User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Unsubsidized enrollees leaving insurance exchanges

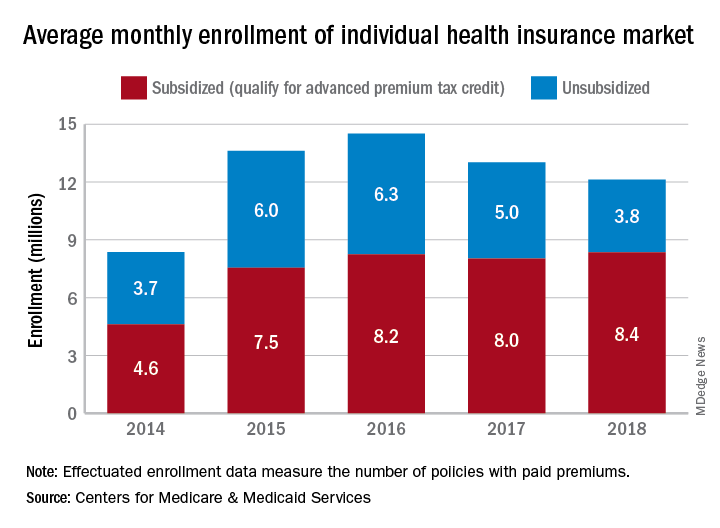

Both overall and unsubsidized enrollment in the various state and federal health insurance exchanges dropped in 2018, but new data on payments for those policies show that more people paid their premiums in 2019, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The number of policies selected with the individual insurance exchanges in late 2018 for which premiums were paid in February 2019 (termed the effectuated enrollment) was almost 10.6 million, or more than 92% of the 11.4 million plans selected during open enrollment, CMS reported. For February 2018, effectuated enrollment was just over 10.5 million, which represented 89.5% of the nearly 11.8 million policies selected during the previous open enrollment.

Over the longer term, the trend has been a rise and a fall as average monthly effectuated enrollment peaked in 2016 and dropped 16.5% by 2018, CMS data show.

A look at the advance premium tax credit (APTC) provides some insight into that decline. The population subsidized by the APTC has been fairly stable since 2016 – effectuated enrollment rose by just over 1% – but the number of unsubsidized enrollees has dropped 40% as 2.5 million people who did not qualify for the APTC left the market, the CMS said.

From 2017 to 2018, there were 47 states with declines in unsubsidized enrollment, with 9 states losing more than 40% of such enrollees. The largest drop in the unsubsidized population (85%) came in Iowa, while Alaska’s 7% gain was the largest increase, the CMS reported.

“As President Trump predicted, people are fleeing the individual market. Obamacare is failing the American people, and the ongoing exodus of the unsubsidized population from the market proves that Obamacare’s sky-high premiums are unaffordable,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a written statement.

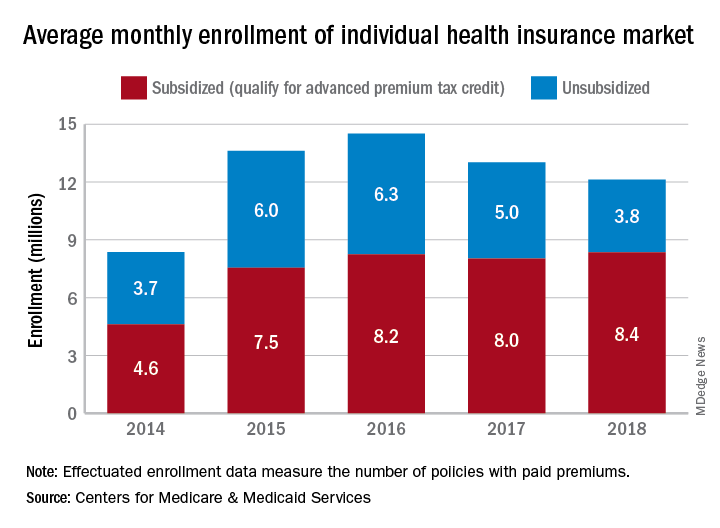

Both overall and unsubsidized enrollment in the various state and federal health insurance exchanges dropped in 2018, but new data on payments for those policies show that more people paid their premiums in 2019, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The number of policies selected with the individual insurance exchanges in late 2018 for which premiums were paid in February 2019 (termed the effectuated enrollment) was almost 10.6 million, or more than 92% of the 11.4 million plans selected during open enrollment, CMS reported. For February 2018, effectuated enrollment was just over 10.5 million, which represented 89.5% of the nearly 11.8 million policies selected during the previous open enrollment.

Over the longer term, the trend has been a rise and a fall as average monthly effectuated enrollment peaked in 2016 and dropped 16.5% by 2018, CMS data show.

A look at the advance premium tax credit (APTC) provides some insight into that decline. The population subsidized by the APTC has been fairly stable since 2016 – effectuated enrollment rose by just over 1% – but the number of unsubsidized enrollees has dropped 40% as 2.5 million people who did not qualify for the APTC left the market, the CMS said.

From 2017 to 2018, there were 47 states with declines in unsubsidized enrollment, with 9 states losing more than 40% of such enrollees. The largest drop in the unsubsidized population (85%) came in Iowa, while Alaska’s 7% gain was the largest increase, the CMS reported.

“As President Trump predicted, people are fleeing the individual market. Obamacare is failing the American people, and the ongoing exodus of the unsubsidized population from the market proves that Obamacare’s sky-high premiums are unaffordable,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a written statement.

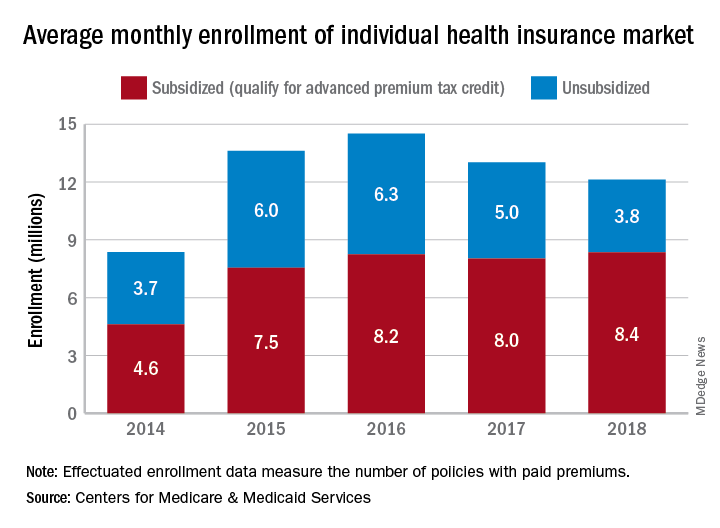

Both overall and unsubsidized enrollment in the various state and federal health insurance exchanges dropped in 2018, but new data on payments for those policies show that more people paid their premiums in 2019, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

The number of policies selected with the individual insurance exchanges in late 2018 for which premiums were paid in February 2019 (termed the effectuated enrollment) was almost 10.6 million, or more than 92% of the 11.4 million plans selected during open enrollment, CMS reported. For February 2018, effectuated enrollment was just over 10.5 million, which represented 89.5% of the nearly 11.8 million policies selected during the previous open enrollment.

Over the longer term, the trend has been a rise and a fall as average monthly effectuated enrollment peaked in 2016 and dropped 16.5% by 2018, CMS data show.

