User login

Dry Scaly Rash

The Diagnosis: Phrynoderma

Phrynoderma, meaning “toad skin,” was first described by Nicholls1 in 1933 as a condition due to vitamin A deficiency and characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis. Since then, there has been debate in the literature over the etiology of phrynoderma, as studies have demonstrated different causes for this condition,2-5 which suggests that it is prudent to check several markers of nutritional status including vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin E, and essential fatty acid studies.

Phrynoderma is most commonly seen in South and East Asia with relatively rare occurrences in the United States. Although it characteristically occurs in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years, almost all of the cases reported in the United States have occurred in adults.6,7 A clear gender predilection has not been established.7

Phrynoderma tends to favor the extensor surfaces. In particular, the elbows, thighs, and buttocks are the most commonly affected locations. The face is typically the last site to become involved. On physical examination of a patient with phrynoderma, there are various-sized, discrete, red-brown to flesh-colored papules with a conical keratotic follicular plug (Figure).3 The eruption is often asymptomatic, but mild pruritus may be reported.7 Additional signs of vitamin A deficiency may be present, including night blindness, hyperpigmentation, or xerosis. Patients with phrynoderma also may have evidence of other nutritional deficiencies, such as angular stomatitis, cheilitis, or glossitis. The differential diagnosis for a patient with this type of papular eruption may include pityriasis rubra pilaris, keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, crusted scabies, and follicular lichen planus.7 History and clinical presentation can generally help to distinguish these diagnoses.

Generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption on the chest (A) and abdomen (B). |

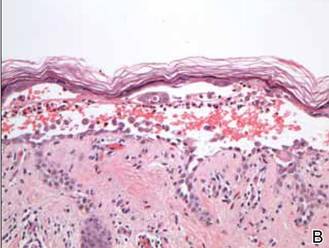

Histopathology typically shows moderate hyperkeratosis with distension of the upper portion of the follicle by large keratotic plugs. Sebaceous glands are greatly reduced in size and may exhibit epithelial atrophy.8,9

A reduced serum vitamin A level can confirm the diagnosis of phrynoderma. Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a vitamin A value of 26 mg/100 dL (reference range, 38–106 mg/100 dL), consistent with his clinical presentation of phrynoderma. Other markers of nutritional status, including vitamins D, E, and K1, were all within reference range. Treatment consists of replacing the nutritional deficit. High doses of vitamin A, such as 200,000 to 500,000 IU daily for 3 to 5 days or daily doses of 2000 to 50,000 IU, can lead to resolution of the rash in 1 to 4 months.8,9 Our patient was started on 10,000 IU of oral vitamin A daily at discharge but unfortunately died a few months later.

Vitamin A has been shown to promote maturation and differentiation of the basal keratinocytes as they move up through the epidermis, which may in part explain why this treatment is effective.10 It is important to be aware of this condition when seeing a patient with follicular hyperkeratosis because even patients in developed countries with malnutrition due to diet or gastrointestinal disease may develop phrynoderma.

- Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: a condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gazette. 1933;68:681-687.

- Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma; histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251-258.

- Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, et al. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):322-324.

- Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: is it an EFA deficiency disease? Euro J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29-39.

- Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29-30.

- Maronn M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: a manifestation of vitamin A deficiency?…the rest of the story. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60-63.

- Ragunatha S, Kumar VJ, Murugesh SB. A clinical study of 125 patients with phrynoderma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:389-392.

- Neill SM, Pembroke AC, du-Vivier AWP, et al. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in a diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171-172.

- Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small-bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73-75.

- Logan WS. Vitamin A and keratinization. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:748-753.

The Diagnosis: Phrynoderma

Phrynoderma, meaning “toad skin,” was first described by Nicholls1 in 1933 as a condition due to vitamin A deficiency and characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis. Since then, there has been debate in the literature over the etiology of phrynoderma, as studies have demonstrated different causes for this condition,2-5 which suggests that it is prudent to check several markers of nutritional status including vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin E, and essential fatty acid studies.

Phrynoderma is most commonly seen in South and East Asia with relatively rare occurrences in the United States. Although it characteristically occurs in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years, almost all of the cases reported in the United States have occurred in adults.6,7 A clear gender predilection has not been established.7

Phrynoderma tends to favor the extensor surfaces. In particular, the elbows, thighs, and buttocks are the most commonly affected locations. The face is typically the last site to become involved. On physical examination of a patient with phrynoderma, there are various-sized, discrete, red-brown to flesh-colored papules with a conical keratotic follicular plug (Figure).3 The eruption is often asymptomatic, but mild pruritus may be reported.7 Additional signs of vitamin A deficiency may be present, including night blindness, hyperpigmentation, or xerosis. Patients with phrynoderma also may have evidence of other nutritional deficiencies, such as angular stomatitis, cheilitis, or glossitis. The differential diagnosis for a patient with this type of papular eruption may include pityriasis rubra pilaris, keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, crusted scabies, and follicular lichen planus.7 History and clinical presentation can generally help to distinguish these diagnoses.

Generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption on the chest (A) and abdomen (B). |

Histopathology typically shows moderate hyperkeratosis with distension of the upper portion of the follicle by large keratotic plugs. Sebaceous glands are greatly reduced in size and may exhibit epithelial atrophy.8,9

A reduced serum vitamin A level can confirm the diagnosis of phrynoderma. Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a vitamin A value of 26 mg/100 dL (reference range, 38–106 mg/100 dL), consistent with his clinical presentation of phrynoderma. Other markers of nutritional status, including vitamins D, E, and K1, were all within reference range. Treatment consists of replacing the nutritional deficit. High doses of vitamin A, such as 200,000 to 500,000 IU daily for 3 to 5 days or daily doses of 2000 to 50,000 IU, can lead to resolution of the rash in 1 to 4 months.8,9 Our patient was started on 10,000 IU of oral vitamin A daily at discharge but unfortunately died a few months later.

Vitamin A has been shown to promote maturation and differentiation of the basal keratinocytes as they move up through the epidermis, which may in part explain why this treatment is effective.10 It is important to be aware of this condition when seeing a patient with follicular hyperkeratosis because even patients in developed countries with malnutrition due to diet or gastrointestinal disease may develop phrynoderma.

The Diagnosis: Phrynoderma

Phrynoderma, meaning “toad skin,” was first described by Nicholls1 in 1933 as a condition due to vitamin A deficiency and characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis. Since then, there has been debate in the literature over the etiology of phrynoderma, as studies have demonstrated different causes for this condition,2-5 which suggests that it is prudent to check several markers of nutritional status including vitamin A, vitamin B, vitamin E, and essential fatty acid studies.

