User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Two genetic variants modify risk of Alzheimer’s disease

according to research published online August 14 in Science Translational Medicine. The variants affect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of a soluble form of the TREM2 protein (sTREM2), which may be involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. “Increasing TREM2 or activating the TREM2 signaling pathway could offer a new therapeutic approach for treating Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote the researchers.

Yuetiva Deming, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and colleagues conducted a genome-wide association study to identify genetic modifiers of CSF sTREM2. They analyzed CSF sTREM2 levels in 813 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Of this population, 172 participants had Alzheimer’s disease, 169 were cognitively normal, 183 had early mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 221 had late MCI, and 68 had significant memory concerns.

The rs1582763 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on chromosome 11 within the MS4A gene region was significantly associated with increased CSF levels of sTREM2. Conditional analyses of the MS4A locus indicated that rs6591561, a missense variant within MS4A4A, was associated with reduced CSF sTREM2. Analyzing 580 additional CSF sTREM2 samples, along with associated genetic data, from six other studies replicated these findings in an independent dataset.

Furthermore, Dr. Deming and colleagues found that rs1582763 was associated with reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease and older age at Alzheimer’s disease onset. In addition, rs6591561 was associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Subsequent analyses showed that rs1582763 modified the expression of the MS4A4A and MS4A6A genes in various tissues. This finding suggests that one or both of these genes are important for influencing the production of sTREM2, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues. Using human macrophages as a proxy for microglia, the investigators observed that the MS4A4A and TREM2 proteins colocalized on lipid rafts at the plasma membrane. In addition, sTREM2 concentrations increased with MS4A4A overexpression, and silencing of MS4A4A reduced sTREM2 production.

These findings “provide a putative biological connection between the MS4A family, TREM2, and Alzheimer’s disease risk,” wrote the researchers. The data also suggest that MS4A4A is a potential therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the role of sTREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease will require additional research, but it may be involved in pathogenesis, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues.

One of the study’s limitations is that the investigators included only common variants and thus could not determine the effect of genes that only harbor low-frequency or rare functional variants. Another limitation is that the data cannot support conclusions about whether other genes in the MS4A locus also modulate sTREM2, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues.

Grants from the National Institutes of Health supported this study. The investigators disclosed consulting and other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Deming Y et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau2291.

according to research published online August 14 in Science Translational Medicine. The variants affect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of a soluble form of the TREM2 protein (sTREM2), which may be involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. “Increasing TREM2 or activating the TREM2 signaling pathway could offer a new therapeutic approach for treating Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote the researchers.

Yuetiva Deming, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and colleagues conducted a genome-wide association study to identify genetic modifiers of CSF sTREM2. They analyzed CSF sTREM2 levels in 813 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Of this population, 172 participants had Alzheimer’s disease, 169 were cognitively normal, 183 had early mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 221 had late MCI, and 68 had significant memory concerns.

The rs1582763 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on chromosome 11 within the MS4A gene region was significantly associated with increased CSF levels of sTREM2. Conditional analyses of the MS4A locus indicated that rs6591561, a missense variant within MS4A4A, was associated with reduced CSF sTREM2. Analyzing 580 additional CSF sTREM2 samples, along with associated genetic data, from six other studies replicated these findings in an independent dataset.

Furthermore, Dr. Deming and colleagues found that rs1582763 was associated with reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease and older age at Alzheimer’s disease onset. In addition, rs6591561 was associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Subsequent analyses showed that rs1582763 modified the expression of the MS4A4A and MS4A6A genes in various tissues. This finding suggests that one or both of these genes are important for influencing the production of sTREM2, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues. Using human macrophages as a proxy for microglia, the investigators observed that the MS4A4A and TREM2 proteins colocalized on lipid rafts at the plasma membrane. In addition, sTREM2 concentrations increased with MS4A4A overexpression, and silencing of MS4A4A reduced sTREM2 production.

These findings “provide a putative biological connection between the MS4A family, TREM2, and Alzheimer’s disease risk,” wrote the researchers. The data also suggest that MS4A4A is a potential therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the role of sTREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease will require additional research, but it may be involved in pathogenesis, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues.

One of the study’s limitations is that the investigators included only common variants and thus could not determine the effect of genes that only harbor low-frequency or rare functional variants. Another limitation is that the data cannot support conclusions about whether other genes in the MS4A locus also modulate sTREM2, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues.

Grants from the National Institutes of Health supported this study. The investigators disclosed consulting and other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Deming Y et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau2291.

according to research published online August 14 in Science Translational Medicine. The variants affect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of a soluble form of the TREM2 protein (sTREM2), which may be involved in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. “Increasing TREM2 or activating the TREM2 signaling pathway could offer a new therapeutic approach for treating Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote the researchers.

Yuetiva Deming, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and colleagues conducted a genome-wide association study to identify genetic modifiers of CSF sTREM2. They analyzed CSF sTREM2 levels in 813 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Of this population, 172 participants had Alzheimer’s disease, 169 were cognitively normal, 183 had early mild cognitive impairment (MCI), 221 had late MCI, and 68 had significant memory concerns.

The rs1582763 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on chromosome 11 within the MS4A gene region was significantly associated with increased CSF levels of sTREM2. Conditional analyses of the MS4A locus indicated that rs6591561, a missense variant within MS4A4A, was associated with reduced CSF sTREM2. Analyzing 580 additional CSF sTREM2 samples, along with associated genetic data, from six other studies replicated these findings in an independent dataset.

Furthermore, Dr. Deming and colleagues found that rs1582763 was associated with reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease and older age at Alzheimer’s disease onset. In addition, rs6591561 was associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Subsequent analyses showed that rs1582763 modified the expression of the MS4A4A and MS4A6A genes in various tissues. This finding suggests that one or both of these genes are important for influencing the production of sTREM2, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues. Using human macrophages as a proxy for microglia, the investigators observed that the MS4A4A and TREM2 proteins colocalized on lipid rafts at the plasma membrane. In addition, sTREM2 concentrations increased with MS4A4A overexpression, and silencing of MS4A4A reduced sTREM2 production.

These findings “provide a putative biological connection between the MS4A family, TREM2, and Alzheimer’s disease risk,” wrote the researchers. The data also suggest that MS4A4A is a potential therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. Understanding the role of sTREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease will require additional research, but it may be involved in pathogenesis, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues.

One of the study’s limitations is that the investigators included only common variants and thus could not determine the effect of genes that only harbor low-frequency or rare functional variants. Another limitation is that the data cannot support conclusions about whether other genes in the MS4A locus also modulate sTREM2, wrote Dr. Deming and colleagues.

Grants from the National Institutes of Health supported this study. The investigators disclosed consulting and other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Deming Y et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau2291.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Two variants of MS4A are associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Major finding: The rs1582763 SNP is associated with reduced risk for Alzheimer’s disease, and rs6591561 is associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Study details: A genome-wide association study of 813 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

Disclosures: Grants from the National Institutes of Health supported this study. The investigators disclosed consulting and other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Deming Y et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Aug 14. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau2291.