A look at the advance premium tax credit (APTC) provides some insight into that decline. The population subsidized by the APTC has been fairly stable since 2016 – effectuated enrollment rose by just over 1% – but the number of unsubsidized enrollees has dropped 40% as 2.5 million people who did not qualify for the APTC left the market, the CMS said.

From 2017 to 2018, there were 47 states with declines in unsubsidized enrollment, with 9 states losing more than 40% of such enrollees. The largest drop in the unsubsidized population (85%) came in Iowa, while Alaska’s 7% gain was the largest increase, the CMS reported.

“As President Trump predicted, people are fleeing the individual market. Obamacare is failing the American people, and the ongoing exodus of the unsubsidized population from the market proves that Obamacare’s sky-high premiums are unaffordable,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a written statement.

Peripheral nervous system events have lasting impact on SLE patients

Peripheral nervous system disease, predominantly neuropathies, constitutes a substantial proportion of the manifestations of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and has a lasting negative impact on health-related quality of life, John G. Hanly, MD, of Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center and Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and associates reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

According to the study of 1,827 SLE patients who had been recently diagnosed and enrolled in the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) network at sites in Europe, Asia, and North America during 1999-2011, 161 peripheral nervous system (PNS) events occurred in 139 of the patients (8%) over a mean 7.6 years of follow-up.

Using the seven American College of Rheumatology case definitions for PNS disease in neuropsychiatric SLE, most of the events were peripheral neuropathy (41%), mononeuropathy (27%), and cranial neuropathy (24%). For 110 with peripheral neuropathy or mononeuropathy who underwent electrophysiologic testing, axonal damage was often present (42%), followed by demyelination (22%).

The PNS events were attributed to SLE in about 58%-75% of the patients. Based on these data the investigators estimated that after 10 years the cumulative incidence of any PNS event regardless of its attribution was about 9%, and it was nearly 7% for events attributed to SLE.

The probability that the neuropathies would not resolve over time was estimated at about 43% for peripheral neuropathy, 29% for mononeuropathy, and 30% for cranial neuropathy. Resolution of neuropathy was most rapid for cranial neuropathy, followed by mononeuropathy and peripheral neuropathy.

Patients with PNS events had significantly lower physical and mental health component scores on the 36-item Short Form Health Survey than did patients without a neuropsychiatric event up to the study assessment, and these differences persisted for 10 years of follow-up.

These “findings provide a benchmark for the assessment of future treatment modalities,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Hanly JG et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1002/art.41070.

Peripheral nervous system disease, predominantly neuropathies, constitutes a substantial proportion of the manifestations of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and has a lasting negative impact on health-related quality of life, John G. Hanly, MD, of Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center and Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and associates reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

According to the study of 1,827 SLE patients who had been recently diagnosed and enrolled in the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) network at sites in Europe, Asia, and North America during 1999-2011, 161 peripheral nervous system (PNS) events occurred in 139 of the patients (8%) over a mean 7.6 years of follow-up.

Using the seven American College of Rheumatology case definitions for PNS disease in neuropsychiatric SLE, most of the events were peripheral neuropathy (41%), mononeuropathy (27%), and cranial neuropathy (24%). For 110 with peripheral neuropathy or mononeuropathy who underwent electrophysiologic testing, axonal damage was often present (42%), followed by demyelination (22%).

The PNS events were attributed to SLE in about 58%-75% of the patients. Based on these data the investigators estimated that after 10 years the cumulative incidence of any PNS event regardless of its attribution was about 9%, and it was nearly 7% for events attributed to SLE.

The probability that the neuropathies would not resolve over time was estimated at about 43% for peripheral neuropathy, 29% for mononeuropathy, and 30% for cranial neuropathy. Resolution of neuropathy was most rapid for cranial neuropathy, followed by mononeuropathy and peripheral neuropathy.

Patients with PNS events had significantly lower physical and mental health component scores on the 36-item Short Form Health Survey than did patients without a neuropsychiatric event up to the study assessment, and these differences persisted for 10 years of follow-up.

These “findings provide a benchmark for the assessment of future treatment modalities,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Hanly JG et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1002/art.41070.

Peripheral nervous system disease, predominantly neuropathies, constitutes a substantial proportion of the manifestations of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and has a lasting negative impact on health-related quality of life, John G. Hanly, MD, of Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center and Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., and associates reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

According to the study of 1,827 SLE patients who had been recently diagnosed and enrolled in the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) network at sites in Europe, Asia, and North America during 1999-2011, 161 peripheral nervous system (PNS) events occurred in 139 of the patients (8%) over a mean 7.6 years of follow-up.

Using the seven American College of Rheumatology case definitions for PNS disease in neuropsychiatric SLE, most of the events were peripheral neuropathy (41%), mononeuropathy (27%), and cranial neuropathy (24%). For 110 with peripheral neuropathy or mononeuropathy who underwent electrophysiologic testing, axonal damage was often present (42%), followed by demyelination (22%).

The PNS events were attributed to SLE in about 58%-75% of the patients. Based on these data the investigators estimated that after 10 years the cumulative incidence of any PNS event regardless of its attribution was about 9%, and it was nearly 7% for events attributed to SLE.

The probability that the neuropathies would not resolve over time was estimated at about 43% for peripheral neuropathy, 29% for mononeuropathy, and 30% for cranial neuropathy. Resolution of neuropathy was most rapid for cranial neuropathy, followed by mononeuropathy and peripheral neuropathy.

Patients with PNS events had significantly lower physical and mental health component scores on the 36-item Short Form Health Survey than did patients without a neuropsychiatric event up to the study assessment, and these differences persisted for 10 years of follow-up.

These “findings provide a benchmark for the assessment of future treatment modalities,” the investigators concluded.

SOURCE: Hanly JG et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Aug 7. doi: 10.1002/art.41070.

REPORTING FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

FDA approves Wakix for excessive daytime sleepiness

The Food and Drug Administration has approved pitolisant (Wakix) for excessive daytime sleepiness among patients with narcolepsy, according to a release from the drug’s developer.

Approval of this once-daily, selective histamine 3–receptor antagonist/inverse agonist was based on a pair of multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that included a total of 261 patients. Patients in both studies experienced statistically significant improvements in excessive daytime sleepiness according to Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores.

Rates of adverse advents at or greater than 5% and more than double that of placebo included insomnia (6%), nausea (6%), and anxiety (5%). Patients with severe liver disease should not use pitolisant. Pitolisant has not been evaluated in patients under 18 years of age, and patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are encouraged to enroll in a pregnancy exposure registry.

Full prescribing information, including contraindications and warnings, can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved pitolisant (Wakix) for excessive daytime sleepiness among patients with narcolepsy, according to a release from the drug’s developer.

Approval of this once-daily, selective histamine 3–receptor antagonist/inverse agonist was based on a pair of multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that included a total of 261 patients. Patients in both studies experienced statistically significant improvements in excessive daytime sleepiness according to Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores.

Rates of adverse advents at or greater than 5% and more than double that of placebo included insomnia (6%), nausea (6%), and anxiety (5%). Patients with severe liver disease should not use pitolisant. Pitolisant has not been evaluated in patients under 18 years of age, and patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are encouraged to enroll in a pregnancy exposure registry.

Full prescribing information, including contraindications and warnings, can be found on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved pitolisant (Wakix) for excessive daytime sleepiness among patients with narcolepsy, according to a release from the drug’s developer.

Approval of this once-daily, selective histamine 3–receptor antagonist/inverse agonist was based on a pair of multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that included a total of 261 patients. Patients in both studies experienced statistically significant improvements in excessive daytime sleepiness according to Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores.