Phrynoderma is most commonly seen in South and East Asia with relatively rare occurrences in the United States. Although it characteristically occurs in children and adolescents aged 5 to 15 years, almost all of the cases reported in the United States have occurred in adults.6,7 A clear gender predilection has not been established.7

Phrynoderma tends to favor the extensor surfaces. In particular, the elbows, thighs, and buttocks are the most commonly affected locations. The face is typically the last site to become involved. On physical examination of a patient with phrynoderma, there are various-sized, discrete, red-brown to flesh-colored papules with a conical keratotic follicular plug (Figure).3 The eruption is often asymptomatic, but mild pruritus may be reported.7 Additional signs of vitamin A deficiency may be present, including night blindness, hyperpigmentation, or xerosis. Patients with phrynoderma also may have evidence of other nutritional deficiencies, such as angular stomatitis, cheilitis, or glossitis. The differential diagnosis for a patient with this type of papular eruption may include pityriasis rubra pilaris, keratosis pilaris, lichen spinulosus, crusted scabies, and follicular lichen planus.7 History and clinical presentation can generally help to distinguish these diagnoses.

Generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption on the chest (A) and abdomen (B). |

Histopathology typically shows moderate hyperkeratosis with distension of the upper portion of the follicle by large keratotic plugs. Sebaceous glands are greatly reduced in size and may exhibit epithelial atrophy.8,9

A reduced serum vitamin A level can confirm the diagnosis of phrynoderma. Our patient’s laboratory results revealed a vitamin A value of 26 mg/100 dL (reference range, 38–106 mg/100 dL), consistent with his clinical presentation of phrynoderma. Other markers of nutritional status, including vitamins D, E, and K1, were all within reference range. Treatment consists of replacing the nutritional deficit. High doses of vitamin A, such as 200,000 to 500,000 IU daily for 3 to 5 days or daily doses of 2000 to 50,000 IU, can lead to resolution of the rash in 1 to 4 months.8,9 Our patient was started on 10,000 IU of oral vitamin A daily at discharge but unfortunately died a few months later.

Vitamin A has been shown to promote maturation and differentiation of the basal keratinocytes as they move up through the epidermis, which may in part explain why this treatment is effective.10 It is important to be aware of this condition when seeing a patient with follicular hyperkeratosis because even patients in developed countries with malnutrition due to diet or gastrointestinal disease may develop phrynoderma.

- Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: a condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gazette. 1933;68:681-687.

- Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma; histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251-258.

- Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, et al. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):322-324.

- Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: is it an EFA deficiency disease? Euro J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29-39.

- Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29-30.

- Maronn M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: a manifestation of vitamin A deficiency?…the rest of the story. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60-63.

- Ragunatha S, Kumar VJ, Murugesh SB. A clinical study of 125 patients with phrynoderma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:389-392.

- Neill SM, Pembroke AC, du-Vivier AWP, et al. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in a diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171-172.

- Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small-bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73-75.

- Logan WS. Vitamin A and keratinization. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:748-753.

- Nicholls L. Phrynoderma: a condition due to vitamin deficiency. Indian Med Gazette. 1933;68:681-687.

- Bagchi K, Halder K, Chowdhury SR. The etiology of phrynoderma; histologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 1959;7:251-258.

- Bleasel NR, Stapleton KM, Lee MS, et al. Vitamin A deficiency phrynoderma: due to malabsorption and inadequate diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):322-324.

- Ghafoorunissa, Vidyasagar R, Krishnaswamy K. Phrynoderma: is it an EFA deficiency disease? Euro J Clin Nutr. 1988;42:29-39.

- Shrank AB. Phrynoderma. Br Med J. 1966;1:29-30.

- Maronn M, Allen DM, Esterly NB. Phrynoderma: a manifestation of vitamin A deficiency?…the rest of the story. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:60-63.

- Ragunatha S, Kumar VJ, Murugesh SB. A clinical study of 125 patients with phrynoderma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:389-392.

- Neill SM, Pembroke AC, du-Vivier AWP, et al. Phrynoderma and perforating folliculitis due to vitamin A deficiency in a diabetic. J R Soc Med. 1988;81:171-172.

- Wechsler HL. Vitamin A deficiency following small-bowel bypass surgery for obesity. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:73-75.

- Logan WS. Vitamin A and keratinization. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:748-753.

A 22-year-old man with a history of severe mental retardation, a questionable diagnosis of cystic fibrosis, chronic abdominal pain, and a recent diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis was transferred from an outside hospital for worsening abdominal pain, lethargy, anasarca, anorexia, and constipation. An abdominal paracentesis and computed tomography scan of the abdomen were both negative for any acute processes. Blood cultures and paracentesis fluid cultures were negative. The dermatology section was consulted for a dry scaly rash of unknown duration. The eruption had not been treated, and the patient’s dermatologic history was otherwise unremarkable. On physical examination, the patient had a generalized follicular, erythematous, and scaly papular eruption with some areas of yellow-colored hyperkeratotic papules and plaques as well as scattered hemorrhagic crusts on the extensor surface of the right arm. He had normal oral mucosa and nails. The team was unable to gain consent for biopsy, but a blood test was obtained.

Diffuse Crusting of the Skin

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

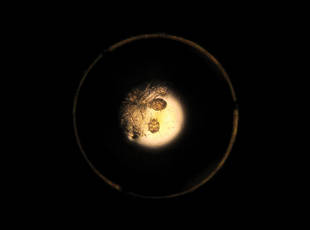

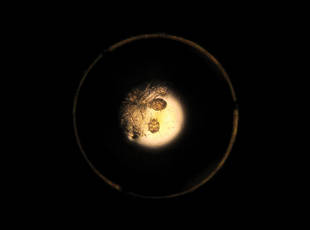

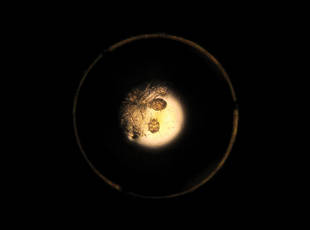

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|  |

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|  |

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

The Diagnosis: Crusted Scabies

Approximately 1 year prior to presentation the patient completed a course of therapy comprised of repeat doses of ivermectin and permethrin for crusted scabies. He stated that the crusts had recurred shortly after treatment (Figure 1). The initial differential diagnosis included crusted scabies, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and psoriasis. Scraping from the interdigital web space (Figure 2) revealed multiple scabies mites, scabella, and ova (Figure 3). The patient was diagnosed with crusted scabies. Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count of 7300/μL, with an elevated eosinophil count of 1900/μL (reference range, <500/μL). Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) was found to be positive. Serum protein electrophoresis showed a moderate polyclonal increase in gamma globulins. Treatment was promptly initiated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the whole body for a total of 2 treatments that were administered 7 days apart. Ivermectin also was started at 200 μg/kg and was given on days 1, 7, 14, and 29. Salicylic acid cream 25% was applied daily to help hasten resolution of the crusts.

|  |

Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 is endemic to Japan, Central and South America, the Middle East, and regions of Africa and the Caribbean.1 Multiple cases of HTLV-1 associated with crusted scabies have been reported in endemic areas.2-6 In the present case, we encountered a patient with crusted scabies and HTLV-1 in a nonendemic area.

