User login

An Eruption While on Total Parenteral Nutrition

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AAE) is a rare disorder caused by severe zinc deficiency. Although acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder that typically manifests in infancy, AAE also can result from poor zinc intake, impaired absorption, or accelerated losses. There are reports of AAE in patients with zinc-deficient diets,1 eating disorders,2 bariatric and other gastrointestinal surgeries,3 malabsorptive diseases,4 and nephrotic syndrome.5

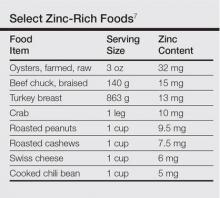

Zinc plays an important role in DNA and RNA synthesis, reactive oxygen species attenuation, and energy metabolism, allowing for proper wound healing, skin differentiation, and proliferation.6 Zinc is found in most foods, but animal protein contains higher concentrations (Table).7 Approximately 85% of zinc is stored in muscles and bones, with only a small amount of accessible zinc available in the liver. Liver stores can be depleted as quickly as 1 week.8 Total parenteral nutrition without trace element supplementation can quickly predispose patients to AAE.

|

|

Diagnosis of this condition requires triangulation of clinical presentation, histopathology examination, and laboratory findings. Acrodermatitis enteropathica typically is characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and epidermal appendage findings. In its early stages, the dermatitis often manifests with angular cheilitis and paronychia.9 Patients then develop erythema, erosions, and occasionally vesicles or psoriasiform plaques in periorificial, perineal, and acral sites (Figure 1). Epidermal appendage effects include generalized alopecia and thinning nails with white transverse ridges. Although dermatologic and gastrointestinal manifestations are the most obvious, severe AAE may cause other symptoms, including mental slowing, hypogonadism, and impaired immune function.9

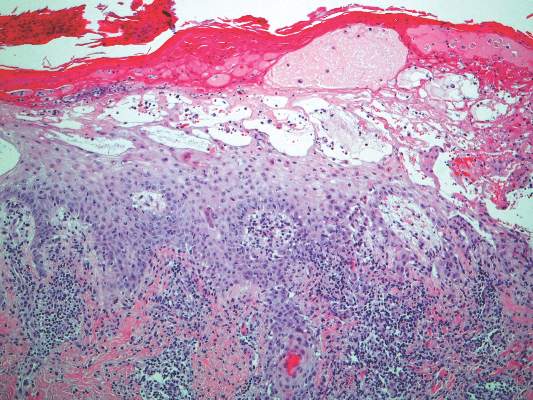

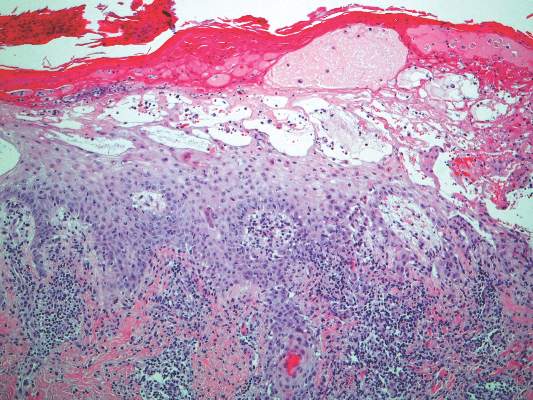

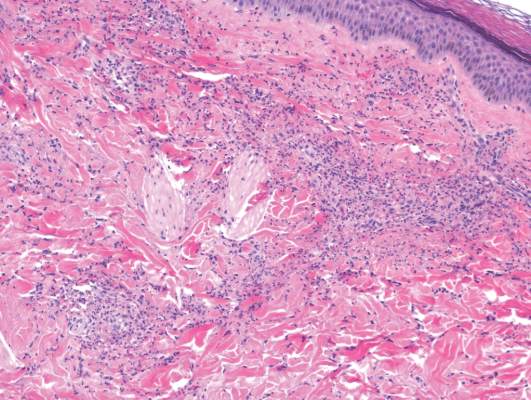

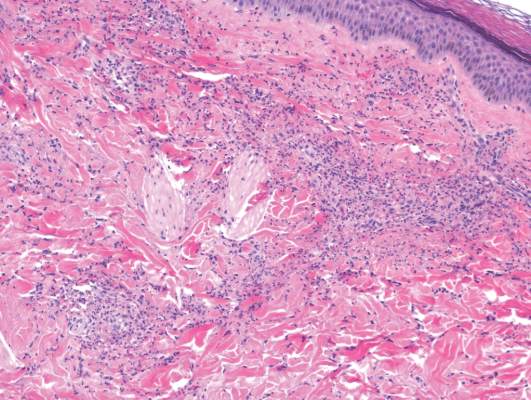

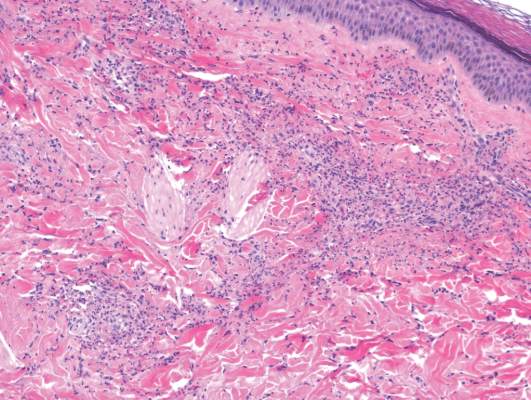

Histopathology of AAE skin lesions is similar to other nutritional deficiencies. Early changes are more specific to deficiency dermatitis and include cytoplasmic pallor and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum and granulosum.9 Necrolysis results in confluent keratinocyte necrosis developing into subcorneal bulla. Later in the disease course, the presentation becomes psoriasiform with keratinocyte dyskeratosis and confluent parakeratosis10 (Figure 2). Dermal edema with dilated tortuous vessels and a neutrophilic infiltrate may be present throughout disease progression.

Common laboratory abnormalities used to confirm zinc deficiency are decreased plasma zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels. Plasma zinc levels should be drawn after fasting because zinc levels decrease after food intake.9 Concurrent albumin levels should be drawn to correct for low levels caused by hypoalbuminemia. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica has been seen in patients with only mildly decreased plasma zinc levels or even zinc levels within reference range.11 Alkaline phosphatase metalloenzyme synthesis requires zinc and a decreased level suggests zinc deficiency even with a plasma zinc level within reference range. Alkaline phosphatase levels usually can be ascertained in a matter of hours, while the zinc levels take much longer to result.

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica is treated with oral elemental zinc supplementation at 1 to 2 mg/kg daily.12 Diarrhea typically resolves within 24 hours, but skin lesions heal in 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Although there is no consensus on when to discontinue zinc replacement therapy, therapy generally is not lifelong. Once the patient is zinc replete and the inciting factor has resolved, patients can discontinue supplementation without risk for recurrence.

Trace elements had not been added to our patient’s total parenteral nutrition prior to admission. Basic nutrition laboratory results and zinc levels returned markedly low: 14 μg/dL (reference range, 60–120 μg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent protein, also was low at 12 U/L (reference range, 40–150 U/L). We added trace elements and vitamins and began empiric zinc replacement with 440 mg oral zinc sulfate daily (100 mg elemental zinc). Cephalexin was prescribed for impetiginized skin lesions. The patient noted skin improvement after 3 days on zinc replacement therapy.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Kim ST, Kang JS, Baek JW, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica with anorexia nervosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:726-729.

- Bae-Harboe YS, Solky A, Masterpol KS. A case of acquired zinc deficiency. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Krasovec M, Frenk E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica secondary to Crohn’s disease. Dermatol Basel Switz. 1996;193:361-363.

- Reichel M, Mauro TM, Ziboh VA, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:415-417.

- Perafan-Riveros C, Franca LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service website. http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/nutrients/report/nutrientsfrm?max=25&offset=0&totCount=0&nutrient1=309&nutrient2=&nutrient3=&subset=0&fg=&sort=f&measureby=m. Accessed December 14, 2015.

- McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Gonzalez JR, Botet MV, Sanchez JL. The histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:303-311.