Rates of adverse advents at or greater than 5% and more than double that of placebo included insomnia (6%), nausea (6%), and anxiety (5%). Patients with severe liver disease should not use pitolisant. Pitolisant has not been evaluated in patients under 18 years of age, and patients who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant are encouraged to enroll in a pregnancy exposure registry.

Full prescribing information, including contraindications and warnings, can be found on the FDA website.

ACP unveils clinical guideline disclosure strategy

The American College of Physicians recently described its methods for developing clinical guidelines and guidance statements, in a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Any person involved in the development of an ACP clinical guideline or guidance statement must disclose all financial and intellectual interests related to health care from the previous 3 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, wrote.

“The goals of our process are to mitigate any actual bias during the development of ACP’s clinical recommendations and to ensure creditability and public trust in our clinical policies by reducing the potential for perceived bias,” noted Robert M. McLean, MD, president of the ACP, in a statement.

This paper’s publication comes on the heels of authors of a Cancer paper having reported that nearly 25% of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s guideline authors who were not exempt from reporting conflicts of interest failed to disclose receiving industry payments.

The ACP committee’s guiding principle for collection of disclosures of interest and management of conflicts of interests “is to prioritize the interests of the patient over any competing or professional interests via an evidence-based assessment of the benefits, harms, and costs of an intervention,” wrote the authors on behalf of the CGC.

The CGC created a tiered system to classify potential conflicts as low level, moderate level, or high level based on three tenets: transparency (all disclosures are freely accessible so readers can assess them for themselves), proportionality (not all conflicts of interest have equal risk), and consistency (policies should be impartially applied across all variables).

Examples of low-level conflicts of interest (COIs) include high-level COIs that have become inactive and intellectual interests tangentially related to the topic under discussion. Moderate-level COIs are usually intellectual interests clinically relevant to the guideline topic; these interests might prompt an individual to seek professional or financial advantages through association with guideline development.

High-level COIs are active relationships with high-risk entities, defined by the CGC as “an entity that has a direct financial stake in the clinical conclusions of a guideline or guidance statement.”

While the time frame for reporting health-related interests is 3 years, disclosure is an ongoing process when clinical guidelines are in development because interests change over time, the authors said. Prospective guidelines committee members complete disclosure of interest forms before working on CGC projects, and they update these forms before each in-person CGC meeting.

“The CGC’s policy does not mandate disclosure of interests related primarily to personal matters or relationships outside the household,” such as political, religious, or ideological views, they noted.

The CGC maintains a DOI-COI Review and Management Panel to reviews conflicts, and all ACP guidelines include a list of relevant conflicts for committee members.

The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A and TJ Wilt. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 .

This article was updated 8/22/19.

The American College of Physicians recently described its methods for developing clinical guidelines and guidance statements, in a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Any person involved in the development of an ACP clinical guideline or guidance statement must disclose all financial and intellectual interests related to health care from the previous 3 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, wrote.

“The goals of our process are to mitigate any actual bias during the development of ACP’s clinical recommendations and to ensure creditability and public trust in our clinical policies by reducing the potential for perceived bias,” noted Robert M. McLean, MD, president of the ACP, in a statement.

This paper’s publication comes on the heels of authors of a Cancer paper having reported that nearly 25% of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s guideline authors who were not exempt from reporting conflicts of interest failed to disclose receiving industry payments.

The ACP committee’s guiding principle for collection of disclosures of interest and management of conflicts of interests “is to prioritize the interests of the patient over any competing or professional interests via an evidence-based assessment of the benefits, harms, and costs of an intervention,” wrote the authors on behalf of the CGC.

The CGC created a tiered system to classify potential conflicts as low level, moderate level, or high level based on three tenets: transparency (all disclosures are freely accessible so readers can assess them for themselves), proportionality (not all conflicts of interest have equal risk), and consistency (policies should be impartially applied across all variables).

Examples of low-level conflicts of interest (COIs) include high-level COIs that have become inactive and intellectual interests tangentially related to the topic under discussion. Moderate-level COIs are usually intellectual interests clinically relevant to the guideline topic; these interests might prompt an individual to seek professional or financial advantages through association with guideline development.

High-level COIs are active relationships with high-risk entities, defined by the CGC as “an entity that has a direct financial stake in the clinical conclusions of a guideline or guidance statement.”

While the time frame for reporting health-related interests is 3 years, disclosure is an ongoing process when clinical guidelines are in development because interests change over time, the authors said. Prospective guidelines committee members complete disclosure of interest forms before working on CGC projects, and they update these forms before each in-person CGC meeting.

“The CGC’s policy does not mandate disclosure of interests related primarily to personal matters or relationships outside the household,” such as political, religious, or ideological views, they noted.

The CGC maintains a DOI-COI Review and Management Panel to reviews conflicts, and all ACP guidelines include a list of relevant conflicts for committee members.

The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A and TJ Wilt. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 .

This article was updated 8/22/19.

The American College of Physicians recently described its methods for developing clinical guidelines and guidance statements, in a paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Any person involved in the development of an ACP clinical guideline or guidance statement must disclose all financial and intellectual interests related to health care from the previous 3 years,” Amir Qaseem, MD, and Timothy J. Wilt, MD, wrote.

“The goals of our process are to mitigate any actual bias during the development of ACP’s clinical recommendations and to ensure creditability and public trust in our clinical policies by reducing the potential for perceived bias,” noted Robert M. McLean, MD, president of the ACP, in a statement.

This paper’s publication comes on the heels of authors of a Cancer paper having reported that nearly 25% of the American Society of Clinical Oncology’s guideline authors who were not exempt from reporting conflicts of interest failed to disclose receiving industry payments.

The ACP committee’s guiding principle for collection of disclosures of interest and management of conflicts of interests “is to prioritize the interests of the patient over any competing or professional interests via an evidence-based assessment of the benefits, harms, and costs of an intervention,” wrote the authors on behalf of the CGC.

The CGC created a tiered system to classify potential conflicts as low level, moderate level, or high level based on three tenets: transparency (all disclosures are freely accessible so readers can assess them for themselves), proportionality (not all conflicts of interest have equal risk), and consistency (policies should be impartially applied across all variables).

Examples of low-level conflicts of interest (COIs) include high-level COIs that have become inactive and intellectual interests tangentially related to the topic under discussion. Moderate-level COIs are usually intellectual interests clinically relevant to the guideline topic; these interests might prompt an individual to seek professional or financial advantages through association with guideline development.

High-level COIs are active relationships with high-risk entities, defined by the CGC as “an entity that has a direct financial stake in the clinical conclusions of a guideline or guidance statement.”

While the time frame for reporting health-related interests is 3 years, disclosure is an ongoing process when clinical guidelines are in development because interests change over time, the authors said. Prospective guidelines committee members complete disclosure of interest forms before working on CGC projects, and they update these forms before each in-person CGC meeting.

“The CGC’s policy does not mandate disclosure of interests related primarily to personal matters or relationships outside the household,” such as political, religious, or ideological views, they noted.

The CGC maintains a DOI-COI Review and Management Panel to reviews conflicts, and all ACP guidelines include a list of relevant conflicts for committee members.

The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Qaseem A and TJ Wilt. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Aug 20. doi: 10.7326/M18-3279 .

This article was updated 8/22/19.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Progression in Huntington’s linked to CAG repeat number

The progression, not just age of onset, of Huntington’s disease can be predicted by a measurable genetic factor, researchers have learned.

