User login

Man Seeks Treatment for Periodic “Eruptions”

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

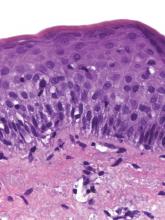

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

The correct answer is benign familial pemphigus (choice “b”). Also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, this is an unusual autosomally inherited blistering disease.

Benign familial pemphigus (BFP) is often mistaken for bacterial infection, such as pyoderma (choice “a”) or impetigo (choice “c”). Although it can become secondarily infected, its origins are entirely different.

Contact dermatitis (choice “d”) in its more severe forms can present in a similar manner. However, it would have shown entirely different changes (acute inflammation and spongiosis) on biopsy.

See next page for the discussion...

DISCUSSION

In 1939, two dermatologist-brothers in Georgia saw a patient with this previously unreported condition. They uncovered the family history and worked out the histologic basis, which they then described in the literature. They named the condition benign familial pemphigus, but it is now more commonly known as Hailey-Hailey disease in their honor.

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a serious blistering disease, was more common and far more feared at the time of the Hailey brothers’ discovery. Nearly 100% of PV patients died from the condition in that pre-steroid, pre-antibiotic era (most from secondary bacterial infection).

Fortunately, BFP is more benign, though it shares some features with PV. Both are said to be Nikolsky-positive, meaning the initial blisters can be extended with digital pressure. But BFP, unlike PV, does not involve deposition of immunoglobulins (IgA in the case of PV), nor is it accompanied by circulating auto-antibodies. BFP patients typically have no systemic symptoms, whereas in those with PV, the oral mucosae are often affected.

Herpes simplex virus, which was the primary care provider’s initial suspected diagnosis, can cause somewhat similar outbreaks, even in this area. However, it was effectively ruled out by the lack of response to treatment and by the biopsy results.

Although BFP is an inherited condition, it demonstrates variable penetrance, as in our case. It is rare enough that diagnosis is almost invariably delayed while other diagnoses are considered and treated. The actual “lesion” of BFP is still debated, but appears to involve the quality and quantity of desmosomes (microscopic structures that act as connecting fibers between layers of tissue) breaking down, often because of heat and friction, eventuating in blistering. This theory is bolstered by considerable research and by the fact that most cases present in intertriginous areas, such as the neck, axillae, and groin. Appearing episodically, it typically begins in the third to fourth decade of life, tending to diminish with age.

Biopsy is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of BFP, with the sample best taken from perilesional skin to avoid separation of friable sample fragments. Additional specimens can be taken for special handling (Michel’s media) to detect immunoglobulins that might be seen in other blistering diseases.

See next page for treatment...

TREATMENT

BFP can be treated empirically with application of a soothing solution of aluminum acetate, or more specifically with topical corticosteroids (class III to IV) and topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin 2% solution), plus/minus oral minocycline, which has potent anti-inflammatory as well as antimicrobial effects.

Difficult cases should be referred to dermatology, which has a number of treatments at its disposal. This includes diaminodiphenyl sulfone (dapsone), systemic glucocorticoids, methotrexate, systemic retinoids, and even local injection of botulinum toxin to decrease local hidrosis.

This patient is responding well to a regimen of oral minocycline 100 mg bid, topical clindamycin 2% bid application, and topical tacrolimus.

For three months, a 38-year-old man has been trying to resolve an “eruption” on his neck. The rash burns and itches, though only mildly, and produces clear fluid. His primary care provider initially prescribed acyclovir, then valacyclovir; neither helped. Subsequent courses of oral antibiotics (cephalexin 500 mg qid for three weeks, then ciprofloxacin 500 mg bid for two weeks) also had no beneficial effect. There is no family history of similar outbreaks. The patient, however, has had several of these eruptions—on the face as well as the neck—since his 20s. They typically last two to four weeks, then disappear completely for months or years. The eruptions tend to occur in the summer. He denies any history of cold sores and does not recall any premonitory symptoms prior to this eruption. He further denies any history of atopy or immunosuppression. His health is otherwise excellent, and he is taking no prescription medications. The denuded area measures about 8 x 4 cm, from his nuchal scalp down to the C6 area of the posterior neck. Discrete ruptured vesicles are seen on the periphery of the site. A layer of peeling skin, resembling wet toilet tissue, covers the partially denuded central portion, at the base of which is distinctly erythematous underlying raw tissue. There is no erythema surrounding the lesion, and no nodes are palpable in the area. A 4-mm punch biopsy is performed, with a sample taken from the periphery of the lesion and submitted for routine handling. It shows a hyperplastic epithelium, as well as intradermal and suprabasilar acantholysis extending focally into the spinous layer.

Atrophic Erythematous Facial Plaques

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

The Diagnosis: Atrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is divided into acute, subacute, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE). There are more than 20 subtypes of CCLE mentioned in the literature including atrophic lupus erythematosus (ALE).1 The most typical presentation is CCLE with discoid lesions. Most commonly, discoid CCLE is an entirely cutaneous process without systemic involvement.Discoid lesions appear as scaly red macules or papules primarily on the face and scalp.2 They may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular hyperpigmented borders and develop a central hypopigmented depression with atrophy and scarring.2,3 Discoid CCLE has a female predominance and commonly occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. Triggers of discoid lesions include UV exposure, trauma, and infection.2

Our case of multiple atrophic plaques of the face, scalp, trunk, and upper extremities demonstrated a diagnostic challenge. Our patient presented with atrophic facial plaques, which are not typical of discoid lesions of CCLE. Our patient’s findings appeared clinically similar to acne scarring or atrophoderma. Histology showed common features of CCLE, including basal liquefactive degeneration, thickening of the basement membrane zone, increased melanin, and a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (Figure).2,3 There was no evidence of hyperkeratosis, which often is seen in discoid lesions of CCLE.

