User login

Climate Change May Bring More Skin Disease

LAS VEGAS - Some of the effects of climate change are beginning to appear in dermatologists' offices, and there may be more to come.

Expanded geographic ranges of tick and parasite vectors due to climate change already are pushing infectious diseases into unfamiliar territory, Dr. Sigfrid A. Muller said at a dermatology seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

Lyme disease has spread well into Canada, and leishmaniasis is moving north from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Reports of Chagas disease are increasing in the United States and Central and South America. Peru and Ecuador are seeing more Carrion’s disease, he said.

Extreme heat, drought, and wide-scale fires, storms, and flooding, as well as other manifestations of climate change, will alter the incidence and severity of allergies, atopic dermatitis, and asthma, added Dr. Muller, a dermatologist in Las Vegas and chair of the International Society of Dermatology's Climate Change Task Force. The society, in 2009, declared climate change to be the defining dermatologic issue of the 21st century.

Global warming may be debated in the popular media, but there is little controversy about it in the scientific literature, he said. June 2010 was the warmest month on record (combining global land and ocean average surface temperatures) and the 304th consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists predict changes already underway will warm the planet at least 2 or 3 degrees Centigrade this century, and perhaps double or triple that if humans don't alter the behaviors that contribute to climate change. Current scientific estimates suggest that an increase of 2 degrees Centigrade may be the "tipping point" that triggers irreversible changes (such as methane release from melting permafrost) with unpredictable but severe consequences for the planet and its inhabitants, Dr. Muller said.

Some projected changes already are being seen in the extreme summer heat in western Russia, flooding in Pakistan, intense wildfires in Australia, and drought in regions of the United States and elsewhere. The patterns of resulting changes in some skin diseases from these conditions will vary regionally depending on altitude, latitude, storms, deforestation, desertification, urbanization, land use patterns, energy production, and transportation.

Dr. Muller highlighted changes in several diseases:

• Lyme disease. Lyme disease used to be limited to five U.S. geographic regions, but its geographic range has expanded into many areas of Canada as temperatures have become more hospitable to the rodents and deer that act as vectors and reservoirs, spreading into southern and northern Ontario, southern Québec, Manitoba, the Prairie Provinces, the Maritime Provinces, and British Columbia.

• Leishmaniasis. This vector-borne parasitic disease is endemic in most tropical regions of the world and has begun to expand northward as more habitats become suitable for the rodents and sand flies that act as vectors and reservoirs for Leishmaniasis. The parasite has been isolated from humans, dogs, rodents, and sand flies in Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Climate change will exacerbate this spread, especially into the east-central United States, Dr. Muller predicted.

• Chagas' disease. The protozoan that causes Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi is becoming more common in U.S. wildlife reservoirs, with prevalences increasing by 37% in opossums, by 47% in southeastern U.S. raccoons, and by 29% in Louisiana armadillos, he said. It is expected to spread into central U.S. regions if average temperatures rise by 1 degree Centigrade by 2030, as predicted. Few states require reporting of Chagas' disease, but the Food and Drug Administration in 2010 approved screening for the disease in blood, tissue, and organ donors.

• Carrion's disease. Children bear the brunt of this reemerging disease that has spread to new areas between the jungle and highlands of Peru and Ecuador. Changes in sea surface temperatures that triggered extreme seasonal rain patterns known as El Niño events in the 1980s and 1990s were associated with a nearly fourfold increase in Carrion's disease in Peru's Ancash region.

Dr. Muller urged dermatologists to join the International Society of Dermatology and attend its climate change conferences. Scientific, political, and public strategies are needed to help reduce human contributions to climate change and to plan adaptations to reduce damage caused by global warming, he said.

Dr. Muller said he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS - Some of the effects of climate change are beginning to appear in dermatologists' offices, and there may be more to come.

Expanded geographic ranges of tick and parasite vectors due to climate change already are pushing infectious diseases into unfamiliar territory, Dr. Sigfrid A. Muller said at a dermatology seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

Lyme disease has spread well into Canada, and leishmaniasis is moving north from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Reports of Chagas disease are increasing in the United States and Central and South America. Peru and Ecuador are seeing more Carrion’s disease, he said.

Extreme heat, drought, and wide-scale fires, storms, and flooding, as well as other manifestations of climate change, will alter the incidence and severity of allergies, atopic dermatitis, and asthma, added Dr. Muller, a dermatologist in Las Vegas and chair of the International Society of Dermatology's Climate Change Task Force. The society, in 2009, declared climate change to be the defining dermatologic issue of the 21st century.

Global warming may be debated in the popular media, but there is little controversy about it in the scientific literature, he said. June 2010 was the warmest month on record (combining global land and ocean average surface temperatures) and the 304th consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists predict changes already underway will warm the planet at least 2 or 3 degrees Centigrade this century, and perhaps double or triple that if humans don't alter the behaviors that contribute to climate change. Current scientific estimates suggest that an increase of 2 degrees Centigrade may be the "tipping point" that triggers irreversible changes (such as methane release from melting permafrost) with unpredictable but severe consequences for the planet and its inhabitants, Dr. Muller said.

Some projected changes already are being seen in the extreme summer heat in western Russia, flooding in Pakistan, intense wildfires in Australia, and drought in regions of the United States and elsewhere. The patterns of resulting changes in some skin diseases from these conditions will vary regionally depending on altitude, latitude, storms, deforestation, desertification, urbanization, land use patterns, energy production, and transportation.

Dr. Muller highlighted changes in several diseases:

• Lyme disease. Lyme disease used to be limited to five U.S. geographic regions, but its geographic range has expanded into many areas of Canada as temperatures have become more hospitable to the rodents and deer that act as vectors and reservoirs, spreading into southern and northern Ontario, southern Québec, Manitoba, the Prairie Provinces, the Maritime Provinces, and British Columbia.

• Leishmaniasis. This vector-borne parasitic disease is endemic in most tropical regions of the world and has begun to expand northward as more habitats become suitable for the rodents and sand flies that act as vectors and reservoirs for Leishmaniasis. The parasite has been isolated from humans, dogs, rodents, and sand flies in Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Climate change will exacerbate this spread, especially into the east-central United States, Dr. Muller predicted.

• Chagas' disease. The protozoan that causes Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi is becoming more common in U.S. wildlife reservoirs, with prevalences increasing by 37% in opossums, by 47% in southeastern U.S. raccoons, and by 29% in Louisiana armadillos, he said. It is expected to spread into central U.S. regions if average temperatures rise by 1 degree Centigrade by 2030, as predicted. Few states require reporting of Chagas' disease, but the Food and Drug Administration in 2010 approved screening for the disease in blood, tissue, and organ donors.

• Carrion's disease. Children bear the brunt of this reemerging disease that has spread to new areas between the jungle and highlands of Peru and Ecuador. Changes in sea surface temperatures that triggered extreme seasonal rain patterns known as El Niño events in the 1980s and 1990s were associated with a nearly fourfold increase in Carrion's disease in Peru's Ancash region.

Dr. Muller urged dermatologists to join the International Society of Dermatology and attend its climate change conferences. Scientific, political, and public strategies are needed to help reduce human contributions to climate change and to plan adaptations to reduce damage caused by global warming, he said.

Dr. Muller said he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS - Some of the effects of climate change are beginning to appear in dermatologists' offices, and there may be more to come.

Expanded geographic ranges of tick and parasite vectors due to climate change already are pushing infectious diseases into unfamiliar territory, Dr. Sigfrid A. Muller said at a dermatology seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

Lyme disease has spread well into Canada, and leishmaniasis is moving north from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Reports of Chagas disease are increasing in the United States and Central and South America. Peru and Ecuador are seeing more Carrion’s disease, he said.

