User login

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the Military: Policy, Stigma, and Practical Solutions

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the Military: Policy, Stigma, and Practical Solutions

The impact of pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) on military service members and other uniformed professionals has been a topic of recent interest due to the announcement of the US Army’s new shaving rule in July 2025.1 The policy prohibits permanent shaving waivers, requires medical re-evaluation of shaving profiles within 90 days, and allows for administrative separation if a service member accumulates shaving exceptions totaling more than 12 months over a 24-month period.2 A common skin condition triggered or worsened by shaving, PFB causes painful bumps, pustules, and hyperpigmentation most often in the beard and cheek areas and negatively impacts quality of life. It disproportionately affects 45% to 83% of men in the United States, particularly those of African, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern descent.3,4 Genetic factors, particularly tightly coiled or coarse curly hair, can predispose individuals to PFB. The most successful treatment for PFB is to stop shaving, but this conflicts with military shaving standards and interferes with the use of protective equipment (eg, masks). Herein, we highlight the adverse impact of PFB on military career progression and provide context for clinicians who treat patients with PFB, especially as policies recently have shifted to allow nonmilitary clinicians to evaluate PFB in service members.5

Shaving Waivers and Advancement

Pseudofolliculitis barbae disproportionately prolongs the time to advancement of many service members, and those with PFB also are overburdened by policy changes related to shaving.6 In the US military, nearly 18% of the active-duty force is Black,7 a population that is more susceptible to PFB. Military personnel may request PFB-related accommodations, including medical shaving waivers that vary by branch. Through a formal documentation process, waivers allow service members to maintain facial hair up to one-quarter inch in length.5 Previously, waivers could be temporary (eg, up to 90 days) or permanent as subjectively determined based on clinician-documented disease severity. Almost 65% of US Air Force medical shaving waivers are held by Black men, and PFB is one of the most common reasons.6 Notably, the US Navy discontinued permanent shaving waivers in October 2019.8 A US Marine Corps policy issued in March 2025 now allows administrative separation of service members with PFB if symptoms do not improve after a 1-year medical shaving waiver due to “incompatibility with service.”9 This change reversed a 2022 policy that protected Marines from separation based on PFB.10 A Marine Corps spokesperson stated that this change aims to clarify how medical conditions can impact uniform compliance and standardize medical condition management while prioritizing compliance and duty readiness.1

Even in the absence of policy changes, obtaining a medical shaving waiver for PFB can be challenging. Service members may have little to no access to military dermatologists who specialize in management of PFB and experience long wait times for civilian network deferment. Service members seen in civilian clinics may have restricted treatment options due to limited insurance coverage for laser hair reduction, even in the most difficult-to-manage areas (eg, neck, jawline). Expanding access to military dermatologists, civilian dermatologists who are experienced with PFB and understand the impact and necessity of military waivers, and teledermatology services could help improve and streamline care. Other challenges include the subjective nature of documenting PFB disease severity, the need for validated assessment tools, a lack of standardized policies across military branches, and stigma. A standardized approach to documentation may reduce variability in how shaving waivers are evaluated across service branches, but at a minimum, clinicians should document the diagnosis, clinical findings, severity of PFB, and the treatment used. Having a waiver would help these service members focus on mastering critical skillsets and performing duties without the time pressures, angst, and expense dedicated to caring for and managing PFB.

Clinical and Policy Barriers

Unfortunately, service members with PFB or shaving waivers often face stigma that can hinder career advancement.6 In a recent analysis of 9339 US Air Force personnel, those with shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion compared to those without waivers: in the waiver group, 94.47% were enlisted and 5.53% were officers; in the nonwaiver group, 72.11% were enlisted and 27.89% were officers (P=.0003).6 While delays in promotion were consistent across racial groups, most of the waiver holders identified as Black (64.8%), despite this demographic group representing only a small portion of the overall cohort (12.9%).6 Promotion delays may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism and exclusion from high-profile assignments, which notably require “the highest standards of military appearance and professional conduct.”11 The burden of career-limiting shaving policies falls disproportionately on military personnel with PFB who self-identify as Black. Perceptions about unprofessional appearance or job readiness often unintentionally introduce bias, unjustly restricting career advancement.6

Safety Equipment and Shaving Standards

Conditions that potentially affect the use of masks and chemical defense equipment extend beyond the military. Firefighters and law enforcement officers generally are required to maintain a clean-shaven face for proper fit of respirator masks; the standard is that no respirator fit test shall be conducted if hair—including stubble, beards, mustaches, or sideburns—grows between the skin and the facepiece sealing surface, and any apparel interfering with a proper seal must be altered or removed.12 This creates challenges for uniformed professionals with PFB who must manage their condition while adhering to safety requirements. Some endure long-term pain and scarring in order to comply, while others seek waivers to treat and prevent symptoms while also facing the stigma of doing so.13 One of the most effective treatments for PFB is to discontinue shaving,14 which may not be feasible for those in uniformed professions with strict grooming standards. Research on mask seal effectiveness in individuals with neatly trimmed beards or PFB remains limited.5 Studies evaluating mask fit across facial hair types and lengths are needed, along with the development of protective equipment that accommodates career-limiting conditions such as PFB, cystic acne, and acne keloidalis nuchae. This also may encourage development of equipment that does not induce such conditions (eg, mechanical acne from friction). These efforts would promote safety, scientific innovation for dermatologic follicular-based disorders, and overall quality of life for service members as well as increase their ability to serve without stigma. These developments also would positively impact other fields that require intermittent or full-time use of masks, including health care and some food service industries.

Final Thoughts

The disproportionate impact of PFB in the military highlights the need for improved access to treatment, culturally informed care, and policies that avoid penalizing service members with tightly coiled hair and a desire to serve. We discussed PFB management strategies, clinical features, and implications across various skin tones in a previous publication.14 It is important to consider insights from individuals with PFB who are serving in the military as well as the medical personnel who care for them. Ensuring or creating effective treatment options drives innovation, and evidence-based accommodation plans can help individuals in uniformed professions avoid choosing between PFB management and their career. Promoting awareness about the impact of PFB beyond the razor is key to reducing disparities and supporting excellence among those who serve and desire to continue to do so.

