User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

One weird trick to fight burnout

“Here and now is what counts. So, let’s go to work!” –Walter Orthmann, 100 years old

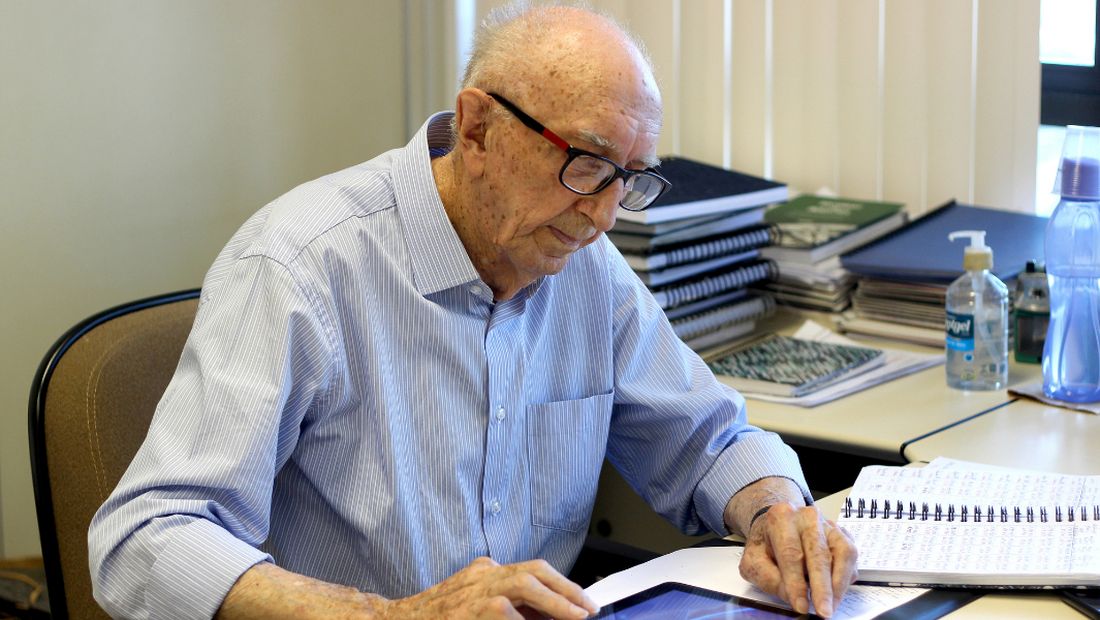

How long before you retire? If you know the answer in exact years, months, and days, you aren’t alone. For many good reasons, we doctors are more likely to be counting down the years until we retire rather than counting up the years since we started working. For me, if I’m to break the Guinness World Record, I have 69 more years, 3 months and 6 days left to go. That would surpass the current achievement for the longest career at one company, Mr. Walter Orthmann, who has been sitting at the same desk for 84 years. At 100 years old, Mr. Orthmann still shows up every Monday morning, as bright eyed and bushy tailed as a young squirrel. I’ll be 119 when I break his streak, which would also put me past Anthony Mancinelli, a New York barber who at 107 years of age was still brushing off his chair for the next customer. Unbelievable, I know! I wonder, what’s the one weird trick these guys are doing that keeps them going?

Of course, the job itself matters. Some jobs, like being a police officer, aren’t suitable for old people. Or are they? Officer L.C. “Buckshot” Smith was still keeping streets safe from his patrol car at 91 years old. After a bit of searching, I found pretty much any job you can think of has a very long-lasting Energizer Bunny story: A female surgeon who was operating at 90 years old, a 100-year-old rheumatologist who was still teaching at University of California, San Francisco, and a 105-year-old Japanese physician who was still seeing patients. There are plenty of geriatric lawyers, nurses, land surveyors, accountants, judges, you name it. So it seems it’s not the work, but the worker that matters. Why do some older workers recharge daily and carry on while many younger ones say the daily grind is burning them out? What makes the Greatest Generation so great?

We all know colleagues who hung up their white coats early. In my medical group, it’s often financially feasible to retire at 58 and many have chosen that option. Yet, we have loads of Partner Emeritus docs in their 70’s who still log on to EPIC and pitch in everyday.

“So, how do you keep going?” I asked my 105-year-old patient who still walks and manages his affairs. “Just stay healthy,” he advised. A circular argument, yet he’s right. You must both be lucky and also choose to be active mentally and physically. Mr. Mancinelli, who was barbering full time at 107 years old, had no aches and pains and all his teeth. He pruned his own bushes. The data are crystal clear that physical activity adds not only years of life, but also improves cognitive capabilities during those years.

As for beating burnout, it seems the one trick that these ultraworkers do is to focus only on the present. Mr. Orthmann’s pithy advice as quoted by NPR is, “You need to get busy with the present, not the past or the future.” These centenarian employees also frame their work not as stressful but rather as their daily series of problems to be solved.

When I asked my super-geriatric patient how he sleeps so well, he said, “I never worry when I get into bed, I just shut my eyes and sleep. I’ll think about tomorrow when I wake up.” Now if I can do that about 25,000 more times, I’ll have the record.

Dr. Jeff Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

“Here and now is what counts. So, let’s go to work!” –Walter Orthmann, 100 years old

How long before you retire? If you know the answer in exact years, months, and days, you aren’t alone. For many good reasons, we doctors are more likely to be counting down the years until we retire rather than counting up the years since we started working. For me, if I’m to break the Guinness World Record, I have 69 more years, 3 months and 6 days left to go. That would surpass the current achievement for the longest career at one company, Mr. Walter Orthmann, who has been sitting at the same desk for 84 years. At 100 years old, Mr. Orthmann still shows up every Monday morning, as bright eyed and bushy tailed as a young squirrel. I’ll be 119 when I break his streak, which would also put me past Anthony Mancinelli, a New York barber who at 107 years of age was still brushing off his chair for the next customer. Unbelievable, I know! I wonder, what’s the one weird trick these guys are doing that keeps them going?

Of course, the job itself matters. Some jobs, like being a police officer, aren’t suitable for old people. Or are they? Officer L.C. “Buckshot” Smith was still keeping streets safe from his patrol car at 91 years old. After a bit of searching, I found pretty much any job you can think of has a very long-lasting Energizer Bunny story: A female surgeon who was operating at 90 years old, a 100-year-old rheumatologist who was still teaching at University of California, San Francisco, and a 105-year-old Japanese physician who was still seeing patients. There are plenty of geriatric lawyers, nurses, land surveyors, accountants, judges, you name it. So it seems it’s not the work, but the worker that matters. Why do some older workers recharge daily and carry on while many younger ones say the daily grind is burning them out? What makes the Greatest Generation so great?

We all know colleagues who hung up their white coats early. In my medical group, it’s often financially feasible to retire at 58 and many have chosen that option. Yet, we have loads of Partner Emeritus docs in their 70’s who still log on to EPIC and pitch in everyday.

“So, how do you keep going?” I asked my 105-year-old patient who still walks and manages his affairs. “Just stay healthy,” he advised. A circular argument, yet he’s right. You must both be lucky and also choose to be active mentally and physically. Mr. Mancinelli, who was barbering full time at 107 years old, had no aches and pains and all his teeth. He pruned his own bushes. The data are crystal clear that physical activity adds not only years of life, but also improves cognitive capabilities during those years.

