User login

Finding Fulfillment Beyond Metrics: A Physician’s Path to Lasting Well-Being

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad shares her personal experience with burnout and the journey to recovery through coaching and self-compassion. She describes the pressures of seeking validation through external achievements, which ultimately led to a crisis in self-worth after medical training. Through coaching, she learned to cultivate a sense of internal fulfillment, reconnecting with her passion for medicine and achieving a healthier balance.

Key Takeaways:

- Relying solely on external validation can deepen burnout and affect well-being.

- Coaching empowers physicians to develop self-compassion and sustainable coping strategies.

- Shifting from external to internal validation strengthens long-term fulfillment and job satisfaction.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad shares her personal experience with burnout and the journey to recovery through coaching and self-compassion. She describes the pressures of seeking validation through external achievements, which ultimately led to a crisis in self-worth after medical training. Through coaching, she learned to cultivate a sense of internal fulfillment, reconnecting with her passion for medicine and achieving a healthier balance.

Key Takeaways:

- Relying solely on external validation can deepen burnout and affect well-being.

- Coaching empowers physicians to develop self-compassion and sustainable coping strategies.

- Shifting from external to internal validation strengthens long-term fulfillment and job satisfaction.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Summary and Key Highlights

Summary: Dr Tyra Fainstad shares her personal experience with burnout and the journey to recovery through coaching and self-compassion. She describes the pressures of seeking validation through external achievements, which ultimately led to a crisis in self-worth after medical training. Through coaching, she learned to cultivate a sense of internal fulfillment, reconnecting with her passion for medicine and achieving a healthier balance.

Key Takeaways:

- Relying solely on external validation can deepen burnout and affect well-being.

- Coaching empowers physicians to develop self-compassion and sustainable coping strategies.

- Shifting from external to internal validation strengthens long-term fulfillment and job satisfaction.

Our Editors Also Recommend:

Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024: ‘We Have Much Work to Do’

Medscape Hospitalist Burnout & Depression Report 2024: Seeking Progress, Balance

Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2024: The Ongoing Struggle for Balance

A Transformative Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

Next Medscape Masters Event:

Stay at the forefront of obesity care. Register for exclusive insights and the latest treatment innovations.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To Hold or Not to Hold GLP-1s Before Surgery

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Recently, there have been two somewhat conflicting recommendations about how to deal with our patients who are on incretin hormone therapy before undergoing elective surgical procedures.

First, the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] has updated the package inserts for all of these incretins, meaning the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic (GIP)/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide, with a warning about pulmonary aspiration during general anesthesia or deep sedation. They instruct patients to let healthcare providers know of any planned surgeries or procedures. This has come about because of postmarketing experience in which patients who are on GLP-1 receptor agonists have had residual gastric contents found despite reported adherence to preoperative fasting recommendations.

The problem with this is that the FDA says they don’t really actually know what to tell us to do or not to do because we don’t have knowledge as to how to truly mitigate the risk for pulmonary aspiration during general anesthesia or deep sedation. They don’t know if modifying preoperative fasting recommendations should be changed or if temporary discontinuation of the drugs could reduce this problem. They really don’t know what to tell us to do except to tell us that this is a problem we should discuss with our patients.

At about the same time, a society guideline— and this was from a number of different societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists — stated that most patients should continue taking their GLP-1 receptor agonist before elective surgery.

This struck me as somewhat discordant from what the FDA said, although the FDA also says they don’t know quite what to tell us to do. This clinical guideline goes into a bit more detail, and what they think might be a good idea is that patients who are at the highest risk for GI side effects should follow a liquid diet for 24 hours before the procedure.

They basically look at who is at highest risk, and they say the following: Patients in the escalation phase of their incretin therapy — that is, early in treatment when the dose is increasing — are most likely to have delays in gastric emptying because that effect is lessened over time. They say that the elective surgery should be deferred until the escalation phase has passed and the GI symptoms have dissipated.

They’re very clear that patients who have significant GI symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and shortness of breath, should wait until their symptoms have dissipated.

They think this is something that would be good no matter what dose of drug these patients are on. They do say that you tend to see more issues with gastric emptying in patients at the highest dose of a GLP-1 receptor agonist. They also mention other medical conditions that may slow gastric emptying, such as Parkinson’s disease, which may further modify the perioperative management plan.

Their proposed solutions that sort of correspond with my proposed solutions include assessing the patient. Obviously, if a patient is going up on the dose of these drugs or having many GI side effects, that’s someone who you probably don’t want to send for elective surgery if you don’t have to. However, if you need to — and possibly in everybody — you might want to withhold the drug for 10-14 days preoperatively to make sure they don’t have significant GI side effects as they’re preparing for their procedure.

One of the things the anesthesiology group was worried about was that glucose levels would go up and patients would have hyperglycemia going into surgery. I’m not so worried about holding a dose or two of one of these agents. I don’t see much hyperglycemia occurring. If it does, you can treat it in other ways.

If it’s somebody where you think they’re having symptoms but they want to have the procedure anyway, you can put them on a liquid diet for 24 hours or so, so that there’s less of a risk for retained gastric contents, at least solid gastric contents. Anesthesiologists can help with this as well because in many cases, they can do a point-of-care gastric ultrasound to check for retained food or fluid.

I know this is sort of vague because I don’t have clear recommendations, but I do think it’s important to talk with your patients to assess whether they’re having signs or symptoms of gastroparesis. I think it’s not unreasonable to hold the incretin hormone therapy for one or two doses before a procedure if you have that opportunity, and be sure that the anesthesiologist and surgery team are aware of the fact that the patient has been on one of these agents so that they’re a little more aware of the risk for aspiration.

Anne L. Peters, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Keck School of Medicine; Director, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) on the advisory board for Abbott Diabetes Care; Becton Dickinson; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Livongo; Medscape; Merck & Co., Inc.; Novo Nordisk; Omada Health; OptumHealth; sanofi; Zafgen Received research support from: Dexcom; MannKind Corporation; Astra Zeneca. Serve(d) as a member of a speakers bureau for: Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Recently, there have been two somewhat conflicting recommendations about how to deal with our patients who are on incretin hormone therapy before undergoing elective surgical procedures.

First, the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] has updated the package inserts for all of these incretins, meaning the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic (GIP)/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide, with a warning about pulmonary aspiration during general anesthesia or deep sedation. They instruct patients to let healthcare providers know of any planned surgeries or procedures. This has come about because of postmarketing experience in which patients who are on GLP-1 receptor agonists have had residual gastric contents found despite reported adherence to preoperative fasting recommendations.

The problem with this is that the FDA says they don’t really actually know what to tell us to do or not to do because we don’t have knowledge as to how to truly mitigate the risk for pulmonary aspiration during general anesthesia or deep sedation. They don’t know if modifying preoperative fasting recommendations should be changed or if temporary discontinuation of the drugs could reduce this problem. They really don’t know what to tell us to do except to tell us that this is a problem we should discuss with our patients.

At about the same time, a society guideline— and this was from a number of different societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists — stated that most patients should continue taking their GLP-1 receptor agonist before elective surgery.

This struck me as somewhat discordant from what the FDA said, although the FDA also says they don’t know quite what to tell us to do. This clinical guideline goes into a bit more detail, and what they think might be a good idea is that patients who are at the highest risk for GI side effects should follow a liquid diet for 24 hours before the procedure.