Clinicopathologically, our case was consistent with ALE. A review of the literature revealed similar cases documented by Christianson and Mitchell4 in 1969; they described annular atrophic plaques of the skin of unknown diagnostic classification. Chorzelski et al5 reiterated the difficulty of defining diagnostically similar atrophic plaques of the face showing histopathologic features consistent with lupus and suggested these cases may represent an uncharacteristic presentation of discoid lupus erythematosus. Our patient demonstrated this rare subtype of discoid lupus erythematosus, known as ALE. There are few reports in the literature of ALE; thus we have managed our patient similar to other CCLE patients. Management of CCLE patients includes strict sun protection. Treatment options include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antimalarial agents, and thalidomide.2 Our patient started using tacrolimus ointment 0.1% daily and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily. She also was practicing strict photoprotection. The patient was lost to follow-up. Topical steroids are not an option in ALE. It is important for dermatologists to recognize this rare variant of CCLE to prevent disfigurement.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

1. Pramatarov KD. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus—clinical spectrum. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:113-120.

2. Rothfield N, Sontheimer RD, Bernstein M. Lupus erythematosus: systemic and cutaneous manifestations. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:348-362.

3. Al-Refu K, Goodfield M. Scar classification in cutaneous lupus erythematosus: morphological description [published online ahead of print July 14, 2009]. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1052-1058.

4. Christianson HB, Mitchell WT. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a clinical and histologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:703-716.

5. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. a variety of atrophic discoid lupus erythematosus? Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

A 26-year-old woman presented with a 2-year history of facial lesions that had gradually increased in size and number. Initially they were tender and pruritic but eventually became asymptomatic. She denied aggravation with sun exposure and did not use regular sun protection. Multiple pulsed dye laser treatments to the lesions had not resulted in appreciable improvement. Review of systems revealed occasional blurred vision and joint pain in her wrist and fingers of her right hand. Physical examination revealed a healthy-appearing woman. On the forehead and bilateral cheeks there were multiple atrophic, erythematous, sunken plaques with discrete borders. Each plaque measured more than 5 mm. Similar plaques were scattered across the frontal scalp, trunk, and upper extremities, though fewer in number and less atrophic with mild hyperpigmentation. There was diffuse hair thinning of the scalp. Laboratory test results included a normal complete metabolic panel, antinuclear antibody profile, and complete blood cell count. Histopathology revealed a superficial and mid perivascular and perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and melanophages. Vacuolar changes in the dermoepidermal junction were present. There were few dyskeratotic keratinocytes and mucin deposition present in the dermis. Direct immunofluorescence was not performed.

Is Spreading Pain Due to Injury?

Answer

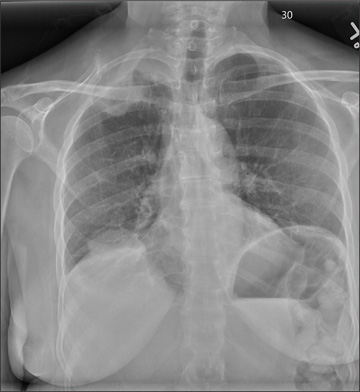

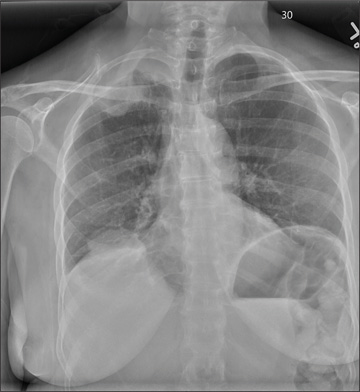

The radiograph shows a right apical mass. This clinical and radiographic presentation is strongly suggestive of a Pancoast tumor. Such lung masses (typically non–small cell carcinomas) can cause brachial plexus compression when they progress, which results in thoracic outlet obstruction and symptoms similar to those seen in this patient.

The patient was admitted by a hospitalist service, and further imaging did confirm the presence of a lung mass, as well as extension to the chest wall and cervicothoracic portion of the spinal canal. CT-guided biopsy of the mass is pending.

Answer

The radiograph shows a right apical mass. This clinical and radiographic presentation is strongly suggestive of a Pancoast tumor. Such lung masses (typically non–small cell carcinomas) can cause brachial plexus compression when they progress, which results in thoracic outlet obstruction and symptoms similar to those seen in this patient.

The patient was admitted by a hospitalist service, and further imaging did confirm the presence of a lung mass, as well as extension to the chest wall and cervicothoracic portion of the spinal canal. CT-guided biopsy of the mass is pending.

Answer

The radiograph shows a right apical mass. This clinical and radiographic presentation is strongly suggestive of a Pancoast tumor. Such lung masses (typically non–small cell carcinomas) can cause brachial plexus compression when they progress, which results in thoracic outlet obstruction and symptoms similar to those seen in this patient.

The patient was admitted by a hospitalist service, and further imaging did confirm the presence of a lung mass, as well as extension to the chest wall and cervicothoracic portion of the spinal canal. CT-guided biopsy of the mass is pending.

A 53-year-old woman presents with complaints of right-side chest wall, neck, and shoulder pain. Her symptoms started two months ago, when she says she injured herself while doing yard work. She initially self-treated but subsequently went to various emergency departments and walk-in clinics on several occasions; no definitive diagnosis was established. Recently, she has noticed increasing weakness in her right arm and hand as well. Medical history is significant for hypertension. Family history is remarkable for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (mother). Social history reveals that the patient is a smoker, with a pack-a-day habit for at least 40 years. On physical exam, you note normal vital signs. The patient has good range of motion in her extremities; however, the strength in her right upper extremity is significantly diminished. Her deltoid, biceps, triceps, and hand grip are all about 2/5. She also notes a paresthesia along her right anterior chest wall, although sensation is intact. Chest radiograph is ordered (shown). What is your impression?