As for beating burnout, it seems the one trick that these ultraworkers do is to focus only on the present. Mr. Orthmann’s pithy advice as quoted by NPR is, “You need to get busy with the present, not the past or the future.” These centenarian employees also frame their work not as stressful but rather as their daily series of problems to be solved.

When I asked my super-geriatric patient how he sleeps so well, he said, “I never worry when I get into bed, I just shut my eyes and sleep. I’ll think about tomorrow when I wake up.” Now if I can do that about 25,000 more times, I’ll have the record.

Dr. Jeff Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

“Here and now is what counts. So, let’s go to work!” –Walter Orthmann, 100 years old

How long before you retire? If you know the answer in exact years, months, and days, you aren’t alone. For many good reasons, we doctors are more likely to be counting down the years until we retire rather than counting up the years since we started working. For me, if I’m to break the Guinness World Record, I have 69 more years, 3 months and 6 days left to go. That would surpass the current achievement for the longest career at one company, Mr. Walter Orthmann, who has been sitting at the same desk for 84 years. At 100 years old, Mr. Orthmann still shows up every Monday morning, as bright eyed and bushy tailed as a young squirrel. I’ll be 119 when I break his streak, which would also put me past Anthony Mancinelli, a New York barber who at 107 years of age was still brushing off his chair for the next customer. Unbelievable, I know! I wonder, what’s the one weird trick these guys are doing that keeps them going?

Of course, the job itself matters. Some jobs, like being a police officer, aren’t suitable for old people. Or are they? Officer L.C. “Buckshot” Smith was still keeping streets safe from his patrol car at 91 years old. After a bit of searching, I found pretty much any job you can think of has a very long-lasting Energizer Bunny story: A female surgeon who was operating at 90 years old, a 100-year-old rheumatologist who was still teaching at University of California, San Francisco, and a 105-year-old Japanese physician who was still seeing patients. There are plenty of geriatric lawyers, nurses, land surveyors, accountants, judges, you name it. So it seems it’s not the work, but the worker that matters. Why do some older workers recharge daily and carry on while many younger ones say the daily grind is burning them out? What makes the Greatest Generation so great?

We all know colleagues who hung up their white coats early. In my medical group, it’s often financially feasible to retire at 58 and many have chosen that option. Yet, we have loads of Partner Emeritus docs in their 70’s who still log on to EPIC and pitch in everyday.

“So, how do you keep going?” I asked my 105-year-old patient who still walks and manages his affairs. “Just stay healthy,” he advised. A circular argument, yet he’s right. You must both be lucky and also choose to be active mentally and physically. Mr. Mancinelli, who was barbering full time at 107 years old, had no aches and pains and all his teeth. He pruned his own bushes. The data are crystal clear that physical activity adds not only years of life, but also improves cognitive capabilities during those years.

As for beating burnout, it seems the one trick that these ultraworkers do is to focus only on the present. Mr. Orthmann’s pithy advice as quoted by NPR is, “You need to get busy with the present, not the past or the future.” These centenarian employees also frame their work not as stressful but rather as their daily series of problems to be solved.

When I asked my super-geriatric patient how he sleeps so well, he said, “I never worry when I get into bed, I just shut my eyes and sleep. I’ll think about tomorrow when I wake up.” Now if I can do that about 25,000 more times, I’ll have the record.

Dr. Jeff Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com

Lost keys, missed appointments: The struggle of treating executive dysfunction

Maybe you know some of these patients: They may come late or not show up at all. They may have little to say and minimize their difficulties, often because they are ashamed of how much effort it takes to meet ordinary obligations. They may struggle to complete assignments, fail classes, or lose jobs. And being in the right place at the right time can feel monumental to them: They forget appointments, double book themselves, or sometimes sleep through important events.

It’s not just appointments. They lose their keys and valuables, forget to pay bills, and may not answer calls, texts, or emails. Their voicemail may be full and people are often frustrated with them. These are all characteristics of executive dysfunction, which together can make the routine responsibilities of life very difficult.

Treatments include stimulants, and because of their potential for abuse, these medications are more strictly regulated when it comes to prescribing. The FDA does not allow them to be phoned into a pharmacy or refills to be added to prescriptions. Patients must wait until right before they are due to run out to get the next prescription, and this can present a problem if the patient travels or takes long vacations.

And although it is not the patient’s fault that stimulants can’t be ordered with refills, this adds to the burden of treating patients who take them. It’s hard to imagine that these restrictions on stimulants and opiates (but not on benzodiazepines) do much to deter abuse or diversion.

I trained at a time when ADD and ADHD were disorders of childhood, and as an adult psychiatrist, I was not exposed to patients on these medications. Occasionally, a stimulant was prescribed in a low dose to help activate a very depressed patient, but it was thought that children outgrow issues of attention and focus, and I have never felt fully confident in the more nuanced use of these medications with adults. Most of the patients I now treat with ADD have come to me on stable doses of the medications or at least with a history that directs care.

With others, the tip-off to look for the disorder is their disorganization in the absence of a substance use or active mood disorder. Medications help, sometimes remarkably, yet patients still struggle with organization and planning, and sometimes I find myself frustrated when patients forget their appointments or the issues around prescribing stimulants become time-consuming.

David W. Goodman, MD, director of the Adult Attention Deficit Center of Maryland, Lutherville, currently treats hundreds of patients with ADD and has written and spoken extensively about treating this disorder in adults.

“There are three things that make it difficult to manage patients with ADD,” Dr. Goodman noted, referring specifically to administrative issues. “You can’t write for refills, but with e-prescribing you can write a sequence of prescriptions with ‘fill-after’ dates. Or some patients are able to get a 90-day supply from mail-order pharmacies. Still, it’s a hassle if the patient moves around, as college students often do, and there are inventory shortages when some pharmacies can’t get the medications.”

“The second issue,” he adds, “is that it’s the nature of this disorder that patients struggle with organizational issues. Yelling at someone with ADD to pay attention is like yelling at a blind person not to run into furniture when they are in a new room. They go through life with people being impatient that they can’t do the things an ordinary person can do easily.”

Finally, Dr. Goodman noted that the clinicians who treat patients with ADD may have counter-transference issues.

“You have to understand that this is a disability and be sympathetic to it. They often have comorbid disorders, including personality disorders, and this can all bleed over to cause frustrations in their care. Psychiatrists who treat patients with ADD need to know they can deal with them compassionately.”

“I am occasionally contacted by patients who already have an ADHD diagnosis and are on stimulants, and who seem like they just want to get their prescriptions filled and aren’t interested in working on their issues,” says Douglas Beech, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Worthington, Ohio. “The doctor in this situation can feel like they are functioning as a sort of drug dealer. There are logistical matters that are structurally inherent in trying to assist these patients, from both a regulatory perspective and from a functional perspective. Dr. Beech feels that it’s helpful to acknowledge these issues when seeing patients with ADHD, so that he is prepared when problems do arise.

“It can almost feel cruel to charge a patient for a “no-show,” when difficulty keeping appointments may be a symptom of their illness, Dr. Beech adds. But he does believe it’s important to apply any fee policy equitably to all patients. “I don’t apply the ‘missed appointment’ policy differently to a person with an ADHD diagnosis versus any other diagnosis.” Though for their first missed appointment, he does give patients a “mulligan.”

“I don’t charge, but it puts both patient and doctor on notice,” he says.

And when his patients do miss an appointment, he offers to send a reminder for the next time, which is he says is effective. “With electronic messaging, this is a quick and easy way to prevent missed appointments and the complications that arise with prescriptions and rescheduling,” says Dr. Beech.

