User login

A Review of Evidence and Safety for First-Line JAKi Use in PsA

Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) are a novel class of oral, targeted small-molecule inhibitors that are increasingly used to treat several different autoimmune conditions. In terms of rheumatologic indications, the FDA first approved tofacitinib (TOF) for use in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) unresponsive to methotrexate therapy. Eleven years later, the indications for JAKi use have expanded to include ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), among other diseases. As with any new therapeutic mechanism, there are questions as to how JAKi should be incorporated into the treatment paradigm of PsA. In this article, we briefly review the efficacy and safety data of these agents and discuss our approach to their use in PsA.

Two JAKi are currently FDA approved for the treatment of PsA: tofacitinib (TOF) and upadacitinib (UPA). Other JAKi, such as filgotinib and peficitinib, are only approved outside the United States and will not be discussed here.

TOF was originally studied in skin psoriasis (PsO) before 2 pivotal studies demonstrated efficacy in PsA. TOF or adalimumab (ADA) were compared with placebo in patients who had failed conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD).1 ACR20 response was superior with TOF 5 mg twice daily (BID) (50%) and 10 mg BID (61%) vs placebo (33%), and it was comparable to ADA (52%), which was used in this study as an active comparator. The overall rate of adverse events was similar with both doses of TOF when compared with ADA; however, patients taking TOF had numerically more cases of cancer, serious infection, and herpes zoster.

Another study evaluated TOF compared with placebo in patients with PsA who had an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapy.2 The study showed an ACR20 response of 50% in patients taking TOF 5 mg BID and 47% in patients taking 10 mg BID, compared with 24% in those taking placebo. Patients who received the 10 mg TOF dose continuously had higher rates of adverse events compared to TOF 5 mg, placebo, and patients who crossed over from placebo to TOF at either dose. In the TOF groups, there were cases of serious infection and herpes zoster, as well as 2 patients with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Following review of these data, the FDA approved only the 5 mg BID dose, and later an 11-mg daily extended-release formulation that was pharmacokinetically similar.

The efficacy for UPA in PsA was shown in 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. SELECT-PsA1 compared UPA at 2 doses, 15 mg and 30 mg daily, vs placebo and vs ADA in patients with biologic DMARD (bDMARD)-naïve PsA.3 This trial demonstrated superiority of UPA in the ACR20 response at both doses (71% and 79%, respectively) compared with placebo (36%). The 15-mg dose of UPA was comparable to ADA (65%), while the 30-mg dose achieved superiority compared to ADA. Secondary outcomes including skin activity, patient-reported symptoms, and inhibition of radiographic progression were also superior in UPA compared with placebo and similar or greater with UPA compared with ADA, depending on the specific outcome.4 SELECT-PsA2 compared UPA 15 mg, 30 mg, and placebo in patients with prior incomplete response or intolerance to a bDMARD.5 At week 12 of the study, patients taking UPA 15 mg and 30 mg had an ACR20 response of 57% and 64%, respectively, compared with placebo (24%). At week 24, minimal disease activity was achieved by 25% of patients taking UPA 15 mg and 29% of patients taking UPA 30 mg, which was superior to placebo (3%).

Both studies found a significant increase in infections, including serious infections, at the 30-mg UPA dose compared with the placebo and adalimumab groups. Cytopenia and elevated creatine kinase (CK) level also occurred more frequently in the UPA 30-mg group. Rates of cancer were low overall and comparable between the patients treated with UPA and ADA. Given the higher incidence of adverse events with the 30-mg dose and the relatively similar efficacy, the sponsor elected to submit only the lower dose to the FDA for approval.

In the last few years, concerns for safety with JAKi use grew after the publication of data from the ORAL SURVEILLANCE trial, an FDA-mandated, post-approval safety study of TOF in RA. In this trial, patients with active RA over 50 years of age and with at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor were randomized to TOF at 1 of 2 doses, 5 mg or 10 mg BID, or a TNFi.6 This trial was designed as a noninferiority study, and TOF did not meet the noninferiority threshold compared to TNFi, with hazard ratios of 1.33 and 1.48 for MACE and malignancy, respectively. The results of this trial prompted the FDA to add a black box warning to the label for all JAKi, pointing out the risk of malignancy and MACE, as well as infection, mortality, and thrombosis.

In the ORAL SURVEILLANCE trial, the increased risk of MACE and malignancy was primarily seen in the study patients with high risk for a cardiovascular event. To address the question of whether a similar risk profile exists when using JAKi to treat PsA, or whether this is a disease-specific process related to RA, a post hoc analysis of 3 PsA trials and 7 PsO trials of patients treated with TOF was conducted.7 The analysis found that patients with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or metabolic syndrome, or patients at high risk for ASCVD (score > 20%) had increased incidence rates of MACE compared with those with low risk scores for ASCVD. Interestingly, as in RA, increased incidence rates of malignancy were seen in patients with preexisting or at high risk for ASCVD.

While the FDA recommends JAKi use in patients who have failed or are inappropriate for treatment with a TNFi, we would consider the use of JAKi for first-line therapy in PsA on an individual basis. One advantage of JAKi is their efficacy across multiple PsA domains, including peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin disease (although the approved dose of TOF was not statistically effective for PsO in the pivotal trials). Based on this efficacy, we believe that patients with overlapping, multifaceted disease may benefit the most from these medications. Patient risk factors and comorbidities are a prominent consideration in our use of JAKi to ensure safety, as the risk for MACE and malignancy is informed partly by baseline cardiovascular status. In younger patients without cardiovascular risk factors, JAKi may be a strong candidate for first-line therapy, particularly in patients averse to subcutaneous or intravenous therapy. We do counsel all patients on the increased risk of infection, and we do recommend inactivated herpes zoster vaccination in previously unvaccinated patients planning to start JAKi therapy.

On the horizon are the development of novel, oral agents targeting tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which is a member of the JAK family of signaling proteins. In fact, the TYK2 inhibitor deucravacitinib was approved by the FDA in 2022 for the treatment of PsO. TYK2 inhibitors appear to have the advantage of a more selective mechanism of action, with fewer off-target effects. There were fewer adverse events in the deucravacitinib trials, which led to its prompt PsO authorization, and the FDA approval for the drug did not include the same black box warning that appears in the label for other JAKi.8 A phase 2 study showed early promise for the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib in PsA.9 Further investigation will be needed to better understand the role of deucravacitinib and other TYK2 inhibitors being developed for the treatment of PsA. In the meantime, JAKi continue to be a prominent consideration for first-line PsA therapy in a carefully selected patient population.

Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1537-1550.

Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1525-1536.

McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1227-1239.

McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 2-year results from the phase 3 SELECT-PsA 1 study. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;10(1):275-292.

Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Anderson JK, et al. Upadacitinib for psoriatic arthritis refractory to biologics: SELECT-PsA 2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(3):312-320.

Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316-326.

Kristensen LE, Strober B, Poddubnyy D, et al. Association between baseline cardiovascular risk and incidence rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis receiving tofacitinib. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2023;15:1759720X221149965.

Dolgin E. TYK2-blocking agent showcases power of atypical kinase. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(12):1701-1704.

Mease PJ, Deodhar AA, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective TYK2 inhibitor, deucravacitinib, in a phase II trial in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(6):815-822.

Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) are a novel class of oral, targeted small-molecule inhibitors that are increasingly used to treat several different autoimmune conditions. In terms of rheumatologic indications, the FDA first approved tofacitinib (TOF) for use in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) unresponsive to methotrexate therapy. Eleven years later, the indications for JAKi use have expanded to include ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), among other diseases. As with any new therapeutic mechanism, there are questions as to how JAKi should be incorporated into the treatment paradigm of PsA. In this article, we briefly review the efficacy and safety data of these agents and discuss our approach to their use in PsA.

Two JAKi are currently FDA approved for the treatment of PsA: tofacitinib (TOF) and upadacitinib (UPA). Other JAKi, such as filgotinib and peficitinib, are only approved outside the United States and will not be discussed here.

TOF was originally studied in skin psoriasis (PsO) before 2 pivotal studies demonstrated efficacy in PsA. TOF or adalimumab (ADA) were compared with placebo in patients who had failed conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD).1 ACR20 response was superior with TOF 5 mg twice daily (BID) (50%) and 10 mg BID (61%) vs placebo (33%), and it was comparable to ADA (52%), which was used in this study as an active comparator. The overall rate of adverse events was similar with both doses of TOF when compared with ADA; however, patients taking TOF had numerically more cases of cancer, serious infection, and herpes zoster.

Another study evaluated TOF compared with placebo in patients with PsA who had an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapy.2 The study showed an ACR20 response of 50% in patients taking TOF 5 mg BID and 47% in patients taking 10 mg BID, compared with 24% in those taking placebo. Patients who received the 10 mg TOF dose continuously had higher rates of adverse events compared to TOF 5 mg, placebo, and patients who crossed over from placebo to TOF at either dose. In the TOF groups, there were cases of serious infection and herpes zoster, as well as 2 patients with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Following review of these data, the FDA approved only the 5 mg BID dose, and later an 11-mg daily extended-release formulation that was pharmacokinetically similar.

