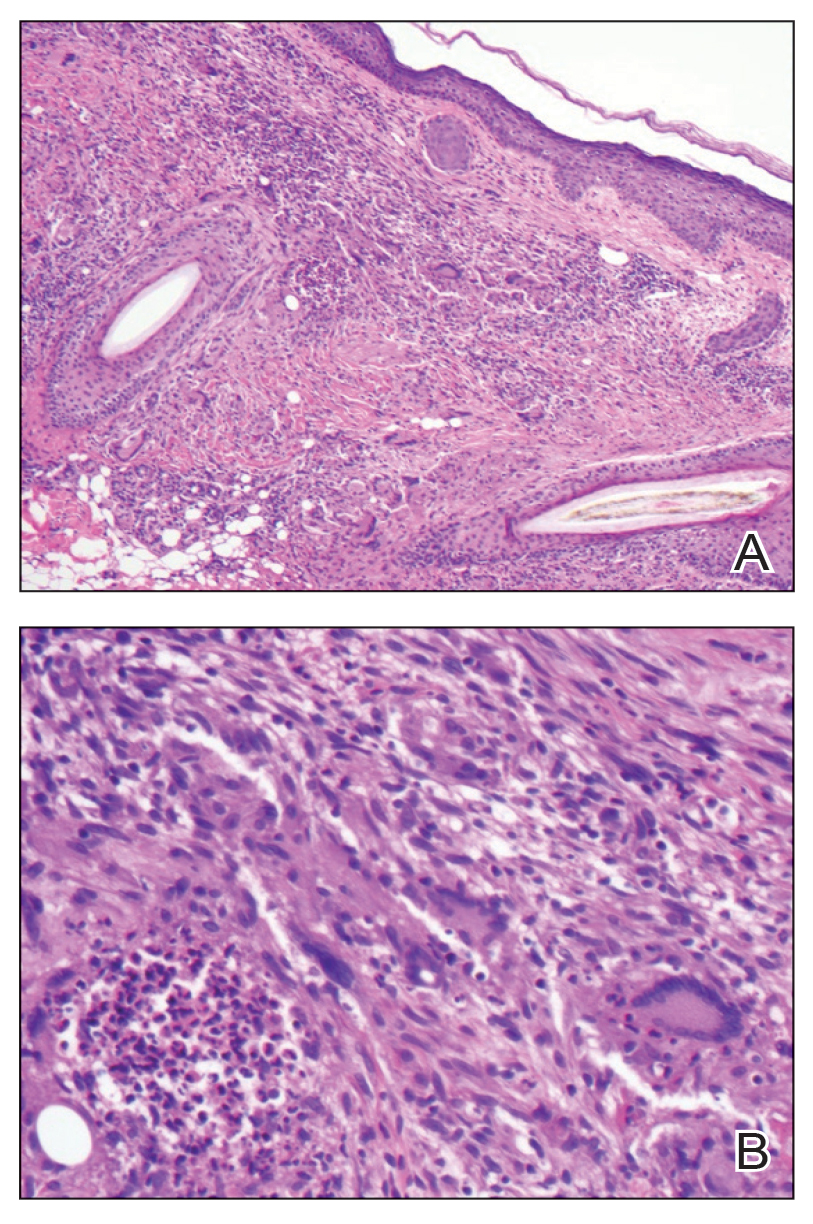

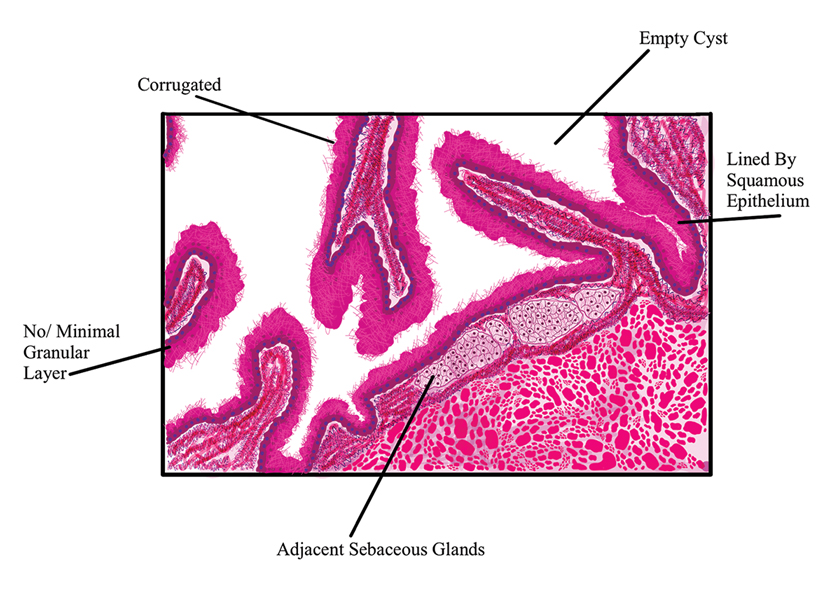

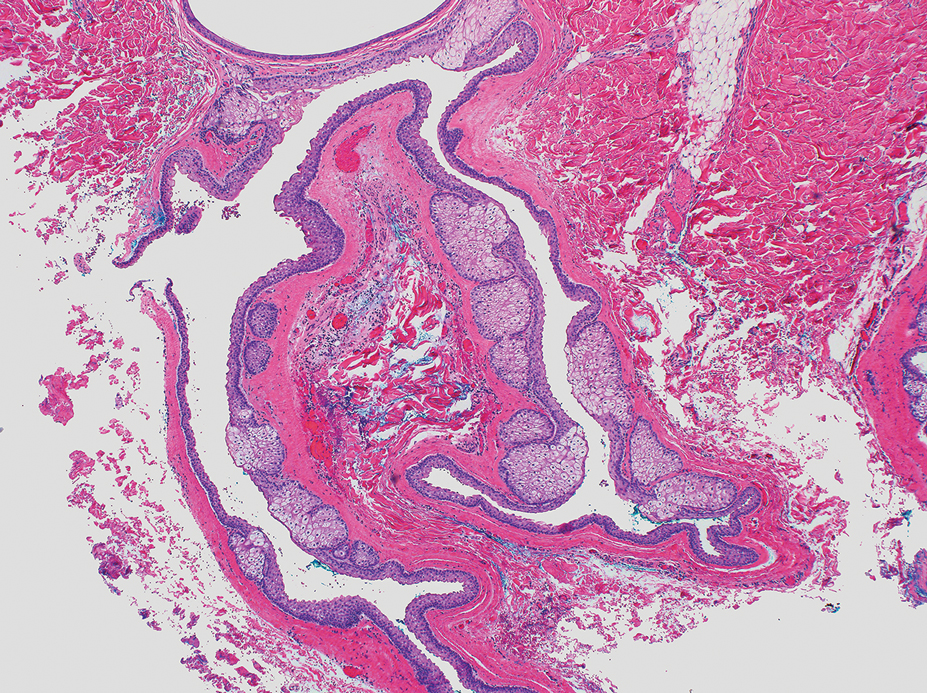

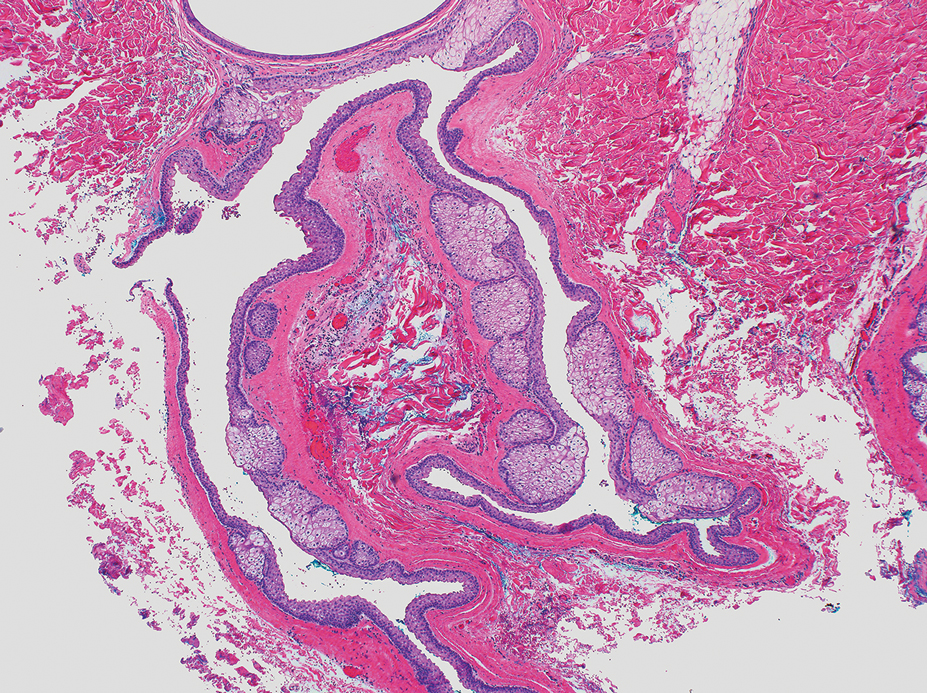

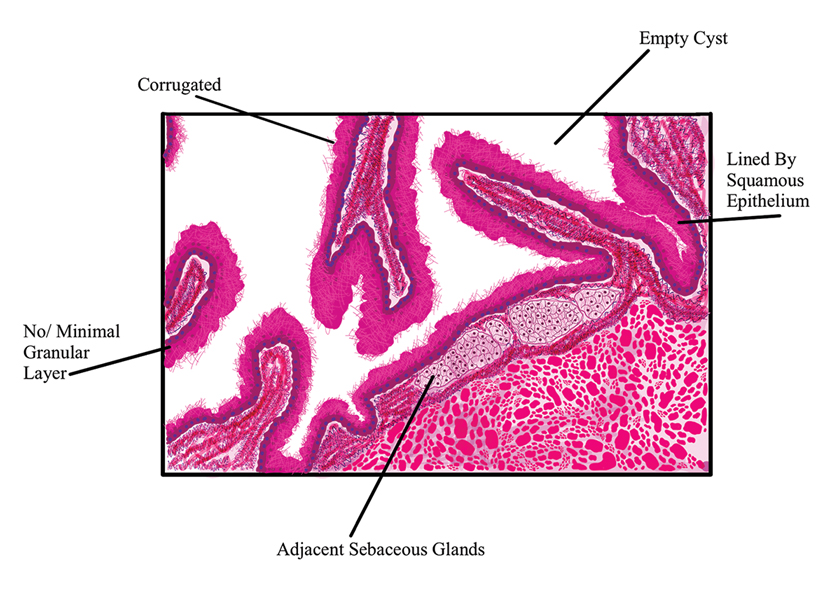

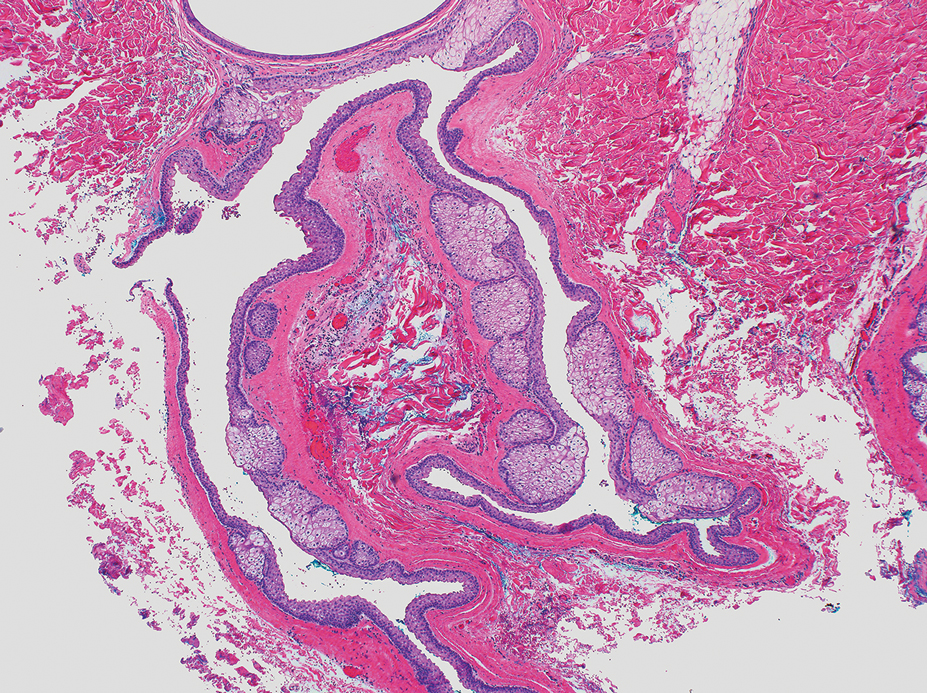

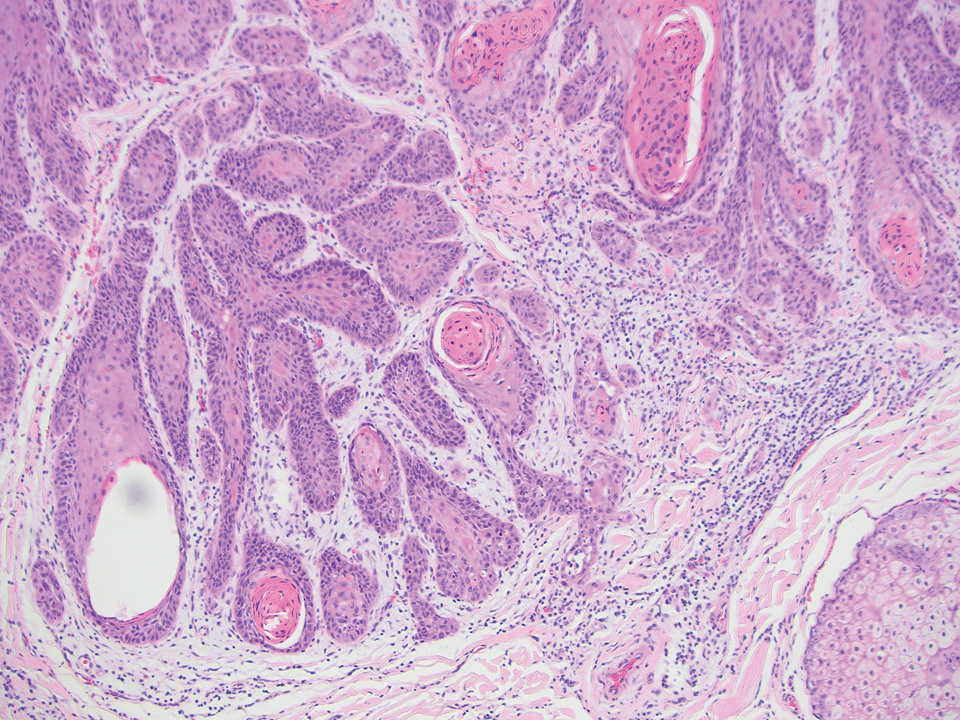

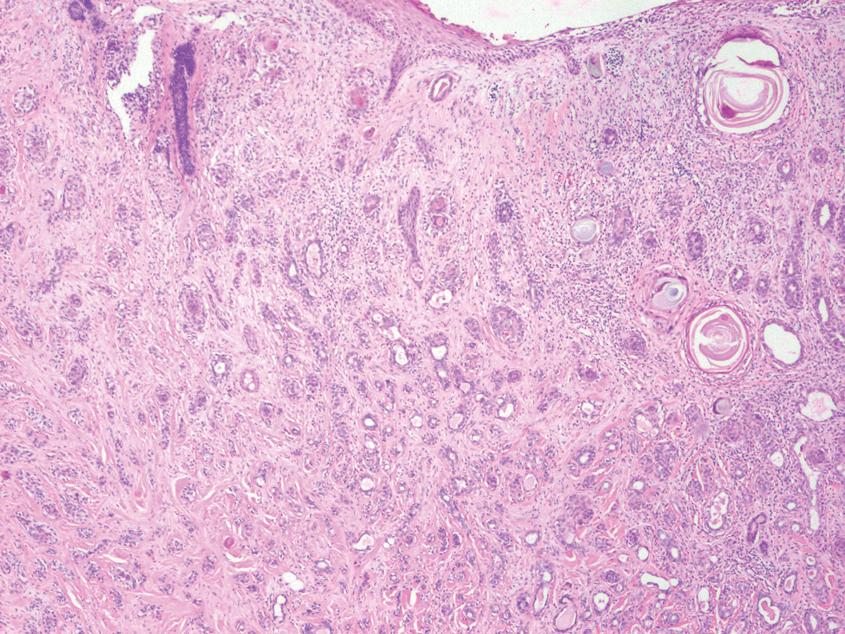

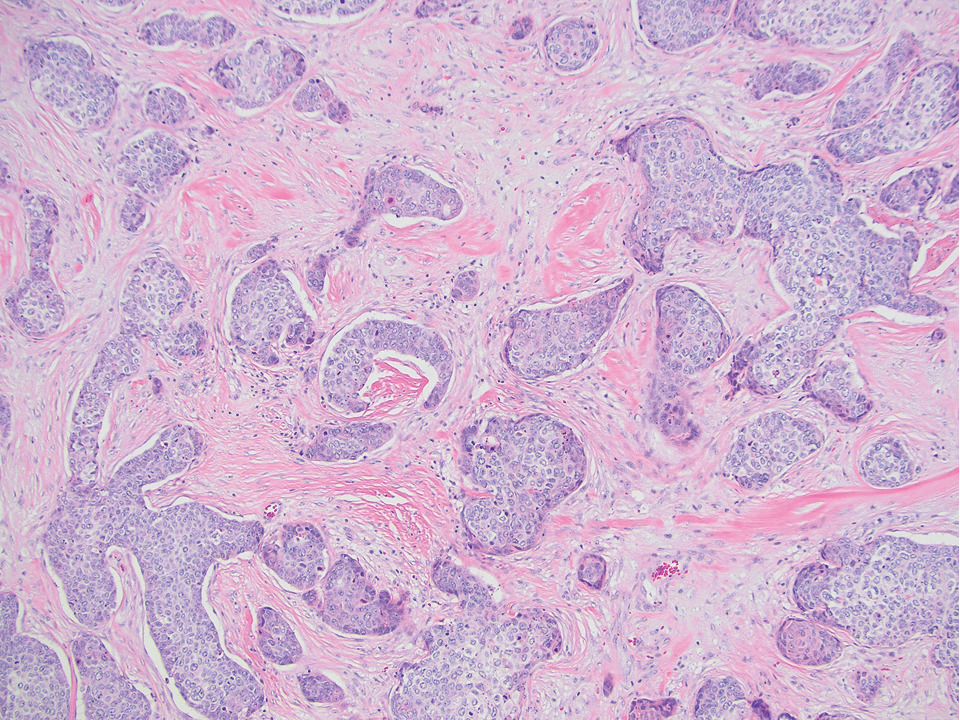

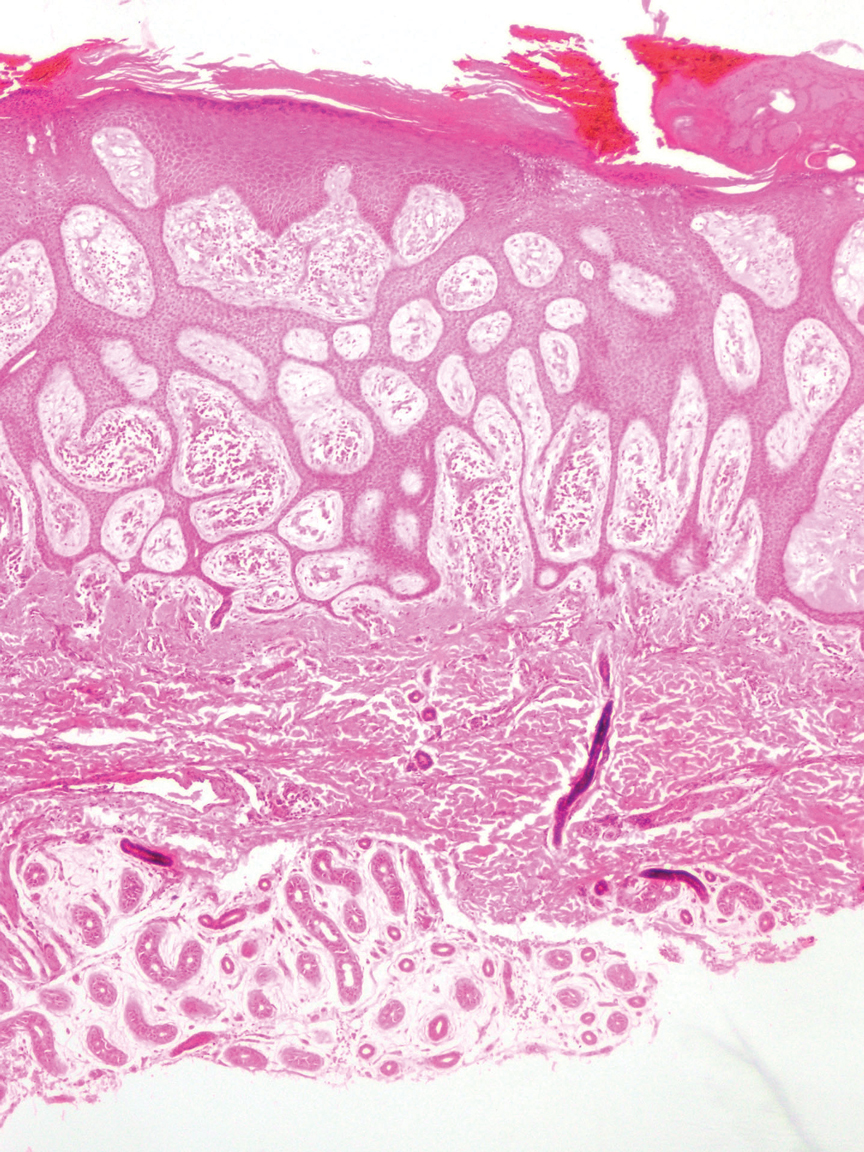

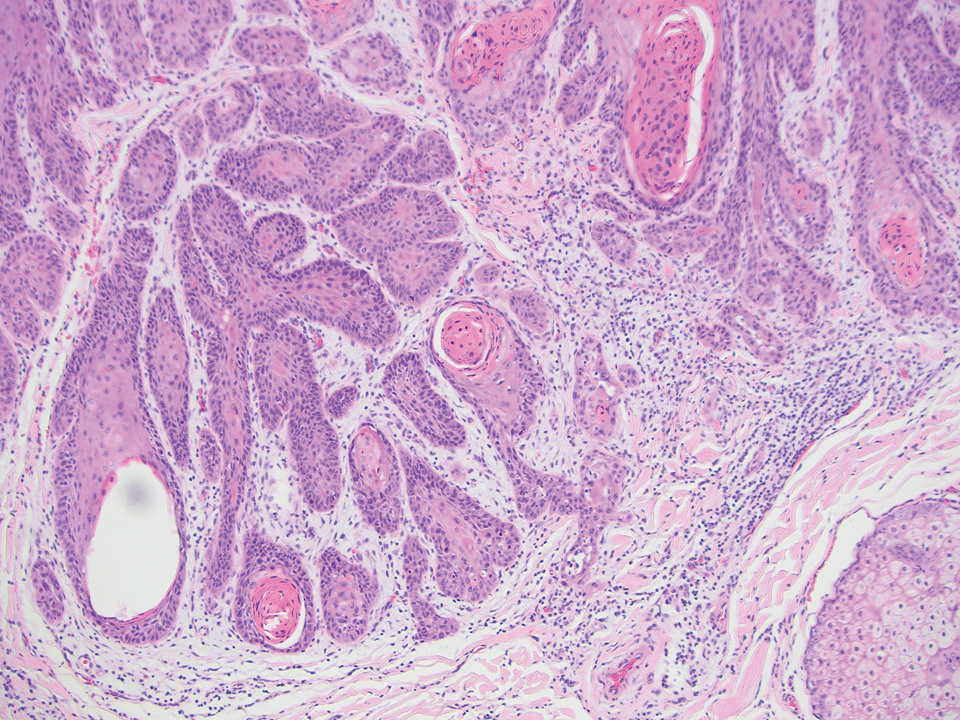

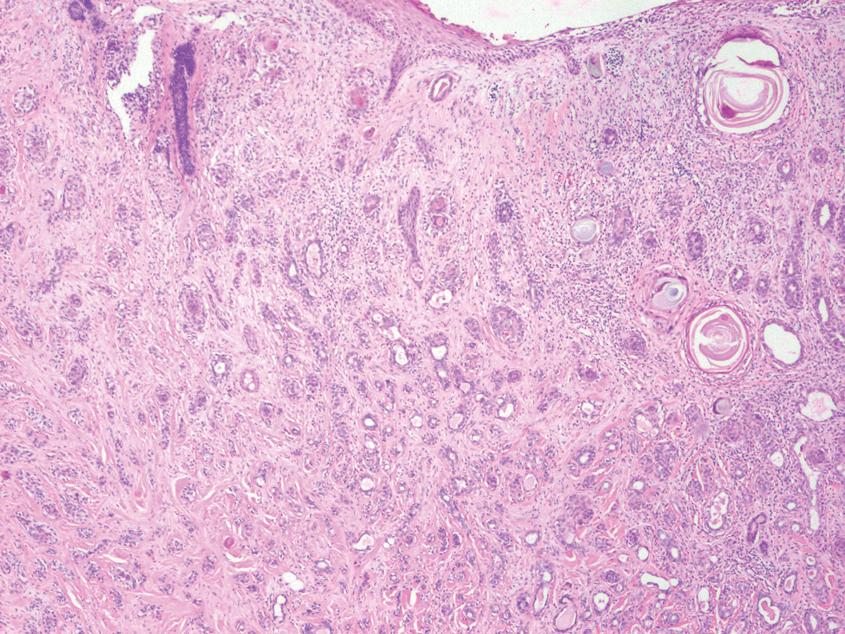

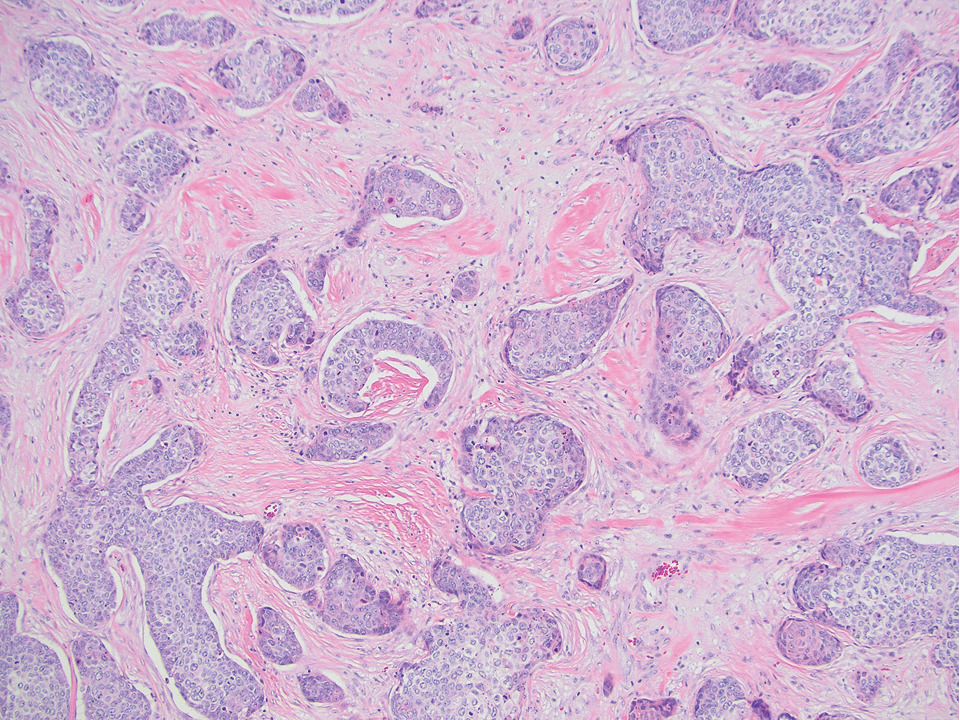

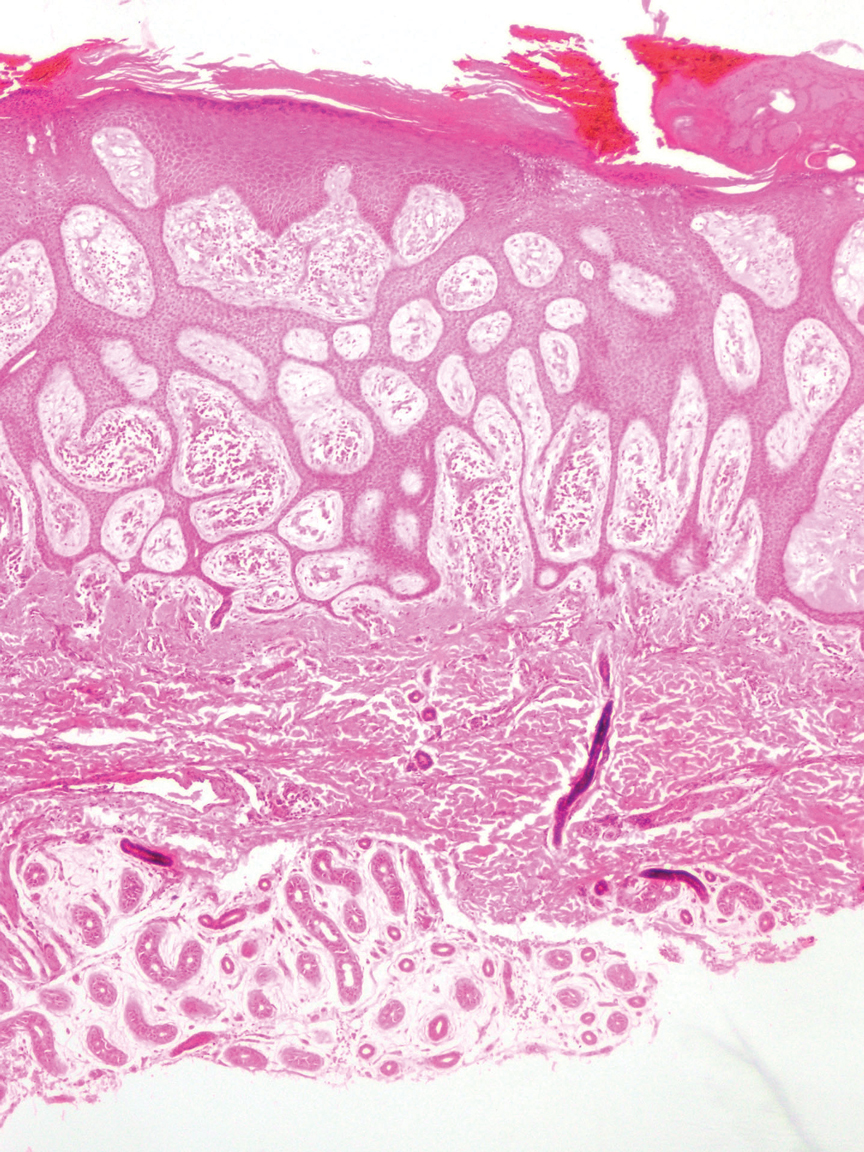

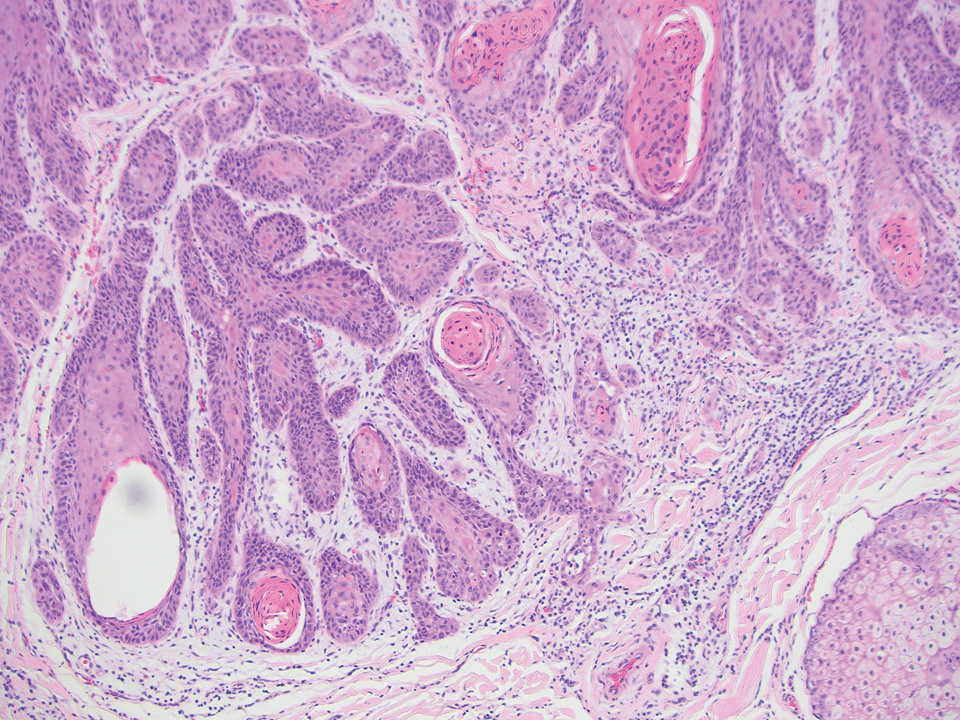

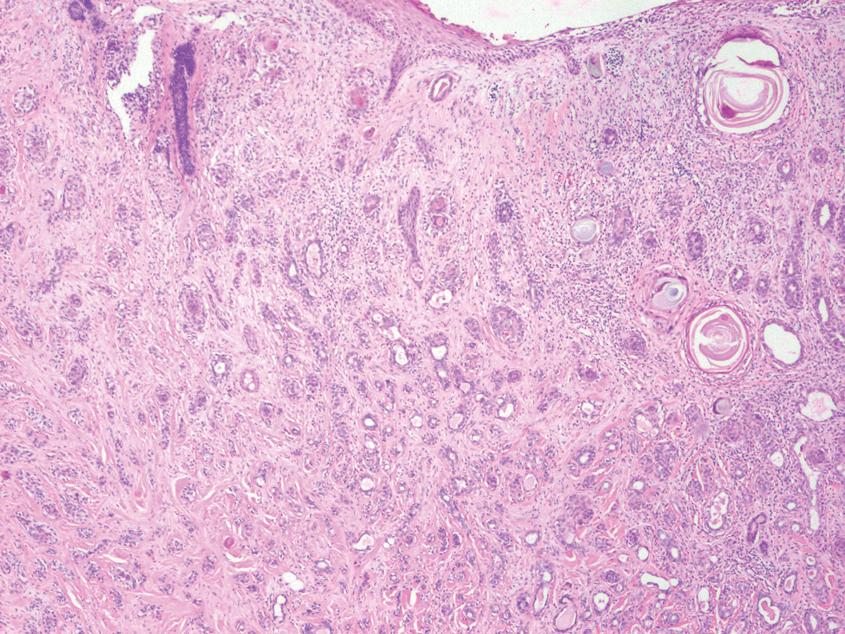

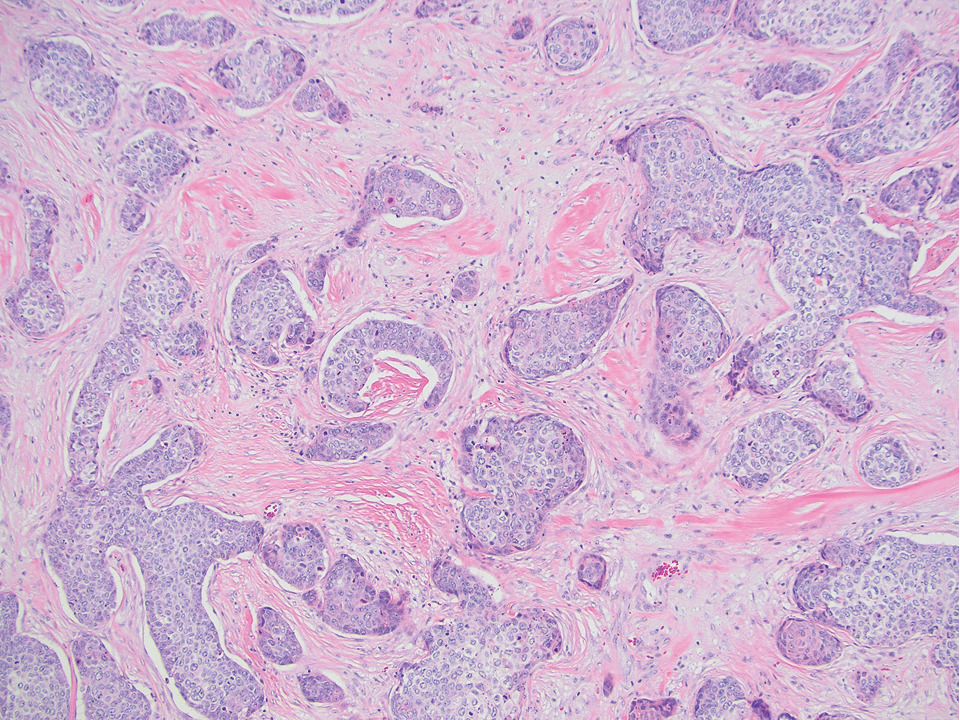

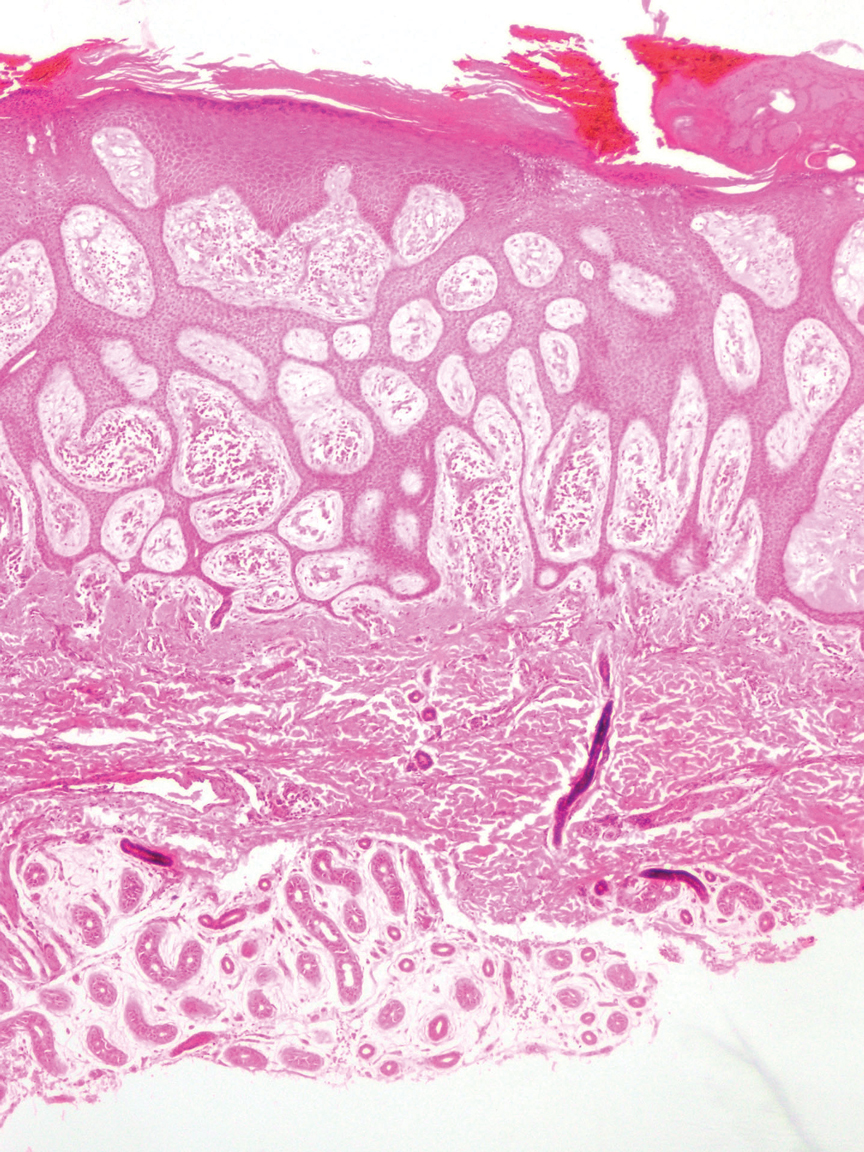

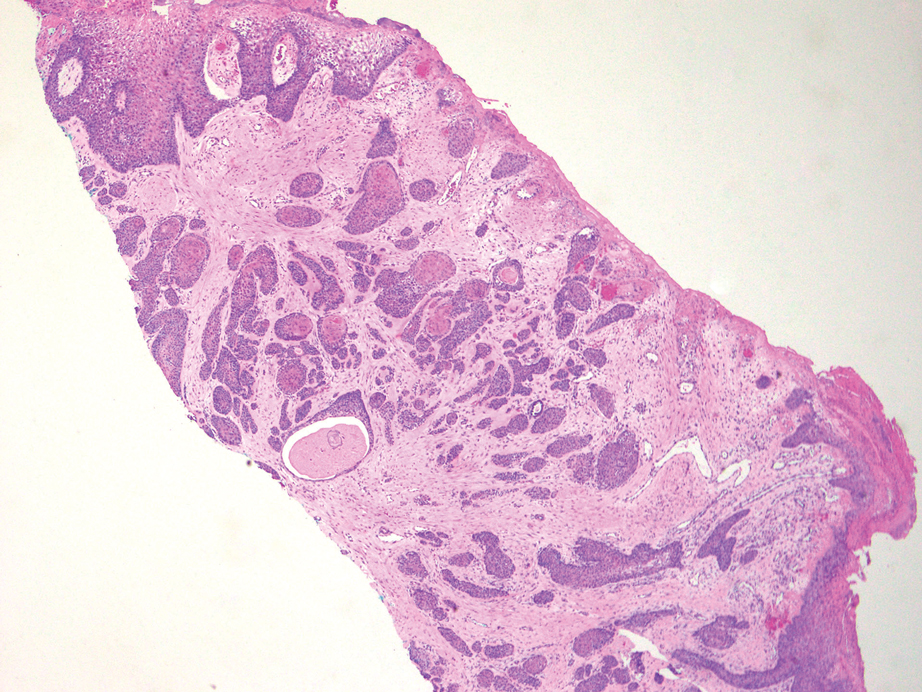

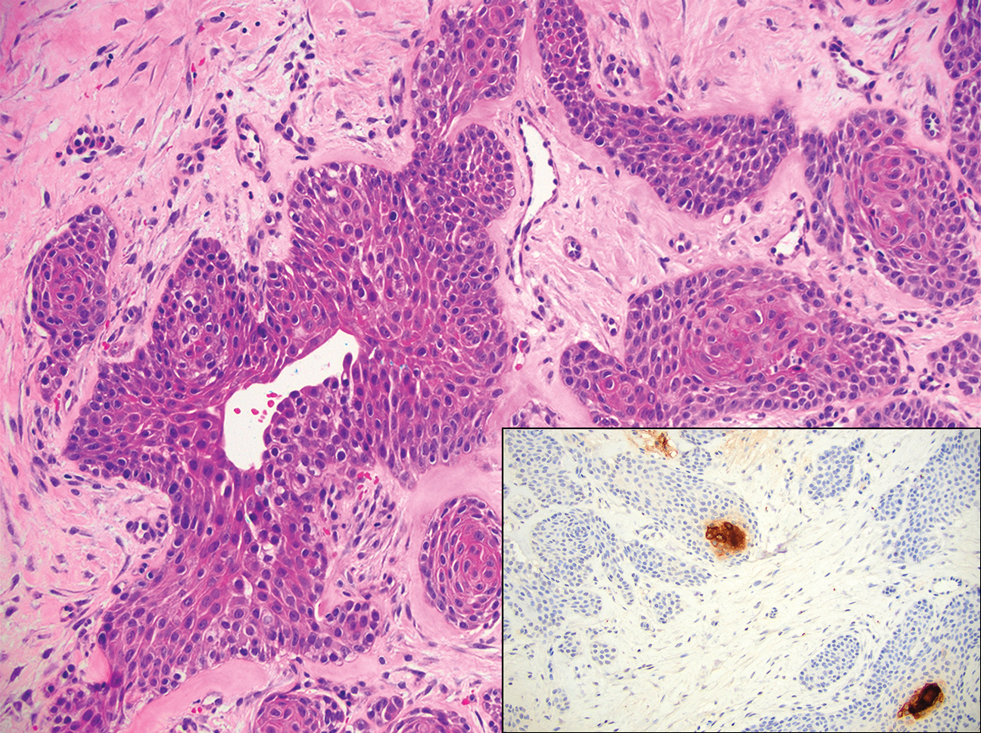

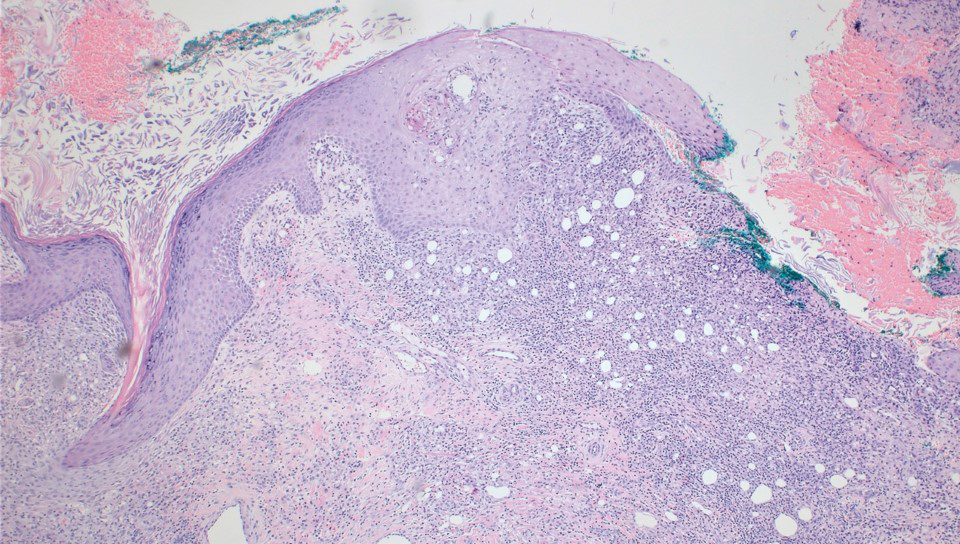

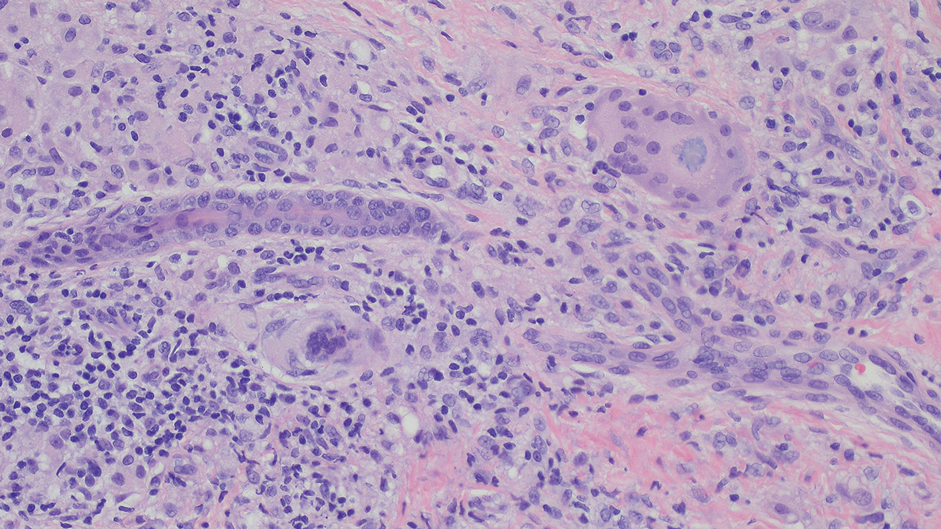

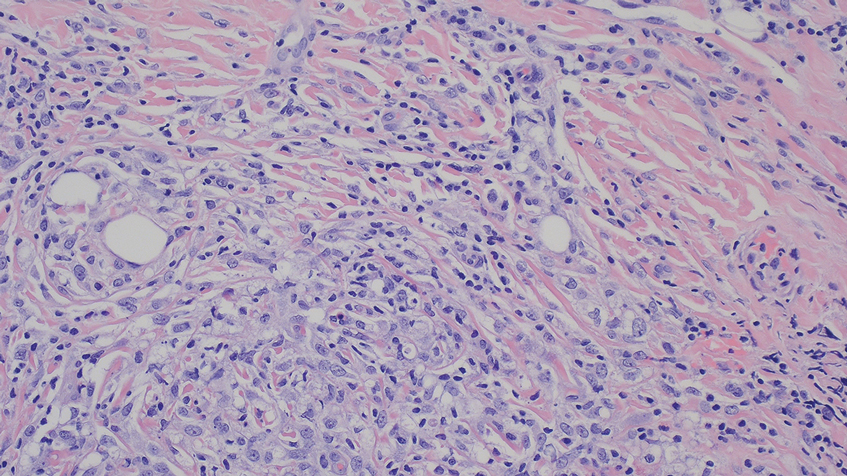

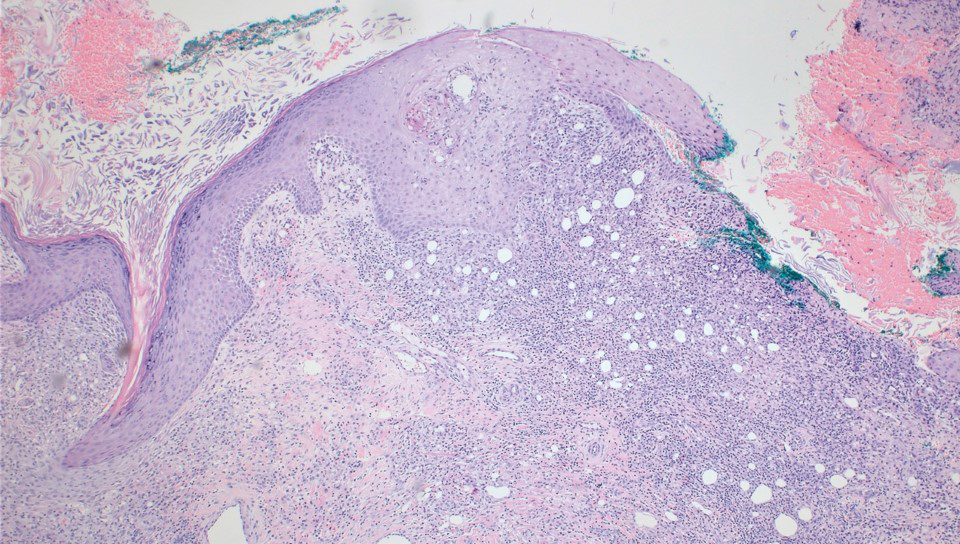

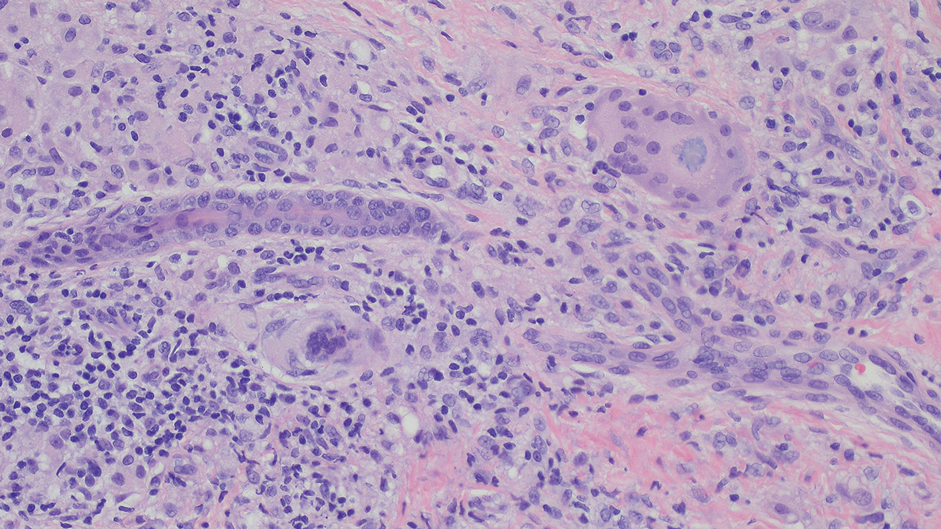

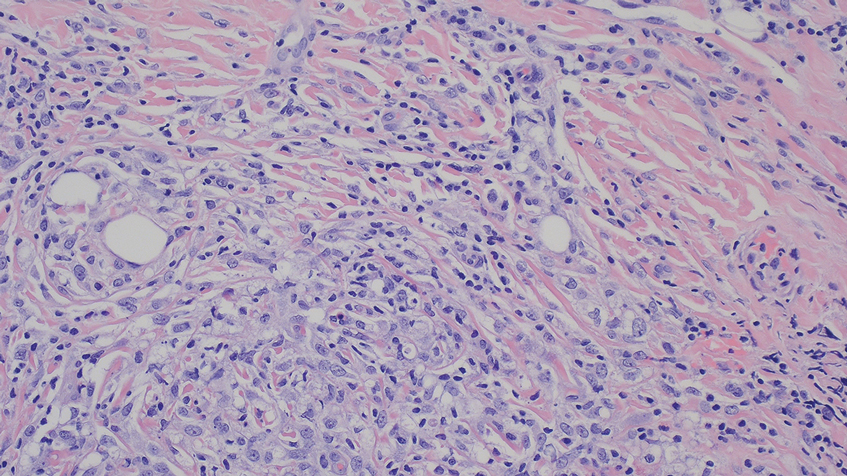

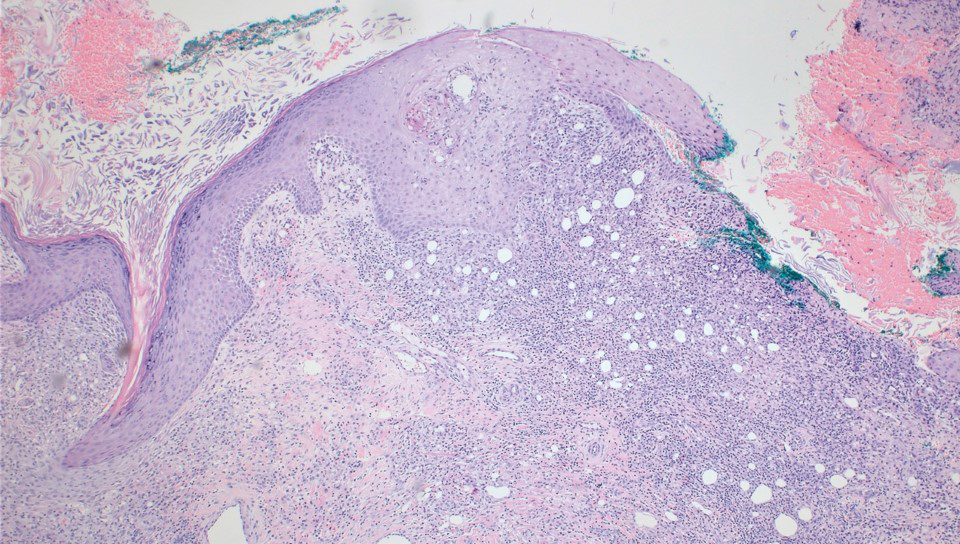

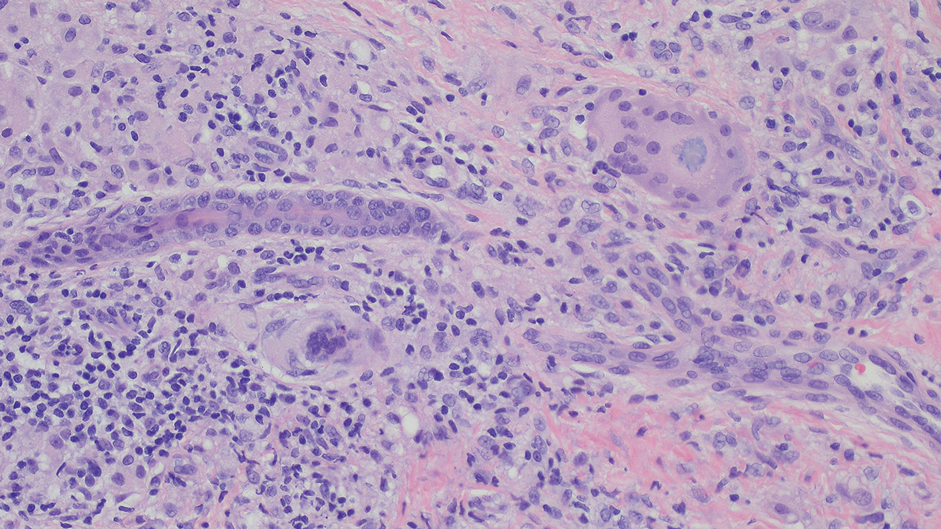

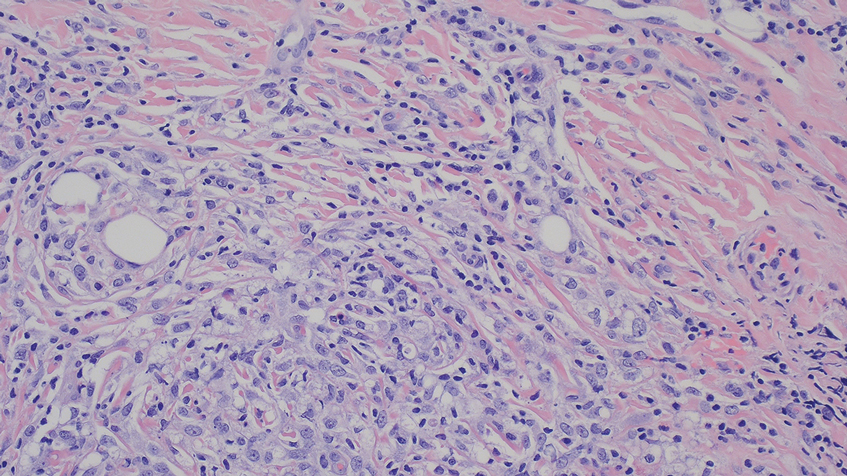

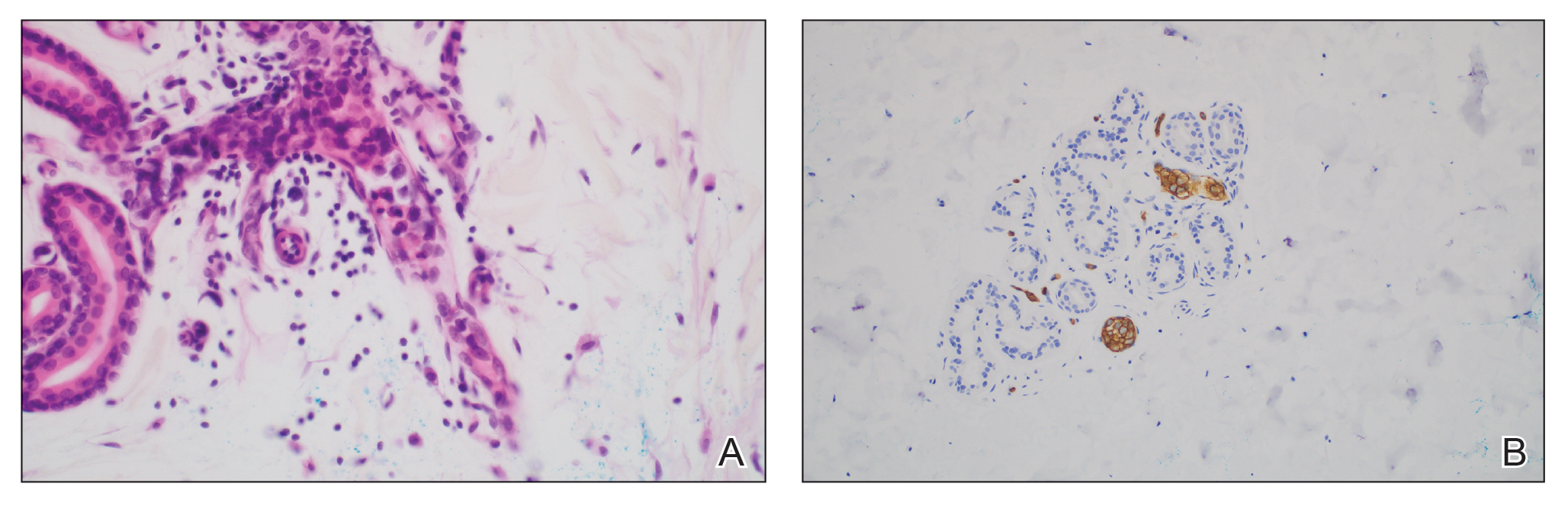

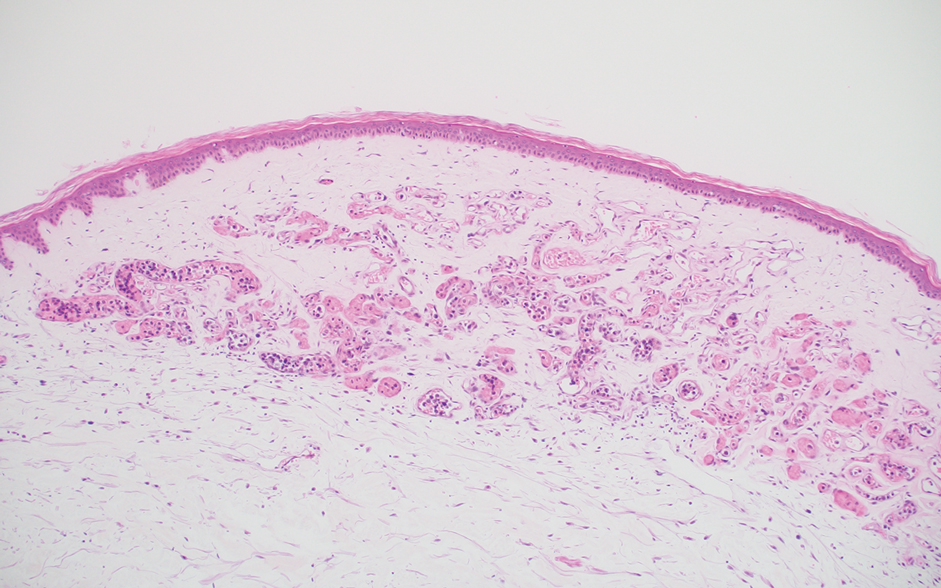

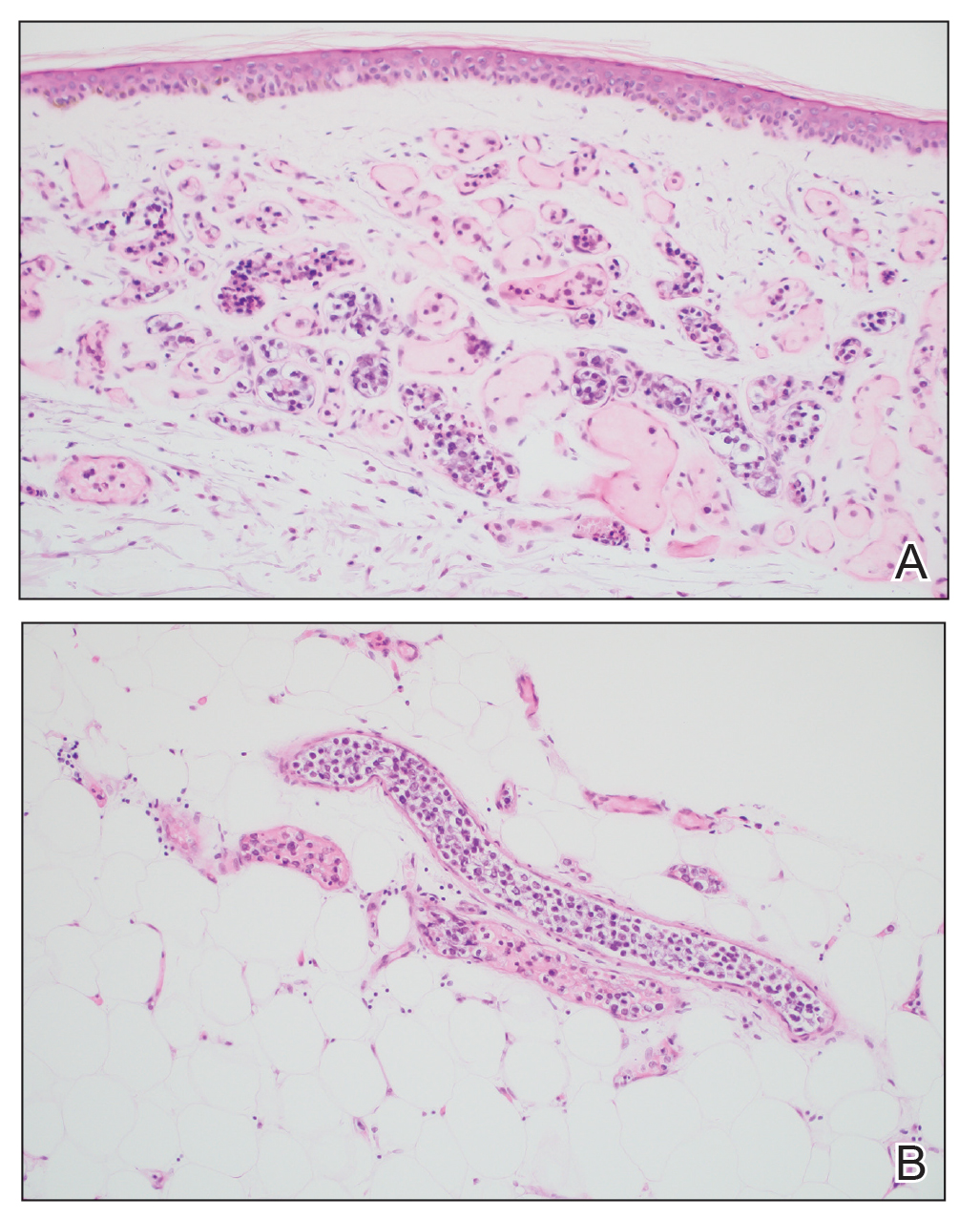

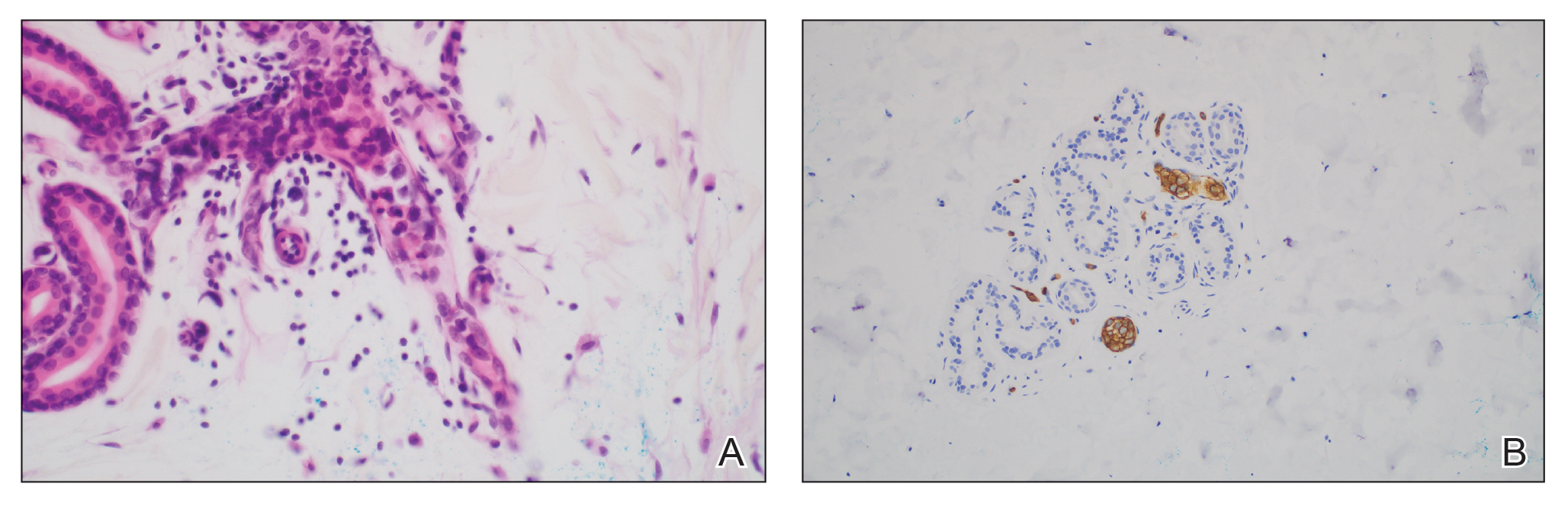

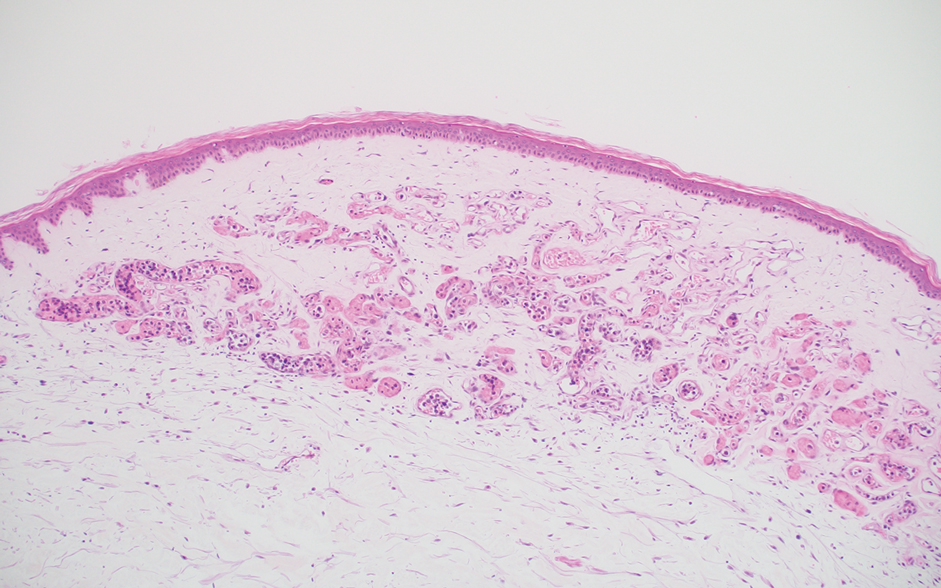

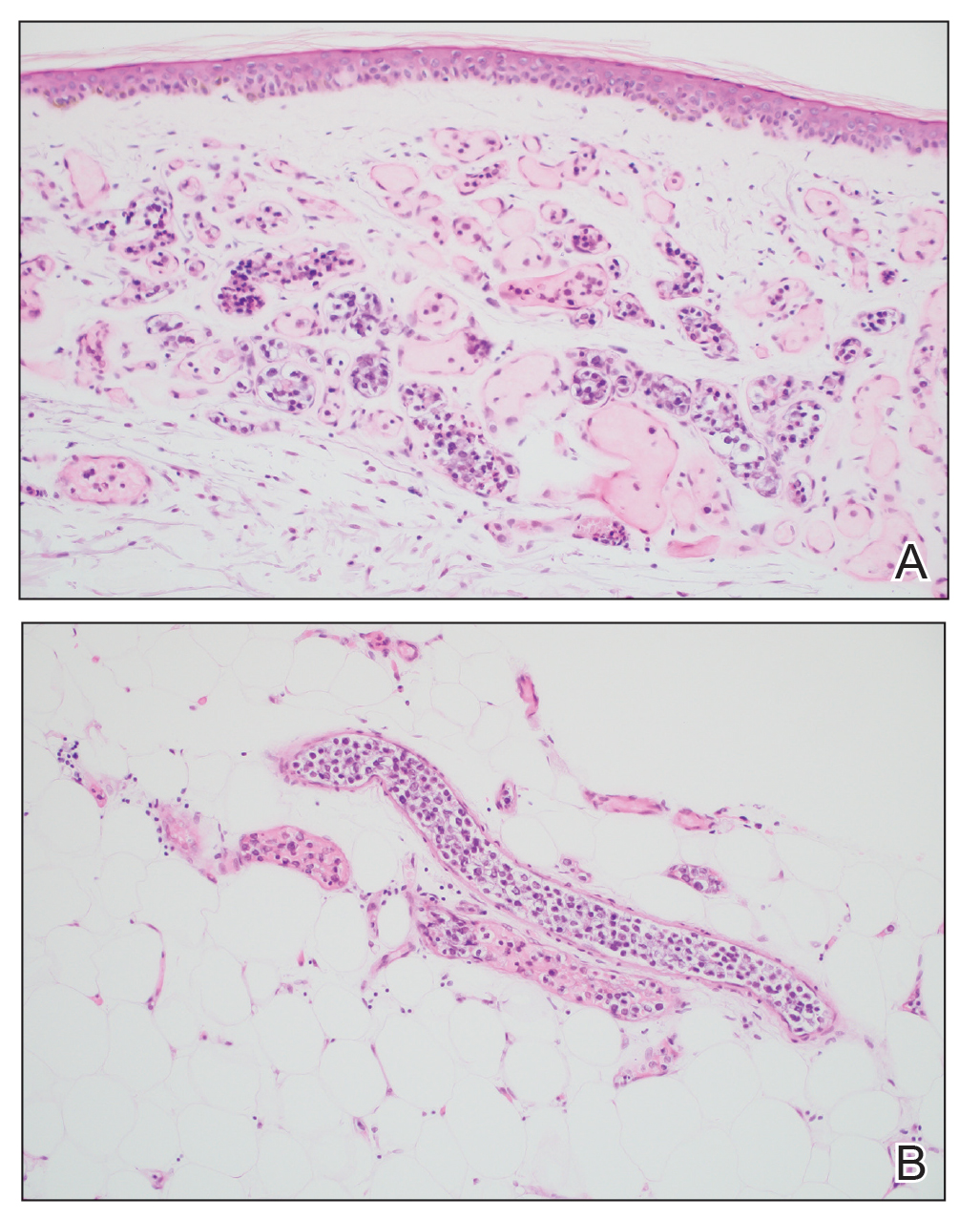

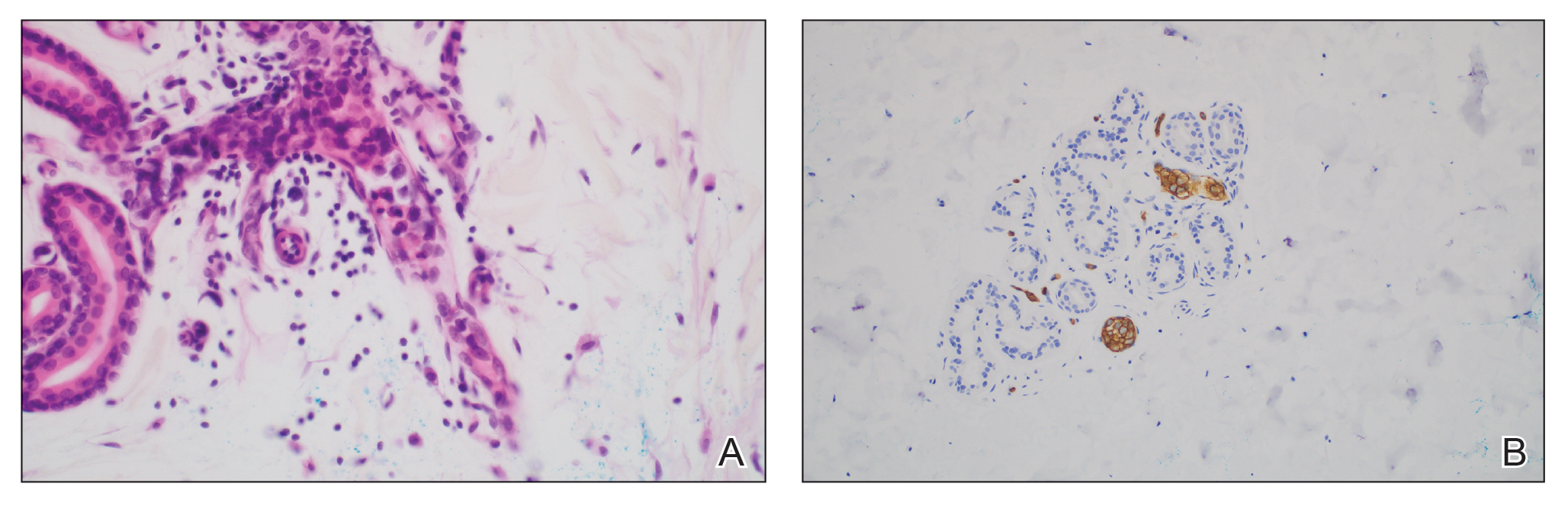

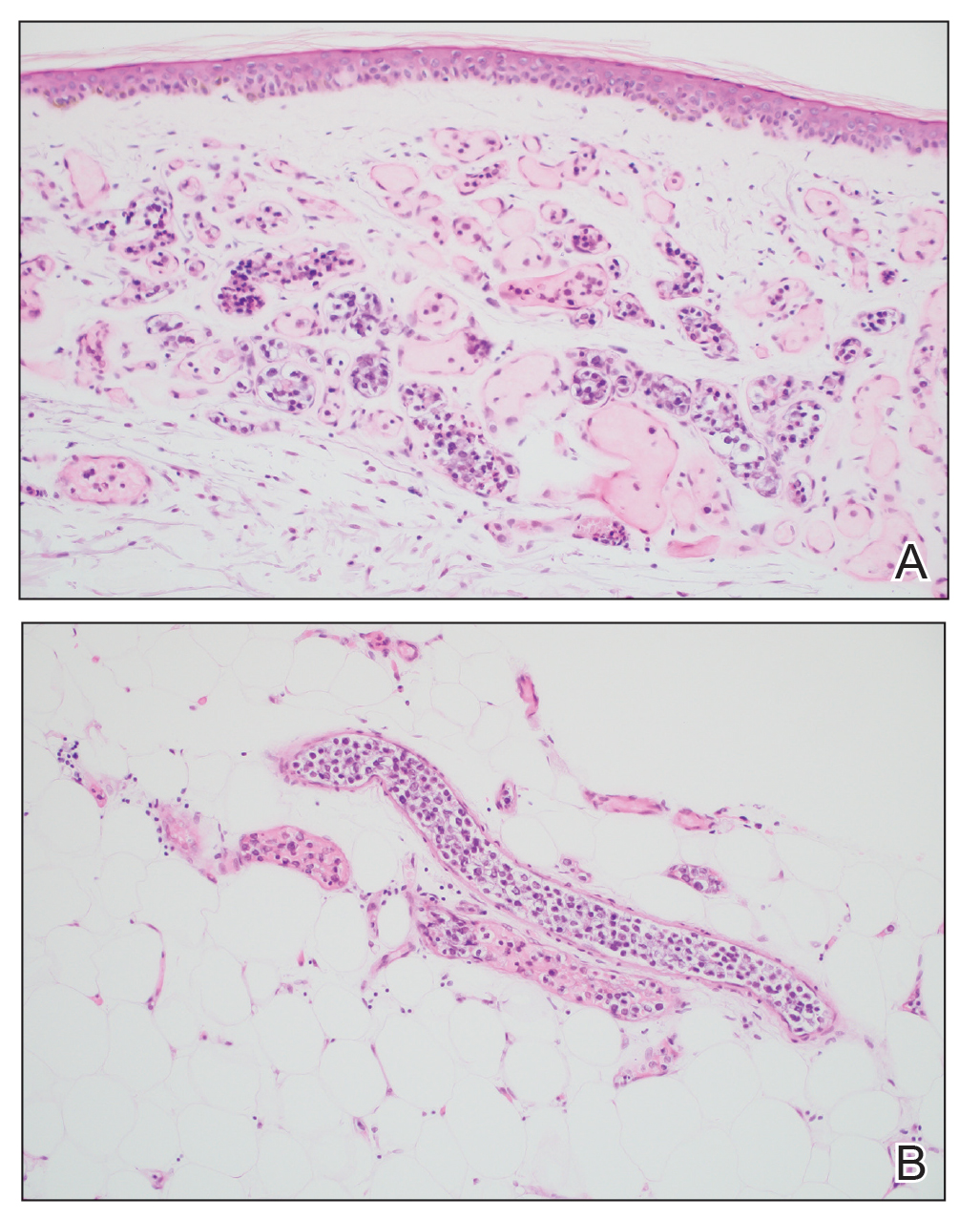

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

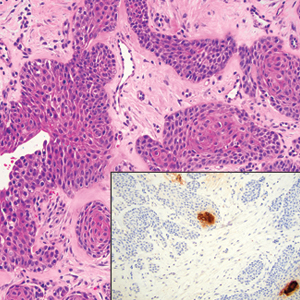

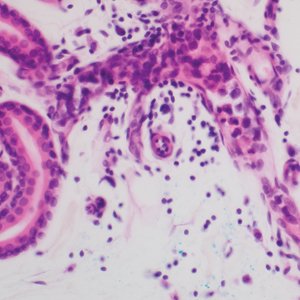

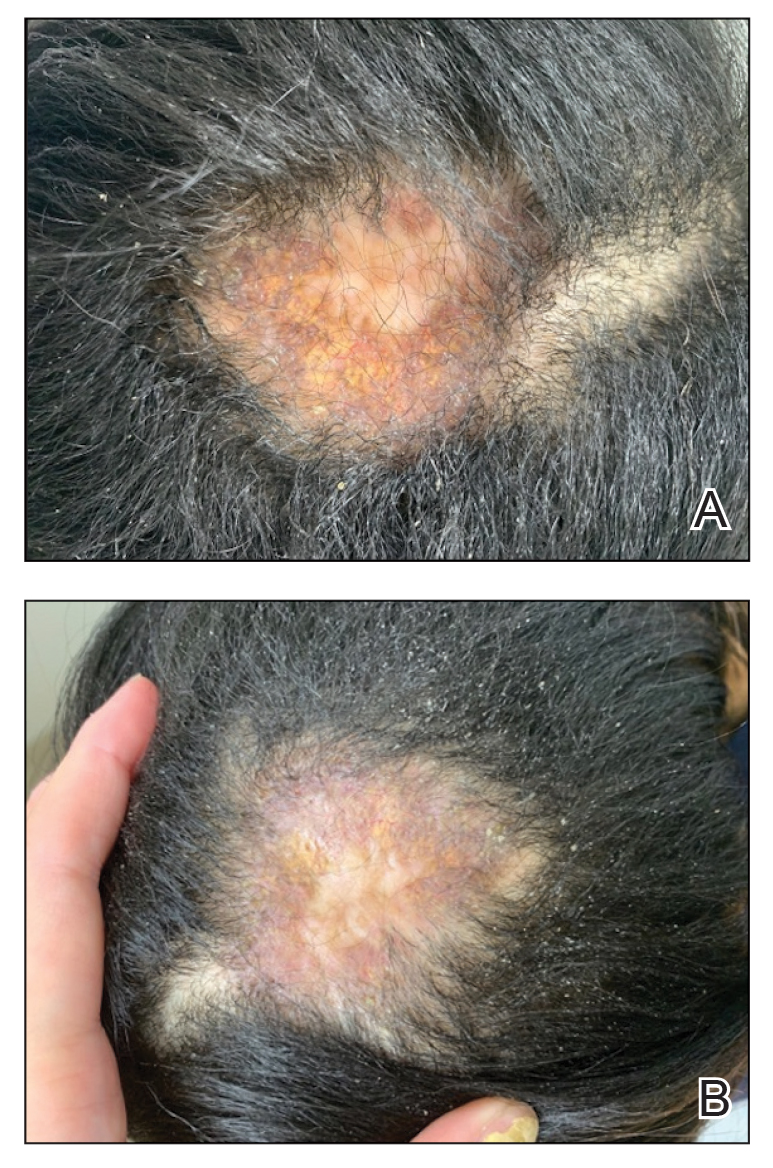

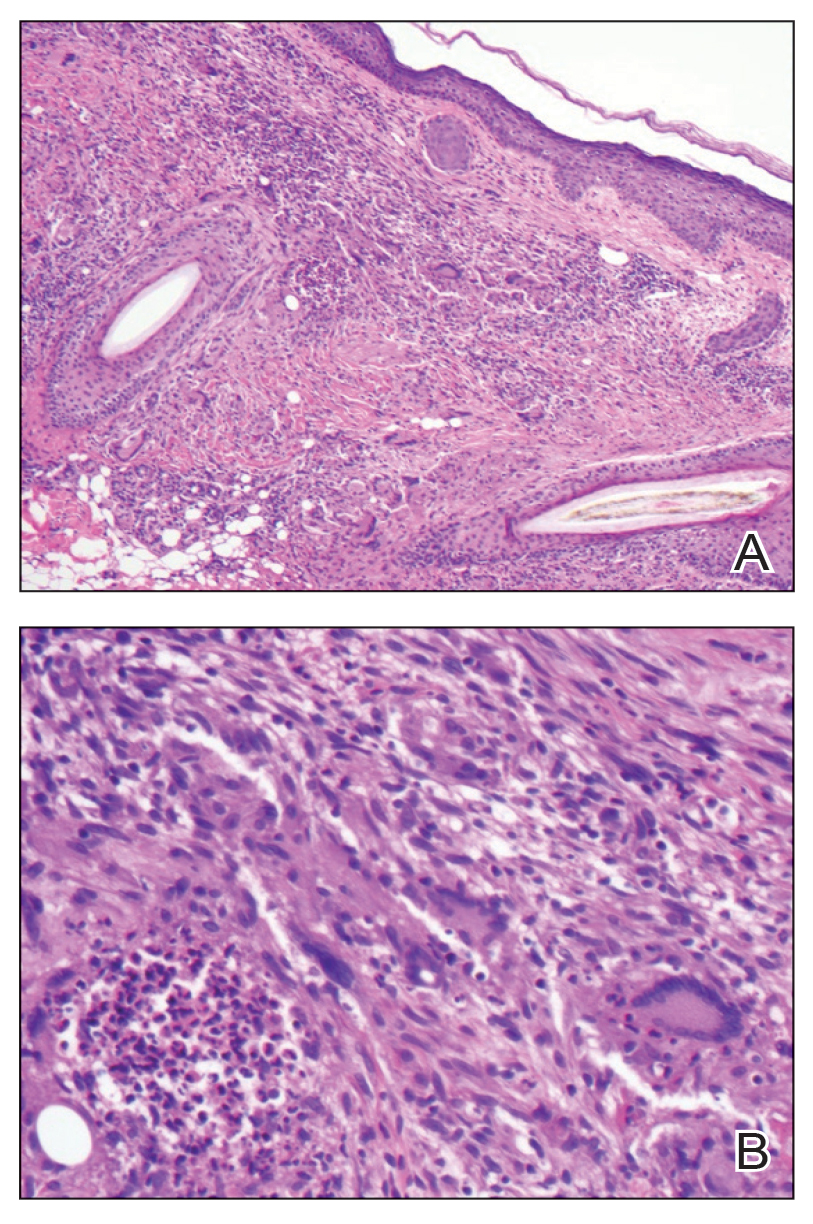

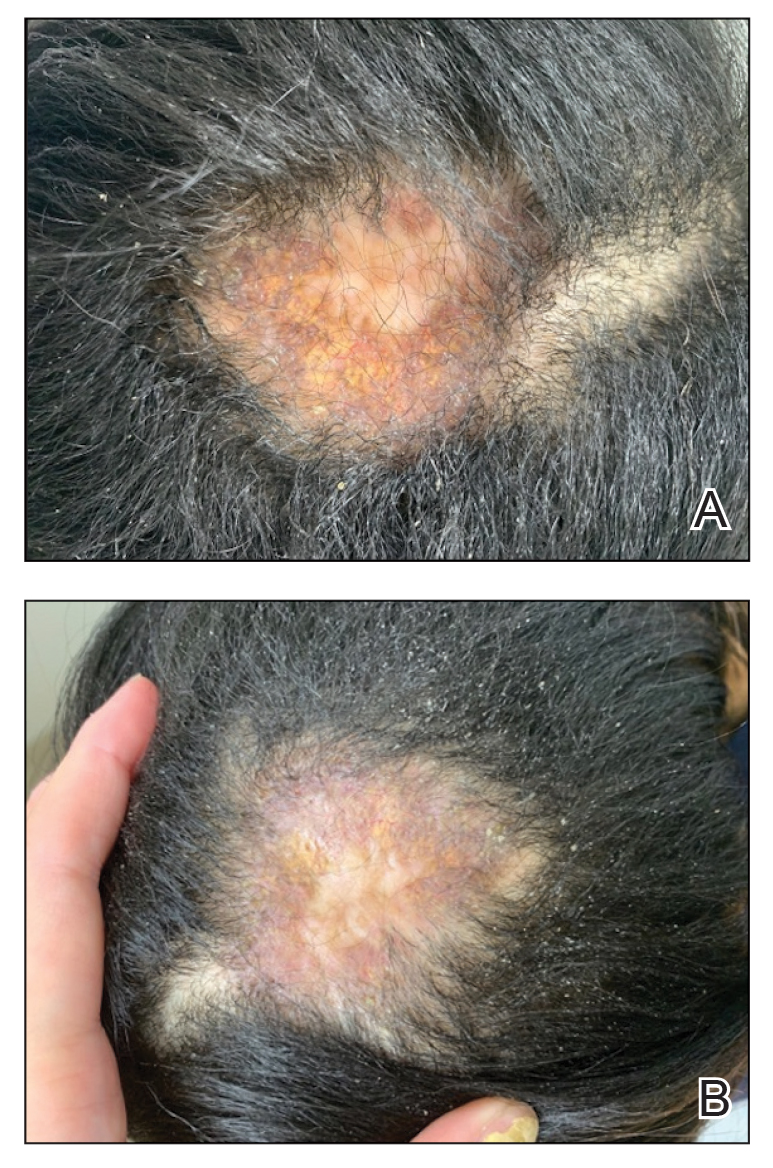

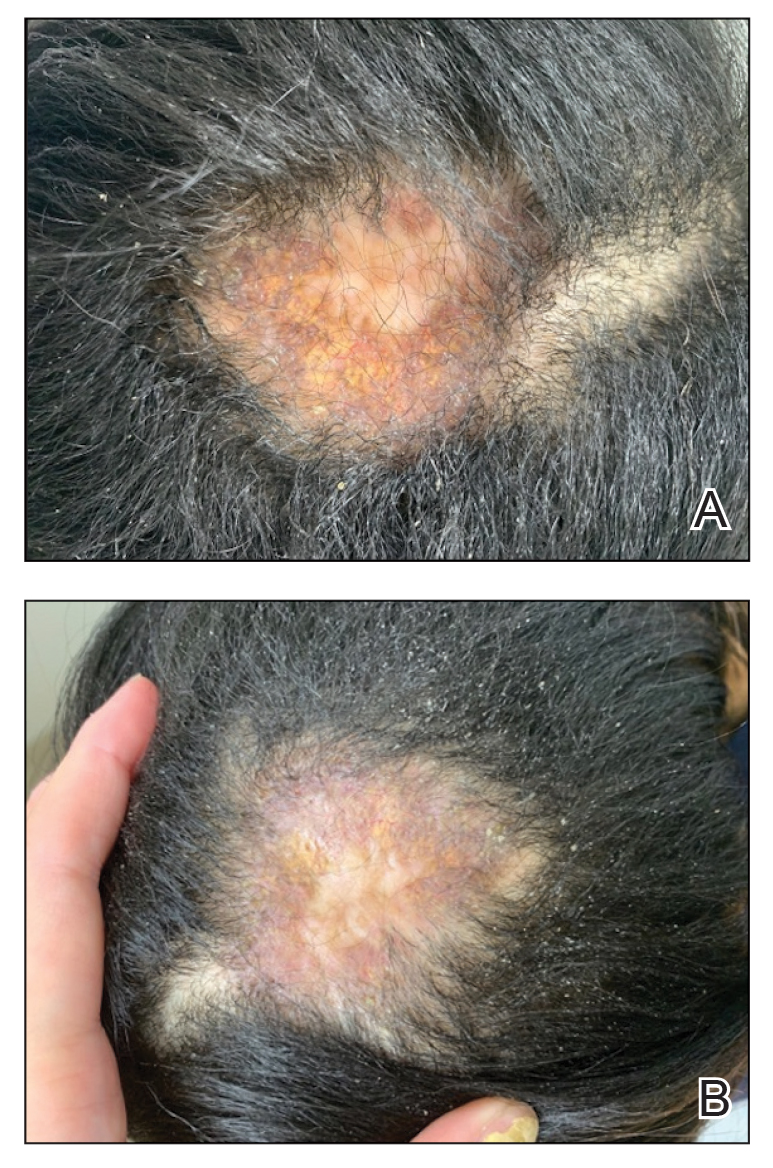

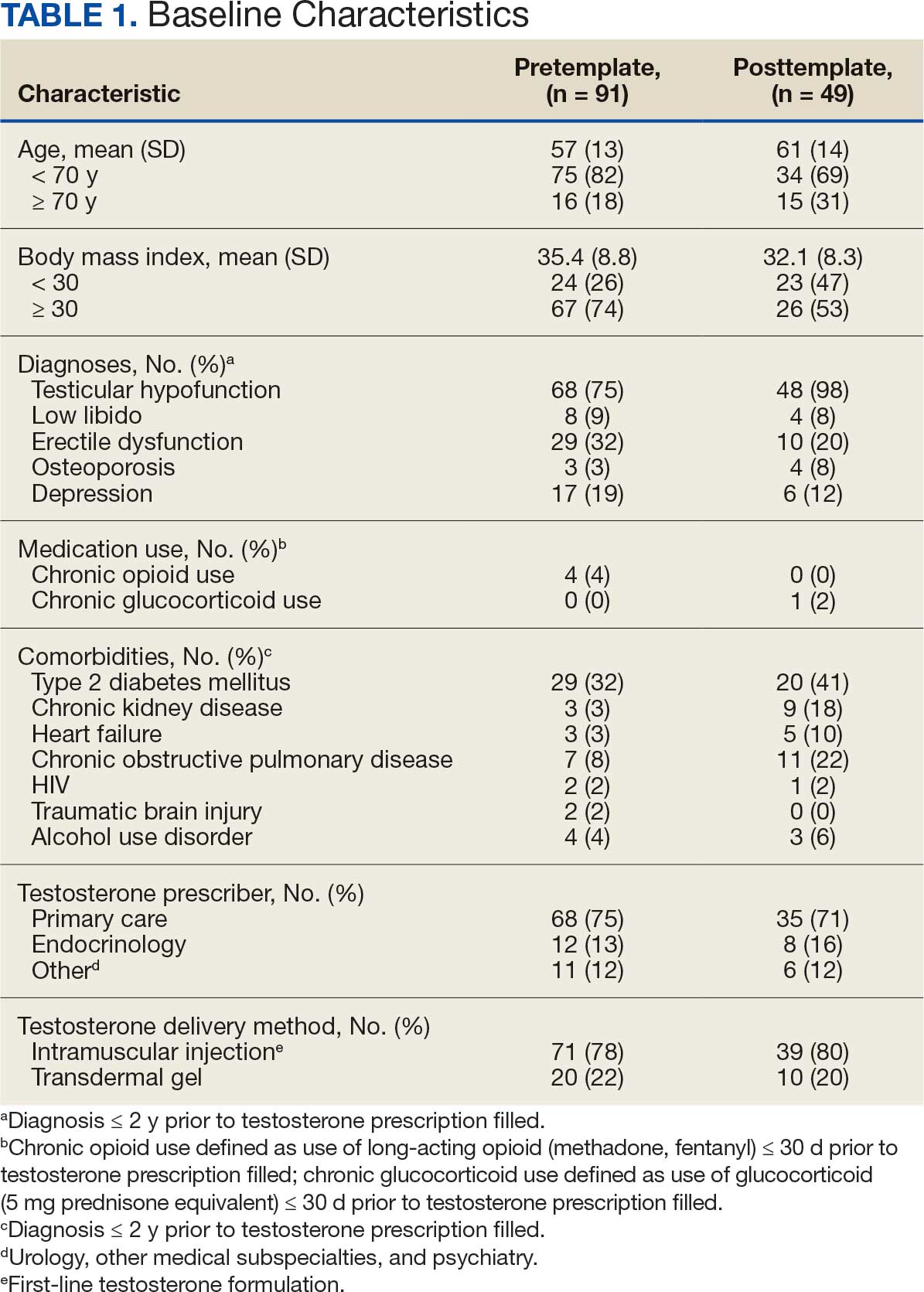

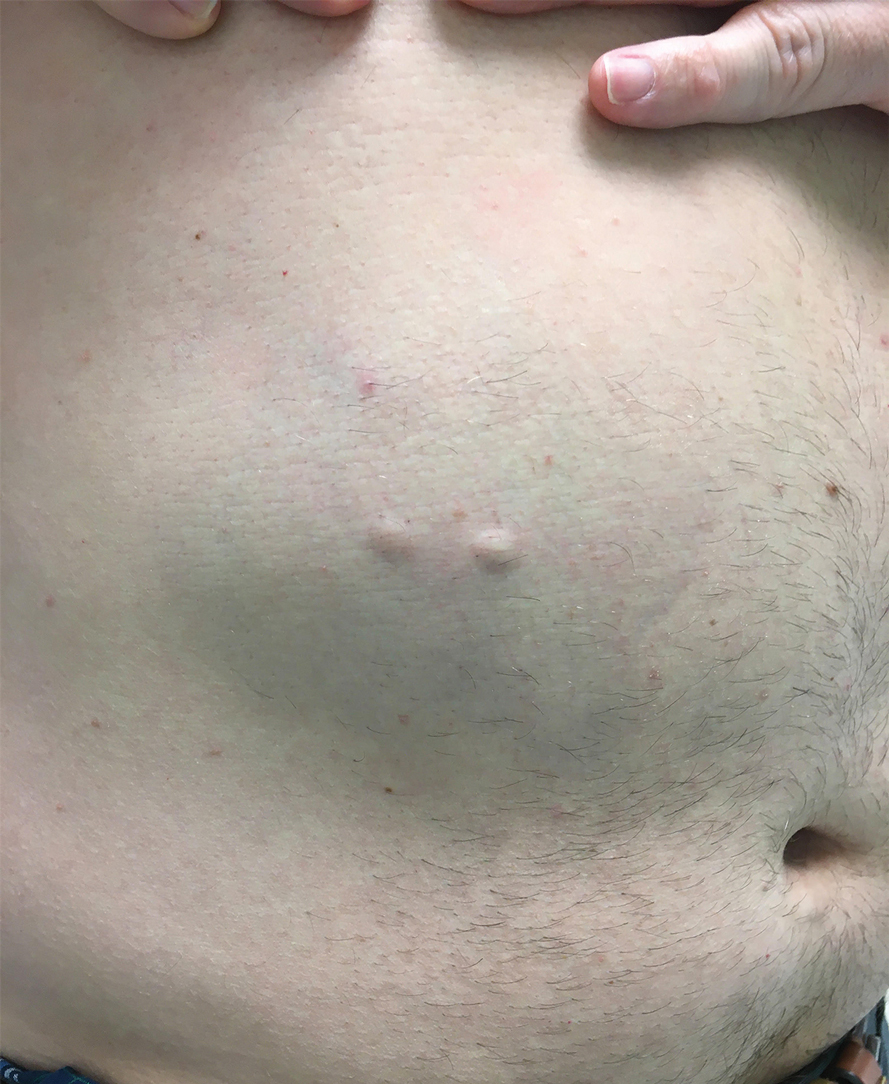

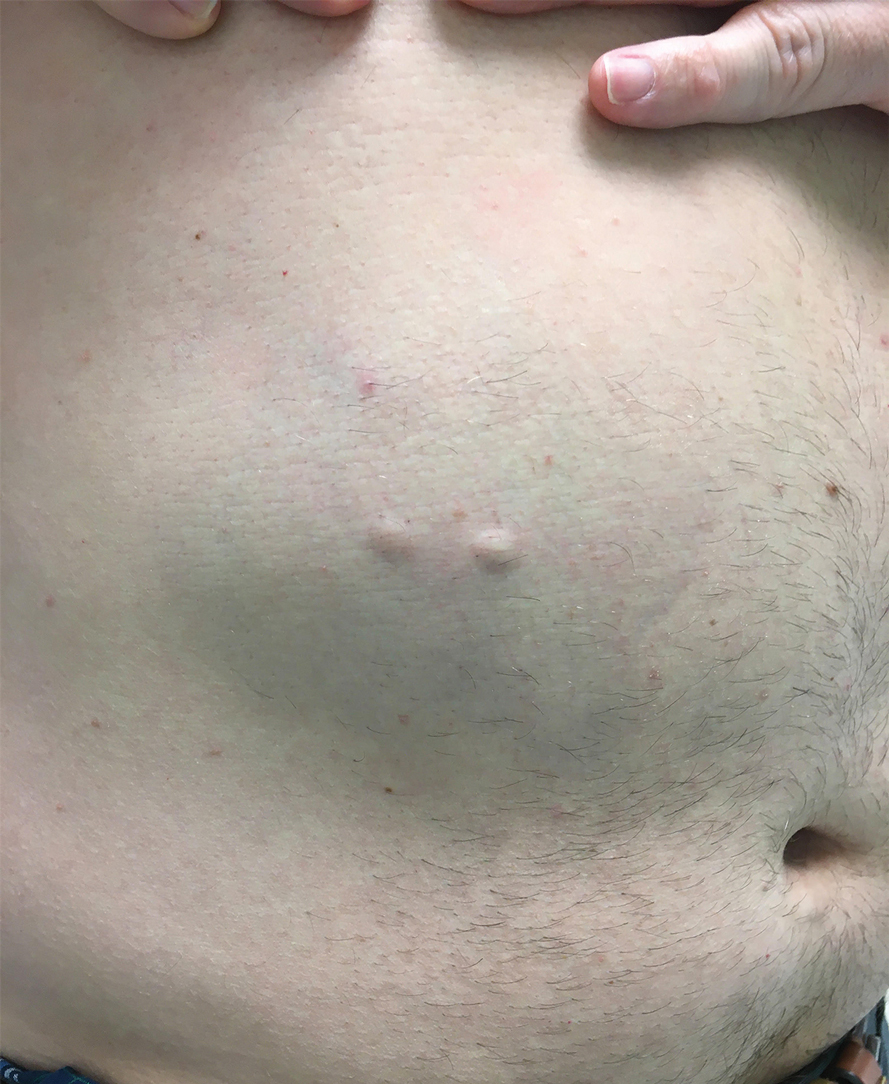

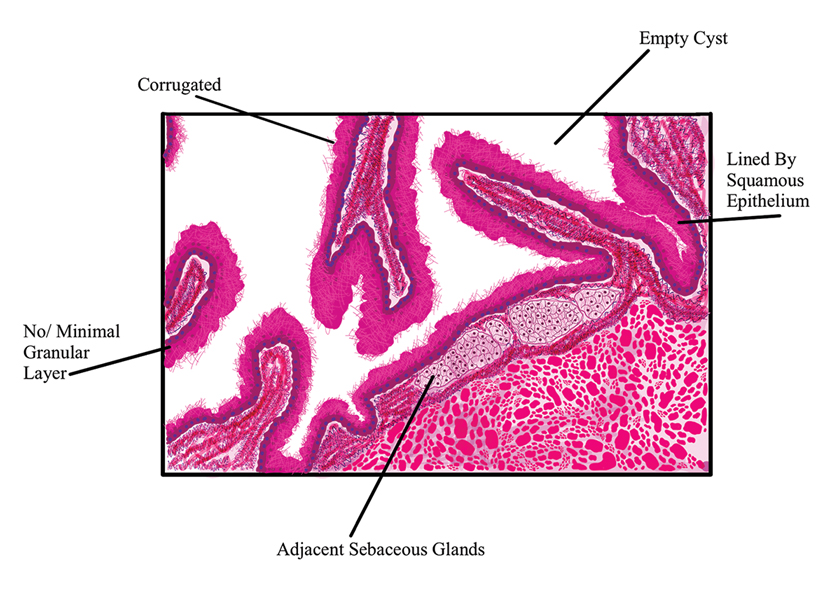

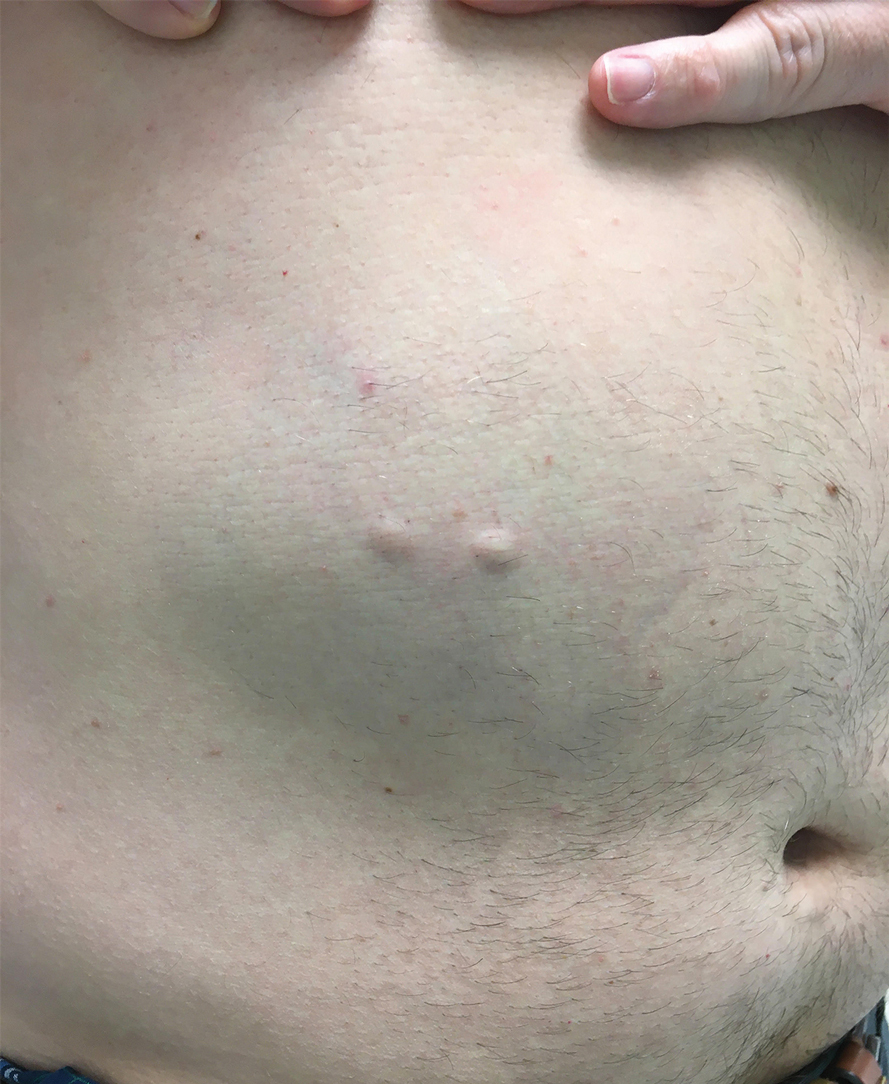

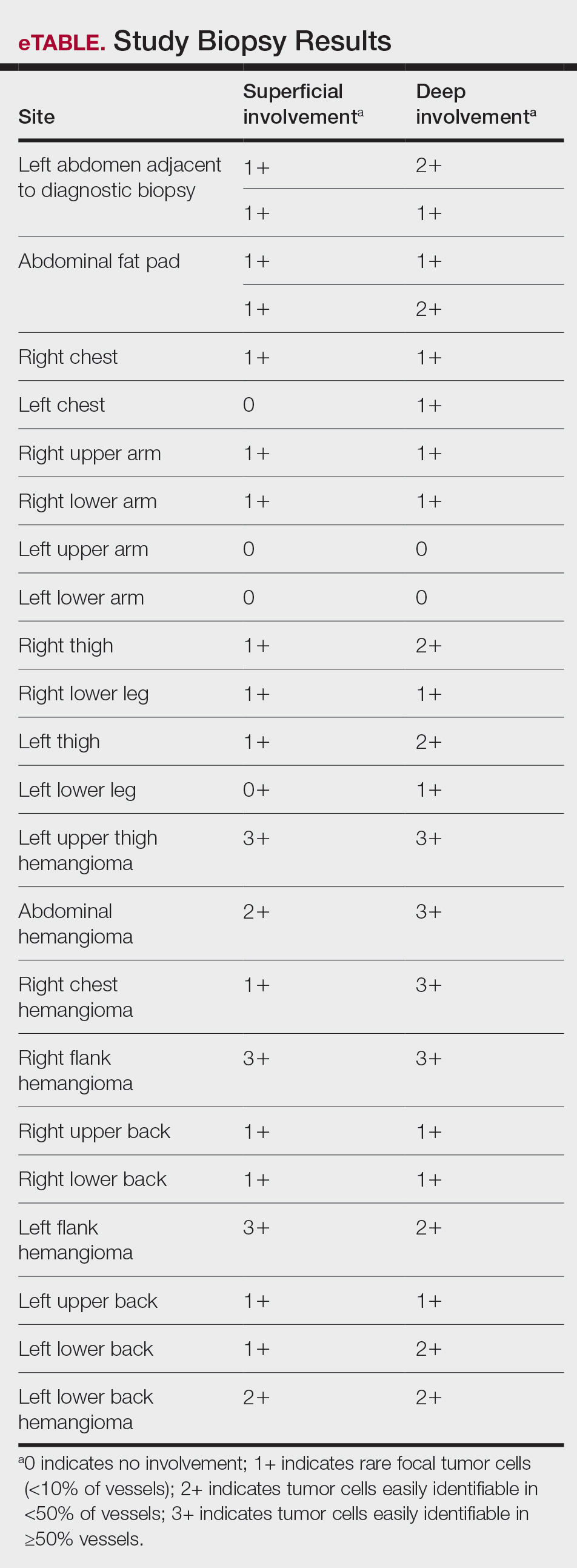

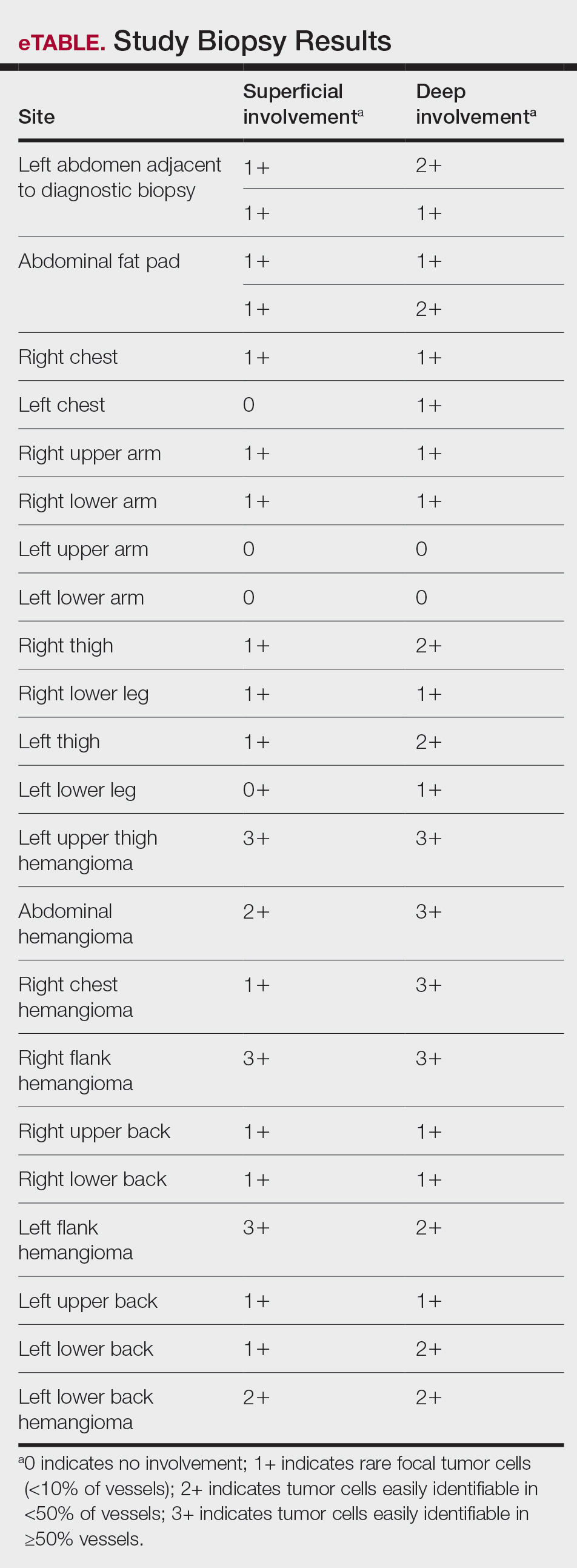

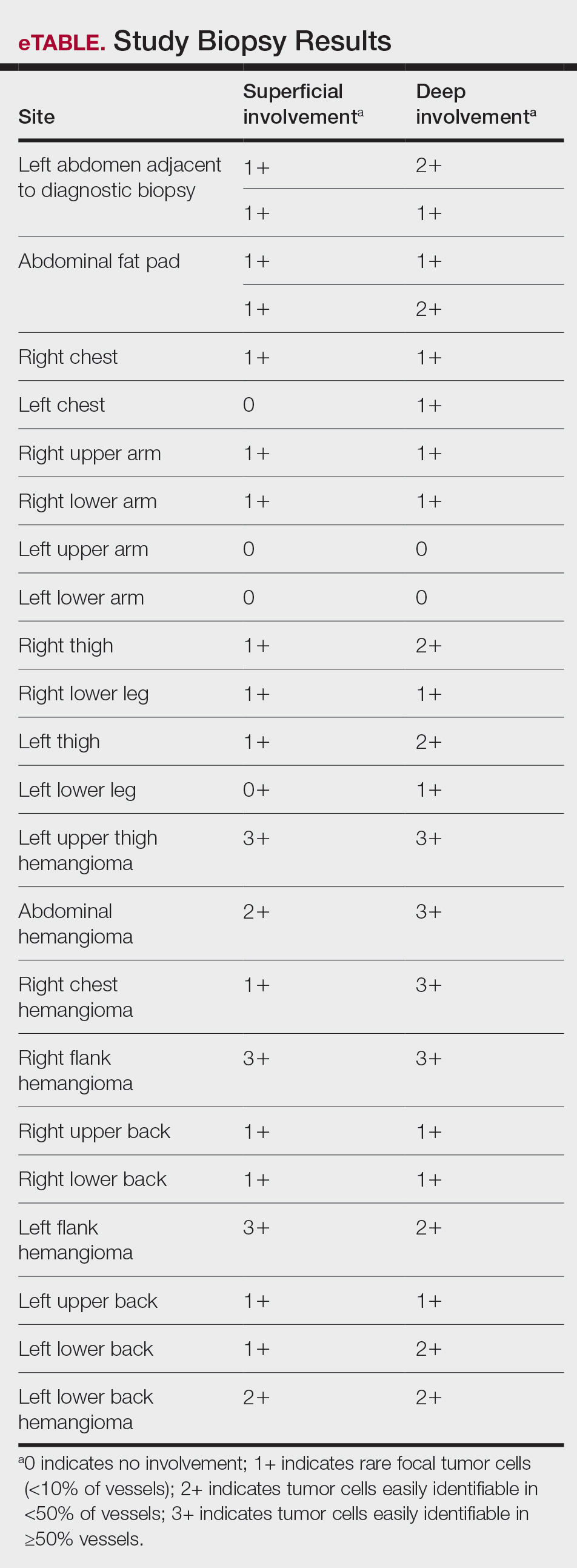

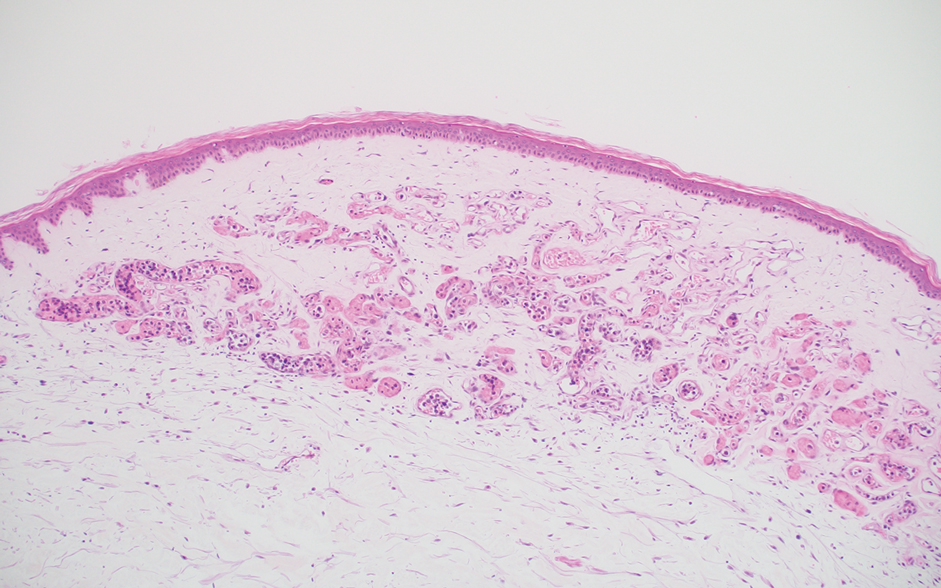

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

To the Editor:

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG) is classified as a cutaneous non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis, often seen with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma.1 Clinically, it appears as a red or yellow plaque with occasional ulceration and telangiectasias, most commonly seen periorbitally and on the trunk. On pathology, NXG appears as necrobiosis, giant cells, and various inflammatory cells extending into the subcutaneous tissue.2 In this article, we describe a rare presentation of NXG in location and skin type.

A 52-year-old woman with a history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presented with alopecia and a tender lesion on the scalp of 5 years’ duration (Figure 1). The patient had no history of a similar lesion, and no other lesions were present. A biopsy performed at an outside clinic a few weeks to months prior to the initial presentation to our clinic showed NXG (Figure 2). Evaluation at our clinic revealed a 4x4-cm orange-brown annular plaque on the left parietal scalp. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis studies were negative. The patient reported she was up to date with recommended screenings such as mammography and colonoscopy.