- Lawrence DF. Marines with skin condition affecting mostly black men could now be booted under new policy. Military.com. March 14, 2025. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2025/03/14/marines-can-now-be-kicked-out-skin-condition-affects-mostly-black-men.html

- Secretary of the Army. Army directive 2025-13 (facial hair grooming standards). Published July 7, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://lyster.tricare.mil/Portals/61/ARN44307-ARMY_DIR_2025-13-000.pdf

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27. doi:10.1111/ics.12331

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302. doi:10.12788/cutis.0907

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab272

- Defense Manpower Data Center. Active-duty military personnel master file and reserve components common personnel data system. Military OneSource. September 2023. Accessed May 3, 2025. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2023-demographics-report.pdf

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US. Military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa243

- US Marine Corps. Uniform and grooming standards for medical conditions (MARADMINS number: 124/25). Published March 13, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/4119098/uniform-and-grooming-standards-for-medical-conditions/

- US Marine Corps. Advance notification of change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). Published January 21, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900/

- US Department of Defense. Special duty catalog (SPECAT). Published August 15, 2013. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://share.google/iuMrVMIASWx4EFLVN

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Appendix A to §1910.134—fit testing procedures (mandatory). Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195. doi:10.1017/jme.2023.55

- Welch D, Usatine R, Heath C. Implications of PFB beyond the razor. Cutis. 2025;115:135-136. doi:10.12788/cutis.1194

The impact of pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) on military service members and other uniformed professionals has been a topic of recent interest due to the announcement of the US Army’s new shaving rule in July 2025.1 The policy prohibits permanent shaving waivers, requires medical re-evaluation of shaving profiles within 90 days, and allows for administrative separation if a service member accumulates shaving exceptions totaling more than 12 months over a 24-month period.2 A common skin condition triggered or worsened by shaving, PFB causes painful bumps, pustules, and hyperpigmentation most often in the beard and cheek areas and negatively impacts quality of life. It disproportionately affects 45% to 83% of men in the United States, particularly those of African, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern descent.3,4 Genetic factors, particularly tightly coiled or coarse curly hair, can predispose individuals to PFB. The most successful treatment for PFB is to stop shaving, but this conflicts with military shaving standards and interferes with the use of protective equipment (eg, masks). Herein, we highlight the adverse impact of PFB on military career progression and provide context for clinicians who treat patients with PFB, especially as policies recently have shifted to allow nonmilitary clinicians to evaluate PFB in service members.5

Shaving Waivers and Advancement

Pseudofolliculitis barbae disproportionately prolongs the time to advancement of many service members, and those with PFB also are overburdened by policy changes related to shaving.6 In the US military, nearly 18% of the active-duty force is Black,7 a population that is more susceptible to PFB. Military personnel may request PFB-related accommodations, including medical shaving waivers that vary by branch. Through a formal documentation process, waivers allow service members to maintain facial hair up to one-quarter inch in length.5 Previously, waivers could be temporary (eg, up to 90 days) or permanent as subjectively determined based on clinician-documented disease severity. Almost 65% of US Air Force medical shaving waivers are held by Black men, and PFB is one of the most common reasons.6 Notably, the US Navy discontinued permanent shaving waivers in October 2019.8 A US Marine Corps policy issued in March 2025 now allows administrative separation of service members with PFB if symptoms do not improve after a 1-year medical shaving waiver due to “incompatibility with service.”9 This change reversed a 2022 policy that protected Marines from separation based on PFB.10 A Marine Corps spokesperson stated that this change aims to clarify how medical conditions can impact uniform compliance and standardize medical condition management while prioritizing compliance and duty readiness.1

Even in the absence of policy changes, obtaining a medical shaving waiver for PFB can be challenging. Service members may have little to no access to military dermatologists who specialize in management of PFB and experience long wait times for civilian network deferment. Service members seen in civilian clinics may have restricted treatment options due to limited insurance coverage for laser hair reduction, even in the most difficult-to-manage areas (eg, neck, jawline). Expanding access to military dermatologists, civilian dermatologists who are experienced with PFB and understand the impact and necessity of military waivers, and teledermatology services could help improve and streamline care. Other challenges include the subjective nature of documenting PFB disease severity, the need for validated assessment tools, a lack of standardized policies across military branches, and stigma. A standardized approach to documentation may reduce variability in how shaving waivers are evaluated across service branches, but at a minimum, clinicians should document the diagnosis, clinical findings, severity of PFB, and the treatment used. Having a waiver would help these service members focus on mastering critical skillsets and performing duties without the time pressures, angst, and expense dedicated to caring for and managing PFB.

Clinical and Policy Barriers

Unfortunately, service members with PFB or shaving waivers often face stigma that can hinder career advancement.6 In a recent analysis of 9339 US Air Force personnel, those with shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion compared to those without waivers: in the waiver group, 94.47% were enlisted and 5.53% were officers; in the nonwaiver group, 72.11% were enlisted and 27.89% were officers (P=.0003).6 While delays in promotion were consistent across racial groups, most of the waiver holders identified as Black (64.8%), despite this demographic group representing only a small portion of the overall cohort (12.9%).6 Promotion delays may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism and exclusion from high-profile assignments, which notably require “the highest standards of military appearance and professional conduct.”11 The burden of career-limiting shaving policies falls disproportionately on military personnel with PFB who self-identify as Black. Perceptions about unprofessional appearance or job readiness often unintentionally introduce bias, unjustly restricting career advancement.6

Safety Equipment and Shaving Standards

Conditions that potentially affect the use of masks and chemical defense equipment extend beyond the military. Firefighters and law enforcement officers generally are required to maintain a clean-shaven face for proper fit of respirator masks; the standard is that no respirator fit test shall be conducted if hair—including stubble, beards, mustaches, or sideburns—grows between the skin and the facepiece sealing surface, and any apparel interfering with a proper seal must be altered or removed.12 This creates challenges for uniformed professionals with PFB who must manage their condition while adhering to safety requirements. Some endure long-term pain and scarring in order to comply, while others seek waivers to treat and prevent symptoms while also facing the stigma of doing so.13 One of the most effective treatments for PFB is to discontinue shaving,14 which may not be feasible for those in uniformed professions with strict grooming standards. Research on mask seal effectiveness in individuals with neatly trimmed beards or PFB remains limited.5 Studies evaluating mask fit across facial hair types and lengths are needed, along with the development of protective equipment that accommodates career-limiting conditions such as PFB, cystic acne, and acne keloidalis nuchae. This also may encourage development of equipment that does not induce such conditions (eg, mechanical acne from friction). These efforts would promote safety, scientific innovation for dermatologic follicular-based disorders, and overall quality of life for service members as well as increase their ability to serve without stigma. These developments also would positively impact other fields that require intermittent or full-time use of masks, including health care and some food service industries.