The efficacy for UPA in PsA was shown in 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. SELECT-PsA1 compared UPA at 2 doses, 15 mg and 30 mg daily, vs placebo and vs ADA in patients with biologic DMARD (bDMARD)-naïve PsA.3 This trial demonstrated superiority of UPA in the ACR20 response at both doses (71% and 79%, respectively) compared with placebo (36%). The 15-mg dose of UPA was comparable to ADA (65%), while the 30-mg dose achieved superiority compared to ADA. Secondary outcomes including skin activity, patient-reported symptoms, and inhibition of radiographic progression were also superior in UPA compared with placebo and similar or greater with UPA compared with ADA, depending on the specific outcome.4 SELECT-PsA2 compared UPA 15 mg, 30 mg, and placebo in patients with prior incomplete response or intolerance to a bDMARD.5 At week 12 of the study, patients taking UPA 15 mg and 30 mg had an ACR20 response of 57% and 64%, respectively, compared with placebo (24%). At week 24, minimal disease activity was achieved by 25% of patients taking UPA 15 mg and 29% of patients taking UPA 30 mg, which was superior to placebo (3%).

Both studies found a significant increase in infections, including serious infections, at the 30-mg UPA dose compared with the placebo and adalimumab groups. Cytopenia and elevated creatine kinase (CK) level also occurred more frequently in the UPA 30-mg group. Rates of cancer were low overall and comparable between the patients treated with UPA and ADA. Given the higher incidence of adverse events with the 30-mg dose and the relatively similar efficacy, the sponsor elected to submit only the lower dose to the FDA for approval.

In the last few years, concerns for safety with JAKi use grew after the publication of data from the ORAL SURVEILLANCE trial, an FDA-mandated, post-approval safety study of TOF in RA. In this trial, patients with active RA over 50 years of age and with at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor were randomized to TOF at 1 of 2 doses, 5 mg or 10 mg BID, or a TNFi.6 This trial was designed as a noninferiority study, and TOF did not meet the noninferiority threshold compared to TNFi, with hazard ratios of 1.33 and 1.48 for MACE and malignancy, respectively. The results of this trial prompted the FDA to add a black box warning to the label for all JAKi, pointing out the risk of malignancy and MACE, as well as infection, mortality, and thrombosis.

In the ORAL SURVEILLANCE trial, the increased risk of MACE and malignancy was primarily seen in the study patients with high risk for a cardiovascular event. To address the question of whether a similar risk profile exists when using JAKi to treat PsA, or whether this is a disease-specific process related to RA, a post hoc analysis of 3 PsA trials and 7 PsO trials of patients treated with TOF was conducted.7 The analysis found that patients with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or metabolic syndrome, or patients at high risk for ASCVD (score > 20%) had increased incidence rates of MACE compared with those with low risk scores for ASCVD. Interestingly, as in RA, increased incidence rates of malignancy were seen in patients with preexisting or at high risk for ASCVD.

While the FDA recommends JAKi use in patients who have failed or are inappropriate for treatment with a TNFi, we would consider the use of JAKi for first-line therapy in PsA on an individual basis. One advantage of JAKi is their efficacy across multiple PsA domains, including peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin disease (although the approved dose of TOF was not statistically effective for PsO in the pivotal trials). Based on this efficacy, we believe that patients with overlapping, multifaceted disease may benefit the most from these medications. Patient risk factors and comorbidities are a prominent consideration in our use of JAKi to ensure safety, as the risk for MACE and malignancy is informed partly by baseline cardiovascular status. In younger patients without cardiovascular risk factors, JAKi may be a strong candidate for first-line therapy, particularly in patients averse to subcutaneous or intravenous therapy. We do counsel all patients on the increased risk of infection, and we do recommend inactivated herpes zoster vaccination in previously unvaccinated patients planning to start JAKi therapy.

On the horizon are the development of novel, oral agents targeting tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which is a member of the JAK family of signaling proteins. In fact, the TYK2 inhibitor deucravacitinib was approved by the FDA in 2022 for the treatment of PsO. TYK2 inhibitors appear to have the advantage of a more selective mechanism of action, with fewer off-target effects. There were fewer adverse events in the deucravacitinib trials, which led to its prompt PsO authorization, and the FDA approval for the drug did not include the same black box warning that appears in the label for other JAKi.8 A phase 2 study showed early promise for the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib in PsA.9 Further investigation will be needed to better understand the role of deucravacitinib and other TYK2 inhibitors being developed for the treatment of PsA. In the meantime, JAKi continue to be a prominent consideration for first-line PsA therapy in a carefully selected patient population.

Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) are a novel class of oral, targeted small-molecule inhibitors that are increasingly used to treat several different autoimmune conditions. In terms of rheumatologic indications, the FDA first approved tofacitinib (TOF) for use in moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (RA) unresponsive to methotrexate therapy. Eleven years later, the indications for JAKi use have expanded to include ulcerative colitis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), among other diseases. As with any new therapeutic mechanism, there are questions as to how JAKi should be incorporated into the treatment paradigm of PsA. In this article, we briefly review the efficacy and safety data of these agents and discuss our approach to their use in PsA.

Two JAKi are currently FDA approved for the treatment of PsA: tofacitinib (TOF) and upadacitinib (UPA). Other JAKi, such as filgotinib and peficitinib, are only approved outside the United States and will not be discussed here.

TOF was originally studied in skin psoriasis (PsO) before 2 pivotal studies demonstrated efficacy in PsA. TOF or adalimumab (ADA) were compared with placebo in patients who had failed conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD).1 ACR20 response was superior with TOF 5 mg twice daily (BID) (50%) and 10 mg BID (61%) vs placebo (33%), and it was comparable to ADA (52%), which was used in this study as an active comparator. The overall rate of adverse events was similar with both doses of TOF when compared with ADA; however, patients taking TOF had numerically more cases of cancer, serious infection, and herpes zoster.

Another study evaluated TOF compared with placebo in patients with PsA who had an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapy.2 The study showed an ACR20 response of 50% in patients taking TOF 5 mg BID and 47% in patients taking 10 mg BID, compared with 24% in those taking placebo. Patients who received the 10 mg TOF dose continuously had higher rates of adverse events compared to TOF 5 mg, placebo, and patients who crossed over from placebo to TOF at either dose. In the TOF groups, there were cases of serious infection and herpes zoster, as well as 2 patients with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Following review of these data, the FDA approved only the 5 mg BID dose, and later an 11-mg daily extended-release formulation that was pharmacokinetically similar.

The efficacy for UPA in PsA was shown in 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. SELECT-PsA1 compared UPA at 2 doses, 15 mg and 30 mg daily, vs placebo and vs ADA in patients with biologic DMARD (bDMARD)-naïve PsA.3 This trial demonstrated superiority of UPA in the ACR20 response at both doses (71% and 79%, respectively) compared with placebo (36%). The 15-mg dose of UPA was comparable to ADA (65%), while the 30-mg dose achieved superiority compared to ADA. Secondary outcomes including skin activity, patient-reported symptoms, and inhibition of radiographic progression were also superior in UPA compared with placebo and similar or greater with UPA compared with ADA, depending on the specific outcome.4 SELECT-PsA2 compared UPA 15 mg, 30 mg, and placebo in patients with prior incomplete response or intolerance to a bDMARD.5 At week 12 of the study, patients taking UPA 15 mg and 30 mg had an ACR20 response of 57% and 64%, respectively, compared with placebo (24%). At week 24, minimal disease activity was achieved by 25% of patients taking UPA 15 mg and 29% of patients taking UPA 30 mg, which was superior to placebo (3%).

Both studies found a significant increase in infections, including serious infections, at the 30-mg UPA dose compared with the placebo and adalimumab groups. Cytopenia and elevated creatine kinase (CK) level also occurred more frequently in the UPA 30-mg group. Rates of cancer were low overall and comparable between the patients treated with UPA and ADA. Given the higher incidence of adverse events with the 30-mg dose and the relatively similar efficacy, the sponsor elected to submit only the lower dose to the FDA for approval.

In the last few years, concerns for safety with JAKi use grew after the publication of data from the ORAL SURVEILLANCE trial, an FDA-mandated, post-approval safety study of TOF in RA. In this trial, patients with active RA over 50 years of age and with at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor were randomized to TOF at 1 of 2 doses, 5 mg or 10 mg BID, or a TNFi.6 This trial was designed as a noninferiority study, and TOF did not meet the noninferiority threshold compared to TNFi, with hazard ratios of 1.33 and 1.48 for MACE and malignancy, respectively. The results of this trial prompted the FDA to add a black box warning to the label for all JAKi, pointing out the risk of malignancy and MACE, as well as infection, mortality, and thrombosis.