Dr. Goodman speaks about manging a large caseload of patients, many of whom have organizational issues.

“I have a full-time office manager who handles a lot of the logistics of scheduling and prescribing. Patients are sent multiple reminders, and I charge a nominal administrative fee if prescriptions need to be sent outside of appointments. This is not to make money, but to encourage patients to consider the administrative time.”

“I charge for appointments that are not canceled 48 hours in advance, and for patients who have missed appointments, a credit card is kept on file,” he says.

In a practice similar to Dr. Beech, Dr. Goodman notes that he shows some flexibility for new patients when they miss an appointment the first time. “By the second time, they know this is the policy. Having ADHD can be financially costly.”

He notes that about 10% of his patients, roughly one a day, cancel late or don’t show up for scheduled appointments: “We keep a waitlist, and if someone cancels before the appointment, we can often fill the time with another patient in need on our waitlist.”

Dr. Goodman noted repeatedly that the clinician needs to be able to empathize with the patient’s condition and how they suffer. “This is not something people choose to have. The trap is that people think that if you’re successful you can’t have ADHD, and that’s not true. Often people with this condition work harder, are brighter, and find ways to compensate.”

If a practice is set up to accommodate the needs of patients with attention and organizational issues, treating them can be very gratifying. In settings without administrative support, the psychiatrist needs to stay cognizant of this invisible disability and the frustration that may come with this disorder, not just for the patient, but also for the family, friends, and employers, and even for the psychiatrist.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maybe you know some of these patients: They may come late or not show up at all. They may have little to say and minimize their difficulties, often because they are ashamed of how much effort it takes to meet ordinary obligations. They may struggle to complete assignments, fail classes, or lose jobs. And being in the right place at the right time can feel monumental to them: They forget appointments, double book themselves, or sometimes sleep through important events.

It’s not just appointments. They lose their keys and valuables, forget to pay bills, and may not answer calls, texts, or emails. Their voicemail may be full and people are often frustrated with them. These are all characteristics of executive dysfunction, which together can make the routine responsibilities of life very difficult.

Treatments include stimulants, and because of their potential for abuse, these medications are more strictly regulated when it comes to prescribing. The FDA does not allow them to be phoned into a pharmacy or refills to be added to prescriptions. Patients must wait until right before they are due to run out to get the next prescription, and this can present a problem if the patient travels or takes long vacations.

And although it is not the patient’s fault that stimulants can’t be ordered with refills, this adds to the burden of treating patients who take them. It’s hard to imagine that these restrictions on stimulants and opiates (but not on benzodiazepines) do much to deter abuse or diversion.

I trained at a time when ADD and ADHD were disorders of childhood, and as an adult psychiatrist, I was not exposed to patients on these medications. Occasionally, a stimulant was prescribed in a low dose to help activate a very depressed patient, but it was thought that children outgrow issues of attention and focus, and I have never felt fully confident in the more nuanced use of these medications with adults. Most of the patients I now treat with ADD have come to me on stable doses of the medications or at least with a history that directs care.

With others, the tip-off to look for the disorder is their disorganization in the absence of a substance use or active mood disorder. Medications help, sometimes remarkably, yet patients still struggle with organization and planning, and sometimes I find myself frustrated when patients forget their appointments or the issues around prescribing stimulants become time-consuming.

David W. Goodman, MD, director of the Adult Attention Deficit Center of Maryland, Lutherville, currently treats hundreds of patients with ADD and has written and spoken extensively about treating this disorder in adults.

“There are three things that make it difficult to manage patients with ADD,” Dr. Goodman noted, referring specifically to administrative issues. “You can’t write for refills, but with e-prescribing you can write a sequence of prescriptions with ‘fill-after’ dates. Or some patients are able to get a 90-day supply from mail-order pharmacies. Still, it’s a hassle if the patient moves around, as college students often do, and there are inventory shortages when some pharmacies can’t get the medications.”

“The second issue,” he adds, “is that it’s the nature of this disorder that patients struggle with organizational issues. Yelling at someone with ADD to pay attention is like yelling at a blind person not to run into furniture when they are in a new room. They go through life with people being impatient that they can’t do the things an ordinary person can do easily.”

Finally, Dr. Goodman noted that the clinicians who treat patients with ADD may have counter-transference issues.

“You have to understand that this is a disability and be sympathetic to it. They often have comorbid disorders, including personality disorders, and this can all bleed over to cause frustrations in their care. Psychiatrists who treat patients with ADD need to know they can deal with them compassionately.”

“I am occasionally contacted by patients who already have an ADHD diagnosis and are on stimulants, and who seem like they just want to get their prescriptions filled and aren’t interested in working on their issues,” says Douglas Beech, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Worthington, Ohio. “The doctor in this situation can feel like they are functioning as a sort of drug dealer. There are logistical matters that are structurally inherent in trying to assist these patients, from both a regulatory perspective and from a functional perspective. Dr. Beech feels that it’s helpful to acknowledge these issues when seeing patients with ADHD, so that he is prepared when problems do arise.

“It can almost feel cruel to charge a patient for a “no-show,” when difficulty keeping appointments may be a symptom of their illness, Dr. Beech adds. But he does believe it’s important to apply any fee policy equitably to all patients. “I don’t apply the ‘missed appointment’ policy differently to a person with an ADHD diagnosis versus any other diagnosis.” Though for their first missed appointment, he does give patients a “mulligan.”

“I don’t charge, but it puts both patient and doctor on notice,” he says.

And when his patients do miss an appointment, he offers to send a reminder for the next time, which is he says is effective. “With electronic messaging, this is a quick and easy way to prevent missed appointments and the complications that arise with prescriptions and rescheduling,” says Dr. Beech.

Dr. Goodman speaks about manging a large caseload of patients, many of whom have organizational issues.

“I have a full-time office manager who handles a lot of the logistics of scheduling and prescribing. Patients are sent multiple reminders, and I charge a nominal administrative fee if prescriptions need to be sent outside of appointments. This is not to make money, but to encourage patients to consider the administrative time.”

“I charge for appointments that are not canceled 48 hours in advance, and for patients who have missed appointments, a credit card is kept on file,” he says.

In a practice similar to Dr. Beech, Dr. Goodman notes that he shows some flexibility for new patients when they miss an appointment the first time. “By the second time, they know this is the policy. Having ADHD can be financially costly.”

He notes that about 10% of his patients, roughly one a day, cancel late or don’t show up for scheduled appointments: “We keep a waitlist, and if someone cancels before the appointment, we can often fill the time with another patient in need on our waitlist.”

Dr. Goodman noted repeatedly that the clinician needs to be able to empathize with the patient’s condition and how they suffer. “This is not something people choose to have. The trap is that people think that if you’re successful you can’t have ADHD, and that’s not true. Often people with this condition work harder, are brighter, and find ways to compensate.”

If a practice is set up to accommodate the needs of patients with attention and organizational issues, treating them can be very gratifying. In settings without administrative support, the psychiatrist needs to stay cognizant of this invisible disability and the frustration that may come with this disorder, not just for the patient, but also for the family, friends, and employers, and even for the psychiatrist.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maybe you know some of these patients: They may come late or not show up at all. They may have little to say and minimize their difficulties, often because they are ashamed of how much effort it takes to meet ordinary obligations. They may struggle to complete assignments, fail classes, or lose jobs. And being in the right place at the right time can feel monumental to them: They forget appointments, double book themselves, or sometimes sleep through important events.