Final Thoughts

The disproportionate impact of PFB in the military highlights the need for improved access to treatment, culturally informed care, and policies that avoid penalizing service members with tightly coiled hair and a desire to serve. We discussed PFB management strategies, clinical features, and implications across various skin tones in a previous publication.14 It is important to consider insights from individuals with PFB who are serving in the military as well as the medical personnel who care for them. Ensuring or creating effective treatment options drives innovation, and evidence-based accommodation plans can help individuals in uniformed professions avoid choosing between PFB management and their career. Promoting awareness about the impact of PFB beyond the razor is key to reducing disparities and supporting excellence among those who serve and desire to continue to do so.

The impact of pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) on military service members and other uniformed professionals has been a topic of recent interest due to the announcement of the US Army’s new shaving rule in July 2025.1 The policy prohibits permanent shaving waivers, requires medical re-evaluation of shaving profiles within 90 days, and allows for administrative separation if a service member accumulates shaving exceptions totaling more than 12 months over a 24-month period.2 A common skin condition triggered or worsened by shaving, PFB causes painful bumps, pustules, and hyperpigmentation most often in the beard and cheek areas and negatively impacts quality of life. It disproportionately affects 45% to 83% of men in the United States, particularly those of African, Hispanic, or Middle Eastern descent.3,4 Genetic factors, particularly tightly coiled or coarse curly hair, can predispose individuals to PFB. The most successful treatment for PFB is to stop shaving, but this conflicts with military shaving standards and interferes with the use of protective equipment (eg, masks). Herein, we highlight the adverse impact of PFB on military career progression and provide context for clinicians who treat patients with PFB, especially as policies recently have shifted to allow nonmilitary clinicians to evaluate PFB in service members.5

Shaving Waivers and Advancement

Pseudofolliculitis barbae disproportionately prolongs the time to advancement of many service members, and those with PFB also are overburdened by policy changes related to shaving.6 In the US military, nearly 18% of the active-duty force is Black,7 a population that is more susceptible to PFB. Military personnel may request PFB-related accommodations, including medical shaving waivers that vary by branch. Through a formal documentation process, waivers allow service members to maintain facial hair up to one-quarter inch in length.5 Previously, waivers could be temporary (eg, up to 90 days) or permanent as subjectively determined based on clinician-documented disease severity. Almost 65% of US Air Force medical shaving waivers are held by Black men, and PFB is one of the most common reasons.6 Notably, the US Navy discontinued permanent shaving waivers in October 2019.8 A US Marine Corps policy issued in March 2025 now allows administrative separation of service members with PFB if symptoms do not improve after a 1-year medical shaving waiver due to “incompatibility with service.”9 This change reversed a 2022 policy that protected Marines from separation based on PFB.10 A Marine Corps spokesperson stated that this change aims to clarify how medical conditions can impact uniform compliance and standardize medical condition management while prioritizing compliance and duty readiness.1

Even in the absence of policy changes, obtaining a medical shaving waiver for PFB can be challenging. Service members may have little to no access to military dermatologists who specialize in management of PFB and experience long wait times for civilian network deferment. Service members seen in civilian clinics may have restricted treatment options due to limited insurance coverage for laser hair reduction, even in the most difficult-to-manage areas (eg, neck, jawline). Expanding access to military dermatologists, civilian dermatologists who are experienced with PFB and understand the impact and necessity of military waivers, and teledermatology services could help improve and streamline care. Other challenges include the subjective nature of documenting PFB disease severity, the need for validated assessment tools, a lack of standardized policies across military branches, and stigma. A standardized approach to documentation may reduce variability in how shaving waivers are evaluated across service branches, but at a minimum, clinicians should document the diagnosis, clinical findings, severity of PFB, and the treatment used. Having a waiver would help these service members focus on mastering critical skillsets and performing duties without the time pressures, angst, and expense dedicated to caring for and managing PFB.

Clinical and Policy Barriers

Unfortunately, service members with PFB or shaving waivers often face stigma that can hinder career advancement.6 In a recent analysis of 9339 US Air Force personnel, those with shaving waivers experienced longer times to promotion compared to those without waivers: in the waiver group, 94.47% were enlisted and 5.53% were officers; in the nonwaiver group, 72.11% were enlisted and 27.89% were officers (P=.0003).6 While delays in promotion were consistent across racial groups, most of the waiver holders identified as Black (64.8%), despite this demographic group representing only a small portion of the overall cohort (12.9%).6 Promotion delays may be linked to perceptions of unprofessionalism and exclusion from high-profile assignments, which notably require “the highest standards of military appearance and professional conduct.”11 The burden of career-limiting shaving policies falls disproportionately on military personnel with PFB who self-identify as Black. Perceptions about unprofessional appearance or job readiness often unintentionally introduce bias, unjustly restricting career advancement.6

Safety Equipment and Shaving Standards

Conditions that potentially affect the use of masks and chemical defense equipment extend beyond the military. Firefighters and law enforcement officers generally are required to maintain a clean-shaven face for proper fit of respirator masks; the standard is that no respirator fit test shall be conducted if hair—including stubble, beards, mustaches, or sideburns—grows between the skin and the facepiece sealing surface, and any apparel interfering with a proper seal must be altered or removed.12 This creates challenges for uniformed professionals with PFB who must manage their condition while adhering to safety requirements. Some endure long-term pain and scarring in order to comply, while others seek waivers to treat and prevent symptoms while also facing the stigma of doing so.13 One of the most effective treatments for PFB is to discontinue shaving,14 which may not be feasible for those in uniformed professions with strict grooming standards. Research on mask seal effectiveness in individuals with neatly trimmed beards or PFB remains limited.5 Studies evaluating mask fit across facial hair types and lengths are needed, along with the development of protective equipment that accommodates career-limiting conditions such as PFB, cystic acne, and acne keloidalis nuchae. This also may encourage development of equipment that does not induce such conditions (eg, mechanical acne from friction). These efforts would promote safety, scientific innovation for dermatologic follicular-based disorders, and overall quality of life for service members as well as increase their ability to serve without stigma. These developments also would positively impact other fields that require intermittent or full-time use of masks, including health care and some food service industries.