Huntington’s, an inherited neurodegenerative disease that affects motor function and cognition, is caused by an expansion of the CAG trinucleotide sequence on the huntingtin gene. Scientists have previously linked younger age at onset to a higher number of CAG repeats on the gene, but the association between these and the rate of progression after onset was poorly understood.

In research published online August 12 in JAMA Neurology, investigators linked the rate of progression – which, like age at onset, is highly variable in Huntington’s – to CAG repeat length. CAG repeat length was strongly associated with distinct patterns of brain damage, as well as clinical measures of cognitive and motor decline.

For their research, Douglas R. Langbehn, MD, PhD, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and colleagues used data from two longitudinal observational studies in gene carriers for Huntington’s and nonrelated controls. The researchers looked at data from 443 participants (56% female; mean age, 44.4 years) who were followed for a mean of 4 years, with more than 2,000 study visits across the multisite cohort. Neuropsychiatric testing and brain imaging were conducted annually, using composite scoring systems of the investigators’ design. These composite scores sought to be more sensitive by combining results from several validated clinical and imaging tests.

Age and speed of decline in total functional capacity tracked with more CAG repeats, the researchers found. For example, in people with 40 CAG repeats, the estimated mean age of initial motor-cognitive score change was 42.46 years; for those with 45 repeats, 26.65 years, and for people with 50 CAG repeats, 18.49 years. Higher repeats were seen significantly associated with accelerated, nonlinear decline on both clinical and brain-volume measures, except gray matter volume, according to principal component analyses conducted on the data.

“We derived a single summary measure capturing the motor-cognitive phenotype and showed that the accelerating progression of the phenotype with aging is highly CAG repeat length dependent (i.e., those with higher CAG decline earlier and faster). Contrary to some previous assertions, this CAG dependence continues well past the onset of clinical illness,” Dr. Langbehn and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “By characterizing these CAG repeat length–dependent disease trajectories, we provide insights into disease progression that may guide future therapeutic approaches and identify the most appropriate intervention ages to prevent clinical decline.”

Dr. Langbehn and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its likely exclusion of the sickest subjects because of the cohorts’ design. The CHDI Foundation funded the study. Of the 16 coauthors, 13 reported receiving funding from CHDI and/or from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

SOURCE: Langbehn et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2328

The progression, not just age of onset, of Huntington’s disease can be predicted by a measurable genetic factor, researchers have learned.

Huntington’s, an inherited neurodegenerative disease that affects motor function and cognition, is caused by an expansion of the CAG trinucleotide sequence on the huntingtin gene. Scientists have previously linked younger age at onset to a higher number of CAG repeats on the gene, but the association between these and the rate of progression after onset was poorly understood.

In research published online August 12 in JAMA Neurology, investigators linked the rate of progression – which, like age at onset, is highly variable in Huntington’s – to CAG repeat length. CAG repeat length was strongly associated with distinct patterns of brain damage, as well as clinical measures of cognitive and motor decline.

For their research, Douglas R. Langbehn, MD, PhD, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and colleagues used data from two longitudinal observational studies in gene carriers for Huntington’s and nonrelated controls. The researchers looked at data from 443 participants (56% female; mean age, 44.4 years) who were followed for a mean of 4 years, with more than 2,000 study visits across the multisite cohort. Neuropsychiatric testing and brain imaging were conducted annually, using composite scoring systems of the investigators’ design. These composite scores sought to be more sensitive by combining results from several validated clinical and imaging tests.

Age and speed of decline in total functional capacity tracked with more CAG repeats, the researchers found. For example, in people with 40 CAG repeats, the estimated mean age of initial motor-cognitive score change was 42.46 years; for those with 45 repeats, 26.65 years, and for people with 50 CAG repeats, 18.49 years. Higher repeats were seen significantly associated with accelerated, nonlinear decline on both clinical and brain-volume measures, except gray matter volume, according to principal component analyses conducted on the data.

“We derived a single summary measure capturing the motor-cognitive phenotype and showed that the accelerating progression of the phenotype with aging is highly CAG repeat length dependent (i.e., those with higher CAG decline earlier and faster). Contrary to some previous assertions, this CAG dependence continues well past the onset of clinical illness,” Dr. Langbehn and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “By characterizing these CAG repeat length–dependent disease trajectories, we provide insights into disease progression that may guide future therapeutic approaches and identify the most appropriate intervention ages to prevent clinical decline.”

Dr. Langbehn and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its likely exclusion of the sickest subjects because of the cohorts’ design. The CHDI Foundation funded the study. Of the 16 coauthors, 13 reported receiving funding from CHDI and/or from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

SOURCE: Langbehn et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2328

The progression, not just age of onset, of Huntington’s disease can be predicted by a measurable genetic factor, researchers have learned.

Huntington’s, an inherited neurodegenerative disease that affects motor function and cognition, is caused by an expansion of the CAG trinucleotide sequence on the huntingtin gene. Scientists have previously linked younger age at onset to a higher number of CAG repeats on the gene, but the association between these and the rate of progression after onset was poorly understood.

In research published online August 12 in JAMA Neurology, investigators linked the rate of progression – which, like age at onset, is highly variable in Huntington’s – to CAG repeat length. CAG repeat length was strongly associated with distinct patterns of brain damage, as well as clinical measures of cognitive and motor decline.

For their research, Douglas R. Langbehn, MD, PhD, of the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and colleagues used data from two longitudinal observational studies in gene carriers for Huntington’s and nonrelated controls. The researchers looked at data from 443 participants (56% female; mean age, 44.4 years) who were followed for a mean of 4 years, with more than 2,000 study visits across the multisite cohort. Neuropsychiatric testing and brain imaging were conducted annually, using composite scoring systems of the investigators’ design. These composite scores sought to be more sensitive by combining results from several validated clinical and imaging tests.

Age and speed of decline in total functional capacity tracked with more CAG repeats, the researchers found. For example, in people with 40 CAG repeats, the estimated mean age of initial motor-cognitive score change was 42.46 years; for those with 45 repeats, 26.65 years, and for people with 50 CAG repeats, 18.49 years. Higher repeats were seen significantly associated with accelerated, nonlinear decline on both clinical and brain-volume measures, except gray matter volume, according to principal component analyses conducted on the data.

“We derived a single summary measure capturing the motor-cognitive phenotype and showed that the accelerating progression of the phenotype with aging is highly CAG repeat length dependent (i.e., those with higher CAG decline earlier and faster). Contrary to some previous assertions, this CAG dependence continues well past the onset of clinical illness,” Dr. Langbehn and colleagues wrote in their analysis. “By characterizing these CAG repeat length–dependent disease trajectories, we provide insights into disease progression that may guide future therapeutic approaches and identify the most appropriate intervention ages to prevent clinical decline.”

Dr. Langbehn and colleagues acknowledged as a limitation of their study its likely exclusion of the sickest subjects because of the cohorts’ design. The CHDI Foundation funded the study. Of the 16 coauthors, 13 reported receiving funding from CHDI and/or from pharmaceutical manufacturers.

SOURCE: Langbehn et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2328

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: CAG closely tracked the rate of cognitive and motor decline among patients with HD.

Study details: Brain imaging and neuropsychiatric testing data from 443 patients enrolled in cohort studies in people with HD-causing mutations

Disclosures: CHDI sponsored the study, and most coauthors disclosed financial relationships with the sponsor and/or pharmaceutical firms.

Source: Langbehn et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2328.

Clicking override when the EHR system argues about an order

The EHR system at the hospital occasionally argues with me about my orders.

