User login

Status Epilepticus in Pregnancy

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

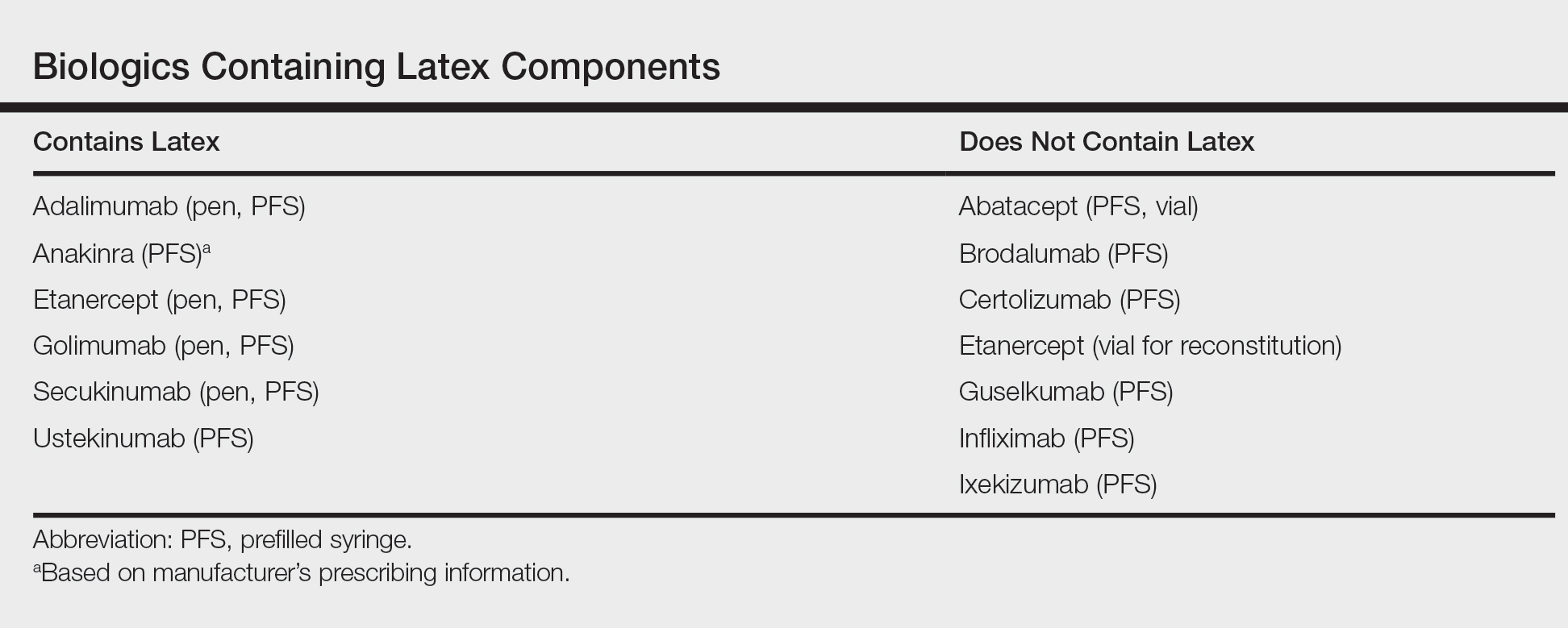

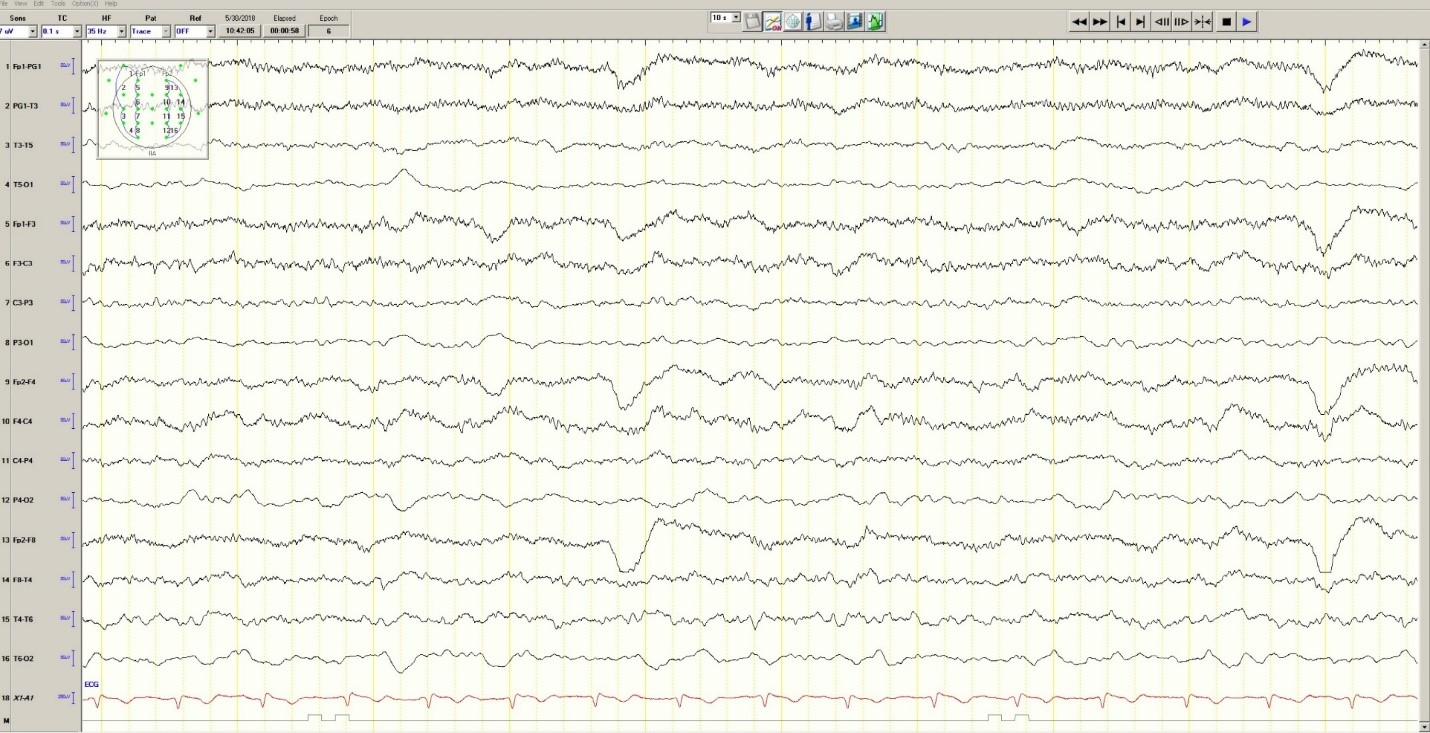

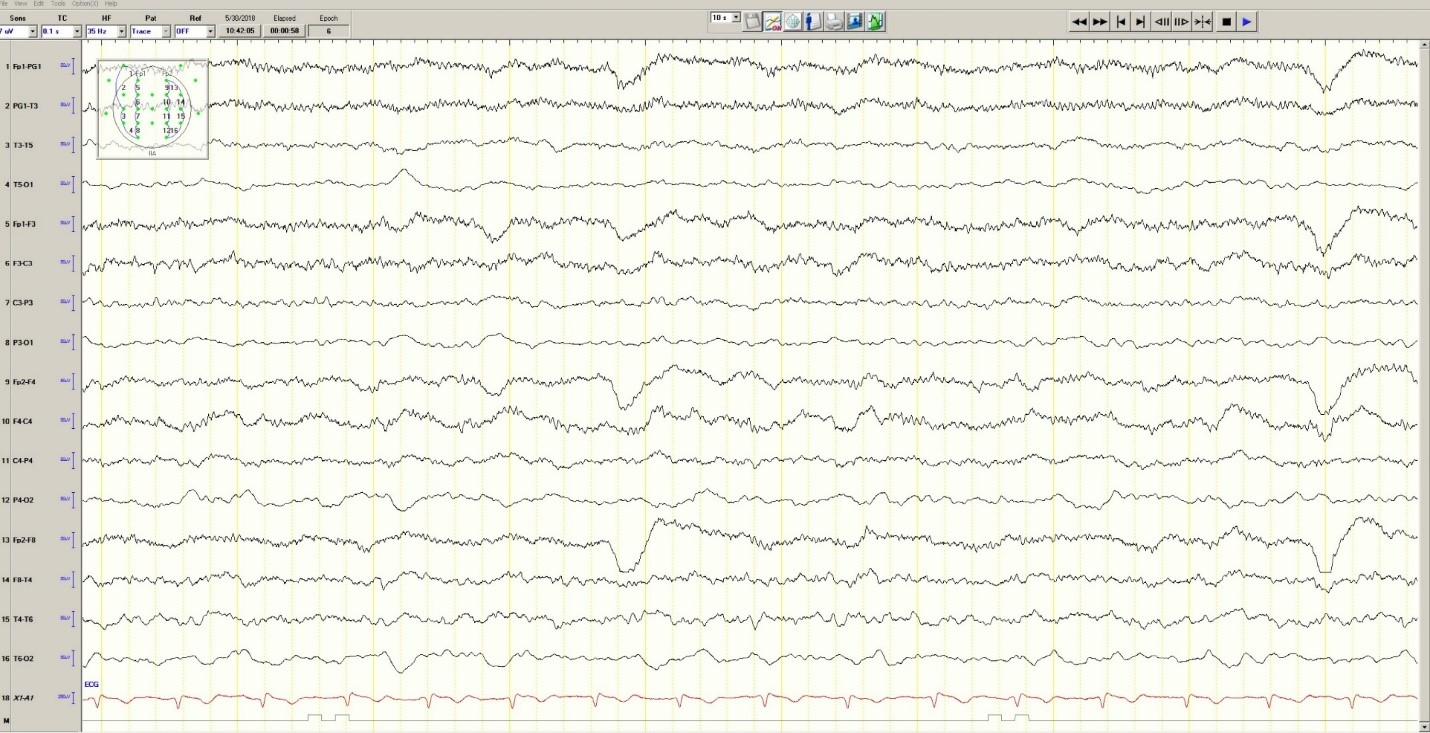

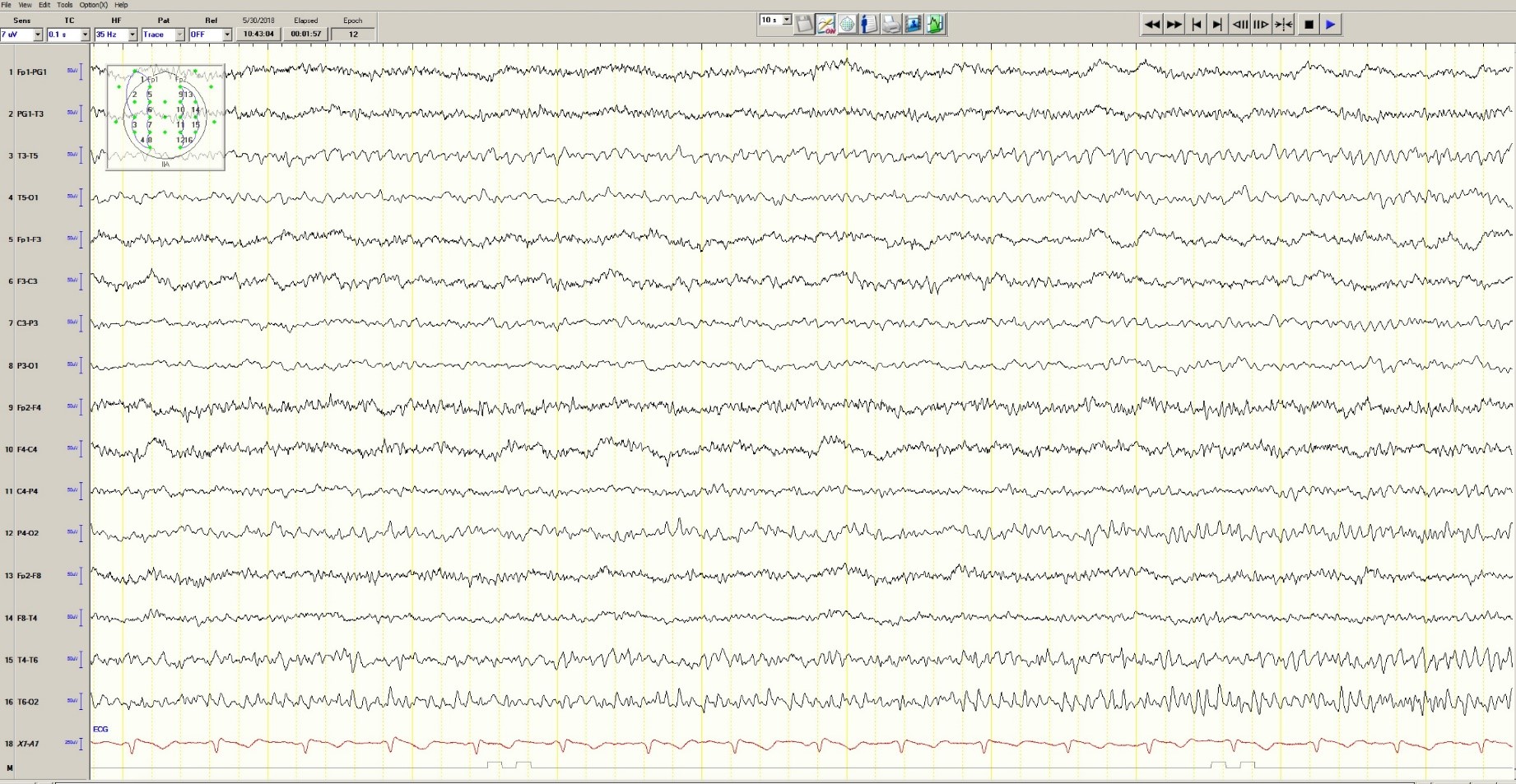