Former Farmer Is Short of Breath

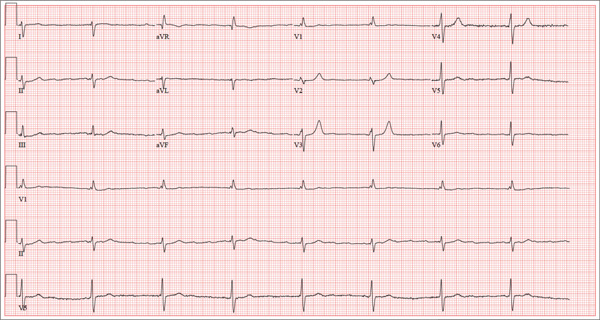

ANSWER

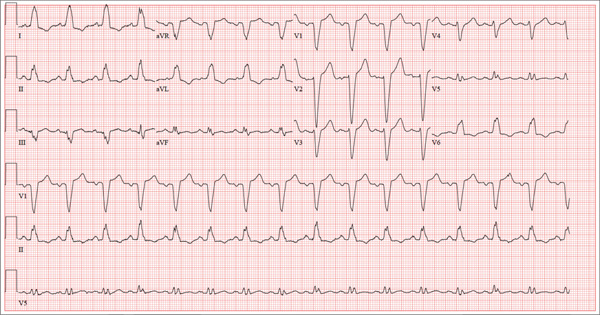

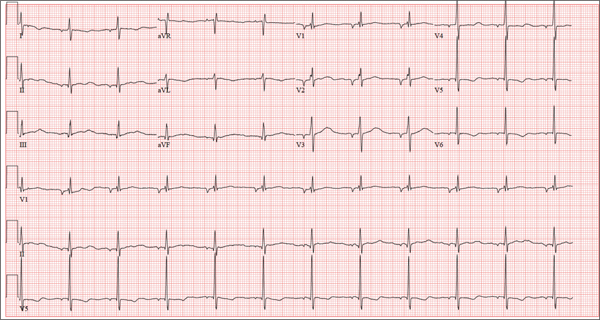

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm with left atrial enlargement and a left bundle branch block (LBBB). Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P wave associated with each QRS complex with a consistent PR interval.

Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a P-wave duration ≥ 120 ms in lead II, a notched P wave in the limb leads with a peak duration ≥ 4 ms, and a terminal P-wave negativity in lead V1 with a duration ≥ 4 ms and a depth ≥ 1 mm.

An LBBB is illustrated by the QRS duration ≥ 120 ms, a dominant S wave in lead V1, broad monophasic R waves in the lateral leads (including I, aVL, V5, and V6), and R-wave peak times of > 60 ms in leads V5 and V6.

Further work-up revealed elevated left end-diastolic filling pressures, volume overload, and pulmonary edema consistent with diastolic heart failure. Given the unclear etiology of the LBBB, cardiac catheterization was performed. It revealed no significant coronary artery disease.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm with left atrial enlargement and a left bundle branch block (LBBB). Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P wave associated with each QRS complex with a consistent PR interval.

Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a P-wave duration ≥ 120 ms in lead II, a notched P wave in the limb leads with a peak duration ≥ 4 ms, and a terminal P-wave negativity in lead V1 with a duration ≥ 4 ms and a depth ≥ 1 mm.

An LBBB is illustrated by the QRS duration ≥ 120 ms, a dominant S wave in lead V1, broad monophasic R waves in the lateral leads (including I, aVL, V5, and V6), and R-wave peak times of > 60 ms in leads V5 and V6.

Further work-up revealed elevated left end-diastolic filling pressures, volume overload, and pulmonary edema consistent with diastolic heart failure. Given the unclear etiology of the LBBB, cardiac catheterization was performed. It revealed no significant coronary artery disease.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm with left atrial enlargement and a left bundle branch block (LBBB). Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P wave associated with each QRS complex with a consistent PR interval.

Left atrial enlargement is evidenced by a P-wave duration ≥ 120 ms in lead II, a notched P wave in the limb leads with a peak duration ≥ 4 ms, and a terminal P-wave negativity in lead V1 with a duration ≥ 4 ms and a depth ≥ 1 mm.

An LBBB is illustrated by the QRS duration ≥ 120 ms, a dominant S wave in lead V1, broad monophasic R waves in the lateral leads (including I, aVL, V5, and V6), and R-wave peak times of > 60 ms in leads V5 and V6.

Further work-up revealed elevated left end-diastolic filling pressures, volume overload, and pulmonary edema consistent with diastolic heart failure. Given the unclear etiology of the LBBB, cardiac catheterization was performed. It revealed no significant coronary artery disease.

A 67-year-old man has a history of chronic dyspnea. He is a retired farmer who says he “never had time” to seek medical help for anything other than cuts or broken bones. In the past two months, he’s noticed that his dyspnea has progressively worsened. When questioned, he admits that his legs began swelling around that time as well. Two days ago, he awoke from sleep unable to catch his breath. This morning, while walking to his mailbox, he became profoundly short of breath. He sat down by the side of the road and called 911. When the ambulance arrived, he felt much better but agreed to be taken to the emergency department, since his wife is away and he’s home alone. When questioned by the paramedics, he denied having chest pain, palpitations, productive or nonproductive cough, polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, or vomiting. Medical history is positive for hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and hypertension. He has had several fractures in his right ankle and left femur, which are well healed. Surgical history is remarkable for a cholecystectomy and multiple laceration repairs on his arms and hands (also well healed). His current medications include one aspirin per day and “a handful” of calcium carbonate tablets. Although he was prescribed “several heart pills” for hypertension, he hasn’t taken them or refilled the prescriptions for at least five years. He is allergic to penicillin and sulfa. He denies recreational or homeopathic drug use. He has never smoked, and he drinks one or two shots of bourbon on weekends. Family history includes a father who died in a farming accident and a mother who died of cervical cancer at age 85. He has seven siblings, all of whom are alive and well. The review of systems is remarkable only for GERD. Physical exam reveals a well-developed, obese male with a height of 6 ft 4 in and a weight of 278 lb. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 184/98 mm Hg; pulse, 90 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min-1. He is afebrile. The HEENT exam is remarkable for atrophic glossitis. The neck shows no evidence of thyromegaly, and there are no carotid bruits or jugular venous distention. The chest is remarkable for diffuse wheezing and crackles in all lung bases. The cardiac exam reveals a regular rate of 90 beats/min, with no evidence of murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The abdomen is obese. There is no evidence of ascites or masses. Evidence of 2+ pitting edema to the midcalf is present bilaterally. The neurologic exam is grossly intact, and the psychiatric exam reveals the patient to be alert and oriented, with a bright affect. The working diagnosis in the emergency department is acute or chronic heart failure. A chest x-ray reveals moderate-to-severe pulmonary edema, cardiomegaly, and small bilateral effusions. Pertinent laboratory data include a serum glucose of 200 mg/dL and a B-type natriuretic peptide level of 590 pg/mL. All other lab values are within normal limits. An ECG reveals the following: a ventricular rate of 93 beats/min; PR interval, 168 ms; QRS duration, 156 ms; QT/QTc interval, 430/534 ms; P axis, 52°; R axis, 9°; and T axis, 171°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Hair Loss at a Very Young Age