We started the patient on topical triamcinolone and topical ruxolitinib and administered intralesional triamcinolone. She was already taking hydroxychloroquine and leflunomide for SLE. Three weeks later, she returned with improved symptoms and appearance (Figure 1). She remained on intralesional triamcinolone and ruxolitinib and continues to experience improvement.

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is rare and typically is associated with monoclonal gammopathy.2 In one study, 83 of 100 of patients with NXG presented with or were found to have a monoclonal gammopathy.2 In another study, paraproteinemia was detected in 82.1% of patients.3 The majority of case reports and systematic reviews detail periorbital or thoracic lesions.4 The location on the scalp and lack of association with paraproteinemia make this a rare presentation of NXG. Studies may be warranted to explore any association of SLE with NXG if more cases present.

In a multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of 235 patients with NXG, 87% were White, 12% were Asian, and only 1% were Black or African American.3 The limited representation of skin of color raises concern for the possibility of missed diagnoses and delays in care.

Treatment of NXG often is multimodal with use of intravenous immunoglobulin, oral steroids, chlorambucil, melphalan, and other alkylating agents, and response is variable.3-6 Recent studies show treatment effectiveness with Janus kinase inhibitors in granulomatous dermatitides.7-9 As our patient was not responding to prior treatments, we decided to try ruxolitinib, and she has continued to improve with it.10,11 Interestingly, the patient experienced continued improvement with intralesional triamcinolone, which is not often reported in the literature.2-6 Overall, NXG is an extremely rare condition that requires special care in workup to rule out paraproteinemia and a thoughtful approach to treatment modalities.

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

- Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, et al. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681.

- Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1-10.

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter cross-sectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279.

- Huynh KN, Nguyen BD. Histiocytosis and neoplasms of macrophagedendritic cell lineages: multimodality imaging with emphasis on PET/CT. Radiographics. 2021;41:576-594. doi: 10.1148/rg.2021200096

- Hilal T, DiCaudo DJ, Connolly SM, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a 30-year single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2018;97:1471-1479.

- Oumeish OY, Oumeish I, Tarawneh M, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma associated with paraproteinemia and non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma developing into chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the first case reported in the literature and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:306-310.

- Damsky W, Thakral D, McGeary MK, et al. Janus kinase inhibition induces disease remission in cutaneous sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:612-621. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2019.05.098