- Macdonald JB, Connolly SM, DiCaudo DJ. Think zinc deficiency: acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to poor diet and common medications. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:961-963.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal A, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AAE) is a rare disorder caused by severe zinc deficiency. Although acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder that typically manifests in infancy, AAE also can result from poor zinc intake, impaired absorption, or accelerated losses. There are reports of AAE in patients with zinc-deficient diets,1 eating disorders,2 bariatric and other gastrointestinal surgeries,3 malabsorptive diseases,4 and nephrotic syndrome.5

Zinc plays an important role in DNA and RNA synthesis, reactive oxygen species attenuation, and energy metabolism, allowing for proper wound healing, skin differentiation, and proliferation.6 Zinc is found in most foods, but animal protein contains higher concentrations (Table).7 Approximately 85% of zinc is stored in muscles and bones, with only a small amount of accessible zinc available in the liver. Liver stores can be depleted as quickly as 1 week.8 Total parenteral nutrition without trace element supplementation can quickly predispose patients to AAE.

|

|

Diagnosis of this condition requires triangulation of clinical presentation, histopathology examination, and laboratory findings. Acrodermatitis enteropathica typically is characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and epidermal appendage findings. In its early stages, the dermatitis often manifests with angular cheilitis and paronychia.9 Patients then develop erythema, erosions, and occasionally vesicles or psoriasiform plaques in periorificial, perineal, and acral sites (Figure 1). Epidermal appendage effects include generalized alopecia and thinning nails with white transverse ridges. Although dermatologic and gastrointestinal manifestations are the most obvious, severe AAE may cause other symptoms, including mental slowing, hypogonadism, and impaired immune function.9

Histopathology of AAE skin lesions is similar to other nutritional deficiencies. Early changes are more specific to deficiency dermatitis and include cytoplasmic pallor and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum and granulosum.9 Necrolysis results in confluent keratinocyte necrosis developing into subcorneal bulla. Later in the disease course, the presentation becomes psoriasiform with keratinocyte dyskeratosis and confluent parakeratosis10 (Figure 2). Dermal edema with dilated tortuous vessels and a neutrophilic infiltrate may be present throughout disease progression.

Common laboratory abnormalities used to confirm zinc deficiency are decreased plasma zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels. Plasma zinc levels should be drawn after fasting because zinc levels decrease after food intake.9 Concurrent albumin levels should be drawn to correct for low levels caused by hypoalbuminemia. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica has been seen in patients with only mildly decreased plasma zinc levels or even zinc levels within reference range.11 Alkaline phosphatase metalloenzyme synthesis requires zinc and a decreased level suggests zinc deficiency even with a plasma zinc level within reference range. Alkaline phosphatase levels usually can be ascertained in a matter of hours, while the zinc levels take much longer to result.

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica is treated with oral elemental zinc supplementation at 1 to 2 mg/kg daily.12 Diarrhea typically resolves within 24 hours, but skin lesions heal in 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Although there is no consensus on when to discontinue zinc replacement therapy, therapy generally is not lifelong. Once the patient is zinc replete and the inciting factor has resolved, patients can discontinue supplementation without risk for recurrence.

Trace elements had not been added to our patient’s total parenteral nutrition prior to admission. Basic nutrition laboratory results and zinc levels returned markedly low: 14 μg/dL (reference range, 60–120 μg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent protein, also was low at 12 U/L (reference range, 40–150 U/L). We added trace elements and vitamins and began empiric zinc replacement with 440 mg oral zinc sulfate daily (100 mg elemental zinc). Cephalexin was prescribed for impetiginized skin lesions. The patient noted skin improvement after 3 days on zinc replacement therapy.

The Diagnosis: Acquired Acrodermatitis Enteropathica

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica (AAE) is a rare disorder caused by severe zinc deficiency. Although acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal-recessive disorder that typically manifests in infancy, AAE also can result from poor zinc intake, impaired absorption, or accelerated losses. There are reports of AAE in patients with zinc-deficient diets,1 eating disorders,2 bariatric and other gastrointestinal surgeries,3 malabsorptive diseases,4 and nephrotic syndrome.5

Zinc plays an important role in DNA and RNA synthesis, reactive oxygen species attenuation, and energy metabolism, allowing for proper wound healing, skin differentiation, and proliferation.6 Zinc is found in most foods, but animal protein contains higher concentrations (Table).7 Approximately 85% of zinc is stored in muscles and bones, with only a small amount of accessible zinc available in the liver. Liver stores can be depleted as quickly as 1 week.8 Total parenteral nutrition without trace element supplementation can quickly predispose patients to AAE.

|

|

Diagnosis of this condition requires triangulation of clinical presentation, histopathology examination, and laboratory findings. Acrodermatitis enteropathica typically is characterized by dermatitis, diarrhea, and epidermal appendage findings. In its early stages, the dermatitis often manifests with angular cheilitis and paronychia.9 Patients then develop erythema, erosions, and occasionally vesicles or psoriasiform plaques in periorificial, perineal, and acral sites (Figure 1). Epidermal appendage effects include generalized alopecia and thinning nails with white transverse ridges. Although dermatologic and gastrointestinal manifestations are the most obvious, severe AAE may cause other symptoms, including mental slowing, hypogonadism, and impaired immune function.9

Histopathology of AAE skin lesions is similar to other nutritional deficiencies. Early changes are more specific to deficiency dermatitis and include cytoplasmic pallor and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes in the stratum spinosum and granulosum.9 Necrolysis results in confluent keratinocyte necrosis developing into subcorneal bulla. Later in the disease course, the presentation becomes psoriasiform with keratinocyte dyskeratosis and confluent parakeratosis10 (Figure 2). Dermal edema with dilated tortuous vessels and a neutrophilic infiltrate may be present throughout disease progression.

Common laboratory abnormalities used to confirm zinc deficiency are decreased plasma zinc and alkaline phosphatase levels. Plasma zinc levels should be drawn after fasting because zinc levels decrease after food intake.9 Concurrent albumin levels should be drawn to correct for low levels caused by hypoalbuminemia. Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica has been seen in patients with only mildly decreased plasma zinc levels or even zinc levels within reference range.11 Alkaline phosphatase metalloenzyme synthesis requires zinc and a decreased level suggests zinc deficiency even with a plasma zinc level within reference range. Alkaline phosphatase levels usually can be ascertained in a matter of hours, while the zinc levels take much longer to result.

Acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica is treated with oral elemental zinc supplementation at 1 to 2 mg/kg daily.12 Diarrhea typically resolves within 24 hours, but skin lesions heal in 1 to 2 weeks or longer. Although there is no consensus on when to discontinue zinc replacement therapy, therapy generally is not lifelong. Once the patient is zinc replete and the inciting factor has resolved, patients can discontinue supplementation without risk for recurrence.

Trace elements had not been added to our patient’s total parenteral nutrition prior to admission. Basic nutrition laboratory results and zinc levels returned markedly low: 14 μg/dL (reference range, 60–120 μg/dL). Alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent protein, also was low at 12 U/L (reference range, 40–150 U/L). We added trace elements and vitamins and began empiric zinc replacement with 440 mg oral zinc sulfate daily (100 mg elemental zinc). Cephalexin was prescribed for impetiginized skin lesions. The patient noted skin improvement after 3 days on zinc replacement therapy.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Kim ST, Kang JS, Baek JW, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica with anorexia nervosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:726-729.

- Bae-Harboe YS, Solky A, Masterpol KS. A case of acquired zinc deficiency. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Krasovec M, Frenk E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica secondary to Crohn’s disease. Dermatol Basel Switz. 1996;193:361-363.

- Reichel M, Mauro TM, Ziboh VA, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:415-417.

- Perafan-Riveros C, Franca LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service website. http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/nutrients/report/nutrientsfrm?max=25&offset=0&totCount=0&nutrient1=309&nutrient2=&nutrient3=&subset=0&fg=&sort=f&measureby=m. Accessed December 14, 2015.

- McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Gonzalez JR, Botet MV, Sanchez JL. The histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:303-311.

- Macdonald JB, Connolly SM, DiCaudo DJ. Think zinc deficiency: acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to poor diet and common medications. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:961-963.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal A, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Kim ST, Kang JS, Baek JW, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica with anorexia nervosa. J Dermatol. 2010;37:726-729.