I may order a brain MRI, or CT angiography, or pretty much anything, and when I click to submit it a box pops up, telling me I shouldn’t be ordering that.

Sometimes it’s based on cost, saying that the MRI is more expensive than a CT, and according to some internal algorithm I should do that instead. Other times it says the test isn’t appropriate given the patient’s condition, age, zodiac sign, whatever. It might also say the test is redundant, because the patient just had a brain MRI during an admission last month.

I ignore them. There’s an override button to close the box and order the test, and that’s what I always click.

I have no objection to a reasonable review, but neither the computer nor its algorithms went through medical school, or residency, or read journals regularly, or have 20 years of experience in this field. I’d like to think (or hope) I know what I’m doing.

I don’t take this job lightly. When I order a test it’s because I’m trying to do the right thing for the patient. To find out what’s going on. To see what I can do to treat them. In short, to help as much as I can within the limitations of modern medical practice. Sometimes those things don’t always involve saving the insurance company money, or trying to get by with a previous study’s results.

Medicine is not a cookbook. While guidelines can be useful, every patient is different, and treatment plans have to be adjusted accordingly. It would be nice if this was the one-size-fits-all world the computer algorithms would like, but patient care is anything but.

I’d also rather “overcare” than “undercare.” To me, that’s just good practice. If I follow the computer’s advice and provide less care than needed and miss something, I’m pretty sure “because the computer told me not to” isn’t going to stand up as a defense in court.

I’m going to just keep on practicing medicine using, as one of my past attendings would say, “clinical correlation” and keeping what’s best for the patient in mind. Anything less may be fine for the computer, but not for me, and certainly not for those I’m trying to help.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The EHR system at the hospital occasionally argues with me about my orders.

I may order a brain MRI, or CT angiography, or pretty much anything, and when I click to submit it a box pops up, telling me I shouldn’t be ordering that.

Sometimes it’s based on cost, saying that the MRI is more expensive than a CT, and according to some internal algorithm I should do that instead. Other times it says the test isn’t appropriate given the patient’s condition, age, zodiac sign, whatever. It might also say the test is redundant, because the patient just had a brain MRI during an admission last month.

I ignore them. There’s an override button to close the box and order the test, and that’s what I always click.

I have no objection to a reasonable review, but neither the computer nor its algorithms went through medical school, or residency, or read journals regularly, or have 20 years of experience in this field. I’d like to think (or hope) I know what I’m doing.

I don’t take this job lightly. When I order a test it’s because I’m trying to do the right thing for the patient. To find out what’s going on. To see what I can do to treat them. In short, to help as much as I can within the limitations of modern medical practice. Sometimes those things don’t always involve saving the insurance company money, or trying to get by with a previous study’s results.

Medicine is not a cookbook. While guidelines can be useful, every patient is different, and treatment plans have to be adjusted accordingly. It would be nice if this was the one-size-fits-all world the computer algorithms would like, but patient care is anything but.

I’d also rather “overcare” than “undercare.” To me, that’s just good practice. If I follow the computer’s advice and provide less care than needed and miss something, I’m pretty sure “because the computer told me not to” isn’t going to stand up as a defense in court.

I’m going to just keep on practicing medicine using, as one of my past attendings would say, “clinical correlation” and keeping what’s best for the patient in mind. Anything less may be fine for the computer, but not for me, and certainly not for those I’m trying to help.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The EHR system at the hospital occasionally argues with me about my orders.

I may order a brain MRI, or CT angiography, or pretty much anything, and when I click to submit it a box pops up, telling me I shouldn’t be ordering that.

Sometimes it’s based on cost, saying that the MRI is more expensive than a CT, and according to some internal algorithm I should do that instead. Other times it says the test isn’t appropriate given the patient’s condition, age, zodiac sign, whatever. It might also say the test is redundant, because the patient just had a brain MRI during an admission last month.

I ignore them. There’s an override button to close the box and order the test, and that’s what I always click.

I have no objection to a reasonable review, but neither the computer nor its algorithms went through medical school, or residency, or read journals regularly, or have 20 years of experience in this field. I’d like to think (or hope) I know what I’m doing.

I don’t take this job lightly. When I order a test it’s because I’m trying to do the right thing for the patient. To find out what’s going on. To see what I can do to treat them. In short, to help as much as I can within the limitations of modern medical practice. Sometimes those things don’t always involve saving the insurance company money, or trying to get by with a previous study’s results.

Medicine is not a cookbook. While guidelines can be useful, every patient is different, and treatment plans have to be adjusted accordingly. It would be nice if this was the one-size-fits-all world the computer algorithms would like, but patient care is anything but.

I’d also rather “overcare” than “undercare.” To me, that’s just good practice. If I follow the computer’s advice and provide less care than needed and miss something, I’m pretty sure “because the computer told me not to” isn’t going to stand up as a defense in court.

I’m going to just keep on practicing medicine using, as one of my past attendings would say, “clinical correlation” and keeping what’s best for the patient in mind. Anything less may be fine for the computer, but not for me, and certainly not for those I’m trying to help.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Pediatric, adolescent migraine treatment and prevention guidelines are updated

Two new guidelines on the treatment and prevention of migraines in children and adolescents have been released by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.

This update to the previous guidelines released by the American Academy of Neurology in 2004 reflects the expansion in pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches during the last 15 years, Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, director of the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

“There has also been an increase in the number of randomized controlled studies, which have allowed for a more robust statement on acute and preventive treatments to be made,” said Dr. Hershey, who is also a senior author for both guidelines.

The two reports focused on separate issues: One guideline outlined the options for treatment of acute migraine, and the second guideline summarized the available studies on the effectiveness of preventive medications for migraine in children and adolescents.

The guidelines recommend a physical examination and history to establish a specific headache diagnosis and afford a treatment that provides fast and complete pain relief. Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient realizes an attack is occurring. Patients with signs of secondary headache should be evaluated by a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Studies support the use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for pain relief in cases of acute migraine, but only some triptans (such as almotriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan/naproxen, and zolmitriptan nasal spray) are approved for use in adolescents. Specifically, sumatriptan/naproxen was shown to be effective when compared with placebo in studies with adolescents, whose headache symptoms resolved within 2 hours.

It may be necessary to try more than one triptan, the guidelines noted, because patients respond differently to medications. A failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily mean that treatment with another triptan will be unsuccessful.

The guidelines also focused on patient and family education to improve medication safety and adherence. Lifestyle modification, avoidance of migraine triggers, creating good sleep habits, and staying hydrated can help reduce migraines. While no medications improved associated symptoms of migraines such as nausea or vomiting, triptans did show a benefit in reducing phonophobia and photophobia.

Evidence for pharmacologic prevention of migraines in children and adolescents is limited, according to the guidelines. In the 15 studies included in a literature review, there was not sufficient evidence to show preventive treatments, such as divalproex, onabotulinumtoxinA, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and flunarizine, were more effective than placebo at reducing the frequency of headaches. There was some evidence to show propranolol in children and topiramate and cinnarizine in children and adolescents can reduce headache frequency. Children and adolescents who received cognitive-behavioral therapy together with amitriptyline were more likely to have reduced frequency of headaches than were those who received amitriptyline with patient education.

“The consensus conclusion was that a multidisciplinary approach that combines acute treatments, preventive treatments, and healthy habits is likely to have the best outcomes,” said Dr. Hershey.

Dr. Hershey acknowledged the many gaps between what is clinically observed and what the studies in the guidelines demonstrated.