It’s not just appointments. They lose their keys and valuables, forget to pay bills, and may not answer calls, texts, or emails. Their voicemail may be full and people are often frustrated with them. These are all characteristics of executive dysfunction, which together can make the routine responsibilities of life very difficult.

Treatments include stimulants, and because of their potential for abuse, these medications are more strictly regulated when it comes to prescribing. The FDA does not allow them to be phoned into a pharmacy or refills to be added to prescriptions. Patients must wait until right before they are due to run out to get the next prescription, and this can present a problem if the patient travels or takes long vacations.

And although it is not the patient’s fault that stimulants can’t be ordered with refills, this adds to the burden of treating patients who take them. It’s hard to imagine that these restrictions on stimulants and opiates (but not on benzodiazepines) do much to deter abuse or diversion.

I trained at a time when ADD and ADHD were disorders of childhood, and as an adult psychiatrist, I was not exposed to patients on these medications. Occasionally, a stimulant was prescribed in a low dose to help activate a very depressed patient, but it was thought that children outgrow issues of attention and focus, and I have never felt fully confident in the more nuanced use of these medications with adults. Most of the patients I now treat with ADD have come to me on stable doses of the medications or at least with a history that directs care.

With others, the tip-off to look for the disorder is their disorganization in the absence of a substance use or active mood disorder. Medications help, sometimes remarkably, yet patients still struggle with organization and planning, and sometimes I find myself frustrated when patients forget their appointments or the issues around prescribing stimulants become time-consuming.

David W. Goodman, MD, director of the Adult Attention Deficit Center of Maryland, Lutherville, currently treats hundreds of patients with ADD and has written and spoken extensively about treating this disorder in adults.

“There are three things that make it difficult to manage patients with ADD,” Dr. Goodman noted, referring specifically to administrative issues. “You can’t write for refills, but with e-prescribing you can write a sequence of prescriptions with ‘fill-after’ dates. Or some patients are able to get a 90-day supply from mail-order pharmacies. Still, it’s a hassle if the patient moves around, as college students often do, and there are inventory shortages when some pharmacies can’t get the medications.”

“The second issue,” he adds, “is that it’s the nature of this disorder that patients struggle with organizational issues. Yelling at someone with ADD to pay attention is like yelling at a blind person not to run into furniture when they are in a new room. They go through life with people being impatient that they can’t do the things an ordinary person can do easily.”

Finally, Dr. Goodman noted that the clinicians who treat patients with ADD may have counter-transference issues.

“You have to understand that this is a disability and be sympathetic to it. They often have comorbid disorders, including personality disorders, and this can all bleed over to cause frustrations in their care. Psychiatrists who treat patients with ADD need to know they can deal with them compassionately.”

“I am occasionally contacted by patients who already have an ADHD diagnosis and are on stimulants, and who seem like they just want to get their prescriptions filled and aren’t interested in working on their issues,” says Douglas Beech, MD, a psychiatrist in private practice in Worthington, Ohio. “The doctor in this situation can feel like they are functioning as a sort of drug dealer. There are logistical matters that are structurally inherent in trying to assist these patients, from both a regulatory perspective and from a functional perspective. Dr. Beech feels that it’s helpful to acknowledge these issues when seeing patients with ADHD, so that he is prepared when problems do arise.

“It can almost feel cruel to charge a patient for a “no-show,” when difficulty keeping appointments may be a symptom of their illness, Dr. Beech adds. But he does believe it’s important to apply any fee policy equitably to all patients. “I don’t apply the ‘missed appointment’ policy differently to a person with an ADHD diagnosis versus any other diagnosis.” Though for their first missed appointment, he does give patients a “mulligan.”

“I don’t charge, but it puts both patient and doctor on notice,” he says.

And when his patients do miss an appointment, he offers to send a reminder for the next time, which is he says is effective. “With electronic messaging, this is a quick and easy way to prevent missed appointments and the complications that arise with prescriptions and rescheduling,” says Dr. Beech.

Dr. Goodman speaks about manging a large caseload of patients, many of whom have organizational issues.

“I have a full-time office manager who handles a lot of the logistics of scheduling and prescribing. Patients are sent multiple reminders, and I charge a nominal administrative fee if prescriptions need to be sent outside of appointments. This is not to make money, but to encourage patients to consider the administrative time.”

“I charge for appointments that are not canceled 48 hours in advance, and for patients who have missed appointments, a credit card is kept on file,” he says.

In a practice similar to Dr. Beech, Dr. Goodman notes that he shows some flexibility for new patients when they miss an appointment the first time. “By the second time, they know this is the policy. Having ADHD can be financially costly.”

He notes that about 10% of his patients, roughly one a day, cancel late or don’t show up for scheduled appointments: “We keep a waitlist, and if someone cancels before the appointment, we can often fill the time with another patient in need on our waitlist.”

Dr. Goodman noted repeatedly that the clinician needs to be able to empathize with the patient’s condition and how they suffer. “This is not something people choose to have. The trap is that people think that if you’re successful you can’t have ADHD, and that’s not true. Often people with this condition work harder, are brighter, and find ways to compensate.”

If a practice is set up to accommodate the needs of patients with attention and organizational issues, treating them can be very gratifying. In settings without administrative support, the psychiatrist needs to stay cognizant of this invisible disability and the frustration that may come with this disorder, not just for the patient, but also for the family, friends, and employers, and even for the psychiatrist.

Dr. Dinah Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, Baltimore. Dr. Miller has no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Omicron breakthrough cases boost protection, studies say

two preprint studies show.

The University of Washington, Seattle, working with Vir Biotechnology of San Francisco, looked at blood samples of vaccinated people who had breakthrough cases of Delta or Omicron and compared the samples with three other groups: people who caught COVID and were later vaccinated, vaccinated people who were never infected, and people who were infected and never vaccinated.

The vaccinated people who had a breakthrough case of Omicron produced antibodies that helped protect against coronavirus variants, whereas unvaccinated people who caught Omicron didn’t produce as many antibodies, the study showed.

BioNTech, the German biotechnology company, found that people who’d been double and triple vaccinated and then became infected with Omicron had a better B-cell response than people who’d gotten a booster shot but had not been infected.

The University of Washington research team also came up with similar findings about B cells.

The findings don’t mean people should deliberately try to become infected with COVID, said Alexandra Walls, PhD, one of the University of Washington scientists, according to Business Standard.

But the study does indicate “that we are at the point where we may want to consider having a different vaccine to boost people,” said David Veesler, PhD, of the University of Washington team.

“We should think about breakthrough infections as essentially equivalent to another dose of vaccine,” John Wherry, PhD, a professor and director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told Business Standard. Dr. Wherry was not involved in the studies but reviewed the BioNTech study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

two preprint studies show.

The University of Washington, Seattle, working with Vir Biotechnology of San Francisco, looked at blood samples of vaccinated people who had breakthrough cases of Delta or Omicron and compared the samples with three other groups: people who caught COVID and were later vaccinated, vaccinated people who were never infected, and people who were infected and never vaccinated.

The vaccinated people who had a breakthrough case of Omicron produced antibodies that helped protect against coronavirus variants, whereas unvaccinated people who caught Omicron didn’t produce as many antibodies, the study showed.

BioNTech, the German biotechnology company, found that people who’d been double and triple vaccinated and then became infected with Omicron had a better B-cell response than people who’d gotten a booster shot but had not been infected.

