User login

Abuse of the Safety-Net 340B Drug Pricing Program: Why Should Physicians Care?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program began as a noble endeavor, a lifeline designed to help safety-net providers deliver affordable care to America’s most vulnerable populations. However, over the years, this well-intentioned program has strayed from its original purpose, becoming a lucrative space where profits often outweigh patients. Loopholes, lax oversight, and unchecked expansion have allowed some powerful players, such as certain disproportionate share hospitals and their “child sites” as well as for-profit pharmacies, to exploit the system. What was once a program to uplift underserved communities now risks becoming a case study in how good intentions can go astray without accountability.

What exactly is this “340B program” that has captured headlines and the interest of legislatures around the country? What ensures that pharmaceutical manufacturers continue to participate in this program? How lucrative is it? How have underserved populations benefited and how is that measured?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program was established in 1992 under the Public Health Service Act. Its primary goal is to enable covered entities (such as hospitals and clinics serving low-income and uninsured patients) to purchase outpatient drugs from pharmaceutical manufacturers at significantly reduced prices in order to support their care of the low-income and underserved populations. Drug makers are required to participate in this program as a condition of their participation in Medicaid and Medicare Part B and offer these steep discounts to covered entities if they want their medications to be available to 38% of patients nationwide.

The hospitals that make up 78% of the program’s spending are known as disproportionate share hospitals (DSHs). These hospitals must be nonprofit and have at least an 11.75% “disproportionate” share of low-income Medicare or Medicaid inpatients. The other types of non-hospital entities qualifying for 340B pricing are known as initial “federal grantees.” Some examples include federally qualified health centers (FQHC), Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grantees, and other types of specialized clinics, such as hemophilia treatment centers. It needs to be noted up front that it is not these initial non-hospital federal grantees that need more oversight or reform, since according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) 2023 report they make up only 22% of all program spending. It is the large, predominantly DSH health systems that are profiting immensely through exponential growth of their clinics and contract pharmacies. However, these health systems have not been able to show exactly who are their eligible patients and how they have been benefiting them.

When the 340B program was established to offer financial relief to hospitals and clinics taking care of the uninsured, it allowed them to save 20%-50% on drug purchases, which could be reinvested in patient care services. It was hoped that savings from the program could be used to provide free or low-cost medications, free vaccines, and other essential health services, essentially allowing safety-net providers to serve their communities despite financial constraints. The initial grantees are fulfilling that mission, but there are concerns regarding DSHs. (See the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organization’s 340B explanatory statement and policy position for more.)

Why Should Independent Practice Physicians Care About This?

Independent doctors should care about the lack of oversight in the 340B program because it affects healthcare costs, patient assistance, market competition, and access to affordable care for underserved and uninsured patients.

It also plays a strong hand in the healthcare consolidation that continues to threaten private physician practices. These acquisitions threaten the viability of independent practices in a variety of specialties across the United States, including rheumatology. HRSA allows 340B-covered entities to register their off-campus outpatient facilities, or child sites, under their 340B designation. Covered entities can acquire drugs at the 340B price, while imposing markups on the reimbursement they submit to private insurance. The additional revenue these covered entities can pocket provides them with a cash flow advantage that physician practices and outpatient clinics will never be able to actualize. This uneven playing field may make rheumatology practices more susceptible to hospital acquisitions. In fact, between 2016 and 2022, large 340B hospitals were responsible for approximately 80% of hospital acquisitions.

Perhaps the most important reason that we should all be concerned about the trajectory of this well-meaning program is that we have seen patients with hospital debt being sued by DSHs who receive 340B discounts so that they can take care of the low-income patients they are suing. We have seen Medicaid patients be turned away from a DSH clinic after being discharged from that hospital, because the hospital had reached its disproportionate share (11.75%) of inpatient Medicare and Medicaid patients. While not illegal, that type of behavior by covered entities is WRONG! Oversight and reform are needed if the 340B program is going to live up to its purpose and not be just another well-intentioned program not fulfilling its mission.

Areas of Concern

There has been controversy regarding the limited oversight of the 340B program by HRSA, leading to abuse of the program. There are deep concerns regarding a lack of transparency in how savings from the program are being used, and there are concerns about the challenges associated with accurate tracking and reporting of 340B discounts, possibly leading to the duplication of discounts for both Medicaid and 340B. For example, a “duplicate discount” occurs if a manufacturer sells medications to a DSH at the 340B price and later pays a Medicaid rebate on the same drug. The extent of duplicate discounts in the 340B program is unknown. However, an audit of 1,536 cases conducted by HRSA between 2012 and 2019 found 429 instances of noncompliance related to duplicate discounts, which is nearly 30% of cases.

DSHs and their contracted pharmacies have been accused of exploiting the program by increasing the number of contract pharmacies and expanding the number of offsite outpatient clinics to maximize profits. As of mid-2024, the number of 340B contract pharmacies, counted by Drug Channels Institute (DCI), numbered 32,883 unique locations. According to DCI, the top five pharmacies in the program happen also to be among the top pharmacy revenue generators and are “for-profit.” They are CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Express Scripts, and Optum RX. Additionally, a study in JAMA Health Forum showed that, from 2011 to 2019, contract pharmacies in areas with the lowest income decreased by 5.6% while those in the most affluent neighborhoods grew by 5%.

There also has been tremendous growth in the number of covered entities in the 340B program, which grew from just over 8,100 in 2000 to 50,000 in 2020. Before 2004, DSHs made up less than 10% of these entities, but by 2020, they accounted for over 60%. Another study shows that DSHs are expanding their offsite outpatient clinics (“child clinics”) into the affluent neighborhoods serving commercially insured patients who are not low income, to capture the high commercial reimbursements for medications they acquired at steeply discounted prices. This clearly is diverting care away from the intended beneficiaries of the 340B program.

Furthermore, DSHs have been acquiring specialty practices that prescribe some of the most expensive drugs, in order to take advantage of commercial reimbursement for medications that were acquired at the 340B discount price. Independent oncology practices have complained specifically about this happening in their area, where in some cases the DSHs have “stolen” their patients to profit off of the 340B pricing margins. This has the unintended consequence of increasing government spending, according to a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that showed price markups at 340B eligible hospitals were 6.59 times as high as those in independent physician practices after accounting for drug, patient, and geographic factors.

