User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Depression biomarkers: Which ones matter most?

Multiple biomarkers of depression involved in several brain circuits are altered in patients with unipolar depression.

because they suggest neuroimmunological alterations, disturbances in the blood-brain-barrier, hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and impaired neuroplasticity as factors in depression pathophysiology.

However, said study investigator Michael E. Benros, MD, PhD, professor and head of research at Mental Health Centre Copenhagen and University of Copenhagen, this is on a group level. “So in order to be relevant in a clinical context, the results need to be validated by further high-quality studies identifying subgroups with different biological underpinnings,” he told this news organization.

Identification of potential subgroups of depression with different biomarkers might help explain the diverse symptomatology and variability in treatment response observed in patients with depression, he noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Multiple pathways to depression

The systematic review and meta-analysis included 97 studies investigating 165 CSF biomarkers.

Of the 42 biomarkers investigated in at least two studies, patients with unipolar depression had higher CSF levels of interleukin 6, a marker of chronic inflammation; total protein, which signals blood-brain barrier dysfunction and increased permeability; and cortisol, which is linked to psychological stress, compared with healthy controls.

Depression was also associated with:

- Lower CSF levels of homovanillic acid, the major terminal metabolite of dopamine.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS thought to play a vital role in the control of stress and depression.

- Somatostatin, a neuropeptide often coexpressed with GABA.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission.

- Amyloid-β 40, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Transthyretin, involved in transport of thyroxine across the blood-brain barrier.

Collectively, the findings point toward a “dysregulated dopaminergic system, a compromised inhibitory system, HPA axis hyperactivity, increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability, and impaired neuroplasticity as important factors in depression pathophysiology,” the investigators wrote.

“It is notable that we did not find significant difference in the metabolite levels of serotonin and noradrenalin, which are the most targeted neurotransmitters in modern antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Benros.

However, this could be explained by substantial heterogeneity between studies and the fact that quantification of total CSF biomarker concentrations does not reflect local alteration within the brain, he explained.

Many of the studies had small cohorts and most quantified only a few biomarkers, making it hard to examine potential interactions between biomarkers or identify specific phenotypes of depression.

“Novel high-quality studies including larger cohorts with an integrative approach and extensive numbers of biomarkers are needed to validate these potential biomarkers of depression and set the stage for the development of more effective and precise treatments,” the researchers noted.

Which ones hold water?

Reached for comment, Dean MacKinnon, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that this analysis “extracts the vast amount of knowledge” gained from different studies on biomarkers in the CSF for depression.

“They were able to identify 97 papers that have enough information in them that they could sort of lump them together and see which ones still hold water. It’s always useful to be able to look at patterns in the research and see if you can find some consistent trends,” he told this news organization.

Dr. MacKinnon, who was not part of the research team, also noted that “nonreplicability” is a problem in psychiatry and psychology research, “so being able to show that at least some studies were sufficiently well done, to get a good result, and that they could be replicated in at least one other good study is useful information.”

When it comes to depression, Dr. MacKinnon said, “We just don’t know enough to really pin down a physiologic pathway to explain it. The fact that some people seem to have high cortisol and some people seem to have high permeability of blood-brain barrier, and others have abnormalities in dopamine, is interesting and suggests that depression is likely not a unitary disease with a single cause.”

He cautioned, however, that the findings don’t have immediate clinical implications for individual patients with depression.

“Theoretically, down the road, if you extrapolate from what they found, and if it’s truly the case that this research maps to something that could suggest a different clinical approach, you might be able to determine whether one patient might respond better to an SSRI or an SNRI or something like that,” Dr. MacKinnon said.

Dr. Benros reported grants from Lundbeck Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr. MacKinnon has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple biomarkers of depression involved in several brain circuits are altered in patients with unipolar depression.

because they suggest neuroimmunological alterations, disturbances in the blood-brain-barrier, hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and impaired neuroplasticity as factors in depression pathophysiology.

However, said study investigator Michael E. Benros, MD, PhD, professor and head of research at Mental Health Centre Copenhagen and University of Copenhagen, this is on a group level. “So in order to be relevant in a clinical context, the results need to be validated by further high-quality studies identifying subgroups with different biological underpinnings,” he told this news organization.

Identification of potential subgroups of depression with different biomarkers might help explain the diverse symptomatology and variability in treatment response observed in patients with depression, he noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Multiple pathways to depression

The systematic review and meta-analysis included 97 studies investigating 165 CSF biomarkers.

Of the 42 biomarkers investigated in at least two studies, patients with unipolar depression had higher CSF levels of interleukin 6, a marker of chronic inflammation; total protein, which signals blood-brain barrier dysfunction and increased permeability; and cortisol, which is linked to psychological stress, compared with healthy controls.

Depression was also associated with:

- Lower CSF levels of homovanillic acid, the major terminal metabolite of dopamine.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS thought to play a vital role in the control of stress and depression.

- Somatostatin, a neuropeptide often coexpressed with GABA.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission.

- Amyloid-β 40, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Transthyretin, involved in transport of thyroxine across the blood-brain barrier.

Collectively, the findings point toward a “dysregulated dopaminergic system, a compromised inhibitory system, HPA axis hyperactivity, increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability, and impaired neuroplasticity as important factors in depression pathophysiology,” the investigators wrote.

“It is notable that we did not find significant difference in the metabolite levels of serotonin and noradrenalin, which are the most targeted neurotransmitters in modern antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Benros.

However, this could be explained by substantial heterogeneity between studies and the fact that quantification of total CSF biomarker concentrations does not reflect local alteration within the brain, he explained.

Many of the studies had small cohorts and most quantified only a few biomarkers, making it hard to examine potential interactions between biomarkers or identify specific phenotypes of depression.

“Novel high-quality studies including larger cohorts with an integrative approach and extensive numbers of biomarkers are needed to validate these potential biomarkers of depression and set the stage for the development of more effective and precise treatments,” the researchers noted.