Possible role of enterovirus infection in acute flaccid myelitis cases detected

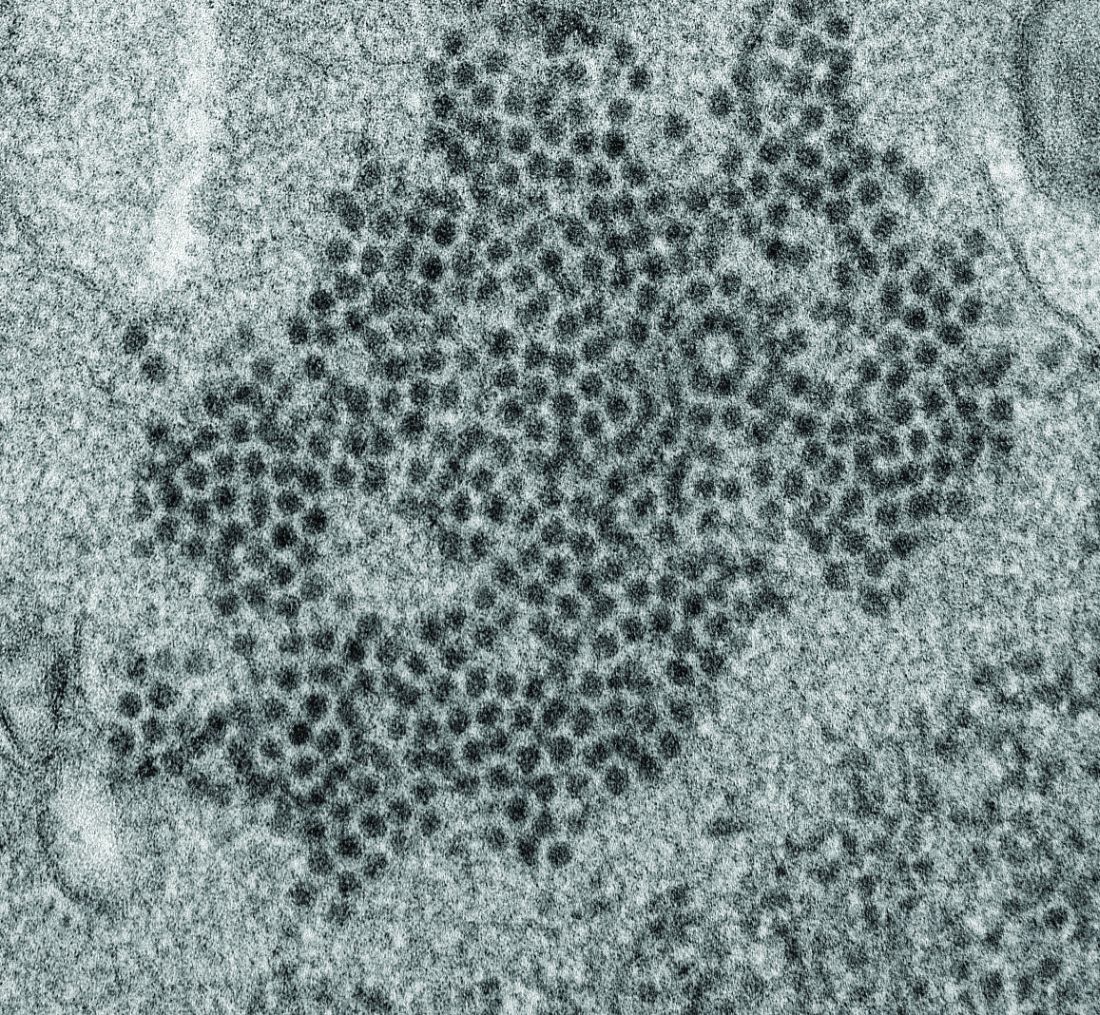

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

High levels of enterovirus (EV) peptides were found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples of individuals with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) that were not present in a variety of control individuals, according to the results of a small study of patients with and without AFM published online in mBio.

In 2018, CSF samples from AFM patients were investigated by viral-capture high-throughput sequencing. These CSF and serum samples, as well as those from multiple controls, were tested for antibodies to human EVs using peptide microarrays, according to Nischay Mishra, PhD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Although EV RNA was confirmed in CSF from only 1 adult AFM case and 1 non-AFM case, antibodies to EV peptides were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), which was a significantly higher rate than in control groups, including non-AFM patients (1 of 5, or 20%), children with Kawasaki disease (0 of 10), and adults with non-AFM CNS diseases (2 of 11, 18%), according to the authors.

In addition, 6 of 14 (43%) CSF samples and 8 of 11 (73%) serum samples from AFM patients were immunoreactive to an EV-D68–specific peptide, whereas samples from the three control groups were not immunoreactive in either CSF or sera. Previous studies have suggested that infection with EV-D68 and EV-A71 may contribute to AFM.

“There have been 570 confirmed cases since CDC began tracking AFM in August 2014. AFM outbreaks were reported to the CDC in 2014, 2016, and 2018. AFM affects the spinal cord and is characterized by the sudden onset of muscle weakness in one or more limbs. Spikes in AFM cases, primarily in children, have coincided in time and location with outbreaks of EV-D68 and a related enterovirus, EV-A71,” according to an NIH media advisory discussing the article.

In particular, as the study authors point out, a potential link to EV-D68 has also been based on the presence of viral RNA in some respiratory and stool specimens and the observation that EV-D68 infection can result in spinal cord infection.

“While other etiologies of AFM continue to be investigated, our study provides further evidence that EV infection may be a factor in AFM. In the absence of direct detection of a pathogen, antibody evidence of pathogen exposure within the CNS can be an important indicator of the underlying cause of disease,” Dr. Mishra and his colleagues added.

“These initial results may provide avenues to further explore how exposure to EV may contribute to AFM as well as the development of diagnostic tools and treatments,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no competing financial interests.

SOURCE: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

FROM MBIO

Key clinical point:

Major finding: EV peptide antibodies were present in 11 of 14 AFM patients (79%), significantly higher than in controls.

Study details: A peptide microarray analysis was performed on CSF and sera from 14 AFM patients, as well as three control groups of 5 pediatric and adult patients with a non-AFM CNS diseases, 10 children with Kawasaki disease, and 10 adult patients with non-AFM CNS diseases.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors reported that they had no conflicts.

Source: Mishra N et al. mBio. 2019 Aug;10(4):e01903-19.

Serum neurofilament light chain level may indicate MS disease activity

according to an investigation published online August 12 in JAMA Neurology. Furthermore, changes in sNfL levels are associated with disability worsening, and sNfL levels may be influenced by treatment. These data support the potential of sNfL as an objective surrogate of ongoing MS disease activity, according to the researchers.

Neuronal and axonal loss increase levels of NfL in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with MS. Previous research indicated that sNfL levels are correlated with CSF levels of NfL and are associated with clinical and imaging measures of disease activity. For the purpose of repeated sampling, collecting blood from patients would be more practical than performing lumbar punctures, said the investigators. No long-term studies of sNfL concentrations and their associations with MS disease outcomes had been performed, however.

Ester Cantó, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and colleagues examined data from the prospective Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) study to assess sNfL as a biomarker of MS disease activity and progression. The ongoing EPIC study is being conducted at UCSF. Dr. Cantó and colleagues analyzed data collected from July 1, 2004, through August 31, 2017, for 607 patients with MS. Participants underwent clinical examinations and serum sample collections annually for 5 years, then at various time points for as long as 12 years. The median follow-up duration was 10 years. The researchers measured sNfL levels with a sensitive single-molecule array platform and compared them with clinical and MRI variables using univariable and multivariable analyses. Dr. Cantó and colleagues chose disability progression, defined as clinically significant worsening on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, and brain fraction atrophy as their primary outcomes.