Legal Challenges and Legislation

On May 21, 2024, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit issued a unanimous decision in favor of drug manufacturers, finding that certain manufacturer restrictions on the use of contract pharmacies under the 340B drug pricing program are permissible. The court’s decision follows a lower court (3rd Circuit) ruling which concluded that the 340B statute does not require manufacturers to deliver 340B drugs to an “unlimited number of contract pharmacies.” We’re still awaiting a decision from the 7th Circuit Court on a similar issue. If the 7th Circuit agrees with the government, creating a split decision, there is an increase in the likelihood that the Supreme Court would take up the case.

Johnson & Johnson has also sued the federal government for blocking their proposed use of a rebate model for DSHs that purchase through 340B two of its medications, Stelara and Xarelto, whose maximum fair price was negotiated through the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. J&J states this would ensure that the claims are actually acquired and dispensed by a covered 340B entity, as well as ensuring there are no duplicate discounts as statutorily required by the IRA. When initially proposed, HRSA threatened to remove J&J’s access to Medicare and Medicaid if it pursued this change. J&J’s suit challenges that decision.

However, seven states (Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, and West Virginia) have been active on this issue, passing laws to prevent manufacturers from limiting contract pharmacies’ ability to acquire 340B-discounted drugs. The model legislation also bans restrictions on the “number, location, ownership, or type of 340B contract pharmacy.”

It should also be noted that there are states that are looking for ways to encourage certain independent private practice specialties (such as gastroenterology and rheumatology) to see Medicaid patients, as well as increase testing for sexually transmitted diseases, by offering the possibility of obtaining 340B pricing in their clinics.

Shifting our focus to Congress, six bipartisan Senators, known as the Group of 6, are working to modernize the 340B program, which hasn’t been updated since the original law in 1992. In 2024, legislation was introduced (see here and here) to reform a number of the features of the 340B drug discount program, including transparency, contract pharmacy requirements, and federal agency oversight.

Who’s Guarding the Hen House?

The Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General over the last 5-10 years have asked HRSA to better define an “eligible” patient, to have more specifics concerning hospital eligibility criteria, and to have better oversight of the program to avoid duplicate discounts. HRSA has said that it doesn’t have the ability or the funding to achieve some of these goals. Consequently, little has been done on any of these fronts, creating frustration among pharmaceutical manufacturers and those calling for more oversight of the program to ensure that eligible patients are receiving the benefit of 340B pricing. Again, these frustrations are not pointed at the initial federally qualified centers or “grantees.”

HRSA now audits 200 covered entities a year, which is less than 2% of entities participating in the 340B program. HRSA expects the 340B entities themselves to have an oversight committee in place to ensure compliance with program requirements.

So essentially, the fox is guarding the hen house?

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of advocacy and government affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

The 340B Drug Pricing Program began as a noble endeavor, a lifeline designed to help safety-net providers deliver affordable care to America’s most vulnerable populations. However, over the years, this well-intentioned program has strayed from its original purpose, becoming a lucrative space where profits often outweigh patients. Loopholes, lax oversight, and unchecked expansion have allowed some powerful players, such as certain disproportionate share hospitals and their “child sites” as well as for-profit pharmacies, to exploit the system. What was once a program to uplift underserved communities now risks becoming a case study in how good intentions can go astray without accountability.

What exactly is this “340B program” that has captured headlines and the interest of legislatures around the country? What ensures that pharmaceutical manufacturers continue to participate in this program? How lucrative is it? How have underserved populations benefited and how is that measured?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program was established in 1992 under the Public Health Service Act. Its primary goal is to enable covered entities (such as hospitals and clinics serving low-income and uninsured patients) to purchase outpatient drugs from pharmaceutical manufacturers at significantly reduced prices in order to support their care of the low-income and underserved populations. Drug makers are required to participate in this program as a condition of their participation in Medicaid and Medicare Part B and offer these steep discounts to covered entities if they want their medications to be available to 38% of patients nationwide.

The hospitals that make up 78% of the program’s spending are known as disproportionate share hospitals (DSHs). These hospitals must be nonprofit and have at least an 11.75% “disproportionate” share of low-income Medicare or Medicaid inpatients. The other types of non-hospital entities qualifying for 340B pricing are known as initial “federal grantees.” Some examples include federally qualified health centers (FQHC), Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grantees, and other types of specialized clinics, such as hemophilia treatment centers. It needs to be noted up front that it is not these initial non-hospital federal grantees that need more oversight or reform, since according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) 2023 report they make up only 22% of all program spending. It is the large, predominantly DSH health systems that are profiting immensely through exponential growth of their clinics and contract pharmacies. However, these health systems have not been able to show exactly who are their eligible patients and how they have been benefiting them.

When the 340B program was established to offer financial relief to hospitals and clinics taking care of the uninsured, it allowed them to save 20%-50% on drug purchases, which could be reinvested in patient care services. It was hoped that savings from the program could be used to provide free or low-cost medications, free vaccines, and other essential health services, essentially allowing safety-net providers to serve their communities despite financial constraints. The initial grantees are fulfilling that mission, but there are concerns regarding DSHs. (See the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organization’s 340B explanatory statement and policy position for more.)

Why Should Independent Practice Physicians Care About This?

Independent doctors should care about the lack of oversight in the 340B program because it affects healthcare costs, patient assistance, market competition, and access to affordable care for underserved and uninsured patients.

It also plays a strong hand in the healthcare consolidation that continues to threaten private physician practices. These acquisitions threaten the viability of independent practices in a variety of specialties across the United States, including rheumatology. HRSA allows 340B-covered entities to register their off-campus outpatient facilities, or child sites, under their 340B designation. Covered entities can acquire drugs at the 340B price, while imposing markups on the reimbursement they submit to private insurance. The additional revenue these covered entities can pocket provides them with a cash flow advantage that physician practices and outpatient clinics will never be able to actualize. This uneven playing field may make rheumatology practices more susceptible to hospital acquisitions. In fact, between 2016 and 2022, large 340B hospitals were responsible for approximately 80% of hospital acquisitions.

Perhaps the most important reason that we should all be concerned about the trajectory of this well-meaning program is that we have seen patients with hospital debt being sued by DSHs who receive 340B discounts so that they can take care of the low-income patients they are suing. We have seen Medicaid patients be turned away from a DSH clinic after being discharged from that hospital, because the hospital had reached its disproportionate share (11.75%) of inpatient Medicare and Medicaid patients. While not illegal, that type of behavior by covered entities is WRONG! Oversight and reform are needed if the 340B program is going to live up to its purpose and not be just another well-intentioned program not fulfilling its mission.