The University of Washington research team also came up with similar findings about B cells.

The findings don’t mean people should deliberately try to become infected with COVID, said Alexandra Walls, PhD, one of the University of Washington scientists, according to Business Standard.

But the study does indicate “that we are at the point where we may want to consider having a different vaccine to boost people,” said David Veesler, PhD, of the University of Washington team.

“We should think about breakthrough infections as essentially equivalent to another dose of vaccine,” John Wherry, PhD, a professor and director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told Business Standard. Dr. Wherry was not involved in the studies but reviewed the BioNTech study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

two preprint studies show.

The University of Washington, Seattle, working with Vir Biotechnology of San Francisco, looked at blood samples of vaccinated people who had breakthrough cases of Delta or Omicron and compared the samples with three other groups: people who caught COVID and were later vaccinated, vaccinated people who were never infected, and people who were infected and never vaccinated.

The vaccinated people who had a breakthrough case of Omicron produced antibodies that helped protect against coronavirus variants, whereas unvaccinated people who caught Omicron didn’t produce as many antibodies, the study showed.

BioNTech, the German biotechnology company, found that people who’d been double and triple vaccinated and then became infected with Omicron had a better B-cell response than people who’d gotten a booster shot but had not been infected.

The University of Washington research team also came up with similar findings about B cells.

The findings don’t mean people should deliberately try to become infected with COVID, said Alexandra Walls, PhD, one of the University of Washington scientists, according to Business Standard.

But the study does indicate “that we are at the point where we may want to consider having a different vaccine to boost people,” said David Veesler, PhD, of the University of Washington team.

“We should think about breakthrough infections as essentially equivalent to another dose of vaccine,” John Wherry, PhD, a professor and director of the Institute for Immunology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told Business Standard. Dr. Wherry was not involved in the studies but reviewed the BioNTech study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Student loan forgiveness plans exclude physicians

In the run up to the midterm elections in November, President Biden has warmed to student loan forgiveness. However, before even being proposed,

What was the plan?

During the 2020 election, student loan forgiveness was a hot topic as the COVID epidemic raged. The CARES Act has placed all federal student loans in forbearance, with no payments made and the interest rate set to 0% to prevent further accrual. While this was tremendously useful to 45 million borrowers around the country (including the author), nothing material was done to deal with the loans.

The Biden Administration’s approach at that time was multi-tiered and chaotic. Plans were put forward that either expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or capped it. Plans were put forward that either extended free undergraduate or severely limited it through Pell Grants. Unfortunately, that duality continues today, with current plans not having a clear goal or a target group of beneficiaries.

Necessary CARES Act extensions

The Biden Administration has attempted repeatedly to turn the student loan apparatus back on, restarting payments en masse. However, each time, they are beset by challenges, ranging from repeat COVID spikes to servicer withdrawals or macroeconomic indicators of a recession.

At each step, the administration has had little choice but to extend the CARES Act forbearance, lest they suffer retribution for hastily resuming payments for 45 million borrowers without the apparatus to do so. Two years ago, the major federal servicers laid off hundreds, if not thousands, of staffers responsible for payment processing, accounting, customer care, and taxation. Hiring, training, and staffing these positions is nontrivial.

The administration has been out of step with servicers such that three of the largest have chosen not to renew their contracts: Navient, MyFedLoan, and Granite State Management and Resources. This has left 15 million borrowers in the lurch, not knowing who their servicer is – and, even worse, losing track of qualifying payments toward programs like PSLF.

Avenues of forgiveness

There are two major pathways to forgiveness. It is widely believed that the executive branch has the authority to broadly forgive student loans under executive order and managed through the U.S. Department of Education.

The alternative is through congressional action, voting on forgiveness as an economic stimulus plan. There is little appetite in Congress for forgiveness, and prominent congresspeople like Senator Warren and Senator Schumer have both pushed the executive branch for forgiveness in recognition of this.

What has been proposed?

First, it’s important to state that as headline-grabbing as it is to see that $50,000 of forgiveness has been proposed, the reality is that President Biden has repeatedly stated that he will not be in favor of that level of forgiveness. Instead, the number most commonly being discussed is $10,000. This would represent an unprecedented amount of support, alleviating 35% of borrowers of all student debt.

The impact of proposed forgiveness plans for physicians

For the medical community, sadly, this doesn’t represent a significant amount of forgiveness. At graduation, the average MD has $203,000 in debt, and the average DO has $258,000 in debt. These numbers grow during residency for years before any meaningful payments are made.

Further weakening forgiveness plans for physicians has been two caps proposed by the administration in recent days. The first is an income cap of $125,000. While this would maintain forgiveness for nearly all residents and fellows, this would exclude nearly every practicing physician. The alternative to an income cap is specific exclusion of certain careers seen to be high-earning: doctors and lawyers.

The bottom line

Physicians are unlikely to be included in any forgiveness plans being proposed recently by the Biden Administration. If they are considered, it will be for exclusion from any forgiveness offered.

For physicians no longer eligible for PSLF, this exclusion needs to be considered in managing the student loan debt associated with becoming a doctor.

Dr. Palmer is a part-time instructor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and staff physician, department of medical critical care, Boston Children’s Hospital. He disclosed that he serves as director for Panacea Financial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the run up to the midterm elections in November, President Biden has warmed to student loan forgiveness. However, before even being proposed,

What was the plan?

During the 2020 election, student loan forgiveness was a hot topic as the COVID epidemic raged. The CARES Act has placed all federal student loans in forbearance, with no payments made and the interest rate set to 0% to prevent further accrual. While this was tremendously useful to 45 million borrowers around the country (including the author), nothing material was done to deal with the loans.

The Biden Administration’s approach at that time was multi-tiered and chaotic. Plans were put forward that either expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or capped it. Plans were put forward that either extended free undergraduate or severely limited it through Pell Grants. Unfortunately, that duality continues today, with current plans not having a clear goal or a target group of beneficiaries.

Necessary CARES Act extensions

The Biden Administration has attempted repeatedly to turn the student loan apparatus back on, restarting payments en masse. However, each time, they are beset by challenges, ranging from repeat COVID spikes to servicer withdrawals or macroeconomic indicators of a recession.

At each step, the administration has had little choice but to extend the CARES Act forbearance, lest they suffer retribution for hastily resuming payments for 45 million borrowers without the apparatus to do so. Two years ago, the major federal servicers laid off hundreds, if not thousands, of staffers responsible for payment processing, accounting, customer care, and taxation. Hiring, training, and staffing these positions is nontrivial.

The administration has been out of step with servicers such that three of the largest have chosen not to renew their contracts: Navient, MyFedLoan, and Granite State Management and Resources. This has left 15 million borrowers in the lurch, not knowing who their servicer is – and, even worse, losing track of qualifying payments toward programs like PSLF.

Avenues of forgiveness

There are two major pathways to forgiveness. It is widely believed that the executive branch has the authority to broadly forgive student loans under executive order and managed through the U.S. Department of Education.

The alternative is through congressional action, voting on forgiveness as an economic stimulus plan. There is little appetite in Congress for forgiveness, and prominent congresspeople like Senator Warren and Senator Schumer have both pushed the executive branch for forgiveness in recognition of this.

What has been proposed?

First, it’s important to state that as headline-grabbing as it is to see that $50,000 of forgiveness has been proposed, the reality is that President Biden has repeatedly stated that he will not be in favor of that level of forgiveness. Instead, the number most commonly being discussed is $10,000. This would represent an unprecedented amount of support, alleviating 35% of borrowers of all student debt.