- Wang A, Rahman NT, McGeary MK, et al. Treatment of granuloma annulare and suppression of proinflammatory cytokine activity with tofacitinib. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:1795-1809. doi:10.1016 /j.jaci.2020.10.012

- Stratman S, Amara S, Tan KJ, et al. Systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in the management of granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol Res. 2025;317:743. doi:10.1007/s00403-025-04248-1

- McPhie ML, Swales WC, Gooderham MJ. Improvement of granulomatous skin conditions with tofacitinib in three patients: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211039477. doi: 10.1177/2050313X211039477

- Sood S, Heung M, Georgakopoulos JR, et al. Use of Janus kinase inhibitors for granulomatous dermatoses: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:357-359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.024

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

Rare Case of Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma on the Scalp

PRACTICE POINTS

- In skin of color, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma can appear orange or brown compared to its yellow appearance in lighter skin types.

- When necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is suspected, a thorough malignancy workup should be conducted.

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

As the health care landscape continues to shift, direct care (also known as direct pay) models have emerged as attractive alternatives to traditional insurance-based practice. For dermatology residents poised to enter the workforce, the direct care model offers potential advantages in autonomy, patient relationships, and work-life balance, but not without considerable risks and operational challenges. This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

The transition from dermatology residency to clinical practice allows for a variety of paths, from large academic institutions to private practice to corporate entities (private equity–owned groups). In recent years, the direct care model has gained traction, particularly among physicians seeking greater autonomy and a more sustainable pace of practice.

Direct care dermatology practices operate outside the constraints of third-party payers, offering patients transparent pricing and direct access to care in exchange for fees paid out of pocket. By eliminating insurance companies as the middleman, it allows for less overhead, longer visits with patients, and increased access to care; however, though this model may seem appealing, direct care practices are not without their own set of challenges, especially amid rising concerns over physician burnout and administrative burden.

This article explores the key benefits and drawbacks of starting a direct care dermatology practice, providing a framework to help early-career dermatologists determine whether this path aligns with their personal and professional goals.

Despite its appeal, starting a direct care practice is not without substantial risks and hurdles—particularly for residents just out of training. These challenges include financial risks and startup costs, market uncertainty, lack of mentorship or support, and limitations in treating complex dermatologic conditions.