Areas of Concern

There has been controversy regarding the limited oversight of the 340B program by HRSA, leading to abuse of the program. There are deep concerns regarding a lack of transparency in how savings from the program are being used, and there are concerns about the challenges associated with accurate tracking and reporting of 340B discounts, possibly leading to the duplication of discounts for both Medicaid and 340B. For example, a “duplicate discount” occurs if a manufacturer sells medications to a DSH at the 340B price and later pays a Medicaid rebate on the same drug. The extent of duplicate discounts in the 340B program is unknown. However, an audit of 1,536 cases conducted by HRSA between 2012 and 2019 found 429 instances of noncompliance related to duplicate discounts, which is nearly 30% of cases.

DSHs and their contracted pharmacies have been accused of exploiting the program by increasing the number of contract pharmacies and expanding the number of offsite outpatient clinics to maximize profits. As of mid-2024, the number of 340B contract pharmacies, counted by Drug Channels Institute (DCI), numbered 32,883 unique locations. According to DCI, the top five pharmacies in the program happen also to be among the top pharmacy revenue generators and are “for-profit.” They are CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Express Scripts, and Optum RX. Additionally, a study in JAMA Health Forum showed that, from 2011 to 2019, contract pharmacies in areas with the lowest income decreased by 5.6% while those in the most affluent neighborhoods grew by 5%.

There also has been tremendous growth in the number of covered entities in the 340B program, which grew from just over 8,100 in 2000 to 50,000 in 2020. Before 2004, DSHs made up less than 10% of these entities, but by 2020, they accounted for over 60%. Another study shows that DSHs are expanding their offsite outpatient clinics (“child clinics”) into the affluent neighborhoods serving commercially insured patients who are not low income, to capture the high commercial reimbursements for medications they acquired at steeply discounted prices. This clearly is diverting care away from the intended beneficiaries of the 340B program.

Furthermore, DSHs have been acquiring specialty practices that prescribe some of the most expensive drugs, in order to take advantage of commercial reimbursement for medications that were acquired at the 340B discount price. Independent oncology practices have complained specifically about this happening in their area, where in some cases the DSHs have “stolen” their patients to profit off of the 340B pricing margins. This has the unintended consequence of increasing government spending, according to a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that showed price markups at 340B eligible hospitals were 6.59 times as high as those in independent physician practices after accounting for drug, patient, and geographic factors.

Legal Challenges and Legislation

On May 21, 2024, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit issued a unanimous decision in favor of drug manufacturers, finding that certain manufacturer restrictions on the use of contract pharmacies under the 340B drug pricing program are permissible. The court’s decision follows a lower court (3rd Circuit) ruling which concluded that the 340B statute does not require manufacturers to deliver 340B drugs to an “unlimited number of contract pharmacies.” We’re still awaiting a decision from the 7th Circuit Court on a similar issue. If the 7th Circuit agrees with the government, creating a split decision, there is an increase in the likelihood that the Supreme Court would take up the case.

Johnson & Johnson has also sued the federal government for blocking their proposed use of a rebate model for DSHs that purchase through 340B two of its medications, Stelara and Xarelto, whose maximum fair price was negotiated through the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. J&J states this would ensure that the claims are actually acquired and dispensed by a covered 340B entity, as well as ensuring there are no duplicate discounts as statutorily required by the IRA. When initially proposed, HRSA threatened to remove J&J’s access to Medicare and Medicaid if it pursued this change. J&J’s suit challenges that decision.

However, seven states (Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, and West Virginia) have been active on this issue, passing laws to prevent manufacturers from limiting contract pharmacies’ ability to acquire 340B-discounted drugs. The model legislation also bans restrictions on the “number, location, ownership, or type of 340B contract pharmacy.”

It should also be noted that there are states that are looking for ways to encourage certain independent private practice specialties (such as gastroenterology and rheumatology) to see Medicaid patients, as well as increase testing for sexually transmitted diseases, by offering the possibility of obtaining 340B pricing in their clinics.

Shifting our focus to Congress, six bipartisan Senators, known as the Group of 6, are working to modernize the 340B program, which hasn’t been updated since the original law in 1992. In 2024, legislation was introduced (see here and here) to reform a number of the features of the 340B drug discount program, including transparency, contract pharmacy requirements, and federal agency oversight.

Who’s Guarding the Hen House?

The Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General over the last 5-10 years have asked HRSA to better define an “eligible” patient, to have more specifics concerning hospital eligibility criteria, and to have better oversight of the program to avoid duplicate discounts. HRSA has said that it doesn’t have the ability or the funding to achieve some of these goals. Consequently, little has been done on any of these fronts, creating frustration among pharmaceutical manufacturers and those calling for more oversight of the program to ensure that eligible patients are receiving the benefit of 340B pricing. Again, these frustrations are not pointed at the initial federally qualified centers or “grantees.”

HRSA now audits 200 covered entities a year, which is less than 2% of entities participating in the 340B program. HRSA expects the 340B entities themselves to have an oversight committee in place to ensure compliance with program requirements.

So essentially, the fox is guarding the hen house?

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of advocacy and government affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

The 340B Drug Pricing Program began as a noble endeavor, a lifeline designed to help safety-net providers deliver affordable care to America’s most vulnerable populations. However, over the years, this well-intentioned program has strayed from its original purpose, becoming a lucrative space where profits often outweigh patients. Loopholes, lax oversight, and unchecked expansion have allowed some powerful players, such as certain disproportionate share hospitals and their “child sites” as well as for-profit pharmacies, to exploit the system. What was once a program to uplift underserved communities now risks becoming a case study in how good intentions can go astray without accountability.

What exactly is this “340B program” that has captured headlines and the interest of legislatures around the country? What ensures that pharmaceutical manufacturers continue to participate in this program? How lucrative is it? How have underserved populations benefited and how is that measured?

The 340B Drug Pricing Program was established in 1992 under the Public Health Service Act. Its primary goal is to enable covered entities (such as hospitals and clinics serving low-income and uninsured patients) to purchase outpatient drugs from pharmaceutical manufacturers at significantly reduced prices in order to support their care of the low-income and underserved populations. Drug makers are required to participate in this program as a condition of their participation in Medicaid and Medicare Part B and offer these steep discounts to covered entities if they want their medications to be available to 38% of patients nationwide.

The hospitals that make up 78% of the program’s spending are known as disproportionate share hospitals (DSHs). These hospitals must be nonprofit and have at least an 11.75% “disproportionate” share of low-income Medicare or Medicaid inpatients. The other types of non-hospital entities qualifying for 340B pricing are known as initial “federal grantees.” Some examples include federally qualified health centers (FQHC), Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grantees, and other types of specialized clinics, such as hemophilia treatment centers. It needs to be noted up front that it is not these initial non-hospital federal grantees that need more oversight or reform, since according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) 2023 report they make up only 22% of all program spending. It is the large, predominantly DSH health systems that are profiting immensely through exponential growth of their clinics and contract pharmacies. However, these health systems have not been able to show exactly who are their eligible patients and how they have been benefiting them.

When the 340B program was established to offer financial relief to hospitals and clinics taking care of the uninsured, it allowed them to save 20%-50% on drug purchases, which could be reinvested in patient care services. It was hoped that savings from the program could be used to provide free or low-cost medications, free vaccines, and other essential health services, essentially allowing safety-net providers to serve their communities despite financial constraints. The initial grantees are fulfilling that mission, but there are concerns regarding DSHs. (See the Coalition of State Rheumatology Organization’s 340B explanatory statement and policy position for more.)

Why Should Independent Practice Physicians Care About This?

Independent doctors should care about the lack of oversight in the 340B program because it affects healthcare costs, patient assistance, market competition, and access to affordable care for underserved and uninsured patients.

It also plays a strong hand in the healthcare consolidation that continues to threaten private physician practices. These acquisitions threaten the viability of independent practices in a variety of specialties across the United States, including rheumatology. HRSA allows 340B-covered entities to register their off-campus outpatient facilities, or child sites, under their 340B designation. Covered entities can acquire drugs at the 340B price, while imposing markups on the reimbursement they submit to private insurance. The additional revenue these covered entities can pocket provides them with a cash flow advantage that physician practices and outpatient clinics will never be able to actualize. This uneven playing field may make rheumatology practices more susceptible to hospital acquisitions. In fact, between 2016 and 2022, large 340B hospitals were responsible for approximately 80% of hospital acquisitions.

Perhaps the most important reason that we should all be concerned about the trajectory of this well-meaning program is that we have seen patients with hospital debt being sued by DSHs who receive 340B discounts so that they can take care of the low-income patients they are suing. We have seen Medicaid patients be turned away from a DSH clinic after being discharged from that hospital, because the hospital had reached its disproportionate share (11.75%) of inpatient Medicare and Medicaid patients. While not illegal, that type of behavior by covered entities is WRONG! Oversight and reform are needed if the 340B program is going to live up to its purpose and not be just another well-intentioned program not fulfilling its mission.

Areas of Concern

There has been controversy regarding the limited oversight of the 340B program by HRSA, leading to abuse of the program. There are deep concerns regarding a lack of transparency in how savings from the program are being used, and there are concerns about the challenges associated with accurate tracking and reporting of 340B discounts, possibly leading to the duplication of discounts for both Medicaid and 340B. For example, a “duplicate discount” occurs if a manufacturer sells medications to a DSH at the 340B price and later pays a Medicaid rebate on the same drug. The extent of duplicate discounts in the 340B program is unknown. However, an audit of 1,536 cases conducted by HRSA between 2012 and 2019 found 429 instances of noncompliance related to duplicate discounts, which is nearly 30% of cases.

DSHs and their contracted pharmacies have been accused of exploiting the program by increasing the number of contract pharmacies and expanding the number of offsite outpatient clinics to maximize profits. As of mid-2024, the number of 340B contract pharmacies, counted by Drug Channels Institute (DCI), numbered 32,883 unique locations. According to DCI, the top five pharmacies in the program happen also to be among the top pharmacy revenue generators and are “for-profit.” They are CVS, Walgreens, Walmart, Express Scripts, and Optum RX. Additionally, a study in JAMA Health Forum showed that, from 2011 to 2019, contract pharmacies in areas with the lowest income decreased by 5.6% while those in the most affluent neighborhoods grew by 5%.

There also has been tremendous growth in the number of covered entities in the 340B program, which grew from just over 8,100 in 2000 to 50,000 in 2020. Before 2004, DSHs made up less than 10% of these entities, but by 2020, they accounted for over 60%. Another study shows that DSHs are expanding their offsite outpatient clinics (“child clinics”) into the affluent neighborhoods serving commercially insured patients who are not low income, to capture the high commercial reimbursements for medications they acquired at steeply discounted prices. This clearly is diverting care away from the intended beneficiaries of the 340B program.

Furthermore, DSHs have been acquiring specialty practices that prescribe some of the most expensive drugs, in order to take advantage of commercial reimbursement for medications that were acquired at the 340B discount price. Independent oncology practices have complained specifically about this happening in their area, where in some cases the DSHs have “stolen” their patients to profit off of the 340B pricing margins. This has the unintended consequence of increasing government spending, according to a study in the New England Journal of Medicine that showed price markups at 340B eligible hospitals were 6.59 times as high as those in independent physician practices after accounting for drug, patient, and geographic factors.

Legal Challenges and Legislation

On May 21, 2024, the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit issued a unanimous decision in favor of drug manufacturers, finding that certain manufacturer restrictions on the use of contract pharmacies under the 340B drug pricing program are permissible. The court’s decision follows a lower court (3rd Circuit) ruling which concluded that the 340B statute does not require manufacturers to deliver 340B drugs to an “unlimited number of contract pharmacies.” We’re still awaiting a decision from the 7th Circuit Court on a similar issue. If the 7th Circuit agrees with the government, creating a split decision, there is an increase in the likelihood that the Supreme Court would take up the case.

Johnson & Johnson has also sued the federal government for blocking their proposed use of a rebate model for DSHs that purchase through 340B two of its medications, Stelara and Xarelto, whose maximum fair price was negotiated through the Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program. J&J states this would ensure that the claims are actually acquired and dispensed by a covered 340B entity, as well as ensuring there are no duplicate discounts as statutorily required by the IRA. When initially proposed, HRSA threatened to remove J&J’s access to Medicare and Medicaid if it pursued this change. J&J’s suit challenges that decision.

However, seven states (Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Minnesota, Missouri, Mississippi, and West Virginia) have been active on this issue, passing laws to prevent manufacturers from limiting contract pharmacies’ ability to acquire 340B-discounted drugs. The model legislation also bans restrictions on the “number, location, ownership, or type of 340B contract pharmacy.”

It should also be noted that there are states that are looking for ways to encourage certain independent private practice specialties (such as gastroenterology and rheumatology) to see Medicaid patients, as well as increase testing for sexually transmitted diseases, by offering the possibility of obtaining 340B pricing in their clinics.

Shifting our focus to Congress, six bipartisan Senators, known as the Group of 6, are working to modernize the 340B program, which hasn’t been updated since the original law in 1992. In 2024, legislation was introduced (see here and here) to reform a number of the features of the 340B drug discount program, including transparency, contract pharmacy requirements, and federal agency oversight.

Who’s Guarding the Hen House?

The Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General over the last 5-10 years have asked HRSA to better define an “eligible” patient, to have more specifics concerning hospital eligibility criteria, and to have better oversight of the program to avoid duplicate discounts. HRSA has said that it doesn’t have the ability or the funding to achieve some of these goals. Consequently, little has been done on any of these fronts, creating frustration among pharmaceutical manufacturers and those calling for more oversight of the program to ensure that eligible patients are receiving the benefit of 340B pricing. Again, these frustrations are not pointed at the initial federally qualified centers or “grantees.”

HRSA now audits 200 covered entities a year, which is less than 2% of entities participating in the 340B program. HRSA expects the 340B entities themselves to have an oversight committee in place to ensure compliance with program requirements.

So essentially, the fox is guarding the hen house?

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of advocacy and government affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

‘Reform School’ for Pharmacy Benefit Managers: How Might Legislation Help Patients?

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

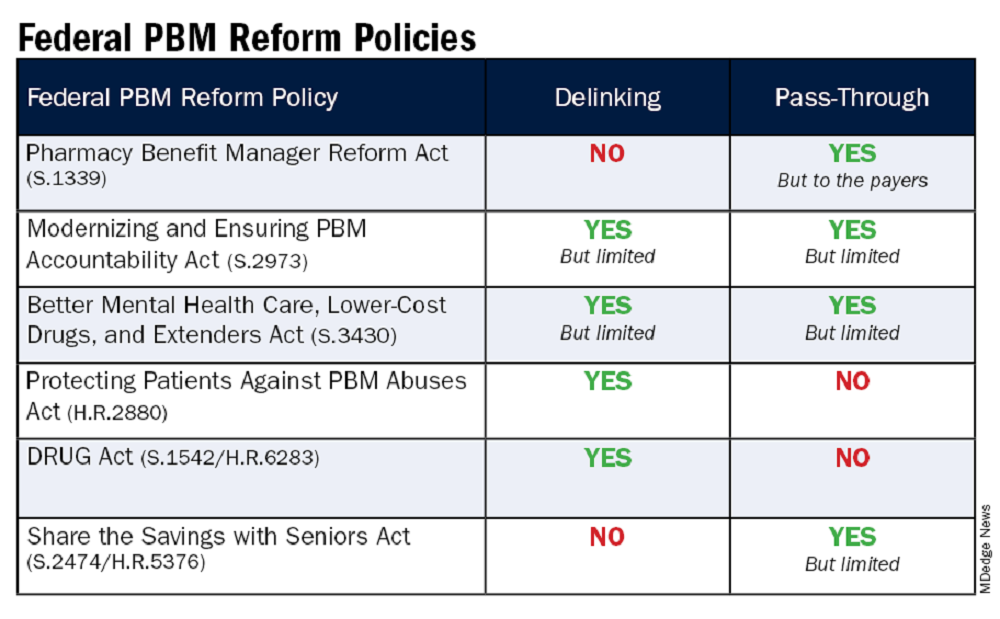

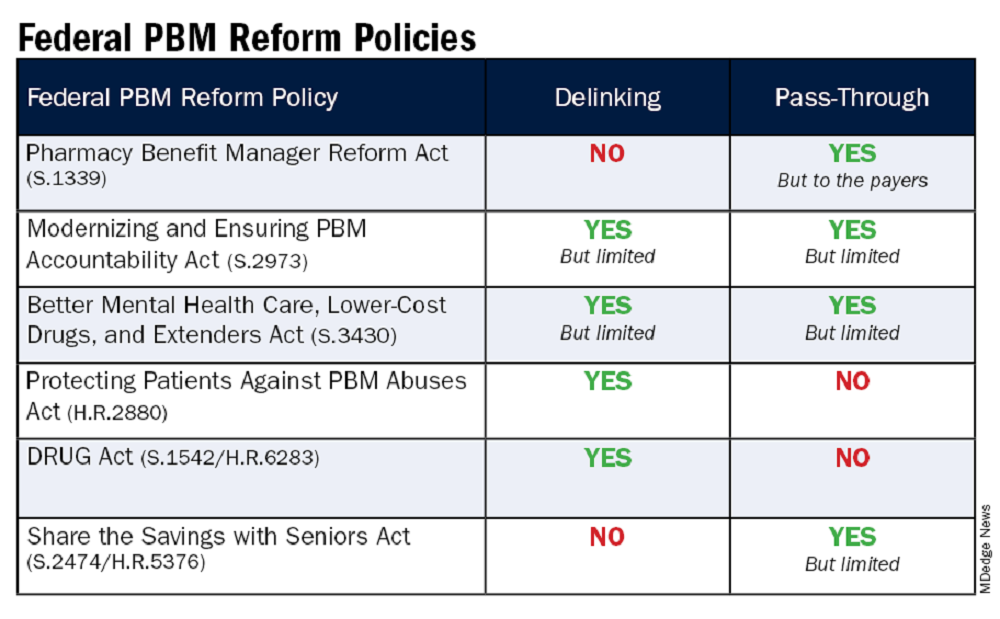

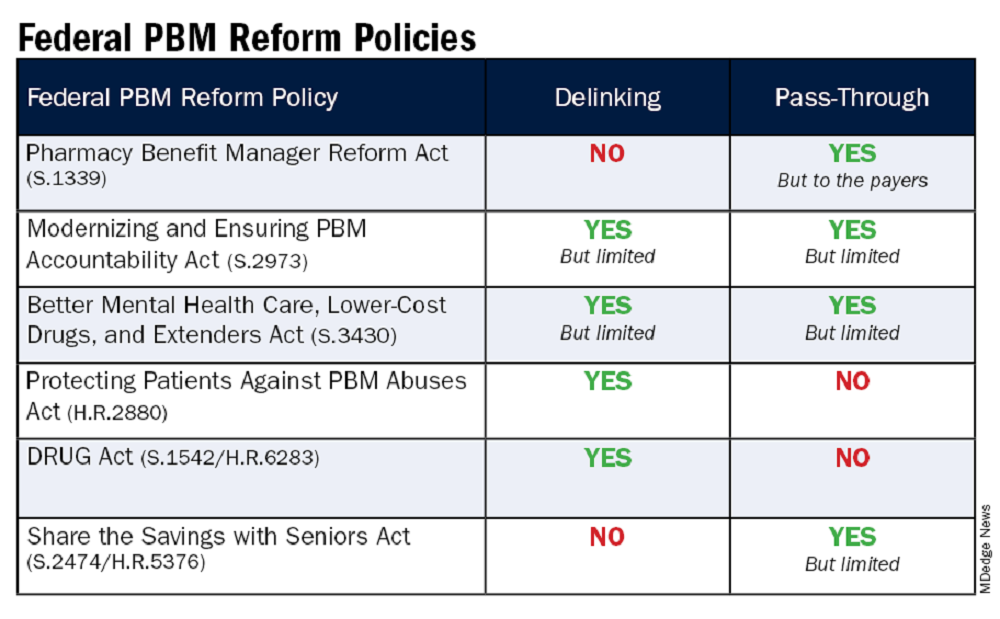

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

The term “reform school” is a bit outdated. It used to refer to institutions where young offenders were sent instead of prison. Some argue that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) should bypass reform school and go straight to prison. “PBM reform” has become a ubiquitous term, encompassing any legislative or regulatory efforts aimed at curbing PBMs’ bad behavior. When discussing PBM reform, it’s crucial to understand the various segments of the healthcare system affected by PBMs. This complexity often makes it challenging to determine what these reform packages would actually achieve and who they would benefit.

Pharmacists have long been vocal critics of PBMs, and while their issues are extremely important, it is essential to remember that the ultimate victims of PBM misconduct, in terms of access to care, are patients. At some point, we will all be patients, making this issue universally relevant. It has been quite challenging to follow federal legislation on this topic as these packages attempt to address a number of bad behaviors by PBMs affecting a variety of victims. This discussion will examine those reforms that would directly improve patient’s access to available and affordable medications.

Policy Categories of PBM Reform

There are five policy categories of PBM reform legislation overall, including three that have the greatest potential to directly address patient needs. The first is patient access to medications (utilization management, copay assistance, prior authorization, etc.), followed by delinking drug list prices from PBM income and pass-through of price concessions from the manufacturer. The remaining two categories involve transparency and pharmacy-facing reform, both of which are very important. However, this discussion will revolve around the first three categories. It should be noted that many of the legislation packages addressing the categories of patient access, delinking, and pass-through also include transparency issues, particularly as they relate to pharmacy-facing issues.

Patient Access to Medications — Step Therapy Legislation

One of the major obstacles to patient access to medications is the use of PBM utilization management tools such as step therapy (“fail first”), prior authorizations, nonmedical switching, and formulary exclusions. These tools dictate when patients can obtain necessary medications and for how long patients who are stable on their current treatments can remain on them.

While many states have enacted step therapy reforms to prevent stable patients from being whip-sawed between medications that maximize PBM profits (often labeled as “savings”), these state protections apply only to state-regulated health plans. These include fully insured health plans and those offered through the Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplace. It also includes state employees, state corrections, and, in some cases, state labor unions. State legislation does not extend to patients covered by employer self-insured health plans, called ERISA plans for the federal law that governs employee benefit plans, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act. These ERISA plans include nearly 35 million people nationwide.

This is where the Safe Step Act (S.652/H.R.2630) becomes crucial, as it allows employees to request exceptions to harmful fail-first protocols. The bill has gained significant momentum, having been reported out of the Senate HELP Committee and discussed in House markups. The Safe Step Act would mandate that an exception to a step therapy protocol must be granted if:

- The required treatment has been ineffective

- The treatment is expected to be ineffective, and delaying effective treatment would lead to irreversible consequences

- The treatment will cause or is likely to cause an adverse reaction

- The treatment is expected to prevent the individual from performing daily activities or occupational responsibilities

- The individual is stable on their current prescription drugs

- There are other circumstances as determined by the Employee Benefits Security Administration

This legislation is vital for ensuring that patients have timely access to the medications they need without unnecessary delays or disruptions.

Patient Access to Medications — Prior Authorizations

Another significant issue affecting patient access to medications is prior authorizations (PAs). According to an American Medical Association survey, nearly one in four physicians (24%) report that a PA has led to a serious adverse event for a patient in their care. In rheumatology, PAs often result in delays in care (even for those initially approved) and a significant increase in steroid usage. In particular, PAs in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are harmful to Medicare beneficiaries.

The Improving Seniors’ Timely Access to Care Act (H.R.8702 / S.4532) aims to reform PAs used in MA plans, making the process more efficient and transparent to improve access to care for seniors. Unfortunately, it does not cover Part D drugs and may only cover Part B drugs depending on the MA plan’s benefit package. Here are the key provisions of the act:

- Electronic PA: Implementing real-time decisions for routinely approved items and services.

- Transparency: Requiring annual publication of PA information, such as the percentage of requests approved and the average response time.

- Quality and Timeliness Standards: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) will set standards for the quality and timeliness of PA determinations.

- Streamlining Approvals: Simplifying the approval process and reducing the time allowed for health plans to consider PA requests.

This bill passed the House in September 2022 but stalled in the Senate because of an unfavorable Congressional Budget Office score. CMS has since finalized portions of this bill via regulation, zeroing out the CBO score and increasing the chances of its passage.

Delinking Drug Prices from PBM Income and Pass-Through of Price Concessions

Affordability is a crucial aspect of accessibility, especially when it comes to medications. Over the years, we’ve learned that PBMs often favor placing the highest list price drugs on formularies because the rebates and various fees they receive from manufacturers are based on a percentage of the list price. In other words, the higher the medication’s price, the more money the PBM makes.

This practice is evident in both commercial and government formularies, where brand-name drugs are often preferred, while lower-priced generics are either excluded or placed on higher tiers. As a result, while major PBMs benefit from these rebates and fees, patients continue to pay their cost share based on the list price of the medication.

To improve the affordability of medications, a key aspect of PBM reform should be to disincentivize PBMs from selecting higher-priced medications and/or require the pass-through of manufacturer price concessions to patients.

Several major PBM reform bills are currently being considered that address either the delinking of price concessions from the list price of the drug or some form of pass-through of these concessions. These reforms are essential to ensure that patients can access affordable medications without being burdened by inflated costs.

The legislation includes the Pharmacy Benefit Manager Reform Act (S.1339); the Modernizing & Ensuring PBM Accountability Act (S.2973); the Better Mental Health Care, Lower Cost Drugs, and Extenders Act (S.3430); the Protecting Patients Against PBM Abuses Act (H.R. 2880); the DRUG Act (S.2474 / H.R.6283); and the Share the Savings with Seniors Act (S.2474 / H.R.5376).

As with all legislation, there are limitations and compromises in each of these. However, these bills are a good first step in addressing PBM remuneration (rebates and fees) based on the list price of the drug and/or passing through to the patient the benefit of manufacturer price concessions. By focusing on key areas like utilization management, delinking drug prices from PBM income, and allowing patients to directly benefit from manufacturer price concessions, we can work toward a more equitable and efficient healthcare system. Reigning in PBM bad behavior is a challenge, but the potential benefits for patient care and access make it a crucial fight worth pursuing.

Please help in efforts to improve patients’ access to available and affordable medications by contacting your representatives in Congress to impart to them the importance of passing legislation. The CSRO’s legislative map tool can help to inform you of the latest information on these and other bills and assist you in engaging with your representatives on them.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. She has no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

Fed Worker Health Plans Ban Maximizers and Copay Accumulators: Why Not for the Rest of the US?

The escalating costs of medications and the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country have drawn criticism from governments, regulators, and the media. Federal and state governments are exploring various strategies to mitigate this issue, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for drug price negotiations and the establishment of state Pharmaceutical Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). However, it’s uncertain whether these measures will effectively reduce patients’ medication expenses, given the tendency of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to favor more expensive drugs on their formularies and the implementation challenges faced by PDABs.

The question then arises: How can we promptly assist patients, especially those with multiple chronic conditions, in affording their healthcare? Many of these patients are enrolled in high-deductible plans and struggle to cover all their medical and pharmacy costs.

A significant obstacle to healthcare affordability emerged in 2018 with the introduction of Copay Accumulator Programs by PBMs. These programs prevent patients from applying manufacturer copay cards toward their deductible and maximum out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. The impact of these policies has been devastating, leading to decreased adherence to medications and delayed necessary medical procedures, such as colonoscopies. Copay accumulators do nothing to address the high cost of medical care. They merely shift the burden from insurance companies to patients.

There is a direct solution to help patients, particularly those burdened with high pharmacy bills, afford their medical care. It would be that all payments from patients, including manufacturer copay cards, count toward their deductible and maximum OOP costs. This should apply regardless of whether the insurance plan is fully funded or a self-insured employer plan. This would be an immediate step toward making healthcare more affordable for patients.

Copay Accumulator Programs

How did these detrimental policies, which have been proven to harm patients, originate? It’s interesting that health insurance policies for federal employees do not allow these programs and yet the federal government has done little to protect its citizens from these egregious policies. More on that later.

In 2018, insurance companies and PBMs conceived an idea to introduce what they called copay accumulator adjustment programs. These programs would prevent the use of manufacturer copay cards from counting toward patient deductibles or OOP maximums. They justified this by arguing that manufacturer copay cards encouraged patients to opt for higher-priced brand drugs when lower-cost generics were available.

However, data from IQVIA contradicts this claim. An analysis of copay card usage from 2013 to 2017 revealed that a mere 0.4% of these cards were used for brand-name drugs that had already lost their exclusivity. This indicates that the vast majority of copay cards were not being used to purchase more expensive brand-name drugs when cheaper, generic alternatives were available.

Another argument put forth by one of the large PBMs was that patients with high deductibles don’t have enough “skin in the game” due to their low premiums, and therefore don’t deserve to have their deductible covered by a copay card. This raises the question, “Does a patient with hemophilia or systemic lupus who can’t afford a low deductible plan not have ‘skin in the game’? Is that a fair assessment?” It’s disconcerting to see a multibillion-dollar company dictating who deserves to have their deductible covered. These policies clearly disproportionately harm patients with chronic illnesses, especially those with high deductibles. As a result, many organizations have labeled these policies as discriminatory.

Following the implementation of accumulator programs in 2018 and 2019, many patients were unaware that their copay cards weren’t contributing toward their deductibles. They were taken aback when specialty pharmacies informed them of owing substantial amounts because of unmet deductibles. Consequently, patients discontinued their medications, leading to disease progression and increased costs. The only downside for health insurers and PBMs was the negative publicity associated with patients losing medication access.

Maximizer Programs

By the end of 2019, the three major PBMs had devised a strategy to keep patients on their medication throughout the year, without counting copay cards toward the deductible, and found a way to profit more from these cards, sometimes quadrupling their value. This was the birth of the maximizer programs.

Maximizers exploit a “loophole” in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA defines Essential Healthcare Benefits (EHB); anything not listed as an EHB is deemed “non-essential.” As a result, neither personal payments nor copay cards count toward deductibles or OOP maximums. Patients were informed that neither their own money nor manufacturer copay cards would count toward their deductible/OOP max.

One of my patients was warned that without enrolling in the maximizer program through SaveOnSP (owned by Express Scripts), she would bear the full cost of the drug, and nothing would count toward her OOP max. Frightened, she enrolled and surrendered her manufacturer copay card to SaveOnSP. Maximizers pocket the maximum value of the copay card, even if it exceeds the insurance plan’s yearly cost share by threefold or more. To do this legally, PBMs increase the patient’s original cost share amount during the plan year to match the value of the manufacturer copay card.

Combating These Programs

Nineteen states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico have outlawed copay accumulators in health plans under state jurisdiction. I personally testified in Louisiana, leading to a ban in our state. CSRO’s award-winning map tool can show if your state has passed the ban on copay accumulator programs. However, many states have not passed bans on copay accumulators and self-insured employer groups, which fall under the Department of Labor and not state regulation, are still unaffected. There is also proposed federal legislation, the “Help Ensure Lower Patient Copays Act,” that would prohibit the use of copay accumulators in exchange plans. Despite having bipartisan support, it is having a hard time getting across the finish line in Congress.