Final Thoughts

The disproportionate impact of PFB in the military highlights the need for improved access to treatment, culturally informed care, and policies that avoid penalizing service members with tightly coiled hair and a desire to serve. We discussed PFB management strategies, clinical features, and implications across various skin tones in a previous publication.14 It is important to consider insights from individuals with PFB who are serving in the military as well as the medical personnel who care for them. Ensuring or creating effective treatment options drives innovation, and evidence-based accommodation plans can help individuals in uniformed professions avoid choosing between PFB management and their career. Promoting awareness about the impact of PFB beyond the razor is key to reducing disparities and supporting excellence among those who serve and desire to continue to do so.

- Lawrence DF. Marines with skin condition affecting mostly black men could now be booted under new policy. Military.com. March 14, 2025. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2025/03/14/marines-can-now-be-kicked-out-skin-condition-affects-mostly-black-men.html

- Secretary of the Army. Army directive 2025-13 (facial hair grooming standards). Published July 7, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://lyster.tricare.mil/Portals/61/ARN44307-ARMY_DIR_2025-13-000.pdf

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27. doi:10.1111/ics.12331

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302. doi:10.12788/cutis.0907

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab272

- Defense Manpower Data Center. Active-duty military personnel master file and reserve components common personnel data system. Military OneSource. September 2023. Accessed May 3, 2025. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2023-demographics-report.pdf

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US. Military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa243

- US Marine Corps. Uniform and grooming standards for medical conditions (MARADMINS number: 124/25). Published March 13, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/4119098/uniform-and-grooming-standards-for-medical-conditions/

- US Marine Corps. Advance notification of change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). Published January 21, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900/

- US Department of Defense. Special duty catalog (SPECAT). Published August 15, 2013. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://share.google/iuMrVMIASWx4EFLVN

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Appendix A to §1910.134—fit testing procedures (mandatory). Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195. doi:10.1017/jme.2023.55

- Welch D, Usatine R, Heath C. Implications of PFB beyond the razor. Cutis. 2025;115:135-136. doi:10.12788/cutis.1194

- Lawrence DF. Marines with skin condition affecting mostly black men could now be booted under new policy. Military.com. March 14, 2025. Accessed May 4, 2025. https://www.military.com/daily-news/2025/03/14/marines-can-now-be-kicked-out-skin-condition-affects-mostly-black-men.html

- Secretary of the Army. Army directive 2025-13 (facial hair grooming standards). Published July 7, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://lyster.tricare.mil/Portals/61/ARN44307-ARMY_DIR_2025-13-000.pdf

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27. doi:10.1111/ics.12331

- Jung I, Lannan FM, Weiss A, et al. Treatment and current policies on pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US military. Cutis. 2023;112:299-302. doi:10.12788/cutis.0907

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab272

- Defense Manpower Data Center. Active-duty military personnel master file and reserve components common personnel data system. Military OneSource. September 2023. Accessed May 3, 2025. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2023-demographics-report.pdf

- Tshudy MT, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the US. Military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:E52-E57. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa243

- US Marine Corps. Uniform and grooming standards for medical conditions (MARADMINS number: 124/25). Published March 13, 2025. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/4119098/uniform-and-grooming-standards-for-medical-conditions/

- US Marine Corps. Advance notification of change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). Published January 21, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900/

- US Department of Defense. Special duty catalog (SPECAT). Published August 15, 2013. Accessed September 19, 2025. https://share.google/iuMrVMIASWx4EFLVN

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Appendix A to §1910.134—fit testing procedures (mandatory). Accessed September 19, 2025. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- Jiang YR. Reasonable accommodation and disparate impact: clean shave policy discrimination in today’s workplace. J Law Med Ethics. 2023;51:185-195. doi:10.1017/jme.2023.55

- Welch D, Usatine R, Heath C. Implications of PFB beyond the razor. Cutis. 2025;115:135-136. doi:10.12788/cutis.1194

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the Military: Policy, Stigma, and Practical Solutions

Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the Military: Policy, Stigma, and Practical Solutions