Which ones hold water?

Reached for comment, Dean MacKinnon, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that this analysis “extracts the vast amount of knowledge” gained from different studies on biomarkers in the CSF for depression.

“They were able to identify 97 papers that have enough information in them that they could sort of lump them together and see which ones still hold water. It’s always useful to be able to look at patterns in the research and see if you can find some consistent trends,” he told this news organization.

Dr. MacKinnon, who was not part of the research team, also noted that “nonreplicability” is a problem in psychiatry and psychology research, “so being able to show that at least some studies were sufficiently well done, to get a good result, and that they could be replicated in at least one other good study is useful information.”

When it comes to depression, Dr. MacKinnon said, “We just don’t know enough to really pin down a physiologic pathway to explain it. The fact that some people seem to have high cortisol and some people seem to have high permeability of blood-brain barrier, and others have abnormalities in dopamine, is interesting and suggests that depression is likely not a unitary disease with a single cause.”

He cautioned, however, that the findings don’t have immediate clinical implications for individual patients with depression.

“Theoretically, down the road, if you extrapolate from what they found, and if it’s truly the case that this research maps to something that could suggest a different clinical approach, you might be able to determine whether one patient might respond better to an SSRI or an SNRI or something like that,” Dr. MacKinnon said.

Dr. Benros reported grants from Lundbeck Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr. MacKinnon has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple biomarkers of depression involved in several brain circuits are altered in patients with unipolar depression.

because they suggest neuroimmunological alterations, disturbances in the blood-brain-barrier, hyperactivity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and impaired neuroplasticity as factors in depression pathophysiology.

However, said study investigator Michael E. Benros, MD, PhD, professor and head of research at Mental Health Centre Copenhagen and University of Copenhagen, this is on a group level. “So in order to be relevant in a clinical context, the results need to be validated by further high-quality studies identifying subgroups with different biological underpinnings,” he told this news organization.

Identification of potential subgroups of depression with different biomarkers might help explain the diverse symptomatology and variability in treatment response observed in patients with depression, he noted.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Multiple pathways to depression

The systematic review and meta-analysis included 97 studies investigating 165 CSF biomarkers.

Of the 42 biomarkers investigated in at least two studies, patients with unipolar depression had higher CSF levels of interleukin 6, a marker of chronic inflammation; total protein, which signals blood-brain barrier dysfunction and increased permeability; and cortisol, which is linked to psychological stress, compared with healthy controls.

Depression was also associated with:

- Lower CSF levels of homovanillic acid, the major terminal metabolite of dopamine.

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS thought to play a vital role in the control of stress and depression.

- Somatostatin, a neuropeptide often coexpressed with GABA.

- Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission.

- Amyloid-β 40, implicated in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Transthyretin, involved in transport of thyroxine across the blood-brain barrier.

Collectively, the findings point toward a “dysregulated dopaminergic system, a compromised inhibitory system, HPA axis hyperactivity, increased neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier permeability, and impaired neuroplasticity as important factors in depression pathophysiology,” the investigators wrote.

“It is notable that we did not find significant difference in the metabolite levels of serotonin and noradrenalin, which are the most targeted neurotransmitters in modern antidepressant treatment,” said Dr. Benros.

However, this could be explained by substantial heterogeneity between studies and the fact that quantification of total CSF biomarker concentrations does not reflect local alteration within the brain, he explained.

Many of the studies had small cohorts and most quantified only a few biomarkers, making it hard to examine potential interactions between biomarkers or identify specific phenotypes of depression.

“Novel high-quality studies including larger cohorts with an integrative approach and extensive numbers of biomarkers are needed to validate these potential biomarkers of depression and set the stage for the development of more effective and precise treatments,” the researchers noted.

Which ones hold water?

Reached for comment, Dean MacKinnon, MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, noted that this analysis “extracts the vast amount of knowledge” gained from different studies on biomarkers in the CSF for depression.

“They were able to identify 97 papers that have enough information in them that they could sort of lump them together and see which ones still hold water. It’s always useful to be able to look at patterns in the research and see if you can find some consistent trends,” he told this news organization.

Dr. MacKinnon, who was not part of the research team, also noted that “nonreplicability” is a problem in psychiatry and psychology research, “so being able to show that at least some studies were sufficiently well done, to get a good result, and that they could be replicated in at least one other good study is useful information.”

When it comes to depression, Dr. MacKinnon said, “We just don’t know enough to really pin down a physiologic pathway to explain it. The fact that some people seem to have high cortisol and some people seem to have high permeability of blood-brain barrier, and others have abnormalities in dopamine, is interesting and suggests that depression is likely not a unitary disease with a single cause.”

He cautioned, however, that the findings don’t have immediate clinical implications for individual patients with depression.

“Theoretically, down the road, if you extrapolate from what they found, and if it’s truly the case that this research maps to something that could suggest a different clinical approach, you might be able to determine whether one patient might respond better to an SSRI or an SNRI or something like that,” Dr. MacKinnon said.