ANSWER

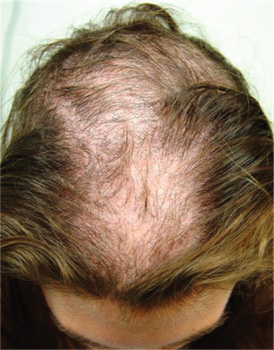

The correct answer is trichotillomania (choice “c”). See Discussion for more information.

Alopecia mucinosa (choice “a”) is a rare cause of focal hair loss that can occur in children. However, it usually presents with papules or plaques, unlike the smooth skin surface seen here.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”), common in children, typically entails complete hair loss in a given area—or, as hair regrows, with hairs of equal length. The uneven hairs seen in trichotillomania help a great deal in distinguishing it from alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia (choice “d”) is focal hair loss caused by chronic tension related to hairstyling. Most common in African-American women, and typically affecting the frontal periphery of the scalp, it is an unlikely explanation for hair loss in a 10-year-old boy.

DISCUSSION

Trichotillomania (TT) means, literally, “hair-pulling madness.” But in reality, there’s little actual plucking of hairs in this common condition. Instead, patients habitually manipulate hair by twirling and tugging, which weakens the shafts and follicles and renders them more susceptible to everyday wear and tear. In some cases, individual hairs speed through their growth phases and others break off in mid-shaft. All of this contributes to the classic “uneven” look of TT.

Patients with TT tend to be in the 4-to-17 age range, and most have issues with unresolved anxiety that manifest in part with manipulation of the hair. Officially considered an impulse control disorder, TT in most cases belongs to the psychiatrist’s domain.

In this case, it was enormously helpful to have corroboration from the patient and his mother regarding his role in creating and perpetuating the problem. Had that not been the case—or in the event of other doubts as to the correct diagnosis—biopsy could have been performed to rule out most of the other items in the differential, particularly alopecia areata.

Interestingly enough, studies have shown that the more sharply defined the area of hair loss, the more likely the patient is to admit his/her role in its creation. However, as is often the case with scientific research, contradictory findings have also been made.

TREATMENT

Treatment of TT is problematic, since no medications have proven to be completely helpful. Psychiatrists use a combination of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavior modifications that are designed to overcome the habitual component of the problem. Most cases of TT resolve on their own, but in severe cases that persist for years, permanent hair loss can result.

In this case, there was enough insight and motivation on the part of the patient and his family to stop the offending behavior and allow the hair to regrow.

ANSWER

The correct answer is trichotillomania (choice “c”). See Discussion for more information.

Alopecia mucinosa (choice “a”) is a rare cause of focal hair loss that can occur in children. However, it usually presents with papules or plaques, unlike the smooth skin surface seen here.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”), common in children, typically entails complete hair loss in a given area—or, as hair regrows, with hairs of equal length. The uneven hairs seen in trichotillomania help a great deal in distinguishing it from alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia (choice “d”) is focal hair loss caused by chronic tension related to hairstyling. Most common in African-American women, and typically affecting the frontal periphery of the scalp, it is an unlikely explanation for hair loss in a 10-year-old boy.

DISCUSSION

Trichotillomania (TT) means, literally, “hair-pulling madness.” But in reality, there’s little actual plucking of hairs in this common condition. Instead, patients habitually manipulate hair by twirling and tugging, which weakens the shafts and follicles and renders them more susceptible to everyday wear and tear. In some cases, individual hairs speed through their growth phases and others break off in mid-shaft. All of this contributes to the classic “uneven” look of TT.

Patients with TT tend to be in the 4-to-17 age range, and most have issues with unresolved anxiety that manifest in part with manipulation of the hair. Officially considered an impulse control disorder, TT in most cases belongs to the psychiatrist’s domain.

In this case, it was enormously helpful to have corroboration from the patient and his mother regarding his role in creating and perpetuating the problem. Had that not been the case—or in the event of other doubts as to the correct diagnosis—biopsy could have been performed to rule out most of the other items in the differential, particularly alopecia areata.

Interestingly enough, studies have shown that the more sharply defined the area of hair loss, the more likely the patient is to admit his/her role in its creation. However, as is often the case with scientific research, contradictory findings have also been made.

TREATMENT

Treatment of TT is problematic, since no medications have proven to be completely helpful. Psychiatrists use a combination of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavior modifications that are designed to overcome the habitual component of the problem. Most cases of TT resolve on their own, but in severe cases that persist for years, permanent hair loss can result.

In this case, there was enough insight and motivation on the part of the patient and his family to stop the offending behavior and allow the hair to regrow.

ANSWER

The correct answer is trichotillomania (choice “c”). See Discussion for more information.

Alopecia mucinosa (choice “a”) is a rare cause of focal hair loss that can occur in children. However, it usually presents with papules or plaques, unlike the smooth skin surface seen here.

Alopecia areata (choice “b”), common in children, typically entails complete hair loss in a given area—or, as hair regrows, with hairs of equal length. The uneven hairs seen in trichotillomania help a great deal in distinguishing it from alopecia areata.