Cases of HTLV-1 and crusted scabies have been reported in Brazil, Peru, and Central Australia.3,4,7 A retrospective study in Brazil showed a notable association between HTLV-1 infection and crusted scabies; of 23 patients with crusted scabies, 21 were HTLV-1 positive.3 In another small study from Peru, 23 patients with crusted scabies were tested for HTLV-1 and 16 (70%) were seropositive.4 Neither study had a control group for comparison; however, interestingly, the estimated seroprevalence in the general population (based on blood donors) is only 0.04% to 1% and 1.2% to 1.7% in Brazil and Peru, respectively, thus reinforcing the association between HTLV-1 and crusted scabies.1 Crusted scabies and HTLV-1 seropositivity acting as a predictor for adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) has been reported8 but not consistently.3 Our patient had abnormal serum protein electrophoresis findings. Although the results were not diagnostic of ATL, patients with HTLV-1 are at increased risk for ATL and the pres-ence of this virus is important to document when there is a high index of suspicion for ATL, as with crusted scabies.

Our patient resided in the northeastern United States and there was no evidence in support of underlying immunosuppression. This case of crusted scabies is unique because the patient was HTLV-1 positive without other underlying immunocompromise and he resided in a region where HTLV-1 is nonendemic. In light of these findings, the present case serves as a reminder to check for HTLV-1 infection in those patients with severe or crusted scabies and without an identifiable reason for immunosuppression, even if the patient resides in an area that is nonendemic for HTLV-1.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

- Gessain A, Cassar O. Epidemiological aspects and world distribution of HTLV-1 infection. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:388.

- Nobre V, Guedes AC, Martins ML, et al. Dermatological findings in 3 generations of a family with a high prevalence of human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 infection in Brazil. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1257-1263.

- Brites C, Weyll M, Pedroso C, et al. Severe and Norwegian scabies are strongly associated with retroviral (HIV-1/HTLV-1) infection in Bahia, Brazil. AIDS. 2002;16:1292-1293.

- Blas M, Bravo F, Castillo W, et al. Norwegian scabies in Peru: the impact of human T cell lymphotropic virus type I infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:855-857.

- Bergman JN, Dodd WA, Trotter MJ, et al. Crusted scabies in association with human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. J Cutan Med Surg. 1999;3:148-152.

- Daisley H, Charles W, Suite M. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies as a pre-diagnostic indicator for HTLV-1 infection. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:295.

- Mollison LC. HTLV-I and clinical disease correlates in central Australian aborigines. Med J Aust. 1994;160:238.

- del Giudice P, Sainte Marie D, Gérard Y, et al. Is crusted (Norwegian) scabies a marker of adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma in human T lymphotropic virus type I–seropositive patients? J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1090-1092.

An 82-year-old white man who resided in the northeastern United States was admitted to the hospital for weakness. He was evaluated for diffuse crusting of the skin including the face. The patient reported a history of minimally itchy, generalized crusts of 10 years’ duration. He lived alone with one cat. His medications included fluticasone furoate, terazosin, and levothyroxine sodium. Human immunodeficiency virus screening was negative. A scraping was taken from one of the thick crusts within an interdigital web space.

Parents Frightened by Son’s Thigh Lesion

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

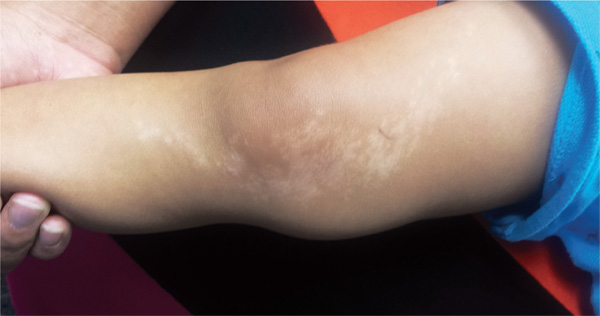

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

A 6-year-old boy is brought in by his mother, referred to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his right thigh that manifested three months ago. Although asymptomatic, the lesion has frightened the boy’s parents. They first took him to a local urgent care clinic, where a diagnosis of “probable fungal infection” was made. But twice-daily application of the prescribed ketoconazole cream did not produce results. The boy is otherwise healthy, although he does have seasonal allergies. There is no family history of skin problems. The affected site is a hypopigmented linear patch of skin from the mid-medial right thigh to the mid-medial calf area. The width of the patch varies, from 3 to 5 cm. The margins are somewhat irregular, and in several places, slightly rough, scaly sections are noted. The hypopigmentation, though partial, is evident in the context of the boy’s type IV Hispanic skin. No erythema or edema is noted. Elsewhere, the child’s skin is free of significant changes or lesions.

Interpretation: Humans, 1; Machine, 0

ANSWER

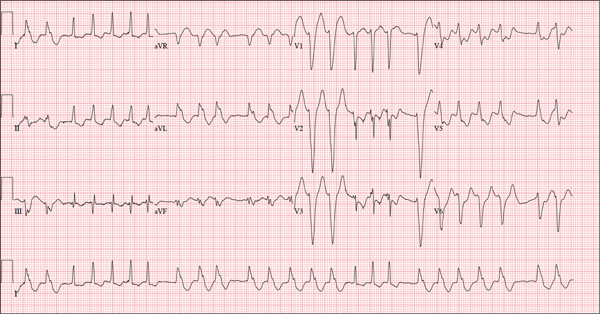

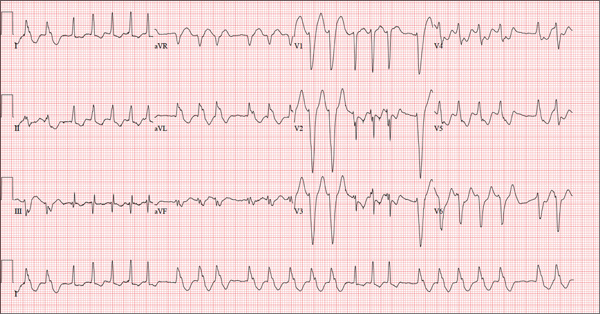

The correct interpretation of this ECG is atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and aberrantly conducted QRS complexes. The latter were misinterpreted as ventricular tachycardia. Although they represent a wide complex at a rate of more than 100 beats/min, the rhythm is irregular and the intrinsic (initial) inflection of normally conducted and aberrant beats is the same. (See lead I rhythm strip at bottom.)