Dr. Benros reported grants from Lundbeck Foundation during the conduct of the study. Dr. MacKinnon has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Burnout ‘highly prevalent’ in psychiatrists across the globe

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

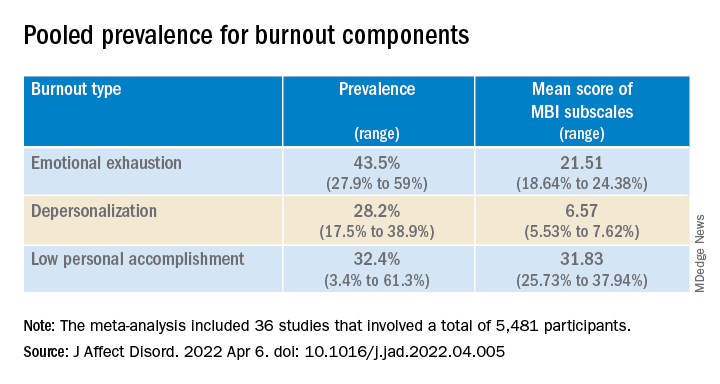

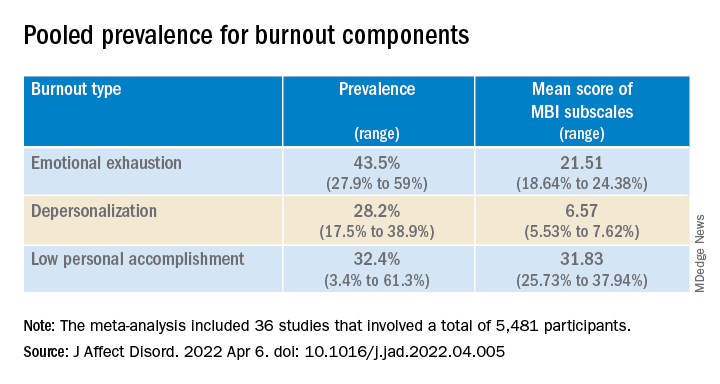

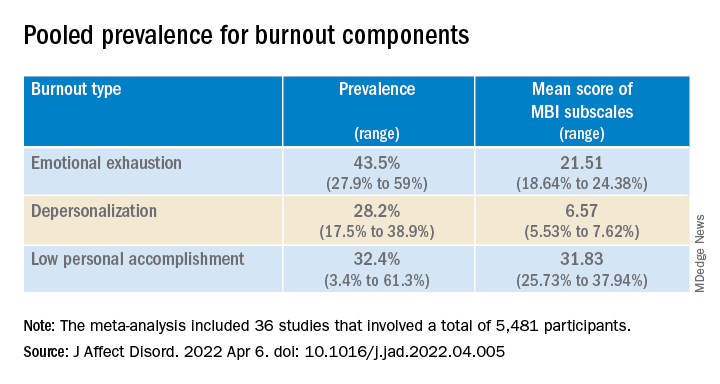

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Burnout in psychiatrists is “highly prevalent” across the globe, new research shows.

In a review and meta-analysis of 36 studies and more than 5,000 psychiatrists in European countries, as well as the United States, Australia, New Zealand, India, Turkey, and Thailand,

“Our review showed that regardless of the identification method of burnout, its prevalence among psychiatrists is high and ranges from 25% to 50%,” lead author Kirill Bykov, MD, a PhD candidate at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Moscow, Russian Federation, told this news organization.

There was a “high heterogeneity of studies in terms of statistics, screening methods, burnout definitions, and cutoff points in the included studies, which necessitates the unification of future research methodology, but not to the detriment of the development of the theoretical background,” Dr. Bykov said.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

‘Unresolved problem’

Although burnout is a serious and prevalent problem among health care workers, little research has focused on burnout in mental health workers compared with other professionals, the investigators noted.

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis that focused specifically on burnout in psychiatrists was limited by methodologic concerns, including that the only burnout screening instrument used in the included studies was the full-length (22-item) MBI.

The current researchers surmised that “the integration of different empirical studies of psychiatrists’ burnout prevalence [remained] an unresolved problem.”

Dr. Bykov noted the current review was “investigator-initiated” and was a part of his PhD dissertation.

“Studying the works devoted to the burnout of psychiatrists, I drew attention to the varying prevalence rates of this phenomenon among them. This prompted me to conduct a systematic review of the literature and summarize the available data,” he said.

Unlike the previous review, the current one “does not contain restrictions regarding the place of research, publication language, covered burnout concepts, definitions, and screening instruments. Thus, its results will be helpful for practitioners and scientists around the world,” Dr. Bykov added.

Among the inclusion criteria was that a study should be empirical and quantitative, contain at least 20 practicing psychiatrists as participants, use a valid and reliable burnout screening instrument, have at least one burnout metric extractable specifically with regard to psychiatrists, and have a national survey or a response rate among psychiatrists of 20% or greater.

Qualitative or review articles or studies consisting of psychiatric trainees (such as medical students or residents) or nonpracticing psychiatrists were excluded.

Pooled prevalence

The researchers included 36 studies that comprised 5,481 participants (51.3% were women; mean age, 46.7 years). All studies had from 20 to 1,157 participants. They were employed in an array of settings in 19 countries.

In 22 studies, survey years ranged from 1996 to 2018; 14 studies did not report the year of data collection.

Most studies (75%) used some version of the MBI, and 19 studies used the full-length 22-item MBI Human Service Survey (MBI-HSS) . The survey rates emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 6 (“almost every day”).

Other instruments included the CBI, the 16-item Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the 21-item Tedium Measure, the 30-item Professional Quality of Life measure, the Rohland et al. Single-Item Measure of Self-Perceived Burnout, and the 21-item Brief Burnout Questionnaire.

Only three studies were free of methodologic limitations. The remaining 33 studies had some problems, such as not reporting the response rate or comparability between responders and nonresponders.

Results showed that the overall prevalence of burnout, as measured by the MBI and the CBI, was 25.9% (range, 11.1%-40.75%) and 50.3% (range, 30.9%-69.8%), respectively.

The pooled prevalence for burnout components is shown in the table.

European psychiatrists had lower EE scores (20.82; 95% confidence interval, 7.24-4.41) compared with their non-European counterparts (24.99; 95% CI, 23.05-26.94; P = .045).

‘Carry the hope’

In a comment, Christine Crawford, MD, associate medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), said she was surprised the burnout numbers weren’t higher.

Many colleagues she interacts with “have been experiencing pretty significant burnout that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic and ever-growing demand for mental health providers, and there aren’t enough to meet that demand,” said Dr. Crawford, a psychiatrist at Boston Medical Center’s Outpatient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Clinic and at Codman Square Health Center. She was not involved with the current research.