They basically look at who is at highest risk, and they say the following: Patients in the escalation phase of their incretin therapy — that is, early in treatment when the dose is increasing — are most likely to have delays in gastric emptying because that effect is lessened over time. They say that the elective surgery should be deferred until the escalation phase has passed and the GI symptoms have dissipated.

They’re very clear that patients who have significant GI symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and shortness of breath, should wait until their symptoms have dissipated.

They think this is something that would be good no matter what dose of drug these patients are on. They do say that you tend to see more issues with gastric emptying in patients at the highest dose of a GLP-1 receptor agonist. They also mention other medical conditions that may slow gastric emptying, such as Parkinson’s disease, which may further modify the perioperative management plan.

Their proposed solutions that sort of correspond with my proposed solutions include assessing the patient. Obviously, if a patient is going up on the dose of these drugs or having many GI side effects, that’s someone who you probably don’t want to send for elective surgery if you don’t have to. However, if you need to — and possibly in everybody — you might want to withhold the drug for 10-14 days preoperatively to make sure they don’t have significant GI side effects as they’re preparing for their procedure.

One of the things the anesthesiology group was worried about was that glucose levels would go up and patients would have hyperglycemia going into surgery. I’m not so worried about holding a dose or two of one of these agents. I don’t see much hyperglycemia occurring. If it does, you can treat it in other ways.

If it’s somebody where you think they’re having symptoms but they want to have the procedure anyway, you can put them on a liquid diet for 24 hours or so, so that there’s less of a risk for retained gastric contents, at least solid gastric contents. Anesthesiologists can help with this as well because in many cases, they can do a point-of-care gastric ultrasound to check for retained food or fluid.

I know this is sort of vague because I don’t have clear recommendations, but I do think it’s important to talk with your patients to assess whether they’re having signs or symptoms of gastroparesis. I think it’s not unreasonable to hold the incretin hormone therapy for one or two doses before a procedure if you have that opportunity, and be sure that the anesthesiologist and surgery team are aware of the fact that the patient has been on one of these agents so that they’re a little more aware of the risk for aspiration.

Anne L. Peters, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Keck School of Medicine; Director, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) on the advisory board for Abbott Diabetes Care; Becton Dickinson; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Livongo; Medscape; Merck & Co., Inc.; Novo Nordisk; Omada Health; OptumHealth; sanofi; Zafgen Received research support from: Dexcom; MannKind Corporation; Astra Zeneca. Serve(d) as a member of a speakers bureau for: Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Recently, there have been two somewhat conflicting recommendations about how to deal with our patients who are on incretin hormone therapy before undergoing elective surgical procedures.

First, the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] has updated the package inserts for all of these incretins, meaning the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and the dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic (GIP)/GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide, with a warning about pulmonary aspiration during general anesthesia or deep sedation. They instruct patients to let healthcare providers know of any planned surgeries or procedures. This has come about because of postmarketing experience in which patients who are on GLP-1 receptor agonists have had residual gastric contents found despite reported adherence to preoperative fasting recommendations.

The problem with this is that the FDA says they don’t really actually know what to tell us to do or not to do because we don’t have knowledge as to how to truly mitigate the risk for pulmonary aspiration during general anesthesia or deep sedation. They don’t know if modifying preoperative fasting recommendations should be changed or if temporary discontinuation of the drugs could reduce this problem. They really don’t know what to tell us to do except to tell us that this is a problem we should discuss with our patients.

At about the same time, a society guideline— and this was from a number of different societies, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists — stated that most patients should continue taking their GLP-1 receptor agonist before elective surgery.

This struck me as somewhat discordant from what the FDA said, although the FDA also says they don’t know quite what to tell us to do. This clinical guideline goes into a bit more detail, and what they think might be a good idea is that patients who are at the highest risk for GI side effects should follow a liquid diet for 24 hours before the procedure.

They basically look at who is at highest risk, and they say the following: Patients in the escalation phase of their incretin therapy — that is, early in treatment when the dose is increasing — are most likely to have delays in gastric emptying because that effect is lessened over time. They say that the elective surgery should be deferred until the escalation phase has passed and the GI symptoms have dissipated.

They’re very clear that patients who have significant GI symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and shortness of breath, should wait until their symptoms have dissipated.

They think this is something that would be good no matter what dose of drug these patients are on. They do say that you tend to see more issues with gastric emptying in patients at the highest dose of a GLP-1 receptor agonist. They also mention other medical conditions that may slow gastric emptying, such as Parkinson’s disease, which may further modify the perioperative management plan.

Their proposed solutions that sort of correspond with my proposed solutions include assessing the patient. Obviously, if a patient is going up on the dose of these drugs or having many GI side effects, that’s someone who you probably don’t want to send for elective surgery if you don’t have to. However, if you need to — and possibly in everybody — you might want to withhold the drug for 10-14 days preoperatively to make sure they don’t have significant GI side effects as they’re preparing for their procedure.

One of the things the anesthesiology group was worried about was that glucose levels would go up and patients would have hyperglycemia going into surgery. I’m not so worried about holding a dose or two of one of these agents. I don’t see much hyperglycemia occurring. If it does, you can treat it in other ways.

If it’s somebody where you think they’re having symptoms but they want to have the procedure anyway, you can put them on a liquid diet for 24 hours or so, so that there’s less of a risk for retained gastric contents, at least solid gastric contents. Anesthesiologists can help with this as well because in many cases, they can do a point-of-care gastric ultrasound to check for retained food or fluid.

I know this is sort of vague because I don’t have clear recommendations, but I do think it’s important to talk with your patients to assess whether they’re having signs or symptoms of gastroparesis. I think it’s not unreasonable to hold the incretin hormone therapy for one or two doses before a procedure if you have that opportunity, and be sure that the anesthesiologist and surgery team are aware of the fact that the patient has been on one of these agents so that they’re a little more aware of the risk for aspiration.

Anne L. Peters, Professor, Department of Clinical Medicine, Keck School of Medicine; Director, University of Southern California Westside Center for Diabetes, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Serve(d) on the advisory board for Abbott Diabetes Care; Becton Dickinson; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Livongo; Medscape; Merck & Co., Inc.; Novo Nordisk; Omada Health; OptumHealth; sanofi; Zafgen Received research support from: Dexcom; MannKind Corporation; Astra Zeneca. Serve(d) as a member of a speakers bureau for: Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We Haven’t Kicked Our Pandemic Drinking Habit