The impact of proposed forgiveness plans for physicians

For the medical community, sadly, this doesn’t represent a significant amount of forgiveness. At graduation, the average MD has $203,000 in debt, and the average DO has $258,000 in debt. These numbers grow during residency for years before any meaningful payments are made.

Further weakening forgiveness plans for physicians has been two caps proposed by the administration in recent days. The first is an income cap of $125,000. While this would maintain forgiveness for nearly all residents and fellows, this would exclude nearly every practicing physician. The alternative to an income cap is specific exclusion of certain careers seen to be high-earning: doctors and lawyers.

The bottom line

Physicians are unlikely to be included in any forgiveness plans being proposed recently by the Biden Administration. If they are considered, it will be for exclusion from any forgiveness offered.

For physicians no longer eligible for PSLF, this exclusion needs to be considered in managing the student loan debt associated with becoming a doctor.

Dr. Palmer is a part-time instructor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and staff physician, department of medical critical care, Boston Children’s Hospital. He disclosed that he serves as director for Panacea Financial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the run up to the midterm elections in November, President Biden has warmed to student loan forgiveness. However, before even being proposed,

What was the plan?

During the 2020 election, student loan forgiveness was a hot topic as the COVID epidemic raged. The CARES Act has placed all federal student loans in forbearance, with no payments made and the interest rate set to 0% to prevent further accrual. While this was tremendously useful to 45 million borrowers around the country (including the author), nothing material was done to deal with the loans.

The Biden Administration’s approach at that time was multi-tiered and chaotic. Plans were put forward that either expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) or capped it. Plans were put forward that either extended free undergraduate or severely limited it through Pell Grants. Unfortunately, that duality continues today, with current plans not having a clear goal or a target group of beneficiaries.

Necessary CARES Act extensions

The Biden Administration has attempted repeatedly to turn the student loan apparatus back on, restarting payments en masse. However, each time, they are beset by challenges, ranging from repeat COVID spikes to servicer withdrawals or macroeconomic indicators of a recession.

At each step, the administration has had little choice but to extend the CARES Act forbearance, lest they suffer retribution for hastily resuming payments for 45 million borrowers without the apparatus to do so. Two years ago, the major federal servicers laid off hundreds, if not thousands, of staffers responsible for payment processing, accounting, customer care, and taxation. Hiring, training, and staffing these positions is nontrivial.

The administration has been out of step with servicers such that three of the largest have chosen not to renew their contracts: Navient, MyFedLoan, and Granite State Management and Resources. This has left 15 million borrowers in the lurch, not knowing who their servicer is – and, even worse, losing track of qualifying payments toward programs like PSLF.

Avenues of forgiveness

There are two major pathways to forgiveness. It is widely believed that the executive branch has the authority to broadly forgive student loans under executive order and managed through the U.S. Department of Education.

The alternative is through congressional action, voting on forgiveness as an economic stimulus plan. There is little appetite in Congress for forgiveness, and prominent congresspeople like Senator Warren and Senator Schumer have both pushed the executive branch for forgiveness in recognition of this.

What has been proposed?

First, it’s important to state that as headline-grabbing as it is to see that $50,000 of forgiveness has been proposed, the reality is that President Biden has repeatedly stated that he will not be in favor of that level of forgiveness. Instead, the number most commonly being discussed is $10,000. This would represent an unprecedented amount of support, alleviating 35% of borrowers of all student debt.

The impact of proposed forgiveness plans for physicians

For the medical community, sadly, this doesn’t represent a significant amount of forgiveness. At graduation, the average MD has $203,000 in debt, and the average DO has $258,000 in debt. These numbers grow during residency for years before any meaningful payments are made.

Further weakening forgiveness plans for physicians has been two caps proposed by the administration in recent days. The first is an income cap of $125,000. While this would maintain forgiveness for nearly all residents and fellows, this would exclude nearly every practicing physician. The alternative to an income cap is specific exclusion of certain careers seen to be high-earning: doctors and lawyers.

The bottom line

Physicians are unlikely to be included in any forgiveness plans being proposed recently by the Biden Administration. If they are considered, it will be for exclusion from any forgiveness offered.

For physicians no longer eligible for PSLF, this exclusion needs to be considered in managing the student loan debt associated with becoming a doctor.

Dr. Palmer is a part-time instructor, department of pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and staff physician, department of medical critical care, Boston Children’s Hospital. He disclosed that he serves as director for Panacea Financial.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why do clinical trials still underrepresent minority groups?

It’s no secret that, for decades, the participants in clinical trials for new drugs and medical devices haven’t accurately represented the diverse groups of patients the drugs and devices were designed for.

In a recently published draft guidance, the Food and Drug Administration recommended that companies in charge of running these trials should submit a proposal to the agency that would address how they plan to enroll more “clinically relevant populations” and historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

It’s an issue that the U.S. has been trying to fix for years. In 1993, the NIH Revitalization Act was passed into law. It mandated the appropriate inclusion of women and racial minorities in all National Institutes of Health–funded research.

Since then, the FDA has put out plans that encourage trial sponsors to recruit more diverse enrollees, offering strategies and best practices rather than establishing requirements or quotas that companies would be forced to meet. Despite its efforts to encourage inclusion, people of color continue to be largely underrepresented in clinical trials.

Experts aren’t just calling for trial cohorts to reflect U.S. census data. Rather, the demographics of participants should match those of the diagnosis being studied. An analysis of 24 clinical trials of cardiovascular drugs, for example, found that Black Americans made up 2.9% of trial participants, compared with 83.1% for White people. Given that cardiovascular diseases affect Black Americans at almost the same rate as Whites (23.5% and 23.7%, respectively) – and keeping in mind that Black Americans make up 13.4% of the population and White people represent 76.3% – the degree of underrepresentation is glaring.

One commonly cited reason for this lack of representation is that people of color, especially Black Americans, have lingering feelings of mistrust toward the medical field. The U.S.-run Tuskegee study – during which researchers documented the natural progression of syphilis in hundreds of Black men who were kept from life-saving treatment – is, justifiably, often named as a notable source of that suspicion.

But blaming the disproportionately low numbers of Black participants in clinical trials on medical mistrust is an easy answer to a much more complicated issue, said cardiologist Clyde Yancy, MD, who also serves as the vice dean for diversity and inclusion at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

“We need to not put the onus on the back of the patient cohort, and say they are the problem,” Dr. Yancy said, adding that many trials add financial barriers and don’t provide proper transportation for participants who may live farther away.

The diversity of the study team itself – the institutions, researchers, and recruiters – also contributes to a lack of diversity in the participant pool. When considering all of these factors, “you begin to understand the complexity and the multidimensionality of why we have underrepresentation,” said Dr. Yancy. “So I would not promulgate the notion that this is simply because patients don’t trust the system.”

Soumya Niranjan, PhD, worked as a study coordinator at the Tulane Cancer Center in New Orleans, La., where she recruited patients for a prostate cancer study. After researching the impact of clinicians’ biases on the recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities in oncology trials, she found that some recruiters view patients of color as less promising participants.

“Who ends up being approached for a clinical trial is based on a preset rubric that one has in mind about a patient who may be eligible for a cancer study,” said Dr. Niranjan. “There is a characterization of, ‘we want to make sure this patient is compliant, that they will be a good historian and seem responsible.’ ... Our study showed that it kind of fell along racial lines.”