Extreme heat, drought, and wide-scale fires, storms, and flooding, as well as other manifestations of climate change, will alter the incidence and severity of allergies, atopic dermatitis, and asthma, added Dr. Muller, a dermatologist in Las Vegas and chair of the International Society of Dermatology's Climate Change Task Force. The society, in 2009, declared climate change to be the defining dermatologic issue of the 21st century.

Global warming may be debated in the popular media, but there is little controversy about it in the scientific literature, he said. June 2010 was the warmest month on record (combining global land and ocean average surface temperatures) and the 304th consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists predict changes already underway will warm the planet at least 2 or 3 degrees Centigrade this century, and perhaps double or triple that if humans don't alter the behaviors that contribute to climate change. Current scientific estimates suggest that an increase of 2 degrees Centigrade may be the "tipping point" that triggers irreversible changes (such as methane release from melting permafrost) with unpredictable but severe consequences for the planet and its inhabitants, Dr. Muller said.

Some projected changes already are being seen in the extreme summer heat in western Russia, flooding in Pakistan, intense wildfires in Australia, and drought in regions of the United States and elsewhere. The patterns of resulting changes in some skin diseases from these conditions will vary regionally depending on altitude, latitude, storms, deforestation, desertification, urbanization, land use patterns, energy production, and transportation.

Dr. Muller highlighted changes in several diseases:

• Lyme disease. Lyme disease used to be limited to five U.S. geographic regions, but its geographic range has expanded into many areas of Canada as temperatures have become more hospitable to the rodents and deer that act as vectors and reservoirs, spreading into southern and northern Ontario, southern Québec, Manitoba, the Prairie Provinces, the Maritime Provinces, and British Columbia.

• Leishmaniasis. This vector-borne parasitic disease is endemic in most tropical regions of the world and has begun to expand northward as more habitats become suitable for the rodents and sand flies that act as vectors and reservoirs for Leishmaniasis. The parasite has been isolated from humans, dogs, rodents, and sand flies in Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Climate change will exacerbate this spread, especially into the east-central United States, Dr. Muller predicted.

• Chagas' disease. The protozoan that causes Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi is becoming more common in U.S. wildlife reservoirs, with prevalences increasing by 37% in opossums, by 47% in southeastern U.S. raccoons, and by 29% in Louisiana armadillos, he said. It is expected to spread into central U.S. regions if average temperatures rise by 1 degree Centigrade by 2030, as predicted. Few states require reporting of Chagas' disease, but the Food and Drug Administration in 2010 approved screening for the disease in blood, tissue, and organ donors.

• Carrion's disease. Children bear the brunt of this reemerging disease that has spread to new areas between the jungle and highlands of Peru and Ecuador. Changes in sea surface temperatures that triggered extreme seasonal rain patterns known as El Niño events in the 1980s and 1990s were associated with a nearly fourfold increase in Carrion's disease in Peru's Ancash region.

Dr. Muller urged dermatologists to join the International Society of Dermatology and attend its climate change conferences. Scientific, political, and public strategies are needed to help reduce human contributions to climate change and to plan adaptations to reduce damage caused by global warming, he said.

Dr. Muller said he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

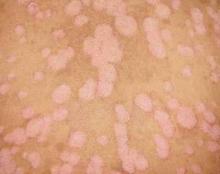

Assess and Treat Cardiovascular Risk in Psoriasis

LAS VEGAS - Dermatologists may be doing patients with psoriasis a disservice if they don’t prescribe a good anti-inflammatory drug to reduce the risk of MI, according to Dr. Bruce E. Strober.

People with psoriasis are more likely to have comorbidities and behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease including smoking, alcohol misuse, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Dyslipidemia therapies that patients with psoriasis may take such as corticosteroids, acitretin, and cyclosporine can also increase cardiovascular risk.

Aside from these, psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk for MI, stroke and death, probably due to the cardiovascular effects of uncontrolled inflammation, Dr. Strober said at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

"You might say to a patient, this is a disease that has every bit as much an effect as hypertension on mortality. The data on hypertension are not even as impressive as this," said Dr. Strober of the department of dermatology at New York University. "Maybe this is a big deal that cardiologists need to think about. They are starting to catch on."

Rheumatoid arthritis studies show that methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor blockers reduce comorbid risks, and the same may be true for psoriasis. "That’s why I sometimes say methotrexate may have an overall net benefit when given to patients with severe psoriasis," he said. Any potential toxicity from methotrexate should be weighed against its potential cardiovascular advantages. A prospective, British population–based cohort study found that the incidence of MI was 3.6 per 1,000 patient-years among 556,995 control patients without psoriasis, 4.0 among 127,139 patients with mild psoriasis, and 5.1 among 3,837 patients with severe psoriasis after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors (JAMA 2006;296:1735-41).

Younger patients with severe psoriasis had the greatest risk. The relative risk for MI with mild psoriasis was 1.3 in 30-year-olds and 1.1 in 60-year-olds. The relative risk for MI with severe psoriasis was 3.1 for 30-year-olds and 1.4 for 60-year-olds.

The study may have underestimated the cardiovascular risk of severe psoriasis by limiting the definition of severe disease to patients on systemic therapy, Dr. Strober added. Some with severe disease may have been assigned to the mild psoriasis category.

The most likely cause of this increased risk for MI is uncontrolled inflammation in systemic psoriasis, not unlike rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which also are known to create MI risk, he said. Psoriasis has immune effects and creates a hyperinflammatory state. Uncontrolled inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction and dyslipidemia.

A separate study of the same British database found that women and men with psoriasis died 3.5 years and 4.4 years, respectively, earlier than people without psoriasis after controlling for other risk factors for mortality (Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-99).

Other data sets have substantiated this concept in the Medicare population. "People with psoriasis die younger. We have to think of this as a disease that has a direct effect on mortality," Dr. Strober said.

Will dermatologists accept the role of primary screeners for comorbidities that increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and other problems? That remains to be seen, but the National Psoriasis Foundation’s 2008 clinical consensus statement provided guidance for dermatologists willing to screen (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:1031-42).

Basic screening steps include assessing blood pressure and overweight or obese status and getting laboratory evaluations – a fasting comprehensive metabolic panel and fasting lipids. Physicians also should ask about use of alcohol, smoking, depression, and arthritis.

Comorbidities may make it harder to treat psoriasis, and vice versa, though data are sparse, Dr. Strober said. Obese patients, for example, may need larger doses of psoriasis medications. The hyperinflammatory state of psoriasis may make treating psoriasis difficult unless it's addressed, and conceivably make it more difficult to treat hypertension or dyslipidemia, but this has not been studied, he said.

Dr. Strober has received grants from or been a consultant, speaker or advisor for Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Celgene.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS - Dermatologists may be doing patients with psoriasis a disservice if they don’t prescribe a good anti-inflammatory drug to reduce the risk of MI, according to Dr. Bruce E. Strober.

People with psoriasis are more likely to have comorbidities and behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease including smoking, alcohol misuse, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Dyslipidemia therapies that patients with psoriasis may take such as corticosteroids, acitretin, and cyclosporine can also increase cardiovascular risk.

Aside from these, psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk for MI, stroke and death, probably due to the cardiovascular effects of uncontrolled inflammation, Dr. Strober said at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

"You might say to a patient, this is a disease that has every bit as much an effect as hypertension on mortality. The data on hypertension are not even as impressive as this," said Dr. Strober of the department of dermatology at New York University. "Maybe this is a big deal that cardiologists need to think about. They are starting to catch on."