“One of the biggest questions is how to minimize the expectation response in the controlled studies,” he said. “Additionally, we are moving toward a better recognition of the mechanism by which the various treatments work in a genetic-based disease that is polygenic in nature” with up to 38 different gene polymorphisms identified to date.

The guidelines also do not address newer treatments, such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) antibodies, CGRP antagonists, serotonin antagonists, and devices because there are as yet no studies of their effectiveness in children and adolescents.

“They have been studied in adults, so will be prone to the expectation response; but given the large number of diverse therapies, one can hope that many of the gaps can be filled,” said Dr. Hershey.

The American Academy of Neurology provided funding for development of the guidelines and reimbursed authors who served as subcommittee members for travel expenses and in-person meetings. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, grants, honorariums, consultancies, and publishing royalties for pharmaceutical companies and other organizations.

SOURCES: Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105.

Two new guidelines on the treatment and prevention of migraines in children and adolescents have been released by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.

This update to the previous guidelines released by the American Academy of Neurology in 2004 reflects the expansion in pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches during the last 15 years, Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, director of the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

“There has also been an increase in the number of randomized controlled studies, which have allowed for a more robust statement on acute and preventive treatments to be made,” said Dr. Hershey, who is also a senior author for both guidelines.

The two reports focused on separate issues: One guideline outlined the options for treatment of acute migraine, and the second guideline summarized the available studies on the effectiveness of preventive medications for migraine in children and adolescents.

The guidelines recommend a physical examination and history to establish a specific headache diagnosis and afford a treatment that provides fast and complete pain relief. Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient realizes an attack is occurring. Patients with signs of secondary headache should be evaluated by a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Studies support the use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for pain relief in cases of acute migraine, but only some triptans (such as almotriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan/naproxen, and zolmitriptan nasal spray) are approved for use in adolescents. Specifically, sumatriptan/naproxen was shown to be effective when compared with placebo in studies with adolescents, whose headache symptoms resolved within 2 hours.

It may be necessary to try more than one triptan, the guidelines noted, because patients respond differently to medications. A failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily mean that treatment with another triptan will be unsuccessful.

The guidelines also focused on patient and family education to improve medication safety and adherence. Lifestyle modification, avoidance of migraine triggers, creating good sleep habits, and staying hydrated can help reduce migraines. While no medications improved associated symptoms of migraines such as nausea or vomiting, triptans did show a benefit in reducing phonophobia and photophobia.

Evidence for pharmacologic prevention of migraines in children and adolescents is limited, according to the guidelines. In the 15 studies included in a literature review, there was not sufficient evidence to show preventive treatments, such as divalproex, onabotulinumtoxinA, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and flunarizine, were more effective than placebo at reducing the frequency of headaches. There was some evidence to show propranolol in children and topiramate and cinnarizine in children and adolescents can reduce headache frequency. Children and adolescents who received cognitive-behavioral therapy together with amitriptyline were more likely to have reduced frequency of headaches than were those who received amitriptyline with patient education.

“The consensus conclusion was that a multidisciplinary approach that combines acute treatments, preventive treatments, and healthy habits is likely to have the best outcomes,” said Dr. Hershey.

Dr. Hershey acknowledged the many gaps between what is clinically observed and what the studies in the guidelines demonstrated.

“One of the biggest questions is how to minimize the expectation response in the controlled studies,” he said. “Additionally, we are moving toward a better recognition of the mechanism by which the various treatments work in a genetic-based disease that is polygenic in nature” with up to 38 different gene polymorphisms identified to date.

The guidelines also do not address newer treatments, such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) antibodies, CGRP antagonists, serotonin antagonists, and devices because there are as yet no studies of their effectiveness in children and adolescents.

“They have been studied in adults, so will be prone to the expectation response; but given the large number of diverse therapies, one can hope that many of the gaps can be filled,” said Dr. Hershey.

The American Academy of Neurology provided funding for development of the guidelines and reimbursed authors who served as subcommittee members for travel expenses and in-person meetings. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, grants, honorariums, consultancies, and publishing royalties for pharmaceutical companies and other organizations.

SOURCES: Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105.

Two new guidelines on the treatment and prevention of migraines in children and adolescents have been released by the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.

This update to the previous guidelines released by the American Academy of Neurology in 2004 reflects the expansion in pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches during the last 15 years, Andrew D. Hershey, MD, PhD, director of the division of neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology, said in an interview.

“There has also been an increase in the number of randomized controlled studies, which have allowed for a more robust statement on acute and preventive treatments to be made,” said Dr. Hershey, who is also a senior author for both guidelines.

The two reports focused on separate issues: One guideline outlined the options for treatment of acute migraine, and the second guideline summarized the available studies on the effectiveness of preventive medications for migraine in children and adolescents.

The guidelines recommend a physical examination and history to establish a specific headache diagnosis and afford a treatment that provides fast and complete pain relief. Treatment should be initiated as soon as a patient realizes an attack is occurring. Patients with signs of secondary headache should be evaluated by a neurologist or a headache specialist.

Studies support the use of ibuprofen and acetaminophen for pain relief in cases of acute migraine, but only some triptans (such as almotriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan/naproxen, and zolmitriptan nasal spray) are approved for use in adolescents. Specifically, sumatriptan/naproxen was shown to be effective when compared with placebo in studies with adolescents, whose headache symptoms resolved within 2 hours.

It may be necessary to try more than one triptan, the guidelines noted, because patients respond differently to medications. A failure to respond to one triptan does not necessarily mean that treatment with another triptan will be unsuccessful.

The guidelines also focused on patient and family education to improve medication safety and adherence. Lifestyle modification, avoidance of migraine triggers, creating good sleep habits, and staying hydrated can help reduce migraines. While no medications improved associated symptoms of migraines such as nausea or vomiting, triptans did show a benefit in reducing phonophobia and photophobia.

Evidence for pharmacologic prevention of migraines in children and adolescents is limited, according to the guidelines. In the 15 studies included in a literature review, there was not sufficient evidence to show preventive treatments, such as divalproex, onabotulinumtoxinA, amitriptyline, nimodipine, and flunarizine, were more effective than placebo at reducing the frequency of headaches. There was some evidence to show propranolol in children and topiramate and cinnarizine in children and adolescents can reduce headache frequency. Children and adolescents who received cognitive-behavioral therapy together with amitriptyline were more likely to have reduced frequency of headaches than were those who received amitriptyline with patient education.

“The consensus conclusion was that a multidisciplinary approach that combines acute treatments, preventive treatments, and healthy habits is likely to have the best outcomes,” said Dr. Hershey.

Dr. Hershey acknowledged the many gaps between what is clinically observed and what the studies in the guidelines demonstrated.

“One of the biggest questions is how to minimize the expectation response in the controlled studies,” he said. “Additionally, we are moving toward a better recognition of the mechanism by which the various treatments work in a genetic-based disease that is polygenic in nature” with up to 38 different gene polymorphisms identified to date.

The guidelines also do not address newer treatments, such as calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP) antibodies, CGRP antagonists, serotonin antagonists, and devices because there are as yet no studies of their effectiveness in children and adolescents.

“They have been studied in adults, so will be prone to the expectation response; but given the large number of diverse therapies, one can hope that many of the gaps can be filled,” said Dr. Hershey.

The American Academy of Neurology provided funding for development of the guidelines and reimbursed authors who served as subcommittee members for travel expenses and in-person meetings. The authors reported personal and institutional relationships in the form of advisory board memberships, investigator appointments, speakers bureau positions, research support, grants, honorariums, consultancies, and publishing royalties for pharmaceutical companies and other organizations.