In her study, published in the journal Cancer in 2020, Dr. Niranjan wrote that researchers sometimes “perceived racial minority groups to have low knowledge of cancer clinical trials. This was considered to be a hindrance while explaining cancer clinical trials in the face of limited provider time during a clinical encounter.”

Some researchers believed minority participants, especially Black women, would be less likely to file study protocols. Others said people of color are more likely to be selfish.

She quoted one research investigator as saying Black people are less knowledgeable.

“African Americans I think have less knowledge,” the unnamed researcher said. “We take a little bit more time to explain to African American [sic]. I think ... they have more questions because we know they are not more knowledgeable so I think it takes time. They have a lot of questions.”

Progress over the years

The FDA’s recent draft builds upon a guidance from 2016, which already recommended that trial teams submit an inclusion plan to the agency at the earliest phase of development. While the recent announcement is another step in the right direction, it may not be substantial enough.

“There’s always an enrollment plan,” Dr. Niranjan said. “But those enrollment plans are not enforced. So if it’s not enforced, what does that look like?”

In an emailed statement to this news organization, Lola Fashoyin-Aje, MD, the deputy director of the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence’s division to expand diversity, emphasized that the draft guidance does not require anything, but that the agency “expect[s] sponsors will follow FDA’s recommendations as described in the draft guidance.”

Without requirements, it’s up to the sponsor to make the effort to enroll people with varied racial and ethnic backgrounds. During the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, Moderna announced that the company would slow the trial’s enrollment to ensure minority groups were properly represented.

Not every sponsor is as motivated to make this a concerted effort, and some simply don’t have the funds to allocate to strengthening the enrollment process.

“There’s so much red tape and paperwork to get the funding for a clinical trial,” said Julie Silver, MD, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies workforce diversity and inclusion. “Even when people are equitably included, the amount of funding they have to do the trial might not be enough to do an analysis that shows potential differences.”

Whether the FDA will enforce enrollment plans in the future remains an open question; however, Dr. Yancy said the most effective way to do this would be through incentives, rather than penalties.

According to Dr. Fashoyin-Aje, the FDA and sponsors “will learn from these submissions and over time, whether and how these diversity plans lead to meaningful changes in clinical trial representation will need to be assessed, including whether additional steps need to be taken.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s no secret that, for decades, the participants in clinical trials for new drugs and medical devices haven’t accurately represented the diverse groups of patients the drugs and devices were designed for.

In a recently published draft guidance, the Food and Drug Administration recommended that companies in charge of running these trials should submit a proposal to the agency that would address how they plan to enroll more “clinically relevant populations” and historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

It’s an issue that the U.S. has been trying to fix for years. In 1993, the NIH Revitalization Act was passed into law. It mandated the appropriate inclusion of women and racial minorities in all National Institutes of Health–funded research.

Since then, the FDA has put out plans that encourage trial sponsors to recruit more diverse enrollees, offering strategies and best practices rather than establishing requirements or quotas that companies would be forced to meet. Despite its efforts to encourage inclusion, people of color continue to be largely underrepresented in clinical trials.

Experts aren’t just calling for trial cohorts to reflect U.S. census data. Rather, the demographics of participants should match those of the diagnosis being studied. An analysis of 24 clinical trials of cardiovascular drugs, for example, found that Black Americans made up 2.9% of trial participants, compared with 83.1% for White people. Given that cardiovascular diseases affect Black Americans at almost the same rate as Whites (23.5% and 23.7%, respectively) – and keeping in mind that Black Americans make up 13.4% of the population and White people represent 76.3% – the degree of underrepresentation is glaring.

One commonly cited reason for this lack of representation is that people of color, especially Black Americans, have lingering feelings of mistrust toward the medical field. The U.S.-run Tuskegee study – during which researchers documented the natural progression of syphilis in hundreds of Black men who were kept from life-saving treatment – is, justifiably, often named as a notable source of that suspicion.

But blaming the disproportionately low numbers of Black participants in clinical trials on medical mistrust is an easy answer to a much more complicated issue, said cardiologist Clyde Yancy, MD, who also serves as the vice dean for diversity and inclusion at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

“We need to not put the onus on the back of the patient cohort, and say they are the problem,” Dr. Yancy said, adding that many trials add financial barriers and don’t provide proper transportation for participants who may live farther away.

The diversity of the study team itself – the institutions, researchers, and recruiters – also contributes to a lack of diversity in the participant pool. When considering all of these factors, “you begin to understand the complexity and the multidimensionality of why we have underrepresentation,” said Dr. Yancy. “So I would not promulgate the notion that this is simply because patients don’t trust the system.”

Soumya Niranjan, PhD, worked as a study coordinator at the Tulane Cancer Center in New Orleans, La., where she recruited patients for a prostate cancer study. After researching the impact of clinicians’ biases on the recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities in oncology trials, she found that some recruiters view patients of color as less promising participants.

“Who ends up being approached for a clinical trial is based on a preset rubric that one has in mind about a patient who may be eligible for a cancer study,” said Dr. Niranjan. “There is a characterization of, ‘we want to make sure this patient is compliant, that they will be a good historian and seem responsible.’ ... Our study showed that it kind of fell along racial lines.”

In her study, published in the journal Cancer in 2020, Dr. Niranjan wrote that researchers sometimes “perceived racial minority groups to have low knowledge of cancer clinical trials. This was considered to be a hindrance while explaining cancer clinical trials in the face of limited provider time during a clinical encounter.”

Some researchers believed minority participants, especially Black women, would be less likely to file study protocols. Others said people of color are more likely to be selfish.

She quoted one research investigator as saying Black people are less knowledgeable.

“African Americans I think have less knowledge,” the unnamed researcher said. “We take a little bit more time to explain to African American [sic]. I think ... they have more questions because we know they are not more knowledgeable so I think it takes time. They have a lot of questions.”

Progress over the years

The FDA’s recent draft builds upon a guidance from 2016, which already recommended that trial teams submit an inclusion plan to the agency at the earliest phase of development. While the recent announcement is another step in the right direction, it may not be substantial enough.

“There’s always an enrollment plan,” Dr. Niranjan said. “But those enrollment plans are not enforced. So if it’s not enforced, what does that look like?”

In an emailed statement to this news organization, Lola Fashoyin-Aje, MD, the deputy director of the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence’s division to expand diversity, emphasized that the draft guidance does not require anything, but that the agency “expect[s] sponsors will follow FDA’s recommendations as described in the draft guidance.”

Without requirements, it’s up to the sponsor to make the effort to enroll people with varied racial and ethnic backgrounds. During the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, Moderna announced that the company would slow the trial’s enrollment to ensure minority groups were properly represented.

Not every sponsor is as motivated to make this a concerted effort, and some simply don’t have the funds to allocate to strengthening the enrollment process.

“There’s so much red tape and paperwork to get the funding for a clinical trial,” said Julie Silver, MD, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies workforce diversity and inclusion. “Even when people are equitably included, the amount of funding they have to do the trial might not be enough to do an analysis that shows potential differences.”

Whether the FDA will enforce enrollment plans in the future remains an open question; however, Dr. Yancy said the most effective way to do this would be through incentives, rather than penalties.