Rheumatoid arthritis studies show that methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor blockers reduce comorbid risks, and the same may be true for psoriasis. "That’s why I sometimes say methotrexate may have an overall net benefit when given to patients with severe psoriasis," he said. Any potential toxicity from methotrexate should be weighed against its potential cardiovascular advantages. A prospective, British population–based cohort study found that the incidence of MI was 3.6 per 1,000 patient-years among 556,995 control patients without psoriasis, 4.0 among 127,139 patients with mild psoriasis, and 5.1 among 3,837 patients with severe psoriasis after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors (JAMA 2006;296:1735-41).

Younger patients with severe psoriasis had the greatest risk. The relative risk for MI with mild psoriasis was 1.3 in 30-year-olds and 1.1 in 60-year-olds. The relative risk for MI with severe psoriasis was 3.1 for 30-year-olds and 1.4 for 60-year-olds.

The study may have underestimated the cardiovascular risk of severe psoriasis by limiting the definition of severe disease to patients on systemic therapy, Dr. Strober added. Some with severe disease may have been assigned to the mild psoriasis category.

The most likely cause of this increased risk for MI is uncontrolled inflammation in systemic psoriasis, not unlike rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which also are known to create MI risk, he said. Psoriasis has immune effects and creates a hyperinflammatory state. Uncontrolled inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction and dyslipidemia.

A separate study of the same British database found that women and men with psoriasis died 3.5 years and 4.4 years, respectively, earlier than people without psoriasis after controlling for other risk factors for mortality (Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-99).

Other data sets have substantiated this concept in the Medicare population. "People with psoriasis die younger. We have to think of this as a disease that has a direct effect on mortality," Dr. Strober said.

Will dermatologists accept the role of primary screeners for comorbidities that increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and other problems? That remains to be seen, but the National Psoriasis Foundation’s 2008 clinical consensus statement provided guidance for dermatologists willing to screen (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:1031-42).

Basic screening steps include assessing blood pressure and overweight or obese status and getting laboratory evaluations – a fasting comprehensive metabolic panel and fasting lipids. Physicians also should ask about use of alcohol, smoking, depression, and arthritis.

Comorbidities may make it harder to treat psoriasis, and vice versa, though data are sparse, Dr. Strober said. Obese patients, for example, may need larger doses of psoriasis medications. The hyperinflammatory state of psoriasis may make treating psoriasis difficult unless it's addressed, and conceivably make it more difficult to treat hypertension or dyslipidemia, but this has not been studied, he said.

Dr. Strober has received grants from or been a consultant, speaker or advisor for Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Celgene.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS - Dermatologists may be doing patients with psoriasis a disservice if they don’t prescribe a good anti-inflammatory drug to reduce the risk of MI, according to Dr. Bruce E. Strober.

People with psoriasis are more likely to have comorbidities and behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease including smoking, alcohol misuse, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Dyslipidemia therapies that patients with psoriasis may take such as corticosteroids, acitretin, and cyclosporine can also increase cardiovascular risk.

Aside from these, psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk for MI, stroke and death, probably due to the cardiovascular effects of uncontrolled inflammation, Dr. Strober said at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

"You might say to a patient, this is a disease that has every bit as much an effect as hypertension on mortality. The data on hypertension are not even as impressive as this," said Dr. Strober of the department of dermatology at New York University. "Maybe this is a big deal that cardiologists need to think about. They are starting to catch on."

Rheumatoid arthritis studies show that methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor blockers reduce comorbid risks, and the same may be true for psoriasis. "That’s why I sometimes say methotrexate may have an overall net benefit when given to patients with severe psoriasis," he said. Any potential toxicity from methotrexate should be weighed against its potential cardiovascular advantages. A prospective, British population–based cohort study found that the incidence of MI was 3.6 per 1,000 patient-years among 556,995 control patients without psoriasis, 4.0 among 127,139 patients with mild psoriasis, and 5.1 among 3,837 patients with severe psoriasis after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors (JAMA 2006;296:1735-41).

Younger patients with severe psoriasis had the greatest risk. The relative risk for MI with mild psoriasis was 1.3 in 30-year-olds and 1.1 in 60-year-olds. The relative risk for MI with severe psoriasis was 3.1 for 30-year-olds and 1.4 for 60-year-olds.

The study may have underestimated the cardiovascular risk of severe psoriasis by limiting the definition of severe disease to patients on systemic therapy, Dr. Strober added. Some with severe disease may have been assigned to the mild psoriasis category.

The most likely cause of this increased risk for MI is uncontrolled inflammation in systemic psoriasis, not unlike rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which also are known to create MI risk, he said. Psoriasis has immune effects and creates a hyperinflammatory state. Uncontrolled inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction and dyslipidemia.

A separate study of the same British database found that women and men with psoriasis died 3.5 years and 4.4 years, respectively, earlier than people without psoriasis after controlling for other risk factors for mortality (Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-99).

Other data sets have substantiated this concept in the Medicare population. "People with psoriasis die younger. We have to think of this as a disease that has a direct effect on mortality," Dr. Strober said.

Will dermatologists accept the role of primary screeners for comorbidities that increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and other problems? That remains to be seen, but the National Psoriasis Foundation’s 2008 clinical consensus statement provided guidance for dermatologists willing to screen (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:1031-42).

Basic screening steps include assessing blood pressure and overweight or obese status and getting laboratory evaluations – a fasting comprehensive metabolic panel and fasting lipids. Physicians also should ask about use of alcohol, smoking, depression, and arthritis.

Comorbidities may make it harder to treat psoriasis, and vice versa, though data are sparse, Dr. Strober said. Obese patients, for example, may need larger doses of psoriasis medications. The hyperinflammatory state of psoriasis may make treating psoriasis difficult unless it's addressed, and conceivably make it more difficult to treat hypertension or dyslipidemia, but this has not been studied, he said.

Dr. Strober has received grants from or been a consultant, speaker or advisor for Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Celgene.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Assess and Treat Cardiovascular Risk in Psoriasis

LAS VEGAS – Dermatologists may be doing patients with psoriasis a disservice if they don’t prescribe a good anti-inflammatory drug to reduce the risk of MI, according to Dr. Bruce E. Strober.

People with psoriasis are more likely to have comorbidities and behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease including smoking, alcohol misuse, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Dyslipidemia therapies that patients with psoriasis may take such as corticosteroids, acitretin, and cyclosporine can also increase cardiovascular risk.

Aside from these, psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk for MI, stroke and death, probably due to the cardiovascular effects of uncontrolled inflammation, Dr. Strober said at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

"You might say to a patient, this is a disease that has every bit as much an effect as hypertension on mortality. The data on hypertension are not even as impressive as this," said Dr. Strober of the department of dermatology at New York University. "Maybe this is a big deal that cardiologists need to think about. They are starting to catch on."

Rheumatoid arthritis studies show that methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor blockers reduce comorbid risks, and the same may be true for psoriasis. "That’s why I sometimes say methotrexate may have an overall net benefit when given to patients with severe psoriasis," he said. Any potential toxicity from methotrexate should be weighed against its potential cardiovascular advantages. A prospective, British population–based cohort study found that the incidence of MI was 3.6 per 1,000 patient-years among 556,995 control patients without psoriasis, 4.0 among 127,139 patients with mild psoriasis, and 5.1 among 3,837 patients with severe psoriasis after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors (JAMA 2006;296:1735-41).

Younger patients with severe psoriasis had the greatest risk. The relative risk for MI with mild psoriasis was 1.3 in 30-year-olds and 1.1 in 60-year-olds. The relative risk for MI with severe psoriasis was 3.1 for 30-year-olds and 1.4 for 60-year-olds.