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

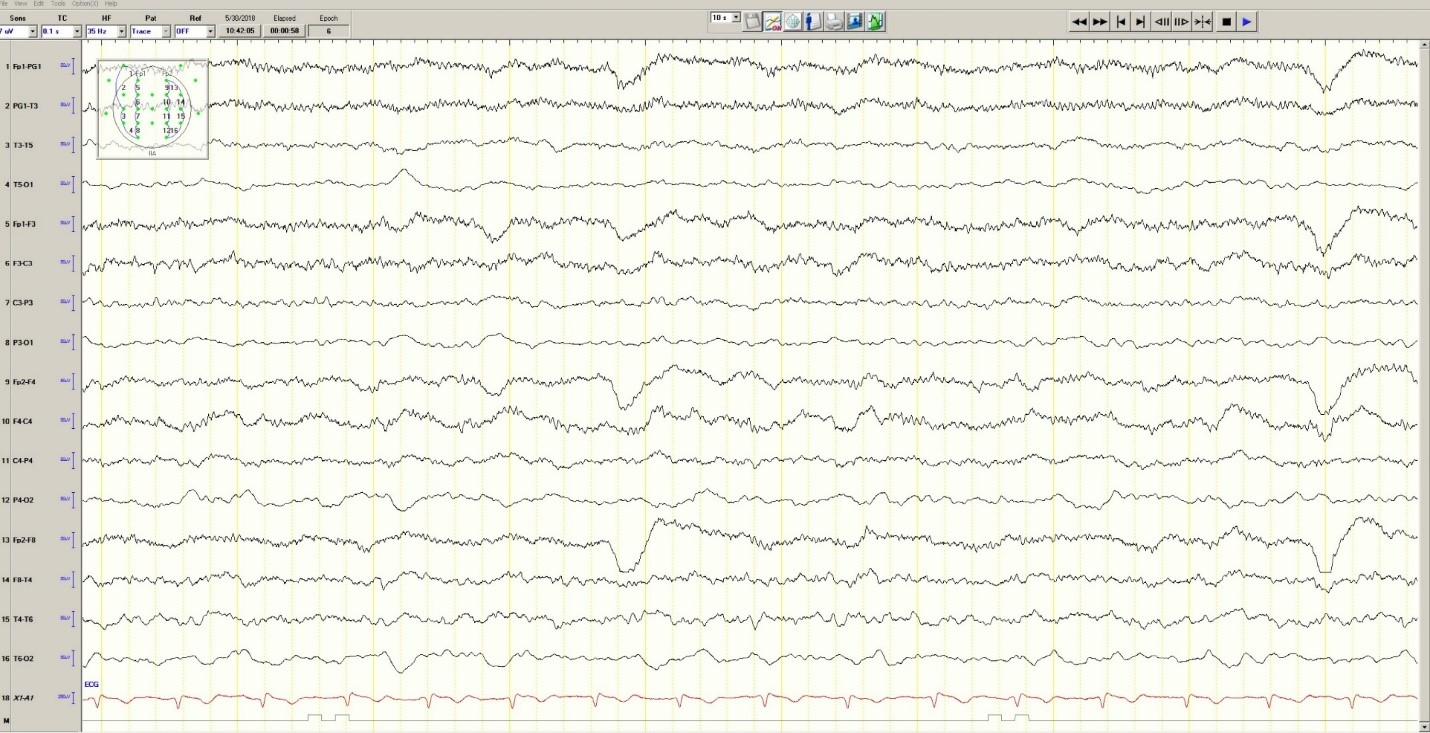

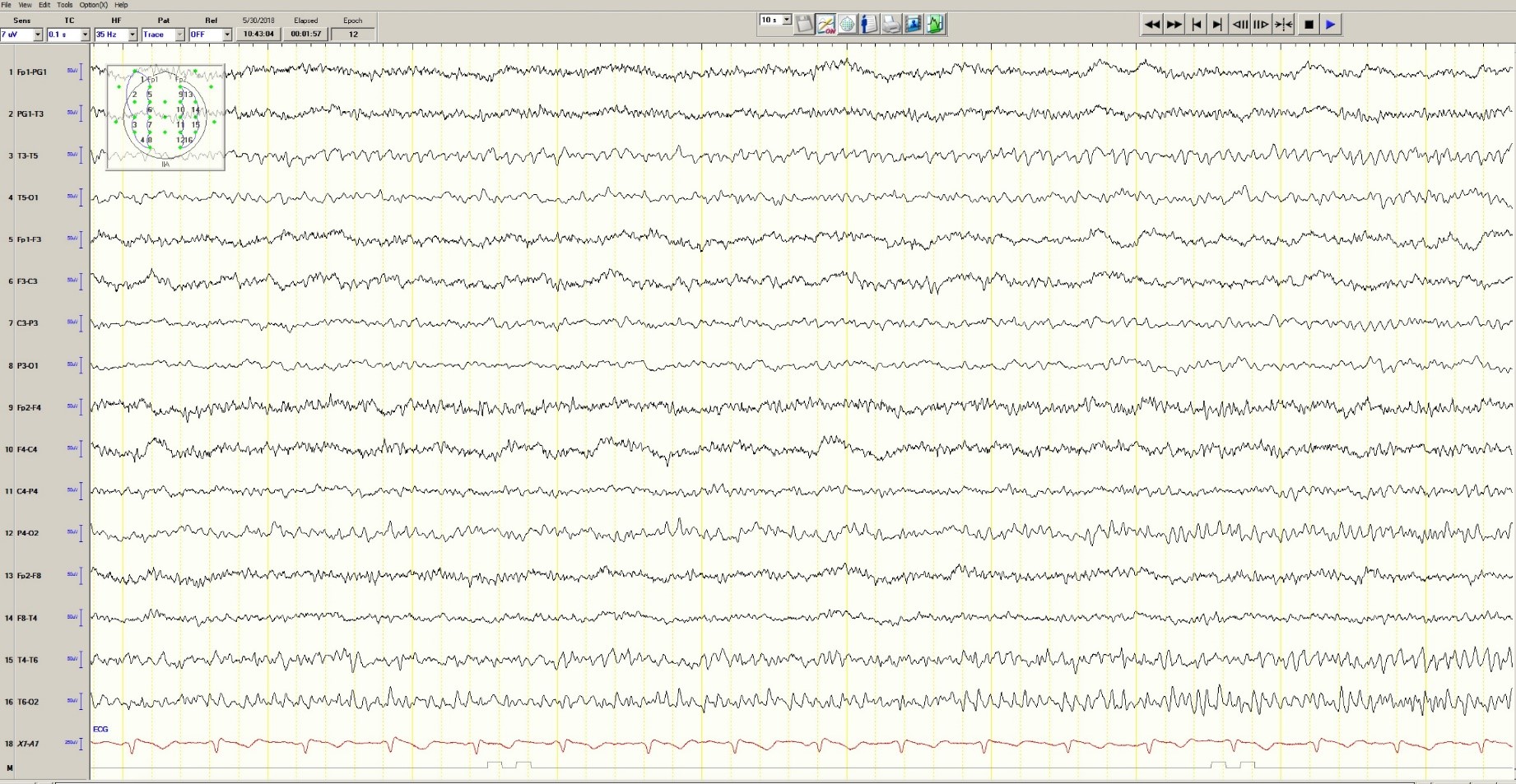

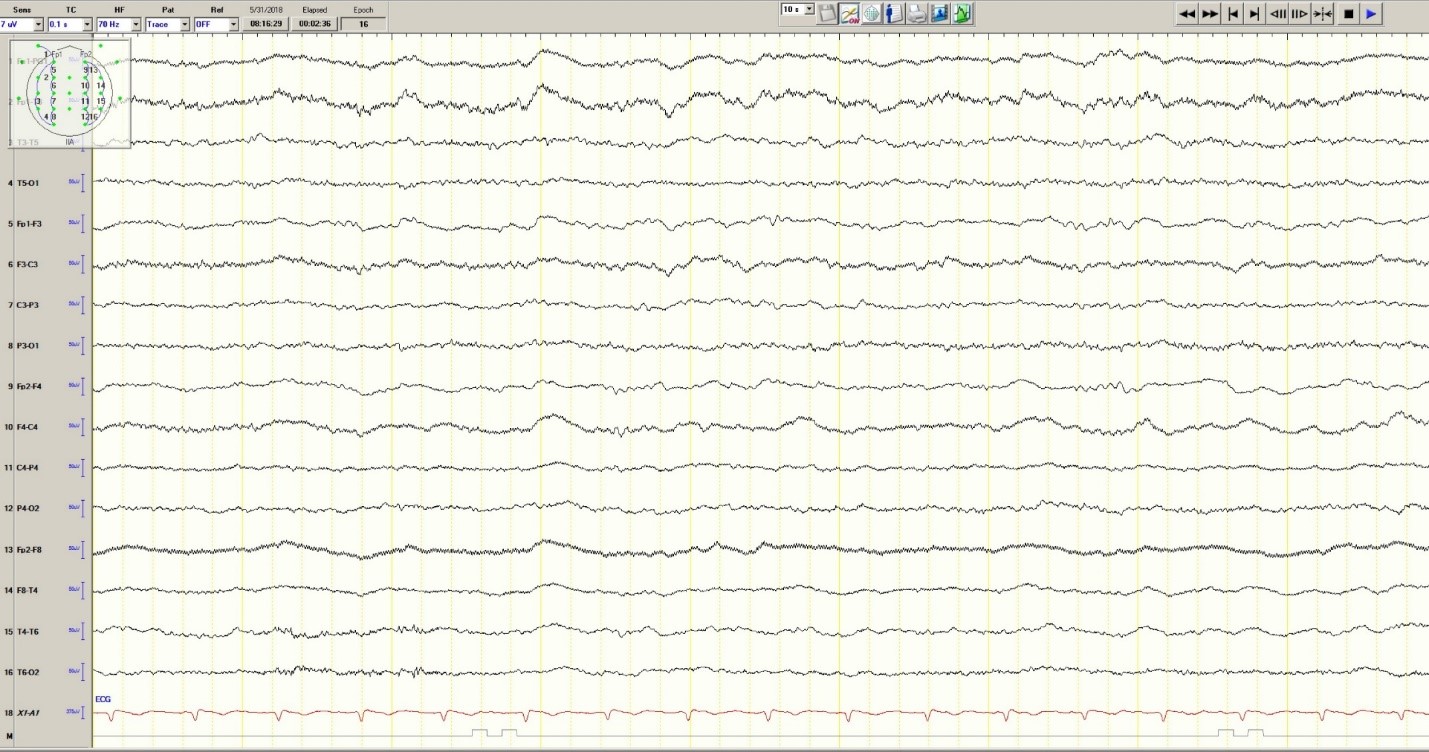

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

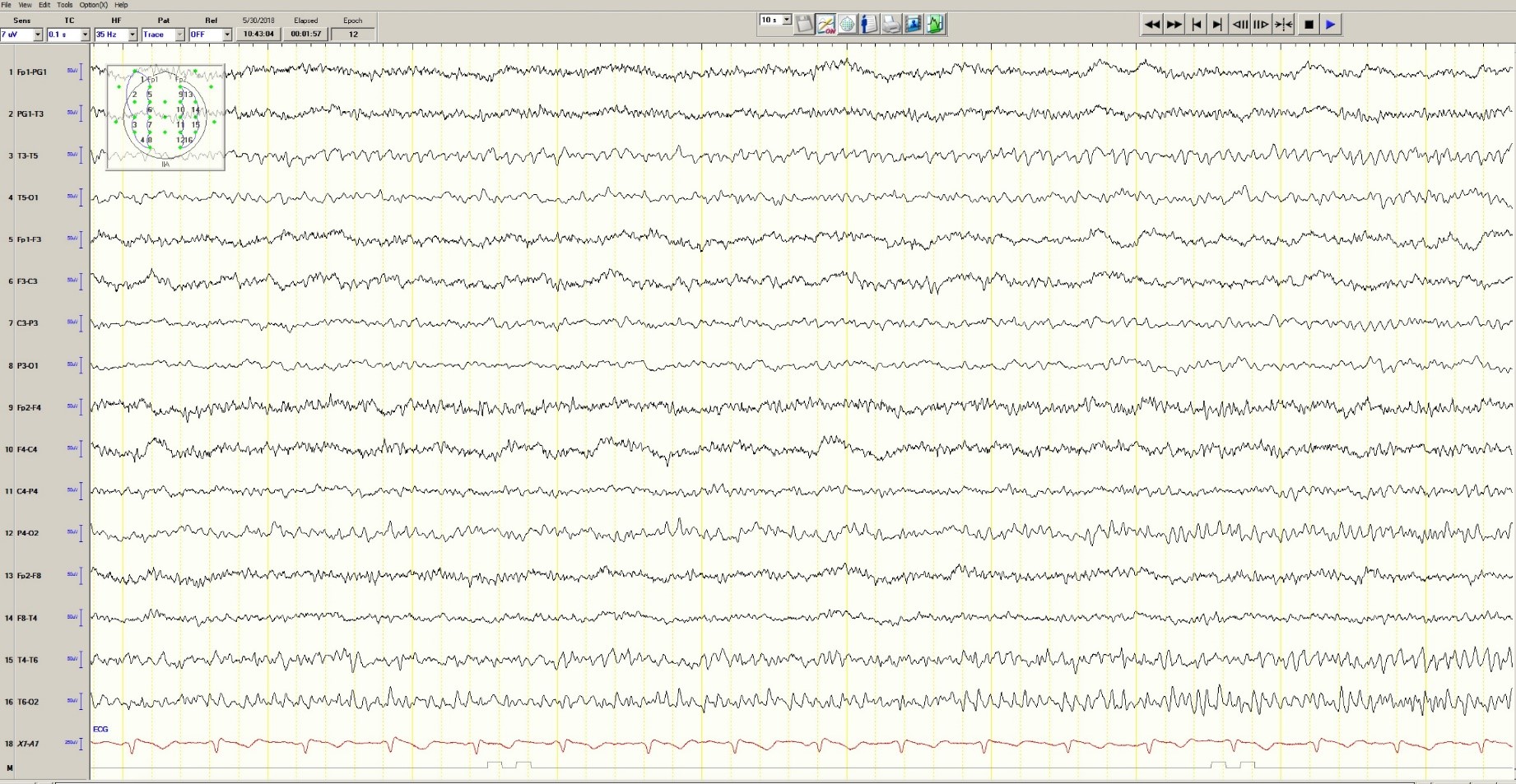