Before committing to practicing via a direct care model, dermatology residents should reflect on the following:

- Risk tolerance: Are you comfortable navigating the business and financial risk?

- Location: Does your target community have patients willing and able to pay out of pocket?

- Scope of interest: Will a direct care practice align with your clinical passions?

- Support systems: Do you have access to mentors, legal and financial advisors, and operational support?

- Long-term goals: Are you building a lifestyle practice, a scalable business, or a stepping stone to a future opportunity?

Ultimately, the decision to pursue a direct care model requires careful reflection on personal values, financial preparedness, and the unique needs of the community one intends to serve.

The direct care dermatology model offers an appealing alternative to traditional practice, especially for those prioritizing autonomy, patient connection, and work-life balance; however, it demands an entrepreneurial spirit as well as careful planning and an acceptance of financial uncertainty—factors that may pose challenges for new graduates. For dermatology residents, the decision to pursue direct care should be grounded in personal values, practical considerations, and a clear understanding of both the opportunities and limitations of this evolving practice model.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

- Sinsky CA, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med.

- Dorrell DN, Feldman S, Wei-ting Huang W. The most common causes of burnout among US academic dermatologists based on a survey study. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 2019;81:269-270.

- Carlasare LE. Defining the place of direct primary care in a value-based care system. WMJ. 2018;117:106-110.

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

Direct Care Dermatology: Weighing the Pros and Cons for the Early-Career Physician

PRACTICE POINTS

- Direct care practices may be the new horizon of health care.

- Starting a direct care practice offers autonomy but demands entrepreneurial readiness.

- New dermatologists can enjoy control over scheduling, pricing, and patient care, but success requires business acumen, financial planning, and comfort with risk.

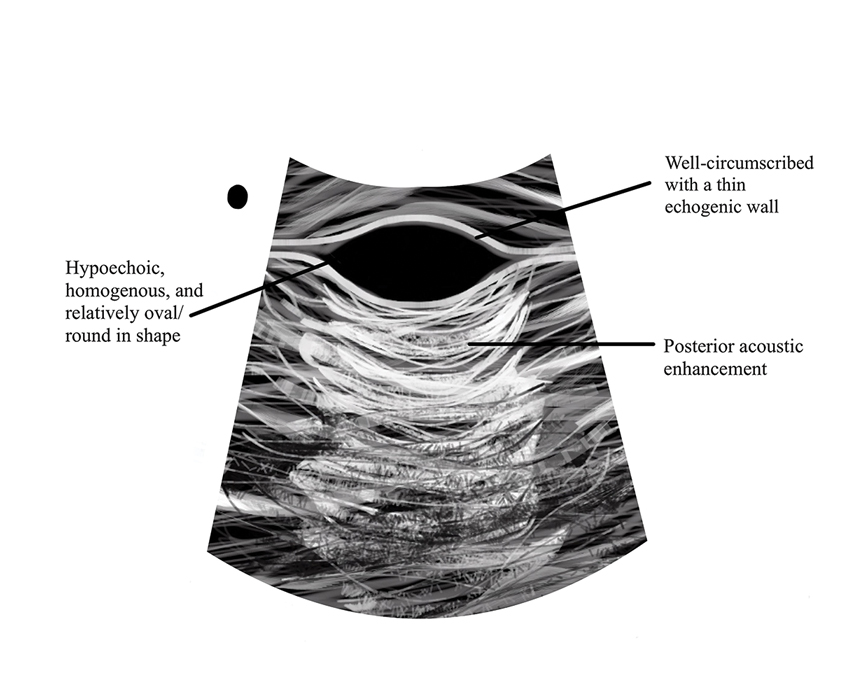

Streamlined Testosterone Order Template to Improve the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Streamlined Testosterone Order Template to Improve the Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Testosterone therapy is administered following pragmatic diagnostic evaluation and workup to assess whether an adult male is hypogonadal, based on symptoms consistent with androgen deficiency and low morning serum testosterone concentrations on ≥ 2 occasions. Effects of testosterone administration include the development or maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and increases in libido, muscle strength, fat-free mass, and bone density.

Testosterone prescriptions have markedly increased in the past 20 years, including within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system.1-3 This trend may be influenced by various factors, including patient perceptions of benefit, an increase in marketing, and the availability of more user-friendly formulations.