The study may have underestimated the cardiovascular risk of severe psoriasis by limiting the definition of severe disease to patients on systemic therapy, Dr. Strober added. Some with severe disease may have been assigned to the mild psoriasis category.

The most likely cause of this increased risk for MI is uncontrolled inflammation in systemic psoriasis, not unlike rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which also are known to create MI risk, he said. Psoriasis has immune effects and creates a hyperinflammatory state. Uncontrolled inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction and dyslipidemia.

A separate study of the same British database found that women and men with psoriasis died 3.5 years and 4.4 years, respectively, earlier than people without psoriasis after controlling for other risk factors for mortality (Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-99).

Other data sets have substantiated this concept in the Medicare population. "People with psoriasis die younger. We have to think of this as a disease that has a direct effect on mortality," Dr. Strober said.

Will dermatologists accept the role of primary screeners for comorbidities that increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and other problems? That remains to be seen, but the National Psoriasis Foundation’s 2008 clinical consensus statement provided guidance for dermatologists willing to screen (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:1031-42).

Basic screening steps include assessing blood pressure and overweight or obese status and getting laboratory evaluations – a fasting comprehensive metabolic panel and fasting lipids. Physicians also should ask about use of alcohol, smoking, depression, and arthritis.

Comorbidities may make it harder to treat psoriasis, and vice versa, though data are sparse, Dr. Strober said. Obese patients, for example, may need larger doses of psoriasis medications. The hyperinflammatory state of psoriasis may make treating psoriasis difficult unless it’s addressed, and conceivably make it more difficult to treat hypertension or dyslipidemia, but this has not been studied, he said.

Dr. Strober has received grants from or been a consultant, speaker or advisor for Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Celgene.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Dermatologists may be doing patients with psoriasis a disservice if they don’t prescribe a good anti-inflammatory drug to reduce the risk of MI, according to Dr. Bruce E. Strober.

People with psoriasis are more likely to have comorbidities and behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease including smoking, alcohol misuse, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Dyslipidemia therapies that patients with psoriasis may take such as corticosteroids, acitretin, and cyclosporine can also increase cardiovascular risk.

Aside from these, psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk for MI, stroke and death, probably due to the cardiovascular effects of uncontrolled inflammation, Dr. Strober said at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

"You might say to a patient, this is a disease that has every bit as much an effect as hypertension on mortality. The data on hypertension are not even as impressive as this," said Dr. Strober of the department of dermatology at New York University. "Maybe this is a big deal that cardiologists need to think about. They are starting to catch on."

Rheumatoid arthritis studies show that methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor blockers reduce comorbid risks, and the same may be true for psoriasis. "That’s why I sometimes say methotrexate may have an overall net benefit when given to patients with severe psoriasis," he said. Any potential toxicity from methotrexate should be weighed against its potential cardiovascular advantages. A prospective, British population–based cohort study found that the incidence of MI was 3.6 per 1,000 patient-years among 556,995 control patients without psoriasis, 4.0 among 127,139 patients with mild psoriasis, and 5.1 among 3,837 patients with severe psoriasis after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors (JAMA 2006;296:1735-41).

Younger patients with severe psoriasis had the greatest risk. The relative risk for MI with mild psoriasis was 1.3 in 30-year-olds and 1.1 in 60-year-olds. The relative risk for MI with severe psoriasis was 3.1 for 30-year-olds and 1.4 for 60-year-olds.

The study may have underestimated the cardiovascular risk of severe psoriasis by limiting the definition of severe disease to patients on systemic therapy, Dr. Strober added. Some with severe disease may have been assigned to the mild psoriasis category.

The most likely cause of this increased risk for MI is uncontrolled inflammation in systemic psoriasis, not unlike rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which also are known to create MI risk, he said. Psoriasis has immune effects and creates a hyperinflammatory state. Uncontrolled inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction and dyslipidemia.

A separate study of the same British database found that women and men with psoriasis died 3.5 years and 4.4 years, respectively, earlier than people without psoriasis after controlling for other risk factors for mortality (Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-99).

Other data sets have substantiated this concept in the Medicare population. "People with psoriasis die younger. We have to think of this as a disease that has a direct effect on mortality," Dr. Strober said.

Will dermatologists accept the role of primary screeners for comorbidities that increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and other problems? That remains to be seen, but the National Psoriasis Foundation’s 2008 clinical consensus statement provided guidance for dermatologists willing to screen (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:1031-42).

Basic screening steps include assessing blood pressure and overweight or obese status and getting laboratory evaluations – a fasting comprehensive metabolic panel and fasting lipids. Physicians also should ask about use of alcohol, smoking, depression, and arthritis.

Comorbidities may make it harder to treat psoriasis, and vice versa, though data are sparse, Dr. Strober said. Obese patients, for example, may need larger doses of psoriasis medications. The hyperinflammatory state of psoriasis may make treating psoriasis difficult unless it’s addressed, and conceivably make it more difficult to treat hypertension or dyslipidemia, but this has not been studied, he said.

Dr. Strober has received grants from or been a consultant, speaker or advisor for Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Celgene.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Dermatologists may be doing patients with psoriasis a disservice if they don’t prescribe a good anti-inflammatory drug to reduce the risk of MI, according to Dr. Bruce E. Strober.

People with psoriasis are more likely to have comorbidities and behaviors associated with cardiovascular disease including smoking, alcohol misuse, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. Dyslipidemia therapies that patients with psoriasis may take such as corticosteroids, acitretin, and cyclosporine can also increase cardiovascular risk.

Aside from these, psoriasis is independently associated with a higher risk for MI, stroke and death, probably due to the cardiovascular effects of uncontrolled inflammation, Dr. Strober said at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

"You might say to a patient, this is a disease that has every bit as much an effect as hypertension on mortality. The data on hypertension are not even as impressive as this," said Dr. Strober of the department of dermatology at New York University. "Maybe this is a big deal that cardiologists need to think about. They are starting to catch on."

Rheumatoid arthritis studies show that methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor blockers reduce comorbid risks, and the same may be true for psoriasis. "That’s why I sometimes say methotrexate may have an overall net benefit when given to patients with severe psoriasis," he said. Any potential toxicity from methotrexate should be weighed against its potential cardiovascular advantages. A prospective, British population–based cohort study found that the incidence of MI was 3.6 per 1,000 patient-years among 556,995 control patients without psoriasis, 4.0 among 127,139 patients with mild psoriasis, and 5.1 among 3,837 patients with severe psoriasis after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors (JAMA 2006;296:1735-41).

Younger patients with severe psoriasis had the greatest risk. The relative risk for MI with mild psoriasis was 1.3 in 30-year-olds and 1.1 in 60-year-olds. The relative risk for MI with severe psoriasis was 3.1 for 30-year-olds and 1.4 for 60-year-olds.

The study may have underestimated the cardiovascular risk of severe psoriasis by limiting the definition of severe disease to patients on systemic therapy, Dr. Strober added. Some with severe disease may have been assigned to the mild psoriasis category.

The most likely cause of this increased risk for MI is uncontrolled inflammation in systemic psoriasis, not unlike rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, which also are known to create MI risk, he said. Psoriasis has immune effects and creates a hyperinflammatory state. Uncontrolled inflammation leads to endothelial dysfunction and dyslipidemia.

A separate study of the same British database found that women and men with psoriasis died 3.5 years and 4.4 years, respectively, earlier than people without psoriasis after controlling for other risk factors for mortality (Arch. Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-99).

Other data sets have substantiated this concept in the Medicare population. "People with psoriasis die younger. We have to think of this as a disease that has a direct effect on mortality," Dr. Strober said.