In the ORAL SURVEILLANCE trial, the increased risk of MACE and malignancy was primarily seen in the study patients with high risk for a cardiovascular event. To address the question of whether a similar risk profile exists when using JAKi to treat PsA, or whether this is a disease-specific process related to RA, a post hoc analysis of 3 PsA trials and 7 PsO trials of patients treated with TOF was conducted.7 The analysis found that patients with a history of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) or metabolic syndrome, or patients at high risk for ASCVD (score > 20%) had increased incidence rates of MACE compared with those with low risk scores for ASCVD. Interestingly, as in RA, increased incidence rates of malignancy were seen in patients with preexisting or at high risk for ASCVD.

While the FDA recommends JAKi use in patients who have failed or are inappropriate for treatment with a TNFi, we would consider the use of JAKi for first-line therapy in PsA on an individual basis. One advantage of JAKi is their efficacy across multiple PsA domains, including peripheral arthritis, axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and skin disease (although the approved dose of TOF was not statistically effective for PsO in the pivotal trials). Based on this efficacy, we believe that patients with overlapping, multifaceted disease may benefit the most from these medications. Patient risk factors and comorbidities are a prominent consideration in our use of JAKi to ensure safety, as the risk for MACE and malignancy is informed partly by baseline cardiovascular status. In younger patients without cardiovascular risk factors, JAKi may be a strong candidate for first-line therapy, particularly in patients averse to subcutaneous or intravenous therapy. We do counsel all patients on the increased risk of infection, and we do recommend inactivated herpes zoster vaccination in previously unvaccinated patients planning to start JAKi therapy.

On the horizon are the development of novel, oral agents targeting tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2), which is a member of the JAK family of signaling proteins. In fact, the TYK2 inhibitor deucravacitinib was approved by the FDA in 2022 for the treatment of PsO. TYK2 inhibitors appear to have the advantage of a more selective mechanism of action, with fewer off-target effects. There were fewer adverse events in the deucravacitinib trials, which led to its prompt PsO authorization, and the FDA approval for the drug did not include the same black box warning that appears in the label for other JAKi.8 A phase 2 study showed early promise for the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib in PsA.9 Further investigation will be needed to better understand the role of deucravacitinib and other TYK2 inhibitors being developed for the treatment of PsA. In the meantime, JAKi continue to be a prominent consideration for first-line PsA therapy in a carefully selected patient population.

Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1537-1550.

Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1525-1536.

McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1227-1239.

McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 2-year results from the phase 3 SELECT-PsA 1 study. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;10(1):275-292.

Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Anderson JK, et al. Upadacitinib for psoriatic arthritis refractory to biologics: SELECT-PsA 2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(3):312-320.

Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316-326.

Kristensen LE, Strober B, Poddubnyy D, et al. Association between baseline cardiovascular risk and incidence rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis receiving tofacitinib. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2023;15:1759720X221149965.

Dolgin E. TYK2-blocking agent showcases power of atypical kinase. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(12):1701-1704.

Mease PJ, Deodhar AA, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective TYK2 inhibitor, deucravacitinib, in a phase II trial in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(6):815-822.

Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1537-1550.

Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1525-1536.

McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1227-1239.

McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 2-year results from the phase 3 SELECT-PsA 1 study. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;10(1):275-292.

Mease PJ, Lertratanakul A, Anderson JK, et al. Upadacitinib for psoriatic arthritis refractory to biologics: SELECT-PsA 2. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(3):312-320.

Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316-326.

Kristensen LE, Strober B, Poddubnyy D, et al. Association between baseline cardiovascular risk and incidence rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and malignancies in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis receiving tofacitinib. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2023;15:1759720X221149965.

Dolgin E. TYK2-blocking agent showcases power of atypical kinase. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(12):1701-1704.

Mease PJ, Deodhar AA, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective TYK2 inhibitor, deucravacitinib, in a phase II trial in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(6):815-822.

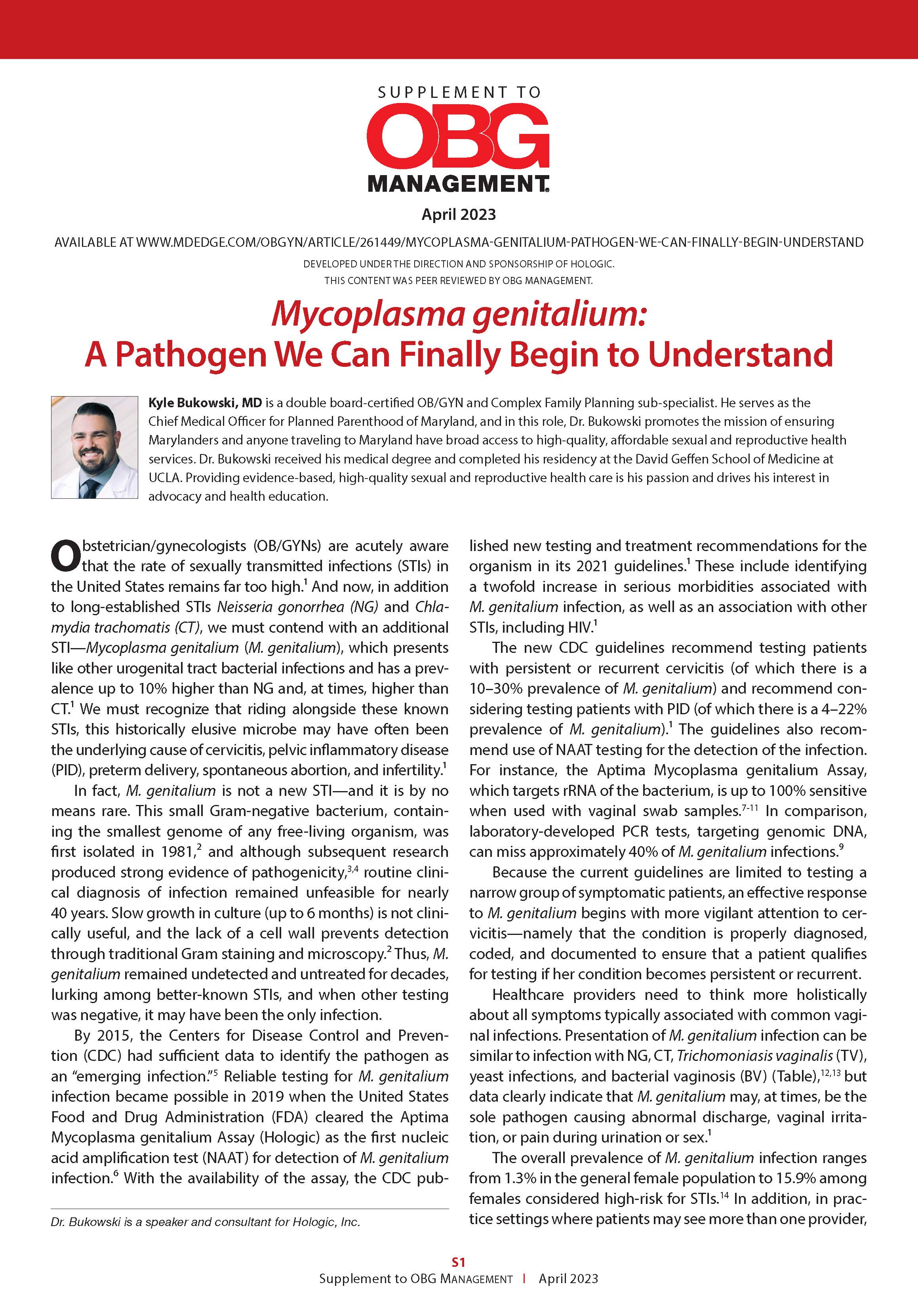

Mycoplasma genitalium: A Pathogen We Can Finally Begin to Understand

Riding alongside known STIs, this historically elusive microbe may have often been the underlying cause of a variety of symptoms. In this supplement to OBG Management Dr. Kyle Bukowski discusses how to meet the challenge presented by this not-so-new microbe while helping foster regular STI testing, and encourage patients to seek care when symptoms occur.

Riding alongside known STIs, this historically elusive microbe may have often been the underlying cause of a variety of symptoms. In this supplement to OBG Management Dr. Kyle Bukowski discusses how to meet the challenge presented by this not-so-new microbe while helping foster regular STI testing, and encourage patients to seek care when symptoms occur.

Riding alongside known STIs, this historically elusive microbe may have often been the underlying cause of a variety of symptoms. In this supplement to OBG Management Dr. Kyle Bukowski discusses how to meet the challenge presented by this not-so-new microbe while helping foster regular STI testing, and encourage patients to seek care when symptoms occur.

One Expert’s Approach in Transplant-Ineligible, Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma

1. The treatment of multiple myeloma has evolved significantly in recent years. What are some of the most important things you consider in the treatment of your newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients?