Dr. Crawford noted that much of the data was from Europeans. Speaking to the experience of U.S.-based psychiatrists, she said there is a “greater appreciation for what we do as mental health providers, due to the growing conversations around mental health and normalizing mental health conditions.”

On the other hand, there is “a lack of parity in reimbursement rates. Although the general public values mental health, the medical system doesn’t value mental health providers in the same way as physicians in other specialties,” Dr. Crawford said. Feeling devalued can contribute to burnout, she added.

One way to counter burnout is to remember “that our role is to carry the hope. We can be hopeful for the patient that the treatment will work or the medications can provide some relief,” Dr. Crawford noted.

Psychiatrists “may need to hold on tightly to that hope because we may not receive that instant gratification from the patient or receive praise or see the change from the patient during that time, which can be challenging,” she said.

“But it’s important for us to keep in mind that, even in that moment when the patient can’t see it, we can work alongside the patient to create the vision of hope and what it will look like in the future,” said Dr. Crawford.

In the 2022 Medscape Psychiatrist Lifestyle, Happiness & Burnout Report, an annual online survey of Medscape member physicians, 47% of respondents reported burnout – which was up from 42% the previous year.

The investigators received no funding for this work. They and Dr. Crawford report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Seven hours of sleep is ideal for middle aged and older

Sleep disturbances are common in older age, and previous studies have shown associations between too much or too little sleep and increased risk of cognitive decline, but the ideal amount of sleep for preserving mental health has not been well described, according to the authors of the new paper.

In the study published in Nature Aging, the team of researchers from China and the United Kingdom reviewed data from the UK Biobank, a national database of individuals in the United Kingdom that includes cognitive assessments, mental health questionnaires, and brain imaging data, as well as genetic information.

Sleep is important for physical and psychological health, and also serves a neuroprotective function by clearing waste products from the brain, lead author Yuzhu Li of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues wrote.

The study population included 498,277 participants, aged 38-73 years, who completed touchscreen questionnaires about sleep duration between 2006 and 2010. The average age at baseline was 56.5 years, 54% were female, and the mean sleep duration was 7.15 hours.

The researchers also reviewed brain imaging data and genetic data from 39,692 participants in 2014 to examine the relationships between sleep duration and brain structure and between sleep duration and genetic risk. In addition, 156,884 participants completed an online follow-up mental health questionnaire in 2016-2017 to assess the longitudinal impact of sleep on mental health.

Both excessive and insufficient sleep was associated with impaired cognitive performance, evidenced by the U-shaped curve found by the researchers in their data analysis, which used quadratic associations.

Specific cognitive functions including pair matching, trail making, prospective memory, and reaction time were significantly impaired with too much or too little sleep, the researchers said. “This demonstrated the positive association of both insufficient and excessive sleep duration with inferior performance on cognitive tasks.”

When the researchers analyzed the association between sleep duration and mental health, sleep duration also showed a U-shaped association with symptoms of anxiety, depression, mental distress, mania, and self-harm, while well-being showed an inverted U-shape. All associations between sleep duration and mental health were statistically significant after controlling for confounding variables (P < .001).

On further analysis (using two-line tests), the researchers determined that consistent sleep duration of approximately 7 hours per night was optimal for cognitive performance and for good mental health.

The researchers also used neuroimaging data to examine the relationship between sleep duration and brain structure. Overall, greater changes were seen in the regions of the brain involved in cognitive processing and memory.

“The most significant cortical volumes nonlinearly associated with sleep duration included the precentral cortex, the superior frontal gyrus, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, the pars orbitalis, the frontal pole, and the middle temporal cortex,” the researchers wrote (P < .05 for all).

The association between sleep duration and cognitive function diminished among individuals older than 65 years, compared with those aged approximately 40 years, which suggests that optimal sleep duration may be more beneficial in middle age, the researchers noted. However, no similar impact of age was seen for mental health. For brain structure, the nonlinear relationship between sleep duration and cortical volumes was greatest in those aged 44-59 years, and gradually flattened with older age.

Research supports sleep discussions with patients

“Primary care physicians can use this study in their discussions with middle-aged and older patients to recommend optimal sleep duration and measures to achieve this sleep target,” Noel Deep, MD, a general internist in group practice in Antigo, Wisc., who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

“This study is important because it demonstrated that both inadequate and excessive sleep patterns were associated with cognitive and mental health changes,” said Dr. Deep. “It supported previous observations of cognitive decline and mental health disorders being linked to disturbed sleep. But this study was unique because it provides data supporting an optimal sleep duration of 7 hours and the ill effects of both insufficient and excessive sleep duration.

“The usual thought process has been to assume that older individuals may not require as much sleep as the younger individuals, but this study supports an optimal time duration of sleep of 7 hours that benefits the older individuals. It was also interesting to note the mental health effects caused by the inadequate and excessive sleep durations,” he added.

As for additional research, “I would like to look into the quality of the sleep, in addition to the duration of sleep,” said Dr. Deep. For example, whether the excessive sleep was caused by poor quality sleep or fragmented sleep leading to the structural and subsequent cognitive decline.

Study limitations

“The current study relied on self-reporting of the sleep duration and was not observed and recorded data,” Dr. Deep noted. “It would also be beneficial to not only rely on healthy volunteers reporting the sleep duration, but also obtain sleep data from individuals with known brain disorders.”

The study findings were limited by several other factors, including the use of total sleep duration only, without other measures of sleep hygiene, the researchers noted. More research is needed to investigate the mechanisms driving the association between too much and not enough sleep and poor mental health and cognitive function.

The study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China, the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project, the Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology, the 111 Project, the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China and the Shanghai Rising Star Program.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

Sleep disturbances are common in older age, and previous studies have shown associations between too much or too little sleep and increased risk of cognitive decline, but the ideal amount of sleep for preserving mental health has not been well described, according to the authors of the new paper.