According to Dr. Fashoyin-Aje, the FDA and sponsors “will learn from these submissions and over time, whether and how these diversity plans lead to meaningful changes in clinical trial representation will need to be assessed, including whether additional steps need to be taken.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s no secret that, for decades, the participants in clinical trials for new drugs and medical devices haven’t accurately represented the diverse groups of patients the drugs and devices were designed for.

In a recently published draft guidance, the Food and Drug Administration recommended that companies in charge of running these trials should submit a proposal to the agency that would address how they plan to enroll more “clinically relevant populations” and historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

It’s an issue that the U.S. has been trying to fix for years. In 1993, the NIH Revitalization Act was passed into law. It mandated the appropriate inclusion of women and racial minorities in all National Institutes of Health–funded research.

Since then, the FDA has put out plans that encourage trial sponsors to recruit more diverse enrollees, offering strategies and best practices rather than establishing requirements or quotas that companies would be forced to meet. Despite its efforts to encourage inclusion, people of color continue to be largely underrepresented in clinical trials.

Experts aren’t just calling for trial cohorts to reflect U.S. census data. Rather, the demographics of participants should match those of the diagnosis being studied. An analysis of 24 clinical trials of cardiovascular drugs, for example, found that Black Americans made up 2.9% of trial participants, compared with 83.1% for White people. Given that cardiovascular diseases affect Black Americans at almost the same rate as Whites (23.5% and 23.7%, respectively) – and keeping in mind that Black Americans make up 13.4% of the population and White people represent 76.3% – the degree of underrepresentation is glaring.

One commonly cited reason for this lack of representation is that people of color, especially Black Americans, have lingering feelings of mistrust toward the medical field. The U.S.-run Tuskegee study – during which researchers documented the natural progression of syphilis in hundreds of Black men who were kept from life-saving treatment – is, justifiably, often named as a notable source of that suspicion.

But blaming the disproportionately low numbers of Black participants in clinical trials on medical mistrust is an easy answer to a much more complicated issue, said cardiologist Clyde Yancy, MD, who also serves as the vice dean for diversity and inclusion at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago.

“We need to not put the onus on the back of the patient cohort, and say they are the problem,” Dr. Yancy said, adding that many trials add financial barriers and don’t provide proper transportation for participants who may live farther away.

The diversity of the study team itself – the institutions, researchers, and recruiters – also contributes to a lack of diversity in the participant pool. When considering all of these factors, “you begin to understand the complexity and the multidimensionality of why we have underrepresentation,” said Dr. Yancy. “So I would not promulgate the notion that this is simply because patients don’t trust the system.”

Soumya Niranjan, PhD, worked as a study coordinator at the Tulane Cancer Center in New Orleans, La., where she recruited patients for a prostate cancer study. After researching the impact of clinicians’ biases on the recruitment of racial and ethnic minorities in oncology trials, she found that some recruiters view patients of color as less promising participants.

“Who ends up being approached for a clinical trial is based on a preset rubric that one has in mind about a patient who may be eligible for a cancer study,” said Dr. Niranjan. “There is a characterization of, ‘we want to make sure this patient is compliant, that they will be a good historian and seem responsible.’ ... Our study showed that it kind of fell along racial lines.”

In her study, published in the journal Cancer in 2020, Dr. Niranjan wrote that researchers sometimes “perceived racial minority groups to have low knowledge of cancer clinical trials. This was considered to be a hindrance while explaining cancer clinical trials in the face of limited provider time during a clinical encounter.”

Some researchers believed minority participants, especially Black women, would be less likely to file study protocols. Others said people of color are more likely to be selfish.

She quoted one research investigator as saying Black people are less knowledgeable.

“African Americans I think have less knowledge,” the unnamed researcher said. “We take a little bit more time to explain to African American [sic]. I think ... they have more questions because we know they are not more knowledgeable so I think it takes time. They have a lot of questions.”

Progress over the years

The FDA’s recent draft builds upon a guidance from 2016, which already recommended that trial teams submit an inclusion plan to the agency at the earliest phase of development. While the recent announcement is another step in the right direction, it may not be substantial enough.

“There’s always an enrollment plan,” Dr. Niranjan said. “But those enrollment plans are not enforced. So if it’s not enforced, what does that look like?”

In an emailed statement to this news organization, Lola Fashoyin-Aje, MD, the deputy director of the FDA Oncology Center of Excellence’s division to expand diversity, emphasized that the draft guidance does not require anything, but that the agency “expect[s] sponsors will follow FDA’s recommendations as described in the draft guidance.”

Without requirements, it’s up to the sponsor to make the effort to enroll people with varied racial and ethnic backgrounds. During the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, Moderna announced that the company would slow the trial’s enrollment to ensure minority groups were properly represented.

Not every sponsor is as motivated to make this a concerted effort, and some simply don’t have the funds to allocate to strengthening the enrollment process.

“There’s so much red tape and paperwork to get the funding for a clinical trial,” said Julie Silver, MD, professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies workforce diversity and inclusion. “Even when people are equitably included, the amount of funding they have to do the trial might not be enough to do an analysis that shows potential differences.”

Whether the FDA will enforce enrollment plans in the future remains an open question; however, Dr. Yancy said the most effective way to do this would be through incentives, rather than penalties.

According to Dr. Fashoyin-Aje, the FDA and sponsors “will learn from these submissions and over time, whether and how these diversity plans lead to meaningful changes in clinical trial representation will need to be assessed, including whether additional steps need to be taken.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Advancing digital health care past pandemic-driven telemedicine

COVID-19 forced consumers to adopt digital and virtual platforms to receive medical care, and more than 2 years after the start of the pandemic, it doesn’t appear that that will change.

“During the pandemic we witnessed a very steep rise in the utilization of digital health care transactions. And as we have now witnessed a plateau, we see that digital health care transactions have not fallen back to the way things were prepandemic,” said Bart M. Demaerschalk, MD, professor and chair of cerebrovascular diseases for digital health research at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Ariz. “At Mayo Clinic and other health care organizations, approximately 20% ... of the composite care is occurring by digital means.”

Dr. Demaerschalk was among a panel representing retail and traditional health care organizations at the American Telemedicine Association conference in Boston.

The pandemic created this new reality, and health care leaders are now trying to make the most of all digital tools. Marcus Osborne, former senior vice president at Walmart Health, said that to progress, the health care industry needs to move beyond the conception of a world in which consumers interact with care providers via one-off in-person or digital experiences.

“What we’re actually seeing in other sectors and in life in general is that the world is not multichannel. The world is omnichannel,” Mr. Osborne said. Under an omnichannel paradigm, provider organizations integrate multiple digital and in-person health delivery methods, making it possible to “create whole new experiences for consumers that no one channel could deliver,” he added.

Creagh Milford, DO, vice president and head of enterprise virtual care at CVS Health, agreed and added that “the retail footprint will evolve” from offering separate physical and virtual care experiences to a “blended” experience.

To move in this direction, health care leaders need to “stop talking about the site of care so much,” said Christopher McCann, MBChB, CEO and cofounder of the health IT firm Current Health. Instead of “fixating” on either brick-and-mortar or digital experiences, leaders should meet “the consumer where they are and deliver what is the most appropriate care to that consumer in the most appropriate setting,” Dr. McCann said.

Three key digital technology strategies

In addition to supporting an omnichannel experience, the panelists pointed out that traditional and retail health care providers can make the most of digital technologies in a few different ways.

One is by helping consumers manage innovation. With venture capital investments in digital technologies at an all-time high, the health care industry is drowning in innovation, <r/ Osborne pointed out.