Will dermatologists accept the role of primary screeners for comorbidities that increase the risk for cardiovascular disease and other problems? That remains to be seen, but the National Psoriasis Foundation’s 2008 clinical consensus statement provided guidance for dermatologists willing to screen (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;58:1031-42).

Basic screening steps include assessing blood pressure and overweight or obese status and getting laboratory evaluations – a fasting comprehensive metabolic panel and fasting lipids. Physicians also should ask about use of alcohol, smoking, depression, and arthritis.

Comorbidities may make it harder to treat psoriasis, and vice versa, though data are sparse, Dr. Strober said. Obese patients, for example, may need larger doses of psoriasis medications. The hyperinflammatory state of psoriasis may make treating psoriasis difficult unless it’s addressed, and conceivably make it more difficult to treat hypertension or dyslipidemia, but this has not been studied, he said.

Dr. Strober has received grants from or been a consultant, speaker or advisor for Abbott, Amgen, Centocor, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and Celgene.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

Climate Change May Result in More Skin Disease

LAS VEGAS – Some of the effects of climate change are beginning to appear in dermatologists’ offices, and there may be more to come.

Expanded geographic ranges of tick and parasite vectors due to climate change already are pushing infectious diseases into unfamiliar territory, Dr. Sigfrid A. Muller said at a dermatology seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

Lyme disease has spread well into Canada, and leishmaniasis is moving north from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Reports of Chagas disease are increasing in the United States and Central and South America. Peru and Ecuador are seeing more Carrion’s disease, he said.

Extreme heat, drought, and wide-scale fires, storms, and flooding, as well as other manifestations of climate change, will alter the incidence and severity of allergies, atopic dermatitis, and asthma, added Dr. Muller, a dermatologist in Las Vegas and chair of the International Society of Dermatology’s Climate Change Task Force. The society, in 2009, declared climate change to be the defining dermatologic issue of the 21st century.

Global warming may be debated in the popular media, but there is little controversy about it in the scientific literature, he said. June 2010 was the warmest month on record (combining global land and ocean average surface temperatures) and the 304th consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists predict changes already underway will warm the planet at least 2 or 3 degrees Centigrade this century, and perhaps double or triple that if humans don’t alter the behaviors that contribute to climate change. Current scientific estimates suggest that an increase of 2 degrees Centigrade may be the "tipping point" that triggers irreversible changes (such as methane release from melting permafrost) with unpredictable but severe consequences for the planet and its inhabitants, Dr. Muller said.

Some projected changes already are being seen in the extreme summer heat in western Russia, flooding in Pakistan, intense wildfires in Australia, and drought in regions of the United States and elsewhere. The patterns of resulting changes in some skin diseases from these conditions will vary regionally depending on altitude, latitude, storms, deforestation, desertification, urbanization, land use patterns, energy production, and transportation.

Dr. Muller highlighted changes in several diseases:

• Lyme disease. Lyme disease used to be limited to five U.S. geographic regions, but its geographic range has expanded into many areas of Canada as temperatures have become more hospitable to the rodents and deer that act as vectors and reservoirs, spreading into southern and northern Ontario, southern Qu?bec, Manitoba, the Prairie Provinces, the Maritime Provinces, and British Columbia.

• Leishmaniasis. This vector-borne parasitic disease is endemic in most tropical regions of the world and has begun to expand northward as more habitats become suitable for the rodents and sand flies that act as vectors and reservoirs for Leishmaniasis. The parasite has been isolated from humans, dogs, rodents, and sand flies in Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Climate change will exacerbate this spread, especially into the east-central United States, Dr. Muller predicted.

• Chagas disease. The protozoan that causes Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi is becoming more common in U.S. wildlife reservoirs, with prevalences increasing by 37% in opossums, by 47% in southeastern U.S. raccoons, and by 29% in Louisiana armadillos, he said. It is expected to spread into central U.S. regions if average temperatures rise by 1 degree Centigrade by 2030, as predicted. Few states require reporting of Chagas disease, but the Food and Drug Administration in 2010 approved screening for the disease in blood, tissue, and organ donors.

• Carrion’s disease. Children bear the brunt of this reemerging disease that has spread to new areas between the jungle and highlands of Peru and Ecuador. Changes in sea surface temperatures that triggered extreme seasonal rain patterns known as El Niño events in the 1980s and 1990s were associated with a nearly fourfold increase in Carrion’s disease in Peru’s Ancash region.

Dr. Muller urged dermatologists to join the International Society of Dermatology and attend its climate change conferences. Scientific, political, and public strategies are needed to help reduce human contributions to climate change and to plan adaptations to reduce damage caused by global warming, he said.

Muller said he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Some of the effects of climate change are beginning to appear in dermatologists’ offices, and there may be more to come.

Expanded geographic ranges of tick and parasite vectors due to climate change already are pushing infectious diseases into unfamiliar territory, Dr. Sigfrid A. Muller said at a dermatology seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

Lyme disease has spread well into Canada, and leishmaniasis is moving north from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Reports of Chagas disease are increasing in the United States and Central and South America. Peru and Ecuador are seeing more Carrion’s disease, he said.

Extreme heat, drought, and wide-scale fires, storms, and flooding, as well as other manifestations of climate change, will alter the incidence and severity of allergies, atopic dermatitis, and asthma, added Dr. Muller, a dermatologist in Las Vegas and chair of the International Society of Dermatology’s Climate Change Task Force. The society, in 2009, declared climate change to be the defining dermatologic issue of the 21st century.

Global warming may be debated in the popular media, but there is little controversy about it in the scientific literature, he said. June 2010 was the warmest month on record (combining global land and ocean average surface temperatures) and the 304th consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists predict changes already underway will warm the planet at least 2 or 3 degrees Centigrade this century, and perhaps double or triple that if humans don’t alter the behaviors that contribute to climate change. Current scientific estimates suggest that an increase of 2 degrees Centigrade may be the "tipping point" that triggers irreversible changes (such as methane release from melting permafrost) with unpredictable but severe consequences for the planet and its inhabitants, Dr. Muller said.

Some projected changes already are being seen in the extreme summer heat in western Russia, flooding in Pakistan, intense wildfires in Australia, and drought in regions of the United States and elsewhere. The patterns of resulting changes in some skin diseases from these conditions will vary regionally depending on altitude, latitude, storms, deforestation, desertification, urbanization, land use patterns, energy production, and transportation.

Dr. Muller highlighted changes in several diseases:

• Lyme disease. Lyme disease used to be limited to five U.S. geographic regions, but its geographic range has expanded into many areas of Canada as temperatures have become more hospitable to the rodents and deer that act as vectors and reservoirs, spreading into southern and northern Ontario, southern Qu?bec, Manitoba, the Prairie Provinces, the Maritime Provinces, and British Columbia.

• Leishmaniasis. This vector-borne parasitic disease is endemic in most tropical regions of the world and has begun to expand northward as more habitats become suitable for the rodents and sand flies that act as vectors and reservoirs for Leishmaniasis. The parasite has been isolated from humans, dogs, rodents, and sand flies in Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Climate change will exacerbate this spread, especially into the east-central United States, Dr. Muller predicted.

• Chagas disease. The protozoan that causes Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi is becoming more common in U.S. wildlife reservoirs, with prevalences increasing by 37% in opossums, by 47% in southeastern U.S. raccoons, and by 29% in Louisiana armadillos, he said. It is expected to spread into central U.S. regions if average temperatures rise by 1 degree Centigrade by 2030, as predicted. Few states require reporting of Chagas disease, but the Food and Drug Administration in 2010 approved screening for the disease in blood, tissue, and organ donors.