What is unusual (and doesn’t make sense) regarding this ECG is the machine’s reading of the PR interval (128 ms) and the QRS duration (88 ms). For one thing, there is no measurable PR interval. And for another, the measured QRS duration accounts for the normally conducted complex and not the aberrantly conducted ones.

The technician was reassured, and the patient underwent successful cardioversion back to normal sinus rhythm.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG is atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and aberrantly conducted QRS complexes. The latter were misinterpreted as ventricular tachycardia. Although they represent a wide complex at a rate of more than 100 beats/min, the rhythm is irregular and the intrinsic (initial) inflection of normally conducted and aberrant beats is the same. (See lead I rhythm strip at bottom.)

What is unusual (and doesn’t make sense) regarding this ECG is the machine’s reading of the PR interval (128 ms) and the QRS duration (88 ms). For one thing, there is no measurable PR interval. And for another, the measured QRS duration accounts for the normally conducted complex and not the aberrantly conducted ones.

The technician was reassured, and the patient underwent successful cardioversion back to normal sinus rhythm.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG is atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response and aberrantly conducted QRS complexes. The latter were misinterpreted as ventricular tachycardia. Although they represent a wide complex at a rate of more than 100 beats/min, the rhythm is irregular and the intrinsic (initial) inflection of normally conducted and aberrant beats is the same. (See lead I rhythm strip at bottom.)

What is unusual (and doesn’t make sense) regarding this ECG is the machine’s reading of the PR interval (128 ms) and the QRS duration (88 ms). For one thing, there is no measurable PR interval. And for another, the measured QRS duration accounts for the normally conducted complex and not the aberrantly conducted ones.

The technician was reassured, and the patient underwent successful cardioversion back to normal sinus rhythm.

A 72-year-old woman with recurring palpitations and a rapid heart rate presents for evaluation stating that her heart started racing early yesterday morning. It began while she was sleeping, which is normal for her, but while the problem usually resolves within hours, this time it lasted longer. She had an MI about seven years ago, at which time she was told she had atrial fibrillation. Since then, she has had multiple episodes requiring cardioversion and suspects that is what is required this time. She has brought along a copy of her baseline ECG, which shows normal sinus rhythm, an old inferior MI, and an intraventricular conduction delay. Her history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Surgical history is remarkable for coronary stenting (right coronary artery, first diagonal coronary artery, and an obtuse marginal coronary artery). She also has a remote history of hysterectomy and appendectomy. Her current medications include metoprolol, atorvastatin, amiodarone, metformin, and glyburide; she takes an OTC stool softener daily. She is allergic to sulfa. The patient, a retired schoolteacher and the matriarch of her church, is married and has two grown children. She has two siblings, both of whom have diabetes and hypertension. She smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day until her MI, at which point she quit. She does not drink alcohol and has never used recreational drugs. Review of systems is positive for increasingly worsening eyesight, particularly halos around lights at night; she says she was told this might happen when she started taking amiodarone. She has intermittent episodes of diarrhea that she attributes to the stool softener, adding that she considers this consequence “better than the alternative.” The rest of the review is unremarkable. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 148/92 mm Hg; pulse, 140 beats/min and irregular; temperature, 98.4°F; and O2 saturation, 97% on room air. She is 64 in tall and weighs 169 lb. Physical exam reveals a very spry-appearing woman in no distress; in fact, she jokingly complains that she’s too young to have “old people’s diseases” and proudly points out that she has no symptoms of arthritis or dementia. She wears corrective lenses and hearing aids. The exam reveals no thyromegaly or jugular venous distention; clear lung fields; and an irregularly irregular heart rate of 146 beats/min. Her heart rate is too rapid to assess for murmurs or extra heart sounds. The abdomen is benign, and the patient has strong bilateral peripheral pulses in all extremities. The neurologic exam is intact. Suspecting that the patient is in atrial fibrillation, you ask the new ECG technician to obtain a reading. Five minutes later, he calls for help because “the patient is in ventricular tachycardia.” But when you walk into the room, the patient looks quite comfortable on the exam table and exhibits no distress. Reviewing the ECG, you note a ventricular rate of 152 beats/min; PR interval, 128 ms; QRS duration, 88 ms; QT/QTc interval, 280/445 ms; P axis, 27°; R axis, 23°; and T axis, 232°. What is your interpretation of this ECG—and what findings are inconsistent with the machine’s “interpretation”?

Elective Craniotomy Results in Respiratory Distress

ANSWER

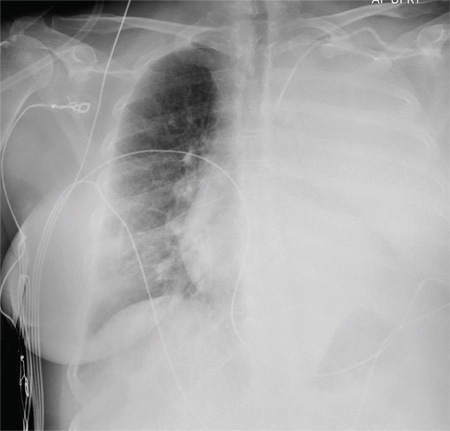

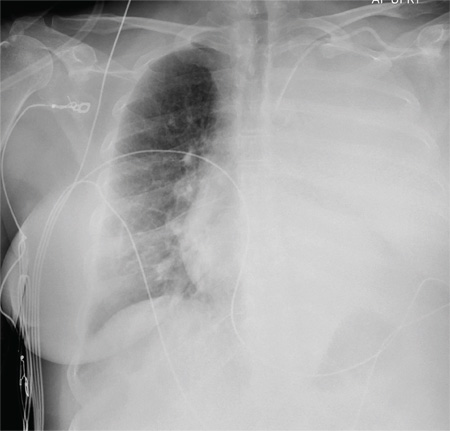

The radiograph shows complete opacification of the left hemithorax. The differential includes total atelectasis of the lung, mucus plug within the left bronchus, or possible blood or fluid collection. Of note, the patient has a catheter within the left subclavian vein, the distal tip of which appears to be in an unusual location. In this case, it was determined that the displaced catheter tip, resulting in hemothorax, was the etiology. The line was removed, and urgent cardiothoracic consultation was obtained. A left chest tube was promptly placed, with a resultant 2 L of immediate output. The patient improved clinically as well.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows complete opacification of the left hemithorax. The differential includes total atelectasis of the lung, mucus plug within the left bronchus, or possible blood or fluid collection. Of note, the patient has a catheter within the left subclavian vein, the distal tip of which appears to be in an unusual location. In this case, it was determined that the displaced catheter tip, resulting in hemothorax, was the etiology. The line was removed, and urgent cardiothoracic consultation was obtained. A left chest tube was promptly placed, with a resultant 2 L of immediate output. The patient improved clinically as well.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows complete opacification of the left hemithorax. The differential includes total atelectasis of the lung, mucus plug within the left bronchus, or possible blood or fluid collection. Of note, the patient has a catheter within the left subclavian vein, the distal tip of which appears to be in an unusual location. In this case, it was determined that the displaced catheter tip, resulting in hemothorax, was the etiology. The line was removed, and urgent cardiothoracic consultation was obtained. A left chest tube was promptly placed, with a resultant 2 L of immediate output. The patient improved clinically as well.