- Bae-Harboe YS, Solky A, Masterpol KS. A case of acquired zinc deficiency. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Krasovec M, Frenk E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica secondary to Crohn’s disease. Dermatol Basel Switz. 1996;193:361-363.

- Reichel M, Mauro TM, Ziboh VA, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica in a patient with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:415-417.

- Perafan-Riveros C, Franca LFS, Alves ACF, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service website. http://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/nutrients/report/nutrientsfrm?max=25&offset=0&totCount=0&nutrient1=309&nutrient2=&nutrient3=&subset=0&fg=&sort=f&measureby=m. Accessed December 14, 2015.

- McPherson RA, Pincus MR. Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods. 22nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Gonzalez JR, Botet MV, Sanchez JL. The histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:303-311.

- Macdonald JB, Connolly SM, DiCaudo DJ. Think zinc deficiency: acquired acrodermatitis enteropathica due to poor diet and common medications. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:961-963.

- Kumar P, Lal NR, Mondal A, et al. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

A 47-year-old woman with a history of bulimia and gastroparesis who had been on total parenteral nutrition for 8 weeks presented with a painful, perioral, perineal, and acral eruption of 7 weeks’ duration. Additionally, she had experienced diarrhea, vomiting, and a 13.5-kg weight loss in the last 4 months. Physical examination revealed perioral and perineal, well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques with yellow crusting. She had edematous crusted erosions on the bilateral palms and soles and psoriasiform plaques along the right arm and flank. Punch biopsies (4 mm) from the right inguinal fold and right elbow were obtained.

Shortness of Breath and Loss of Appetite

Answer

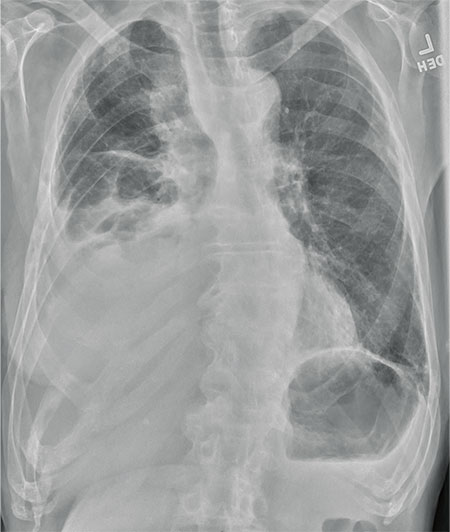

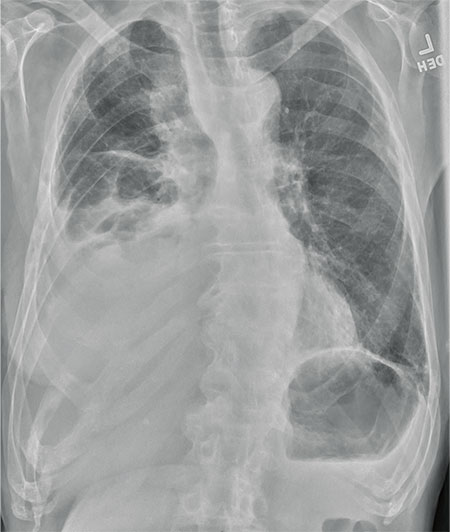

The radiograph shows several abnormalities: There is a moderate to large right pleural effusion, as well as a parenchymal density within the right lower lobe. In addition, several of the ribs have a mottled appearance.

All of these findings are highly suspicious for primary as well as metastatic carcinoma. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup.

Answer

The radiograph shows several abnormalities: There is a moderate to large right pleural effusion, as well as a parenchymal density within the right lower lobe. In addition, several of the ribs have a mottled appearance.

All of these findings are highly suspicious for primary as well as metastatic carcinoma. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup.

Answer

The radiograph shows several abnormalities: There is a moderate to large right pleural effusion, as well as a parenchymal density within the right lower lobe. In addition, several of the ribs have a mottled appearance.

All of these findings are highly suspicious for primary as well as metastatic carcinoma. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup.

An 80-year-old man presents with a complaint of acute shortness of breath. He says he has had difficulty breathing for the past two months, but the problem has worsened in the past two days. He reports experiencing dyspnea on exertion and denies fever or chills. He says he has had no appetite lately, adding that he’s lost about 20 to 30 lb in the past couple of months. Medical history is significant for atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism, hyperlipidemia, and remote bladder cancer. He is a former heavy smoker who quit about 30 years ago. On initial assessment, you note an elderly male in mild respiratory distress. His vital signs are stable, except for his O2 saturation, which is 90% on room air. On auscultation, you note decreased breath sounds on the right and occasional wheezing. You order some preliminary lab work, as well as a chest radiograph. What is your impression?

Cold and Fever Followed by Chest Discomfort

ANSWER

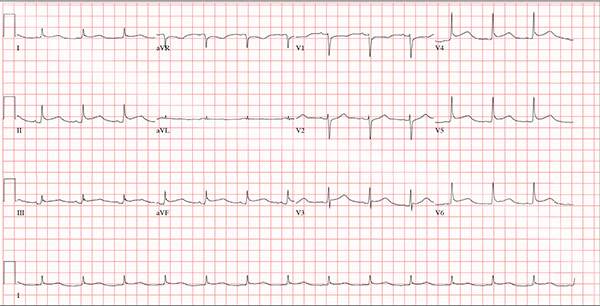

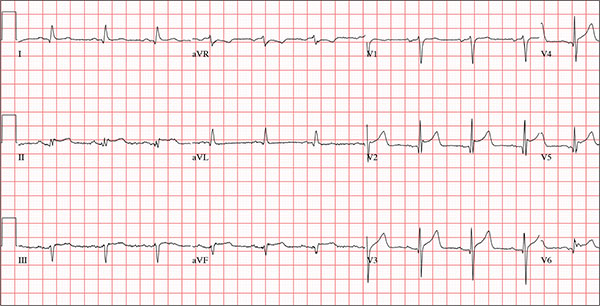

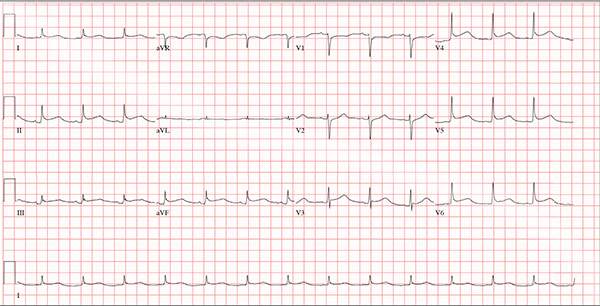

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm and diffuse ST elevations consistent with a diagnosis of pericarditis.

Although the QTc interval is long, it is due to the ST changes of pericarditis. Comparison with previous ECGs documented normal QTc intervals.

The patient’s pericarditis is most likely related to his recent viral illness. Following treatment with indomethacin, his symptoms resolved and his ECG normalized. Also, his abscess was managed by the surgical service and has since resolved.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm and diffuse ST elevations consistent with a diagnosis of pericarditis.

Although the QTc interval is long, it is due to the ST changes of pericarditis. Comparison with previous ECGs documented normal QTc intervals.

The patient’s pericarditis is most likely related to his recent viral illness. Following treatment with indomethacin, his symptoms resolved and his ECG normalized. Also, his abscess was managed by the surgical service and has since resolved.

ANSWER

This ECG demonstrates normal sinus rhythm and diffuse ST elevations consistent with a diagnosis of pericarditis.

Although the QTc interval is long, it is due to the ST changes of pericarditis. Comparison with previous ECGs documented normal QTc intervals.

The patient’s pericarditis is most likely related to his recent viral illness. Following treatment with indomethacin, his symptoms resolved and his ECG normalized. Also, his abscess was managed by the surgical service and has since resolved.