• Carrion’s disease. Children bear the brunt of this reemerging disease that has spread to new areas between the jungle and highlands of Peru and Ecuador. Changes in sea surface temperatures that triggered extreme seasonal rain patterns known as El Niño events in the 1980s and 1990s were associated with a nearly fourfold increase in Carrion’s disease in Peru’s Ancash region.

Dr. Muller urged dermatologists to join the International Society of Dermatology and attend its climate change conferences. Scientific, political, and public strategies are needed to help reduce human contributions to climate change and to plan adaptations to reduce damage caused by global warming, he said.

Muller said he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Some of the effects of climate change are beginning to appear in dermatologists’ offices, and there may be more to come.

Expanded geographic ranges of tick and parasite vectors due to climate change already are pushing infectious diseases into unfamiliar territory, Dr. Sigfrid A. Muller said at a dermatology seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF).

Lyme disease has spread well into Canada, and leishmaniasis is moving north from Mexico into Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Reports of Chagas disease are increasing in the United States and Central and South America. Peru and Ecuador are seeing more Carrion’s disease, he said.

Extreme heat, drought, and wide-scale fires, storms, and flooding, as well as other manifestations of climate change, will alter the incidence and severity of allergies, atopic dermatitis, and asthma, added Dr. Muller, a dermatologist in Las Vegas and chair of the International Society of Dermatology’s Climate Change Task Force. The society, in 2009, declared climate change to be the defining dermatologic issue of the 21st century.

Global warming may be debated in the popular media, but there is little controversy about it in the scientific literature, he said. June 2010 was the warmest month on record (combining global land and ocean average surface temperatures) and the 304th consecutive month with a global temperature above the 20th-century average, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Scientists predict changes already underway will warm the planet at least 2 or 3 degrees Centigrade this century, and perhaps double or triple that if humans don’t alter the behaviors that contribute to climate change. Current scientific estimates suggest that an increase of 2 degrees Centigrade may be the "tipping point" that triggers irreversible changes (such as methane release from melting permafrost) with unpredictable but severe consequences for the planet and its inhabitants, Dr. Muller said.

Some projected changes already are being seen in the extreme summer heat in western Russia, flooding in Pakistan, intense wildfires in Australia, and drought in regions of the United States and elsewhere. The patterns of resulting changes in some skin diseases from these conditions will vary regionally depending on altitude, latitude, storms, deforestation, desertification, urbanization, land use patterns, energy production, and transportation.

Dr. Muller highlighted changes in several diseases:

• Lyme disease. Lyme disease used to be limited to five U.S. geographic regions, but its geographic range has expanded into many areas of Canada as temperatures have become more hospitable to the rodents and deer that act as vectors and reservoirs, spreading into southern and northern Ontario, southern Qu?bec, Manitoba, the Prairie Provinces, the Maritime Provinces, and British Columbia.

• Leishmaniasis. This vector-borne parasitic disease is endemic in most tropical regions of the world and has begun to expand northward as more habitats become suitable for the rodents and sand flies that act as vectors and reservoirs for Leishmaniasis. The parasite has been isolated from humans, dogs, rodents, and sand flies in Texas, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Ohio. Climate change will exacerbate this spread, especially into the east-central United States, Dr. Muller predicted.

• Chagas disease. The protozoan that causes Chagas disease Trypanosoma cruzi is becoming more common in U.S. wildlife reservoirs, with prevalences increasing by 37% in opossums, by 47% in southeastern U.S. raccoons, and by 29% in Louisiana armadillos, he said. It is expected to spread into central U.S. regions if average temperatures rise by 1 degree Centigrade by 2030, as predicted. Few states require reporting of Chagas disease, but the Food and Drug Administration in 2010 approved screening for the disease in blood, tissue, and organ donors.

• Carrion’s disease. Children bear the brunt of this reemerging disease that has spread to new areas between the jungle and highlands of Peru and Ecuador. Changes in sea surface temperatures that triggered extreme seasonal rain patterns known as El Niño events in the 1980s and 1990s were associated with a nearly fourfold increase in Carrion’s disease in Peru’s Ancash region.

Dr. Muller urged dermatologists to join the International Society of Dermatology and attend its climate change conferences. Scientific, political, and public strategies are needed to help reduce human contributions to climate change and to plan adaptations to reduce damage caused by global warming, he said.

Muller said he has no relevant conflicts of interest.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Patch Testing Still Possible With Immunosuppressive Therapy

LAS VEGAS – Immunosuppressive drug therapy is not an absolute contraindication for allergy patch testing, according to Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr.

A recent report on 11 patients who underwent patch testing while on a variety of systemic immunosuppressive drugs suggested patch testing may be more successful than many clinicians think, Dr. Fowler said. Speaking at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF), he fleshed out the findings with advice from his own experience in patch testing patients on immunosuppressives.

The retrospective chart review included patients on prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or infliximab (Dermatitis 2009;20:265-70).

All but one of the patients who were taking 10 mg/day of prednisone had positive patch test reactions, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.) and president of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group.

"In the past, we had thought that about 10 mg/day was the maximum" prednisone dose that could still allow successful patch testing, but this belief was based on extrapolations of animal studies and case reports, with no hard data, he said. "I have personally seen patients who are on higher doses of prednisone produce good positive reactions."

Ideally, though, it’s best to patch test when patients are off prednisone, or on doses of 10 mg/day or less, he added. "If you could get them on every-other-day prednisone dosing, that would be even better."

For an untreated patient with fairly bad dermatitis, especially on the back, Dr. Fowler may treat for 5-7 days with a corticosteroid, perhaps prednisone 40-60 mg/day with no taper, and then stop the corticosteroid for 2-3 days before patch testing. "That’s one way you can get a person clear enough to patch test them if they’re already broken out," he said.

If the patient already is on chronic corticosteroid therapy, he tries to reduce the dose to 10 mg/day or less for several weeks before patch testing.

Dr. Fowler was surprised patients in the report who were being treated with cyclosporine 200 or 300 mg/day all had positive reactions to patch testing. "Generally, we expect cyclosporine to reduce the likelihood of positive reactions because of its broad immunosuppressant effect," he said. "These folks were on relatively low doses, so maybe that was a factor." In his own experience, Dr. Fowler said he has rarely seen positive reactions to patch testing in patients on cyclosporine, "so I think that’s problematic," he added.

One patient on mycophenolate (CellCept) 2 g/day had a negative result when patch tested but then stopped the drug and had a positive reaction on repeat patch testing. "That would suggest that the CellCept suppressed reactions," Dr. Fowler said. He advised not patch testing patients who are on CellCept, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or azathioprine if at all possible.

One patient on infliximab (Remicade) whose last infusion occurred 3 weeks before patch testing developed multiple positive reactions. "That mirrors what I’ve been perceiving in clinical practice," he said.

Use of methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors such as Remicade or etanercept (Enbrel) should not prevent patch testing. "I’ve had no problem patch testing people on methotrexate," Dr. Fowler said.

The report did not include antihistamines, which also are not a barrier to patch testing. "Other docs, allergists especially, tell patients they can’t take antihistamines when they’re being patch tested," he explained. "They may not be able to take antihistamines and get a good scratch test result, but remember in patch testing you’re looking at a T cell–mediated process. Antihistamines have essentially no effect on that."

Dr. Fowler has been a consultant, speaker, or researcher for Coria, Galderma, Graceway, Hyland, Johnson & Johnson, Quinnova, Ranbaxy, Shire, Stiefel, Triax, UCB, Medicis, Novartis, Abbott, Taro, Allerderm, Allergan, Amgen, Astellas, Centocor, Dermik, Dow, Genentech, Taisho, and 3M.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Immunosuppressive drug therapy is not an absolute contraindication for allergy patch testing, according to Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr.