SOURCES: Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008095. Oskoui M et al. Neurology. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008105.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Ubrogepant shows acute migraine efficacy in triptan nonresponders

PHILADELPHIA – The oral, small molecule, calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist ubrogepant, currently under regulatory review for approval as a treatment for acute migraine headache, was as effective for migraine relief in patients with a history of triptan ineffectiveness as it was in patients for whom triptans had been effective, based on a post hoc analysis of data collected from 1,798 patients enrolled in two phase 3 trials.

In the roughly one-quarter of all patients who had a clinical history consistent with triptan ineffectiveness, one 50-mg dose of ubrogepant led to pain freedom 2 hours after treatment in 16% of patients, compared with a response rate of 8% in placebo-treated patients. Ubrogepant’s effectiveness rate that was about the same as seen in patients with a history of triptan effectiveness, who were about 37% of the study population, Susan Hutchinson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Among those with a history of triptan effectiveness, 20% were pain free after 2 hours, compared with 11% of placebo-treated controls, said Dr. Hutchinson, a family physician and headache specialist who practices in Irvine, Calif. Both of these between-group differences were statistically significant. The remaining patients included in the analysis had no triptan history, and among these patients a single, 50-mg dose of ubrogepant produced pain freedom at 2 hours in 24% of patients, versus an 18% response in placebo-treated controls, a difference that fell short of statistical significance.

The analysis Dr. Hutchinson reported came from data collected in two pivotal trials of ubrogepant for treatment of an acute migraine headache, the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials, which together randomized more than 2,600 migraine patients eligible for the study’s modified intention-to-treat analysis, and 1,798 patients from that analysis who received a 50-mg dose of ubrogepant or placebo. In March 2019, the company developing ubrogepant, Allergan, announced that the Food and Drug Administration had accepted the company’s application for marketing approval of ubrogepant as a treatment for acute migraine largely based on data from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

The researchers defined a history of triptan ineffectiveness as a patient who never used a triptan because of a warning, precaution, or contraindication, a patient who recently used triptans but did not achieve pain freedom within 2 hours more than half the time taking the drugs, or a patient who no longer used triptans because of adverse effects or lack of efficacy. Patients who had used triptans in the past and had complete pain relief within 2 hours more than half the time were deemed triptan-effective patients.

The analysis also looked at two other endpoints in addition to complete pain freedom: complete relief of the most-bothersome symptom of the migraine headache (photophobia for most patients), which resolved in 39% and 36% of the triptan-effective and triptan-ineffective patients, respectively, compared with placebo response rates of 27% and 23%; both between-group differences were statistically significant. A third measure of efficacy was some degree of pain relief after 2 hours, which occurred in 62% of patients in whom triptans were effective and 55% in those in whom triptans were ineffective, which were again statistically significant higher rates than among patients who received placebo.

Safety findings from the two ubrogepant pivotal trials showed good drug tolerability, with no treatment-related serious adverse events, and a profile of modest numbers of treatment-related and total adverse events similar to what occurred among patients who received placebo.

ACHIEVE I and II were funded by Allergan, the company developing ubrogepant. Dr. Hutchinson has been an adviser to and a speaker on behalf of Allergan and several other companies.

SOURCE: Blumenfeld AM. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract IOR02.

PHILADELPHIA – The oral, small molecule, calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist ubrogepant, currently under regulatory review for approval as a treatment for acute migraine headache, was as effective for migraine relief in patients with a history of triptan ineffectiveness as it was in patients for whom triptans had been effective, based on a post hoc analysis of data collected from 1,798 patients enrolled in two phase 3 trials.

In the roughly one-quarter of all patients who had a clinical history consistent with triptan ineffectiveness, one 50-mg dose of ubrogepant led to pain freedom 2 hours after treatment in 16% of patients, compared with a response rate of 8% in placebo-treated patients. Ubrogepant’s effectiveness rate that was about the same as seen in patients with a history of triptan effectiveness, who were about 37% of the study population, Susan Hutchinson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Among those with a history of triptan effectiveness, 20% were pain free after 2 hours, compared with 11% of placebo-treated controls, said Dr. Hutchinson, a family physician and headache specialist who practices in Irvine, Calif. Both of these between-group differences were statistically significant. The remaining patients included in the analysis had no triptan history, and among these patients a single, 50-mg dose of ubrogepant produced pain freedom at 2 hours in 24% of patients, versus an 18% response in placebo-treated controls, a difference that fell short of statistical significance.

The analysis Dr. Hutchinson reported came from data collected in two pivotal trials of ubrogepant for treatment of an acute migraine headache, the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials, which together randomized more than 2,600 migraine patients eligible for the study’s modified intention-to-treat analysis, and 1,798 patients from that analysis who received a 50-mg dose of ubrogepant or placebo. In March 2019, the company developing ubrogepant, Allergan, announced that the Food and Drug Administration had accepted the company’s application for marketing approval of ubrogepant as a treatment for acute migraine largely based on data from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

The researchers defined a history of triptan ineffectiveness as a patient who never used a triptan because of a warning, precaution, or contraindication, a patient who recently used triptans but did not achieve pain freedom within 2 hours more than half the time taking the drugs, or a patient who no longer used triptans because of adverse effects or lack of efficacy. Patients who had used triptans in the past and had complete pain relief within 2 hours more than half the time were deemed triptan-effective patients.

The analysis also looked at two other endpoints in addition to complete pain freedom: complete relief of the most-bothersome symptom of the migraine headache (photophobia for most patients), which resolved in 39% and 36% of the triptan-effective and triptan-ineffective patients, respectively, compared with placebo response rates of 27% and 23%; both between-group differences were statistically significant. A third measure of efficacy was some degree of pain relief after 2 hours, which occurred in 62% of patients in whom triptans were effective and 55% in those in whom triptans were ineffective, which were again statistically significant higher rates than among patients who received placebo.

Safety findings from the two ubrogepant pivotal trials showed good drug tolerability, with no treatment-related serious adverse events, and a profile of modest numbers of treatment-related and total adverse events similar to what occurred among patients who received placebo.

ACHIEVE I and II were funded by Allergan, the company developing ubrogepant. Dr. Hutchinson has been an adviser to and a speaker on behalf of Allergan and several other companies.

SOURCE: Blumenfeld AM. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract IOR02.

PHILADELPHIA – The oral, small molecule, calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist ubrogepant, currently under regulatory review for approval as a treatment for acute migraine headache, was as effective for migraine relief in patients with a history of triptan ineffectiveness as it was in patients for whom triptans had been effective, based on a post hoc analysis of data collected from 1,798 patients enrolled in two phase 3 trials.

In the roughly one-quarter of all patients who had a clinical history consistent with triptan ineffectiveness, one 50-mg dose of ubrogepant led to pain freedom 2 hours after treatment in 16% of patients, compared with a response rate of 8% in placebo-treated patients. Ubrogepant’s effectiveness rate that was about the same as seen in patients with a history of triptan effectiveness, who were about 37% of the study population, Susan Hutchinson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

Among those with a history of triptan effectiveness, 20% were pain free after 2 hours, compared with 11% of placebo-treated controls, said Dr. Hutchinson, a family physician and headache specialist who practices in Irvine, Calif. Both of these between-group differences were statistically significant. The remaining patients included in the analysis had no triptan history, and among these patients a single, 50-mg dose of ubrogepant produced pain freedom at 2 hours in 24% of patients, versus an 18% response in placebo-treated controls, a difference that fell short of statistical significance.