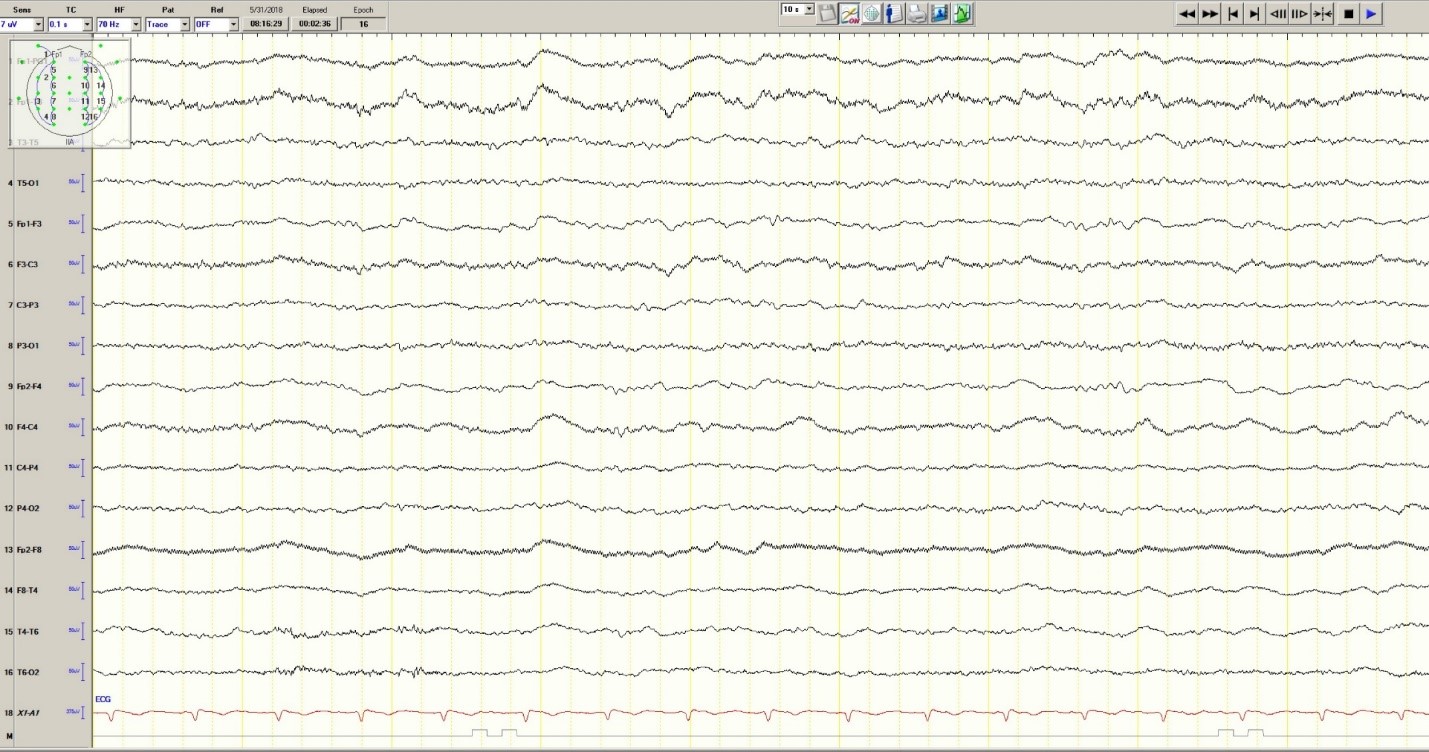

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Latex Hypersensitivity to Injection Devices for Biologic Therapies in Psoriasis Patients

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