In the study published in Nature Aging, the team of researchers from China and the United Kingdom reviewed data from the UK Biobank, a national database of individuals in the United Kingdom that includes cognitive assessments, mental health questionnaires, and brain imaging data, as well as genetic information.

Sleep is important for physical and psychological health, and also serves a neuroprotective function by clearing waste products from the brain, lead author Yuzhu Li of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues wrote.

The study population included 498,277 participants, aged 38-73 years, who completed touchscreen questionnaires about sleep duration between 2006 and 2010. The average age at baseline was 56.5 years, 54% were female, and the mean sleep duration was 7.15 hours.

The researchers also reviewed brain imaging data and genetic data from 39,692 participants in 2014 to examine the relationships between sleep duration and brain structure and between sleep duration and genetic risk. In addition, 156,884 participants completed an online follow-up mental health questionnaire in 2016-2017 to assess the longitudinal impact of sleep on mental health.

Both excessive and insufficient sleep was associated with impaired cognitive performance, evidenced by the U-shaped curve found by the researchers in their data analysis, which used quadratic associations.

Specific cognitive functions including pair matching, trail making, prospective memory, and reaction time were significantly impaired with too much or too little sleep, the researchers said. “This demonstrated the positive association of both insufficient and excessive sleep duration with inferior performance on cognitive tasks.”

When the researchers analyzed the association between sleep duration and mental health, sleep duration also showed a U-shaped association with symptoms of anxiety, depression, mental distress, mania, and self-harm, while well-being showed an inverted U-shape. All associations between sleep duration and mental health were statistically significant after controlling for confounding variables (P < .001).

On further analysis (using two-line tests), the researchers determined that consistent sleep duration of approximately 7 hours per night was optimal for cognitive performance and for good mental health.

The researchers also used neuroimaging data to examine the relationship between sleep duration and brain structure. Overall, greater changes were seen in the regions of the brain involved in cognitive processing and memory.

“The most significant cortical volumes nonlinearly associated with sleep duration included the precentral cortex, the superior frontal gyrus, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, the pars orbitalis, the frontal pole, and the middle temporal cortex,” the researchers wrote (P < .05 for all).

The association between sleep duration and cognitive function diminished among individuals older than 65 years, compared with those aged approximately 40 years, which suggests that optimal sleep duration may be more beneficial in middle age, the researchers noted. However, no similar impact of age was seen for mental health. For brain structure, the nonlinear relationship between sleep duration and cortical volumes was greatest in those aged 44-59 years, and gradually flattened with older age.

Research supports sleep discussions with patients

“Primary care physicians can use this study in their discussions with middle-aged and older patients to recommend optimal sleep duration and measures to achieve this sleep target,” Noel Deep, MD, a general internist in group practice in Antigo, Wisc., who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

“This study is important because it demonstrated that both inadequate and excessive sleep patterns were associated with cognitive and mental health changes,” said Dr. Deep. “It supported previous observations of cognitive decline and mental health disorders being linked to disturbed sleep. But this study was unique because it provides data supporting an optimal sleep duration of 7 hours and the ill effects of both insufficient and excessive sleep duration.

“The usual thought process has been to assume that older individuals may not require as much sleep as the younger individuals, but this study supports an optimal time duration of sleep of 7 hours that benefits the older individuals. It was also interesting to note the mental health effects caused by the inadequate and excessive sleep durations,” he added.

As for additional research, “I would like to look into the quality of the sleep, in addition to the duration of sleep,” said Dr. Deep. For example, whether the excessive sleep was caused by poor quality sleep or fragmented sleep leading to the structural and subsequent cognitive decline.

Study limitations

“The current study relied on self-reporting of the sleep duration and was not observed and recorded data,” Dr. Deep noted. “It would also be beneficial to not only rely on healthy volunteers reporting the sleep duration, but also obtain sleep data from individuals with known brain disorders.”

The study findings were limited by several other factors, including the use of total sleep duration only, without other measures of sleep hygiene, the researchers noted. More research is needed to investigate the mechanisms driving the association between too much and not enough sleep and poor mental health and cognitive function.

The study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China, the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project, the Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology, the 111 Project, the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China and the Shanghai Rising Star Program.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

Sleep disturbances are common in older age, and previous studies have shown associations between too much or too little sleep and increased risk of cognitive decline, but the ideal amount of sleep for preserving mental health has not been well described, according to the authors of the new paper.

In the study published in Nature Aging, the team of researchers from China and the United Kingdom reviewed data from the UK Biobank, a national database of individuals in the United Kingdom that includes cognitive assessments, mental health questionnaires, and brain imaging data, as well as genetic information.

Sleep is important for physical and psychological health, and also serves a neuroprotective function by clearing waste products from the brain, lead author Yuzhu Li of Fudan University, Shanghai, China, and colleagues wrote.

The study population included 498,277 participants, aged 38-73 years, who completed touchscreen questionnaires about sleep duration between 2006 and 2010. The average age at baseline was 56.5 years, 54% were female, and the mean sleep duration was 7.15 hours.

The researchers also reviewed brain imaging data and genetic data from 39,692 participants in 2014 to examine the relationships between sleep duration and brain structure and between sleep duration and genetic risk. In addition, 156,884 participants completed an online follow-up mental health questionnaire in 2016-2017 to assess the longitudinal impact of sleep on mental health.

Both excessive and insufficient sleep was associated with impaired cognitive performance, evidenced by the U-shaped curve found by the researchers in their data analysis, which used quadratic associations.

Specific cognitive functions including pair matching, trail making, prospective memory, and reaction time were significantly impaired with too much or too little sleep, the researchers said. “This demonstrated the positive association of both insufficient and excessive sleep duration with inferior performance on cognitive tasks.”

When the researchers analyzed the association between sleep duration and mental health, sleep duration also showed a U-shaped association with symptoms of anxiety, depression, mental distress, mania, and self-harm, while well-being showed an inverted U-shape. All associations between sleep duration and mental health were statistically significant after controlling for confounding variables (P < .001).