A 60-year-old woman undergoes an elective craniotomy for clipping of a nonruptured aneurysm. The perioperative course is uneventful, and the aneurysm is clipped without complication. The patient is extubated and sent to the recovery room. Within 30 minutes, you are notified by the nurse that the patient is experiencing moderate respiratory distress. There are no neurologic deficits. Her medical history includes hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and coronary artery disease, with previous stenting. Preoperative medical and cardiac clearance for the craniotomy had been obtained. Examination reveals the patient to be in a postanesthetic state, with mild-to-moderate dyspnea and tachypnea. She appears to be moving all of her extremities well. Her O2 saturation is 92% on 100% oxygen via a nonrebreather mask. Her breath sounds are significantly diminished on the left side. A stat portable chest radiograph is obtained. What is your impression?

Fall From Trail Leaves Woman in Pain

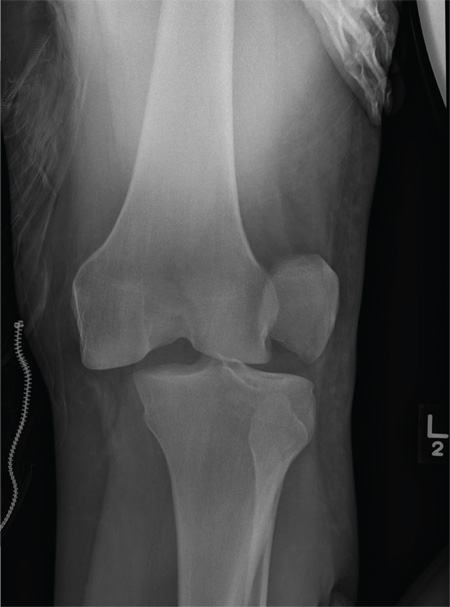

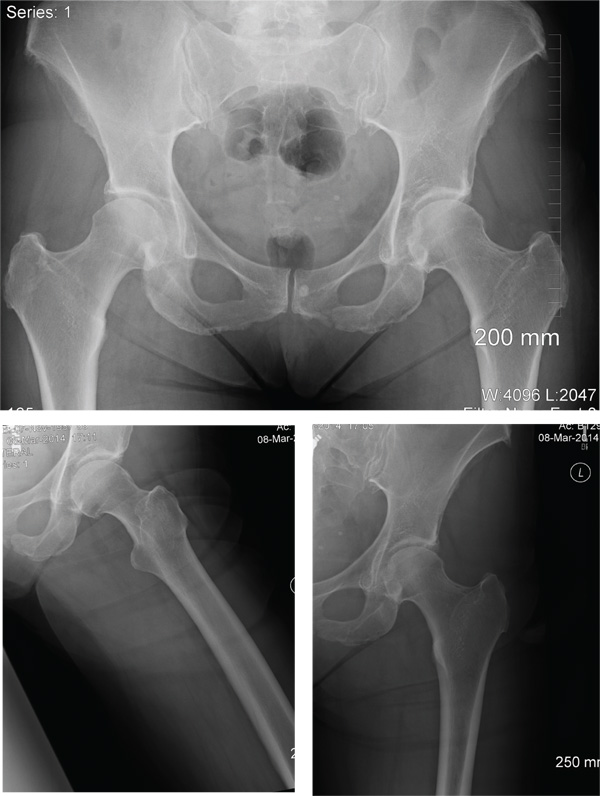

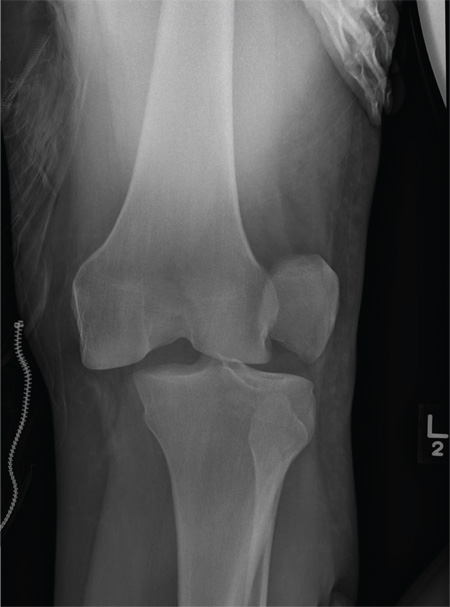

ANSWER

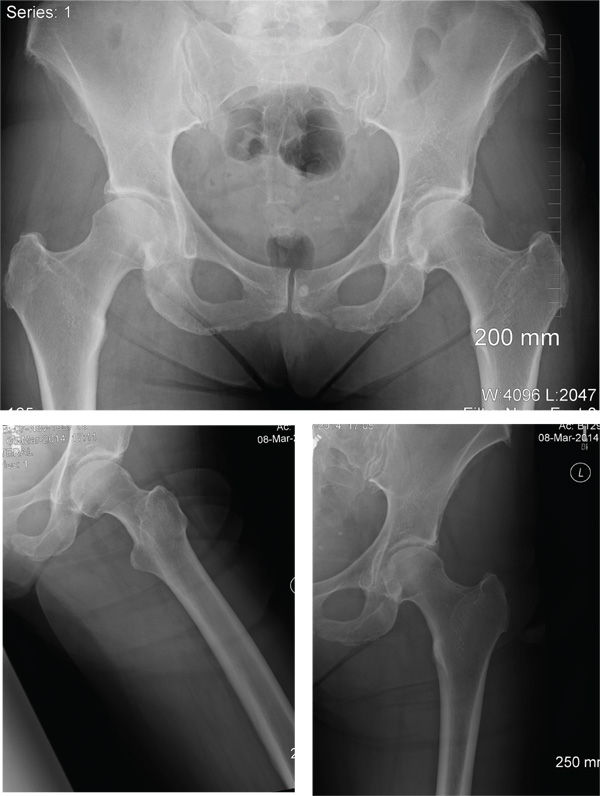

The radiographs demonstrate a left inferior pubic ramus fracture. The patient was referred to orthopedics for follow-up. She was given a walker and a series of home exercises for hip stretching and strengthening, as well as anti-inflammatories as needed for discomfort. She was scheduled for a four-week follow-up visit and repeat radiographs of the pelvis.