Traction alopecia (choice “d”) is focal hair loss caused by chronic tension related to hairstyling. Most common in African-American women, and typically affecting the frontal periphery of the scalp, it is an unlikely explanation for hair loss in a 10-year-old boy.

DISCUSSION

Trichotillomania (TT) means, literally, “hair-pulling madness.” But in reality, there’s little actual plucking of hairs in this common condition. Instead, patients habitually manipulate hair by twirling and tugging, which weakens the shafts and follicles and renders them more susceptible to everyday wear and tear. In some cases, individual hairs speed through their growth phases and others break off in mid-shaft. All of this contributes to the classic “uneven” look of TT.

Patients with TT tend to be in the 4-to-17 age range, and most have issues with unresolved anxiety that manifest in part with manipulation of the hair. Officially considered an impulse control disorder, TT in most cases belongs to the psychiatrist’s domain.

In this case, it was enormously helpful to have corroboration from the patient and his mother regarding his role in creating and perpetuating the problem. Had that not been the case—or in the event of other doubts as to the correct diagnosis—biopsy could have been performed to rule out most of the other items in the differential, particularly alopecia areata.

Interestingly enough, studies have shown that the more sharply defined the area of hair loss, the more likely the patient is to admit his/her role in its creation. However, as is often the case with scientific research, contradictory findings have also been made.

TREATMENT

Treatment of TT is problematic, since no medications have proven to be completely helpful. Psychiatrists use a combination of medication, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavior modifications that are designed to overcome the habitual component of the problem. Most cases of TT resolve on their own, but in severe cases that persist for years, permanent hair loss can result.

In this case, there was enough insight and motivation on the part of the patient and his family to stop the offending behavior and allow the hair to regrow.

A 10-year-old boy is referred to dermatology with a four-month history of hair loss. The affected area of the vertex is now large enough to alarm his mother, who accompanies him to his appointment. The child’s primary care provider had diagnosed alopecia areata and prescribed triamcinolone 0.1% solution. But after a month of twice-daily application, even more hair has been lost. There is no family history of alopecia areata or other autoimmune disease. The child is otherwise healthy, although he is being treated by a psychiatrist for attention deficit disorder and chronic anxiety (with two medications whose names are unknown). The patient denies any symptoms associated with his hair loss, and his mother denies any skin changes in the affected area. However, she emphasizes that she has seen her son manipulating the area with his hand on several occasions, despite her attempts to make him stop. When pressed, the patient finally admits that throughout the day he twirls and tugs on his hair—although he denies actually pulling out any. On inspection, an 11 x 8–cm oval area of distinct and sharply demarcated hair loss is noted in the vertex scalp. Hairs of different lengths are noted in the central portion of the site; some have obviously been broken off, while others are longer, with thin, tapering ends. There is no disruption (eg, scaling, redness, edema) in the surface of the scalp, but the whole area is darker (brown) than the surrounding, uninvolved scalp. No other areas of hair loss are noted in the scalp or face. No nodes are palpable in the neck.

Growing Lesion Impedes Finger Flexion

ANSWER

The correct answer is implantation cyst (choice “b”). This type of cyst is typically caused by trauma (eg, a puncture wound), and its contents are in stark contrast to those of ganglion cysts (choice “a”), which are thick and clear.

Warts (choice “c”) are essentially an epidermal process, not subcutaneous. They almost always disrupt normal skin lines, which often curve around the wart—a finding that was missing in this case.

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas (choice “d”) are benign solid tumors frequently seen on fingers. However, they are more epidermal than intradermal and demonstrate a diagnostic feature called an epidermal collarette (missing in this case).

DISCUSSION

Sometimes called implantation dermoid cysts, these sacs have a well-defined white cyst wall and cheesy, often odoriferous contents. Although common on hands and fingers, they can occur in almost any location and as a result of many types of trauma.

This includes surgical trauma, which effectively implants surface adnexal tissue (eg, the sebaceous apparatus) where it can continue to produce and accumulate its cheesy contents over time. Patients often forget the trauma that caused the cyst, but it is still worth inquiring into.

Merely emptying the sac can confirm the diagnosis; however, this almost always results in recurrence. Fortunately, implantation cysts are usually easily removed with minimal risk to hand function.

As with almost any tissue removed from the body, the specimen needs to be sent for pathologic examination. In addition to the differential items already noted, a number of rare or unusual conditions can present in a similar fashion, including eccrine carcinoma and a variety of sarcomas.

This patient recovered from his surgery without complication. Pathologic examination confirmed the benign nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is implantation cyst (choice “b”). This type of cyst is typically caused by trauma (eg, a puncture wound), and its contents are in stark contrast to those of ganglion cysts (choice “a”), which are thick and clear.

Warts (choice “c”) are essentially an epidermal process, not subcutaneous. They almost always disrupt normal skin lines, which often curve around the wart—a finding that was missing in this case.

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas (choice “d”) are benign solid tumors frequently seen on fingers. However, they are more epidermal than intradermal and demonstrate a diagnostic feature called an epidermal collarette (missing in this case).

DISCUSSION

Sometimes called implantation dermoid cysts, these sacs have a well-defined white cyst wall and cheesy, often odoriferous contents. Although common on hands and fingers, they can occur in almost any location and as a result of many types of trauma.

This includes surgical trauma, which effectively implants surface adnexal tissue (eg, the sebaceous apparatus) where it can continue to produce and accumulate its cheesy contents over time. Patients often forget the trauma that caused the cyst, but it is still worth inquiring into.

Merely emptying the sac can confirm the diagnosis; however, this almost always results in recurrence. Fortunately, implantation cysts are usually easily removed with minimal risk to hand function.

As with almost any tissue removed from the body, the specimen needs to be sent for pathologic examination. In addition to the differential items already noted, a number of rare or unusual conditions can present in a similar fashion, including eccrine carcinoma and a variety of sarcomas.

This patient recovered from his surgery without complication. Pathologic examination confirmed the benign nature of the lesion.