On further analysis (using two-line tests), the researchers determined that consistent sleep duration of approximately 7 hours per night was optimal for cognitive performance and for good mental health.

The researchers also used neuroimaging data to examine the relationship between sleep duration and brain structure. Overall, greater changes were seen in the regions of the brain involved in cognitive processing and memory.

“The most significant cortical volumes nonlinearly associated with sleep duration included the precentral cortex, the superior frontal gyrus, the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, the pars orbitalis, the frontal pole, and the middle temporal cortex,” the researchers wrote (P < .05 for all).

The association between sleep duration and cognitive function diminished among individuals older than 65 years, compared with those aged approximately 40 years, which suggests that optimal sleep duration may be more beneficial in middle age, the researchers noted. However, no similar impact of age was seen for mental health. For brain structure, the nonlinear relationship between sleep duration and cortical volumes was greatest in those aged 44-59 years, and gradually flattened with older age.

Research supports sleep discussions with patients

“Primary care physicians can use this study in their discussions with middle-aged and older patients to recommend optimal sleep duration and measures to achieve this sleep target,” Noel Deep, MD, a general internist in group practice in Antigo, Wisc., who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

“This study is important because it demonstrated that both inadequate and excessive sleep patterns were associated with cognitive and mental health changes,” said Dr. Deep. “It supported previous observations of cognitive decline and mental health disorders being linked to disturbed sleep. But this study was unique because it provides data supporting an optimal sleep duration of 7 hours and the ill effects of both insufficient and excessive sleep duration.

“The usual thought process has been to assume that older individuals may not require as much sleep as the younger individuals, but this study supports an optimal time duration of sleep of 7 hours that benefits the older individuals. It was also interesting to note the mental health effects caused by the inadequate and excessive sleep durations,” he added.

As for additional research, “I would like to look into the quality of the sleep, in addition to the duration of sleep,” said Dr. Deep. For example, whether the excessive sleep was caused by poor quality sleep or fragmented sleep leading to the structural and subsequent cognitive decline.

Study limitations

“The current study relied on self-reporting of the sleep duration and was not observed and recorded data,” Dr. Deep noted. “It would also be beneficial to not only rely on healthy volunteers reporting the sleep duration, but also obtain sleep data from individuals with known brain disorders.”

The study findings were limited by several other factors, including the use of total sleep duration only, without other measures of sleep hygiene, the researchers noted. More research is needed to investigate the mechanisms driving the association between too much and not enough sleep and poor mental health and cognitive function.

The study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China, the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project, the Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology, the 111 Project, the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China and the Shanghai Rising Star Program.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

FROM NATURE AGING

Severe COVID-19 adds 20 years of cognitive aging: Study

adding that the impairment is “equivalent to losing 10 IQ points.”

In their study, published in eClinicalMedicine, a team of scientists from the University of Cambridge and Imperial College London said there is growing evidence that COVID-19 can cause lasting cognitive and mental health problems. Patients report fatigue, “brain fog,” problems recalling words, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and even posttraumatic stress disorder months after infection.

The researchers analyzed data from 46 individuals who received critical care for COVID-19 at Addenbrooke’s Hospital between March and July 2020 (27 females, 19 males, mean age 51 years, 16 of whom had mechanical ventilation) and were recruited to the NIHR COVID-19 BioResource project.

At an average of 6 months after acute COVID-19 illness, the study participants underwent detailed computerized cognitive tests via the Cognitron platform, comprising eight tasks deployed on an iPad measuring mental function such as memory, attention, and reasoning. Also assessed were anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder via standard mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress scales – specifically the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), and the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (PCL-5). Their data were compared against 460 controls – matched for age, sex, education, and first language – and the pattern of deficits across tasks was qualitatively compared with normal age-related decline and early-stage dementia.

Less accurate and slower response times

The authors highlighted how this was the first time a “rigorous assessment and comparison” had been carried out in relation to the after-effects of severe COVID-19.

“Cognitive impairment is common to a wide range of neurological disorders, including dementia, and even routine aging, but the patterns we saw – the cognitive ‘fingerprint’ of COVID-19 – was distinct from all of these,” said David Menon, MD, division of anesthesia at the University of Cambridge, England, and the study’s senior author.

The scientists found that COVID-19 survivors were less accurate and had slower response times than the control population, and added that survivors scored particularly poorly on verbal analogical reasoning and showed slower processing speeds.

Critically, the scale of the cognitive deficits correlated with acute illness severity, but not fatigue or mental health status at the time of cognitive assessment, said the authors.

Recovery ‘at best gradual’

The effects were strongest for those with more severe acute illness, and who required mechanical ventilation, said the authors, who found that acute illness severity was “better at predicting the cognitive deficits.”

The authors pointed out how these deficits were still detectable when patients were followed up 6 months later, and that, although patients’ scores and reaction times began to improve over time, any recovery was “at best gradual” and likely to be influenced by factors such as illness severity and its neurological or psychological impacts.

“We followed some patients up as late as 10 months after their acute infection, so were able to see a very slow improvement,” Dr. Menon said. He explained how, while this improvement was not statistically significant, it was “at least heading in the right direction.”

However, he warned it is very possible that some of these individuals “will never fully recover.”

The cognitive deficits observed may be due to several factors in combination, said the authors, including inadequate oxygen or blood supply to the brain, blockage of large or small blood vessels due to clotting, and microscopic bleeds. They highlighted how the most important mechanism, however, may be “damage caused by the body’s own inflammatory response and immune system.”

Adam Hampshire, PhD, of the department of brain sciences at Imperial College London, one of the study’s authors, described how around 40,000 people have been through intensive care with COVID-19 in England alone, with many more despite having been very sick not admitted to hospital. This means there is a “large number of people out there still experiencing problems with cognition many months later,” he said. “We urgently need to look at what can be done to help these people.”