We’ve seen great progress in the treatment of multiple myeloma over the last decade, and outcomes continue to improve for many patients.1 Still, it is important to keep in mind that more than 34,000 patients will be diagnosed and more than 12,000 people will die from the disease this year.2 We may have the greatest opportunity to impact the course of disease in the treatment of newly diagnosed patients due to the nature of this cancer:

- Multiple myeloma is characterized by relapse, and we know the length of remission generally decreases with each relapse and subsequent line of therapy.3

- Patients often become refractory to treatment over time.

When I meet with a patient who has been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, the first thing I consider is their eligibility for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). In my opinion, the introduction of ASCT is one of the biggest advancements in the last few decades, and we’ve found that ASCT followed by maintenance therapy with targeted tools improves progression-free survival (PFS).4

Unfortunately, many newly diagnosed patients are not eligible for ASCT–either because of comorbidities or other complexities related to the presentation of their disease.

For patients who are transplant-ineligible (TIE), it is important to have treatment options that are proven effective in extending PFS and overall survival (OS), and capable of producing deep and durable responses.

2. What are the challenges associated with treating newly diagnosed patients who are not eligible for ASCT?

We still consider multiple myeloma to be an incurable disease but, in my opinion, the treatment of TIE patients is less challenging today than a decade ago due to the emergence of novel therapies. That said, TIE patients are typically older and present with more advanced disease and comorbidities, including diabetes or cardiovascular events.5

A retrospective analysis published in 2020 by Rafael Fonseca examined frontline treatment patterns and attrition rates by line of therapy among newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients who are TIE. More than 22,000 patients were identified from three patient-level databases between 2000 and 2018 - the OPTUM Commercial Claims database, the OPTUM Electronic Medical Records database, and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Meidcare Linked database. Patients included had to have a multiple myeloma diagnosis on or after January 1, 2007. Results showed that attrition rates among newly diagnosed, TIE patients with multiple myeloma increase with each line of therapy, with the proportion of patients who receive a second line of therapy decreasing by 50 percent with each subsequent line.3

3. Can you provide more detail on the goals of therapy for newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients?

When I discuss treatment goals with TIE patients, I feel it is important to emphasize managing side effects and achieving deep and durable responses. I have the benefit of being in an academic setting, where I regularly exchange information with my colleagues about what we’re learning from the clinical studies in which we participate. Choosing which treatment to administer is complex and involves other considerations. For example, if two regimens have comparable efficacy, I may recommend the regimen with a more established safety profile or more robust evidence so I can properly anticipate and manage toxicities in my patients. Overall survival is one of the most important endpoints I consider, in addition to depth of response and PFS. In recent years, we’ve seen increasing evidence pointing to the importance of using a proven effective treatment in frontline patients that are ineligible for transplant.

4. A key study in newly-diagnosed, transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma is the Phase 3 MAIA study. Can you share the key takeaways from this study and discuss how the results have shaped treatment for this patient population?

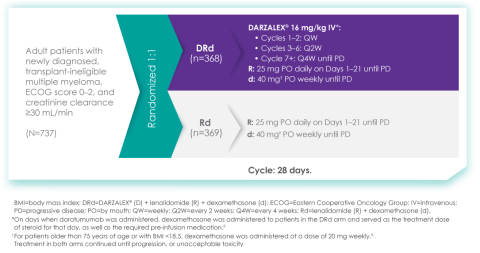

Of course. The MAIA study is a randomized Phase 3 study evaluating DARZALEX® (daratumumab) intravenous injection in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (D-Rd) compared with Rd in 737 adult patients with newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. The median age of patients participating in the MAIA study was 73 (range 45-90), an important consideration since the median age for multiple myeloma diagnosis is approximately 66-70 years of age.6 The study evaluated PFS as the primary endpoint, and overall survival as a key secondary endpoint, and supported the FDA approval of DARZALEX® in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for adult patients with newly diagnosed, multiple myeloma who are ineligible for ASCT.

MAIA study design7

The baseline demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the 2 treatment groups. Forty-four percent of the patients were ≥75 years of age. Fifty-two percent (52%) of patients were male, 92% White, 4% Black or African American, and 1% Asian. Three percent (3%) of patients reported an ethnicity of Hispanic or Latino. Thirty-four (34%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score of 0, 50% had an ECOG performance score of 1, and 17% had an ECOG performance score of ≥2. Twenty-seven percent had International Staging System (ISS) Stage I, 43% had ISS Stage II, and 29% had ISS Stage III disease.

Select Important Safety Information:

CONTRAINDICATIONS

DARZALEX® is contraindicated in patients with a history of severe hypersensitivity (eg, anaphylactic reactions) to daratumumab or any of the components of the formulation.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Infusion-Related Reactions: DARZALEX® can cause severe and/or serious infusion-related reactions including anaphylactic reactions.

These reactions can be life-threatening, and fatal outcomes have been reported. Please scroll down to read Important Safety Information for DARZALEX®.

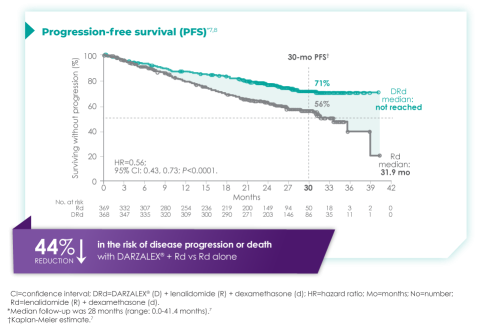

Primary findings from the study, which were published in 2019, showed an improvement in PFS in patients receiving D-Rd compared with those receiving Rd alone.7 The median PFS was not reached in the D-Rd arm and was reached at 31.9 months in the Rd arm (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.43-0.73; P<0.0001).7 At a median of 30 months of follow-up, the data showed the clinical benefit of D-Rd therapy, with a 44% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death in patients receiving D-Rd compared with Rd alone.7

Additionally, 70.6% of patients (95% CI, 65.0-75.4) had no progressive disease with D-Rd treatment at median 30 months of follow-up, compared with 55.6% (95% CI, 49.5-61.3) of patients in the Rd group.7

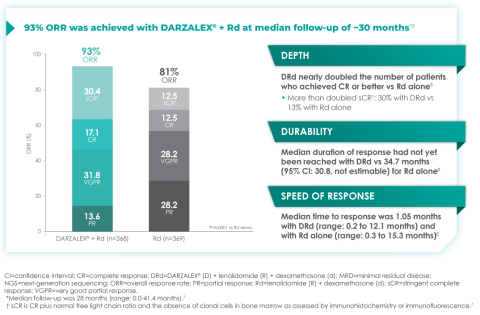

In terms of depth of response, the percentage of patients with a complete response or better was 47.6% in patients receiving D-Rd compared with 24.9% in the Rd group.7

Overall response rate with D-Rd in TIE NDMM at ~30 months of follow-up8

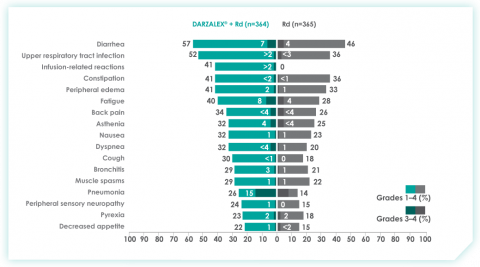

An overview of the most frequent adverse events at 30-months of follow-up are provided below. The most frequent adverse reactions were reported in ≥20% of patients, with at least a 5% greater frequency in the D-Rd arm compared with Rd alone.8

Most frequent adverse events at ~30 months of follow-up with D-Rd in TIE NDMM8

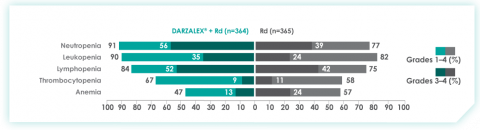

Most frequent hematologic laboratory abnormalities with D-Rd in TIE NDMM at ~30 months8

Serious adverse reactions with a 2% greater incidence in the D-Rd arm compared with the Rd arm were pneumonia (D-Rd 15% vs Rd 8%), bronchitis (D-Rd 4% vs Rd 2%), and dehydration (D-Rd 2% vs Rd <1).

• Discontinuation rates due to any adverse event: 7% with D-Rd vs 16% with Rd

• Infusion-related reactions (IRRs) with D-Rd occurred in 41% of patients; 2% were Grade 3 and <1% were Grade 4

• IRRs of any grade or severity may require management by interruption, modification, and/or discontinuation of the infusion

• Most IRRs occurred during first infusion

5. Thanks for that overview. In addition to these results, The Lancet Oncology has published updated overall survival data from a 5-year follow-up on the MAIA study. Can you provide an overview of these data and insights on their potential for patients?