Since 2006, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have recommended specific clinical and laboratory evaluation and counseling prior to starting testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).4-8 However, research has shown poor adherence to these recommendations, including at the VA, which raises concerns about inappropriate TRT initiation without proper diagnostic evaluation.9,10 Observational research has suggested a possible link between testosterone therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events. The US Food and Drug Administration prescribing information includes boxed warnings about potential risks of high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV-related mortality with testosterone treatment, contact transfer of transdermal testosterone, and pulmonary oil microembolism with testosterone undecanoate injections.11-15

A VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) review of VA clinician adherence to clinical and laboratory evaluation guidelines for testosterone deficiency found poor adherence among VA practitioners and made recommendations for improvement.4,15 These focused on establishing clinical signs and symptoms consistent with testosterone deficiency, confirming hypogonadism by repeated testosterone testing, determining the etiology of hypogonadism by measuring gonadotropins, initiating a discussion of risks and benefits of TRT, and assessing clinical improvement and obtaining an updated hematocrit test within 3 to 6 months of initiation.

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) developed a local prior authorization template to assist health care practitioners (HCPs) to address the OIG recommendations. This testosterone order template (TOT) aimed to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, and monitoring of TRT in males with hypogonadism, combined with existing VA pharmacy criteria for the use of testosterone based on Endocrine Society guidelines. A version of the VAPSHCS TOT was approved as the national VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) template.

Preliminary evaluation of the TOT suggested improved short-term adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation.16 This quality improvement study sought to assess the long-term effectiveness of the TOT with respect to clinical practice guideline adherence. The OIG did not address prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring because understanding of the relationship between TRT and the risks of elevated PSA levels remains incomplete.6,17 This project hypothesized that implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT incorporated into CPRS would result in higher adherence rates to guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory evaluation, in addition to counseling of men with hypogonadism prior to initiation of TRT.

Methods

Eligible participants were cisgender males who received a new testosterone prescription, had ≥ 2 clinic visits at VAPSHCS, and no previous testosterone prescription in the previous 2 years. Individuals were excluded if they had testosterone administered at VAPSHCS; were prescribed testosterone at another facility (VA or community-based); pilot tested an initial version of the TOT prior to November 30, 2019; or had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for hypopituitarism, gender identity disorder, history of sexual assignment, or Klinefelter syndrome for which testosterone therapy was already approved. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