The population’s mean age was 42.5 years. About 70% of participants were women, and all were of non-Hispanic European descent. At baseline, sNfL levels were significantly associated with EDSS score, MS subtype, and treatment status.

Dr. Cantó and colleagues found a significant interaction between EDSS worsening and change in levels of sNfL over time. Baseline sNfL levels were associated with approximately 11.6% of the variance in participants’ brain fraction atrophy at year 10. When the investigators controlled for sex, age, and disease duration, they found that baseline sNfL levels were associated with 18% of the variance in brain fraction atrophy at year 10. After 5 years’ follow-up, active treatment was associated with lower levels of sNfL. High-efficacy treatments were associated with greater decreases in sNfL levels, compared with platform therapies.

More frequent sample acquisition could provide greater detail about changes in sNfL levels, wrote Dr. Cantó and colleagues. They acknowledged that their study had insufficient power for the researchers to assess the outcomes of individual MS therapies. Other limitations included the lack of data on NfL stability and the lack of a group of healthy controls.

“For an individual patient, the biomarker prognostic power of sNfL level for clinical and MRI outcomes was limited,” said the investigators. “Further prospective studies are necessary to assess the assay’s utility for decision making in individual patients.”

The National Institutes of Health and the U.S. National MS Society supported the study. Several of the investigators received compensation from Novartis, which provided funds for the reagents needed for the single-molecule array assay.

SOURCE: Cantó E et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug. 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2137.

according to an investigation published online August 12 in JAMA Neurology. Furthermore, changes in sNfL levels are associated with disability worsening, and sNfL levels may be influenced by treatment. These data support the potential of sNfL as an objective surrogate of ongoing MS disease activity, according to the researchers.

Neuronal and axonal loss increase levels of NfL in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with MS. Previous research indicated that sNfL levels are correlated with CSF levels of NfL and are associated with clinical and imaging measures of disease activity. For the purpose of repeated sampling, collecting blood from patients would be more practical than performing lumbar punctures, said the investigators. No long-term studies of sNfL concentrations and their associations with MS disease outcomes had been performed, however.

Ester Cantó, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and colleagues examined data from the prospective Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) study to assess sNfL as a biomarker of MS disease activity and progression. The ongoing EPIC study is being conducted at UCSF. Dr. Cantó and colleagues analyzed data collected from July 1, 2004, through August 31, 2017, for 607 patients with MS. Participants underwent clinical examinations and serum sample collections annually for 5 years, then at various time points for as long as 12 years. The median follow-up duration was 10 years. The researchers measured sNfL levels with a sensitive single-molecule array platform and compared them with clinical and MRI variables using univariable and multivariable analyses. Dr. Cantó and colleagues chose disability progression, defined as clinically significant worsening on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, and brain fraction atrophy as their primary outcomes.

The population’s mean age was 42.5 years. About 70% of participants were women, and all were of non-Hispanic European descent. At baseline, sNfL levels were significantly associated with EDSS score, MS subtype, and treatment status.

Dr. Cantó and colleagues found a significant interaction between EDSS worsening and change in levels of sNfL over time. Baseline sNfL levels were associated with approximately 11.6% of the variance in participants’ brain fraction atrophy at year 10. When the investigators controlled for sex, age, and disease duration, they found that baseline sNfL levels were associated with 18% of the variance in brain fraction atrophy at year 10. After 5 years’ follow-up, active treatment was associated with lower levels of sNfL. High-efficacy treatments were associated with greater decreases in sNfL levels, compared with platform therapies.

More frequent sample acquisition could provide greater detail about changes in sNfL levels, wrote Dr. Cantó and colleagues. They acknowledged that their study had insufficient power for the researchers to assess the outcomes of individual MS therapies. Other limitations included the lack of data on NfL stability and the lack of a group of healthy controls.

“For an individual patient, the biomarker prognostic power of sNfL level for clinical and MRI outcomes was limited,” said the investigators. “Further prospective studies are necessary to assess the assay’s utility for decision making in individual patients.”

The National Institutes of Health and the U.S. National MS Society supported the study. Several of the investigators received compensation from Novartis, which provided funds for the reagents needed for the single-molecule array assay.

SOURCE: Cantó E et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug. 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2137.

according to an investigation published online August 12 in JAMA Neurology. Furthermore, changes in sNfL levels are associated with disability worsening, and sNfL levels may be influenced by treatment. These data support the potential of sNfL as an objective surrogate of ongoing MS disease activity, according to the researchers.

Neuronal and axonal loss increase levels of NfL in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with MS. Previous research indicated that sNfL levels are correlated with CSF levels of NfL and are associated with clinical and imaging measures of disease activity. For the purpose of repeated sampling, collecting blood from patients would be more practical than performing lumbar punctures, said the investigators. No long-term studies of sNfL concentrations and their associations with MS disease outcomes had been performed, however.

Ester Cantó, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and colleagues examined data from the prospective Expression, Proteomics, Imaging, Clinical (EPIC) study to assess sNfL as a biomarker of MS disease activity and progression. The ongoing EPIC study is being conducted at UCSF. Dr. Cantó and colleagues analyzed data collected from July 1, 2004, through August 31, 2017, for 607 patients with MS. Participants underwent clinical examinations and serum sample collections annually for 5 years, then at various time points for as long as 12 years. The median follow-up duration was 10 years. The researchers measured sNfL levels with a sensitive single-molecule array platform and compared them with clinical and MRI variables using univariable and multivariable analyses. Dr. Cantó and colleagues chose disability progression, defined as clinically significant worsening on the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score, and brain fraction atrophy as their primary outcomes.

The population’s mean age was 42.5 years. About 70% of participants were women, and all were of non-Hispanic European descent. At baseline, sNfL levels were significantly associated with EDSS score, MS subtype, and treatment status.

Dr. Cantó and colleagues found a significant interaction between EDSS worsening and change in levels of sNfL over time. Baseline sNfL levels were associated with approximately 11.6% of the variance in participants’ brain fraction atrophy at year 10. When the investigators controlled for sex, age, and disease duration, they found that baseline sNfL levels were associated with 18% of the variance in brain fraction atrophy at year 10. After 5 years’ follow-up, active treatment was associated with lower levels of sNfL. High-efficacy treatments were associated with greater decreases in sNfL levels, compared with platform therapies.

More frequent sample acquisition could provide greater detail about changes in sNfL levels, wrote Dr. Cantó and colleagues. They acknowledged that their study had insufficient power for the researchers to assess the outcomes of individual MS therapies. Other limitations included the lack of data on NfL stability and the lack of a group of healthy controls.

“For an individual patient, the biomarker prognostic power of sNfL level for clinical and MRI outcomes was limited,” said the investigators. “Further prospective studies are necessary to assess the assay’s utility for decision making in individual patients.”

The National Institutes of Health and the U.S. National MS Society supported the study. Several of the investigators received compensation from Novartis, which provided funds for the reagents needed for the single-molecule array assay.

SOURCE: Cantó E et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug. 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2137.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Serum neurofilament light chain level has potential as a surrogate of ongoing MS disease activity.

Major finding: Serum neurofilament light chain level is associated with brain fraction atrophy.