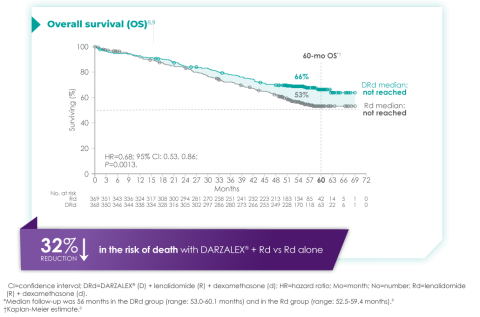

The MAIA trial was an important study, and for me, the results were practice changing. We see that after a median of nearly 5 years of follow-up, D-Rd significantly improved OS in TIE NDMM patients who were treated to progression compared with Rd alone (66.3% vs. 53.1% [HR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.86; P=0.0013]).9 This equates to approximately a 32% reduction in death when DARZALEX® was added to a two-drug regimen, which is a meaningful consideration when selecting the most appropriate regimens for my newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients.9

Overall survival data at ~5 years with D-Rd compared to Rd alone in TIE NDMM9

Importantly, efficacy that resulted from longer treatment with D-Rd is also supported by approximately 5 years of safety evaluation. Below is information from a follow-up analysis of the MAIA study. This information is not included in the current Prescribing Information and has not been evaluated by the FDA. Treatment-emergent adverse events are reported as observed. These analyses have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons and no conclusions should be drawn. In what I’ve observed through published data and in my practice, longer treatment has not revealed new safety signals.

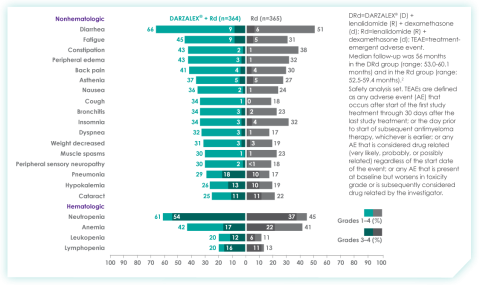

Most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events (any grade reported in ≥30% of patients and/or Grade 3/4 reported in ≥10% of patients) at ~5 years9

Select Important Safety Information:

DARZALEX® can cause severe and/or serious infusion-related reactions including anaphylactic reactions. These reactions can be life threatening, and fatal outcomes have been reported. In clinical trials (monotherapy and combination: N=2066), infusion-related reactions occurred in 37% of patients with the Week 1 (16 mg/kg) infusion, 2% with the Week 2 infusion, and cumulatively 6% with subsequent infusions. Less than 1% of patients had a Grade 3/4 infusion-related reaction at Week 2 or subsequent infusions. The median time to onset was 1.5 hours (range: 0 to 73 hours). Nearly all reactions occurred during infusion or within 4 hours of completing DARZALEX®. Severe reactions have occurred, including bronchospasm, hypoxia, dyspnea, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, and ocular adverse reactions, including choroidal effusion, acute myopia, and acute angle closure glaucoma. Signs and symptoms may include respiratory symptoms, such as nasal congestion, cough, throat irritation, as well as chills, vomiting, and nausea. Less common signs and symptoms were wheezing, allergic rhinitis, pyrexia, chest discomfort, pruritus, hypotension and blurred vision. Please scroll down to see Important Safety Information for DARZALEX®.

6. Does the availability of OS data influence your decisions on treatment selection in TIE NDMM?

Overall survival absolutely remains the gold standard and informs my practice. Prior to OS data being available, I will often look at other efficacy endpoints that are available sooner. In MAIA, I was encouraged by efficacy endpoints in earlier data, which were later confirmed by the latest data on OS.

7. The MAIA study shows that treating to disease progression or unacceptable toxicity is important. How does that impact your approach to treatment?

It's important to keep in mind that the MAIA trial was designed to evaluate treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity. The results revealed a significant difference between the DR-d and Rd treatment arms, but results observed in this study are contingent on this treatment approach. From a clinical perspective, unless there is considerable toxicity, I advocate for treating with D-Rd to progression.

In the clinic, we also see that TIE patients who have higher frailty scores are more likely to discontinue treatment prior to progression.10 There can be other reasons too – such as a patient simply wanting to have a break from treatment. These conversations are not always easy, but it is important to have an honest dialogue with patients.

8. What can we learn from studies like the MAIA trial that included a wide range of patient populations including patients who are elderly, frail, or had high cytogenetic risk?

Several patient subgroups were analyzed as part of the MAIA study. It is important to note that these subgroup analyses are not included in the Prescribing Information for DARZALEX®. These analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, and there are insufficient numbers of patients per subgroup to make definitive conclusions of efficacy among the subgroups.

As mentioned above, the MAIA study evaluated a wide range of patients (n=737). The baseline demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the D-Rd and Rd treatment groups and the median age was 73 (range: 45-90) years, with 44% of the patients ≥75 years of age.

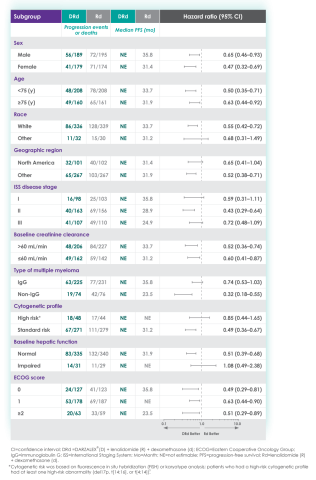

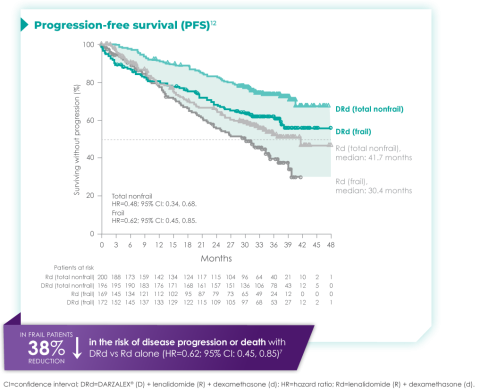

In the various patient subgroups that were analyzed as part of the MAIA study, it was found that at ~3-years of follow-up the PFS numerically favored DRd compared with Rd alone in most subgroups (see table below).

Median progression-free survival by sub-population at ~3 year follow-up8

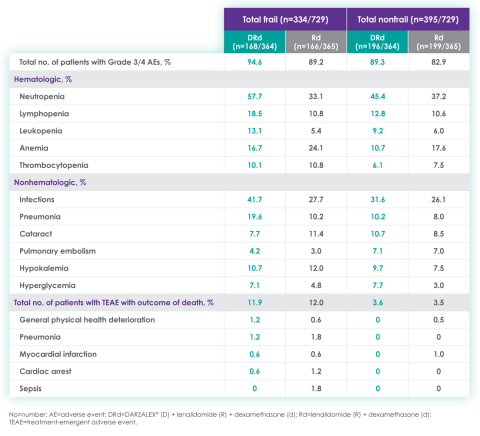

The MAIA trial also included patients who were frail and a post hoc analysis was conducted in this subgroup of patients. These analyses are not included in the Prescribing Information for DARZALEX®. These analyses were conducted post hoc and there are insufficient numbers of patients per subgroup to make definitive conclusions of efficacy among the subgroups.

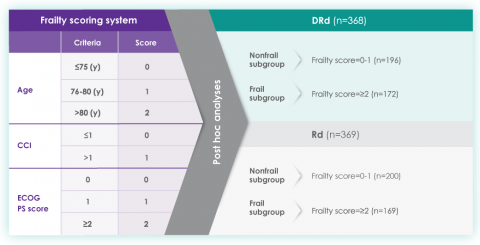

A frailty assessment was performed retrospectively using age, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) – which is calculated based on a retrospective review of the patient’s medical history to predict the 10-year mortality – and the baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score, used to measure a patient’s level of functioning in terms of their ability to care for themselves, daily activity, and physical activity. The frailty scores were then added up to classify patients into fit (0), intermediate (1), or frail (≥2). Frailty status was further simplified into 2 categories: non-frail (0-1) and frail (≥2). The median age in the frail subgroup was 77 years (range: 57-80 years), with 88% of patients having ECOG performance score ≥1. CCI was calculated based on retrospective review of each patient’s medical history.12

The charts below illustrate the frailty scoring system with an overview of the patient population included in the 3-year post hoc analysis, PFS rate, and adverse events.

MAIA post hoc subgroup analysis by frailty status score12

The retrospective assessment of frailty score was a limitation of this study. Retrospective CCI calculations were based on reported medical history, which may contain missing data and result in underestimating or overestimating the number of patients in each frailty subgroup. The ECOG PS score parameter used for frailty score calculations in the study is more subjective, with susceptibility to intra- and inter-observer bias, compared with the ADL (activities of daily living) and IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) scales used in the IMWG scoring system. While the frailty scale used in the study is based on parameters that are routinely assessed in clinical practice for clinical use, the use of comprehensive frailty assessments that more accurately reflect biological or functional frailty will remain important for the further optimization of treatment strategies for frail patients. Patients with an ECOG PS score ≥3 and patients with comorbidities that may interfere with the study procedures were excluded from MAIA; the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study limits the generalizability of these results to more frail patients seen in clinical practice.