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

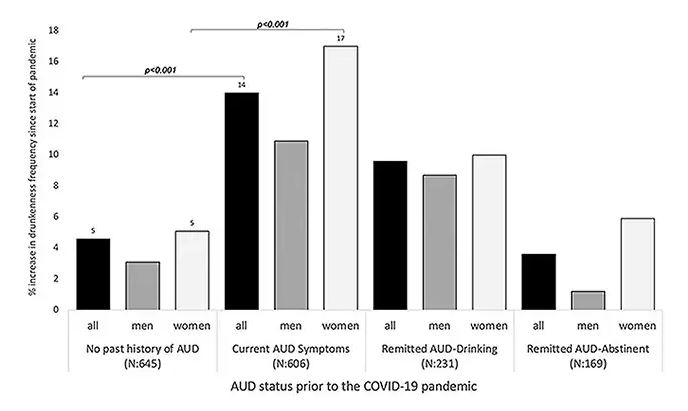

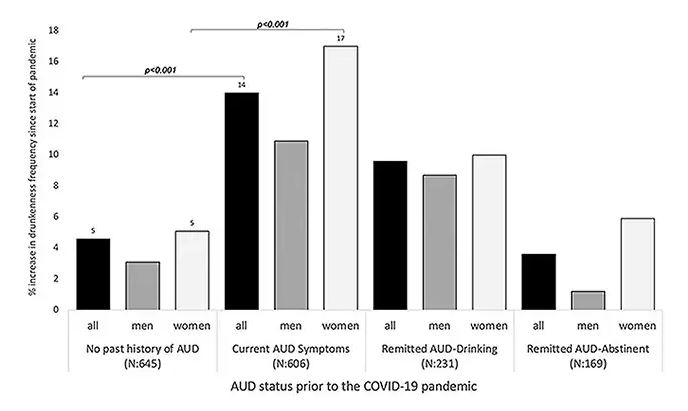

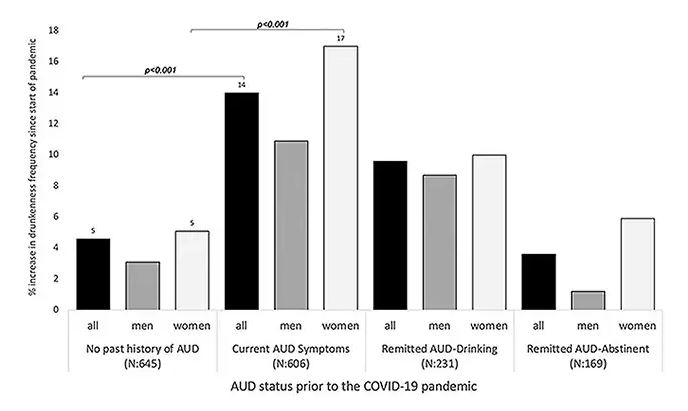

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

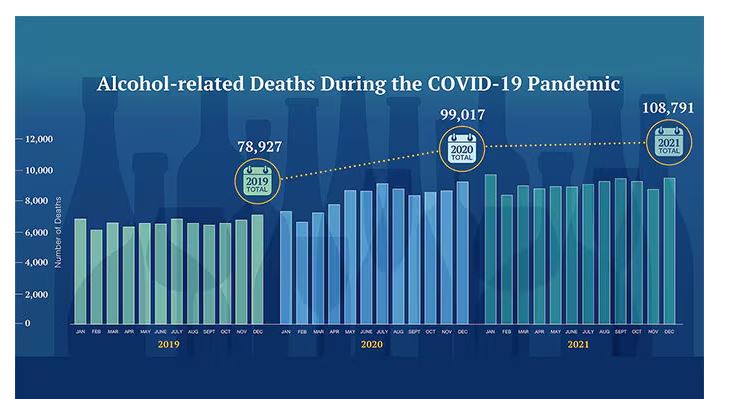

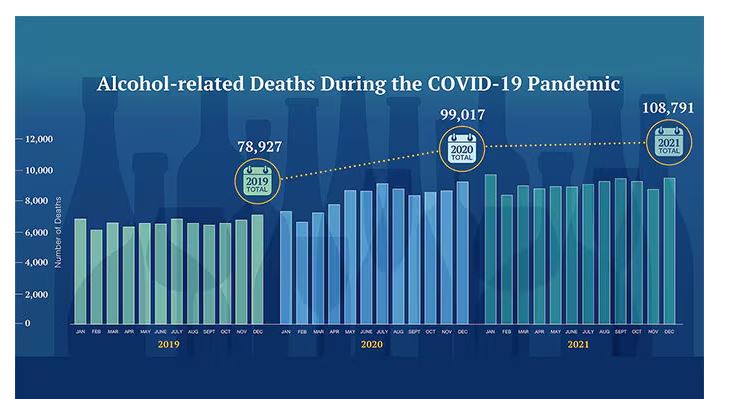

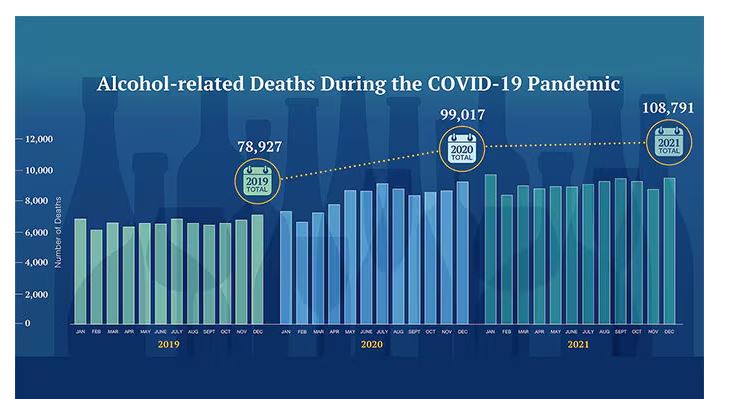

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

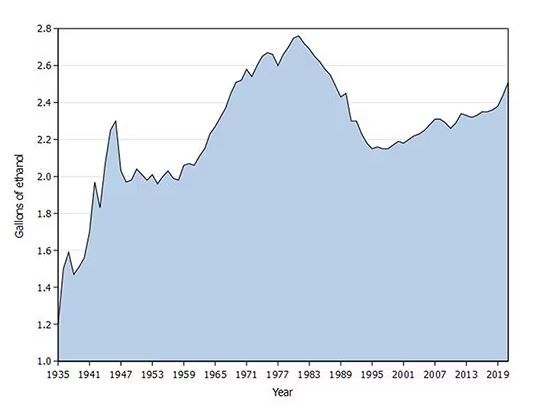

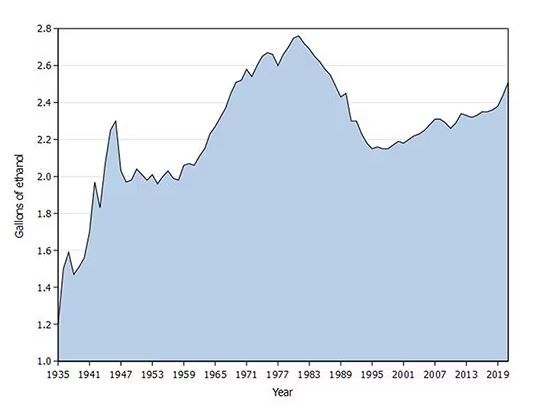

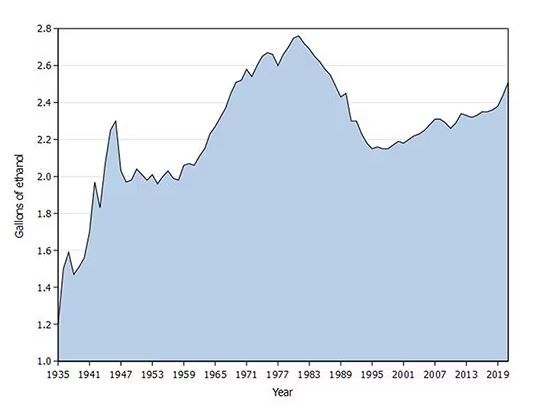