Study details: An ongoing, prospective, observational study of 607 patients with MS.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health and the U.S. National MS Society supported the study. Several of the investigators received compensation from Novartis, which provided funds for the reagents needed for the single-molecule array assay.

Source: Cantó E et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Aug 12. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2137.

Midlife hypertension is associated with subsequent risk of dementia

Uncontrolled hypertension among individuals aged 45-65 years of age is associated with an increased risk of subsequent dementia, according to a relatively large prospective population-based cohort study that followed patients for almost 30 years.

Even though previously published studies have not conclusively linked blood pressure control with a reduction in dementia risk, a second study, published simultaneously, did link blood pressure control with a smaller increase in white matter lesions, which are a marker of dementia risk. However, a reduction in total brain volume that accompanied this protection raised concern.

In the first of the two reports published Aug. 13 in JAMA, individuals 45-65 years of age participating in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study were followed for cognitive function in relation to blood pressure. The baseline visit took place in 1987-1989. Cognitive function was also evaluated at the fifth visit, which took place in 2011-2013, and the sixth visit, which took place in 2016-2017.

At the sixth visit, the incidence of dementia among patients who were normotensive at baseline and also normotensive at the fifth visit was 1.31 per 100 person-years. For those with hypertension (greater than 140/90 mm Hg) at the fifth visit but normotensive at baseline, the incidence was 1.99 per 100 patient-years. For those with hypertension at both time points, the incidence was 4.26 per 100 patient-years.

When translated into hazard ratios, those with midlife and late-life hypertension were nearly 50% more likely to develop dementia (HR, 1.49) relative to those who remained normotensive. For those who had only midlife hypertension, the risk was also significantly increased (HR, 1.41) relative to those who remained normotensive at both time points.

Those with midlife hypertension but late-life hypotension were also found to be at greater risk of dementia (HR, 1.62) relative to those who remained normotensive.

These data support the premise that uncontrolled midlife hypertension increases risk of dementia but do not touch on whether blood pressure reductions reduce this risk. However, a second study published simultaneously provided at least some evidence that blood pressure control might offer some protection.

In this report, which is a substudy of the previously published Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) MIND trial, brain volume changes were evaluated via MRI in 449 of the more than 2,000 patients included in the previously published trial (Williamson JD et al. JAMA. 2019;321[6]:553-61).

After a median 3.4 years of follow-up, mean white matter lesion volume increased only 0.92 cm3 in patients receiving intensive systolic blood pressure control, defined as less than 120 mm Hg, versus 1.45 cm3 in those with higher systolic blood pressures.

These substudy data are encouraging, but it is important to recognize that the previously published and larger SPRINT MIND trial did not achieve its endpoint. In that study, the protection against dementia was nonsignificant (HR, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-1.04).

In addition, the lower loss in white matter volume with intensive blood pressure lowering in the MRI substudy was accompanied with a greater loss in total brain volume (–30.6 vs. –26.9 cm3), which is considered a potentially negative effect.

As a result, the picture for risk management remains unclear, according to an editorial that accompanied publication of both studies.

“The important clinical question is whether changes of a few cubic millimeters in white matter hyperintensity volume or brain make a difference on brain function,” observed the author of the editorial, Shyam Prabhakaran, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of Chicago.

He believes that there are several findings from both studies that are “encouraging” in regard to blood pressure control for the prevention of dementia, but he also listed many unanswered questions, including why benefits observed to date have been so modest. He speculated that meaningful clinical benefits might depend on a multimodal approach that includes modification of other vascular risk factors, such as elevated lipids.

He also suggested that many issues regarding intensive blood pressure control for preventing dementia are unresolved, suggesting the need for more studies.

Not least, “later blood-pressure lowering interventions require careful monitoring for the potential cognitive harm associated with late-life hypotension,” Dr. Prabhakaran noted. Calling the effects of blood pressure control on brain health “nuanced,” he concluded that there is an opportunity for blood pressure modifications to prevent dementia, but stressed that optimal blood pressure targets for the purposes of preventing dementia are unknown.

The ARIC and SPRINT studies are supported by the National Institutes of Health. Several authors reported relationships with industry but no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCES: Walker KA et al. JAMA. 2019;322(6):535-45; SPRINT MIND investigators. JAMA. 2019;322(6):524-34; Prabhakaran S. JAMA. 2019;322(6):512-3

Uncontrolled hypertension among individuals aged 45-65 years of age is associated with an increased risk of subsequent dementia, according to a relatively large prospective population-based cohort study that followed patients for almost 30 years.

Even though previously published studies have not conclusively linked blood pressure control with a reduction in dementia risk, a second study, published simultaneously, did link blood pressure control with a smaller increase in white matter lesions, which are a marker of dementia risk. However, a reduction in total brain volume that accompanied this protection raised concern.

In the first of the two reports published Aug. 13 in JAMA, individuals 45-65 years of age participating in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study were followed for cognitive function in relation to blood pressure. The baseline visit took place in 1987-1989. Cognitive function was also evaluated at the fifth visit, which took place in 2011-2013, and the sixth visit, which took place in 2016-2017.

At the sixth visit, the incidence of dementia among patients who were normotensive at baseline and also normotensive at the fifth visit was 1.31 per 100 person-years. For those with hypertension (greater than 140/90 mm Hg) at the fifth visit but normotensive at baseline, the incidence was 1.99 per 100 patient-years. For those with hypertension at both time points, the incidence was 4.26 per 100 patient-years.

When translated into hazard ratios, those with midlife and late-life hypertension were nearly 50% more likely to develop dementia (HR, 1.49) relative to those who remained normotensive. For those who had only midlife hypertension, the risk was also significantly increased (HR, 1.41) relative to those who remained normotensive at both time points.

Those with midlife hypertension but late-life hypotension were also found to be at greater risk of dementia (HR, 1.62) relative to those who remained normotensive.

These data support the premise that uncontrolled midlife hypertension increases risk of dementia but do not touch on whether blood pressure reductions reduce this risk. However, a second study published simultaneously provided at least some evidence that blood pressure control might offer some protection.

In this report, which is a substudy of the previously published Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) MIND trial, brain volume changes were evaluated via MRI in 449 of the more than 2,000 patients included in the previously published trial (Williamson JD et al. JAMA. 2019;321[6]:553-61).

After a median 3.4 years of follow-up, mean white matter lesion volume increased only 0.92 cm3 in patients receiving intensive systolic blood pressure control, defined as less than 120 mm Hg, versus 1.45 cm3 in those with higher systolic blood pressures.

These substudy data are encouraging, but it is important to recognize that the previously published and larger SPRINT MIND trial did not achieve its endpoint. In that study, the protection against dementia was nonsignificant (HR, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-1.04).

In addition, the lower loss in white matter volume with intensive blood pressure lowering in the MRI substudy was accompanied with a greater loss in total brain volume (–30.6 vs. –26.9 cm3), which is considered a potentially negative effect.

As a result, the picture for risk management remains unclear, according to an editorial that accompanied publication of both studies.

“The important clinical question is whether changes of a few cubic millimeters in white matter hyperintensity volume or brain make a difference on brain function,” observed the author of the editorial, Shyam Prabhakaran, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of Chicago.

He believes that there are several findings from both studies that are “encouraging” in regard to blood pressure control for the prevention of dementia, but he also listed many unanswered questions, including why benefits observed to date have been so modest. He speculated that meaningful clinical benefits might depend on a multimodal approach that includes modification of other vascular risk factors, such as elevated lipids.