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

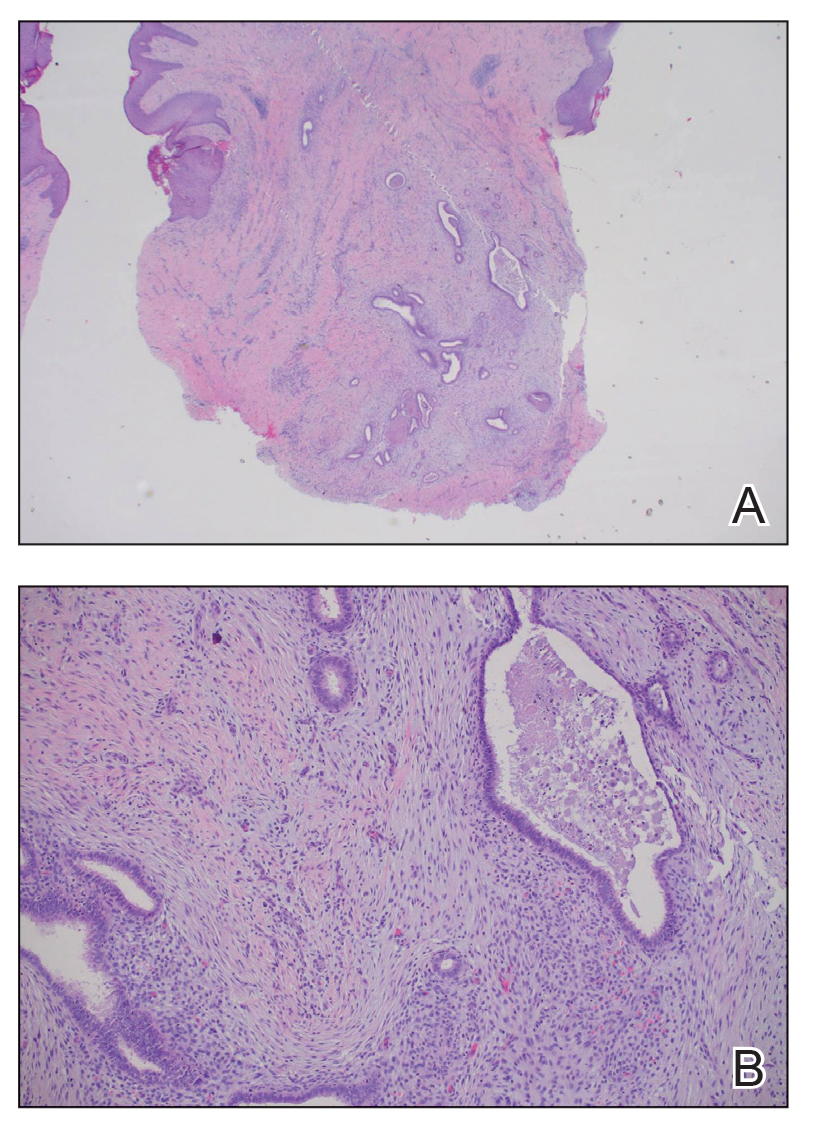

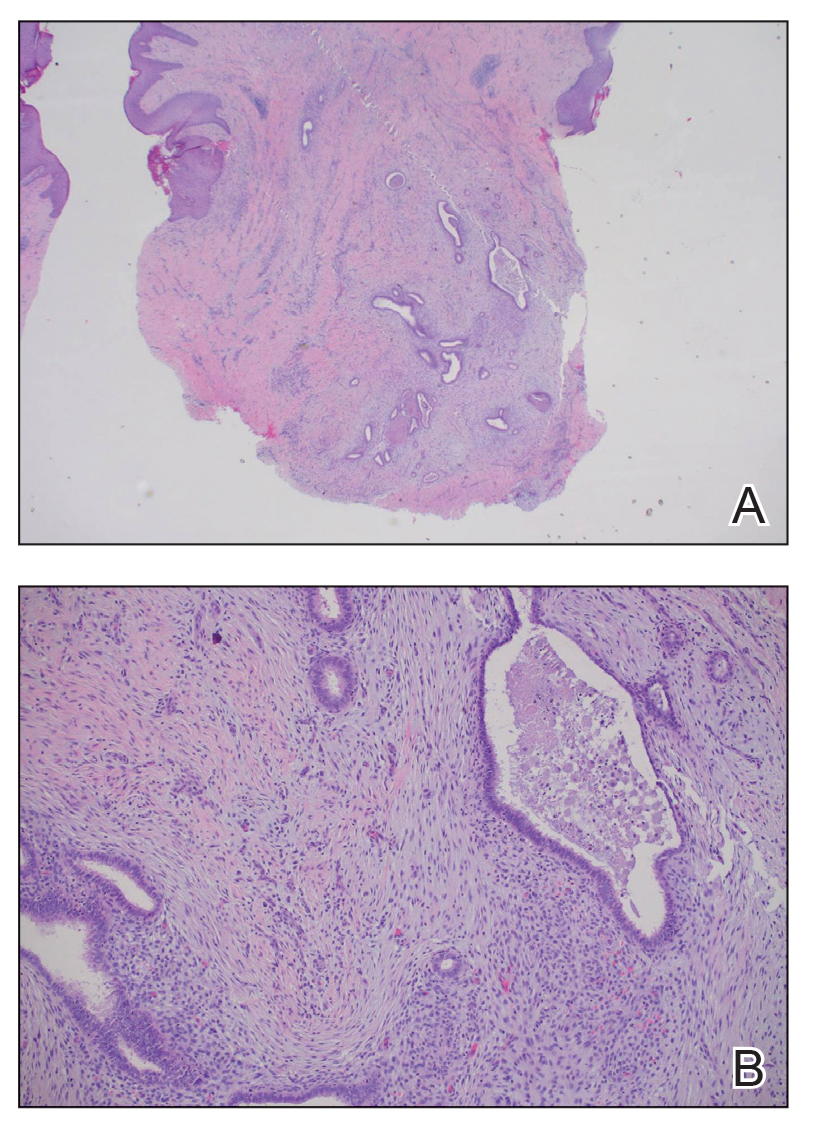

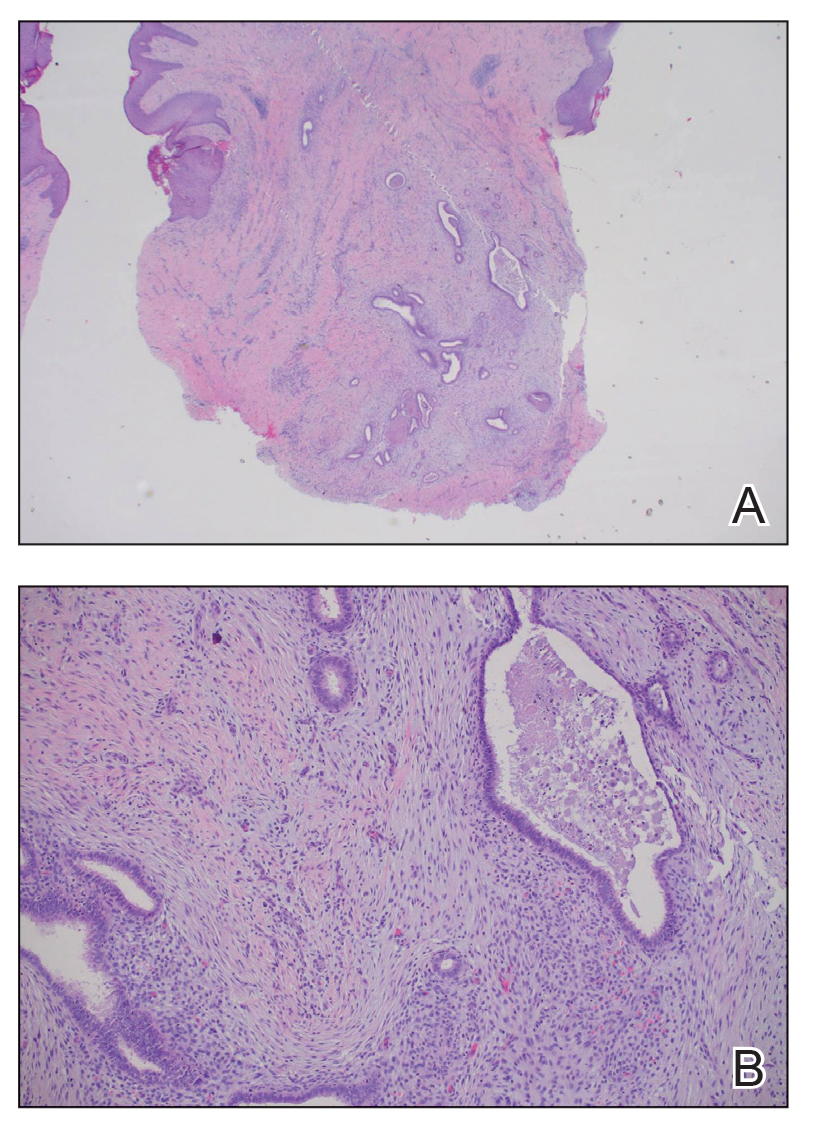

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

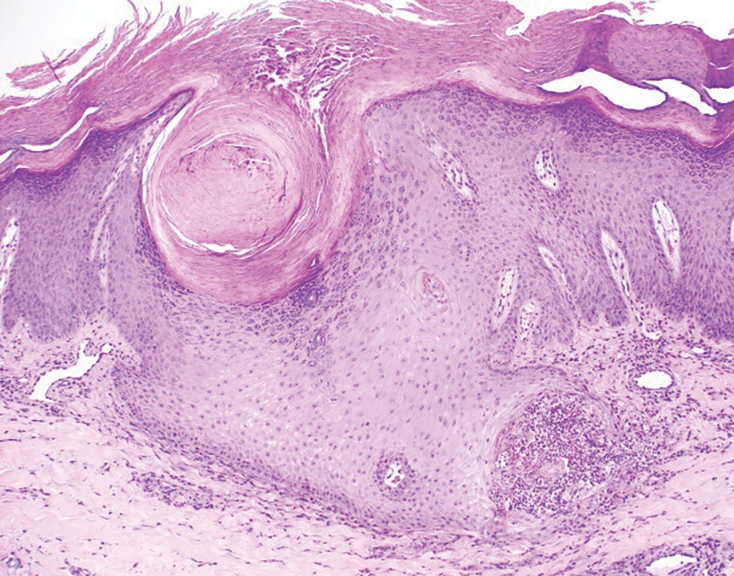

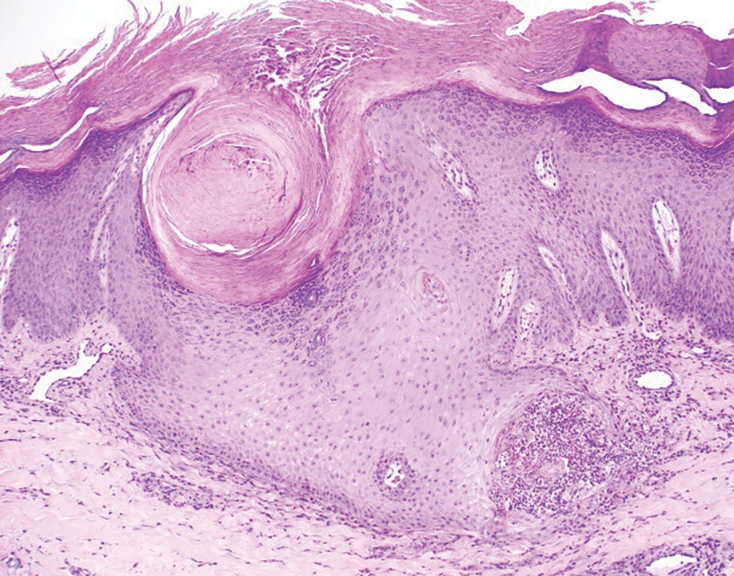

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- International Working Group of AAGL, ESGE, ESHRE and WES; Tomassetti C, Johnson NP, et al. An international terminology for endometriosis, 2021. Hum Reprod Open. 2021;2021:hoab029. doi:10.1093/hropen/hoab029

- Batista M, Alves F, Cardoso J, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: a differential diagnosis of umbilical nodule. Acta Med Port. 2020; 33:282-284. doi:10.20344/amp.10966

- Brown ME, Osswald S, Biediger T. Cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus (Villar’s nodule). Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;6:214-215. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2020.01.001

- Bindra V, Sampurna S, Kade S, et al. Primary umbilical endometriosis - case series and review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;94:107134. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107134

- Loh SH, Lew BL, Sim WY. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:621-625. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621

- Victory R, Diamond MP, Johns DA. Villar’s nodule: a case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23-32. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.01

- Van den Nouland D, Kaur M. Primary umbilical endometriosis: a case report. Facts Views Vis Obgyn. 2017;9:115-119.

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194. doi:10.1186/1746-1596-8-194

- Huang QF, Jiang B, Yang X, et al. Primary versus secondary cutaneous endometriosis: literature review and case study. Heliyon. 2023;9:E20094. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20094