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

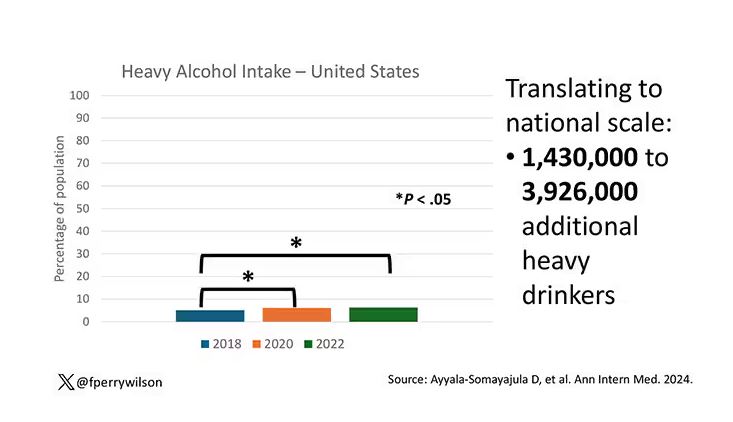

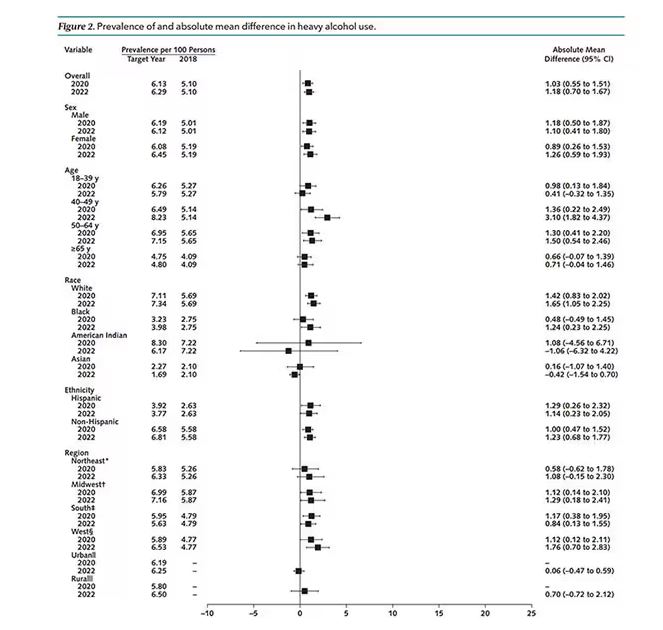

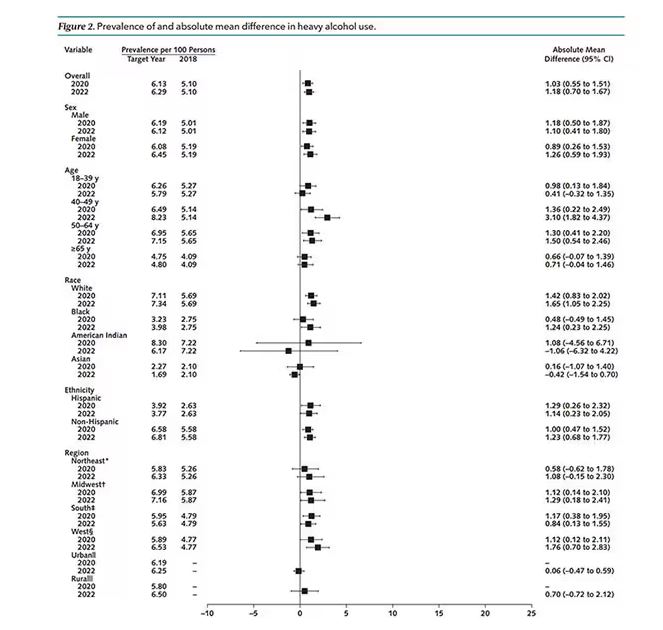

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

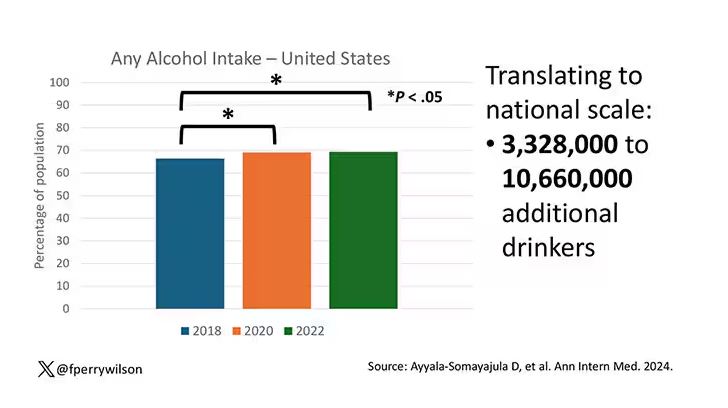

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

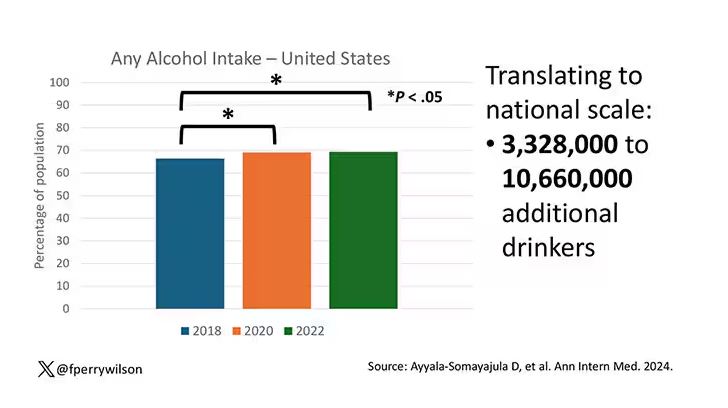

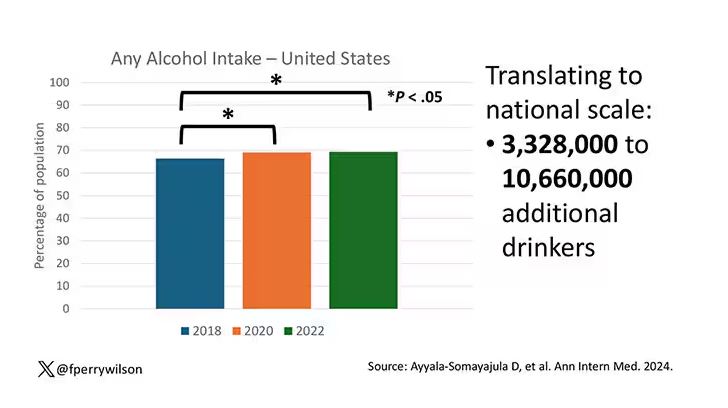

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

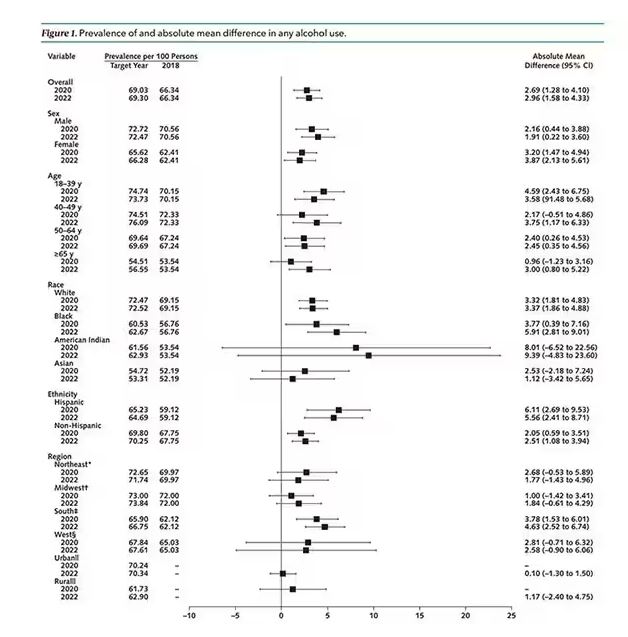