ANSWER

The radiographs demonstrate a left inferior pubic ramus fracture. The patient was referred to orthopedics for follow-up. She was given a walker and a series of home exercises for hip stretching and strengthening, as well as anti-inflammatories as needed for discomfort. She was scheduled for a four-week follow-up visit and repeat radiographs of the pelvis.

ANSWER

The radiographs demonstrate a left inferior pubic ramus fracture. The patient was referred to orthopedics for follow-up. She was given a walker and a series of home exercises for hip stretching and strengthening, as well as anti-inflammatories as needed for discomfort. She was scheduled for a four-week follow-up visit and repeat radiographs of the pelvis.

A 56-year old woman presents for evaluation of left hip pain. Several hours ago, she says, she was walking on a trail when she fell from an embankment. The 4-ft fall ended with her landing primarily on her left hip and elbow. Afterward, she was able to ambulate with assistance but noticed increased pain in her left hip and groin with movement. The elbow discomfort resolved shortly after the incident. She denies numbness or tingling in her extremities and loss of bowel or bladder function. Physical exam reveals a well-developed, well-nourished female without any extremity deformity or leg shortening. Palpation elicits left-sided groin pain, as well as left posterior hip and sacroiliac joint pain. Both active and passive range-of-motion of the hip elicit pain, but straight-leg raise does not. The patient can bear weight on the left leg with the assistance of a walker. There is no laxity in the knee joint, and the ankle mortise is stable. There are no signs of swelling or bruising, and the skin is intact. Dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses are 2+, and sensation in the left foot is intact. Radiographs of the left hip and pelvis are obtained. What is your impression?

Clustered Vesicles in a Blaschkoid Pattern

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

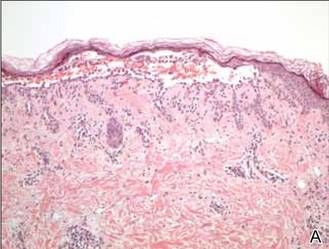

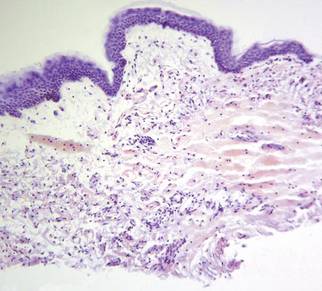

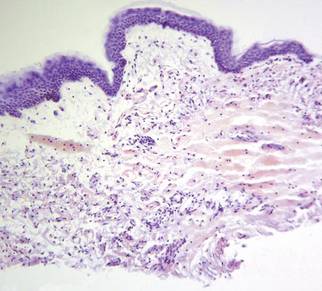

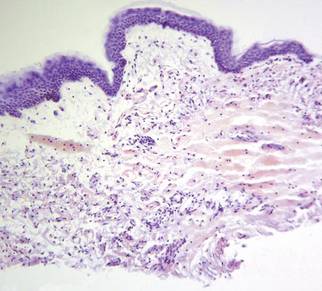

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

The Diagnosis: Linear Vesiculobullous Keratosis Follicularis (Darier Disease)

Darier disease (DD), or keratosis follicularis, is typically an autosomal-dominant disorder that is characterized by greasy hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into warty plaques with a predilection for seborrheic areas. The lesions usually are pruritic; malodorous; and may be exacerbated by sunlight, heat, or sweating. Darier disease may be accompanied by oral mucosal involvement including fine white papules on the palate.1 The condition also can be accompanied by hand and nail involvement (95% of cases) including palmar pitting, punctate keratoses, hemorrhagic macules, palmoplantar keratoderma, and acrokeratosis verruciformis–like lesions on the dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. Nail changes predominately occur on the fingers, manifesting as longitudinal splitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, or characteristic white and red longitudinal bands with V-shaped nicks at the free margin of the nail. In linear DD, hand and nail involvement is rare and, when present, ipsilateral to the primary lesions.1,2

The clinical variants of DD are classified by lesion morphology or distribution, or both. Morphological variants include vesiculobullous, cornified, erosive, acral hemorrhagic, and guttate leukodermic macular.1,2 The clinical features of chronic relapsing vesicular lesions and histologic findings described in this case are consistent with vesiculobullous DD, though genetic testing was not performed.3,4 As in our case, some patients lack a family history and the disease is thought to be the result of genetic mosaicism or somatic postzygotic mutations that affect a limited number of cells. These mosaic variants are named by their cutaneous distribution (ie, linear, segmental, unilateral, localized) and tend to course along the Blaschko lines, most commonly on the trunk. Studies have shown various types of mutations specific to the ATP2A2 gene in the affected tissue but not in the unaffected skin.5 This gene encodes for sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum ATPase SERCA2, which is responsible for intracellular calcium signaling. These mosaic forms of DD are unlikely to be inherited by offspring, in contrast to patients with mosaic epidermal nevi with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis who have a high likelihood of having children with generalized epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.6

Darier disease is a chronic incurable disease. Topical corticosteroid, retinoid, 5-fluorouracil, keratolytics, and laser ablation or excision are used in mild and limited disease with mixed outcomes.7 Oral retinoids are effective in severe or systemic cases of DD by inhibiting hyperkeratosis.8 Individuals with DD are predisposed to infection, warranting regular surveillance and use of antimicrobials and bleach baths. In addition to prophylaxis for bacterial superinfection, patients also are predisposed to getting disseminated herpes simplex virus in the form of eczema herpeticum.

In our patient, the diagnosis was confirmed by performing a punch biopsy from one of the vesicular lesions. Histopathologic examination revealed suprabasal acantholytic dyskeratosis with superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammation with eosinophils (Figure). Immunohistochemical staining showed no evidence of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2.

Histopathology revealed suprabasal acantholysis forming an intraepidermal cleft with superficial perivascular inflammation (A)(H&E, original magnification ×100) and acantholysis with dyskeratotic keratinocytes floating within the intraepidermal cleft (B)(H&E, original magnification ×200). |

Our patient was prescribed tretinoin cream 0.1% daily and was advised to use sun protection and stop valacyclovir. At follow-up she noted decreased frequency of outbreaks after starting the tretinoin cream and the patient has now been free of any outbreaks for 8 months.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

1. Burge SM, Wilkinson JD. Darier-White disease: a review of the clinical features in 163 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:40-50.