- Gonzalez RH, Singh MS, Hamza SA. Cutaneous endometriosis: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:E932493. doi:10.12659/AJCR.932493

- Buljan M, Arzberger E, Šitum M, et al. The use of dermoscopy in differentiating Sister Mary Joseph nodule and cutaneous endometriosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60:E233-E235. doi:10.1111/ajd.12980

- Costa IM, Gomes CM, Morais OO, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis: dermoscopic findings related to phases of the female hormonal cycle. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E130-E132. doi:10.1111 /j.1365-4632.2012.05854.x

- Mohaghegh F, Hatami P, Rajabi P, et al. Coexistence of cutaneous endometriosis and ovarian endometrioma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:256. doi:10.1186/s13256-022-03483-8

- Raffi L, Suresh R, McCalmont TH, et al. Cutaneous endometriosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:384-386. doi:10.1016 /j.ijwd.2019.06.025

- Saunders PTK, Horne AW. Endometriosis: etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects. Cell. 2021;184:2807-2824. doi:10.1016 /j.cell.2021.04.041

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. St. Louis, Mo. Elsevier; 2016.

- Patrice SJ, Wiss K, Mulliken JB. Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma): a clinicopathologic study of 178 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:267-276. doi:10.1111/j.15251470.1991.tb00931.x

- Kaleeny JD, Janis JE. Pyogenic granuloma diagnosis and management: a practical review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2024;12:E6160. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000006160

- Ha DL, Yang MY, Shin JO, et al. Benign umbilical tumors resembling Sister Mary Joseph nodule. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021;15:1179554921995022. doi:10.1177/1179554921995022

- Lawrence PF, Smeds M, Jessica Beth O’connell. Essentials of General Surgery and Surgical Specialties. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2019.