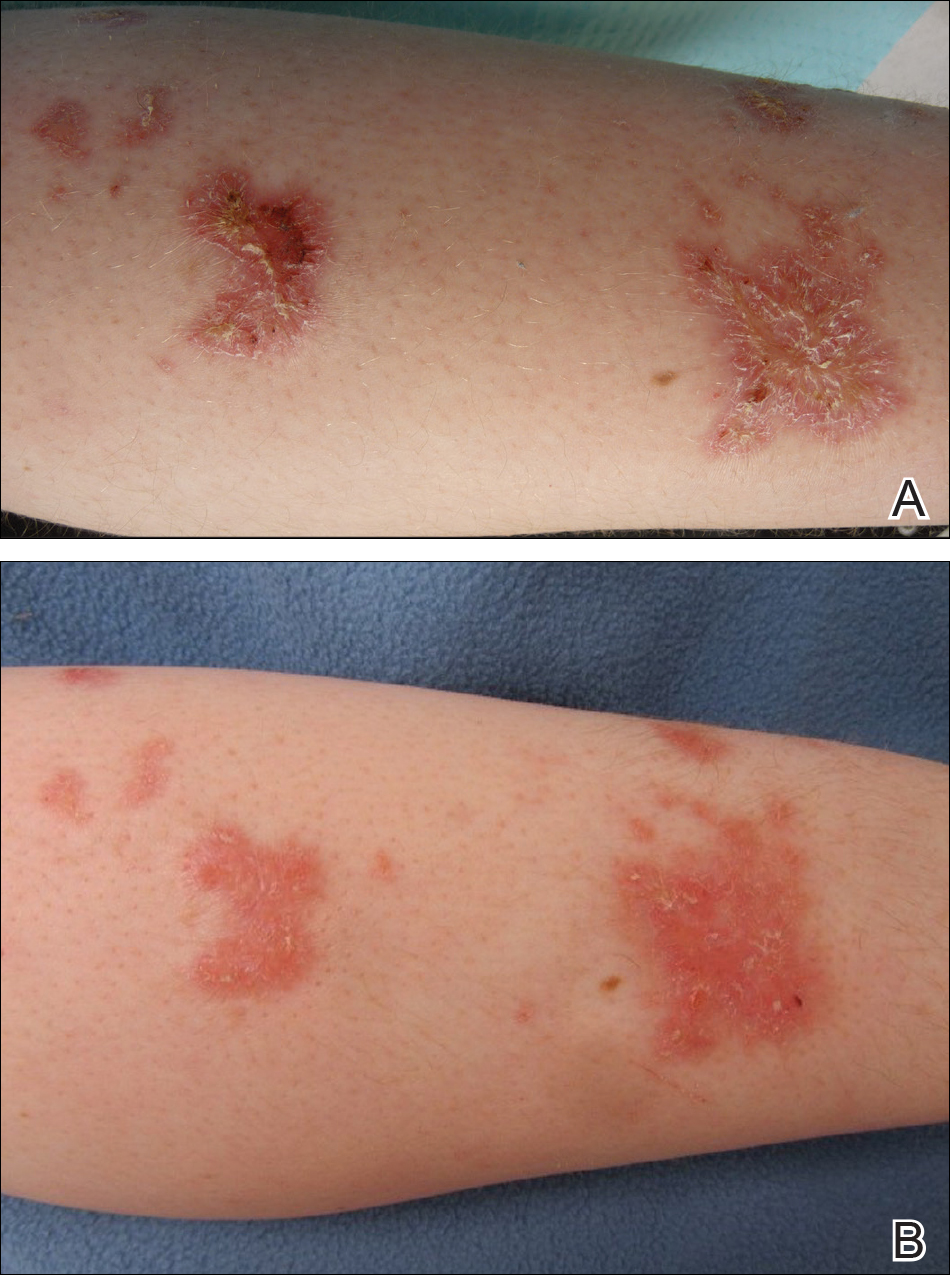

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

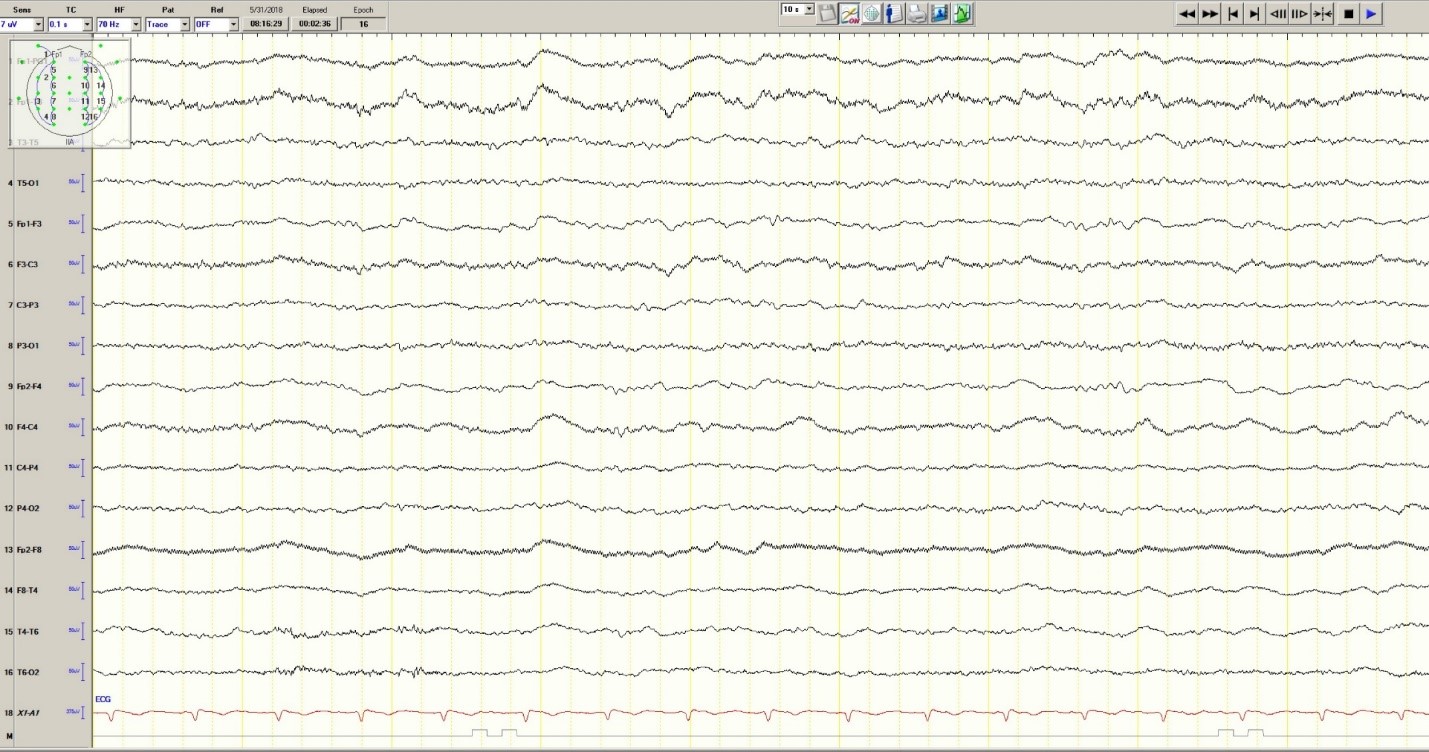

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus Responsive to 308-nm Excimer Laser Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