He also suggested that many issues regarding intensive blood pressure control for preventing dementia are unresolved, suggesting the need for more studies.

Not least, “later blood-pressure lowering interventions require careful monitoring for the potential cognitive harm associated with late-life hypotension,” Dr. Prabhakaran noted. Calling the effects of blood pressure control on brain health “nuanced,” he concluded that there is an opportunity for blood pressure modifications to prevent dementia, but stressed that optimal blood pressure targets for the purposes of preventing dementia are unknown.

The ARIC and SPRINT studies are supported by the National Institutes of Health. Several authors reported relationships with industry but no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCES: Walker KA et al. JAMA. 2019;322(6):535-45; SPRINT MIND investigators. JAMA. 2019;322(6):524-34; Prabhakaran S. JAMA. 2019;322(6):512-3

Uncontrolled hypertension among individuals aged 45-65 years of age is associated with an increased risk of subsequent dementia, according to a relatively large prospective population-based cohort study that followed patients for almost 30 years.

Even though previously published studies have not conclusively linked blood pressure control with a reduction in dementia risk, a second study, published simultaneously, did link blood pressure control with a smaller increase in white matter lesions, which are a marker of dementia risk. However, a reduction in total brain volume that accompanied this protection raised concern.

In the first of the two reports published Aug. 13 in JAMA, individuals 45-65 years of age participating in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study were followed for cognitive function in relation to blood pressure. The baseline visit took place in 1987-1989. Cognitive function was also evaluated at the fifth visit, which took place in 2011-2013, and the sixth visit, which took place in 2016-2017.

At the sixth visit, the incidence of dementia among patients who were normotensive at baseline and also normotensive at the fifth visit was 1.31 per 100 person-years. For those with hypertension (greater than 140/90 mm Hg) at the fifth visit but normotensive at baseline, the incidence was 1.99 per 100 patient-years. For those with hypertension at both time points, the incidence was 4.26 per 100 patient-years.

When translated into hazard ratios, those with midlife and late-life hypertension were nearly 50% more likely to develop dementia (HR, 1.49) relative to those who remained normotensive. For those who had only midlife hypertension, the risk was also significantly increased (HR, 1.41) relative to those who remained normotensive at both time points.

Those with midlife hypertension but late-life hypotension were also found to be at greater risk of dementia (HR, 1.62) relative to those who remained normotensive.

These data support the premise that uncontrolled midlife hypertension increases risk of dementia but do not touch on whether blood pressure reductions reduce this risk. However, a second study published simultaneously provided at least some evidence that blood pressure control might offer some protection.

In this report, which is a substudy of the previously published Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) MIND trial, brain volume changes were evaluated via MRI in 449 of the more than 2,000 patients included in the previously published trial (Williamson JD et al. JAMA. 2019;321[6]:553-61).

After a median 3.4 years of follow-up, mean white matter lesion volume increased only 0.92 cm3 in patients receiving intensive systolic blood pressure control, defined as less than 120 mm Hg, versus 1.45 cm3 in those with higher systolic blood pressures.

These substudy data are encouraging, but it is important to recognize that the previously published and larger SPRINT MIND trial did not achieve its endpoint. In that study, the protection against dementia was nonsignificant (HR, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-1.04).

In addition, the lower loss in white matter volume with intensive blood pressure lowering in the MRI substudy was accompanied with a greater loss in total brain volume (–30.6 vs. –26.9 cm3), which is considered a potentially negative effect.

As a result, the picture for risk management remains unclear, according to an editorial that accompanied publication of both studies.

“The important clinical question is whether changes of a few cubic millimeters in white matter hyperintensity volume or brain make a difference on brain function,” observed the author of the editorial, Shyam Prabhakaran, MD, of the department of neurology at the University of Chicago.

He believes that there are several findings from both studies that are “encouraging” in regard to blood pressure control for the prevention of dementia, but he also listed many unanswered questions, including why benefits observed to date have been so modest. He speculated that meaningful clinical benefits might depend on a multimodal approach that includes modification of other vascular risk factors, such as elevated lipids.

He also suggested that many issues regarding intensive blood pressure control for preventing dementia are unresolved, suggesting the need for more studies.

Not least, “later blood-pressure lowering interventions require careful monitoring for the potential cognitive harm associated with late-life hypotension,” Dr. Prabhakaran noted. Calling the effects of blood pressure control on brain health “nuanced,” he concluded that there is an opportunity for blood pressure modifications to prevent dementia, but stressed that optimal blood pressure targets for the purposes of preventing dementia are unknown.

The ARIC and SPRINT studies are supported by the National Institutes of Health. Several authors reported relationships with industry but no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

SOURCES: Walker KA et al. JAMA. 2019;322(6):535-45; SPRINT MIND investigators. JAMA. 2019;322(6):524-34; Prabhakaran S. JAMA. 2019;322(6):512-3

FROM JAMA

Ketogenic diets are what’s cooking for drug-refractory epilepsy

BANGKOK – For a form of epilepsy treatment that’s been around since the 1920s, ketogenic diet therapy has lately been the focus of a surprising wealth of clinical research and development, Suvasini Sharma, MD, observed at the International Epilepsy Congress.

This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is now well established as a valid and effective treatment option for children and adults with drug-refractory epilepsy who aren’t candidates for surgery. That’s about a third of all epilepsy patients. And as the recently overhauled pediatric ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) best practice consensus guidelines emphasize, KDT should be strongly considered after two antiepileptic drugs have failed, and even earlier for several epilepsy syndromes, noted Dr. Sharma, a pediatric neurologist at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital in New Delhi, and a coauthor of the updated guidelines.

“The consensus guidelines recommend that you start thinking about the diet early, without waiting for every drug to fail,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

Among the KDT-related topics she highlighted were the recently revised best practice consensus guidelines; an expanding role for KDT in infants, critical care settings, and in epileptic encephalopathies; mounting evidence that KDT provides additional benefits beyond seizure control; and promising new alternative diet therapies. She also described the challenges of using KDT in a low-resource nation such as India, where most of the 1.3 billion people shop in markets where food isn’t packaged with the nutritional content labels essential to traditional KDTs, and low literacy is common.

KDT best practice guidelines

The latest guidelines, which include the details of standardized KDT protocols as well as a summary of recent translational research into mechanisms of action, replace the previous 10-year-old version. Flexibility is now the watchword. While the classic KDT was started as an inpatient intervention involving several days of fasting followed by multiday gradual reintroduction of calories, that approach is now deemed optional (Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3[2]:175-92).

“By and large, the trend now is going to nonfasting initiation on an outpatient basis, but with more stringent monitoring,” according to Dr. Sharma.

The guidelines note that while the research literature shows that, on average, KDT results in about a 50% chance of at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, there are a dozen specific conditions with 70% or greater responder rates: infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, Dravet syndrome, glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut 1DS), pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHD), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Ohtahara syndrome, complex I mitochondrial disorders, Angelman syndrome, and children with gastrostomy tubes. For Glut1DS and PDHD, KDTs should be considered the treatment of first choice.

Traditionally, KDTs weren’t recommended for children younger than age 2 years. There were concerns that maintaining ketosis and meeting growth requirements were contradictory goals. That’s no longer believed to be so. Indeed, current evidence shows that KDT is highly effective and well tolerated in infants with refractory epilepsy. European guidelines address patient selection, pre-KDT counseling, preferred methods of initiation and KDT discontinuation, and other key issues (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016 Nov;20[6]:798-809).