Progression-free survival in a ~3-year subgroup analysis of frail patients following treatment with D-Rd in TIE NDMM12

Most frequent Grade 3/4 treatment-emergent adverse events (≥10%) in frail patients at ~3 year follow-up of MAIA trial12

Please see additional Important Safety Information for DARZALEX® below.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

CONTRAINDICATIONS

DARZALEX® is contraindicated in patients with a history of severe hypersensitivity (eg, anaphylactic reactions) to daratumumab or any of the components of the formulation.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Infusion-Related Reactions

DARZALEX® can cause severe and/or serious infusion-related reactions including anaphylactic reactions. These reactions can be life‑threatening, and fatal outcomes have been reported. In clinical trials (monotherapy and combination: N=2066), infusion-related reactions occurred in 37% of patients with the Week 1 (16 mg/kg) infusion, 2% with the Week 2 infusion, and cumulatively 6% with subsequent infusions. Less than 1% of patients had a Grade 3/4 infusion-related reaction at Week 2 or subsequent infusions. The median time to onset was 1.5 hours (range: 0 to 73 hours). Nearly all reactions occurred during infusion or within 4 hours of completing DARZALEX®. Severe reactions have occurred, including bronchospasm, hypoxia, dyspnea, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, and ocular adverse reactions, including choroidal effusion, acute myopia, and acute angle closure glaucoma. Signs and symptoms may include respiratory symptoms, such as nasal congestion, cough, throat irritation, as well as chills, vomiting, and nausea. Less common signs and symptoms were wheezing, allergic rhinitis, pyrexia, chest discomfort, pruritus, hypotension and blurred vision.

When DARZALEX® dosing was interrupted in the setting of ASCT (CASSIOPEIA) for a median of 3.75 months (range: 2.4 to 6.9 months), upon re-initiation of DARZALEX®, the incidence of infusion-related reactions was 11% for the first infusion following ASCT. Infusion-related reactions occurring at re-initiation of DARZALEX® following ASCT were consistent in terms of symptoms and severity (Grade 3 or 4: <1%) with those reported in previous studies at Week 2 or subsequent infusions. In EQUULEUS, patients receiving combination treatment (n=97) were administered the first 16 mg/kg dose at Week 1 split over two days, ie, 8 mg/kg on Day 1 and Day 2, respectively. The incidence of any grade infusion-related reactions was 42%, with 36% of patients experiencing infusion-related reactions on Day 1 of Week 1, 4% on Day 2 of Week 1, and 8% with subsequent infusions.

Pre-medicate patients with antihistamines, antipyretics, and corticosteroids. Frequently monitor patients during the entire infusion. Interrupt DARZALEX® infusion for reactions of any severity and institute medical management as needed. Permanently discontinue DARZALEX® therapy if an anaphylactic reaction or life-threatening (Grade 4) reaction occurs and institute appropriate emergency care. For patients with Grade 1, 2, or 3 reactions, reduce the infusion rate when re-starting the infusion.

To reduce the risk of delayed infusion-related reactions, administer oral corticosteroids to all patients following DARZALEX® infusions. Patients with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may require additional post-infusion medications to manage respiratory complications. Consider prescribing short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Ocular adverse reactions, including acute myopia and narrowing of the anterior chamber angle due to ciliochoroidal effusions with potential for increased intraocular pressure or glaucoma, have occurred with DARZALEX infusion. If ocular symptoms occur, interrupt DARZALEX infusion and seek immediate ophthalmologic evaluation prior to restarting DARZALEX.

Interference With Serological Testing

Daratumumab binds to CD38 on red blood cells (RBCs) and results in a positive indirect antiglobulin test (indirect Coombs test). Daratumumab-mediated positive indirect antiglobulin test may persist for up to 6 months after the last daratumumab infusion. Daratumumab bound to RBCs masks detection of antibodies to minor antigens in the patient’s serum. The determination of a patient’s ABO and Rh blood type is not impacted. Notify blood transfusion centers of this interference with serological testing and inform blood banks that a patient has received DARZALEX®. Type and screen patients prior to starting DARZALEX®.

Neutropenia and Thrombocytopenia

DARZALEX® may increase neutropenia and thrombocytopenia induced by background therapy. Monitor complete blood cell counts periodically during treatment according to manufacturer’s prescribing information for background therapies. Monitor patients with neutropenia for signs of infection. Consider withholding DARZALEX® until recovery of neutrophils or for recovery of platelets.

Interference With Determination of Complete Response

Daratumumab is a human immunoglobulin G (IgG) kappa monoclonal antibody that can be detected on both the serum protein electrophoresis (SPE) and immunofixation (IFE) assays used for the clinical monitoring of endogenous M-protein. This interference can impact the determination of complete response and of disease progression in some patients with IgG kappa myeloma protein.

Embryo-Fetal Toxicity

Based on the mechanism of action, DARZALEX® can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. DARZALEX® may cause depletion of fetal immune cells and decreased bone density. Advise pregnant women of the potential risk to a fetus. Advise females with reproductive potential to use effective contraception during treatment with DARZALEX® and for 3 months after the last dose.

The combination of DARZALEX® with lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide is contraindicated in pregnant women because lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and thalidomide may cause birth defects and death of the unborn child. Refer to the lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide prescribing information on use during pregnancy.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most frequently reported adverse reactions (incidence ≥20%) were: upper respiratory infection, neutropenia, infusion‑related reactions, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, constipation, anemia, peripheral sensory neuropathy, fatigue, peripheral edema, nausea, cough, pyrexia, dyspnea, and asthenia. The most common hematologic laboratory abnormalities (≥40%) with DARZALEX® are: neutropenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and anemia.

INDICATIONS

DARZALEX® (daratumumab) is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with multiple myeloma:

- In combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in newly diagnosed patients who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant and in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who have received at least one prior therapy

- In combination with bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone in newly diagnosed patients who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplant

- In combination with bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone in newly diagnosed patients who are eligible for autologous stem cell transplant

- In combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients who have received at least one prior therapy

- In combination with carfilzomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who have received one to three prior lines of therapy

- In combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone in patients who have received at least two prior therapies including lenalidomide and a proteasome inhibitor

- As monotherapy in patients who have received at least three prior lines of therapy including a proteasome inhibitor (PI) and an immunomodulatory agent or who are double-refractory to a PI and an immunomodulatory agent

Please click here to see the full Prescribing Information.

1. Richardson PG, San Miguel JF, Moreau P, et al. Interpreting clinical trial data in multiple myeloma: translating findings to the real-world setting. Blood Cancer J. 2018;8(11). doi:10.1038/s41408-018-0141-0

2. Key Statistics About Multiple Myeloma. Cancer.org. Published 2019. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/multiple-myeloma/about/key-statistics.html

3. Fonseca R, Usmani SZ, Mehra M, et al. Frontline treatment patterns and attrition rates by subsequent lines of therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1). doi:10.1186/s12885-020-07503-y

4. Devarakonda S, Efebera Y, Sharma N. Role of Stem Cell Transplantation in Multiple Myeloma. Cancers. 2021;13(4):863. doi:10.3390/cancers13040863

5. Derudas D, Capraro F, Martinelli G, Cerchione C. How I manage frontline transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. Hematol Rep. 2020;12(s1). doi:10.4081/hr.2020.8956

6. Kazandjian D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin Oncl. 2016;43(6):676-681. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.11.004

7. Facon T, Kumar S, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for untreated myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380(22):2104-2115. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1817249

8. DARZALEX® [Prescribing Information]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc.

9. Facon T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, et al. Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(11):1582-1596. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00466-6

10. Facon T, Dimopoulos MA, Meuleman N, et al. A simplified frailty scale predicts outcomes in transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma treated in the FIRST (MM-020) trial. Leukemia. 2019;34(1):224-233. doi:10.1038/s41375-019-0539-0

11. Facon T, Kumar SK, Plesner T, et al. Supplement to: Daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MAIA): overall survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(11):1582-1596.

12. Facon T, Cook G, Usmani SZ, et al. Daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in transplant-ineligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: frailty subgroup analysis of MAIA. Leukemia. 2022;36(4):1066-1077. doi:10.1038/s41375-021-01488-8

© Janssen Biotech, Inc. 2022 All rights reserved. 12/22 cp-333446v1

1. The treatment of multiple myeloma has evolved significantly in recent years. What are some of the most important things you consider in the treatment of your newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients?

We’ve seen great progress in the treatment of multiple myeloma over the last decade, and outcomes continue to improve for many patients.1 Still, it is important to keep in mind that more than 34,000 patients will be diagnosed and more than 12,000 people will die from the disease this year.2 We may have the greatest opportunity to impact the course of disease in the treatment of newly diagnosed patients due to the nature of this cancer:

- Multiple myeloma is characterized by relapse, and we know the length of remission generally decreases with each relapse and subsequent line of therapy.3

- Patients often become refractory to treatment over time.