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.

adding that the impairment is “equivalent to losing 10 IQ points.”

In their study, published in eClinicalMedicine, a team of scientists from the University of Cambridge and Imperial College London said there is growing evidence that COVID-19 can cause lasting cognitive and mental health problems. Patients report fatigue, “brain fog,” problems recalling words, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and even posttraumatic stress disorder months after infection.

The researchers analyzed data from 46 individuals who received critical care for COVID-19 at Addenbrooke’s Hospital between March and July 2020 (27 females, 19 males, mean age 51 years, 16 of whom had mechanical ventilation) and were recruited to the NIHR COVID-19 BioResource project.

At an average of 6 months after acute COVID-19 illness, the study participants underwent detailed computerized cognitive tests via the Cognitron platform, comprising eight tasks deployed on an iPad measuring mental function such as memory, attention, and reasoning. Also assessed were anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder via standard mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress scales – specifically the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), and the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (PCL-5). Their data were compared against 460 controls – matched for age, sex, education, and first language – and the pattern of deficits across tasks was qualitatively compared with normal age-related decline and early-stage dementia.

Less accurate and slower response times

The authors highlighted how this was the first time a “rigorous assessment and comparison” had been carried out in relation to the after-effects of severe COVID-19.

“Cognitive impairment is common to a wide range of neurological disorders, including dementia, and even routine aging, but the patterns we saw – the cognitive ‘fingerprint’ of COVID-19 – was distinct from all of these,” said David Menon, MD, division of anesthesia at the University of Cambridge, England, and the study’s senior author.

The scientists found that COVID-19 survivors were less accurate and had slower response times than the control population, and added that survivors scored particularly poorly on verbal analogical reasoning and showed slower processing speeds.

Critically, the scale of the cognitive deficits correlated with acute illness severity, but not fatigue or mental health status at the time of cognitive assessment, said the authors.

Recovery ‘at best gradual’

The effects were strongest for those with more severe acute illness, and who required mechanical ventilation, said the authors, who found that acute illness severity was “better at predicting the cognitive deficits.”

The authors pointed out how these deficits were still detectable when patients were followed up 6 months later, and that, although patients’ scores and reaction times began to improve over time, any recovery was “at best gradual” and likely to be influenced by factors such as illness severity and its neurological or psychological impacts.

“We followed some patients up as late as 10 months after their acute infection, so were able to see a very slow improvement,” Dr. Menon said. He explained how, while this improvement was not statistically significant, it was “at least heading in the right direction.”

However, he warned it is very possible that some of these individuals “will never fully recover.”

The cognitive deficits observed may be due to several factors in combination, said the authors, including inadequate oxygen or blood supply to the brain, blockage of large or small blood vessels due to clotting, and microscopic bleeds. They highlighted how the most important mechanism, however, may be “damage caused by the body’s own inflammatory response and immune system.”

Adam Hampshire, PhD, of the department of brain sciences at Imperial College London, one of the study’s authors, described how around 40,000 people have been through intensive care with COVID-19 in England alone, with many more despite having been very sick not admitted to hospital. This means there is a “large number of people out there still experiencing problems with cognition many months later,” he said. “We urgently need to look at what can be done to help these people.”

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.

adding that the impairment is “equivalent to losing 10 IQ points.”

In their study, published in eClinicalMedicine, a team of scientists from the University of Cambridge and Imperial College London said there is growing evidence that COVID-19 can cause lasting cognitive and mental health problems. Patients report fatigue, “brain fog,” problems recalling words, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and even posttraumatic stress disorder months after infection.

The researchers analyzed data from 46 individuals who received critical care for COVID-19 at Addenbrooke’s Hospital between March and July 2020 (27 females, 19 males, mean age 51 years, 16 of whom had mechanical ventilation) and were recruited to the NIHR COVID-19 BioResource project.

At an average of 6 months after acute COVID-19 illness, the study participants underwent detailed computerized cognitive tests via the Cognitron platform, comprising eight tasks deployed on an iPad measuring mental function such as memory, attention, and reasoning. Also assessed were anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder via standard mood, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress scales – specifically the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), and the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 (PCL-5). Their data were compared against 460 controls – matched for age, sex, education, and first language – and the pattern of deficits across tasks was qualitatively compared with normal age-related decline and early-stage dementia.

Less accurate and slower response times

The authors highlighted how this was the first time a “rigorous assessment and comparison” had been carried out in relation to the after-effects of severe COVID-19.

“Cognitive impairment is common to a wide range of neurological disorders, including dementia, and even routine aging, but the patterns we saw – the cognitive ‘fingerprint’ of COVID-19 – was distinct from all of these,” said David Menon, MD, division of anesthesia at the University of Cambridge, England, and the study’s senior author.

The scientists found that COVID-19 survivors were less accurate and had slower response times than the control population, and added that survivors scored particularly poorly on verbal analogical reasoning and showed slower processing speeds.

Critically, the scale of the cognitive deficits correlated with acute illness severity, but not fatigue or mental health status at the time of cognitive assessment, said the authors.

Recovery ‘at best gradual’

The effects were strongest for those with more severe acute illness, and who required mechanical ventilation, said the authors, who found that acute illness severity was “better at predicting the cognitive deficits.”

The authors pointed out how these deficits were still detectable when patients were followed up 6 months later, and that, although patients’ scores and reaction times began to improve over time, any recovery was “at best gradual” and likely to be influenced by factors such as illness severity and its neurological or psychological impacts.

“We followed some patients up as late as 10 months after their acute infection, so were able to see a very slow improvement,” Dr. Menon said. He explained how, while this improvement was not statistically significant, it was “at least heading in the right direction.”

However, he warned it is very possible that some of these individuals “will never fully recover.”