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752. doi:10.3390/jcm9061752

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

A 25-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology clinic by her primary care provider for evaluation of a tender nodule on the inferior umbilicus of 2 years' duration at the site of a preexisting keloid scar. The patient reported that the lesion caused occasional pain and tenderness. A few weeks prior to the current presentation, a dark-red bloody discharge developed at the superior aspect of the lesion that subsequently crusted over. The patient denied any use of oral contraceptives or history of abdominal surgery.

The original keloid scar had been treated successfully by an outside physician with intralesional steroid injections, and the patient was interested in a similar procedure for the current nodule. She also had a history of a hyperpigmented hypertrophic scar on the superior periumbilical area from a previous piercing that had resolved several years prior to presentation.

Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 1.2-cm, soft, tender, violaceous nodule with scant yellow crust along the superior surface of the umbilicus. There was no palpable abdominal wall defect, and the nodule was not reducible into the abdominal cavity. An interval history revealed bleeding of the lesion during the patient's menstrual cycle with persistent pain and tenderness. A punch biopsy was performed.

Diffuse Pruritic Keratotic Papules

Diffuse Pruritic Keratotic Papules

THE DIAGNOSIS: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

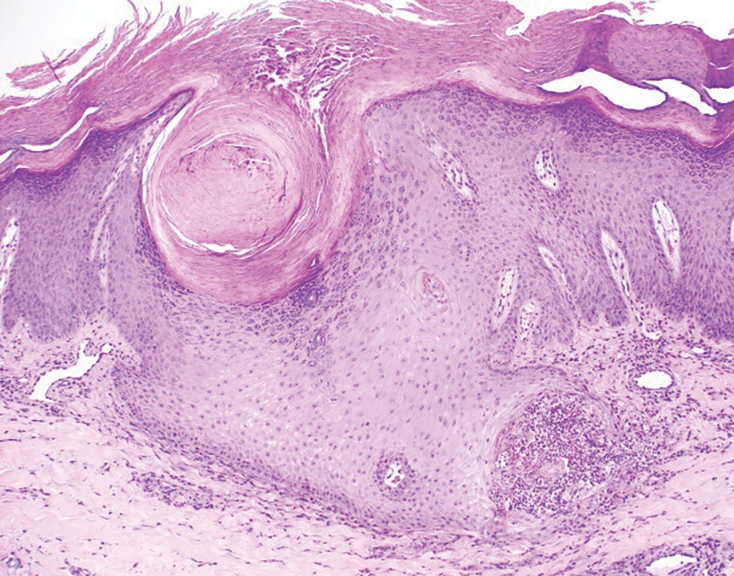

Histopathology revealed invagination of the epidermis with hyperkeratosis; prominent epidermal hyperplasia; and a central basophilic plug of keratin, collagen, and inflammatory debris. Transepidermal elimination of bright eosinophilic altered collagen fibers was seen (Figure). The findings were consistent with a diagnosis of reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC).