A 47-year-old man presents with a five-day history of chest discomfort that he describes as vague and achy but not painful. The discomfort does not radiate to his arm or neck and is not affected by activity. About six weeks ago, the patient says, he developed a severe viral cold that had him bedridden for several days. During his illness, his temperature reached 102°F for three or four days, and he developed a rash that subsided around the time his fever did. He had shortness of breath then, but not now. He adds, however, that if he takes a deep breath, coughs, or sneezes, he feels a shooting pain beneath his sternum. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Surgical history includes a left inguinal hernia repair at age 6, an appendectomy for acute appendicitis at age 13, and a successful catheter ablation at age 24. The patient, a long-haul trucker, is on the road five days a week and home on weekends. He is married and has four teenage children. He does not smoke or use recreational drugs; the company he works for performs weekly drug checks and offers financial incentives to employees who do not smoke. Family history reveals that his father died at age 68 of complications of diabetes. His 64-year-old mother is alive and well and has no health issues of which he is aware. His grandparents are deceased, and he has no information on their medical history. His medication list includes metoprolol, glyburide, and metformin. He has no known drug allergies. Review of systems reveals that he has recently developed an abscess on his left buttock that he says he needs to get fixed. He wears glasses and has several teeth with dental caries. He denies any symptoms suggestive of diabetic neuropathy. The remainder of the review is normal. Physical exam reveals that he weighs 228 lb and stands 76 in tall. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 138/84 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; temperature, 99°F; and O2 saturation, 97% on room air. Pertinent physical findings include clear lungs bilaterally and a friction rub over the entire precordium. The abdomen is soft and nontender. There is a 1-cm abscess located 2 cm left of the sacrum that is fluctuant and tender to palpation. There is no peripheral edema. All pulses are present and strong bilaterally, and there are no focal neurologic findings. Laboratory tests reveal a normal blood chemistry panel. The complete blood count is remarkable for a white blood cell count of 12,000 cells/µL. In light of the friction rub, an ECG is obtained. It shows a ventricular rate of 82 beats/min; PR interval, 130 ms; QRS duration, 90 ms; QT/QTc interval, 442/516 ms; P axis, 78°; R axis, 59°; and T axis, 73°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Lesion Is Tender and Bleeds Copiously

ANSWER

The correct answer is pyogenic granuloma (choice “d”), further discussion of which follows. Bacillary angiomatosis (choice “a”) is a lesion caused by infection with a species of Bartonella—a distinctly unusual problem. While a retained foreign body (choice “b”), such as a splinter, could trigger a similar lesion, there was no relevant history to suggest this was the case here. The most concerning differential item, melanoma (choice “c”), can present as a glistening red nodule, especially in children, but this too would be quite unusual.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the name originally given to these common lesions, which are neither pyogenic (pus producing) nor truly granulomatous (demonstrating a classic histologic pattern). Rather, they are the body’s frustrated attempt to lay down new blood supply in a healing but oft-traumatized lesion (eg, acne lesion, tag, nevus, or wart).

Other names for them include sclerosing hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma. Their appearance can vary from the classic look seen in this case to older lesions that tend to be drier and more warty.

PGs are far more common in children than in adults and greatly favor females over males. Pregnancy appears to trigger them, especially in the mouth, but they can appear on fingers, nipples, or even the scalp. Certain drugs, such as isotretinoin and certain chemotherapy agents, predispose to their formation.

PGs removed from children (by shave technique, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage) must be sent for pathologic examination to rule out nodular melanoma. That’s what was done in this case, with the pathology report confirming the expected vascular nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pyogenic granuloma (choice “d”), further discussion of which follows. Bacillary angiomatosis (choice “a”) is a lesion caused by infection with a species of Bartonella—a distinctly unusual problem. While a retained foreign body (choice “b”), such as a splinter, could trigger a similar lesion, there was no relevant history to suggest this was the case here. The most concerning differential item, melanoma (choice “c”), can present as a glistening red nodule, especially in children, but this too would be quite unusual.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the name originally given to these common lesions, which are neither pyogenic (pus producing) nor truly granulomatous (demonstrating a classic histologic pattern). Rather, they are the body’s frustrated attempt to lay down new blood supply in a healing but oft-traumatized lesion (eg, acne lesion, tag, nevus, or wart).

Other names for them include sclerosing hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma. Their appearance can vary from the classic look seen in this case to older lesions that tend to be drier and more warty.

PGs are far more common in children than in adults and greatly favor females over males. Pregnancy appears to trigger them, especially in the mouth, but they can appear on fingers, nipples, or even the scalp. Certain drugs, such as isotretinoin and certain chemotherapy agents, predispose to their formation.

PGs removed from children (by shave technique, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage) must be sent for pathologic examination to rule out nodular melanoma. That’s what was done in this case, with the pathology report confirming the expected vascular nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is pyogenic granuloma (choice “d”), further discussion of which follows. Bacillary angiomatosis (choice “a”) is a lesion caused by infection with a species of Bartonella—a distinctly unusual problem. While a retained foreign body (choice “b”), such as a splinter, could trigger a similar lesion, there was no relevant history to suggest this was the case here. The most concerning differential item, melanoma (choice “c”), can present as a glistening red nodule, especially in children, but this too would be quite unusual.

DISCUSSION

Pyogenic granuloma (PG) was the name originally given to these common lesions, which are neither pyogenic (pus producing) nor truly granulomatous (demonstrating a classic histologic pattern). Rather, they are the body’s frustrated attempt to lay down new blood supply in a healing but oft-traumatized lesion (eg, acne lesion, tag, nevus, or wart).

Other names for them include sclerosing hemangioma and lobular capillary hemangioma. Their appearance can vary from the classic look seen in this case to older lesions that tend to be drier and more warty.

PGs are far more common in children than in adults and greatly favor females over males. Pregnancy appears to trigger them, especially in the mouth, but they can appear on fingers, nipples, or even the scalp. Certain drugs, such as isotretinoin and certain chemotherapy agents, predispose to their formation.

PGs removed from children (by shave technique, followed by electrodesiccation and curettage) must be sent for pathologic examination to rule out nodular melanoma. That’s what was done in this case, with the pathology report confirming the expected vascular nature of the lesion.

The lesion on the face of this 16-year-old girl is slightly tender to the touch and bleeds copiously with even minor trauma. It manifested several months ago and has persisted even after a course of oral antibiotics (trimethoprim/sulfa) as well as twice-daily application of mupirocin ointment. Prior to the lesion’s appearance, the girl experienced an acne flare. Her mother, who is present, says her daughter “just couldn’t leave it alone” and was often observed picking at the problem area. The patient is otherwise healthy. The lesion in question measures about 1.6 cm. It comprises a round, flesh-colored, 1-cm nodule in the center of which is a bright red, glistening 5-mm papule. There is no erythema in or around the lesion or any palpable adenopathy. The rest of the patient’s exposed skin is unremarkable.

Acute Serpiginous Rash

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Three punch biopsies were obtained. Spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils was seen. There was a single specimen of tissue that showed a possible intraepidermal larva with a tract in the epidermis. The differential diagnosis included allergic contact dermatitis and arthropod bite eruption, among others, but clinical correlation made cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) the likely diagnosis.

The patient was treated empirically with albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 days. In addition, he was prescribed triamcinolone for symptomatic relief and remained asymptomatic for 8 weeks at which time he presented again to the dermatology clinic with a similar rash in the same distribution. He was treated with a repeat course of albendazole and further educated on the etiology of the infection. The patient has not exhibited a recurrence after treatment of the second episode of CLM.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a dermatosis of the skin caused by the larvae of parasitic nematodes from the hookworm family, most commonly Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense.1,2 These hookworms thrive in warm moist climates and are most frequently found in tropical coastal regions. They normally inhabit the intestines of animals such as dogs and cats and are transmitted to soil and sand via feces. Humans become accidental hosts through contact with the contaminated sand or soil3; however, the larvae are unable to penetrate deeper than the upper dermis of the skin in humans, subsequently limiting the infection. Because humans are accidental hosts, the larvae are unable to complete their life cycle and larval death occurs within weeks to months after the initial infection3; thus treatment may be unnecessary unless complications arise.

Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly observed in travelers or inhabitants of tropical coastal regions but can occur anywhere in the world.1 Clinically, CLM presents as an enlarging, intensely pruritic, erythematous linear or serpiginous tract,3 most commonly on the hands, feet, abdomen, and buttocks.1 Complications may include allergic reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and hookworm folliculitis.4 Although rare, migration to the intestinal tract5 and/or hematological spread with Löffler syndrome has been described.6 Although this dermatological disease has been well described in the medical literature, it is not well recognized by Western physicians and is consequently either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.4 Although the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment, the risk for prolonged active disease may occur, with 1 reported case lasting up to 18 months.4,5 The first indicator of CLM is intense pruritus localized to the site of infection.4 As the larvae migrate or creep, they create a lesion that may appear edematous with vesiculobullous lesions that are either serpiginous or linear.4 The differential diagnosis may include fungal infection, bacterial infection, and atypical herpes simplex infections; however, the key finding in CLM is the presence of undulating tracts localized to the borders of the lesion.2 Patients may report experiencing a stinging sensation prior to the formation of the erythematous scaly papule,5 which is attributed to the initial penetration of the larva into the skin. This development, accompanied with a history of travel to tropical or subtropical regions, should elicit CLM as a likely diagnosis. Because hookworms are a type of helminth, they likely elicit an eosinophilic immune response and thus peripheral eosinophilia may be present.5

Effective treatment of CLM is accomplished with oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 to 7 days.2,7 Alternatively, oral ivermectin, topical thiabendazole, and cryosurgery can be used,2 though albendazole currently is the preferred treatment of CLM.7

- Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:799-807.

- Roest MA, Ratnavel R. Cutaneous larva migrans contracted in England: a reminder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:389-390.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:434-437.

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007;14:326-333.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:655-668, viii.

- Guill MA, Odom RB. Larva migrans complicated by Loeffler’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1525-1526.

- Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:811-814.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Three punch biopsies were obtained. Spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils was seen. There was a single specimen of tissue that showed a possible intraepidermal larva with a tract in the epidermis. The differential diagnosis included allergic contact dermatitis and arthropod bite eruption, among others, but clinical correlation made cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) the likely diagnosis.

The patient was treated empirically with albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 days. In addition, he was prescribed triamcinolone for symptomatic relief and remained asymptomatic for 8 weeks at which time he presented again to the dermatology clinic with a similar rash in the same distribution. He was treated with a repeat course of albendazole and further educated on the etiology of the infection. The patient has not exhibited a recurrence after treatment of the second episode of CLM.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a dermatosis of the skin caused by the larvae of parasitic nematodes from the hookworm family, most commonly Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense.1,2 These hookworms thrive in warm moist climates and are most frequently found in tropical coastal regions. They normally inhabit the intestines of animals such as dogs and cats and are transmitted to soil and sand via feces. Humans become accidental hosts through contact with the contaminated sand or soil3; however, the larvae are unable to penetrate deeper than the upper dermis of the skin in humans, subsequently limiting the infection. Because humans are accidental hosts, the larvae are unable to complete their life cycle and larval death occurs within weeks to months after the initial infection3; thus treatment may be unnecessary unless complications arise.

Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly observed in travelers or inhabitants of tropical coastal regions but can occur anywhere in the world.1 Clinically, CLM presents as an enlarging, intensely pruritic, erythematous linear or serpiginous tract,3 most commonly on the hands, feet, abdomen, and buttocks.1 Complications may include allergic reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and hookworm folliculitis.4 Although rare, migration to the intestinal tract5 and/or hematological spread with Löffler syndrome has been described.6 Although this dermatological disease has been well described in the medical literature, it is not well recognized by Western physicians and is consequently either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.4 Although the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment, the risk for prolonged active disease may occur, with 1 reported case lasting up to 18 months.4,5 The first indicator of CLM is intense pruritus localized to the site of infection.4 As the larvae migrate or creep, they create a lesion that may appear edematous with vesiculobullous lesions that are either serpiginous or linear.4 The differential diagnosis may include fungal infection, bacterial infection, and atypical herpes simplex infections; however, the key finding in CLM is the presence of undulating tracts localized to the borders of the lesion.2 Patients may report experiencing a stinging sensation prior to the formation of the erythematous scaly papule,5 which is attributed to the initial penetration of the larva into the skin. This development, accompanied with a history of travel to tropical or subtropical regions, should elicit CLM as a likely diagnosis. Because hookworms are a type of helminth, they likely elicit an eosinophilic immune response and thus peripheral eosinophilia may be present.5

Effective treatment of CLM is accomplished with oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 to 7 days.2,7 Alternatively, oral ivermectin, topical thiabendazole, and cryosurgery can be used,2 though albendazole currently is the preferred treatment of CLM.7

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Larva Migrans

Three punch biopsies were obtained. Spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils was seen. There was a single specimen of tissue that showed a possible intraepidermal larva with a tract in the epidermis. The differential diagnosis included allergic contact dermatitis and arthropod bite eruption, among others, but clinical correlation made cutaneous larva migrans (CLM) the likely diagnosis.

The patient was treated empirically with albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 days. In addition, he was prescribed triamcinolone for symptomatic relief and remained asymptomatic for 8 weeks at which time he presented again to the dermatology clinic with a similar rash in the same distribution. He was treated with a repeat course of albendazole and further educated on the etiology of the infection. The patient has not exhibited a recurrence after treatment of the second episode of CLM.

Cutaneous larva migrans is a dermatosis of the skin caused by the larvae of parasitic nematodes from the hookworm family, most commonly Ancylostoma caninum and Ancylostoma braziliense.1,2 These hookworms thrive in warm moist climates and are most frequently found in tropical coastal regions. They normally inhabit the intestines of animals such as dogs and cats and are transmitted to soil and sand via feces. Humans become accidental hosts through contact with the contaminated sand or soil3; however, the larvae are unable to penetrate deeper than the upper dermis of the skin in humans, subsequently limiting the infection. Because humans are accidental hosts, the larvae are unable to complete their life cycle and larval death occurs within weeks to months after the initial infection3; thus treatment may be unnecessary unless complications arise.

Cutaneous larva migrans is most commonly observed in travelers or inhabitants of tropical coastal regions but can occur anywhere in the world.1 Clinically, CLM presents as an enlarging, intensely pruritic, erythematous linear or serpiginous tract,3 most commonly on the hands, feet, abdomen, and buttocks.1 Complications may include allergic reactions, secondary bacterial infections, and hookworm folliculitis.4 Although rare, migration to the intestinal tract5 and/or hematological spread with Löffler syndrome has been described.6 Although this dermatological disease has been well described in the medical literature, it is not well recognized by Western physicians and is consequently either not diagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to delays in treatment.4 Although the infection is usually self-limiting without treatment, the risk for prolonged active disease may occur, with 1 reported case lasting up to 18 months.4,5 The first indicator of CLM is intense pruritus localized to the site of infection.4 As the larvae migrate or creep, they create a lesion that may appear edematous with vesiculobullous lesions that are either serpiginous or linear.4 The differential diagnosis may include fungal infection, bacterial infection, and atypical herpes simplex infections; however, the key finding in CLM is the presence of undulating tracts localized to the borders of the lesion.2 Patients may report experiencing a stinging sensation prior to the formation of the erythematous scaly papule,5 which is attributed to the initial penetration of the larva into the skin. This development, accompanied with a history of travel to tropical or subtropical regions, should elicit CLM as a likely diagnosis. Because hookworms are a type of helminth, they likely elicit an eosinophilic immune response and thus peripheral eosinophilia may be present.5

Effective treatment of CLM is accomplished with oral albendazole 400 mg once daily for 3 to 7 days.2,7 Alternatively, oral ivermectin, topical thiabendazole, and cryosurgery can be used,2 though albendazole currently is the preferred treatment of CLM.7

- Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:799-807.

- Roest MA, Ratnavel R. Cutaneous larva migrans contracted in England: a reminder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:389-390.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:434-437.

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007;14:326-333.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:655-668, viii.

- Guill MA, Odom RB. Larva migrans complicated by Loeffler’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1525-1526.

- Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:811-814.

- Hotez PJ, Brooker S, Bethony JM, et al. Hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:799-807.

- Roest MA, Ratnavel R. Cutaneous larva migrans contracted in England: a reminder. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:389-390.

- Blackwell V, Vega-Lopez F. Cutaneous larva migrans: clinical features and management of 44 cases presenting in the returning traveller. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:434-437.

- Hochedez P, Caumes E. Hookworm-related cutaneous larva migrans. J Travel Med. 2007;14:326-333.

- Bravo F, Sanchez MR. New and re-emerging cutaneous infectious diseases in Latin America and other geographic areas. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:655-668, viii.

- Guill MA, Odom RB. Larva migrans complicated by Loeffler’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1525-1526.

- Caumes E. Treatment of cutaneous larva migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:811-814.