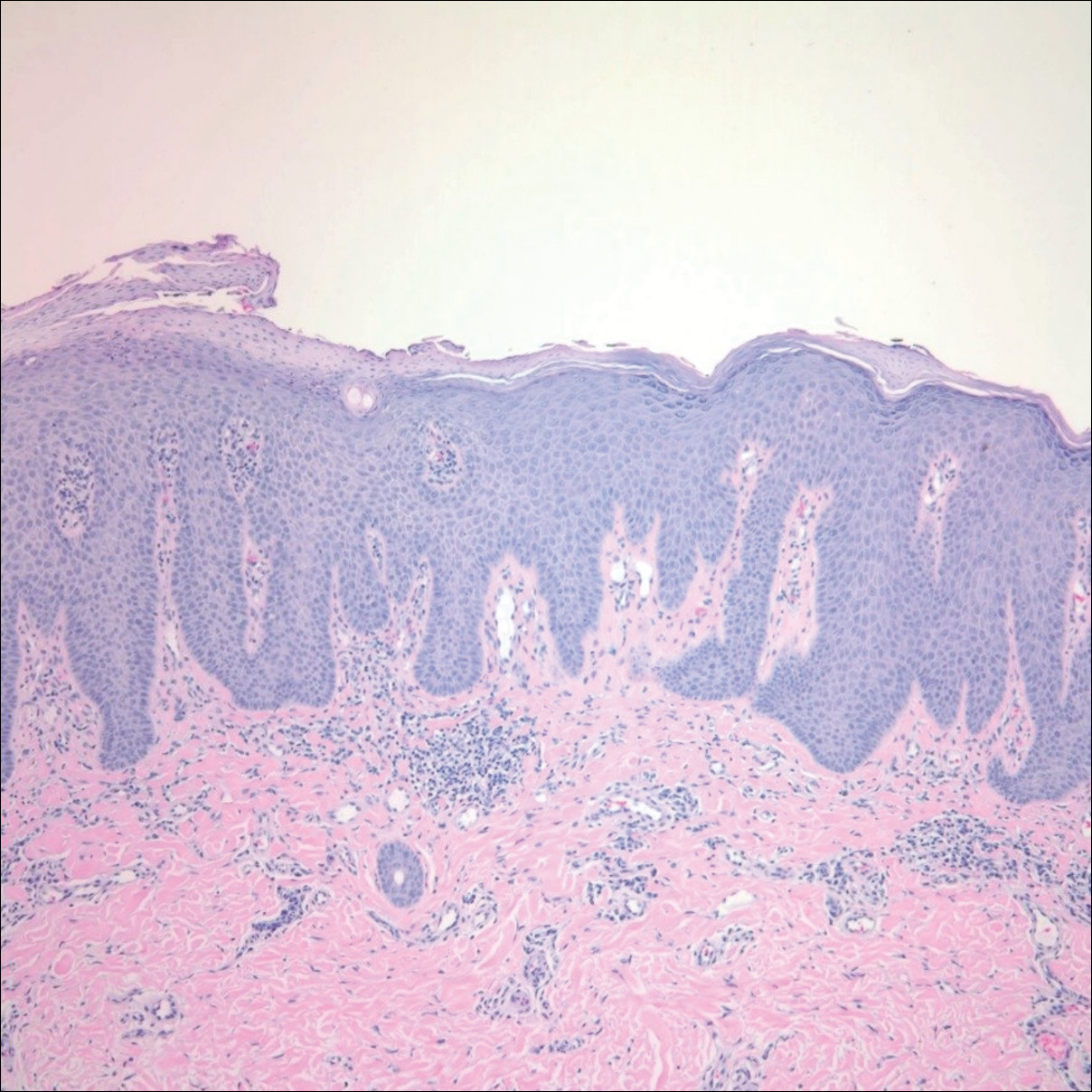

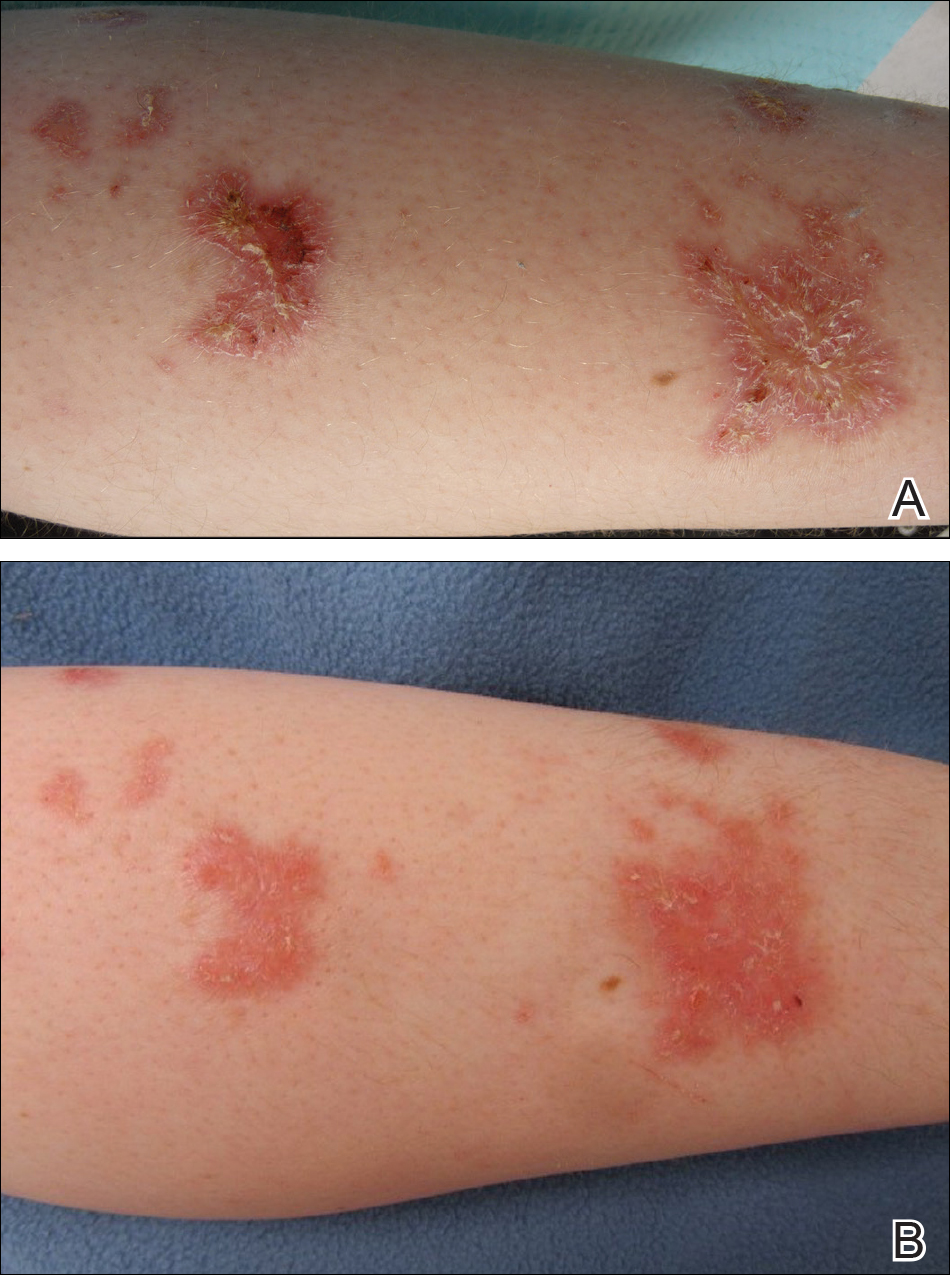

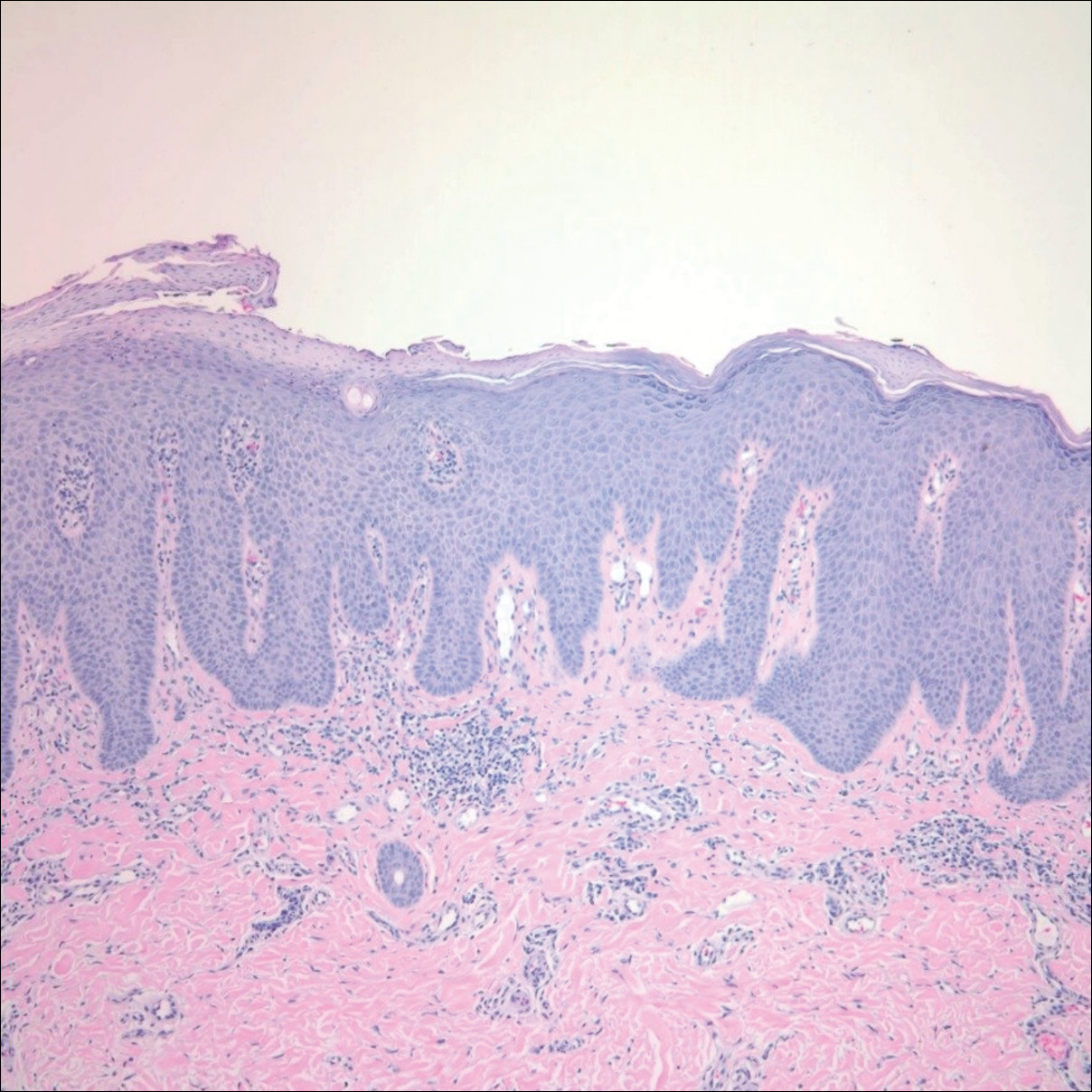

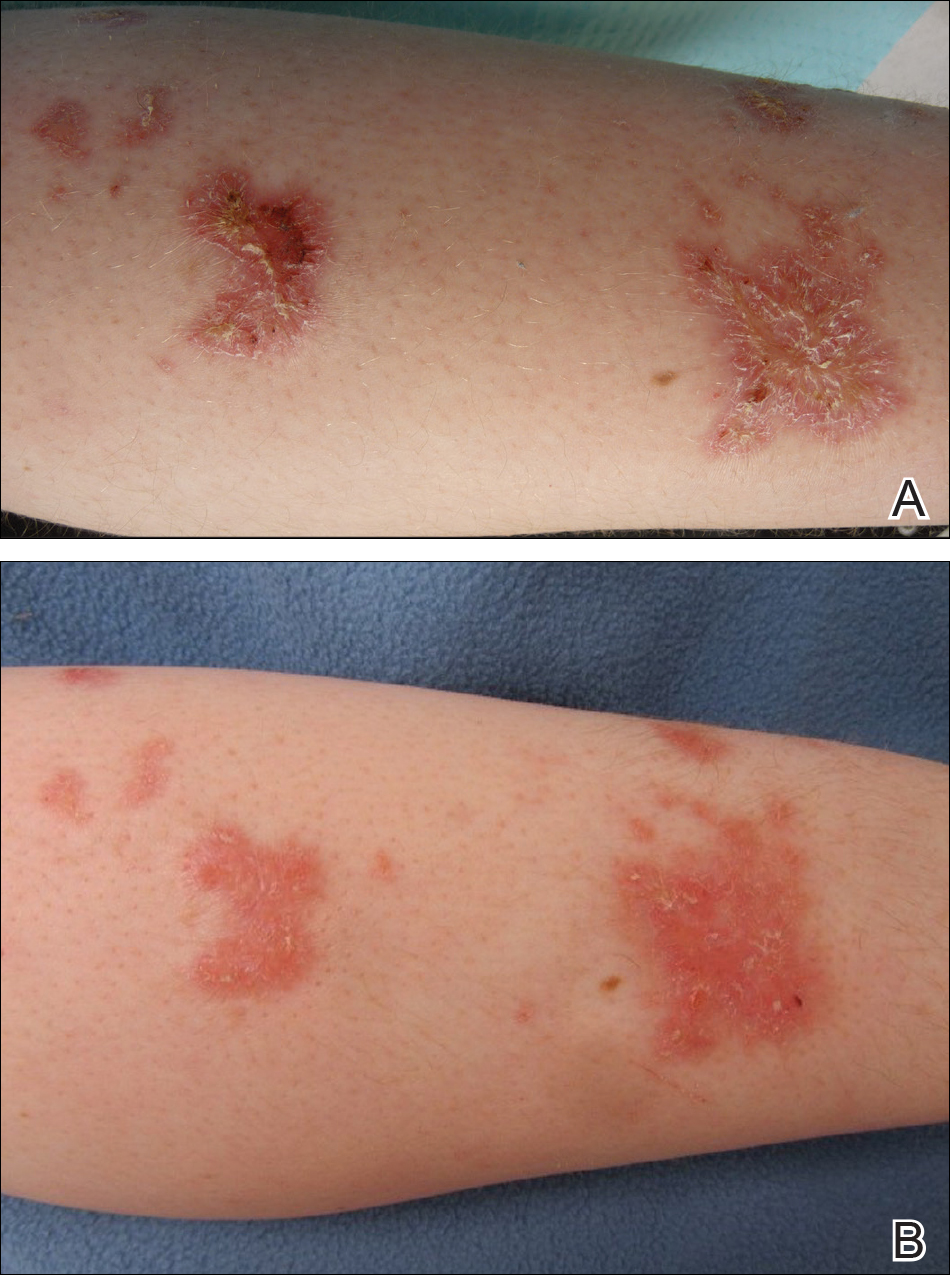

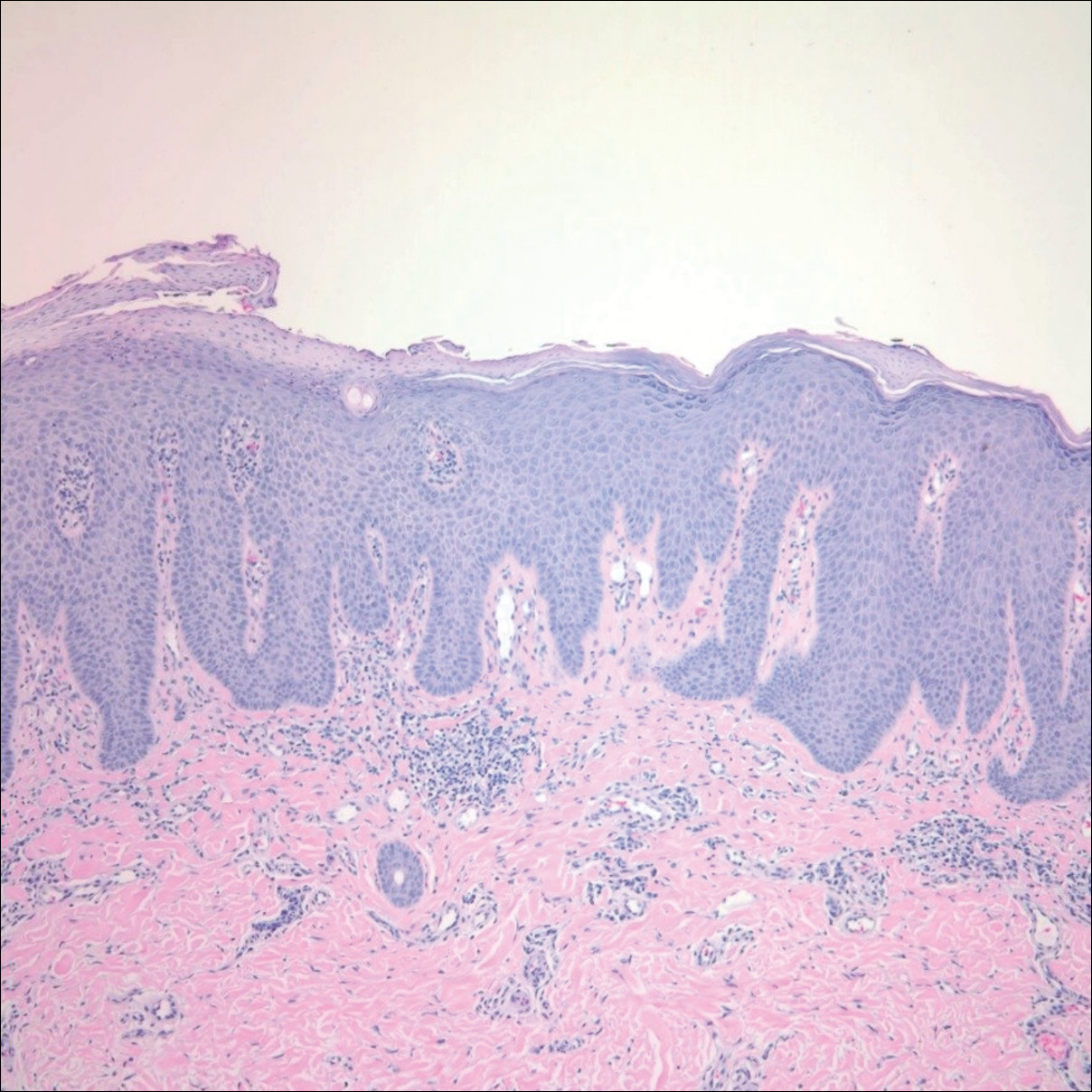

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis

Despite the histopathologic overlap with psoriasis, ILVEN exhibits fewer Ki-67-positive keratinocyte nuclei (proliferative marker) and more cytokeratin 10-positive cells (epidermal differentiation marker) than psoriasis.16 Furthermore, ILVEN has demonstrated fewer CD4−, CD8−, CD45RO−, CD2−, CD25−, CD94−, and CD161+ cells within the dermis and epidermis than psoriasis.16

The clinical presentations of ILVEN and psoriasis may be similar, as some patients with linear psoriasis also present with psoriatic plaques along the lines of Blaschko.17 Additionally, ILVEN may be a precursor to psoriasis. Altman and Mehregan1 found that ILVEN patients who developed psoriasis did so in areas previously affected by ILVEN; however, they continued to distinguish the 2 pathologies as distinct entities. Another early report also hypothesized that the dermoepidermal defect caused by epidermal nevi provided a site for the development of psoriatic lesions because of the Koebner phenomenon.18

Patients with ILVEN also have been found to have extracutaneous manifestations and symptoms commonly seen in psoriasis patients. A 2012 retrospective review revealed that 37% (7/19) of patients with ILVEN also had psoriatic arthritis, cutaneous psoriatic lesions, and/or nail pitting. The authors concluded that ILVEN may lead to the onset of psoriasis later in life and may indicate an underlying psoriatic predisposition.19 Genetic theories also have been proposed, stating that ILVEN may be a mosaic of psoriasis2 or that a postzygotic mutation leads to the predisposition for developing psoriasis.20

Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus frequently is refractory to treatment; however, the associated pruritus and distressing cosmesis make treatment attempts worthwhile.11 No single therapy has been found to be successful in all patients. A widely used first-line treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the former typically used with occlusion.13 Other treatments include adalimumab, calcipotriol,22,23 tretinoin,24 and 5-fluorouracil.24 Physical modalities such as cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, and dermabrasion have been reported with varying success.15,24 Surgical treatments include tangential25 and full-thickness excisions.26

The CO2 laser also has demonstrated success. One study showed considerable improvement of pruritus and partial resolution of lesions only 5 weeks following a single CO2 laser treatment.5 Another study showed promising results when combining CO2 pulsed laser therapy with fractional CO2 laser treatment.6 Other laser therapies including the argon27 and flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye lasers8 have been used with limited success. The use of light therapy and lasers in psoriasis have now increased the treatment options for ILVEN based on the rationale of their shared histopathologic characteristics. Photodynamic therapy also has been attempted because of its successful use in psoriasis patients. It has been found to be successful in diminishing ILVEN lesions and associated pruritus after a few weeks of therapy; however, treatment is limited by the associated pain and requirement for local anesthesia.28

The excimer laser is a form of targeted phototherapy that emits monochromatic light at 308 nm.29 It is ideal for inflammatory skin lesions because the UVB light induces apoptosis.30 Psoriasis lesions treated with the excimer laser show a decrease in keratinocyte proliferation, which in turn reverses epidermal acanthosis and causes T-cell depletion due to upregulation of p53.29,31 This mechanism of action addresses the overproliferation of keratinocytes mediated by T cells in psoriasis and contributes to the success of excimer laser treatment.31 A considerable advantage is its localized treatment, resulting in lower cumulative doses of UVB and reducing the possible carcinogenic and phototoxic risks of whole-body phototherapy.32