2. Cooper SM, Burge SM. Darier’s disease: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:97-105.

3. Kakar B, Kabir S, Garg VK, et al. A case of bullous Darier’s disease histologically mimicking Hailey-Hailey disease. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:28.

4. Telfer NR, Burge SM, Ryan TJ. Vesiculo-bullous Darier’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1990;122:831-834.

5. Sakuntabhai A, Dhitavat J, Burge SM, et al. Mosaicism for ATP2A2 mutations causes segmental Darier’s disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:1144-1147.

6. O’Malley MP, Haake A, Goldsmith L, et al. Localized Darier disease. implications for genetic studies. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:1134-1138.

7. Le Bidre E, Delage M, Celerier P, et al. Efficacy and risks of topical 5-fluorouracil in Darier’s disease. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:455-459.

8. Abe M, Yasuda M, Yokoyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of combination therapy with tacalcitol lotion associated with sunscreen for localized Darier’s disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:718-721.

A 42-year-old woman presented with an intermittent nontender and minimally pruritic rash localized to the left side of the trunk of 20 years’ duration. Four to 6 times per year blisters would develop and then resolve after 1 to 2 weeks with mildly pruritic brown patches. These patches would resolve within approximately 4 weeks. Most notably, the condition was exacerbated by sunlight and heat, though stress sometimes led to an outbreak of vesicles. The patient reported that the eruption, which she was told was recurrent shingles, would improve with oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and did not improve with topical steroid usage. She never had antecedent or concurrent fevers, shortness of breath, arthralgia, or cold sores. There was no family history of any blistering skin conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa, pemphigus, Darier disease, or bullous pemphigoid. Her partner also did not have a history of similar rashes, and the patient denied any history of travel outside of England and the southwestern United States. Initial physical examination revealed clustered vesicles surrounded by brown-pink patches in a blaschkoid pattern spanning from the anterior to posterior aspects of the left flank. Notably, the patient had no oral lesions and no changes of the hair or nails.

Erythematous Papules and Plaques on the Flank of a Child

The Diagnosis: Asymmetric Periflexural Exanthem of Childhood (Unilateral Laterothoracic Exanthem)

Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), also known as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem, is a self-limited eruptive dermatosis that occurs most frequently in infants and young children. The term unilateral laterothoracic exanthem was first coined by Bodemer and de Prost1 in 1992 due to its characteristic distribution. The eruption occurs in children aged 4 months to 10 years, with most cases presenting between 2 and 3 years of age.2 Isolated cases also have been reported in adults.3 It affects girls more often than boys (2:1), and the majority of reported cases have occurred in white individuals. The disease is seen throughout Europe and North America, and seasonal variation has been noted with most cases occurring in late winter and early spring.4,5

|

Clinically, APEC is characterized by its asymmetric localization and unilateral onset. In the majority of patients, the eruption presents as discrete erythematous papules that coalesce to form morbilliform plaques that may have reticular or annular configuration (Figure).4 The exanthem begins unilaterally near a flexural area, most commonly the axilla (75% of cases), and spreads centrifugally to the adjacent trunk and proximal extremity. There is no right or left dominance.4,6 There is eventual involvement of the contralateral side in 70% of cases, but a unilateral predominance is maintained throughout the disease course.4 Rarely, the eruption may involve the face, genitals, and palmoplantar surfaces. As in our case, up to three-quarters of affected children report symptoms of an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal prodrome, including mild fever, diarrhea, and rhinitis.4 Accompanying regional lymphadenopathy has been reported in the majority of cases, and mild to moderate pruritus is not uncommon. The syndrome is self-limited, with spontaneous resolution commonly occurring 3 to 6 weeks after onset. Although no treatment is required, systemic antihistamines and topical steroids have been used to alleviate pruritus in symptomatic patients. Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily as well as oral diphenhydramine 25 mg every 6 hours as needed for associated pruritus. The eruption spontaneously resolved over the following 4 weeks.

Although the cause of APEC remains unknown, an infectious etiology has been presumed. The seasonal pattern, lack of efficacy of broad-spectrum antibiotics, frequently reported prodromal symptoms, and reports of familial cases suggest a viral etiology.1 Additionally, the predilection to affect infants and young children as well as lack of recurrence in the same patient suggests that immunity may develop. Although no etiologic agent has been consistently detected, several reports have suggested a possible relationship to parvovirus B19.7,8 Parainfluenzavirus 2, parainfluenzavirus 3, and adenovirus also have been isolated but may represent incidental viral infection.2 An inoculation dermatosis from an arthropod bite also has been suggested, but this claim has not been substantiated.1

The diagnosis often can be made on clinical features alone, and histopathologic evaluation is not required. Histologic features are nonspecific and include a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, often involving the dermal eccrine ducts without involvement of the secretory coils.4,6 Mild lichenoid changes as well as spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes into the acrosyringium also may be present.4 The clinical differential diagnosis of APEC includes allergic contact dermatitis, a nonspecific drug or viral eruption, atypical pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scabies, tinea corporis, and Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood lacks the peripheral scale present in tinea corporis or pityriasis rosea, but when an annular or reticular configuration predominates, a potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings can exclude the presence of a dermatophyte. Similar to APEC, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome affects young children, is preceded by symptoms of a viral prodrome, and spontaneously resolves over several weeks. This condition is distinguished from APEC by the presence of papulovesicles located symmetrically on the face, buttocks, and extensor surface of the extremities, which largely spare the trunk.

Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood is a unique morbilliform eruption of infants and young children characterized by a stereotypical distribution and self-limited course. The cause of this syndrome remains unclear, but most authors suggest a viral etiology. Recognition of this entity and an ability to distinguish it from other common pediatric dermatoses is required to provide reassurance to parents and avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures and treatments.

1. Bodemer C, de Prost Y. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem in children: a new disease? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):693-696.

2. Nahm WK, Paiva C, Golomb C, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema of childhood: a case involving a 4-month-old infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:461-462.

3. Chan PK, To KF, Zawar V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthema in an adult. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:320-321.

4. McCuaig CC, Russo P, Powell J, et al. Unilateral laterothoracic exanthem. a clinicopathologic study of forty-eight patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:979-984.

5. Taieb A, Megraud F, Legrain V, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:391-393.

6. Coustou D, Léauté-Labrèze C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood. a clinical, pathologic, and epidemiologic prospective study. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:799-803.

7. Guimerá-Martín-Neda F, Fagundo E, Rodríguez F, et al. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood: report of two cases with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:461-462.