The cognitive deficits observed may be due to several factors in combination, said the authors, including inadequate oxygen or blood supply to the brain, blockage of large or small blood vessels due to clotting, and microscopic bleeds. They highlighted how the most important mechanism, however, may be “damage caused by the body’s own inflammatory response and immune system.”

Adam Hampshire, PhD, of the department of brain sciences at Imperial College London, one of the study’s authors, described how around 40,000 people have been through intensive care with COVID-19 in England alone, with many more despite having been very sick not admitted to hospital. This means there is a “large number of people out there still experiencing problems with cognition many months later,” he said. “We urgently need to look at what can be done to help these people.”

A version of this article first appeared on Univadis.

FROM ECLINICAL MEDICINE

Few children with early social gender transition change their minds

Approximately 7% of youth who chose gender identity social transition in early childhood had retransitioned 5 years later, based on data from 317 individuals.

“Increasing numbers of children are socially transitioning to live in line with their gender identity, rather than the gender assumed by their sex at birth – a process that typically involves changing a child’s pronouns, first name, hairstyle, and clothing,” wrote Kristina R. Olson, PhD, of Princeton (N.J.) University, and colleagues.

The question of whether early childhood social transitions will result in high rates of retransition continues to be a subject for debate, and long-term data on retransition rates and identity outcomes in children who transition are limited, they said.

To examine retransition in early-transitioning children, the researchers identified 317 binary socially transitioned transgender children to participate in a longitudinal study known as the Trans Youth Project (TYP) between July 2013 and December 2017. The study was published in Pediatrics. The mean age at baseline was 8 years. At study entry, participants had to have made a complete binary social transition, including changing their pronouns from those used at birth. During the 5-year follow-up period, children and parents were asked about use of puberty blockers and/or gender-affirming hormones. At study entry, 37 children had begun some type of puberty blockers. A total of 124 children initially socially transitioned before 6 years of age, and 193 initially socially transitioned at 6 years or older.

The study did not evaluate whether the participants met the DSM-5 criteria for gender dysphoria in childhood, the researchers noted. “Based on data collected at their initial visit, we do know that these participants showed signs of gender identification and gender-typed preferences commonly associated with their gender, not their sex assigned at birth,” they wrote.

Participants were classified as binary transgender, nonbinary, or cisgender based on their pronouns at follow-up. Binary transgender pronouns were associated with the other binary assigned sex, nonbinary pronouns were they/them or a mix of they/them and binary pronouns, and cisgender pronouns were those associated with assigned sex.

Overall, 7.3% of the participants had retransitioned at least once by 5 years after their initial binary social transition. The majority (94%) were living as binary transgender youth, including 1.3% who retransitioned to cisgender or nonbinary and then back to binary transgender during the follow-up period. A total of 2.5% were living as cisgender youth and 3.5% were living as nonbinary youth. These rates were similar across the initial population, as well as the 291 participants who continue to be in contact with the researchers, the 200 who had gone at least 5 years since their initial social transition, and the 280 participants who began the study before starting puberty blockers.

The researchers found no differences in retransition rates related to participant sex at birth. Rates of retransition were slightly higher among participants who made their initial social transition before 6 years of age, but these rates were low, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of a volunteer community sample, with the potential for bias that may not generalize to the population at large, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the use of pronouns as the main criteria for retransition, and the classification of a change from binary transgender to nonbinary as a transition, they said. “Many nonbinary people consider themselves to be transgender,” they noted.

“If we had used a stricter criterion of retransition, more similar to the common use of terms like “detransition” or “desistence,” referring only to youth who are living as cisgender, then our retransition rate would have been lower (2.5%),” the researchers explained. Another limitation was the disproportionate number of trans girls, the researchers said. However, because no significant gender effect appeared in terms of retransition rates, “we do not predict any change in pattern of results if we had a different ratio of participants by sex at birth,” they said.

The researchers stated that they intend to follow the cohort through adolescence and into adulthood.

“As more youth are coming out and being supported in their transitions early in development, it is increasingly critical that clinicians understand the experiences of this cohort and not make assumptions about them as a function of older data from youth who lived under different circumstances,” the researchers emphasized. “Though we can never predict the exact gender trajectory of any child, these data suggest that many youth who identify as transgender early, and are supported through a social transition, will continue to identify as transgender 5 years after initial social transition.” They concluded that more research is needed to determine how best to support initial and later gender transitions in youth.

Study offers support for family discussions

“This study is important to help provide more data regarding the experiences of gender-diverse youth,” M. Brett Cooper, MD, of UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview. “The results of a study like this can be used by clinicians to help provide advice and guidance to parents and families as they support their children through their gender journey,” said Dr. Cooper, who was not involved in the study. The current study “also provides evidence to support that persistent, insistent, and consistent youth have an extremely low rate of retransition to a gender that aligns with their sex assigned at birth. This refutes suggestions by politicians and others that those who seek medical care have a high rate of regret or retransition,” Dr. Cooper emphasized.

“I was not surprised at all by their findings,” said Dr. Cooper. “These are very similar to what I have seen in my own panel of gender-diverse patients and what has been seen in other studies,” he noted.

The take-home message of the current study does not suggest any change in clinical practice, Dr. Cooper said. “Guidance already suggests supporting these youth on their gender journey and that for some youth, this may mean retransitioning to identify with their sex assigned at birth,” he explained.

The study was supported in part by grants to the researchers from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Arcus Foundation, and the MacArthur Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately 7% of youth who chose gender identity social transition in early childhood had retransitioned 5 years later, based on data from 317 individuals.

“Increasing numbers of children are socially transitioning to live in line with their gender identity, rather than the gender assumed by their sex at birth – a process that typically involves changing a child’s pronouns, first name, hairstyle, and clothing,” wrote Kristina R. Olson, PhD, of Princeton (N.J.) University, and colleagues.

The question of whether early childhood social transitions will result in high rates of retransition continues to be a subject for debate, and long-term data on retransition rates and identity outcomes in children who transition are limited, they said.