ANSWER

The correct answer is implantation cyst (choice “b”). This type of cyst is typically caused by trauma (eg, a puncture wound), and its contents are in stark contrast to those of ganglion cysts (choice “a”), which are thick and clear.

Warts (choice “c”) are essentially an epidermal process, not subcutaneous. They almost always disrupt normal skin lines, which often curve around the wart—a finding that was missing in this case.

Acquired digital fibrokeratomas (choice “d”) are benign solid tumors frequently seen on fingers. However, they are more epidermal than intradermal and demonstrate a diagnostic feature called an epidermal collarette (missing in this case).

DISCUSSION

Sometimes called implantation dermoid cysts, these sacs have a well-defined white cyst wall and cheesy, often odoriferous contents. Although common on hands and fingers, they can occur in almost any location and as a result of many types of trauma.

This includes surgical trauma, which effectively implants surface adnexal tissue (eg, the sebaceous apparatus) where it can continue to produce and accumulate its cheesy contents over time. Patients often forget the trauma that caused the cyst, but it is still worth inquiring into.

Merely emptying the sac can confirm the diagnosis; however, this almost always results in recurrence. Fortunately, implantation cysts are usually easily removed with minimal risk to hand function.

As with almost any tissue removed from the body, the specimen needs to be sent for pathologic examination. In addition to the differential items already noted, a number of rare or unusual conditions can present in a similar fashion, including eccrine carcinoma and a variety of sarcomas.

This patient recovered from his surgery without complication. Pathologic examination confirmed the benign nature of the lesion.

For several years, a 45-year-old man has had an asymptomatic lesion on the volar aspect of his fourth finger. The lesion is growing and increasingly “in the way.” That, coupled with the patient’s concern about cancer or other serious disease, leads him to request referral to dermatology. There is no history of similar lesions anywhere on his body. Additional questioning reveals that several months prior to the lesion’s manifestation, the patient sustained a puncture wound to the same finger. Initially, the affected area was only a millimeter or two in size. X-rays ordered by his primary care provider did not indicate any bony abnormality, nor did they shed any light on the lesion itself. An impressive 2.6 cm in diameter, the lesion is prominent in vertical elevation as well. Motor and sensory function are found to be intact, although the bulk of the lesion prohibits full flexion of the finger. The lesion is opaque to attempted transillumination. No surface changes are apparent in the overlying skin. Skin lines are intact and parallel. The lesion is quite firm but compressible. The decision is made to excise the lesion, employing a digital block and tourniquet. A football-shaped ellipse of skin with 50° angles on the ends is removed from the surface, revealing a glistening white, smooth mass that comes out intact, with very little blunt dissection. Motor function is again assessed and found to be intact. The large angles in the ends of the ellipse allow the wound edges to be pulled together with interrupted vertical mattress sutures and no leftover redundant skin. The lesion is submitted intact for pathologic examination.

Neck Pain With No Palpable Tenderness

ANSWER

The image shows an acute fracture at the base of the odontoid with evidence of posterior displacement of the fracture fragment. Such fractures are typically unstable.

In addition, there is evidence of a fracture and subluxation at the C4/C5 level. However, given the degree of sclerosis and chronic changes present, this finding is likely an old one.

The patient was maintained in a collar on bedrest. Subsequently, he underwent odontoid pinning to stabilize the fractures.

ANSWER

The image shows an acute fracture at the base of the odontoid with evidence of posterior displacement of the fracture fragment. Such fractures are typically unstable.

In addition, there is evidence of a fracture and subluxation at the C4/C5 level. However, given the degree of sclerosis and chronic changes present, this finding is likely an old one.

The patient was maintained in a collar on bedrest. Subsequently, he underwent odontoid pinning to stabilize the fractures.

ANSWER

The image shows an acute fracture at the base of the odontoid with evidence of posterior displacement of the fracture fragment. Such fractures are typically unstable.

In addition, there is evidence of a fracture and subluxation at the C4/C5 level. However, given the degree of sclerosis and chronic changes present, this finding is likely an old one.

The patient was maintained in a collar on bedrest. Subsequently, he underwent odontoid pinning to stabilize the fractures.

A 65-year-old man presents with neck pain following a fall. Earlier this evening, he says, he fell off his porch (approximately four feet in height) and hit the top/front of his head on the ground. He denies any loss of consciousness, adding that he only came in for evaluation at the urging of his family. The patient denies any extremity weakness or paresthesias. He also denies any significant medical history, although his sister, who has accompanied him, states that he drinks alcohol “regularly and heavily.” Physical examination reveals a man who appears much older than his stated age and is uncomfortable, but not in obvious distress. His vital signs are normal. He is currently wearing a hard cervical collar. There is no palpable tenderness posteriorly along his cervical spine. He is able to move all of his extremities well. His strength is good, and his sensation is intact. A lateral radiograph of the patient’s cervical spine is shown. What is your impression?

Is Lingering “Flu” Responsible for Lethargy?

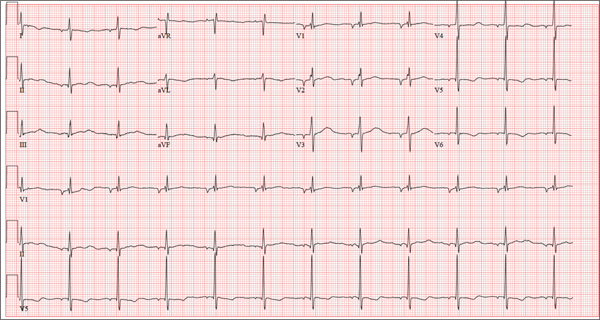

ANSWER

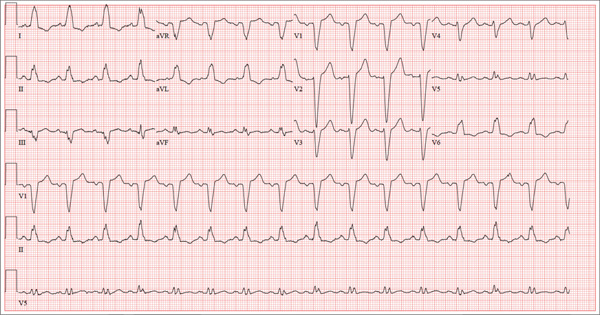

This ECG shows a junctional rhythm with a rate of 47 beats/min and an incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB). The QRS complexes are narrow, indicating conduction originating at or above the atrioventricular (AV) node.

With the absence of a P wave for every QRS complex, the origin of each beat occurs at the level of the AV node, with depolarization of the ventricles via the normal conduction pathway. Intrinsic automaticity of the AV node results in a rate of 40 to 60 beats/min. There may be retrograde conduction from the AV node into the atria; however, it is not apparent in this ECG.

An incomplete RBBB is evidenced by a QRS complex with a duration > 100 ms and ≤ 120 ms with a terminal R wave (eg, rsR’) in lead V1 and a slurred S wave in leads I and V6 (more common with complete RBBB).

The presence of new-onset junctional rhythm with an incomplete RBBB is suspicious for conduction system disease. Given her symptomatic bradycardia, the patient underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. She has since returned to her normal activities.

Of note: Careful examination of the baseline in this tracing raises suspicion for atrial fibrillation (AF). However, according to her primary care provider, this patient had had no previous episodes of AF. Intracardiac electrograms taken during her pacemaker implantation ruled out this diagnosis.

ANSWER

This ECG shows a junctional rhythm with a rate of 47 beats/min and an incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB). The QRS complexes are narrow, indicating conduction originating at or above the atrioventricular (AV) node.

With the absence of a P wave for every QRS complex, the origin of each beat occurs at the level of the AV node, with depolarization of the ventricles via the normal conduction pathway. Intrinsic automaticity of the AV node results in a rate of 40 to 60 beats/min. There may be retrograde conduction from the AV node into the atria; however, it is not apparent in this ECG.

An incomplete RBBB is evidenced by a QRS complex with a duration > 100 ms and ≤ 120 ms with a terminal R wave (eg, rsR’) in lead V1 and a slurred S wave in leads I and V6 (more common with complete RBBB).

The presence of new-onset junctional rhythm with an incomplete RBBB is suspicious for conduction system disease. Given her symptomatic bradycardia, the patient underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. She has since returned to her normal activities.

Of note: Careful examination of the baseline in this tracing raises suspicion for atrial fibrillation (AF). However, according to her primary care provider, this patient had had no previous episodes of AF. Intracardiac electrograms taken during her pacemaker implantation ruled out this diagnosis.

ANSWER

This ECG shows a junctional rhythm with a rate of 47 beats/min and an incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB). The QRS complexes are narrow, indicating conduction originating at or above the atrioventricular (AV) node.

With the absence of a P wave for every QRS complex, the origin of each beat occurs at the level of the AV node, with depolarization of the ventricles via the normal conduction pathway. Intrinsic automaticity of the AV node results in a rate of 40 to 60 beats/min. There may be retrograde conduction from the AV node into the atria; however, it is not apparent in this ECG.

An incomplete RBBB is evidenced by a QRS complex with a duration > 100 ms and ≤ 120 ms with a terminal R wave (eg, rsR’) in lead V1 and a slurred S wave in leads I and V6 (more common with complete RBBB).

The presence of new-onset junctional rhythm with an incomplete RBBB is suspicious for conduction system disease. Given her symptomatic bradycardia, the patient underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. She has since returned to her normal activities.

Of note: Careful examination of the baseline in this tracing raises suspicion for atrial fibrillation (AF). However, according to her primary care provider, this patient had had no previous episodes of AF. Intracardiac electrograms taken during her pacemaker implantation ruled out this diagnosis.

Accompanied by her daughter, whom she is visiting from out of town, a 72-year-old woman presents with a two-week history of lethargy. She says she had “the flu” three weeks ago and just can’t seem to recover from it. According to her daughter, she doesn’t appear ill but seems to tire very easily after simple tasks such as walking from her bedroom to the kitchen. The patient denies fever, chills, orthopnea, dyspnea, and cough. There have been no episodes of near-syncope or syncope. She repeatedly states that she is “just so tired.” Prior to the onset of her flulike symptoms, she was very active in her retirement community, dancing, gardening, and going on sponsored trips to a local casino without difficulty. She says she wouldn’t even attempt those activities in her current state, as any activity immediately exhausts her. Medical history is remarkable for hypertension, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, and diabetes. Surgical history is remarkable for a cholecystectomy, abdominal hysterectomy, and removal of several lipomas from her upper extremities. Her current medications include aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, lisinopril, metformin, and levothyroxine. She is allergic to penicillin and sulfa, both of which cause hives and flushing. Social history reveals that she is a retired junior high school librarian, the mother of three living children, and a widow. She is a smoker, with a one-pack-per-day history from age 14 until her husband died four years ago. She quit at that time but has recently started again, smoking half a pack per day (but “only” when she goes to the casino). She does not use alcohol or recreational drugs. The review of systems is positive for corrective lenses and symptoms suggestive of a urinary tract infection. On physical exam, her blood pressure is 138/92 mm Hg; pulse, 50 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.4°F. Her weight is 224 lb, and her height is 62 in. She walks with the assistance of a cane and appears tired and apprehensive. Pertinent physical findings include bilateral cataracts, clear lung fields, and a soft, early systolic murmur at the left lower sternal border. She has two well-healed scars on her abdomen and multiple well-healed scars on both upper extremities. Her hands show evidence of osteoarthritis, and she has limited range of motion but no pain in her right hip. The neurologic exam is grossly intact. Laboratory tests and an ECG are performed. The ECG findings include a ventricular rate of 47 beats/min; PR interval, not measured; QRS duration, 120 ms; QT/QTc interval, 454/401 ms; P axis, not measured; R axis, 171°; and T axis, 51°. What is your interpretation of this ECG—and does it provide an explanation for the patient’s recent lethargy?

Construction Worker Falls From Scaffolding

A 45-year-old construction worker is brought to your facility for evaluation following a fall. He was at a job site, standing on scaffolding approximately 20 feet above the ground, when he accidentally fell. He does not remember for sure, but he thinks he landed on his face. He did briefly lose consciousness. He is complaining of right-side facial pain and right wrist pain. His medical history is unremarkable. The physical exam reveals stable vital signs. The patient appears somewhat uncomfortable but is in no obvious distress. There is a moderate amount of periorbital soft-tissue swelling around his right eye, with moderate associated tenderness. Pupils are equal and react well bilaterally. Examination of the right wrist shows a moderate amount of soft-tissue swelling. The patient is unable to flex or extend his wrist due to pain. Good pulses and capillary refill of the nail beds are noted. There is also moderate tenderness along the base of the first metacarpal. Radiograph of the right wrist is shown. What is your impression?

Now Insured, Patient Wants to “Get Checked Out”

ANSWER

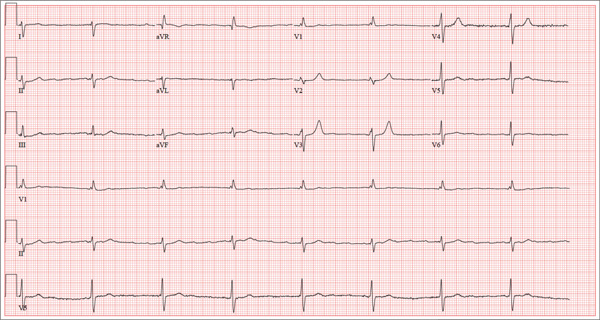

There are three findings on this ECG: unusual P waves consistent with a possible ectopic atrial rhythm, a prolonged QT interval, and T-wave abnormalities in the lateral leads.

Note that the P waves are negative in leads I and II, as well as in all chest leads. This is highly suggestive of an ectopic atrial rhythm originating low in the atria, conducting retrograde into the atria, and overriding the sinoatrial node. Limb lead reversal would result in negative P waves in lead I, but not in other leads.

A prolonged QT interval is determined by consulting any of the standard charts that correlate maximum heart rates with QT intervals and gender. In men, the QT interval is considered “prolonged” when it exceeds 440 ms, unless the heart rate is extremely slow.

Finally, T-wave inversions are present in the lateral leads (V5, V6). Although this may be an indication of lateral ischemia, there is no clinical correlation in this patient.

ANSWER

There are three findings on this ECG: unusual P waves consistent with a possible ectopic atrial rhythm, a prolonged QT interval, and T-wave abnormalities in the lateral leads.

Note that the P waves are negative in leads I and II, as well as in all chest leads. This is highly suggestive of an ectopic atrial rhythm originating low in the atria, conducting retrograde into the atria, and overriding the sinoatrial node. Limb lead reversal would result in negative P waves in lead I, but not in other leads.

A prolonged QT interval is determined by consulting any of the standard charts that correlate maximum heart rates with QT intervals and gender. In men, the QT interval is considered “prolonged” when it exceeds 440 ms, unless the heart rate is extremely slow.

Finally, T-wave inversions are present in the lateral leads (V5, V6). Although this may be an indication of lateral ischemia, there is no clinical correlation in this patient.

ANSWER

There are three findings on this ECG: unusual P waves consistent with a possible ectopic atrial rhythm, a prolonged QT interval, and T-wave abnormalities in the lateral leads.

Note that the P waves are negative in leads I and II, as well as in all chest leads. This is highly suggestive of an ectopic atrial rhythm originating low in the atria, conducting retrograde into the atria, and overriding the sinoatrial node. Limb lead reversal would result in negative P waves in lead I, but not in other leads.

A prolonged QT interval is determined by consulting any of the standard charts that correlate maximum heart rates with QT intervals and gender. In men, the QT interval is considered “prolonged” when it exceeds 440 ms, unless the heart rate is extremely slow.

Finally, T-wave inversions are present in the lateral leads (V5, V6). Although this may be an indication of lateral ischemia, there is no clinical correlation in this patient.

A 37-year-old man presents to your office to establish care. After being unemployed for two years, he recently obtained a position with a local manufacturing company and, as a result, has health benefits. He wants to “get checked out.” He has not seen a health care provider since having his tonsils removed at age 14. He says he is rarely ill, aside from an occasional cold. Besides the tonsillectomy, medical history is positive for a right clavicular fracture at age 6 and a left inguinal hernia repair at age 9. He had chickenpox and recalls that his immunizations were up to date until he graduated high school. His only medication is ibuprofen as needed for aches and pains. He has no known drug allergies. He uses two herbal supplements, fenugreek seed and horny goat weed, daily. He admits to recreational marijuana use. Family history is remarkable for coronary artery disease (father), diabetes (mother), and depression (sister). He consumes one six-pack of beer weekly and has smoked one pack of cigarettes per day for the past 23 years. He isn’t interested in quitting smoking. The patient is divorced, without children. He has been collecting unemployment since his last position was terminated due to budget constraints. A 20-point comprehensive review of systems is negative, with the exception of occasional palpitations and a productive morning smoker’s cough that quickly resolves. He states he’s “as healthy as a horse.” The physical exam reveals a thin, healthy-appearing middle-aged male. He is 72 in tall and weighs 167 lb. His blood pressure is 108/66 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min and regular; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; and temperature, 98.4°F. The head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat (HEENT) exam is remarkable for poor dentition, with multiple caries readily visible. The tonsils are absent. Coarse expiratory crackles are present in both bases and clear with vigorous coughing. The abdominal exam is positive for a well-healed scar in the left inguinal crease. The remainder of the physical exam is normal. As part of a new patient visit, a chest x-ray and ECG are obtained. The ECG shows the following: a ventricular rate of 69 beats/min; PR interval, 178 ms; QRS duration, 90ms; QT/QTc interval, 442/473 ms; P axis, 231°; R axis, 84°; and T axis, 93°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?