This quality improvement project used a retrospective, pre-post experimental design. Electronic chart review and systematic manual review of all eligible patient charts were performed for the pretemplate period (December 1, 2018, to November 30, 2019) and after the template implementation, (December 1, 2021, to November 30, 2022).

An initial version of the TOT was implemented on July 1, 2019, but was not fully integrated into CPRS until early 2020; individuals in whom the TOT was used prior to November 30, 2019, were excluded. Data from the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic were avoided because of alterations in clinic and prescribing practices. As a quality improvement project, the TOT evaluation was exempt from formal review by the VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board, as determined by the Director of the Office of Transformation/Quality/Safety/Value.

Interventions

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled substance with potential risks and a propensity for varied prescribing practices. It was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) for which a specific TOT was developed, approved by the VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and incorporated into CPRS. A team of pharmacists, primary care physicians, geriatricians, endocrinologists, and health informatics experts created and developed the TOT. Pharmacists managed and monitored its completion.

The process for prescribing testosterone via the TOT is outlined in the eAppendix. When an HCP orders testosterone in CPRS, reminders prompt them to use the TOT and indicate required laboratory measurements (an order set is provided). Completion of TOT is not necessary to order testosterone for patients with an existing diagnosis of an organic cause of hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter syndrome or hypopituitarism) or transgender women (assigned male at birth). In the TOT, the prescriber must also indicate signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; required laboratory tests; and counseling regarding potential risks and benefits of TRT. A pharmacist reviews the TOT and either approves or rejects the testosterone prescription and provides follow-up guidance to the prescriber. The completed TOT serves as documentation of guideline adherence in CPRS. The TOT also includes sections for first renewal testosterone prescriptions, addressing guideline recommendations for follow-up laboratory evaluation and clinical response to TRT. Due to limited completion of this section in the posttemplate period, evaluating adherence to follow-up recommendations was not feasible.

Measures

This project assessed the percentage of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period with an approved PADR. Documentation of specific guideline-recommended measures was assessed: signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; ≥ 2 serum testosterone measurements (≥ 2 total, free and total, or 2 free testosterone levels, and ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10

The project also assessed the proportion of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period who had all hormone tests (≥ 2 serum testosterone and LH and FSH concentrations), all laboratory tests (hormone tests and hematocrit), and all 5 guideline-recommended measures.