The analysis Dr. Hutchinson reported came from data collected in two pivotal trials of ubrogepant for treatment of an acute migraine headache, the ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II trials, which together randomized more than 2,600 migraine patients eligible for the study’s modified intention-to-treat analysis, and 1,798 patients from that analysis who received a 50-mg dose of ubrogepant or placebo. In March 2019, the company developing ubrogepant, Allergan, announced that the Food and Drug Administration had accepted the company’s application for marketing approval of ubrogepant as a treatment for acute migraine largely based on data from ACHIEVE I and ACHIEVE II.

The researchers defined a history of triptan ineffectiveness as a patient who never used a triptan because of a warning, precaution, or contraindication, a patient who recently used triptans but did not achieve pain freedom within 2 hours more than half the time taking the drugs, or a patient who no longer used triptans because of adverse effects or lack of efficacy. Patients who had used triptans in the past and had complete pain relief within 2 hours more than half the time were deemed triptan-effective patients.

The analysis also looked at two other endpoints in addition to complete pain freedom: complete relief of the most-bothersome symptom of the migraine headache (photophobia for most patients), which resolved in 39% and 36% of the triptan-effective and triptan-ineffective patients, respectively, compared with placebo response rates of 27% and 23%; both between-group differences were statistically significant. A third measure of efficacy was some degree of pain relief after 2 hours, which occurred in 62% of patients in whom triptans were effective and 55% in those in whom triptans were ineffective, which were again statistically significant higher rates than among patients who received placebo.

Safety findings from the two ubrogepant pivotal trials showed good drug tolerability, with no treatment-related serious adverse events, and a profile of modest numbers of treatment-related and total adverse events similar to what occurred among patients who received placebo.

ACHIEVE I and II were funded by Allergan, the company developing ubrogepant. Dr. Hutchinson has been an adviser to and a speaker on behalf of Allergan and several other companies.

SOURCE: Blumenfeld AM. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract IOR02.

REPORTING FROM AHS 2019

Legal duty to nonpatients: Driving accidents

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.

The case is currently on appeal. The AMA has filed an amicus brief in support of Dr. Lerner,1 pointing out that third-party claims had previously been rejected in New Jersey, where the injured victim is not readily identifiable. The brief emphasizes the folly of placing the physician or therapist in the untenable position of serving two potentially competing interests when a physician’s priority should be providing care to the patient. It referenced a similar case in Kansas, where a motorist who had fallen asleep at the wheel struck a bicyclist. The motorist was being treated by a neurologist for a sleep disorder.2 The Kansas Supreme Court held that there was no special relationship between the doctor and the cyclist that would impose a duty to warn the motorist about harming a third party.

Other jurisdictions have likewise rejected attempts at “derivative duties” in automobile accident cases. The Connecticut Supreme Court has ruled3 that doctors are immune from third party traffic accident lawsuits, as such litigation would detract from what’s best for the patient (“a physician’s desire to avoid lawsuits may result in far more restrictive advice than necessary for the patient’s well-being”). In that case, the defendant-gastroenterologist, Dr. Troncale, was treating a patient with hepatic encephalopathy and had not warned of the associated risk of driving. And an Illinois court dismissed a third party’s case against a hospital when one of its physicians fell asleep at the wheel after working excessive hours.4

In contrast, other jurisdictions have found a legal duty for physicians toward nonpatient victims. For example, in McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group,5 a car suddenly veered across five lanes of traffic, striking an 11-year-old girl and crushing her against a cement planter. The driver alleged that the prescription medication, Prazosin, caused him to lose control of the car, and that the treating physician was negligent, first in prescribing an inappropriate type and dose of medication, and second in failing to warn of potential side effects that could affect driving ability. The Hawaii Supreme Court emphasized that the risk of tort liability to an individual physician already discourages negligent prescribing; therefore, a physician does not have a duty to third parties where the alleged negligence involves prescribing decisions, i.e., whether to prescribe medication at all, which medication to prescribe, and what dosage to use. On the other hand, physicians have a duty to their patients to warn of potential adverse effects and this responsibility should therefore extend to third parties. Thus, liability would attach to injuries of innocent third parties as a result of failing to warn of a medication’s effects on driving—unless a reasonable person could be expected to be aware of this risk without the warning.

A foreseeable and unreasonable risk of harm is an important but not the only decisive factor in construing the existence of legal duty. Under some circumstances, the term “special relationship” has been employed based on a consideration of existing social values, customs, and policy considerations. In a Massachusetts case,6 a family physician had failed to warn his patient of the risk of diabetes drugs when operating a vehicle. Some 45 minutes after the patient’s discharge from the hospital, he developed hypoglycemia, losing consciousness and injuring a motorcyclist who then sued the doctor. The court invoked the “special relationship” rationale in ruling that the doctor owed a duty to the motorcyclist for public policy reasons.

Dr. Tan is professor of medicine and former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at siang@hawaii.edu.

References

1. Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera, In the Superior Court of New Jersey Appellate Division, Docket No. A-001255-18T3.

2. Calwell v. Hassan, 925 P.2d 422, 430 (Kan. 1996).

3. Jarmie v. Troncale, 50 A.3d 802 (Conn. 2012).

4. Brewster v. Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Med. Ctr., 836 N.E.2d 635 (Ill. Ct. App. 2005).

5. McKenzie v. Hawaii Permanente Medical Group, 47 P.3d 1209 (Haw. 2002).

6. Arsenault v. McConarty, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 500 (2006).

Question: Driver D strikes a pedestrian after losing control of his vehicle from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. Both Driver D and pedestrian were seriously injured. Driver D was recently diagnosed with diabetes, and his physician had started him on insulin, but did not warn of driving risks associated with hypoglycemia. The injured pedestrian is a total stranger to both Driver D and his doctor. Given these facts, which one of the following choices is correct?

A. Driver D can sue his doctor for failure to disclose hypoglycemic risk of insulin therapy under the doctrine of informed consent.

B. The pedestrian can sue Driver D for negligent driving.

C. The pedestrian may succeed in suing Driver D’s doctor for failure to warn of hypoglycemia.

D. The pedestrian’s lawsuit against Driver D’s doctor may fail in a jurisdiction that does not recognize a doctor’s legal duty to an unidentifiable, nonpatient third party.

E. All statements above are correct.

Answer: E. This legal duty grows out of the doctor-patient relationship, and is normally owed to the patient and to no one else. However, in limited circumstances, it may be extended to other individuals, so-called third parties, who may be total strangers. Injured nonpatient third parties from driving accidents have successfully sued doctors for failing to warn their patients that their medical conditions and/or medications can adversely affect driving ability.

Vizzoni v. Mulford-Dera is a New Jersey malpractice case that is currently before the state’s appellate court. The issue is whether Dr. Lerner, a psychiatrist, can be found negligent for the death of a bicyclist caused by the psychiatrist’s patient, Ms. Mulford-Dera, whose car struck and killed the cyclist. The decedent’s estate alleged that the physician should have warned the patient of the risks of driving while taking psychotropic medications. Dr. Lerner had been treating Ms. Mulford-Dera for psychological conditions, including major depression, panic disorder, and attention deficit disorder. As part of her treatment, Dr. Lerner prescribed several medications, allegedly without disclosing their potential adverse impact on driving. The trial court granted summary judgment and dismissed the case, ruling that the doctor owed no direct or indirect duty to the victim.