One study examined the antipruritic effects of the excimer laser following the treatment of epidermal hyperinnervation leading to intractable pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. The researchers suggested that a potential explanation for the antipruritic effect of the excimer laser may be secondary to nerve degeneration.33 Additionally, low doses of UVB light also may inhibit mast cell degranulation and prevent histamine release, further supporting the antipruritic properties of excimer laser.34

In our patient, failed treatment with other modalities led to trial of excimer laser therapy because of the overlapping clinical and histopathologic findings with psoriasis. Excimer laser improved the clinical appearance and overall texture of the ILVEN lesions and decreased pruritus. The reasons for treatment success may be two-fold. By decreasing the number of keratinocytes and mast cells, the excimer laser may have improved the epidermal hyperplasia and pruritus in the ILVEN lesions. Alternatively, because the patient had ILVEN lesions since infancy, psoriasis may have developed in the location of the ILVEN lesions due to koebnerization, resulting in the clinical response to excimer therapy; however, she had no other clinical evidence of psoriasis.

Because of the recalcitrance of ILVEN lesions to conventional therapies, it is important to investigate therapies that may be of possible benefit. Our novel case documents successful use of the excimer laser in the treatment of ILVEN.

Conclusion

Our case of ILVEN in a woman that had been present since infancy highlights the disease pathology as well as a potential new treatment modality. The patient was refractory to first-line treatments and was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient was subsequently treated with a trial of a 308-nm excimer laser with clinical improvement of the lesions. It is possible that the similarity of ILVEN and psoriasis may have contributed to the clinical improvement in our patient, but the mechanism of action remains unknown. Due to the paucity of evidence regarding optimal treatment of ILVEN, the current case offers dermatologists an option for patients who are refractory to other treatments.

- Altman J, Mehregan AH. Inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:385-389.

- Hofer T. Does inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus represent a segmental type 1/type 2 mosaic of psoriasis? Dermatology. 2006;212:103-107.

- Rogers M, McCrossin I, Commens C. Epidermal nevi and the epidermal nevus syndrome: a review of 131 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:476-488.

- Khachemoune A, Janjua S, Guldbakke K. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report and short review of the literature. Cutis. 2006;78:261-267.

- Ulkur E, Celikoz B, Yuksel F, et al. Carbon dioxide laser therapy for an inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: a case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:428-430.

- Conti R, Bruscino N, Campolmi P, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: why a combined laser therapy. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:242-245.

- Alonso-Castro L, Boixeda P, Reig I, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of epidermal nevi: response and long-term follow-up. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:910-918.

- Alster TS. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successful treatment with the 585 nm flashlamp-pumped dye laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:513-514.