When I meet with a patient who has been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, the first thing I consider is their eligibility for autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT). In my opinion, the introduction of ASCT is one of the biggest advancements in the last few decades, and we’ve found that ASCT followed by maintenance therapy with targeted tools improves progression-free survival (PFS).4

Unfortunately, many newly diagnosed patients are not eligible for ASCT–either because of comorbidities or other complexities related to the presentation of their disease.

For patients who are transplant-ineligible (TIE), it is important to have treatment options that are proven effective in extending PFS and overall survival (OS), and capable of producing deep and durable responses.

2. What are the challenges associated with treating newly diagnosed patients who are not eligible for ASCT?

We still consider multiple myeloma to be an incurable disease but, in my opinion, the treatment of TIE patients is less challenging today than a decade ago due to the emergence of novel therapies. That said, TIE patients are typically older and present with more advanced disease and comorbidities, including diabetes or cardiovascular events.5

A retrospective analysis published in 2020 by Rafael Fonseca examined frontline treatment patterns and attrition rates by line of therapy among newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) patients who are TIE. More than 22,000 patients were identified from three patient-level databases between 2000 and 2018 - the OPTUM Commercial Claims database, the OPTUM Electronic Medical Records database, and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Meidcare Linked database. Patients included had to have a multiple myeloma diagnosis on or after January 1, 2007. Results showed that attrition rates among newly diagnosed, TIE patients with multiple myeloma increase with each line of therapy, with the proportion of patients who receive a second line of therapy decreasing by 50 percent with each subsequent line.3

3. Can you provide more detail on the goals of therapy for newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients?

When I discuss treatment goals with TIE patients, I feel it is important to emphasize managing side effects and achieving deep and durable responses. I have the benefit of being in an academic setting, where I regularly exchange information with my colleagues about what we’re learning from the clinical studies in which we participate. Choosing which treatment to administer is complex and involves other considerations. For example, if two regimens have comparable efficacy, I may recommend the regimen with a more established safety profile or more robust evidence so I can properly anticipate and manage toxicities in my patients. Overall survival is one of the most important endpoints I consider, in addition to depth of response and PFS. In recent years, we’ve seen increasing evidence pointing to the importance of using a proven effective treatment in frontline patients that are ineligible for transplant.

4. A key study in newly-diagnosed, transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma is the Phase 3 MAIA study. Can you share the key takeaways from this study and discuss how the results have shaped treatment for this patient population?

Of course. The MAIA study is a randomized Phase 3 study evaluating DARZALEX® (daratumumab) intravenous injection in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (D-Rd) compared with Rd in 737 adult patients with newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible multiple myeloma. The median age of patients participating in the MAIA study was 73 (range 45-90), an important consideration since the median age for multiple myeloma diagnosis is approximately 66-70 years of age.6 The study evaluated PFS as the primary endpoint, and overall survival as a key secondary endpoint, and supported the FDA approval of DARZALEX® in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for adult patients with newly diagnosed, multiple myeloma who are ineligible for ASCT.

MAIA study design7

The baseline demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the 2 treatment groups. Forty-four percent of the patients were ≥75 years of age. Fifty-two percent (52%) of patients were male, 92% White, 4% Black or African American, and 1% Asian. Three percent (3%) of patients reported an ethnicity of Hispanic or Latino. Thirty-four (34%) had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance score of 0, 50% had an ECOG performance score of 1, and 17% had an ECOG performance score of ≥2. Twenty-seven percent had International Staging System (ISS) Stage I, 43% had ISS Stage II, and 29% had ISS Stage III disease.

Select Important Safety Information:

CONTRAINDICATIONS

DARZALEX® is contraindicated in patients with a history of severe hypersensitivity (eg, anaphylactic reactions) to daratumumab or any of the components of the formulation.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Infusion-Related Reactions: DARZALEX® can cause severe and/or serious infusion-related reactions including anaphylactic reactions.

These reactions can be life-threatening, and fatal outcomes have been reported. Please scroll down to read Important Safety Information for DARZALEX®.

Primary findings from the study, which were published in 2019, showed an improvement in PFS in patients receiving D-Rd compared with those receiving Rd alone.7 The median PFS was not reached in the D-Rd arm and was reached at 31.9 months in the Rd arm (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.43-0.73; P<0.0001).7 At a median of 30 months of follow-up, the data showed the clinical benefit of D-Rd therapy, with a 44% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death in patients receiving D-Rd compared with Rd alone.7

Additionally, 70.6% of patients (95% CI, 65.0-75.4) had no progressive disease with D-Rd treatment at median 30 months of follow-up, compared with 55.6% (95% CI, 49.5-61.3) of patients in the Rd group.7

In terms of depth of response, the percentage of patients with a complete response or better was 47.6% in patients receiving D-Rd compared with 24.9% in the Rd group.7

Overall response rate with D-Rd in TIE NDMM at ~30 months of follow-up8

An overview of the most frequent adverse events at 30-months of follow-up are provided below. The most frequent adverse reactions were reported in ≥20% of patients, with at least a 5% greater frequency in the D-Rd arm compared with Rd alone.8

Most frequent adverse events at ~30 months of follow-up with D-Rd in TIE NDMM8

Most frequent hematologic laboratory abnormalities with D-Rd in TIE NDMM at ~30 months8

Serious adverse reactions with a 2% greater incidence in the D-Rd arm compared with the Rd arm were pneumonia (D-Rd 15% vs Rd 8%), bronchitis (D-Rd 4% vs Rd 2%), and dehydration (D-Rd 2% vs Rd <1).

• Discontinuation rates due to any adverse event: 7% with D-Rd vs 16% with Rd

• Infusion-related reactions (IRRs) with D-Rd occurred in 41% of patients; 2% were Grade 3 and <1% were Grade 4

• IRRs of any grade or severity may require management by interruption, modification, and/or discontinuation of the infusion

• Most IRRs occurred during first infusion

5. Thanks for that overview. In addition to these results, The Lancet Oncology has published updated overall survival data from a 5-year follow-up on the MAIA study. Can you provide an overview of these data and insights on their potential for patients?

The MAIA trial was an important study, and for me, the results were practice changing. We see that after a median of nearly 5 years of follow-up, D-Rd significantly improved OS in TIE NDMM patients who were treated to progression compared with Rd alone (66.3% vs. 53.1% [HR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.53-0.86; P=0.0013]).9 This equates to approximately a 32% reduction in death when DARZALEX® was added to a two-drug regimen, which is a meaningful consideration when selecting the most appropriate regimens for my newly diagnosed, transplant-ineligible patients.9

Overall survival data at ~5 years with D-Rd compared to Rd alone in TIE NDMM9

Importantly, efficacy that resulted from longer treatment with D-Rd is also supported by approximately 5 years of safety evaluation. Below is information from a follow-up analysis of the MAIA study. This information is not included in the current Prescribing Information and has not been evaluated by the FDA. Treatment-emergent adverse events are reported as observed. These analyses have not been adjusted for multiple comparisons and no conclusions should be drawn. In what I’ve observed through published data and in my practice, longer treatment has not revealed new safety signals.

Most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events (any grade reported in ≥30% of patients and/or Grade 3/4 reported in ≥10% of patients) at ~5 years9

Select Important Safety Information:

DARZALEX® can cause severe and/or serious infusion-related reactions including anaphylactic reactions. These reactions can be life threatening, and fatal outcomes have been reported. In clinical trials (monotherapy and combination: N=2066), infusion-related reactions occurred in 37% of patients with the Week 1 (16 mg/kg) infusion, 2% with the Week 2 infusion, and cumulatively 6% with subsequent infusions. Less than 1% of patients had a Grade 3/4 infusion-related reaction at Week 2 or subsequent infusions. The median time to onset was 1.5 hours (range: 0 to 73 hours). Nearly all reactions occurred during infusion or within 4 hours of completing DARZALEX®. Severe reactions have occurred, including bronchospasm, hypoxia, dyspnea, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, and ocular adverse reactions, including choroidal effusion, acute myopia, and acute angle closure glaucoma. Signs and symptoms may include respiratory symptoms, such as nasal congestion, cough, throat irritation, as well as chills, vomiting, and nausea. Less common signs and symptoms were wheezing, allergic rhinitis, pyrexia, chest discomfort, pruritus, hypotension and blurred vision. Please scroll down to see Important Safety Information for DARZALEX®.

6. Does the availability of OS data influence your decisions on treatment selection in TIE NDMM?

Overall survival absolutely remains the gold standard and informs my practice. Prior to OS data being available, I will often look at other efficacy endpoints that are available sooner. In MAIA, I was encouraged by efficacy endpoints in earlier data, which were later confirmed by the latest data on OS.

7. The MAIA study shows that treating to disease progression or unacceptable toxicity is important. How does that impact your approach to treatment?

It's important to keep in mind that the MAIA trial was designed to evaluate treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity. The results revealed a significant difference between the DR-d and Rd treatment arms, but results observed in this study are contingent on this treatment approach. From a clinical perspective, unless there is considerable toxicity, I advocate for treating with D-Rd to progression.