8. Pauluzzi P, Festini G, Gelmetti C. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood in an adult patient with parvovirus B19. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:372-374.

The Diagnosis: Asymmetric Periflexural Exanthem of Childhood (Unilateral Laterothoracic Exanthem)

Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), also known as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem, is a self-limited eruptive dermatosis that occurs most frequently in infants and young children. The term unilateral laterothoracic exanthem was first coined by Bodemer and de Prost1 in 1992 due to its characteristic distribution. The eruption occurs in children aged 4 months to 10 years, with most cases presenting between 2 and 3 years of age.2 Isolated cases also have been reported in adults.3 It affects girls more often than boys (2:1), and the majority of reported cases have occurred in white individuals. The disease is seen throughout Europe and North America, and seasonal variation has been noted with most cases occurring in late winter and early spring.4,5

|

Clinically, APEC is characterized by its asymmetric localization and unilateral onset. In the majority of patients, the eruption presents as discrete erythematous papules that coalesce to form morbilliform plaques that may have reticular or annular configuration (Figure).4 The exanthem begins unilaterally near a flexural area, most commonly the axilla (75% of cases), and spreads centrifugally to the adjacent trunk and proximal extremity. There is no right or left dominance.4,6 There is eventual involvement of the contralateral side in 70% of cases, but a unilateral predominance is maintained throughout the disease course.4 Rarely, the eruption may involve the face, genitals, and palmoplantar surfaces. As in our case, up to three-quarters of affected children report symptoms of an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal prodrome, including mild fever, diarrhea, and rhinitis.4 Accompanying regional lymphadenopathy has been reported in the majority of cases, and mild to moderate pruritus is not uncommon. The syndrome is self-limited, with spontaneous resolution commonly occurring 3 to 6 weeks after onset. Although no treatment is required, systemic antihistamines and topical steroids have been used to alleviate pruritus in symptomatic patients. Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily as well as oral diphenhydramine 25 mg every 6 hours as needed for associated pruritus. The eruption spontaneously resolved over the following 4 weeks.

Although the cause of APEC remains unknown, an infectious etiology has been presumed. The seasonal pattern, lack of efficacy of broad-spectrum antibiotics, frequently reported prodromal symptoms, and reports of familial cases suggest a viral etiology.1 Additionally, the predilection to affect infants and young children as well as lack of recurrence in the same patient suggests that immunity may develop. Although no etiologic agent has been consistently detected, several reports have suggested a possible relationship to parvovirus B19.7,8 Parainfluenzavirus 2, parainfluenzavirus 3, and adenovirus also have been isolated but may represent incidental viral infection.2 An inoculation dermatosis from an arthropod bite also has been suggested, but this claim has not been substantiated.1

The diagnosis often can be made on clinical features alone, and histopathologic evaluation is not required. Histologic features are nonspecific and include a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, often involving the dermal eccrine ducts without involvement of the secretory coils.4,6 Mild lichenoid changes as well as spongiosis with exocytosis of lymphocytes into the acrosyringium also may be present.4 The clinical differential diagnosis of APEC includes allergic contact dermatitis, a nonspecific drug or viral eruption, atypical pityriasis rosea, miliaria, scabies, tinea corporis, and Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood lacks the peripheral scale present in tinea corporis or pityriasis rosea, but when an annular or reticular configuration predominates, a potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scrapings can exclude the presence of a dermatophyte. Similar to APEC, Gianotti-Crosti syndrome affects young children, is preceded by symptoms of a viral prodrome, and spontaneously resolves over several weeks. This condition is distinguished from APEC by the presence of papulovesicles located symmetrically on the face, buttocks, and extensor surface of the extremities, which largely spare the trunk.

Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood is a unique morbilliform eruption of infants and young children characterized by a stereotypical distribution and self-limited course. The cause of this syndrome remains unclear, but most authors suggest a viral etiology. Recognition of this entity and an ability to distinguish it from other common pediatric dermatoses is required to provide reassurance to parents and avoid unnecessary diagnostic procedures and treatments.

The Diagnosis: Asymmetric Periflexural Exanthem of Childhood (Unilateral Laterothoracic Exanthem)

Asymmetric periflexural exanthem of childhood (APEC), also known as unilateral laterothoracic exanthem, is a self-limited eruptive dermatosis that occurs most frequently in infants and young children. The term unilateral laterothoracic exanthem was first coined by Bodemer and de Prost1 in 1992 due to its characteristic distribution. The eruption occurs in children aged 4 months to 10 years, with most cases presenting between 2 and 3 years of age.2 Isolated cases also have been reported in adults.3 It affects girls more often than boys (2:1), and the majority of reported cases have occurred in white individuals. The disease is seen throughout Europe and North America, and seasonal variation has been noted with most cases occurring in late winter and early spring.4,5

|

Clinically, APEC is characterized by its asymmetric localization and unilateral onset. In the majority of patients, the eruption presents as discrete erythematous papules that coalesce to form morbilliform plaques that may have reticular or annular configuration (Figure).4 The exanthem begins unilaterally near a flexural area, most commonly the axilla (75% of cases), and spreads centrifugally to the adjacent trunk and proximal extremity. There is no right or left dominance.4,6 There is eventual involvement of the contralateral side in 70% of cases, but a unilateral predominance is maintained throughout the disease course.4 Rarely, the eruption may involve the face, genitals, and palmoplantar surfaces. As in our case, up to three-quarters of affected children report symptoms of an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal prodrome, including mild fever, diarrhea, and rhinitis.4 Accompanying regional lymphadenopathy has been reported in the majority of cases, and mild to moderate pruritus is not uncommon. The syndrome is self-limited, with spontaneous resolution commonly occurring 3 to 6 weeks after onset. Although no treatment is required, systemic antihistamines and topical steroids have been used to alleviate pruritus in symptomatic patients. Our patient was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% twice daily as well as oral diphenhydramine 25 mg every 6 hours as needed for associated pruritus. The eruption spontaneously resolved over the following 4 weeks.

Although the cause of APEC remains unknown, an infectious etiology has been presumed. The seasonal pattern, lack of efficacy of broad-spectrum antibiotics, frequently reported prodromal symptoms, and reports of familial cases suggest a viral etiology.1 Additionally, the predilection to affect infants and young children as well as lack of recurrence in the same patient suggests that immunity may develop. Although no etiologic agent has been consistently detected, several reports have suggested a possible relationship to parvovirus B19.7,8 Parainfluenzavirus 2, parainfluenzavirus 3, and adenovirus also have been isolated but may represent incidental viral infection.2 An inoculation dermatosis from an arthropod bite also has been suggested, but this claim has not been substantiated.1