- Kruse LL. Differential diagnosis of linear eruptions in children. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44:194-198.

- Renner R, Colsman A, Sticherling M. ILVEN: is it psoriasis? debate based on successful treatment with etanercept. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:631-632.

- Lee SH, Rogers M. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevi: a review of 23 cases. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:252-256.

- Ito M, Shimizu N, Fujiwara H, et al. Histopathogenesis of inflammatory linear verrucose epidermal nevus: histochemistry, immunohistochemistry and ultrastructure. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283:491-499.

- Cerio R, Jones EW, Eady RA. ILVEN responding to occlusive potent topical steroid therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:279-281.

- Kawaguchi H, Takeuchi M, Ono H, et al. Adult onset of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. J Dermatol. 1999;26:599-602.

- Behera B, Devi B, Nayak BB, et al. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: successfully treated with full thickness excision and skin grafting. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:461-463.

- Vissers WH, Muys L, Erp PE, et al. Immunohistochemical differentiation between ILVEN and psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:216-220.

- Agarwal US, Besarwal RK, Gupta R, et a. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with psoriasiform histology. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:211.

- Bennett RG, Burns L, Wood MG. Systematized epidermal nevus: a determinant for the localization of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:705-757.

- Tran K, Jao-Tan C, Ho N. ILVEN and psoriasis: a retrospective study among pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB163.

- Happle R. Superimposed linear psoriasis: a historical case revisited. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:1027-1028; discussion 1029.

- Özdemir M, Balevi A, Esen H. An inflammatory verrucous epidermal nevus concomitant with psoriasis: treatment with adalimumab. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:11.

- Zvulunov A, Grunwald MH, Halvy S. Topical calcipotriol for treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:567-568.

- Gatti S, Carrozzo AM, Orlandi A, et al. Treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus with calcipotriol. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:837-839.

- Fox BJ, Lapins NA. Comparison of treatment modalities for epidermal nevus: a case report and review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1983;9:879-885.

- Pilanci O, Tas B, Ceran F, et al. A novel technique used in the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: tangential excision. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38:1066-1067.

- Lee BJ, Mancini AJ, Renucci J, et al. Full-thickness surgical excision for the treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:285-292.

- Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Laser therapy of verrucous epidermal naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:124-127.

- Parera E, Gallardo F, Toll A, et al. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus successfully treated with methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:253-256.

- Situm M, Bulat V, Majcen K, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253.

- Beggs S, Short J, Rengifo-Pardo M, et al. Applications of the excimer laser: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1201-1211.

- Bianchi B, Campolmi P, Mavilia L, et al. Monochromatic excimer light (308 nm): an immunohistochemical study of cutaneous T cells and apoptosis-related molecules in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:408-413.