The guidelines recognize four major, well-studied types of KDT: the classic long-chain triglyceride-centric diet; the medium-chain triglyceride diet; the more user-friendly modified Atkins diet; and low glycemic index therapy. Except in children younger than 2 years old, who should be started on the classic KDT, the consensus panel recommended that the specific KDT selected should be based on the family and child situation and the expertise at the local KDT center. Perceived differences in efficacy between the diets aren’t supported by persuasive evidence.

KDT benefits beyond seizure control

“Most of us who work in the diet scene are aware that patients often report increased alertness, and sometimes improved cognition,” said Dr. Sharma.

That subjective experience is now supported by evidence from a randomized, controlled trial. Dutch investigators who randomized 50 drug-refractory pediatric epilepsy patients to KDT or usual care documented a positive impact of the diet therapy on cognitive activation, mood, and anxious behavior (Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Jul;60:153-7).

More recently, a systematic review showed that while subjective assessments support claims of improved alertness, attention, and global cognition in patients on KDT for refractory epilepsy, structured neuropsychologic testing confirms the enhanced alertness but without significantly improved global cognition. The investigators reported that the improvements were unrelated to decreases in medication, the type of KDT or age at its introduction, or sleep improvement. Rather, the benefits appeared to be due to a combination of seizure reduction and direct effects of KDT on cognition (Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Oct;87:69-77).

There is also encouraging preliminary evidence of a possible protective effect of KDT against sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in a mouse model (Epilepsia. 2016 Aug;57[8]:e178-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.13444).

The use of KDT in critical care settings

Investigators from the pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG) reported that 10 of 14 patients with convulsive refractory status epilepticus achieved EEG seizure resolution within 7 days after starting KDT. Moreover, 11 patients were able to be weaned off their continuous infusions within 14 days of starting KDT. Treatment-emergent gastroparesis and hypertriglyceridemia occurred in three patients (Epilepsy Res. 2018 Aug;144:1-6).

“It was reasonably well tolerated, but they started it quite late – a median of 13 days after onset of refractory status epilepticus. It should come much earlier on our list of therapies. We shouldn’t be waiting 2 weeks before going to the ketogenic diet, because we can diagnose refractory status epilepticus within 48 hours after arrival in the ICU most of the time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Austrian investigators have pioneered the use of intravenous KDT as a bridge when oral therapy is temporarily impossible because of status epilepticus, surgery, or other reasons. They reported that parental KDT with fat intake of 3.5-4 g/kg per day was safe and effective in their series of 17 young children with epilepsy (Epilepsia Open. 2017 Nov 16;3[1]:30-9).

The future: nonketogenic diet therapies

KDT in its various forms is just too demanding and restrictive for some patients. Nonketotic alternatives are being explored.

Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride in the form of an edible, odorless, tasteless oil. Its mechanism of action is by anaplerosis: that is, energy generation via replenishment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. After demonstration of neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects in several mouse models, Australian investigators conducted a pilot study of 30- to 100-mL/day of oral triheptanoin as add-on therapy in 12 children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Eight of the 12 took triheptanoin for longer than 12 weeks, and 5 of those 8 experienced a sustained greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, including 1 who remained seizure free for 30 weeks. Seven children had diarrhea or other GI side effects (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018 Nov;22[6]:1074-80).

Parisian investigators have developed a nonketotic, palatable combination of amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids with a low ratio of fat to protein-plus-carbohydrates that provided potent protection against seizures in a mouse model. This suggests that the traditional 4:1 ratio sought in KDT isn’t necessary for robust seizure reduction (Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 14;7[1]:5496).

“This is probably going to be the future of nutritional therapy in epilepsy,” Dr. Sharma predicted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

BANGKOK – For a form of epilepsy treatment that’s been around since the 1920s, ketogenic diet therapy has lately been the focus of a surprising wealth of clinical research and development, Suvasini Sharma, MD, observed at the International Epilepsy Congress.

This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is now well established as a valid and effective treatment option for children and adults with drug-refractory epilepsy who aren’t candidates for surgery. That’s about a third of all epilepsy patients. And as the recently overhauled pediatric ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) best practice consensus guidelines emphasize, KDT should be strongly considered after two antiepileptic drugs have failed, and even earlier for several epilepsy syndromes, noted Dr. Sharma, a pediatric neurologist at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital in New Delhi, and a coauthor of the updated guidelines.

“The consensus guidelines recommend that you start thinking about the diet early, without waiting for every drug to fail,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

Among the KDT-related topics she highlighted were the recently revised best practice consensus guidelines; an expanding role for KDT in infants, critical care settings, and in epileptic encephalopathies; mounting evidence that KDT provides additional benefits beyond seizure control; and promising new alternative diet therapies. She also described the challenges of using KDT in a low-resource nation such as India, where most of the 1.3 billion people shop in markets where food isn’t packaged with the nutritional content labels essential to traditional KDTs, and low literacy is common.

KDT best practice guidelines

The latest guidelines, which include the details of standardized KDT protocols as well as a summary of recent translational research into mechanisms of action, replace the previous 10-year-old version. Flexibility is now the watchword. While the classic KDT was started as an inpatient intervention involving several days of fasting followed by multiday gradual reintroduction of calories, that approach is now deemed optional (Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3[2]:175-92).

“By and large, the trend now is going to nonfasting initiation on an outpatient basis, but with more stringent monitoring,” according to Dr. Sharma.

The guidelines note that while the research literature shows that, on average, KDT results in about a 50% chance of at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, there are a dozen specific conditions with 70% or greater responder rates: infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, Dravet syndrome, glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut 1DS), pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHD), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Ohtahara syndrome, complex I mitochondrial disorders, Angelman syndrome, and children with gastrostomy tubes. For Glut1DS and PDHD, KDTs should be considered the treatment of first choice.

Traditionally, KDTs weren’t recommended for children younger than age 2 years. There were concerns that maintaining ketosis and meeting growth requirements were contradictory goals. That’s no longer believed to be so. Indeed, current evidence shows that KDT is highly effective and well tolerated in infants with refractory epilepsy. European guidelines address patient selection, pre-KDT counseling, preferred methods of initiation and KDT discontinuation, and other key issues (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016 Nov;20[6]:798-809).

The guidelines recognize four major, well-studied types of KDT: the classic long-chain triglyceride-centric diet; the medium-chain triglyceride diet; the more user-friendly modified Atkins diet; and low glycemic index therapy. Except in children younger than 2 years old, who should be started on the classic KDT, the consensus panel recommended that the specific KDT selected should be based on the family and child situation and the expertise at the local KDT center. Perceived differences in efficacy between the diets aren’t supported by persuasive evidence.

KDT benefits beyond seizure control

“Most of us who work in the diet scene are aware that patients often report increased alertness, and sometimes improved cognition,” said Dr. Sharma.

That subjective experience is now supported by evidence from a randomized, controlled trial. Dutch investigators who randomized 50 drug-refractory pediatric epilepsy patients to KDT or usual care documented a positive impact of the diet therapy on cognitive activation, mood, and anxious behavior (Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Jul;60:153-7).