A recent report on 11 patients who underwent patch testing while on a variety of systemic immunosuppressive drugs suggested patch testing may be more successful than many clinicians think, Dr. Fowler said. Speaking at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF), he fleshed out the findings with advice from his own experience in patch testing patients on immunosuppressives.

The retrospective chart review included patients on prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or infliximab (Dermatitis 2009;20:265-70).

All but one of the patients who were taking 10 mg/day of prednisone had positive patch test reactions, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.) and president of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group.

"In the past, we had thought that about 10 mg/day was the maximum" prednisone dose that could still allow successful patch testing, but this belief was based on extrapolations of animal studies and case reports, with no hard data, he said. "I have personally seen patients who are on higher doses of prednisone produce good positive reactions."

Ideally, though, it’s best to patch test when patients are off prednisone, or on doses of 10 mg/day or less, he added. "If you could get them on every-other-day prednisone dosing, that would be even better."

For an untreated patient with fairly bad dermatitis, especially on the back, Dr. Fowler may treat for 5-7 days with a corticosteroid, perhaps prednisone 40-60 mg/day with no taper, and then stop the corticosteroid for 2-3 days before patch testing. "That’s one way you can get a person clear enough to patch test them if they’re already broken out," he said.

If the patient already is on chronic corticosteroid therapy, he tries to reduce the dose to 10 mg/day or less for several weeks before patch testing.

Dr. Fowler was surprised patients in the report who were being treated with cyclosporine 200 or 300 mg/day all had positive reactions to patch testing. "Generally, we expect cyclosporine to reduce the likelihood of positive reactions because of its broad immunosuppressant effect," he said. "These folks were on relatively low doses, so maybe that was a factor." In his own experience, Dr. Fowler said he has rarely seen positive reactions to patch testing in patients on cyclosporine, "so I think that’s problematic," he added.

One patient on mycophenolate (CellCept) 2 g/day had a negative result when patch tested but then stopped the drug and had a positive reaction on repeat patch testing. "That would suggest that the CellCept suppressed reactions," Dr. Fowler said. He advised not patch testing patients who are on CellCept, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or azathioprine if at all possible.

One patient on infliximab (Remicade) whose last infusion occurred 3 weeks before patch testing developed multiple positive reactions. "That mirrors what I’ve been perceiving in clinical practice," he said.

Use of methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors such as Remicade or etanercept (Enbrel) should not prevent patch testing. "I’ve had no problem patch testing people on methotrexate," Dr. Fowler said.

The report did not include antihistamines, which also are not a barrier to patch testing. "Other docs, allergists especially, tell patients they can’t take antihistamines when they’re being patch tested," he explained. "They may not be able to take antihistamines and get a good scratch test result, but remember in patch testing you’re looking at a T cell–mediated process. Antihistamines have essentially no effect on that."

Dr. Fowler has been a consultant, speaker, or researcher for Coria, Galderma, Graceway, Hyland, Johnson & Johnson, Quinnova, Ranbaxy, Shire, Stiefel, Triax, UCB, Medicis, Novartis, Abbott, Taro, Allerderm, Allergan, Amgen, Astellas, Centocor, Dermik, Dow, Genentech, Taisho, and 3M.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Immunosuppressive drug therapy is not an absolute contraindication for allergy patch testing, according to Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr.

A recent report on 11 patients who underwent patch testing while on a variety of systemic immunosuppressive drugs suggested patch testing may be more successful than many clinicians think, Dr. Fowler said. Speaking at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF), he fleshed out the findings with advice from his own experience in patch testing patients on immunosuppressives.

The retrospective chart review included patients on prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or infliximab (Dermatitis 2009;20:265-70).

All but one of the patients who were taking 10 mg/day of prednisone had positive patch test reactions, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.) and president of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group.

"In the past, we had thought that about 10 mg/day was the maximum" prednisone dose that could still allow successful patch testing, but this belief was based on extrapolations of animal studies and case reports, with no hard data, he said. "I have personally seen patients who are on higher doses of prednisone produce good positive reactions."

Ideally, though, it’s best to patch test when patients are off prednisone, or on doses of 10 mg/day or less, he added. "If you could get them on every-other-day prednisone dosing, that would be even better."

For an untreated patient with fairly bad dermatitis, especially on the back, Dr. Fowler may treat for 5-7 days with a corticosteroid, perhaps prednisone 40-60 mg/day with no taper, and then stop the corticosteroid for 2-3 days before patch testing. "That’s one way you can get a person clear enough to patch test them if they’re already broken out," he said.

If the patient already is on chronic corticosteroid therapy, he tries to reduce the dose to 10 mg/day or less for several weeks before patch testing.

Dr. Fowler was surprised patients in the report who were being treated with cyclosporine 200 or 300 mg/day all had positive reactions to patch testing. "Generally, we expect cyclosporine to reduce the likelihood of positive reactions because of its broad immunosuppressant effect," he said. "These folks were on relatively low doses, so maybe that was a factor." In his own experience, Dr. Fowler said he has rarely seen positive reactions to patch testing in patients on cyclosporine, "so I think that’s problematic," he added.

One patient on mycophenolate (CellCept) 2 g/day had a negative result when patch tested but then stopped the drug and had a positive reaction on repeat patch testing. "That would suggest that the CellCept suppressed reactions," Dr. Fowler said. He advised not patch testing patients who are on CellCept, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or azathioprine if at all possible.

One patient on infliximab (Remicade) whose last infusion occurred 3 weeks before patch testing developed multiple positive reactions. "That mirrors what I’ve been perceiving in clinical practice," he said.

Use of methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors such as Remicade or etanercept (Enbrel) should not prevent patch testing. "I’ve had no problem patch testing people on methotrexate," Dr. Fowler said.

The report did not include antihistamines, which also are not a barrier to patch testing. "Other docs, allergists especially, tell patients they can’t take antihistamines when they’re being patch tested," he explained. "They may not be able to take antihistamines and get a good scratch test result, but remember in patch testing you’re looking at a T cell–mediated process. Antihistamines have essentially no effect on that."

Dr. Fowler has been a consultant, speaker, or researcher for Coria, Galderma, Graceway, Hyland, Johnson & Johnson, Quinnova, Ranbaxy, Shire, Stiefel, Triax, UCB, Medicis, Novartis, Abbott, Taro, Allerderm, Allergan, Amgen, Astellas, Centocor, Dermik, Dow, Genentech, Taisho, and 3M.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Patch Testing Still Possible With Immunosuppressive Therapy

LAS VEGAS – Immunosuppressive drug therapy is not an absolute contraindication for allergy patch testing, according to Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr.

A recent report on 11 patients who underwent patch testing while on a variety of systemic immunosuppressive drugs suggested patch testing may be more successful than many clinicians think, Dr. Fowler said. Speaking at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF), he fleshed out the findings with advice from his own experience in patch testing patients on immunosuppressives.

The retrospective chart review included patients on prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or infliximab (Dermatitis 2009;20:265-70).

All but one of the patients who were taking 10 mg/day of prednisone had positive patch test reactions, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.) and president of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group.

"In the past, we had thought that about 10 mg/day was the maximum" prednisone dose that could still allow successful patch testing, but this belief was based on extrapolations of animal studies and case reports, with no hard data, he said. "I have personally seen patients who are on higher doses of prednisone produce good positive reactions."

Ideally, though, it’s best to patch test when patients are off prednisone, or on doses of 10 mg/day or less, he added. "If you could get them on every-other-day prednisone dosing, that would be even better."