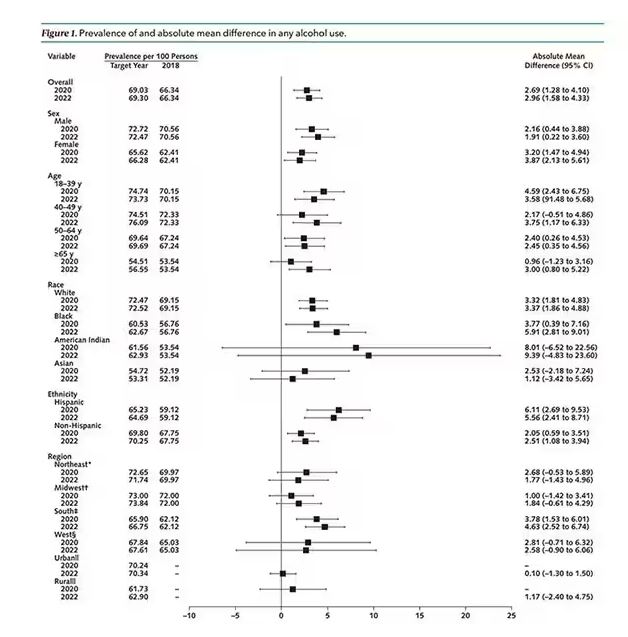

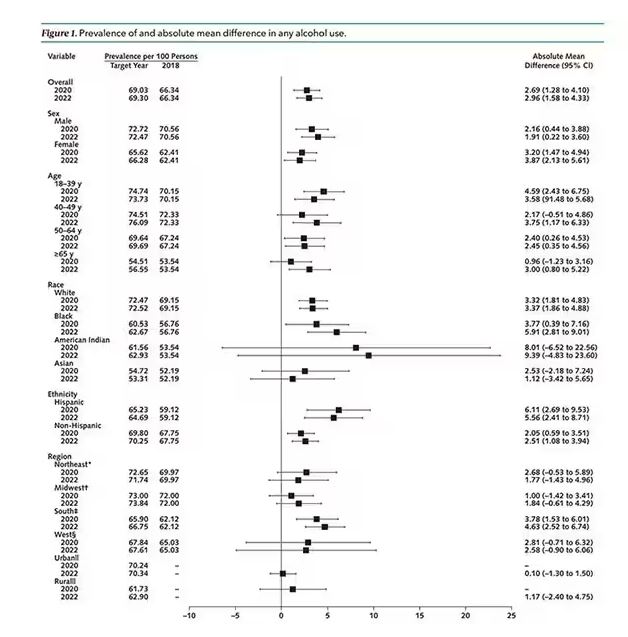

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

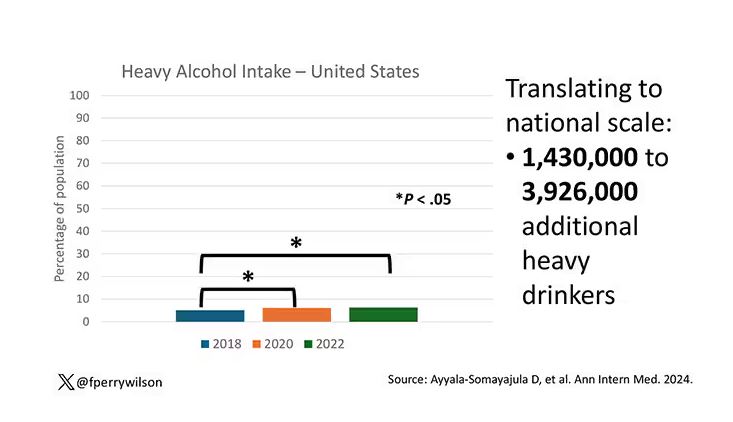

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

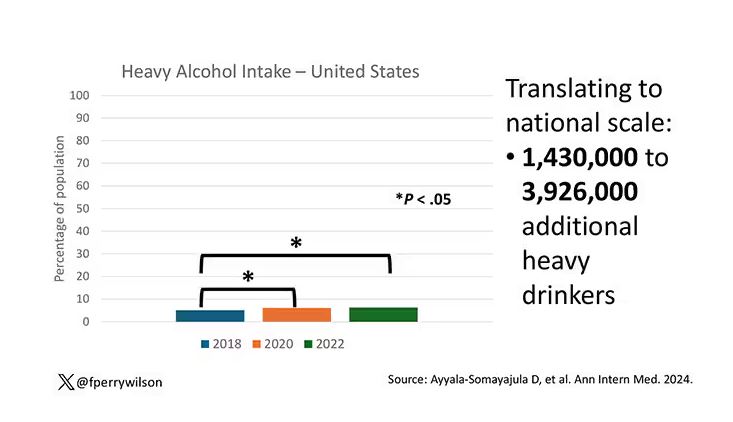

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

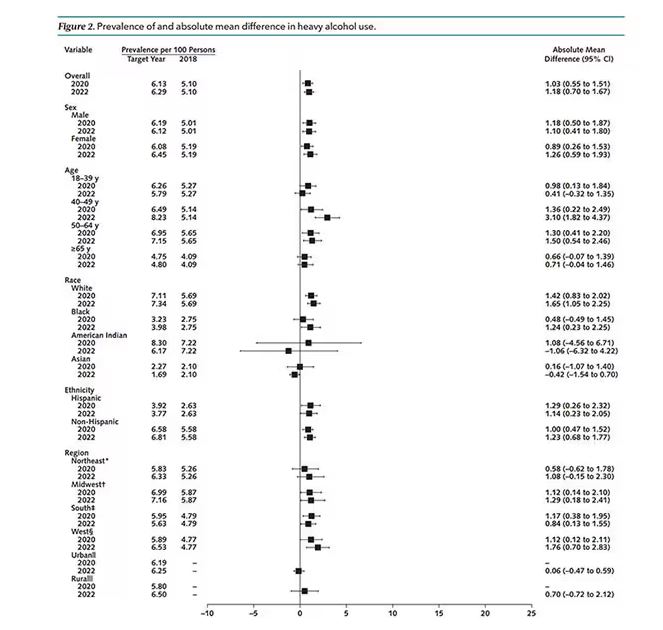

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How to Discuss Lifestyle Modifications in MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