Analysis

Statistical comparisons between the proportions of patients in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods for each measure were performed using a χ2 test, without correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. A P value < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

Results

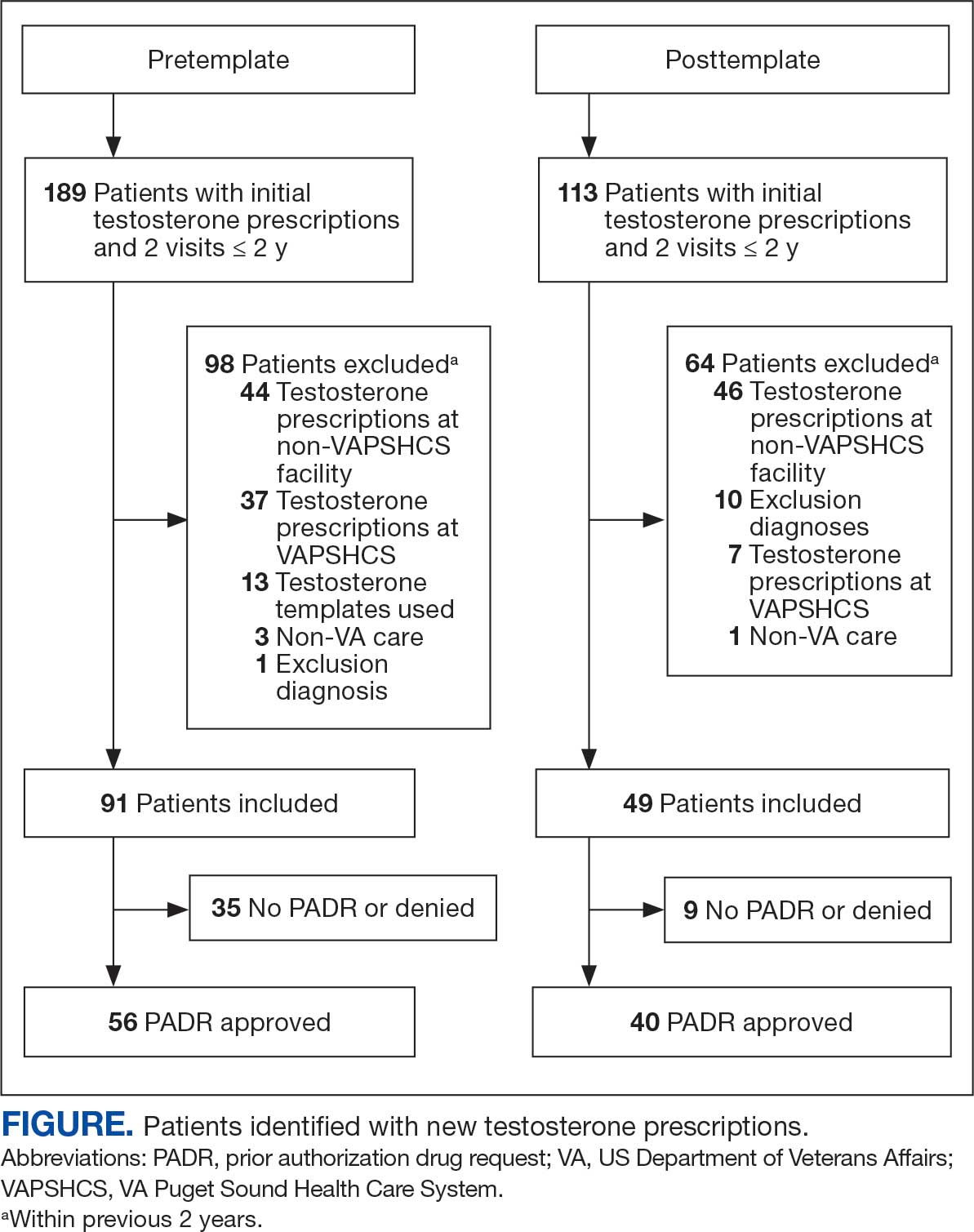

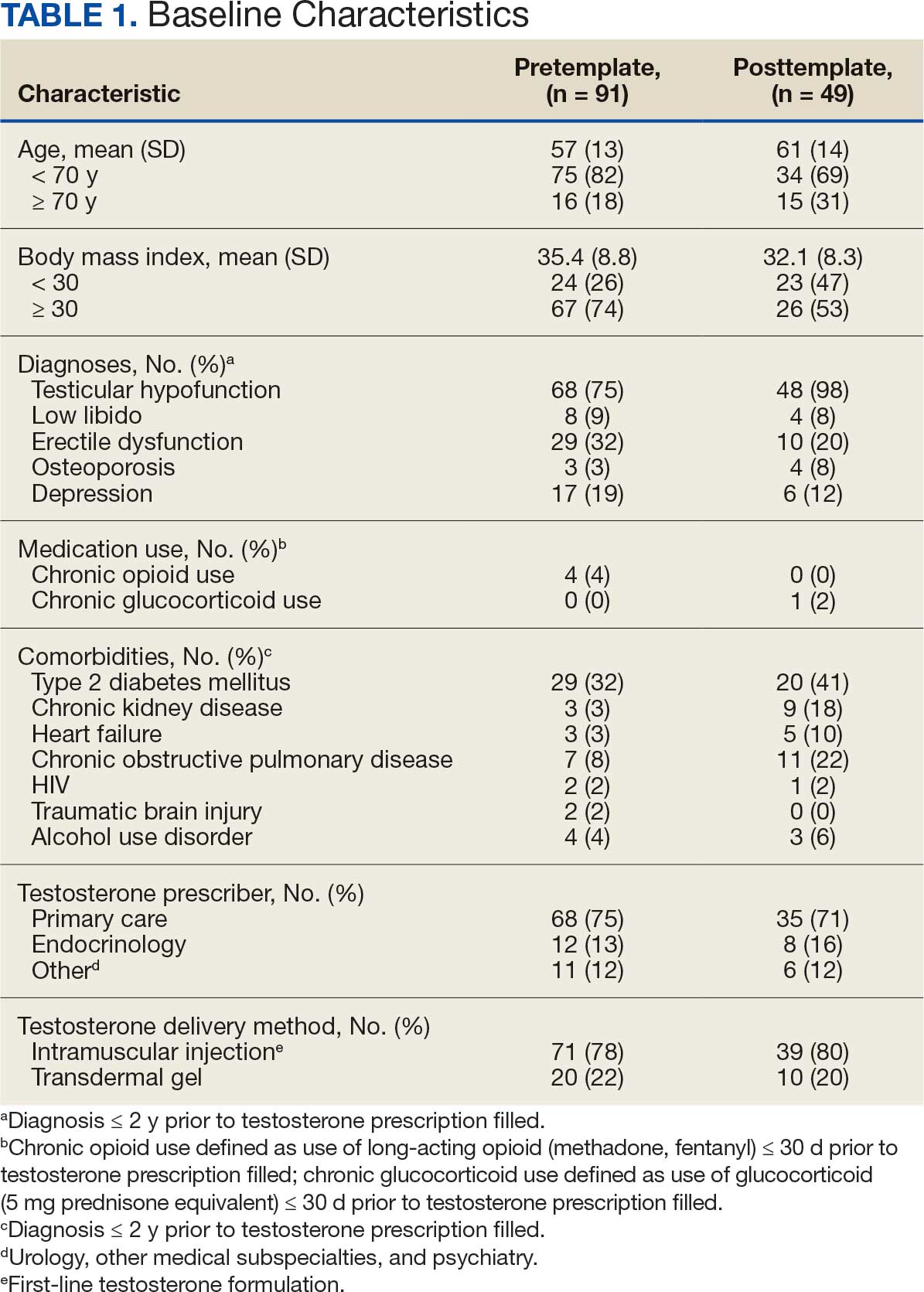

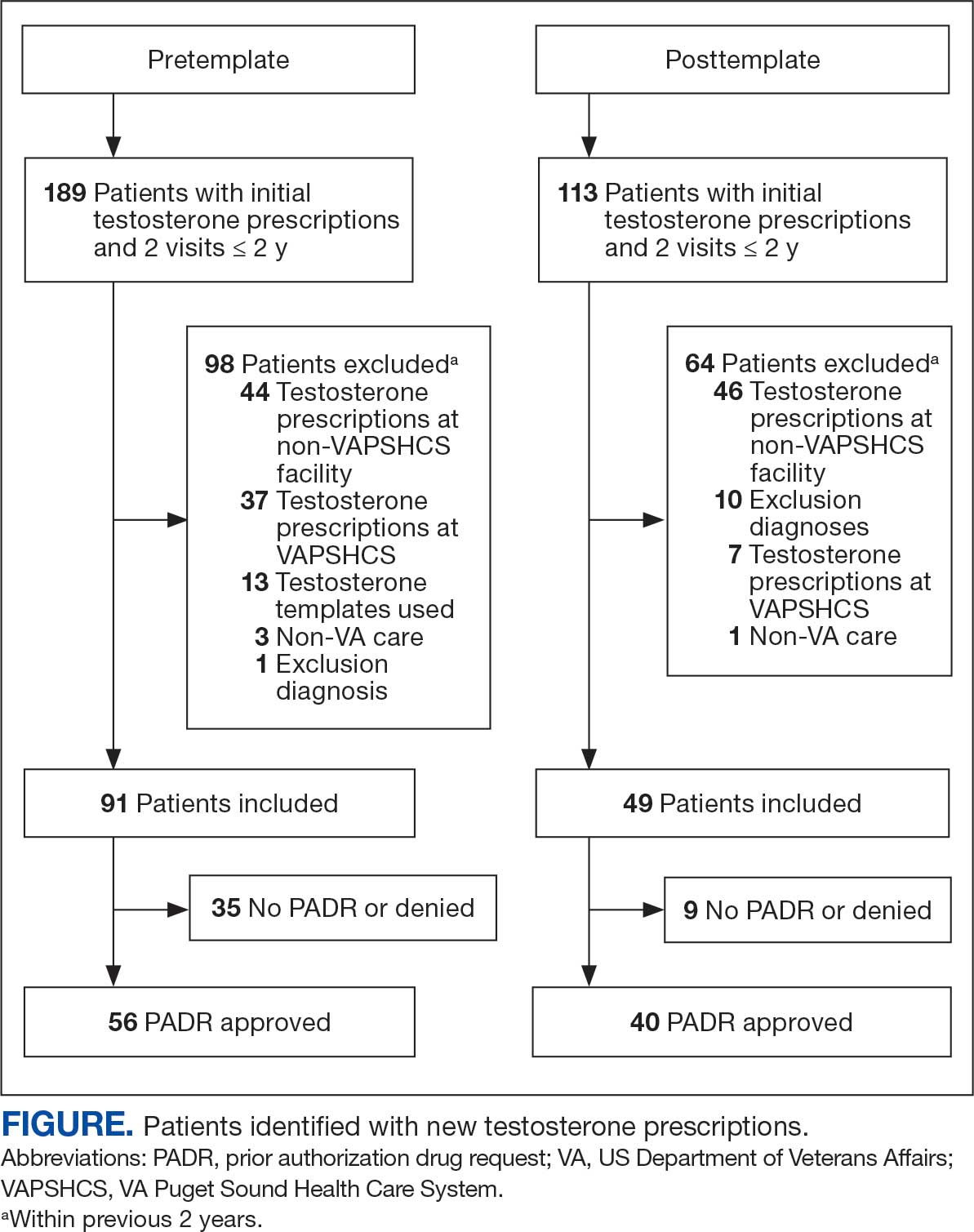

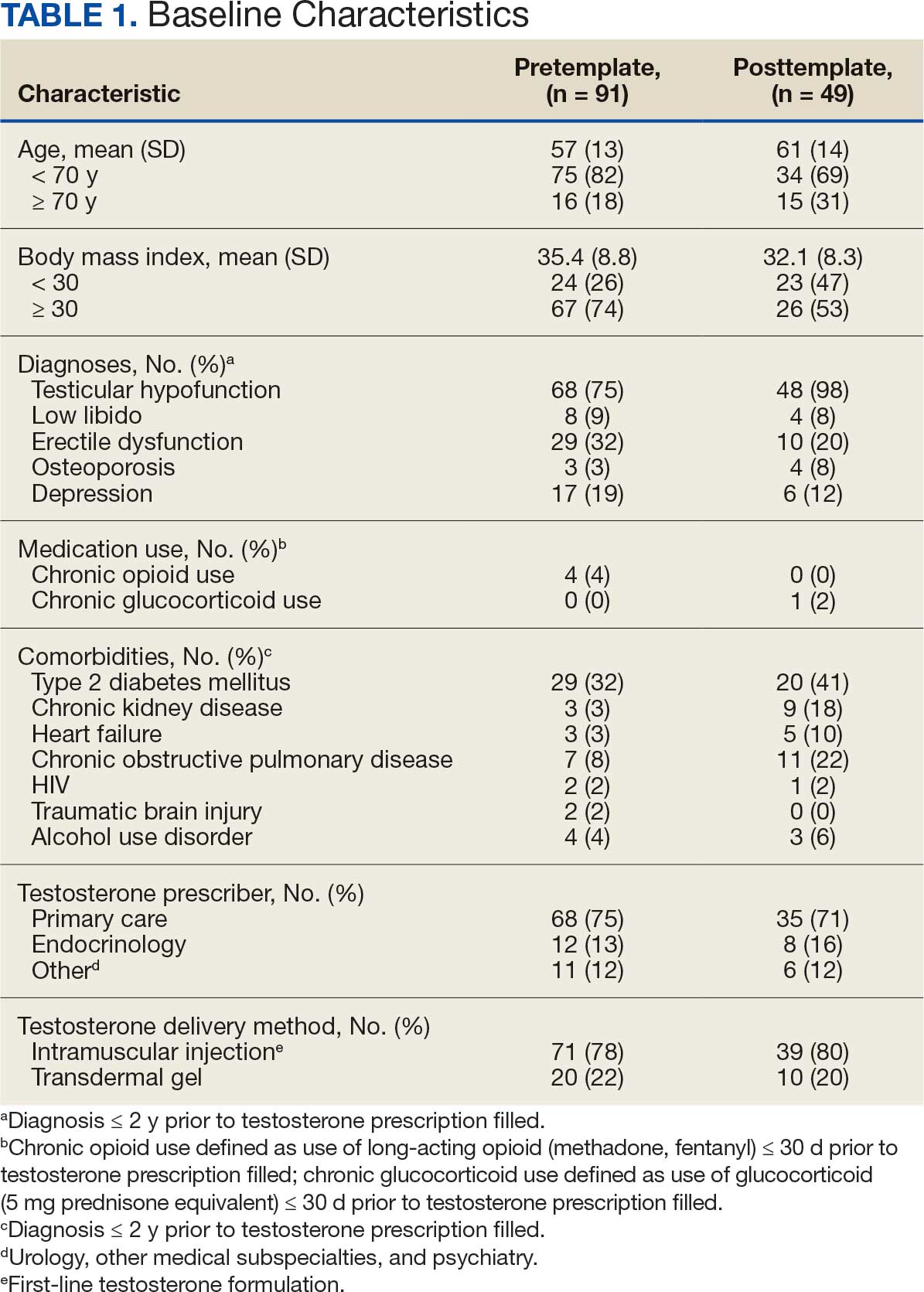

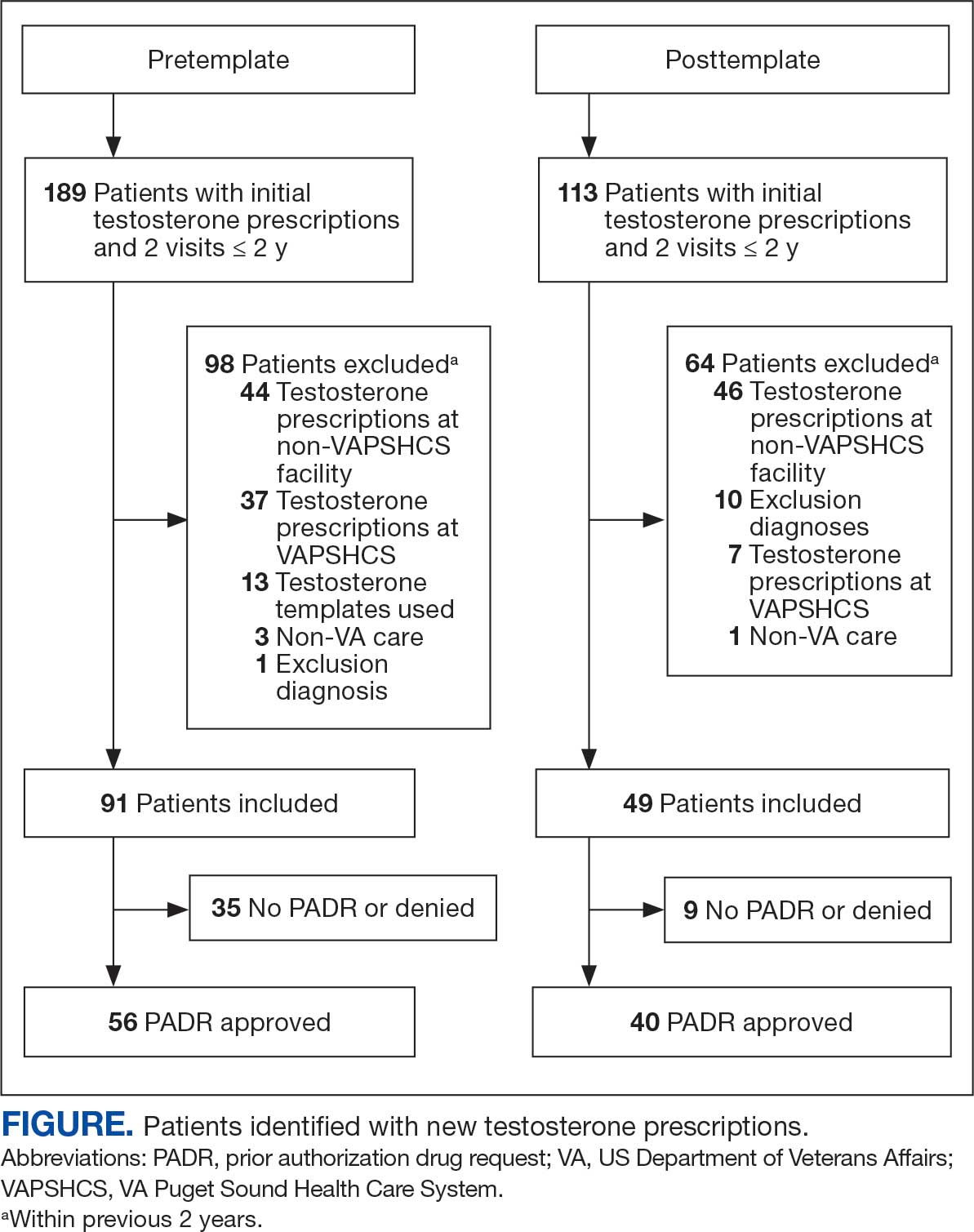

Chart review identified 189 patients in the pretemplate period and 113 patients in the posttemplate period with a new testosterone prescription (Figure). After exclusions, 91 and 49 patients, respectively, met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Fifty-six patients (62%) pretemplate and 40 patients (82%) posttemplate (P = .015) had approved PADRs and comprised the groups that were analyzed (Table 2).

The mean age and body mass index were similar in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods, but there was variation in the proportions of patients aged < 70 years and those with a body mass index < 30 between the groups. The most common diagnosis in both groups was testicular hypofunction, and the most common comorbidity was type 2 diabetes mellitus. Concomitant use of opioids or glucocorticoids that can lower testosterone levels was rare. Most testosterone prescriptions originated from primary care clinics in both periods: 68 (75%) in the pretemplate period and 35 (71%) in the posttemplate period. Most testosterone treatment was delivered by intramuscular injection.

In the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period, the proportion of patients with an approved PADR (82% vs 62%, P = .02), and documentation of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism (93% vs 71%, P = .002) prior to starting TRT were higher, while the percentage of patients having ≥ 2 testosterone measurements (85% vs 89%, P = .53), ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10 AM (78% vs 75%, P = .70), and hematocrit measured (95% vs 91%, P = .47) were similar. Rates of LH and FSH testing were higher in the posttemplate period (80%) vs the pretemplate period (63%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .07), and discussion of the risks and benefits of TRT was higher in the posttemplate period (58%) vs the pretemplate period (34%) (P = .02). The percentage of patients who had all hormone measurements (total and/or free testosterone, LH, and FSH) was higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (59%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .06). The rates of all guideline-recommended laboratory test orders were higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (55%) (P = .03), and all 5 guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory measures were higher in the posttemplate period (45%) vs the pretemplate period (18%) (P = .004).

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT in CPRS demonstrated higher adherence to evidence-based guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating hypogonadism before TRT. After TOT implementation, a higher proportion of patients had documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency, underwent all recommended laboratory tests, and had discussions about the risks and benefits of TRT. Adherence to 5 clinical and laboratory measures recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines was higher after TOT implementation, indicating improved prescribing practices.4

The requirement for TOT completion before testosterone prescription and its management by trained pharmacists likely contributed to higher adherence to guideline recommendations than previously reported. Integration of the TOT into CPRS with pharmacy oversight may have enhanced adherence by summarizing and codifying evidence-based guideline recommendations for clinical and biochemical evaluation prior to TRT initiation, offering relevant education to clinicians and pharmacists, automatically importing pertinent clinical information and laboratory results, and generating CPRS documentation to reduce clinician burden during patient care.

The proportion of patients with documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency before TRT increased from the pretemplate period (71%) to the posttemplate period (93%), indicating that most patients receiving TRT had clinical manifestations of hypogonadism. This aligns with Endocrine Society guidelines, which define hypogonadism as a clinical disorder characterized by clinical manifestations of testosterone deficiency and persistently low serum testosterone levels on ≥ 2 separate occasions.4,6 However, recent trends in direct-to-consumer advertising for testosterone and the rise of “low T” clinics may contribute to increased testing, varied practices, and inappropriate testosterone therapy initiation (eg, in men with low testosterone levels who lack symptoms of hypogonadism).18 Improved adherence in documenting clinical hypogonadism with implementation of the TOT reinforces the value of incorporating educational material, as previously reported.11

Adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation of the TOT in this project was higher than those previously reported. In a study of 111,631 outpatient veterans prescribed testosterone from 2009 to 2012, only 18.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 3.5% had ≥ 2 testosterone, LH, and FSH levels measured prior to the initiation of a TRT.9 In a report of 63,534 insured patients who received TRT from 2010 to 2012, 40.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 12% had LH and/or FSH measured prior to the initiation.8

Low rates of guideline-recommended laboratory tests prior to initiation of testosterone treatment were reported in prior non-VA studies.19,20 Poor guideline adherence reinforces the need for clinician education or other methods to improve TRT and ensure appropriate prescribing practices across health care systems. The TOT described in this project is a sustainable clinical tool with the potential to improve testosterone prescribing practices.

The high rates of adherence to guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS likely stem from local endocrine expertise and ongoing educational initiatives, as well as the requirement for template completion before testosterone prescription. However, most testosterone prescriptions were initiated by primary care and monitored by pharmacists with varying degrees of training and clinical experience in hypogonadism and TRT.

However, adherence to guideline recommendations was modest, suggesting there is still an opportunity for improvement. The decision to initiate therapy should be made only after appropriate counseling with patients regarding its potential benefits and risks. Reports on the CV risk of TRT have been mixed. The 2023 TRAVERSE study found no increase in major adverse CV events among older men with hypogonadism and pre-existing CV risks undergoing TRT, but noted higher instances of pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, and acute kidney injury.21 This highlights the need for clinicians to continue to engage in informed decision-making with patients. Effective pretreatment counseling is important but time-consuming; future TOT monitoring and modifications could consider mandatory checkboxes to document counseling on TRT risks and benefits.

The TOT described in this study could be adapted and incorporated into the prescribing process and electronic health record of larger health care systems. Use of an electronic template allows for automatic real-time dashboard monitoring of organization performance. The TOT described could be modified or simplified for specialty or primary care clinics or individual practitioners to improve adherence to evidence-based guideline recommendations and quality of care.

Strengths

A strength of this study is the multidisciplinary team (composed of stakeholders with experience in VA health care system and subject matter experts in hypogonadism) that developed and incorporated a user-friendly template for testosterone prescriptions; the use of evidence-based guideline recommendations; and the use of a structured chart review permitted accurate assessment of adherence to recommendations to document signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency and a discussion of potential risks and benefits prior to TRT. To our knowledge, these recommendations have not been assessed in previous reports.

Limitations

The retrospective pre-post design of this study precludes a conclusion that implementation of the TOT caused the increase in adherence to guideline recommendations. Improved adherence could have resulted from the ongoing development of the preauthorization process for testosterone prescriptions or other changes over time. However, the preauthorization process had already been established for many years prior to template implementation. Forty-nine patients had new prescriptions for testosterone in the posttemplate period compared to 91 in the pretemplate period, but TRT was initiated in accordance with guideline recommendations more appropriately in the posttemplate period. The study’s sample size was small, and many eligible patients were excluded; however, exclusions were necessary to evaluate men who had new testosterone prescriptions for which the template was designed. Most men excluded were already taking testosterone.

Conclusions

The implementation of a CPRS-based TOT improved adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation, and counseling of patients with hypogonadism before starting TRT. While there were improvements in adherence with the TOT, the relatively low proportion of patients with documentation of TRT risks and benefits and all guideline recommendations highlights the need for additional efforts to further strengthen adherence to guideline recommendations and ensure appropriate evaluation, counseling, and prescribing practices before initiating TRT.