More recently, a systematic review showed that while subjective assessments support claims of improved alertness, attention, and global cognition in patients on KDT for refractory epilepsy, structured neuropsychologic testing confirms the enhanced alertness but without significantly improved global cognition. The investigators reported that the improvements were unrelated to decreases in medication, the type of KDT or age at its introduction, or sleep improvement. Rather, the benefits appeared to be due to a combination of seizure reduction and direct effects of KDT on cognition (Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Oct;87:69-77).

There is also encouraging preliminary evidence of a possible protective effect of KDT against sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in a mouse model (Epilepsia. 2016 Aug;57[8]:e178-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.13444).

The use of KDT in critical care settings

Investigators from the pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG) reported that 10 of 14 patients with convulsive refractory status epilepticus achieved EEG seizure resolution within 7 days after starting KDT. Moreover, 11 patients were able to be weaned off their continuous infusions within 14 days of starting KDT. Treatment-emergent gastroparesis and hypertriglyceridemia occurred in three patients (Epilepsy Res. 2018 Aug;144:1-6).

“It was reasonably well tolerated, but they started it quite late – a median of 13 days after onset of refractory status epilepticus. It should come much earlier on our list of therapies. We shouldn’t be waiting 2 weeks before going to the ketogenic diet, because we can diagnose refractory status epilepticus within 48 hours after arrival in the ICU most of the time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Austrian investigators have pioneered the use of intravenous KDT as a bridge when oral therapy is temporarily impossible because of status epilepticus, surgery, or other reasons. They reported that parental KDT with fat intake of 3.5-4 g/kg per day was safe and effective in their series of 17 young children with epilepsy (Epilepsia Open. 2017 Nov 16;3[1]:30-9).

The future: nonketogenic diet therapies

KDT in its various forms is just too demanding and restrictive for some patients. Nonketotic alternatives are being explored.

Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride in the form of an edible, odorless, tasteless oil. Its mechanism of action is by anaplerosis: that is, energy generation via replenishment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. After demonstration of neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects in several mouse models, Australian investigators conducted a pilot study of 30- to 100-mL/day of oral triheptanoin as add-on therapy in 12 children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Eight of the 12 took triheptanoin for longer than 12 weeks, and 5 of those 8 experienced a sustained greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, including 1 who remained seizure free for 30 weeks. Seven children had diarrhea or other GI side effects (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018 Nov;22[6]:1074-80).

Parisian investigators have developed a nonketotic, palatable combination of amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids with a low ratio of fat to protein-plus-carbohydrates that provided potent protection against seizures in a mouse model. This suggests that the traditional 4:1 ratio sought in KDT isn’t necessary for robust seizure reduction (Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 14;7[1]:5496).

“This is probably going to be the future of nutritional therapy in epilepsy,” Dr. Sharma predicted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

BANGKOK – For a form of epilepsy treatment that’s been around since the 1920s, ketogenic diet therapy has lately been the focus of a surprising wealth of clinical research and development, Suvasini Sharma, MD, observed at the International Epilepsy Congress.

This high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet is now well established as a valid and effective treatment option for children and adults with drug-refractory epilepsy who aren’t candidates for surgery. That’s about a third of all epilepsy patients. And as the recently overhauled pediatric ketogenic diet therapy (KDT) best practice consensus guidelines emphasize, KDT should be strongly considered after two antiepileptic drugs have failed, and even earlier for several epilepsy syndromes, noted Dr. Sharma, a pediatric neurologist at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital in New Delhi, and a coauthor of the updated guidelines.

“The consensus guidelines recommend that you start thinking about the diet early, without waiting for every drug to fail,” she said at the congress, sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

Among the KDT-related topics she highlighted were the recently revised best practice consensus guidelines; an expanding role for KDT in infants, critical care settings, and in epileptic encephalopathies; mounting evidence that KDT provides additional benefits beyond seizure control; and promising new alternative diet therapies. She also described the challenges of using KDT in a low-resource nation such as India, where most of the 1.3 billion people shop in markets where food isn’t packaged with the nutritional content labels essential to traditional KDTs, and low literacy is common.

KDT best practice guidelines

The latest guidelines, which include the details of standardized KDT protocols as well as a summary of recent translational research into mechanisms of action, replace the previous 10-year-old version. Flexibility is now the watchword. While the classic KDT was started as an inpatient intervention involving several days of fasting followed by multiday gradual reintroduction of calories, that approach is now deemed optional (Epilepsia Open. 2018 May 21;3[2]:175-92).

“By and large, the trend now is going to nonfasting initiation on an outpatient basis, but with more stringent monitoring,” according to Dr. Sharma.

The guidelines note that while the research literature shows that, on average, KDT results in about a 50% chance of at least a 50% reduction in seizure frequency in patients with drug-refractory epilepsy, there are a dozen specific conditions with 70% or greater responder rates: infantile spasms, tuberous sclerosis, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, Dravet syndrome, glucose transporter 1 deficiency syndrome (Glut 1DS), pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency (PDHD), febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES), super-refractory status epilepticus (SRSE), Ohtahara syndrome, complex I mitochondrial disorders, Angelman syndrome, and children with gastrostomy tubes. For Glut1DS and PDHD, KDTs should be considered the treatment of first choice.

Traditionally, KDTs weren’t recommended for children younger than age 2 years. There were concerns that maintaining ketosis and meeting growth requirements were contradictory goals. That’s no longer believed to be so. Indeed, current evidence shows that KDT is highly effective and well tolerated in infants with refractory epilepsy. European guidelines address patient selection, pre-KDT counseling, preferred methods of initiation and KDT discontinuation, and other key issues (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016 Nov;20[6]:798-809).

The guidelines recognize four major, well-studied types of KDT: the classic long-chain triglyceride-centric diet; the medium-chain triglyceride diet; the more user-friendly modified Atkins diet; and low glycemic index therapy. Except in children younger than 2 years old, who should be started on the classic KDT, the consensus panel recommended that the specific KDT selected should be based on the family and child situation and the expertise at the local KDT center. Perceived differences in efficacy between the diets aren’t supported by persuasive evidence.

KDT benefits beyond seizure control

“Most of us who work in the diet scene are aware that patients often report increased alertness, and sometimes improved cognition,” said Dr. Sharma.

That subjective experience is now supported by evidence from a randomized, controlled trial. Dutch investigators who randomized 50 drug-refractory pediatric epilepsy patients to KDT or usual care documented a positive impact of the diet therapy on cognitive activation, mood, and anxious behavior (Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Jul;60:153-7).

More recently, a systematic review showed that while subjective assessments support claims of improved alertness, attention, and global cognition in patients on KDT for refractory epilepsy, structured neuropsychologic testing confirms the enhanced alertness but without significantly improved global cognition. The investigators reported that the improvements were unrelated to decreases in medication, the type of KDT or age at its introduction, or sleep improvement. Rather, the benefits appeared to be due to a combination of seizure reduction and direct effects of KDT on cognition (Epilepsy Behav. 2018 Oct;87:69-77).

There is also encouraging preliminary evidence of a possible protective effect of KDT against sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in a mouse model (Epilepsia. 2016 Aug;57[8]:e178-82. doi: 10.1111/epi.13444).

The use of KDT in critical care settings

Investigators from the pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG) reported that 10 of 14 patients with convulsive refractory status epilepticus achieved EEG seizure resolution within 7 days after starting KDT. Moreover, 11 patients were able to be weaned off their continuous infusions within 14 days of starting KDT. Treatment-emergent gastroparesis and hypertriglyceridemia occurred in three patients (Epilepsy Res. 2018 Aug;144:1-6).