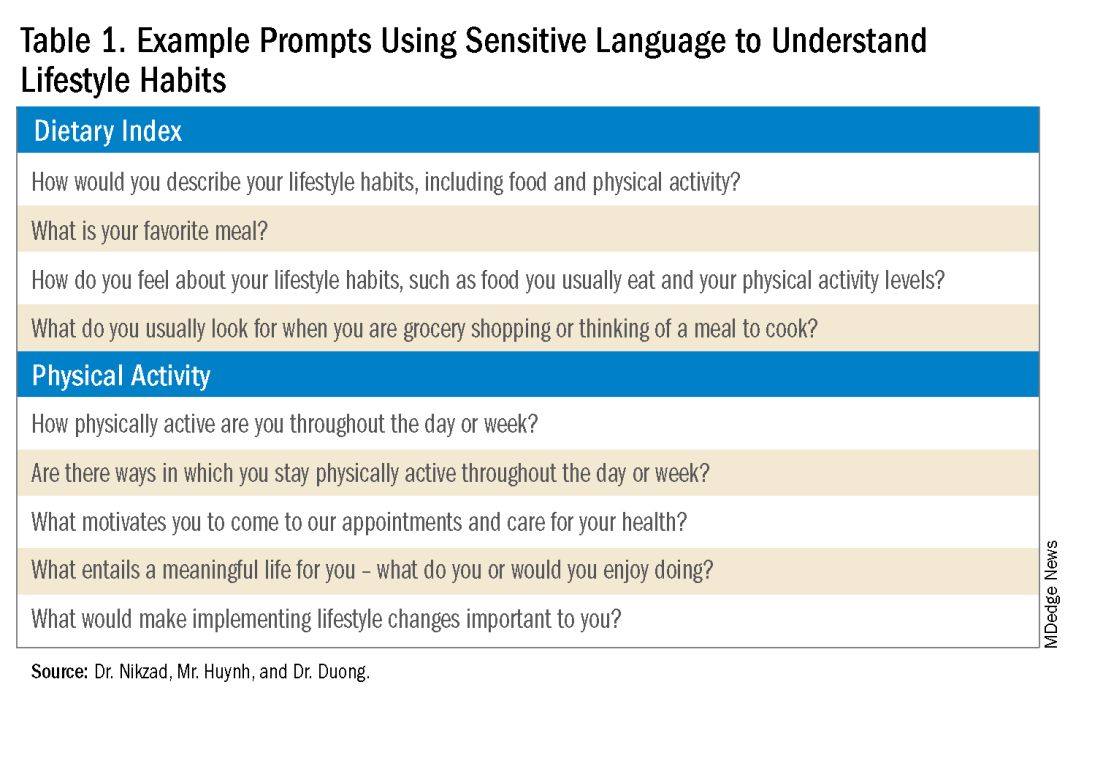

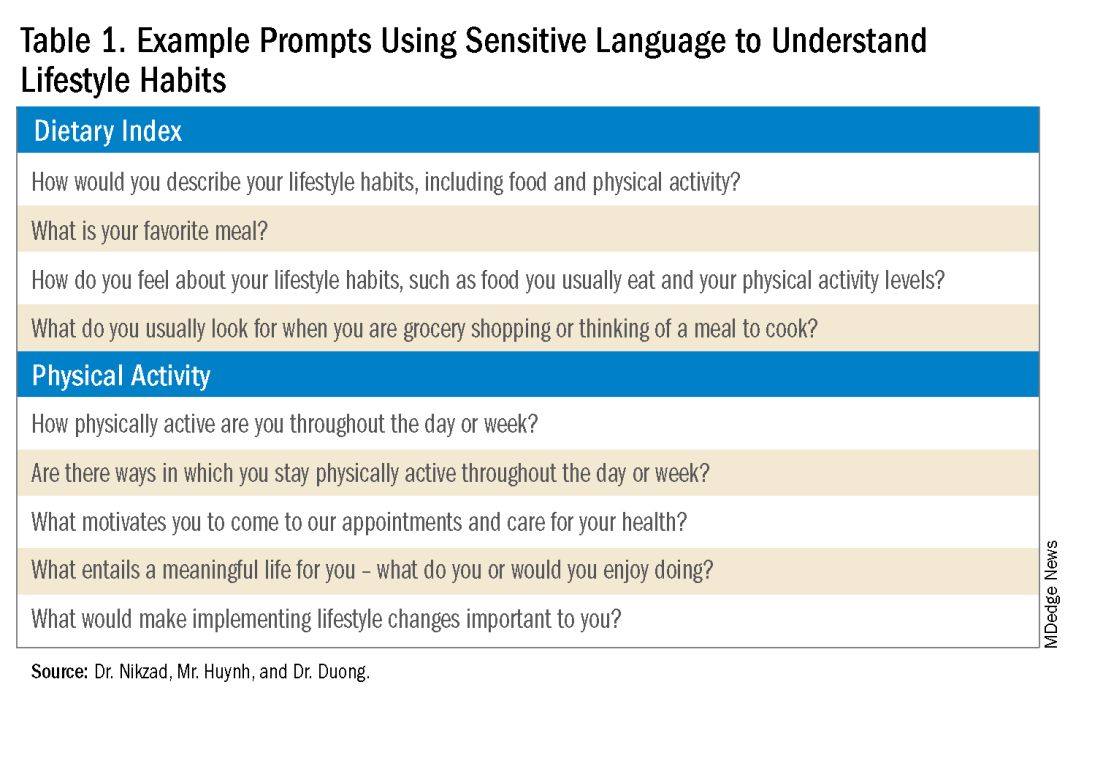

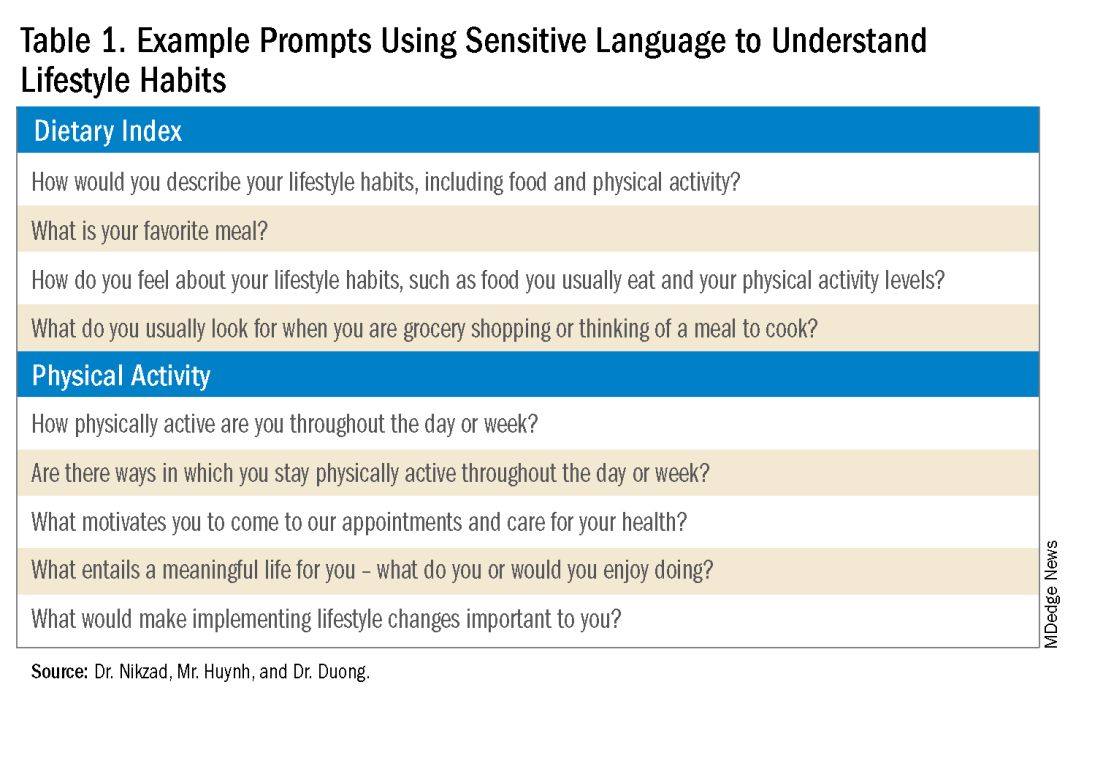

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

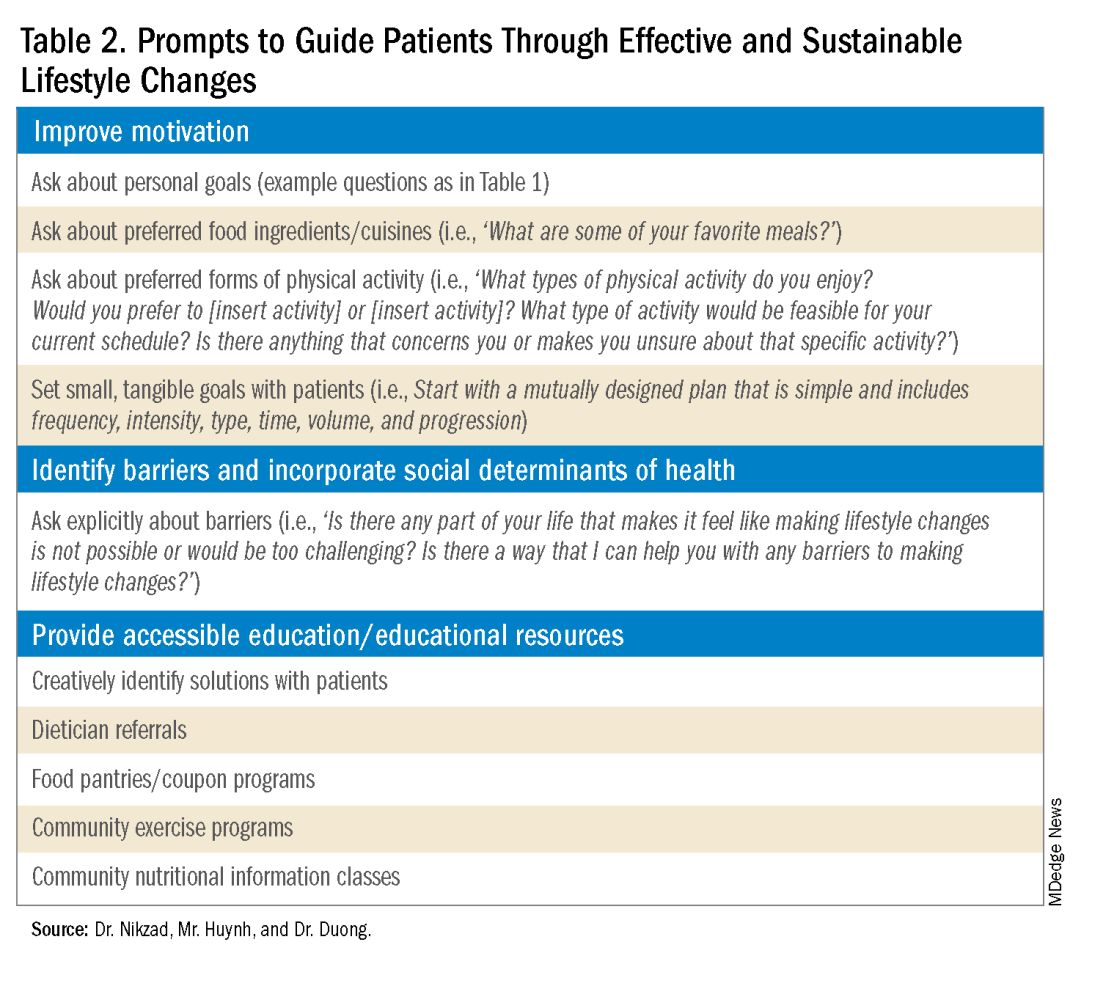

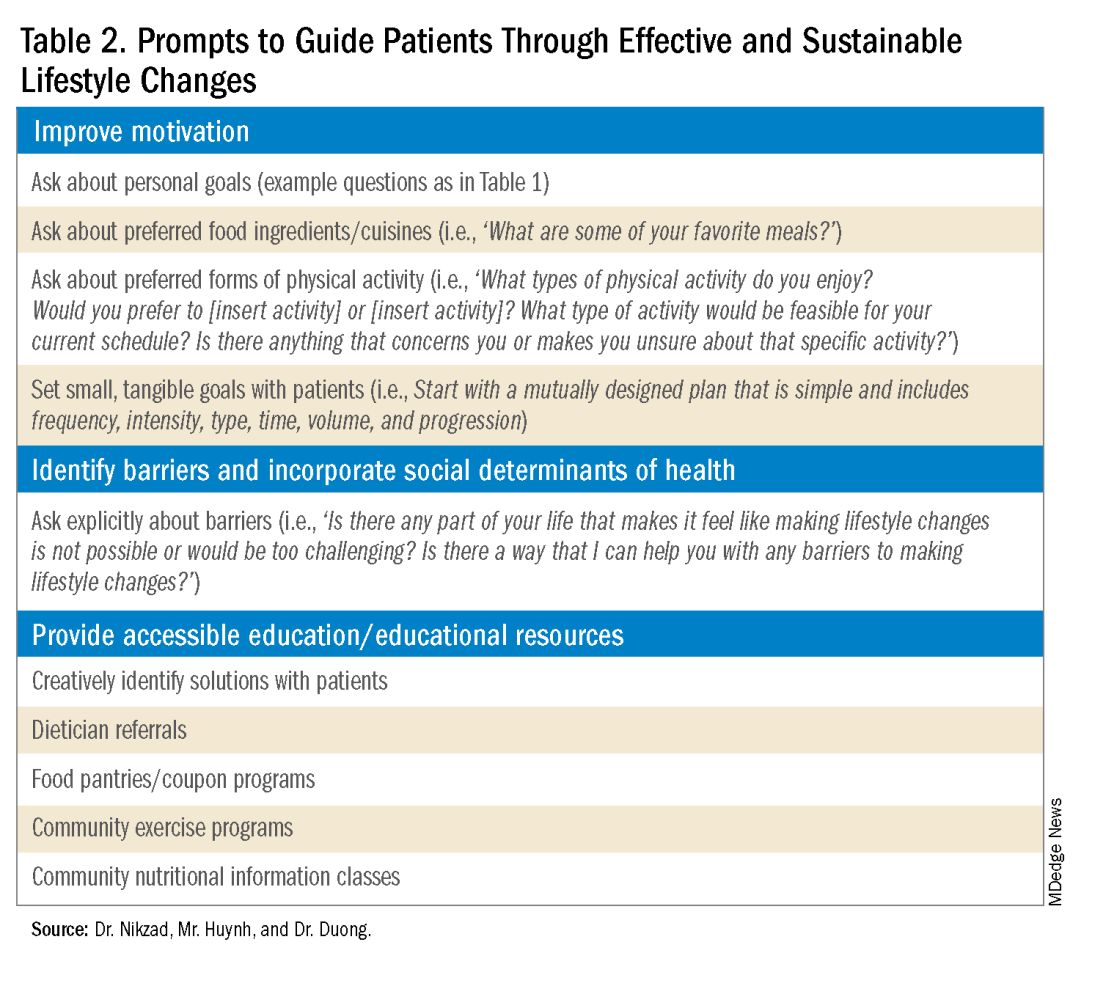

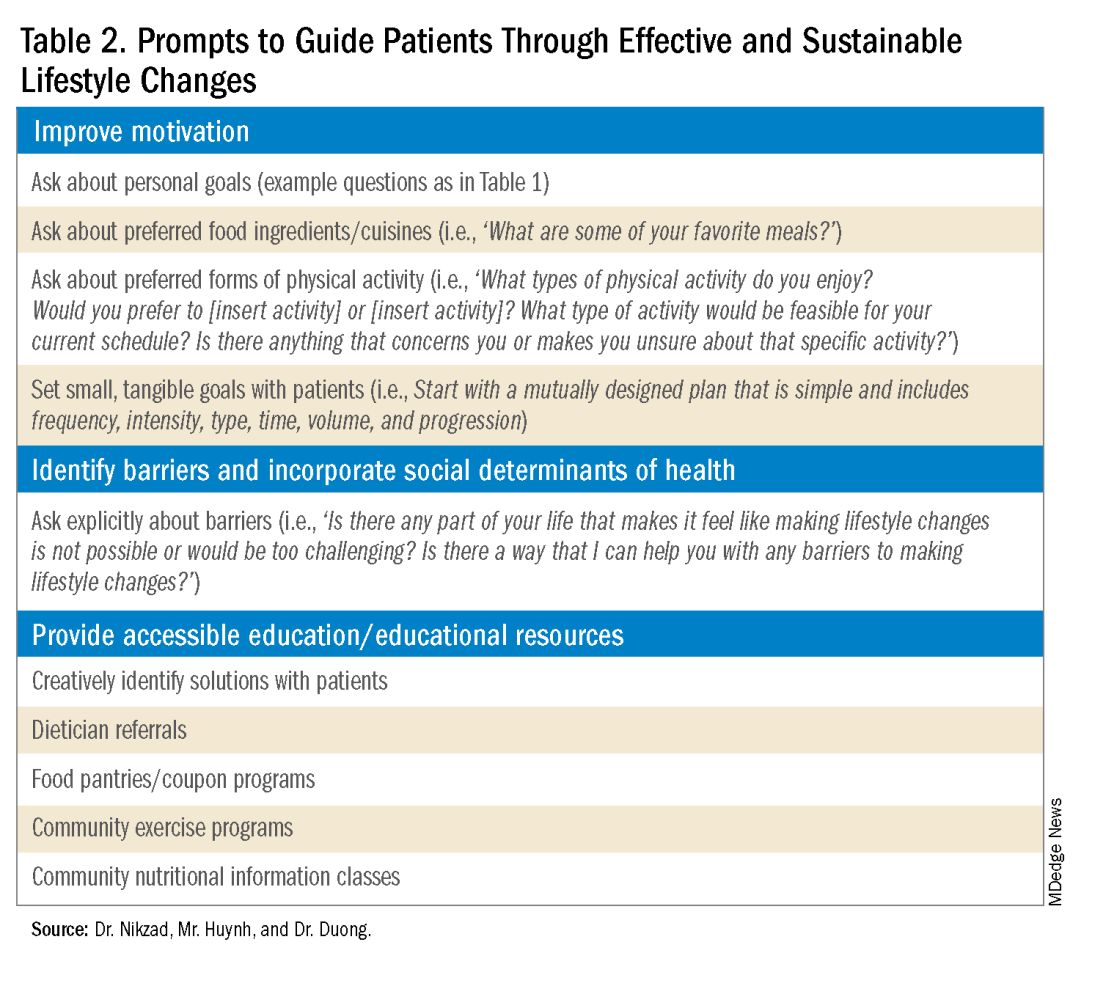

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Financial Empowerment Journey

Dear Friends,

One of the challenges I faced during training was managing my life outside of work. Many astute trainees started their financial empowerment journey early. However, I was too overwhelmed with what I did not know (the financial world) and just avoided it. Over the last year, I finally decided to embrace my lack of knowledge and find the support of experts, just as we would in medicine. A lot of questions from my journey translated into several articles in the “Finance” section of The New Gastroenterologist, so I encourage those who need guidance on embarking on their financial journeys to explore that section!

In the “In Focus” section, Dr. Patrick Chang, Dr. Supisara Tintara, and Dr. Jennifer Phan – all from the University of Southern California – review diagnostic modalities to assess gastroesophageal reflux disease with an emphasis on medical, endoscopic, and surgical managements.

With the rise in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), patient education is starting in the primary care and gastroenterologist’s office. Dr. Newsha Nikzad, medical student Daniel Huynh, and Dr. Nikki Duong share their approach to ask effectively about and communicate lifestyle modifications, with examples of using sensitive language and prompts to help guide patients, in the “Short Clinical Review” section.

The “Finance” section highlights the ins and outs of a physician mortgage loan and additional information for first time home buyers, reviewed by John G. Kelley II, a physician mortgage specialist and vice president of mortgage lending at Arvest Bank.