- Layton JB, Li D, Meier CR, et al. Testosterone lab testing and initiation in the United Kingdom and the United States, 2000 to 2011. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:835-842. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-3570

- Baillargeon J, Kuo YF, Westra JR, et al. Testosterone prescribing in the United States, 2002-2016. JAMA. 2018;320:200-202. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7999

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Rose AJ. Patterns of testosterone prescription overuse. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24:240-245. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000336

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995-2010. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2847

- Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536-2559. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2354

- Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1715-1744. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00229

- Mulhall JP, Trost LW, Brannigan RE, et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.03.115

- Muram D, Zhang X, Cui Z, et al. Use of hormone testing for the diagnosis and evaluation of male hypogonadism and monitoring of testosterone therapy: application of hormone testing guideline recommendations in clinical practice. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1886-1894. doi:10.1111/jsm.12968

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Ascertainment of testosterone prescribing practices in the VA. Med Care. 2015;53:746-752. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000398?

- Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, et al. Who gets testosterone? Patient characteristics associated with testosterone prescribing in the Veteran Affairs system: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:304-311. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3940-7

- Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:109-122. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000485

- Vigen R, O’Donnell CI, Barón AE, et al. Association of testosterone therapy with mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke in men with low testosterone levels. JAMA. 2013;310:1829-1836. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.280386

- Finkle WD, Greenland S, Ridgeway GK, et al. Increased risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction following testosterone therapy prescription in men. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85805. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085805

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA cautions about using testosterone products for low testosterone due to aging; requires labeling change to inform of possible increased risk of heart attack and stroke with use. FDA.gov. March 3, 2015. Updated February 28, 2025. Accessed July 8, 2025. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm436259.htm

- US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Healthcare inspection – testosterone replacement therapy initiation and follow-up evaluation in VA male patients. April 11, 2018. Accessed July 8, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/healthcare-inspection-testosterone-replacement-therapy

- Narla R, Mobley D, Nguyen EHK, et al. Preliminary evaluation of an order template to improve diagnosis and testosterone therapy of hypogonadism in veterans. Fed Pract. 2021;38:121-127. doi:10.12788/fp.0103

- Bhasin S, Travison TG, Pencina KM, et al. Prostate safety events during testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2348692. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.48692

- Dubin JM, Jesse E, Fantus RJ, et al. Guideline-discordant care among direct-to-consumer testosterone therapy platforms. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:1321-1323. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4928

- Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Trends in androgen prescribing in the United States, 2001 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1465-1466. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6895

- Locke JA, Flannigan R, Günther OP, et al. Testosterone therapy: prescribing and monitoring patterns of practice in British Columbia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15:e110-e117. doi:10.5489/cuaj.6586

- Lincoff AM, Bhasin S, Flevaris P, et al. Cardiovascular safety of testosterone-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:107-117. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2215025

Testosterone therapy is administered following pragmatic diagnostic evaluation and workup to assess whether an adult male is hypogonadal, based on symptoms consistent with androgen deficiency and low morning serum testosterone concentrations on ≥ 2 occasions. Effects of testosterone administration include the development or maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and increases in libido, muscle strength, fat-free mass, and bone density.

Testosterone prescriptions have markedly increased in the past 20 years, including within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system.1-3 This trend may be influenced by various factors, including patient perceptions of benefit, an increase in marketing, and the availability of more user-friendly formulations.

Since 2006, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have recommended specific clinical and laboratory evaluation and counseling prior to starting testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).4-8 However, research has shown poor adherence to these recommendations, including at the VA, which raises concerns about inappropriate TRT initiation without proper diagnostic evaluation.9,10 Observational research has suggested a possible link between testosterone therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events. The US Food and Drug Administration prescribing information includes boxed warnings about potential risks of high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV-related mortality with testosterone treatment, contact transfer of transdermal testosterone, and pulmonary oil microembolism with testosterone undecanoate injections.11-15

A VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) review of VA clinician adherence to clinical and laboratory evaluation guidelines for testosterone deficiency found poor adherence among VA practitioners and made recommendations for improvement.4,15 These focused on establishing clinical signs and symptoms consistent with testosterone deficiency, confirming hypogonadism by repeated testosterone testing, determining the etiology of hypogonadism by measuring gonadotropins, initiating a discussion of risks and benefits of TRT, and assessing clinical improvement and obtaining an updated hematocrit test within 3 to 6 months of initiation.

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) developed a local prior authorization template to assist health care practitioners (HCPs) to address the OIG recommendations. This testosterone order template (TOT) aimed to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, and monitoring of TRT in males with hypogonadism, combined with existing VA pharmacy criteria for the use of testosterone based on Endocrine Society guidelines. A version of the VAPSHCS TOT was approved as the national VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) template.

Preliminary evaluation of the TOT suggested improved short-term adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation.16 This quality improvement study sought to assess the long-term effectiveness of the TOT with respect to clinical practice guideline adherence. The OIG did not address prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring because understanding of the relationship between TRT and the risks of elevated PSA levels remains incomplete.6,17 This project hypothesized that implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT incorporated into CPRS would result in higher adherence rates to guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory evaluation, in addition to counseling of men with hypogonadism prior to initiation of TRT.

Methods

Eligible participants were cisgender males who received a new testosterone prescription, had ≥ 2 clinic visits at VAPSHCS, and no previous testosterone prescription in the previous 2 years. Individuals were excluded if they had testosterone administered at VAPSHCS; were prescribed testosterone at another facility (VA or community-based); pilot tested an initial version of the TOT prior to November 30, 2019; or had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for hypopituitarism, gender identity disorder, history of sexual assignment, or Klinefelter syndrome for which testosterone therapy was already approved. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

This quality improvement project used a retrospective, pre-post experimental design. Electronic chart review and systematic manual review of all eligible patient charts were performed for the pretemplate period (December 1, 2018, to November 30, 2019) and after the template implementation, (December 1, 2021, to November 30, 2022).

An initial version of the TOT was implemented on July 1, 2019, but was not fully integrated into CPRS until early 2020; individuals in whom the TOT was used prior to November 30, 2019, were excluded. Data from the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic were avoided because of alterations in clinic and prescribing practices. As a quality improvement project, the TOT evaluation was exempt from formal review by the VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board, as determined by the Director of the Office of Transformation/Quality/Safety/Value.

Interventions

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled substance with potential risks and a propensity for varied prescribing practices. It was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) for which a specific TOT was developed, approved by the VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and incorporated into CPRS. A team of pharmacists, primary care physicians, geriatricians, endocrinologists, and health informatics experts created and developed the TOT. Pharmacists managed and monitored its completion.

The process for prescribing testosterone via the TOT is outlined in the eAppendix. When an HCP orders testosterone in CPRS, reminders prompt them to use the TOT and indicate required laboratory measurements (an order set is provided). Completion of TOT is not necessary to order testosterone for patients with an existing diagnosis of an organic cause of hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter syndrome or hypopituitarism) or transgender women (assigned male at birth). In the TOT, the prescriber must also indicate signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; required laboratory tests; and counseling regarding potential risks and benefits of TRT. A pharmacist reviews the TOT and either approves or rejects the testosterone prescription and provides follow-up guidance to the prescriber. The completed TOT serves as documentation of guideline adherence in CPRS. The TOT also includes sections for first renewal testosterone prescriptions, addressing guideline recommendations for follow-up laboratory evaluation and clinical response to TRT. Due to limited completion of this section in the posttemplate period, evaluating adherence to follow-up recommendations was not feasible.

Measures

This project assessed the percentage of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period with an approved PADR. Documentation of specific guideline-recommended measures was assessed: signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; ≥ 2 serum testosterone measurements (≥ 2 total, free and total, or 2 free testosterone levels, and ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10

The project also assessed the proportion of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period who had all hormone tests (≥ 2 serum testosterone and LH and FSH concentrations), all laboratory tests (hormone tests and hematocrit), and all 5 guideline-recommended measures.

Analysis

Statistical comparisons between the proportions of patients in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods for each measure were performed using a χ2 test, without correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. A P value < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

Results

Chart review identified 189 patients in the pretemplate period and 113 patients in the posttemplate period with a new testosterone prescription (Figure). After exclusions, 91 and 49 patients, respectively, met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Fifty-six patients (62%) pretemplate and 40 patients (82%) posttemplate (P = .015) had approved PADRs and comprised the groups that were analyzed (Table 2).

The mean age and body mass index were similar in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods, but there was variation in the proportions of patients aged < 70 years and those with a body mass index < 30 between the groups. The most common diagnosis in both groups was testicular hypofunction, and the most common comorbidity was type 2 diabetes mellitus. Concomitant use of opioids or glucocorticoids that can lower testosterone levels was rare. Most testosterone prescriptions originated from primary care clinics in both periods: 68 (75%) in the pretemplate period and 35 (71%) in the posttemplate period. Most testosterone treatment was delivered by intramuscular injection.

In the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period, the proportion of patients with an approved PADR (82% vs 62%, P = .02), and documentation of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism (93% vs 71%, P = .002) prior to starting TRT were higher, while the percentage of patients having ≥ 2 testosterone measurements (85% vs 89%, P = .53), ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10 AM (78% vs 75%, P = .70), and hematocrit measured (95% vs 91%, P = .47) were similar. Rates of LH and FSH testing were higher in the posttemplate period (80%) vs the pretemplate period (63%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .07), and discussion of the risks and benefits of TRT was higher in the posttemplate period (58%) vs the pretemplate period (34%) (P = .02). The percentage of patients who had all hormone measurements (total and/or free testosterone, LH, and FSH) was higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (59%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .06). The rates of all guideline-recommended laboratory test orders were higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (55%) (P = .03), and all 5 guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory measures were higher in the posttemplate period (45%) vs the pretemplate period (18%) (P = .004).

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT in CPRS demonstrated higher adherence to evidence-based guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating hypogonadism before TRT. After TOT implementation, a higher proportion of patients had documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency, underwent all recommended laboratory tests, and had discussions about the risks and benefits of TRT. Adherence to 5 clinical and laboratory measures recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines was higher after TOT implementation, indicating improved prescribing practices.4

The requirement for TOT completion before testosterone prescription and its management by trained pharmacists likely contributed to higher adherence to guideline recommendations than previously reported. Integration of the TOT into CPRS with pharmacy oversight may have enhanced adherence by summarizing and codifying evidence-based guideline recommendations for clinical and biochemical evaluation prior to TRT initiation, offering relevant education to clinicians and pharmacists, automatically importing pertinent clinical information and laboratory results, and generating CPRS documentation to reduce clinician burden during patient care.

The proportion of patients with documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency before TRT increased from the pretemplate period (71%) to the posttemplate period (93%), indicating that most patients receiving TRT had clinical manifestations of hypogonadism. This aligns with Endocrine Society guidelines, which define hypogonadism as a clinical disorder characterized by clinical manifestations of testosterone deficiency and persistently low serum testosterone levels on ≥ 2 separate occasions.4,6 However, recent trends in direct-to-consumer advertising for testosterone and the rise of “low T” clinics may contribute to increased testing, varied practices, and inappropriate testosterone therapy initiation (eg, in men with low testosterone levels who lack symptoms of hypogonadism).18 Improved adherence in documenting clinical hypogonadism with implementation of the TOT reinforces the value of incorporating educational material, as previously reported.11

Adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation of the TOT in this project was higher than those previously reported. In a study of 111,631 outpatient veterans prescribed testosterone from 2009 to 2012, only 18.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 3.5% had ≥ 2 testosterone, LH, and FSH levels measured prior to the initiation of a TRT.9 In a report of 63,534 insured patients who received TRT from 2010 to 2012, 40.3% had ≥ 2 testosterone prescriptions, and 12% had LH and/or FSH measured prior to the initiation.8

Low rates of guideline-recommended laboratory tests prior to initiation of testosterone treatment were reported in prior non-VA studies.19,20 Poor guideline adherence reinforces the need for clinician education or other methods to improve TRT and ensure appropriate prescribing practices across health care systems. The TOT described in this project is a sustainable clinical tool with the potential to improve testosterone prescribing practices.

The high rates of adherence to guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS likely stem from local endocrine expertise and ongoing educational initiatives, as well as the requirement for template completion before testosterone prescription. However, most testosterone prescriptions were initiated by primary care and monitored by pharmacists with varying degrees of training and clinical experience in hypogonadism and TRT.

However, adherence to guideline recommendations was modest, suggesting there is still an opportunity for improvement. The decision to initiate therapy should be made only after appropriate counseling with patients regarding its potential benefits and risks. Reports on the CV risk of TRT have been mixed. The 2023 TRAVERSE study found no increase in major adverse CV events among older men with hypogonadism and pre-existing CV risks undergoing TRT, but noted higher instances of pulmonary embolism, atrial fibrillation, and acute kidney injury.21 This highlights the need for clinicians to continue to engage in informed decision-making with patients. Effective pretreatment counseling is important but time-consuming; future TOT monitoring and modifications could consider mandatory checkboxes to document counseling on TRT risks and benefits.

The TOT described in this study could be adapted and incorporated into the prescribing process and electronic health record of larger health care systems. Use of an electronic template allows for automatic real-time dashboard monitoring of organization performance. The TOT described could be modified or simplified for specialty or primary care clinics or individual practitioners to improve adherence to evidence-based guideline recommendations and quality of care.

Strengths

A strength of this study is the multidisciplinary team (composed of stakeholders with experience in VA health care system and subject matter experts in hypogonadism) that developed and incorporated a user-friendly template for testosterone prescriptions; the use of evidence-based guideline recommendations; and the use of a structured chart review permitted accurate assessment of adherence to recommendations to document signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency and a discussion of potential risks and benefits prior to TRT. To our knowledge, these recommendations have not been assessed in previous reports.

Limitations

The retrospective pre-post design of this study precludes a conclusion that implementation of the TOT caused the increase in adherence to guideline recommendations. Improved adherence could have resulted from the ongoing development of the preauthorization process for testosterone prescriptions or other changes over time. However, the preauthorization process had already been established for many years prior to template implementation. Forty-nine patients had new prescriptions for testosterone in the posttemplate period compared to 91 in the pretemplate period, but TRT was initiated in accordance with guideline recommendations more appropriately in the posttemplate period. The study’s sample size was small, and many eligible patients were excluded; however, exclusions were necessary to evaluate men who had new testosterone prescriptions for which the template was designed. Most men excluded were already taking testosterone.

Conclusions

The implementation of a CPRS-based TOT improved adherence to evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis, evaluation, and counseling of patients with hypogonadism before starting TRT. While there were improvements in adherence with the TOT, the relatively low proportion of patients with documentation of TRT risks and benefits and all guideline recommendations highlights the need for additional efforts to further strengthen adherence to guideline recommendations and ensure appropriate evaluation, counseling, and prescribing practices before initiating TRT.

Testosterone therapy is administered following pragmatic diagnostic evaluation and workup to assess whether an adult male is hypogonadal, based on symptoms consistent with androgen deficiency and low morning serum testosterone concentrations on ≥ 2 occasions. Effects of testosterone administration include the development or maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and increases in libido, muscle strength, fat-free mass, and bone density.

Testosterone prescriptions have markedly increased in the past 20 years, including within the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system.1-3 This trend may be influenced by various factors, including patient perceptions of benefit, an increase in marketing, and the availability of more user-friendly formulations.

Since 2006, evidence-based clinical practice guidelines have recommended specific clinical and laboratory evaluation and counseling prior to starting testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).4-8 However, research has shown poor adherence to these recommendations, including at the VA, which raises concerns about inappropriate TRT initiation without proper diagnostic evaluation.9,10 Observational research has suggested a possible link between testosterone therapy and increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events. The US Food and Drug Administration prescribing information includes boxed warnings about potential risks of high blood pressure, myocardial infarction, stroke, and CV-related mortality with testosterone treatment, contact transfer of transdermal testosterone, and pulmonary oil microembolism with testosterone undecanoate injections.11-15

A VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) review of VA clinician adherence to clinical and laboratory evaluation guidelines for testosterone deficiency found poor adherence among VA practitioners and made recommendations for improvement.4,15 These focused on establishing clinical signs and symptoms consistent with testosterone deficiency, confirming hypogonadism by repeated testosterone testing, determining the etiology of hypogonadism by measuring gonadotropins, initiating a discussion of risks and benefits of TRT, and assessing clinical improvement and obtaining an updated hematocrit test within 3 to 6 months of initiation.

The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) developed a local prior authorization template to assist health care practitioners (HCPs) to address the OIG recommendations. This testosterone order template (TOT) aimed to improve the diagnosis, evaluation, and monitoring of TRT in males with hypogonadism, combined with existing VA pharmacy criteria for the use of testosterone based on Endocrine Society guidelines. A version of the VAPSHCS TOT was approved as the national VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) template.

Preliminary evaluation of the TOT suggested improved short-term adherence to guideline recommendations following implementation.16 This quality improvement study sought to assess the long-term effectiveness of the TOT with respect to clinical practice guideline adherence. The OIG did not address prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monitoring because understanding of the relationship between TRT and the risks of elevated PSA levels remains incomplete.6,17 This project hypothesized that implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT incorporated into CPRS would result in higher adherence rates to guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory evaluation, in addition to counseling of men with hypogonadism prior to initiation of TRT.

Methods

Eligible participants were cisgender males who received a new testosterone prescription, had ≥ 2 clinic visits at VAPSHCS, and no previous testosterone prescription in the previous 2 years. Individuals were excluded if they had testosterone administered at VAPSHCS; were prescribed testosterone at another facility (VA or community-based); pilot tested an initial version of the TOT prior to November 30, 2019; or had an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for hypopituitarism, gender identity disorder, history of sexual assignment, or Klinefelter syndrome for which testosterone therapy was already approved. Patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

This quality improvement project used a retrospective, pre-post experimental design. Electronic chart review and systematic manual review of all eligible patient charts were performed for the pretemplate period (December 1, 2018, to November 30, 2019) and after the template implementation, (December 1, 2021, to November 30, 2022).

An initial version of the TOT was implemented on July 1, 2019, but was not fully integrated into CPRS until early 2020; individuals in whom the TOT was used prior to November 30, 2019, were excluded. Data from the initial period of the COVID-19 pandemic were avoided because of alterations in clinic and prescribing practices. As a quality improvement project, the TOT evaluation was exempt from formal review by the VAPSHCS Institutional Review Board, as determined by the Director of the Office of Transformation/Quality/Safety/Value.

Interventions

Testosterone is a Schedule III controlled substance with potential risks and a propensity for varied prescribing practices. It was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) for which a specific TOT was developed, approved by the VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and incorporated into CPRS. A team of pharmacists, primary care physicians, geriatricians, endocrinologists, and health informatics experts created and developed the TOT. Pharmacists managed and monitored its completion.

The process for prescribing testosterone via the TOT is outlined in the eAppendix. When an HCP orders testosterone in CPRS, reminders prompt them to use the TOT and indicate required laboratory measurements (an order set is provided). Completion of TOT is not necessary to order testosterone for patients with an existing diagnosis of an organic cause of hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter syndrome or hypopituitarism) or transgender women (assigned male at birth). In the TOT, the prescriber must also indicate signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; required laboratory tests; and counseling regarding potential risks and benefits of TRT. A pharmacist reviews the TOT and either approves or rejects the testosterone prescription and provides follow-up guidance to the prescriber. The completed TOT serves as documentation of guideline adherence in CPRS. The TOT also includes sections for first renewal testosterone prescriptions, addressing guideline recommendations for follow-up laboratory evaluation and clinical response to TRT. Due to limited completion of this section in the posttemplate period, evaluating adherence to follow-up recommendations was not feasible.

Measures

This project assessed the percentage of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period with an approved PADR. Documentation of specific guideline-recommended measures was assessed: signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency; ≥ 2 serum testosterone measurements (≥ 2 total, free and total, or 2 free testosterone levels, and ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10

The project also assessed the proportion of patients in the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period who had all hormone tests (≥ 2 serum testosterone and LH and FSH concentrations), all laboratory tests (hormone tests and hematocrit), and all 5 guideline-recommended measures.

Analysis

Statistical comparisons between the proportions of patients in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods for each measure were performed using a χ2 test, without correction for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 10.0. A P value < .05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

Results

Chart review identified 189 patients in the pretemplate period and 113 patients in the posttemplate period with a new testosterone prescription (Figure). After exclusions, 91 and 49 patients, respectively, met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Fifty-six patients (62%) pretemplate and 40 patients (82%) posttemplate (P = .015) had approved PADRs and comprised the groups that were analyzed (Table 2).

The mean age and body mass index were similar in the pretemplate and posttemplate periods, but there was variation in the proportions of patients aged < 70 years and those with a body mass index < 30 between the groups. The most common diagnosis in both groups was testicular hypofunction, and the most common comorbidity was type 2 diabetes mellitus. Concomitant use of opioids or glucocorticoids that can lower testosterone levels was rare. Most testosterone prescriptions originated from primary care clinics in both periods: 68 (75%) in the pretemplate period and 35 (71%) in the posttemplate period. Most testosterone treatment was delivered by intramuscular injection.

In the posttemplate period vs pretemplate period, the proportion of patients with an approved PADR (82% vs 62%, P = .02), and documentation of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism (93% vs 71%, P = .002) prior to starting TRT were higher, while the percentage of patients having ≥ 2 testosterone measurements (85% vs 89%, P = .53), ≥ 1 testosterone level before 10 AM (78% vs 75%, P = .70), and hematocrit measured (95% vs 91%, P = .47) were similar. Rates of LH and FSH testing were higher in the posttemplate period (80%) vs the pretemplate period (63%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .07), and discussion of the risks and benefits of TRT was higher in the posttemplate period (58%) vs the pretemplate period (34%) (P = .02). The percentage of patients who had all hormone measurements (total and/or free testosterone, LH, and FSH) was higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (59%) but did not achieve statistical significance (P = .06). The rates of all guideline-recommended laboratory test orders were higher in the posttemplate period (78%) vs the pretemplate period (55%) (P = .03), and all 5 guideline-recommended clinical and laboratory measures were higher in the posttemplate period (45%) vs the pretemplate period (18%) (P = .004).

Discussion

The implementation of a pharmacy-managed TOT in CPRS demonstrated higher adherence to evidence-based guidelines for diagnosing and evaluating hypogonadism before TRT. After TOT implementation, a higher proportion of patients had documented signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency, underwent all recommended laboratory tests, and had discussions about the risks and benefits of TRT. Adherence to 5 clinical and laboratory measures recommended by Endocrine Society guidelines was higher after TOT implementation, indicating improved prescribing practices.4