A 62-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a severely pruritic and painful rash of 1 week’s duration. The rash began as an erythematous papule on the right buttock but had spread in a serpiginous manner to the groin and left buttock. The patient stated that he could see the rash spreading in a serpiginous manner over a matter of hours. The patient’s medical history was unremarkable and a review of symptoms was otherwise negative. Physical examination revealed an erythematous serpiginous eruption that was most prominent on the right buttock but extended to the left buttock and down the right leg. He also exhibited several erythematous papules with excoriations in that region.

Erythematous Eruption on the Left Leg

The Diagnosis: Bullous Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

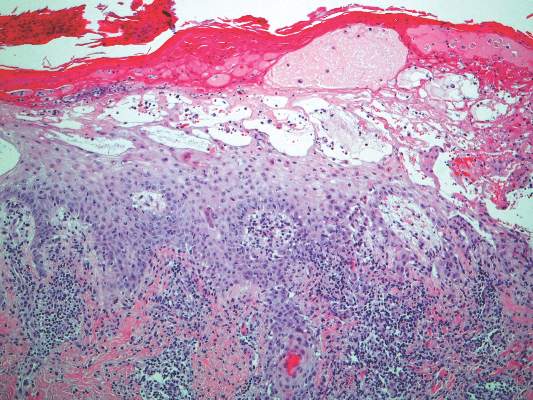

Laboratory tests in this patient showed no abnormalities for complete blood cell count, immunoglobulins, anti–double-stranded DNA, antinuclear antibody, p–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, Sjögren antibodies, liver enzymes, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Urinalysis was normal. Punch biopsies were obtained and a histologic examination showed an intense inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils around blood vessels within the dermis (Figure). These blood vessels showed swollen endothelium and narrowing of the vessel lumina with leukocytoclasia. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA, C3, fibrin, and weak IgM deposits in blood vessels in the papillary dermis consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is the most common vasculitis in children.1-6 However, its bullous variant is rare, with few pediatric cases reported. Bullous HSP affects arterioles through an IgA-mediated pathway.1-6 It is believed that the bullae are formed secondary to neutrophilic release of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), which degrades extracellular collagen.2 Additionally, bullous fluid from HSP has been noted to have markedly elevated levels of soluble CD23, a form of the CD23 B-cell surface receptor used in antibody feedback regulation and B-cell recruitment, which also has been found to be elevated in the fluid of bullous pemphigoid, suggesting a similar pathogenesis of exaggerated humoral immunity.3

The most common sign of HSP is palpable purpura; however, other cutaneous findings can be present including targetoid plaques, macules, papules, petechiae, and bullae that may become hemorrhagic, ulcerated, necrotic, or scarred.1-6 Bullae appear in the most dependent parts of the body, such as the feet and lower legs. Hydrostatic pressure may play a role in the pathogenesis of this phenomenon.1 When other classic signs of HSP are absent, the presence of bullae clouds the diagnosis and creates controversy regarding treatment, as there is a dearth of literature on proper therapy for severe cutaneous manifestations of HSP.6

Our patient was treated with morphine for pain management along with topical mupirocin and nonadherent dressings for wound care. She also received pulse intravenous methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg daily for 3 days and then was transitioned to oral prednisone 1 mg/kg daily, which was tapered over 3 weeks after discharge. This regimen resulted in resolution of symptoms with rapid regression of bullae and subsequent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Prior reports have noted that the presence of bullae does not alter the prognosis or predict probability of renal involvement of this self-limited disease, leading to controversy in determining if treatment offers more favorable outcomes.1,3 One study suggested that steroids only improve symptoms, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, but they do not aid in the resolution of cutaneous lesions or prevent the progression of renal disease.3 Contrarily, others have suggested that the presence of bullae and renal disease is an indication to start treatment.6 This claim is based on the mechanistic finding that immunosuppression with corticosteroids decreases inflammation by inhibiting activator protein 1, a transcription factor for MMP-9, thereby reducing MMP-9 activity and the formation of bullae.4 Clinical anecdotes, including our own, that demonstrate dramatic improvement of hemorrhagic bullae with the administration of corticosteroids substantiate this mechanism. Through the inhibition of neutrophil interactions and IgA production, other anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medications such as colchicine, dapsone, and azathioprine also have been reported to aid in resolution of the cutaneous lesions.1,5,6 Although there is a clear drawback to the lack of controlled trials and prospective studies regarding the treatment of bullous HSP, it is nearly impossible to expect such studies to be carried out given the rare and unpredictable nature of the disease. For now, claims derived from case series and case reports guide our understanding of treatment efficacy.

Acknowledgment—Quiz photograph courtesy of Steve Taylor, BS, Phoenix, Arizona.

- Trapani S, Mariotti P, Resti M, et al. Severe hemorrhagic bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein purpura: three pediatric cases and review of the literature [published online July 16, 2009]. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1355-1359. doi:10.1007/s00296-009-1055-8.

- Kobayashi T, Sakuraoka K, Iwamoto M, et al. A case of anaphylactoid purpura with multiple blister formation: possible pathophysiologic role of gelatinate (MMP-9). Dermatology. 1990;197:62-64.

- Bansal AS, Dwivedi N, Adsett M. Serum and blister fluid cytokines and complement proteins in a patient with Henoch Schönlein purpura associated with a bullous skin rash. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:190-192.

- Aljada A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, et al. Hydrocortisone suppresses intranuclear activator-protein-1 (AP-1) binding activity in mononuclear cells and plasma matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5988-5991.

- Iqbal H, Evans A. Dapsone therapy for Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a case series. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:985-986.

- den Boer SL, Pasmans SG, Wulffraat NM, et al. Bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein purpura as indication to start systemic prednisone [published online January 5, 2009]. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:781-783. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01650.x.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Laboratory tests in this patient showed no abnormalities for complete blood cell count, immunoglobulins, anti–double-stranded DNA, antinuclear antibody, p–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, Sjögren antibodies, liver enzymes, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Urinalysis was normal. Punch biopsies were obtained and a histologic examination showed an intense inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils around blood vessels within the dermis (Figure). These blood vessels showed swollen endothelium and narrowing of the vessel lumina with leukocytoclasia. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA, C3, fibrin, and weak IgM deposits in blood vessels in the papillary dermis consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is the most common vasculitis in children.1-6 However, its bullous variant is rare, with few pediatric cases reported. Bullous HSP affects arterioles through an IgA-mediated pathway.1-6 It is believed that the bullae are formed secondary to neutrophilic release of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), which degrades extracellular collagen.2 Additionally, bullous fluid from HSP has been noted to have markedly elevated levels of soluble CD23, a form of the CD23 B-cell surface receptor used in antibody feedback regulation and B-cell recruitment, which also has been found to be elevated in the fluid of bullous pemphigoid, suggesting a similar pathogenesis of exaggerated humoral immunity.3

The most common sign of HSP is palpable purpura; however, other cutaneous findings can be present including targetoid plaques, macules, papules, petechiae, and bullae that may become hemorrhagic, ulcerated, necrotic, or scarred.1-6 Bullae appear in the most dependent parts of the body, such as the feet and lower legs. Hydrostatic pressure may play a role in the pathogenesis of this phenomenon.1 When other classic signs of HSP are absent, the presence of bullae clouds the diagnosis and creates controversy regarding treatment, as there is a dearth of literature on proper therapy for severe cutaneous manifestations of HSP.6

Our patient was treated with morphine for pain management along with topical mupirocin and nonadherent dressings for wound care. She also received pulse intravenous methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg daily for 3 days and then was transitioned to oral prednisone 1 mg/kg daily, which was tapered over 3 weeks after discharge. This regimen resulted in resolution of symptoms with rapid regression of bullae and subsequent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Prior reports have noted that the presence of bullae does not alter the prognosis or predict probability of renal involvement of this self-limited disease, leading to controversy in determining if treatment offers more favorable outcomes.1,3 One study suggested that steroids only improve symptoms, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, but they do not aid in the resolution of cutaneous lesions or prevent the progression of renal disease.3 Contrarily, others have suggested that the presence of bullae and renal disease is an indication to start treatment.6 This claim is based on the mechanistic finding that immunosuppression with corticosteroids decreases inflammation by inhibiting activator protein 1, a transcription factor for MMP-9, thereby reducing MMP-9 activity and the formation of bullae.4 Clinical anecdotes, including our own, that demonstrate dramatic improvement of hemorrhagic bullae with the administration of corticosteroids substantiate this mechanism. Through the inhibition of neutrophil interactions and IgA production, other anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medications such as colchicine, dapsone, and azathioprine also have been reported to aid in resolution of the cutaneous lesions.1,5,6 Although there is a clear drawback to the lack of controlled trials and prospective studies regarding the treatment of bullous HSP, it is nearly impossible to expect such studies to be carried out given the rare and unpredictable nature of the disease. For now, claims derived from case series and case reports guide our understanding of treatment efficacy.