“It was reasonably well tolerated, but they started it quite late – a median of 13 days after onset of refractory status epilepticus. It should come much earlier on our list of therapies. We shouldn’t be waiting 2 weeks before going to the ketogenic diet, because we can diagnose refractory status epilepticus within 48 hours after arrival in the ICU most of the time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Austrian investigators have pioneered the use of intravenous KDT as a bridge when oral therapy is temporarily impossible because of status epilepticus, surgery, or other reasons. They reported that parental KDT with fat intake of 3.5-4 g/kg per day was safe and effective in their series of 17 young children with epilepsy (Epilepsia Open. 2017 Nov 16;3[1]:30-9).

The future: nonketogenic diet therapies

KDT in its various forms is just too demanding and restrictive for some patients. Nonketotic alternatives are being explored.

Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride in the form of an edible, odorless, tasteless oil. Its mechanism of action is by anaplerosis: that is, energy generation via replenishment of the tricarboxylic acid cycle. After demonstration of neuroprotective and anticonvulsant effects in several mouse models, Australian investigators conducted a pilot study of 30- to 100-mL/day of oral triheptanoin as add-on therapy in 12 children with drug-refractory epilepsy. Eight of the 12 took triheptanoin for longer than 12 weeks, and 5 of those 8 experienced a sustained greater than 50% reduction in seizure frequency, including 1 who remained seizure free for 30 weeks. Seven children had diarrhea or other GI side effects (Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018 Nov;22[6]:1074-80).

Parisian investigators have developed a nonketotic, palatable combination of amino acids, carbohydrates, and fatty acids with a low ratio of fat to protein-plus-carbohydrates that provided potent protection against seizures in a mouse model. This suggests that the traditional 4:1 ratio sought in KDT isn’t necessary for robust seizure reduction (Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 14;7[1]:5496).

“This is probably going to be the future of nutritional therapy in epilepsy,” Dr. Sharma predicted.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

REPORTING FROM IEC 2019

Asthma hospitalization in kids linked with doubled migraine incidence

when compared with a similar pediatric population without asthma. The finding is based on an analysis of more than 11 million U.S. pediatric hospitalizations over the course of a decade.

Among children and adolescents aged 3-21 years who were hospitalized for asthma, migraine rates were significantly higher among girls, adolescents, and whites, compared with boys, children aged 12 years or younger, and nonwhites, respectively, in a trio of adjusted analyses, Riddhiben S. Patel, MD, and associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“Our hope is that, by establishing an association between childhood asthma and migraine, [these children] may be more easily screened for, diagnosed, and treated early by providers,” wrote Dr. Patel, a pediatric neurologist and headache specialist at the University of Mississippi, Jackson, and associates.

Their analysis used administrative billing data collected by the Kids’ Inpatient Database, maintained by the U.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The project includes a representative national sample of about 3 million pediatric hospital discharges every 3 years. The study used data from 11,483,103 hospitalizations of children and adolescents aged 3-21 years during 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012, and found an overall hospitalization rate of 0.8% billed for migraine. For patients also hospitalized with a billing code for asthma, the rate jumped to 1.36%, a 120% statistically significant relative increase in migraine hospitalizations after adjustment for baseline demographic differences, the researchers said.

Among the children and adolescents hospitalized with an asthma billing code, the relative rate of also having a billing code for migraine after adjustment was a statistically significant 80% higher in girls, compared with boys, a statistically significant 7% higher in adolescents, compared with children 12 years or younger, and was significantly reduced by a relative 45% rate in nonwhites, compared with whites.

The mechanisms behind these associations are not known, but could involve mast-cell degranulation, autonomic dysfunction, or shared genetic or environmental etiologic factors, the authors said.

Dr. Patel reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel RS et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract P78.

when compared with a similar pediatric population without asthma. The finding is based on an analysis of more than 11 million U.S. pediatric hospitalizations over the course of a decade.

Among children and adolescents aged 3-21 years who were hospitalized for asthma, migraine rates were significantly higher among girls, adolescents, and whites, compared with boys, children aged 12 years or younger, and nonwhites, respectively, in a trio of adjusted analyses, Riddhiben S. Patel, MD, and associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“Our hope is that, by establishing an association between childhood asthma and migraine, [these children] may be more easily screened for, diagnosed, and treated early by providers,” wrote Dr. Patel, a pediatric neurologist and headache specialist at the University of Mississippi, Jackson, and associates.

Their analysis used administrative billing data collected by the Kids’ Inpatient Database, maintained by the U.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The project includes a representative national sample of about 3 million pediatric hospital discharges every 3 years. The study used data from 11,483,103 hospitalizations of children and adolescents aged 3-21 years during 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012, and found an overall hospitalization rate of 0.8% billed for migraine. For patients also hospitalized with a billing code for asthma, the rate jumped to 1.36%, a 120% statistically significant relative increase in migraine hospitalizations after adjustment for baseline demographic differences, the researchers said.

Among the children and adolescents hospitalized with an asthma billing code, the relative rate of also having a billing code for migraine after adjustment was a statistically significant 80% higher in girls, compared with boys, a statistically significant 7% higher in adolescents, compared with children 12 years or younger, and was significantly reduced by a relative 45% rate in nonwhites, compared with whites.

The mechanisms behind these associations are not known, but could involve mast-cell degranulation, autonomic dysfunction, or shared genetic or environmental etiologic factors, the authors said.

Dr. Patel reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel RS et al. Headache. 2019 June;59[S1]:1-208, Abstract P78.

when compared with a similar pediatric population without asthma. The finding is based on an analysis of more than 11 million U.S. pediatric hospitalizations over the course of a decade.

Among children and adolescents aged 3-21 years who were hospitalized for asthma, migraine rates were significantly higher among girls, adolescents, and whites, compared with boys, children aged 12 years or younger, and nonwhites, respectively, in a trio of adjusted analyses, Riddhiben S. Patel, MD, and associates reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American Headache Society.

“Our hope is that, by establishing an association between childhood asthma and migraine, [these children] may be more easily screened for, diagnosed, and treated early by providers,” wrote Dr. Patel, a pediatric neurologist and headache specialist at the University of Mississippi, Jackson, and associates.

Their analysis used administrative billing data collected by the Kids’ Inpatient Database, maintained by the U.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The project includes a representative national sample of about 3 million pediatric hospital discharges every 3 years. The study used data from 11,483,103 hospitalizations of children and adolescents aged 3-21 years during 2003, 2006, 2009, and 2012, and found an overall hospitalization rate of 0.8% billed for migraine. For patients also hospitalized with a billing code for asthma, the rate jumped to 1.36%, a 120% statistically significant relative increase in migraine hospitalizations after adjustment for baseline demographic differences, the researchers said.

Among the children and adolescents hospitalized with an asthma billing code, the relative rate of also having a billing code for migraine after adjustment was a statistically significant 80% higher in girls, compared with boys, a statistically significant 7% higher in adolescents, compared with children 12 years or younger, and was significantly reduced by a relative 45% rate in nonwhites, compared with whites.

The mechanisms behind these associations are not known, but could involve mast-cell degranulation, autonomic dysfunction, or shared genetic or environmental etiologic factors, the authors said.

Dr. Patel reported no relevant disclosures.