- Mudigonda T, Dabade TS, Feldman SR. A review of targeted ultraviolet B phototherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:664-672.

- Kamo A, Tominaga M, Kamata Y, et al. The excimer lamp induces cutaneous nerve degeneration and reduces scratching in a dry-skin mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2977-2984.

- Bulat V, Majcen K, Dzapo A, et al. Benefits of controlled ultraviolet radiation in the treatment of dermatological diseases. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:1249-1253

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis

Despite the histopathologic overlap with psoriasis, ILVEN exhibits fewer Ki-67-positive keratinocyte nuclei (proliferative marker) and more cytokeratin 10-positive cells (epidermal differentiation marker) than psoriasis.16 Furthermore, ILVEN has demonstrated fewer CD4−, CD8−, CD45RO−, CD2−, CD25−, CD94−, and CD161+ cells within the dermis and epidermis than psoriasis.16

The clinical presentations of ILVEN and psoriasis may be similar, as some patients with linear psoriasis also present with psoriatic plaques along the lines of Blaschko.17 Additionally, ILVEN may be a precursor to psoriasis. Altman and Mehregan1 found that ILVEN patients who developed psoriasis did so in areas previously affected by ILVEN; however, they continued to distinguish the 2 pathologies as distinct entities. Another early report also hypothesized that the dermoepidermal defect caused by epidermal nevi provided a site for the development of psoriatic lesions because of the Koebner phenomenon.18

Patients with ILVEN also have been found to have extracutaneous manifestations and symptoms commonly seen in psoriasis patients. A 2012 retrospective review revealed that 37% (7/19) of patients with ILVEN also had psoriatic arthritis, cutaneous psoriatic lesions, and/or nail pitting. The authors concluded that ILVEN may lead to the onset of psoriasis later in life and may indicate an underlying psoriatic predisposition.19 Genetic theories also have been proposed, stating that ILVEN may be a mosaic of psoriasis2 or that a postzygotic mutation leads to the predisposition for developing psoriasis.20

Treatment

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus frequently is refractory to treatment; however, the associated pruritus and distressing cosmesis make treatment attempts worthwhile.11 No single therapy has been found to be successful in all patients. A widely used first-line treatment is topical or intralesional corticosteroids, with the former typically used with occlusion.13 Other treatments include adalimumab, calcipotriol,22,23 tretinoin,24 and 5-fluorouracil.24 Physical modalities such as cryotherapy, electrodesiccation, and dermabrasion have been reported with varying success.15,24 Surgical treatments include tangential25 and full-thickness excisions.26

The CO2 laser also has demonstrated success. One study showed considerable improvement of pruritus and partial resolution of lesions only 5 weeks following a single CO2 laser treatment.5 Another study showed promising results when combining CO2 pulsed laser therapy with fractional CO2 laser treatment.6 Other laser therapies including the argon27 and flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye lasers8 have been used with limited success. The use of light therapy and lasers in psoriasis have now increased the treatment options for ILVEN based on the rationale of their shared histopathologic characteristics. Photodynamic therapy also has been attempted because of its successful use in psoriasis patients. It has been found to be successful in diminishing ILVEN lesions and associated pruritus after a few weeks of therapy; however, treatment is limited by the associated pain and requirement for local anesthesia.28

The excimer laser is a form of targeted phototherapy that emits monochromatic light at 308 nm.29 It is ideal for inflammatory skin lesions because the UVB light induces apoptosis.30 Psoriasis lesions treated with the excimer laser show a decrease in keratinocyte proliferation, which in turn reverses epidermal acanthosis and causes T-cell depletion due to upregulation of p53.29,31 This mechanism of action addresses the overproliferation of keratinocytes mediated by T cells in psoriasis and contributes to the success of excimer laser treatment.31 A considerable advantage is its localized treatment, resulting in lower cumulative doses of UVB and reducing the possible carcinogenic and phototoxic risks of whole-body phototherapy.32

One study examined the antipruritic effects of the excimer laser following the treatment of epidermal hyperinnervation leading to intractable pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. The researchers suggested that a potential explanation for the antipruritic effect of the excimer laser may be secondary to nerve degeneration.33 Additionally, low doses of UVB light also may inhibit mast cell degranulation and prevent histamine release, further supporting the antipruritic properties of excimer laser.34

In our patient, failed treatment with other modalities led to trial of excimer laser therapy because of the overlapping clinical and histopathologic findings with psoriasis. Excimer laser improved the clinical appearance and overall texture of the ILVEN lesions and decreased pruritus. The reasons for treatment success may be two-fold. By decreasing the number of keratinocytes and mast cells, the excimer laser may have improved the epidermal hyperplasia and pruritus in the ILVEN lesions. Alternatively, because the patient had ILVEN lesions since infancy, psoriasis may have developed in the location of the ILVEN lesions due to koebnerization, resulting in the clinical response to excimer therapy; however, she had no other clinical evidence of psoriasis.

Because of the recalcitrance of ILVEN lesions to conventional therapies, it is important to investigate therapies that may be of possible benefit. Our novel case documents successful use of the excimer laser in the treatment of ILVEN.

Conclusion

Our case of ILVEN in a woman that had been present since infancy highlights the disease pathology as well as a potential new treatment modality. The patient was refractory to first-line treatments and was concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the lesions. The patient was subsequently treated with a trial of a 308-nm excimer laser with clinical improvement of the lesions. It is possible that the similarity of ILVEN and psoriasis may have contributed to the clinical improvement in our patient, but the mechanism of action remains unknown. Due to the paucity of evidence regarding optimal treatment of ILVEN, the current case offers dermatologists an option for patients who are refractory to other treatments.

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN) is a rare entity that presents with linear and pruritic psoriasiform plaques and most commonly occurs during childhood. It represents a dysregulation of keratinocytes exhibiting genetic mosaicism.1,2 Epidermal nevi may derive from keratinocytic, follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, or eccrine origin. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is classified under the keratinocytic type of epidermal nevus and represents approximately 6% of all epidermal nevi.3 The condition presents as erythematous and verrucous plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,4 There is a predilection for the legs, and girls are 4 times more commonly affected than boys.1 Cases of ILVEN are predominantly sporadic, though rare familial cases have been reported.4

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is notoriously refractory to treatment. First-line therapies include topical agents such as corticosteroids, calcipotriol, retinoids, and 5-fluorouracil.3,4 Other treatments include intralesional corticosteroids, cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, and surgical excision.3 Several case reports have shown promising results using the pulsed dye and ablative CO2 lasers.5-8

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old woman presented with dry, pruritic, red lesions on the right leg that had been present and stable since she was an infant (2 weeks of age). Her medical history included acne vulgaris, but she denied any personal or family history of psoriasis as well as any arthralgia or arthritis. Physical examination revealed discrete, oval, hyperkeratotic, scaly, red plaques on the lateral right leg with a larger hyperkeratotic, linear, red plaque extending from the right popliteal fossa to the posterior thigh (Figure 1A). The nails, scalp, buttocks, and upper extremities were unaffected. Bacterial culture of the right leg demonstrated Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Biopsy of the right popliteal fossa showed psoriasiform dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia, a slightly verruciform surface, broad zones of superficial pallor, and parakeratosis with conspicuous colonies of bacteria (Figure 2).

Following the positive bacterial culture, the patient was treated with a short course of oral doxycycline, which did not alter the clinical appearance of the lesions or improve symptoms of pruritus. Pruritus improved moderately with topical corticosteroid treatment, but clinically the lesions appeared unchanged. The plaque on the superior right leg was treated with a superpulsed CO2 laser and the plaque on the inferior right leg was treated with a fractional CO2 laser, both with minimal improvement.

Because of the clinical and histopathologic similarities of the patient's lesions to psoriasis, a trial of the UV 308-nm excimer laser was initiated. Following initial test spots, she completed a total of 18 treatments to all lesions with noticeable clinical improvement (Figure 1B). Initially, the patient returned for treatment biweekly for approximately 5 weeks with 2 small spots being targeted at each session, with an average surface area of approximately 16 cm2. She was started at 225 mJ/cm2 with 25% increases at each session and ultimately reached up to 1676 mJ/cm2 at the end of the 10 sessions. She tolerated the procedure well with some minor blistering. Treatment was deferred for 3 months due to the patient's schedule, then biweekly treatments resumed for 4 weeks, totaling 8 more sessions. At that time, all lesions on the right leg were targeted, with an average surface area of approximately 100 cm2. The laser settings were initiated at 225 mJ/cm2 with 20% increases at each session and ultimately reached 560 mJ/cm2. The treatment was well tolerated throughout; however, the patient initially reported residual pruritus. The plaques continued to improve, and most notably, there was thinning of the hyperkeratotic scale of the plaques in addition to decreased erythema and complete resolution of pruritus. Ultimately, treatment was discontinued because of lack of insurance coverage and financial burden. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Presentation

Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus is a rare type of keratinocytic epidermal nevus4 that clinically presents as small, discrete, pruritic, scaly plaques coalescing into a linear plaque along the lines of Blaschko.9 Considerable pruritus and resistance to treatment are hallmarks of the disease.10 Histopathologically, ILVEN is characterized by alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with a lack of neutrophils in an acanthotic epidermis.11-13 Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus presents at birth or in early childhood. Adult onset is rare.9,14 Approximately 75% of lesions present by 5 years of age, with a majority occurring within the first 6 months of life.15 The differential diagnosis includes linear psoriasis, epidermal nevi, linear lichen planus, linear verrucae, linear lichen simplex chronicus, and mycosis fungoides.4,11

Differentiation From Psoriasis