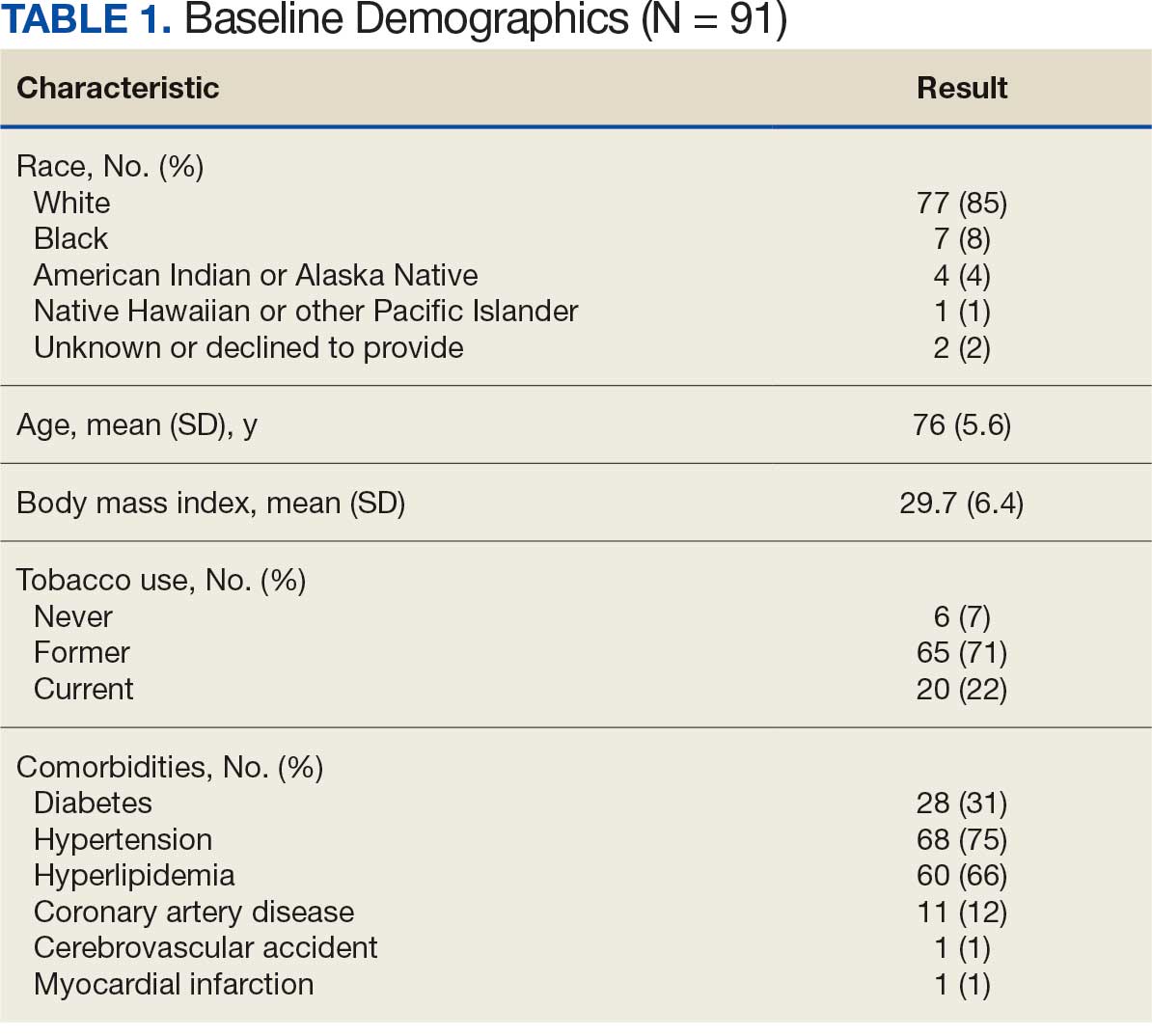

Reactive perforating collagenosis, a subtype of perforating dermatosis, is a rare skin condition in which altered collagen is eliminated through the epidermis.1 There are 2 forms of RPC: the inherited form, which is very rare and manifests in childhood, and the acquired form, which manifests in adulthood and is associated with systemic diseases, most notably diabetes and/or chronic renal failure, both of which our patient had been diagnosed with.1,2 The clinical presentation of RPC includes erythematous papules or nodules that evolve into umbilicated 4- to 10-mm craterlike ulcerations with a central keratotic plug. The lesions favor a linear distribution along the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, trunk, and gluteal area. Involvement of the head, neck, and scalp has been reported less commonly, which makes our case particularly unique.3 Histopathologically, RPC is characterized by a cup-shaped depression of the epidermis with an overlying keratin plug containing inflammatory cells, keratinous debris, and collagen fibers. Vertically oriented collagen fibers are seen extruded through the epidermis.4,5

While the pathogenesis of RPC remains unknown, it is believed that superficial trauma due to chronic scratching results in transepithelial elimination of collagen. Due to the association of acquired RPC (ARPC) with diabetes, it also has been proposed that scratching can cause microtrauma and necrosis of the dermal structures, potentially due to diabetic microangiopathy.3 Additionally, RPC is associated with overexpression of transforming growth factor beta 3 in lesional skin, suggesting that transforming growth factor beta 3 is involved with tissue repair and extracellular remodeling in this condition.6

Treatment of ARPC should include the management of underlying disease. While no definitive treatment has been reported to date, topical corticosteroids, retinoids, keratolytics, emollients, antihistamines, narrow-band UVB phototherapy, and psoralen plus UVA phototherapy have been used with varying degrees of improvement. Typically, the lesions self-resolve within 6 to 8 weeks; however, they often recur and usually leave scarring with or without hyperpigmentation.2,7-10

Acquired RPC can be misdiagnosed initially, as it mimics several other conditions and commonly is associated with systemic diseases. While biopsy is necessary for diagnosis, if it cannot be performed or the results are indeterminate, dermoscopy can serve as a helpful diagnostic tool. The most common dermoscopic patterns seen in RPC include a yellow-brown structureless area in the center of the lesion with a peripheral surface crust and surrounding white rim—thought to represent epidermal invagination or keratinous debris. Additionally, inflammation with visible vessels both centrally and peripherally is represented by an outer pink circle on dermoscopy.5,11

The differential diagnoses for RPC include perforating folliculitis (PF), elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS), prurigo nodularis, and keratoacanthomas. The primary perforating dermatoses (PF, EPS, and RPC) are similarly characterized by elimination of altered dermal material through the epidermis. As these conditions manifest with similar features on clinical examination, differentiation is made by the type of epidermal damage and the features of elimination material, making histopathologic examination paramount for definitive diagnosis.

Perforating folliculitis manifests as erythematous, follicular papules with a small central keratotic core or a central hair. Histopathologically, PF reveals a widely dilated follicle containing keratin, necrotic debris, and degenerated inflammatory cells. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa manifests clinically as hyperkeratotic papules in serpiginous patterns rather than the linear pattern commonly seen with ARPC. Histopathologically, EPS reveals thickened elastic fibers, rather than collagen fibers as seen in ARPC, extruded through the epidermis. Prurigo nodularis manifests clinically as dome-shaped papules with possible excoriation and crusting. Histopathologic examination reveals epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis; however, the characteristic features of transepithelial elimination of collagen and invaginations of epidermis differentiate ARPC from prurigo nodularis.12,13 Keratoacanthomas manifest clinically as an eruption of small, round, pink papules that rapidly grow and evolve into 1- to 2-cm dome-shaped nodules with central keratinaceous plugs, mimicking a crateriform appearance. Histopathologic examination reveals a circumscribed proliferation of well-differentiated keratinocytes. Multilobular exophytic or endophytic cystlike invaginations of the epidermis also are noted. The expulsion of collagen from the epidermis is more consistent with ARPC.14

- Cohen RW, Auerbach R. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):287-289. doi:10.1016/s0190 -9622(89)80059-3

- Bejjanki H, Siroy AE, Koratala A. Reactive perforating collagenosis in end-stage renal disease: not all that itches is uremic pruritis! Am J Med. 2019;132:E658-E660. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.03.015

- Gontijo JRV, Júnior FF, Pereira LB, et al. Trauma-induced acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:392-393. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.06.022

- Ambalathinkal JJ, Phiske MM, Someshwar SJ. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis, a rare entity at uncommon site. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65:895-897. doi:10.4103/ijpm.ijpm_333_21

- Ormerod E, Atwan A, Intzedy L, et al. Dermoscopy features of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a case series. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:303-305. doi:10.5826/dpc.0804a11

- Fei C, Wang Y, Gong Y, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: a report of a typical case. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:E4305. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004305

- Bartling SJ, Naff JL, Canevari MM, et al. Pruritic rash in an elderly patient with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2018;5:E146-E149. doi:10.4158/ACCR-2018-0388

- Kollipara H, Satya RS, Rao GR, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: case series. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2023;14:72-76. doi:10.4103/idoj.idoj_373_22

- Wang C, Liu YH, Wang YX, et al. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:2119-2120. doi:10.1097 /cm9.0000000000000906

- Harbaoui S, Litaiem N. Acquired perforating dermatosis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 13, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539715/

- Elmas ÖF, Kilitci A, Uyar B. Dermoscopic patterns of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2020085. doi:10.5826/dpc.1101a85

- Patterson JW. The perforating disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:561-581. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80259-5

- Huang AH, Williams KA, Kwatra SG. Prurigo nodularis: epidemiology and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1559-1565. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.183

- Zito PM, Scharf R. Keratoacanthoma. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed August 13, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499931/

THE DIAGNOSIS: Reactive Perforating Collagenosis