Lastly, in the “Early Career” section, Dr. Neil Gupta shares his experiences of transitioning from academic medicine to building a private practice group. He reflects on lessons learned from the first year after establishing his practice.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu) or Danielle Kiefer (dkiefer@gastro.org), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first proton pump inhibitor was omeprazole, discovered 45 years ago in 1979 in Sweden, and clinically available in the United States only 36 years ago in 1988.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

One of the challenges I faced during training was managing my life outside of work. Many astute trainees started their financial empowerment journey early. However, I was too overwhelmed with what I did not know (the financial world) and just avoided it. Over the last year, I finally decided to embrace my lack of knowledge and find the support of experts, just as we would in medicine. A lot of questions from my journey translated into several articles in the “Finance” section of The New Gastroenterologist, so I encourage those who need guidance on embarking on their financial journeys to explore that section!

In the “In Focus” section, Dr. Patrick Chang, Dr. Supisara Tintara, and Dr. Jennifer Phan – all from the University of Southern California – review diagnostic modalities to assess gastroesophageal reflux disease with an emphasis on medical, endoscopic, and surgical managements.

With the rise in metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), patient education is starting in the primary care and gastroenterologist’s office. Dr. Newsha Nikzad, medical student Daniel Huynh, and Dr. Nikki Duong share their approach to ask effectively about and communicate lifestyle modifications, with examples of using sensitive language and prompts to help guide patients, in the “Short Clinical Review” section.

The “Finance” section highlights the ins and outs of a physician mortgage loan and additional information for first time home buyers, reviewed by John G. Kelley II, a physician mortgage specialist and vice president of mortgage lending at Arvest Bank.

Lastly, in the “Early Career” section, Dr. Neil Gupta shares his experiences of transitioning from academic medicine to building a private practice group. He reflects on lessons learned from the first year after establishing his practice.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me (tjudy@wustl.edu) or Danielle Kiefer (dkiefer@gastro.org), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact because we would not be where we are now without appreciating where we were: The first proton pump inhibitor was omeprazole, discovered 45 years ago in 1979 in Sweden, and clinically available in the United States only 36 years ago in 1988.

Yours truly,

Judy A. Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Interventional Endoscopy, Division of Gastroenterology

Washington University in St. Louis

Dear Friends,

One of the challenges I faced during training was managing my life outside of work. Many astute trainees started their financial empowerment journey early. However, I was too overwhelmed with what I did not know (the financial world) and just avoided it. Over the last year, I finally decided to embrace my lack of knowledge and find the support of experts, just as we would in medicine. A lot of questions from my journey translated into several articles in the “Finance” section of The New Gastroenterologist, so I encourage those who need guidance on embarking on their financial journeys to explore that section!