Acknowledgment—Quiz photograph courtesy of Steve Taylor, BS, Phoenix, Arizona.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Laboratory tests in this patient showed no abnormalities for complete blood cell count, immunoglobulins, anti–double-stranded DNA, antinuclear antibody, p–antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, Sjögren antibodies, liver enzymes, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Urinalysis was normal. Punch biopsies were obtained and a histologic examination showed an intense inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils around blood vessels within the dermis (Figure). These blood vessels showed swollen endothelium and narrowing of the vessel lumina with leukocytoclasia. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA, C3, fibrin, and weak IgM deposits in blood vessels in the papillary dermis consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP).

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is the most common vasculitis in children.1-6 However, its bullous variant is rare, with few pediatric cases reported. Bullous HSP affects arterioles through an IgA-mediated pathway.1-6 It is believed that the bullae are formed secondary to neutrophilic release of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9), which degrades extracellular collagen.2 Additionally, bullous fluid from HSP has been noted to have markedly elevated levels of soluble CD23, a form of the CD23 B-cell surface receptor used in antibody feedback regulation and B-cell recruitment, which also has been found to be elevated in the fluid of bullous pemphigoid, suggesting a similar pathogenesis of exaggerated humoral immunity.3

The most common sign of HSP is palpable purpura; however, other cutaneous findings can be present including targetoid plaques, macules, papules, petechiae, and bullae that may become hemorrhagic, ulcerated, necrotic, or scarred.1-6 Bullae appear in the most dependent parts of the body, such as the feet and lower legs. Hydrostatic pressure may play a role in the pathogenesis of this phenomenon.1 When other classic signs of HSP are absent, the presence of bullae clouds the diagnosis and creates controversy regarding treatment, as there is a dearth of literature on proper therapy for severe cutaneous manifestations of HSP.6

Our patient was treated with morphine for pain management along with topical mupirocin and nonadherent dressings for wound care. She also received pulse intravenous methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg daily for 3 days and then was transitioned to oral prednisone 1 mg/kg daily, which was tapered over 3 weeks after discharge. This regimen resulted in resolution of symptoms with rapid regression of bullae and subsequent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Prior reports have noted that the presence of bullae does not alter the prognosis or predict probability of renal involvement of this self-limited disease, leading to controversy in determining if treatment offers more favorable outcomes.1,3 One study suggested that steroids only improve symptoms, arthralgia, and abdominal pain, but they do not aid in the resolution of cutaneous lesions or prevent the progression of renal disease.3 Contrarily, others have suggested that the presence of bullae and renal disease is an indication to start treatment.6 This claim is based on the mechanistic finding that immunosuppression with corticosteroids decreases inflammation by inhibiting activator protein 1, a transcription factor for MMP-9, thereby reducing MMP-9 activity and the formation of bullae.4 Clinical anecdotes, including our own, that demonstrate dramatic improvement of hemorrhagic bullae with the administration of corticosteroids substantiate this mechanism. Through the inhibition of neutrophil interactions and IgA production, other anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive medications such as colchicine, dapsone, and azathioprine also have been reported to aid in resolution of the cutaneous lesions.1,5,6 Although there is a clear drawback to the lack of controlled trials and prospective studies regarding the treatment of bullous HSP, it is nearly impossible to expect such studies to be carried out given the rare and unpredictable nature of the disease. For now, claims derived from case series and case reports guide our understanding of treatment efficacy.

Acknowledgment—Quiz photograph courtesy of Steve Taylor, BS, Phoenix, Arizona.

- Trapani S, Mariotti P, Resti M, et al. Severe hemorrhagic bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein purpura: three pediatric cases and review of the literature [published online July 16, 2009]. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1355-1359. doi:10.1007/s00296-009-1055-8.

- Kobayashi T, Sakuraoka K, Iwamoto M, et al. A case of anaphylactoid purpura with multiple blister formation: possible pathophysiologic role of gelatinate (MMP-9). Dermatology. 1990;197:62-64.

- Bansal AS, Dwivedi N, Adsett M. Serum and blister fluid cytokines and complement proteins in a patient with Henoch Schönlein purpura associated with a bullous skin rash. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:190-192.

- Aljada A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, et al. Hydrocortisone suppresses intranuclear activator-protein-1 (AP-1) binding activity in mononuclear cells and plasma matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5988-5991.

- Iqbal H, Evans A. Dapsone therapy for Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a case series. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:985-986.

- den Boer SL, Pasmans SG, Wulffraat NM, et al. Bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein purpura as indication to start systemic prednisone [published online January 5, 2009]. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:781-783. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01650.x.

- Trapani S, Mariotti P, Resti M, et al. Severe hemorrhagic bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein purpura: three pediatric cases and review of the literature [published online July 16, 2009]. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1355-1359. doi:10.1007/s00296-009-1055-8.

- Kobayashi T, Sakuraoka K, Iwamoto M, et al. A case of anaphylactoid purpura with multiple blister formation: possible pathophysiologic role of gelatinate (MMP-9). Dermatology. 1990;197:62-64.

- Bansal AS, Dwivedi N, Adsett M. Serum and blister fluid cytokines and complement proteins in a patient with Henoch Schönlein purpura associated with a bullous skin rash. Australas J Dermatol. 1997;38:190-192.

- Aljada A, Ghanim H, Mohanty P, et al. Hydrocortisone suppresses intranuclear activator-protein-1 (AP-1) binding activity in mononuclear cells and plasma matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 (MMP-2 and MMP-9). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:5988-5991.

- Iqbal H, Evans A. Dapsone therapy for Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a case series. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:985-986.

- den Boer SL, Pasmans SG, Wulffraat NM, et al. Bullous lesions in Henoch Schönlein purpura as indication to start systemic prednisone [published online January 5, 2009]. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:781-783. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01650.x.

A 12-year-old girl presented with an erythematous eruption that had started on the left leg approximately 1 week prior with subsequent spread to the abdomen and arms. She had associated knee pain, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, and nonbloody and nonbilious emesis. Her medical history was notable for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus abscesses, the most recent of which was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; treatment was completed 5 days before the onset of the rash. Family history was notable for her paternal aunt who died of systemic lupus erythematosus. Physical examination showed erythematous macules and purpuric papules with central vesiculation extending up the thighs and lower abdomen associated with edema of the lower extremities and pain after palpation. Tense bullae also were present.

Ladder Becomes Stairway to Urgent Care

Answer

The radiograph shows a compression deformity of the C6 vertebral body. In addition, there is a displaced fracture fragment along the anterior superior endplate. Alignment is adequate, with no evidence of subluxation. The disc space of C6-7 also appears slightly distracted, suggesting possible acute injury.

Given the clinical and radiographic presentation, this patient warranted further workup. He was admitted for CT and MRI of the cervical spine, which demonstrated disc herniation at both the C5-6 and C6-7 levels, as well as interspinous ligament injury.

The patient subsequently underwent a two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. His symptoms resolved, and he was discharged home the next day.

Answer

The radiograph shows a compression deformity of the C6 vertebral body. In addition, there is a displaced fracture fragment along the anterior superior endplate. Alignment is adequate, with no evidence of subluxation. The disc space of C6-7 also appears slightly distracted, suggesting possible acute injury.

Given the clinical and radiographic presentation, this patient warranted further workup. He was admitted for CT and MRI of the cervical spine, which demonstrated disc herniation at both the C5-6 and C6-7 levels, as well as interspinous ligament injury.

The patient subsequently underwent a two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. His symptoms resolved, and he was discharged home the next day.