For an untreated patient with fairly bad dermatitis, especially on the back, Dr. Fowler may treat for 5-7 days with a corticosteroid, perhaps prednisone 40-60 mg/day with no taper, and then stop the corticosteroid for 2-3 days before patch testing. "That’s one way you can get a person clear enough to patch test them if they’re already broken out," he said.

If the patient already is on chronic corticosteroid therapy, he tries to reduce the dose to 10 mg/day or less for several weeks before patch testing.

Dr. Fowler was surprised patients in the report who were being treated with cyclosporine 200 or 300 mg/day all had positive reactions to patch testing. "Generally, we expect cyclosporine to reduce the likelihood of positive reactions because of its broad immunosuppressant effect," he said. "These folks were on relatively low doses, so maybe that was a factor." In his own experience, Dr. Fowler said he has rarely seen positive reactions to patch testing in patients on cyclosporine, "so I think that’s problematic," he added.

One patient on mycophenolate (CellCept) 2 g/day had a negative result when patch tested but then stopped the drug and had a positive reaction on repeat patch testing. "That would suggest that the CellCept suppressed reactions," Dr. Fowler said. He advised not patch testing patients who are on CellCept, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or azathioprine if at all possible.

One patient on infliximab (Remicade) whose last infusion occurred 3 weeks before patch testing developed multiple positive reactions. "That mirrors what I’ve been perceiving in clinical practice," he said.

Use of methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors such as Remicade or etanercept (Enbrel) should not prevent patch testing. "I’ve had no problem patch testing people on methotrexate," Dr. Fowler said.

The report did not include antihistamines, which also are not a barrier to patch testing. "Other docs, allergists especially, tell patients they can’t take antihistamines when they’re being patch tested," he explained. "They may not be able to take antihistamines and get a good scratch test result, but remember in patch testing you’re looking at a T cell–mediated process. Antihistamines have essentially no effect on that."

Dr. Fowler has been a consultant, speaker, or researcher for Coria, Galderma, Graceway, Hyland, Johnson & Johnson, Quinnova, Ranbaxy, Shire, Stiefel, Triax, UCB, Medicis, Novartis, Abbott, Taro, Allerderm, Allergan, Amgen, Astellas, Centocor, Dermik, Dow, Genentech, Taisho, and 3M.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Immunosuppressive drug therapy is not an absolute contraindication for allergy patch testing, according to Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr.

A recent report on 11 patients who underwent patch testing while on a variety of systemic immunosuppressive drugs suggested patch testing may be more successful than many clinicians think, Dr. Fowler said. Speaking at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF), he fleshed out the findings with advice from his own experience in patch testing patients on immunosuppressives.

The retrospective chart review included patients on prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or infliximab (Dermatitis 2009;20:265-70).

All but one of the patients who were taking 10 mg/day of prednisone had positive patch test reactions, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.) and president of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group.

"In the past, we had thought that about 10 mg/day was the maximum" prednisone dose that could still allow successful patch testing, but this belief was based on extrapolations of animal studies and case reports, with no hard data, he said. "I have personally seen patients who are on higher doses of prednisone produce good positive reactions."

Ideally, though, it’s best to patch test when patients are off prednisone, or on doses of 10 mg/day or less, he added. "If you could get them on every-other-day prednisone dosing, that would be even better."

For an untreated patient with fairly bad dermatitis, especially on the back, Dr. Fowler may treat for 5-7 days with a corticosteroid, perhaps prednisone 40-60 mg/day with no taper, and then stop the corticosteroid for 2-3 days before patch testing. "That’s one way you can get a person clear enough to patch test them if they’re already broken out," he said.

If the patient already is on chronic corticosteroid therapy, he tries to reduce the dose to 10 mg/day or less for several weeks before patch testing.

Dr. Fowler was surprised patients in the report who were being treated with cyclosporine 200 or 300 mg/day all had positive reactions to patch testing. "Generally, we expect cyclosporine to reduce the likelihood of positive reactions because of its broad immunosuppressant effect," he said. "These folks were on relatively low doses, so maybe that was a factor." In his own experience, Dr. Fowler said he has rarely seen positive reactions to patch testing in patients on cyclosporine, "so I think that’s problematic," he added.

One patient on mycophenolate (CellCept) 2 g/day had a negative result when patch tested but then stopped the drug and had a positive reaction on repeat patch testing. "That would suggest that the CellCept suppressed reactions," Dr. Fowler said. He advised not patch testing patients who are on CellCept, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, or azathioprine if at all possible.

One patient on infliximab (Remicade) whose last infusion occurred 3 weeks before patch testing developed multiple positive reactions. "That mirrors what I’ve been perceiving in clinical practice," he said.

Use of methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitors such as Remicade or etanercept (Enbrel) should not prevent patch testing. "I’ve had no problem patch testing people on methotrexate," Dr. Fowler said.

The report did not include antihistamines, which also are not a barrier to patch testing. "Other docs, allergists especially, tell patients they can’t take antihistamines when they’re being patch tested," he explained. "They may not be able to take antihistamines and get a good scratch test result, but remember in patch testing you’re looking at a T cell–mediated process. Antihistamines have essentially no effect on that."

Dr. Fowler has been a consultant, speaker, or researcher for Coria, Galderma, Graceway, Hyland, Johnson & Johnson, Quinnova, Ranbaxy, Shire, Stiefel, Triax, UCB, Medicis, Novartis, Abbott, Taro, Allerderm, Allergan, Amgen, Astellas, Centocor, Dermik, Dow, Genentech, Taisho, and 3M.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Elsevier.

LAS VEGAS – Immunosuppressive drug therapy is not an absolute contraindication for allergy patch testing, according to Dr. Joseph F. Fowler Jr.

A recent report on 11 patients who underwent patch testing while on a variety of systemic immunosuppressive drugs suggested patch testing may be more successful than many clinicians think, Dr. Fowler said. Speaking at the seminar sponsored by Skin Disease Education Foundation (SDEF), he fleshed out the findings with advice from his own experience in patch testing patients on immunosuppressives.

The retrospective chart review included patients on prednisone, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or infliximab (Dermatitis 2009;20:265-70).

All but one of the patients who were taking 10 mg/day of prednisone had positive patch test reactions, said Dr. Fowler of the University of Louisville (Ky.) and president of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group.

"In the past, we had thought that about 10 mg/day was the maximum" prednisone dose that could still allow successful patch testing, but this belief was based on extrapolations of animal studies and case reports, with no hard data, he said. "I have personally seen patients who are on higher doses of prednisone produce good positive reactions."

Ideally, though, it’s best to patch test when patients are off prednisone, or on doses of 10 mg/day or less, he added. "If you could get them on every-other-day prednisone dosing, that would be even better."

For an untreated patient with fairly bad dermatitis, especially on the back, Dr. Fowler may treat for 5-7 days with a corticosteroid, perhaps prednisone 40-60 mg/day with no taper, and then stop the corticosteroid for 2-3 days before patch testing. "That’s one way you can get a person clear enough to patch test them if they’re already broken out," he said.

If the patient already is on chronic corticosteroid therapy, he tries to reduce the dose to 10 mg/day or less for several weeks before patch testing.

Dr. Fowler was surprised patients in the report who were being treated with cyclosporine 200 or 300 mg/day all had positive reactions to patch testing. "Generally, we expect cyclosporine to reduce the likelihood of positive reactions because of its broad immunosuppressant effect," he said. "These folks were on relatively low doses, so maybe that was a factor." In his own experience, Dr. Fowler said he has rarely seen positive reactions to patch testing in patients on cyclosporine, "so I think that’s problematic," he added.