In 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued a rule prohibiting accumulator programs in all plans if the product was a brand name without a generic alternative. Unfortunately, this rule was rescinded in 2021, allowing copay accumulators even if a lower-cost generic was available.

In a positive turn of events, the US District Court of the District of Columbia overturned the 2021 rule in late 2023, reinstating the 2020 ban on copay accumulators. However, HHS has yet to enforce this ban.

Double Standard

Why is it that our federal government refrains from enforcing bans on copay accumulators for the American public, yet the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM) in its 2024 health plan for federal employees has explicitly stated that it “will decline any arrangements which may manipulate the prescription drug benefit design or incorporate any programs such as copay maximizers, copay optimizers, or other similar programs as these types of benefit designs are not in the best interest of enrollees or the Government.”

If such practices are deemed unsuitable for federal employees, why are they considered acceptable for the rest of the American population? This discrepancy raises important questions about healthcare equity.

In conclusion, the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country is a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. The introduction of copay accumulator programs and maximizers by PBMs has led to decreased adherence to needed medications, as well as delay in important medical procedures, exacerbating this situation. An across-the-board ban on these programs would offer immediate relief to many families that no longer can afford needed care.

It is clear that more needs to be done to ensure that all patients, regardless of their financial situation or the nature of their health insurance plan, can afford the healthcare they need. This includes ensuring that patients are not penalized for using manufacturer copay cards to help cover their costs. As we move forward, it is crucial that we continue to advocate for policies that prioritize the health and well-being of all patients.

Dr. Feldman is a rheumatologist in private practice with The Rheumatology Group in New Orleans. She is the CSRO’s vice president of Advocacy and Government Affairs and its immediate past president, as well as past chair of the Alliance for Safe Biologic Medicines and a past member of the American College of Rheumatology insurance subcommittee. You can reach her at rhnews@mdedge.com.

The escalating costs of medications and the prevalence of medical bankruptcy in our country have drawn criticism from governments, regulators, and the media. Federal and state governments are exploring various strategies to mitigate this issue, including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for drug price negotiations and the establishment of state Pharmaceutical Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs). However, it’s uncertain whether these measures will effectively reduce patients’ medication expenses, given the tendency of pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to favor more expensive drugs on their formularies and the implementation challenges faced by PDABs.

The question then arises: How can we promptly assist patients, especially those with multiple chronic conditions, in affording their healthcare? Many of these patients are enrolled in high-deductible plans and struggle to cover all their medical and pharmacy costs.

A significant obstacle to healthcare affordability emerged in 2018 with the introduction of Copay Accumulator Programs by PBMs. These programs prevent patients from applying manufacturer copay cards toward their deductible and maximum out-of-pocket (OOP) costs. The impact of these policies has been devastating, leading to decreased adherence to medications and delayed necessary medical procedures, such as colonoscopies. Copay accumulators do nothing to address the high cost of medical care. They merely shift the burden from insurance companies to patients.

There is a direct solution to help patients, particularly those burdened with high pharmacy bills, afford their medical care. It would be that all payments from patients, including manufacturer copay cards, count toward their deductible and maximum OOP costs. This should apply regardless of whether the insurance plan is fully funded or a self-insured employer plan. This would be an immediate step toward making healthcare more affordable for patients.

Copay Accumulator Programs

How did these detrimental policies, which have been proven to harm patients, originate? It’s interesting that health insurance policies for federal employees do not allow these programs and yet the federal government has done little to protect its citizens from these egregious policies. More on that later.

In 2018, insurance companies and PBMs conceived an idea to introduce what they called copay accumulator adjustment programs. These programs would prevent the use of manufacturer copay cards from counting toward patient deductibles or OOP maximums. They justified this by arguing that manufacturer copay cards encouraged patients to opt for higher-priced brand drugs when lower-cost generics were available.

However, data from IQVIA contradicts this claim. An analysis of copay card usage from 2013 to 2017 revealed that a mere 0.4% of these cards were used for brand-name drugs that had already lost their exclusivity. This indicates that the vast majority of copay cards were not being used to purchase more expensive brand-name drugs when cheaper, generic alternatives were available.

Another argument put forth by one of the large PBMs was that patients with high deductibles don’t have enough “skin in the game” due to their low premiums, and therefore don’t deserve to have their deductible covered by a copay card. This raises the question, “Does a patient with hemophilia or systemic lupus who can’t afford a low deductible plan not have ‘skin in the game’? Is that a fair assessment?” It’s disconcerting to see a multibillion-dollar company dictating who deserves to have their deductible covered. These policies clearly disproportionately harm patients with chronic illnesses, especially those with high deductibles. As a result, many organizations have labeled these policies as discriminatory.

Following the implementation of accumulator programs in 2018 and 2019, many patients were unaware that their copay cards weren’t contributing toward their deductibles. They were taken aback when specialty pharmacies informed them of owing substantial amounts because of unmet deductibles. Consequently, patients discontinued their medications, leading to disease progression and increased costs. The only downside for health insurers and PBMs was the negative publicity associated with patients losing medication access.

Maximizer Programs

By the end of 2019, the three major PBMs had devised a strategy to keep patients on their medication throughout the year, without counting copay cards toward the deductible, and found a way to profit more from these cards, sometimes quadrupling their value. This was the birth of the maximizer programs.

Maximizers exploit a “loophole” in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA defines Essential Healthcare Benefits (EHB); anything not listed as an EHB is deemed “non-essential.” As a result, neither personal payments nor copay cards count toward deductibles or OOP maximums. Patients were informed that neither their own money nor manufacturer copay cards would count toward their deductible/OOP max.

One of my patients was warned that without enrolling in the maximizer program through SaveOnSP (owned by Express Scripts), she would bear the full cost of the drug, and nothing would count toward her OOP max. Frightened, she enrolled and surrendered her manufacturer copay card to SaveOnSP. Maximizers pocket the maximum value of the copay card, even if it exceeds the insurance plan’s yearly cost share by threefold or more. To do this legally, PBMs increase the patient’s original cost share amount during the plan year to match the value of the manufacturer copay card.

Combating These Programs