Answer

The radiograph shows a compression deformity of the C6 vertebral body. In addition, there is a displaced fracture fragment along the anterior superior endplate. Alignment is adequate, with no evidence of subluxation. The disc space of C6-7 also appears slightly distracted, suggesting possible acute injury.

Given the clinical and radiographic presentation, this patient warranted further workup. He was admitted for CT and MRI of the cervical spine, which demonstrated disc herniation at both the C5-6 and C6-7 levels, as well as interspinous ligament injury.

The patient subsequently underwent a two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. His symptoms resolved, and he was discharged home the next day.

A 30-year-old man presents to an urgent care clinic for evaluation of neck pain secondary to an injury he sustained earlier in the day. He was at a construction worksite, on a ladder, approximately eight to 10 feet above the ground. He went to step onto an adjacent ladder and missed. His chin and face struck one of the rungs, and his head went back. Amazingly, he was able to maintain his balance, holding onto the sides of the ladder, sliding down the front, and landing on his feet. He immediately began to experience neck pain, as well as numbness and tingling in both arms (worse on his left side). He was placed in a rigid collar upon arrival to the facility. Medical history is unremarkable except for tobacco use. Vital signs are normal. Physical exam demonstrates some neck pain within the paraspinous muscles. There is some mild midline tenderness within the cervical spine. Of note, the numbness and tingling seem to be worst in his index finger and thumb. You obtain a cervical spine radiograph; the lateral view is shown. What is your impression?

Man Finds Worst Way to Get Out of Shoveling Snow

ANSWER

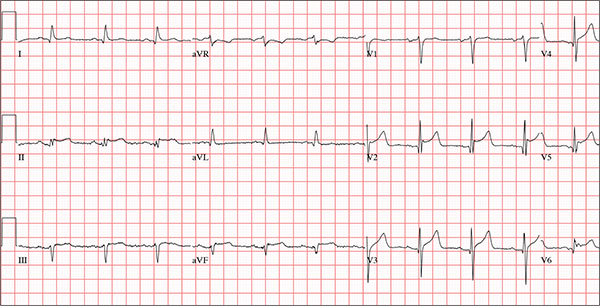

The correct answer is normal sinus rhythm, acute anterior myocardial infarction, and inferolateral injury.

A P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave at a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min are indicative of normal sinus rhythm.

Acute anterior myocardial infarction is evidenced by the significant Q waves and ST elevations in leads I and V2 to V4 and inferolateral injury by ST elevations in limb leads II, III, and aVF and precordial leads V5 and V6.

Subsequent cardiac catheterization revealed an occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, as well as significant lesions in the posterior descending artery and a marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery.

ANSWER

The correct answer is normal sinus rhythm, acute anterior myocardial infarction, and inferolateral injury.

A P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave at a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min are indicative of normal sinus rhythm.

Acute anterior myocardial infarction is evidenced by the significant Q waves and ST elevations in leads I and V2 to V4 and inferolateral injury by ST elevations in limb leads II, III, and aVF and precordial leads V5 and V6.

Subsequent cardiac catheterization revealed an occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, as well as significant lesions in the posterior descending artery and a marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery.

ANSWER

The correct answer is normal sinus rhythm, acute anterior myocardial infarction, and inferolateral injury.

A P wave for every QRS and a QRS for every P wave at a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min are indicative of normal sinus rhythm.

Acute anterior myocardial infarction is evidenced by the significant Q waves and ST elevations in leads I and V2 to V4 and inferolateral injury by ST elevations in limb leads II, III, and aVF and precordial leads V5 and V6.

Subsequent cardiac catheterization revealed an occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, as well as significant lesions in the posterior descending artery and a marginal branch of the circumflex coronary artery.

A 66-year-old man presents with ongoing chest pain of 45 minutes’ duration followed by ventricular fibrillation. He was outside shoveling snow for about 30 minutes before his wife noticed that the sound of shoveling had ceased and her husband was nowhere to be seen. Upon investigation, she found him sitting on the porch, holding his chest and moaning, and she immediately called 911. Paramedics arrived within 10 minutes. When the ambulance pulled into the driveway, the patient stood up and collapsed. The paramedics identified ventricular fibrillation and resuscitated him with a single shock from the automatic external defibrillator. The patient quickly regained consciousness and did not require further intervention. According to the paramedics, the patient was in ventricular fibrillation for less than one minute. Oxygen and anti-angina therapy, started in the field, provided prompt relief of his chest pain. Upon arrival to the emergency department, the patient is awake, stable, and fully cognizant of what happened and where he is. History taking reveals that he has experienced chest pain with exertion for several weeks, beginning around Thanksgiving, but did not want to worry his family during the holiday season. All prior episodes stopped as soon as he ceased physical activity, unlike the one he experienced today. The patient has a history of hypertension but no other cardiac problems. Surgical history is remarkable for a right rotator cuff repair and removal of a melanoma from his nose. Family history is positive for myocardial infarction (both parents and paternal grandfather) and type 1 diabetes (mother). The patient, an only child, has two adult sons, both of whom are in good health. The patient is a retired attorney. He drinks approximately one bottle of wine per week, does not drink beer or hard liquor, and has never smoked. He has been quite active and runs 10K races three or four times per year. He denies recreational or herbal drug use. He currently takes no medications—not even the hydrochlorothiazide and metoprolol prescribed for his hypertension, neither of which he has taken for the past year. He says he occasionally takes ibuprofen for “typical muscle aches and pains.” He has no known drug allergies. The review of systems is unremarkable. The patient denies palpitations, shortness of breath, recent weight gain, and headaches. Physical exam reveals a well-nourished, well-groomed man with a blood pressure of 160/98 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 100% on 2 L of oxygen via nasal cannula; and temperature, 98.2°F. He reports his weight to be 189 lb and his height, 6 ft 2 in. There are no unusual findings: His lungs are clear; his cardiac exam reveals no murmurs, rubs, gallops, or arrhythmia; the abdomen is soft and not tender; there is no peripheral edema; and he is neurologically intact. An ECG, laboratory tests, and an echocardiogram are ordered. You review the ECG while the other tests are pending and note a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, 162 ms; QRS duration, 106 ms; QT/QTc interval, 390/426 ms; P axis, 51°; R axis, –20°; and T axis, 70°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Finding Spot-on Treatment for Acne

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.

Once the unimportance of pizza, makeup, and soft drinks has been established, there remains the opportunity to enlighten the patient (and family) about the factors that do play a significant role—all but one of which can be addressed. (The exception, of course, is heredity; still, I believe it’s important to recognize its role in acne.) We can reduce the amount of sebum through use of retinoids and cut down on bacteria by using oral or topical antibiotics (though erythromycin is not especially effective). Hormonal therapy can be accomplished with oral contraceptives or oral spironolactone, though neither is perfect.

Treatment

This particular patient was prescribed a six-month course of isotretinoin (40 mg/d), after which her acne was completely and permanently gone. This is the result in about 70% of cases when this medicine is used correctly.

Proper procedure, including pregnancy tests and blood work, was followed before the patient was placed on the medication. The decision to use it was made after a careful discussion of other options, most of which she had already exhausted, and of the risks versus benefits of all available choices.

The biggest obstacle to starting the patient on isotretinoin was the perception that the drug is dangerous. It certainly must be used with caution, in carefully selected patients, and after a full disclosure of the associated risks. But when used appropriately, it is an effective treatment for acne that has failed to respond to other medications.

Summary

Acne is an extremely common complaint and happens to be exceedingly well studied. There are numerous treatment options, although none is perfect. Our job is to guide patients and families through the maze of information to plan a course of action acceptable to all.

ANSWER

The correct answer is food (choice “a”), which for many generations has been blamed for worsening acne (along with other nonfactors, such as makeup). All the others are demonstrably involved in the genesis and perpetuation of acne.

DISCUSSION

Teenagers have a hard enough time dealing with acne and other vicissitudes of puberty, and then they get blamed for eating the wrong kinds of food …. Would that it could be that simple! I think it’s important for us as providers to set the record straight by making sure parents and patients know what matters and what doesn’t.

When we’ve done that, the patient (or occasionally a parent) might say, “Well, every time I eat (insert item here), my acne flares.” To which we of course reply, “Well then, don’t do that!” After all, we certainly wouldn’t object to the patient consuming a better diet.