In the clinic, we also see that TIE patients who have higher frailty scores are more likely to discontinue treatment prior to progression.10 There can be other reasons too – such as a patient simply wanting to have a break from treatment. These conversations are not always easy, but it is important to have an honest dialogue with patients.

8. What can we learn from studies like the MAIA trial that included a wide range of patient populations including patients who are elderly, frail, or had high cytogenetic risk?

Several patient subgroups were analyzed as part of the MAIA study. It is important to note that these subgroup analyses are not included in the Prescribing Information for DARZALEX®. These analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, and there are insufficient numbers of patients per subgroup to make definitive conclusions of efficacy among the subgroups.

As mentioned above, the MAIA study evaluated a wide range of patients (n=737). The baseline demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the D-Rd and Rd treatment groups and the median age was 73 (range: 45-90) years, with 44% of the patients ≥75 years of age.

In the various patient subgroups that were analyzed as part of the MAIA study, it was found that at ~3-years of follow-up the PFS numerically favored DRd compared with Rd alone in most subgroups (see table below).

Median progression-free survival by sub-population at ~3 year follow-up8

The MAIA trial also included patients who were frail and a post hoc analysis was conducted in this subgroup of patients. These analyses are not included in the Prescribing Information for DARZALEX®. These analyses were conducted post hoc and there are insufficient numbers of patients per subgroup to make definitive conclusions of efficacy among the subgroups.

A frailty assessment was performed retrospectively using age, the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) – which is calculated based on a retrospective review of the patient’s medical history to predict the 10-year mortality – and the baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score, used to measure a patient’s level of functioning in terms of their ability to care for themselves, daily activity, and physical activity. The frailty scores were then added up to classify patients into fit (0), intermediate (1), or frail (≥2). Frailty status was further simplified into 2 categories: non-frail (0-1) and frail (≥2). The median age in the frail subgroup was 77 years (range: 57-80 years), with 88% of patients having ECOG performance score ≥1. CCI was calculated based on retrospective review of each patient’s medical history.12

The charts below illustrate the frailty scoring system with an overview of the patient population included in the 3-year post hoc analysis, PFS rate, and adverse events.

MAIA post hoc subgroup analysis by frailty status score12

The retrospective assessment of frailty score was a limitation of this study. Retrospective CCI calculations were based on reported medical history, which may contain missing data and result in underestimating or overestimating the number of patients in each frailty subgroup. The ECOG PS score parameter used for frailty score calculations in the study is more subjective, with susceptibility to intra- and inter-observer bias, compared with the ADL (activities of daily living) and IADL (instrumental activities of daily living) scales used in the IMWG scoring system. While the frailty scale used in the study is based on parameters that are routinely assessed in clinical practice for clinical use, the use of comprehensive frailty assessments that more accurately reflect biological or functional frailty will remain important for the further optimization of treatment strategies for frail patients. Patients with an ECOG PS score ≥3 and patients with comorbidities that may interfere with the study procedures were excluded from MAIA; the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study limits the generalizability of these results to more frail patients seen in clinical practice.

Progression-free survival in a ~3-year subgroup analysis of frail patients following treatment with D-Rd in TIE NDMM12

Most frequent Grade 3/4 treatment-emergent adverse events (≥10%) in frail patients at ~3 year follow-up of MAIA trial12

Please see additional Important Safety Information for DARZALEX® below.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

CONTRAINDICATIONS

DARZALEX® is contraindicated in patients with a history of severe hypersensitivity (eg, anaphylactic reactions) to daratumumab or any of the components of the formulation.

WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

Infusion-Related Reactions

DARZALEX® can cause severe and/or serious infusion-related reactions including anaphylactic reactions. These reactions can be life‑threatening, and fatal outcomes have been reported. In clinical trials (monotherapy and combination: N=2066), infusion-related reactions occurred in 37% of patients with the Week 1 (16 mg/kg) infusion, 2% with the Week 2 infusion, and cumulatively 6% with subsequent infusions. Less than 1% of patients had a Grade 3/4 infusion-related reaction at Week 2 or subsequent infusions. The median time to onset was 1.5 hours (range: 0 to 73 hours). Nearly all reactions occurred during infusion or within 4 hours of completing DARZALEX®. Severe reactions have occurred, including bronchospasm, hypoxia, dyspnea, hypertension, tachycardia, headache, laryngeal edema, pulmonary edema, and ocular adverse reactions, including choroidal effusion, acute myopia, and acute angle closure glaucoma. Signs and symptoms may include respiratory symptoms, such as nasal congestion, cough, throat irritation, as well as chills, vomiting, and nausea. Less common signs and symptoms were wheezing, allergic rhinitis, pyrexia, chest discomfort, pruritus, hypotension and blurred vision.

When DARZALEX® dosing was interrupted in the setting of ASCT (CASSIOPEIA) for a median of 3.75 months (range: 2.4 to 6.9 months), upon re-initiation of DARZALEX®, the incidence of infusion-related reactions was 11% for the first infusion following ASCT. Infusion-related reactions occurring at re-initiation of DARZALEX® following ASCT were consistent in terms of symptoms and severity (Grade 3 or 4: <1%) with those reported in previous studies at Week 2 or subsequent infusions. In EQUULEUS, patients receiving combination treatment (n=97) were administered the first 16 mg/kg dose at Week 1 split over two days, ie, 8 mg/kg on Day 1 and Day 2, respectively. The incidence of any grade infusion-related reactions was 42%, with 36% of patients experiencing infusion-related reactions on Day 1 of Week 1, 4% on Day 2 of Week 1, and 8% with subsequent infusions.

Pre-medicate patients with antihistamines, antipyretics, and corticosteroids. Frequently monitor patients during the entire infusion. Interrupt DARZALEX® infusion for reactions of any severity and institute medical management as needed. Permanently discontinue DARZALEX® therapy if an anaphylactic reaction or life-threatening (Grade 4) reaction occurs and institute appropriate emergency care. For patients with Grade 1, 2, or 3 reactions, reduce the infusion rate when re-starting the infusion.

To reduce the risk of delayed infusion-related reactions, administer oral corticosteroids to all patients following DARZALEX® infusions. Patients with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may require additional post-infusion medications to manage respiratory complications. Consider prescribing short- and long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Ocular adverse reactions, including acute myopia and narrowing of the anterior chamber angle due to ciliochoroidal effusions with potential for increased intraocular pressure or glaucoma, have occurred with DARZALEX infusion. If ocular symptoms occur, interrupt DARZALEX infusion and seek immediate ophthalmologic evaluation prior to restarting DARZALEX.

Interference With Serological Testing

Daratumumab binds to CD38 on red blood cells (RBCs) and results in a positive indirect antiglobulin test (indirect Coombs test). Daratumumab-mediated positive indirect antiglobulin test may persist for up to 6 months after the last daratumumab infusion. Daratumumab bound to RBCs masks detection of antibodies to minor antigens in the patient’s serum. The determination of a patient’s ABO and Rh blood type is not impacted. Notify blood transfusion centers of this interference with serological testing and inform blood banks that a patient has received DARZALEX®. Type and screen patients prior to starting DARZALEX®.

Neutropenia and Thrombocytopenia

DARZALEX® may increase neutropenia and thrombocytopenia induced by background therapy. Monitor complete blood cell counts periodically during treatment according to manufacturer’s prescribing information for background therapies. Monitor patients with neutropenia for signs of infection. Consider withholding DARZALEX® until recovery of neutrophils or for recovery of platelets.

Interference With Determination of Complete Response

Daratumumab is a human immunoglobulin G (IgG) kappa monoclonal antibody that can be detected on both the serum protein electrophoresis (SPE) and immunofixation (IFE) assays used for the clinical monitoring of endogenous M-protein. This interference can impact the determination of complete response and of disease progression in some patients with IgG kappa myeloma protein.

Embryo-Fetal Toxicity

Based on the mechanism of action, DARZALEX® can cause fetal harm when administered to a pregnant woman. DARZALEX® may cause depletion of fetal immune cells and decreased bone density. Advise pregnant women of the potential risk to a fetus. Advise females with reproductive potential to use effective contraception during treatment with DARZALEX® and for 3 months after the last dose.

The combination of DARZALEX® with lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide is contraindicated in pregnant women because lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and thalidomide may cause birth defects and death of the unborn child. Refer to the lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide prescribing information on use during pregnancy.

ADVERSE REACTIONS

The most frequently reported adverse reactions (incidence ≥20%) were: upper respiratory infection, neutropenia, infusion‑related reactions, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, constipation, anemia, peripheral sensory neuropathy, fatigue, peripheral edema, nausea, cough, pyrexia, dyspnea, and asthenia. The most common hematologic laboratory abnormalities (≥40%) with DARZALEX® are: neutropenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and anemia.

INDICATIONS

DARZALEX® (daratumumab) is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with multiple myeloma: